The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

TACTICS AND TECHNIQUES OF THE NATIONAL WOMAN’S

PARTY SUFFRAGE CAMPAIGN

Introduction

Founded in 1913 as the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), the National

Woman’s Party (NWP) was instrumental in raising public awareness of the women’s suffrage

campaign. The party successfully pressured President Woodrow Wilson, members of Congress,

and state legislators to support passage of a 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (known

popularly as the “Anthony” amendment) guaranteeing women nationwide the right to vote. The

NWP also established a legacy defending the exercise of free speech, free assembly, and the

right to dissent–especially during wartime. (See

Historical Overview)

The NWP had only 50,000 members compared to the 2 million members claimed by its

parent organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Nonetheless, the NWP effectively commanded the attention of politicians and the public through

its aggressive agitation, relentless lobbying, creative publicity stunts, repeated acts of nonviolent

confrontation, and examples of civil disobedience. The NWP forced the more moderate NAWSA

toward greater activity. These two groups, as well as other suffrage organizations, rightly

claimed victory on August 26, 1920, when the 19th Amendment was signed into law.

The tactics used by the NWP to accomplish its goals were versatile and creative. Its

leaders drew inspiration from a variety of sources–including the British suffrage campaign,

American labor activism, and the temperance, antislavery, and early women’s rights campaigns

in the United States. Traditional lobbying and petitioning were a mainstay of party members.

From the beginning, however, conventional politicking was supplemented by other more public

actions–including parades, pageants, street speaking, demonstrations, and mass meetings.

In its western campaigns of 1914 and 1916, the CU sent out contingents of organizers and

speakers to states where women already were enfranchised. They targeted candidates for

congressional office and urged voters to use the ballot to express their dissatisfaction with the

lack of action on behalf of a federal suffrage amendment. Transcontinental auto trips, speaking

tours, motorcade parades, banners, billboards, and other methods helped spread the word and

educate the public about suffragists and suffrage issues.

Four years into their campaign and shortly before the United States entered World War I,

NWP strategists realized that they needed to escalate their pressure and adopt more aggressive

tactics. Most important among these was picketing at the White House–a concerted action that

lasted for many months and led to the arrest and imprisonment of many NWP activists.

The willingness of NWP pickets to be arrested, their campaign for recognition as political

prisoners rather than as criminals, and their acts of civil disobedience in jail–including hunger

strikes and the retaliatory force-feedings by authorities–shocked the nation and brought attention

and support to their cause. Through constant agitation, the NWP effectively compelled President

Wilson to support a federal woman suffrage amendment. Similar pressure on national and state

legislators led to congressional approval of the 19

th

Amendment in June 1919 and ratification 14

months later by three-fourths of the states.

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

2

Lobbying and Petitioning

From its outset in 1912, the purpose of the Congressional

Committee of the National American Woman Suffrage

Association (NAWSA), spearheaded by

Lucy Burns and Alice

Paul, was to exert pressure upon Congress to pass an amendment

to the U.S. Constitution giving the right to vote to women across

the nation. Lobbying for a federal amendment remained integral

to the committee’s successor organizations, the Congressional

Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) and the National Woman’s

Party (NWP).

Women’s use of lobbying as a democratic technique for

social change was not new. The practice of exerting pressure upon officeholders to change

existing discriminatory laws limiting women’s opportunities or curtailing their rights as political

beings or as private citizens was a well-established tradition in the women’s rights movement.

At the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, reformers framed resolutions which they brought to the

attention of legislatures and courts and used to educate the general public.

Deputation to the House Rules

Committee. Buck. July 1914.

About this image

Petitioning–the gathering of signatures in support of

resolutions and the formal presentation of these documents to

political representatives–in order to demonstrate graphically the

“will of the people” also was a time-honored political tradition.

The CU presented petitions to members of Congress, and

occasionally organized large delegations to gather on the steps of

the U.S. Capitol, with members from various states set to visit

their respective representatives.

The CU legislative committee compiled a congressional

card index with information about every member of the House

and Senate. These files contained

background about the

individual’s public career, their values, favorite projects, prior

votes, and the issues of greatest concern to their constituents. CU

organizers consulted these files to prepare its lobbyists for

meetings with members of Congress, so as to best address

suffrage from a perspective that would be most meaningful and

persuasive to the lawmaker.

Suffrage petition for all NWP sections

carried to the U.S. Senate by Annie Fraher,

Bertha Moller, Bertha Arnold, and Anita

Pollitzer, campaign of 1918. Harris &

Ewing.

About this image

While NWP legislative committee officers testified at

congressional hearings, petitioned Congress, and monitored and

helped to shape legislative action, the leaders of the CU, and later the NWP, focused much of

their lobbying efforts on President Woodrow Wilson. The Democratic president was initially

receptive to a series of CU delegations, each representing different groups of women–working

women, professional women, women from various states or occupations, social workers,

reformers, and others. Nonetheless, he remained largely unmoved by their appeals. Wilson

claimed that he could not go against the will of his party. He persisted in taking a states’ rights

stance–reiterating his position that women’s voting rights were best determined locally.

U.S. Senate petitioner motorcade,

Hyattsville, Maryland. W. R. Ross. July

31, 1913.

About this image

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

3

In early 1917, Wilson rebuffed a delegation of more than 300 suffrage supporters who

presented him with resolutions drafted at the memorial for

Inez Milholland Boissevain. The

NWP thereafter significantly shifted its strategy toward overt forms of public protest and civil

disobedience. (See Picketing and Demonstrations and Arrests and Imprisonment) While the more

formal political work of the NWP legislative committee continued, the NWP picketing

campaign–its banners fully visible to the president as he came in and out of the White House

gates–became its own form of lobbying. Picketing the White House also sought to influence

international opinion by pointing out the irony of advocating democracy abroad while limiting

the exercise of political rights at home.

As the ratification campaign of 1919-20 commenced, NWP lobbying necessarily shifted

to the state level. NWP officers and organizers fanned out to influence ratification at special

sessions of state legislatures and to persuade state party leaders to back the amendment. In states

where the votes were very close, lobbying by NWP representatives was crucial in convincing the

conflicted or undecided to support the amendment.

After the 19

th

Amendment officially became part of the

U.S. Constitution in August 1920, the NWP continued to use

lobbying and petitioning techniques to work for their new

campaign–the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Beginning in

the 1920s, and continuing until 1972, the organization worked to

introduce the amendment to various sessions of Congress and

urged state governments to support equal rights legislation. NWP

activists also supported the campaigns of women running for

office and drafted pieces of legislation guaranteeing or protecting

women’s rights. They lobbied on behalf of the ERA as delegates

at both Democratic and Republican national conventions.

Lobbying for the Equal Rights

Amendment, U.S. Capitol. Edmonston.

ca. 1923.

About this image

The ERA was finally approved in 1972 by both houses of Congress after decades of

NWP lobbying. Over the next decade, NWP members shepherded the measure through

ratification at the state level, falling short of ratification by only three states in 1982. Following

the failure of the ERA campaign, the NWP regrouped and reassessed its goals. The party ceased

its political lobbying function officially in 1999, when it became a nonprofit educational

organization.

Parades

As soon as Alice Paul and Lucy Burns were appointed to

the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s

Congressional Committee, they began planning a large and

elaborate suffrage parade for Washington, D.C., on the eve of

President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. (See

Historical

Overview) This celebrated event was the first national suffrage

parade in the United States, but it was inspired by earlier and

larger suffrage processions.

Inez Milholland Boissevain preparing to

lead the March 3, 1913, suffrage parade in

Washington, D.C. Harris & Ewing.

About this image

The first American suffrage parades took place in 1908. In

February of that year, a small band of 23 women, affiliated with a

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

4

new militant organization calling itself the American Suffragettes, marched up Broadway in

New York City to a meeting hall on East 23

rd

Street. A few months later, 300 suffragists in

Oakland, California, marched into a state political convention holding banners and streamers

demanding the right to vote. That same month, 100 women in Boone, Iowa, paraded through the

streets with suffrage banners welcoming national leader Anna Howard Shaw to their state

suffrage convention.

The first sizable suffrage parade, however, took place in

New York City on May 21, 1910. More than 400 women

marched and many more rode in automobiles. This parade, as

well as the increasingly larger ones in May 1911 (an estimated

3,000 marchers), May 1912 (10,000), and November 1912

(20,000), were organized principally by Harriot Stanton Blatch,

who like Paul and Burns, participated in the British suffrage

campaign.

The earliest American suffrage parades were influenced

both by British suffrage processions as well as a long tradition of

parades in the United States. The American tradition included

patriotic marches commemorating July 4, temperance

demonstrations, religious processions, May Day parades

organized by socialists and labor groups, and marches and street demonstrations by striking

workers, such as those organized by female factory workers in

Lynn, Massachusetts, in the 1860s, and by New York City

shirtwaist workers in 1909-10.

Crowd converging on marchers and

blocking parade route during March 3,

1913, inaugural suffrage procession,

Washington, D.C. Leet Brothers.

About this image

Although many women moved freely in the public

sphere–including those who worked outside the home in paid and

volunteer positions–the prevailing notion among middle-class

circles in the early 1900s was that only women of supposedly

poor character (for example, prostitutes) walked the streets.

Suffragists, conscious of the boundaries that they were crossing,

steeped their parades in pomp and pageantry, developing highly

organized and theatrical processions. Their intent was to dazzle

and impress onlookers, attract recruits, grab the attention of

legislators who found it easy to ignore suffrage petitions, and

dispel unfavorable perceptions of suffragists as pathetic spinsters or aggressive shrews who

neglected their families and browbeat their husbands.

Members of the Congressional Union for

Woman Suffrage pasting advertisements

announcing the May 9, 1914, procession

to the U.S. Capitol to present resolutions

to Congress. May 1914.

About this image

Marchers were instructed by parade organizers to walk with dignity and convey a serious,

respectable demeanor compatible with that of a responsible voter. Watching women of all classes

parading down public thoroughfares demanding voting rights was disturbing to many men and

even some women, including initially, moderate suffragists. Carrie Chapman Catt, for example,

declined to participate in a 1909 parade saying: “We do not have to win sympathy by parading

ourselves like the street cleaning department.” The controversy within the suffrage ranks over the

propriety of parades reflected why such events were newsworthy–they challenged existing

conventions of how women should behave in public.

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

5

In organizing their March 3, 1913, parade, Paul and

Burns borrowed elements from many of the earlier parades. To

reinforce the notion of a universal demand for suffrage, women

marched in well-identified groups by state or occupation

(including teachers, lawyers, actresses, nurses, librarians, and

factory workers). This structured procession reflected, in part, the

decentralized aspect of the suffrage movement and the role of the

national organizations in bringing together the state chapters and

branches. College students and mothers–some marching with

children and infants–had their own sections, as did men’s

suffrage leagues.

Women and young girls on “Votes for

Women” float, winner of first prize in

Vineland, New Jersey, suffrage parade.

ca.1914.

About this image

Bands and opulent floats provided visual relief from the steady stream of marchers. Some

participants wore special color-coordinated outfits; others wore

white dresses (in the temperance tradition) adorned with colorful

sashes–gold for NAWSA and later, purple, white, and gold for

the militant Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. Hats,

dresses, pins, buttons, and sashes were made or purchased from

local department stores that stocked suffrage supplies.

Carefully designed and sewn or embroidered banners

were used as rhetorical devices to convey political messages.

Banners commemorated famous women who inspired the

suffragists, identified the diverse groups who had come together

to support the cause, and were critical in conveying who these women were and why they were

marching. They also helped transform the traditionally masculine streetscape into a forum for

women’s viewpoints.

College section of the March 3, 1913,

suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.

About this image

Pageants

A critical component of the first national suffrage parade on

March 3, 1913, in Washington, D.C., was the elaborate tableau, “The

Allegory,” produced by pageant designer

Hazel MacKaye. Through sheer

persistence and moxie,

Alice Paul secured permission from government

officials to use the grand steps of the Treasury Building during working

hours to mount a feminist pageant. The performance included 100

classically costumed women and children representing ideals such as

Freedom, Justice, Peace, Charity, Liberty, and Hope as well as

outstanding female historical figures including Sappho, Joan of Arc, and

Elizabeth of England. More than 20,000 people reportedly watched the

pageant, including a reporter from the New York Times who gushed that

it was “one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged in

this country.”

“Liberty and her Attendants”–

Florence F. Noyes in “The

Allegory” tableau.

Washington, D.C. L & M

Ottenheimer. March 3, 1913.

About this image

Like parades, suffrage pageants and tableaus had deep historical

roots, which the suffragists tapped when looking for ways to attract

publicity and new members. Some suffragists were drawn to the idea of

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

6

linking artistic inclinations with political activism. Others preferred performing on a stage or

assisting behind-the-scenes rather than marching in a parade.

MacKaye, the best known of all pageant directors,

created four pageants for the Congressional Union for Woman

Suffrage (CU) and National Woman’s Party (NWP) between

1913 and 1923. She claimed that nothing surpassed pageants “for

the purpose of propaganda,” believing that these events could

convert followers, raise money, and elevate morale among

suffrage workers. By making women, both mythical and real, the

central figures in these plays, MacKaye and other pageant

organizers empowered both the participants and the women who

watched these tableaus.

The year after directing “The Allegory,” MacKaye created

“The American Woman: Six Periods of American Life,” a multi-

part tableau sponsored by a New York men’s suffrage league and

staged at a regimental armory in New York. The CU promoted

this feminist pageant and hired MacKaye to produce a third

pageant, titled “Susan B. Anthony,” for its December 1915

convention in Washington. MacKaye spent months researching

Anthony’s life and pouring over copies of the History of Woman

Suffrage. The result was so impressive that it reportedly inspired

CU members to carry on Anthony’s militant tradition of suffrage

activism.

Agnes Lester, Marjorie Follette, Emily

Knight, Elizabeth Van Sickle, and Carol

Lester as warriors in the “Dance Drama

Depicting the Progress of Woman,”

Seneca Falls, New York. Underwood &

Underwood. July 20, 1923.

About this image

Pageants outlived parades as a publicity tool and were

brought forward into the NWP’s equal rights campaign.

MacKaye’s final two pageants for the NWP were held

respectively in July and September 1923 in Seneca Falls, New

York, and in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Both pageants

celebrated the 75

th

anniversary of the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls in 1848

and sought to attract new members to the party as it prepared to have the equal rights amendment

introduced in Congress. The Colorado pageant was spectacularly mounted at the Garden of the

Gods rock formation. It created a visual backdrop that competed with the

1840s costumes and

rivaled the staging of the first national pageant on the Treasury Building steps.

Eleanor Van Buskirk (left) and ritualists

from the "Forward into Light" pageant at

the NWP’s “Women for Congress”

conference. August 1924.

About this image

Picketing and Demonstrations

In December 1916, after nearly four years of lobbying, petitioning, parading, and

engaging in one clever publicity stunt after another (See

Historical Overview), Alice Paul and

several key members of the Congressional Union’s executive committee felt that their tactics

were growing stale and ineffective. Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of suffrage pioneer

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, told the committee: “We can’t organize bigger and more influential

deputations. We can’t organize bigger processions. We can’t, women, do anything more in that

line. We have got to take a new departure.”

The NWP had already withstood mob violence while demonstrating with anti-Wilson

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

7

banners outside a Chicago auditorium during the October 1916 presidential campaign. Blatch

believed that the time had come for suffragists to escalate the pressure on President Woodrow

Wilson, whom she supposedly told: “I have worked all my life

for suffrage, and I am determined that I will never again stand in

the street corners of a great city appealing to every Tom, Dick,

and Harry for the right of self-government.” What Blatch had in

mind was picketing, a tactic used effectively in New York by her

former organization, the Women’s Political Union, and with

which she–and Paul–were familiar from their experiences with

British suffragists.

No one, however, had apparently ever thought or dared to

picket the White House and convincing the other committee

members to picket the White House was not easy. This situation

changed, however, when Wilson summarily dismissed a

deputation of suffragists who tried to present him with a series of

suffrage resolutions passed during

Inez Milholland Boissevain’s memorial service. The next day,

on January 10, 1917, a dozen determined women left the Congressional Union (CU)

headquarters at Cameron House and marched to the White House. They carried tricolor purple,

white, and gold flags as well as two banners. One read, “Mr President, What Will You Do For

Woman Suffrage?” The other banner featured words taken from Milholland’s last speech. It

asked, “How Long Must Woman Wait For Liberty?”

N

WP members picket outside the

International Amphitheater in Chicago,

where Woodrow Wilson delivers a

speech. October 20, 1916.

About this image

Every day for the next few months, regardless of the

weather, a group of women marched from CU headquarters to

the White House to take up their stations as “silent sentinels.”

NWP organizers carefully planned every detail. Banners were

made and volunteers were recruited and scheduled for shifts of

several hours. Nearly 2,000 suffragists traveled from 30 states to

take turns on the picket line. Special days were set aside for

women representing specific states, schools, organizations, and

occupations. When the United States entered World War I in

April 1917, however, some women resigned from the NWP

because they viewed picketing as unpatriotic as well as

unwomanly. These departures, however, were offset by new

recruits–including many socialists, labor organizers, and average

working women–who were attracted to the militancy, justice, and

free speech aspects of the campaign.

Wage-earning women march to the White

House gates to picket on their day off,

Sunday. February 18, 1917.

About this image

Some suffragists found picketing an exhilarating and bonding experience, even more so

after the first arrests on June 20, 1917, further raised the spirit of determination and moral

purpose. Other suffragists, however, described how the “sockets of their arms ache[d] from the

strain.”

Doris Stevens wrote of the tedium, “anything but standing at the President’s gate would

be more diverting,” and explained that she and others spent their time thinking “when will that

woman come to relieve me.”

1

At times, the pickets had more to worry about than achy arms and

boredom. Mob violence grew after the United States entered World War I, with two especially

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

8

noteworthy attacks on the suffragists in the summer of 1917. These attacks followed the initial

unfurling of banners comparing the president of the United States with the Russian czar and the

German kaiser as far as denying citizenship rights in their respective countries. (See

Detailed

Chronology [PDF] and Historical Overview).

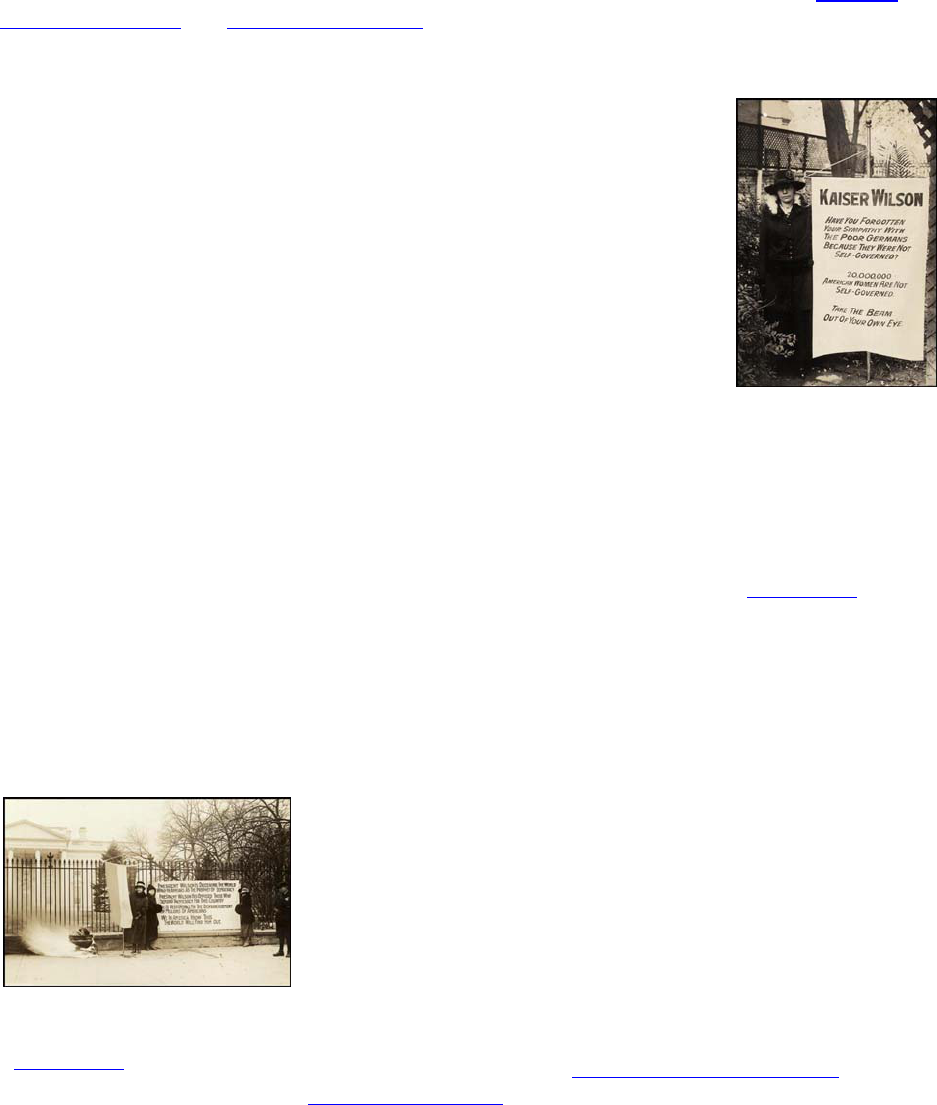

Banners, emblazoned with thought-provoking messages, were essential elements of the

picketing campaign. They were the medium for explaining the picket’s purpose and for

embarrassing and pressuring Wilson into action. Many years later Paul

still expressed pride, noting, “Our banners were really beautiful.”

2

The

banners also sometimes inflamed onlookers and became targets of

vandalism. The first of the famous “Russian” banners lasted less than a

day. Pulled away from its bearer, it survived only a few minutes before

the crowd shred it to pieces. The same fate befell the “Kaiser Wilson”

banners. Many of the most effective banners carried quotes lifted directly

from Wilson’s own speeches. Parroting Wilson’s words helped to

highlight the government’s hypocrisy in supporting democracy abroad

while denying its women citizens the right to vote at home. Also, as one

historian noted, the tactic may have helped the suffragists avoid

prosecution under federal espionage and sedition laws during a period of

unprecedented government repression.

3

Even if mob violence was the exception rather than the rule,

underlying tension and intimidation existed on almost any given day.

Suffragist Inez Haynes Irwin wrote of the “slow growth of the crowds; the

circle of little boys who gathered about . . . first, spitting at them, calling

them names, making personal comments; then the gathering of gangs of

young hoodlums who encourage the boys to further insults; then more and

more crowds; more and more insults. . . . Sometimes the crowd would edge nearer and nearer,

until there was but a foot of smothering, terror-fraught space between them and the pickets.”

4

When skirmishes broke out, the police invariably stood and watched, or else they arrested the

women on charges of obstructing traffic.

During World War I,

Virginia Arnold holds a

banner accusing President

Wilson of forgetting to

grant full democracy in this

country while sending

troops abroad to make self-

government possible for the

rest of the world. Harris &

Ewing. August 1917.

About this image

The White House was not the only venue for picketing. Demonstrations also took place

in nearby Lafayette Park, where in August and September 1918, the NWP burned copies of

Wilson’s speeches and his picture in effigy. The U.S. Capitol

and Senate office buildings were also targeted; picketing at the

latter began in October 1918, when the NWP grew tired of

waiting for the Senate to pass a suffrage amendment.

In January 1919 the focus again returned to the White

House with the burning of “watch fires of freedom.” Cauldrons

were set up outside the White House and in Lafayette Park to

burn Wilson’s speeches and pressure him to use his influence to

secure the remaining two votes necessary for Senate passage of

the amendment. Risking arrest, demonstrators kept the fires

burning continuously. (See

Detailed Chronology [PDF] and

Historical Overview).

N

WP “watch fire of freedom” burns

outside the White House. Harris & Ewing.

January 1919.

About this image

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

9

Wilson could not escape the pickets by leaving town. In February 1919 NWP members,

carrying banners reminding him of his pledge to support the suffrage amendment, met him in

Boston upon his return from Europe. The police roughed up the demonstrators before arresting

them. These pickets served eight-day sentences in the Charles Street jail. The next month,

demonstrators were brutally attacked by police, soldiers, and onlookers when they picketed

outside the New York Metropolitan Opera House, where Wilson was speaking.

At great personal cost to their health, safety, and reputations, American suffragists risked

arrest and imprisonment to secure voting rights for women. Through their choice of tactics and

nonviolent protests, they helped to defend for all Americans the right to assembly and freedom of

expression.

Arrests and Imprisonment

NWP activists–arrested, tried, and in many cases imprisoned on charges related to

picketing, speaking at rallies in public parks, and other forms of demonstration–devised another

series of tactics to deal with their experiences in court and in detention. Again,

Alice Paul and

Lucy Burns’s work in the British suffrage movement helped to frame responses in America.

Paul’s Quaker background provided her with a sophisticated view of the connections between

ethical civil disobedience and political action. Burns’s sympathy with labor organizations and the

Left helped develop her responses.

Most important among the strategies used in court–and later in

detention–in either the

District of Columbia jail or Virginia’s Occoquan

Workhouse, was the demand that arrested suffragists be treated as political

prisoners. Arrested on criminal charges of obstructing traffic, NWP activists

emphasized that their assembly on city sidewalks and their silent and

peaceable picketing had been conducted entirely within legal grounds. Under

the leadership of Paul and Burns they began insisting that the courts

acknowledge that the real motivation for their arrests was politically based.

They also placed the blame for the repressive response to their actions

squarely on the Wilson administration.

Beginning in fall 1917, jailed NWP pickets backed up this insistence

on the political nature of their imprisonment with action–or more accurately,

inaction–within the jail and workhouse. Following the lead of Burns, Paul, and

others, imprisoned pickets instituted a campaign of nonviolent, “passive”

resistance. They refused to do their assigned sweatshop sewing and manual

labor. Further, they refused to eat until their political status was acknowledged. Hunger strikes

became one of the most powerful and graphic tools used by the NWP to gain public awareness of

the dire nature of the denial of rights to women.

Vida Milholland in

District of Columbia

j

ail. Harris & Ewing.

July 4, 1917.

About this image

For many of the middle-class and wealthy pickets, jail was a shock. Conditions at both

the District and Virginia facilities were uncomfortable at best. Sanitation was severely lacking.

Bedding went unwashed and was reused by different prisoners for months. Food had little

nutritional value or appeal, and worse, was often riddled with worms or insects. At one point,

jailed suffragists sent a heap of worms removed from their soup to the warden on a spoon.

Most NWP activists came from sheltered, privileged backgrounds or enjoyed a highly

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

10

respectable social status through their education, career, or marriage. Yet on principle and in

defense of civil liberties, many chose to enter jail instead of paying a fine. Imprisonment often

provided them with a firsthand education about how readily those less privileged could find their

rights abridged within the court, police station, workhouse, and jail.

In order to emphasize the “common criminal” status of the NWP prisoners, wardens

incarcerated them with women who had been detained for streetwalking, homelessness, or petty

crime. In a time when Jim Crow racial segregation still prevailed,

wardens also housed white demonstrators with African-American

detainees. The pickets discovered these women had been imprisoned as a

result of their acute poverty or even because they had been subjected to

sexual exploitation or domestic violence.

Doris Stevens, one of the jailed

NWP protesters, observed that the lessons learned about prison conditions

and inequities encouraged many imprisoned suffragists to also turn to

prison reform.

As the process of picketing, arrest, sentencing, and imprisonment

continued from June into late fall 1917, former government leniency and

pardons gave way to more severe sentences. Many of the suffragists

arrested earlier in the campaign received sentences of a few days to a

month, and sentences were sometimes truncated or suspended by pardon.

In the new political climate, however, Alice Paul was sentenced to seven

months, and Lucy Burns to six months. As the suffragists began

demanding political prisoner status, their situations became more threatening. Imprisonment

became more closely synonymous with compromised health and bodily harm.

Lucy Branham protests the

p

olitical imprisonment of

Alice Paul. Harris & Ewing.

1917.

About this image

The dangerous situation inside the detention facilities escalated, peaking in November in

with what became known as the “Night of Terror.” Occoquan Superintendent Raymond

Whittaker threatened prisoners that he would end the picketing, even if it cost some women their

lives. On November 15, 1917, he instigated the use of force by guards against a newly

imprisoned set of pickets, a group that included many core NWP national and state organizers.

Women were beaten, pushed, and bodily carried and thrown into

their cells when they refused to cooperate and attempted to

negotiate with the superintendent. Other means of physical

intimidation also were used.

Dora Lewis was knocked

unconscious and Lucy Burns handcuffed with her arms above

her head.

The next day, 16 of the women began a hunger strike,

including Lewis and Burns. They followed the example set the

previous month by Alice Paul and

Rose Winslow. During her

protest, Paul was subjected to psychiatric evaluation, threatened

with transfer to an institution for the insane, and force-fed. News

of her treatment was leaked outside the facility. When Burns and

Lewis grew weak from refusing food, they, too, were force-fed. Burns had a tube forced up her

nose rather than through her mouth, resulting in bleeding and injury.

Kate Heffelfinger after her release from

Occoquan Workhouse, 1917.

About this image

The assaultive nature of the force-feeding process was by all accounts a torturous

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

11

experience for the women, one that they withstood repeatedly. Verbal techniques of

psychological duress also were used to weaken the women’s resolve. Isolated from one another,

some prisoners were told falsely during their force-feedings that they were the only person still

maintaining the hunger strike–claims that they knew not to believe.

The campaign of civil disobedience and the public outcry over the prisoners’ treatment

led to the release of Paul, Burns, and other suffrage prisoners at the end of November 1917. The

NWP subsequently staged a mass meeting in Washington, D.C., to honor the

women who had

served time in jail or prison. A “Jailed for Freedom” pin, fashioned after one used in Britain, was

affixed as a badge of honor on the formerly imprisoned women attending the meeting. The

arrests, however, continued.

Picketing proceeded at the White House, in front of the U.S. Capitol, and at the

Congressional office buildings. More NWP protesters were imprisoned and participated in

hunger strikes in 1918. The watch fire demonstrations of 1919 put even more women behind bars

for brief sentences. By the time that suffrage was won in 1920, 168 NWP activists had served

time in prison or jail.

The NWP used the experience of imprisoned pickets to

help spread the call for a federal suffrage amendment. Ex-

prisoners began traveling during a determined lobbying

campaign to push the suffrage amendment through Congress. In

February 1919 the “Prison Special” tour began from Union

Station in Washington, D.C.–with former prisoners traveling on a

train called the “Democracy Limited.”

Mass meetings were held around the country–from

Charleston, South Carolina, to New Orleans and Los Angeles,

Denver, Chicago, and many other cities, ending in New York in

March.. Among the 26 speakers on this tour–often outfitted in

prison dress, were veteran NWP organizers Vida Milholland,

Abby Scott Baker, Lucy Branham,

Lucy Burns, and Mabel Vernon as well as the elderly and courageous Mary Nolan–often touted

as the NWP’s “oldest picket.” Their message was well received and they drew large audiences.

The “Prison Special” tour helped create a groundswell of local support for the ratification effort

that began in the states a few months later, following the approval of the 19

Amendment by

Congress in June 1919.

th

Speakers on “Prison Special” tour, San

Francisco, 1919.

About this image

The Library of Congress | American Memory

Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party

12

Notes

1. Linda G. Ford, Iron Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party,

1912-1920 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991), 127.

2. Ibid., 126.

3. Linda J. Lumsden, Rampant Women: Suffragists and the Right of Assembly (Knoxville:

University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 129.

4. Inez Haynes Irwin, The Story of Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party ( Fairfax, VA:

Denlinger’s Publishers, 1920; reprint 1977).