COVID RELIEF

Fraud Schemes and

Indicators in SBA

Pandemic Programs

Report to Congressional Committees

May 2023

GAO-23-105331

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-23-105331, a report to

congressional committees

May 2023

COVID RELIEF

Fraud Schemes and

Indicators in SBA Pandemic

Program

s

What GAO Found

The Small Business Administration (SBA) moved quickly under challenging

circumstances to develop and launch pandemic relief programs to help small

businesses. These programs, including the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)

and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL), totaled over

$1 trillion and assisted more than 10 million small businesses. However, in some

instances relief funds went to those who sought to defraud the government. As

schemes emerged, SBA adapted its fraud risk management approach and added

controls to help prevent, detect, and respond to fraud.

GAO analyzed 330 PPP and COVID-19 EIDL fraud cases. Federal prosecutors

across the United States filed bank fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, identity

theft, and other charges against 524 individuals associated with these cases. This

analysis is based on fraud cases publicly announced by the Department of Justice

(DOJ) as of December 2021.

Cases Charged by the Department of Justice Involving Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and

COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Fraud, as of December 31, 2021

In those cases, DOJ charged individuals with

• misrepresenting eligibility, falsifying documents, using stolen identities, and

• deliberately exploiting the programs by conspiring with each other, sharing

knowledge on how to circumvent controls, and obtaining kickbacks.

For the 155 of the 330 cases that reached conclusion through guilty pleas or

convictions, GAO calculated about $188 million in direct financial losses. Across

these cases, as of December 2021, 94 individuals had been sentenced to an

average of about 37 months in prison. The number of cases will continue to grow.

As of January 2023, the SBA Office of Inspector General (OIG) had 536 ongoing

investigations, and the statute of limitations has been extended to 10 years to

prosecute individuals who committed PPP and COVID-19 EIDL-related fraud.

View GAO-23-105331. For more information,

contact

Johana Ayers at (202) 512-6722 or

.

Why GAO Did This Study

Congress established four programs to

support small businesses during the

pandemic: PPP, COVID

-19 EIDL,

Restaur

ant Revitalization Fund, and

Shuttered Venue Operators Grant.

Widely reported incidents of fraud

raised questions about SBA’s

management of these programs. For

this and other reasons, GAO added

small business emergency loans to its

High Risk Program in 202

1.

The CARES Act includes a provision

for GAO to monitor COVID

-19

pandemic relief funds. This report

(1)

analyzes fraud cases charged by

DOJ involving PPP and COVID

-19

EIDL to understand fraud schemes and

impacts, (2)

provides the results of

select data an

alyses regarding fraud

indicators in PPP and COVID

-

19 EIDL,

and (3) identifies opportunities for SBA

to enhance its data analytics.

GAO analyzed DOJ press releases

and court documents related to PPP

and COVID

-19 EIDL cases publicly

announced as of December

2021 for

fraud schemes and impacts. GAO

analyzed 2020 and 2021 PPP and

COVID

-

19 EIDL data, comparing these

data to NDNH wage data to identify the

presence of fraud indicators. GAO also

evaluated SBA’s data analytic efforts

against leading practices.

What

GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that SBA

(1)

ensures it has and utilizes

mechanisms to facilitate cross

-

program

data analytics and (2) identifies

external data sources that could aid in

fraud prevention and detection and

develop a plan to obtain access to

th

ose sources. SBA concurred with

both recommendations.

Highlights of GAO-23-105331 (Continued)

United States Government Accountability Office

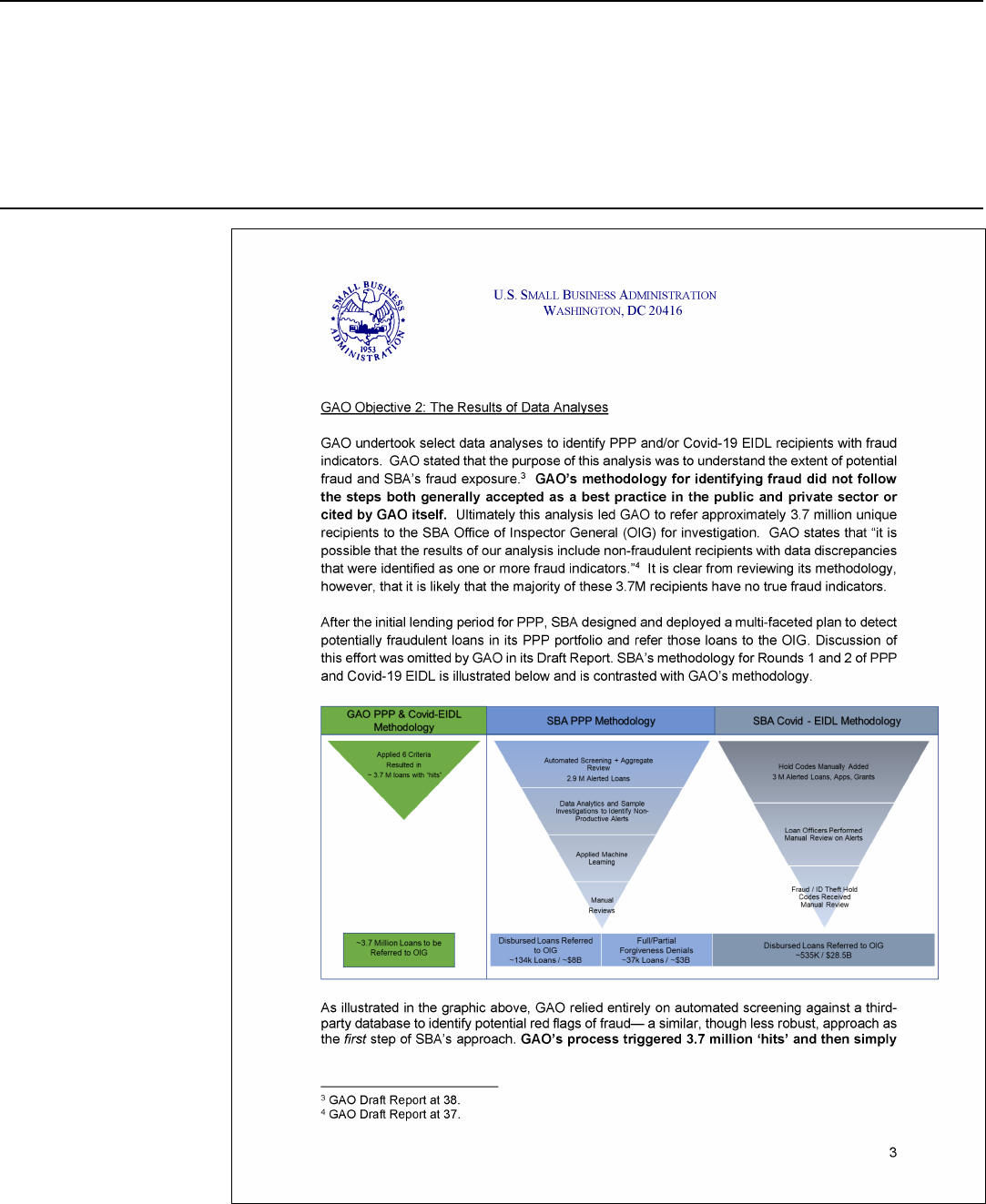

Select GAO analyses of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL data, including comparisons with National Directory of New Hires

(NDNH) wage data, identified over 3.7 million unique recipients with fraud indicators out of a total of 13.4 million (see

figure). Fraud indicators can be used to identify potential fraud and assess fraud risk. They are not proof of fraud.

Additional review, investigation, and adjudication is needed to determine if fraud exists. To that end, GAO referred the

unique recipients with fraud indicators it identified to the SBA OIG for further review and investigation. The unique

recipients identified include potentially non-existent businesses or businesses that may have misrepresented employee

counts to obtain more funds. However, it is possible that the analysis identified non-fraudulent recipients with data

discrepancies consistent with an indicator. While SBA has conducted its own analyses to identify recipients with fraud

indicators, it does not have access to the NDNH database and could not have performed the same analyses as GAO.

Unique Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Recipients with Fraud Indicators

SBA has employed data analytics to enhance fraud prevention and detection. For example, the use of analytics

contributed to SBA determining that some PPP borrowers were ineligible for loan amounts or used them for unauthorized

purposes, resulting in $4.7 billion in loan proceeds not being forgiven. In addition, SBA referred over 669,000 potentially

fraudulent PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loans to the SBA OIG for investigation after using data analytics and conducting

manual reviews. SBA enhanced its analytic capabilities during the pandemic and has recognized that it would benefit from

further development of its data analytics program. SBA has opportunities to continue to improve its ability to prevent and

detect potentially fraudulent transactions. For example, SBA did not fully leverage information to help identify applicants

who tried to defraud multiple pandemic relief programs. While it has access to multiple external data sources, SBA does

not have access to other external data sources that could aid in fraud detection and prevention. Leveraging information

across programs and obtaining access to external data are consistent with leading fraud risk management practices. SBA

has the opportunity to ensure that it fully leverages data across programs and accesses external data to the fullest extent

possible to mitigate the likelihood and impact of fraud. Obtaining such access could necessitate pursuing statutory

authority or entering into data-sharing agreements with other agencies to gain timely access to those sources.

Page i GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Letter 1

Background 5

Analysis of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL Charges Illustrates Fraud

Schemes and Their Actual and Potential Impacts 21

Our Analysis Reveals Millions of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL

Recipients with Fraud Indicators, and Certain Lenders

Originated Higher Rates of Fraudulent PPP Loans 44

Enhanced Data Analytics Can Help SBA Identify Potentially

Fraudulent Recipients 75

Conclusions 79

Recommendations for Executive Action 80

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 80

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 91

Appendix II Overview of SBA’s Fraud Risk Management Efforts

Implementing the Pandemic Relief Programs 108

Appendix III Prior GAO Recommendations to Address

Fraud Risks and SBA Actions 127

Appendix IV Regression Analysis 131

Appendix V Comments from the Small Business Administration 136

Appendix VI GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 145

Related GAO Products 146

Contents

Page ii GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Tables

Table 1: Characteristics of Small Business Administration’s (SBA)

Pandemic Relief Programs 9

Table 2: Financial Losses (in Millions of Dollars) in Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury

Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Based on Analysis of

Department of Justice Fraud Cases, as of December 31,

2021 35

Table 3: Non-Financial Impacts of Fraud in Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster

Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) 36

Table 4: Top Five Lenders by Number of Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) Loans Associated with a Department of

Justice (DOJ) Fraud Case, as of December 31, 2021 69

Table 5: Created Variables Used in the Regression Analysis of the

Small Business Administration (SBA) Paycheck Protection

Program Loans, Years 2020-2021 132

Table 6: Variables Included in GAO Regression Models Using the

Small Business Administration (SBA) Paycheck Protection

Program Loans, Years 2020-2021 133

Table 7: Associations of Logistic Regression Model Variables

Based on the Small Business Administration’s (SBA)

Paycheck Protection Program Loans, Years 2020-2021 135

Figures

Figure 1: Illustrative Life Cycle of Fraudulent Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster

Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Applications Involving Criminal

Cases 14

Figure 2: The Four Components of the Fraud Risk Management

Framework and Selected Leading Practices 16

Figure 3: Cases Charged by the Department of Justice Involving

Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19

Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Fraud,

as of December 31, 2021 23

Figure 4: Ongoing and Closed Cases Involving Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic

Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Fraud, as of

December 31, 2021 24

Page iii GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 5: Individuals and Businesses Associated with Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic

Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Fraud Cases, as

of December 31, 2021 25

Figure 6: Types of Businesses Identified in Paycheck Protection

Program and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan

Fraud Cases, as of December 31, 2021 26

Figure 7: Clusters of Related Cases Charged by the Department

of Justice Associated with Paycheck Protection Program

and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan Fraud, as

of December 31, 2021 30

Figure 8: Number of Paycheck Protection Program and COVID-19

Economic Injury Disaster Loan Cases Involving

Department of Justice Charges of Asset

Misappropriation, by Type of Ineligible Expense, as of

December 31, 2021 38

Figure 9: Foreign Jurisdictions to Which Fraudsters Redirected

Funds from Paycheck Protection Program and COVID-19

Economic Injury Disaster Loan, as of February 2023 39

Figure 10: Sentencing Ranges for Individuals Sentenced to

Prison, Probation, and Supervised Release for Crimes

Involving Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and

COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19

EIDL), as of December 31, 2021 43

Figure 11: Unique Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and

COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19

EIDL) Recipients with Fraud Indicators 48

Figure 12: Example of Information Mismatch between Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic

Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Data 68

Figure 13: Number of Suspicious Activity Reports Filed on

Paycheck Protection Program Loans, by Month 74

Figure 14: National Directory of New Hires (NDNH) and Small

Business Administration (SBA) Pandemic Relief Data

Obtained for GAO Analysis 97

Figure 15: Examples of Changes to Traditional Small Business

Administration (SBA) Programs Made by the CARES Act 109

Figure 16: The Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Key Fraud

Risk Management Activities Occurred after Most Program

Funds Were Distributed 124

Page iv GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Abbreviations

Board Fraud Risk Management Board

BSA/AML Bank Secrecy Act and related anti-money

laundering requirements

Council Fraud Risk Management Council

COVID-19 EIDL COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan

DOJ Department of Justice

EIN employer identification number

FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

Fraud Risk A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Framework Programs

IP internet protocol

IPSFF International Public Sector Fraud Forum

IRS Internal Revenue Service

NDNH National Directory of New Hires

OIG Office of Inspector General

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PPP Paycheck Protection Program

PRAC Pandemic Response Accountability Committee

RRF Restaurant Revitalization Fund

SAR suspicious activity report

SBA Small Business Administration

SSN Social Security number

SVOG Shuttered Venue Operators Grant

tax ID taxpayer identification number

Treasury Department of the Treasury

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

May 18, 2023

Congressional Committees

The COVID-19 pandemic created economic hardship for small

businesses across the U.S. economy. Businesses in the restaurant, live

performing arts, and entertainment industries were particularly hard hit.

To assist small businesses, Congress created programs through the

Small Business Administration (SBA) between March 2020 and March

2021 for pandemic relief. Specifically, the CARES Act and other laws

provided funding for the newly created Paycheck Protection Program

(PPP) and the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19

EIDL) program, which were available to most small businesses; and the

Restaurant Revitalization Fund (RRF) and the Shuttered Venue

Operators Grant (SVOG), which targeted hard-hit industries.

1

The more

than $1 trillion in relief funds provided through these four programs

assisted more than 10 million small businesses affected by the pandemic.

However, in some instances these relief funds went to those who sought

to defraud the government.

We and others have raised questions about SBA’s management of fraud

risks in these programs.

2

Since June 2020, we have reported multiple

times on fraud schemes, risks, and indicators in SBA’s pandemic relief

programs. Additionally, in March 2021, we added emergency loans for

small businesses to GAO’s High Risk Program, in part because of the

1

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4; Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. M and N, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020);

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, Pub. L. No. 116-139,

134 Stat. 620 (2020); CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020).

2

Fraud is the act of obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation.

Whether an act is fraudulent is determined through the judicial or other adjudicative

system. When fraud risks can be identified and managed, fraud may be less likely to

occur.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

potential for fraud, significant risk to program integrity, and need for

improved program management and better oversight.

3

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor and oversee the

federal government’s efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from

the COVID-19 pandemic.

4

This report (1) analyzes fraud cases charged

by the Department of Justice (DOJ) involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL to

understand fraud schemes and impacts; (2) provides the results of select

data analyses to identify PPP and COVID-19 EIDL recipients with fraud

indicators, as well as fraud-related lender activity in PPP; and

(3) identifies opportunities for SBA to enhance its data analytics to

prevent and detect potential fraud.

5

For the first objective, we conducted a thematic analysis of criminal and

civil fraud cases involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL charged by DOJ and

publicly announced as of December 31, 2021.

6

To identify cases, we

received DOJ press releases through a subscription to Westlaw (a legal

3

The High Risk Program highlights federal programs and operations that we have

determined are in need of transformation, and also names federal programs and

operations that are vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement. GAO, High-

Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-

Risk Areas, GAO-21-119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021) and High-Risk Series:

Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address

All Areas, GAO-23-106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

4

Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 19010(b), 134 Stat. 281, 580 (2020). All of GAO’s reports related

to the COVID-19 pandemic are available on GAO’s website at

https://www.gao.gov/coronavirus.

5

Fraud indicators are characteristics and flags that serve as warning signs suggesting a

potential for fraudulent activity. Indicators can be used to identify potential fraud and

assess fraud risk but are not proof of fraud, which is determined through the judicial or

other adjudicative system.

6

Fraud cases are those PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases that involve fraud-related

charges. Fraud-related charges include criminal fraud charges associated with PPP or

COVID-19 EIDL fraud schemes, such as bank fraud or wire fraud, as well as other

charges for crimes used to execute fraud schemes, such as money laundering or

conspiracy charges. Alternatively, DOJ can pursue civil remedies for suspected fraud

under the False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. § 3729-3733 and the Financial Institutions Reform,

Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989, 12 U.S.C. § 1833a.

We selected December 31, 2021, as the ending point of our research because after

December 31, 2021, SBA stopped accepting COVID-19 EIDL applications (per

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021). PPP closed in May 2021. We acknowledge that

DOJ has continued to bring charges involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL since December

31, 2021, and that later cases may involve more complex fraud schemes that may take

longer to investigate and prosecute.

Page 3 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

news service), conducted periodic checks of the Westlaw database, and

used other available sources, such as the DOJ Fraud Section website.

For identified cases, we obtained relevant court documents by searching

Public Access to Court Electronic Records.

7

Using case information identified in court documents on charged

individuals, fraud mechanisms, and loan amounts, among other things,

we conducted a thematic analysis using the GAO Conceptual Fraud

Model.

8

The model is organized as an ontology, which is an explicit

description of categories of federal fraud, their characteristics, and the

relationships among them. We structured and organized this thematic

analysis using WebProtégé, an ontology modeling tool. We then analyzed

the aggregate data to describe the characteristics and areas of impact of

PPP and COVID-19 EIDL fraud cases. Based on data and information

from these cases, we determined actual and potential financial impacts as

well as non-financial impacts.

For the purposes of our analysis, we considered DOJ cases as closed

when they reached conclusion through settlement, dismissal of charges,

a guilty plea, or a verdict reached at trial.

9

We considered cases as

ongoing when they had not reached a conclusion as of December 31,

2021. The cases are not generalizable to all fraud cases or all potential

fraud involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL. From the identified cases, we

selected closed cases to provide illustrative examples of how fraud

occurred.

For the second objective, we analyzed PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loan-

and advance-level data to identify recipients with fraud indicators. This

included matching that data to quarterly wage data in the National

Directory of New Hires (NDNH) for quarter 4 of 2019 and quarters 1

7

Public Access to Court Electronic Records is a service of the federal judiciary that

enables the public to search online for case information from U.S. district, bankruptcy, and

appellate courts. Federal court records available through this system include case

information (such as names of parties, proceedings, and documents filed) as well as

information on case status.

8

GAO, GAO Fraud Ontology Version 1.0, published January 10, 2022.

https://gaoinnovations.gov/antifraud_resource/howfraudworks

9

In criminal cases, after a finding of guilt, either through guilty plea or verdict, there is a

period of time before the defendant returns to court to be sentenced. Some of the cases

categorized as closed for our analysis had not yet completed the sentencing stage.

Page 4 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

through 3 of 2020.

10

By matching PPP and COVID-19 EIDL data to

NDNH wage data, we identified unique recipients with fraud indicators

associated with potential misrepresentations of business operating status,

employee counts, or payroll costs. We also reviewed the loan-level data

to determine whether applicants received multiple loans or advances, or if

loans were disbursed to multiple recipients using the same information.

Finally, we matched PPP data to COVID-19 EIDL data to identify unique

recipients who obtained funds from both programs, which was permitted,

but who (1) were associated with fraud indicators in both programs or

(2) provided different information to the two programs, which is a fraud

indicator. On the basis of our reliability assessment results, we

determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of

matching and identifying discrepancies associated with fraud indicators.

The intent of our analyses was to understand the extent fraud indicators

existed, SBA’s exposure to fraud risk, and how some recipients may have

taken advantage of those risks. The results of our analyses, including the

identification of discrepancies associated with fraud indicators, should not

be interpreted as proof of fraud.

Additionally, we analyzed PPP lender origination of loans associated with

DOJ cases (identified in objective 1) as well as PPP fraud indicators

(identified in objective 2). Through this analysis, we identified the

characteristics of lenders with loans associated with DOJ cases or loans

that we flagged with fraud indicators. To determine the relevant

population of PPP loans, we matched businesses identified in DOJ cases

that received PPP loans with PPP loan-level data. Further, to provide

insight into associations among variables of lender and borrower

characteristics, we conducted logistic regressions to assess the statistical

significance of associations between fraud indicators, and lender and loan

characteristics with potentially fraudulent loans. A logistic regression

describes the relationship between a binary outcome variable—in this

case incidents of fraud and alleged fraud charged by DOJ—and select

factors of interest, such as loan- and lender-level characteristics and

select fraud indicators, while controlling for other factors.

10

NDNH is a national repository of new hire, quarterly wage, and unemployment insurance

information reported by employers, states, and federal agencies. The NDNH is maintained

and used by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for the federal child

support enforcement program, which assists states in locating parents and enforcing child

support orders. SBA does not have access to NDNH wage data. However, similar

information, such as number of employees and wages paid, can be found on the

employer’s federal tax return and other employer filings.

Page 5 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

For the third objective, we evaluated SBA’s data analytic efforts for

opportunities to enhance fraud prevention and detection by reviewing

previous GAO reports, the results of our fraud indicator analysis, and SBA

planning documents. We assessed SBA’s efforts against the leading

practices identified in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework.

11

For more

information about our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2021 to May 2023 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant effect on the nation and its

economy. Stay-at-home orders, social distancing requirements, and

reduced consumer demand early in the pandemic caused both temporary

and permanent business closures, particularly among small businesses.

To help support small businesses, in March 2020, Congress passed the

CARES Act that, among other things, provided funds for two new SBA

pandemic relief programs. Specifically, it created PPP, which was

authorized under SBA’s existing 7(a) small business lending program.

12

It

also established a COVID-19 EIDL program partially based on an existing

SBA-administered program providing EIDL disaster loans.

13

Both PPP

11

GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO-15-593SP

(Washington, D.C.: July 2015).

12

The 7(a) loan guarantee program provides small businesses access to capital that they

would not be able to access in the competitive market.

13

EIDL, which is part of SBA’s Disaster Loan Program, provides low-interest loans to help

borrowers—small businesses and nonprofit organizations located in a disaster area—

meet obligations or pay ordinary and necessary operating expenses. In this report, we

refer to the Economic Injury Disaster Loan provisions of SBA’s Disaster Loan Program as

“traditional” EIDL and to the EIDL program designed to help small businesses recover

from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic as COVID-19 EIDL. For more

information on SBA’s Disaster Loan Program, see GAO, Small Business Administration:

Disaster Loan Processing Was Timelier, but Planning Improvements and Pilot Program

Evaluation Needed, GAO-20-168 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 7, 2020).

Background

Four SBA Pandemic Relief

Programs

Page 6 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

and COVID-19 EIDL contained programmatic elements that were new

compared to the pre-pandemic programs.

PPP guaranteed over $800 billion to small businesses and nonprofits,

referred to collectively as “small businesses,” to help support payroll

costs, rent, utilities and other eligible operating costs during the

pandemic. Applicants could apply for

• first draw loans in PPP Round 1 between April and August of 2020,

and

• first or second draw loans in PPP Round 2 between January and May

2021.

14

PPP low-interest loans were fully SBA-guaranteed and made to recipients

through a network of participating lenders under program rules set by

Treasury and SBA’s Office of Capital Access. Under certain

circumstances, recipients are eligible for full loan forgiveness. For

example, to be eligible for full forgiveness, at least 60 percent of the loan

had to be used for payroll costs, with the remaining amount used for

eligible non-payroll costs, such as covered mortgage interest, rent, and

utility payments.

15

Participating PPP lenders included depository institutions (for example,

banks and credit unions) and non-depository lending institutions (for

example, SBA-certified development companies and state-regulated

financial companies). Existing 7(a) lenders were automatically allowed to

participate in PPP.

16

According to SBA and the Department of the

Treasury (Treasury) officials, they jointly approved certain new non-

14

A borrower’s first PPP loan, which could be received in either 2020 or 2021 is referred to

as a “first draw loan.” Borrowers that received first draw loans could apply for a second

draw PPP loan in 2021, based on different eligibility requirements.

15

SBA originally required borrowers to spend at least 75 percent of forgivable expenses on

payroll costs, but this requirement was modified by later legislation. Paycheck Protection

Program Flexibility Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-142, § 3(b)(2)(B), 134 Stat. 641, 642

(2020).

16

In an interim final rule published April 2, 2020, SBA announced that any federally insured

depository institution, credit union, or farm credit institution in good standing with its

regulator would automatically qualify to participate in PPP upon submission of SBA’s PPP

Lender Agreement. 85 Fed. Reg. 20,811 at 20,815 (Apr. 15, 2020).

Page 7 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

federally regulated lenders

17

that had to attest they met Bank Secrecy Act

and related anti-money laundering requirements (BSA/AML).

18

SBA’s

requirements for lenders were limited to actions such as confirming

receipt of borrower certifications and supporting payroll documentation.

19

With regard to lender supervision, federally insured depository institutions

are generally supervised through a dual federal-state financial regulatory

system. Specifically, federal banking agencies examine their supervised

banks’ BSA/AML compliance programs as part of safety and soundness

examinations.

20

State regulators also supervise nonbank lenders, such as

financial technology companies and money transmitters, based on state

regulatory requirements.

COVID-19 EIDL provided over $355 billion to businesses from March

2020 to December 2021 to assist their recovery from the economic

effects of the pandemic. SBA managed the COVID-19 EIDL program

directly, initially led by its Office of Disaster Assistance and later by the

Office of Capital Access.

21

The program included two types of funding:

loans and grants, otherwise known as advances. Advances—new

programmatic elements in the COVID-19 EIDL—include EIDL advances

(in 2020) and targeted advances and supplemental targeted advances (in

17

SBA and Treasury were jointly responsible for approving lenders new to SBA to issue

PPP loans. According to SBA officials, SBA approved new federally regulated lenders,

while new non-federally regulated and insured lenders required joint SBA and Treasury

approval.

18

The Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, generally referred to as the Bank

Secrecy Act (BSA), as revised, imposes a number of reporting and recordkeeping

obligations on covered financial institutions in an effort to prevent money laundering and

the financing of terrorism, including, among other things, verifying the identity of

customers, conducting ongoing customer due diligence, and filing suspicious activity

reports with Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

19

Because of limited PPP loan underwriting, lenders and SBA had less information from

applicants to detect errors or fraud. The requirement in SBA’s first interim final rule that

lenders follow applicable BSA requirements may have required lenders to collect

additional identifying information from borrowers before they approved a PPP loan.

20

Federal banking agencies include the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration,

and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. FinCEN has delegated its authority to

examine financial institutions for compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act to the federal

banking agencies. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.810(b).

21

In July 2021, SBA transitioned administration of COVID-19 EIDL from the Office of

Disaster Assistance to the Office of Capital Access. This program did not rely on a

network of lenders to distribute pandemic relief funds.

Page 8 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

2021) for applicants located in low-income communities and meeting

other eligibility requirements. Recipients could use these low-interest

loans and advances as working capital to cover operating expenses to

alleviate economic injury caused by the pandemic.

In December 2020 and March 2021, Congress passed the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021 and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021,

respectively, which appropriated additional funds to PPP and COVID-19

EIDL and made changes to PPP, including allowing a second loan under

certain conditions. Congress also enacted two new programs—RRF and

SVOG.

RRF provided about $29 billion in award funds (which did not need to be

repaid) to recipients—businesses in the food service industry—to use for

eligible expenses such as payroll, business debt, maintenance, or

construction of outdoor seating. SBA’s Office of Capital Access managed

the program directly. RRF accepted applications between May and July

2021.

SVOG provided about $15 billion in grant funds to recipients, which

included live performing arts and entertainment businesses affected by

the pandemic. Recipients could use the funds for eligible expenses that

enable business operations such as payroll, rent or mortgage, and utility

payments. SBA’s Office of Disaster Assistance managed the program

directly. SVOG accepted applications between April and August 2021.

The CARES Act and subsequent legislation allowed for cross-program

participation, in some circumstances. For example, PPP recipients could

also receive COVID-19 EIDL, RRF, and SVOG funds, with some

limitations. In the case of RRF and SVOG, recipients could obtain

COVID-19 EIDL and PPP funds, with certain limitations, but recipients

could not obtain both RRF and SVOG funds.

See table 1 for additional characteristics of the four SBA pandemic relief

programs, including eligibility requirements.

Page 9 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Table 1: Characteristics of Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Pandemic Relief Programs

Characteristic

Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP)

Economic Injury

Disaster Loan

(COVID-19 EIDL)

Restaurant

Revitalization

Fund (RRF)

Shuttered Venue

Operators Grant

(SVOG)

Initial authorizing

legislation

CARES Act; Paycheck

Protection Program

Flexibility Act of 2020

Coronavirus

Preparedness and

Response Supplemental

Appropriations Act of

2020; CARES Act

American Rescue

Plan Act of 2021

Consolidated

Appropriations

Act, 2021

Purpose

To assist small

businesses and

nonprofits economically

affected by COVID-19

To assist small

businesses and

nonprofits economically

affected by COVID-19

To assist small

businesses in the food

service industry affected

by COVID-19

To assist small

businesses in the live

performing arts and

entertainment industry

affected by COVID-19

Transaction type

Forgivable loan

Loan, advances (grants)

Award

Grant

Appropriated funding

a

$813.7 billion

$105 billion

$28.6 billion

$16.3 billion

Funding distributed to

recipients

b

$799 billion

$378 billion in loans

$7 billion in advances

c

$28.6 billion

$14.6 billion

Number of loans,

advances, awards

issued

11.4 million

3.9 million loans

6.8 million advances

100,572

13,011

Page 10 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Characteristic

Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP)

Economic Injury

Disaster Loan

(COVID-19 EIDL)

Restaurant

Revitalization

Fund (RRF)

Shuttered Venue

Operators Grant

(SVOG)

Eligible businesses

•

Generally, not more

than 500 employees

or meet SBA size

standards (either the

industry size

standard or the

alternative size

standard)

• Sole proprietors,

independent

contractors, and self-

employed persons

• Certain nonprofit

organizations, certain

veterans

organizations, or

tribal businesses

• Businesses in the

accommodations and

food services sector

with more than one

physical location may

be eligible if fewer

than 500 people are

employed per

physical location

• Business was in

operation as of

February 15, 2020

• For second draw

loans, businesses

must have no more

than 300 employees

unless “per location”

size standard

applies. SBA

industry-based or

alternative size

standards do not

apply

Loans:

• Not more than 500

employees or meet

SBA size standards

• Small businesses

including small

agricultural

cooperatives,

Employee Stock

Ownership Plans,

tribal concerns, sole

proprietorships,

independent

contractors,

agricultural

enterprises, and

most private

nonprofit

organizations

d

• Business was

established on or

before January 31,

2020

Advances:

• Not more than 500

employees for

advances in 2020

• Not more than 300

employees and low-

income community

and losses to income

greater than 30

percent for targeted

advances

• Not more than 10

employees and low-

income community

and economic losses

greater than 50

percent for

supplemental

targeted advances

• Most agricultural

enterprises were not

eligible for targeted

advances or

supplemental

targeted advances

•

Businesses such as

restaurants, food

stands, food trucks,

caterers, bars, and

similar places of

business that serve

food or drink

• Businesses must

have no more than

20 locations

• Businesses’

operating status

could be open,

temporarily closed,

or opening soon, with

expenses incurred as

of March 11, 2021

•

Venues and

promoters, live

performing arts,

movie theaters,

museums, talent

representatives, and

theatrical producers

• Business was in

operation as of

February 29, 2020

Page 11 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Characteristic

Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP)

Economic Injury

Disaster Loan

(COVID-19 EIDL)

Restaurant

Revitalization

Fund (RRF)

Shuttered Venue

Operators Grant

(SVOG)

Eligible expenses

For loan forgiveness: 60

percent on payroll with

the rest spent on

business rent, mortgage

interest payments, or

utilities, among other

eligible expenses

Payroll, business rent,

certain mortgage

payments and fixed debt

payments

Payroll (including paid

sick leave), rent or

mortgage payments,

utilities, debt service,

construction of outdoor

seating, maintenance,

supplies, food and

beverage (including raw

materials), covered

supplier costs, and

operating expenses

Those that enabled

ongoing business

operations (e.g., payroll

costs, rent, mortgage

payments)

Repayment period

Loans issued prior to

June 5, 2020: 2 years,

unless mutually

extended. Loans issued

on or after June 5, 2020:

5 years.

Loan can be forgiven

when at least 60 percent

used for payroll costs

Up to 30 years; 30-month

deferred repayment.

Advances do not need to

be repaid

Not applicable (NA)

NA

Interest rate for loans

1 percent

3.75 percent for

businesses; 2.75 percent

for nonprofits

NA

NA

Allowed participation

across programs

(Limitations for cross-

program participation)

COVID-19 EIDL, RRF,

SVOG (the amount of a

SVOG grant to be

reduced by the total

amount of a PPP loan

received on or after

December 27, 2020;

entities are ineligible for a

PPP loan after they

receive a SVOG grant)

PPP, RRF, SVOG

PPP, COVID-19 EIDL

(RRF awards adjusted

based on PPP value;

recipients cannot obtain

both RRF and SVOG

funds)

PPP, COVID-19 EIDL

(SVOG awards adjusted

if PPP received on or

after December 27, 2020;

recipients cannot obtain

both RRF and SVOG

funds)

Source: GAO analysis of SBA information. | GAO-23-105331

a

Data as reported by GAO in September 2021 (PPP), July 2021 (COVID-19 EIDL), July

2022 (RRF), and October 2022 (SVOG). SBA provided the following net appropriations

amounts as of September 2022, inclusive of rescissions and transfers: PPP – $820 billion;

COVID-19 EIDL – $75.2 billion; RRF – $28.6 billion; SVOG – $15.1 billion. These amounts

include net funding considerations from laws from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year

2022.

b

Data as reported by SBA in the Agency Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2022.

c

Distributed amount for COVID-19 EIDL is higher than appropriated amount due to

COVID-19 EIDL loan credit subsidy. Loan credit subsidy covers the government’s cost of

extending or guaranteeing credit and is used to protect the government against the risk of

estimated shortfalls in loan repayments. The loan credit subsidy amount is about one-

seventh of the cost of each disaster loan in 2020.

d

Agricultural enterprises did not become eligible until April 24, 2020, based on the

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act.

Page 12 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Fraud is challenging to detect because of its deceptive nature. Generally,

once potential fraud is detected and investigated, alleged fraud cases

may be charged. If a court determines that fraud took place through a

violation of relevant law, then fraudulent spending may be recovered.

The life cycle of fraud in SBA pandemic relief programs, including those

involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL, started with applicants who

circumvented existing controls. Some of the potentially fraudulent

applications were declined by lenders or by SBA through the use of

upfront controls. Other applications were approved, but potential fraud

was later detected through SBA fraud controls or by others such as law

enforcement, whistleblowers, or financial institutions. Some fraudulent

applications will never be detected.

Law enforcement agencies, such as the SBA OIG and U.S. Secret

Service, investigated instances of suspected fraud and violations of

relevant statutes (investigation stage).

22

DOJ has pursued and continues

to pursue a portion of the cases investigated by law enforcement. DOJ

has done this by filing fraud-related criminal charges against individuals

or businesses that submitted the applications, or, less commonly, by

bringing a civil case against an individual or business (prosecution

stage).

23

A criminal case is resolved by a guilty plea, a guilty verdict after trial, an

acquittal after trial, or dismissal of the charges (resolution stage). In the

context of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases, DOJ officials stated that the

vast majority of cases are resolved through plea agreements, with few

cases dismissed or resulting in acquittals. Only criminal cases resulting in

a guilty plea or guilty verdict after trial reach the sentencing phase where

22

In April 2023, the SBA Inspector General testified that his office had assisted the U.S.

Secret Service in the seizure of more than $1 billion stolen by fraudsters from the COVID-

19 EIDL program. Office of Inspector General Reports to Congress on Investigations of

SBA Programs, Before the House Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and

Regulations of the Committee on Small Business, 118

th

Cong., April 19, 2023.

23

Criminal cases involve federal prosecutors filing charges against an accused for violation

of one or more criminal statute, and punishment may result in imprisonment. Civil cases

involve the government alleging violation of civil statute and may result in seeking financial

compensation but no imprisonment.

Fraud in SBA Pandemic

Relief Programs

Page 13 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

the court determines penalties, and funds from fraudulently obtained

loans may be subject to restitution and forfeiture (sentencing stage).

24

See figure 1 for an illustration of the life cycle involving criminal cases.

This life cycle involves a range of agency, investigative, prosecutorial,

and judicial resources to attempt to recover fraudulently obtained

taxpayer funds. Furthermore, this process underscores the resources

involved in a “pay-and-chase” approach to dealing with fraud and the

importance of preventive controls to manage fraud risks.

25

24

Civil cases are resolved through settlement or after proceedings that result in a civil

judgment. The amount of any damages to be paid is determined by the parties as part of

their settlement or is reflected in the civil judgment.

25

“Pay-and-chase” refers to the practice of detecting fraudulent transactions and

attempting to recover funds after payments have been made. The Fraud Risk Framework

describes “pay-and-chase” as a costly and inefficient model.

Page 14 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 1: Illustrative Life Cycle of Fraudulent Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster

Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Applications Involving Criminal Cases

Note: The numbers and proportions of applications and cases in the figure are illustrative.

a

Although cases that were resolved with acquittals may have had fraud-related charges, the

defendants were formally determined to not be guilty of the charges.

Page 15 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

To help combat fraud in government agencies and programs—both

during normal operations and emergencies—GAO published A

Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk

Framework).

26

Issued in 2015, the Fraud Risk Framework identifies

leading practices for managing fraud risks and encompasses control

activities to prevent, detect, and respond to fraud, with an emphasis on

prevention. As discussed in the Fraud Risk Framework, strategic fraud

risk management involves more than having controls to prevent, detect,

and respond to fraud. Rather, it also encompasses structures and

environmental factors that influence or help managers achieve their

objective to mitigate fraud risks.

The Fraud Risk Framework describes leading practices in four

components: commit, assess, design and implement, and evaluate and

adapt, as depicted in figure 2.

26

GAO-15-593SP.

Fraud Risk Management

Page 16 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 2: The Four Components of the Fraud Risk Management Framework and Selected Leading Practices

In June 2016, Congress enacted the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics

Act of 2015. This act required the Office of Management and Budget

(OMB) to establish guidelines for federal agencies to create controls to

identify and assess fraud risks and to design and implement antifraud

control activities.

27

The act further required OMB to incorporate the

leading practices from GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework in these guidelines.

In its 2016 Circular No. A-123 guidelines, OMB directed agencies to

adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their

efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control

27

Pub. L. No. 114-186, 130 Stat. 546 (2016).

Page 17 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

system that addresses fraud risks.

28

Although the act was repealed in

March 2020, the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 requires these

guidelines to remain in effect.

29

GAO also has ongoing work developing a framework to provide principles

and practices that can help federal managers mitigate improper

payments, including those resulting from fraudulent activity, in emergency

assistance programs. Specifically, the framework will incorporate

standards for internal controls and for financial and fraud risk

management practices as well as requirements from relevant laws and

guidance on improper payments.

In our first government-wide CARES Act report issued in June 2020, we

reported that the public health crisis, economic instability, and increased

flow of federal funds associated with the COVID-19 pandemic increased

pressures and opportunities for fraud.

30

We noted that recognizing fraud

risks and deliberately managing them in an emergency environment can

help federal managers safeguard public resources while providing

needed relief.

We also reported that because the government needed to provide funds

and other assistance quickly to those affected by COVID-19 and its

economic effects, federal relief programs—including those implemented

by SBA—were vulnerable to significant risk of fraudulent activities. We

further stated that managers may perceive a conflict between their

priorities to fulfill the program’s mission—such as efficiently disbursing

funds or providing services to beneficiaries, particularly during

emergencies—and taking actions to safeguard taxpayer dollars from

improper use. However, we noted that the purpose of proactively

28

Office of Management and Budget, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk

Management and Internal Control, OMB Circular No. A-123 (Washington, D.C. July 15,

2016). In October 2022, OMB issued a Controller Alert, which reminded agencies that

they must establish financial and administrative controls to identify and assess fraud risks.

In addition, OMB reminded agencies that they should adhere to the leading practices in

GAO’s Fraud Risk Management Framework as part of their efforts to effectively design,

implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks. OMB, CA-

23-03, Establishing Financial and Administrative Controls to Identify and Assess Fraud

Risk (Oct. 17, 2022).

29

Pub. L. No. 116-117, § 2(a), 134 Stat. 113, 131-32 (2020) (codified at 31 U.S.C. §3357).

These guidelines may be periodically modified by OMB in consultation with GAO, as OMB

and GAO may determine necessary.

30

GAO, COVID-19: Opportunities to Improve Federal Response and Recovery Efforts,

GAO-20-625 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2020).

Prior Reporting on Fraud

Risks and Financial

Control Weaknesses in

SBA Pandemic Relief

Programs

Page 18 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

managing fraud risks, even during emergencies, is to facilitate, not hinder,

the program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer

dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

We further reported that when emergency response situations limit the

use of preventive controls—which are the most effective means of

managing fraud risks—agencies can leverage detective controls, such as

through data collection and analysis, to help identify potential fraud more

readily and to assist in response and recovery. Specifically, the use of

data analytic tools and techniques can help programs detect potential

fraud and better understand existing and emerging risks.

In February 2023, the Comptroller General testified on fraud and improper

payments in COVID-19 pandemic relief programs.

31

He noted that SBA’s

initial approach to managing fraud risks in PPP and the COVID-19 EIDL

program, as well as in its long-standing programs, had not been strategic.

For example,

• SBA did not designate a dedicated antifraud entity until February

2022. This new entity—the Fraud Risk Management Board—is to

oversee and coordinate SBA’s fraud risk prevention, detection, and

response activities.

• SBA did not develop its fraud risk assessments for the programs until

October 2021, at which point PPP had already stopped accepting new

applications, and the COVID-19 EIDL program would stop at the end

of that year. Fraud risk assessments are most helpful in developing

preventive fraud controls to avoid costly and inefficient “pay-and-

chase” activities. For example, while the PPP fraud risk assessment

can help SBA identify potential fraud as it continues to review the PPP

loans for forgiveness, it could not be used to inform SBA’s efforts

during the initial application process.

See appendix II for additional details regarding SBA’s management of

fraud risks as the pandemic began and as SBA adapted its fraud risk

management approach for the four pandemic relief programs. See

appendix III for our recommendations to improve fraud risk management

in SBA’s pandemic relief programs, along with information on actions

taken by SBA to address them.

31

GAO, Emergency Relief Funds: Significant Improvements Are Needed to Address Fraud

and Improper Payments, GAO-23-106556 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1, 2023).

Page 19 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Other federal accountability and oversight bodies, namely the SBA OIG

and the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC), have

reported on SBA’s efforts to manage fraud risks in these programs.

32

Many of the reports produced by these bodies also contained

recommendations to SBA.

33

In addition, since 2020, SBA’s independent financial statement auditor

has made multiple recommendations to SBA to address material

weaknesses identified in controls related to SBA’s pandemic relief

programs.

34

Specifically:

• In December 2020, the auditor issued a disclaimer of opinion on

SBA’s consolidated financial statements as of and for the year ended

September 30, 2020, meaning the auditor was unable to express an

opinion due to insufficient evidence.

35

As the basis for the disclaimer,

the auditor stated that SBA was unable to provide adequate

documentation to support a significant number of transactions and

account balances related to PPP and COVID-19 EIDL due to

inadequate processes and controls.

The auditor identified several material weaknesses in controls related

to SBA’s pandemic relief programs. In total, the auditor identified

seven material weaknesses including those related to PPP loan

approvals, COVID-19 EIDL loans and advance approvals, and overall

management controls (e.g., ineffective control environment, risk

assessment processes, control activities, information and

communication processes, and monitoring processes). Overall, the

32

The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC) was established by the

CARES Act to conduct oversight of the federal government’s pandemic response and

recovery effort. The PRAC is composed of 21 federal inspectors general.

33

SBA OIG and PRAC reports, including information on recommendations and their status,

can be found on the PRAC’s website

(https://www.pandemicoversight.gov/oversight/reports).

34

A deficiency in internal control exists when the design or operation of a control does not

allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned

functions, to prevent, or detect and correct, misstatements on a timely basis. A material

weakness is a deficiency, or combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial

reporting, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the

entity’s financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely

basis.

35

SBA OIG, Independent Auditors’ Report on SBA’s FY 2020 Financial Statements, 21-04

(Dec. 18, 2020).

Page 20 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

auditor made 46 recommendations to SBA management. In

commenting on the audit, SBA stated it supported the requirements

for auditability of its financial statements and was working to correct

shortcomings for future audits.

• In November 2021, the auditor issued a disclaimer of opinion on

SBA’s consolidated balance sheet as of September 30, 2021.

36

As the

basis for the disclaimer, the auditor stated that SBA was unable to

provide adequate documentation to support a significant number of

transactions and account balances related to PPP, COVID-19 EIDL,

RRF, and SVOG due to inadequate processes and controls.

In total, the auditor identified six material weaknesses. This included

weaknesses related to PPP (both the approval and forgiveness,

among others), COVID-19 EIDL (both loans and advances), and the

accounting and monitoring of RRF and SVOG programs. Overall, the

auditor made 41 recommendations to SBA management. In

commenting on the audit, SBA stated that it did not concur with the

severity of five material weaknesses in the auditor’s report, including

those related to PPP, COVID-19 EIDL, RRF, and SVOG. SBA stated

that it had worked to establish internal controls, policies, and

procedures that addressed new legislative programs as a result of the

pandemic, and that it would take corrective actions to remediate

weaknesses and strengthen internal controls where necessary.

• In November 2022, the auditor issued a disclaimer of opinion on

SBA’s consolidated balance sheet as of September 30, 2022.

37

The

basis of the disclaimer was related to SBA being unable to provide

adequate documentation related to PPP, COVID-19 EIDL, RRF, and

SVOG.

In total, the auditor identified six material weaknesses, including those

related to controls in the PPP, COVID-19 EIDL, RRF, and SVOG

programs. Overall, the auditor made 42 recommendations to SBA

36

SBA OIG, Independent Auditors’ Report on SBA’s FY 2021 Financial Statements, 22-05

(Nov. 15, 2021). The OIG contracted with the independent auditor to conduct an audit of

SBA’s consolidated balance sheet as of September 30, 2021, and the related notes. As a

result, the auditor was not engaged to express an opinion on the other statements within

the consolidated financial statements.

37

SBA OIG, Independent Auditors’ Report on SBA’s FY 2022 Financial Statements, 23-02

(Nov. 15, 2022). The OIG contracted with the independent auditor to conduct an audit of

SBA’s consolidated balance sheet as of September 30, 2022, and the related notes. As a

result, the auditor was not engaged to express an opinion on the other statements within

the consolidated financial statements.

Page 21 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

management. In commenting on the audit, SBA noted that it had

continued making progress strengthening internal controls for

pandemic-focused programs and was dedicated to accountability and

transparency to the American public. SBA also noted that the audit

process continued to provide the agency with beneficial

recommendations that support SBA’s ongoing efforts to further

enhance its financial management practices.

Our analysis, which identified hundreds of cases and individuals charged

by DOJ as well as associated businesses, illustrates how

misrepresentations and deliberate exploitation of the programs facilitated

fraud. Our analysis also determined that the financial and non-financial

impacts of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL fraud are far reaching, but the full

extent is not yet known.

Our analysis of hundreds of cases charged by DOJ illustrates how fraud

was committed in closed cases or may have been committed in ongoing

cases, through misrepresentations and deliberate exploitation of PPP and

COVID-19 EIDL.

38

The cases and associated individuals and businesses

in our analysis are based on publicly announced fraud-related charges

38

We identified fraud cases from DOJ press releases and other public information, which

may not include all cases pursued by DOJ. Additionally, some fraud may never be

detected. Furthermore, fraud-related administrative actions levied by regulators or brought

through lawsuits by private entities or individuals are not included in our analysis. As a

result, the 330 cases we identified and analyzed may not be representative of all cases

pursued by DOJ or others. In addition, case details, such as businesses involved and

numbers of loan applications submitted, were not always available in publicly available

case documentation. Our findings, including counts of cases, individuals, and businesses,

therefore represent the lower bound of the possible characteristics of cases we identified

for this analysis.

Analysis of PPP and

COVID-19 EIDL

Charges Illustrates

Fraud Schemes and

Their Actual and

Potential Impacts

Analysis of PPP and

COVID-19 EIDL Charges

Shows the Role of

Misrepresentation and

Deliberate Exploitation in

Facilitating Fraud

Analysis of Hundreds of PPP

and COVID

-19 EIDL Cases

Identified Associated

Individuals and Businesses

Page 22 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds as of December 31, 2021.

39

Specifically, we identified 330 criminal and civil fraud cases brought by

DOJ involving PPP or COVID-19 EIDL, 91 of which involved both

programs (see fig. 3).

40

The number of cases will continue to grow. For

example, as of January 25, 2023, the SBA OIG had 536 ongoing

investigations involving PPP, COVID-19 EIDL, or both. Additionally,

Congress extended the statute of limitations for criminal and civil

enforcement for all forms of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loan fraud from

5 years to 10 years.

41

39

We selected December 31, 2021, as the ending point of our research because on

December 31, 2021, SBA stopped accepting COVID-19 EIDL applications (per

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021). PPP closed in May 2021. We acknowledge that

DOJ has continued to bring charges involving PPP and COVID-19 EIDL since December

31, 2021, and that later cases may involve more complex fraud schemes that may take

longer to investigate and prosecute. In a separate analysis of DOJ public statements and

court documentation, we reported on February 1, 2023, that from March 2020 through

January 13, 2023, 535 individuals or entities had pleaded guilty or received a guilty verdict

at trial involving PPP fraud, and 293 involving COVID-19 EIDL fraud (with 185 having

fraud-related charges involving both programs).

40

A single case—which involves fraud-related charges associated with PPP, COVID-19

EIDL, or both programs—may involve (1) a single individual or business or (2) multiple

individuals or businesses that applied for a single or multiple loans or grants. A single

case may contain a single or multiple fraud mechanisms. Out of the 330 fraud cases we

identified, 322 were criminal cases and eight were civil cases. The civil cases included in

our analysis were closed cases that reached a conclusion through settlement or judgment

of forfeiture. Ongoing civil cases were not included in our analysis.

41

PPP and Bank Fraud Harmonization Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-166, 136 Stat. 1365

and COVID-19 EIDL Fraud Statute of Limitations Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-165, 136

Stat. 1363.

Page 23 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 3: Cases Charged by the Department of Justice Involving Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19

EIDL) Fraud, as of December 31, 2021

As of December 31, 2021, 155 of the 330 cases were categorized as

closed because they reached a conclusion through guilty pleas,

settlements, guilty verdicts, or dismissals.

42

At that time, 175 cases had

not yet reached conclusion and, therefore, were considered ongoing for

the purposes of our analysis (see fig. 4).

42

Our definition of a closed case also included acquittals, but no acquittals were identified

in our population of cases. Of the 155 closed cases, five had been dismissed.

Page 24 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 4: Ongoing and Closed Cases Involving Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)

and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) Fraud, as of

December 31, 2021

Notes: This analysis is limited to the cases we identified from public sources, which may not include

all criminal and civil cases charged by the Department of Justice as of December 31, 2021.

Additionally, the status of ongoing cases may have changed since December 31, 2021.

Multiple federal law enforcement agencies investigated these 330 cases.

Federal prosecutors across the United States filed bank fraud, wire fraud,

money laundering, identity theft, and other charges against

524 individuals associated with these cases. Additionally, our analysis

identified 989 businesses that were associated with these 330 fraud

cases (see fig. 5).

Page 25 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 5: Individuals and Businesses Associated with Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL)

Fraud Cases, as of December 31, 2021

Our analysis of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases shows ineligible, non-

operating businesses applied for and obtained program funds or were

alleged to have done so. Such businesses include shell companies,

which have no employees or operations, and fictitious entities. Of the

330 PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases, 221 (or about 67 percent) involved

or allegedly involved non-operating businesses. Specifically, of the

989 businesses identified in court documents, approximately 72 percent

were identified as or alleged to be shell companies or fictitious entities,

which would make them ineligible for PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funding

(see fig. 6).

43

43

Because documents did not always explicitly note whether the businesses they named

were legitimate or fictitious, the remaining category of businesses includes potentially

fictitious businesses.

Most Charges Involved

Allegations of Non

-Operating

Businesses and

Misrepresentations of Business

and Individual Eligibility

Glossary of Key Terms

fictitious entity: fake business that is

presented as real in order to obtain Paycheck

Protection Program or COVID-19 Economic

Injury Disaster Loan funds.

shell company: a business or company that

has no employees or operations.

Source: GAO. | GAO-23-105331

Page 26 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Figure 6: Types of Businesses Identified in Paycheck Protection Program and

COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan Fraud Cases, as of December 31, 2021

a

Because documents did not always explicitly note whether the businesses they named were

legitimate or fictitious, the remaining category of businesses includes potentially fictitious businesses.

Among the cases involving shell companies or fictitious entities, those

charged obtained or, for the ongoing cases, are alleged to have obtained

approximately $388.9 million in PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds. (See text

box for illustrative example.)

Page 27 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Fraudster used multiple ineligible businesses to receive pandemic relief funds.

A fraudster submitted four Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and 10 COVID-19

Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) applications for 10 different

businesses. Those businesses included one legitimate business, eight shell companies

that had no operations or employees, and one fictitious entity. The applications used

stolen personally identifiable information and falsified monthly payroll documents and

tax forms for the businesses. The fraudster received $109,552 in PPP and $642,800 in

COVID-19 EIDL funds based on these submissions. At the same time, the fraudster

applied for a state pandemic-related relief grant and received $70,000 through that

program. The fraudster misused pandemic relief funds for personal expenses including

a diamond ring, luxury hotel stays, living expenses, and payments for personal credit

cards and student loans. The fraudster pled guilty and was sentenced to 4 years in

prison and 3 years of supervised release. The fraudster was also ordered to pay

$1,998,097 in restitution.*

*The sentencing and restitution amount for this individual were based on the fraudulent

funds received from the Small Business Administration’s PPP and COVID-19 EIDL as

well as the state COVID-19 relief fund and an equipment financing fraud scheme not

related to the pandemic.

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information and court documents. | GAO-23-105331

Some individuals who applied for PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds on

behalf of legitimate businesses misrepresented or allegedly

misrepresented their business eligibility based on program requirements.

In 52 cases, involving 89 legitimate businesses, individuals either

misrepresented or allegedly misrepresented business eligibility with false

statements on applications about their criminal record, federal debt, or

principal place of residence, among others. (See text box for illustrative

example.)

Page 28 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

Fraudsters misrepresented eligibility to receive pandemic relief funds.

Two fraudsters, an owner of a legitimate automotive business and an employee of the

business, applied for a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan certifying no prior

felony charges. However, at the time the owner was facing charges of wire fraud and

money laundering. The fraudsters received $210,000 in PPP funds based on the

application. In addition to misrepresenting eligibility, the fraudsters misused loan

proceeds. While agreeing on the application to use PPP funds for payroll, they paid

past-due truck payments and purchased various truck parts. Both pled guilty. The

owner was sentenced to 3 years in prison and 3 years of supervised release. The

employee was sentenced to 1 year and a day in prison and 3 years of supervised

release.* The employee was ordered to pay $220,500 in restitution for the PPP loan

application fraud.

*The sentencing for the business owner is based on the fraudulent funds received from

PPP, as well as other charges not related to SBA pandemic relief.

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information and court documents. | GAO-23-105331

The 330 fraud cases we analyzed showed that individuals used or were

alleged to have used various and multiple types of falsehoods to obtain

PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds. This could involve the falsification of

documents, such as tax forms, payroll documentation, and bank

statements to apply for funds. Additionally, allegations involving false

information about other elements of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loan

applications, such as employee counts and payroll amounts, were

prevalent in DOJ cases.

Our analysis showed that 227 of the 330 PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases

(or 69 percent) involved falsification or alleged falsification of tax or other

documents, such as payroll documentation or bank statements.

Specifically, 190 (or 58 percent) of the cases involved allegations of tax

document falsification, showing that tax forms may have been commonly

forged or altered. Further, 240 cases (or 73 percent) involved schemes in

which individuals created fictitious employees and inflated employee

counts to obtain more funds or were alleged to have done so.

The cases also involved allegations of various types of identity theft. This

involves the theft of personally identifiable and business information or

the use of synthetic identities to obtain PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds.

Our analysis showed that 63 of the 330 PPP and COVID-19 EIDL cases

(or 19 percent) involved allegations of theft of personally identifiable

information and 17 cases (or 5 percent) involved allegations of using

another business’s information to obtain PPP or COVID-19 EIDL funds.

Additionally, we identified 50 cases (or 15 percent) that involved

Charges Involved Allegations

of Individuals Obtaining PPP

and COVID

-19 EIDL Funds by

Falsifying Documentation and

Stealing Identities

Glossary of Key Terms

false attestation: falsified statement(s) on an

application.

synthetic identity: a fabricated identity using

fictitious information in combination with

stolen information, such as a Social Security

number.

Source: GAO. | GAO-23-105331

Page 29 GAO-23-105331 COVID Relief

allegations of individuals stealing and wrongfully using Social Security

numbers (SSN) to apply for PPP and COVID-19 EIDL funds. Another

11 cases (or 3 percent) involved allegations of synthetic identity fraud

where individuals fabricated an identity by using fictitious information in

combination with stolen information such as an SSN. (See text box for

illustrative example.)

Fraudster used stolen personal information, shell companies, and false

attestation to obtain pandemic assistance.

A fraudster applied for five Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans for three

different shell companies that had no operations or employees. On one application, the

fraudster used a deceased victim’s name to apply for a PPP loan for the shell

company. On another PPP application, the fraudster created a synthetic identity by

combining his name with his father’s Social Security number (SSN) instead of using his

own SSN. On one of the applications, the fraudster certified no prior felony charges,

when he had charges of tampering with a government record. The fraudster also

falsely represented that the businesses had multiple employees, when they had none.