|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

e historic Grand Trunk Road cuts a swathe through north India, running from Bengal

in the east to the Punjab in the west. On the other side of the border, it continues through

Pakistan, reaching beyond Peshawar in the North-West Frontier Province. For over two

millennia, this busy thoroughfare that extends some 1500 miles has served as the main

artery of South Asia. So vital is the Grand Trunk Road to the subcontinent’s long history

that Raghubir Singh (1942-1999), one of India’s eminent documentary photographers,

traveled and photographed the Indian stretch of the route between 1988 and 1991. Ninety-

six photographs from his journeys appear in his book, e Grand Trunk Road: A Passage

rough India, which was published in 1995.

1

Singh is known for his style of pictorial street

photography,

which he has described as “the old Life magazine kind of photography.”

2

A

self-taught artist, he used the gaze of an observant traveler to develop lyrical photo essays

of everyday life in India’s cities and towns, and on its highways.

3

Singh’s photographs of the

Grand Trunk Road, or GT, show ordinary, albeit aesthetically charged, moments along the

path: busy pavement shops; pedestrians and commuters in various towns and cities; over-

turned trucks and stalled trac on the road; political rallies; and visitors to the Taj Mahal,

the Golden Temple, and other sites along the route. Singh’s colorful and picturesque style

lends itself well to presenting the hypnotic culture along South Asia’s main thoroughfare.

Along the Grand Trunk Road: The Photography of Raghubir Singh

Chaya Chandrasekhar

Abstract: For more than two millennia, the historic Grand Trunk Road, the busy

thoroughfare that extends some 1500 miles through north India and Pakistan,

served as the main artery of South Asia. It was also the gateway through which

waves of immigrants, travelers, and invaders entered the subcontinent. As a result,

a great deal of diversity and tolerance marks the road. Between 1988 and 1991,

Raghubir Singh (1942-1999), one of India’s renowned documentary photographers,

traveled and photographed the Indian stretch of the Road. Ninety-six photographs

from his journeys appear in the publication, e Grand Trunk Road: A Passage

rough India (1995). Singh used the pictorial style of street photography that he is

known for to capture everyday life along the path. Further, he emphasized the tre-

mendous diversity he witnessed along the road through the selections he made for

inclusion in the book and the specic manner in which he arranged many of them.

By underscoring the heterogeneity, Singh provided a critical visual commentary

on the political climate in India during the 1980s and early nineties. is period

coincided with the rise of Hindu nationalism, which aimed to erase the subconti-

nent’s diverse past and promote instead the idea of a homogenous/Hindu India. By

documenting the road in his uniquely pictorial style and arranging the photographs

in his book to draw attention to dierences and tolerance witnessed along the

path, Singh demonstrated that India was not monolithic, as the politics of the time

claimed, but a rich interwoven fabric of many varied strands.

Keywords South Asia; India; Raghubir Singh; Grand Trunk; photography; street

photography; pictoral style

Chaya Chandrasekhar is

Assistant Professor of art history

at Marietta College. Her area

of specialization is South Asian

art, with a focus on India. Her

current research interests include

contemporary Indian photog-

raphy and museum practices in

displaying Asia.

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

However, it is his precise selection and arrangement of photographs for e Grand Trunk

Road, in addition to the photographs themselves, which provide a critical visual commen-

tary, and speak to the broader political issues of his time.

Singh chose and organized the images in e Grand Trunk Road: A Passage rough

India to highlight the diversity that he witnessed along this crucial path. Pluralism and the

acceptance of dierences have long remained hallmarks of South Asian history and pervade

the Grand Trunk Road, which has for over two thousand years served as the primary thor-

oughfare for travelers entering and exiting the subcontinent. By underscoring this hetero-

geneity through his creative choices, Singh critiques the political climate in India during the

late 1980s and early 90s. At this time, Hindu-Muslim tensions intensied and violent com-

munal strife erupted. Many of these sectarian conicts found their origins in the politics of

partition, the dividing of British India along religious lines into what was seen as Muslim

Pakistan and Hindu India. Armed gates at the India-Pakistan border, raised aer partition,

continue to underscore the political impasse. Singh chose to photograph the Grand Trunk

Road, which, despite the strained politics, continues to connect the two nations. By docu-

menting the road in his uniquely pictorial style and arranging the photographs in his book

to draw attention to the diversity, general tolerance, and accommodation witnessed along it,

Singh lays bare a cultural actuality markedly dierent from the divisive political climate in

India at the time.

e slogan “unity in diversity” that is frequently used to describe pluralism in twentieth-

century India also points to the long tradition of tolerance that has generally characterized

the subcontinent. is is not to suggest an over-simplied, utopic history of India, without

periods of violent conict and severe persecution. Rather, the slogan highlights the ability

of the subcontinent’s population to coexist, more or less amicably, even with tremendous

cultural, political, and economic disparities. Indeed, several scholars have convincingly

argued that despite fundamental dissimilarities among communities, as well as deep-rooted

dislikes and resentments that people might harbor for each other, a surprising degree of

diversity and acceptance has persisted throughout much of the subcontinent’s long and

turbulent history. For example, Amartya Sen in his Argumentative Indian establishes that

the subcontinent boasts a longstanding tradition of broad thinking, reasoned dialogue,

and the accommodation of dissenting views.

4

Ashis Nandy describes India as exemplary of

“radical diversities,” or the ability of people to live with cultural dierences that oppose their

own fundamental beliefs. Nandy notes that diversity in India does not mean that dierent

communities entirely shed the distrust they might have, or the dislike they might feel, for

each other. Nevertheless, fully aware of the prejudices on both sides, they accept each other

as part of the Indian whole.

5

Shashi aroor is another proponent of the view that Indian

identity is constructed in diversity:

Indian mind has been shaped by remarkably diverse forces: ancient Hindu tradi-

tion, myth, and scripture; the impact of Islam and Christianity; and two centuries

of British colonial rule. e result is unique, not just because of the variety of con-

temporary inuences available in India, but because of the diversity of its heritage...

Pluralism is a reality that emerges from the very nature of the country; it is a choice

made inevitable by India’s geography and rearmed by its history.

6

India’s diversity is especially pervasive and visible along the Grand Trunk Road, as the

highway marks an ancient path that linked the kingdoms and people of the subcontinent to

each other, as well as to the outside world. As far back as the fourth century BCE, when the

Mauryas established the rst Indian empire (c. 323-185 BCE), the Royal Road, the ances-

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

tor of the Grand Trunk Road, connected the capital city, Pataliputra, with points west and

east. Megasthenes (c. 350-290 BCE), the Seleucid ambassador to the court of the emperor

Chandragupta Maurya (r. c. 323-297 BCE), wrote an early account of India that provided a

description of the road.

7

He underscored the multi-cultural makeup of the trail and its rela-

tive accommodation for dierences when he noted that international trade ourished along

the route, and that foreign merchants were aorded special care and attention.

8

Following

waves of Islamic invaders,

9

who gradually established their new religion in the subconti-

nent, Zahir ud-din Babur (1483-1530) arrived along the route in 1526 and laid the founda-

tions of the mighty Mughal Empire, the most prominent and inuential of Islamic dynasties

in South Asia.

10

e road today is ocially named Sher Shah Suri Marg, aer the sixteenth-

century Pashtun Afghan who briey displaced the Mughals to take control of Delhi. Sher

Shah Suri (1540-1555) refurbished the old road

11

and further established safe and comfort-

able serais, which accommodated the needs of diverse travelers.

12

e thoroughfare also formed a capillary of the great Silk Road, the network of routes

that facilitated commercial and cultural exchanges across Eurasia.

13

Scholars have long rec-

ognized the religious diversity and cultural exchange that ourished along the Silk Road.

14

is network saw the transmission of a number of religious traditions, including Zoroastri-

anism, Manichaeism, Christianity, and Islam. Buddhism, originating in India, was the most

inuential export from the subcontinent to also use this route. Not surprisingly then, the

pluralism witnessed along the Silk Road permeated its Indian branch.

Under East India Company rule in 1839, the British paved the ancient path and called

it the Grand Trunk Road.

15

Allowing the movement of troops from one garrison town to

another as it connected the vast stretch of the empire from Calcutta to Kabul, the road was

the lifeline of British India. Together with the railway, it permitted the transportation of

goods and lucrative trade, which fed the imperial economy.

16

Rudyard Kipling in his 1901

novel, Kim, describes the route as:

… the Big Road…the Great Road which is the backbone of all of Hind… All castes

and kinds of men move here… It runs straight…for een hundred miles—such a

river of life as nowhere exists in the world.

17

Like so many observers before him, Kipling marveled at the constant ow of human-

ity on the road and recognized the heterogeneous makeup of the multitudes. For more

than two thousand years visitors, immigrants, and invaders, whether their motivations

were peaceful or aggressive, made their way into India through the northern arterial path.

Raghubir Singh’s photographs capture the continuing propensity of these diverse popula-

tions to coexist, accommodating, though sometimes grudgingly, each others’ fundamental

dierences.

In the introductory essay to e Grand Trunk Road, Singh recalls how he covered the

path in a manner similar to nineteenth-century European surveyors:

I travelled slowly…doing a distance of sixty to eighty miles a day, which approxi-

mated the distances travelled…by the nineteenth-century photographers like

Samuel Bourne, Colin Murray, and Felice Beato.

18

e colonial photographers, directed by the “picturesque” tradition of British landscape

painting, focused on panoramic views of monuments along the path, which proclaimed

the subcontinent’s majestic past.

19

For instance, colonial representations of the Taj Mahal,

though grand and monumental, noticeably lack people at the site. If people do appear in

the frame, they are inconspicuous against a backdrop of the imposing structure. As Ariela

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

Freedman observes, the colonial photographers saw, without a problem, “a densely popu-

lated, vibrant country as a series of beautiful but elegiac monuments to the past. It takes a

great deal of eort to photograph an empty Taj Mahal.”

20

Such an eort was worthwhile for

the colonial photographers because the buildings, rather than the people who populated

them, made up their vision of the subcontinent.

By contrast, Singh privileges the individual and the ordinary over the historically monu-

mental. In the introduction to e Grand Trunk Road, he asserts:

I have looked at the Grand Trunk Road with a democratic eye, the eye that cuts

monument and majesty down to size, and places equal importance on the truck

driver…the groundsman at the Taj with his broom, the Sikh farmer, the housewife

in her shack…and so many others who make the Grand Trunk Road a living pan-

orama of north India’s people.

21

Freedman compares one of Singh’s photographs of the Taj Mahal with those made by

nineteenth-century European surveyors.

22

Singh’s image reveals a close up of ve visitors

at the site. Four of the ve people make eye contact with the camera as they walk toward

the proper le of the composition. A young woman, closest to the viewer and facing in the

opposite direction, draws the eye back into the picture. Rather than a panoramic view of

the monument, the Taj’s distinctive white marble architecture tightly frames the gures.

e photograph is more a portrait of the individuals than a landscape featuring the historic

building. Freedman concludes, “By displacing this iconic monument to desire, which has

also stood for the western desire for India, Singh emphasizes the Indian subject rather than

India as object.”

23

Singh’s emphasis of the individual over the monumental allowed him to

capture everyday life along the Grand Trunk Road. By making this choice, Singh is able to

demonstrate in his e Grand Trunk Road book that the masses coexist despite their vast

cultural, political, and ideological dierences.

Another photograph from e Grand Trunk Road similarly diers from typical colonial

representations of important sites and monuments in India (Figure 1). In this image, Singh

brings into focus the hustle and bustle of the street outside the Jama Masjid, Delhi. In the

center of the composition is a Muslim woman dressed in a black burqa, which covers her

Figure 1: Raghubir Singh, Jama

Masjid and Bazaar Crowd, Delhi

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

face and body. A cycle rickshaw driver on his bike appears in the proper right foreground,

while the close up of a young man’s face, looking directly into the lens, occupies the le.

Pedestrians, including a man in the white ṭāqīyah prayer cap that Muslims wear, bus-

ily move about in the middle ground. Sections of the distinctive red sandstone and white

marble walls, arches, domes, and minarets of the mosque appear in the background. As in

the photograph of the visitors at the Taj Mahal, in this example Singh brings into focus the

people on the Grand Trunk Road, rather than the ancient monuments emptied of buoyant

life.

Singh’s approach of focusing on the ordinary and the individual rather than the monu-

mental on the Grand Trunk Road may have been inspired by the Bengali writer, artist, and

lmmaker Satyajit Ray (1921-1992). Singh was born into a wealthy Rajput household in

Jaipur, Rajasthan. In 1961, he moved to Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) where he began his

photographic career and came into contact with Ray. Singh recounts Ray’s inuence on

him: “In Calcutta, through my contact with Satyajit Ray and his work—deeply rooted in the

pictorial, rising out of the communal spirit of India… I received an upliing education.”

24

Singh’s method of focusing on the individual echoes Ray’s own preoccupation with com-

memorating the local and the microcosm throughout his lmic work.

e majority of Ray’s lms are in the local Bengali language and set in Bengal. When

asked in an interview why Ray made lms, he replied, “Apart from the actual creative work,

lmmaking is exciting because it brings me closer to my country and my people.”

25

Simi-

larly, Singh’s photographic oeuvre is a keenly observed visual and emotional response to

India.

26

Singh asserts, “e breath I take is deeply Indian because all my working life I have

photographed my country. In doing so, I have been carried by the ow of the inner river of

India’s life and culture.”

27

Ray and Singh were profoundly connected to India, and their broad and absorptive

outlooks were undoubtedly shaped by South Asia’s long ethos of diversity and general

acceptance. In an insightful essay, Amartya Sen demonstrates how Ray’s writing and lms

highlighted the dierences between various local cultures and the importance of intercul-

tural connections and communications:

In emphasizing the need to honor the individuality of each culture, Ray saw no

reason for closing the doors to the outside world. Indeed, opening doors was an

important priority of Ray’s work… Ray appreciated the importance of heterogeneity

within local communities.

28

Singh similarly acknowledged that in photographing India he witnessed the rich diver-

sity of people, artistic traditions, ways of life, and inuences from both the west and the

east, which have enriched and deepened the Indian spirit:

In India, I am on court, the tennis player’s court, where the ball has to be hit to the

edge of the camera frame, so that it raises dust, but yet it is inside. Within the ten-

sion of those frame lines, there is the buoyant spirit of Kotah painting; and there is

the Zen of sight and sense… I have looked at the densely Indian characters of R.K.

Narayan, I have looked at the acute analysis of today’s India in the prose of V.S.

Naipaul…I have looked at the pictorialism and bazaar energy of Salman Rushdie’s

ction…I have looked at the ames-side pictorialism pitched by Anish Kapoor,

the Indian-born sculptor…I put within my frame the ancient sites, the crossings, the

conuences of rivers…the big and small roads, the big and small cities…

29

For people like Ray and Singh, who deeply advocated and celebrated diversity, the politi-

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

cal shi that occurred in India during the 1980s and early 90s, which threatened to undo

the long history of general tolerance and acceptance in the subcontinent, would have been

deeply troubling. is period witnessed the resurgence of the Hindutva, or Hindu national-

ism, and the rapid rise of its political arm, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Hindutva ideol-

ogy aims to present India as a purely Hindu nation. Its agenda espouses religious binaries

to claim Hinduism’s superiority over other traditions. is narrow view alienates religious

minorities and threatens India’s history of by and large accommodating sectarian dier-

ences, impeding twentieth-century aims to forge and maintain a pluralistic democracy.

e BJP led the nation as part of a coalition government in 1998, but lost support in 2004

in large measure due to its overly zealous religious conservatism.

30

Singh said little publi-

cally about his political views and opinions on the Hindutva. However, the photographs he

selects for inclusion in e Grand Trunk Road, and their deliberate arrangement to create

specic visual narratives within the book, betray his desire to underplay the partisan poli-

tics of his time and present instead an India that is not the purview of Hindus or Hinduism

alone, but a domain that belongs equally to Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, and numerous other

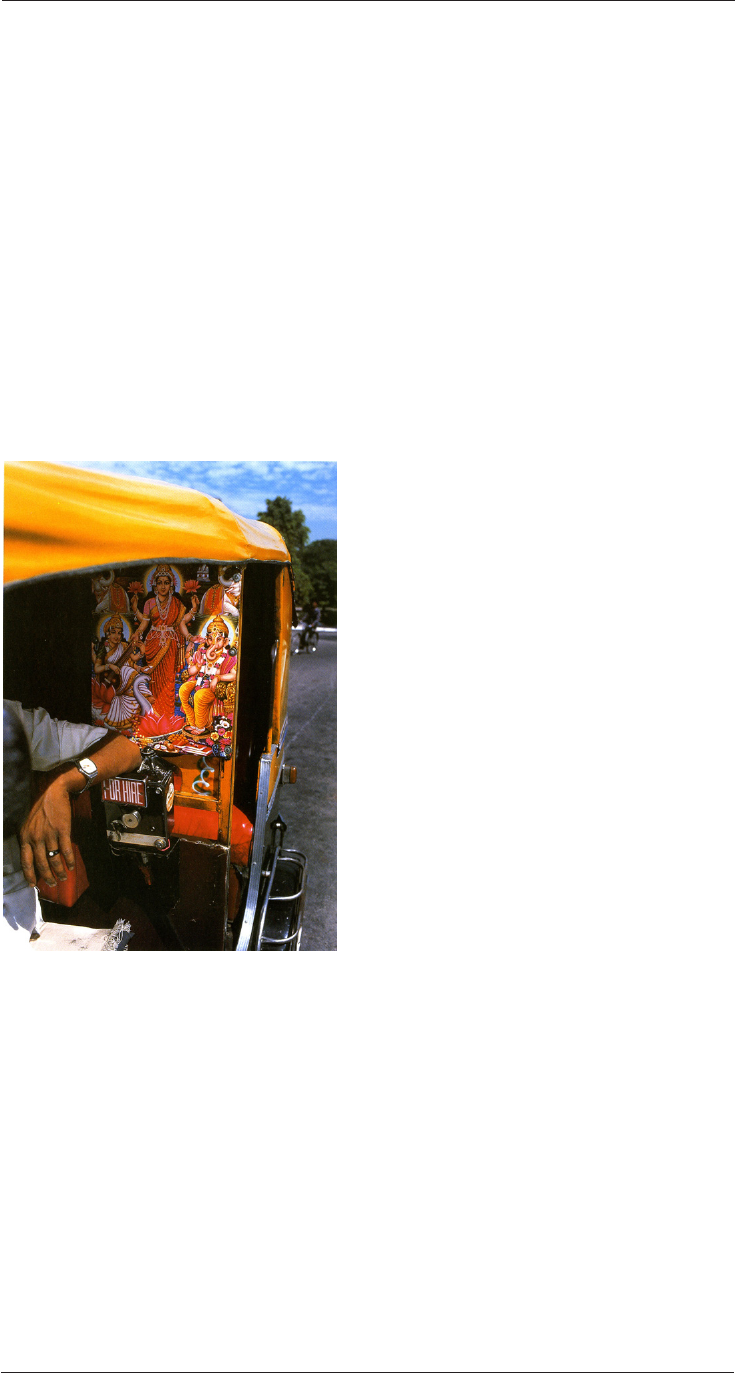

religious and secular factions. For example, in e Grand Trunk Road, on the page across

from the image of the Jama Masjid (Figure 1),

is a tightly framed photograph of an interior of

an autorickshaw in New Delhi (Figure 2). e

viewer gets a glimpse of only the auto driver’s

arm resting on the vehicle’s meter-reader. e

focus of the picture is a colorful print of Hindu

gods and goddesses, which conveys the driver’s

religious aliation. e two photographs—the

grand Muslim mosque with its patrons and the

Hindu autorickshaw driver’s divine protectors—

displayed side by side, highlight the heteroge-

neous reality along the route. rough creative,

visual means, Singh exposes the fallacy of a

monolithic Hindu India.

Elsewhere in the publication, Singh conveys

a similar message with a pair of photographs

from the ancient city of Varanasi (formerly

Benares), along the Grand Trunk Road as it cuts

across the state of Uttar Pradesh (Figures 3 and 4).

Instead of introducing the city through the temple edices and iconic stepped ghats

on the banks of the Ganges River, where throngs of Hindu pilgrims gather to bathe in the

sacred waters, as so many photographers, and Singh himself in his other publications, have

done previously, Singh includes the city’s crowded streets and images of the commonly seen,

but less published, India. One photograph from the pair reveals an aged Hindu ascetic pas-

senger on a bicycle rickshaw stalled in trac (Figure 3). Singh juxtaposes this photograph

with another, arranged symmetrically on the opposite page, which features a Muslim family

riding a bicycle rickshaw on a similarly bustling street (Figure 4). A woman covered in a

black burqa conrms the family’s religious identity. A man sits beside her on the seat and a

child squats uncomfortably in between her legs on the rickshaw’s footrest. e two photo-

graphs portray iconic elements within the Hindu and Islamic traditions—the wandering

ascetic and a woman entirely covered by a black burqa, respectively. However, Singh does

not depict these individuals as devout and dutiful followers of disparate religions. Instead,

Figure 2: Raghubir Singh, A

Scooter-Taxi, New Delhi

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

they both are shown in nearly identical situations, navigating trac on rickshaws in the all-

too-familiar, overcrowded streets. When placed side by side, the photographs of the Hindu

ascetic and of the Muslim family make a statement that Varanasi, despite its overwhelm-

ing association as a sacred Hindu city, is equally home to India’s Muslim communities.

Importantly, some of Singh’s most well-known images feature Varanasi’s impressive ghats.

31

Freedman observes that the steps, where religion and everyday life merged seamlessly, were

among Singh’s favorite places to photograph.

32

However, Singh deliberately downplays the

ghats in his e Grand Trunk Road book, since featuring the steps and imposing temples

would have privileged the Hindu aliation of Varanasi over the other religious traditions

that coexist there. e busy streets of the city, on the other hand, show territory where both

Hindus and Muslims stake equal claim.

Holi Festival Day, another photograph in e Grand Trunk Road series, further under-

Figure 3: Raghubir Singh, Rick-

shaw Trafc, Benares

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

Figure 4: Raghubir Singh, Scoot-

erist and Rickshaw Passengers,

Benares

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

scores India’s largely tolerant past, which continues into the present day (Figure 5). In the

background, the imposing ramparts that enclosed the Mughal emperor Akbar’s (1542-1605)

imperial city at Agra stand as testament to India’s rich Islamic heritage. In the foreground,

three vendors idly await customers who are seen exiting the monument’s arched gateway.

One of the vendors wears a shirt and pair of pants stained bright magenta, while another,

seated on a low wall and peering into the camera, has his face smeared black. A visitor exit-

ing the gateway similarly wears a white shirt stained pink. ese men’s appearance indicates

that they have partaken in Holi, the Hindu festival of color. Holi marks the yearly onset of

spring, with revelers tossing color at each other to celebrate. e inclusion of this photo-

graph, which shows Hindus celebrating amidst a landscape of Mughal monuments, shows

Singh’s creative challenge to the polarizing and combative Hindutva political climate that

was rapidly rising in India at the time.

Hindu nationalists demonized Mughal emperors as iconoclastic Muslim outsiders who

had indiscriminately desecrated and destroyed Hindu lands. e Hindutva’s anti-Muslim

campaign centered on reclaiming north Indian temple sites previously conquered by Islamic

rulers. e watershed moment was the destruction of the Babri Masjid, a sixteenth-century

mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, built by Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, aer

the supposed destruction of a temple that marked the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama

(Ramjanmabhumi).

33

In 1984, the BJP entered mainstream Indian politics and endorsed

the Ayodhya Ramjanmabhumi campaign, which called for reclaiming the Babri Masjid site

for a temple dedicated to Rama. Special bricks commissioned by supporters from across

the country and from abroad were to be used in the temple’s construction. In 1990, the

BJP launched the Rath Yatra (temple chariot procession), during which the BJP leader

L.K. Advani galvanized crowds over loudspeaker as the parade moved from town to town

across north India. Muslim communities along the way were threatened, and pockets of

violence erupted. When the procession ultimately reached Ayodhya in 1992, angry mobs

swarmed and demolished the mosque, prompting deadly and widespread religious riots

across India.

34

Singh’s Holi Festival Day conveys the disconnect between the Hindutva’s anti-

Muslim agenda and ongoing life in India. Politically motivated religious radicalism, Singh

shows, ultimately does little to undermine the extensive history of assimilation and solidar-

Figure 5: Raghubir Singh, Holi

Festival Day, Red Fort, Agra

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

ity in India.

e origins of much of the communal politics that escalated in the eighties and early

nineties, when Singh photographed the GT, may be traced to the 1947 partition of British

India into Pakistan and Hindustan (India). e line on the map cut through the Punjab,

splitting the Sikh homeland;

35

the resulting discontent experienced due to partition exacer-

bated Hindu nationalist sentiments.

36

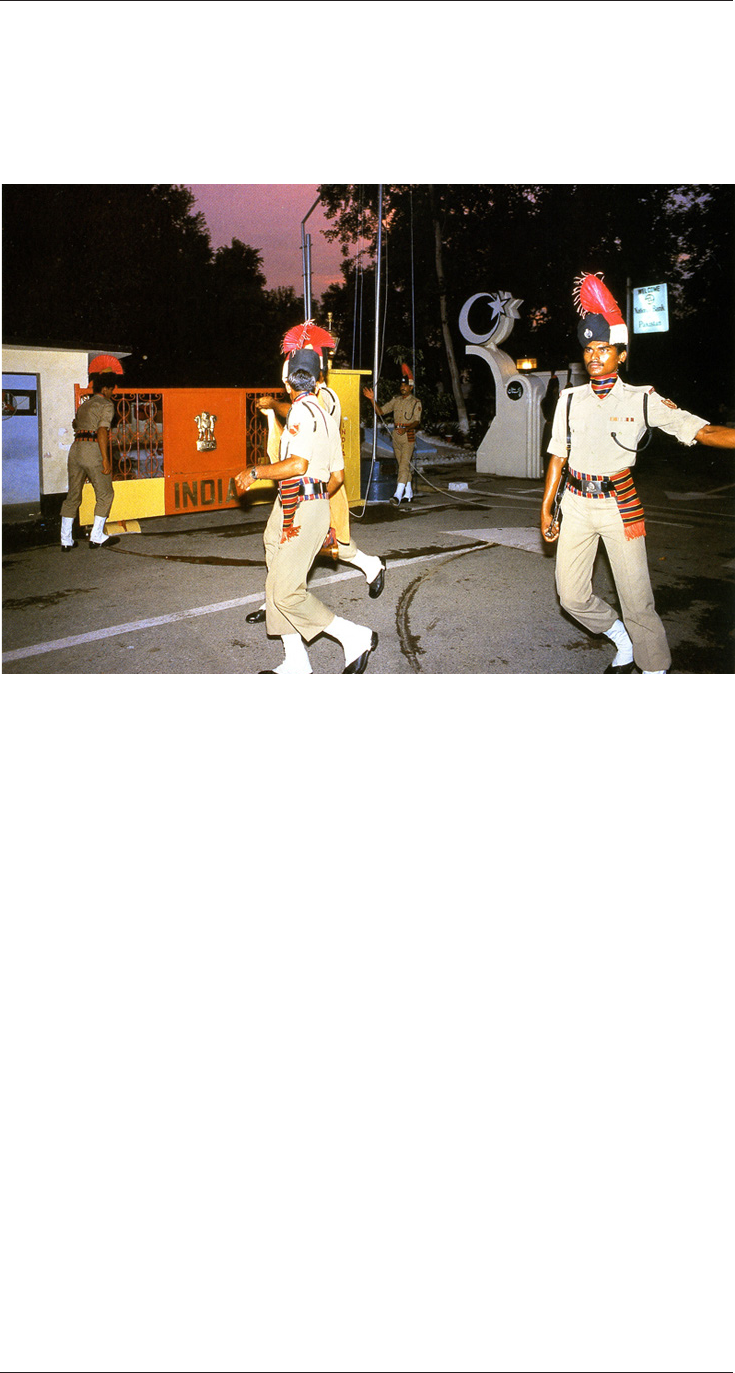

Drawing attention to this history, Singh’s e Grand

Trunk Road comes to an arresting halt with a photograph of the border post at Atari in the

Punjab, where a white line on the ground and boundary gates divide India from Pakistan

(Figure 6). Indian Border Security Forces maintain vigilant watch on the Atari side. On the

other side of the line lies Wagha, with Pakistani Rangers on patrol. National ags announce

the border limits of each country.

37

To date, every evening at sundown, Indian and Pakistani

security forces at Atari-Wagha ceremoniously beat retreat to call truce for the night. Crowds

of spectators occupy bleachers on either side of the gates to witness their respective national

soldiers perform the ritual. Stephen Alter in his travelogue, Amritsar to Lahore, describes

the pageantry:

e ceremony began with one of the soldiers presenting arms and marching with

vigorous strides to the gate and back. Orders were shouted in belligerent voices,

the words virtually unintelligible. A second soldier repeated the same maneuver…

Across the border we could hear similar commands being shouted and the clatter

of hobnailed boots. is posturing continued for at least ten minutes until the gate

at the border was nally thrown open. e two separate audiences rose to their feet

and peered across at each other like the supporters of opposing football teams…

Two commanders came out of the gate and shook hands… Two buglers played…

and the ags were lowered in unison.

38

One might reasonably expect a photographer at the border to capture some of the

bristling patriotism that Alter vividly describes, such as the border security forces in full

uniform marching to and fro. At the least, since many of Singh’s e Grand Trunk Road

photographs focus on ordinary people, one might anticipate images of enthusiastic crowds

Figure 6: Raghubir Singh, Indian

Border Security Force Soldiers at

the India-Pakistan (Atari-Wagah)

Border, Punjab

© 2013 Succession Raghubir

Singh

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

as they watch the retreat from the stands. However, Singh chooses to record this location

by altogether sidestepping the nationalistic exhibitionism and the ordinary citizenry serv-

ing as spectators. Instead, he selected a photograph that shows the ceremony’s humdrum

aermath.

As if to underscore the futility of borders and divisive demarcations, the image shows

members of the Indian Border Security Forces nonchalantly moving about as they close the

day. One man folds the Indian ag that would have been lowered during the ceremony. A

bugler, who would have only moments ago fervently sounded the instrument as the soldiers

strutted back and forth during the retreat, walks casually beside the man with the ag. He

faces away from the camera, possibly to converse with his companion. e ag and the

bugle in the men’s hands are barely visible. ree other soldiers nishing up their daily rou-

tines appear by the gates and the ag post. Aside from the crescent-moon-and-star insignia

on a wall, a barely visible Pakistani Ranger with his back to the viewer, and a lighted sign

that announces the National Bank of Pakistan in the background, little else in the photo-

graph suggests that the area across the white line is a separate country. Singh, it seems, saw

little point in the separation and the guarded protectionism on either side of the border.

Instead, the image recalls his photographs wherein Hindu, Muslim, and others equally

occupy the camera frame.

Singh was denied permission to cross the border into Pakistan and continue his photo-

graphic journey along the Grand Trunk Road. He concludes the publication with a “Note

From the Photographer,” in which he writes:

…e powers that be in Pakistan refused me permission to photograph there, in

spite of my oer to allow myself to be conducted, to photograph only the culture

and common people along the route, to focus on historic sights, and to show text

and pictures to Pakistani representatives.

39

e note makes clear that there was no will for rational negotiation on the part of the

Pakistani government. Singh’s words indicate his frustration with the authorities. Similarly,

by focusing on the post-retreat banalities rather than any aspect (monumental or ordinary)

of the pomp and pride of ceremony, Singh’s photograph of Atari-Wagha echoes his disap-

proval of the unyielding implementation of restrictive religio-political border bureaucracies.

e photograph invites reection on a provocative question raised by Alter: What meaning

could Atari-Wagha’s choreographed displays have when combat soldiers dangerously face

o over the border dispute, and wage actual war at Kargil and other sites across the Line of

Control in the Kashmir region to the north?

40

e Kashmir border dispute, the crystallization of divisive politics in South Asia, dates

back to the time of partition.

41

In 1949, only two years aer gaining independence, the

edgling nations of India and Pakistan waged war over the territory, which resulted in the

Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir region and the smaller Azad Kashmir area under

Pakistani control. Two additional India-Pakistan wars in 1965 and 1971 saw the redrawing

and altering of the Line of Control. e Kashmir border dispute reignited in the 1980s, at

the same time that Singh undertook his journey along the Grand Trunk Road. is conict

marked a shi from the earlier uprisings. Disenfranchised Indian Kashmiri Muslims, in

part threatened by the conservative, pro-Hindu swing in politics, led an insurgency against

the Indian government, demanding a separate state. is allowed the BJP and other Hindu-

tva factions to fan the ames of growing Hindu-Muslim tensions.

42

Against a backdrop of divisive politics that rst led to the severing of the subconti-

nent, followed by decades of bloodshed and hostility in post-independence times, Singh’s

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

photographs show a world beyond borders and divides. Singh’s carefully constructed visual

narrative in e Grand Trunk Road underscores the irony of metal gates and a white line on

the ground blocking a path which, for millennia, had allowed a constant ow of trac and

helped build and shape the capacious and absorptive cultural ethos of the subcontinent. For

over two thousand years the thoroughfare connected India to the outside world. It allowed

the transit of diering ideas and rich exchanges, which fostered in South Asia a culture of

acceptance and tolerance. Singh brings India’s open and accommodating history into focus

in order to contrast the intolerant and small-minded politics of the day, which aimed to

homogenize and erase the subcontinent’s long history of diversity. His photographs, and the

manner in which he arranges them in e Grand Trunk Road book, reiterate that India is

not the domain of a single group, but a complex, rich interwoven fabric of diering strands.

Such pluralism in India extends beyond religion alone. In Singh’s photographs one sees not

only religious contrasts, but also contrasts of a variety of other aspects of Indian life. Cycle

rickshaws juxtapose with motorized vehicles, men and women in traditional dress stand

and walk next to those in western clothes, life in the cities is contrasted with life in rural

India.

One might question whether or not Singh’s outlook of the Grand Trunk Road reects

nostalgia for a fading past, when no gates prevented entry and few inexible bureaucracies

hindered movement along arterial paths. On the contrary, Singh’s photographs convincingly

show that diversity is not a thing of the past in India. A heterogeneous matrix visibly per-

sists along the Grand Trunk Road. Singh’s concluding words in the publication’s introduc-

tion reect this view. “At the end of my own journey through life, I would like my ashes to

be scattered where the Grand Trunk Road crosses the Ganges. ere all castes and all kinds

of men and women walk.”

43

1. Raghubir Singh, e Grand Trunk Road: A Passage rough India (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1995).

2. Singh quoted in “Conversation: V.S. Naipaul and Raghubir Singh” in Raghubir Singh, Bombay: Gateway

of India (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1994) p. 5. Singh was a prolic photographer, who published

several photo essays during the span of his photographic career. ese include Calcutta: e Home and

Street (New York: ames & Hudson, 1988), e Ganges (London: ames & Hudson, 1992), Tamil Nadu

(New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 1996) and his last book, published posthumously, A Way into India

(London: Phaidon, 2002).

3. Sabeena Gadihoke describes Singh’s work as that of a âneur photographer, a casual wanderer and con-

noisseur of the street, who adeptly seeks out and captures aesthetically-lled moments of ordinary life. See

Sabeena Gadihoke, “Journeys into Inner and Outer Worlds: Photography’s Encounter with Public Space in

India” in Where ree Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (Got-

tingen, Germany: Steidl, 2010) p. 36.

4. Amartya Sen, e Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity (London and

New York: Penguin Books, 2005). roughout the book Sen acknowledges the turmoil and tumult of India’s

past, but convincingly demonstrates that India also has had a long tradition of accepting dierent groups

and allowing them the right to follow their own beliefs, which were frequently dramatically dierent from,

and even opposed to, those of others around them. Singh uses the Sanskrit word swīkriti, acceptance, to

describe this pluralist toleration. For more on this, see Sen, e Argumentative Indian pp. 34-44.

5. In a talk on Asian cosmopolitanism, Nandy explains, “All communities [in India] are internalized…your

self-denition included the other communities…one learns to host the otherness of the other… not the

sameness of the other.” Quoted from Ashis Nandy, “Ashis Nandy on Cosmopolitanism.” Filmed September

8, 2011, posted by Asia Society, http://asiasociety.org/countries/traditions/ashis-nandy-asian-cosmopolitan-

ism. Also see Ashis Nandy, “e Political Culture of the Indian State” Daedalus 118 (1989): 1-26.

6. Shashi aroor, India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond (New York: Arcade Publish-

ing, 1997) p. 10. In an article aroor wrote for e Guardian in 2007 to mark sixty years of Indian

independence, he draws on the idea of the American melting pot and compares India to a thali,

a meal made up of dierent dishes served in individual bowls placed within a single platter. Each

does not necessarily mix, but contributes to making a satisfying plate. See Shashi aroor, “In-

dian identity forged in diversity. Every one of us is in a minority,” e Guardian, August 14, 2007,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/aug/15/comment.india.

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

7. Strabo, Geography. (Tr. H.L. Jones), Vol. VII. London, 1930, p. 17, cited in Abdul Khair Muhammad Fa-

rooque, Roads and Communications in Mughal India (Delhi: Idarah-I Adabiyat-I Delli, 1977) p. 4.

8. K.M. Sarkar, e Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: 1849-1886 (1927, New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers, 1986)

p. 2.

9. From as early as the eighth century, when a part of the subcontinent rst converted to Islam, non-Muslims

were categorized as dhimmi, or protected people. ey were allowed to practice their religion and have

autonomy over their jurisprudence, but they had to pay the jizya, or poll tax, levied on non-Muslims. For a

general discussion of religion in Islamic India, including the dhimmi and jizya, see Annemarie Schimmel,

e Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture (London: Reakton Books, 2004) pp. 107-141.

During his reign, the Mughal emperor Akbar (1542-1605), whose openness to religious dierences and

celebration of diversity is legendary, revoked the jizya and allowed Hindus the opportunity to hold high

administrative posts. Amartya Sen addresses Akbar’s broad, pluralistic views at various points throughout

his book, e Argumentative Indian. For a more extended discussion see pp. 17-19. Aurangzeb Alamgir

(1608-1707), a later Mughal emperor, set out to transform India into a purely Islamic nation. He staunchly

enforced šarīʿah law and the jizya was reintroduced in 1679. See Schimmel, based on the Fatwa-yi Alamgiri,

a set of laws instituted during the time of the Aurangzeb, p. 110. Aurangzeb’s heavy-handed policies and

attempts at homogenizing the country were unsuccessful perhaps at least in part because it was antithetical

to the general acceptance of dierences and tolerance that prevailed in India.

10. Annemarie Schimmel notes that in January 1505, Babur entered the subcontinent through Kohat and

Bannu, in what is today northwest Pakistan. See Schimmel, p. 23. e Imperial Gazetteer of India indicates

that the Grand Trunk Road and nearby Kohat and Bannu formed a network of roadways in the North

West Frontier Province. See e Imperial Gazetteer of India: Vol. XIX Nayakanhatti to Parbhani (Oxford:

Claredon Press, 1908) p. 186.

11. Based on the Tarikh-i-Khan Jahani, cited in Farooque, p. 11, notes 28 and 29.

12. Basheer Ahmad Khan Matta writes that serais during Suri’s time provided separate lodgings for Hindus and

Muslims and housed mosques with an imam and a muezzin. Basheer Ahmad Khan Matta Sher Shah Suri: A

Fresh Perspective (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005) pp. 210-213.

13. For a discussion of the section of the Grand Trunk Road in present day Pakistan that formed a part of the

Silk Road, see Saifur Rahman Dar, “Caravanserais Along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan: A Central

Asian Legacy” in Vadime Elissee, e Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce (Oxford and New

York: Berghahn Books, 2000) pp. 12-46.

14. Valerie Hansen, e Silk Road: A New History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) p. 5.

15. Sarkar, p. 3.

16. For more on roadways and railways during British rule in India, see Sarkar, e Grand Trunk Road in the

Punjab: 1849-1886.

17. Rudyard Kipling, Kim (1901, New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1999) p. 59.

18. Singh, e Grand Trunk Road, p. 4.

19. For more on this, see Clark Worswick and Ainslee Embree, e Last Empire: Photography in British India,

1855-1914 (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2001) p. 2.

20. Ariela Freedman, “On the Ganges Side of Modernism: Raghubir Singh, Amitav Ghosh, and the Postcolonial

Modern” in Laura Doyle and Laura Winkiel eds., Geomodernisms: Race, Modernism, Modernity (Blooming-

ton, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2005) p. 119.

21. Singh, e Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.

22. Singh, e Grand Trunk Road, p. 72.

23. Freedman, p. 119.

24. Raghubir Singh, “River of Colour: An Indian View” introduction to e River of Colour: e India of Raghu-

bir Singh (London: Phaidon, 1998) p. 13.

25. Quoted in Bert Cardullo ed., Satyajit Ray: Interviews (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi,

2007) p. viii.

26. For more on Singh’s work and relationship to India, see Singh, Bombay, p. 5.

27. Singh, River of Colour, p. 10.

28. Amartya Sen, “Satyajit Ray and the Art of Universalism: Our Culture, eir Culture” e New Republic

(April 1, 1996): 32. Reprinted with permission of the author and accessible at http://satyajitray.ucsc.edu/

articles/sen.html

29. See Singh, River of Colour, p. 13.

30. For a concise discussion of the rise and fall of the BJP and its political allies and ideologies, see Amartya

Sen, e Argumentative Indian, pp. 45-72.

31. See, for example, Swimmers and diver, Scindia Ghat, Benares, 1985 in Raghubir Singh, e Ganges (London:

ames and Hudson, 1992) plate 53.

32. Freedman, p. 121.

33. A large body of scholarship exists on the Ayodhya incident and the politics that surround it. For an excel-

lent introduction, see Richard Davis, “e Rise and Fall of a Sacred Place: Ayodhya Over ree Decades”

in Marc Howard Ross ed., Culture and Belonging in Divided Societies: Contestation and Symbolic Landscape

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) pp. 25-44. Also see Ashis Nandy, Creating a National-

ity: e Ramjanmabhumi and Fear of Self (Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

|

A G T R: T P R S

ASIANetwork Exchange

|

Spring 2013

|

volume 20

|

2

34. Hindu-Muslim hostilities, warfare, and persecutions also occurred in pre-colonial times. Nevertheless, the

blatant religio-political agenda of the Hindutva, and its political factions like the BJP, to many seemed to

be in direct conict with twentieth-century India’s aim towards maintaining a pluralistic, secular democ-

racy—however imperfectly realized. See Gabriel Palmer-Fernandez ed., e Encyclopedia of Religion and

War (New York, London: 2004) p. 174. For an excellent study of Hindu-Muslim conicts and civic life in

India, see Ashutosh Varshney, Ethnic Conict and Civic Life: Hindus and Muslims in India (Yale University

Press, 2002).

35. For a review, see Yasmin Khan, e Great Partition: e Making of India and Pakistan (New Haven and

London: Yale University Press, 2007). For a recent account of partition and the Punjab, see Neeti Nair,

Changing Homelands: Hindu Politics and the Partition of India (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard

University Press, 2011).

36. Davis, p. 39.

37. For a description of the Atari-Wagha post and discussion of the travails of crossing the India-Pakistan

border, see Stephen Alter, Amritsar to Lahore: A Journey Across the India-Pakistan Border (Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001) pp. 52-73, 154-170.

38. Alter, p. 53.

39. Singh, e Grand Trunk Road, p. 127.

40. Alter, p. 53.

41. I have drawn the brief outline from Victoria Schoeld, Kashmir in Conict: India, Pakistan and the Unend-

ing War (London and New York: I.B. Tarius, 2003).

42. For more on this, see Sugata Bose, “Hindu Nationalism and the Crisis of the Indian State: A eoretical

Perspective” in Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal eds., Nationalism, Democracy, and Development: State and

Politics in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997); Paul Wallace and Ramashray Roy eds., India’s 1999

Election and 20th Century Politics (New Delhi: Sage Publication, 2003); and T.V. Paul ed., e India-Pakistan

Conict: An Enduring Rivalry, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

43. Singh, e Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.