Cover image:

© adventtr/Getty Images

Copyright © 2020 McKinsey &

Company. All rights reserved.

This publication is not intended to

be used as the basis for trading in

the shares of any company or for

undertaking any other complex or

signicant nancial transaction

without consulting appropriate

professional advisers.

No part of this publication may be

copied or redistributed in any form

without the prior written consent of

McKinsey & Company.

Contents

Store operations

Supply chain

5

22

16

11

31

A transformation in store

Brick-and-mortar retail stores need to up their game.

Technology could give them a signicant boost.

Smarter schedules, better budgets: How to improve

store operations

Through activity–based labor scheduling and budgeting,

retailers can become more ecient while improving customer

service and employee satisfaction.

Bending the co

st curve in brick-and-mortar retail

Retailers can achieve next-generation store eciency

by breaking down silos and optimizing total cost across the

value chain.

Supply chain of the future: Key principles in building

an omnichannel distribution network

As omnichannel shopping is becoming the new norm,

consumer and retail companies must be ready to deliver fast,

impeccable omnichannel service. Doing so requires a new

supply chain network approach.

A retailer’s guide to successfully navigating the race

for same-day delivery

Same-day delivery: Consumers’ expectation for same-day

delivery is rising and putting pressure on retailers’ supply

chains.

38

Better service with connected inventory

It is not just the customer experience that manufacturers

and retailers enhance by extending their reach to the entirety

of stocks in the market.

Hamburg

Cologne

Munich

>1,000,000

Inhabitants

>500,000–1,000,000

>200,000–500,000

Warehouse

coverage

Retailer same-day o ering

in top 20 cities

Amazon vs top 20 non-food

and top 13 grocery retailers

Same-day coverage of relevant population,1 Amazon vs disguised

omnichannel fashion retailer

by type of competition, %

28 stores across Germany, covering 5 of

Germany’s 20 biggest cities

Ongoing testing and buildup of

ship-from-store capabilities

Competition area

(Amazon and retailer)

Area at risk

(Amazon only)

Retailer

monopoly area

(retailer only)

Source: Alteryx; BKG; ESRI ArcGIS; MB-Research; McKinsey analysis

1

Relevant population areas dened as high density (>750 inhabitants/km²) and/or high income (purchasing power >€21,900 per capita); viable market

coverage dened as area within 30 minutes driving time from respective retail location.

Population 22 16 7

23 17 7

Purchasing

power coverage

Viable market coverage for same-day

delivery via ship from store1

%

1

Relevant population areas dened as high density (>750 inhabitants/km²) and/or high income (purchasing power >€21,900 per capita); viable market

coverage dened as area within 30 minutes driving time from respective retail location.

Stores

60

50

40

20

30

10

0

50

40

20

30

100

Source: Alteryx; BKG; ESRI ArcGIS; MB-Research; McKinsey analysis

Store location

Berlin

1

Beyond procurement: Transforming indirect

spending in retail

If retailers treat indirect costs as an opportunity for business

transformation rather than just a procurement matter, they can

boost return on sales by as much as 2 percent.

Rethinking procurement in retail

For retailers, procurement is no longer solely a matter

of negotiating “A” brands. Private labels and verticalization

are trending. Advanced approaches and tools help get

procurement in shape for the future.

Six emerging trends in facilities management

Outsourcing, workplace strategies, and technology innovations

hold immense potential for companies seeking to reduce costs

and improve productivity in facilities management.

The end of IT?

Retailers who want to stay ahead of the pack and drive

business results through technology innovation are rethinking

the setup of their IT departments.

Automation in logistics: Big opportunity, bigger

uncertainty

As e-commerce volumes soar, many logistics and parcel

companies hope that automation is the answer. But as this

second article in our series on disruption explains, things

are not so simple.

Next–generation supply chain—transforming your

supply chain operating model for a digital world

In a digital age, most supply chains run on old principles and

processes. A few leaders can show us how a new operating

model can answer the demands of today—and tomorrow.

Supply chain

(continued)

50

62

Procurement

67

76

82

Tech

94

44

The invisible hand: On the path to autonomous

planning in food retail

It’s not news to food retailers: sometimes your stocks are too

high, sometimes they’re too low. Advanced planning now gives

them entirely new options for solving the expensive problem—

and cuts costs in the process.

Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 20202

Heightened customer expectations, massive advancements in technology, and the rise of omnichannel

commerce are just a few of the trends reshaping the world of retail. In an industry already known for thin

margins, these changes can increase cost pressures and uncertainty for retailers—all while opening the

door to significant opportunities. Traditional approaches will no longer work in the face of change; now is

the time to clearly define new aspirations, make fundamental changes to operating models, and rethink

retail. Those that make moves now may enjoy a sustained advantage for decades to come.

In this publication we examine some of the most pressing challenges retailers face and the transformative

journeys many are on right now. You will find a range of new perspectives across retail operations,

including, store operations, supply chain, procurement, and information technology (IT). As the rules of

retail are being redefined, these fundamental areas of retail operations are in need of fresh thinking.

Introduction

McK Retail compendium 2020

Introduction

Exhibit

Retail operations

Store operations Supply chain Procurement

Information technology (IT)

We provide a new take on store operations—while flashy technology attracts and engages customers

in the “store of the future,” the make-or-break technology is actually behind the scenes. That’s the

technology that gathers and connects data for a seamless customer experience. In our own “store of the

future” this includes dwell sensing, RFID, heavy investments in the data lake, and the logic needed to map

the customer journey. But technology is only one piece of the puzzle; solving the operations equation also

involves analytics, new store processes, and upskilling the store team. Such a transformation can add

several points of profitability to the average store.

Introduction 3

In supply chain, we identify the measures successful companies have taken, which include fundamentally

transforming their supply chain to enable a true omnichannel experience, taking more agile approaches

when designing their supply chain network, building new capabilities, and adjusting their operating model.

We take a look at how retailers can keep up with customer expectations as omnichannel shopping becomes

the new normal—including building and maintaining a connected inventory strategy, which increases

transparency and access to stock wherever it sits in the supply chain to better fulfill customer needs.

In procurement, we explore the unrealized opportunity in indirect spending—spend on goods or

services not for resale. Companies can and should take a closer look at indirect spending and embed

new processes and ways of working—including using more sophisticated analytics tools, strengthening

supplier collaboration, and taking a broader, business-level view of indirect spend, rather than making it

simply a procurement issue. Retailers that elevate indirect spending initiatives can cut costs, capture more

value, and uncover cash that can be reinvested as part of a broader business transformation.

We recognize that today, nearly every change a retailer makes depends on technology solutions—and

they often fall short of expectations. With an entrenched divide between the IT department and the rest

of the company, many brick-and-mortar retailers struggle to get value out of their IT investments—or get

started at all. Retailers must become technology-driven organizations, and that will require upending

the status quo. In the end, transforming mind-sets, capabilities, and ways of working is critical not only in

established IT areas like application development and infrastructure but in core commercial divisions like

sales, merchandising, supply chain, and marketing.

Through our research and analysis, we seek to identify opportunities, provide insight into how to act on

them, and learn from those that have forged ahead. We hope these perspectives on retail operations aids

your organization in embracing change and realizing a new vision for retail.

4 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

Frank Sänger

Senior Partner, Cologne

Karl-Hendrik Magnus

Partner, Frankfurt

Praveen Adhi

Partner, Chicago

A transformation

in store

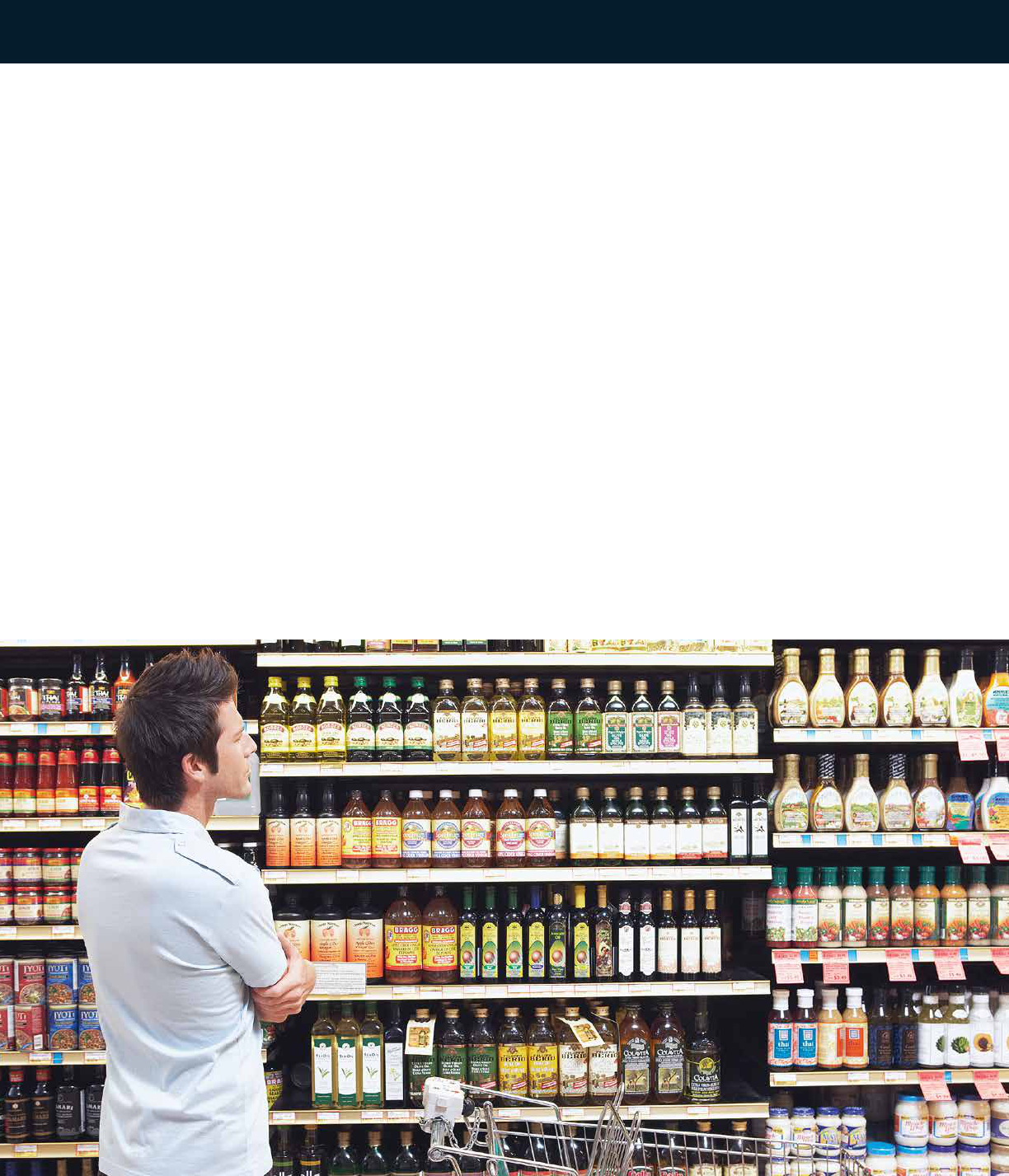

© EyeEm/Getty Images

by Praveen Adhi, Tiany Burns, Sebastien Calais, Andrew Davis, Gerry Hough, Shruti Lal, and Bill Mutell

STORE OPERATIONS

Brick-and-mortar retail stores need to up their game. Technology

could give them a significant boost.

5A transformation in store

Now should be a great time in US retail. Consumer

confidence has finally returned to pre-recession

levels. Americans have seen their per capita,

constant-dollar disposable income rise more than

20 percent between the beginning of 2014 and

early 2019.

Yet despite the buoyant economic environment,

many brick-and-mortar stores are struggling.

In part, that’s due to the rise of e-commerce,

which since 2016 has accounted for more than

40 percent of US retail sales growth. In our

most recent consumer survey, 82 percent of US

shoppers reported spending money online in the

previous three months, and the same percentage

used their smartphones to make purchasing

decisions. Not surprisingly, younger shoppers favor

e-shopping even more: 42 percent of millennials

say they prefer the online retail experience and

avoid stores altogether when they can.

Meanwhile, the strong economy and record-low

unemployment are increasing wage pressure and

store operating costs. In the last three years, more

than 45 US retail chains have gone bankrupt.

Retail stores have a real future

Yet rumors of the physical store’s death are

exaggerated. Even by 2023, e-commerce is

forecast to account for only 21 percent of total

retail sales and just 5 percent of grocery sales.

And with Amazon and other major internet players

developing their own brick-and-mortar networks,

it is becoming increasingly clear that the future of

retail belongs to companies that can offer a true

omnichannel experience.

Retailers are already wrestling with omnichannel’s

demands on their supply chains and back-office

operations. Now they need to think about how they

use emerging technologies and rich, granular data

on customers to transform the in-store experience.

The rewards for those that get this right will be

significant: 83 percent of customers say they want

their shopping experience to be personalized in

some way, and our research suggests that effective

personalization can increase store revenues by

20 to 30 percent.

Several new technologies have reached a tipping

point and are set to spill over onto the retail

floor. Machine learning and big-data analytics

techniques are ready to crunch the vast quantities

of customer data that retailers already accumulate.

Robots and automation systems are moving out

of factories and into warehouses and distribution

centers. The Internet of Things allows products

to be tracked across continents or on shelves

with millimeter precision. Now is a great time for

retailers to embrace that challenge of bringing

technology and data together in the off-line world.

The evolving consumer journey

How will these technologies reshape the shopping

experience? To find out, let’s follow one consumer on

a journey through the store of future (Exhibit 1).

As Jonathan arrives at his favorite grocery retailer,

the store recognizes him, its systems alerted to his

presence either as his smartphone connects to the

in-store Wi-Fi or perhaps by a facial-recognition

technology that he has signed up to use. Once

Jonathan agrees to log in, the store accesses the

Several new technologies have reached

a tipping point and are set to spill over

onto the retail oor.

STORE OPERATIONS

6 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

shopping list he’s been building at home by scanning

items with his phone as he uses them up. As he walks

the aisles, smart shelf displays illuminate to show

the location of those items, while also highlighting

tailored offers, complementary items, and regular

purchases that didn’t make it onto the list.

Jonathan is tempted by a new, personalized

promotion that pops up on his phone as he

approaches the prepared-meals aisle. But because

he prefers organic foods, he wonders about the

product’s ingredients. As he scans the package

with his smartphone, an augmented-reality display

reveals the origin of its contents, along with its

nutrition information and even its carbon footprint.

His bag full, Jonathan leaves the store. There was

no need to check out: RFID scanners and machine-

vision systems have already identified every item

he packed, and his credit card, already on file in the

retailer’s systems, is debited as he passes through

the doors.

The evolving associate and

manager journeys

Technology won’t just reshape the customer

experience in tomorrow’s stores: working in retail

will look will look very different too (Exhibit 2).

David works part time as an associate in the store’s

fresh-foods department, fitting in shifts around his

studies and family life. He negotiates his schedule

each week using a mobile app. The store runs a

bidding system, and staff can earn a premium by

volunteering for busy or hard-to-fill shifts. The

technology also makes it easy for David to trade

shifts when he has a conflict.

The store rarely struggles to get the people it needs,

however. David loves working there because he

is passionate and knowledgeable about food. His

duties include some manual tasks such as stocking

or picking for online orders, but the work is light.

Sensors on and above the shelves monitor the

status of stock, a machine-learning system plans

Exhibit 1

2019

A transformation in store CJ

Exhibit 1 of 3

The consumer’s journey is evolving.

1

Based on dened-benet pension funds with funds under management >$1 billion with allocation to private equity.

Source: Pensions & Investments; McKinsey analysis

Technology powers

shopping convenience

In-store communications not

only help customers nish

their shopping lists but also

provide tailored promotions

and detailed product

information. And they

eliminate checkout lines.

7A transformation in store

the replenishment schedule, and items are delivered

or taken away by robot carts that glide silently and

safely through the store.

David spends most of his time interacting with

customers, offering advice on new products and

recipes or answering their questions. He has

a handheld terminal that he can use to acquire

information on each customer’s preferences and

shopping habits. If a customer can’t find something

on the shelves, he can pinpoint the location and

real–time stock level of every item at a glance or

suggest different items based on that customer’s

shopping habits.

Meanwhile, Rebecca, the store manager, is thinking

about plans for a big new promotion that starts next

week. The project will involve significant changes

to the range of items on display including setting

new fixturing in the produce area. But that’s nothing

new: the store is always adapting its stock and

presentation, and Rebecca spends most of her time

working with colleagues to improve and fine-tune

its offerings. It helps that many previously time-

consuming tasks, such as associate scheduling and

reporting, are now handled automatically by artificial-

intelligence tools. Her phone alerts her when a

situation needs real attention in real time, such as a

promotion that’s not selling as well as in other stores.

This means she can focus her efforts on performance

and service improvements, aided by the store’s

sophisticated performance-analysis systems.

David and Rebecca already have a pretty good

idea of how the new promotional set will work

because they’ve tried it out in virtual reality using an

interactive digital twin of the store. Conversations

with customers have given them an idea for

tweaking the offer’s presentation, and they are

discussing the possible changes now to boost

sales, rather than rigidly adhering to a formula

devised and handed down from above.

Exhibit 2

2019

A transformation in store CJ

Exhibit 2 of 3

The associate’s journey is also changing.

1

Based on dened-benet pension funds with funds under management >$1 billion with allocation to private equity.

Source: Pensions & Investments; McKinsey analysis

New tools improve retail jobs

Mobile–based shift planners

let associates manage their

schedules and give them more

detailed, accurate information

so they can have better

interactions with customers.

STORE OPERATIONS

8 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

The financial impact of

in-store technology

There’s another area that is set to look very different

in the store of the future, and that’s the store’s P&L

sheet. And while our example has been taken from

grocery retail, this impact will be noticeable across

the sector. Personalized offerings and optimized

assortments will likely raise sales and cut waste,

while opportunities to upsell and cross-sell, either

automatically or in person, can increase basket sizes

and conversion rates.

The profile of the workforce will change as well:

skilled and knowledgeable associates will expect

to earn more, pushing hourly rates up by about

20 percent. Total wages are likely to fall, however, as

automation and technology help shift the balance

of labor spend toward value-added and customer-

facing work.

Overall, we believe the store of the future is likely to

achieve EBIT margins twice those of today, with the

added benefits of improved customer experience,

better employee engagement, and an easier-to-

run store (Exhibit 3). The technology necessary to

achieve this transformed P&L is available now, and

we calculate that it is ROI-positive.

Are you ready?

The store of the future is still in its infancy, but every

one of the technologies described above exists

today as a commercial product not just a prototype

or proof-of-concept. Retail leaders should act now

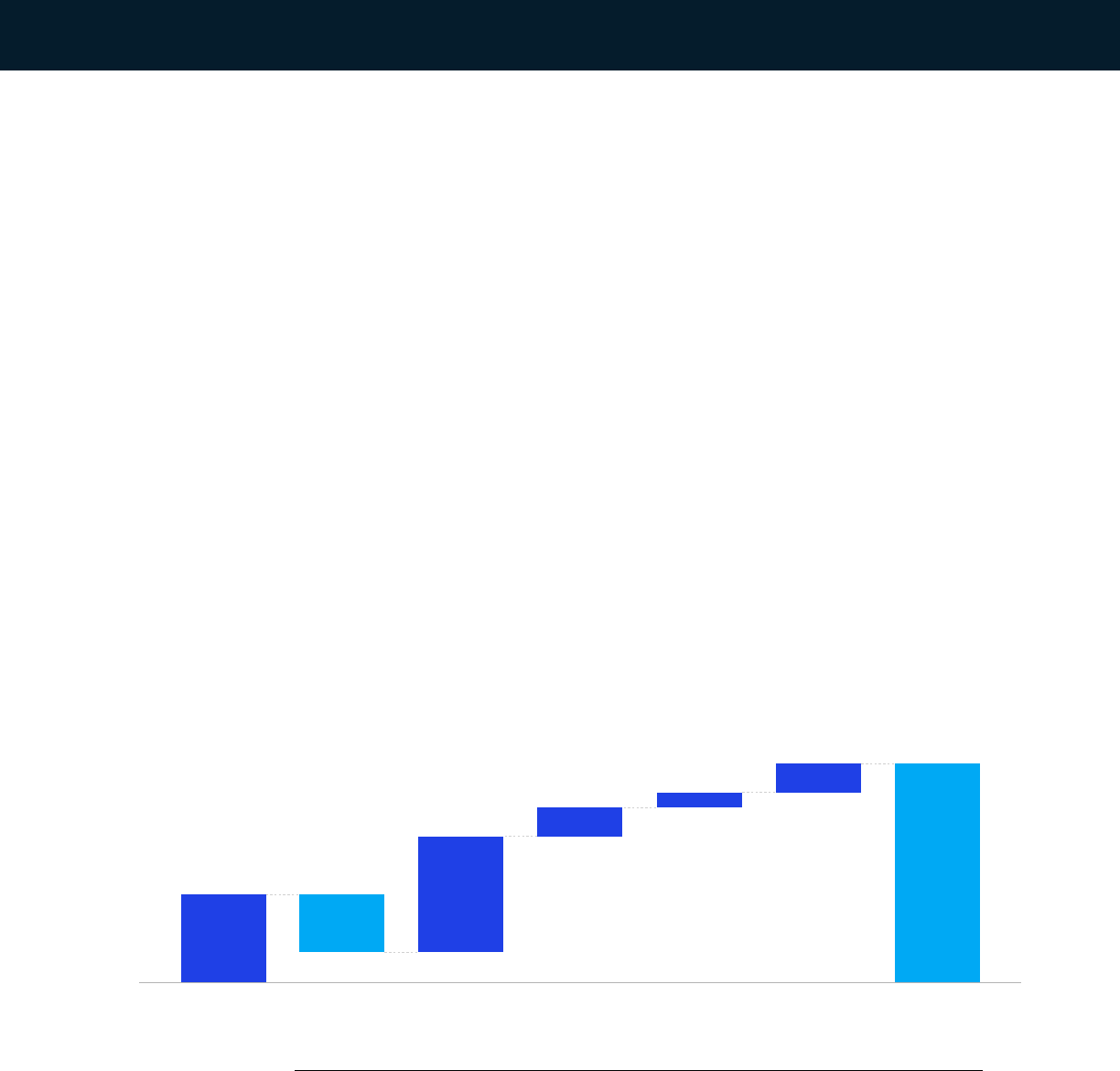

Exhibit 3

2019

A transformation in store CJ

Exhibit 3 of 3

Technology will likely double store protability.

1

Earnings before interest and taxes.

2

Sales, general, and administrative.

2-4%

Inventory

management

Current

EBIT¹ margin

Back-oce

automation

Labor

headwinds

In-store labor

automation and

robotics

-2-3%

Customer

experience

Future EBIT

margin potential

0.5-1%

2-4%

1-2%

1-2% 5-9%

Increase of

3 to 5

percentage

points

Warehouse-

to-shelf

automation,

next-gen

cameras,

supply chain

optimization

Reduction in

shrink

by 20% from

advanced analytics

10% reduction

in store-

management

and SG&A²

costs

Use of in-store

assets to drive

sales (electronic

shelf tags,

consultative

selling tools)

20% increase

in minimum

wages

and benets

increases

Each retailer will

decide what

portion of EBIT

to reinvest

into price/customer

9A transformation in store

to prepare their organizations for a technology-

enabled revolution in customer experience and

efficiency. Ask yourself how your organization is

doing:

— Do you understand the level of performance

your network will need to achieve over the

next decade?

— Have you identified the primary use cases for

technology-enabled improvements to efficiency

or customer experience?

— Are you already testing and piloting new

technologies in store or across the network?

— Do you have the capabilities to ramp up your use

of technology- and data-driven retail innovations?

In forthcoming articles, we’ll take a closer look at the

technologies that are shaping the store of the future,

and how they are set to transform retail P&L.

Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

Praveen Adhi and Andrew Davis are partners in McKinsey’s Chicago office, where Gerry Hough is a senior expert, and

Shruti Lal is an associate partner; Tiffany Burns is a partner in the Atlanta office, where Bill Mutell is an associate partner;

Sebastien Calais is an associate partner in the Paris office.

STORE OPERATIONS

10 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

Smarter schedules,

better budgets: How to

improve store operations

Through activity–based labor scheduling and budgeting, retailers

can become more efficient while improving customer service and

employee satisfaction.

© Maskot/Getty Images

by Sebastien Calais, Andrew Davis, Daniel Läubli, and Bill Mutell

11Smarter schedules, better budgets: How to improve store operations

Labor scheduling is an evergreen topic for retail

operators with tools, processes, and personnel

demands that are constantly changing. While these

changes bring new constraints and innovations

to a well-defined concept, the fundamentals remain.

Companies that have a clear understanding of

the fundamental building blocks of scheduling

have an advantage over peers in identifying and

operationalizing innovation into store operations.

The following article outlines the most critical

elements of labor scheduling that hold true in

virtually any context.

In recent years, retailers have taken steps to “lean

out” their processes and gain efficiencies—with

impressive results. Lean-retailing initiatives have

yielded as much as a 15 percent reduction in

retailers’ operating costs.¹ But with competition

intensifying and customers expecting ever-higher

service levels, many retailers are now looking for new

ways to further improve productivity and enhance

customer service.

One major area of opportunity is workforce

management: specifically labor scheduling and

budgeting. Because of the complexity inherent

in creating accurate staffing schedules and budgets

for a large number of stores, even sophisticated

retailers find substantial room for improvement in

this area.

Off-the-shelf software and solutions—although

useful for important tasks such as monitoring

employee attendance and managing payroll—

typically produce generic schedules that don’t take

into account store-specific factors and workload

fluctuations. The unfortunate results include high

labor costs, inconsistent customer service, and

dissatisfied customers.

If a retailer could better predict the number and

skill set of employees that each of its stores needs

every day (or, better, every hour) of the week, then

customers would get prompt sales assistance,

shelves would be replenished in a timely manner,

employees would be neither idle nor overworked,

and, in most stores, labor costs would go down.

That is already happening at a few leading retailers.

Chief operating officers have begun looking closely

at store activities and taking a more data-driven

approach to labor scheduling and budgeting. In doing

so, they have captured between 4 and 12 percent in

cost savings while also improving customer service—

for example, by shortening checkout queues or

having more staff available on the sales floor to assist

customers—and boosting employee satisfaction. This

level of impact has been achieved at several different

types of retailers, from large supermarket chains in

the United States and Europe to specialty retailers in

emerging markets.

A mismatch between supply and demand

Many retailers use workforce-management

software to generate a weekly staffing schedule

that is unique to each store. This schedule is usually

based on revenue forecasts—more employees

work during hours or days when sales are projected

to be the highest. Revenue is a sensible criterion

for scheduling, but it’s an insufficient one because

customers’ buying patterns (average basket size,

average purchase price per item, and more) can

vary by hour and by day. A European grocer found,

for example, that manned service counters, such

as deli and bakery counters, account for a much

higher share of revenues on weekends than they

do during the week. On weekends, therefore,

the required labor hours increase at a higher rate

than revenues.

Furthermore, most retailers don’t have a systematic

way to account for store-specific factors that

affect how long activities take—such as the distance

that an employee must walk to transport a pallet

from a delivery truck to the storeroom or how many

1

For more on lean retailing, see Stefan Görgens, Steffen Greubel, and Andreas Moosdorf, “How to mobilize 20,000 people,” December 2013,

McKinsey.com.

STORE OPERATIONS

12 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

elevators employees can use for bringing products

to the sales floor. The same activity can be much

more time consuming at one store than at another,

even if the two stores have equal revenues.

Just as staffing schedules rarely align with a

store’s true labor needs, labor budgets are also

often mismatched with a store’s current reality.

Many retailers decide on labor budgets in an

undifferentiated top-down manner: for example,

they mandate that each store’s labor costs must not

exceed a certain percent of sales. Store managers

can then negotiate adjustments based on their

intuition or experience. This simplistic approach

relies too heavily on store managers’ judgment; it

also unfairly penalizes some stores. For instance,

a store in which fresh produce contributes a

large fraction of sales will be at a disadvantage

because fresh produce takes more time and care to

replenish than packaged goods. We found that such

differences among stores can lead to labor-cost

differences of up to 30 percent even if the stores’

sales are equal. A seemingly equitable top-down

directive thus becomes inequitable in practice; some

stores can provide exceptional customer service

and a relaxed pace of work for employees, while

at other stores, stressed workers struggle to meet

their service-level targets.

Four prerequisites to an activity-based approach

To revolutionize their labor scheduling and

budgeting, innovative retailers aren’t simply

relying on off-the-shelf workforce-management

solutions. Instead they are taking an activity-based

approach—one that matches store employees’

working hours to a changing workload, which means

the right employees are working at the right times,

performing the right tasks, and spending the least

amount of time required for those tasks. Equally

important, such an approach helps retailers develop

accurate annual labor budgets for each store. An

activity-based approach can be immensely valuable,

particularly to retailers that employ 20 or more

people per store.

Companies have historically used activity-based

techniques (such as activity-value analysis) to

improve processes and reduce costs, but rarely

have such techniques been applied to labor

scheduling and budgeting. In our analysis of labor-

scheduling logic, we identified four prerequisites

for excellence using an activity-based approach:

— store-specific workload calculations, which

are informed estimates of how long it takes

to complete certain activities (for example,

replenishing one pallet) in a particular store,

taking into account predefined service and

process standards

— reliable forecasts of “volume drivers” (such

as revenues per department, per hour, and

product flows) for each store, based on

sophisticated regression models as well as

store-manager experience

— a flexible workforce—with a mix of full-time,

part-time, and temporary staff—that can adapt

to schedules that may change on a daily and

weekly basis

— robust performance-management processes

and systems, with clear productivity and

service-level targets, to ensure that all stores are

on board and comply with the plan

All four of these prerequisites can be challenging

for retailers. We’ve found, however, that the

first prerequisite—generating accurate workload

calculations—often proves to be the key

improvement lever.

How to calculate workloads accurately

The optimal workload calculations set an

expectation for best-practice performance while

13Smarter schedules, better budgets: How to improve store operations

also acknowledging each store’s unique context. In

activity-based scheduling, the time allotted to each

activity is a network-wide standard time that is the

same for all stores, plus any additional time due to the

specifics of each store (exhibit). The network-wide

standard time in effect establishes a best-practice

benchmark for all stores. Store–specific time drivers

can then be measured by observation.

Some activities will be tricky to model. For

instance, figuring out how long it should take to

ring up purchases at checkout and how many

cashiers should be working at any one time isn’t a

straightforward calculation—customers arrive at

checkouts randomly. For unpredictable customer-

facing activities like these, retailers will need to use

queuing theory.²

Retailers should focus on activities that constitute

a significant amount of store employees’ workload.

On the one hand, developing a detailed model of

how long it takes to adjust a shelf to an updated

planogram isn’t necessary, as this activity typically

accounts for less than 1 percent of the total workload.

On the other hand, replenishment-related activities

can take up to 70 percent of the total work hours in a

store (see case study, “One retailer’s results: Lower

labor costs, better store managers”).

Implementation and rollout

Implementing an activity-based approach requires a

tool that can turn inputs (such as revenue forecasts

and customer-footfall estimates) into useful outputs

for store managers. Outputs might include the

required number of full-time employees per hour

and per day, the specific tasks employees should

be doing during certain hours of the day, and the

associated labor costs.

Retailers typically find it easier and faster to build

such a tool from scratch and then inject its outputs

into their existing workforce-management systems,

rather than build the tool within their current HR

systems. In our experience, it takes approximately

six months to develop an Excel-based prototype,

pilot it in a handful of stores to test the accuracy of

all assumptions and workload calculations, observe

its impact on the workforce, and refine it.

How quickly the tool is rolled out to the entire store

network will depend on available resources, but

a store-by-store rollout—whereby an operations

“coach” helps store employees learn about the new

tool and any new processes—is often most effective.

Leadership must ensure that the tool is embedded

into daily work and fully linked to HR planning and

annual budgeting processes. To keep it constantly

Exhibit

2

Queuing theory is useful for calculating how many employees are needed at a given time to meet the retailer’s target service level. In the

checkout example, the target could be based on waiting time (for instance, 90 percent of customers will wait in a checkout line for no more than

three minutes) or queue length (for instance, 90 percent of customers will have a maximum of two people in front of them at checkout).

McKinsey on Retail 2020

Smarter schedules

Exhibit 1 of 1

Stores should be allotted the same amount of time for the same task, with some adjustments

based on each store’s unique context.

Time for activity Standard time Store–specic time driver Quantity

Total time for store

employees to

perform a core activity

in a department

Target time for an activity;

should be the same for entire

store network

Additional time needed due

to local store characteristics

(eg, store layout, average

basket size)

Number of times the activity is

performed; variable (can be

derived from historical data)

STORE OPERATIONS

14 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

up to date and relevant, retailers should consider

setting up a scheduling team of people who have the

requisite analytical skills and who are familiar with

store operations. The team would be responsible for

maintaining and updating the tool and adjusting the

workload calculations to new processes.

An activity-based approach can reveal opportunities

for improving store processes. In fact, it can serve

as the backbone for a continuous-improvement

program; ideally, the new scheduling and budgeting

tool would be able to run “what if” analyses for any

changes in service levels or process standards. And in

the event that labor budget cuts become necessary,

management teams—instead of just imposing top-

down percentage cuts—will be equipped to lead

practical and detailed discussions about which store

activities could be speeded up or eliminated entirely,

or where service-level targets could be relaxed.

In this way, they will be able to ensure sustained

improvements in store productivity, customer service,

and employee satisfaction, all while keeping labor

costs firmly under control. In future publications, we

will outline some of the unique elements that can

drive variation in labor scheduling.

One retailer’s results: Lower labor costs, better store managers

Case study

A large European retailer, with annual

revenue in excess of $20 billion, knew that

its stores’ labor scheduling and budgeting

processes weren’t rigorous enough.

At every store, both the standard weekly

stang schedule and the annual labor

budget were based primarily on revenues

and managerial judgment.

Seeking a more data-driven approach, the

retailer decided to pilot activity-based

labor scheduling and budgeting in two of

its stores over a four-month period. The

eort involved calculating the timing of

65 activities and building an Excel-based

prototype of a new labor-scheduling and

budgeting tool.

The retailer subsequently tested the

prototype in six additional stores that were

quite dierent from one another to ensure

that the tool’s outputs would be relevant

to the entire store network. Along the

way, the retailer discovered and quickly

implemented a number of best practices

and process improvements.

The new stang schedules and labor

budgets yielded an eciency improvement

along with an improvement in customer

service—gratifying results, particularly

in light of the fact that the retailer had

recently undertaken a successful lean-

retailing transformation and in many

ways already had best–practice store

operations. Furthermore, the approach

helped expose poor store management.

For example, one store was perceived

in the company as being well managed

because it had notably low labor costs.

But bottom-up calculation of the store’s

annual labor budgets showed that the low

labor costs were entirely due to favorable

store specics, such as short distances

for transporting products and shelves that

were relatively easy to stock. Once labor

costs were adjusted for those specics,

the store was shown to be among the least

ecient in the network. These and similar

insights allowed the retailer to better

evaluate and train its store managers.

Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

Sebastien Calais is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Paris office, Andrew Davis is a partner in the Chicago office,

Daniel Läubli is a partner in the Zurich office, and Bill Mutell is an associate partner in the Atlanta office.

15Smarter schedules, better budgets: How to improve store operations

Bending the cost

curve in brick-and-

mortar retail

Retailers can achieve next-generation store efficiency by breaking

down silos and optimizing total cost across the value chain.

© Noel Hendrickson/Getty Images

by Praveen Adhi, Vishwa Chandra, Karl-Hendrik Magnus, and Aneliya Valkova

STORE OPERATIONS

16 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

Making money in retail—particularly in physical

stores—is becoming harder and more complex

each year. Many retailers around the globe have

addressed many of the possible efficiencies in

labor productivity and process automation. It is

time to consider the next generation of thinking to

make a meaningful difference in brick-and-mortar

economics and remain competitive in an ever-

changing retail environment.

Our colleagues have discussed how an integrated

view on cost can help consumer-goods companies

optimize operations costs across the value chain.¹

In this article, we take a closer look at how retailers

can benefit from a similar end-to-end perspective.

The goal is to help traditionally siloed departments,

from store operations to supply chain to merchan-

dising, understand the total cost of each SKU by

disaggregating the product’s journey from end to

end. This understanding can enable retailers to make

better decisions about what products to purchase,

when to transport them, how to display them, whether

to offer a sale—and, all along, how to make best use

of their employees’ time.

While traditional store efficiency programs

focused on in-store labor productivity can save

5 to 10 percent in overall costs, in our experience

a more comprehensive cost approach can enable

retailers to realize two to three times more savings,

bending the cost curve more toward meaningful

impact than the traditional incremental approach.

Case for change: External environment

Even retailers with stable balance sheets face

mounting cost pressure due to several factors,

including decreased foot traffic, increased SKU

complexity, higher customer expectations, and

rising labor costs.

To start, consumers shop from the comfort of

their couches rather than traveling to the nearest

shopping center; e-commerce has accounted

for 40 percent of retail growth in the United States

since 2016. A recent McKinsey survey found that

82 percent of US consumers reported spending

money online over the preceding three months,

and 42 percent of millennials report they prefer

shopping online to shopping in store.² Still, the

in-store experience is far from obsolete. McKinsey

projects e-commerce will constitute just 21 percent

of total retail sales and 5 percent of grocery sales

by 2023.

Second, brick-and-mortar stores are contending

with increasing SKU complexity; in a world of ever-

shorter product cycles and rapid innovation, SKUs

have proliferated rapidly.

Third, stores are facing increased customer service

and experience expectations, requiring both more

time dedicated to customers and better-trained

frontline staff to serve today’s highly digital, well-

informed customer. In addition, the proliferation

of omnichannel experiences is changing the

very purpose of a physical store.³ Stores are

increasingly expected to offer a variety of omni-

channel services, including in-store fulfillment and

returns of online orders.

Finally, retailers’ traditional labor pool is dwindling

due to low unemployment and rising labor costs.

For example, the United States is experiencing

record-low unemployment.⁴ And to date, states

that account for 30 percent of US workers have

committed to phasing in a minimum wage increase

that will ultimately reach $15 an hour—more than

double the federally mandated wage of $7.25.⁵

What retailers can do

To remain viable in this environment, retailers

must constantly improve their store economics

by simplifying, eliminating, or automating routine

activities. Most retailers have implemented several

rounds of lean cost-improvement programs, such

as automating simple activities (reporting and

1

Philip Christiani, Sebastian Gatzer, Daniel Rexhausen, and Andreas Seyfert, “How to untap the full potential: An integrated—not isolated—view

on cost,” September 2019, McKinsey.com.

2

Praveen Adhi, Tiffany Burns, Andrew Davis, Shruti Lal, and Bill Mutell, “A transformation in store,” May 2019, McKinsey.com.

3

Raj Kumar, Tim Lange, and Patrik Silén, “Building omnichannel excellence,” April 2017, McKinsey.com.

4

“Employment situation summary,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, October 4, 2019, bls.gov.

5

Chris Marr, “States with $15 minimum wage laws doubled this year,” Bloomberg Law, May 23, 2019, bloomberglaw.com.

17Bending the cost curve in brick-and-mortar retail

scheduling) and streamlining their inventory stocking

processes. However, most still take a narrow view

of what costs they can optimize, focusing on activities

the store can influence and accepting upstream

activities and decisions as constraints.

To reach the next level of cost efficiency, retailers

must expand their focus outside the four walls of the

store. Only the most advanced look for efficiency at

the intersection of store operations, merchandising,

supply chain, and transportation to adopt a total-cost

view—that is, the sum of cost components across

the value chain (Exhibit 1). By considering underlying

costs, from how products are chosen to how they’re

stocked, in our experience retailers can expand the

scope beyond costs addressed in their brick-and-

mortar stores by 50 percent. These underlying costs

are also more likely to yield efficiency because they

have not been scrutinized as much as in-store costs.

A total cost approach can reveal a host of

unrealized efficiencies (Exhibit 2). For example,

with input from store operations, merchandising

can adjust the store’s promotional calendar by

category and product to incorporate both the

expected incremental margin as well as the

store labor required to change price tags and

build promotional displays. Given this more

comprehensive view of cost, some promotional

activities will be seen as unprofitable and thus

discontinued. Further, a deeper understanding of

net margin and labor implications in distribution

centers and stores can inform decisions about

whether to add or remove shelf space from a given

SKU. The extra labor cost required to stock the

shelf between less frequent deliveries may be

offset by transportation cost savings.

A comprehensive view of cost can also inform

investments into enhanced capabilities such as

automation. For example, if a distribution center can

be outfitted to build custom pallets that match a

store’s layout, frontline staff would spend less time

sorting products and moving between aisles.

It is important to recognize that these efficiencies

will lower costs in some departments but

may be cost-neutral or increase costs in others;

accounting for these cross-functional effects

will be critical to success.

Success factors for bending the

cost curve

Four primary factors are crucial to bending the cost

curve through a total-cost approach: governance

and executive alignment, cost transparency, data and

analytics capabilities, and key performance indicators

(KPIs) and incentive alignment.

To remain viable in this

environment, retailers must constantly

improve their store economics by

simplifying, eliminating, or automating

routine activities.

STORE OPERATIONS

18 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

Exhibit 1

Cross-functional collaboration to understand total cost of handling can lead to a host of

unrealized eciencies.

Store operations

The store receives less frequent deliveries

to optimize transportation cost—the

savings outweigh the extra labor needed

to manage bigger shipments.

The business case on whether to invest

in distribution-center automation is

amended to include store savings from

stocking product that arrives in better-

organized pallets.

Promotional displays are built upstream in

the distribution center or at the vendor,

reducing the time it takes store employees

to set up.

Supply chain Merchandising

Cost decrease

Neutral

Cost increase/

margin decrease

SO SC

SC

M

SO

M

SC

SO

M

SO

M

SC

SO SC

M

SC

SO

M

SC

SO

M

Category and product promotional

protability is adjusted to account for

store labor costs to replace price tags and

build promo displays. This makes some

promotions unprotable, and they are

discontinued.

Extra shelf space is added for fast-moving

SKU A to enable stocking all product at

once. The store labor savings are greater

than the lost margin from removing SKU

B’s shelf space.

Product is purchased from vendors,

shipped, and stocked in shelf-ready

packaging, which makes it easier for

stores to handle and outweighs the extra

vendor costs.

19Bending the cost curve in brick-and-mortar retail

Exhibit 2

Governance and executive alignment

It starts from the top. Senior-level, cross-functional

alignment and sponsorship are required to

communicate change and ensure it sticks. Given the

sensitive nature of cross-functional savings—some

departments will see a cost increase, while others will

see a disproportionate cost decrease—each function

needs to be confident that senior leaders support

them and that every function adheres to the same

new standards.

In addition, the business owner of this new process

should be selected with care. Ideally, they should

reside outside of functions that own a meaningful

number of cost components; finance is often a good

option because it lacks a direct stake in where costs

are incurred. Store operations is another viable

option, as it is furthest downstream in the process.

Cost transparency

Retailers often struggle to calculate their total cost

of handling for two simple reasons: they either lack

a full understanding of cost components or don’t

have the data to quantify each. For example, many

retailers do not have a clear sense of how much

labor is used per unit of product in the store, starting

with unloading it from a truck to placing it on the

shelf, refilling the shelf between deliveries, checking

for out-dates, mounting promotions, and beyond.

Each SKU’s journey should be mapped and

broken down into cost-component steps. Each

step includes multiple iterations based on how it

is executed. For example, in–store labor cost is a

component with at least two iterations based on

how a product is stocked—as a full case or individual

units. Identifying where a product goes and stocking

The total cost of handling a product is determined by considering cost at each step of the

value chain.

Review category

Example

decisions

Impacted cost

components

Create planogram Plan demand

New SKUs to

introduce

Number of stores

for new SKU

introduction

Number of facings

Shelf depth

Space for category

Safety stock

Minimum

presentation

quantity

Location in the

distribution center

for new SKU

Mode of shipping

to the store (case

or individual)

Frequency of

store delivery

Store processes

for stocking

Placement of

overstock (eg,

back room vs top

shelf vs elsewhere)

Cost of goods sold,

write-os, shrink

Store labor cost to

replenish between

shipments based

on shelf capacity

Distribution center

picking cost based

on amount of

product shipped

Inventory holding

cost of safety

stock and minimum

presentation

Store labor cost from

stocking full cases

vs individual units

Store labor cost

to stock product

on shelves and

return overstock

to back room

Introduce to

distribution center

and prepare to ship

Receive and stock

STORE OPERATIONS

20 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

a full case all at once requires much less labor per

unit compared with stocking individual units and

searching for the correct spot on the shelf after each

one. These cost estimates should be periodically

refined to reflect changes in cost structure.

Data and analytics capabilities

Establishing cost transparency should result in the

creation of a central data repository with access to

multiple sources of data at the SKU and store levels,

including all cost components across sales, cost,

margin, safety stock and presentation requirements,

promotional calendar, planogram versions, and

shipping quantities. Typically, these data sources are

not tied to each other, requiring additional work to

build a 360-degree view of each SKU.

Once the data are assembled, sophisticated data

and analytics capabilities are needed to simulate the

different scenarios based on variable factors—such

as how a product is shipped from the distribution

center, in what quantity, and how often. An advanced

decision-engine algorithm needs to be put in place

to determine the lowest-cost path through the

system and estimate the cost savings should all SKUs

follow the optimal path. Identifying the scenario that

matches the current state and comparing it to the

optimal state can illuminate the concrete savings

gained by moving from the traditional to the proposed

approach. Savings can be realized both initially, when

the decision engine is put in place, and continuously

as the algorithm becomes embedded.

Key performance indicators and

incentive alignment

While advanced analytics can enable decisions that

optimize total cost across the organization, some

areas of the organization may experience relative

cost increases that permit bigger decreases in other

areas. However, many parts of the organization

have narrow P&Ls that don’t account for cross-

functional effects. As such, end-to-end costs must

be embedded in the reporting and KPIs of each

function. For example, a merchandising decision to

remove shelf space from the planogram of a fast-

moving SKU should consider more than the lost

margin and vendor funding. The decision should

also consider whether less shelf space may negate

the benefit of shipping full cases to the store. In that

case, the SKU in that planogram will incur the extra

cost from being shipped as individual units from the

distribution center and the additional cost of having

to be restocked between shipments if its shelf

capacity is decreased.

Brick-and-mortar retail will continue being

challenged to deliver on multiple fronts at once,

including customer experience, omnichannel

services, and cost excellence. While initially impactful,

traditional lean levers employed by store operations

limit the scope of opportunity by ignoring 50 percent

of cost controlled by other functions, including

merchandising and supply chain. To bend the cost

curve and reach performance excellence, retailers

should take an end-to-end view of cost. With a

data–driven decision engine and senior leadership’s

support, retailers can realize significant opportunity

across the organization and make better long-term

operating decisions.

Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

Praveen Adhi is a partner in McKinsey’s Chicago office, where Aneliya Valkova is an associate partner; Vishwa Chandra is a

partner in the San Francisco office; Karl-Hendrik Magnus is a partner in the Frankfurt office.

21Bending the cost curve in brick-and-mortar retail

Supply chain of the

future: Key principles in

building an omnichannel

distribution network

As omnichannel shopping is becoming the new norm, consumer and

retail companies must be ready to deliver fast, impeccable omnichannel

service. Doing so requires a new supply chain network approach.

© NicoElNino/Getty Images

by Manik Aryapadi, Ashutosh Dekhne, Wolfgang Fleischer, Claudia Graf, and Tim Lange

SUPPLY CHAIN

22 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

The consumer product and retail landscape

continues to evolve as companies race to catch up

with leading e-tailers. Traditional brick-and-mortar

retailers such as Macy’s, Nordstrom, and Walmart are

expanding their online offerings and introducing new

models, such as in-store fulfillment of online orders.

Online players such as Amazon and Zalando are

opening their own brick-and-mortar stores. Vertically

integrated players such as Bose, Burberry, and

Nike are strongly pushing their direct-to-consumer

business through both online and new physical

stores. And players of all kinds are complementing

their physical stores and e-commerce offerings with

innovative applications and social media to mount a

truly omnichannel presence.

However, many players still struggle with

omnichannel success given the requirements it

places on their supply chains—especially in terms

of speed, complexity, and efficiency. Customers

expect to receive their products anytime and

anywhere with a very short time between order

and delivery, with excellent service and high

convenience. Our research shows that service

represents the primary factor that brands and

retailers can use to differentiate themselves and

“delight” omnichannel shoppers.¹

Companies that succeed, in our experience, master

seven key building blocks of the omnichannel

supply chain (see sidebar, “The seven supply chain

building blocks for omnichannel excellence”). In

this article, we focus on building block number

two, the network and ecosystem of the future, and

describe the principles that can guide companies’

approach to omnichannel network design in an

increasingly complex environment.

The current e-commerce landscape

While apparel trails industries such as electronics

and sporting goods in e-commerce penetration, the

number of people shopping for clothes and shoes

online is rising rapidly. This trend is true across

regions. From 2014 to 2017, online apparel purchases

grew at a CAGR of 24, 15, and 14 percent in Southern

Europe, North and Western Europe, and Central

Europe, respectively. In the United States, online

apparel sales grew 18.5 percent in 2018 alone,

to more than one-third of all apparel sales that year.²

This growth far outpaced total apparel sales

growth of 5.3 percent that same year. In China, total

online retail spending grew 27 percent in 2018,

with 24 percent of retail sales taking place online.³

Companies of all kinds, not only in apparel, are

racing to meet customer needs—and adapting their

supply chain is often one of the primary hurdles.

Traditional supply chain networks are often not

built for same-day delivery with excellent service.

This is an issue especially when fierce competition

offers shorter delivery times with a great customer

experience; for example, Amazon continuously

redefines delivery standards.

1

Holly Briedis, Tyler Harris, Megan Pacchia, and Kelly Ungerman, “Ready to ‘where’: Getting sharp on apparel omnichannel excellence,” August

2019, McKinsey.com.

2

April Berthene, “Ecommerce is more than a third of all apparel sales,” Digital Commerce 360, July 23, 2019, digitalcommerce360.com.

3

Satish Meena et al., “Forrester Analytics: Online retail forecast, 2018 To 2023 (Asia Pacific),” Forrester, May 15, 2019, forrester.com.

Traditional supply chain networks are

often not built for same-day delivery

with excellent service.

23Supply chain of the future: Key principles in building an omnichannel distribution network

The seven supply chain building blocks for omnichannel excellence

The omnichannel supply chain of the

future has seven key elements that

combine best practices with digital

opportunities (exhibit).

Companies that achieve omnichannel

success master seven key building blocks.

The essential questions to ask for each

element are listed below.

Exhibit

McKinsey on Retail 2019

Distribution network design

Exhibit 1 of 2

The omnichannel supply chain of the future has seven key elements that combine best

practices with digital innovation.

Network and ecosystem of

the future

The supply chain’s backbone—

provides required speed and

exibility, leveraging information,

and partner assets and

capabilities.

E2E planning and information

ow

Key information ow capabilities

that access the right products in

the right place at the right time—

real-time—to deliver according to

customer expectations

Operating model and change

management

Key organizational enabler for the

company and its people—captures

supply chain potential and delivers

exceptional customer value.

Omnichannel fulllment: Node

operations

Key physical ow capabilities that

ensure competitive cost

structures and reliable quality

while managing complexity.

Digitization and process

automation

Key technology enabler that uses

available omnichannel data,

analytics, and supply chain

systems along the end-to-end

value chain—and includes

ecosystem partners.

Omnichannel fulllment:

Transportation and LSP

management

Key physical ow capabilities that

provide reliable, fast service to

all customers where it matters,

while ensuring competitive

transport costs.

Customer–centric supply chain strategy

Starting point to design an omnichannel

supply chain that meets customer needs

along all channels.

SUPPLY CHAIN

Customer–centric supply chain strategy

— Supply chain strategy and

segmentation: How many supply

chain segments are required to deliver

the supply chain mission? What is

the objective of each supply chain

segment—responsiveness versus

efficiency?

— Customer–backed service aspirations:

What is the customer offering across

different segments? Where does speed

matter versus flexibility and services?

How can we differentiate ourselves

from competitors?

— Assortment and complexity

management: How can we tailor the

assortment to a retailer or to a channel

(for example, online only)? How is the

product portfolio managed?

— Risk management: What are the key

supply chain risks? How can we best

prepare for supply chain disruptions?

What are the best proactive mitigation

strategies and contingency plans?

— Sustainability: How can we create a

sustainable supply chain using best

practices, such as supporting the

circular economy and using sustainable

raw materials and packaging?

Network and ecosystem of the future

— Supply network: What is the physical

flow of goods through the network?

What are the different product–supply

speed models, and what is the impact on

the supplier and production footprint?

24 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

The seven supply chain building blocks for omnichannel excellence (continued)

— Supplier management and

collaboration: How are suppliers

managed and integrated to support

an agile upstream supply chain that

responds quickly to changes, as

required by the omnichannel customer?

— Distribution network: Is the distribution

network designed for each channel

individually or is an omnichannel

network beneficial?

What is the right composition of

distribution centers (DCs), new node

types, and partner locations?

— Inventory-sharing concepts: How

can inventory be shared across

channels? Does each channel have

its own inventory? What is the best

governance and business model for

these concepts?

— Customer collaboration: What are key

areas for customer collaboration that

could improve information exchange

and product flow along the value chain?

Where should partners be employed to

drive and access innovation?

End-to-end (E2E) planning and

information ow

— Demand planning: What are the

different demand signals in the

omnichannel environment, and how can

they be captured to predict demand

potential by leveraging advanced

analytics? How can we combine them

into an E2E marketplace perspective?

— Inventory management: What is the

optimal inventory level at each stage of

the value chain—DCs, stores, partners,

etc.? How can we actively manage

inventory to increase availability and

keep cash requirements under control?

— Supply and replenishment planning:

How can we best synchronize the

product supply with customer demand

in stores, DCs, and with partners?

Ensure the right amount of capacity

along the different segments of the SC?

— Sales and operations control tower:

How can we align the different

organizational entities and plans at

key milestones? Manage and decide

on trade-offs? Allocate and prioritize

customers, channels, and orders in

case of constraint?

— Distributed order management: How

can we ensure real-time visibility and

accessibility of inventory across all

channels and locations? Find and

access the right fulfillment node to

fulfill customer orders efficiently?

Omnichannel fulllment: Node

operations

— Warehouse management: How can

we achieve warehouse excellence in a

more complex environment? Leverage

automation to increase speed, quality,

and efficiency? Should DCs be

operated in house or outsourced?

— Return flows and processing: How can

we manage returns in an efficient and

effective way? Optimize return flows

across the network? Which decisions

on flow of goods can be made by which

parts of the value chain?

— In-store operations: How can we enable

the whole downstream supply chain

for omnichannel? Optimize in-store

layout and processes to enable local

fulfillment while securing a great

customer experience?

Omnichannel fulllment: Transportation

and logistics service provider (LSP)

management

— Transport management: What is

needed to manage transport operations

efficiently in an increasingly demanding

world? How do we keep transport cost

under control? Create end-to-end

transparency of product flows?

— Logistics service provider sourcing

and management: What are the right

logistics partners for the different

supply chain segments? How do we

best source and manage LSPs to get

competitive rates and services?

Operating model and change

management

— Processes: How do we design supply

chain processes to support omnichannel

optimization? How can digital innovation

be integrated in the process design?

How do we accelerate decisions?

— Structures: How can we adjust the

organizational structure to capture

cross-channel benefits and make

change happen? Avoid silos between

channels? Use zero-based thinking in

organizational sizing?

— Capabilities and mind-set: Which

additional skills are needed to enable

the future organization? Where

should an agile way of working be

used and how? How can we best

address the cultural change toward

omnichannel behavior?

— Performance management: How

should performance of the E2E

supply chain be measured? How

can we incorporate the omnichannel

dimension, measuring the joint

performance rather than individual

channels? Adjust incentives to enable

the right behavior?

25Supply chain of the future: Key principles in building an omnichannel distribution network

The seven supply chain building blocks for omnichannel excellence (continued)

Digitization and process automation

— Foundational software: What is the

required software and tooling needed

to enable the omnichannel supply

chain? Which optimization decisions

need special tool enablement?

— Data strategy: How can we capture

data and use it along the value chain?

Build the omnichannel data lake to

link the data from different platforms

and systems? How are legacy systems

integrated? How do we integrate into

an ecosystem with our partners?

— Analytics strategy: How can we

contextualize data to conduct

relevant analyses? Is operational data

consolidated and accessible by the right

decision makers? How can we best

visualize data and analytics to make

them accessible to decision makers?

— Process automation: How can

advanced digital tools such as robotic

process automation, blockchain, and

the Internet of Things be deployed?

What are the key benefits of these

technologies, and how can they enable

omnichannel optimization?

In addition, e-commerce fulfillment is much more

complex than traditional brick-and-mortar or

wholesaler fulfillment. When customers can order

24/7, demand is less predictable and more difficult

to shape. Order sizes are significantly lower, and

the number of products offered continuously rises.

The increase in speed and complexity drives up

fulfillment costs. In our experience, an online order’s

cost per unit can easily be four to five times higher

than traditional brick-and-mortar replenishment

and ten times higher than wholesale fulfillment. All

the while, customers demand a seamless

omnichannel journey.

Building out the omnichannel experience can bring

huge value for retailers, e-tailers, and vertically

integrated players with direct-to-consumer

business; our research has found that customers

shopping online tend to buy more, and customers

that pick up online orders in store often make

additional in store purchases. With the seven

building blocks of a successful omnichannel supply

chain in mind, the following principles should be

top of mind while working to build the network and

ecosystem of the future.

Put the customer’s needs first

To start, companies need to adopt a granular

perspective of what the customer really wants, today

and in the future. This understanding will inform

which channels to serve, which products and services

to offer, and where to offer them. For example, a

young adult living in a large city, such as London

or New York City, wants to purchase and receive a

newly launched sneaker that a celebrity presented

on Instagram that same day. However, the customer

does not know where she will be in a few hours, so it is

important that she can track the delivery and reroute

it at any time. If, for example, she goes to a café, the

shoes are rerouted (via an app) to be delivered there.

Developing this detailed understanding of

customers requires harnessing customer data. This

information should be combined with customer-

behavior insights culled from customer interviews,

observations, and the latest research from market

experts, as well as analyses of competitors’

e-commerce offerings. Advanced analytics can be

used to process all this information and gain a clear

understanding of customer expectations.

4

“Employment situation summary,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, October 4, 2019, bls.gov.

SUPPLY CHAIN

26 Future of retail operations: Winning in a digital era January 2020

In addition to understanding the customer today,

companies must also look to the future and

stay flexible as the market rapidly changes. For

example, while next-day service was novel just

a few years ago, it is common today. How future

incumbents and disrupters will shape the market

is still unknown. As such, serving the customer of

the future requires unprecedented agility—quickly

adapting to changing customer expectations.

Forget one size fits all

A deep understanding of customer desires should

be the foundation of defining the strategy and

building various customer segments based on

preferences, product categories, and locations.

This segmentation recognizes that a one-size-fits-

all approach is a waste of resources. A segmented

approach enables the company to prioritize specific

services for each customer group—for example,

which speed of delivery to offer for each segment and

which differentiated services to offer or not. While

the London customer may expect same-hour service,

customers living in remote areas might not mind

waiting a few days. Developing this understanding

to undergird the strategy is crucial to avoid common

mistakes, such as offering convenience at a premium

to customers that care more about price or building

offerings that quickly become outdated.

Be fast and collaborative

In the traditional supply chain model, companies

often choose a purely quantitative approach to

model the perfect fulfillment network needed for

the service offering. This generally involves a rather

rigid and time-consuming approach: three months

of data collection, six months of modeling, and three

months of decision making before implementation.

This traditional approach leads to a onetime strategy

and long implementation times. However, in an

ever-volatile environment with constantly changing

customer needs, evolving partnerships, and newly

developing competition, reacting quickly is critical to

ensure that the supply chain network is responsive,

flexible, and efficient.

Therefore, companies should remain agile in their

thinking and assemble a cross-functional team.

One best practice is to develop the future supply

chain network in a workshop-based environment.

In practice, this means determining the fulfillment

options suitable for each customer, product, and

location segment and defining the required

product flow. Starting with the segment that has

the most demanding lead time, the best fulfilment

option needs to be found for each segment while

considering operational needs, such as costs to serve

and volume constraints. Once a solution for each

segment in each location is defined, it must all be

combined into one comprehensive service network.

Seek partnerships and share resources

In an ever-volatile environment, speed of

implementation and efficient use of resources are

crucial. Therefore, it is necessary to take advantage

of existing infrastructure, such as warehouses and

retail stores, as well as resources available in the

In an ever-volatile environment, speed

of implementation and ecient use of

resources are crucial.

5

Raj Kumar, Tim Lange, and Patrik Silén, “Building omnichannel excellence,” April 2017, McKinsey.com.

27Supply chain of the future: Key principles in building an omnichannel distribution network

market. Leading companies are actively seeking

partnerships, not only along their own value chain

but also with players from other industries. Sharing

infrastructure brings synergies—costs and risk are

split, for example—and enables better customer

service and faster delivery times. For instance, a

player operating department stores may offer

in-store pickup services to e-commerce companies,

and e-commerce companies can offer online order

fulfillment to department stores. The partners would

establish commercial terms for compensation,

such as sharing the margin. Connected inventory is