DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

W ASH I N G T O N , D . C .

February 15, 2024

A Message from the Secretary of the Treasury

During fiscal year 2023, the American economy continued to improve and the gains have been widely

shared: consumers have more purchasing power, businesses have been investing more, and inflation has

come down significantly. The labor market is also strong, with the unemployment rate near historic lows.

This is the result of a historically fast recovery, as well as actions to navigate adverse shocks. Over the past

year, the Biden Administration acted decisively in response to stress in the banking sector to protect

depositors and mitigate systemic risks to the financial system. The Administration continues to vigilantly

monitor potential economic spillovers from global events, including Russia’s war in Ukraine and the

conflict in the Middle East.

The Biden Administration also remains focused on growing our economy for the medium to long term. This

year, Americans are starting to see the results of the historic legislation passed in 2021 and 2022:

the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act. Public

dollars are now crowding in private investment, with companies announcing over $600 billion in clean

energy and manufacturing investments since the start of the Biden Administration and new jobs being

created in twenty-first century industries.

To further the government’s commitment to financial transparency and accountability, the annual Financial

Report of the United States Government lays out comprehensive data and analysis on our nation’s finances.

Here, you will find information on all aspects of the government’s current financial position, as well as

information on changes in the financial position during this fiscal year, and potential future changes.

It is my duty and pleasure to present the Fiscal Year 2023 Report to the American people.

This page is intentionally blank.

Contents

A Message from the Secretary of the Treasury

Executive Summary...........................................................................................

1

Management’s Discussion and Analysis ..........................................................

12

Statement of the Comptroller General of the United States ..........................

40

Financial Statements

Introduction .......................................................................................................

50

Statement of Net Cost ........................................................................................

57

Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position ......................................

59

Reconciliations of Net Operating Cost and Budget Deficit ...............................

61

Statements of Changes in Cash Balance from Budget and Other

Activities ...........................................................................................................

62

Balance Sheets ...................................................................................................

63

Statements of Long-Term Fiscal Projections.....................................................

64

Statements of Social Insurance ..........................................................................

65

Statement of Changes in Social Insurance Amounts .........................................

68

Notes to the Financial Statements

Note 1. Summary of Significant Accounting Policies .......................................

70

Note 2. Cash and Other Monetary Assets ..........................................................

82

Note 3. Accounts Receivable, Net .....................................................................

83

Note 4. Loans Receivable, Net and Loan Guarantee Liabilities ........................

84

Note 5. Inventory and Related Property, Net ....................................................

88

Note 6. General Property, Plant, and Equipment, Net .......................................

90

Note 7. Investments ...........................................................................................

91

Note 8. Investments in Government-Sponsored Enterprises .............................

95

Note 9. Advances and Prepayments ..................................................................

99

Note 10. Other Assets ........................................................................................

100

Note 11. Accounts Payable ................................................................................

102

Note 12. Federal Debt and Interest Payable ......................................................

103

Note 13. Federal Employee and Veteran Benefits Payable ...............................

106

Note 14. Environmental and Disposal Liabilities ..............................................

116

Note 15. Benefits Due and Payable ...................................................................

118

Note 16. Insurance and Guarantee Program Liabilities .....................................

119

Note 17. Advances from Others and Deferred Revenue....................................

120

Note 18. Other Liabilities ..................................................................................

121

Note 19. Collections and Refunds of Federal Revenue .....................................

123

Note 20. Commitments ......................................................................................

126

Note 21. Contingencies .....................................................................................

129

Note 22. Funds from Dedicated Collections ......................................................

136

Note 23. Fiduciary Activities.............................................................................

142

Note 24. Long-Term Fiscal Projections.............................................................

144

Note 25. Social Insurance ..................................................................................

150

Note 26. Stewardship Property, Plant, and Equipment ......................................

159

Note 27. Disclosure Entities and Related Parties ..............................................

160

Note 28. Public-Private Partnerships .................................................................

166

Note 29. COVID-19 Activity ............................................................................

167

Note 30. Subsequent Events .............................................................................

168

Required Supplementary Information (Unaudited)

The Sustainability of Fiscal Policy ....................................................................

170

Social Insurance ................................................................................................

181

Social Security and Medicare ..........................................................................

181

Railroad Retirement, Black Lung, and Unemployment Insurance ..................

195

Deferred Maintenance and Repairs ...................................................................

197

Other Claims for Refunds ..................................................................................

197

Tax Assessments ...............................................................................................

198

Federal Oil and Gas Resources ..........................................................................

198

Federal Natural Resources Other than Oil and Gas ...........................................

200

Land and Permanent Land Rights .....................................................................

201

Other Information (Unaudited)

Tax Burden ........................................................................................................

204

Tax Gap .............................................................................................................

205

Tax Expenditures ...............................................................................................

205

Unmatched Transactions and Balances .............................................................

207

Appendices

Appendix A: Reporting Entity ...........................................................................

208

Appendix B: Glossary of Acronyms..................................................................

212

U.S. Government Accountability Office Independent Auditor’s Report......

218

For a complete listing of frequently used acronyms found

throughout the Financial Report, please refer to the Glossary

of Acronyms located in Appendix B.

This page is intentionally blank.

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

2

Executive Summary to the FY 2023

Financial Report of the United States Government

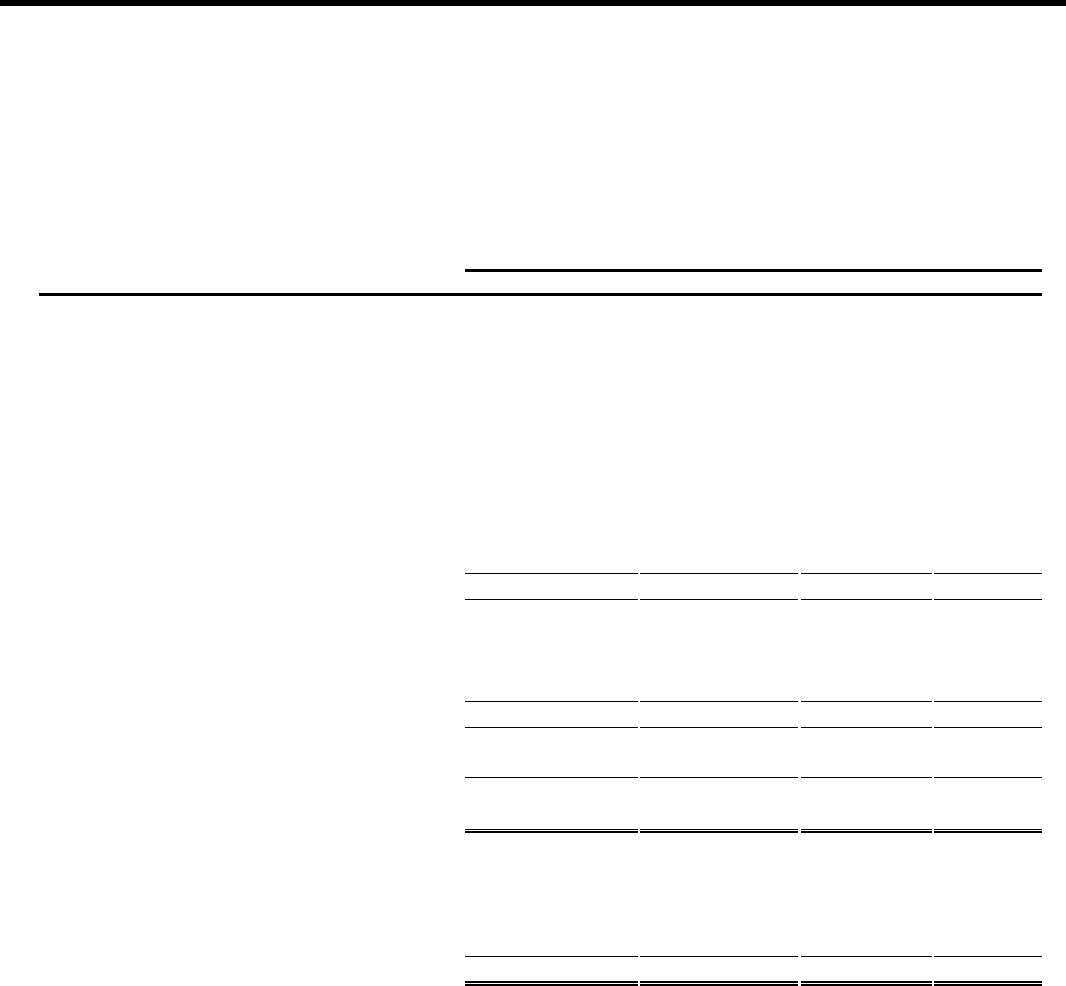

The FY 2023 Financial Report presents the U.S. government’s current financial position and condition, and

discusses key financial topics and trends. The Financial Report is produced by Treasury in coordination with

OMB, which is part of the Executive Office of the President. The table on the preceding page presents several key

indicators of the government’s financial position and condition, which are discussed in this Executive Summary

and, in greater detail, in the Financial Report. The Secretary of the Treasury, the Director of OMB, and the

Comptroller General of the U.S. at the GAO believe that the information discussed in the Financial Report is

important to all Americans.

The Financial Report addresses the government’s financial activity and results as of and for the fiscal years

ended September 30, 2023, and 2022. Note 30—Subsequent Events discusses events that occurred after the end of

the fiscal year that may affect the government’s financial position and condition.

Results in Brief

The “Nation by the Numbers” table on the preceding page and the following summarize key metrics about

the federal government’s financial position for and during FY 2023:

• The budget deficit increased by $319.7 b

illion (23.2 percent) to $1.7 trillion and net operating cost

decreased by $753.8 billion (18.1 percent) to $3.4 trillion.

• Net operating cost decreased due largely to significant decreases in non-cash costs (including decreases in

losses stemming from changes in assumptions affecting cost and liability estimates for the government’s

employee and veteran benefits programs (which do not affect the current year deficit) and reestimates of

long-term student loan costs).

•

The government’s gross costs of $7.7 trillion, less $539.5 billion in revenues earned for goods and

services provided to the public, plus $760.6 billion in net losses from changes in assumptions yields the

government’s net cost of $7.9 trillion, a decrease of $1.2 trillion (13.3 percent) from FY 2022.

• Tax and other revenues decreased by $460.3 billion to $4.5 trillion. Deducting these revenues from net

cost yields the federal government’s “bottom line” net operating cost of $3.4 trillion referenced above.

• Comparing total government assets of $5.4 trillion (including $1.7 trillion of loans receivable, net and

$1.2 trillion of PP&E) to total liabilities of $42.9 trillion (including $26.3 trillion in federal debt and

interest payable, and $14.3 trillion of federal employee and veteran benefits payable) yields a negative net

position of $37.5 trillion.

• The Statement of Long-Term Fiscal Projections (SLTFP) shows that the present value (PV) of total non-

interest spending, over the next 75 years, under current policy, is projected to exceed the PV of total

receipts by $73.2 trillion (total federal non-interest net expenditures from the table on the previous page).

• The debt-to-GDP ratio was approximately 97 percent at the end of FY 2023. Under current policy and

based on this report’s assumptions, it is projected to reach 531 percent by 2098. The projected continuous

rise of the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates that current policy is unsustainable.

• The Statement of Social Insurance (SOSI) shows that the PV of the government’s expenditures for Social

Security and Medicare Parts A, B and D, and other social insurance programs over 75 years is projected

to exceed social insurance revenues by about $78.4 tri

llion, a $2.5 trillion increase over 2022 social

insurance projections.

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

Where We Are Now

The government’s financial position and condition have traditionally been expressed through the Budget,

focusing on surpluses, deficits, and debt. However, this primarily cash-based discussion of the government’s net

outlays (deficit) or net receipts (surplus) tells only part of the story. The government’s accrual-based net position,

(the difference between its assets and liabilities, adjusted for unmatched transactions and balances), and its

“bottom line” net operating cost (the difference between its revenues and costs) are also key financial indicators.

The following includes brief discussions of some of the diminishing effects of the pandemic on the government’s

financial results for FY 2023. Please refer to Note 29—COVID-19 Activity and other disclosures in this Financial

Report, as well as in the individual entities’ financial statements for more information.

Comparing the Budget and the Financial Report

The Budget and the Financial Report present complementary perspectives on the government’s financial

position and condition.

• The Budget is the government’s primary financial planning and control tool. It accounts for past

government receipts and spending and includes the President’s proposed receipts and spending plan.

Receipts are cash received by the U.S. government and spending is measured as outlays, or payments

made by the federal government to the public or entities outside the government. When total receipts

exceed outlays, there is a budget surplus; conversely, if total outlays exceed total receipts, there is a

budget deficit.

• The Financial Report includes the government’s costs and revenues, assets and liabilities, and other

important financial information. It compares the government’s revenues (amounts earned, but not

necessarily collected), with costs (amounts incurred, but not necessarily paid) to derive net operating cost.

Chart 1 compares the government’s budget deficit (receipts vs. outlays) and net operating cost (revenues vs.

costs) for FYs 2019 - 2023. During FY 2023:

• A $456.8 billion decrease in receipts

more than offset a $137.1 billion

decrease in outlays resulting in a

$319.7 billion (23.2 percent) increase

in the budget deficit from $1.4 trillion

to $1.7 trillion.

• Net operating cost decreased $753.8

billion or 18.1 percent from $4.2

trillion to $3.4 trillion, due mostly to a

$1.2 trillion or 13.3 percent decrease

in net cost which more than offset a

$460.3 billion or 9.3 percent decrease

in tax and other revenues.

The $1.7 trillion difference between the

budget deficit and net operating cost for FY

2023 is primarily due to accrued costs (incurred but not necessarily paid) that are included in net operating cost,

but not the budget deficit. These are primarily actuarial costs related to federal employee and veteran benefits

programs, particularly at VA, DOD, and OPM. Other sources of differences include but are not limited to

decreases in taxes receivable, increases in advances and deferred revenue received by the federal government

from others, decreases in advances and prepayments made by the federal government.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

4

Costs and Revenues

The government’s “bottom line” net operating cost decreased $753.8 billion (18.1 percent) during FY 2023

to $3.4 trillion. It is calculated as follows:

• Starting with total gross costs of $7.7

trillion, the government subtracts

earned program revenues (e.g.,

Medicare premiums, national park

entry fees, and postal service fees) and

adjusts the balance for gains or losses

from changes in actuarial assumptions

used to estimate future federal

employee and veteran benefits

payments to derive its net cost before

taxes and other revenues of $7.9

trillion (see Chart 2), a decrease of

$1.2 trillion (13.3 percent) from FY

2022. This net decrease is the

combined effect of many offsetting

increases and decreases across the

government. For example:

o Entities administering federal employee and veteran benefits programs, including the VA, DOD, and

OPM employ a complex series of assumptions to make actuarial projections of their long-term

benefits liabilities. These assumptions include but are not limited to interest rates, beneficiary

eligibility, life expectancy, and medical cost levels. Changes in these assumptions can result in either

losses (net cost increases) or gains (net cost decreases). Across the government, these net losses from

changes in assumptions amounted to $760.6 billion in FY 2023, a loss decrease (and a corresponding

net cost decrease) of $1.4 trillion compared to FY 2022.

o In particular, VA net costs decreased $479.6 billion due largely to decreased losses from changes in

assumptions as referenced above, partially offset by an increase in costs as a result of legislation

expanding and extending eligibility for veteran’s benefits.

o DOD net costs decreased $455.6 billion due primarily to a $437.7 billion loss decrease from changes

in assumptions as referenced above. However, most of DOD’s net costs included those related to

military operations, readiness and support, procurement, personnel, and R&D.

o A $222.7 billion decrease in Treasury net costs was largely due to a decrease in costs associated with

Treasury’s pandemic relief programs, including: 1) the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery

Funds; and 2) COVID-19 related refunds and other payments such as the EIP and advances for child

tax credits.

o Education net costs decreased $521.0 billion due largely to the combined effect of: 1) an FY 2022

cost increase of $330.9 billion due largely to a $337.3 billion loan modification stemming from the

announced broad-based student loan debt relief; and 2) an FY 2023 cost decrease of $319.9 billion

from a downward modification to reverse the broad-based student loan debt relief, as a result of the

Supreme Court’s ruling on Biden v. Nebraska. Education’s FY 2023 net costs were also impacted by:

1) $71.4 billion in upward cost reestimates of the Department’s existing loan portfolio; and 2) $115.7

billion of upward modifications related to COVID-19 administrative actions, changes to repayment

plans, and other programmatic changes.

o A $54.1 billion net cost increase at HHS primarily due to a $116.1 billion increase across the

Medicare and Medicaid benefits programs largely associated with increasing benefits payments. This

cost increase was offset by a $62.0 billion cost decrease across all other HHS segments primarily due

to decreases in COVID-19 costs.

5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

o SSA net costs increased $138.8 billion due largely to a 2.5 percent increase in the number of OASI

beneficiaries, combined with an 8.7 percent COLA provided to beneficiaries in 2023.

o Interest costs related to federal debt securities held by the public increased by $181.5 billion due

largely to increases in outstanding debt held by the public and the average interest rates, which were

offset by a decrease in inflation adjustments.

• The government deducts tax and other revenues from net cost (with some adjustments) to derive its FY

2023 “bottom line” net operating cost

of $3.4 trillion.

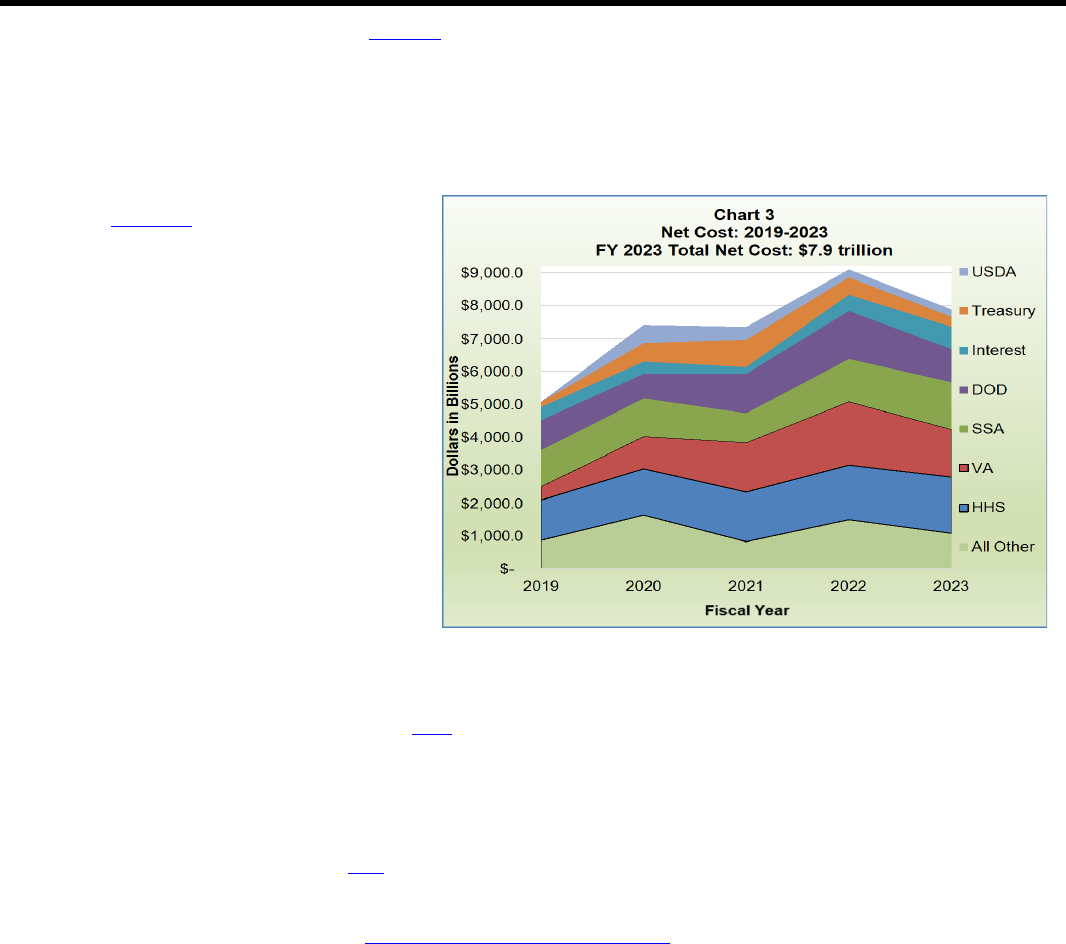

o From Chart 3, total government tax

and other revenues decreased by

$460.3 billion (9.3 percent) to

about $4.5 trillion for FY 2023 due

primarily to a decline in individual

income and tax withholdings and

corporate income taxes as well as

decreased deposits of earnings

from the Federal Reserve due to

increased interest rates.

o Together, individual income tax

and tax withholdings, and

corporate income taxes accounted

for about 91.4 percent of total tax

and other revenues in FY 2023. Other revenues include Federal Reserve earnings, excise taxes, and

customs duties.

Assets and Liabilities

Chart 4 summarizes the assets and liabilities that the government reports on its Balance Sheet. As of

September 30, 2023:

• More than three-fourths of the federal

government’s total assets ($5.4

trillion) consist of: 1) $922.2 billion in

cash and monetary assets; 2) $423.0

billion in inventory and related

property; 3) $1.7 trillion in loans

receivable, net (primarily student

loans); and 4) $1.2 trillion in net

PP&E.

o Cash and monetary assets ($922.2

billion) is comprised largely of the

operating cash of the U.S.

government. Operating cash held

by Treasury increased $21.9 billion

(3.5 percent) to $638.9 billion

during FY 2023.

o Inventory and related property ($423.0 billion) includes: 1) inventory, which is tangible personal

property that is either held for sale, in the process of production for sale, or to be consumed in the

production of goods for sale or in the provision of services for a fee; 2) OM&S, or tangible personal

property to be consumed in normal operations (e.g., spare and repair parts, ammunition, and tactical

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

6

missiles); and 3) stockpiles, or strategic and critical materials held due to statutory requirements for

use in national defense, conservation, or local/national emergencies.

o Loans receivable, net ($1.7 trillion) is comprised of loans provided by multiple agencies, including

Education and SBA, to promote the nation’s welfare by making financing available to segments of the

population not served adequately by non-federal institutions or otherwise providing for certain

activities or investments. The government’s net loan portfolio increased by $261.0 billion (18.2

percent) during FY 2023. This net increase was largely due to a $214.3 billion increase in Education’s

Federal Direct Student Loans, net, primarily due to a reversal of the broad-based student loan debt

relief as a result of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Biden v. Nebraska. Additional Loans Receivable, net

increases included Treasury’s purchase of a $50 billion note issued by a trust created by FDIC in its

receivership capacity and backed by a guarantee from the FDIC in its corporate capacity. These and

other net increases were partially offset by a $49.6 billion decrease in SBA’s loan receivables, net, due

largely to write-offs of direct disaster loans. Other changes included fluctuations in loan programs for

HUD, DOT, and DFC.

o Federal government general PP&E includes many of the physical resources that are vital to the federal

government’s ongoing operations, including buildings, structures, facilities, equipment, internal use

software, and general-purpose land. DOD comprises approximately 67.4 percent of the government’s

reported general PP&E of $1.2 trillion as of September 30, 2023.

o Other significant government resources not reported on the Balance Sheet include the government’s

power to tax and set monetary policy, natural resources, and stewardship assets. Stewardship assets,

including heritage assets and stewardship land, benefit the nation (e.g., national monuments, national

parks) and are intended to be held indefinitely.

• Total liabilities ($42.9 trillion) consist mostly of: 1) $26.3 trillion in federal debt and interest payable; and

2) $14.3 trillion in federal employee and veteran benefits payable.

o Federal debt held by the public is debt held outside of the government by individuals, corporations,

state and local governments, the FR System, foreign governments, and other non-federal entities.

o The government borrows from the public (increases federal debt levels) to finance deficits. During FY

2023, federal debt held by the public increased $2.0 trillion (8.3 percent) to $26.3 trillion.

o The government also reports about $6.9 trillion of intra-governmental debt outstanding, which arises

when one part of the government borrows from another. For example, government funds (e.g., Social

Security and Medicare Trust Funds) typically must invest excess receipts, including interest earnings,

in Treasury-issued federal debt securities. Although not reflected in Chart 4, these securities are

included in the calculation of federal debt subject to the debt limit.

o Federal debt held by the public plus intra-governmental debt equals gross federal debt, which, with

some adjustments, is subject to a statutory debt ceiling (“debt limit”). Congress and the President

increased the debt limit by $2.5 trillion in December 2021 with the enactment of P.L. 117-73. In

response to delays in raising the statutory debt limit, Treasury took extraordinary measures to meet the

government’s obligations as they came due without exceeding the debt limit from January 19 through

June 2, 2023. On June 3, 2023, P.L. 118-5 was enacted, suspending the debt limit through January 1,

2025. On Monday, June 5, 2023, Treasury discontinued its use of extraordinary measures and resumed

normal debt management operations. At the end of FY 2023, debt subject to the statutory limit was

$33.1 trillion. Increasing or suspending the debt limit does not increase spending or authorize new

spending; rather, it permits the government to continue to honor pre-existing commitments (see Note

12—Federal Debt and Interest Payable).

o Federal employee and veteran benefits payable ($14.3 trillion) represents the amounts of benefits

payable by agencies that administer the government’s pension and other benefit plans for its military

and civilian employees.

See Note 29—COVID-19 Activity, as well as the referenced agencies’ FY 2023 financial statements for

additional information about the financial effects of the federal government’s response to the pandemic. See Note

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

30—Subsequent Events for information about events that occurred after the end of the fiscal year that may affect

the government’s financial results.

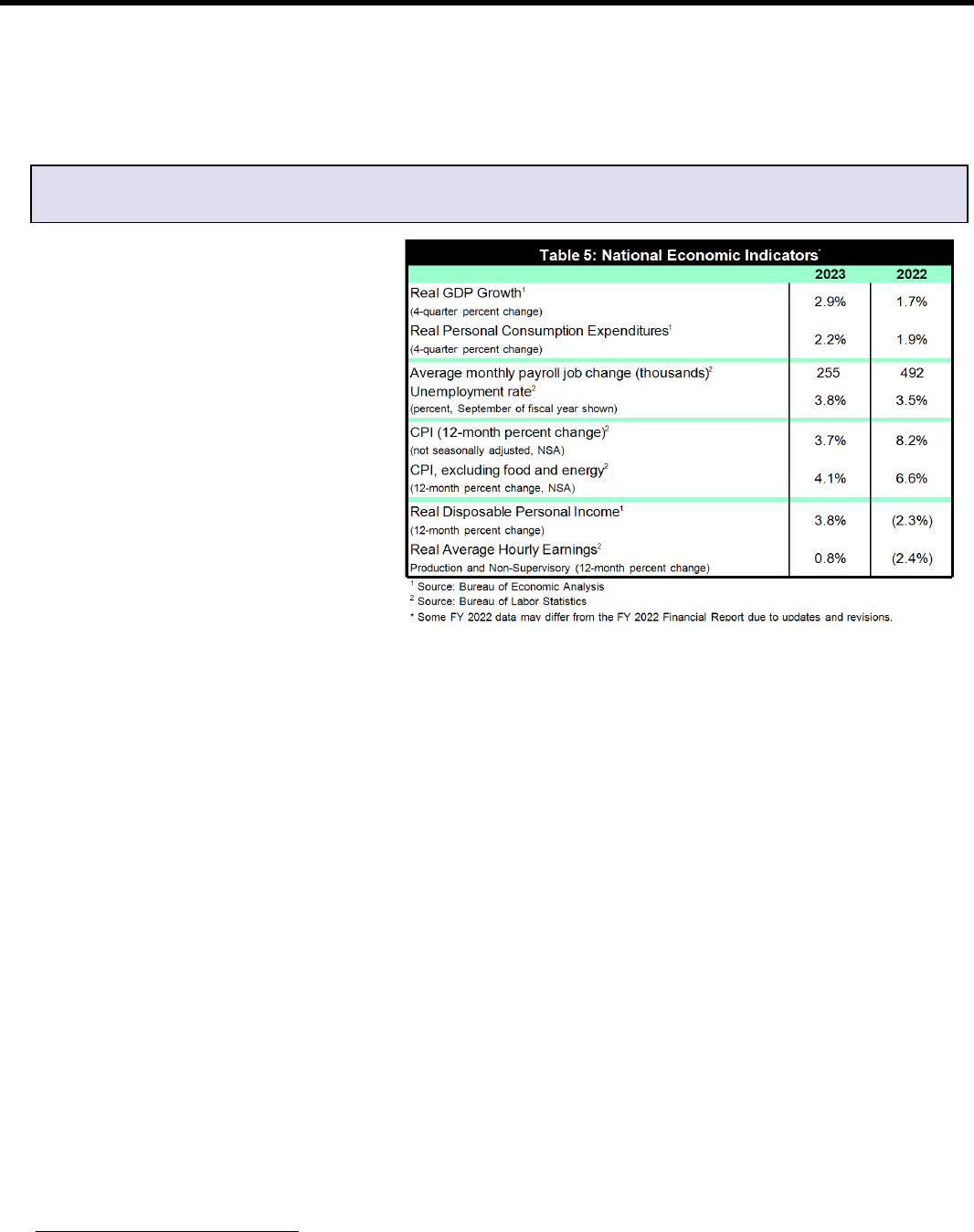

Key Economic Trends

An analysis of U.S. economic performance provides useful background when evaluating the government’s

financial statements. Over the course of FY 2023, the economy’s growth accelerated even as inflation continued

to slow. In addition, labor markets remained tight and continued to generate a substantial number of jobs but also

showed signs of very gradual easing over the course of FY 2023. These and other economic and financial

developments are discussed in greater detail in the Financial Report.

An Unsustainable Fiscal Path

An important purpose of this Financial Report is to help citizens understand current fiscal policy and the

importance and magnitude of policy reforms necessary to make it sustainable. A sustainable fiscal policy is

defined as one where the ratio of debt held by the public to GDP (the debt-to-GDP ratio) is stable or declining

over the long term. GDP measures the size of the nation’s economy in terms of the total value of all final goods

and services that are produced in a year. Considering financial results relative to GDP is a useful indicator of the

economy’s capacity to sustain the government’s many programs. This Financial Report presents data, including

debt, as a percent of GDP to help readers assess whether current fiscal policy is sustainable. The debt-to-GDP

ratio was approximately 97 percent at the end of FY 2023, which is similar to (but slightly above) the debt-to-

GDP ratio at the end of FY 2022. The long-term fiscal projections in this Financial Report are based on the same

economic and demographic assumptions that underlie the SOSI.

The current fiscal path is unsustainable. To determine if current fiscal policy is sustainable, the projections

based on the assumptions discussed in the Financial Report assume current policy will continue indefinitely.

1

The

projections are therefore neither forecasts nor predictions. Nevertheless, the projections demonstrate that policy

changes need to be enacted for the actual financial outcomes to differ from those projected.

Receipts, Spending, and the Debt

Chart 5 shows historical and current policy projections for receipts, non-interest spending by major category,

net interest, and total spending expressed

as a percent of GDP.

• The primary deficit is the

difference between non-interest

spending and receipts. The ratio

of the primary deficit to GDP is

useful for gauging long-term

fiscal sustainability.

• The primary deficit-to-GDP ratio

increased during the financial

crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19

pandemic. Spending was

elevated in 2020 and 2021 due to

funding to support economic

recovery, but increased receipts

reduced the primary deficit-to-

GDP ratio to 10.8 percent in

2021 from 13.3 percent in 2020. The primary deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2023 was 3.8 percent, increasing by

0.2 percentage points from 3.6 percent in 2022 partially due to lower receipts.

1

Current policy in the projections is based on current law, but includes extension of certain policies that expire under current law but are routinely extended

or otherwise expected to continue.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

8

• The persistent long-term gap between projected receipts and total spending shown in Chart 5 occurs

despite the projected effects of the PPACA

2

on long-term deficits.

o Enactment of the PPACA in 2010 and the MACRA (P.L. 114-10) in 2015 established cost controls for

Medicare hospital and physician payments whose long-term effectiveness is still to be demonstrated

fully.

o There is uncertainty about the extent to which these projections can be achieved and whether the

PPACA’s provisions intended to reduce Medicare cost growth will be overridden by new legislation.

Table 1 summarizes the status and projected trends of the government’s Social Security and Medicare Trust

Funds.

The primary deficit projections in Chart 5, along with those for interest rates and GDP, determine the debt-

to-GDP ratio projections in Chart 6.

• The debt-to-GDP ratio was

approximately 97 percent at the

end of FY 2023, and under

current policy and based on this

report’s assumptions is projected

to reach 531 percent in 2098.

• The debt-to-GDP ratio rises

continuously in great part because

primary deficits lead to higher

levels of debt. The continuous

rise of the debt-to-GDP ratio

indicates that current fiscal policy

is unsustainable.

• These debt-to-GDP projections

are lower than both the 2022 and

2021 Financial Report

projections.

2

The PPACA refers to P.L. 111-148, as amended by P.L. 111-152. The PPACA expands health insurance coverage, provides health insurance subsidies for

low-income individuals and families, includes many measures designed to reduce health care cost growth, and significantly reduces Medicare payment rate

updates relative to the rates that would have occurred in the absence of the PPACA. (See Note 25 and the RSI section of the Financial Report, and the 2023

Medicare Trustees Report for additional information).

9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

The Fiscal Gap and the Cost of Delaying Fiscal Policy Reform

• The 75-year fiscal gap is a measure of how much primary deficits must be reduced over the next 75 years

in order to make fiscal policy sustainable. That estimated fiscal gap for 2023 is 4.5 percent of GDP

(compared to 4.9 percent for 2022).

• This estimate implies that making fiscal policy sustainable over the next 75 years would require some

combination of spending reductions and receipt increases that equals 4.5 percent of GDP on average over

the next 75 years. The fiscal gap represents 23.8 percent of 75-year PV receipts and 19.8 percent of 75-

year PV non-interest spending.

• The timing of policy changes to make fiscal policy sustainable has important implications for the well-

being of future generations as is shown in Table 2.

o Table 2 shows that, if reform begins in 2034 or 2044, the estimated magnitude of primary surplus

increases necessary to close the 75-year fiscal gap is 5.3 percent and 6.5 percent of GDP, respectively.

The difference between the primary surplus increase necessary if reform begins in 2034 or 2044 and

the increase necessary if reform begins in 2024, an additional 0.8 and 2.0 percentage points,

respectively, is a measure of the additional burden policy delay would impose on future generations.

o The longer policy action to close the fiscal gap is delayed, the larger the post-reform primary surpluses

must be to achieve the target debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of the 75-year period. Future generations are

harmed by a policy delay because the higher the primary surpluses are during their lifetimes, the

greater is the difference between the taxes they pay and the programmatic spending from which they

benefit.

Conclusion

• Projections in the Financial Report indicate that the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to rise

over the 75-year projection period and beyond if current policy is kept in place. The projections in this

Financial Report show that current policy is not sustainable.

• If changes in fiscal policy are not so abrupt as to slow economic growth and those policy changes are

adopted earlier, then the required changes to revenue and/or spending will be smaller to return the

government to a sustainable fiscal path.

Reporting on Climate Change

As stated in Executive Order 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad “the United States and

the world face a profound climate crisis…Domestic action must go hand in hand with United States international

leadership, aimed at significantly enhancing global action.” In response, the administration has enacted key

legislation and issued important policy actions. As summarized in the MD&A section of the Financial Report,

many of the 24 CFO Act agencies have leveraged their FY 2023 financial statements to discuss a wide range of

topics concerning how their agencies are responding to the climate crisis, including providing links to agency

Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plans.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

10

Find Out More

The FY 2023 Financial Report and other information about the nation’s finances are available at:

• Treasury, https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/fsreports/rpt/finrep/fr/fr_index.htm and

https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/;

• OMB’s Office of Federal Financial Management, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/management/office-

federal-financial-management/; and

• GAO, https://www.gao.gov/federal-financial-accountability.

The GAO audit report on the U.S. government’s consolidated financial statements can be found beginning on page 218

of the full Financial Report

. GAO was unable to express an opinion (disclaimed) on these consolidated financial

statements for the reasons discussed in the audit report.

11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TO THE 2023 FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

This page is intentionally blank.

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

12

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND

ANALYSIS

Introduction

The FY 2023 Financial Report provides the President, Congress, and the American people with a comprehensive view

of the federal government’s financial position and condition; and discusses important financial issues and significant

conditions that may affect future operations, including the need to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long-term.

Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 331(e)(1), Treasury, in cooperation with OMB, must submit an audited (by GAO) financial

statement for the preceding fiscal year, covering all accounts and associated activities of the executive branch of the U.S.

government

1

to the President and Congress no later than six months after the September 30 fiscal year-end.

The Financial Report is prepared from the financial information provided by 166 federal consolidation entities (see

organizational chart on the next page and Appendix A). As it has for the past 25 years, GAO issued a disclaimer of opinion

on the accrual-based, consolidated financial statements for the fiscal years ended September 30, 2023, and 2022. GAO also

issued a disclaimer of opinion on the sustainability financial statements, which consist of the 2023 and 2022 SLTFP; the

2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, and 2019 SOSI; and the 2023 and 2022 SCSIA. A disclaimer of opinion indicates that sufficient

information was not available for the auditors to determine whether the reported financial statements were fairly presented in

accordance with GAAP. In FY 2023, 32

2

of the 40 most significant entities earned unmodified (“clean”) opinions on their

financial statements.

The FY 2023 Financial Report consists of:

• MD&A, which provides management’s perspectives on and analysis of information presented in the Financial

Report, such as financial and performance trends;

• Financial statements and the related notes to the financial statements;

• RSI and Other Information; and

• GAO’s audit report.

This Financial Report addresses the government’s financial activity and results as of and for the fiscal years ended

September 30, 2023, and 2022. Note 30—Subsequent Events discusses events that occurred after the end of the fiscal year

that may affect the government’s financial position and condition.

In addition, the Executive Summary to this Financial Report provides a quick reference to the key issues in the

Financial Report and an overview of the government's financial position and condition.

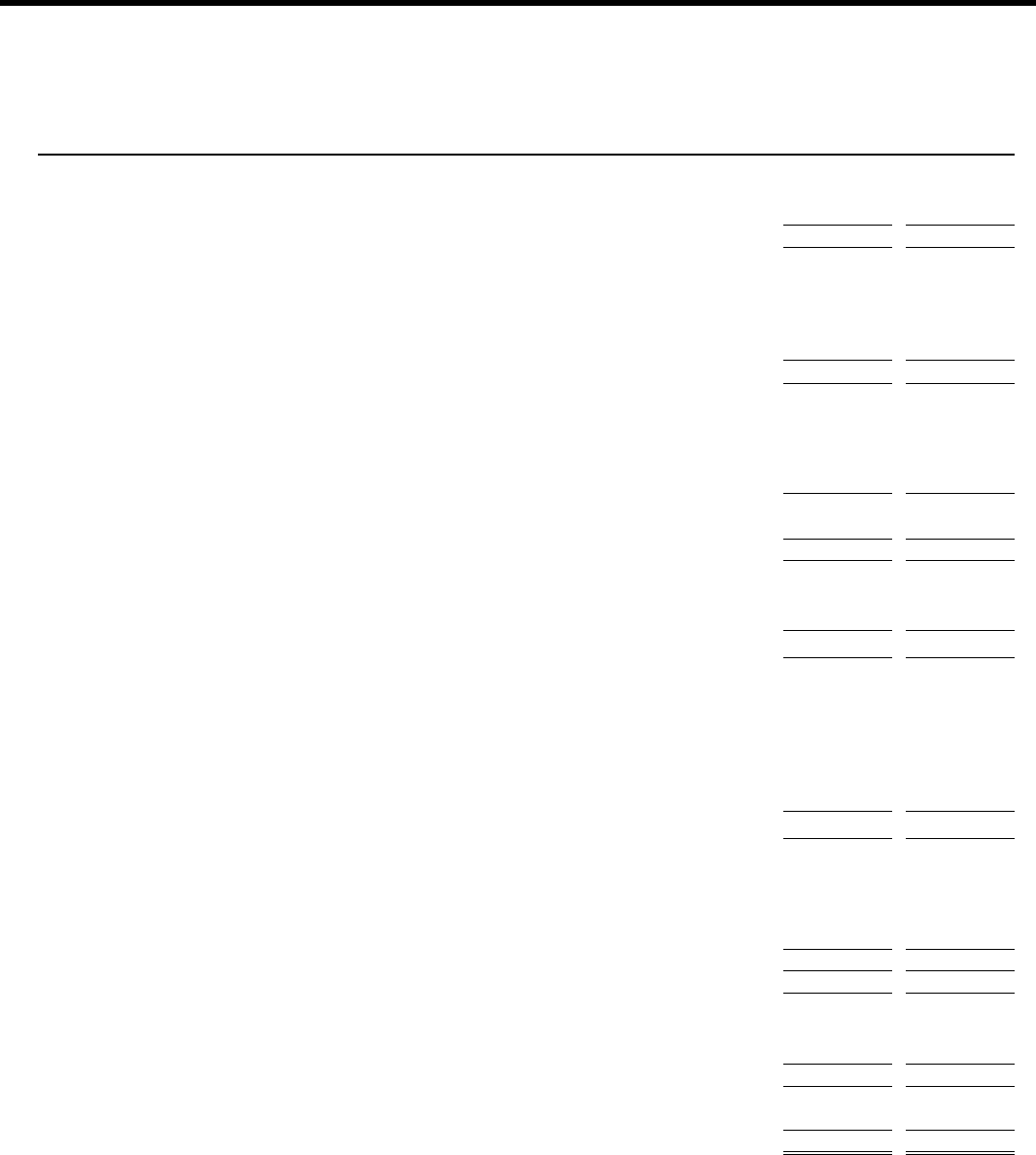

Mission & Organization

The government’s fundamental mission is derived from the Constitution: “…to form a more perfect union, establish

justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of

liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” The government’s functions have evolved over time to include health care, income

security, veterans benefits and services, housing and transportation, security, and education. Exhibit 1 provides an overview

of how the U.S. government is organized.

1

The Government Management Reform Act of 1994 has required such reporting, covering the executive branch of the government, beginning with financial

statements prepared for FY 1997. The consolidated financial statements include the legislative and judicial branches.

2

The 32 entities include the HHS, which received disclaimers of opinion on its 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, and 2019 SOSI and on its 2023 and 2022 SCSIA.

13

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

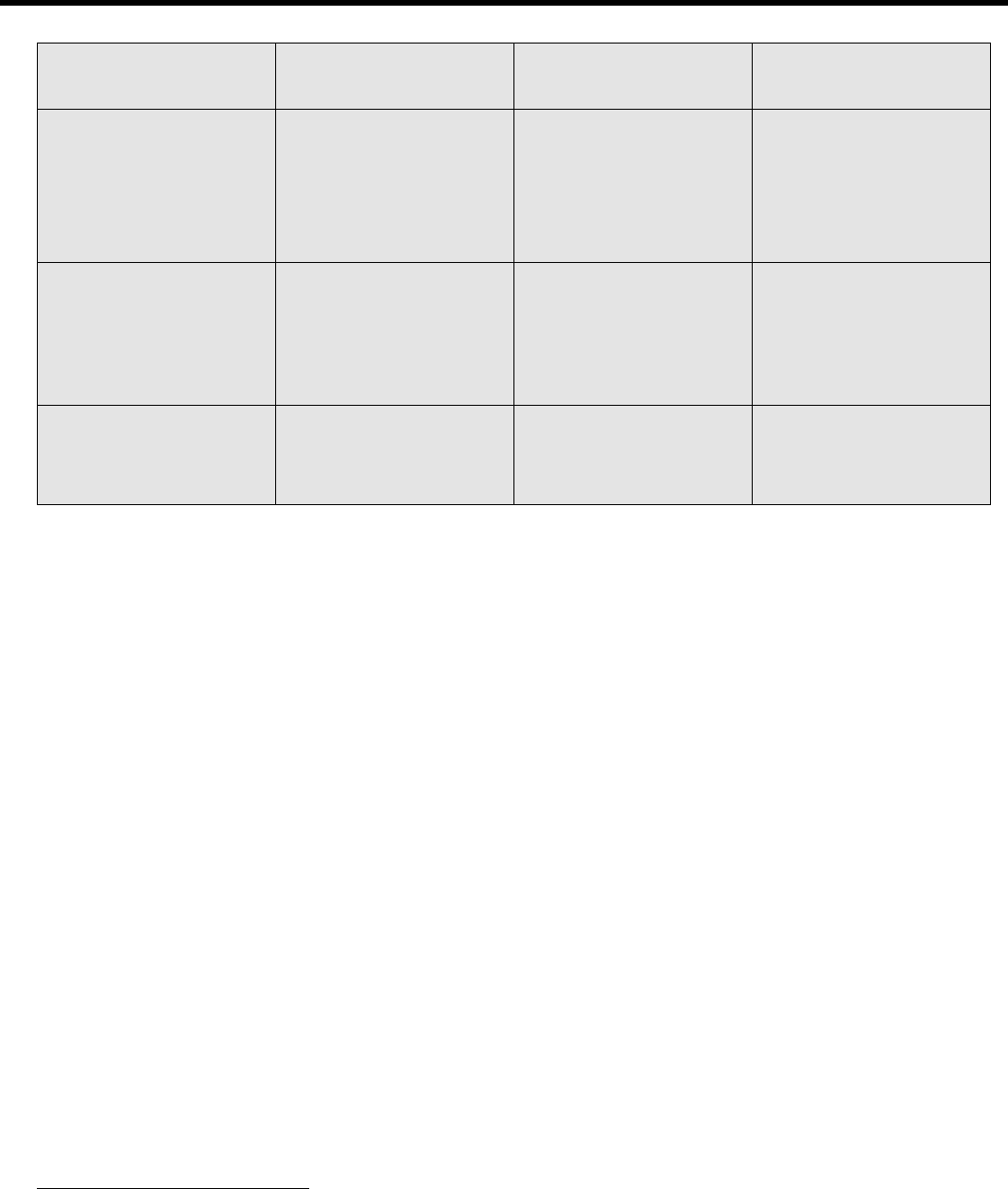

Exhibit 1

EXECUTIVE BRANCH

THE PRESIDENT

THE VICE PRESIDENT

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

White House Office

Office of the Vice President

Council of Economic Advisers

Council on Environmental Quality

National Security Council

Office of Administration

Office of Management and Budget

Office of National Drug Control Policy

Office of Policy Development

Office of Science and Technology Policy

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

LEGISLATIVE BRANCH

THE CONGRESS

SENATE HOUSE

Architect of the Capitol

U.S. Botanic Garden

Government Accountability Office

Government Publishing Office

Library of Congress

Congressional Budget Office

U.S. Capitol Police

JUDICIAL BRANCH

THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE U.S.

U.S. Courts of Appeals

U.S. District Courts

Territorial Courts

U.S. Court of International Trade

U.S. Court of Federal Claims

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts

Federal Judicial Center

U.S. Sentencing Commission

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICERS ACT AGENCIES (24)

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY

NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

DEPARTMENT OF STATE

U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION

SIGNIFICANT CONSOLIDATION ENTITIES (16)

EXPORT-IMPORT BANK OF THE U.S.

PENSION BENEFIT GUARANTY CORPORATION

FARM CREDIT SYSTEM INSURANCE CORPORATION

RAILROAD RETIREMENT BOARD

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION

SECURITY ASSISTANCE ACCOUNTS

GENERAL FUND OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

MILLENNIUM CHALLENGE CORPORATION

TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY

NATIONAL CREDIT UNION ADMINISTRATION

U.S. INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FINANCE CORP

NATIONAL RAILROAD RETIREMENT INVESTMENT TRUST

U.S. POSTAL SERVICE

OTHER CONSOLIDATION ENTITIES LISTED IN APPENDIX A OF THIS FINANCIAL REPORT (126)

THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT

THE CONSTITUTION

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

14

The Government’s Financial Position and Condition

This Financial Report presents the government’s financial position at the end of the fiscal year, explains how and why

the financial position changed during the year, and discusses the government’s financial condition and how it may change in

the future.

15

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Table 1 on the previous page and the following summarize the federal government’s financial position:

• This Financial Report includes discussion and analysis of the effects that the federal government’s response to the

COVID-19 pandemic continued to have on the government’s financial position during FY 2023.

• During FY 2023, the budget deficit increased by $319.7 billion (23.2 percent) to $1.7 trillion. However, net

operating cost decreased by $753.8 billion (18.1 percent) to $3.4 trillion.

• Net operating cost decreased due largely to significant decreases in non-cash costs (including decreases in losses

stemming from changes in assumptions affecting cost and liability estimates for the government’s employee and

veteran benefits programs (which do not affect the current year deficit), and reestimates of long-term student loan

costs).

• The government’s gross costs of $7.7 trillion, less $539.5 billion in revenues earned for goods and services provided

to the public (e.g., Medicare premiums, national park entry fees, and postal service fees), plus $760.6 billion in net

losses from changes in assumptions (e.g., interest rates, inflation, disability claims rates) yields the government’s net

cost of $7.9 trillion, a decrease of $1.2 trillion or 13.3 percent compared to FY 2022.

• Total tax and other revenues decreased $460.3 billion to $4.5 trillion. Deducting these revenues from net cost results

in a “bottom line” net operating cost of $3.4 trillion for FY 2023, a decrease of $753.8 billion or 18.1 percent

compared to FY 2022.

• Comparing total FY 2023 government assets of $5.4 trillion (including $1.7 trillion of loans receivable, net and $1.2

trillion of PP&E) to total liabilities of $42.9 trillion (including $26.3 trillion in federal debt and interest payable

3

,

and $14.3 trillion of federal employee and veteran benefits payable) yields a negative net position of $37.5 trillion.

• The budget deficit is primarily financed through borrowing from the public. As of September 30, 2023, debt held by

the public, excluding accrued interest, was $26.3 trillion. This amount, plus intra-governmental debt ($6.9 trillion)

equals gross federal debt, which, with some adjustments, is subject to the statutory debt limit. As of September 30,

2023, the government’s total debt subject to the debt limit was $33.1 trillion. Congress and the President increased

the debt limit by $480.0 billion in October 2021 and by $2.5 trillion in December 2021. On June 3, 2023, P.L. 118-5

was enacted, suspending the debt limit through January 1, 2025.

This Financial Report also contains information about projected impacts on the government’s future financial condition.

Under federal accounting rules, social insurance amounts as reported in both the SLTFP and in the SOSI are not considered

liabilities of the government. From Table 1:

• The SLTFP shows that the PV

4

of total non-interest spending, including Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid,

defense, and education, etc., over the next 75 years, under current policy, is projected to exceed the PV of total

receipts by $73.2 trillion (total federal non-interest net expenditures from Table 1).

• The SOSI shows that the PV of the government’s expenditures for Social Security and Medicare Parts A, B and D,

and other social insurance programs over 75 years is projected to exceed social insurance revenues

5

by about $78.4

trillion, a $2.5 trillion increase over 2022 social insurance projections.

• The Social Insurance and Total Federal Non-Interest Net Expenditures measures in Table 1 differ primarily because

total non-interest net expenditures from the SLTFP include the effects of general revenues and non-social insurance

spending, neither of which is included in the SOSI.

The government’s current financial position and long-term financial condition can be evaluated both in dollar terms and

in relation to the economy. GDP is a measure of the size of the nation’s economy in terms of the total value of all final goods

and services that are produced in a year. Considering financial results relative to GDP is a useful indicator of the economy’s

capacity to sustain the government’s many programs. For example:

• The budget deficit increased from $1.4 trillion in FY 2022 to $1.7 trillion in FY 2023. The deficit-to-GDP ratio also

increased from 5.4 percent in FY 2022 to 6.3 percent in 2023.

• The budget deficit is primarily financed through borrowing from the public. As of September 30, 2023, the $26.3

trillion in debt held by the public, excluding accrued interest, equates to 97 percent of GDP.

• The 2023 SOSI projection of $78.4 trillion net PV excess of expenditures over receipts over 75 years represents

about 4.4 percent of the PV of GDP over 75 years. The excess of total projected non-interest spending over receipts

of $73.2 trillion from the SLTFP represents 3.8 percent of GDP over 75 years. As discussed in this Financial

Report, changes in these projections can, in turn, have a significant impact on projected debt as a percent of GDP.

• To prevent the debt-to-GDP ratio from rising over the next 75 years, a combination of non-interest spending

reductions and receipts increases that amounts to 4.5 percent of GDP on average is needed (4.9 percent of GDP on

3

On the government’s Balance Sheet, federal debt and interest payable consists of Treasury securities, net of unamortized discounts and premiums, and

accrued interest payable. The “public” consists of individuals, corporations, state and local governments, FRB, foreign governments, and other entities

outside the federal government.

4

PVs recognize that a dollar paid or collected in the future is worth less than a dollar today because a dollar today could be invested and earn interest. To

calculate a PV, future amounts are thus reduced using an assumed interest rate, and those reduced amounts are summed.

5

Social Security is funded by the payroll taxes and revenue from taxation of benefits. Medicare Part A is funded by the payroll taxes, revenue from taxation

of benefits, and premiums that support those programs. Medicare Parts B and D are primarily financed by transfers from the General Fund, which are

presented, and by accounting convention, eliminated in the SOSI. For the FYs 2023 and 2022 SOSI, the amounts eliminated totaled $48.5 trillion and $47.5

trillion, respectively. In addition, the SOSI programs include DOL’s Black Lung Program, the projection period for which is 40 years.

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

16

average in the 2022 projections). The fiscal gap in the 2023 projections represents 23.8 percent of 75-year PV

receipts and 19.8 percent of 75-year PV non-interest spending.

FY 2023 Financial Statement Audit Results

For FY 2023, GAO issued a disclaimer of audit opinion on the accrual-based, government-wide financial statements, as

it has for the past 26 years, due to certain material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting and other

limitations on the scope of its work. In addition, GAO issued a disclaimer of opinion on the sustainability financial

statements due to significant uncertainties primarily related to the achievement of projected reductions in Medicare cost

growth and certain other limitations. GAO’s audit report on page 218 of this Financial Report, discusses GAO’s findings.

In FY 2023, 19 of the 24 entities required to issue audited financial statements under the CFO Act received unmodified

audit opinions, as did 13 of 16 additional significant consolidation entities (see Table 10 and Appendix A).

6

The Government-wide Reporting Entity

This Financial Report includes the financial status and activities of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of

the federal government. SFFAS No. 47, Reporting Entity, provides criteria for identifying organizations that are

consolidation entities, disclosure entities, and related parties. Such criteria are summarized in Note 1.A, Significant

Accounting Policies, Reporting Entity, and in Appendix A, which lists the entities included in this Financial Report by these

categories. The assets, liabilities, results of operations, and related activity for consolidation entities are consolidated in the

financial statements.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac meet the criteria for disclosure entities and, consequently, are not consolidated into the

government’s financial statements. However, the values of the investments in such entities, changes in value, and related

activity with these entities are included in the consolidated financial statements. The FR System and the SPVs are disclosure

entities and are not consolidated into the government’s financial statements. See Note 1.A and Note 27—Disclosure Entities

and Related Parties for additional information. In addition, per SFFAS No. 31, Accounting for Fiduciary Activities, fiduciary

funds are not consolidated in the government financial statements.

7

Most significant consolidation entities prepare financial statements that include financial and performance related

information, as well as Annual Performance Reports. More information may be obtained from entities’ websites indicated in

Appendix A and at https://www.performance.gov/.

The following pages contain a more detailed discussion of the government’s financial results for FY 2023, the Budget,

the economy, the debt, and a long-term perspective about fiscal sustainability, including the government’s ability to meet its

social insurance benefits obligations. The information in this Financial Report, when combined with the Budget, collectively

presents information on the government’s financial position and condition.

Accounting Differences Between the Budget and the Financial

Report

Each year, the administration issues two reports that detail the government’s financial results: the Budget and this

Financial Report. The exhibit on the following page provides the key characteristics and differences between the two

documents.

Treasury generally prepares the financial statements in this Financial Report on an accrual basis of accounting as

prescribed by GAAP for federal entities.

8

These principles are tailored to the government’s unique characteristics and

circumstances. For example, entities prepare a uniquely structured “Statement of Net Cost,” which is intended to present net

government resources used in its operations. Also, unique to government is the preparation of separate statements to

reconcile differences and articulate the relationship between the Budget and financial accounting results.

6

The 19 entities include the HHS, which received disclaimers of opinions on its 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, and 2019 SOSI and its 2023 and 2022 SCSIA. The

13 entities include the FDIC, the NCUA, and the FCSIC, which operate on a calendar year basis (December 31 year-end). Statistic reflects 2022 audit results

for these organizations if 2023 results are not available.

7

See Note 23—Fiduciary Activities.

8

Under GAAP, most U.S. government revenues are recognized on a ‘modified cash’ basis, (see Financial Statement Note 1.B). The SOSI presents the PV of

the estimated future revenues and expenditures for scheduled benefits over the next 75 years for the Social Security, Medicare, RRP; and 25 years for the

Black Lung program. The SLTFP presents the 75-year PV of the projected future receipts and non-interest spending for the federal government.

17

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Budget of the U.S. Government

Financial Report of the U.S. Government

Prepared primarily on a “cash basis”

• Initiative-

based and prospective: focus on

current and future initiatives planned and

how resources will be used to fund them.

•

Receipts (“cash in”), taxes and other

collections recorded when received.

• Outlays (“cash out”), largely recorded when

payment is made.

Prepared on an “accrual basis” and “modified cash basis”

• Entity-based and retrospective –

prior and present

resources used to implement initiatives.

• Revenue: Tax revenue (more than 90.0 percent of total

revenue) recognized on modified cash basis (see Financial

Statement Note 1.B). Remainder recognized when earned,

but not necessarily received.

• Costs: recognized when incurred, but not necessarily paid.

Budget Deficit vs. Net Operating Cost

Three key components of the Budget process are: 1) appropriations; 2) obligations; and 3) outlays. An appropriation is a

provision of law authorizing the expenditure of funds for a given purpose. Rescissions and cancellations are reductions in law

of budgetary resources. They are considered permanent reductions unless legislation clearly indicates that the reduction is

temporary. Once funds are appropriated by Congress, Treasury issues warrants that officially establish the amounts available

to be obligated and spent (i.e., expended or outlayed) by each agency. An agency’s obligation of funds is a binding agreement

to outlay funds for a particular purpose immediately or in the future. The budget deficit is measured as the excess of outlays,

or payments made by the government, over receipts, or cash received by the government.

Net operating cost, calculated on an accrual basis, is the excess of costs (what the government has incurred but has not

necessarily paid) over revenues (what the government has collected and expects to collect but has not necessarily received).

As shown in Chart 1, net operating cost typically exceeds the budget deficit due largely to the inclusion of cost accruals

associated with increases in estimated liabilities for the government’s postemployment benefit programs for its military and

civilian employees and veterans as well as environmental liabilities.

The government’s

primarily cash-based

9

budget

deficit increased by $319.7

billion (23.2 percent) from

approximately $1.4 trillion in

FY 2022 to about $1.7 trillion

in FY 2023 due to a $456.8

billion decrease in receipts

which more than offset a

$137.1 billion decrease in

outlays in FY 2023. The

decrease in receipts can be

attributed to lower individual

income tax receipts as capital

gains realizations fell and lower

deposits of earnings by the

Federal Reserve due to higher

interest rates. These decreases

were partially offset by higher

social insurance and retirement

receipts due to a strong labor

market boosting wages and

salaries. The decrease in outlays in part reflects the broad-based student loan debt relief, which increased outlays in FY 2022,

and the effect of the reversal of broad-based debt relief in FY 2023 as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in Biden v.

Nebraska. It also reflects decreases due to the expiration of the expanded child tax credit as well as reductions in COVID-19

related spending, including spending by Treasury from the Coronavirus Relief Fund and by the Food and Nutrition Service

for SNAP and child nutrition programs. Outlays for some other categories of spending increased, including Social Security,

Medicare, Medicaid, and net interest.

10

9

Interest outlays on Treasury debt held by the public are recorded in the Budget when interest accrues, not when the interest payment is made. For federal

credit programs, outlays are recorded when loans are disbursed, in an amount representing the PV cost to the government, commonly referred to as credit

subsidy cost. Credit subsidy cost excludes administrative costs.

10

10/20/23 press release – Joint Statement of Janet L. Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury, and Shalanda D. Young, Director of the Office of Management and

Budget, on Budget Results for Fiscal Year 2023. Note that some amounts in this Financial Report reflect updates subsequent to publication of the press

release.

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

18

Treasury’s September 2023 MTS provides fiscal year-end receipts, spending, and deficit information for this Financial

Report. The MTS presents primarily cash-based spending, or outlays, for the fiscal year in a number of ways, including by

month, by entity, and by budget function classification. The Budget is divided into approximately 20 categories, or budget

functions, as a means of organizing federal spending by primary purpose (e.g., National Defense, Transportation, and

Health). Multiple entities may contribute to one or more budget functions, and a single budget function may be associated

with only one entity. For example, DOD, DHS, DOE, and multiple other entities administer programs that are critical to the

broader functional classification of National Defense. DOD, OPM, and many other entities also administer Income Security

programs (e.g., retirement benefits, housing, financial assistance). By comparison, the Medicare program is a budget function

category unto itself and is administered exclusively at the federal level by HHS. Federal spending information by budget

function and other categorizations may be found in the September 2023 MTS.

11

The government’s largely accrual-based net operating cost decreased by $753.8 billion (18.1 percent) to $3.4 trillion

during FY 2023. As discussed in this Financial Report, as the deficit is affected by changes in both receipts and outlays, so

too are the government’s net operating costs affected by changes in both revenues and costs.

The Reconciliation of Net Operating Cost and Budget Deficit statement articulates the relationship between the

government’s accrual-based net operating cost and the primarily cash-based budget deficit. The difference between the

government’s budget deficit and net operating cost is typically impacted by many variables. For example, from Table 2, 88

percent of the $1.7 trillion net difference for FY 2023 is attributable to a $1.5 trillion net increase in liabilities for federal

employee and veteran benefits payable (see Note 13—Federal Employee and Veteran Benefits Payable). Other differences

include: 1) a $108.1 billion increase in advances from others and deferred revenue (see Note 17—Advances from Others and

Deferred Revenue); 2) a $55.0 billion decrease in net taxes receivable (see Note 3—Accounts Receivable, Net); and 3) a

$45.4 billion decrease in advances and prepayments made by the federal government (see Note 9—Advances and

Prepayments).

The Government’s Net Position: “Where We Are”

The government’s financial position and condition have traditionally been expressed through the Budget, focusing on

surpluses, deficits, and debt. However, this primarily cash-based discussion of the government’s net outlays (deficit) or net

receipts (surplus) tells only part of the story. The government’s accrual-based net position, (the difference between its assets

and liabilities, adjusted for unmatched transactions and balances), and its “bottom line” net operating cost (the difference

between its revenues and costs) are also key financial indicators. The following includes brief discussions of some of the

diminishing effects of the pandemic on the government’s financial results for FY 2023. Please refer to Note 29—COVID-19

Activity and other disclosures in this Financial Report, as well as in the individual entities’ financial statements for more

information.

Costs and Revenues

The government’s Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position, much like a corporation’s income statement,

shows the government’s “bottom line” and its impact on net position (i.e., assets net of liabilities, adjusted for unmatched

transactions and balances). To derive the government’s “bottom line” net operating cost, the Statement of Net Cost first

shows how much it costs to operate the federal government, recognizing expenses when incurred, regardless of when

payment is made (accrual basis). It shows the derivation of the government’s net cost or the net of: 1) gross costs, or the costs

11

Final MTS for FY 2023 through September 30, 2023 and Other Periods.

19

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

of goods produced and services rendered by the government; 2) the earned revenues generated by those goods and services

during the fiscal year; and 3) gains or losses from changes in actuarial assumptions used to estimate certain liabilities. This

amount, in turn, is offset against the government’s taxes and other revenue reported in the Statement of Operations and

Changes in Net Position to calculate the “bottom line” or net operating cost.

Table 3 shows that the government’s “bottom line” net operating cost decreased $753.8 billion (18.1 percent) during

2023 from $4.2 trillion to $3.4 trillion. This decrease is due mostly to a $1.2 trillion (13.3 percent) decrease in net costs,

which more than offset a $460.3 billion (9.3 percent) decrease in tax and other revenues over the past fiscal year as discussed

in the following.

Gross Cost and Net Cost

The FY 2023 Statement of Net Cost starts with the government’s total gross costs of $7.7 trillion, subtracts $539.5

billion in revenues earned for goods and services provided (e.g., Medicare premiums, national park entry fees, and postal

service fees), and adjusts the balance for gains or losses from changes in actuarial assumptions used to estimate certain

liabilities ($760.6 billion loss), including federal employee and veteran benefits to derive its net cost of $7.9 trillion, a $1.2

trillion (13.3 percent) decrease compared to FY 2022.

Typically, the annual change in the government’s net cost is the result of a variety of offsetting increases and decreases

across entities. Offsetting changes in federal entity net cost during FY 2023 included:

• Entities administering federal employee and veteran benefits programs employ a complex series of assumptions,

including but not limited to interest rates,

beneficiary eligibility, life expectancy, and

medical cost levels, to make actuarial

projections of their long-term benefits

liabilities. Changes in these assumptions

can result in either losses (net cost

increases) or gains (net cost decreases).

Across the government, these net losses

from changes in assumptions amounted to

$760.6 billion in FY 2023, a net loss (and

a corresponding net cost) decrease of $1.4

trillion compared to FY 2022. The primary

entities that administer programs impacted

by these assumptions – typically federal

employee pension and benefit programs –

are the VA, DOD, and OPM. All three of

these entities recorded losses from

changes in assumptions in the amounts of

$111.9 billion, $89.3 billion, and $558.8 billion, respectively. These actuarial estimates and the resulting gains or

losses from changes in assumptions can sometimes cause significant swings in total entity costs from year to year.

For example, for FY 2023, net cost decreases at OPM ($88.5 billion), DOD ($455.6 billion), and VA ($479.6

billion) were significantly impacted by the decreases in losses from assumption changes at these entities.

• A $479.6 billion decrease in VA net cost was impacted largely by a $967.7 billion decrease in losses from changes

in assumptions as referenced above, partially offset by an increase in costs as a result of legislation expanding and

extending the eligibility for veteran's benefits.

• The $455.6 billion decrease in DOD net cost is primarily due to a $437.7 billion decrease in losses from changes in

assumptions referenced above. While losses from changes in assumptions represented the largest decrease, the

majority (more than 80 percent) of DOD costs are attributable to a wide range of functions, including military

operations, readiness, and support; procurement; military personnel; and R&D.

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

20

• The $222.7 billion decrease in Treasury net costs is largely due to a decrease in costs associated with Treasury’s

pandemic relief programs. As discussed in Note 29—COVID-19 Activity, Treasury’s net costs related to COVID-19

relief efforts decreased $105.5 billion, from $164.4 billion to $58.9 billion, during FY 2023, mainly attributed to a

reduction in the estimated amount of eligible costs incurred by state and local, territorial, and tribal program

recipients of Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. In addition, Treasury gross costs reported in this

Financial Report reflect a decrease in COVID-19 related refunds and other payments, such as EIP and advances for

child tax credits, from $89.2 billion to $53.4 billion.

• A $521.0 billion decrease at

Education, due largely to the combined

effect of: 1) the announced broad-

based student loan debt relief in

continued response to the pandemic to

help borrowers at highest risk of

delinquencies or default once

payments resumed; and 2) the reversal

of the announced broad-based student

loan debt relief as a result of the

Supreme Court’s ruling in Biden v.

Nebraska. The combined effect on

Education’s net cost was: 1) an FY

2022 cost increase of $330.9 billion,

due largely to a $337.3 billon upward

cost modification to its direct loan

program stemming from the

announced broad-based relief; and 2) a

$319.9 billion downward cost

modification in FY 2023 related to the

student loan debt relief. Education’s FY 2023 costs were also impacted by: 1) a $71.4 billion upward loan reestimate

of the costs of its existing loan portfolio; and 2) $115.7 billion in upward modifications related to COVID-19

administrative actions, changes to repayment plans, and other programmatic changes.

• A $54.1 billion net cost increase at HHS was primarily due to $116.1 billion across the Medicare and Medicaid

benefit programs largely associated with increasing benefits. Notably, Medicare HI costs increased due to increases

in HI benefit expenses of $26.6 billion and contingent liability of $10.4 billion. Medicaid benefit expense increased

$19.1 billion from higher grant awards to the states due to the continuation of the COVID-19 relief, offset by $1.1

billion decrease in contingent liability expenses for the state plan amendments. HHS also experienced a $62.0 billion

decrease across all other HHS segments primarily due to decreased COVID-19 costs.

• A $138.8 billion increase at SSA, due to a 2.5 percent increase in the number of OASI beneficiaries, and the 8.7

percent COLA provided to beneficiaries in 2023. The OASI, DI, and SSI net cost increased by 12.0 percent, 6.0

percent, and 0.1 percent respectively. Total benefit expenses increased by $137.8 billion or 10.8 percent.

• A $181.5 billion increase in interest on debt held by the public primarily attributable to an increase in the

outstanding debt held by the public and an increase in the average interest rates, which were partially offset by a

decrease in inflation adjustments.

Chart 2 shows the composition of the government’s net cost for FY 2023, and Chart 3 shows the five-year trend in the

largest agency cost components. In FY 2023, approximately 87 percent of the federal government’s total net cost came from

only six agencies (HHS, VA, SSA, DOD, Treasury, USDA), and interest on the debt. The other 150-plus entities included in

the government’s FY 2023 Statement of Net Cost accounted for a combined 13 percent of the government’s total net cost for

FY 2023. HHS and SSA net costs for FY 2023 ($1.7 trillion and $1.4 trillion, respectively) are largely attributable to major

social insurance programs administered by these entities. VA net costs of $1.5 trillion support health, education and other

benefits programs for our nation’s veterans. DOD net costs of $1.0 trillion relate primarily to operations, readiness, and

support; personnel; research; procurement; and retirement and health benefits. Treasury net costs of $303.7 billion support a

broad array of programs that promote conditions for sustaining economic growth and stability, protecting the integrity of our

nation’s financial system, and effectively managing the U.S. government’s finances and resources. USDA net costs of $226.3

billion support a wide range of programs that provide effective, innovative, science-based public policy leadership in

agriculture, food and nutrition, natural resource protection and management, rural development, and related issues with a

commitment to deliver equitable and climate-smart opportunities that inspire and help America thrive.

21

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Tax and Other Revenues

As noted earlier, tax and other revenues from the Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position are deducted

from total net cost to derive the government’s

“bottom line” net operating cost. Chart 4 shows that

total tax and other revenue decreased by $460.3

billion or 9.3 percent to $4.5 trillion for FY 2023.

This decrease is attributable mainly to an overall

decline in income tax collections, primarily from

individuals and corporations, coupled with

decreased deposits of earnings from the Federal

Reserve due to increased interest rates. Earned

revenues from Table 3 are not considered “taxes

and other revenue” and, thus, are not shown in

Chart 4. Individual income tax and tax

withholdings and corporate income taxes accounted

for about 83.1 percent and 8.2 percent of total

revenue, respectively in FY 2023; other revenues

from Chart 4 include Federal Reserve earnings,

excise taxes, unemployment taxes, and customs

duties.

As previously shown in Table 3, the decrease in tax and other revenue was more than offset by the decrease in net cost,

yielding a $753.8 billion decrease to the government’s bottom line net operating cost to $3.4 trillion for FY 2023.

Tax Expenditures

Tax and other revenues reported reflect the effects of tax expenditures, which are special exclusions, exemptions,

deductions, tax credits, preferential tax rates, and tax deferrals that allow individuals and businesses to reduce taxes they may

otherwise owe. Tax expenditures may be viewed as alternatives to other policy instruments, such as spending or regulatory

programs. For example, the government supports college attendance through both spending programs and tax expenditures.

The government uses Pell Grants to help low- and moderate-income students afford college and allows certain funds used to

meet college expenses to grow tax free in special college savings accounts. Tax expenditures may include deductions and

exclusions which reduce the amount of income subject to tax (e.g., deductions for personal residence mortgage interest). Tax

credits, which reduce tax liability dollar for dollar for the amount of credit (e.g., child tax credit), are also considered tax

expenditures. Tax expenditures may also allow taxpayers to defer tax liability.

Receipts in the calculation of surplus or deficit, and tax revenues in the calculation of net position, reflect the effect of

tax expenditures. As discussed in more detail in the Other Information section of this Financial Report, tax expenditures will

generally lower federal government receipts although tax expenditure estimates do not necessarily equal the increase in

federal revenues (or the change in the Budget balance) that would result from repealing these special provisions.

Tax expenditures are reported annually in the Analytical Perspectives of the Budget. In addition, current and past tax

expenditure estimates and descriptions can be found at the following location from Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy:

https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/tax-expenditures.

Assets and Liabilities

The government’s net position at the end of the fiscal year is derived by netting the government’s assets against its

liabilities, as presented in the Balance Sheet (summarized in Table 4).

12

The Balance Sheet does not include the financial

value of the government’s sovereign powers to tax, regulate commerce, or set monetary policy or value of nonoperational

resources of the government, such as national and natural resources, for which the government is a steward. In addition, as is

the case with the Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position, the Balance Sheet includes a separate presentation of

the portion of net position related to funds from dedicated collections. Moreover, the government’s exposures are broader

than the liabilities presented on the Balance Sheet. The government’s future social insurance exposures (e.g., Medicare and

Social Security) as well as other fiscal projections, commitments and contingencies, are reported in separate statements and

disclosures. This information is discussed later in this MD&A section, the financial statements, and RSI sections of this