WIK-Consult • Outline

Identifying

European Best Practice

in Fibre Advertising

for FTTH Council Europe

by

WIK-Consult GmbH

Rhöndorfer Str. 68

53604 Bad Honnef

Germany

26 June 2020

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 1

Contents

0 Executive summary 4

1 Context 6

2 Why is accurate advertising important, and what measures are in place to support it? 7

2.1 Rationale for accurate advertising 7

2.2 EU provisions affecting broadband advertising 8

2.2.1 General measures concerning consumer protection and fair competition 8

2.2.2 Measures specific to the electronic communications sector 9

3 Current practice 11

3.1 Approaches to advertising standards in the countries studied 11

3.2 Advertising practices, past and present 16

4 What is the impact of misleading advertising, and which approaches have proved to be

most effective in addressing it? 25

5 Policy recommendations 31

ANNEX: COUNTRY REPORTS 33

6 Denmark 34

6.1 Summary 34

6.2 Main players and technologies used 34

6.3 Advertising standards 35

6.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 36

6.5 Outcomes 37

7 France 39

8 Germany 46

9 Ireland 54

9.1 Summary 54

9.2 Main players and technologies used 54

9.3 Advertising standards 54

9.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 56

9.5 Outcomes 59

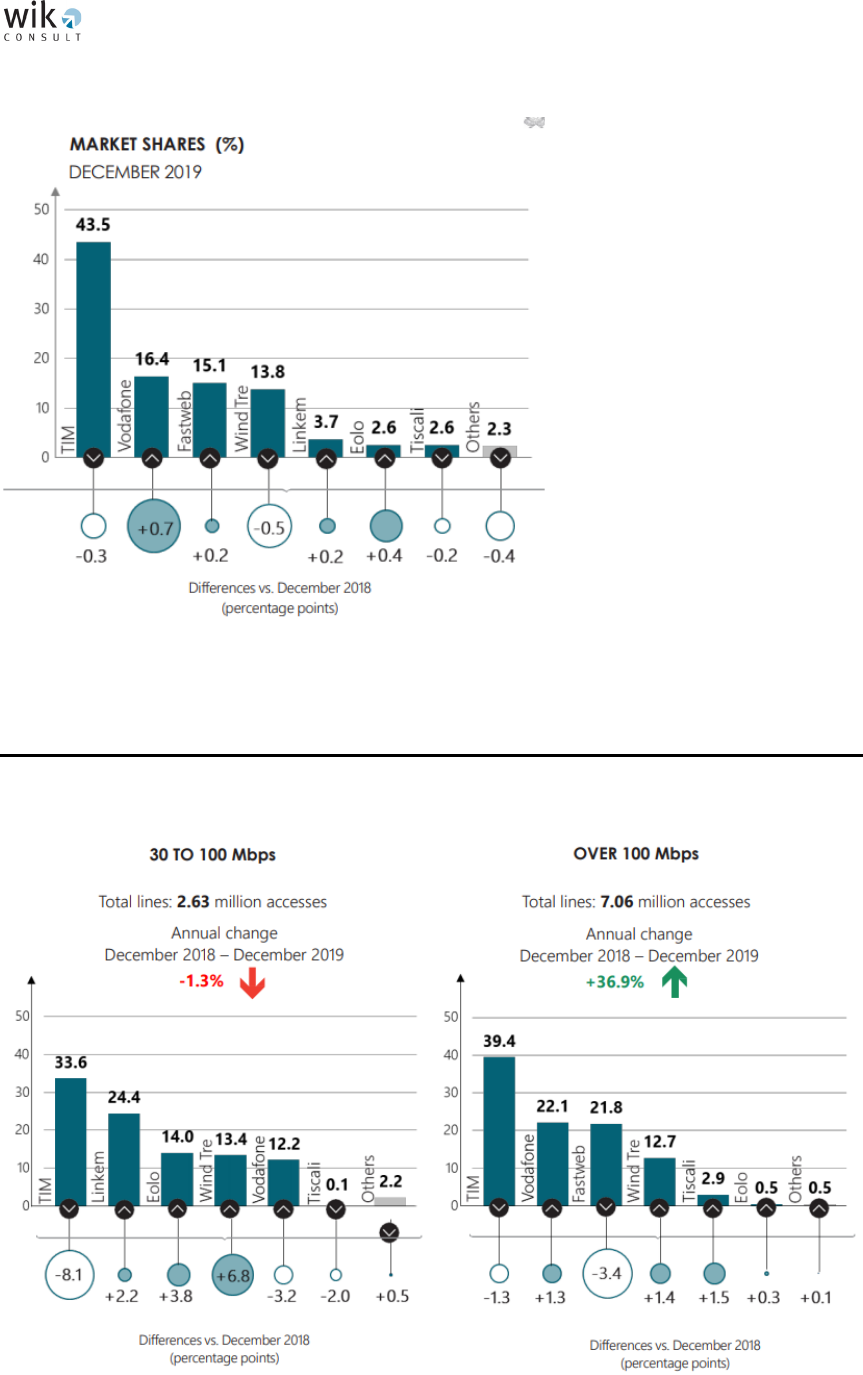

10 Italy 60

10.1 Summary 60

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 2

10.2 Main players and technologies used 60

10.3 Advertising standards 63

10.3.1 Traffic-light system for broadband products 63

10.3.2 Disputes and fines 64

10.3.3 Broadband-ready label for buildings 65

10.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 66

10.4.1 Advertising in the experimental phase of the resolution 66

10.4.2 Advertising today 67

10.5 Outcomes 71

11 Netherlands 73

11.1 Summary 73

11.2 Main players and technologies used 73

11.3 Advertising standards 74

11.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 77

11.4.1 Ziggo 77

11.4.2 KPN 79

11.5 Outcomes 80

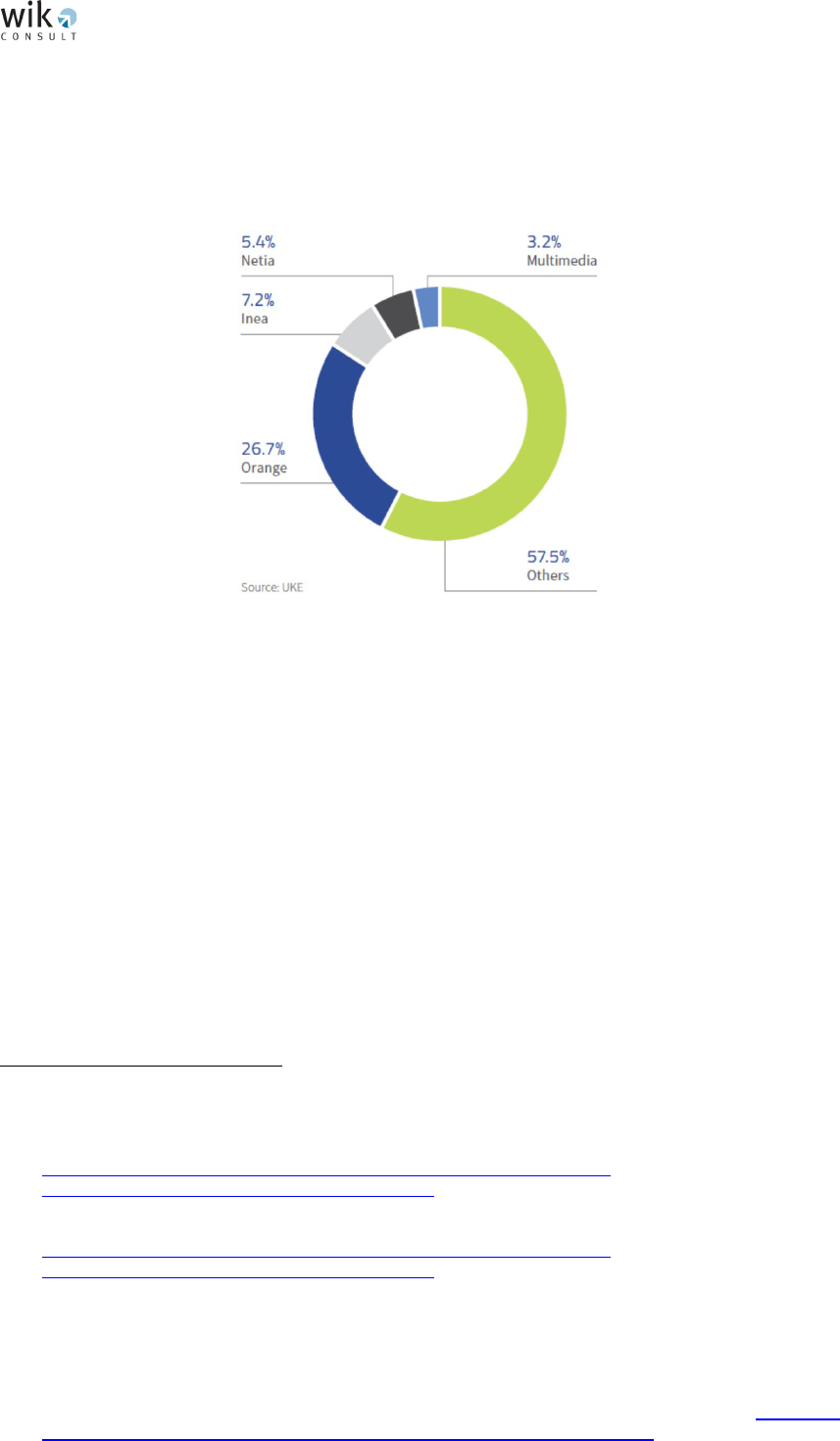

12 Poland 82

12.1 Summary 82

12.2 Main players and technologies used 82

12.3 Advertising standards 85

12.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 87

12.4.1 Advertising practice and disputes in the past 87

12.4.2 Advertising today 89

12.5 UPC Polska, Vectra, Multimedia 89

12.6 Orange Polska 91

12.7 Outcomes 95

13 UK 96

13.1 Summary 96

13.2 Main players and technologies used 96

13.3 Advertising standards 97

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 3

13.4 Advertising practice (past and present) 99

13.5 Outcomes 101

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 4

0 Executive summary

Actions have been taken in a number of countries – including France, Italy, Ireland and

the Netherlands - to address “misleading advertising” in relation to fibre. These actions,

which include legislation, regulations, guidelines and court decisions, have been justified

on the grounds that misleading advertising prevents consumers from making an informed

choice and affects competition in the market, by depriving investors in fibre of the ability

to clearly differentiate their offers from other services which do not provide the same

degree of quality and reliability.

A number of surveys confirm that European consumers are confused about the terms

used to market broadband, and find it difficult to identify which services provide the best

performance. Consumers’ focus (and the focus of advertising in several countries)

continues to rest with download speeds in many cases and these may be referenced as

“average” speeds which do not provide an accurate view of the reliability of the

connection. However, future applications and services are increasingly also likely to rely

on other characteristics that include reliability as well as low latency and upload speeds,

which are best encapsulated with reference to the technology used. Different

technologies also differ in their performance regarding energy efficiency, which is

important in meeting environmental goals.

The inclusion of a new objective in the EU Electronic Communications Code, for the

European Commission, BEREC and NRAs to foster the availability of and access to very

high capacity broadband networks, strengthens the case for transparency in broadband

marketing as fostering Very High Capacity Network (VHCN) uptake requires consumers

to be properly informed about which products meet the desired criteria and what benefits

these products confer. However, telecom regulatory authorities often have limited scope

to address issues of awareness and advertising. Meanwhile, Advertising Standards

Authorities (ASA), which do have competence over advertising may have limited

understanding of the wider implications of different technological solutions for broadband,

and no mandate to promote the objective of fostering investment in, and take-up of,

VHCN.

A review of the schemes that have been introduced around Europe, clearly demonstrate

that the strongest and most effective forward-looking interventions in the market have

been driven by the National Regulatory Authority or Digital/Telecom Ministry of the

country in question rather than the ASA. In contrast, while their impact can be significant,

few competition authorities have intervened in this area, and their decisions concern

specific cases.

Our review suggests that the clearest and most user-friendly approach could be the

introduction of a labelling scheme, similar to the traffic light scheme introduced in Italy by

AGCOM in 2018, whereby technologies with differing characteristics would be colour

coded. This would enable customers to clearly compare broadband services in terms of

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 5

their performance and, potentially, environmental characteristics. A coding system which

distinguishes between FTTH, FTTB and cable-based services, FTTC/NGA FWA and

ADSL would best meet the need to distinguish the different technologies that have been

deployed across the EU.

Such a scheme could be applied in a similar manner to current labelling applied for energy

efficiency.

The approach taken in France where only ISPs delivering fibre into the home or premises

are permitted to use the term ‘fibre’ in advertising materials is another model that has

merit in its simplicity.

Guidelines could be considered at EU level to foster the involvement of NRAs and/or

Ministries across Europe and better align policy approaches to advertising broadband

with the objectives established under the Code. Legislative action could also be

considered, such as the introduction of a mandatory labelling scheme for broadband

covering performance and potentially environment characteristics.

In order to avoid problems seen in Italy concerning advertising of products which are not

widely available, in addition to specifying the design of the label and associated criteria,

guidelines should also be provided which ensure that customers are informed when

certain products are not widely available, and what the alternative options are.

We recommend further analysis based on consumer research to confirm the design and

validate the effectiveness of the chosen scheme that could be promoted through

guidelines and/or legislation.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 6

1 Context

Many of the countries which have achieved limited success with FTTH thus far are

characterized by significant FTTC and/or cable coverage.

One of the factors that may have been hampering FTTH take-up and the business case

for deployment in these countries may be a lack of awareness by consumers of the

difference between the capabilities of FTTC vs FTTH infrastructure. This may have been

exacerbated in some countries by a lack of advertising standards which require the

differences between products to be clearly explained.

Advertising authoritities have been prompted to investigate this issue in a number of

countries but these authorities are bound by different objectives than those which govern

electronic communications regulation, and thus may not have a mandate to make

decisions which facilitate the transition to very high capacity networks. .

The impact of misleading advertising could be increased as there is evidence to suggest

fibre may be an experience good (that customers appreciate more over time, which is

possible only once their have experienced it), and as VHC broadband is understood to

have wider economic, social and environmental benefits.”.

In this study, we provide a synopsis of the measures taken in selected European member

states to combat misleading advertising and identify the most effective solutions. We also

discuss the drivers of the decision taken in different countries, the timing of the action,

and discuss the effects on FTTH deployment and take-up of misleading advertising.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 7

2 Why is accurate advertising important, and what measures are in

place to support it?

In this chapter, we discuss the rationale for ensuring accurate advertising, and summarise

the provisions in place at EU level that aim to ensure that misleading advertising is

addressed and that appropriate labels are used.

2.1 Rationale for accurate advertising

Action against misleading advertising has been justified at EU level as well as on a

national level on the basis that it directly harms consumers’ economic interests and

thereby indirectly harms the economic interests of legitimate competitiors.

1

Effects on

competitors could for example include restricting market demand, thereby undermining

the business case of operators seeking to invest.

Measures to combat misleading advertising are especially relevant in the context of

broadband, as the primary mechanism that has been used to support consumer welfare

in this market is competition,

2

and in the absence of clear and accurate comparative

information, consumers are unable to make an informed choice.

Moreover, following the transposition of the EECC, NRAs will be given a new objective

“to promote connectivity and access to, and take-up of, very high capacity networks,

including fixed, mobile and wireless networks (VHCN), by all citizens and businesses of

the Union”.

3

This objective was added, on the basis of evidence from literature and

econometric analysis that suggests that take-up of higher speed broadband supports

economic growth, as well as supporting jobs and services in more remote regions. The

relevance of fibre in the context of the definition of VHC networks concerns not only its

ability to offer higher bandwidths, but also lower fault rates and lower latency, which are

critical to the delivery of next generation services including those offered via 5G networks.

, Thus, the misuse of the term ‘fibre’ in advertising may not only affect outcomes regarding

broadband speed but also limit consumers’ potential to benefit from an infrastructure

which has a range of characteristics that may be central to future services delivery.

Moreover, fibre-based broadband was found to be more energy-efficient and therefore

environmentally sustainable than legacy copper and cable-based solutions.

4

Supporting deployment and take-up of very high capacity networks in an environment

where there are multiple services available at differing quality levels, will of necessity

1 Recital 6 UCPD

2 Article 3.2(d) of the EECC notes that a core objective of the legislation is to promote the interests of the

citizens of the Union, by ensuring connectivity and the widespread availability and take-up of very high

capacity networks, including fixed, mobile and wireless networks, and of electronic communications

services, by enabling maximum benefits in terms of choice, price and quality on the basis of effective

competition

3 Article 3.2(a) EECC

4 See WIK, Ecorys, VVA (2016) for the EC Support for the preparation of the impact assessment

accompanying the review of the regulatory framework for e-communications

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2984b37b-9aa6-11e6-868c-01aa75ed71a1

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 8

require knowledge by citizens and businesses about which networks are “very high

capacity”, and what benefits this confers.

2.2 EU provisions affecting broadband advertising

2.2.1 General measures concerning consumer protection and fair competition

Misleading advertising has been subject to EU-wide law on consumer protection since

the adoption in 2005, of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD).

The Directive seeks to address “unfair, misleading and aggressive commercial practices

which are capable of distorting consumers’ economic behaviour. It is further clarified that:

‘to materially distort the economic behaviour of consumers’ means using a commercial

practice to appreciably impair the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision,

thereby causing the consumer to take a transactional decision that he would not have

taken otherwise.

The Directive also notes that misleading advertising may involve any marketing of a

product, which creates confusion with any products, trade marks… or other distinguishing

markets of a competitor.

5

When applying the provisions of the Directive, authorities are advised to assess the likely

effect of an advertisement on the behaviour of an “an average consumer”. For example,

in its Guidelines accompanying the UCPD,

6

the Commission notes that a commercial

practice may be considered unfair not only if it is likely to cause the average consumer to

purpose or note to purchase a product, but also if it is likely to cause the consumer to, for

example… decide not to switch to another service provider or product.

In addition, the 2006 Directive concerning misleading and comparative advertising,

7

focuses on addressing marketing behaviours that could lead to distortion of competition

within the internal market. The preamble to the Directive notes that advertising affects the

economic welfare of consumers and traders. It observes that, as advertising is a very

important means of creating genuine outlets for all goods and services throughout the

Community, the basic provisions governing the form and content of comparative

advertising should be uniform and the conditions of the use of comparative advertising in

the Member States should be harmonized. “If these conditions are met, this will help

demonstrate objectively the merits of the various comparable products. Comparative

advertising can also stimulate competition between suppliers of goods and services to

the consumer's advantage.”

8

5 Article 6(2) UCPD

6 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016SC0163

7 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32006L0114

8 Recital 6 Directive 2006/114/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006

concerning misleading and comparative advertising

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 9

Article 4 of the Directive on misleading and comparative advertising permits comparative

advertising providing it (inter alia) does not discredit or denigrate the trade names, other

distinguishing marks, goods, services etc of a competitor and does not take unfair

advantage of the reputation of a trade mark, trade name or other distinguishing marks of

a competitor… and does not create confusion among traders, between the advertiser and

a competitor or between the advertiser's trade marks, trade names, other distinguishing

marks, goods or services and those of a competitor. Member states are required to

ensure that adequate and effective means exist to combat misleading advertising and

enforce compliance with provisions on comparative advertising in the interests of traders

and competitors.

2.2.2 Measures specific to the electronic communications sector

National Regulatory Authorities have not traditionally engaged in measures to guide or

govern advertising of telecom services. However, there are provisions in the EU

electronic communications Code which require service providers to take steps to ensure

that consumer contracts for Internet Access Services (and telecommunications services

more widely) are complete and accurate, and NRAs are often involved in enforcing these

provisions.

For example article 102 of the Code requires service providers to include a concise and

easily readable contract summary which includes inter alia information about the main

characteristics of each service provided. The Commission has published a contract

summary template for this purpose.

9

In line with the provisions of the 2015 TSM Regulation,

10

which sought to provide greater

transparency on the quality and actual performance of broadband offers (in the context

of supporting open Internet access and “net neutrality”), the template requires service

providers to provide information about “Speed of the internet access service and

remedies in case of problems". Specifically, it notes that:

Where the service includes internet access, a summary of the information required

pursuant to points (d) and (e) of Article 4 of Regulation (EU) 2015/2120 shall be

included. For fixed internet access service the normally available download speed

and for mobile internet access service the maximum download speed shall be

included. Where justifiable, a range of speed can be given. Remedies available to

the consumer in accordance with national law in the event of continuous or

regularly recurring discrepancy between the actual performance of the internet

access service and the performance indicated in the contract shall be described.

9 https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/initiatives/ares-2018-4821885_en

10 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R2120

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 10

The 2014 Broadband Cost Reduction Directive

11

also contains a provision

12

that

member states may (voluntarily) provide a “broadband-ready label” for buildings which

have been equipmped with high-speed-ready in-building physical infrastructure.

In the context of the BB CRD, ‘High-speed-ready in-building physical infrastructure’

means in-building physical infrastructure intended to host elements or enable delivery of

high-speed

13

electronic communications networks.

A general theme in telecom legislation and guidelines has been to promote actions which

serve to foster the deployment of and access to broadband at increasing bandwidths over

time. However, there are only a limited range of mechanisms at EU level which serve to

promote awareness of the different characteristics of products.

At the same time, assessments by advertising authorities which may be called upon to

address claims about misleading advertising under general advertising rules may not

sufficiently reflect more subtle differences between products and services, which may be

central to the bandwidth and quality objectives established in electronic communications

policy at a given time.

11 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014L0061

12 Article 8 BB CRD

13

The 2014 BB CRD sets the definition of high speed electronic communications networks as networks

capable of delivering broadband access services at speeds of only above 30Mbit/s. The objectives of

the BB CRD align with the Digital Agenda for Europe, which was relevant at that time. These objectives

have in practical terms, been superceded by the focus on VHC connectivity, introduced in the Code in

2018..

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 11

3 Current practice

Although there is a common body of EU law addressing misleading advertising, different

policies have been adopted concerning broadband, which may reflect differing degrees

of awareness amongst authorities concerning telecom policy. For this study, we have

prepared case studies of broadband advertising standards practices across 8 current and

former EU member states – namely Italy, France, the UK, Ireland, Germany, Denmark,

Poland and the Netherlands.

The countries were selected on the basis that full fibre technologies coexist alongside

part fibre technologies and thus there was the potential for misleading advertising of fibre.

Moreover, we were aware that steps had been taken to address misleading advertising

and/or standardize advertising in some, but not all of the countries.

3.1 Approaches to advertising standards in the countries studied

The table below summarises applicable guidelines and rulings on “fibre” in broadband

advertising.

Country

Advertising/labelling development

Relevant authority

Italy

2018 Traffic-light system from NRA requiring advertisers to

distinguish between full (FTTH/B) vs part fibre vs copper via

“labels”.

AGCOM/NRA

2018 fines from competition authority on TI, Fastweb,

Vodafone and Wind

Competition and Market

Authority AGCM

France

2016 Decree requires service providers to specify (when

referring to fibre) whether connection into the home has

been realised with fibre i.e. distinguish FTTH vs FTTB. If

download speed is reported, upload speed must also be

reported

Legal Decree adopted

by French Govt

2018 legal decision under French Commercial Code

requiring ISPs to cease using fibre where the service does

not involve termination via fibre, and to offer SFR clients

which were missold a fibre connection the option to

unsubscribe. SFR was also required to pay damages to Iliad

Tribunal

UK

ASA concluded that references to “fibre” by ISPs offering

part fibre solutions were not misleading. Cityfibre application

for judicial review rejected Apr 2019

Advertising Standards

Authority

Ireland

In August 2019, the ASAI introduced non-binding Guidelines

which require references to FTTC etc to specify that the

network is based on “part fibre”, and clearly highlight cases

where the service advertised is limited in availability

Advertising Standards

Authority for Ireland

(ASAI)

Germany

No specific provisions on references to fibre in broadband

advertising.

From 2017 onwards the NRA obliged ISP’s to provide a

‘product fact sheet’ on their website displaying in addition to

the max advertised speed the normally available speed and

the minimum available speed.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 12

Country

Advertising/labelling development

Relevant authority

Denmark

Industry-led labelling scheme developed in 2008 by Dansk

Energi “Dansk Fibernet”, requiring offer of fast and

symmetric speeds, upgradable up to 1Gbits based on FTTH

Dansk Energi (industry

trade association)

Poland

No Guidelines or Decisions concerning misleading

advertising, but Orange Polska has publicly claimed that

cable operators are engaged in misleading advertising in

relation to fibre

Netherlands

No specific Guidelines governing “fibre” advertising.

However, in 2014 the Appeal Board of the Advertising Code

Committee advised the cable operator to cease using the

term “own fibre optic cable network” following complaints

raised by Reggefiber

Board of Appeal of the

Advertising Code

Committee (non-

binding)

Only two of the eight countries covered by the research have adopted binding rules or

legislation governing the use of the term “fibre”. In France, a Decree adopted in 2016

requires service providers making reference to fibre to specify whether the connection

into the home is fibre (i.e. to distinguish FTTH from FTTB), and to specify the upload

speed, whenever the download speed is specified. Meanwhile, in 2018 the Italian

regulator AGCOM adopted a mandatory “traffic light” system, whereby the word “fibra”

and green labelling is reserved for FTTH/B, while yellow refers to part fibre (e.g. FTTC)

and red to copper (ADSL) services.

The labels are shown in the figure below. However, a fibre optic offering (with a green

label) may be advertised as such, even if it is not available nationwide.

Figure 1: AGCOM sticker

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 13

Source: AGCOM (2018).

14

Another important feature of the AGCOM ruling is that the implicit association of several

technological architectures under the same commercial brand in one-to-many

communication is not allowed.

In both Italy and France, adoption of the legal rulings on fibre labelling were triggered by

cases in which operators were fined for advertisements deemed to be misleading.

Specifically, in 2018 the Italian Competition and Market Authority

15

imposed fines on

Telecom Italia (4.8 million €)

16

, Fastweb (4.4 million €)

17

and Vodafone (4.6 million

euros)

18

for misleading advertising of fibre optics and Wind Tre

19

(4.25 million €)

20

for

misleading and omissive advertising of fibre optics.

The AGCM noted that the fibre optic connection advertising campaigns used wording that

suggested the exclusive use of fibre and/or the achievement of maximum performance in

terms of speed and reliability of the connection, without adequately informing consumers

of the actual characteristics and limitations of the service offered. This meant in particular

geographical limits on the coverage of the various network solutions, the differences in

the services available and different performance depending on the infrastructure used for

the fibre connection.

21

As a result of that conduct, according to AGCM, the use of the generic term 'fibre' means

that the consumer is not able to identify the special characteristics of the products.

22

In August 2019, the Antitrust Authority also accepted complaints of the National

Consumer Union, and imposed fines totalling €875,000 on TIM, Fastweb, Wind Tre and

Vodafone for misleading offers on fibre.

23

14 Allegato C alla delibera n. 292/18/CONS

15 L’Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato - AGCM

16 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/3/alias-2458

, Rome, 16 March, 2018

17 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2459, Rome, 23 April, 2018

18 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2456, Rome, 27 April, 2018

19 The fine of 4,25 million for Wind Tre related to both mobile Internet services and Internet connectivity

services using fibre optic technology.

20 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2457

, Rome, 11 April, 2018

21 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/3/alias-2458, Rome, 16 March, 2018;

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2459, Rome, 23 April, 2018;

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2456, Rome, 27 April, 2018;

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2457, Rome, 11 April, 2018

22 https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/3/alias-2458, Rome, 16 March, 2018,

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2459, Rome, 23 April, 2018,

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2456, Rome, 27 April, 2018;

https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2018/4/alias-2457, Rome, 11 April, 2018

23 https://www.consumatori.it/comunicati-stampa/antitrust-vittoria-unc-compagnie-telefoniche-fibra/;

https://www.telecomtv.com/content/fttx/consumer-group-claims-victory-as-italy-takes-hard-line-on-

fibre-advertising-35956/; https://www.agcm.it/dotcmsdoc/bollettini/2019/31-19.pdf

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 14

Meanwhile in France, the Decree referring to fibre was influenced by a legal challenge

mounted by Iliad in 2015 against the use of the word “fibre” by SFR, following SFR’s

acquisition of cable operator Numericable, which resulted in the company using a

combination of full fibre, FTTB (with in-building cable) and cable technology to deliver its

services.

24

Iliad’s legal challenge, was based on alleged infringement of the French

Commercial Code.

25

In its January 2018 conclusions, the tribunal found in favour of Iliad,

and required SFR to:

• Cease using the term fibre in cases where the service does not involve termination

via fibre optics in the premises of the subscriber

• Not to use, for “very high speed” offers, the term “fibre” without specifying where

this technology ends within its network

• Cease all national advertising which presents their network as being based on a

an infrastructure which is technologically homogeneous

• Specify in commercial communications, the precise characteristics of

infrastructure used in the relevant zone

• Communcate to each client which subscribed to an offer mentioning the word

“fibre” with SFR or Numericable (except for FTTH offers), information concerning

the nature of the connection including the distance to the fibre optic cable, the

number of households sharing the cable, and the average speeds in peak and

non-peak hours

• Inform clients which subscribed to a “fibre” offer which was not FTTH, that they

could benefit from the option to cease their connection with immediate effect, as

a result of the inaccurate information provided concerning its characteristics; and

• Publish in each journal in which the misleading advertisements were published a

judicial statement, noting that it had engaged in misleading advertising in

representing in offers carrying the term “fibre” services offered via cable, which

cannot offer the same quality of connectivity as offers using fibre up to the building,

and that this could undermine the investments made by operators deploying fibre.

• Pay damages of €51.87m to Iliad

One other country from those reviewed – Ireland – has issued non-binding Guidelines

around the use of the word “fibre”. In August 2019, the ASAI released Part 1 of a

Guidance note on “marketing communications for mobile phone and broadband

services”. The note states that the ASAI consider that “where the descriptor ‘fibre’ is used

and where the service is not provided on a full fibre network, advertising must contain a

prominent qualification that the network is ‘part fibre’”. The Guidelines also state that “if

a product is described by a narrative, such as ‘high speed’, ‘superfast’ or similar,

24 https://lexpansion.lexpress.fr/high-tech/fibre-optique-free-attaque-en-justice-numericable-

sfr_1732021.html

25 Article L 480-8 Code du Commerce

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 15

advertisers must ensure that the use of language does not mislead, bearing in mind the

existing comparator products available, e.g. superfast must not be used for products

which are significantly slower than the maximum generally available product on the

market.”

On the subject of “availability”, the Guidelines note that “advertisers offering mobile phone

and broadband services must take care in the design and presentation of their marketing

communications so as not to exaggerate the availability of their products, particularly

when new products/technology are launched. Where the provider offers limited

geographical coverage, advertising in national media must include a prominent and

transparent reference to this fact.”

Contrary to the decision reached in Ireland, in 2017 conclusions published by the UK’s

Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), they found that there were no grounds to establish

guidance in relation to use of the term “fibre”. These conclusions were based on their

interpretation of the results of consumer research that they had commissioned from

Define. The ASA highlighted the summary of the research conclusions, which stated that:

• The term ‘fibre’ was not one of the priorities identified by participants when

choosing a broadband package; it was not a key differentiator.

• The word ‘fibre’ was not spontaneously identified within ads – it was not noticed

by participants and did not act as a trigger for taking further action. It was seen as

one of many buzzwords to describe modern, fast broadband.

• Once educated about the meaning of fibre, participants did not believe they would

change their previous purchasing decisions; they did not think that the word ‘fibre’

should be changed in part-fibre ads.

No guidelines on the use of “fibre” in advertising have been considered or adopted in

Poland, Germany, the Netherlands or Denmark.

However, in 2008 the association representing Danish fibre utilities established a

voluntary certification scheme under which operators offering services meeting certain

characteristics (including full fibre with symmetric bandwidths upgradable to 1Gbit/s)

could use a standard label “Dansk Fibernet”.

A number of complaints have been raised on the subject in the Netherlands, and in 2014

the Appeal Board of the Advertising Code Committee (a non-statutory body) advised the

cable operator to cease using the term “own fibre network” in advertisements which it had

issued in response to Regefiber’s deployment of FTTH.

More generally, it can be said that the clearest and strongest actions (and all binding

measures) that have been taken to address misleading advertising, have typically been

taken by bodies other than the advertising authorities – such as the national regulatory

authority for telecoms and competition authority, in the case of Italy, and the competition

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 16

authority and Government, in the case of France. This may reflect the greater awareness

of competition and telecom regulatory authorities of the importance and effects of these

cases. However, most telecom regulatory authorities do not have the powers to act in this

area, and the standards required for a competition law case are relatively high, with the

French and Italian competition authorities being relatively unique in their willingness and

ability to process such cases efficiently.

3.2 Advertising practices, past and present

Approaches to advertising, including where relevant, changes in approaches to

advertising resulting from Guidelines or decisions, are summarised in the following table.

Country

Date of Decision

concerning “fibre”

Advertising

practice before

Current advertising practice

France

2016 Govt Decree

2018 Court judgement

FTTB/cable

advertised as

“fibre”

Technologies are referenced in

advertising

“Fibre” commonly used, but only for

FTTH, otherwise ADSL, cable

Italy

2018 AGCOM

Decision (traffic lights)

and court judgement

Restrictions on

associating different

architectures with

same commercial

brand

FTTC, wireless

advertised as

“fibre”

Technologies are referenced in

advertising

Labelling system is applied. “Fibre”

used only for FTTH/B, but is widely

promoted despite limited availability.

Ireland

2019 ASAI Guidelines

FTTC, wireless,

advertised as

“fibre”

Most operators now focus on headline

speed and/or super/ultrafast although

eir advertises FTTH as “fibre”

Netherlands

2014 Decision of the

Appeal Board

Advertising Code

Committee

Cable advertised

as if fibre

Cable advertising refers to “Gigabit

speed” on “Giganet”

KPN distinguishes standard

broadband from “fibre optic”

UK

2017 ASA concluded

that references to

“fibre” were not

misleading

Cable, FTTC

widely advertised

as fibre

Cable, FTTC widely advertised as

fibre

Distinctions only between superfast,

ultrafast

Poland

None

Cable operator refers to “fibre” for

architectures which include coax at

least in the final segment (incl FTTB)

Pure FTTH operators also refer to

“fibre”

Germany

None

Technologies are referenced in

advertising

Most operators distinguish between

ADSL, cable and fibre optic

Denmark

None

Only fibre utilities refer to “fibre”

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 17

Other operators focus on headline

speeds, Gigaspeed etc

The decisions in Italy and France regarding “fibre” advertising were taken in response to

conduct by major service providers which was deemed to be misleading. In Italy, the term

“fibre” had been used for services based only on partial fibre deployment (FTTC).

Meanwhile, following its merger with the FTTH/copper-based operator SFR, Numericable

had been advertising services as “fibre” without reference to the actual (cable) technology

used (see below). For example, Numericable offered “fibre” up to 800Mbit/s in Paris and

up to 400Mbit/s in Marseille, Lyon, Bordeaux, revealing the differing technological

capabilities of the network, and constraints resulting from use of cable infrastructure.

Figure 2: Numericable web advertisements prior to the Decree……………………..

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Numericable website

Following the introduction of legislation, misleading references to fibre in France and Italy

ceased, but some issues remain – especially in Italy.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 18

Italian operators are making, apparently correct, use of the labelling scheme to distinguish

between fibre and other products. However, it is notable that our review of offers

advertised on websites, fibre offers have been made central to the marketing campaigns,

despite the limited availability of fibre infrastructure.

In France, full fibre operators including Orange and Iliad now typically distinguish between

“fibre” offers and “ADSL” offers. SFR (the operator subject to the court decision) similarly

distinguishes between offers based on “fibre” and “ADSL”, and is promoting its new “box

8”, which relies on these technologies. However, for its cable network, SFR also offers

(but does not actively promote to the same extent), a “4K THD” (Very high speed) box,

which is no longer labelled as “fibre”.

Figure 3: SFR/Numericable web advertising after the Decree

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 19

Source: SFR website January 2020

Approaches towards broadband advertising have also changed in the Netherlands and

Ireland, following the adoption of non-binding Guidelines or arbitrarion decisions.

In the Netherlands, cable operator Ziggo no longer refers to fibre in advertising, but

instead focuses on “Gigabit speeds”. On Ziggo's current website,

26

the company's own

network is not generally referred to as a "fibre optic network". Rather, it is highlighted that

97% of the network is made up of fibre and the last piece is "super fast coaxial cable".

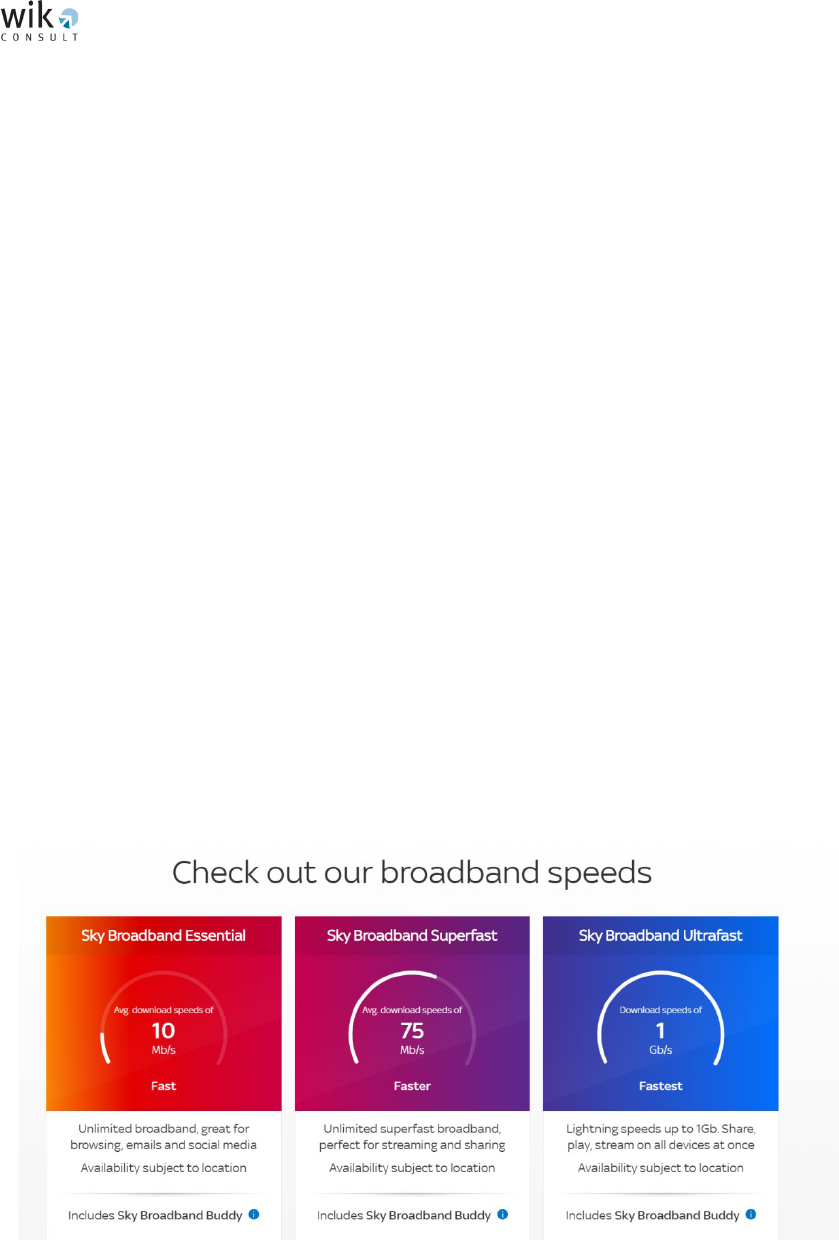

In Ireland, prior to the release of the Guidelines by the ASAI, major operators were using

“fibre” to advertise FTTC and HFC-based services as shown in the screenshots below.

Figure 4: Sky Ireland sample advertisement

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Sky Ireland website Jan 2020

However, following the introduction of the Guidelines, operators have changed or

restricted their references to fibre. For example, Sky has focused on distinguishing

26 https://www.ziggo.nl/internet/glasvezel/,

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 20

speeds, with reference to the labels “essential”, “superfast” and “ultrafast”, with ultrafast

broadband promising speeds only achievable via Sky’s fibre-based offering. Vodafone

seems to have pursued a similar strategy, but with a focus on first obtaining customers’

location to present relevant offers. Virgin Media (based on cable), has also chosen to

focus on the headline download speed (see below).

Figure 5: Virgin Media Ireland advertisements

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Virgin Media website Jan 2020

Eir has on the other hand chosen to explicitly advertise services based on fibre (150Mbit/s

and above) as such, while focusing for part-fibre services only on the headline speeds.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 21

Figure 6: eir advertisements

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: eir website Jan 2020

The change in approach that can be seen in Ireland, contrasts with the continued

indiscriminate references to “fibre” in the UK, where the ASA concluded that such

references were not misleading to consumers.

For example, in contrast to their advertising in Ireland, Virgin Media in the UK, is

advertising “lightning fast broadband” with an image showing fibre optics, and references

to “fibre broadband” in relation to a 200Mbit/s product that is likely in most cases to be

delivered via cable.

Figure 7: Virgin Media UK advertisements

______________________________________________________________________

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 22

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Virgin Media UK website Jan 2020

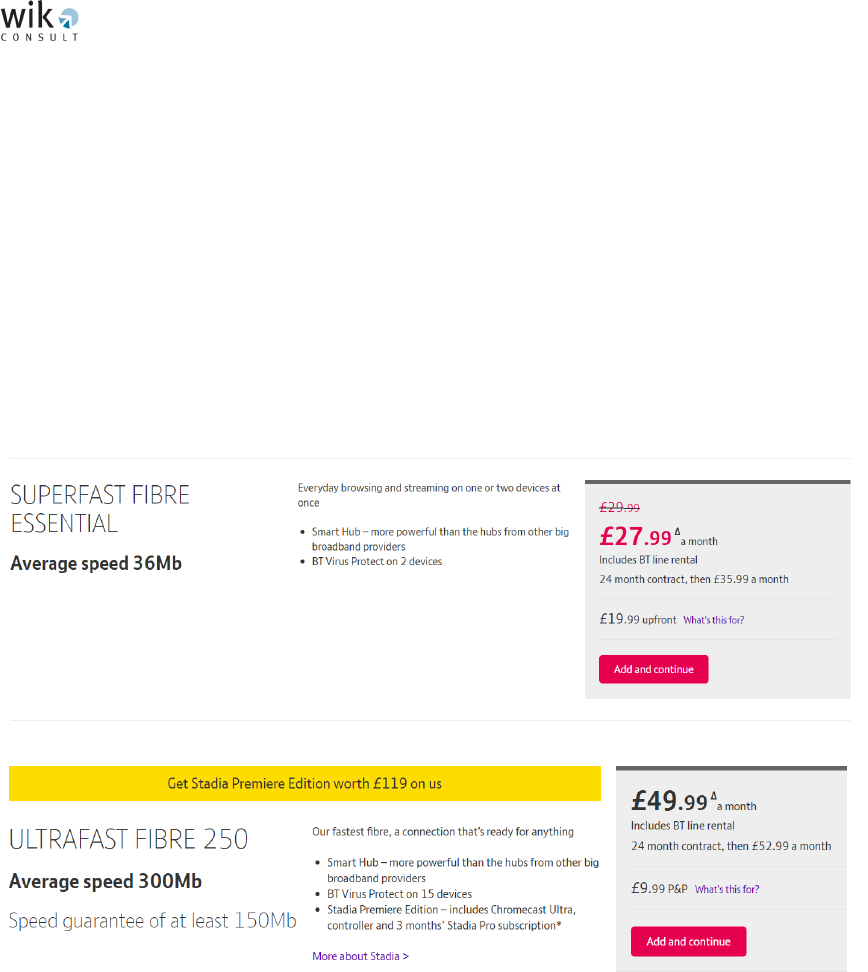

BT, which provides broadband services predominantly via FTTC/VDSL, with a small, but

expanding FTTH footprint, refers to “fibre” across their full portfolio. For example

broadband services with speeds of just 36Mbit/s (likely based on VDSL) are being

advertised as “superfast fibre essential”. True FTTH-based products at speeds of up to

300Mbit/s are meanwhile being advertised as Ultrafast fibre. Thus, with references to

“fibre” predominating – the only distinguishing feature for broadband products is between

“superfast” and “ultrafast”, and it may not in all cases clear to consumers, what these

labels mean.

“Fibre » is also referenced in advertising by the Polish cable operator UPC for services

which appear to rely on the coax network, at least in the terminating segment. The

advertisements specify that the services are based on FTTB technology. This has led to

complaints in the media from the incumbent Orange Polska, that customers cannot

readily distinguish the quality available from UPC from their own FTTH-based network,

which is also marketed as “fibre”.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 23

Figure 8: Extract from Website UPC Polska

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: https://www.upc.pl/internet/kup-internet/internetowi-start-500-24mc/.

27

Notwithstanding the absence of formal guidelines, in Germany, technologies are

distinguished in advertising and fibre is typically been referenced in the context of FTTH/B

deployment. For example, Deutsche Telekom distinguishes on its website between

products offering “Internet and DSL” and “fibre optics”. However, the DT xDSL and fibre-

optic tariffs are both marketed under the MagentaHome brand, which would not have

been permitted under the Italian regime. Meanwhile, Vodafone offers "Kabel-Internet"

(cable Internet), "DSL" and "Glasfaser" (optical fibre), and markets its cable, DSL and

fibre optic tariffs under different brands ("Red Internet & Phone Cable" "Red Internet &

Phone DSL", "Red Internet & Phone Glasfaser"). However, Vodafone does make mention

of “fibre optic Internet” in the context of cable.

Meanwhile in Denmark, only the fibre utilities (with deployments based on FTTH) make

use of the word “fibre” in advertising. Other operators, whose services are often based

on a mix of FTTC, cable and FTTH technologies refer instead to headline speeds with a

tagline of “Gigaspeed” or “maxspeed” for the highest speed bands available.

27 translated from Polish into English via Google Chrome

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 24

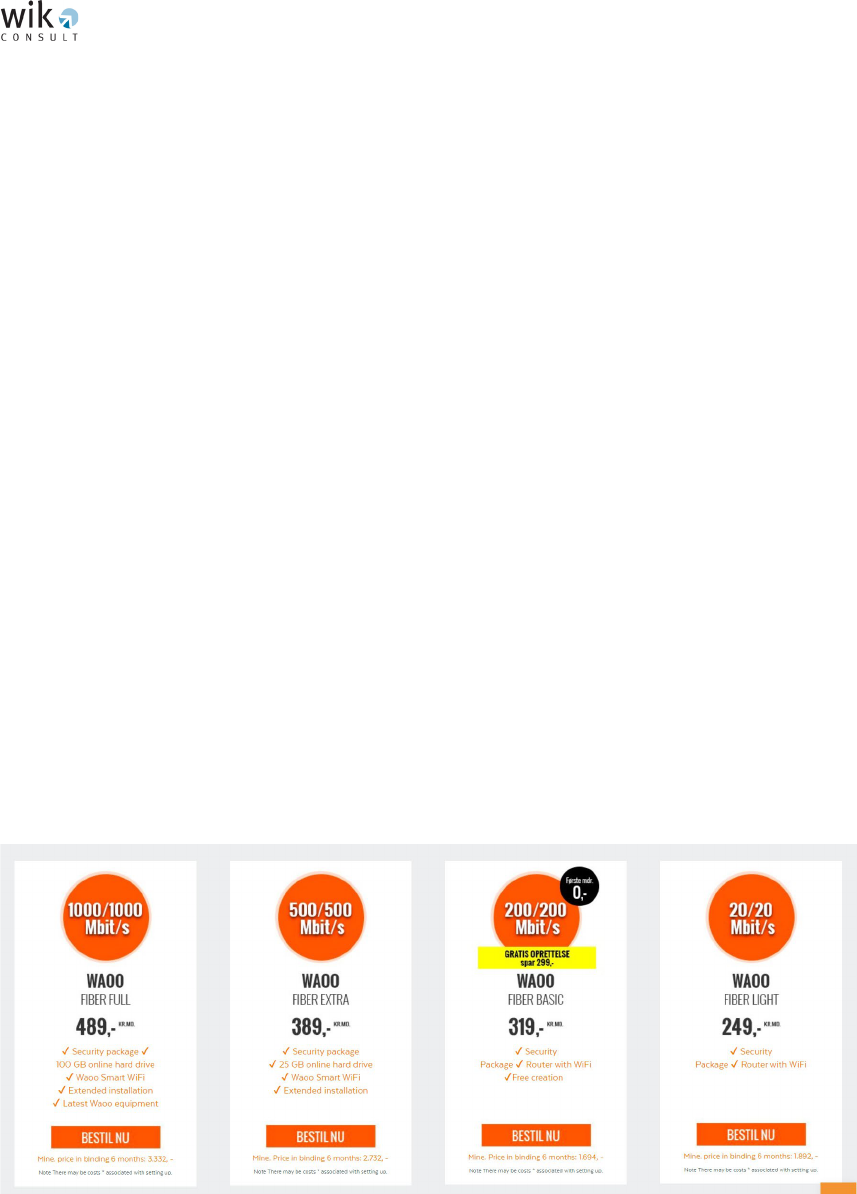

Figure 9: Waoo (fibre utility) advertising

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Waoo website Jan 2020

Overall, the case studies suggest that measures to limit misleading references to “fibre”

in advertising have been effective in changing conduct in France and (partially) Italy, as

well as in Ireland and the Netherlands, while challenges remain with advertising practices

in the UK, and (to a lesser extent) Poland and Germany.

It has become standard practice in most of the countries examined to refer to broadband

with reference to the technology used and to use “fibre” as a marketing tool to distinguish

very high grade broadband services from others. Exceptions are the UK and Ireland,

where the indiscriminate use of the word “fibre” has meant that the main distinguishing

feature has been references to “superfast” and “ultrafast” speeds, which may however

themselves be subject to interpretation.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 25

4 What is the impact of misleading advertising, and which

approaches have proved to be most effective in addressing it?

As discussed in section 2.1, measures against misleading advertising have been justified

at EU and national level on the basis that it undermines the ability of customers to make

an informed choice between products which have different characteristics, and as a

consequence undermines the business case for operators to invest in superior

technology, as those that do face the potential of unfair competition from products which

falsely claim to have the same properties as their own.

The case to promote clear labelling in broadband is further supported by the fact that

different technologies have been found to offer different capabilities in terms of speed

and quality

28

and higher bandwidths have been associated with economic, social and (in

the case of fibre) environmental benefits.

29

To realise these benefits, the European

Commission, BEREC and NRAs have been given a new objective in the Code to foster

availability of and access to very high capacity networks.

30

Future and complementary

wireless networks such as 5G and its successors will also depend to a large extent on

the widespread availability of fibre. That widespread availability of fibre has been

described as a necessary (but not sufficient) condition of 5G deployment and by

implication, of all the services and industrial processes that will depend on these

networks. Furthermore, knowledge about the differences between technologies and the

advantages offered by fibre compared with legacy technologies will be important in

enabling the eventual switch-off of the copper network, which is envisaged through

provisions in the Code covering “migration”, which itself will drive significant

environmental savings.

With this in mind, it is concerning that, especially in cases where broadband advertising

is unclear and no action has been taken to inform customers around the capabilities of

different technologies or to limit misleading references to “fibre”, there is evidence that

consumers are not aware of the importance of attributes other than broadband “download

speed”, are confused by the broadband options presented to them, and may not have an

accurate understanding of the services they actually receive.

For example, in a study conducted by Opinion Leader,

31

CityFibre explored consumers’

understanding and potential effects of the use of terminology around “fibre” in Internet

Access Services (IAS) advertising in the UK. Their study used a qualitative approach

covering focus groups and individual interviews with consumers and small businesses in

28 These are outlined in the WIK, IDATE, Deloitte (2016) study for the EC “Regulatory, in particular access,

regimes for network investment in Europe”. A further updated analysis is contained in the WIK (2019)

for the DEA “Telecommunications Markets in 2020”

29 See WIK, Ecorys, VVA (2016) for the EC “Support for the Impact Assessment accompanying the Review

of the EU Framework for electronic communications” and well as WIK (2018) for Ofcom “The benefits

of ultrafast broadband”, and WIK (2019) for the DEA “Telecommunications Markets in 2020”

30 Article 3 EECC

31 Opinion Leader. 2017. Understanding Broadband Customer Responses to Use of 'Fibre' in Advertising

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 26

order to explore: (1) Customers’ understanding of the word “fibre” across different media,

(2) whether inaccurate use of “fibre” can materially mislead customers, (3) the specific

arguments used to justify not changing rules around the use of the word “fibre” in IAS

commercial communication, and (4) alternative terminology or iconography. The study

found that customers currently have generally low levels of trust towards claims of

broadband providers generally. In particular, their doubts revolved around claims of the

speed and level of service quality (to be) delivered. Many participants felt that they had

been promised better technological and service performance prior to their recent

purchases and provider switches than they had ultimately received. Participants in the

CityFibre study were also confused by the often pseudo-technical language used in

broadband advertising. Even after an explanation of the technological differences

between part- and full-fibre, participants were unable to distinguish broadband offers

based on the advertisements. This indicates a consistent lack of clear language in

commercial communication around IAS offers.

Similar findings were made in a study conducted for the UK Advertising Standard

Authority (ASA)

32

which explored the impact of terminology around “fibre” on consumers’

broadband choices in the UK using qualitative research methods. In total, they conducted

30 in-depth interviews with broadband users covering general aspects of the broadband

customer journey and an additional set of 79 in-depth individual interviews focusing on

broadband advertisements and the impact of the word “fibre”. They found that consumers’

interest and engagement with broadband services purchases is generally low.

Purchasing was perceived as boring and as requiring significant effort. While consumers

cared about value for money and bundle aspects of typical IAS offers, hardly any

interviewee mentioned the delivery technology (e.g. fibre) without prompting. As regards

“fibre”, participants in the ASA study did not see terminology around the word as a

differentiator of IAS offers mainly because they assumed fibre simply to be a kind of

shorthand for modern, high quality broadband. The clear majority thought that all ISPs

were offering it in any event. Even with additional information, participants were not able

to distinguish which ads were for full-fibre and which for part-fibre. Similar findings were

made in research conducted by Kantar Milward Brown in August 2018 for SIRO in the

Irish market. Based on a nationally representative sample of 1,000 adults, the

researchers found that over half of respondents were confused by the different uses of

the term ‘fibre’ (e.g. ‘fibre-powered’, ‘fibre broadband’, ‘100% fibre’ etc.) in marketing

campaigns.

33

Moreover, 68% of responding households had changed broadband

providers in the past two years, with speed being ranked as the top consideration when

selecting a provider. However, more than half of the surveyed consumers in Ireland (54%)

did not know what type of broadband provides the fastest speeds.

32 Define research & insight. 2017. ASA - Broadband Fibre Qualitative Research - Final Report,

Advertising Standards Authority, London

33

https://siro.ie/news-and-insights/siro-welcomes-new-asai-guidelines-relating-to-broadband-advertising/

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 27

Representative online surveys conducted by WIK-Consult in the German market in 2017

and 2019 further underline the confusion experienced by consumers about what is meant

by “fibre”, and whether they are currently benefiting from it. In both years, only around

one in ten consumers who stated that they had a full fibre connection at home actually

did given the cross-check for their ISP and the region they live in, while the fibre status

for a further proportion of respondents was uncertain (see foillowing figure).

Figure 10: Consumers in Germany thinking they are on a full fibre IAS

(2017 and 2019)

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

N(2017) = 274 out of a total 4160; N(2019) = 214 out of a total 2750. This translates into a stated fibre

penetration of 6.4% and 7.7% respectively when the actual penetration according to VATM was 2.4% and

4.3% respectively.

Source: WIK-Consult survey data

This confusion means that consumers may not be aware of the benefits that could be

obtained by switching to a full fibre solution, and therefore may decide not to switch.

However, there is ample evidence that customers using full fibre do experience benefits

from using this modern technology. For example, according to the survey conducted on

behalf of Cityfibre, participants, who already had full fibre connections at their homes,

reported a higher level of satisfaction due to higher upload and download speeds as well

as a generally more reliable service than with (their previous) part fibre connections. This

positive experience of consumers actually using FTTH connections is also reflected in

research conducted by WIK-Consult for the FTTH Council, which compared the

experience of consumers using different technological solutions in Sweden and

Germany.

34

An earlier survey conducted by Diffraction

35

arrives at similar conclusions.

They found that consumers in Sweden who subscribe to FTTH/B are on average more

satisfied with their broadband service and keener to try new types of advanced services.

34 Arnold R, Kroon P, Taş S, Tenbrock S. 2018. The socio-economic impact of FTTH, WIK-Consult, Bad

Honnef

35

Felten, Benoit 2015. FTTH/B makes a real difference – Usage survey (Sweden). Diffraction Analysis.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 28

That study also observed the strongest driver of take-up measured using regression

analysis is time, which suggests strongly that fibre is an experience good. Another finding

was that over time, consumers were willing to pay more for their fibre connectivity, the

more they experienced the product the more they valued it, reinforcing the conclusion

that fibre is an experience good.

This is an especially important observation which points to one of the most serious effects

of misleading advertising. Since fibre demand is driven in large part by experience, a

significant cohort of users who believe they are using fibre but are not, and are therefore

not experiencing fibre connectivity, risks reducing demand for fibre in the short, medium

and long terms with the attendant effects on roll-out and copper switch off.

Despite this, the UK ASA’s ultimately concluded that consumers had not been misled as

a result of references to “fibre” in advertising. They cited in support of this decision that

research suggested that consumers were generally satisfied with their current offer, and

did not see “fibre” as a differentiating factor. However, this perception may have been

perpetuated by the widespread (mis)use of the term “fibre” in the British market, and lack

of experience by those currently on part fibre packages of the advantages of full fibre (as

elaborated above). Indeed, these conclusions are supported by the Cityfibre survey,

which found that the overwhelming feeling among participants was that using “fibre” in

the commercial communication for part fibre broadband was misleading. They also

disagreed with ASA’s reasons to permit this practice as they thought this would reinforce

the status quo of consumers with little technological knowledge not being able to choose

the right connection for their needs. The different mandate that ASA holds compared to

that of Ofcom may have influenced this conclusion, noting in particular that the ASA has

no mandate to promote the deployment of VHCN or to facilitating the switch-off of copper

networks and migration to VHCN.

Consumers participating in the study for Cityfibre noted that they wanted a clear and

easy-to-comprehend way to distinguish between various types of access technology.

Likewise, 73% of consumers involved in the Kantar research for SIRO also stated that

they would like a “quality broadband mark” that guarantees the types of service they

would receive.

36

The potential for education to drive more informed consumer choices is

also highlighted in a study conducted at PRICE Lab,

37

which used quantitative methods

to assess the impact of advertising claims on consumers’ broadband choices, and to test

the impact of information campaigns.

38

Although the research did not specifically

consider “fibre”, the researchers did find that one in five consumers chose a provider

advertising “lightning fast” broadband over another offering the same speed at a cheaper

price, suggesting that some consumers are influenced by terminology that implies

36

https://siro.ie/news-and-insights/siro-welcomes-new-asai-guidelines-relating-to-broadband-advertising/

37 A research programme funded by the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, the

Commission for the Regulation of Utilities and the Commission for Communications Regulation.

38 Timmons S, McElvaney TJ, Lunn P. 2019. An experiment for regulatory policy on broadband speed

advertising - ESRI Working Paper No. 641, The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 29

superior quality, even when it may not be associated with a superior offer. The research

also found that providing information to the customers (i) decreased the proportion of

suboptimal decisions, (ii) increased the likelihood that consumers switched package, and

(iii) improved understanding of speed descriptions.

Information campaigns and tools have thus far focused mainly around “download

speeds”, and studies suggest that the download speed was and is still considered the

“primary measure of economic value that end users receive from broadband

infrastructure providers.”

39

This is reflected in the prominence of discussions around the

use of “up to” speed claims in commercial communication around IAS offers.

40

However,

in light of the development of applications which require low latency including services

based on AR and VR, and the trend towards applications running on the cloud (which

require more symmetric bandwidth), a focus on download speed alone may prove to be

misguided, and may limit the degree to which consumers are able to benefit from new

services going forwards. Thus information or labelling campaigns could usefully focus

around the wider benefits of specific technologies, which extend beyond “download

speed”. This would be consistent with the increased focus on fibre (or substantially fibre-

based) VHC technologies in the context of the Code, as well as supporting wider

environmental objectives.

Effective information about the broadband technology when purchasing or switching

one’s IAS is important since subscribing to an IAS is a long-term decision. Contracts last

typically at least 12 months, and commonly run to 24 months. Few consumers switch

their IAS providers regularly resulting in “loyalty penalty”.

41

Usually, this loyalty penalty is

thought of in monetary terms, but perhaps even more importantly, there is a penalty in

terms of broadband speed and other quality of service criteria and ultimately quality of

experience as broadband technology progresses and fibre becomes available to more

and more households. By not considering / not purchasing the latest technologies,

consumers likely forego a substantial positive impact on their well-being, wealth etc. as

the FTTH Council study by WIK-Consult shows.

42

In principle, addressing misleading advertising and providing clear information to

consumers about the relative performance of different products, should in turn result in a

boost in take-up for more performant technologies. In Italy and France, there are indeed

some signals of a ramp-up in take-up of FTTH in the period following the rulings in

39 Rajabiun R, Middleton CA. 2015. Lemons on the edge of the internet: The importance of transparency

for broadband network quality. Communications & Strategies: 119-36. (p. 121f referring to Bauer S,

Clark DD, Lehr W. 2010. Understanding broadband speed measurements. Presented at TPRC,

Washington, D.C.)

40 As discussed in the case studies, all countries examined have introduced measures to ensure the

accuracy of speed reporting in the context of broadband contracts, and often in advertising. However,

measures focused around the technologies used and other features such as symmetry, which may have

longer term relevance for the capabilities of the network have been more limited

41 Merola R, Greenhalgh L. 2017. Exploring the loyalty penalty in the broadband market, Citizens Advice,

London

42 Arnold R, Kroon P, Taş S, Tenbrock S. 2018. The socio-economic impact of FTTH, WIK-Consult, Bad

Honnef

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 30

comparison with technologies which were previously “mis-sold” (primarily FTTC in Italy,

and FTTB/cable in France). In Italy, for example, take-up of FTTH lines grew by 46%

between 2017-2018 and by 49% between 2018-2019 compared with a growth rate of

34% in the previous year (before the introduction of the decree). Meanwhile in France, a

small decline in FTTB (cable termination) connections can be seen between Q4 2015

and Q1 2016, around the time of the Decree. The January 2018 court order permitting

Numericable/SFR customers to unilaterally renounce their connection, may also have

contributed to the ongoing decline in FTTB (cable termination) connections, which

continues to this day. However, many other factors may have contributed to these effects,

including the pace of deployment, and service level challenges following the

SFR/Numericable merger (the overall take-up of FTTH in Italy also remains low), and

thus, while advertising standards may have contributed to the outcomes seen in the

market, it is not possible to conclude definitively to what extent advertising played a role

relative to other factors.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 31

5 Policy recommendations

Actions have been taken in a number of countries – including France, Italy, Ireland and

the Netherlands - to address “misleading advertising” in relation to fibre. These actions

have been justified on the grounds that misleading advertising prevents consumers from

making an informed choice and affects competition in the market.

From a telecom perspective, the case for action has, if anything, been strengthened by

the inclusion of an objective for the European Commission, BEREC and NRAs to foster

the availability of and access to very high capacity broadband networks, as fostering

uptake requires consumers to be properly informed about which products meet the

desired criteria and what benefits these products confer. However, in practice this change

would not have any impact on the conclusions that may be reached by Advertising

Standards Authorities across Europe, as they have no mandate to promote this policy

objective.

A review of the schemes that have been introduced around Europe, clearly demonstrate

that the strongest and most effective forward-looking interventions in the market have

been driven by the National Regulatory Authority or Digital/Telecom Ministry of the

country in question rather than the ASA. In contrast, while their impact can be significant,

few competition authorities have intervened in this area, and their decisions concern

specific cases.

Our review suggests that the clearest and most user-friendly approach could be the

introduction of a labelling scheme, similar to the traffic lights introduced in Italy, whereby

technologies with differing characteristics would be colour coded. This would enable

customers to clearly compare broadband services in terms of their performance and,

potentially, environmental characteristics. A coding system which distinguishes between

FTTH, FTTB and cable-based services, FTTC/NGA FWA and ADSL would best meet the

need to distinguish the different technologies that have been deployed across the EU.

Such a scheme could be applied in a similar manner to current labelling applied for energy

efficiency.

The approach taken in France where only ISPs delivering fibre into the home or premises

are permitted to use the term ‘fibre’ in advertising materials is another model that has

merit in its simplicity.

Guidelines could be considered at EU level to foster the involvement of NRAs and/or

Ministries across Europe and better align policy approaches to advertising broadband

with the objectives established under the Code. Legislative action to introduce a

mandatory labelling scheme for broadband covering performance and potentially

environment characteristics, could also be considered.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 32

In order to avoid problems seen in Italy concerning advertising of products which are not

widely available, in addition to specifying the design of the label and associated criteria,

guidelines should also be provided which ensure that customers are informed when

certain products are not widely available, and what the alternative options are.

We recommend further analysis based on consumer research to confirm the design and

validate the effectiveness of the chosen scheme that could be promoted through

guidelines and/or legislation.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 33

ANNEX: COUNTRY REPORTS

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 34

6 Denmark

6.1 Summary

Broadband is provided by the incumbent in Denmark by a mix of cable, FTTC and to a

lesser extent FTTH. Meanwhile, FTTH has thus far primarily been deployed by regional

fibre utilities.

The trade association representing Danish fibre utilities developed a certification for fibre

networks in 2008 called Dansk Fibernet. Companies participating in the scheme

committed to offering full fibre (FTTH) connections, with symmetric bandwidths and

guaranteed speeds. The infrastructure was certified as “upgradable to 1Gbit/s”.

Although advertising guidelines covering marketing of “speeds” were adopted in 2013,

there are no guidelines covering the use of the word “fibre”. Service providers marketing

FTTH specifically such as Waoo tend to refer to fibre in their marketing, while operators

using a mix of technologies refer to “Gigaspeed” and “Maxspeed” to refer to cable and

FTTH connections.

6.2 Main players and technologies used

FTTH deployment in Denmark has mainly been carried out by regional fibre utility

companies, representing around 60% household coverage. Norlys, the company created

by the merger between SE and Eniig, offers services over both Coax and FTTH. The

incumbent TDC provides broadband primarily over cable infrastructure, and has deployed

FTTC/VDSL to increase the broadband capabilities of its networks in areas where cable

is not available. TDC also provides broadband via FTTH in part of the Copenhagen area

(10% coverage of households), mainly over a network that it acquired from the energy

utility Dong,

43

although expansion has been announced.

44

Broadband service providers such as Telia and Telenor primarily offer broadband

services using wholesale access provided by TDC. However, the energy utilities are in

the process of opening their networks to competition, and some amongst them have

signed wholesale agreements enabling TDC, Telia and Telenor to offer fibre-based

access.

45

43 https://www.commsupdate.com/articles/2009/11/18/tdc-acquires-fibre-optic-network-for-dkk425m/

44 See https://www.macquarie.com/kr/about/newsroom/2018/approach-to-tdc-as-to-discuss-a-possible-

voluntary-takeover-offer/.

45 In October 2014, TREFOR (now EWII) left the Waoo! cooperation to enter a strategic cooperation with

TDC (YouSee) as a service provider. In the first half of 2019, Telia, Telenor and Altibox have announced

that they reached agreements with Eniig (OpenNet).

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 35

6.3 Advertising standards

Complaints over advertising standards in Denmark are handled by the Danish consumer

ombudsman. During the period when the energy utilities were beginning fibre

deployments (2005-2007), Dansk Energi, representing the fibre utilities, highlighted

concerns with the ombudsman about misleading claims on how speeds on copper

networks were advertised (specifically claims about speeds being “up to” a given

bandwidth). Dansk Energi observed that these claims undermined the messaging

provided by its members that fibre provided a future-proof technology delivering

guaranteed speeds, with the potential for symmetrical bandwidth.

In the absence of a statutory or Government-sponsored labelling scheme, in 2008 Dansk

Energi developed its own certification scheme for fibre networks, called “Dansk Fibernet”.

The certification required participating companies to offer:

• An all-in one cable for Internet, TV, telephony, video on demand and other digital

services

• Fast and symmetric speeds and the capability to receive HDTV

• Guaranteed speeds – requiring fibre companies to make available additional

capacity to avoid reductions in the speed due to data loss or the transmission of

video

• Fibre network to be upgradable to a capacity of 1Gbit/s or more

• Signals and services to be provided on fibre networks all the way into the

customer home (FTTH). In housing associations the internal cabling must be

based on fibre networks or PDS cabling minimum category 5G, supporting

Gigabit speeds

As of Feb 2008, Dansk Energi reported that 14 fibre utility operators were participating in

the scheme.

In 2012, following working groups involving the industry, the Consumer Ombudsman

published Guidelines for the marketing of broadband connections, which came into force

in March 2013. The Guidelines require broadband providers to give speed indications

which reflect the actual obtainable speed that a consumer could expected between 7am-

1am and exclude any required capacity not provided to consumers from the marketed

speed, and reflect shared capacity. The Guidelines also expressly require operators to

indicate how concurrent use of services such as TV might impact speeds, and to ensure

that when using the term “up to” – most customers (80%) targeted by the marketing

should be able to obtain the indicated speed. Moreover, the Guidelines state that if the

product is targeting a limited or small group of people, this must be highlighted in the

marketing.

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 36

However, there is no discussion in the Giudelines about appropriate use of references to

“fibre”.

The Guidelines are non-binding, but indicate how the ombudsman would enforce

marketing legislation.

Advertising is not considered to be within the remit of the regulatory authority. However,

the authority is responsible for the implementation of regulations concerning net

neutrality, which include provisions to ensure that accurate information is provided about

the capabilities of broadband products in the contracts signed by consumers.

6.4 Advertising practice (past and present)

The adoption of the Guidelines in 2013 led to more detailed and accurate descriptions

concerning the bandwidths achievable via ADSL connections, thereby enabling

consumers to identify the difference with “fibre”.

Waoo, a common marketing platform used by a number of the fibre utilities to sell retail

services, markets its services with reference to “fibre”, using the terms “light”, “basic”,

“extra” and “full”.

Figure 11: Waoo (fibre utility) advertising

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: Waoo website Jan 2020

Noryls notes that when customers on the Waoo platform (used by Eniig) are transferred

from Eniig to Norlys in April 2020, their service will remain unchanged. However, it is not

clear what differences might emerge in Norly’s advertising strategy for cable-based

broadband. Stofa (the pre-merger cable brand) focuses on advertising speeds available

Identifying European Best Practice in Fibre Advertising 37

at given addresses and explains the differences between services offered over the cable

and fibre networks.

46

TDC/Yousee, which primarily uses its cable network to offer broadband, coupled with

FTTC/VDSL and FTTH in specific locations advertises broadband primarily based on

bandwidth and markets its 1000/100Mbit/s offer as “Gigaspeed”. It is notable that, unlike

offers from many of the fibre utilities, the bandwidths offered are asymmetric, thereby

enabling the same “Gigaspeed” marketing to be used for both cable and fibre.

Figure 12: TDC/Yousee advertising

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Source: TDC./Yousee website Jan 2020