SchoolTime Study Guide

National Acrobats of China

Tuesday, January 20, 2009 at 11 a.m.

Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley

2008-2009 Season

II |

On Tuesday, January 20, at 11:00am, your class will attend a performance of the

National Acrobats of China.

During the

SchoolTime

performance, the National Acrobats of China will astound the

audience with their mastery of this 2,000-year-old art form. Gymnasts, contortionists,

tumblers and jugglers will spin plates, perform balancing and aerial acts, create a bicycle

pagoda and juggle everything from balls to umbrellas with their hands, feet and entire

bodies.

Using This Study Guide

This study guide will help engage your students with the performance and enrich their

fi eld trip to Zellerbach Hall. Before coming to the performance, we encourage you to:

• Make copies of the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 -3 and pass them out to

your students several days before the show.

• Share the information on page 4 About the Performance & the Artists with

your students.

• Read to your students from the History of Chinese Acrobats (pages 8-10) and Facts

about China (page 11) sections

• Have your students participate in two or more of the activities on

pages 13-15

• Refl ect about the performance with your students by asking them

guiding questions on pages 4, 5 and 8.

• Use the glossary and resource sections on pages 16 & 15 to

immerse students even further in the art form.

At The Performance

Your students can actively participate during the

performance by:

• OBSERVING how the performers use their bodies

when working alone or in groups

• MARVELING at the skill & technique demonstrated

by the performers

• THINKING ABOUT all the practice and training that goes into each act

• NOTICING how the music and lights enhance the acts

• REFLECTING on the sounds, sights, and performance skills on display

We look forward to seeing you at

SchoolTime

!

Welcome to

SchoolTime

!

activities on

y

askin

g

them

&

15 to

oes

i

nto each ac

t

s

e

skills on display

1. Theater Etiquette 1

2. Student Resource Sheet 2

3. About the Performance & Artists 4

4. About the Art Form 5

5. History of Chinese Acrobats 8

6. Facts about China 11

7. Learning Activities 13

8. Glossary 16

9. California State Standards 17

About

SchoolTime

18

Table of Contents

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 1

1 Theater Etiquette

Be prepared and arrive early. Ideally you should arrive at the theater 30 to 45

minutes before the show. Allow for travel time and parking, and plan to be in your seats at

least 15 minutes before the performance begins.

Be aware and remain quiet. The theater is a “live” space—you can hear the

performers easily, but they can also hear you, and you can hear other audience members,

too! Even the smallest sounds, like rustling papers and whispering, can be heard throughout

the theater, so it’s best to stay quiet so that everyone can enjoy the performance without

distractions. The international sign for “Quiet Please” is to silently raise your index fi nger to

your lips.

Show appreciation by applauding. Applause is the best way to show your

enthusiasm and appreciation. Performers return their appreciation for your attention by

bowing to the audience at the end of the show. It is always appropriate to applaud at the end

of a performance, and it is customary to continue clapping until the curtain comes down or

the house lights come up.

Participate by responding to the action onstage. Sometimes during a

performance, you may respond by laughing, crying or sighing. By all means, feel free to do

so! Appreciation can be shown in many different ways, depending upon the art form. For

instance, an audience attending a string quartet performance will sit very quietly, while the

audience at a gospel concert may be inspired to participate by clapping and shouting.

Concentrate to help the performers. These artists use concentration to focus

their energy while on stage. If the audience is focused while watching the performance, they

feel supported and are able to do their best work. They can feel that you are with them!

Please note:

Backpacks and lunches are not permitted in the theater. Bags will be

provided for lobby storage in the event that you bring these with you. There is absolutely

no food or drink permitted in the seating areas. Recording devices of any kind, including

cameras, cannot be used during performances. Please remember to turn off your cell

phone.

2 |

Questions to Think About During the Performance

• What do the National Acrobats of China have in common with other

acrobats you’ve seen? How are they different?

• What elements of China’s culture, history or everyday life do you see in the

performance?

2 Student Resource Sheet

National Acrobats of China

The Performers

The National Acrobats of China are from

the People’s Republic of China. They are a

popular group that have been performing

all over the United States for over 50 years.

Objects of daily life—chairs, tables, poles,

ladders, bowls, plates, bottles, and jars—are

often used for props as the troupe performs

dazzling acts of acrobatics, contortion,

martial arts, drumming, dance and all-out

awe.

The Show

At the show the acrobats will perform

amazing acts like spinning plates on sticks,

juggling objects with their feet, balancing

human pyramids on top of moving bicycles,

twisting their bodies into all kinds of shapes,

and much more. The acrobats perform

alone (solo) or with others (in a group or

“ensemble”) All of the acts require strength,

fl exibility and concentration, but the group

acts also need the performers to cooperate

well with each other. If one person is

careless, it puts everyone in danger.

History of Chinese Acrobats

Acrobatics developed over 2,500 years

ago in the Wuqiao area of China’s Hebei

Province. As people didn’t have television

or other electronic inventions, they learned

new skills like acrobatics. Using their

imaginations, they took everyday objects

like tables, chairs, jars, plates and bowls and

practiced juggling and balancing with them.

Acrobatic acts became a feature at

celebrations, like harvest festivals. Soon the

art form caught the attention of emperors

who helped spread the acrobats’ popularity.

As their audience grew, acrobats added

traditional dance, eye-catching costumes,

music and theatrical techniques to their

performances to make the experience even

more enjoyable.

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 3

Facts about the Performers

• The performers in the troupe range in age from 17 to 22. Some of them started

training at fi ve years old.

• The group was started in 1956.

• There are 35 members of the National Acrobats of China. Following Chinese

custom, the company works together like a family. No one gets special “star”

treatment.

• During the show, each performer makes at least six or eight costume changes.

• It takes up to three months to create one of their costumes, from design to fi nished

product.

Acrobatic Families

Like European acrobatic troupes, many Chinese troupes were family-owned, and

several still are today. Family troupes would keep the techniques of their acts secret,

teaching them only to their children and other close relatives. Touring the countryside

as street performers, certain families became successful for their signature acts. Two

famous acrobatic families were the

Dung family, known for their magic acts, and the

Chen Family, known for their unique style of juggling.

Acrobatics in the People’s Republic of China

In October 1949, a communist government came into power in China. China’s

companies and businesses became the government’s property, including the acrobatic

troupes. Since acrobatics was considered an art form that was popular with all people,

not just the rich or educated, the government supported acrobatic troupes, and even

gave money to create new troupes in different regions of the country. However,

government ownership also meant that troupes had less artistic freedom and individual

acrobats didn’t have a choice about where they worked or who they worked with.

Today, in the “new” China, acrobats have made great improvements in both the

staging and skill of their art form. Companies use music, costumes, props and lighting

to create striking and imaginative stage productions.

Acrobatic Training

There are as many as 100,000 people who attend special acrobat schools in China

today. Students start training at age fi ve or six, working from early in the morning to

late afternoon, six days a week. Students learn and then continue developing the four

skills which are an acrobat’s foundation: handstand, tumbling, fl exibility and dance.

After almost 10 years of hard training, the most talented students join professional

city-wide troupes, and only a few of these skilled performers are then chosen to be

part of internationally known companies like the National Acrobats of China.

4 |

The company tours the world for

approximately seven months out of each

year. Tours include cities from Amsterdam

to Zurich. Other international circuses

and troupes have adopted some of the

company’s signature acts, in particular,

“Cycling Stunts,” “Plates Spinning,” “Aerial

Silk” and “Icarian Boys.”

The current director is Mr. Gui

Zhongshan, and Mr. Tian Zichun and Mr.

Jianguo Yao are deputy directors.

Guiding Questions:

What qualities are unique to the National Acrobats of China? ♦

What are some of the things the acrobats will do at ♦

SchoolTime

?

3 About the Performance & Artists

National Acrobats of China

The National Acrobats of China’s

SchoolTime

performance features

theatrically staged acts of astounding

acrobatics and Chinese traditional dance.

Contortionists, tumblers and jugglers will

spin plates, create a bicycle pagoda and

juggle everything from balls to umbrellas

using not only their hands but also their

feet and sometimes their entire bodies.

Please see page 5 in “About the Art

Form” for a list of acrobatic feats that may

be included in this performance.

“Timeless thrills . . . the impossible can

be achieved, and once achieved surpassed,

then surpassed again” (Associated Press).

The National Acrobats of China

The award-winning National Acrobats

of China is a troupe of 35 performers from

China.

The company has entertained

audiences across the world for over 50

years and has won over twenty international

awards. Founded in 1956, the National

Acrobats of China is internationally

acclaimed for its for juggling, cycling and

acrobatic skills. Some of the acts it is known

for include its “Bench Juggling with Feet”

and “Clownish Straw Hats,” both of which

have won awards.

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 5

Acrobatic Artistry

4 About the Art Form

Guiding Questions:

What kinds of props do acrobats use and how do they use them? ♦

How is Chinese culture refl ected by the acrobats’ on stage? ♦

What are the four basic acrobatic skills? ♦

The acrobatic arts have evolved

for over 2000 years in China, a country

credited with producing some of the

best acrobats in the world. Chinese

acrobats maintain a notable style and

standard routines. Chinese acrobats

learn handstands, juggling, trapeze, and

balancing, and, as in most recognizable

circuses around the world, also maintain

juggling, trapeze, handstand acts and

comic relief. Differences between troupes

are refl ected in theatrical presentation,

including music, novelty acts such as

clowns, and lighting.

Acrobatic Training and Handstands

In China, acrobats are selected

to attend special training schools at

about age six. Students work long and

challenging hours six days a week. The

fi rst two years of acrobatic training are the

most important. They practice gymnastics,

juggling, martial arts and dance in

the mornings, and then take general

education classes in the afternoons.

Students work daily on core skills:

the handstand, tumbling, fl exibility, and

dance. They are also expected to be

skilled in juggling.

Each student will have a more

pronounced talent for one of the four

core acrobatic skills. The handstand

is considered the essence of Chinese

acrobatics. Many signature acrobatic

acts include some form of handstand.

Master teachers have commented that,

“handstand training is to acrobats what

studying the human body is to a medical

student.”

6 |

Signature Chinese Acrobatic Acts

Acrobatic acts can be performed

solo or in groups. Group acts require

team cooperation, trust and constant

communication.

The disadvantage of a group act is that

when one acrobat cannot perform or leaves

the act this puts the others at risk in their

careers, and they must start over again. But,

at least the new acts or new specialties they

develop are based on central acrobatic skills;

tumbling, fl exibility, handstand and dance.

The

SchoolTime

performance of

National Acrobats of China may include

the following acts:

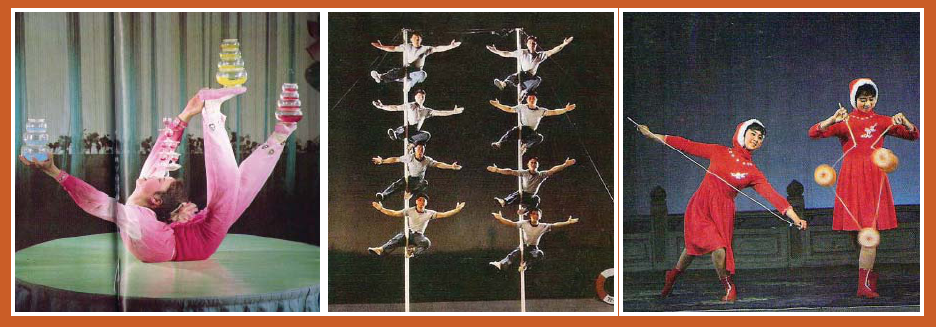

Spinning Plates: Thirteen acrobats spin

plates on two iron sticks, dancing all the

while.

Contortion: Performers twist into

unbelievable knots while balancing

precariously perched objects.

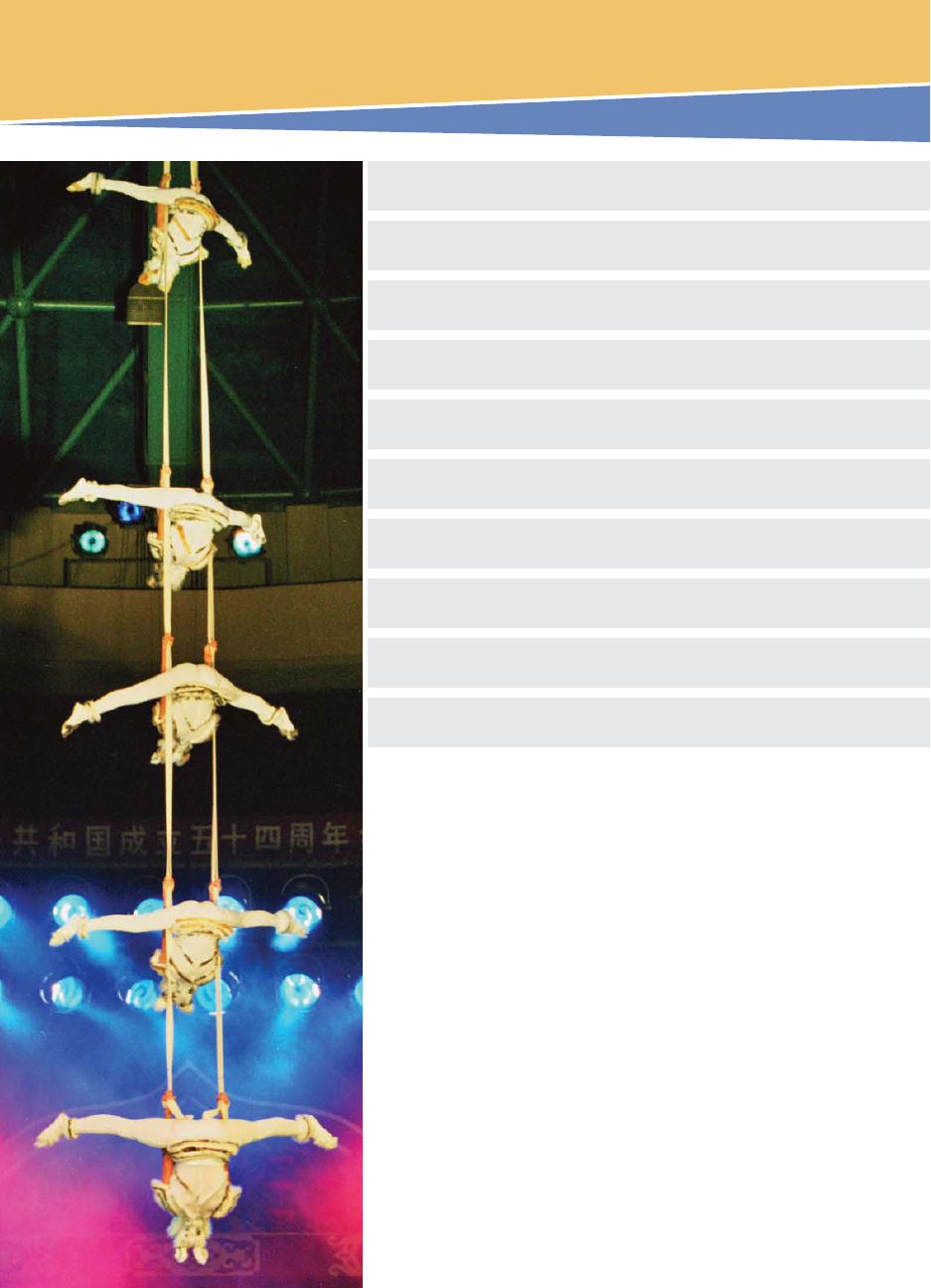

Leather Straps: Using great strength,

four men suspend and balance themselves

in midair with leather straps.

Hoop Diving: With dynamic speed and

rhythm, twelve acrobats jump, dive and

tumble through stacked hoops up to 7 feet

high.

An acrobat trains in progressive

steps from basic to advanced handstands.

Training directly affects three areas of the

body— shoulders, lower back, and wrists.

A weakness in any one area compromises

the acrobat’s ability. Beginning students

begin by doing handstands against a wall.

In three to six months, they build up to a

half hour of wall handstands. The three

areas of the body become stronger until

at last students are able to hold the free

handstand.

In Chinese, holding a still handstand

is translated as a “Dead handstand.” A

good handstand has pleasing form and

versatility, meaning the acrobat can

execute many variations from that position.

Understandably, young acrobats fi nd

this early training unpleasant. In a basic

handstand, one is upside down with all the

body’s weight on the wrist, shoulder and

lower back. There is natural pressure to

want to come down and, since the hands

are the body’s only support, there is no way

to cheat.

After the initial two-year training, only

a few acrobats specialize in the handstand.

However, handstand training is essential to

all acrobatic work, due to the role it plays

in strengthening the body, mind and spirit

of the acrobat.

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 7

Aerial Silk: A romantic aerial act

featuring a man and woman who perform

acrobatic tricks while hanging from strips of

silk.

Single Hand Balancing: On top of a

perch, a performer balances her entire body

using the strength of one arm.

Grand Acrobatics & Martial Arts:

The entire company creates pyramids

and performs spectacular balancing

and tumbling acts while a martial arts

performer displays his martial arts skills.

Straw Hats Juggling: Ten acrobats

juggle, throw and catch hats in a

breathtaking performance.

Balance on Benches: In this traditional

Chinese circus act that is rarely seen today,

acrobats balance several benches on their

feet.

Diablo: Performed in China for over 1,000

years, two acrobats perform tricks with a

kind of yo-yo connected with string to sticks

of bamboo.

Russian Bar: Acrobats do somersaults

and other feats on a beam that is balanced

on the shoulders of two performers.

Icarian Acrobatics: Performers tumble

and do somersaults on each other’s feet.

Acrobatics of Five: Contorting and

balancing their bodies, performers create

beautiful stage pictures.

Lasso: Performers show off their mastery

of ropes in a series of tricks.

Bicycle: Sixteen acrobats perform on

moving bicycles.

8 |

5 Acrobatics in Chinese History

Guiding Questions:

How did acrobatics become popular in China? ♦

What are some common traits of acrobatic troupes? ♦

How have Chinese political and social changes affected acrobatics? ♦

Acrobatics is a time-honored

art form in China. With a long and rich

history, acrobatics has become one

of the most popular art forms among

the Chinese people. Some historical

records provide evidence for the

development of this art form as far back

as the Xia Dynasty (4,000 years ago),

though is more likely that acrobatics

were not developed until approximately

2,500 years ago when its impressive

physical feats caught the attention of the

country’s powerful emperors.

Acrobatic arts were developed

during the Warring States Period

(475BC-221BC), evolving from the

working lives of people in Wuqiao

(pronounced oo-chow) county of Hebei

Province. Acrobats fi rst used everyday

items around them—instruments of

labor such as tridents, wicker rings and

household articles like tables, chairs,

jars, plates and bowls—as performance

props in balancing and juggling acts.

At a time when China was an

agricultural society, when there were

no distracting electronic gadgets

or telephones, people used their

imaginations to practice skills of

acrobatics: handstands, tumbling,

balancing, juggling, and dancing. Their

acts were incorporated into community

celebrations, for example, to celebrate a

bountiful harvest. These entertainments

eventually evolved into well-appreciated,

professional performances.

Most of Chinese history is studied

as Dynasties, periods known by the

names of their rulers. During the Han

Dynasty (221BC-220AD) home-made

rudimentary acrobatic acts developed

into the “Hundred Entertainments,”

followed by many variations. Music and

other theatrical elements were added as

interest in the art form grew among the

emperors.

People’s Republic of China

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 9

Historic records on stone

engravings from Shandong Province

unearthed in 1954 show acrobatic

performances with musical

accompaniment on stages of 2,000 years

ago, including acts that are familiar to

this day, such as Pole Climbing, Rope-

Walking, conjuring and

Balancing on

Chairs

.

In the Tang Dynasty, known for

the extraordinary fl ourishing of Chinese

culture, the number of acrobats increased

and their performing skills improved

through prolonged practice. Famous

poets of that time, Bai Juyi and Yuan

Chen, wrote poems about acrobatic

performances. In a painting at Dunhuang

called “Lady Song Going on a Journey,”

there are images of acrobatic performers.

Since these early times, acrobatics

have been incorporated into many forms

of Chinese performance arts, including

dance, opera,

wushu

(martial arts) and

sports. Acrobatics have gone beyond the

boundaries of performance, serving an

important role in the cultural exchange

between China and other Western nations

including the United States. Today, China

presents acrobatics in the international

arena as an example of the rich traditions

of Chinese culture and the hard-working

nature of the Chinese people.

Family Acrobatic Troupes

Traditional acrobatic troupes were

family-owned, making their living roaming

the countryside as street performers.

Many famous acrobats continued this

lifestyle through many generations,

including the Dung family and the Chen

Family. The Dung Family was known for

their magic acts, while the Chen Family

was famous for their unique style of

juggling, with a signature act that used

as many as eight badminton rackets at

one time. Other acrobatic troupes have

tried to match the skill level of the Chen

family’s juggling feats with little success.

Family acrobatic troupes would teach

only their own children and close relatives

their secrets to keep the techniques and

traditions within the family last name.

(This was also the case in Europe, where

circus families continued through many

generations).

The mural

An Outing

by the Lady of Song of the Tang Dynasty

(618-907) depicts the grand scene of a Peeress’s outing. Walking

in front of the large procession is an acrobat doing pole balancing

with four young boys doing stunts. These fi gures are vivid, lively

and vigorous, and is considered the most complete extant

Chinese mural containing images of acrobatics.

10 |

Acrobatics in China after 1949

On October 1, 1949, the People’s

Republic of China was formally established

by the Communist party, with its national

capital at Beijing. All companies and

businesses became government property,

including the family acrobatic troupes.

The people’s government made great

efforts to foster and develop national arts.

Generally, the Communist government

approved of acrobatics as “an art of

the people,” not an elitist art form, so

acrobatics gained a new prominence as

every province, municipality and region

established its own acrobatic troupe.

In Communism, everyone is

supposed to be provided for and taken

care of equally; the term “Iron Rice Bowl”

means all eat out of the same rice bowl.

(However, there were inconsistencies

between Communist theory and practice,

as people in powerful government

positions received many perks).

Under Communism, the government

paid for acrobatic troupes’ operational

costs, so performers didn’t need to worry

about their fi nancial earnings. They

concentrated on improving their skills

and enhancing the contents of their

performances.

Modern acrobatic acts are designed

and directed with the goal of creating

graceful stage images. Harmonious

musical accompaniment and the added

effects of costumes, props and lighting

turn these acrobatic performances into

exciting full-fl edged stage art.

Recent changes in China’s

government allow artists more

freedom to be creative, which has led

to improvements in the working lives of

acrobats. Now, acrobats are permitted to

form their own performing groups, and

to perform for their own fi nancial gain.

Individual acrobats can now perform later

into adulthood.

There are now over 100 acrobatic

troupes operated by the Chinese

government and hundreds more private

troupes performing the ancient art of

Chinese acrobatics both in China and all

over the world.

At present, Chinese acrobats refl ects

the optimism, determination, the industry,

resourcefulness, courage and undaunted

spirit of the Chinese people.

Mao Tse-Tong (1893–1976), founder of the People’s Republic

of China, greets Chinese acrobats.

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 11

Size

The fourth largest country in the

world, China is slightly smaller than the

United States. Its population of 1.3 billion

is the largest in the world—more than

four times that of the U.S.

Population Control

Married people of the Hun majority

(92% of the population) are allowed to give

birth to only one child except if the parents

are both single children themselves (then

they may have two). Minority families may

have as many children as they wish.

Changes in Government

Imperial rule—dynasties ruled

by emperors—began in 1111 B.C. An

Emperor ruled until he died or passed

leadership on to a son or nephew. Most

of Chinese history is recorded by the

family names of the dynasties. During

most of recorded history —through

the 15th century— China was the most

advanced country in the world in terms of

technological development and culture.

In 1911, a revolution ended over

2000 years of imperial rule. By 1921 the

Communist Party of China was founded.

In a Communist state, all businesses,

property, foods, goods and services are

owned and operated by the government

and distributed to the people by the

government.

Over the last 30 years, the Chinese

government has changed to a unique

political blend. China maintains a

communist government within a socialist

society and a capitalist economy. The

opening up of China to Western ideas

has dramatically affected its people. A

gap is widening between rich and poor,

rural and urban, and eastern and western

China. As more of the world’s products

are being manufactured there, China’s

gross national product has grown as

much 10% over the last few years. After

the United States, China now is the

second largest economy in the world.

Pollution

No country has ever emerged as a

major industrial power without damaging

the environment. Because of its huge

growth, China’s pollution problems have

shattered all precedents. 70% of the

water in China is polluted and only 1% of

the 560 million city dwellers breathe air

that it considered safe. The Chinese are

working hard to counter the affects of this

tragic situation.

6 Facts about China

Reprinted with permission from the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts

12 |

Symbols of Old and New China

The Great Wall of China was built and

rebuilt between 5th century BCE and 16th

century AD to protect the northern borders

of the Chinese Empire. It is the world’s

largest man-made structure. Some of its

stretches have been restored enough for

people to walk along today.

The Temple of the Heavens in Beijing

was the site of annual ceremonies of prayer

for good harvest during the Ming and Qing

dynasties. One of the few antiquities saved

during the Cultural Revolution, its extensive

grounds are now used as a public park.

The Chinese were excited to host

the 2008 Olympic games in Beijing and

surrounding areas. The government

made many improvements to the city,

from thousands of new trees planted and

new hotels built to old sites renovated

for tourists. Based in Bejing, portions of

the Olympic games were played in other

regions of China. The games allowed many

of the world’s people to see inside China for

the fi rst time.

Schools in China

China has the largest educational

system in the world — over 1,170,000

government-run schools enroll over

318,000,000 students.

It has an increasingly literate

population, recorded in 2001 at 90%.

Educational progress has been most

rapid in the urban areas such as Beijing

and Shanghai because of their greater

resources. Since 2001, there has been a

curriculum reform effort towards more

student-centered programs and the

government has allowed regions to set

some of their own courses.

Children start school at age six and

attend for nine years. Primary education

is free, but parents pay for everything

from paper to electric bills. Parents pay

for secondary education. To continue into

high school, students must do well on a

series of tests. It is steeply competitive

to get into the best schools. Vocational

schools are now available for students

who do not go on to universities.

Average classes have 60 students.

Discipline problems are reportedly rare

because parents insist that children must

respect their teachers. In such large

classes, the instruction is largely didactic

and teacher-centered. Every student in

China does morning exercises before

school and at a given time during the

school day. Students in secondary schools

wear unisex school uniforms. All students

learn the craft of painting and drawing.

Left to right: Temple of Heavens in Bejing; 2008 Olympic logo; Chinese students

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 13

7 Learning Activities

Pre-show Activities

An effective way to engage your students in the performance and connect to literacy,

social studies, arts and other classroom curriculum is to guide them through these

standards-based activities before they come to the show.

Performance and Culture

Questions for Students:

1. How long have acrobatics existed in China?

2. At what age do acrobats typically begin training in China?

3. What types of props are used in acrobatic routines?

4. Can you name three major cities in China?

5. Why do acrobats wear colorful costumes?

6. Name the 4 acrobatic skills learned in basic training.

7. Name 5 acrobatic acts created in China.

8. What are the “3 P’s” common to the secrets of learning acrobatics and becoming a

good student?

Younger elementary students:

Practice, Practice, Practice

Older students and adults:

Practice, Perseverance, Patience

9. Think of one word to describe acrobatics.

10. Can you remember a major Chinese holiday celebration that features acrobats?

Performing Arts (Grades K-6)

Object Balancing: Activity and Refl ection (Grades K-6):

Teacher Prep: Make newspaper sticks for each student. To make a stick, take two

large sheets of newspaper, roll them up as tightly as possible and tape them in the

middle and at the ends. Ask students to:

• Place their “newspaper sticks” on the palms of their right or left hand and try to

keep it balanced and upright.

• After doing this for a few minutes, ask them to refl ect on what it was like.

• Discuss the acrobats’ training – the practice and work that goes into developing

their skills.

14 |

Human Sculptures: Activity, Discussion and Kinesthetic Refl ection (Grades K-8)

Invite students to imagine their bodies are like clay and they can mold them into

different shapes (like triangles, circles, and objects like tables, fl owers or ladders.)

• On their own, ask them to experiment with using high, medium and low levels when

creating shapes, and encourage them to use their entire body.

• Then, have students work in pairs or in groups to create more shape and object

sculptures.

• Afterwards, discuss as a class the difference between making the shapes by

themselves and with others.

• Ask students to look for the shapes the National Acrobats of China make with their

bodies during their performance. After the performance, invite students to remember

one shape that stood out in their memory and imitate this shape. Ask the entire class to

imitate this movement after the student has shown it.

Post-show Activities

Refl ecting on the performance allows students to use their critical thinking skills as they

analyze and evaluate what they’ve observed during the performance. Student refl ection also

helps teachers assess what students are taking in, and what they aren’t noticing.

Visual Arts & English Language Arts (Grades K-6)

Discussion and Activity:

Ask students to think about the National Acrobats of China’s performance.

• Which act was their favorite? Discuss what they liked best about the show and why.

• Invite students to create an advertisement for the National Acrobats of China’s

performance. They should include an illustration and description (or a “quote” from a

made-up review) that refl ect the best part of the show.

Social Studies (Grades 3-12)

Headlines about China

There are often news stories about China.

• Ask students to search for news about China on television, radio, the internet,

newspapers or magazines. They may make up their own headlines or write a one

paragraph version of stories they’ve seen or heard.

• Have students share their news stories about China with each other and then

discuss the current events and topics.

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 15

Extensions:

• As a class, choose articles that are most interesting to the students. In groups

of four or fi ve, have students research the topic in more depth, and share a brief

presentation with the class.

• Ask students to brainstorm together what they know about China, the Chinese

people, and the Chinese government. Invite them to write a few paragraphs about what

it might be like to live in China. In what ways might it be different from the way they live

here?

Common sayings in acrobatic training schools:

“Seven minutes on stage is equal to ten years of training.”

“One must be able to enduring suffering to become a good acrobat.”

“Not too fast, not too slow: you need to be patient and to follow the middle road to fi nd

success in your acrobatic skills.”

References

Books:

The Best of Chinese Acrobatics

by Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, China.

Websites:

www.redpanda2000.com

www.Cirque du Soleil.com

www.ringling.com

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74xg3VUZhoI&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kt3b8xYdA-A&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fkNeRYRlXY&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GfC9p3CU1PQ&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qpa3NjYaEWc&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qmvDL6qlCI&NR=1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enFBCCjT9Ms&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74xg3VUZhoI&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kt3b8xYdA-A&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qmvDL6qlCI&NR=1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enFBCCjT9Ms&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpqDgPbsVTE&feature=related

16 |

8 Glossary

acrobat: a skilled performer who does

gymnastic feats like handstands, tumbling,

tightrope walking and trapeze work

agility: being able to move quickly and

easily

aerial act: performance acts that take

place high in the air

choreographer: a person who creates the

movements for dances

comic relief: a funny scene in between

dramatic or suspenseful moments in a

performance

conjuring: to perform magic tricks like

slight of hand where something appears

out of nowhere

contortionists: a fl exible performer who

can move their muscles, limbs and joints

into unusual positions.

gymnast: a trained athlete who displays

physical strength, balance, skill and agility

Hundred Entertainments: shows

performed 3,000 years ago in China that

included acrobatics, song and dance

numbers, comedy, magic and instrumental

music

martial arts: a traditional Asian self-

defense or combat sport that doesn’t use

weapons but depends on physical skill and

coordination (Karate, aikido, judo, and

kung fu are considered martial arts.)

novelty act: a new and interesting

performance piece that appears different

from what is usually seen

signature act: a performance piece

connected with, or made famous by, a

specifi c company or troupe

somersault: when someone rolls their

body forward or backward in a complete

circle with their knees bent and their feet

coming over the head

trapeze: a short horizontal bar suspended

from two parallel ropes, used for

gymnastic exercises or for acrobatic

stunts.

troupe: a company or group of performers

that works, travels and performs together

SchoolTime

National Acrobats of China

| 17

Theater:

3.0 Historical and Cultural Context: Students

analyze the role of development of theater,

fi lm/video, and electronic media in the past

and present cultures throughout the world.

Noting diversity as it relates to the theater.

K.3.1 Retell or dramatize stories, myths,

fables, and fairy tales for various cultures and

times.

4.3.1 Identify theatrical or storytelling

traditions in the cultures of ethnic groups

throughout the history of California.

5.0 Connections, Relationships, and

Applications: Students apply what they

learn in theater, fi lm/video, and electronic

media across subject areas. They develop

competencies and creative skills in

problem solving, communication, and time

management that contribute to lifelong

learning and career skills. The also learn

about careers in and related to theater.

Physical Education:

Standard 1: Students demonstrate the motor

skills and movement patterns needed to

perform a variety of physical activities.

K.1.6 Balance on one, two, three, four, and

fi ve body parts.

1.1.6 Balance oneself, demonstrating

momentary stillness, in symmetrical and

asymmetrical shapes using body parts other

than both feet as a base of support.

5.1.1 Perform simple small-group balance

stunts by distributing weight and base of

support.

6.1.11 Design and perform smooth, fl owing

sequences of stunts, tumbling, and rhythmic

patterns that combine traveling, rolling,

balancing, and transferring weight.

Standard 2: Students demonstrate knowledge

of movement concepts, principles, and

strategies that apply to the learning and

performance of physical activities.

4.2.10 Design a routine to music that includes

even and uneven locomotor patterns.

4.3.1 Participate in appropriate warm-up and

cool-down exercises for particular physical

activities.

Standard 3: Students assess and maintain a

level of physical fi tness to improve health and

performance.

3.5.3 List the benefi ts of following and the

risks of not following safety procedures and

rules associated with physical activity.

9 California State Standards

18 |

About Cal Performances

and

SchoolTime

Cal Performances’ Education and Community Programs are supported by Above Ground Railroad Inc., Bank of

America, The Barrios Trust, Earl F. and June Cheit, Shelley and Elliott Fineman, Flora Family Foundation, Fremont

Group Foundation, The Robert J. and Helen H. Glaser Family Foundation, Jane Gottesman and Geoffrey Biddle, Evelyn

& Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, Kathleen G. Henschel, Beth Hurwich, Kaiser Permanente, David L. Klein Jr. Foundation, Carol

Nusinow Kurland and Duff Kurland, Macy’s Foundation, Susan Marinoff and Thomas Schrag, Maris and Ivan Meyerson,

Pacifi c National Bank, Kenneth and Frances Reid, Jim and Ruth Reynolds, Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld,The San Francisco

Foundation, Nancy Livingston and Fred Levin, The Shenson Foundation, Sharon and Barclay Simpson, Wells Fargo

Foundation, Wilsey Foundation, and The Zellerbach Family Fund.

Cal Performances Education and Community Programs Sponsors

The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong

appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter

of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and

commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University

and the broader public through performances and education and community programs.

In 2005/06 Cal Performances celebrated 100 years on the UC Berkeley Campus.

Our

SchoolTime

program cultivates an early appreciation for and understanding of the

performing arts amongst our youngest audiences, with hour-long, daytime performances

by the same world-class artists who perform as part of the main season.

SchoolTime

has

become an integral part of the academic year for teachers and students throughout the

Bay Area.

This Cal Performances

SchoolTime

Study Guide was written,

edited and designed by Laura Abrams, Rica Anderson

and Nicole Anthony, and Wayne Huey.

Cal Performances

gratefully acknowledges the Flynn Center for the Performing

Arts and the Education Department of the State Theatre,

New Brunswick, NJ for granting permission to reprint

excerpts from their education guides.

Copyright © 2008 Cal Performances