COVID-19 Vaccination Field Guide:

12 Strategies for Your Community

U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention

Table

of Contents

4

Introduction

4 About This Guide

5 Using this Guide

6

Common Barriers

6 Structural Barriers

6 Behavioral Barriers

7 Informational Barriers

8

Understanding

Your Community

8 The Social Vulnerability

Index (SVI)

9 Walk a Mile Exercise

11 Diagnostic Tool to

Identify Factors and

Strategies

12 Rapid Community

Assessment (RCA)

13

Vaccine

Confidence and

Uptake Strat

egies

15 Strategy 1:

Vaccine Ambassadors

17 Strategy 2:

Medical Provider

Vaccine Standardization

18 Strategy 3:

Medical Reminders

20 Strategy 4:

Motivational Interviews

21 Strategy 5:

Financial Incentives

22 Strategy 6:

School-Located

Vaccination Programs

23 Strategy 7:

Home-Delivered

Vaccination

24 Strategy 8:

Workplace

Vaccination Programs

25 Strategy 9:

Vaccine Requirements

27 Strategy 10:

Eective Messages

Delivered by Trusted

Messengers

29 Strategy 11:

Provider

Recommendation

30 Strategy 12:

Combating

Misinformation

4

T

he COVID-19 pandemic has affected millions of lives in communities across the world,

including in the United States. COVID-19 is unique in many ways, including its global impact,

its politicization, and the need for universal vaccination to combat the virus. When COVID-19

vaccines became available in the United States, millions of Americans eagerly sought out

and received them. Many see vaccination as the key to a post-pandemic life, yet millions of Americans

have still not been vaccinated despite eligibility and plentiful supply. Desire for receiving a COVID-19

vaccine among some minority populations, particularly Black or African American and Hispanic or

Latino populations, is high though uptake is lagging

12

. This indicates barriers related to access and

equity may be at play. For other populations, there is more hesitancy about getting vaccinated.

Communities with vaccination rates much lower than the national average may need to further

investigate and address barriers to COVID-19 vaccination.

People encounter barriers that can hinder or facilitate vaccinations. Barriers and facilitators range from

logistical and access issues, to personal beliefs and risk perception, to community beliefs and social

norms. Insights from behavioral health research can help determine strategies to help people get

vaccinated and promote near-universal uptake.

Health departments, community organizations, faith-based communities, and leaders from all sectors

of public life are making great efforts to promote COVID-19 vaccination. No single approach will work

for every community; in fact, as the research included here demonstrates, a combination of strategies

is generally most effective and will increase chances for success. This field guide highlights several

strategies derived from evidence-based practices that are being applied in communities across the

country to promote vaccine confidence and uptake.

About this Guide

This field guide offers intervention strategies to promote COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake

based on a rapid assessment of evidence that identified research-proven methods. This guide is

intended to support the work of health departments and community- and faith-based organizations

across the United States. It highlights some common barriers that communities experience in vaccine

confidence and uptake. Not all barriers are relevant in all communities; therefore, the second section

of this guide helps you understand the various needs of different communities and offers tools to help

you assess barriers and find potential solutions for your community of focus.

The final section describes 12 intervention strategies drawn from historical vaccination efforts that

have demonstrated positive outcomes through evaluation research. While most of the guide focuses

on increasing vaccine uptake, several strategies address increasing vaccine confidence. Each strategy

highlights the approach, population(s) served, location, barriers addressed, basis in research, and an

example of how the strategy is currently being applied to address COVID-19 vaccination.

Vaccine Confidence is the trust

that people have in recommended

vaccines and how they are

administered and developed.

Without some level of confidence,

people will not move toward

receiving a vaccine.

Vaccine Uptake refers to the

proportion of the population

that has received a vaccine.

1 PPRI Sta. (July 27, 2021). Religious Identities and the Race Against the Virus: (Wave 2: June 2021). Retrieved at:

https://www.prri.org/research/religious-vaccines-covid-vaccination/.

Ndugga, N., Hill, L., Artiga, S., and Parker, N. (August 18, 2021). Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. 2

Retrieved at: https://www.k.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

5

Using this Guide

This resource consists of three primary sections:

1. Common Barriers

This section of the guide tells about common barriers to vaccine confidence and uptake.

2. Understanding Your Community

This section offers tools you can use to identify and understand what barriers and facilitators may

be factors in your community of focus. You may need only one of these tools, or several to increase

your understanding of your community.

3. Vaccine Confidence and Uptake Strategies

Here you will find recommended strategies to increase vaccine confidence and uptake. The research

that supports the strategy is provided along with case study examples. More information about the

strategies, including guidance and implementation resources, are linked within the document

and provided in Appendix A.

Factor in cost of implementing the strategy

including dollars, time, level of effort, staffing.

Implement the strategy to have the most success

by having relevant community members involved in

planning and execution; obtain leadership buy-in.

Consider piloting the effort on a small scale

to measure success before attempting wider

implementation, especially if you are unsure

about a strategy.

6

Common Barriers

There are several common barriers to COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake. Leaders should

consider which barriers the people in their community are experiencing. Understanding the barriers

can help identify strategies most likely to increase vaccine uptake. The Behavioral and Social Drivers

(BeSD) framework described in Appendix D offers another way to view what drives or motivates

COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

Structural Barriers

Equity: COVID-19 vaccines may not be equally distributed, administered, or accessed in

communities nationwide, especially among under-resourced communities in urban and rural areas.

Cost: While COVID-19 vaccination is currently free, it requires time and resources. This includes figuring

out where to get vaccinated, making an appointment (if necessary), traveling to the vaccination site,

possibly taking time off from work, and recovery times for those who experience side effects. Some

people will need childcare or transportation, or are unable to take time off work to get vaccinated or

recover from side effects.

Access: Proximity and travel convenience to a vaccination site plays a large part in an individual’s

ability to get vaccinated. Vaccination clinic hours of operation may limit access for some as well.

Some people do not have transportation access, internet access, or the technical skills required to

search online for vaccination sites or appointments. People with disabilities, who are confined to

their homes, or who live in a long-term care or correctional facility, cannot travel to get a vaccine.

Policy: Existing policies, such as health insurance requirements for most medical services and

service restrictions for non-citizens and undocumented residents, can influence understanding of

vaccine access. People may not know they are eligible to receive a vaccine for free or be aware of

their employer’s policies on paid and unpaid leave for vaccination purposes. Also, employers are

encouraged, but not required, to have policies allowing employees to take paid leave to get

vaccinated and to recover if they have temporary side effects.

Behavioral Barriers

Inertia: Getting vaccinated takes planning and effort. Many individuals have difficulty making

decisions—especially large decisions—so instead of deciding, they do nothing. This tendency to

do nothing leaves people unvaccinated.

Prevailing Social Norms: Community norms often drive individuals’ actions. If trusted friends

or leaders in one’s community are against getting vaccinated, others will likely follow suit.

Forgetfulness: People may forget non-routine activities and procedures. They may forget to book their

vaccination appointments or to keep them.

Friction: Complex, inconvenient, or effort-provoking processes often lead people to fulfill immediate

wants and needs. If the process of booking or attending a vaccination appointment is too complicated,

they will not do it.

Misperception: Individuals may have vaccine opinions and beliefs based on scientific inaccuracies,

including that they are at low risk of getting severely sick with COVID-19, that the pandemic is being

exaggerated, or that vaccines are not effective. These inaccuracies are often spread in communities and

lead to fear, resistance, or mistrust.

7

Behavioral Barriers (Continued)

Mistrust: Lack of trust in institutions including government, medical institutions, and media, is

sometimes based on individual or communal experiences, and affects decisions about vaccination.

Uncertainty: Due to the novelty of the vaccines, many individuals feel uncertain about the short- and

long-term side effects, causing them to take a cautious “wait-and-see” approach to getting vaccinated.

With the course of the pandemic uncertain, people may believe it will soon be over. So, they may

believe they do not need a vaccine or want to wait to see if a different option will be approved to

address COVID-19 variants. Changes in official guidance can also make people feel uncertain about

their actions or decisions.

Politicization: COVID-19 vaccines have been politicized, making political affiliation a strong

determinant of vaccination beliefs and behaviors.

Informational Barriers

Cultural Relevance: Information about the vaccines is not always communicated in ways that reflect

sociocultural norms, beliefs, and realities. This can make information less relevant and confusing to

some individuals. Language may also be a barrier for non-native English speakers, especially given the

complexity and novelty of some vaccine information.

Health Literacy: Individuals may not fully understand the complex vaccine information being shared,

such as the multiple types of vaccines offered or lack of a clear and simple call to action. Adding to

confusion is changing guidance. People may lose trust or become confused when new information is

conveyed frequently; possibly not understanding that changing data impacts guidelines. People may

also have difficulty telling the difference between factual and false health information.

Mis- and Disinformation: Most mis- and disinformation that has circulated about COVID-19 vaccines

has focused on vaccine development, safety, and effectiveness, as well as minimizing the severity of the

pandemic and COVID-19 denialism.

Lack of Adequate Information: Some individuals lack the information they need to understand the

risks, benefits, and background of vaccine development to make an informed decision about getting

vaccinated. Information overload can also be a form of inadequate information as it can become

difficult for people to know what is relevant or current.

Misinformation is false information

shared by people who do not intend

to mislead others.

Disinformation is false information

deliberately created and

disseminated with malicious intent.

8

Understanding Your Community

To effectively address common barriers, it is important to identify and understand your community of

focus. Existing community data and previously conducted assessments, such as a health equity impact

assessment, may be available and useful in this process. Several tools are available to help with this,

including the Social Vulnerability Index, the “Walk a Mile” Exercise, the diagnostic tool, and the Rapid

Community Assessment (RCA) Guide.

The Social Vulnerability Index

The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) database

designed to help emergency response planners and public health officials identify and map

communities that will most likely need support before, during, and after a public health emergency,

including the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the SVI can help local leaders identify and decide which

populations to focus on.

About

Several factors, including poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing may weaken a

community’s ability to prevent human suffering and financial loss in a disaster. These factors are known

as social vulnerability. Reducing social vulnerability can decrease human suffering and economic loss.

The SVI ranks each county and census tract based on four themes:

1. Socioeconomic status

2. Household composition and disability

3. Minority status and language

4. Housing type and transportation

The higher the ranking, the more socially vulnerable the community is compared to other communities.

How to Use

The SVI data are displayed on an interactive map and can also be downloaded for a more granular look

into what determines a county or census tract’s SVI.

Applying the Data

Communities with higher SVI values have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 both in terms

of new cases and deaths. Often these communities face greater structural barriers to vaccination. Early

in the vaccine rollout, counties with high social vulnerability had lower COVID-19 vaccination coverage

than did counties with low social vulnerability. Efforts to increase vaccine access, confidence and

demand can be prioritized for these communities to decrease inequities.

Walk a Mile Exercise

The Walk a Mile (WAM) interactive exercise invites participants to “walk a mile” in the shoes of the

population of focus in their journey to vaccination, recognizing that each population may have

unique context and experiences. Barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 vaccination for specific

populations are identified.

About

The WAM exercise identifies these key steps in the vaccination process:

1. Knowledge, awareness, and beliefs

2. Intent

3. Preparation, cost, and effort

4. Point of service

5. Experience of care

6. After service

Factors at the individual, community, societal, and political level impact vaccine access, confidence

and demand at each of these stages and should be considered throughout the exercise.

FIGURE 1: Walk a Mile Graphic

Modified from UNICEF Journey to Health,

ESARO Network Meeting 2019

9

How to Use

The exercise is designed to be completed in small groups that are familiar with the population of

focus. This may include health department staff, community- or faith-based organizations, community

leaders, and others. A facilitator guides a group conversation while people play the roles of members

of the community of focus; brainstorming their enablers and barriers at each point along

the vaccination journey. If you would like a guide to conduct the WAM exercise, please email

confidenceconsults@cdc.gov.

10

FIGURE 2: Example of Completed WAM Exercise

Applying the Data

The responses from the WAM exercise give insight into how the vaccination journey is unique to

each population. For each population, the exercise generates a list of perceived and actual barriers

and facilitators. Understanding this can lead to identifying appropriate strategies to try to increase

vaccine confidence and uptake.

11

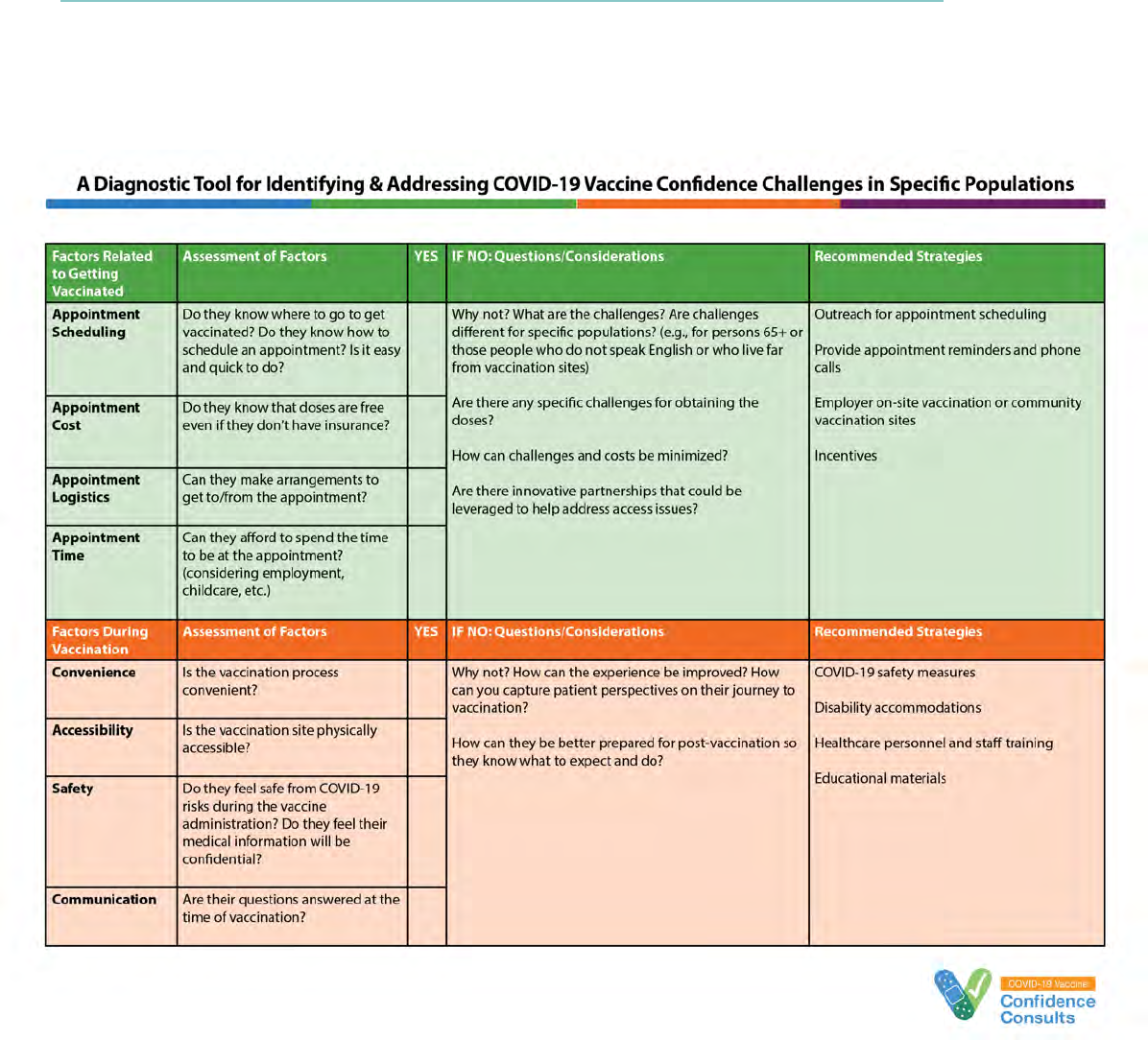

Diagnostic Tool to Identify Factors and Strategies

About

The diagnostic tool (see Appendix C) can be used for guided conversations to assess factors related to

vaccine confidence and uptake in a specific population and identify strategies to address challenges.

FIGURE 3: Example of Diagnostic Tool Questions

How to Use

The factors that build vaccine confidence, intention, and demand are located in the left column of the

tool. Questions related to the assessment of the factors are provided for each. If the answer to

the assessment question is yes, move to the next factor. If the answer to the question is no, proceed to

the “Considerations” column. If sufficient information is available to talk through the considerations,

proceed to the “Recommended Strategies” column.

This tool is designed to be used by anyone working to increase vaccination in a specific population.

The participants in the guided conversations could include health department staff, community- or

faith-based organizations, community leaders, and others.

The tool can be used with large or small groups. The key is to have people involved in the discussion

who know the most about the population of focus and the vaccination process.

Applying the Data

Once the recommended strategies have been identified, teams can think through how to design,

implement, and evaluate these interventions.

12

Rapid Community Assessment

In attempting to apply the tools above, an organization might find that they do not have enough

information to identify barriers and facilitators related to vaccine confidence or demand. An

organization might also consider it necessary to conduct a more in-depth community assessment to

determine the status of vaccine confidence or demand in their communities. In either case, the Rapid

Community Assessment (RCA) Guide can help identify and address these challenges.

About

The RCA can be used by staff of any organization working to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake who

wish to better understand the needs of the population of focus.

Use of this tool will help an organization to:

• Identify populations of focus at risk for low COVID-19

vaccine uptake.

• Gain an understanding of what people in the community

think about COVID-19 vaccines, as well as plan for

potential solutions to increase confidence and uptake.

• Identify community leaders, trusted messengers, and other

important channels to reach populations of focus.

• Identify areas of intervention and prioritize potential

intervention strategies to increase confidence in and

uptake of COVID-19 vaccine.

How to Use

The RCA consists of five steps:

1. Identifying objectives and community(ies) of focus

2. Planning for the assessment

3. Collecting and analyzing data

4. Reporting findings and identifying solutions

5. Evaluating your efforts

Given the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, the suggested

timeframe to complete the assessment is three weeks. The

RCA guide provides a step-by-step process for the assessment

as well as tools and scripts. The guide is available in English

and Spanish.

Applying the Data

The data collected through the RCA will increase your

understanding of what communities are thinking about COVID-19 vaccines, and help you plan

potential solutions to increase vaccine confidence and uptake. The data can also reveal previously

unrecognized leaders and trusted messengers through whom you can reach community members.

13

Vaccine Confidence

and Uptake Strategies

Below are selected strategies to increase

vaccine confidence and uptake drawn from

historical vaccination efforts and supported

by positive outcomes from evaluation

research. Examples from communities

currently using the strategies to increase

COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake

are included.

State and local health departments,

community- and faith-based organizations,

and local nonprofits are encouraged to try a

combination of these strategies to increase

vaccination rates.

Links to learn more about

how communities have

addressed challenges and

implemented the strategies

are included in Appendix A.

Vaccine

Ambassadors

Medical

Provider Vaccine

Standardization

Medical

Reminders

Motivational

Interviewing

Financial

Incentives

School-Located

Vaccination

Programs

Home-Delivered

Vaccination

Workplace

Vaccination

Vaccination

Requirements

Effective Messages

Delivered by Trusted

Messengers

Provider

Recommendation

Combating

Misinformation

14

Strategy 1

Vaccine Ambassadors

Vaccine ambassadors are a derivative of the lay health advisor (LHA)

model, which trains community members to disseminate important

health information in their communities. Ambassadors are most

effective when they are trusted community members and share

similar beliefs and characteristics with their peers.

Barriers Addressed: Equity, access, prevailing social norms, mistrust,

misinformation, cultural relevance.

Research Base: Framing vaccine uptake as a prevailing social norm

has a positive impact. A survey study showed that when people

think that most people around them want to be vaccinated, they are

more likely to be vaccinated as well. Discussing with peers the risk

of contracting disease and the decision to vaccinate impacts one’s

decision. Endorsements from peers in one’s own social network can

also help spread credible information about the vaccines.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: San Francisco, CA

Population of Focus: Latino Persons

The “Motivate, Vaccinate, and Activate” campaign

encouraged residents of the under-resourced,

predominantly Latinx Mission District of San Francisco,

California, to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The culturally

tailored initiative was organized through a community-

academic-city public health partnership among Unidos en

Salud (United in Health), the University of San Francisco, and

the City of San Francisco. They engaged trusted messengers,

social networks, and used a convenient vaccination site

to increase vaccination uptake and overcome hesitancy

due to misinformation, distrust of institutions, and access

to the vaccines. Community health workers educated the

community about the vaccines, texted people to let them

know of their eligibility, and used public media to spread

the word about vaccination locations.

Vaccinated community members became ambassadors

to recruit friends and family members to get vaccinated.

Important steps in this strategy included:

15

Combating

Misinformation

Vaccination

Requirements

School-Located

Vaccination

Programs

Medical

Reminders

• Two dedicated staff shared their personal experiences

modeling how this could be done.

• Staff then encouraged others to share their own

vaccination experiences with their unvaccinated friends

and family to encourage them to become vaccinated.

• Staff provided tips on how to handle difficult

conversations, provided myth-busting information,

and role played.

Outcome: Of those who were fully vaccinated, 91% of

survey respondents reported that they later recommended

vaccination to one or more unvaccinated people they

knew; 83% stated that they motivated one or more others

to be vaccinated; and 19% reported that they motivated

six or more others. During a 16-week period, the campaign

administered 20,792 vaccines at the neighborhood site.

Where to Start: Learn more about how the community implemented this strategy to use social

networks to boost vaccination coverage.

16

Location: Philadelphia, PA

Population of Focus: African American or Black Adults

A partnership between two health systems and community leaders in Philadelphia established COVID-19

vaccination clinics to overcome equity barriers among communities of color. Faith and other community

leaders were engaged as vaccine ambassadors who helped design the intervention, activated their

networks, and were trusted messengers to increase vaccinations. The strategy used other components

in addition to the vaccine ambassadors including a no- to low-tech approach to vaccine scheduling,

text or phone reminders of future vaccine appointments, and personal outreach.

Outcome: The program was designed and launched with just 2 weeks of planning. Three 7-hour clinics

vaccinated 2,821 people, 85% of whom were Black. Second dose clinics operated with an overall 0.6%

no-show rate.

Key components of this effort included:

• Health system leaders met virtually with area pastors to ensure they felt comfortable recommending

the COVID-19 vaccines.

• The pastors led by example and received their first doses at the clinic.

• During a virtual event held by two faith leaders for their congregations, Black physicians shared

their vaccination stories, provided scientific information about the vaccines, and answered

people’s questions and concerns. The event was recorded for future use by new partners, including

community organizations and health workers, senior centers, salons and barbershops with

predominantly African American or Black customers and staff, as well as WURD, a Black-owned

and operated talk radio station that aired segments about the COVID-19 vaccines and the

community clinic initiative.

Where to Start: Learn how this effort was implemented in Philadelphia including details on all the

components and lessons learned.

17

Strategy 2

Medical Provider

Vaccine Standardization

Medical provider vaccine standardization refers to offering

vaccination as a default option during patient visits and

integrating vaccination into medical practice procedures.

Barriers Addressed: Policy, mistrust, health literacy

Research Base: Medical practices and hospitals can take steps

to increase vaccine uptake through standard practice measures,

including default scheduling and presumptive announcements. In one

study, scheduling patients by default increased u vaccination by 10

percentage points. Another study showed patients with standing orders

received u and pneumococcal vaccines signicantly more often than

those with reminders. For patients with standing orders, the hospital’s

computerized system identied eligible patients and automatically

produced vaccine orders directed to nurses at the time of discharge.

Even standardizing what the doctor says when entering the room can

impact vaccine uptake. Doctors trained to announce human papilloma

virus (HPV) vaccines during visits with a brief statement that assumed

parents were ready to vaccinate (the presumptive approach) increased

uptake by 5.4% over the approach of engaging parents in open-ended

conversations about vaccinating their child.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: Arizona

Population of Focus: Adults

In Arizona, a local 10-physician practice received detailed

guidance from their county health department that helped

them obtain vaccine supply and establish a protocol for

administration. The county health department provided

both supplies and instructional webinars on a weekly

basis to guide practices through the process of becoming

vaccinators. The Arizona physician office trained their staff

to provide accurate information to patients who call with

questions and developed a new scheduling system to

standardize outreach and scheduling for eligible patients.

Because their office space was too small to monitor patients

for post-vaccine allergic reactions during normal business

hours, they organized special weekend vaccination clinic

hours. Yet, the groundwork has been laid for integrating

vaccination into routine practice.

Standardization measures could become routine

practice. Currently, many primary care and specialty

physician offices are not offering COVID-19 vaccines.

That is expected to change as logistical barriers are

overcome and more physician practices become

involved in the “last mile” effort to vaccinate everyone

eligible, particularly in states where state and local

health departments provide support. As the vaccines

become more available in medical practices and

hospitals, standardizing COVID-19 vaccination into

routine practice will help reduce missed opportunities

for vaccination, which are encounters during which a

person eligible for a vaccine receives health services

that do not result in them getting vaccinated.

Where to Start: The Arizona Department of Health

Services Immunization Program in partnership with

The Arizona Partnership for Immunization, a non-

profit coalition, has a free training series to improve

vaccination practices in providers’ offices. Trainings

cover areas including vaccine friendly office practices,

vaccine handling and storage, shot administration.

18

Strategy 3

Medic al Reminders

Medical reminders are messages sent to patients to remind them

of recommended or upcoming treatment. Messages can be sent by

autodialed phone calls, text messages, or post-cards, for example.

Barriers Addressed: Equity, access, forgetfulness, friction, health literacy,

lack of adequate information

Research Base: Reminders of upcoming vaccination appointments can

increase vaccination rates. This intervention is often part of a multi-pronged

approach combined with removing access barriers to optimize uptake. Duval

County Health Department in Florida successfully increased vaccination

rates by using data from the Florida Shots Registry to identify families with

upcoming vaccinations due or who were behind on their child’s vaccinations

and sending them reminders and educational materials through phone calls,

letters, and home visits.

A study in Rochester, New York, showed that when interventions were

combined to include patient reminders, provider reminders, and telephone

outreach, older adults in the intervention group were up to six times as likely

to be vaccinated against u.

A University of Pennsylvania study found that simple reminder text messages

sent to 47,306 patients in two health systems increased u vaccinations by

around 5%. Of the 19 dierent messages tested, those most likely to “nudge”

patients to be vaccinated were presented in a professional format and

tone—not casual, surprising, or interactive. The most successful messages

reminded patients twice to get their shot at their upcoming doctor’s

appointment and stated that a vaccine was already reserved for them.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: Multiple U.S. Locations

Population of Focus: Adults

Several state and local health departments, including in

Michigan, Oklahoma, and Baltimore, Maryland, are using

text messages to:

• Help people schedule their vaccine appointments

• Provide education and vaccination site information

• Gauge views on vaccination

Certain populations can be reached with messaging,

either based on race, ethnicity, or age, or used in geogr

aphic

locations with lower vaccination uptake. In most cases, texts

are provided in English and Spanish, but health departments

or other entities sending texts can translate and customize

to any language spoken in their community of focus.

This can also be used to remind people of their second

vaccination appointment, if applicable.

Many text-based services are available. Some, like

CareMessage, offer a free model for nonprofits to help

with COVID-19 vaccination. CDC recommends that

providers without a text-message system offer their

19

patients the COVID-19 text reminder service, VaxText℠, which is free to providers and patients.

After enrolling in VaxText℠, people who have received the first COVID-19 vaccine dose receive

weekly text reminders in English or Spanish about their second dose or a reminder that they are

overdue, if applicable.

Well-crafted emails containing behavioral nudges can also be used as reminders to get vaccinated.

A large Pennsylvania health system found that after a five-week effort to have employees

vaccinated against COVID-19, 41% still had not scheduled their vaccination. They found through

a study that individually addressed emails containing behaviorally informed messages increased

vaccination registration.

The emails had three important components:

• Told the healthcare worker that vaccines would soon be available more broadly, thus, reducing

employees’ access and emphasizing scarcity.

• Contained a message either about social norms, saying that many fellow employees had already

chosen to be vaccinated; or about risks, comparing the risk of vaccination with the risk of COVID-19.

• Asked employees to make an active choice by clicking through to schedule their vaccination

appointment.

Where to Start: Learn the details on how this reminder effort was implemented.

20

Strategy 4

Motivational

Interviewing

Motivational interviewing refers to patient-centered conversations

designed to increase patient motivation and likelihood of health

behavior uptake.

Barriers Addressed: Misperception, health literacy, uncertainty

Research Base: Motivational interviewing aims to support decision

making by strengthening a person’s intention to vaccinate based

on their own arguments. The healthcare professional informs about

vaccination in alignment with the individual’s specic informational

needs and with respect for their beliefs. Motivational interviewing has

been shown to decrease parental vaccine hesitancy. A pilot study of

using motivational interviewing in maternity wards during postpartum

stays found the strategy led to a 15% increase in mothers’ intention to

get their child vaccinated, a 7% increase in infants’ vaccination coverage

at seven months, and a 9% greater chance of complete vaccination

at 2 years. Motivational interviewing was also found to signicantly

improve HPV vaccination completion among adolescent patients in a

study that employed an intervention of using a presumptive vaccine

recommendation with motivational interviewing follow up for parents

who remained resistant. Some healthcare providers have concerns that

this approach takes too long and that such a conversation is not billable.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: Western Pennsylvania

Population of Focus: Adults

Motivational interviewing can be a strategy to promote

COVID-19 vaccine uptake. A demonstration project in the

Pittsburgh area showed that innovative notification and

motivational interviewing strategies at a regional chain

supermarket pharmacy increased the number of herpes

zoster, flu, pertussis, and pneumococcal vaccines given to

adults. Community pharmacies are accessible and able to

provide COVID-19 vaccinations to many customers, along

with their other patient-centered products and services

and may be able to model programs similar to this.

Pharmacy staff identified the patient, who then received

an automated notification about their vaccination status.

The staff used motivational interviewing techniques face-

to-face or by telephone to engage patients in conversation

about getting vaccinated.

Outcome: The 99 pharmacies in western Pennsylvania that

took part in the project saw a 33% increase in vaccinations

over the prior year: 45% for flu, 31% for pertussis, and

7% for pneumococcal vaccinations, while herpes zoster

vaccinations dropped by 5%.

Where to Start: Scripts for using motivational interviewing with those who may be COVID-19 vaccine

hesitant are available.

21

Strategy 5

Financial Incentives

Financial incentives aim to motivate people to participate in a health

behavior by providing a tangible reward, or a chance at a tangible

reward, for completion of the behavior.

Barriers Addressed: Inertia

Research Base: While evidence supporting the use of incentives to increase

vaccine uptake is overall limited, the type that appears eective is of a

guaranteed gift incentive. For example, oering a $30 incentive increased

vaccination rates at college campus clinics according to one study. Recent

studies of the Ohio COVID-19 vaccine lottery have been less positive,

showing the likelihood that the approach has not increased vaccine uptake.

Clearly, these are two dierent approaches—one is a guaranteed gift and the

other a chance at winning. Also, the audiences dier with the rst comprised

of young adult college students and the latter a general population.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: Multiple U.S. Locations

Population of Focus: Adults and Youth

• West Virginia state government is offering residents

ages 16 to 35 who have been vaccinated a choice of

receiving either a $100 savings bond or a $100 gift card.

The governor estimates this might cost the state up to

$20 million.

• California offered $50 in the form of a virtual Mastercard

or grocery gift card to residents who started their

vaccination series between May 27 and July 18. The

money is limited to the first 2 million requests, which

limits the total cost to the state.

• Employers are also offering cash incentives to their staff.

Maryland state employees will receive $100 and the

Colorado Department of Corrections will provide $500

to staff who elect to get vaccinated.

• Many large private corporations are also providing cash

incentives to employees, often ranging from $75 to

$500 including Amazon, Kroger, PetCo, AutoZone, and

Bolthouse Farms.

• Many businesses are offering free products to those who

have been vaccinated, including the well-publicized

free Krispy Kreme donut. Several states are offering

free admission to state parks or similar incentives for

vaccinated visitors. Offers like these non-monetary

guaranteed incentives have not been well-studied for

effectiveness.

Where to Start: The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) provides

guidance to employers on offering incentives to employees for becoming vaccinated.

For ideas on incentives to offer, see the list of state and local government incentives

maintained by the National Governors Association.

22

Strategy 6

School-Located

Vaccination Programs

School-located vaccination programs are events held at a school

campus to remove logistical barriers and increase vaccine uptake.

These can be open to students only, or offered to faculty, families,

and the greater community as well.

Barriers Addressed: Access, friction, prevailing social norms,

uncertainty, lack of adequate information

Research Base: Voluntary school-located vaccination programs have

demonstrated high coverage, though they are not without challenges.

One of the major challenges is obtaining informed parental consent

when needed. School-located programs can be eective even with

“controversial” vaccinations such as for HPV. The setting also has been

shown to yield higher completion rates of multi-dose vaccine series as

compared to community health center settings.

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: St. Louis County, Missouri

Population of Focus: School-age Youth

School districts of many sizes across the country are holding

COVID-19 vaccination events. One of the first school districts

to do so was the Parkway School District in St. Louis County,

Missouri, which held their event on April 26, 2021. The event

was held in partnership with a local pharmacy. In a survey,

350 parents said they were interested, and the 204 students

who were vaccinated at the event represented about 5% of

eligible students in the district.

Timing of the event may have affected turnout because

some expressed concern about the second dose occurring

during the week of finals for some students, according to

the Interim Health Services Director who led the effort. The

director also noted that school nurses are trusted sources of

health information and play an important role in educating

students and families about the COVID-19 vaccines. Two

additional vaccination clinics have been held, one just days

after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the

Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for those 12 years and older.

While this strategy has focused on vaccinating students

through school-located vaccination programs, school

settings may also be ideal locations for community

vaccination events. Much for the same reason schools are

often used as voting locations, they generally are easily

accessible, have ample parking, have both indoor and

outdoor spaces available, and are familiar places.

Outcome: So far, Parkway School District has vaccinated

nearly 3,000 students through their three on-site clinic

events. This was made possible, in part, due to their

excellent relationship with a local pharmacy, which

will pave the way for possible future student vaccination

events should a vaccine be approved for younger

school-age children.

Where to Start: The school district documented their

lessons learned as guidance for other school districts

noting the importance of details such as:

• Ensuring Ample Parking

• Working Around Educational Schedules

• Obtaining Consent

• Training Staff

• Managing Vaccine Delivery and Storage

23

Strategy 7

Home-Delivered

Vaccination

Home-delivered vaccination efforts reach populations where

they are; traditionally used when barriers to transportation

and access exist.

Barriers Addressed: Equity, access, inertia, friction

Research Base: Bringing vaccines to where people are, including

in their homes, is an eective means to reach several hard-to-reach

populations. This strategy can be applied to people who are bound to

their homes as well as to neighborhoods with low vaccination rates.

In an eective eort in New York City, individuals canvassed specic

communities to educate people about the u vaccine and oered

it to people on the spot. They focused on those with substance use

disorders, immigrant populations, older adults, sex workers, and

people experiencing homelessness. Both appointment-based home

delivery and canvassing methods may be eective ways to deliver

COVID-19 vaccines.

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: Multnomah County, Oregon

Population of Focus: Adults

As the COVID-19 vaccination effort progresses, shifts are occurring from mass vaccination sites to

smaller neighborhood and community clinics, and now to home-based efforts to do everything

possible to give all individuals the opportunity to get vaccinated. The Emergency Operations Center in

Multnomah County, Oregon, has partnered with the Public Health Division and County Human Services

to provide COVID-19 vaccinations through a mobile program reaching people where they live. Initially

vaccinating those in adult care homes, they have expanded the project’s scope to include other adults

who are homebound.

The county’s mobile door-to-door COVID-19 response team pairs Medical Reserve Corps volunteers,

who are licensed medical practitioners, and other volunteers to assist in providing COVID-19

vaccinations to people in their homes. The goal of the response, launched in February 2021, is to

vaccinate up to 5,000 people. “Getting to meet people ‘where they are at’ and administering a life-

saving vaccine is an incredibly powerful experience. It truly brought people hope. The coordination

it takes to make this kind of outreach happen is no small feat – but it’s precisely the kind of work we

need to do in order to respond quickly to inequalities and gaps in vaccine distribution, especially for

those who are most vulnerable,” said Dr. Sharon Meieran, a Medical Reserve Corps volunteer.

Where to Start: CDC provides guidance for implementing home-bound and residential living

COVID-19 vaccination including consideration for training requirements, planning, storage and

handling, and administration.

Strategy 8

Workplace

Vaccination Programs

24

A vaccination event held on-site at a workplace to remove logistical barriers and create norms.

This can be open to emplo

yees only or extended to family members or the greater community.

Barriers Addressed: Access, cost, prevailing social norms, friction

Research Base: Numerous studies have shown that vaccination programs at the worksite can increase

vaccination rates among workers and their families. In one study, where u vaccination rates increased

signicantly after the intervention, 90% of vaccinated employees received a vaccine at employer-sponsored

events. The most important reasons employees reported for being vaccinated at work were not related to

health, but that the vaccine was free, convenient, and would help them avoid being absent from work.

There is evidence on-the-job COVID-19 vaccines may have similar uptake success. A recent Kaiser Family

Foundation study found that 23% of Americans would be more likely to get a vaccine if it was available

at their workplace. Another recent survey of employees by McKinsey & Company found an even greater

potential return with 83% of those surveyed saying oering on-site vaccinations would signicantly (49%)

or moderately (34%) increase the likelihood that they would get a COVID-19 vaccine. According to a 2020

Gallup poll, small businesses are one of the most trusted institutions in the U.S.

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: Midwest; Jackson, Mississippi

Population of Focus: Adults

Tyson Foods is offering on-site vaccination at many of their

facilities. In Iowa and Illinois, the company partnered with

the Midwest grocery chain Hy-Vee and state and local public

health departments to vaccinate food processing workers

at four locations in the two states. Workers in that industry

have been hit hard by COVID-19 and were extremely excited

for the opportunity. The workers are diverse, with one

facility requiring vaccine education information translation

in 18 languages. Tyson Foods also offered workers up to four

hours of regular pay if they needed to get their vaccine(s)

outside of a normal shift or away from the jobsite.

Outcome: By early March 2021, Hy-Vee staff had vaccinated

over 2,400 employees in one of the states.

Small businesses can also support on-site vaccination

efforts. In Jackson, Mississippi, the Broad Street Baking

Company partnered with the Mississippi State Department

of Health and the G.A. Carmichael Family Health Center to

hold mobile vaccination events in a parking lot near the

restaurant in April and June 2021.

Outcome: At both events, vaccines were given to all

employees and other attendees who requested them.

Where to Start: CDC offers guidance to state, tribal, and local jurisdictions on reaching out to worker

populations to increase vaccine uptake. This includes how to talk with small businesses and special

considerations for rural communities and migratory workers. CDC also has information for employers

on how they can support vaccination of their workforce.

Strategy 9

Vaccination

Requirements

Vaccination requirements are policies that require employees, students,

or patrons to be vaccinated and provide proof of vaccination in order to

be in compliance.

Barriers Addressed: Policy, inertia, prevailing social norms, politicization

Research Base: Vaccine requirements at the organizational level may be an

eective way to increase vaccination rates and decrease disease incidence.

Requirements by employers or schools ask that employees or students provide

proper documentation of vaccination to comply with the organization’s

vaccination policy. Exemptions can be oered for specic circumstances,

such as medical and religious reasons. Vaccination requirements have not often

been used for adult populations, with the exception of military requirements

and for healthcare workers to receive u shots. There is evidence showing

school mandates positively impact uptake for routine childhood vaccines

and some studies suggest that vaccination for children and workers, including

mandatory vaccination, decreases absenteeism.

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: Multiple U.S. Locations

Population of Focus: Adults

Many employers and institutes of higher education such as universities

are requiring staff and students to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Large

companies have most recently required staff to be vaccinated to return

to the office. A number of federal, state and local governments are also

requiring vaccination for employees; some with an alternate option for

weekly testing for COVID-19 and some without that option. Examples of

early adopters of vaccination requirements are provided below.

Houston Methodist Health System: Houston Methodist was the first health

system in the country to mandate COVID-19 vaccination for all employees

to protect their patients and workforce. The health system is made up of an

academic medical center and six community hospitals employing over 26,000

people. The first phase of the policy included managers and new hires and

was gradually rolled out to all staff. Those not in compliance received a two-

week suspension during which they could get vaccinated. Several employees

pushed back on the requirement and took the hospital system to federal court.

The Texas court dismissed the lawsuit and upheld the vaccine requirement

stating that the requirement does not break any laws and is in line with

public policy.

Outcome: Houston Methodist achieved nearly 100% compliance with 24,947

workers being vaccinated. Medical and religious exemptions were granted to

over 600 employees and only 153 employees out of 26,000 (.5%) resigned or

were fired for not complying.

25

Morgan Stanley Office Vaccine Policy: Morgan Stanley created a policy requiring all employees returning

to their offices to be vaccinated. It also extends to clients and visitors to their two New York offices. The

company views this policy as a way to create a safe and normal office environment that allows employees

to forgo masks and social distancing. Employees who remain unvaccinated have the option of working

from home, but the company is strongly encouraging employees to come back into the office.

Where to Start: The policy and procedures Houston Methodist put in place is publicly available and can

be used as a model for other employers wanting to require COVID-19 vaccines. Other legal organizations

also have templates available online as found in Appendix A.

26

27

Strategy 10

Effective Messages

Delivered by Trusted Messengers

Effective messages are messages that have undergone testing with

the intended population and were shown to produce the desired

outcome. Trusted messengers are people seen as credible sources

of information by specific populations. Trusted messengers can be

trained to be vaccine ambassadors (see Strategy 1) and may include

experts.

Barriers Addressed: Mistrust, health literacy, misinformation, lack

of adequate information

Research Base: The messengers and messages used to convey

information about vaccines are important to improving vaccine

condence.

The COVID-19 States Project Report evaluates results from two

experiments designed to test eective communication strategies for

increasing COVID-19 vaccine condence and intent. The rst experiment

tested ve messages and a control message for the eect it had on

participants’ willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. The messages

involved themes of patriotism, harm reduction, social norms, scientist

recommendation, and physician recommendation. The study found

that messages involving a personal physician or a scientist

recommending vaccination were the most compelling. The second

experiment looked at messenger eectiveness and found that messages

delivered by politicians increased resistance to vaccination while

those delivered by physicians or scientists showed increased vaccine

condence and intent.

Messages and messengers should be continually evaluated

for eectiveness and tested across populations with dierent

demographics. Continued evaluation of messages allows

communication campaigns to tailor messages to specic concerns

and demographic populations, which is shown to be more eective

than generalized messaging.

28

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: Multiple U.S. Locations

Population of Focus: Adults

The Black Coalition Against COVID, The Kaiser Family Foundation, and Esperanza Hope for All created

a COVID-19 vaccine communications campaign called “The Conversation,” which uses the hashtag

#BetweenUsAboutUs. The campaign features 50 videos of Black and Latino doctors, nurses, and scientists

talking about vaccine facts and dispelling misinformation. In addition to the videos, the campaign oers

graphics, print media, social media content, and TV and radio PSAs. The content is free for educational

use and communities and organizations are invited to download and utilize their materials in English and

Spanish. Some content features doctors sharing why they got vaccinated. One graphic shows a female

Black doctor with the quote, “When we get enough people vaccinated, we’re going to see the death rates

go down. Then we’re going to see the hospitalization rates go down.” Currently, the campaign’s videos have

over 21,000,000 views on YouTube.

Where to Start: For specific messaging language tips based on COVID-19 messaging research, see the

deBeaumont Foundation’s Tip Sheet.

Strategy 11

Provider

Recommendation

Provider recommendation refers to healthcare professionals

suggesting that a patient receive a COVID-19 vaccination.

Barriers Addressed: Inertia, friction, mistrust, uncertainty,

mis- and disinformation, lack of adequate information

Research Base: Provider recommendations have strong support for increasing

vaccination. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices includes

this strategy in their recommendations for improving vaccination rates.

Some people may have more trust in their own doctor than in the medical

community in general. Research on vaccinations in pregnant people found

that provider recommendation shows increases in vaccination rates and when

coupled with oering the vaccination during doctor’s oce visits, doubles

the likelihood of uptake. In a study of u vaccination in adults, patients who

received provider recommendations with an oer of vaccination were 1.76

times more likely than those who did not receive a recommendation to be

vaccinated. Those receiving only a recommendation were 1.72 times more

likely than those who did not receive a recommendation to be vaccinated.

The HPV vaccine, which relies on healthcare professionals for distribution,

depends on provider recommendations for adequate coverage. A study

on low HPV vaccination rates in North Carolina, found that lack of provider

recommendations contributed to under vaccination in the population.

COVID-19 Application Example

Location: New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Population of Focus: Adults

The New York City Department of Health and Mental

Hygiene created a resource called Vaccine Talks that

emphasizes the importance of healthcare professional

recommendations in increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates.

Vaccine Talks offers resources for healthcare providers and

their staff to recommend and offer COVID-19 vaccination

at multiple points of interaction with patients. The health

commissioner released a statement promoting Vaccine

Talks that places emphasis on the trust patients have

in their healthcare providers and says that their strong

recommendations for COVID-19 vaccines will help drive

vaccination rates in the city.

Vaccine Talks includes a resource called the “Use Every

Opportunity” tool instructing healthcare offices on how

to integrate COVID-19 vaccine education and offers into

all healthcare settings. Vaccine Talks also includes a link

to a form the provider can complete to request that the

public health system contact the patient to schedule their

vaccination at a clinic or in their home if needed.

29

Emergency departments and urgent care facilities are

important locations for COVID-19 vaccine provider

recommendations due to the high number of patients seeking

routine care in these settings. The Philadelphia Department

of Public Health put out a call to emergency facilities in the

city to begin recommending and administering COVID-19

vaccines to patients upon discharge. The notice focused on

postpartum discharges and patients being discharged to

long-term care facilities as key demographics for provider

recommendations and offers. They provided best practices

for vaccination during patient discharge.

Where to Start: The Vaccine Talks resources include

scripts for physicians to talk to their patients about

COVID-19 vaccines, including talking to parents of

eligible children, and other tools for physicians

to support vaccine confidence building with staff

and patients.

30

Strategy 12

Combating

Misinformation

Tactics used to address and dismantle misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation refers to the

sharing of false information and disinformation refers to information that is deliberately misleading and

intended to manipulate a narrative.

Barriers Addressed: Misperception, mis- and disinformation, lack of adequate information

Research Base: Believing incorrect information can act as a barrier to vaccine uptake. Vaccine myths are

particularly dicult to combat, in part because people tend to believe information that is in line with their

existing attitudes and worldview. Fact-checking and debunking appear to be eective tools to counteract

the eects of misinformation, particularly when the correct information sources are universities and health

institutions. Debunking incorrect information with messages that reect the worldview and arm the values

of the intended audience may be the most successful approach. Debunking misinformation is challenging.

Misinformation is often simple and more cognitively attractive than fact, and refuting a falsehood often

requires repeating it, which reinforces the falsehood in the believer. Techniques that help dispel falsehoods

include warning the audience upfront that misleading information is coming, using fewer arguments to

refute the myth, and keeping the factual statements simple.

Everyday social media users can play an important part in correcting misinformation. While the person

originally expressing the misinformation may not be moved because the correction does not align with

their world view, others see the correct information and are impacted by it. Responding with empathy

and providing facts, rather than simply saying something is wrong, are tips for eective corrections.

COVID-19 Application Examples

Location: Multiple U.S. Locations

Population of Focus: Adults

Public Good Projects (PGP) is a public health non-profit

organization with a mission to stop the spread of vaccine

misinformation through evidence-based media monitoring,

behavioral interventions, and cross-sector initiatives. In

the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, PGP created a

misinformation tracking system to monitor misinformation

being shared about COVID-19 and later about the vaccines.

Using this tracking system, PGP pinpointed ideas that could

pose a threat to public health measures and worked with

scientists to create evidence-based responses. To combat

the misinformation, PGP identifies micro-influencers with

audiences who have high rates of vaccine hesitancy and

equips them with science-backed messages to share with

their social networks. Their vaccine-hesitant followers are

more likely to accept this information when it comes from

someone they trust rather than from a health expert.

Where to Start: Dissemination of factual and

easy to understand information comba

ts mis- and

disinformation. This can be done in a variety of

ways including identifying and training social media

micro-influencers in your community as PGP is doing

nationally or using your own social media to promote

accurate information. To keep your finger on the pulse

of social media misinformation nationally you can

refer to the Virality Project’s weekly briefing. To

monitor your local social media, you can utilize

the RCA’s Social Listening and Monitoring Tool.

31

Conclusion

Reaching universal COVID-19 vaccination coverage

in the United States is a monumental challenge.

There are barriers impeding both vaccine confidence

and uptake. Structural barriers, such as time costs

and transportation, lead to inequitable vaccine

distribution, often negatively affecting populations

that have been disproportionately affected by the

pandemic. People’s behaviors and beliefs, often

based on misinformation or low health literacy,

can obstruct their willingness to get vaccinated,

while other human nature factors make it difficult

to motivate people to do something difficult, new,

or unfamiliar. COVID-19 vaccination and pandemic-

related information can be perceived as complex and

sometimes contradictory, adding yet another barrier.

Compounding all of this is the current politicization

of getting vaccinated.

Understanding the specific barriers your community

of focus faces will help you identify and initiate

activities that will help overcome those barriers.

Tools, including the SVI, WAM Exercise, and the

diagnostic tool, can help to identify populations

disproportionately affected by the pandemic and

the barriers and facilitators to vaccination they face.

The RCA Guide offers in-depth resources to help you

quickly learn more about needs related to COVID-19

vaccination in your community of focus.

While the COVID-19 vaccination effort is unique

in many ways, applying best practices and lessons

learned from previous vaccination efforts increases

the likelihood of overcoming vaccine hesitancy and

improving vaccine uptake. There is no magic formula

to addressing vaccination barriers—communities

need to employ multiple tailored strategies and

tactics. The examples offered in this guide can serve

as inspiration as well as practical guidance. Each

community will need to customize its approaches to

harness available resources to meet local needs.

32

Appendix A

References and Resources

To learn more about each of the strategies discussed in this guide, the research supporting them,

and information on how to implement them in your community, see the resources below.

Common Barriers

The Behavioral and Social Drivers (BeSD) of COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake

The Behavioral and Social Driver (BeSD) expert working group.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1529100618760521

Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J., & Kempe, A. (2017). Increasing vaccination:

Putting psychological science into action. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18(3), 149-207.

Understanding Your Community

Social Vulnerability Index

The CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index (CDC/ATSDR SVI) uses 15 U.S. census variables to help local

officials identify communities that may need support before, during, or after disasters.

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

SVI data is displayed on an interactive map.

https://svi.cdc.gov/map.html

RCA Guide and Tools

COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence Rapid Community Assessment Guide and tools.

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/vaccinate-with-confidence/rca-guide/index.html

Vaccine Confidence and Uptake Strategies

Strategy 1: Vaccine Ambassadors

Research Base

The influence of social norms on flu vaccination among African American and White adults.

https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyx070

Quinn, S. C., Hilyard, K. M., Jamison, A. M., An, J., Hancock, G. R., Musa, D., & Freimuth, V. S. (2017). The

influence of social norms on flu vaccination among African American and White adults. Health education

research, 32(6), 473-486.

Attention, intentions, and follow-through in preventive health behavior: Field experimental evidence on flu

vaccination.

https://www.swarthmore.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/user_profiles/ebronch1/JEBO_2015.pdf

Bronchetti, E. T., Huffman, D. B., & Magenheim, E. (2015). Attention, intentions, and follow-through in

preventive health behavior: Field experimental evidence on flu vaccination. Journal of Economic Behavior &

Organization, 116, 270-291.

More Information About the COVID-19 Examples

A multi-component, community-based strategy to facilitate COVID-19 vaccine uptake among

Latinx populations: from theory to practice

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.07.21258230v1.full.pdf

Marquez, C., Kerkhoff, A. D., Naso, J., Contreras, M. G., Castellanos, E., Rojas, S., ... & Havlir, D. V. (2021).

A multi-component, community-based strategy to facilitate COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Latinx

populations: from theory to practice. MedRxiv.

33

Operationalizing Equity: A rapid-cycle innovation approach to COVID-19 vaccination in Black neighborhoods.

https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0094

Lee, K. C., Al-Ramahi, N., Hahn, LO., Donnell, T., Schonewolf, L. J., Khan, N., O’Malley, C., Ghatri, U. G.,

Pearlman, E., Balachandran, M., et al. (April 7, 2021). Operationalizing Equity: A rapid-cycle innovation

approach to COVID-19

vaccination in Black neighborhoods. NEJM Catalyst.

Additional Resources for Implementing this Strategy

San Francisco Department of Public Health’s community COVID-19 vaccine communication training for

ambassadors slide presentation.

https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/ig/vaccine/vaccine-ambassador-training-pdf.pdf

Strategy 2: Medical Provider Vaccine Standardization

Research Base

Default clinic appointments promote influenza vaccination uptake without a displacement effect.

https://behavioralpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/chapman-web.pdf

Chapman, G. B., Li, M., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2016). Default clinic appointments promote

influenza vaccination uptake without a displacement effect. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(2), 40-50.

Inpatient computer-based standing orders vs physician reminders to increase influenza and pneumococcal

vaccination rates: a randomized trial.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/199810

Dexter, P. R., Perkins, S. M., Maharry, K. S., Jones, K., & McDonald, C. J. (2004). Inpatient computer-based

standing orders vs physician reminders to increase influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates: a

randomized trial. Jama, 292(19), 2366-2371.

Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial.

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/139/1/e20161764.full.pdf

Brewer, N. T., Hall, M. E., Malo, T. L., Gilkey, M. B., Quinn, B., & Lathren, C. (2017). Announcements versus

conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 139(1).

More Information About the COVID-19 Examples

The Room Where It Happens: Primary Care and COVID-19 Vaccinations.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/jul/room-where-it-happens

Klein, S., Hostetter, M. (7 July 2021). The Room Where It Happens: The role of primary care in the next

phase of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. The Commonwealth Fund.

The Arizona Department of Health Services Immunization Program in partnership with TAPI, a non-profit

coalition, has a free training series to improve vaccination practices in providers’ offices. Trainings cover areas

including setting up vaccine friendly office practices, vaccine handling and storage, shot administration.

https://whyimmunize.org/covid-19-vaccine-t-i-p-s/

Additional Resources for Implementing this Strategy

The Community Guide: Vaccination: Provider Reminders

The Community Guide: Vaccination: Standing Orders

Standing orders templates for administering vaccines

https://www.immunize.org/standing-orders/

CDC COVID-19 Vaccination Program Provider Requirements and Support

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/vaccination-provider-support.html

Appendix A

34

Appendix A

The COVID-19 Vaccine Use Every Opportunity implementation tool provides strategies for ensuring COVID-19

vaccination is offered to every eligible patient during their encounters with your organization. The Use Every

Opportunity framework is an adaptable tool for implementing workflows to achieve the highest level of

COVID-19 vaccine coverage possible in all health care settings.

https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/covid/providers/covid-19-vaccine-use-every-

opportunity-tool.pdf

Strategy 3: Medical Reminders

Research Base

The Community Guide in Action - A Good Shot: Reaching Immunization Targets for two-year-old’s in Duval

County, Florida.

https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccinations-FL_0.pdf

Increasing inner-city adult influenza vaccination rates: a randomized controlled trial.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3113429/pdf/phr126s20039.pdf

Humiston, S. G., Bennett, N. M., Long, C., Eberly, S., Arvelo, L., Stankaitis, J., & Szilagyi, P. G. (2011).

Increasing inner-city adult influenza vaccination rates: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health

Reports, 126(2_suppl), 39-47.

A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s

appointment.

https://www.pnas.org/content/118/20/e2101165118

Milkman, K. L., Patel, M. S., Gandhi, L., Graci, H. N., Gromet, D. M., Ho, H., ... & Duckworth, A. L. (2021).

A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s

appointment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(20).

More Information about the COVID-19 Examples

Pennsylvania health system email reminders

Santos HC, Goren A, Chabris CF, Meyer MN. Effect of Targeted Behavioral Science Messages on COVID-19

Vaccination Registration Among Employees of a Large Health System: A Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw

Open. 2021;4(7):e2118702. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18702

Additional Resources for Implementing this Strategy

VaxText is a free text messaging platform that providers can offer to their patients. Patients can opt in to

conveniently receive text message reminders to get their second dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/reporting/vaxtext/index.html

Strategy 4: Motivational Interviewing

Research Base

Motivational interviewing: A promising tool to address vaccine hesitancy.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32281992/

Gagneur, A., Gosselin, V., & Dubé, È. (2018). Motivational interviewing: A promising tool to address vaccine

hesitancy. Vaccine, 36(44), 6553-6555.

Effects of a Health Care Professional Communication Training Intervention on Adolescent Human

Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5875329/

Dempsey, A. F., Pyrznawoski, J., Lockhart, S., Barnard, J., Campagna, E. J., Garrett, K., Fisher, A., Dickinson,

L. M., & O’Leary, S. T. (2018). Effect of a Health Care Professional Communication Training Intervention

on Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA pediatrics,

172(5), e180016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0016

35

More Information about the COVID-19 Examples

Increasing adult vaccinations at a regional supermarket chain pharmacy: A multi-site demonstration project

Increasing adult vaccinations at a regional supermarket chain pharmacy: A multi-site demonstration

project - ScienceDirect

Coley, K.C., Gessler,C., McGivney, M., Richardson, R., DeJames, J., Berenbrok, L. A. (2020). Increasing adult

vaccinations at a regional supermarket chain pharmacy: A multi-site demonstration project. Vaccine,

38(24), 4044-4049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.040.

Additional Resources for Implementing this Strategy

Communication Skills for Talking About COVID-19 Vaccines - These communication skills are designed for

clinicians to use with patients and families, using an approach adapted from motivational interviewing and

research on vaccine hesitancy.

https://www.capc.org/covid-19/communication-skills-for-talking-about-covid-19-vaccines/

Strategy 5: Financial Incentives

Research Base

Attention, intentions, and follow-through in preventive health behavior: Field experimental evidence on flu

vaccination.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167268115001079?via%3Dihub#abst0005

Bronchetti, E. T., Huffman, D. B., & Magenheim, E. (2015). Attention, intentions, and follow-through in

preventive health behavior: Field experimental evidence on flu vaccination. Journal of Economic Behavior

& Organization, 116, 270-291.

Lottery-Based Incentive in Ohio and COVID-19 Vaccination Rates.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2781792

Walkey, A. J., Law, A., & Bosch, N. A. (2021). Lottery-Based Incentive in Ohio and COVID-19 Vaccination

Rates. JAMA.

Did Ohio’s Vaccine Lottery Increase Vaccination Rates? A Pre-Registered, Synthetic Control Study.

https://osf.io/a6de5/

More Information about the COVID-19 Examples

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) provides guidance to employees regarding offering

COVID-19 vaccine incentives.

https://www.eeoc.gov/wysk/what-you-should-know-about-covid-19-and-ada-rehabilitation-act-and-

other-eeo-laws#K

The National Governors Association maintains a list of state and local government incentives being offered for