Georgia State University Georgia State University

ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University

Film, Media & Theatre Theses School of Film, Media & Theatre

5-13-2021

(Not So) Innocent Bystander: The Embodied Views of the Body (Not So) Innocent Bystander: The Embodied Views of the Body

Camera Camera

Kristina Jespersen

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_theses

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Jespersen, Kristina, "(Not So) Innocent Bystander: The Embodied Views of the Body Camera." Thesis,

Georgia State University, 2021.

doi: https://doi.org/10.57709/23986780

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @

Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Theses by an authorized

administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact

(NOT SO) INNOCENT BYSTANDER: THE EMBODIED VIEWS OF THE BODY CAMERA

by

Kristina Jespersen

Under the Direction of Jennifer Barker, PhD

ABSTRACT

As police brutality cases have become more discussed over the past several years, there

have been many debates surrounding the police body camera, but thus far, little research has

been done on the body camera’s relation to semiotics and phenomenology. Through an analysis

of the body camera’s indexicality and embodiment, this thesis aims to dismantle the argument

often proposed by law enforcement that the body camera is a purely observatory, evidential piece

of technology. To best identify the complications that the body camera presents, the thesis

compares three different instances where body camera footage was released to the public and

how each set of footage functions.

INDEX WORDS: Phenomenology, Semiotics, Body camera, Media studies

(NOT SO) INNOCENT BYSTANDER: THE EMBODIED VIEWS OF THE BODY CAMERA

by

Kristina Jespersen

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Arts

in the College of the Arts

Georgia State University

2021

Copyright by

Kristina Jespersen

2021

(NOT SO) INNOCENT BYSTANDER: THE EMBODIED VIEWS OF THE BODY CAMERA

by

Kristina Jespersen

Committee Chair: Jennifer Barker

Committee: Alessandra Raengo

Jade Petermon

Electronic Version Approved:

Office of Academic Assistance

College of the Arts

Georgia State University

August 2021

iv

DEDICATION

For Mom, who is always watching over me. I love and miss you.

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Dr. Jennifer Barker, Dr. Alessandra Raengo, and Dr. Jade Petermon for

their help with this thesis. To my friends who constantly listen to my theorizing, thank you for

your endless support. Mary and Mike Feeney, thank you for standing in my corner and

accompanying me through the good and the bad; your help has been invaluable throughout my

journey. And, as always, thanks to my dad, who is always cheering me on no matter what.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ V

LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... VII

1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 1

2 AGGRESSIVE/PASSIVE EMBODIED VIEWS ................................................... 7

3 A SEMIOTIC APPROACH................................................................................... 23

4 PHENOMENOLOGY, EMBODIMENT & THE BODY CAMERA ................ 34

5 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................... 46

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 50

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 ........................................................................................................................................... 9

Figure 2 ......................................................................................................................................... 10

Figure 3 ......................................................................................................................................... 12

Figure 4 ......................................................................................................................................... 13

Figure 5 ......................................................................................................................................... 14

Figure 6 ......................................................................................................................................... 17

Figure 7 ......................................................................................................................................... 18

Figure 8 ......................................................................................................................................... 19

Figure 9 ......................................................................................................................................... 19

Figure 10 ....................................................................................................................................... 20

1

1 INTRODUCTION

In the summer of 2020, following the death of George Floyd, there was a noticeable

increase in conversations surrounding police brutality and the body camera. As more members of

the public educated themselves about police brutality, many began questioning just how helpful

the body camera is to preventing police misconduct. Body cameras are often included within

discourse surrounding police brutality, but after the events of 2020, many were left wondering

just how beneficial body cameras are, especially since the public typically receives news of

police brutality cases via other forms of surveillance, usually a bystander’s cell phone camera.

The police body camera presents an interesting dilemma: it is intended to provide “protection

against” cases of police brutality in that it aims to hold officers accountable for their actions,

acting as a third eye which is always watching, but since body camera footage is typically only

released following an instance of misconduct, the argument for its use appears to be null.

Additionally, with the camera—literally a body camera—attached to an officer’s figure, it feels

inane to claim the camera is objective when it provides an embodied view. This predicament

lends the questions: How the does the embodiment of these cameras affect the viewer’s

perspective of the events unfolding in real time? And does the embodied perspective prevent the

body camera from remaining an “objective third eye?”

In this thesis, I utilize semiotic and phenomenological approaches to answer these

questions and to disprove the claim that the camera is an objective piece of technology. Through

analysis of the varying embodied perspectives that the body camera provides, it quickly becomes

clear that whoever views footage taken from a body camera is unable to view the images they

see as purely “objective.” If this thesis seems to rely heavily on the experience of the

particular—not generic or universal—“we,” this is due to time constraints rather than

2

methodology. Though the project begins with my own perception of body camera footage, by

considering my own phenomenological experience of it, I discover aspects of the footage that

call for semiotic analysis; this analysis reveals patterns/structures in the footage that others can

see, informed by their own lived experience in the world. Through a combination of

phenomenological description and semiotic analysis, I seek to emphasize how any approach to

these images and the discourse surrounding them always stems from a personal, embodied view

of the world. In the instances within this thesis, I include myself in that “we,” and the

perspectives considered here are influenced by my own identity and political affiliation [white,

female, college-educated, liberal/democratic.]. Through utilizing my personal perspectives and

phenomenological experiences with the objects studied here as a starting point, I demonstrate

how the phenomenological and the semiotic can be paired together to construct meaning and

identify the complexities of body camera images.

This thesis begins with an examination of three recent uses of body camera footage and

analyzes the differing ways we approach footage based on the context of the case. The three

cases analyzed in the first chapter are the January 2021 Capitol riots, Anjanette Young’s home

invasion by Chicago police in 2019, and the documentary, American Murder: The Family Next

Door (Popplewell, 2020). The use of body camera footage in each of these cases presents

contrasting uses of force (passive/aggressive) and a comparison of how officers (and their

cameras) move in different spaces and/or situations and how they interact with different subjects.

Respectively, the footage from the Capitol riots offers an embodied view of an officer being on

the receiving end of aggressive actions, the footage from the unlawful raid of Anjanette Young’s

home shows aggressive invasion via the embodied view of multiple perpetrators, and the body

camera footage used in American Murder offers audiences an embodied view of officers

3

passively entering a premises and calmly questioning a (white) suspect. The differing embodied

views that the observer witnesses in each of these cases provide examples of the thesis’ overall

questions surrounding the images that the body camera presents and the insights that these

embodied views provide to the general public about police officers’ presence in different spaces

and around different persons.

In the second chapter, I turn to a semiotic approach while still discussing the outlined

examples from chapter one. Referring to Pierce, Doane and other scholars who have previously

discussed the complications of the semiotic (more specifically, the index of an image), this

chapter aims to trace what the index of the body camera’s captured image is and how viewers

and scholars may approach body camera footage when questioning its objectivity. I also briefly

turn to Baudry’s writing on psychoanalytic semiotics in order to bridge semiotic questions of

identification with the phenomenological approach that is explored in the subsequent chapter.

The third and final chapter examines the embodiment of the body camera and

investigates the relationship between the camera and the body of the officer who wears it. This

exploration also demonstrates how viewers respond to the embodied footage and refers back to

the first chapter’s three differing cases as examples of how embodied perspectives shift

depending upon context. In this chapter, I refer to Vivian Sobchack’s writing on documentary

and modern technology as well as Teresa Castro’s writing on machinic subjectivity and the

invisible (quasi)subject. Through a discussion of camera as embodied subject and as an object

which is affected through an operator’s own embodiment, the chapter will introduce the different

complexities attached to the body camera. The main source of conflict is the body camera’s

objectivity clashing with the embodied perspective of the police officer/operator’s body.

Applying the phenomenological method to our analysis of body camera footage and defining the

4

“work” that the body camera does alongside the actions of its “actor” (the body which wears it)

may better exemplify how the body camera cannot be considered a purely objective piece of

technology.

Before moving forward with the examples of body camera footage and my application of

semiotic phenomenology, I find it beneficial to review the history and technology behind the

police body camera. In order to better understand the arguments made throughout the main

chapters, it is important to first outline how the body camera came into major use and how the

technology behind the device works. In 2014, following the death of Michael Brown in

Ferguson, Missouri, the Brown family publicly called for police departments to use body

cameras. According to data from Axon—the main provider of body camera technology in the

U.S.—there was a significant increase in body camera purchases that year. The largest increase

in body camera purchase and use, however, came over one year later when the Obama

administration and the Department of Justice created grants which helped law enforcement

departments pay for the necessary technology. Axon has been manufacturing and selling body

cameras since 2010, but its sales revenue shows that the real increase in body camera purchases

by police departments came in 2016, after the Department of Justice grants were put into effect

(Miller). Since 2016, it has become common practice for officers to wear a body camera at all

times, though the regulations surrounding when and for how long a camera is turned on vary

across different police forces.

Much of the recent academic writing surrounding the body camera is found in law

studies—in their writing, these scholars consider the stakes involved with using body cameras,

question the ethical implications of a “third eye,” and review the statistical benefits and/or

disadvantages of body camera usage in the police force. In her analysis of the body camera’s

5

success/failure in improving American policing, author Connie Felix Chen provides background

information on the police body camera, highlighting the large number of police brutality cases

that occur each year in the United States, and what the legal costs of these cases typically are.

Chen notes that in the year 2010, “the United States government spent over $346 million on

misconduct-related judgment and settlements,” which provides context as to why police forces

and the government—always concerned with finances and profit—are willing to have their

officers wear surveillance gear (Chen 150). It is important to keep in mind the financial aspects

of the body camera and how financial loss affects the use of these devices; it is obvious that the

police view the device as a way of protecting themselves from allegations which can lead to

severe financial repercussions.

The body camera “consists of a video camera, a microphone, a battery, and onboard data

storage system” (155). The camera is lightweight and typically worn on the officer’s chest. This

placement allows the camera, unlike CCTV or dash cams, to more closely provide a look at the

officer’s perspective of different interactions. The position not being at eye level, however, does

provide the third-person point of view which enables the device to be more “objective.” The

onboard data storage system sends footage straight to cloud storage and has “built-in security

features to protect against tampering,” preventing an officer from being able to edit any footage

captured by their camera (156).

Chen also refers to a 2015 study conducted by the Department of Homeland Security

which identified the best body camera models and provided police departments across the

country with suggestions for which models to purchase for their officers. The guidelines set by

this study emphasized the importance of high image quality, audio recording, and the ability to

record at least 3 hours’ worth of footage at a given time (158). While this study aimed to set

6

guidelines for body camera usage, there are still many different issues that have cropped up as

more departments have begun using the devices. Chen notes common complaints made about the

body camera, both by officers and by civilians. Importantly, she makes note of the on/off button

which can be manipulated by the officer. Since this article was written, the officer’s ability to

control when he/she operates the camera has changed, especially in light of the power button

surfacing more and more in recent conversations about the body camera, notably after officers

either shut their body cameras completely off or taped over the lens at Black Lives Matter

protests. Other complaints made about the devices include poor image quality, limited visibility

of a location, poor camera angles, and lag in recording. Because of these recurring issues, Chen

argues, the body camera cannot be a totalistic “fix” for police misconduct. While the body

camera can, in some cases, prevent an officer from abusing their power, its presence does not

erase the institutional racism that the police force operates under. And even if abuse of power is

caught on camera, how the department responds to that footage is also questionable. Chen

wonders what happens to instances of abuse that are seen within the department but never

released to the public.

Keeping in mind that wearing a body camera has become common practice within law

enforcement, it is important to also remember the flaws that Chen describes. The technical flaws

of the device, in combination with the embodied perspective it gives, makes it more complex

than regular CCTV or dash cameras. While other security recording devices still have flaws,

their static placement allows them to perform more objectively than the body camera. Because

the body camera remains a key part of discourse surrounding policing, it is imperative that we

grapple with the device’s complexities and find ways to approach the footage that it provides.

Through identifying the camera’s complexities and applying methods for viewing its footage, we

7

may be better able to understand body cam video. As discourse surrounding the body camera

becomes more common, we can question how to view both the images and the embodiment of

the body camera in a way that benefits our understanding of the scenarios that are captured by

body cameras. Through approaching footage by looking at the stances of passive/aggressive, we

can begin to answer these questions.

2 AGGRESSIVE/PASSIVE EMBODIED VIEWS

Before considering the semiotic and phenomenological concerns with the body camera, I

want to first discuss three separate cases involving the body camera, its footage, and public

reaction to/usage of footage in each separate case. The three objects of study used here are the

2021 Capitol riots, the 2019 home invasion of Ms. Anjanette Young in Chicago, and the

documentary film American Murder: The Family Next Door. The three differing uses of the

body camera in these cases offer a perspective of how the body camera’s embodiment functions

and how it may affect the viewer’s response to the footage which the body camera captures. This

analysis considers the cases in terms of their aggressive/passive views as well as the wearers’ use

of force in each instance. The footage from the Capitol riots and the Young home invasion are

both classified as aggressive, but the resulting footage differs in that the body camera is placed as

“victim” in the riot footage and as “perpetrator” in the home invasion footage. American

8

Murder’s footage is viewed as passive and thus has no victim/perpetrator assigned. Viewing the

footage from these three scenarios in these terms allows for a better understanding of just how

significant embodied movement and semiotic understanding of the body camera is.

While images captured by police body cameras typically take on the dominant

perspective, the body camera footage utilized in the 2021 impeachment trials following the

January 6 riots places the viewer in the shoes of the officers who were attacked on that day. The

footage analyzed here is from the officer who was beaten with a flagpole on the Capitol steps. In

this footage, shown during the impeachment trial, the officer is on the receiving end of

aggressive behavior. Because of the officer’s body placement, the body camera takes on the

embodied experience of being attacked rather than being the attacker. In the trial, this footage

was used as a means of emphasizing how aggressive the rioters were and how dangerous their

attack was on both the property and the people inside the building.

During the impeachment trial, film scholar David Bordwell wrote about the cinematic

nature of the trial and of the usage of body camera footage. He notes:

“The direct-cinema quality of the material is amped up by the presentation of body-

camera footage from an officer beaten down by the mob. The fallen-camera convention

of pseudo-documentary films wouldn’t be as powerful if we didn’t know that in violent

situations like this, cameras-and camera wielders-do drop. In this instance, the

approximate optical POV of the stomped officer makes his attackers seem even more

brutal.” (Bordwell, “Fast-Paced Trial”)

The officer’s shared point of view, via the embodied camera, allows for the viewer to feel the

force of the injuries that the officer suffers during the attack (note how the shared perspective

functions here versus when an officer is the body performing an attack). In the footage shared

9

with the court, the viewer sees the crowd attacking the officer from his perspective and can see

the number of weapons (flagpoles, pipes, etc.) used in the attack (fig. 1). Eric Swalwell, the

Democratic congressman who presented the footage, also includes the moment when the officer

falls down and attempts to get the rioters to back off. In this moment (fig. 2), the officer’s hands

appear briefly and extend away from the body camera; this extension of the officer’s hands and

arms makes the viewer identify more closely with the embodied perspective.

Figure 1

10

Figure 2

The decision to utilize body camera footage during this trial and to emphasize the officer’s

perspective during the attack is an interesting contrast to how body camera footage is typically

discussed. When we think of body camera footage, we make an assumption that the officer is in

the wrong and that the footage is being used to prove justification for an action. In this instance,

however, the body camera footage is used to show use of force against an officer and to

emphasize the fear that was felt on the day of the attacks. To achieve this, the use of body

camera footage here is meant to show a subjective, lived experience. This usage is different from

the ways in which we typically approach body camera footage, assuming the officer is the

perpetrator, and here we are encouraged to empathize with the officer as a victim of violence.

Though the impeachment trial ultimately ended in disappointment with former President Donald

Trump not convicted, the footage shown during the trial was widely discussed and demonstrated

11

the potential for the use of body camera footage in the courtroom (due to its cinematic potential,

as Bordwell stated).

An alternate example of aggressive embodiment, and the more common occurrence

associated with the police body camera, is the act of forced entry onto private property by an

officer. The forced entry considered here is the home invasion of Anjanette Young in Chicago.

Anjanette Young’s home was wrongly raided by a Chicago police team in February 2019. When

Ms. Young called for the body camera footage to be released, the city went to federal court in

attempt to block release of the footage. When the video was eventually released, Ms. Young

brought the footage to the news in hopes of seeking justice and shedding light on the apparent

issues within Chicago Police Department. She told the local CBS station: “I feel like they didn’t

want us to have this video because they knew how bad it was […] They knew they had done

something wrong. They knew that the way they treated me was not right” (CBS News).

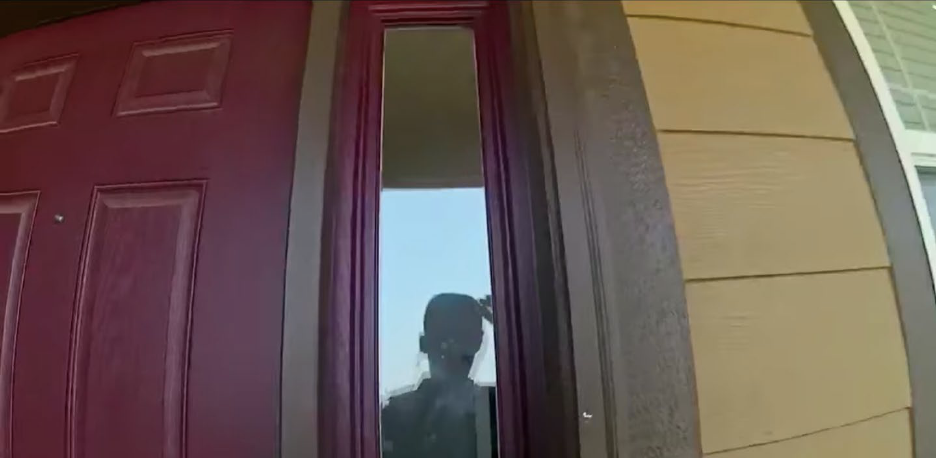

In the released footage, the viewer witnesses an all-male raid team breaking into Ms.

Young’s home and catching her unaware. The twelve-minute video, composed of images from

nine body cameras, follows the officers approaching the complex, breaking down the front door,

and immediately handcuffing Ms. Young in the living area and continuously ignoring her pleas

that they have the wrong house. The footage alternates between the nine body cameras’ points of

view. Due to the multiple perspectives captured by the various cameras at the scene, there is a

noticeable difference between officers’ reactions to what is taking place. Two officers remain

near Ms. Young throughout the video, one handcuffing her and the other speaking with her, and

the other officers who initially entered the property move away from the living area and

reconvene outside the front door. Through the camera’s embodied view, the viewer can sense

that there is something inherently off about the situation due to the officers’ uncertain body

12

movement and consistent shifting. The body cameras capture officers looking at one another

with uncertainty and show them either turning away from Ms. Young or leaving the scene

altogether (fig. 3).

Figure 3

Through the changing embodied perspectives, the viewer moves throughout Ms. Young’s home

and watches as different officers mull around in each room, picking up random items, shuffling

objects around, and taking photos in order to make it look like they are in the correct location for

their investigation. If an energy can be used to describe the movement throughout the entire

video, then “restless” would perhaps be the best descriptor.

If the body camera is employed in order to provide justification for officers’ actions, then

this case is interesting in both the footage that we see and in the department’s initial refusal to

release the footage to Ms. Young—they even attempted to prevent the news from playing the

video on air shortly before Ms. Young’s interview went live. The footage here is damning, and

the embodied perspectives that we see make it clear that the officers at the scene knew that they

13

had made a mistake. The footage shows this as well as the incompetence and disrespect that the

officers displayed on the job. As Ms. Young stated, the department knew that this footage, if

released, would be bad for their publicity, and therefore attempted to hide it. This attempt makes

the claim that the body camera is there to protect seem like a lie—while there were several body

cameras on the scene, the officers’ actions were still deplorable, and the powers that be tried to

hide the footage, so how beneficial was the body camera to Ms. Young? While the footage, once

released, became useful to her for sharing her story, the presence of the cameras did nothing at

the time and in the moment in order to protect her from police harm.

Figure 4

14

Figure 5

Ultimately, the news investigation—and Ms. Young’s attorney—found that the officers

never obtained a proper search warrant for Ms. Young’s home and never confirmed the proper

address, getting their information solely from an unnamed informant. Redacted footage that was

eventually released along with the original video shows that Ms. Young was never given any

form of warrant at the time of the search and that the officers entered the property quickly and

without warning. The police department would not comment on this footage, and as of June

2021, Ms. Young and her legal team are still attempting to receive proper settlement for the

police department’s wrongdoing. Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot formerly promised Ms. Young

that she would be compensated for her suffering but has since stepped back from that promise.

Ms. Young’s decision to obtain the body camera footage and release it to the public

herself raises interesting questions about how useful the body camera is if its footage is never

intended to be shared with the public. How does this provide any accountability? If the footage

of this case had not been released, and it seems as though the footage would likely never have

been made public without Ms. Young’s intervention, then there would not have been public

15

awareness and cause for the officers’ actions to be investigated. Here the common protest sign

sentiment “how many aren’t filmed?” rings true. The released footage of this injustice begs the

question: How many unauthorized and/or incorrect home raids have occurred in this police

department and how few of them is the public aware of?

And, as will be discussed in the third chapter, the embodied perspective of the officers

presents a complicated dilemma; while we the viewers see that the actions taken by the police

force in this case are wrong and immoral, the camera becomes complicit in the actions, forcing

the viewer to (physically) take the side of the officer and attempt to see the events unfold through

the “actor” that wears the camera. The tie between the viewer and the wearer, made possible by

the body camera, complicates our ability to objectively view these images. We know the actions

are wrong, but we share space with the perpetrator. How does this shift our understanding of and

reaction to this footage?

The final case examined here is the body camera footage found in the Netflix

documentary American Murder: The Family Next Door. Unlike the previous two cases, the body

camera used throughout this film can be considered passive; there is no forced entry or violence

shown, and the officers who wear the body cameras interact peacefully with their suspects.

American Murder is a close examination of the events leading up to and following the murder of

the pregnant Shanann Watts and her two daughters, Bella and Celeste. The documentary uses a

combination of social media posts, police footage, news footage, personal videos, and text

messages/calls from Shannan’s friends and family in order to tell its narrative. Similar to the

footage released in Anjanette Young’s case, the viewer has access to multiple embodied

perspectives via different officers’ cameras. However, the difference in terms of

passive/aggressive behavior is immediately apparent.

16

In the former scenarios, the usage of body camera footage makes sense in trying to seek

justice for two differing acts of unjust violence. How does body camera footage function in a

documentary about a white woman’s murder which has already occurred? Before the

documentary was released, Shanann’s case had been major headlining news across the country.

The public became fascinated with Shanann’s story because the murderer in this case was not a

stranger, but rather her husband, Chris Watts, whose bizarre news appearances led investigators

to suspect his involvement in Shanann, Bella, and Celeste’s disappearance. In addition to the

horrific circumstances of her murder, Shanann’s social media presence before her death also

played a key part in public interest in her murder. Shanann’s popular Facebook video posts about

and photos of her ‘perfect’ marriage and family life became especially haunting in the aftermath

of her death.

Because of the popularity of the Watts case and interest in Shanann’s marriage, many

details of the Watts murder were already well-known by many, it is possible that the film’s

creators decided to use body camera footage as a means of presenting a “never before seen” view

of the events surrounding the aftermath of Shanann’s murder. The inclusion of body camera

footage here provides viewers with a firsthand view of the day Shanann disappeared and the

ability to “witness” Chris Watts’ suspicious behavior, giving viewers an opportunity to

“participate” in the investigative work leading up to his arrest. The use of body camera footage

begins when an officer is called to the Watts house for a welfare check after a friend has reported

Shanann as missing. Through the body camera’s image, the viewer follows along as the officer

and Shanann’s friend search the exterior of the house and wait for Chris to arrive. Throughout

this sequence, an interesting sense of “otherness” occurs when the officer begins to look into the

windows of the Watts home; the camera captures the reflection of the officer in the window, and

17

then as his body moves closer to take a look inside, the camera also shifts focus and is able to

peer into the house, offering viewers a look inside of the empty house (fig. 6 and 7). While the

camera is tied to the officer, this provides a brief moment of broken identification. Not only are

we, the documentary viewers, spying on this home, we are also gazing at the person who is

controlling our movement within this space.

Figure 6

18

Figure 7

As time passes, Chris eventually arrives at the home and provides consent for the officer

to enter the premises (a direct contrast to the forced entry into Anjanette Young’s home). Again,

the camera operates as an objective observer, moving with the officer’s body as he searches the

house. While the officer moves quickly through each room, the camera’s view lingers a bit

longer, likely due to a delay, and the viewer gets sufficient overviews of each room, allowing

them to cast their gaze on the scene and “investigate” alongside the officer.

The Watts’ next-door neighbor calls Chris and the officer over to his house, where he

displays footage from his security camera system. His camera happened to be facing the Watts’

driveway and captured footage of Chris Watts’ truck backing into the garage earlier that morning.

The scene is curious in that as the officer and Chris take in this footage, the body camera is also

recording the neighbor’s surveillance video as it plays on the television. Here, two different types

of surveillance (the body camera and home security) are on full display to the documentary viewer.

19

After this conversation, two more officers arrive at the Watts house and with their arrival,

the documentary audience gains two new perspectives via their body cameras. Now the viewers

separate from the initial officer’s movements and his camera’s perspective, and footage jumps

between the three officers’ positions as they converse with Chris (figures 8-10).

Figure 8

Figure 9

20

Figure 10

As the conversation in this scene continues on, uninterrupted, the cameras on the officers’ bodies

watch silently and provide different perspectives of the same “scene” to the documentary viewer.

The officers form around Chris in a three-point structure, but there is no sense of aggression or

tension which was felt in the Capitol or Young cases.

Through the use of body camera footage in this sequence, the documentary audience is

able to more fully immerse themselves within the investigative work that the film is asking them

to do. While some viewers may already be aware of the circumstances behind Shanann’s

disappearance/death, the embodied view provided by the body camera(s) allows them to more

fully immerse themselves into the film’s investigative work. While the documentary format

already asks the viewer to actively participate and question what they see within the film’s

narrative and structure, American Murder takes that participation further through these devices.

Rather than providing the audience with definitive answers and directly pointing their attention

towards images and other objects, the film, through the use of the body camera, places the

21

audience within the events taking place, forcing the viewer to actively tie together the

information that they have been provided with the events that they are witnessing take place. As

the film continues, and as more body camera footage is seen, the audience begins to formulate

their own opinions about Chris Watts’ role in the death of his wife. It becomes clear, through the

combination of images and events that the viewer sees/witnesses, that the person who is

responsible for Shanann and her daughters’ disappearance is definitively her husband.

While the beneficial uses of the body camera are evident in American Murder, where the

audience is easily able to formulate their own opinions about Shanann’s case through the body

camera’s footage, it is important to see the difference in how body camera wearers interact with

white suspects versus suspects of color. The glaring difference between the three-point structure

which surrounds Chris Watts—a murderer—and the structure which surrounded Anjanette

Young—and innocent person—is made clear through the contrasting images that the officers’

body cameras provide. Would a police department release body camera footage to be used in a

purely objective way—as seen in this film—if the narrative were about a black person? About

police brutality? It is likely that the answer is no (seen by the refusal to release footage to Ms.

Young). This aspect of the body camera, when thinking about its potential for use in

documentary, must also be acknowledged.

After looking at these three uses of the body camera, viewers must approach the body

camera and its gaze with the same level of consciousness that they approach every other element

of media with—what is their knowledge about this device? What are the implications of the body

camera? What are the ontological signs placed on this piece of technology? If the viewer is

American, then there will likely be a significant amount of pondering the device’s status in the

film—further complicating the viewer’s ethical and moral participation in viewing the footage.

22

Through this analysis of various cases of the body camera being positioned as passive or

aggressive, and how the different embodied views function as a “body of proof” for different

reasons, it is hopefully clear to see that the body camera’s embodied perspective is more

complex than just working as an objective third eye. In providing the viewer with a clear

embodied view of events taking place, the body camera’s footage/gaze allows the viewer to

watch persons and events through the camera’s view in combination with their own embodied

experience/knowledge of the world. Through this “shared” experience, the act of viewing body

camera footage becomes complex and brings up questions of how the images function in

conjunction with embodied experience. The following chapters aim to address these

complications in combination with further analysis of these three cases.

23

3 A SEMIOTIC APPROACH

As seen by these examples, while the body camera is meant to serve as a piece of

observational, objective technology, it is inherently tied to the body which wears it, complicating

its intended neutral gaze and forcing a shared connection with the person who wears it. Thinking

of the images the camera captures, how can we approach body camera footage in terms of its

semiotic importance? What is the index that the body camera captures, and how does that index

evolve into meaning? How do alternate sources of footage—such as a bystander’s cell phone

camera—complicate and transform the evidentiary image that the body camera captures? To

approach these questions of complication, this chapter will be turning to foundational writings on

semiotics as well as pieces which focus on how the index becomes complicated in various

circumstances. Through further analysis of the first chapter’s three cases of body camera footage,

the chapter utilizes semiotic approaches to understand how the footage seen in these separate

cases becomes complicated both through the embodied view of the camera as well as through

complications from outside sources (news, alternate footage, etc). Through a study of the

indexical and the social/political contexts in which we understand the body camera, this

chapter’s goal is to demonstrate how the embodiment of the body camera rejects the claim that it

is an observatory device.

Keeping these issues in mind, it is important to consider what role indexicality plays in

the body camera’s image and its place within public discourse. Indexicality and semiotics have

long been at the forefront of film and media studies, studied alongside the camera and the images

it captures. Appropriately, most discussions of the index and other forms of semiotics always

refer back to the work of Charles Sanders Peirce, whose writings on index, icon, and symbol

have become the standard for semiotic study. Of these three, the index is the most heavily

24

studied in its relation to photography, film, and the moving image camera. While the index is

typically taught through the simplistic concept of “the footprint in the sand,” many scholars have

complicated our understanding of just what the index is and how it evolves into meaning.

Moving beyond Peirce’s definition of the index is crucial to understanding how an image—

especially one captured by a controversial piece of technology—may not ever be truly

observational and objective. While Peirce’s definition of the index is the inherent tie between an

image and its referent, it is clear that there are many factors which can taint or shift what the

index represents. In the case of the body camera, the police officer’s body, as a referent,

embodies a very different existence within a particular time and place versus that of someone

else’s. The officer’s status in society complicates their indexical status and, in combination with

the framing of the image, the image which their body camera produces.

Mary Ann Doane has discussed the complicated nature of Peirce’s index in this context:

she questions the idea (circulating in contemporary conversations about the “digital turn”) that

the technological changes involved in digital imagery have somehow caused a change in the way

the index functions. She argues that, while “the digital offers an ease of manipulation and

distance from any referential grounding that seem to threaten the immediacy and certainty of

referentiality we have come to associate with photography,” these qualities of digital images

merely exacerbate an effect that is true of pre-digital, photochemical cinema and photography as

well (Doane, “Introduction,” 1). The relation between image and referent in photography and

cinema has always been contingent, unstable, and uncertain. She explains that the image and

referent can become removed from one another, complicating the image. While acknowledging

that this concept can be confusing, Doane reiterates Peirce’s argument that “the index is defined

by a physical, material connection to its object” (2). The index, regardless of the form it takes,

25

relates a referent to its (former) reality and spatiotemporality. Though she will go on to further

define and discuss the index as deixis in terms of how it is framed within the cinematic, Doane

here notes that “the index as deixis implies an emptiness, a hollowness that can only be filled in

specific, contingent, always mutating situations. It is this dialectic of the empty and the full that

lends the index an eeriness and uncanniness not associated with the realms of the icon or

symbol” (2).

Doane, drawing on work by Rosalind Krauss, also questions the relation of realism to the

index, noting that the index can never concretely represent the real, it can only reference the real.

This distinction between representing and referring to the real is key to the idea of the

“hollowness” which Doane describes. Because the index is easily malleable, it can never be

claimed as a direct representation of reality. It can seek to show what reality might have been,

but never claim full factuality. It merely points to possibilities. Doane makes sure to clarify,

however, that this intricacy between real/not real should not detract scholars from approaching

the index’s complexities, rather, they should use the index’s complexities as a means of studying

its impact.

Doane further discusses Peirce’s differentiating types of the index and how they might be

used together within the cinema as a means of placing meaning onto an image. These two types

of index are index as trace and index as deixis. Doane notes that “mainstream fiction and

documentary film are anchored by the indexical image and both exploit, in different ways, the

idea of the image as imprint or trace, hence sustaining a privileged relation to the referent”

(Doane, “Concept of Medium Specificity,” 132). The typical exploitation of the “real” that the

index relates to is what bothers Doane. As she stated earlier, the index is not a replica of the real,

it is merely a reference to it, and the use of the indexical as a claim of realism is unethical. When

26

pointing to the index, it must be emphasized that the image is not the real thing, but rather proof

of its existence in the past (which is now being viewed in the present).

This is further exemplified through both index as trace and as deixis. Index as trace

“implies a material connection between sign and object as well as an insistent temporality—the

reproducibility of a past moment” (136). This is the most recognizable form of the index; index

as proof of something/someone that once was, in the past. The image we see produced from a

camera (either still or moving image) asserts that something existed in a particular moment in the

historical past, allowing for it to be captured in the image. The trace is the assertion of an

object’s existence in the past, its anteriority. The index as deixis is more complex in that it is

linked to the present—we are viewing “this” image of the past “here” in the present. While the

trace is more commonly linked to and discussed within the confines of the cinematic, Doane

notes that the deixis is equally important and that, for Peirce, the two go hand-in-hand. The

deixis “can only achieve its referent, in relation to a specific and unique situation of discourse,

the here and now of speech” (136). Through the framing of the index, the deixis emphasizes the

importance of discourse and viewing of a trace. Used together, “the dialectic of the trace (the

‘once’ or pastness) and deixis (the now or presence) produces the conviction of the index” (140).

The acknowledgment of a referent’s existence in the past alongside the awareness of our ability

to view the person/event in the present is key to our understanding of its evidentiality.

Can this “emptiness” be perpetuated through the digital image? Doane argues yes. When

an image is digitized, the index loses its existential bond with the object, and now can move

throughout space and time, detached from its referent. “Both the intimacy of [the] relation to a

unique and contingent reality and the detachability and circulation of its representation have had

enormous cultural consequences” (3). This detachment is certainly applicable to the body camera

27

and the images it captures. Body camera imagery, through the referent’s capture via other camera

apparatuses (or rather, different viewpoints of a referent captured by varying image sources),

suffers a gap between the referent and the image. Thus, it relies on societal context and discourse

to have meaning.

Again, as Doane argued, the index can seek to show what reality might have been but can

never claim full factuality. This uncertainty of realism applies to the digital image’s detachment

and is displayed in body camera footage: the body camera’s capture of an incident can only

reflect what reality may have looked/felt like for the persons involved, its image is not direct

evidence of what really happened in reality. Because of its digital aspects (for example, any

glitches, time lag, poor lighting, etc.), the camera’s image cannot be viewed as direct

representation of the real. These complications, along with discussion of the index as trace and

index as deixis, are of considerable importance to answering the question of the body camera’s

indexical image and how it shifts in meaning over time. We can acknowledge that the trace of

the body camera’s image is the officer’s (and others’ captured in the image) body—proof of their

presence in a particular time and place in the past (this time and place given to us via the time

stamp included in the camera’s image). What is the deixis, or the way we view the footage “here

and now,” that transforms the body camera’s images? How does this frame shift our perceptions

of the images we see as captured by the body camera?

The framing of the body camera’s image is a bit more complex than the standard

photograph or video’s, in part because of the way the camera’s image is released to the public.

Typically, police departments will only release body camera footage when necessary or when

requested. Because of this timing, while the body camera is intended to serve as objective proof,

by the time the public views its footage, the images and referents attached to it have already

28

become laden with meaning, tainting the objectivity of the images. The persons and events

captured through the body camera come into meaning and into public discourse mostly through

outside sources. Most recent cases of police brutality have been captured on (digital) film

through a bystander’s cell phone camera, which has the ability to automatically upload its

footage to social media. Because these cell phone videos spread an image so quickly and because

the body camera footage takes a significant amount of time to be shared with the public, public

opinion has already turned against the officers’ actions, making it impossible for the body

camera footage to be seen purely at face value when it is finally viewed.

Because viral sharing of footage and alternate video sources affects our approach to the

images that the body camera captures, it is worth asking why these videos of police brutality

spread so quickly. In her “Toward a Phenomenology of Nonfictional Film” essay, Vivian

Sobchack notes how some images can become “fetish objects,” obsessively viewed even if the

content is disturbing. This fetishization of the horrific can be seen in the viral sharing of footage

online, especially videos/images of wrongful deaths. In the case of George Floyd, the footage of

his death spread rapidly throughout social media and almost immediately became a fetish object,

as his image became the symbol of much-needed change in the justice system. Because these

videos capture proof of wrongdoing, a larger portion of the public who typically may look away

from injustice are now forced to see documented proof of police misconduct. The video causes

viewers to actively interact with the emotions that they feel when watching. Thinking of viewers’

response to videos in this way, the subsequent outpourings of (performative) support and

activism can perhaps be seen as a form of absolution for complicity in institutional racism or for

watching the video repeatedly.

29

In cases where alternate footage is made known to the public, the body camera footage of

an event must work against public understanding/belief of what took place. Released only after

public outcry and unrest, the body camera footage of George Floyd is forever tainted. George

Floyd—whose face became a symbol for Black Lives Matter and proof of injustice—appearing

in this footage, alive and talking with the officers, is haunting. It serves as the trace that he was

alive, but the deixis reminds the viewer of the circumstances surrounding his death. While in this

footage, the viewer sees the officers’ perspective as the events take place, the viewer cannot

unsee the image that they’ve already seen of Floyd’s death. With that image preceding the

release of body camera footage, the recording does not serve as an objective point of view but

rather just as a reminder of the horrific incident which occurred, and the shared perspective with

the offending officers (a view which we can label as aggressive/perpetrator) adds an additional

layer of disgust.

The way the footage of George Floyd gained traction across different forms of media and

came into meaning reflects the writing of Frank P. Tomasulo, who writes that “history is defined

as the discourse around events, rather than those original events that prompted the discourse in

the first place” (Tomasulo 69). Tomasulo considers this argument through looking at the case of

Rodney King, which first introduced the potential of videographic evidence in the discussion of

police brutality. With the claim that history and understanding of a historic moment is heavily

influenced by the discourse surrounding that moment, it is also important to note that there can

be many differing viewpoints of what constitutes truth and factuality; if many people view an

image, there are multiple views of what the “truth” of that image is dependent upon the lived

experiences/personal beliefs of each person. This multiplicity of views is only exacerbated by

media and the digital. “…our concepts of historical referentiality (what happened), epistemology

30

(how we know it happened), and historical memory (how we interpret it and what it means to us)

are now determined by media imagery” (70). Through the media’s presentation and through

public interpretation, an image does not simply serve as proof of evidence, but rather serves as a

beginning point for discourse. And through this discourse, the image gains its iconic/symbolic

place within a historical moment.

Analyzing the Rodney King videotape captured by George Holliday, Tomasulo notes that

Holliday’s “noninterventionist, seemingly straightforward and objective mode of production

allowed the videotape to be used as a national Rorschach test of sorts, whereby each citizen

reacted to the scene according to his/her own subjectivity and experience (often based on gender,

class, and race)” (75). In addition to each viewer approaching the video through their own

perspective (mediated through their experience of being-in-the-world), the footage as it was

shown on television was often accompanied by a “story” as told by news anchors, experts, etc.

Through the combination of personal opinion and public discourse surrounding the tape, the

public inevitably formed a cohesive understanding of the narrative attached to the video. Despite

the defense attorneys’ efforts to present the evidence in a different way, in fact urging jurors to

see the events from the officers’ perspective, the video only served as visual proof of

unnecessary use of force and institutional racism—the public’s interpretation of the video. If

citizens react to video evidence of a scene with their own subjectivity and lived experience, how

does that become complicated when viewing footage which has been captured by the body

camera? We may approach the footage with a determination to remain objective and to view it

from our own subjective experience, but the camera’s attachment to the officer’s body makes it

more complicated than that. As will be discussed in the third chapter, when watching movement,

especially embodied movement, we succumb to “double-identification,” and must remain aware

31

of the fact that we are experiencing intersubjectivity while watching any type of embodied

movement, but especially so when watching footage captured from a camera attached to a human

form.

Tomasulo also points out that “human beings rarely enter a situation, historical or

otherwise, with a fresh, untainted perspective” (82). Our approach to body camera footage is no

different. Due to the nature of its footage and the timing of its release, the body camera and the

images it captures can almost never be viewed with a fresh perspective. Even if alternate footage

is not released before the body camera footage, people will apply their already-formulated

opinions on the image through their own lived experiences with police, racism, etc. The image is

tainted before it is ever viewed, making it impossible to claim that the body camera is an

objective device. While it may aim to be objective, its footage will never be viewed as such.

Through viewing the ways in which indexicality functions within the body camera and

the images it captures, as well as the ways in which images of police brutality travel through

social media, it is clear to see that the body camera is a problematic device. As will be discussed

in the following chapter, the body camera is complicated through its embodied view and the

varying ways in which we, the viewers, identify with and respond to the footage that we see. The

“work” that is done in order to judge what is seen on tape is affected by this shared embodiment

but also by the significations that I have just discussed. Understanding that there is a level of

fetishization of the grotesque alongside public discourse and opinions is crucial to approaching

released footage. As seen in the examples of the Capitol riots, Anjanette Young, and American

Murder, body camera footage is more often than not viewed alongside some type of commentary

or additional contexts; the Capitol footage was accompanied by Eric Swalwell’s narration, the

footage of Anjanette Young’s home accompanied by an interview with Ms. Young and narration

32

from news reporters, and the body camera footage seen throughout American Murder is

interwoven with texts and captions. In each case, we not only witness the footage, but we also

approach the footage with additional contextual knowledge that is given to us. When body

camera footage is released to the public, it is entering a landscape which is already laden with

opinions and moral perspectives that may influence how its images are received. This, in

combination with the complexities of its embodiment, make the camera more complicated than

merely acting as a surveillance device.

Here, I also want to briefly consider the concept of “double-identification” as discussed

by Jean Baudry in relation to Lacan’s theorization of the mirror phase. In his “Ideological

Effects” essay, Baudry writes about the double-identification that takes place when one is

watching a film onscreen. Using the mirror phase as reference, Baudry describes the two forms

of identification which take place while watching something transpire onscreen: identification

with the image itself which “derives from the character portrayed as a center of secondary

identifications, carrying an identity which constantly must be seized and reestablished” and

identification of the objects which “permits the appearance of the first [identification] and places

it ‘in action’—this is the transcendental subject whose place is taken by the camera which

constitutes and rules the ‘objects’ in this world” (Baudry 540). While these two levels of

identification are being used by Baudry to describe the identification which takes place while

watching a film, they can be additionally attributed to any type of media which allows for a

viewer to observe and witness actions and bodies on a screen. I find Baudry’s discussion of these

levels pertinent largely because of this additional note:

“[…] the spectator identifies less with what is represented, the spectacle itself, than with

what stages the spectacle, makes it seen, obliging him to see what it sees; this is exactly

33

the function taken over by the camera as a sort of relay. Just as the mirror assembles the

fragmented body in a sort of imaginary integration of the self, the transcendental self

unites the discontinuous fragments of phenomena, of lived experience, into unifying

meaning.” (540)

Again, though Baudry’s analysis is aimed at the motion picture, his commentary of how

and with what the viewer identifies is relevant to the following chapter’s discussion of how the

body camera’s embodied view shapes the observer’s perspective. If—considering Baudry’s

comments here—even just the presence and acknowledgement of a camera in a space, aimed at

moving subjects, forces the spectator to more strongly identify with the camera’s perspective

rather than the subjects captured in its images, then how does the embodied camera affect viewer

identification? The following chapter explores this question further, but it is interesting to note

the underlying psychoanalytic semiotic theory that can be utilized when looking at body camera

footage and how viewers respond to what they see unfold.

34

4 PHENOMENOLOGY, EMBODIMENT & THE BODY CAMERA

In the first chapter’s analysis of the three instances of body camera usage, I noted the

various embodied perspectives that the body camera takes as well as how those perspectives

were meant to alter the viewer’s understanding of the corresponding events and their contexts. In

looking at the examples of the Capitol riots, Anjanette Young’s home raid, and the documentary,

we can see that the embodied perspective of the body camera is something that cannot be

detached from the image. Because the embodied view is so attached to the device, it is important

to consider how we may approach the body camera phenomenologically. This chapter aims to

further explore how embodiment affects the viewer’s understanding of footage captured by a

body camera as well as how the embodied perspective can be considered within a

phenomenological study.

Before delving further into the value of applying the phenomenological method to

analysis of body camera footage, it may be useful to answer the previous chapter’s question

regarding who viewers identify with when watching footage from an embodied perspective. A

2018 study completed by researchers interested in the judgment of body camera footage

overwhelmingly showed that “observers of body cam footage may be more likely to engage in a

process of perspective taking […] and, thus, adopt the motivational stance of the actor in

question” and, through this perspective taking, avoid negative blame in courtroom cases (Turner

1202). The researchers compared observer reactions to body cam footage versus dash cam

footage and found that the embodied view of the body camera creates psychological attachments

with the “actor,” or person wearing the camera, which may create a sense of empathy for the

perpetrator of violence. While the viewer has access to context and more information aside from

the footage that they see, the embodied perspective that the body camera provides makes it more

35

difficult to observe the images onscreen in an objective manner. The researchers note that “when

police videos depict negative outcomes, the motivation of the wearer may be to avoid blame”

(1202). In seeking to avoid blame, the observer may overlook cases of abuse or attempt to justify

an action. This complicates the “objectivity” of the body camera’s footage. If a jury is presented

with body camera footage in court, who will they side with? The perpetrator or the victim? If

thinking of the footage used in the Capitol riot, it is easy to empathize with the officer who wears

the camera, which was used effectively. If the footage from Ms. Young’s case were shown,

however, how might a jury respond? While easy to notice wrongdoing, the embodied perspective

still forces a connection between the wearer and the viewer. The study postulates, and I agree

with this claim, that the identification with the wearer is due to the movement that the observer

mimics while viewing the footage. The study defines this as “dynamic imagery” and notes that

“static information about an actor’s identity [e.g., a face] matters less in this context than does

dynamic imagery [e.g., the movement of the actor’s arms], because the latter conveys additional

information about how the incident unfolds in real time, including subtle cues as to the actor’s

mental state” (1203).

We see this in the three examples discussed in the first chapter, especially in the

Anjanette Young footage, where the various embodied views indicate the discomfort and

nervousness that the offending officers feel as they realize that they’ve gotten their information

wrong. While it is infuriating to see their treatment of Ms. Young, it is also difficult to fully

separate identification with the body that the camera is attached to. This identification

complicates our relationship with and judgment of the footage, and this study provides evidence

of the fact that due to the embodied nature of the footage, the viewer is unable to completely

observe what they see taking place onscreen in an objective manner.

36

The question of identification is important to our understanding of how to view body

camera footage, so it is essential to consider the different forms of identification which occur in

cinematic movement. Though body camera footage is not definitively a documentary or fiction

film, it does function as a form of the cinematic, so it makes sense to apply these theories to the

footage which we’ve discussed here. Sobchack considers this in her own writing, and in her

discussion of the complexities that are attached to modern technologies, she writes:

“[…] technology never comes to its particular material specificity and function in a

neutral context to neutral effect. Rather, it is historically informed not only by its

materiality but also by its political, economic, and social context, and thus it both co-

constitutes and expresses not merely technological value but always also cultural values.

Correlatively, technology is never merely used, never simply instrumental. It is always

also incorporated and lived by the human beings who create and engage it within a

structure of meanings and metaphors in which subject-object relations are not only

cooperative and co-constitutive but are also dynamic and reversible.” (Sobchack 137)

This assertion is relevant to modern technologies such as the cell phone or computer which are

handled by human hands, but if we apply this thinking to the body camera, it is clear that the

camera—even if it were not attached to a body—would still be laden with the subjectivity that

comes from the lived experience of the person who handles the device (which relates back to the

questions surrounding the camera’s indexical images). Though the body camera is not “handled”

by an operator, it is still influenced by the “actor,” whose bodily movement shapes the viewer’s

understanding of the images they see.

Since Sobchack recurrently refers to Meunier’s writing and because identification is such

a large aspect of approaching body camera footage, it seems pertinent to look at Meunier’s

37

writing on identification directly, especially his definition of identification and the different

forms of movement/identification that he sees within moving images. Meunier describes

identification as follows:

“a behavior of private intersubjectivity, […] a question of the comportment rooted in the

terrain of anonymous intersubjectivity – a sort of generic coexistence of subjectivities –

but subsequently structuring itself in a personal relationship, that is, in the behavior of

private intersubjectivity.” (Meunier 118)

This concept of intersubjectivity fits well with the body camera and the dilemma we face as

viewers of its footage—we attempt to view the footage objectively as outside observers, but we

become tied to the actor’s body, forcing shared subjectivity with the person who wears the

device. Meunier also notes:

“In its participatory form, as in all its other forms, identification is in fact motoric and

mimetic in nature. And yet, mimicry, we can recall, consists of a postural or psycho-

muscular attitude that aims to reproduce the behavior of the other person in order to

understand it. What the spectator possesses at the end of the film is, therefore, not a

conceptual knowledge situated on the level of rational thought, but a knowledge that is

somehow ‘bodily’ in nature. In figurative terms, we can say that the spectator remains

impregnated by the other person – possessing, that is, in the form of motoric or bodily

traces, the behavior of the other person.” (145)

Though Meunier writes this in relation to how spectators respond to fiction or nonfiction films,

we can see—in the research done on observers’ reactions to body cam video—that

“impregnation” is relevant to the body camera. The adoption of physical movement creates a

psychological tie to the actor rather than to the events that the actor witnesses. Because the body

38

camera is not placed at eye-level, while we do see events take place from the officer’s

perspective, we more so witness the body’s behaviors and responses within different situations.

In the examples used in the first chapter, we receive the “bodily” knowledge of what it looks like

to be a victim of undue violence (Capitol riots), to be the perpetrator of aggressive invasion

(Anjanette Young), and to be a passive observer in a home (American Murder). While the

footage from these cases aims to show observers the contexts of each event, what we take away

after viewing the footage from each case is the embodied subjectivity of the actors. And, as in

the above research, we feel fear, guilt, and calm, respectively, in each case.

In that the body camera in the above cases was used a means of documentary, or proof of

an event taking place, it is clear that body camera footage will be received within a nonfictional,

evidentiary context, regardless of the forum in which it is used (documentary film, news,

courtroom). Since the body camera and its footage is inherently linked to the documentary

genre—and its main traits—I believe it necessary to consider how phenomenology and embodied

subjectivity functions within the nonfiction genre and how it affects the traditional role of the

viewer within documentary. Sobchack has written frequently on the ties between

phenomenology and documentary, with a particular focus on the role of audience perception in

documentary films. In her “Toward a Phenomenology of Nonfictional Film Experience” essay,

Sobchack writes on the different emotional responses that viewers experience watching certain

films, noting that for some, a documentary or home movie may be experienced more as a fiction

film, or vice versa. This conversation on the embodied experience of a viewer and how they may

emotionally react to viewing certain footage is important in the conversation of how the body

camera may shift how viewers respond to particular footage. Sobchack refers to Meunier and

notes that when we watch a documentary, we are “looking both at and through the screen,

39

dependent upon it for knowledge” (246). In the documentary genre, the viewer must take on an

active role in identifying important information that pertains to the story that is being told. While

the film aims to present this information to the spectator, it is ultimately an act of work which

leads the viewer to understanding the purpose and meaning of different images and narratives

provided to them. Sobchack refers to Meunier again to emphasize the importance of engagement

within documentary films:

“For Meunier, the intentional objective of documentary consciousness is comprehension,

not evocation. In the documentary experience, the spectator engages in a mode that

Meunier calls ‘apprenticeship’ to the film object. That is, identification in the

documentary experience involves a process of learning that occurs contemporaneously

with viewing the film.” (249)

Sobchack and Meunier define two differing forms of comprehension/consciousness that happen

within the documentary: longitudinal and lateral consciousness. The viewer’s longitudinal

consciousness is their awareness of how all the different pieces of a documentary will come

together to form a coherent narrative, that there are parts to a whole. Lateral consciousness is the

understanding that “past images are accumulated and inform present meanings that intentionally

direct consciousness toward the revelation and significance of future outcomes” (250). Or more

simply, the documentary viewer is aware of how these elements of the past (evidence, footage,

images, narration, etc.) are all in combination in the present, through the film, in order to display

a narrative. As these pieces fit together, “lateral consciousness is thus structured as a temporal

progression that usually entails causal logic as well as teleological movement” (250). The viewer

works alongside the documents/filmmaker/editor in order to make meaning of what they see.

40

Sobchack also notes that viewer’s bodily and perspectival difference from the

events/persons onscreen are affected by the investigative work he or she must perform. She

writes that “our relation to the filmed person or event remains a relation of otherness and

exteriority” and that “the labor involved in the cumulative comprehension of the person in

general or the event in general creates a distance between [the viewer] and the image of the

person or event” (251). This separation between the viewer and the person/event reaffirms

Baudry and Meunier’s arguments on double identification, again showing that the viewer, even if

viewing non-embodied images, places themselves at a distance from the person(s) they see

onscreen. With a normal, static camera, the viewer recognizes this distance and can utilize an

observatory view and interact with what they see as a means of forming the longitudinal and

lateral consciousness which Meunier described. Sobchack ends the essay stating that “a

phenomenological model of cinematic identification restores the ‘charge of the real’ to the film

experience. It affirms what we know in experience: that not all images are taken up as imaginary

or phantasmatic and that the spectator is an active agent in constituting what counts as memory,

fiction, or document” (253). This affirmation of the documentary spectator as active agent is

particularly useful to considering how the body camera can be used within documentary, as it

literally provides embodied, teleological movement and positions the spectator as active agent,

allowing for them to view events/persons in more detail than a regular camera can provide.

Sobchack further applies phenomenology to documentary film in her book, Carnal

Thoughts. Throughout her different pieces on documentary, Sobchack consistently notes the role

of ethics within the nonfictional genre. In discussing the portrayal of death in documentary films,

Sobchack writes that there exist “highly charged ethical stances that existentially (but always

also culturally and historically) ground certain codes of documentary vision in its spectacular

41

engagement with death and dying—also, so visibly charged, also charge the film spectator with

ethical responsibility for her or his own acts of viewing.” (Sobchack, “Carnal Thoughts,” 227).

This charge is apparent in the aforementioned study in that viewers of body camera footage may

attempt to “avoid blame” when viewing violent scenarios. In documentary film, because the

viewer takes on such an active role within the consumption of the film, their ethical/moral

responses to what they see onscreen become complicated, especially when viewing death or

abuse. This ethical dilemma becomes further complicated when viewing body camera footage as

a document or as proof of an event which took place. The viewer becomes, through the