TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 18 January 2023

DOI 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

OPEN ACCESS

EDITED BY

Conrad Ziller,

University of Duisburg-Essen,

Germany

REVIEWED BY

Norman Sempijja,

Mohammed VI Polytechnic University,

Morocco

Elizabeth J. Zechmeister,

Vanderbilt University, United States

Paul Vierus,

University of Duisburg-Essen,

Germany

*CORRESPONDENCE

Felix Jäger

SPECIALTY SECTION

This article was submitted to

Political Participation,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Political Science

RECEIVED 29 July 2022

ACCEPTED 28 December 2022

PUBLISHED 18 January 2023

CITATION

Jäger F (2023) Security vs. civil

liberties: How citizens cope with

threat, restriction, and ideology.

Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1006711.

doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

COPYRIGHT

© 2023 Jäger. This is an open-access

article distributed under the terms of

the

Creative Commons Attribution

License (CC BY)

. The use, distribution

or reproduction in other forums is

permitted, provided the original

author(s) and the copyright owner(s)

are credited and that the original

publication in this journal is cited, in

accordance with accepted academic

practice. No use, distribution or

reproduction is permitted which does

not comply with these terms.

Security vs. civil liberties: How

citizens cope with threat,

restriction, and ideology

Felix Jäger

*

Mannheim Centre for European Social Research, Graduate School of Social Sciences, University of

Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

How do citizens balance their preferences for civil liberties and security

in the context of a competitive party system? Using the case of terrorism

and counter-terrorism, I argue that the willingness to support restrictions of

civil liberties does not only depend on external shocks and being targeted

by a counter-policy. Instead, it also depends on their ideological match

with policymakers and terrorist actors. Using an original survey experiment

conducted in Germany in 2022, I study how the four factors feeling threatened

by a terrorist attack, being targeted by a surveillance measure, the ideology

behind an attack, and the partisanship of counteracting politicians influence

the attitudes of citizens and whether these factors are mu tually dependent.

While earlier research has focused on one kind of terrorism (mostly Islamic),

this paper examines various forms of terrorism (religious, right-wing, and

climate-radical) and how they aect peoples’ attitudes toward civil liberties

and surveillance. The results show that terrorist ideology plays a minor

role, but that it matters whether citizens sympathize with the party that

proposes a policy. The study extends our understanding of the political

consequences of polarization, threat perceptions of terrorism, and public

support for surveillance policies.

KEYWORDS

security, civil liberties, terrorism, ideology, polarization, policy preferences,

surveillance, survey experiment

1. Introduction

In times of crisis, civil liberties often have to be restricted for a higher good. Since

civil liberties are one of the great accomplishments of democracy, this is not an easy

decision for governments to make or for citizens to support. When citizens are asked

how important democratic values such as civil liberties are to them, they rate them very

high (Sullivan and Hendriks, 2009). However, these rights are not set in stone and cannot

be considered in a vacuum (

Peffley et al., 2001; Jenkins-Smith and Herron, 2009; Graham

and Svolik, 2020

), as they entail trade-offs with other, highly valuable rights. One of the

strongest conflicts is that between security and civil liberties. This applies to different

external shocks, such as a pandemic, war, or terrorism (

MacKuen and Brown, 1987;

Rohde and Rohde, 2011).

Frontiers in Political Science 01 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

Policymakers react to these external shocks by implementing

policies to protect the population from such dangers. These

policies are a materialization of the norm conflict between civil

liberties and security. However, these policies are often heavily

debated both within parliaments and among the general public.

In these discussions, not only the content of the policies matters,

but also the ideology of the parties who are proposing them.

In this paper I argue that the willingness to support

restrictions of civil liberties depends not only on external

shocks, but also depends on whether citizens are inclined or

averse to policymakers. The acceptance of opinions from other

people or actors who have an opposing ideology or partisanship

is limited within a competitive party system or a polarized

society. Polarization along part y lines is no new phenomenon,

but the level of polarization has increased over the last two

decades (

Heltzel and Laurin, 2020; Druckman et al., 2021). In

Germany, where this s tudy is conducted, affective polarization

has been slowly increasing since 2008 (

Harteveld and Wagner,

2022

). A major driver of polarization has been the far-right

party Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany,

short AfD) since its foundation in 2013 (

Siri, 2018). Affective

polarization in Germany is mainly between partisans of the AfD

and other partisans. This disliking is asymmetrical, with a higher

aversion of supporters from other parties toward the AfD. AfD

supporters, in contrast, are less negative toward other partisans

(

Jungkunz, 2021).

Consequences of polarization along partisanship can be

seen, for example, in studies about democratic backsliding

(

Somer and McCoy, 2018; Svolik, 2019). The results concerning

citizens’ propensity to favor partisanship over democratic norms

are mixed.

Carey et al. (2022) find that citizens are defending

democratic norms even when this requires a punishment of

a candidate from the own camp. Other studies find opposing

results, according to which partis anship is valued more highly

than democratic norms (

Graham and Svolik, 2020; Kawecki,

2022

; Saikkonen and Christensen, 2022). The polarization along

partisanship embeds the norm conflict of civil liberties and

security in a societal context. This constitutes the first research

gap this paper is addressing. The paper is guided by the question:

How do citizens balance their preferences for civil liberties and

security in the context of a competitive party system?

A case in which the necessity occurs to find a balance

between civil liberties and security is terrorism and counter-

terrorism as a reaction to it. Looking at specific cases is

necessary, as they add additional elements and variables for

citizens to consider. In the case of terrorism, the major

explaining factor is perceived threat. In general, the higher the

perceived threat, the higher the support for security even at

the expense of civil liberties (

Huddy et al., 2005, 2007; Haider-

Markel et al., 2006

). A second element is the ideology or

motivation of terrorists (

Caton and Mullinix, 2022). Not every

motivation generates the fear or perceived threat of becoming

a target in every citizen equally. A white person might feel less

threatened by right-wing terrorism than a non-white person,

so as an ordinary citizen might feel less threatened by left-

wing terrorism than a person in a leading position. Turning this

relationship around, the motivation of terrorists could even lead

citizens to support them. However, most studies focus on a single

type of terrorism, which has been mainly Islamist terrorism

in the last two decades. Despite right-wing terrorism being

responsible for many attacks in western democracies, especially

in Germany and the U.S.

1

, only few articles have so far looked at

different kinds of terrorism (

Pronin et al., 2006; Wynter, 2017).

This study addresses this second research gap by comparing

how different terrorist motivations (Islamist, right-wing and

climate-radical) influence citizens’ preferences for security.

To answer the research question, the four stated elements

(feeling threatened by a terrorist attack, being targeted by a

surveillance measure, the ideology behind an attack, and the

partisanship of counteracting politicians) are considered. Using

a survey experiment allows me to vary t hese elements through

specific treatments and to compare citizens’ policy preferences

under t hese conditions. Such a design complements natural

experiments (

Bozzoli and Müller, 2011; Giani et al., 2021),

which are limited to actual attacks and cannot exclude external

circumstances. The perception of actual terrorist attacks can

be influenced by other simultaneous events, such as election

campaigns (Muñoz et al., 2020). These limitations can be

overcome by the survey experiment employed here. The design

has the practical advantage that, for example, the influence

of different terrorist motivations on citizens’ attitudes can be

examined, which would not be possible in the real world.

The survey experiment was pre-registered and conducted in

Germany in 2022.

The results show that, first, citizens value their privacy and

prefer targeted measures. Second, partisanship matters even in

a crisis. Citizens are willing to accept cuts in civil liberties when

they are proposed by their preferred party. When these cuts are

proposed by a disliked party, the support decreases strongly.

This logic does not apply to terrorist motivation. Citizens do not

change their support for civil liberties when terrorist attacks are

motivated by an extreme form of an ideology t he citizens adhere

to. This result holds for citizens with a high level of extremism

and citizens with a high propensity to violence.

The study expands previous findings by looking at the

conflict of civil liberties and security through the lens of

partisanship and ideology. In times of crisis, when difficult

decisions must be made, parties should work together to gain

support from the population. The good news for societies is that

the political affiliation of citizens does not extend to support for

ideologically close terrorist attacks.

Increasing our knowledge about citizens’ preferences for

security and civil liberties is crucial for western democracies.

1 https://www.csis.org/analysis/escalating-terrorism-problem-

united-states

Frontiers in Political Science 02 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

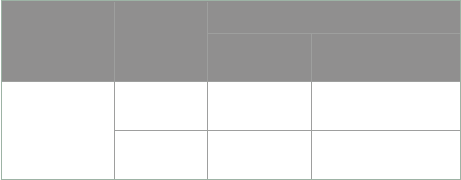

TABLE 1 Four combinations of ordinary citizens who experience an

external shock and are targeted by a counter-policy.

External shock

Personal

threat

No personal

threat

Counter-policy Not being

targeted

A B

Being

targeted

C D

While security has been treated as a higher good by politicians

in recent years (

Hegemann and Kahl, 2018), the attitudes of

citizens should not be ignored. Undermining civil liberties

extensively can lead to undesirable developments. A restriction

of fundamental freedom can be the beginning of democratic

backsliding. While this is not a fast, overnight process, it can

open paths that turn away from democracy or facilitate ongoing

processes. A better understanding of the circumstances or

reasons why citizens support restrictions of civil liberties opens

up the possibility of counteracting such movements or seeking

other solutions to strengthen democracy where it is needed.

2. Literature and arguments

2.1. Threat and surveillance—the

trade-o between security and civil

liberties

One aspect of citizens’ decision to support a policy is the

calculation of whether the policy improves their situation or

not. It comes down to the personal situation of citizens. In

the context of civil liberties and security, citizens have to ask

themselves whether t he policy is increasing security more than

civil liberties are restricted. This has to be balanced against the

incoming threat, which should be prevented by the policy. The

relationship c an be applied to any deb ate about civil liberties vs.

security, for example health protection issues during a pandemic

or the prevention of terrorism.

Table 1 shows the stated matrix between an external shock

and the counter-policy. Using the specific case of terrorist threat

and counter-terrorism policies, I explain in the following how

these two factors are expected to influence citizens’ preference

for security and civil liberties.

Threat is arguably the strongest predictor and best-examined

factor in studies about citizens’ preferences in the context of

terrorism. A large body of literature on support for security

policies exists that examines the predicting effect of perceived

threat exclusively or among other factors (

Huddy et al., 2002,

2005; Davis and Silver, 2004; Hetherington and Suhay, 2011;

Asbrock and Fritsche, 2013; Cohen-Louck, 2019; Breznau,

2021

). Unfortunately, the nomenclature is not consistent across

studies (

Feldman, 2013, p. 55). Threat, perceived threat, or

the perception of risk describe the same issue from a slightly

different angle, but these terms are often used interchangeably.

In this study, I define perceived threat as an outcome of

an external shock, event, or situation the individual citizen

is confronted with and which is interpreted or perceived as

negative or dangerous. This definition focuses on perceived

personal threat and not on societal, sociotropic , or national

threat.

Perceived personal threat directly concerns individuals

confronted with the external shock. In such a situation,

individuals “will probably be made particularly aware of their

own vulnerability” (

Trüdinger, 2019, p. 37). This awareness

of becoming a victim leads people to think more about their

in-group than about themselves as individuals (

Asbrock and

Fritsche, 2013

). This awareness and the wish for protection for

oneself and the own in-group translates to policy preferences

for security. In the case of terrorism, it seems very likely

that personally threatened citizens will favor security over civil

liberties (

Hetherington and Suhay, 2011).

These external shocks (or, more specific, terrorist attacks),

which are a personal threat for individuals, have to be separated

from a general or omnipresent fear of terrorist attacks. A general

fear of external shocks is an individual predisposition, which

describes citizens’ general sensitivity to threat or baseline threat

(

Marcus et al., 1995, p. 107). An individual who has a higher

baseline threat is expected to have a higher preference for

security in general. For example, more fearful individuals are

more in favor of restrictive migration policies (

Helbling et al.,

2022

).

The individual shocks provide a “contemporary

information” (

Marcus et al., 1995, p. 107), which provokes

the perception of threat. As

Trüdinger (2019, p. 35) put it,

“[T]he consequences of perceived thre at can be considerable as

it mig ht result in a complete change in political reasoning”. In

danger of an external shock, “people try to restore perceptions

of global control over their environment, which are at

stake in times of threat” (

Fritsche et al., 2011, p. 102). This

regain of control is expressed as an increased preference for

security me asures.

H1a: Citizens’ suppor t for counter-terrorism measures

increases when they are personally threatened by

terrorist attacks.

The rows in

Table 1 show the counter-policy. The rationale

behind the influence of this dimension on citizens’ policy

support is similar to the influence of the external shock. As

in the external shock dimension, citizen can also be target of

the counter-policy or not. The possibility of this differentiation

depends on the individual measure because not all counter-

policies to external shocks concern the ordinary citizen.

The term counter-terrorism covers a lot of different policies,

ranging from military actions abroad (

Gadarian, 2010) to

Frontiers in Political Science 03 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

immigration regulations (Helbling and Meierrieks, 2020) and

domestic measures such as surveillance (

van Leeuwen, 2003;

Ziller and Helbling, 2021). In this paper, I operationalize

counter-terrorism as a surveillance policy. Surveillance can

target suspicious individuals or groups, which would not

concern ordinary citizens. Such a measure is rather easy for

citizens to support, since it does not impose any restrictions on

them. This is similar to other measures, for example a policy

aiming to disrupt financial flows of terror ists. These measures do

not affect ordinary citizens and thus come at no personal cost.

In contrast, dragnet surveillance affects every citizen in

the state, so citizens are indirectly targeted. In this case,

the measure entails the conflict between security and civil

liberties (

Kossowska et al., 2011). Security should be increased

by preventing terrorist acts. Civil liberties are restricted, as

surveillance can severely curtail privacy rights (

Ziller and

Helbling, 2021

). Surveillance falls in the category of privacy

laws and directly affects citizens in contrast to measures that

concern procedural or immigration laws (

Epifanio, 2011). Since

citizens are expected to value their privacy, dragnet measures

should receive less support than measures targeting suspect

individuals.

H1b: Citizens’ support for counter-terrorism

measures decreases when they are targeted by the

counter-terrorism policy.

The expectations stated in H1a and H1b are rather

straightforward: respondents to whom case A in

Table 1 applies

should be most supportive of a security measure, respondents

in case D the least suppor tive. Case C is the most interesting

case, as citizens are confronted with the dilemma of threat

and restriction of civil liberties. Depending on the measures

implemented by the government, the individual liberties are

curtailed (

Davis and Silver, 2004). The theoretical argument

in the literature on perceived threat highlights the strength of

the influence that perceived threat has on individuals’ attitudes.

Following this line of research, I argue that respondents strongly

support security measures even at the cost of their personal

liberties.

H1c: The feeling of being threatened by a terrorist attack

outweighs the feeling of being targeted by a policy and drives

the support for a counter-terrorism measure.

2.2. How ideology and partisanship

influence citizens’ willingness to favor

security over civil liberties

While the need to balance these two factors is very clear, t he

support for policies has to be examined in the context of a society

in which citizens have different ideological stances. The ne cessity

to do so becomes clear by going b ack to

Table 1. Bot h sides of the

table can be extended by an ideological dimension. Threat when

caused by some human actor has an ideological background.

Equally, the counter-policy must be suggested by a party or

implemented by a government, which also has an ideological

background. Since ideology is a guideline for individuals to

evaluate specific situations or policies, it also influences citizens

preferences. Ideology can be described as an “interrelated set

of attitudes, values, and beliefs wit h cognitive, affective, and

motivational properties” (

Jost et al., 2009, p. 315). Ideology

groups peoples’ attitudes and experiences so they can be used

as guidelines for future decisions.

Ideology as a factor in policy preferences has been examined

for a long time (Stimson, 1975). First, the specific content

of policies can be more appealing to citizens with a certain

ideology. Second, a policy is proposed by a party, which can

be used as additional guidance by citizens. Research has shown

that partisans are more likely to support policies when they

are proposed by in-group partisan elites rather than out-group

partisan elites (

Bolsen et al., 2014; Pink et al., 2021). Intolerance

exists on both sides of t he ideological spectrum toward the

other side: “conservatism would predict intolerance of left-

wing targets, liberalism would predict intolerance of right-

wing targets. Moreover [...] t hose on both the left and right

would be biased against ideologically opposing targets relative to

ideologically supporting targets” (

Crawford and Pilanski, 2014,

p. 842). While partisanship is not exactly the same as ideology,

the two concepts are highly related and correlated (

Wright

et al., 1985

; Barber and Pope, 2019; Lupton et al., 2020). In

this paper, I will mainly refer to partisanship as an outcome of

ideology. Partisanship is heavily used by citizens to identify with

politicians and take their position on issues under discussion.

Policies concerning the nexus between security and civil

liberties are no exception when it comes to the impact of

citizens’ partisanship on their policy preferences. As these

policies are suggested by politicians, the match or mismatch

between citizens’ ideology and that of these politicians should be

a strong indicator of whether a citizen supports t he policy. On

average, when the policy-proposing party is known by citizens

the support for the policy decreases because there are always

citizens who dislike a given party. In contrast, when the citizens

are inclined to the policy-proposing party, the support for the

policy should increase.

H2a: Citizens’ suppor t for counter-terrorism measures

decreases when the policy-proposing party is disliked by them.

H2b: Citizens’ support for counter-terrorism measures

increases when they are inclined to the policy-proposing party.

Ideology is also inherent in the specific context I am

investigating—terrorism. Conveying an ideologically motivated

message is essential in many definitions of terrorism (

Ruby,

2002

; Schmid, 2011). While civil liberties have been widely

studied in the context of terrorism, terrorism has mostly

been considered as a general concept with no further

Frontiers in Political Science 04 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

specification. This introduces another factor in citizens’ support

for counter-terrorism policies, which is the possible alignment

of perpetrators’ motivation or ideology and the one of citizens

(

Caton and Mullinix, 2022). Ideology can serve as a guiding

factor, which allows citizens to allocate themselves to groups,

such as parties or interest groups. In an extreme case, citizens

could sympathize with potential terrorists and their motivations.

While most citizens are likely to condemn any type of

terrorism, supporters of extreme ideologies might not oppose

such acts as strongly as ot hers. In a polarized society, citizens can

be expected to support extreme versions of their own ideology.

While most people will still not directly support terrorism, they

might not support security measures that aim to prevent such

incidents as strongly as other citizens.

H2c: Citizens’ suppor t for counter-terrorism measures

decreases when they share the ideology of the terrorist actors.

The previous hypothesis concerned the influence of

partisanship and ideology on citizens’ attitudes toward counter-

terrorism measures. As outlined, the effect is expected to be

very strong and persistent. However, partisan loyalty will not be

unlimited. When citizens deviate from the lines of parties they

support is still debated. Related to this is the question of what

factors influence the formation of citizens’ policy preferences.

Can the dominant factor of party cues (

Cohen, 2003) be

overruled by other factors?

A likely case of deviation from the party lines is when

politicians behave undemocratically or propose policies that

contradict democratic norms. Studies conducted in t he U.S.,

however, have yielded contradictory findings.

Graham and

Svolik

(2020) find that in the U.S., partisanship is more

important to citizens than democratic norms: they would

rather stick to their ideologically close candidate who violates

democratic norms than vote for the opposition. Saikkonen

and Christensen

(2022) report similar findings for Finland.

Carey et al. (2022) come to the opposing conclusion that

citizens are willing to punish undemocratic behavior regardless

of partisanship. While the violation of democratic norms is an

extreme case, it can generally be expected that citizens rather

take t he position of their preferred party.

A most likely c ase of deviation from the party lines

occurs when the fundamentals of human life are in danger

or threatened. Security and the need for physical integrity

is at the very bottom of human necessities (

Maslow,

1954

). Since perceived threat has been identified as a

strong predictor for citizens need for security, perceived

threat should outweigh effects of partisanship. I expect

citizens to support a security policy even if they dislike t he

policy-proposing party.

H3a: Citizens’ suppor t for counter-terrorism measures

increases when they are personally threatened by an attack,

even when they dislike the policy-proposing party.

Another trade-off or contradiction can appear between party

preference and the suggested counter-terrorism policy. Citizens

could sympat hize with a party, but dislike t heir suggested policy.

More specifically, citizens could disagree with the policy-target,

especially if the target is their own in-group. In this case, citizens

are more likely to oppose a policy because they are constrained

by the policy. When polices are targeted toward an in-group,

partisanship should be overruled by the attitudes toward the

content of the policy (

Nicholson, 2012). Therefore, I expect that

support for a dragnet policy is slightly less likely than support for

a targeted or not specified policy. However, the level of citizens’

support should still be comparatively high when the suggested

policy is proposed by their preferred party.

H3b: Citizens’ support for counter-terrorism measures

decreases when they are the target of that policy, even when

they are inclined to the policy-proposing party.

3. Data and method

3.1. Sample

I analyze data from a pre-registered

2

survey experiment

conducted in Germany in June 2022. The sample matches

the general population in terms of age, gender, and education

(N = 2,045).

3

No sampling weights were applied, since

highly qualitative survey data is giving precise estimates

while preserving high statistical power (

Miratrix et al.,

2018

). The experiment was part of a larger survey; the

median response time was 20.02 min. At the beginning of

the survey, an attention check was included; participants

who failed the attention check were excluded from further

participation in the survey and no answers were collected

from them (91.73 percent of the respondents passed t he

attention check).

3.2. Experimental setup

The study uses a 4 × 3 × 3 × 3 full factorial between-

subjects design (

Auspurg and Hinz, 2015) resulting in 108

unique vignettes in total, of which every respondent randomly

2 Pre-registration plan on osf: https://osf.io/7rs5v. Note that the

wording of hypothesis H1 and H3a has been changed from “targeted”

to “personally threatened” to make the wording consistent throughout

the study. In H2b, H3a, and H3b, “ideology” has been replaced with

“inclined/disinclined” to match the wording in the hypothesis with the

design of the experiment. The wording of H3b has been rearranged to

match the wording of H3a.

3 The study was conducted by the survey company Bilendi & respondi.

The distribution of demographic variables in the sample can be found in

the Appendix (

Supplementary material).

Frontiers in Political Science 05 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

received one. In a short text (Sauer et al., 2020), respondents

were asked to imagine a terror ist attack. The following paragraph

shows an example of a vignette with manipulated dimensions

highlighted in italics:

Imagine that a terrorist attack conducted by a right-wing

group takes place. An explosion occurs, injuring several

people. There is a serious danger for citizens like you, your

family and friends.

To ensure that attacks like this are prevented in the

future, politicians from The Greens want to increase

surveillance measures. These measures shall target

every citizen in the country. The measure includes the

monitoring of telephone c alls, letter mail, e-mails, and

social m edia accounts, as well as chats on cell phones

or smartphones.

Details of this attack are described using the four treatment

dimensions. Two dimensions each describe the terrorist attack

and the counter-terrorism measure. The first dimension

describes the motivation of the perpetrator as Islamist, right-

wing radical, or climate-radical. Islamist terrorism became

very prominent through the attacks of 9/11. Since it is well-

known and investigated very broadly, I included this attribute

to contextualize the other two motivations: right-wing and

climate-radical. Right-wing terrorism is a common source of

terrorism and has been present for over a decade in western

democracies. Especially in Germany, where the study was

fielded, right-wing motivated terrorism is the predominant form

and responsible for the largest attacks.

4

The third attribute

is climate-radical terrorism, often also called ecoterrorism.

Even though this type of terrorism is less well-known as

attacks with a different background, I argue that it is the

most promising motivation to test my hypothesis for several

reasons: First, it is not completely unknown, since ecoterrorism

as a term has appeared in mainstream media in the last two

decades, for example in the U.S. (

Smith, 2008). Some att acks of

radical environmentalist have been classified as terrorist attacks

(

Hirsch-Hoefler and Mudde, 2014).

5

Second, environmental

4 Recent examples are the shooting in Hanau in 2020 (https://www.

nytimes.com/2020/02/20/world/europe/germany-hanau-shisha-bar-

shooting.html

, accessed July 15, 2022) and the antisemitic attack in

Halle in 2019 (

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/09/two-

people-killed-in-shooting-in-german-city-of-halle

, accessed July 15,

2022). In the early 2000s, a series of attacks was conducted by the

Nationalist Social Underground ( NSU). Reports in the media lasted for

several years due to a long trial (

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/

07/world/europe/trial-of-neo-nazi-beate-zschape-in-germany.html

,

accessed July 15, 2022).

5 For a historical overview, see,

Loadenthal, 2017. An exemplary

group is the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), w ho for example

attacked private property in the U.S. in 2008 (

https://web.

archive.org/web/20080306184703/http://ap.google.com/article/

ALeqM5hQlKz_UjBgvhm8rfGiTaQYS82a5gD8V66KUG0

, accessed

protection and its implication to slow down climate change are

very salient in the public discourse. In Germany, it was one

of the major issues during the last national election campaign

in 2021. Many people have a strong opinion on the issue.

It is not too hard to imagine that somebody with extreme

attitudes toward climate protection will turn to terrorism at

some point to underline their message with violence. There

are already books with activist intent that discuss the use

of violence to highlight the importance of mitigating climate

change, e.g.,

Malm, 2021. Third, this setup of right-wing

and climate-radical motivation mirrors the setup of the third

treatment dimension, the party that proposes the counter-

terrorism policy. For this dimension, I use the Alternative

für Deutschland (AfD) and the Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (The

Greens). While the AfD is classified as the furthest to the right

of the major parties in Germany, The Greens take strongly

opposing positions to the AfD on many policy issues. Therefore,

the parties are very distinguishable and appeal to different

people

6

.

The second treatment dimension describes whether

someone is personally threatened by a terrorist att ack (or not).

The fourth dimension describes whether someone is targeted

by a counter-terrorism policy (or not). Every dimension also

contains a control group, in which the attribute was not

specified or mentioned

7

.

3.3. Measures

The treatment text concludes with a description of a security

policy involving the surveillance of telephone calls, letters, e-

mails, social media accounts, and chats on cell phones or

smartphones. Afterwards, the respondents were asked to state

to which degree they would support the surveillance policy on a

ten-point scale. This serves as main dependent variable for the

study. As stated earlier, surveillance ent ails the conflict between

security and privacy r ights and can restrict ordinary citizens. The

case of surveillance is also well-suited t o examine the hypothesis

about partisanship, since the “cuts into pr ivacy rights beyond

what voters accept should reduce political support for the

incumbent” (

Epifanio, 2011, p. 403). Therefore, differently than

in the case of other counter-terrorism measures, the preferences

September 28, 2022) and a cableway in Germany in 2013 (https://

web.archive.org/web/20130905085530/http://www.ndr.de/regional/

niedersachsen/harz/seilbahn167.html

, accessed September 28, 2022).

6 The alternative would have been to use left-wing terrorism as

opposed to right-wing terrorism. However, left-wing terrorism has not

been present in the past two decades. Also, the political party in Germany

furthest to the left is quite unpopular, with a voter turnout of 5%.

7 See Appendix (

Supplementary material) for an overview of the

dimensions and attributes and detailed vignette wording.

Frontiers in

Political Science 06 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

for surveillance really be come a balancing act between security

and civil liberties.

To identify respondents’ partisanship, I use a pre-treatment

measure that asks respondents to rate their level of liking or

support for each party on a scale from one (“st rong aversion”) to

10 (“strong inclination”). The three lowest categories are coded

as aversion, the three highest as inclination and t he remaining

four as neutral

8

.

3.4. Analysis

To test the impact of the single dimensions, I compare

average marginal component effects (AMCEs;

Hainmueller

et al., 2014

).

9

To study the interdependence of the dimensions,

e.g., terrorist threat and being target of a policy, I use the

framework by

Egami and Imai (2019).

4. Results

4.1. Main results

Figure 1 shows the AMCEs for the four treatment

dimensions. The first two dimensions concern the side of the

terrorists. For the first dimension, terrorist threat, the effect

does not differ between the control group and the treatment

group. The additional information in the hypothetical scenario

that respondents are in danger or not does not influence their

support for the surveillance policy. The second dimension, the

specification of the motivation of terrorists, also has no influence

on respondents’ support for the counter-terrorism measure.

The third and fourth dimension describe the counter-

terrorism side. A specification of the policy-proposing party

leads to a significant and substantial decrease in policy support

(−0.49 [CI: −0.81, −0.17] when proposed by The Greens and

−0.91 [CI: −1.23, −0.59] when proposed by the AfD). When

the policy-proposing party is not specified, respondents might

think of their preferred party (or at least not about a party they

dislike), which leads to a stronger support of the policy. The

majority of the respondents feel aversion toward the two parties

specified in the treatment (40.52 percent toward The Greens,

72.36 percent toward the AfD) or are neutral toward them (37.32

percent toward The Greens, 15.86 percent toward the AfD).

Only a small share is inclined to each of the two parties (22.16

8 In robustness analyses, I vary the thresholds for categorizing

respondents as inclined or disinclined to a party. For further validation,

a secondary ite m is used, which asks respondents for their vote choice if

a general election were held next Sunday (Sonntagsfrage).

9 I also present marginal means in the Appendix

(

Supplementary material) to avoid the problem of having a fixed

reference category

(Leeper et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1

Average marginal component eect for the four treatment

dimensions. The dependent variable is the support for a

surveillance policy (10-point scale). The reference category for

each dimension is a control attribute in which the dimension

was not mentioned or specified. Lines around the point

estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals.

percent to The Greens, 11.77 percent to the AfD).

10

Accordingly,

on average respondents do not have a positive attitude toward

the two parties, which leads to a lower support for the policy.

The fourth and last dimension specifies whether the

proposed surveillance policy should be dragnet or targeted at

suspect individuals or groups. Respondents’ support for t he

dragnet policy is substantially and significantly lower (−0.57

[CI: −0.89, −0.25]) than for the not specified policy (control).

Respondents’ support for the targeted policy is substantially and

significantly higher (0.66 [CI: 0.34, 0.98]) than for the control.

These results do not corroborate Hypothesis 1a, because the

direct threat of a terrorist attack does not change respondents’

policy support.

11

In contrast, there is strong evidence for

Hypothesis 1b: respondents do not want to be personally

restricted by the given surveillance policy and are less likely to

support dragnet measures.

12

10 Regularly conducted surveys about Germans’ party preferences

(Sonntagsfrage) show similar numbers for the survey period.

11 For a discussion see Section 5.

12 This finding is further supported by a manipulation check, which

shows that respondents feel significantly and substantially more restricted

when the described surveillance measure is dragnet and not targeted (see

Supplementary Section 5).

Frontiers in Political Science 07 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

FIGURE 2

Predicted values for support for the dierent surveillance policies based on personal threat. Lines around the point estimates indicate 95 %

confidence inte rvals.

4.2. Interactions

Figure 2 shows the predicted policy support dependent

on personal threat and policy scope. In the absence of

personal threat, there is no significant difference between

support for a targeted measure and support for a dragnet

surveillance measure. In contrast, when citizens are personally

threatened, the support for a targeted measure is significantly

and substantially larger than support for a dragnet measure.

While personal threat increases the preference for a targeted

over a dragnet measure, the effect differs from the expectations

in Hypothesis 1c that support for surveillance would be

higher under personal threat, independent of the policy scope.

Therefore, there is no supporting evidence for Hypothesis 1c.

Figure 3 shows the predicted values for respondents’ policy

support based on the policy-proposing party and respondents’

inclination or aversion to the AfD or The Greens.

13

When the

policy is proposed by the AfD, support for the policy differs very

strongly between respondents who are averse toward the AfD

and respondents who are neutral or pro toward the AfD, by an

average of roughly two points on a ten-point scale. However,

respondents who sympathize with the AfD are not more likely to

support the policy than neutral respondents. The panel for The

Greens shows a similar picture. Policy support is identic al on

average among neutral and inclined respondents. Respondents

who are averse to The Greens are on average 1.3 points less likely

to suppor t the policy than respondents who are sympathetic with

or neutral to The Greens.

This evidence supports Hypothesis 2a that respondents will

be less likely to support a counter-terrorism me asure when it

is pr oposed by a party they dislike. There is no support for

Hypothesis 2b that respondents will be more likely to support

13 See Appendix (Supplementary material) for marginal means and

results using the respondents’ hypothetical party vote.

such a measure when they are inclined to t he policy-proposing

party than when the policy-proposing is not specified.

To test Hypothesis 2c, it is necessary to compare whether

the respondents have the same motivation as the terrorists.

Using the previous setup, I investigate whether partisans of

the AfD change their policy pr eference when the terrorists’

motivation is right-wing extremist. I repeat this procedure for

policy preferences of partisans of The Greens when terrorists’

motivation is climate-radical. The results in

Figure 4 show

that the motivation of terrorists does not influence the policy

support of partisans who have a similar ideology in a less

extreme form. Since partisans of a single party are still a

very heterogeneous group, I investigated additional subgroups

based on their left–right self-assessment, their environmental

attitudes, and their level of extremism. None of t hese yield

any reduction in support for the counter-terrorism measure.

Furthermore, I investigated combinations of these attributes:

a high propensity to violence/high degree of extremism and

a right self-assessment or a strong personal commitment to

environmental protection (right extremists, far-right violent

extremists, climate extremists, climate-violent extremists). Since

the subgroups in this analysis are very small, the results should

be taken carefully, but again t here is no difference in support

of these subgroups. Respondents’ preferences for supporting a

counter-terrorism measure is not driven by the motivation of

the terrorists; consequently Hypothesis 2c is not confirmed.

For the remaining two hypotheses, 3a and 3b, we have to

look at three-way interactions. For Hypothesis 3a, I compare

how support for a policy proposed by a party to which

respondents are averse changes depending on whether the

terrorist attack poses a personal threat to the respondents

(

Figure 5). When the policy is proposed by The Greens, a small

(+0.48) but not significant increase in support can be seen.

When the policy is proposed by the AfD, the support deceases

in comparison to the control group. This effect is even smaller

Frontiers in Political Science 08 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

(−0.25) and not significant. For Hypothesis 3b, I compare how

support for a policy proposed by a party to which respondents

are inclined changes depending on the policy being dragnet

(

Figure 6). For both parties, I find a very small (Greens −0.35;

AfD 0.48) and not significant effect. In sum, the evidence does

not support Hypothesis 3a and 3b.

5. Discussion

In t his paper, I investigated how citizens cope with threat,

restriction, and ideology (in the form of partisanship) and what

influence this has on their preferences for civil liberties or

security. The central findings of the study are that (a) citizens

who are averse to the party that proposes a security policy

are clearly less likely to support this policy and (b) citizens

are less likely to support a security policy if it is dragnet and

therefore restricts the citizens themselves. These two attributes

dominated the preference formation in comparison to other

factors. The study extends our understanding of (1) the influence

of political polarization in a context in which citizens prefer a

policy but have an aversion to the political actor that proposes

the policy, (2) citizens’ s upport for surveillance when they

are personally affected, and (3) the rejection of any kind of

terrorism, independent of the underlying ideology.

A direct translation to the real world depends on parties’

behavior after an attack. If parties stand united, a rally-’round-

the-flag effect can occur, in which partisanship plays a minor

role and citizens support the government’s action (

Kam and

Ramos, 2008

). However, parties do not necessarily stand united.

For example, in the aftermath of the aforementioned right-

wing terrorist attack on people believed to have a migrant

background in 2020 in Hanau, Germany, parties have not taken

a unified position. Medeiros and Makhashvili (2022) examined

the discourse on Twitter, where parties and individual politicians

expressed their condolence, but also stated their opinions.

The evolving discourse consisted of mainly two clusters. The

first cluster contained messages from journalists, legacy media

accounts, anti-racist activists, and politicians from the SPD and

Die Linke (center-left and left-wing party). The second cluster

was centered around the AfD, far-right political actors, and

far-right spam accounts. The authors interpret the discourse

as polarized (

Medeiros and Makhashvili, 2022, p. 45). This

example is not an exception of the AfD being isolated in their

position (

Urman, 2020). In such a case, i.e., when parties appear

not uniform, the results of the study are likely to hold. The

acceptance of policy proposals will depend to a certain degree

on the policy-proposing party.

While this study investigated the specific context of

terrorism, its implications are likely to apply to other external

shocks. Terrorism is comparable to the threat of violence from

other sources such as war or crime. Similarities appear in

two regards, in the physical dimension and in the symbolic

dimension (

Vergani, 2018, p. 23). This has also been shown in

empirical studies that compared citizens’ willingness to accept

cuts in civil liberties when they are faced with crime instead of

terrorism (

Mondak and Hurwitz, 2012).

The manipulation of threat as a single factor had no

influence on citizens’ support for surveillance (contrary to the

expectations stated in Hypothesis 1a). This is in line with

other experimental studies (such as Helbling et al., 2022),

in which a treatment that included terrorist threat did not

influence citizens’ policy attitudes. However, it contradicts other

experimental studies that have successfully shown an impact of

terrorist threat on policy support by mentioning the number of

victims in the past 3 years in their treatment (

Ziller and Helbling,

2021

). In the present study, citizens were asked to imagine a

terrorist attack. This attack was described as (a) threatening

for the individual citizen, their friends, and family, (b) not

threatening for the individual citizen, their friends, and family,

or (c) not further specified. Accordingly, respondents always had

to imagine a terrorist attack. Even though respondents in group

(c) did not get any information whether the threat was personal

or not, they still were asked to t hink about a terrorist attack.

Since terrorism is generally t hreatening, this could explain why

no differences were found between the threat conditions. An

alternative explanation would be a disconnection of perceived

threat and actual situations: “Subjectively perceived threats do

not necessarily have to correspond to an objectively threatening

situation—if the latter can be determined at all” (

Trüdinger,

2019

, p. 33). If citizens did not perceive the shown description

as personally threatening , but feel threatened by terrorism in

general, then we would expect no impact of the treatment

dimension. This argument is supported by an additional analysis

in which the perceived personal threat is investigated based

on the treatment dimensions. The manipulation of threat

did not change how respondents perceived personal threat

(see

Supplementary Section 5). A third explanation might be

that social threat instead of personal threat explains citizens’

preferences to increase security at the cost of civil liberties

(

Huddy et al., 2002, p. 488). Counter-terrorism policies are

rather an answer to threat that affects the whole of society than

to one that affects the individual. As previous research on policy

preferences has shown, people try to evaluate what is not only

the best for themselves but also for their surroundings (

Sears

et al., 1980

). Therefore, they do not necessarily form policy

preferences only according to their own situation and feelings.

However, this explanation is less convincing since empirical

studies have already shown the impact of personal threat on

security preferences (Hetherington and Suhay, 2011; Asbrock

and Fritsche, 2013

).

For the impact of personal threat on support for targeted

and dragnet policies, the result was rather surprising (see

Figure 2). Personal threat does not increase the overall

support for counter-terrorism policies (as expected prior

to the study, stated in Hypothesis 1c), but instead changes

Frontiers in Political Science 09 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

FIGURE 3

Predicted values for support for the surveillance policy based on the policy-proposing party and the inclination/disinclination to the respective

party. Lines around the point estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 4

Predicted values for the support of the surveillance policy based on the motivation of terrorists and the inclination/disinclination to the AfD or

The Greens. Lines around the point estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 5

Predicted values for support of the surveillance policy. The policy is proposed by a party citizens are averse to. Results are shown for dierent

degrees of exposure to threat. Lines around the point estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Frontiers in Political Science 10 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

FIGURE 6

Predicted values for support of the surveillance policy. The policy is proposed by a party citizens are inclined to. Results are shown for dierent

policy types. Lines around the point estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals.

the preference for the type of policy. When citizens are

under thr eat, the support for targeted measures increases

and the support for dragnet measures decreases compared

to measures when citizens are under no personal threat.

One possible explanation could be that people who are

personally threatened do not want to be additionally

targeted by a policy. They do not want to carry a double

burden. Testing this hypothesis or alternative ones is left to

future research.

In contrast to perceived threat, partisanship has a

strong influence on citizens’ support for a security policy.

However, real-world threat is expected to reduce the

strength of partisan cues. Instead of relying on party cues

only, citizens make use of the best evidence they can find

(

Druckman et al., 2021). In the case of the here discussed

security policy, citizens would be expected to evaluate how

effective the policy is to prevent them from threat. When

considered effective, the impact of partisanship is expected

to decrease. This relationship remains to be investigated in

future studies.

The second dimension in which no differences in policy

support was found concerns the motivation of the terrorists

in the treatment. Hypothesis 2c stated that the support

for counter-terrorism measures would decrease when citizens

share the ideology of terrorist actors. While it was quite

unlikely to find support for terrorist actions in the general

population, it is reassuring that terrorist motivation does not

influence citizens’ support for counter-measures. Normatively

speaking, this is positive news for democracy. A natural

experiment has shown that right-wing extremist attacks

shifted citizens who hold a rig ht ideology away from

this ideology (

Pickard et al., 2022). The present study

contributes to this finding by showing that other ideologies

also do not lead respondents to change their preference for

civil liberties.

Lastly, there was no significance for the small effect

sizes for Hypothesis 3a and 3b. Personal threat did not

overrule the disliking of a party and becoming target of

surveillance did not lower citizens’ policy support when the

policy was proposed by the citizens’ preferred party. Since

three-way interactions were needed in this study to test

these hypotheses, the experimental power was rather low,

which makes it difficult to detect small effect sizes. As a

result, these hypotheses cannot be rejected with hig h certainty.

Instead, this provides ground for future research with more

tailored experimental designs to examine the relationship

between action by preferred parties and restrictions for

individual citizens.

Subject to the limitations noted above, the findings

indicate that citizens’ attitudes toward security are rather

shaped by counter-terrorism than by terrorism. First, citizens’

agreement with security policies rather depends on the

scope of the policy and whether they are affected by it.

Second, their support of these policies depends on their

liking or disliking of the policy-proposing party. Since

counter-terrorism, and the discussed issue of surveillance in

particular, is preventive in nature, these factors outweigh the

terrorist motivation and personal threat. The study contributes

to the understanding of citizens’ preferences for security

policies in a context in which the need for such policies

is emphasized. In a broader sense, this has implications for

political polarization because citizens are less likely to support

otherwise preferred policies if they are proposed by a party the

citizens disliked.

Frontiers in Political Science 11 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

Data availability statement

The dat a set and replication file are available online

(

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2ZOPHQ). Further inquiries can

be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed

and approved by Ethics Committee of the University of

Mannheim. The patients/participants provided their written

informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work

and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Mannheim

Centre for European Social Research (MZES).

Conflict of interest

The aut hor declares that the research was conducted in

the absence of any commercial or financial relationships

that could be construed as a potential conflict

of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those

of the authors and do not necessarily represent those

of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher,

the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be

evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by

its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by t he

publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be

found online at:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/

fpos.2022.1006711/full#supplementary-material

References

Asbrock, F., and Fritsche, I. (2013). Authoritarian reactions to terrorist

threat: who is being threatened, the m e or the we? Int. J. Psychol. 48, 35–49.

doi: 10. 1080/00207594. 2012.69 5075

Auspurg, K., and Hinz, T. (2015). Factorial Survey Ex periments. Thousand Oaks,

CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781483398075

Barber, M., and Pope, J. C. (2019). Does party Trump ideology?

Disentangling party and ideology in America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 38–54.

doi: 10. 1017/S0003055418000795

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., and Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of

Partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Polit. Behav. 36, 235–262.

doi: 10. 1007/s11109-013-9238- 0

Bozzoli, C., and Müller, C. (2011). Perceptions and attitudes following

a terrorist shock: evidence from the UK. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 27, S89–S106.

doi: 10. 1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.06.005

Breznau, N. (2021). The welfare state and risk perceptions: The novel

coronavirus pandemic and public concern in 70 countries. Euro. Soc. 23, S33–S46.

doi: 10. 1080/14616696. 2020.17 93215

Carey, J., Clayton, K., Helmke, G., Nyhan, B., Sanders, M., and Stokes, S.

(2022). Who will defend democracy? Evaluating tradeoffs in candidate support

among partisan donors and voters. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties. 32, 230–245.

doi: 10. 1080/17457289. 2020.17 90577

Caton, C., and Mullinix, K. J. (2022). Partisanship and support for restricting the

civil liberties of suspected terrorists. Polit. Behav. doi: 10.1007/s11109-022-09771-9

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of

group influence on political beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808–822.

doi: 10. 1037/0022-3514. 85.5. 808

Cohen-Louck, K. (2019). Perception of the threat of terrorism. J. Interpers.

Violence 34, 887–911. doi: 10.1177/0886260516646091

Crawford, J. T., and Pilanski, J. M. (2014). Political intolerance, right and left.

Polit. Psychol. 35, 841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.0092 6.x

Davis, D. W., and Silver, B. D. (2004). Civil liberties vs. security: public opinion

in the context of the terrorist attacks on America. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 28–46.

doi: 10. 1111/j.0092-5853. 2004.0 0054.x

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2021).

Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat. Hum.

Behav. 5, 28–38. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Egami, N., and Imai, K. (2019). Causal interaction in factorial

experiments: application to conjoint analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 114, 529–540.

doi: 10. 1080/01621459. 2018.14 76246

Epifanio, M. (201 1). Legislative response to international terrorism. J. Peace Res.

48, 3 99–411. doi: 10.1177/0022343311399130

Feldman, S. (2013). Comments on: authoritarianism in social context: the role

of threat. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 55–59. doi: 10. 1080/00207594.20 12.742196

Fritsche, I., Jonas, E., and Kessler, T. (2011). Collective reactions to thre at:

implications for intergroup conflict and for solving societal crises. Soc. Issues Policy

Rev. 5, 101–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01027.x

Gadarian, S. K. (2010). The politics of threat: how terrorism news shapes foreign

policy attitudes. J. Polit. 72, 469–483. doi: 10.1017/S0022381609990910

Giani, M., Epifanio, M., and Ivandic, R. (2021). Wait and see? Public opinion

dynamics after terrorist attacks. socarXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/qt7s4

Graham, M. H., and Svolik, M. W. (2020). Democracy in America? Partisanship,

polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. Am.

Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 392–4 09. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000052

Haider-Markel, D. P., Joslyn, M. R., and Al-Baghal, M. T. (2006). Can

we frame the terrorist threat? Issue frames, the perception of threat, and

opinions on counterterrorism policies. Terror. Polit. Violence 18, 545–559.

doi: 10. 1080/0954655060088 0625

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., and Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in

conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference

experiments. Polit. Anal. 22, 1–30. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpt024

Frontiers in Political Science 12 frontiersin.org

Jäger 10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711

Harteveld, E., and Wagner, M. (2022). Does affective polarisation increase

turnout? Evidence from Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. West Eur. Polit.

1–28. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2087395

Hegemann, H., and Kahl, M. (2018). “Sicherheit vs. freiheit?

Probleme und dilemmata der terrorismusbekämpfung,” in Terrorismus

und Terrorismusbekämpfung: Eine Einführung, Elemente der Politik, H.

Hegemann and M. Kahl (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien), 169–188.

doi: 10. 1007/978-3-658 -16086-9_7

Helbling, M., and Meierrieks, D. (2020). Transnational terrorism and restrictive

immigration polici es. J. Peace Res. 57, 564–580. doi: 10.1177/0022343319897105

Helbling, M., Meierrieks, D., and Pardos-Prado, S. (2022). Terrorism

and immigration policy preferences. Defence Peace Econ. 1–14.

doi: 10. 1080/10242694. 2022.20 61837

Heltzel, G., and Laurin, K. (2020). Polarization in America: two possible futures.

Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.008

Hetherington, M., and Suhay, E. (2011). Authoritarianism, threat, and

Americans’ support for the war on terror. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 546–560.

doi: 10. 1111/j.1540-5907. 2011. 00514.x

Hirsch-Hoefler, S., and Mudde, C. (2014). “Ecoterrorism”:

terrorist threat or political ploy? Stud. Conflict Terror. 37, 586–603.

doi: 10. 1080/1057610X. 2014. 913121

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., Capelos, T., and Provost, C. (2002). The consequences of

terrorism: disentangling the effects of personal and national t h reat. Polit. Psychol.

23, 48 5–509. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00295

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., Taber, C., and Lahav, G. (2005). Threat,

anxiety, and support of antiterrorism policies. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 593–608.

doi: 10. 1111/j.1540-5907. 2005. 00144.x

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., and Weber, C. (2007). The political consequences of

perceived threat and felt insecurity. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit . Soc. Sci. 614, 131–153.

doi: 10. 1177/000271620730 5951

Jenkins-Smith, H. C., and Herron, K. G. (2009). Rock and a hard place: public

willingness to trade civil rights and liberties for greater security. Polit. Policy 37,

1095–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2009.00215.x

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., and Napier, J. L. (2009). Political ideology: its

structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 307–337.

doi: 10. 1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600

Jungkunz, S. (2021). Political polarization during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 622512. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.622512

Kam, C. D., and Ramos, J. M. (2008). Joining and leaving the rally:

understanding the surge and decline in presidential approval following 9/11. Public

Opin. Q. 72, 619–650. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfn055

Kawecki, D. (2022). End of consensus? Ideology, partisan identity and affective

polarization in Finland 2003–2019. socarXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/4k7u9

Kossowska, M., Trejtowicz, M., de Lemus, S., Bukowski, M., Hiel, A. V., and

Goodwin, R. (2011). Relationships between right-wing authoritarianism, terrorism

threat, and attitudes towards restrictions of civil rights: A comparison among four

European countries. Brit. J. Psychol. 102, 245–259. doi: 10.1348/000712610X517262

Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences

in c onjoint experiments. Polit. Anal. 28, 207–221. doi: 10.1017/pan.2019.30

Loadenthal, M. (2017). “Eco-terrorism”: an incident-driven history of attack

(1973–2010). J. Study Radical. 11, 1–34. doi: 10.14321/jstudradi.11.2.0001

Lupton, R. N., Smallpage, S. M., and Enders, A. M. (2020). Values and political

predispositions in the age of polarization: examining the relationship between

partisanship and ideology in the United States, 1988–2012. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 50,

241–260. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000370

MacKuen, M., and Brown, C. (1987). Political context and attitude change. Am.

Polit. Sci. Rev. 81, 471–490 . doi: 10.2307/1961962

Malm, A. (2021). How to Blow Up a Pipeline. Verso Books.

Marcus, G. E., Sullivan, J. L., Theiss-Morse, E., and Wood, S. L. (1995). With

Malice toward Some: How People Make Civil Liberties Judgments. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139174046

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality. New York, NY: Prabhat

Prakashan.

Medeiros, D., and Makhashvili, A. (2022). United in grief? Emotional

communities around the far-right terrorist attack in Hanau. Media Commun. 10,

39–49. doi: 10.17645/mac.v10i3.5438

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., and Campos, L. F. (2018).

Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments.

Polit. Anal. 26, 275–291. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.1

Mondak, J. J., and Hurwitz, J. (2012). Examin ing the terror exception:

terrorism and commitments to civil liberties. Public Opin. Q. 76, 193–213.

doi: 10. 1093/poq/nfr068

Mu noz, J., Falcó-Gimeno, A., and Hernández, E. (2020). Unexpected event

during survey design: promise and pitfalls for causal inference. Polit. Anal. 28,

186–206. doi: 10.1017/pan.2019.27

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 52–66.

doi: 10. 1111/j.1540-5907. 2011.0 0541.x

Peffley, M., Knigge, P., and Hurwit z, J. (2001). A multiple values model of

political tolerance. Polit . Res. Q. 54, 379–406. doi: 10.1177/106591290105400207

Pickard, H., Efthyvoulou, G., and Bove, V. (2022). What’s left after

right-wing extremism? The effects on political orientation. Eur. J. Polit. Res.

doi: 10. 1111/1475-6765. 12538

Pink, S. L., Chu, J., Druckman, J. N., Rand, D. G., and Willer, R. (2021). Elite

party cues increase vaccination intentions among Republicans. Proc. Natl. Acad.

Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2106559118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106559118

Pronin, E., Kennedy, K., and Butsch, S. (2006). Bombing versus negotiating: how

preferences for combating terrorism are affected by perceived terrorist rationality.

Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28, 385–392. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp2804_12

Rohde, I. M. T., and Rohde, K. I. M. (2011). Risk attitudes in a social context. J.

Risk Uncertainty 43, 205–225. doi: 10.1007/s11166-011-9127-z

Ruby, C. L. (2002). The definition of terrorism. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2,

9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2002.00021. x

Saikkonen, I. A.-L., and Christensen, H. S. (2022). Guardians of democracy or

passive bystanders? A conjoint experiment on elite transgressions of democratic

norms. Polit. Res. Q. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/j6tvy

Sauer, C., Auspurg, K., and Hinz, T. (2020). Designing multi-factorial

survey experiments: effects of presentation style (text or table), answering scales,

and vignette order. methods data analyses 14, 195–214. doi: 10.12758/mda.

2020.06

Schmid, A. P. (2011). The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. Abington;

New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.4324/9780203828731

Sears, D. O., Lau, R. R., Tyler, T. R., and Allen, H. M. (1980). Self-interest vs.

symbolic politics in policy attitudes and presidential voting. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 74,

670–684. doi: 10.2307/1958149

Siri, J. (2018). The alternative for Germany after the 2017 Election. German Polit.

27, 1 41–145. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2018.1445724

Smith, R. K. (2008). “Ecoterrorism”?: A critical analysis of the

vilification of radical environmental activists as terrorists. Environ. Law

38, 4 0.

Somer, M., and McCoy, J. (2018). Déjá vu? polarization and

endangered democracies in the 21st century. Am. Behav. Sci. 62, 3–15.

doi: 10. 1177/0002764218760 371

Stimson, J. A. (1975). Belief systems: constraint, complexity,

and the 1972 election. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 19, 393–417. doi: 10.2307/

2110536

Sullivan, J. L., and Hendriks, H. (2009). Public support for civil

liberties pre- and post-9/11. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 5, 375–391.

doi: 10. 1146/annurev.lawsocsci.093008.131525

Svolik, M. W. (2019). Polarization versus democracy. J. Democracy 30, 20–32.

doi: 10. 1353/jod.2019.0039

Trüdinger, E.-M. (2019). Perceptions of threat and policy attitudes: The case of

support for anti-terrorism policies in Germany. Habilitation.

Urman, A. (2020). Context matters: political polarization on

Twitter from a comparative perspective. Media Cult. Soc. 42, 857–879.

doi: 10. 1177/0163443719876 541

van Leeuwen, M. (2003). “Democracy versus terrorism: balancing security and

fundamental rights,” in Confronting Terrorism, ed M. van Leeuwen (Leiden: Brill |

Nijhoff), 227–233. doi: 10.1163/9789047403227_014

Vergani, M. (2018). How Is Terrorism Changing Us? Singapore: Springer

Singapore. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8066-1

Wright, G. C., Erikson, R. S., and McIver, J. P. (1985). Measuring

state partisanship and ideology with survey data. J. Polit. 47, 469–489.

doi: 10. 2307/2130892

Wynter, T. (2017). Counterterrorism, counterframing, and perceptions of

terrorist (i r)rationality. J. Glob. Sec. Stud. 2, 364–376. doi: 10.1093/jogss/ogx017

Ziller, C., and Helbling, M. (2021). Public support for state surveillance. Euro. J.

Polit. Res. 60, 994–1006. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12424

Frontiers in Political Science 13 frontiersin.org