Gregory P. Beeler, Ph.D., M.A.,

Jennifer L. Murphy, Ph.D.,

Paul R. King, Ph.D., &

Katherine M. Dollar, Ph.D.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

VA Western New York Healthcare System

Buffalo, NY 14215

November 1, 2016

Veterans Health Administration

Washington, DC 20420

Gregory P. Beehler, Ph.D. , M.A.

Jennifer L. Murphy, Ph.D.

Paul R. King, Ph.D.

Katherine M. Dollar, Ph.D., ABPP

Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for

Chronic Pain: Therapist Manual

Version 2.0

ii

BRIEF CBT-CP IS FOR USE BY QUALIFIED CLINCIANS ONLY. THIS

PROTOCOL SHOULD BE REVIEWED IN ITS ENTIRETY BEFORE

BEING APPLIED TO PATIENT CARE.

THIS MANUAL AND RELATED MATERIALS SHOULD NOT BE

USED FOR RESEARCH WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

AND UPDATES PLEASE CONTACT:

Gregory P. Beehler, Ph.D., M.A.

Associate Director for Research

VA Center for Integrated Healthcare

VA Western New York Healthcare System

3495 Bailey Avenue

Buffalo, NY 14215

Phone: 716-862-7934

Email: [email protected]

Homepage: www.mirecc.va.gov/cih-visn2/

Suggested citation: Beehler, G. P., Murphy, J. L., King, P. R., & Dollar, K. M. (2021). Brief Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain: Therapist Manual, Ver 2.0. Washington, DC: U.S. Department

of Veterans Affairs.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support for developing this treatment manual was provided by the Department of Veterans

Affairs (VA) Center for Integrated Healthcare (CIH). Use of the facilities and resources were

provided by the VA Western New York Healthcare System at Buffalo and James A. Haley VA

Medical Center (Tampa, FL). The information provided in this document does not represent the

views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

We wish to expressly thank Jennifer L. Murphy, Ph.D., John D. McKellar, Ph.D., Susan D. Raffa,

Ph.D., Michael E. Clark, Ph.D., Robert D. Kerns, Ph.D. and Bradley E. Karlin, Ph.D., the authors of

the original Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain among Veterans: Therapist Manual,

who laid the foundation for this adaptation.

We also thank Drs. Thomas Farrington and Denise Mercurio-Riley who assisted in reviewing and

providing feedback in the development of this manual.

Most importantly, we wish to offer sincere thanks to the dedicated clinicians and Veterans who

inspired us to adapt this intervention.

iv

PREFACE

BACKGROUND

This manual includes information regarding the development of Brief Cognitive Behavioral

Therapy for Chronic Pain (Brief CBT-CP). The project is being led by contributors from CIH and

James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital and developed for use by behavioral health providers who: a)

identify the need for a brief, focused intervention for chronic pain, or b) are not working in a

setting that can accommodate a full-length CBT-CP protocol. Incorporation of a Brief CBT-CP

treatment may be most appropriate for (but not limited to) providers working in the following

settings: Primary Care-Mental Health Integration (PCMHI), home-based primary care (HBPC),

outpatient/specialty mental health, or individuals working in consultation-liaison roles with

medical clinics (e.g., oncology, endocrinology, etc.). Individuals who are experienced in

delivering specialty pain interventions may also find benefit in this protocol, particularly if

briefer alternatives are needed based on setting-specific demands or patient preferences.

ORGANIZATION OF THE MANUAL

This manual is organized into multiple chapters. The initial chapters provide a rationale for

developing the brief intervention and an overview of foundational material about chronic pain.

The structure and components of Brief CBT-CP are summarized, and key contextual and clinical

considerations for addressing chronic pain are reviewed. Two case examples illustrate

indications for Brief CBT-CP. An approach to addressing measurement-based care with Brief

CBT-CP is described in depth as well as a chapter regarding how to engage new patients in

treatment.

Next, each treatment module is presented. The protocol requires that modules one and six are

stable anchors to begin and end the protocol. However, modules two through five can be

presented in any order, depending on the preference of the patient and clinical judgment of the

therapist. An important feature of each chapter is the inclusion of Therapist Guides. Each

module guide provides an overview of each appointment, including the key elements and

general recommended structure. They provide suggested language to introduce topics and key

talking points with patients. Module Outlines are one-page summaries of required steps to be

conducted in each appointment. These can be referenced in real time during your

appointments to keep you on track during your 30-minute appointment. Patient handouts are

an integral part of this treatment and in the first appendix for easy printing or duplication.

Several additional appendices include detailed information about pain conditions, specialty

pain treatments, and relevant mobile apps that can be used as an adjunct to Brief CBT-CP.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. RATIONALE FOR DEVELOPMENT OF BRIEF CBT-CP……………………………………………..1

2. FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN SELECTING BRIEF CBT-CP……………………………………4

3. INTRODUCTION TO CHRONIC PAIN……………………………………………………………………7

4. CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS WHEN WORKING WITH PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC

PAIN…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..14

5. AN OVERVIEW OF BRIEF CBT-CP MODULE STRUCTURE…………………………………….18

6. MEASUREMENT-BASED CARE (MBC) WITH THE PEG………………………………………..21

7. THE HOOK: OFFERING PATIENTS BRIEF CBT-CP………………………………………………..27

● BRIEF CBT-CP PROTOCOL AND THERAPIST GUIDE ●

MODULE 1: EDUCATION AND GOAL IDENTIFICATION………………………………………….35

MODULE 2: ACTIVITIES AND PACING…………………………………………………………………..47

MODULE 3: RELAXATION TRAINING……………………………………………………………………59

MODULE 4: COGNITIVE COPING 1……………………………………………………………………….71

MODULE 5: COGNITIVE COPING 2……………………………………………………………………….80

MODULE 6: THE PAIN ACTION PLAN……………………………………………………………………88

REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………………………………….98

APPENDIX 1: PATIENT HANDOUTS BY MODULE…………………………………………………101

APPENDIX 2: PAIN CONDITIONS………………………………………………………………………..142

APPENDIX 3: TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR CHRONIC PAIN……………………………………148

vi

APPENDIX 4: MOBILE APPS FOR PAIN AND RELATED CONCERNS…………………...….156

APPENDIX 5: GUIDED IMAGERY SCRIPT……………………………………………………………..159

1

1. RATIONALE FOR DEVELOPMENT OF BRIEF CBT-CP

The full course of CBT-CP treatment typically requires eleven 50-minute sessions delivered by

therapists with specialty training in behavioral medicine or those providers specially trained as

part of the VA’s EBP program. This approach of treating chronic pain as a specialty mental

health intervention is time and resource intensive. Because of the widespread occurrence of

chronic pain among the Veteran population, there is increased interest among VA providers to

be able to offer briefer versions that can be used in more flexible formats in a wider variety of

settings. Thus, this manual serves the goal of making CBT-CP more widely available in a

briefer format. Our hope is that by offering Brief CBT-CP, the overarching goal of improving

Veteran outcomes through chronic pain self-management will be met more effectively.

1.1. EVIDENCE THAT BRIEF TREATMENTS MAY WORK FOR CHRONIC PAIN

Research on briefer psychological treatments for addressing chronic pain are growing. There

are multiple factors and corresponding lines of research that underlie the development of Brief

CBT-CP. First, because chronic pain is a common condition, multiple types of interventions are

necessary to treat pain in a sufficiently patient-centered way across diverse settings and

populations. A brief treatment may be especially well suited for addressing pain early in the

trajectory of care with the goal of preventing functional disability and distress. Second, prior

research suggests that briefer versions of CBT-CP offered in primary care and various other non-

mental health settings are effective (Ahles et al., 2006; Buszewicz et al., 2006; S.K. Dobscha et

al., 2009; Lamb et al., 2010; Martinson, Craner, & Clinton-Lont, 2020; Moore, Von Korff,

Cherkin, Saunders, & Lorig, 2000; Smith & Torrance, 2011; Von Korff et al., 1998; Wetherell et

al., 2011). Since first developing Brief CBT-CP in 2017, subsequent evaluation has indicated that,

on average, participating in Brief CBT-CP is associated with clinically significantly improvement

in a composite measure of pain intensity and pain-related functional impairment (Beehler et al.,

2019). Additionally, patients report high levels of satisfaction and acceptability of Brief CBT-CP

(Beehler et al., in press). Third, providing psychological treatment in primary care is especially

important given that over half of patients in primary care report chronic pain (Kerns, Otis,

Rosenberg, & Reid, 2003). Primary care providers find pain management especially challenging

(Matthias et al., 2010) and, according to Dobscha and colleagues, have reported dissatisfaction

with their ability to provide optimal pain relief for their patients (2008). Fourth, chronic pain

commonly co-occurs with mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Thus, mental health providers may be especially well-suited for addressing chronic pain and

associated distress given the common CBT-based model of intervention. Finally, local

availability of pain resources and interventions may vary considerably across clinics. Thus, Brief

CBT-CP provides an additional, more accessible alternative.

2

1.2. BRIEF CBT-CP: ADAPTED FROM THE VA EBP

Brief CBT-CP as described in this manual has been adapted from the full-length VA treatment

(Murphy et al.). The authors of Brief CBT-CP, who are subject matter experts in the areas of

chronic pain management and integrated care, developed the protocol with several factors in

mind. Research indicates that CBT-CP is an effective treatment for chronic pain, but dismantling

studies do not provide sufficient guidance to suggest which specific components of CBT are

responsible for effective treatment outcomes. Thus, Brief CBT-CP includes an adapted version

of each key CBT-CP element: psychoeducation/goal setting; behavioral skills: activities,

pacing, and relaxation training; cognitive coping; and relapse prevention. Brief CBT-CP mirrors

the full-length CBT-CP currently disseminated throughout the VA as part of the EBP initiative

(Stewart et al., 2015).

1.3. BRIEF CBT-CP EMPHASIZES PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOMES

A key component of this protocol is the use of patient-reported outcome measures

throughout the intervention. Use of brief validated measures to capture patient-reported

outcomes (e.g., routine assessment of pain intensity, distress, functional interference, and

others) at each module are strongly recommended in order to inform both patient and provider

about patient response to treatment. Previous research has indicated that routine outcome

monitoring is important for identifying patients who are not responding to treatment, with

continued monitoring useful for capturing patients’ response to treatment modifications

(Carlier et al., 2012; Scott & Lewis, 2014). Routine outcome monitoring will also aid the provider

in identifying patients who need a “step up” to a higher level of care. Specific instruction in

conducting measurement-based care as part of Brief CBT-CP is provided in a later chapter.

1.4. BRIEF CBT-CP IS DESIGNED FOR A DIFFERENT SETTING AND PURPOSE

Although Brief CBT-CP is not designed exclusively for primary care settings, efforts were made

to adapt CBT-CP to the PCMHI service delivery platform that has relatively unique features,

such as sessions of 30 minutes or less, highly focused brief assessments, an emphasis on

improving functional outcomes, and an emphasis on early detection and prevention.

Brief CBT-CP is designed to introduce patient self-management, improve pain self-efficacy,

reduce functional limitations, and potentially reduce self-report ratings of pain and negative

impacts of pain. Brief CBT-CP may be a used in a variety of ways depending on the clinical

context, provider, and patient. For example, a PCMHI provider may wish to use Brief CBT-CP for

patients with distress and functional limitations that stem from chronic pain. Specialty mental

health providers, behavioral medicine providers, or those in consultation-liaison roles may wish

to use Brief CBT-CP alone or as an adjunct to other medical or psychological therapies. Similarly,

even a pain specialist who usually provides full-length CBT-CP may wish to use the brief version

to meet the needs of patients who prefer or need a shorter treatment.

3

After a course of Brief CBT-CP, there are several potential options for disposition of the patient.

For some, no additional treatment will be necessary. Other patients may benefit from

occasional follow-up or booster sessions over the subsequent months to help with fine-tuning

the application of skills developed in Brief CBT-CP. Some patients may choose to continue with

their routine mental health treatment focused on depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric

concerns. Other patients may ultimately benefit from continuing on with a full course of CBT-CP

or additional pain-related psychosocial and rehabilitative interventions.

4

2. FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN SELECTING BRIEF CBT-CP

2.1. BEFORE BEGINNING BRIEF CBT-CP

Selection of this protocol assumes that providers have identified that brief intervention for

pain-related issues is clinically indicated. Because detailed training in the foundational and

functional elements of CBT clinical skills are beyond the scope of this manual, we recommend

that providers who wish to implement Brief CBT-CP have completed prior training in the basic

principles of CBT.

NOTE: Brief CBT-CP assumes that the patient has completed at least one appointment with a

mental health provider who has conducted an initial assessment appropriate to the practice

setting (e.g., functional assessment and mental health screenings typical of the PCMHI

setting; psychosocial history for a specialty mental health clinic).

2.2. ADDING BRIEF CBT-CP TO YOUR CURRENT PRACTICE: PROVIDER AND

SETTING FACTORS

Adopting a patient-centered stance is essential for conducting CBT-CP, including this brief

version. Following the biopsychosocial model, a patient-centered approach is required so that

the therapist can use patient-identified goals to direct the course of care. Patients are likely to

have a variety of concerns that are impacted by their experience of chronic pain. Thus, it is

essential to elicit from them their primary concerns. In this way, patient-centeredness is not

only a general approach to engaging the patient, it is critical for ensuring Brief CBT-CP is being

applied in a way that will be most useful.

This protocol has been designed to meet the needs of generalist mental health providers. It is

therefore important to consider that, at times, additional support from specialists may be

necessary. We advise that you identify your clinic or facility’s behavioral medicine or chronic

pain specialist(s) who can provide additional clinical support to you or act as an additional

referral source should your patient wish to engage in longer-term treatment or require a

higher level of care. It may also be helpful to coordinate care with the patient’s prescriber who

will play a key role in medical management of pain. The prescriber may find it valuable to know

that the patient is working toward better self-management.

5

2.3. DETERMINING WHO MIGHT BENEFIT FROM BRIEF CBT-CP

Brief CBT-CP will not be suitable for all patients, so clinical judgment must be used when

determining who might be best served by Brief CBT-CP. Patients who are particularly likely to

benefit from Brief CBT-CP include those with one or more of the following characteristics:

• Mild to moderate functional impairment and distress

• No severe mental health disorder or substance use disorder impacting overall function

or suggesting imminent safety risk

• Patient receptiveness to non-pharmacological self-management approaches for pain

Note: The above characteristics are comprised of suggestions only and should not be

interpreted as a list of inclusion criteria.

Finally, we provide two prototypical examples of patients who are appropriate for Brief CBT-CP

below:

2.4. BRIEF CBT-CP CASE EXAMPLE 1: PCMHI SETTING

Jeff is a 26-year-old White Veteran who recently enrolled in VA primary care services after

separating from active service in the Marine Corps six months ago. Routine mental health

screening by his primary care provider resulted in a referral to PCMHI staff for concerns related

to mood. Further evaluation by the clinic’s psychologist uncovered that chronic low back pain

stemming from his combat deployment is a significant contributor to his feeling irritable, and

that over-the-counter analgesics have offered limited pain relief. Jeff noted that his back pain,

rated as a five on the Numeric Rating Scale, has increasingly interfered with his sleep, ability to

sit through college classes, and interactions with his young son. He has become increasingly

concerned that pain will impact his long-term goal of operating his own business. He is

frustrated by what he describes as a near constant dull ache over the past two years, and

wonders if it will improve. Considering Jeff’s endorsement of moderate chronic pain and its

interference with daily activities, the clinic psychologist discusses both mood and pain

management options with Jeff and his primary care provider. Though Jeff has never attempted

cognitive behavioral self-management of his pain symptoms, he appeared eager to learn more

about managing pain, particularly through implementation of techniques that he can use on his

own. Further, he wishes to receive the bulk of his medical and mental health care in his primary

care clinic. Therefore, Jeff and his treatment team agree to incorporate Brief CBT-CP into their

collaborative approach to care.

2.5. BRIEF CBT-CP CASE EXAMPLE 2: BEHAVIORAL MEDICINE SETTING

Paulette is a 65-year-old African American Navy Veteran who is finishing treatment for colon

cancer. Her level of fatigue has increased as she completes her course of chemotherapy, which

has contributed to decreased mood and limited engagement in hobbies and social activities.

6

She has a relatively new post-surgical abdominal pain following her initial cancer surgery six

months ago. Additionally, she was diagnosed with moderate arthritis of the right knee over 10

years ago which has become more bothersome in the last several months. The infusion clinic

nurse identified that Paulette’s Numeric Rating Scale for pain is a seven, suggesting clinically

significant pain in need of additional intervention. Upon further discussion with the infusion

nurse, Paulette also reported increased frustration with her multiple sources of pain that are

clearly interfering with daily routines. The infusion nurse informs the oncologist who suggests a

new course of NSAIDs with the option of as-needed hydrocodone for more significant pain

flare-ups. Paulette agrees to try the NSAIDs, but is disinclined to use opioids due to concerns

over side effects. The oncologist also requests a referral from the behavioral medicine

consultant who contacts Paulette during her last chemotherapy treatment the following week.

Paulette reports that her pain is slightly better using the new medication but continues to be

disruptive. She also reports moderate depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9. Paulette does not

use any non-prescription drugs, but reports that she has been consuming more alcohol recently

in the evenings to help with sleep. As Paulette has been reporting to the VA frequently over the

last nine months since first diagnosed with cancer, she is eager to finish her treatment but does

not want to engage in extended sessions of psychotherapy. She is, however, willing to try the 6-

week course of Brief CBT-CP to help with pain management.

7

3. INTRODUCTION TO CHRONIC PAIN

3.1. WHAT IS PAIN?

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is defined as an

unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue

damage, or described in terms of such damage (IASP, 1994). This definition stresses that pain is

both a subjective physical experience (i.e., unpleasant bodily sensations) and emotional

experience (i.e., distress related to bodily sensations).

3.2. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ACUTE AND CHRONIC PAIN

Pain can be either acute or chronic in nature (Institute of Medicine, 2011) as described below:

Acute pain has a short duration and is typically characterized by an identifiable injury or

disease. Some acute pain is expected to occur in response to health events, such as childbirth

or following surgery. Acute pain usually subsides over time as the body heals, and often

responds to standard medical treatments.

Chronic pain is an ongoing or recurrent pain lasting beyond the usual course of acute illness or

injury. Chronic pain typically lasts more than three to six months and adversely affects the

individual’s well-being. There may not be a clear underlying physiological cause to chronic pain.

Table 1. COMMON SOURCES OF PAIN

Common Sources of Pain

Acute

Chronic

Infection

Migraine/headache

Dental conditions

Arthritis

Burns

Fibromyalgia

Trauma

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Surgery, other procedures

Trauma

Childbirth

Shingles

Musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., low

back pain)

Note: A detailed listing of additional pain conditions is located in the appendices.

8

Although it is important to adequately treat both acute and chronic pain, this manual focuses

only on the treatment of chronic pain. Psychosocial treatment of chronic pain is especially

important because of the well-established connection between chronic pain and diminished

quality of life, functional limitations, and psychological distress.

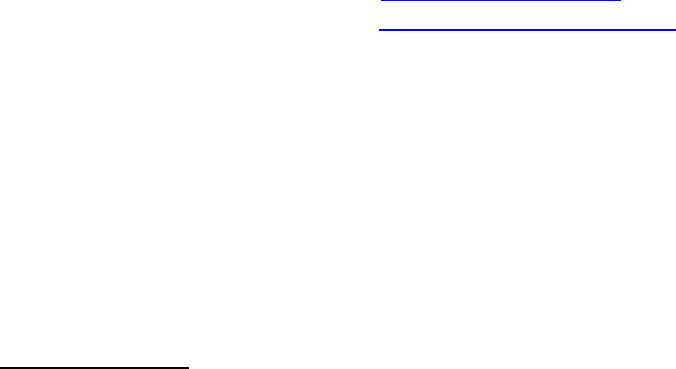

3.3. ADDRESSING CHRONIC PAIN IN THE VA: THE STEPPED CARE MODEL FOR

PAIN MANAGEMENT

There is a wide array of treatments for individuals with chronic pain. As shown in Figure 1, the

VA has adopted a stepped care model for pain. Stepped care is designed to adjust the intensity

of intervention based on patient presentation and response to care. The foundational step of

the VA model reflects the importance of routine self-care, from weight management to being

engaged in a safe and supportive social and physical environment. Step 1 includes care from

Patient Aligned Care Teams, or PACTs, who manage the majority of patients with chronic pain.

In the event that additional intervention is needed beyond services offered in PACTs, the

second step of this model includes referral to chronic pain specialists. The third step of care is

reserved for the most complex patients who require treatments such as coordinated

interdisciplinary programs. At all levels, stepped care for chronic pain stresses the importance

of a biopsychosocial perspective which considers not only traditional biomedical factors

(underlying pathology, pharmacological treatment, brief advice administered by a medical

provider) but also the psychological, behavioral, and social factors that impact Veterans with

chronic pain. Furthermore, stepped care at all levels endorses team-based approaches to care

with an increasing emphasis on patient self-management approaches.

Although the VA stepped care model suggests certain services for each step, the actual

availability of these services may vary by location. For example, Step 1 includes support from

the PCMHI provider in variety of ways, including Brief CBT-CP. PCMHI providers at a given

facility may or may not be prepared to provide support specifically for chronic pain

management. However, most are likely able to assist patients in adjusting to their pain

condition or by addressing comorbid mental health conditions. Alternatively, some PCMHI

providers will have behavioral medicine backgrounds that will allow them to take a more

diverse role in chronic pain management. This manual is well-suited to PCMHI providers who

are either new to chronic pain management or who desire to implement a brief treatment for

pain adapted from an evidence-based protocol.

9

Figure 1. VA's Stepped Care Model for Pain Management

3.4. UNDERSTANDING CHRONIC PAIN

Chronic pain is a complex phenomenon. As such, there are a number of conceptual models that

have been developed to explain the etiology and nature of pain. Currently, the biopsychosocial

model (Engel, 1977) is the most widely accepted approach to understanding chronic pain. The

biopsychosocial model (see Figure 2 below) suggests that the experience of pain is

multifactorial, with a wide array of physical, psychological, social, and other environmental

factors that may play a role in perpetuating pain.

For example, the biopsychosocial model suggests that in addition to the physiological basis of

their pain, an individual’s thoughts, behaviors, and social relationships are all important

contributors. Importantly, this model suggests that there are multiple points of intervention for

addressing chronic pain, from medical treatments, to psychological interventions, to

modifications in one’s social environment.

10

Figure 2. The Biopsychosocial Model

3.5. TREATING CHRONIC PAIN

Chronic pain can be treated through a wide array of modalities. Some of the most common

biomedical approaches are summarized in Table 2, with additional details and descriptions of

these approaches available in the appendices. Although treatments that address the

physiological contributors to pain are important to pain management, individual responses to

these treatments may vary considerably. Often, patients and providers will need to work

together to identify the best approaches for optimal pain care.

In addition to these biomedical-based treatments that address the physical domain, applying

self-management and relevant psychological and physical therapies are essential since all

dimensions of the biopsychosocial model must be addressed.

11

Table 2: BIOMEDICAL MODALITIES FOR TREATING CHRONIC PAIN

3.6. COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY FOR CHRONIC PAIN (CBT-CP)

There are several evidence-based psychological therapies that have been shown to improve

outcomes for patients with chronic pain. Among these, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a

widely researched, time-limited psychotherapeutic approach applied to numerous mental and

behavioral conditions. CBT involves a structured approach that focuses on the relationships

among cognitions (or thoughts), emotions (or feelings), and behaviors. Treatments based on

cognitive behavioral theory have been successfully applied to the management of chronic pain,

either delivered alone or as a component of an integrated, multimodal, and interdisciplinary

pain management program. Evidence suggests that CBT-CP improves functioning and quality of

life for a variety of chronic pain conditions (Williams, Fisher, Hearn, & Eccleston, 2020).

CBT-CP is an approach rooted in the development of a strong therapeutic relationship that

encourages clients to adopt an active, problem-solving approach to cope with the many

challenges associated with chronic pain (Burns et al., 2015). Currently, the VA has endorsed

CBT-CP and developed a full-length treatment currently available as part of the Evidence-Based

Psychotherapy program (Murphy et al.). Use this link to download the manual.

Biomedical Modalities for Treating Chronic Pain

Pain-relieving medications (i.e., analgesics)

• Non-opioid analgesics

• Opioid analgesics

• Topical analgesics

• Muscle relaxants

• Adjuvant analgesics

• Headache-specific analgesics

Invasive medical treatments

• Epidural steroid injections

• Nerve blocks

Non-invasive treatments

• Physical therapy

• Cold/heat

• TENS

• Complementary and Integrative Treatments

12

The value of CBT-CP is its focus on improving patient self-management to positively impact

the chronic pain cycle shown below. The pain cycle (see Figure 3) illustrates how the

experience of pain can lead to maladaptive changes in behavior that ultimately lead to

increased distress, decreased activity, and a chronic course of pain. The experience of pain

often leads to decreased activity out of fear of increased pain associated with movement.

Limiting one’s otherwise beneficial activities can lead to physical deconditioning and

disengagement from pleasurable or otherwise meaningful activities and life events. The

persistence of chronic pain and disengagement from valued activities can lead to increased

emotional distress, negative thinking, and decreased motivation that result in further

disengagement. The resulting state of disability is reinforced by ongoing maladaptive coping.

Figure 3. The Chronic Pain Cycle

CBT-CP can provide patients with both a new perspective and new coping skills to increase

self-efficacy and break the cycle of chronic pain. The goal of CBT-CP is to identify and modify

maladaptive cognitions and behaviors that perpetuate pain-related distress and dysfunction.

CBT-CP is based on cognitive behavioral theory which focuses on the impact of cognitive

processes on affective states and resulting behaviors (Beck, 1995). The suffering associated

with chronic pain often leads to a maladaptive disengagement from people, places, and events.

Like all CBT approaches, CBT-CP draws from both behavioral theory and cognitive theory.

Behavioral theory is based on the premise that distressed individuals get a very low rate of

positive reinforcement from their environment. Because they experience few benefits of

engaging in activities (and engaging in certain activities may lead to more pain), they tend to

disengage. As they disengage from activities and people, they become more distressed and

enter a cycle of inactivity and spiraling depression. A key target of behavioral intervention is

13

behavioral activation (i.e., helping people to re-engage in pleasurable events or find new

activities).

In the case of chronic pain, certain physical movements or activities can lead to increased pain.

Pain may also be interpreted as a warning sign that certain movements or activities are unsafe

and result in harm or damage. It is not difficult to see why people with chronic pain stop

participating in certain events. Thus, we must find new ways of engaging in favorite activities

that will be less likely to produce pain. Ways of addressing physical inactivity, such as pacing,

are a key behavioral component of CBT-CP.

According to cognitive theory, the way we perceive, think about, or interpret an event impacts

our emotional experiences. Therefore, monitoring and understanding our thoughts is essential

to facilitating change. Automatic thoughts are those that occur immediately in response to an

event/situation, but often go unnoticed. Sometimes automatic thoughts occur in relation to

internal events, such as increased pain. If the automatic thought is unhelpful or maladaptive,

we may experience an unpleasant reaction at the emotional, physiological, and/or behavioral

level.

A particularly common type of these automatic negative thoughts around pain is known as

catastrophizing. Catastrophizing is a distorted thought process of imagining or assuming that

pain will lead to the worst or most intolerable outcome, such as “My pain will never go away”

or “My pain will ruin my life.” Treating the cognitive components of chronic pain includes

teaching patients to self-monitor and ultimately modify their maladaptive negative cognitions

in favor of more balanced thinking.

3.7. SUMMARY

The key operational components of CBT-CP involve breaking the chronic pain cycle by:

• Increasing engagement in healthy and pleasurable activities

• Enhancing positive pain coping skills, such as pacing and relaxation activities

• Correcting faulty assumptions and thoughts about pain

• Improving self-efficacy regarding management of pain symptoms

14

4. CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS WHEN WORKING WITH PATIENTS WITH

CHRONIC PAIN

4.1. INTRODUCTION

Veterans who have chronic pain present with various levels of functional impairment and all

have their own pain story. In addition to the physical strain of managing chronic pain each day,

their suffering may have significant emotional and social dimensions as well. Often times,

Veterans with pain have seen numerous healthcare providers regarding their condition and

may feel frustrated with not receiving answers that they find satisfying regarding the etiology

or treatment of their pain. Perhaps most importantly, those with chronic pain may feel as if

they have not been “heard” adequately by providers. Various patient reactions can be driven

by the perception that insufficient time, attention, or care has been paid by healthcare

professionals when they are suffering each day.

As with all therapies, using CBT for the management of chronic pain requires the development

of a strong rapport. While Veterans may resist being introduced to another provider, especially

one in the mental health field, creating an environment where the Veteran is heard and

believed fully is a key to success. It is not the role of the therapist to determine the veracity of

the physiology of the pain complaint - pain is a subjective experience that is affected by

various factors. The functional impacts experienced by the Veteran should be the focus of

treatment, with clear education and direction offered as ways to positively alter the pain

experience.

While there are many challenges that may arise when treating Veterans with chronic pain,

some common topics that may impede therapeutic progress (with ideas for how to address

these complex issues) are reviewed in this section.

4.2. LOSS, GRIEF, AND ACCEPTANCE

Those with chronic pain may display certain responses to their condition and it can be

beneficial to help them identify and understand what they are feeling. For many, adjusting to

pain-related losses is one of the biggest barriers to treatment progress. Loss of identity,

confidence, well-being, and relationship/vocational roles are frequently recurring issues. Since

it is challenging to cope with and accept that the “old me” is gone, it is important to normalize

this response when working with patients since they have experienced a difficult and

unexpected shift.

It may be useful for both patient and therapist to conceptualize the advent and experience of

chronic pain as a significant loss. Kubler-Ross’ well-known and non-linear five stages of grieving

(Kubler-Ross, 1972) can be applied to better process the emotional process. The denial stage

may involve being “stuck” in the biomedical model with cognitions such as, “there must be

something to fix this.” Anger is common throughout the chronic pain experience. Individuals

15

may feel frustrated with the perception that doctors are not helping them or loved ones do

not understand. They may also feel anger about the perceived injustice of their situation -

dealing with pain every day that is not their fault, not being able to do what they want, finding

little relief in treatments. Those reactions may be even more extreme in those that are

younger since it feels particularly unfair. Bargaining and “if only” thoughts as well as feelings of

depression around the reality of living with pain are often present.

Acceptance, the final “stage,” does not imply that it is “okay” to have chronic pain or that the

person is “fine with it.” Patients may react negatively to the word “acceptance” and it is

important to differentiate an active acceptance versus a passive giving up. Quite the opposite,

actively accepting that life has changed and may be very different than what was previously

hoped for or planned is critical in moving forward. There is no suggestion in these stages that

one should “get over it” but instead be able to eventually ask themselves, “now what?”

Acceptance is a process and it takes time. While there is no right way to grieve the losses that

accompany life with a chronic medical condition, it may be helpful to encourage patients to

concentrate on living the life they have instead of focusing on the one that used to be. These

are difficult concepts to discuss, but being open about them helps individuals feel better

understood, less alone in their experience, and better able to take steps toward self-

management. Life can still be meaningful and fulfilling even when someone has pain, even if it

looks different than what was originally imagined.

Use of measures, such as the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (McCraken, Vowles, &

Eccleston, 2004), may provide helpful information regarding where someone is in the grieving

process as well as evidence of positive progress during treatment.

4.3. MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

When treating individuals with chronic pain, issues frequently arise around medications and

medical procedures. Some Veterans may be highly focused on obtaining a particular

medication or treatment or they may be frustrated by pills being “pushed” on them without

alternatives offered. Regardless, because medications are typically a first line treatment for

pain, they are often an integrated part of daily life.

One frequent medication-related issue that arises in the context of treating individuals with

chronic pain involves the use of opioid analgesics. Opioids have increasingly been prescribed to

treat chronic pain in recent years, but an increased risk of adverse events (including accidental

overdose) has led to heightened regulation around their use. A lack of evidence supporting

long-term opioid therapy as well as side effects such as sedation, constipation, and the

possible need for tolerance-related dose escalation are all areas of concern. Veterans who

have had opioids decreased or discontinued may be opposed to these changes, upset, and

angry. When this is the case, medications may become a focus area by the patient, leaving

clinicians feeling a sense of helplessness and desire to “resolve” the issue.

16

Not specific to opioids is the more general belief by Veterans that "there must be something"

that can reduce their pain. This manifests in many forms, from a medication that they have

seen advertised on television to a firmly held conviction that they “need” surgery because a

physician mentioned it many years ago. Regardless of the details, this supports a belief that

pain is unidimensional and that a medically driven “fix” exists.

Educating patients about the biopsychosocial approach to pain and the many factors that can

impact the pain experience can be helpful. Allowing Veterans to vent about their medical

frustrations may be necessary, but allowing sessions to be derailed by these tangents is

problematic. Clinicians should acknowledge patient frustrations, encourage them to speak to a

prescriber, and then redirect the focus back to the skills that can be addressed in this

treatment. While therapists sometimes feel as if they are being insensitive or unsupportive by

providing such clear redirection, it is most therapeutic for patients to focus on what they can

change and control versus external factors.

4.4. OPIOID USE DISORDER

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) is a DSM-5 diagnosis signifying a problematic pattern of opioid use

associated with impairment and distress. In addition, at least two of a group of other

symptoms must be present, including taking more or using more for than intended, ongoing or

repeated attempts to control use, related physical or psychological problems, and spending

excessive time in opioid-related activities. Due to the nature of opioid analgesics, developing

physiological dependence over time as one does with nicotine is expected and does not

indicate problematic use by patients. However, once opioids become a focus of attention with

various related adverse consequences, patients should be evaluated for OUD.

Some Veterans on opioids may struggle with suggested changes in their medication regimen.

They may resent feeling labeled as “drug seeking” when they request increased doses to feel

better, often a result of tolerance. They may be angered with suggestions to decrease or

discontinue opioids for risk mitigation when they are pleased with opioids’ effects, even if

those do not include significant pain reduction. Furthermore, since opioids were typically

initiated by a prescriber, they may feel “punished” with alterations in dosing schedules. In

these cases, it is again important to acknowledge and normalize Veterans’ feelings. The focus

should then return to the message that pain is multidimensional and must be addressed from

various approaches. While medication may provide limited relief, the skills being reviewed in

Brief CBT-CP can help improve overall quality of life. When Veterans are fixated on idealizing

medications, it may be useful to return to the facts that have been gathered from them

regarding their less than ideal level of functioning. Finally, it may be helpful to remind patients

that they are in control of using the skills in this treatment - they do not need to rely on a

provider and can self-manage their symptoms.

17

4.5. SLEEP

Sleep problems are among the most common complaints voiced by individuals with chronic

pain and the relationship between sleep and pain is complex. The presence of pain may make

falling and staying asleep more difficult, and disturbed. Insufficient sleep may increase next

day pain. Sleep conditions such as insomnia are linked with inflammatory processes, which

may also impact the bidirectional relationship between sleep and pain. It is not unusual for

poor sleep to be identified as the most frustrating issue for those with chronic pain due to its

negative physical and emotional effects. Therefore, it is important to discuss sleep and

evaluate the needs of the Veteran related to this topic.

While basic education around sleep hygiene may be conveyed and incorporated into

treatment, as it often would be in the primary care setting, it is important to determine if

triage is necessary. For example, if sleep disordered breathing may be present and has not

been assessed, a consult for a formal sleep study is likely in order, particularly as the

prevalence of sleep apnea is significant in the chronic pain population. If sleep issues are

severe enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for insomnia, a referral for local Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) treatment is indicated. Use of the Insomnia Severity

Index (ISI) may be helpful in differentiating whether a consult for more intensive sleep

intervention is appropriate. Completion of CBT-I prior to engaging in CBT-CP may increase

successful outcomes, but determining the preferred order should be evaluated and

determined individually with the patient’s preferences in mind.

4.6. WORKING WITH RESISTANCE

Those with chronic pain may be resistant to psychological interventions for pain for a variety of

reasons. One strategy that may be beneficial when encountering resistance is the use of

Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques which are highly patient-centered. MI can be used

to facilitate Veterans’ motivation to make positive health behavior changes. Because it

assumes that individuals are ambivalent about change, it seeks to help them uncover their

own internal motivation. Using open-ended questions so that they can share about pain

openly, affirming their strengths, reflecting empathically, and summarizing their perspective

and the next logical steps may help minimize resistance to treatment.

As always, it is important to remember that Veterans with chronic pain are hurting, often

emotionally as well as physically. Although they may exhibit defensive attitudes initially,

acknowledging the difficulty of their situation, including potential lack of compassion by

providers, can help establish a more open and trusting working alliance.

18

5. AN OVERVIEW OF BRIEF CBT-CP MODULE STRUCTURE

5.1. TREATMENT MODULES

Brief CBT-CP assumes that a standard initial PCMHI session following the 30-minute schedule

has been completed prior to starting Module 1. Brief CBT-CP consists of six modules. The brief

protocol requires that modules one and six are stable anchors to begin and end the protocol.

However, modules two through five can be presented in any order, depending on the

preference of the patient or best clinical judgment of the therapist. If there is no alternative

order preference identified, the modules should be delivered as listed in Table 3.

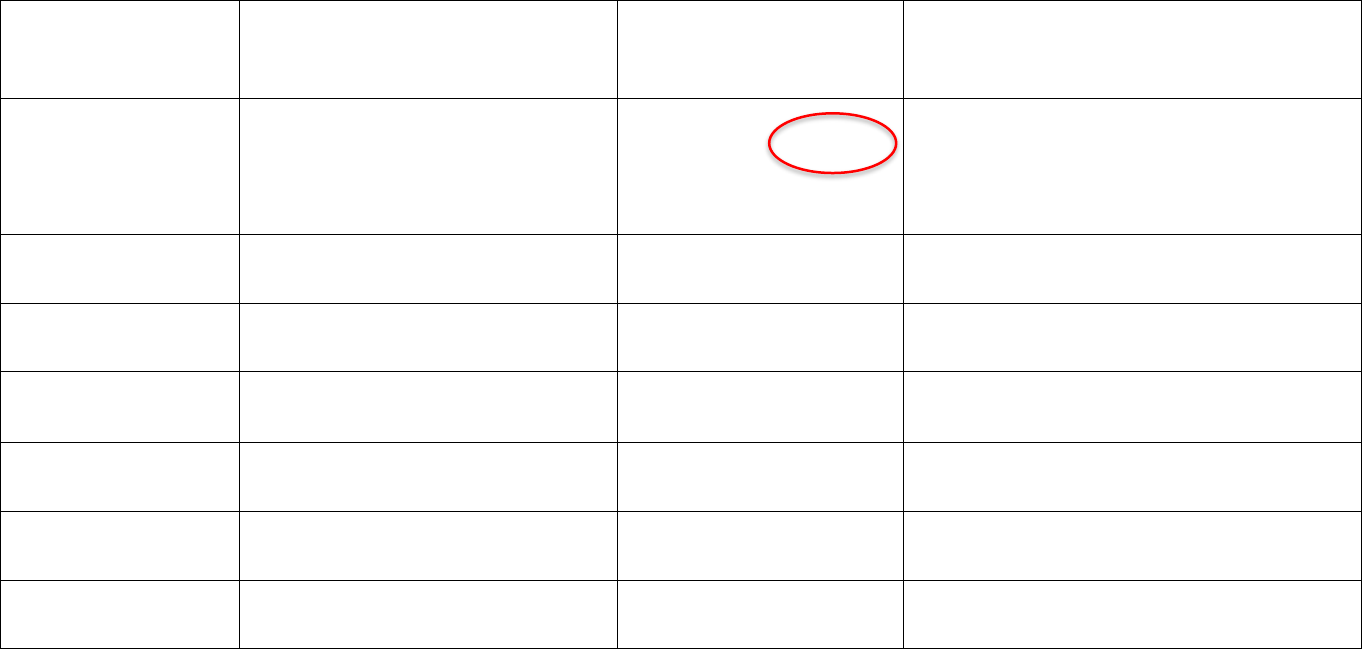

Table 3: BRIEF CBT-CP MODULES

Because CBT-CP is based on a model of intervention that emphasizes education and skill

development, educational handouts have been developed for use within the modules and to be

applied during homework modules. Patient handouts are an integral component of this

protocol and included in the appendices.

5.2. MODULE STRUCTURE

The structure of the Brief CBT-CP protocol is similar across modules and includes:

1. Introduce the module and confirm the agenda

2. Ask about mood, complete the PEG, and discuss findings

3. Review material from the previous module, including home practice

4. Introduce the new material and answer questions

5. Discuss new home practice opportunity

6. Module wrap-up

Brief CBT-CP Modules

Module

Content

1

Education and Goal Identification: Pain education and development of treatment

goals

2

Activities and Pacing: Importance of engagement in activities using a thoughtful

approach

3

Relaxation Training: Relaxation benefits and techniques

4

Cognitive Coping 1: Recognize unhelpful thoughts that negatively impact the pain

experience

5

Cognitive Coping 2: Modify thoughts that are unhelpful when managing pain

6

The Pain Action Plan: Plan for independent implementation of CBT-CP skills and

identify additional follow-up needs

19

5.2.1. Introduce the module and confirming the agenda (1-2 minutes)

Offering a brief introduction to the module helps orient the Veteran to the topics that will be

covered while also providing the opportunity to ask Veterans if they have anything to add to or

modify about the topic. This allows the Veteran to influence the agenda and emphasizes the

collaborative nature of Brief CBT-CP. Because the Brief CBT-CP protocol is highly structured and

works under time-limited modules, it is important to acknowledge that events may occur that

warrant discussion and that may result in adjusting content covered in a specific module.

5.2.2. Ask about mood, complete the PEG, and discuss findings (3-4 minutes)

In addition to briefly and informally asking about current mood, completion of patient-reported

outcome measures is an essential component of this protocol. The next chapter of this manual

provides detailed instruction in how to engage in measurement-based care using the PEG (Krebs

et al., 2009). Briefly, the PEG is a well-validated three-item measure that assesses pain intensity

(P), interference in enjoyment of life (E), and interference with general activity (G). Because the

PEG is so brief, it should be administered at each session as part of measurement-based care.

Additional measures can be added at the discretion of the provider.

5.2.3. Review material from the previous module, including home practice (3-5 minutes)

Providing a brief review of material covered in the prior module can create continuity between

modules and allow the Veteran to raise questions as needed. Taking a moment to discuss

potential questions reinforces the collaborative nature of the intervention and reduces the

chance of important messages being misconstrued. Review of home practice is an essential

component of Brief CBT-CP and serves to build competency in the use of adaptive pain coping

strategies. It should also enhance Veterans’ sense of self-efficacy to manage their chronic pain

condition by implementing acquired skills in the “real world”.

5.2.4. Introduce the new material and answer questions (12-15 minutes)

The majority of time in each module should be spent introducing and discussing the new

material for the module. Provide a clear rationale to the Veteran for each topic. To ensure

understanding, elicit reactions from the Veteran to material covered. Through discussion that

involves active listening, cuing, and reinforcing learning in a supportive and collaborative

environment, the Veteran is able to acquire adaptive pain management skills.

5.2.5. Discuss new home practice opportunity (2-3 minutes)

After a new topic has been reviewed in the module, it is important for the Veteran to be able to

practice building and implementing the skill independently. Discuss helpful areas for home

practice with the patient. It is important that the Veteran understands the potential benefits of

engaging in the coping technique and how it is related to better managing the effects of chronic

20

pain. Practice should be discussed collaboratively to ensure that it is manageable for the

Veteran.

5.2.6. Module wrap-up (1-2 minutes)

Each module should include a concise summary of key points that emphasizes the value of

outside practice. This wrap-up also signals the end of the module and allows for the patient to

ask any remaining questions about content addressed or next steps.

21

6. MEASUREMENT-BASED CARE (MBC) WITH THE PEG

6.1. WHY MBC?

Limiting excessive use of assessment tools in the context of everyday integrated care practice is

critical given time constraints; however, outcomes measurement is essential. Measurement

allows the clinician to better understand the Veteran’s experience of pain and the functional

domains that are impacted. Measurement also allows assessment of progress throughout

treatment and information generated can indicate when a change in practice is indicated. MBC

refers to the use of screening and ongoing symptom monitoring to guide treatment selection

and treatment modifications to improve outcomes for chronic health conditions (Morris, Toups,

& Trivedi, 2012). The aims of MBC are to rapidly and precisely diagnose conditions and to

evaluate patients’ response to intervention in order to improve treatment planning between

providers and patients (Harding, Rush, Arbuckle, Trivedi, & Pincus, 2011). Furthermore, it offers

patients a mechanism by which to track their progress and identify quantifiable goals for

treatment. The information from MBC can facilitate shared decision-making which includes

exploring options with the patient, weighing pros and cons of potential choices, and making

informed decisions in line with patient preference. MBC typically guides treatment for common

medical conditions in primary care, such as hypertension and diabetes, and has demonstrated

effectiveness in improving patient outcomes for these and other disorders (Klonoff et al., 2011;

Pickering et al., 2005). Similarly, routine monitoring of patient outcomes for mental health

conditions is associated with improvement in provider documentation of diagnosis, more rapid

treatment modifications, improved communication between patients and providers, and

improvement in patient mental health symptoms (Carlier et al., 2012). The VA strongly

endorses MBC for mental and behavioral health concerns and has been promoting the use of

MBC across mental health treatment settings since 2016 as part of a national initiative.

6.2 ADMINISTERING THE PEG

For Brief CBT-CP, the PEG (Krebs, et al., 2009) should be administered at every session, as

indicated in the module structure outline. The PEG includes three items. One item of the PEG

assesses pain intensity, and two items assess pain-related interference (i.e., enjoyment of life

and general activity). The PEG usually takes just a few minutes for patients to complete. The

measure can be completed on paper by the patient or administered verbally by the provider.

Scores should, however, be entered into the progress note for documentation. (Note that the

PEG is not included in this manual but is available as a supplemental .pdf document.) As a

helpful point of reference, research with primary care samples has estimated an average PEG

score of 6.1 (SD = 2.2) in this population, indicating a moderate level of overall pain and pain-

related interference (Krebs, et al. 2009).

6.3 CASE EXAMPLE: USING THE PEG IN EVERYDAY PRACTICE

A case example will be used to illustrate how to administer the PEG as part of Brief CBT-CP. Jeff

is a 26-year-old White Veteran who recently enrolled in VA primary care services after

separating from active service in the Marine Corps one year ago. Routine mental health

screening by his PACT provider and subsequent referral to PCMHI staff determined that chronic

22

low back pain stemming from his combat deployment is a significant contributor to his

irritability and depressed mood. Jeff’s back pain was rated as a 7 out of 10 on the Numeric

Rating Scale. He reports that pain negatively impacts his sleep, ability to sit through college

classes, and interactions with his young son. He is concerned that pain will impact his long-term

goal of operating his own business.

6.3.1. Establishing a baseline PEG and communicating findings

At Jeff’s first session of Brief CBT-CP with his PCMHI provider, his PEG scores were as follows:

Item

Score

Pain Intensity

7

Interference with life enjoyment

6

Interference with general activity

7

To determine Jeff’s baseline PEG score, simply compute an average score using the following

formula: (Item 1 + Item 2 + Item 3)/3 = average score. For convenience during clinical use, round

decimal points to the nearest whole number. This procedure is illustrated below:

To compute an average PEG score

Formula

(Item 1 + Item 2 + Item 3)/3

Example

(7 + 6 + 7)/3 = 6.6 = 7, if rounding

up

In this case, Jeff’s score is a 7 out of a possible 10, with 10 indicating the greatest severity. A

general guideline for interpreting 0-10 pain scales like the PEG is listed here:

PEG score

ranges

Qualitative description of level of

pain/interference

1-3

Mild

4-6

Moderate

7-10

Severe

In this case, Jeff was reporting severe overall pain and pain-related interference. Keep in mind

that scores of ≥4 indicate pain/interference that could benefit from intervention. Optionally,

consider reviewing the three PEG items separately, especially if they vary greatly (e.g., Pain

intensity = 8, Interference (life enjoyment) = 2, Interference (general activity) = 3). This

variability in items should be discussed to explore with the patient why there is a difference

between intensity and interference.

23

Part of establishing a useful baseline for Jeff is to utilize the score to enhance communication

with both the patient and the PCP. Scores at baseline (or any point in time) can convey current

status:

“Jeff, your score of seven on the PEG is in the severe range. This

score, along with the information you provided during our

discussion, indicates that you could benefit from starting Brief CBT-

CP…”

A discussion that incorporates patient-reported outcomes can also help fuel motivation to

engage in treatment:

“Over the next several weeks, we will use the PEG again to

monitor any changes in your pain ratings. These scores will help us

plan our next steps together. We will aim to have your score go

down over time as you apply new skills as part of Brief CBT-CP…”

This discussion can set a norm of using measurement as part of shared decision-making

between the patient and provider, while maintaining the focus of care on pain management and

restoring functioning.

In addition to discussing scores with the patient, conveying PEG scores to the primary care

provider (PCP) is also important. This type of communication not only improves flow of

information between providers, but ideally prompts the PCP to reinforce your plan for using

Brief CBT-CP when he or she interacts with the patient (e.g., motivating the patient to re-engage

in balanced, structured physical activity to avoid de-conditioning). The PCP may also consider

adjusting his/her own treatment plan (e.g., medication changes, adding adjunctive services such

as referral to physical therapy) depending on the information you convey.

6.3.2. Assessing for change over time

As mentioned previously, a primary reason for engaging in measurement at each session is to

be able to assess for meaningful changes in scores over the course of treatment. Stability of or

changes in scores are important for assessing response to treatment and can suggest times

when modification to a treatment plan is necessary. Assessing for change between two time

points is simple and can be computed quickly as follows:

To compute change in PEG scores

Formula

(Average PEG score at time 1 – Average PEG score at time 2)

Average PEG score at time 1

Multiplying the resulting figure by 100 will provide an estimate of percentage change in scores.

As a general rule, a 30% change (improvement) in pain-related scores, including the PEG, is

considered clinically significant in response to a course of treatment. Although a 30% decrease

24

is ideal, other meaningful patterns are also important to consider given the relatively short time

frame inherent to integrated care settings.

In Brief CBT-CP, less dramatic but potentially meaningful changes have been identified in our

pilot work (Beehler et al., 2019). Previously, as part of a clinical demonstration project, we

found, on average, a statistically significant 1-point decrease in PEG scores between session 1

and session 3. Although additional research is needed to replicate these findings under the

conditions of a rigorous randomized controlled trial, initial support for Brief CBT-CP is

encouraging.

Assessing for change can be done at any time frame, including when comparing the first and

third required modules. For example, note Jeff’s PEG scores below:

Module

PEG score

Module 1 (Education and Goal Setting)

7

Module 2 (Activities & Pacing):

7

Module 3 (Relaxation)

6

(7-6)/7 = 0.14 * 100 = 14% improvement

During this relatively short time frame common in PCMHI, these measures suggest no dramatic

changes, but a decreasing trend. This trend is encouraging in that there are no large

fluctuations in PEG scores that would suggest worsening of symptoms. If Jeff were to continue

on this course with additional Brief CBT-CP modules, the following pattern may emerge:

Module

PEG

score

Module 1 (Education and Goal Setting)

7

Module 2 (Activities & Pacing):

7

Module 3 (Relaxation)

6

Module 4 (Cognitive 1)

7

Module 5 (Cognitive 2)

6

Module 6 (Pain Action Plan)

5

(7-5)/7 = 0.29 * 100 = 29% improvement

In this case, additional improvement in PEG scores was realized by continuing with the

remaining Brief CBT-CP modules. Having reached a 29% decrease in PEG scores suggests a clear,

clinically significant improvement in outcome.

Of course, this is only one example of what you might find with the PEG. Below we discuss how

to address three different situations (i.e., beneficial change, no change, or worsening of

symptoms) over time. It is important to then discuss these changes with both the patient and

PCP in determining next steps.

25

6.4 USING THE PEG TO IMPROVE SHARED DECISION-MAKING

Discussing PEG scores, including changes in scores over time, can facilitate shared decision-

making in which the provider (or providers) work collaboratively with the patient to determine

the best course of treatment. Although a full description of the nature of shared decision-

making is beyond the scope of this chapter, there are a few general principles that should be

considered. According to Elwyn and colleagues (2012; 2017), shared decision-making is a

process that includes three general areas: 1) working as a team to identify choices in light of

patient goals; 2) discussing alternatives, such as the advantages and disadvantages of each

option; and 3) making an informed decision that aligns with patient preference. PEG scores can

help initiate the process of decision-making when the data indicate that change (or lack of

change) in symptoms is evident during or at the conclusion of treatment. Outlined below are

some general guidelines for using PEG scores to generate options for treatment decisions.

When PEG scores show sufficiently meaningful improvement over time, first confirm if the

patient concurs with this assessment. If the patient’s experience of pain or disability does not

appear to be reflected by the PEG scores, additional assessment may be necessary to

determine why there is a discrepancy. However, if the patient feels that sufficient improvement

has been achieved and treatment goals have been met, no additional treatment may be

necessary. Explore with the patient what an end to Brief CBT-CP means in terms of follow-up

options.

“One of the options for us to consider includes wrapping up your

treatment at this time. Based on the improvement we’ve seen in

your PEG scores and the fact that you’re meeting your main goal

of getting through your classes at college, you’re likely in a good

position to begin applying these skills on your own. If we decide to

end for now, my door remains open should you need to reconnect

with me, or another provider, regarding your pain or any other

concern that impacts your wellness...”

For many patients, knowing that they can return to PCMHI as-needed is sufficient. Other

patients may prefer to address additional concerns with you or another provider outside of

PCMHI now that their pain-related interference is under control.

In situations where PEG scores suggest that no meaningful change is evident, again confirm if

this finding is consistent with the patient’s experience. Additional discussion may be necessary

if the patient’s verbal report of response to treatment differs from PEG scores. If the patient

agrees that insufficient progress is being made, first discuss potential treatment barriers and

other factors that could have impacted patient adherence (e.g., not engaging in home practice,

change in patient goals for treatment). If the patient has had a difficult time with treatment

receipt (i.e., learning CBT skills) or enactment (i.e., using CBT skills outside of session), consider

if revisiting prior modules would be valuable for enhancing skills development.

26

“Let’s talk a little bit amore about what might be getting in the

way of moving forward. It sounds like it’s been a challenge to find

the time to apply the strategies we’ve discussed in session. One

option for us to consider is spend a moment to find times during

the day that might be best to apply one or more skills…”

Also consider if optional modules of Brief CBT-CP are appropriate. If additional discussion

suggests that Brief CBT-CP was not effective despite adequate patient adherence and interest,

consider stepping up the level of care for the patient to include referral to a pain specialty

provider or behavioral medicine expert.

When PEG scores suggest the patient is getting significantly worse over time, be certain to

confirm if this trajectory is consistent with the patient’s experience. Discrepancies should be

explored with the patient to determine why declines in PEG scores may not be reflective of the

patient‘s experience. Depending on the extent of the decline, first consider issues related to

patient safety and well-being. Additional suicide risk assessment should be conducted with

appropriate follow-up action taken as needed. Further assessment should be focused on

determining the cause of increased pain and disability, which may be transient (e.g., temporary

but repeated pain flare-ups due to overexertion) or stable (e.g., significant re-injury, new

medical or mental health diagnoses, negative life event/psychosocial factors).

“As you know, your PEG scores show that your pain and its

negative impact has become more significant since we first started

working together. I’d like to take a minute and talk with you a bit

more about what might be contributing to this situation from your

perspective. I’d also like to ask some questions about your safety

and well-being given how down you’ve been feeling. We might

want to consider adding some additional help alongside Brief CBT-

CP. Alternatively, we might consider whether or not services with

another provider who can offer more intensive support might be a

good option…”

Such factors likely suggest that stepping up to a higher level of care (e.g., referral to the

specialty pain clinic) or adding additional services (e.g., psychiatry) to the current course of

treatment may be indicated.

27

7. THE HOOK: OFFERING PATIENTS BRIEF CBT-CP

7.1. INTRODUCTION

The goal of offering an orientation to Brief CBT-CP is to provide the Veteran with a roadmap for

what can be expected during treatment and to establish clear expectations for both the

therapist and the Veteran. Brief CBT-CP can be introduced to patients any time chronic pain

management surfaces as a key concern for the patient’s wellbeing, provided that safety-related

concerns (e.g., lethality, significant neurocognitive disorder, psychosis) are absent or otherwise

addressed. Regardless of when Brief CBT-CP is introduced, it is helpful to provide a persuasive

but honest portrayal of the nature of the intervention and its potential to benefit the patient

The Therapist Guide that follows was designed to illustrate how to engage in a conversation

with the patient that can be addressed in 10 minutes or less as part of a brief, 30-minute

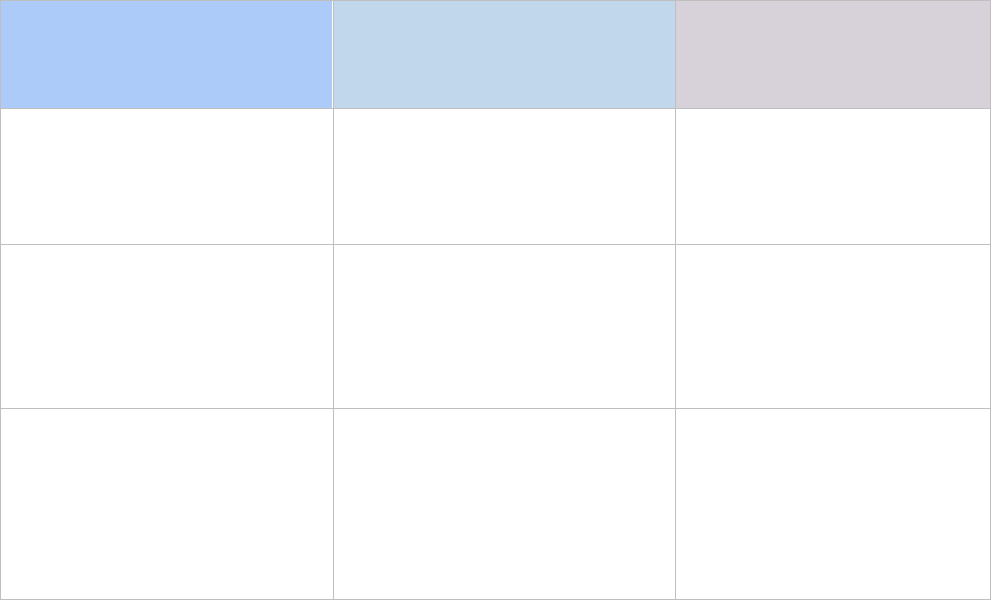

standard initial appointment or intake (Figure 4). We strongly recommend using this guide to

enhance motivation for treatment engagement. Of course, conversations about Brief CBT-CP

may need to be modified based on the level of patient receptivity.

The 5-A’s module

structure for initial

PCMHI appointments

(Figure 4) provides an

excellent approach for

how to introduce and

educate patients about

Brief CBT-CP. In short,

after conducting a

routine assessment of

patient functioning and

summarizing your

understanding of the

patient’s concerns (that

include the need for

chronic pain

management), the

remaining time can be

used to introduce the

patient to Brief CBT-CP,

answer questions, and

address potential barriers to full participation. If your treatment setting allows for

appointments of longer than 30 minutes, then the remaining time can be devoted to beginning

the first module of Brief CBT-CP.

Figure 4. Phases of a 30-Minute Appointment

28

If the patient ultimately decides not to engage in Brief CBT-CP, it is valuable to consider other

options that may be available. Some patients simply need more time to consider their

treatment options. For this kind of situation, we include a two-page patient handout entitled

Before You Go: Additional Information about Chronic Pain Treatment Options. This handout

includes the following: a quick summary of Brief CBT-CP; a short relaxation exercise; links to

freely available mobile apps that can address health and wellness topics; space for the provider

to summarize next steps regarding chronic pain management, such as referrals to other clinical

services; and a space for the provider’s contact information.

29

Offering Patients Brief CBT-CP:

Therapist Guide

Although adopting an empathic stance is not unique to CBT, it is nonetheless important when

working with patients experiencing chronic pain. Often, patients will be referred to you for

treatment when their pain is most distressing or when biomedical treatments have been

insufficient. Empathy is especially useful for building rapport and trust.

What is Brief CBT-CP?

• Brief CBT-CP targets thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in order to improve pain-related

functioning.

• Brief CBT-CP promotes the adoption of self-managed tools by patients so that they can

take an active role in effectively addressing chronic pain and its negative effects.

• Use the Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain handout to illustrate the

CBT-CP model.

Scripting includes:

1. “Living with chronic pain can be very challenging. It can negatively impact how we live

our lives, including our ability to participate in activities and important relationships with

others. Individuals with chronic pain often struggle to find ways to manage their pain

and feel that they lack the know-how to move forward with their lives.”

2. “Brief cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, for chronic pain is designed to help us

respond to chronic pain in a way that will help us live a more fulfilling life. Patients learn

new pain management skills that can keep us connected to the people and daily routines

that we value.”

3. “An important piece of Brief CBT for chronic pain is the teamwork between the patient

and therapist. My goal is to work closely with you in a way that you find supportive and

empowering.”

4. “This intervention is designed to be brief so it’s not a long-term commitment. Of course,

if we decide that additional support will be beneficial, then I will help connect you to

additional services.”

30

What does Brief CBT-CP Include?

• The treatment structure of Brief CBT-CP includes six appointments that last about 30

minutes each.

• Topics covered reflect the key components of full-length CBT for pain:

• Pain education and goal setting

• Activities and pacing

• Relaxation training

• Cognitive coping (covered in two sessions)

• The Pain Action Plan

• Treatment is structured, but decision making is collaborative between patient and

therapist.

Scripting includes:

1. “Brief CBT for chronic pain includes six modules of 30 minutes each. We will cover a new

pain management skill each week based on your preference. This means that we will

work closely and stay focused to make the most of our time together.”

2. “Our first module will provide some important background information about chronic

pain itself and setting new goals for moving forward. Then we will decide together about

the order of our remaining topics. We will choose from the following: activity planning

and pacing, which will help us avoid a common pitfall of overexerting ourselves and

causing a pain flare up; relaxation training which will cover several ways to reduce

tension in our bodies and feeling distressed; and cognitive coping, which helps us

address unhelpful thought patterns -we learn to feel better by changing the way we

think about pain and ourselves. Our final module will focus on reviewing the skills we

learned and developing a plan for how best to use those skills.”

3. “At the end of each module, we will talk about ways you can begin to practice each skill.

Practice is very important as we want these new approaches to become good habits. We

will find a way to make practice doable even during a busy day.”

31

What are the Advantages of Brief CBT-CP?

• There are number of advantages to applying Brief CBT-CP, both practical and research-

supported. Based on what you know about the patient, it’s helpful to emphasize the

match between patient needs/goals and what Brief CBT-CP can offer.

Scripting includes:

1. “CBT for pain has been studied by researchers for many years. Overall, these studies

show that patients experience less distress and disability after using what they learn in

CBT. Some patients even report that their pain intensity has decreased.”

2. “CBT for pain is safe for almost anyone. There are no known negative side effects and

the focus is educational and skill-building.”

3. “The brief version of CBT for pain that we will use is less than three hours of treatment

time and is spread out over several weeks. This minimizes the amount of travel and time

you spend in treatment.”

What are the Limitations of Brief CBT-CP?

• Discussing the limitations of Brief CBT-CP can be helpful in setting realistic expectations

about what treatment can and cannot accomplish.

Scripting includes:

1. “Brief CBT-CP can be very helpful, and it requires that we work together as a team to

help manage your pain more effectively. Part of your treatment will include assessing

your pain and distress using one or more brief, easy to complete surveys. These will help

us determine what is going right in treatment and other areas that may need more

focus.”

2. “Brief CBT for pain is primarily about helping with pain management. This does not

mean eliminating your pain but responding to your pain in a more helpful way so that it

feels less overwhelming.”

3. “Sometimes during treatment we will need to talk about some difficult experiences you

have had in relation to pain so that you are able to respond in beneficial ways in the

future. Over the course of treatment, the goal will be to use the skills we learn to address

distressing pain-related experiences.”

32

Before You Go: Additional Information about

Chronic Pain Treatment Options

Today we discussed some of the challenges of living with chronic pain. We also discussed some

options available to help manage chronic pain. One option that may be a good fit for you is

Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain, or Brief CBT-CP. Some key information

about Brief CBT-CP is summarized here, in case you would like to begin this treatment at a

future time:

1. Brief CBT-CP can help decrease distress and disability from pain and is safe for almost

anyone.

2. Brief CBT-CP includes six, one-to-one meetings of about 30 minutes each. Treatment can

be spread out over 6 to 12 weeks.

3. A new pain management skill is covered each week based on the order you prefer. Key

topics and skills include:

• Activity pacing, which helps with avoiding a common pitfall of overexertion that

causes a pain flare-up.

• Relaxation training, which will help to reduce tension in your body and manage

distress.

• Cognitive coping, which will help with managing unhelpful thought patterns.