RESOURCE FOR DANCERS AND TEACHERS

Nutrition Resource Paper

JASMINE CHALLIS RD, AND ADRIENNE STEVENS EDD, WITH THE IADMS DANCE EDUCATORS’

COMMITTEE, 2016, AND UPDATED IN 2019

CONTENTS:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. FOOD AND DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS

3. FLUID, HYDRATION, AND SWEAT

4. RECOMMENDED READING

5. REFERENCES

6. AUTHORS

2

1. INTRODUCTION

To perform at their best, dancers need to be adequately fueled for the activities in which

they participate regularly: classes, rehearsals, and performances/competitions. This paper

will present concise and practical strategies regarding the types and amounts of food that

are needed to sustain health across the variety of activities dancers participate in,

specifically addressing a balance of nutrients: carbohydrates, fats, proteins,

micronutrients and fluids. In addition, it will stress the practical assessment of food in

context to the amount of energy exerted in relation to rest and recovery rather than

focusing on calories alone. With this in mind, we propose that dancers develop greater

self-awareness of these important components when considering food choices and

timing: amount of time spent dancing, intensity, type of dance activity, individual

metabolic variation, access to food and cooking, and personal goals.

Adequate nutrition is intricately tied to every aspect of physiology and health. To that

point, weight management is often on many dancers’ minds and can end up dominating

thinking in an unhelpful way. Being clinically underweight or overweight can trigger

emotional issues or bone, hormonal, and metabolic abnormalities that can last a lifetime.

1

In contrast, in addressing this approach, this paper stresses the importance of health and

fitness recognizing how nutrition fits into dancers’ lives. Because each dancer is different,

individualized approaches to diet, goals, and dance aesthetic must be taken into

consideration.

GETTING THE FACTS

As a population, dancers often obtain eating and dietary advice from various sources that

are not always credible, and instead take recommendations made by celebrities, the

media, and from word of mouth. Often, nutritional advice by qualified healthcare

professionals is not sought out.

2

Wherever possible, food and eating recommendations

should be obtained from credible sources based on current medical and scientific data

and this information should be evaluated by the dancer. Dietitians (or notably, Sports

Dietitians) are the most specifically qualified experts in this field. Diets that promote rapid

3

weight loss and typically exclude major food groups or require the addition of herbs and

supplements, are likely to impair performance, are not sustainable, can be harmful to

health, and should not be followed. In addition, self-proclaimed experts who advertise

commercial products hyped to produce large and rapid gains in muscle mass, stimulate

metabolism, or provide energy, should be considered with skepticism.

Some of the characteristics that define dance training include the ability to apply

intelligence, discipline, self-discovery, and focus. In striving for excellence however,

dancers often take an ‘all or nothing’ approach, thinking that if rules are obeyed to the

letter they will be better performers, have better technical skills, be thinner, healthier, or be

better individuals (insert any superlative here). Dancers are bombarded with media

information and jargon that may not pertain to their needs. Unfortunately, dancers often

erroneously believe that if one type of food, vitamin, or exercise is good for them, much

more is better.

2

This approach can result in nutritional imbalance and is not sustainable.

While it would be easier if nutrition advice for the dancer could be presented in black and

white terms, the reality is that nutrition is not like this. Eating behavior is driven by

complex neuro-hormonal mechanisms which regulate cravings, appetite and satiety and

physiological responses to food. Dancers, like the general population, are hard-wired for

salty, sweet, and high fat foods, yet there is limited room for these foods in a dancer’s diet.

It is the combination and variety of foods which matter, and this takes work to plan. For

example, a diet made up of large amounts of vegetables and whole grains will not result in

optimal performance for most dancers, nor will one which is based only on candy and

cake. We stress that consuming a variety of foods is necessary for the body and the mind

and to remember that although food is fuel, eating should be pleasurable. Finally, global

food supply and local food issues should be researched by the dancer. Opting to eat

vegan, vegetarian, or engage in other ethical decisions around food should be choices that

are informed by both circumstance and research and this is beyond the scope of this

paper. For information on plant based diets, see: http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-

lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/vegetarian-diet/art-20046446

4

The dancer must develop a performance eating plan to navigate challenges and optimize

their condition in order for their body and mind to function at a high level. When the body

is given what it needs to function at a high level, the need for overly restrictive eating is

minimized. Since every person is different, when possible, seek out nutritional advice from

a qualified nutrition professional (such as a Sports Dietitian). As qualifications and

licensure requirements of those providing nutritional counseling is varied and differs by

country and state, research may be needed.

For information on nutrition credentialing

https://www.bda.uk.com/publications/dietitian_nutritionist.pdf

http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/nutritionist-or-dietitian-which-me

DANCERS AS PERFORMING ATHLETES

Dancers are artistic athletes. The performances they undertake can be lengthy and

physically demanding. They need to consume sufficient quantities of energy (E), or fuel,

from the major food groups to preserve metabolic function, hormonal and growth

regulation, as well as to meet the demands required by their activity. This can be difficult

to manage since the dance aesthetic is generally leaner for both men and women

compared to non-dancer standards. For example, body size is frequently defined relative

to body mass index (BMI). There are many web-based tools that can calculate one’s BMI

based on knowing and inputting one’s height and weight. BMI is a ratio of height to

weight, with the normal range for adults between 20-25 kg/m2. This range represents the

optimum for long term health as derived from large scale population health data

suggesting that adults within this range carry a lower risk of chronic and debilitating

diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, etc.) compared to those who are

overweight, obese, or underweight.3 A caveat of BMI, and particularly for the dancer who

has proportionally more muscle to fat, is that this measurement does not reflect body

composition. Therefore, a dancer’s weight may be high as a result of muscle, when, in

reality, the proportion of weight attributable to fat is low. In non-dancer/athletes, normal

adults with a BMI below 17 usually translates to lower body fat and body muscle which

can impact long term health, whereas a BMI over 30 in most cases indicates excess body

fat which negatively impacts health. Since BMI scores are calculated differently for adults

5

and children, dancers below the age of 18 should consult growth charts, or a medical

professional who can make an accurate assessment of growth and body size, to verify

age-related ranges for BMI.

To calculate BMI: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmi-m.htm

Link to growth charts: http://www.infantchart.com/child/

DIETING VERSUS A HEALTHY BODY WEIGHT

There are intrinsic and extrinsic variables in maintaining a healthy body weight. Dancers

are bombarded by conflicting information that they must sort through. A dancer cannot

control expectations of the dance aesthetic or cultural views about ideal body types.

Body type is individual, and body composition is primarily determined by one’s genetic

profile. Dancers should be encouraged to look at the frame sizes of close family to see

how to best work with their body, rather than against it, in order to have a fit, healthy and

sustainable dancer’s body. Maintaining health and the ability to function well is most

critical. Dancers can control their food intake and calculate their energy expenditure.

Dancers can control the way that sleep affects their performance. Sleep is an important

component of appetite regulation, and lack of sleep can make it difficult to avoid

excessive hunger as the body looks for energy.

There are many diets, supplements and tools that are promoted by celebrities, pop artists,

athletes, and even famous doctors in social and traditional media that boast exaggerated

claims to enhance performance, promote muscle mass, decrease body weight, take away

hunger, etc. Many of these claims are not validated by scientific research in humans or

regulated for safety and purity by government drug agencies, and can range from mildly

effective to ineffective, dangerous, and/or a waste of hard-earned money. There is no

magic pill to produce quick health results and promises that sound too good to be true are

usually not. Any changes to body composition will need to be made over weeks to months,

not in a few days.

6

DISORDERED EATING

Unfortunately, disordered eating and eating disorders are common in dancers. Dancers

are advised to consult a specialist for a personalized plan or program in the attempt to

lose or gain weight. Disordered eating can be described as any eating or food-related

experiences or behaviors that impacts negatively on a person’s health or wellbeing.

Engaging in disordered eating behavior is not necessarily diagnostic of having an eating

disorder, but there can be many similarities or overlapping factors at play.

Some examples of disordered eating are:

• Applying all-or-nothing “rules” around eating that are stressful or difficult to

manage or maintain over time

• Avoiding eating with others

• Going for long periods of time without eating or deliberately skipping meals

• Counting calories, or grams of food in a way that is unhelpful, stressful, or

extremely regimented

• Feeling guilt or shame around food or eating

• Feeling anxious around food or eating

The most defining characteristic of eating disorders are the eating behaviors, rather than

body size. Seeking support or help for an eating disorder from qualified and experienced

professionals is absolutely critical, particularly for dancers who are looking to continue

dancing and take care of their bodies in a more positive and healthy way.

4

If you suspect a friend of having an eating disorder, don’t stay silent! Tell a teacher, parent,

or someone with authority that can help. You can save a life.

For more information please see National Eating Disorder websites:

UK: http://www.b-eat.co.uk

US: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/

AUS: www.nedc.com.au/

7

THE DANCE AESTHETIC

Each type of dancing has its own body ideal, with female ballet dancers typically having

the lowest body weight compared to most other dance forms. A vast amount of literature,

anecdotal reports, and portrayals in books and film illustrates the risk that dancers face in

pursuing thinness, resulting in disordered eating. Studies in dancers, models, and athletes

have shown a higher prevalence of eating disorders and poor body image compared to

individuals who do not partake in these activities. Recently, more information has

emerged documenting eating disorders in men.

1

Thus the prevention of eating disorders

should be equally targeted at men and women. Because a dancer relies on their body,

optimal physical training balanced with good nutritional practice allows the dancer to train

and perform at their best. Maintaining health by achieving this balance is essential both in

the short term and all throughout the dancer’s career. Fortunately, this is a concern in the

dance world as well. For example, prestigious competitions such as the Prix de Lausanne

have set minimum safe weights that dancers must be above in order to participate.

5

FINDING THE RIGHT BALANCE

A number of factors should be considered in the recommendation of a nutritionally-

balanced plan for dancers including type of training frequency and intensity, timing of

eating in relation to activity, health and body weight goals. Although dancers spend much

time perfecting their craft and exerting energy in the studio, stage or in rehearsal, in

actuality, the amount of energy expenditure (EE) and metabolic demand is frequently

lower than they assume.

6

For example, the demands of a ballet class which requires

extreme concentration, effort, and endurance in a standing position at the barre or during

center work, frequently are aerobically low. These combined elements can cause muscle

soreness and fatigue, and while perceived as major exertion, metabolic demand is low and

very few calories are burned in the process. The intensity and frequency of classes will

determine the dancer’s nutritional requirements. Some dance styles, however, such as

Irish, tap or jazz, do include high intensity long routines which may be more energy-

8

demanding. Therefore the basic tenets of physical activity assessment begin with

awareness of quantitative and qualitative factors. While there is individual variability

around an average, to evaluate the type of metabolic demands based on activity, dancers

should assess their frequency, intensity, timing, and the type of training (FITT), a common

exercise science assessment. Beyond this, however, we know that the body has a

requirement for maintaining physical and brain function.

7, 8

Aerobic activity improves or is intended to improve the efficiency of the body’s ability to

produce energy through the utilization of carbohydrate and free fatty acids (FFA) as its

main fuel source. An increase in aerobic capacity allows a greater utilization of FFA during

low to moderate dance activity thereby sparing carbohydrate for high intensity activities.

These systemic responses protect the body against more serious disease, build

endurance, enhance glucose metabolism, help maintain normal weight and improve sense

of well-being.

Anaerobic activity is high intensity and is used in short duration exercise bursts. This type

of training often produces lactate resulting in fatigue. For more information, see the

IADMS Resource paper on Dance Fitness: https://www.iadms.org/?303

Determining energy expenditure (A FITT SELF-Test)

Frequency: How many classes/rehearsals/performances/supplemental training bouts/per

day?

Intensity: How hard am I physically working? Does the activity increase heart rate and

cause rapid breathing? Examples: Petite allegro, jumps across the floor, fast turning

combined with leaps and covering a large amount of space.

Does the activity require sustained muscular strength without much movement?

Examples: Most barre work, center adagio.

Timing: How much time (minutes/hours) is spent dancing?

How long are the activities sustained? For dancers, this can vary by the type of class.

Training: Different types of dancing require different energy needs.

9

Different styles require either whole body activation or just fancy footwork. In general, the

more body parts are involved combined with accelerated breathing rates, the more

aerobically demanding.

Examples: Rapid tap dancing or break dancing compared to a Sarabande or slow waltz.

FEMALE ATHLETE TRIAD AND RELATIVE ENERGY DEFICIENCY IN SPORT

The Female Athlete Triad (“The Triad”) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) are

of great concern in sports but also are important topics for dancers and dance educators.

The Triad is a medical condition first described over 30 years ago, seen in physically

active girls and women characterized by low energy availability with or without disordered

eating, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density. When one or more of the

three Triad components is detected, early intervention is essential to prevent its

progression.

9

RED-S refers to impaired physiological and psychological function caused

by low energy availability (LEA). LEA, which underpins the concept of RED-S, is a

mismatch between a dancer’s energy intake (diet) and the energy expended in exercise,

leaving inadequate energy to support the functions required by the body to maintain

optimal health and performance. I RED-S includes the menstrual dysfunction and low

bone mineral density affecting only women identified in The Triad, together with the

impact of low energy availability on many other body systems, including the digestive

system, the immune system, the musculoskeletal systems and the hormonal systems all

of which can affect both men and women . The consequence is that this energy

imbalance affects health, growth, repair as well as daily living and sporting activities.

10

There is acceptance that more research is needed in this field, but the 2018 update is very

clear that the consequences of low energy availability can be severe and that this is a

condition which needs careful management to prevent long term consequences.

2. FOOD AND DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

DANCERS

The recommendations below offer basic guidelines which have been adapted from sports

nutrition research. A specialist should be consulted for a personalized nutrition

10

prescription. Remember that a dancer’s needs are unique and sometimes nutritional

choices are influenced by medical conditions. In general, the energy in a dancer’s diet

should be composed of about 55%-60% carbohydrates (CHO), 12%-15% proteins (P) and

20%-30% fats (F). CHO, F, and P are necessary components the human body needs to

maintain normal physiologic function. All dancers need to ingest sufficient energy to

meet the rigors of training. Consuming the right amounts and types of food and fluid will

provide the body with the “high performance fuel” necessary to achieve optimal training

benefits and peak performance. Because every person is different, many factors including

food intolerances, allergies, cultural and religious reasons affecting food choice must be

taken into consideration when devising any dietary program. Not only is what a dancer

eats important, but when and how much needs to be critically evaluated as well.

Recommendations for dancers vary slightly compared to non-athletic adults whose intake

would be more varied: 45%–65% CHO, 20%–35% F, and 10%–35% P. Protein is

recommended in absolute amounts. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for

protein is 46g/day for women and 56 g/day for men or 0.8 g/kg body weight of P

(1kg=2.2lb).

11

Female dancers are advised to aim for 1g protein per kg body weight, while

male dancers should aim for 1.5g protein per kg body weight and up to 2g per kg body

weight if aiming to increase muscle mass. For more information on carbohydrates,

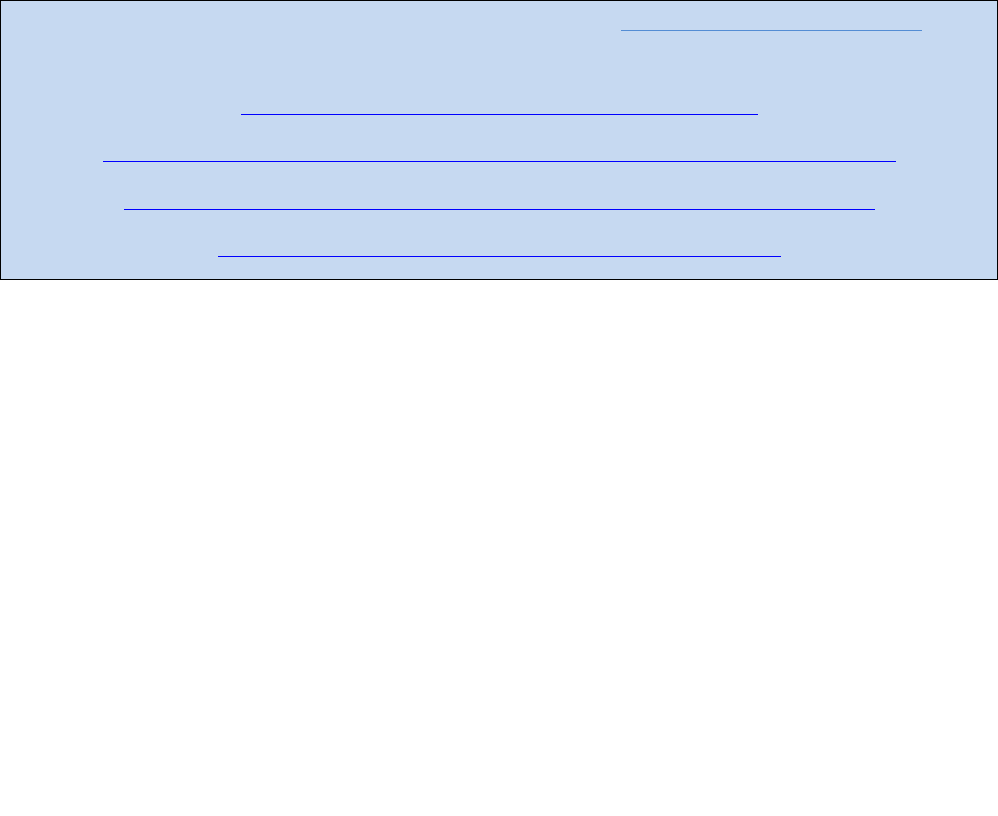

CHO 55%

Fats 20-30%

Protein

12-15%

Dancers' Nutrient Balance

Carbohydrates- preferably from

wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, beans,

lentils and dairy rather than sugary food

Fats- best from oils, nuts and seeds

rather than cakes, pastries and snack

foods

Protein- a wide range of proteins from

meat, fish, eggs, dairy and plant based

sources rather than meat pies, sausage

rolls and low quality veggie burgers

11

proteins and fats scroll down through the paper. Each section contains reference charts

with recommended amounts for typical foods in the group.

In addition, reading food labels or using nutrition apps can help roughly calculate the day’s

nutrients. Limiting or restricting any macronutrient [fats, proteins or carbohydrates] group

decreases feelings of fullness (satiety), both during the meal and thereafter. A

combination of each nutrient in the right proportion is best in order for the correct

signaling between the body and brain to occur. Each nutrient has a unique contribution to

the body so over- or under- consuming one or another nutrient is not beneficial. On the

other hand, under consumption of food is detrimental to bone health as well as energy

levels.

Use this link for information on variety of proteins from various food sources:

http://www.choosemyplate.gov/protein-foods

Carbohydrates: How much do you need?

https://www.sportaus.gov.au/ais/nutrition

CARBODYDRATES

Glucose (simple sugar) is the sole fuel for the brain and a major fuel, together with

glycogen, in the muscles. CHO are broken down into glucose in the digestive tract to be

used to maintain blood sugar levels, to fuel the brain and are also stored in muscle (350g

to 400g) and in the liver (100g) in the form of glycogen. However, the body storage of

glucose (glycogen) is limited and sugars are converted to fat when the reserves are filled.

CHO supply is critical for strength and endurance.

Not all CHOs and sugars have equivalent nutritional value. Dancers tend to think that all

CHO and sugars are inherently bad, are the source of empty calories (i.e. calories with no

vitamins, minerals, or protein) and cause weight gain, but this is not true. Many foods

contain CHO, in the form of starches and sugars found naturally within the food. Those

foods where the CHO (whether sugar or starch) is more processed, for example, white

12

bread, white rice, cookies/biscuits, fruit juice, sweets, sweet drinks, and chocolate, are

generally less helpful to dancers than those which are less processed. The more the food

is processed, the fewer the micronutrients it contains. More processed foods contain

fewer micronutrients and are easier to over consume. Nutrient dense foods sustain

energy and physiologic processes better over time. Dancers are advised to be careful

about consuming too few CHO when they are in rigorous training or performance as

insufficient CHO consumption compromises the ability to sustain energy which

contributes to fatigue. As a guide dancers will typically need between 4 and 8 grams of

carbohydrate per kg body weight. This will vary according to the duration and intensity of

the workload, and at times may be even higher (during long or intense rehearsals or

demanding pieces).

12

TABLE I: FOODS RICH IN CARBOHYDRATES

TABLE 1: FOODS RICH IN CARBOHYDRATES

Food

Type of CHO

Benefits

Recommendations

Portion

size

Bread, breakfast

cereals including

oatmeal, instant

oatmeal or

porridge, muesli

and granola, rice

Combination of

slowly digestible

and rapidly

digestible starch

with small

amounts of

natural sugars

(plus added

sugars in most

cereals).

Whole grain types

contain more

vitamins, minerals

and fiber than

white versions and

generally digest

more slowly,

helping keep blood

glucose levels

stable. Finely

ground oats are

digested faster.

Muesli and

granola can vary

in sugar content.

Best to choose

one without added

sugar.

75g-125g

bread

45g-75g

cereal/rice

Pasta, including

whole wheat and

those with

additions such as

spinach or tomato

Higher proportion

of slowly

digestible starch

than foods in box

above.

Whole grain pasta

has a higher

amount of fiber

and B vitamins. All

pasta is digested

more slowly than

many other CHO

rich foods.

A good choice;

check portion

sizes.

45g-75g dry

weight

White potatoes,

sweet potatoes

Combination of

slowly digestible

New/baby

potatoes and

Avoid chips,

french fries, or

180g-300g

13

and rapidly

digestible starch

with small

amounts of

natural sugars.

sweet potatoes are

best for slow

release of energy.

roasted potatoes

as they can be

high in fat.

Root vegetables

including

parsnips, carrots,

turnips

All have much less

carbohydrate than

potato. Parsnip

and beetroot have

50% CHO as found

in potato.

These supply a

range of vitamins

and chemicals

helpful to long-

term health.

Include as wide a

range of

vegetables as

possible.

60g+

Beans and lentils

Slowly digestible

starches,

negligible sugars.

Good source of

protein also.

Provides a number

of vitamins and

minerals including

iron.

Include regularly if

digestion allows.

If using for both

protein and CHO,

large portions will

be needed.

60g

dry/190g

cooked-

100g

dry/320g

cooked

Quinoa

Combination of

slowly digestible

and rapidly

digestible starch

with small

amounts of

natural sugars.

Slightly higher

content of protein

compared to with

many grains. The

slow release of

CHO is to sustain

energy levels over

time.

Often expensive

so use as part of a

variety of CHO.

45g-75g dry

weight

Fruit

Combination of

glucose, fructose

and sucrose.

2-3 whole fruit per

day supply natural

CHO, fiber,

vitamins and

minerals.

Whole fruits

provide better

alternatives to

fruit juices, which

should be limited.

1 whole

fruit

approx.

120g

Milk, yogurt

including Greek

yogurt and Greek

style yogurt

Natural milk sugar,

lactose,

sweetened yogurt

have added

sucrose.

Good source of

calcium and

protein.

Choose

unsweetened

yogurt and add

fruit and nuts for

best nutrition.

200ml milk

(1 medium

glass)

150-180g

yogurt (1

cup)

Cakes,

cookies/biscuits,

sweets,

chocolate,

sweetened drinks,

both carbonated

and still/non-

carbonated,

liquid yogurt

drinks

Starch/Sugars, of

which most is

added refined

sucrose.

Likely to result in

rapid increases in

blood glucose

levels which will

not be sustained

and can contribute

to acne.

They lack other

nutrients and are

poor choices to

maintain energy

needed for

dancing.

14

FAT

Why do we need fat? A mix of fat and glucose is needed for energy during exercise and at

rest. Dietary fat is essential for the regulation of multiple physiologic systems; it is needed

for the absorption of fat soluble vitamins, and is an important fuel for muscles. Fat is

stored in the body in muscle and adipose (fat) tissue in the form of triglycerides which are

broken down during exercise into fatty acids that produce energy for muscles. Fat is the

primary fuel used in aerobic exercise. Accordingly, one needs fat to burn fat. Fat should

be consumed in moderation so the dancer can meet their carbohydrate needs. Excessive

fat intake at a given meal will have a negative impact on the dancer’s ability to perform

fully in class right after the meal as it sits in the stomach for several hours.

Like CHO, however, not all fat from food is the same. Fat can be derived from either

animal or plant sources. A cheeseburger with bacon and french fries has a completely

different nutrient profile than a meal that includes salmon, brown rice and a salad with

avocado. All fats have high calories and can contribute to weight gain if not eaten in

moderation; therefore it is important to consider how much fat is eaten on a regular basis.

A diet too low in fat can have serious health consequences and ultimately impair

performance.

Fats can broadly be divided into saturated and unsaturated based on their chemical

structure. While unsaturated fats tend to be found in fish, nuts and seeds, and other plant

sources, saturated fats tend to be found in foods of animal origin as well as some

manufactured foods. Diets high in some types of saturated fats and/or trans-fats have

been shown to contribute to heart disease and cancer.

13

Processed or fast foods tend to be high in trans-fats and many countries have public

health campaigns underway to reduce trans-fatty acid contents in foods. The US FDA has

banned trans-fat ingredients from foods. This change will take place within the next few

years. Restricting trans-fatty acid intake with continued emphasis on restricting saturated

fat intake is recommended.

14, 15, 16

While many dancers consume cheeses and full fat dairy products to obtain essential

nutrients, these should be consumed in moderation knowing that dairy products also are

high in fat. Again, balance is recommended. Foods high in the omega fats play a role in

overall cardiovascular health, brain function, and mood. An array of omega-3 and 6 fats

are essential to a balanced diet; good sources of omega-3 fats are derived from oily fish,

some nuts, linseed/flaxseed oil, and canola oil, whereas omega-6 fats may be found in

15

vegetable oils. Diets high in the omega fats are beneficial to cholesterol management and

heart health.

17

Research on fat is active and guidance in this area is likely to change. The amount of daily

fat needed is approximately 1g per kg body weight, which means that a 50kg female

dancer (110 pounds) should eat 45-50g fat over the course of a day, while a 70kg male

dancer (154 pounds) should consume around 65-70g fat each day. However, if the dietary

goal is weight loss then amounts may need to be lower.

TABLE 2: SOURCES OF FATS

TABLE 2: SOURCES OF FATS

Food

Amount

Fat

conten

t (g)

Notes

Recommendations

Oil, e.g. olive

oil

1 level tsp.

or 5ml

5g

Mainly

monounsaturated.

Use regularly.

Nuts and

seeds

1 tbsp. or

15g

10g

Unsaturated and also

supply vitamins and

minerals.

Limit portion size.

Oily fish, e.g.

Salmon

(grilled)

Average

serving

approx.

100g

13g

Mainly unsaturated.

Include 2 portions

per week if possible.

Avocado (1/2

large)

100g

8g

Mainly unsaturated.

Treat as a fat source

if including

regularly.

Butter

1 level tsp.

or 5ml

4g

More saturated than

unsaturated.

Keep to small

amounts.

Nut butter

1 small

spoon or

10ml

5g

Mainly unsaturated, fair

source of protein.

Watch portion sizes.

Milk – whole

100ml

4g

Mainly saturated – but

may not have the health

risks of other saturated

fats.

Use semi-skimmed

for best balance of

fats and CHO.

Milk- semi-

skimmed/1-

2% fat

100ml

1-2g

Lower amount as total

fat is lower. Good

source of protein,

Include 2-3 servings

of milk/yogurt daily.

16

PROTEIN

calcium and other

nutrients.

Cheddar

(hard) cheese

1 slice or

25g

Mainly saturated but

good source of calcium

and protein.

Make sure a variety

of protein rich foods

are used.

Mayonnaise

1 tbsp. or

15g

11g

Mainly unsaturated,

depending on oil used.

Limit portion size

and check amounts

in ready-made

sandwiches.

Salad

dressing

1 tbsp. or

15ml

0-11g

Many brands/recipes –

some are fat-free but

may have sugar in

instead of oil.

Use in small

amounts.

Thick/double

cream

1 tbsp. or

15g

8g

Mainly saturated.

For occasional use.

Salami

1 slice or

10g

4g

Mixture of fats, high fat,

also high salt and

preservatives but good

source of protein.

For occasional use.

Potato crisps

(UK)/chips

(USA)

Small bag

or 25g

9g

Mainly unsaturated.

Not part of a

performance eating

plan.

Cake

1 slice or

60g

6-12g

approx

.

Mixture of fats; contains

some good nutrients but

usually high in calories.

For occasional use.

Biscuits/cook

ies

2 bourbon

cream (24g)

2 packaged

chocolate

chip

cookies

6g

Mixture of fats, energy

dense and easy to

overeat.

Keep for occasional

use.

Chocolate

Small bar

approx. 50g

15g

Mainly saturated fat.

Limit to high cocoa

(dark chocolate) content

which has more

minerals.

Limit portion size.

Pastry (in

pies)

50g

approx

. 16g

Varied fat content, high

fat to CHO ratio.

Keep for occasional

use.

17

Protein is a macronutrient and is composed of amino acids, some essential (cannot be

made in the human body) and other non-essential (can be made in the body). Amino acids

are responsible for the growth of every component and maintenance of every basic

function in the human body. Amino acids are used as supplemental fuel to CHO and F

(especially when energy supply is insufficient). From the dancer’s perspective the

importance of protein is its role in repairing muscle fibers that are stressed by constant

use in dancing and related activities. Protein is also necessary for bone health.

Protein needs are based on body weight rather than on energy requirements for activity.

Essential amino acids have to be supplied by food sources which can be derived from

either animal or plant sources. Animal proteins provide the most complete array of amino

acids, have a higher satiating effect and are more filling because they take longer to

digest.

10

Diets higher in protein preserve lean body mass during weight loss.

18

Dancers

and athletes are sometimes under the impression that consuming protein powders as a

supplement will give them a performance edge or serve as a meal replacement that could

be better than food. There is no magic to protein supplements – they deliver good quality

protein -- nothing more or less. If considering the addition of commercial protein powders,

dancers are advised to understand why they are taking them and to verify that the

supplements actually contain the ingredients as advertised on the label. Information on

purity, safety and contamination guidelines for protein powders can be found online at

www.informed-sport.com.

18

Photo credit: Jasmine Challis

TABLE 3: SOURCES OF PROTEIN

TABLE 3: SOURCES OF PROTEIN

Animal proteins

Portion size

Protein amount

Chicken, turkey, pork, fish

(salmon, tuna)

100g cooked (fish lower than

meat) Typical portion size is

100g-150g

20g-30g (fish lower

than meat)

Eggs

2 eggs

3 eggs

12g-14g

18g-21g

Cottage cheese, ricotta

cheese

100g

10g-12g

Yogurt, Greek yogurt

125g (Greek yogurt has the

highest)

6g-10g

Hard cheese

50g

12g

Milk – including whey and

casein

1 cup/230ml glass

8g

Plant based proteins

Portion size

Protein amount

Quorn ® (Contains small

amount of egg)

100-150g

14g

Split peas, lentils, beans

including garbanzo, kidney

and butter beans,

chickpeas, soy beans,

edamame beans

200g ready to use

12g

Wheat gluten/seitan

Quinoa

Soy flour

Seitan 100g

Quinoa raw weight 100g

Soy flour 50g

16g

14g

18g-20g

Tofu

200g

16g

Nuts, seeds and nut

butters. These are high in

fat; therefore, vary protein

sources of protein within a

food plan

50g

Monitor consumption - check

portion size

7g-12g

Soy or Soya milk

1 cup/230ml

5g-9g

‘Milk’ from hemp, rice,

almond, coconut etc.,

other than soy are much

lower in protein, typically

0.1g/100ml therefore, not

a useful source of protein

1 cup/230ml glass

Less than 1g

19

TIMING AND DIGESTION

Scheduling food intake (eating) is almost as important as the type of food and amount

that is consumed. It is important to factor in time for food digestion. It is difficult to jump

and turn comfortably with a full stomach of steak and eggs, for example, no matter how

nutritious the meal. Ideally an interval of 2-4 hours after eating is optimum to allow

digestion to take place before dancing. However, most dancers will have to cope with

dancing while food is digesting because in the digestive process food takes at least an

hour before it leaves the stomach and moves into the small intestine where absorption

occurs. It is also nearly impossible to be adequately sustained for an entire day (with an

afternoon technique class and evening rehearsal) on an unbalanced diet, whether too little

or too much of any given nutrient. Therefore, dancers should research how to consume

the type of foods and amounts that will not decrease but increase the physical ability to

perform well. The skill is to learn how to balance timing and energy requirement.

Planning tips

Food preparation: Allocate time for grocery shopping, food storage, cooking, and

preparation.

Food safety: Be mindful of food temperature; use cool packs if refrigeration is not an

option.

Performance and fueling: Maximize energy pre-performance and recovery post

performance.

Vacation/Travel: Adjust nutritional requirements when you are not dancing, based on

activity.

Injury/post injury: Adjust energy intake to match output and examine balance of nutrients

to facilitate healing.

FOOD VS. VITAMINS AND SUPPLEMENTS

20

Dancers are advised to review their food plans and try to meet vitamin and mineral needs

from food. For those with restricted diets or working where food availability is limited, a

daily multivitamin and mineral supplement ensures basic requirements are met. However,

the addition of vitamin supplements at high dosage to increase performance is not

necessary, may impair recovery processes and can be toxic. The exception to this is

vitamin D which is covered in greater detail below. To obtain all important macro and

micronutrients, a balanced diet composed of a wide variety of fresh fruit and vegetables,

whole grains, dairy products, and proteins is recommended. Diets that are restrictive or

unbalanced can lead to a range of negative health consequences. Because most

individuals do not consistently eat a wide variety of foods, multivitamins are reasonable

supplements to take but should not be considered food replacements.

VITAMINS AND MINERALS: MICRONUTRIENTS

Vitamins and minerals comprise the micronutrients in the diet from a wide variety of food

and all play a key role in maintaining every system and organ in the body.

Overconsumption can be equally as dangerous as deficiency. Minerals are classified into

macro minerals and micro minerals (trace minerals). Although there is this division from a

practical point of view they may be considered together, as intakes of all of them are at

most a few grams per day (sodium and chloride), and other than calcium (around 1g per

day), well under 1 g per day. Many minerals are found in the body but only about 15 are

currently known to be essential in our diet, although ongoing research may change this

official position in the future. Iron and calcium will be discussed in more detail because of

the importance of these minerals.

TABLE 4: MINERALS: SOURCES AND FUNCTION

TABLE 4 MINERALS: SOURCES AND FUNCTION

21

Minerals most

relevant to

dance

Functional use

Common source

Potential risk when

consumed in

extreme

Sodium

Maintains normal

blood pressure and

water balance,

hormonal and

muscular function.

Usually combined with

chloride as salt –

(NaCl), generally need

to limit as easy to meet

requirements.

Table salt, baking

soda, seasonings,

canned, smoked

and salted meats

(including bacon

and sausages) and

fish, olives and

pickled foods +

processed food

(hidden salt)

Both excess and

lack of are possible:

excess results in

thirst (short term);

deficiency results in

feeling unwell.

Potassium

Maintains normal

blood pressure and

water balance, muscle

function.

Fruit and

vegetables, cereals,

meat, milk,

chocolate, coffee,

nuts

Overdose unlikely

unless potassium-

rich salt is used.

Suboptimal intake

is common but not

immediately

harmful.

Chloride

Maintains stomach

acidity and fluid

balance.

Table salt, soy

sauce; large

amounts in

processed foods;

small amounts in

milk, meats,

breads, and

vegetables

Usually combined

with sodium,

therefore, similar

consequences as

seen with sodium.

Calcium

Maintains bone health,

tooth structure, nerve

conduction, and blood

clotting.

Milk, yogurt,

cheese, fortified

soy products, nuts

and seeds, green

vegetables, dried

fruit

Calcium absorption

works in

conjunction with

vitamin D.

Absorption is

greater when intake

is lower, but bone

health may be

compromised.

Blood calcium may

rise with very high

intakes.

Phosphorous

Maintains bone/tooth

formation and energy

metabolism.

Milk, yogurt and

cheese, grains and

cereals, green

Excess/lack is

unusual unless

caused by physical

illness or use with

22

vegetables, and

meat

certain

medications.

Magnesium

Affects muscle

contraction, nerve

transmission, energy

metabolism, and bone

integrity.

Nuts and seeds;

legumes; leafy,

green vegetables;

seafood, chocolate;

artichokes

Dietary lack/excess

unlikely with normal

diet.

Iron

Maintains blood

integrity;

hemoglobin/myoglobin

formation to transport

oxygen in the body.

Ensures a healthy

immune system.

Red meat, eggs,

cereals, green

vegetables, pulses,

legumes, dried fruit

Iron deficiency is

more common in

women. Excess

unlikely except

when used with

certain dietary

supplements.

Copper

Involved in enzyme

synthesis and varied

metabolic functions

Shellfish, nuts,

meat including

offal, pulses,

legumes, cocoa

Dietary lack/excess

unlikely with a

normal diet.

Selenium

Involved as an anti-

oxidant and mediator

in electron transfer

function.

Brazil nuts, meat,

fish, seeds, whole

grains

Inadequate

amounts are

possible; excess

amounts are

unlikely unless

supplements are

used. Lack of

selenium may

trigger mood

swings and feelings

of depression.

Zinc

Prevents low mood;

allows for normal

wound healing, and

maintains immune

system function.

Meat, seafood,

green vegetables,

seeds

A lack is possible if

diet is poor. May

cause low mood,

poor wound

healing, and

suppressed

immune system.

Excess only likely

from unwise

supplement use.

Manganese

Enzyme synthesis,

enzymatic and

metabolic functions.

Whole grains, nuts,

vegetables, dried

fruit, cereals, tea

Dietary lack/excess

unlikely with normal

diet.

23

Fluoride

Tooth structure

Seafood, water, tea

Excess possible if

use of toothpaste is

high. Deficiency

unlikely.

Iodine

Thyroid function

Seafood, eggs,

dairy

Deficiency is

possible depending

on soil levels where

fruit and vegetables

are grown. Excess

results from

supplement use

only.

Chromium

Plays a role in

glucose/insulin

metabolism.

Whole grains,

legumes, lentils,

nuts, meat, dairy,

eggs

Dietary lack/excess

unlikely with normal

diet.

Cobalt

Needed as part of

Vitamin B12.

Fish, nuts, green

leafy vegetables,

cereals

Dietary lack/excess

is unlikely with

normal diet.

CALCIUM

Calcium is important in bone formation. Good bone health is vital because it is important

to lay the building blocks for bone stability later in life. During the first two and a half

decades of life, bone mass is developed but thereafter, bone formation ceases.

6, 19

It is

essential to ingest adequate calcium throughout one’s life in addition to the many other

nutrients that are required to maintain good bone health. Low bone mass and low calcium

intakes are also associated with increased risk of stress fractures. The richest source of

calcium is dairy products but generally, can be easily acquired in fortified foods and

beverages. Calcium absorption is works in conjunction with vitamin D.

IRON

Iron is an essential trace mineral and combined with hemoglobin in red blood cells

increases the oxygen capacity of blood. Iron plays an integral role to oxygen storage and

transport within the muscle cells. When iron stores are low or deficient, they can be

replenished by active iron compounds that are held in reserve in the liver, spleen, and bone

24

marrow. In the presence of iron insufficiency (anemia), general fatigue, loss of appetite,

and inability to perform mild exercise can occur. Iron is absorbed in the intestine; iron

derived from animal sources is better absorbed than that from plant sources. Dancers

should include normal amounts of iron-rich foods in their daily diet. Dancers who have

heavy menstrual periods may need iron supplementation; this need can be confirmed with

routine blood work.

19

Dancers who do not eat meat should take care to consume iron from

other sources including tuna, egg, oatmeal, dark green leafy vegetables, soy, beans, iron-

fortified breakfast cereal, and dried fruits. In the presence of a balanced diet, iron

supplements are not needed for most dancers though may be advised for some women.

VITAMINS

Vitamins are organic substances necessary to life and are divided into water soluble and

fat soluble. Water soluble vitamins are the B vitamins and vitamin C. Vitamins A, D, E, and

K are fat soluble and can be stored in the body which means that they are not required on

a daily basis but should be consumed regularly. The fat-soluble vitamin which dancers

need to focus on is Vitamin D (See Table 4). Water soluble vitamins, which are Vitamin C

and the B group, are needed daily. The B vitamins play important roles in energy

production (especially thiamin B1-riboflavin B2-niacin, B3 and B6 – pyridoxine) and in red

blood cell formation (folic acid and vitamin B12-cobalamin group). Deficiency of these

vitamins can impair performance.

Different fruits and vegetables contain different plant chemicals that can optimize

performance as well as serve as anti-oxidants. An easy way to think of this is that

different colors in fruit and vegetables represent different effects, so the dancer is well

advised to embrace the concept of ‘eating across the rainbow’. In general the orange, red,

and dark green colored fruits and vegetables supply the highest content of the vitamins A

and C. Vitamins A (beta carotene), C, and E function as antioxidants that may help prevent

cell damage during exercise and are necessary for the immune system. Smokers are

advised to focus on foods, not vitamin supplements for foods rich in anti-oxidants. While

25

more research is required, there are data that demonstrate that cancer risk in smokers is

increased by vitamin supplements (but not by food).

20

Vitamin content of food:

http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-VitaminsMinerals/

Eating across the rainbow:

http://www.medbroadcast.com/pdf/cccPDF.pdf

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/yf/foods/fn595.pdf

VITAMIN D

Many dancers are vitamin D deficient and considered an at-risk population due in part to

inadequate or limited sun exposure, increased use of sunblock, and poor diet.

21

Literature

has substantiated that some dancers are deficient in Vitamin D, especially during winter

months.

22

This deficiency reduces the ability to regenerate muscle and bone function

following stress or injury, may interfere with weight loss, and can contribute to the

development of stress fractures. Vitamin D recommendations vary largely by country but

400-2000 IU is a safe recommendation for dancers. The UK recommends between 400-

1000 IU/ 10-25 mcg, whereas the American College of Sports Medicine recommends

1000-2000 IU during the winter months, and the Australian recommendation is 600-4000

IU. Recent evidence suggests that approximately 1000 IU are needed to maintain

adequate levels of vitamin D.

22

A safe upper limit seems to be 4000 IU/100micrograms for

the USA and Europe and 3200 IU/80 micrograms for Australia. A study in which dancers

were given 2000 IU Vitamin D for 4 months yielded beneficial results. The authors also

noted however, that if blood vitamin D levels are not monitored, 1000 IU per day is

recommended.

23

This fits within a safe upper limit of 4000 IU/100micrograms (3200 IU US

and Europe recommendations and 800 micrograms from Australia). Vitamin D

supplementation has also been associated with increased vertical jump height and

isometric strength, and lower injury rates among elite ballet dancers.

21

26

It is recommended that dancers spend some time outside (at least 10 minutes per day),

with no hat, sunscreen, and sleeves rolled up to optimize Vitamin D exposure. In addition,

dancers are encouraged to seek the advice of their local medical professional regarding

the use of Vitamin D supplementation.

See also the IADMS resource paper on bone health http://www.iadms.org/?212.

For more information on supplements around the world

https://www.fda.gov/food/dietarysupplements/

http://www.nhs.uk/news/2011/05may/documents/BtH_supplements.pdf

http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/resources/sports-nutrition

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/drv.htm

SPICES

Spices and herbs have been used for centuries in medicine and health. Bioactive

compounds in herbs and spices, collectively called, dietary phenols or phytonutrients,

contain properties that have been purported to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress,

improve cardiovascular and metabolic function, cognition, gut microbiota, digestion, and

reduce risk of certain cancers. Polyphenols and polyphenol rich foods especially fruits,

vegetables, and green tea are known for their antioxidant properties. In normal amounts

they may have more of a role in overall health and maintenance than in the development

or prevention of disease (e.g. cinnamon, turmeric, etc.). In larger amounts they may

interact with medications and may have a negative effect on physiological function.

24, 25, 26

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Complementary, homeopathic, and alternative medicine treatments should be approached

with caution, and reviewed by credible sources before embarking on potentially expensive

regimens. Herbs (e.g. St. John’s Wort) and media-hyped cleanses and teas are not

27

recommended as routine practice as they can interfere with medications and create

unwanted or harmful effects even in the absence of medications. Medicinal or herbal teas

can have either diuretic or laxative properties and should not be used to modify weight.

3. FLUID, HYDRATION, AND SWEAT

When we dance or exercise, heat is generated by muscles and raises core temperature.

Within normal limits, increased core temperature as a result of dancing does not lead to

impaired thermal (heat) regulation. Exercise increases heat production in the muscles and

cooling the body is primarily dependent on the evaporation of sweat from the skin.

Perspiration is a normal body function and allows the body to regulate its ability to adapt

to exercise and hydration. The amount of sweat produced may vary by person, and a 16-50

ounce (0.5-1.5-liter) loss during moderate exercise over a one hour period is common.

With back to back classes, dancers can lose a considerable amount of water through

sweat.

Water accounts for 60% of the total weight of the human body. Dancers need to stay

hydrated; without proper hydration fatigue and injury can result. Environmental

temperature and sweat production will drive the amount of fluid needed to maintain

health. Sweat losses during training or performance from exertion can be substantial and

vary by sport and gender. Dehydration of 3% of body weight can lead to cramps, nausea,

light headedness or fainting and may severely impair performance. Adequate fluid

replacement prevents dehydration and its consequences.

27

A well-hydrated body will

produce a good volume of urine that is pale in color and does not have a strong odor. As a

self-test, drink 400-600 ml two hours before dance and check urine output over the next

hour.

28

Dancers should note that B vitamin supplements may produce a stronger yellow

color which should be considered in evaluation.

29

Since many dance environments are kept warm because dancers prefer warm

temperatures to keep their muscles malleable and often add layers of warm (breathable)

clothing, sweating has an additive effect on fluid loss. Therefore, it is vital to replace fluids

28

often. The amount of fluid loss is related to body size, mass, and genetic factors, with

highest losses from taller heavier males, and lowest losses in lighter females.

30

HYDRATION TIPS

• Stay hydrated by drinking non-sugared liquids. Don’t restrict fluids during meals or

exercise.

• Drink frequently throughout the day ‘ad lib’ or ‘to thirst’, even if not thirsty - keep a

full, non-spill bottle at hand.

• Drink more to delay hydration and diminish a rise in core temperature.

• Water is the best replacement for sweat loss as sweat is mostly water and sodium.

• Water is easy to obtain, has no additives, and is quickly absorbed.

• Sodium replacement is not necessary, but for those who sweat profusely,

electrolytes may be recommended. Salt restricted diets should only be advised for

medical reasons.

ELECTROLYTES

Electrolytes are minerals the body requires for regulating water balance, blood acidity, and

muscle function. They act as conductors within body fluid that have both positive and

negative charges that keep the body fluid in balance and play a role in every physiologic

system. The major electrolytes are located in extracellular fluid and include sodium,

potassium, calcium, and magnesium. These in turn are balanced by a host of

concentrations that reside primarily in the kidney.

31

Changes in food intake (fasting, re-

feeding, limiting calories, etc.) severely impacts water and electrolyte balance which can

elevate thirst, body weight, and water retention - conditions dancers do not want to have

fluctuating arbitrarily.

The major source of sodium in the diet is added salt. One teaspoon of salt is equal to

2,300 mg (2.3 g) of sodium. Because salt is so widely used in our food today, inattention

to the amount of sodium in one’s diet can easily lead an imbalance which can impact not

only how the body looks and feels, but how it performs as well.

29

COMMON BEVERAGES

Teas and Coffee

Coffees and teas are best consumed in moderation as caffeine is a stimulant. Moderate

intake of caffeine has been shown to enhance endurance and sports performance but can

also cause jitteriness when consumed in excess. While caffeine has mild diuretic

properties, this response is seen in people who do not regularly consume caffeine and the

effect is moderated with continued consumption.

32

As caffeine lingers in the body for

several hours it is best to limit consumption to the morning or afternoon and limit in the

early evening in order to obtain a good night’s sleep. Caffeinated drinks should not be

used to control appetite. Repackaged and commercial teas and coffees often include

unwanted high levels of sugar, sodium, calories, and artificial ingredients so always check

the ingredients.

Fruit drinks and juices

In the US, fruit juices may be fortified with vitamins and nutrients. In general, juices with

pulp are more nutritious compared to those without. On the other hand, fruit drinks can be

sources of high sugar and additives and have variable amounts of fruit juice in them.

Drinking large amounts of juice at meals and throughout the day should be avoided as it

can contribute to weight gain, may not satisfy thirst, and may make it harder to regulate

appetite. The acidity and sugar content associated with juice can have a deleterious effect

on oral health.

33

Soda

Soda and other carbonated drinks can be high in sugar and high fructose corn syrup,

artificial additives, sodium, caffeine, and contribute to tooth decay and interfere with

digestion. While drinks and sodas made with artificial sweeteners, collectively called non-

30

nutritive sweeteners, may have zero calories, it is a subject of debate within the scientific

community whether they impact the brain to perceive them as metabolically active and

interfere with weight regulation.

34, 35

There are no health benefits to soda and they are

best avoided before and during dance as the carbonation can cause stomach discomfort

and gas.

Energy & sport drinks

‘Energy’ drinks are high in caffeine, artificial additives, and sugar and offer very little

nutritional value and are therefore, not recommended for dancers. The extreme amounts

of sugar (3 teaspoons per 4 ounce or 15g per 100ml) and caffeine in these drinks can

cause excessive jitteriness, loss of focus and concentration. They can also trigger

previously unrecognized heart conditions, headache or migraine and are particularly

dangerous when mixed with alcohol as alcohol is depressant to the nervous system, and

mixed with caffeine, a stimulant. For more information, follow this link:

https://www.sportsdietitians.com.au/factsheets/children/nutrition-for-the-adolescent-

athlete/

Commercial sports drinks are often promoted as good fluid replacements during high

intensity, prolonged activities in which water and electrolytes may be radically depleted,

and where additional carbohydrates may be required. Sports drinks can be useful to

dancers with high fuel (caloric) needs (some male dancers and smaller number of female

dancers), those who perspire heavily, have a diet naturally low in salt or train in very hot

environments. These drinks are isotonic (contain a similar number of salts and

carbohydrates particles as bodily fluids) and supply approximately one teaspoon of CHO

as sugar per 4 ounce (4-6g per 100ml), plus salt, which translates to 16-24kcal per 4

ounce/ 100ml. The effect of vitamin loss in sweat in dancing is likely to be negligible.

36

As

a general rule, commercial sports drinks are not needed in dance.

Protein shakes and smoothies

31

While American audiences mostly recognize shakes as made primarily with ice cream and

syrup, this section discusses shakes in the context of those prepared with healthy

additives like protein, antioxidants, or vitamins and made from water, juice, or milk.

Smoothies and protein shakes are frequently marketed as nutritious and used as meal

replacements but can vary widely in ingredients. Smoothies and shakes should be

considered as part of a meal and not as a meal replacement. Although a smoothie can

provide several pieces of fruit, it is easy to over-consume, because it is difficult to

ascertain how much fruit is in a typical serving. Even the natural sugar in fruit can be too

much when consumed in excess. A healthier alternative is to make one’s own smoothie

and include raw vegetables. The blended fiber can be a useful part of a meal plan as well

and the addition of milk/soy milk/yogurt can make a useful recovery drink. With that in

mind, drink immediately or soon after preparing to avoid vitamin loss which ultimately

lowers the potential health benefits.

Supplement-based shakes also vary widely in their content and thus their potential

benefit. They can contain high amounts of fat and sugars and contribute little to an eating

plan. In contrast, shakes made with low fat milk or a milk substitute (soy, cashew, almond,

rice, hemp, etc.) and combined with added fruit and protein powder or dried skimmed milk

powder (if needed) are a better alternative that have more healthy ingredients and less

added sugar. Commercial milkshakes like smoothies or iced coffee drinks vary in both the

size they are sold in and their composition. Drinks made with high sugar ingredients are

not as nutrient-rich, compared to those made primarily from milk and fruit. Consider also

that frozen fruit is a great alternative and less costly when fresh fruit is unavailable.

Always check the ingredients’ labels and limit the size.

HOME- MADE SPORTS/ISOTONIC DRINK RECIPES*

Variations can be found online. Keep the ratios of ingredients in similar proportion and modify to

taste.

32

Isotonic drink based on juice concentrate, fruit squash or cordial (fruit flavored concentrates either

with sugar or sweetener) reconstituted in a ratio of around 1 part concentrate to 6 parts water.

7 oz. (200ml) ordinary juice concentrate

28 oz. (3 ½ cups) or 800ml water

Pinch of salt

Mix together in a large container and refrigerate.

Makes ~5 cups

Isotonic drink based on pure/100% fruit juice

Approximately 16 ounces (500ml) unsweetened fruit juice (orange, apple, pineapple)

Approximately 16 ounces (500ml) water

Mix together in a large container and refrigerate.

Makes 4 cups

Isotonic drink based on glucose/sugar plus flavour according to taste

3-4 tbsps. (50-70g) sugar or glucose powder

32 ounces (1 litre) warm water

Pinch of salt

Up to 7 ounces or 200ml of sugar free concentrate or 1 drink flavour packet according to

taste

Mix and refrigerate

Makes 4 cups

* Isotonic drinks have comparable salts and carbohydrates to body composition

Alcohol

Alcoholic drinks do not enhance performance and have dehydrating properties that

counteract dancers’ efforts to balance fluids. Alcohol is a toxic substance and provides no

vitamins, minerals or proteins and moderate consumption may be a cancer risk. Even

small amounts of alcohol (15 grams or 6 oz.) can increase one’s cancer risk and amounts

greater than this offset any potential benefits.

37

Mixers added to alcoholic drinks are

mostly CHO in the form of sugar which is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. When a

carbonated mixer is added, absorption rate may vary, leaving the dancer unexpectedly

vulnerable to toxicity and in extreme cases, alcohol poisoning.

Chart I: Pre/post performance meal planning

33

Chart 1: PRE/POST PERFORMANCE MEAL PLANNING

During long training

days (rehearsals,

multiple classes with

few breaks between)

1-2 hours prior to

dancing (short term

energy needed)

Following high

exertion (within 1.5

hours post

performance)

Rationale

• Maintain energy

• Prevent fatigue

• Maintain

satiety/minimize

hunger

• Provide quick

energy

• Digest quickly and

empties stomach

quickly.

• Replenish muscle

glycogen and

muscle synthesis.

• Provide energy for

the next day’s

activity.

Food

examples

• Items for meals and

snacks: e.g.

couscous/quinoa

• Bread with protein

plus vegetables,

fruit/ dried fruit with

nuts/seeds

• Cereal or protein

bar, handful of

wholegrain cereal

Fruit e.g. banana

with a few

nuts/seeds; oat

cakes with hummus

or cereal bar or

chicken/beef/egg

sandwich or natural

yogurt topped with

nuts and fruit

• Milk-based or soy

drink/shake or

yogurt with fruit.

• Follow up with

meal containing

CHO, P and some

F.

Chart 2: Sample food plan for one day

Chart 2: SAMPLE FOOD PLAN FOR ONE DAY

Meal or snack

Suggestions

Timing

Rationale

Breakfast

Oat cereal with milk,

fruit and nuts/seeds

At least 1 hour but

ideally 2 hours

before first class.

Ensures energy

supplies are going to

be steady through

the morning.

Break

Fruit – adding nuts for

more strenuous days

Any short break if a

long training day.

Tops off energy

levels especially if

the day is strenuous.

Lunch

Some protein

balanced with

carbohydrates and

fats, e.g. veg/salad,

avocado/nuts

As early as

possible in the

lunch break to

allow maximum

digestion before

Replenishes

nutrients used in the

morning and fuel for

afternoon/evening

activities.

34

the next

class/rehearsal.

Break

Fruit or nuts

Any short break if a

long training day.

Tops off energy

levels, especially if

the day is strenuous.

Dinner

Some protein

balanced with

carbohydrates and fat,

e.g. veg/salad,

avocado/nuts

As soon as

possible after last

class/rehearsal.

Facilitates ongoing

replenishment and

muscle repair.

Break

Milky drink/bowl of

cereal/herbal tea

Late

evening/before

bed.

Allows those with

higher requirements

to choose

appropriate food and

others a calming

drink before sleep.

RECOMMENDATIONS: TAKE HOME MESSAGES

• Fuel appropriately for all activities: eat breakfast soon after waking up and prior to

training.

• Seek out a variety of foods and fuel sources for optimum performance nutrition.

• Diets do not work. Healthy eating is an enjoyable lifelong process.

• Always check the ingredients’ labels and monitor portions.

• Drink water frequently and stay hydrated with meals.

• Be prepared: plan healthy meals and snacks in advance to ensure optimum energy

levels.

• Wherever possible, eat foods in their natural form rather than highly processed

alternatives.

• Prioritize sleep quality and quantity; balance rest and daily training.

80% of injury recovery is due to adequate rest, nutrition and sleep.

38

• Talk to a teacher or parent if eating behavior feels out of control.

35

4. RECOMMENDED READING

Nutrition Books – sports/dance - based:

All of the books listed below provide great information for dancers. This list is not

exhaustive but aims to provide a global selection of resources. As different books, styles

and balance of theory to practice suit different individuals, there is no “best” book; it will

be down to individual preference to adapt the information to one’s own practice.

Albers S. Eating Mindfully, 2nd ed. California: New Harbinger Publications, 2012.

Bean A. Food for Fitness: How to Eat for Maximum Performance, 4th ed. London:

Bloomsbury Sport, 2014.

Bean A. The Complete Guide to Sports Nutrition, 7th ed. London: Bloomsbury Sport,

2013.

Burke L. The Complete Guide to Food for Sports Performance, 3rd ed. Australia:

Allen & Unwin, 2010.

Burke L, Deakin V. Clinical Sports Nutrition, 5th ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill

Education, 2015.

Cardwell G. Gold Medal Nutrition, 5th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2012.

Clark N. Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guidebook, 5th ed. Champaign, IL, 2013.

Costa R. Cooking for Sport and Exercise. UK: Coventry University Enterprises, 2012.

Gibney MJ, Lanham-New SA, Cassidy A, Vorster, HH (eds.) Introduction to human

nutrition. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Jukendrop A, Gleesen M. Sports Nutrition, 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics,

2010.

Lanham-New S, Stear S, Shirreffs S, Collins A. Sport and Exercise Nutrition. Oxford:

Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Mastin Z. Nutrition for the Dancer. London: Dance Books Ltd, 2009.

36

5. REFERENCES

1. Arcelus J, Witcomb GL, Mitchell A. Prevalence of Eating Disorders amongst

Dancers: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 2014;22:

92–101. doi: 10.1002/erv.2271.

2. Brown D & Wyon M. An International Study on Dietary Supplementation Use in

Dancers. Med Probl Perform Art. 2014;29(4): 229–234.

3. Hu FB, Satija A, Manson JE. Curbing the Diabetes Pandemic: The Need for Global

Policy Solutions. JAMA. 2015;313(23):2319-2320.

4. Eating Disorders, National Institute of Health. Available at:

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml.

5. The Prix de Lausanne Health Policy. Available at:

http://www.prixdelausanne.org/competition/health-policy/

6. Manore M, Meyer NL, Thompson J. Sport nutrition for health and performance.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2009.

7. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman

DC, Swain DP. Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and Maintaining

Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in Apparently

Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. 2011 ACSM Position Stand.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334-1359. doi:

10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb.

8. Desbrow B, McCormack J, Burke LM, Cox GR, Fallon K, Hislop M, Logan R, Marino

N, Sawyer SM, Shaw, G, Star A, Vidgen H, Leveritt M. Sports Dietitians Australia

position statement: sports nutrition for the adolescent athlete. Int J Sport Nutr

Exerc Metab. 2014;24(5):570-584. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0031.

9. De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, Misra M, Williams NI, Mallinson RJ, Gibbs JC,

Olmsted M, Goolsby M, Matheson G. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition

Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete

Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012

and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br J

Sports Med. 2014;48:289. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093218

10. Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, et al IOC consensus statement on

relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med 2018;

52:687-697

11. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lemmens SG and Westerterp KR. Dietary protein – its

role in satiety, energetics, weight loss and healthy eating. Br J Nutrition.

2012;108, S105–S112. doi:10.1017/S000

37

12. Baker LB, Rollo I, Stein KW, Jeukendrup AE. Acute Effects of Carbohydrate

Supplementation on Intermittent Sports Performance. Nutrients. 2015;7, 5733-

5763; doi:10.3390/nu7075249

13. Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G. Reduction in saturated fat

intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:6. doi:

0.1002/14651858.CD011737.

14. Dawczynski C, Kleber ME, März W, Jahreis G, Lorkowski S. Saturated fatty acids

are not off the hook. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; Oct 9:S0939-

4753(15)00218-5. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.09.010.

15. Lichtenstein A. Dietary trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease risk: past and

present. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16(8):433. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0433.

16. FDA Cuts Trans Fat in Processed foods: Federal Drug Administration:

http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm372915.htm

17. Lorente-Cebrian S, Costa AG, Navas-Carretero S, Zabala M, Martinez JA, Moreno-

Aliaga MJ. Role of Omega-3 fatty acids in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and

cardiovascular diseases: A review of the evidence. J Physio and Biochem. 2013;

69: 633-651. doi: 10.1007/s13105-013-0265-4

18. Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD. Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass

loss during weight loss in athletes. Med Sci Sports Ex 2010;42(2):326-337 doi:

10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b2ef8e.

19. Burke L. Practical sports nutrition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007

20. Harvie M. Nutritional supplements and cancer: potential benefits and proven

harms. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e478-486. doi:

10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e478.

21. Wyon MA, Koutedakis Y, Wolman R, Nevil AM, Allen N. The Influence of winter

vitamin D supplements on muscle function and injury occurrence in elite ballet

dancers. J Sci Med Sport 2014; 17(1):8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.007.

22. Wolman R, Wyon MA, Koutedakis Y, Nevill AM, Eastell R, Allen N. Vitamin D status

in professional ballet dancers: winter vs. summer. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;

16(5):388-391. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.12.010.

23. Wolman R. personal communication, 2014.

24. Opara EI, Chohan M. Culinary Herbs and Spices: Their Bioactive Properties, the

Contribution of Polyphenols and the Challenges in Deducing Their True Health

Benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014; 15: 19183-19202; doi:10.3390

25. Rubi L, Motilva MJ and Romero MP. Recent Advances in Biologically Active

Compounds in Herbs and Spices: A Review of the Most Effective Antioxidant and

Anti-Inflammatory Active Principles. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53(9): 943-953

doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.574802.

38

26. Morrison J. Mealographer website

http://www.mealographer.com/food.php?action=search&order_1=high&display_n

ame_1=protein&order_2=&display_name_2=Calories&FdGrp_Desc=Spices+and+H

erbs&submit=Submit

27. Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS.

American College of Sports Medicine position stand: Exercise and fluid