COM M E N T ARY Open Access

The James Lind Initiative: books, websites

and databases to promote critical thinking

about treatment claims, 2003 to 2018

Iain Chalmers

1*

, Patricia Atkinson

1

, Douglas Badenoch

2

, Paul Glasziou

3

, Astrid Austvoll-Dahlgren

4

,

Andy Oxman

5

and Mike Clarke

6

Abstract

Background: The James Lind Initiative (JLI) was a work programme inaugurated by Iain Chalmers and Patricia

Atkinson to press for better research for better health care. It ran between 2003 and 2018, when Iain Chalmers

retired. During the 15 years of its existence, the JLI developed three strands of work in collaboration with the

authors of this paper, and with others.

Work themes: The first work strand involved developing a process for use by patients, carers and clinicians to

identify shared priorities for research – the James Lind Alliance. The second strand was a series of articles, meetings,

prizes and other developments to raise awareness of the massive amounts of avoidable waste in research, and of

ways of reducing it. The third strand involved using a variety of approache s to promote better public and

professional understanding of the importance of research in clinical practice and public health. JLI work on the first

two themes has been addressed in previously published reports. This paper summarises JLI involvement during the

15 years of its existence in giving talks, convening workshops, writing books, and creating websites and databases

to promote critical thinking about treatment claims.

Conclusion: During its 15-year life, the James Lind Initiative worked collaboratively with others to create free

teaching and learning resources to help children and adults learn how to recognise untrustworthy claims about the

effects of treatments. These resources have been translated in more than twenty languages, but much more could

be done to support their uptake and wider use.

Keywords: James Lind library, James Lind Alliance, Testing treatments, Testing treatments interactive, Testing

treatments international, Key concepts, Informed health choices projects, Claim evaluation tools, Critical thinking

and appraisal resource library (CARL), GET-IT glossary, Teachers of EBHC, GenerationR, Evaluation of teaching/

learning

Plain English summary

We are bombarded with claims about the effects of

treatments. These reach us through advertising, broad-

casts, newspapers, health professionals, family, and

friends. People often trust these sources of information

more than they trust the results of research. Because

claims about the effe cts of treatments can be wrong, in-

cluding those based on poor research, accepting them

uncritically can result in harm. This is why people need

to be equipped to spot untrustworthy treatment claims.

The skills needed to identify dodgy treatment claims

are not often elements of people’s gener al knowledge.

Between 2003 and 2018, in collaboration with others,

the James Lind Initiative worked to promote an increase

in the general knowledge needed to identify untrust-

worthy treatment claims, and so promote better research

for better health care. This entailed giving talks, conven-

ing workshops, writing books, and creating websites and

databases to promote critical thinking about treatment

claims – among children as well as adults. This article

1

James Lind Initiative, Oxford OX2 7LG, UK

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-019-0138-2

describes the origins and evolution of these initiatives,

and the free teaching and learning resources that have

resulted.

The James Lind Initiative

In 2003, following acceptance of the report of a UK

Medical Research Council (MRC) working party entitled

‘Clinical Trials for Tomorrow’, the Council declared its

commitment to ‘involve patients in all aspects of the

clinical trials it funds’. Iain Chalmers and Patricia Atkin-

son were appointed by the MRC and the Department of

Health to establish:

a communications and discussion forum on

randomised controlled trials , involving patients,

practitioners , researchers and others.

Outline plans for an initiative responding to this brief

were introduced by Iain Chalmers in an article published

in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine at the end

of 2003. The article noted that the initiative was being

established “to lobby for better randomized controlled

trials because these studies can provide some of the

most imp ortant information needed to improve health-

care.” It went on to note that:

Various strategies are likely to be needed if controlled

trials are to improve. One involves promoting greater

public demand for better, more relevant controlled

trials. Because of the various perverse incentives that

distort the research agenda, patients and their

representatives should be encouraged to discriminate

between those controlled trials that deserve their

support and those that do not. Involvement of people

using the health services in all phases of controlled trials

should help to ensure that these studies address issues

that are of real importance, and that the results are

made publicly available. In particular, patients and the

public need to press for funding of trials addressing

questions that are of importance to patients but of no

interest to industry (Chalmers 2003) [1].

The initiative was named for James Lind, the eight-

eenth century Scottish naval surgeon, who organised a

controlled trial to resolve uncertainty about how to treat

scurvy (Lind 1753) [2].

Most of the subsequen t work of the James Lind Initia-

tive (JLI), fell within one of three main strands, all of

which were concerned with engaging with patients, pro-

fessionals and the public. The first strand involved the

piloting and development of the James Lind Alliance

(JLA), an interactive process to help patient s, carers and

clinicians to identify shared research priorities (Chalmers

et al. 2013) [3]. This work exposed a substantial

mismatch between the interventions that patients and

clinicians wished to see evaluated and those (mainly

drugs) that were being assessed by researchers (Crowe

et al. 2015). [4] After the JLI’s development of the JLA

Priority Setting Partnerships, responsibility for additi onal

applications and development pa ssed to the National In-

stitute for Health Research in 2013 for maintenance and

further development (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/).

A second strand of the JLI’s work - to expose and con-

front avoidable waste in research – was prompted by ex-

perience with JLA research Priority Setting Partnerships.

In a paper published in The Lancet in 2009, Iain Chal-

mers and Paul Glasziou (2009) [5] estimated that over

85% of the investmen t in biome dical research was being

avoidably wasted. The paper led The Lancet to invite

Chalmers and G lasziou to coordinate the preparation of

a series of papers with over 40 co-authors (Macleod

et al. 2014) [6] dealing with five important sources of re-

search waste: waste in deciding what research to fund

(Chalmers et al. 2014) [7]; inappropriate research design,

methods, and analysis (Ioannidis et al. 2014) [8]; ineffi-

cient research regulation and management (Salman et al.

2014) [9]; inaccessible research information (Chan et al.

2014) [

10]; and biased and unusable research reports

(Glasziou et al. 2014) [11]. These papers set out some of

the most pressing issues, recommended how to increase

value and reduce waste in biomedical research, an d pro-

posed metrics for stakeholders to monitor the imple-

mentation of these recommendations. Since the Lancet

series was published in early 2014 there has been en-

couraging evidence of steps being taken to reduce waste,

particularly by research funders (Glasziou and Chalmers

2018) [12].

The present article describes a third strand of work

which has existed throughout the life of the JLI between

2003 and 2018, namely, to provide book s, websites, data-

bases and talks for the public and professionals about

why fair tests of treatments are essential, what the fea-

tures of fair tests are, and how everyone can play their

part in promoting critical thinking and better research

for better healthcare.

Books

Testing Treatments, 1st editi on

At the end of 2002, Imogen Evans, a physician then work-

ing at the MRC, was considering writing a book for the

public about clinical trials. She invited Iain Chalmers to

co-author the book and the JLI to coordinate its prepar-

ation. At the suggestion of Mike Clarke, then director of

the UK Cochrane Centre, Hazel Thornton, a breast cancer

patient who had co-founded a Consumers Advisory Group

for Clinical Trials, was invited to become a third co-author.

Testing Treatments: better research for better health

care, authored by Imogen Evans, Hazel Thornton and

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 2 of 14

Iain Chalmers, was published by the British Library in

2006 [13]. The 100-page book was written for anyone who

wanted to understand better why treatments need to be

tested rigorously; how treatments can be tested fairly; and

how everyone interested in health care has a role to play

in promoting better research for better health care.

The book’s eight chapters reflected these consider-

ations. Chapter 3 – Key Concepts in fair tests of treat -

ments – addressed methodological issues relevant to the

fair testing of treatments:

‘Why comparisons are essential’;

‘Why comparisons must address genuine

uncertainties’;

‘Avoiding biased comparisons’ (from differences in

patients being compared and the ways treatment

outcomes have been assessed); and

‘How to interpret unbiased comparisons’, taking

account of the play of chance and all the relevant

evidence.

Translations of the first edition of Testing Treatments

were published in Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian, Pol-

ish an d Spanish. Texts of all these versions were made

freely available through the James Lind Library (www.ja-

meslindlibrary.org), a website illustrating the evolution

of fair tests of treatments (Chalmers et al. 2008 [14];

Chalmers 2015 [15]; and see below). The website had

been launched at the Royal College of Physicians of Ed-

inburgh in 2003 (250 years after Lind’s treatise on

scurvy), and incorporated as an element of the JLI’s

programme of work the same year.

Testing Treatments, 2nd edition

The reception of the first edition of Testing Treat-

ments prompted plans for an enlarged (200-page)

second edition. The 16 pages devoted to Key Con-

cepts in fair tests of treatments in the first edition

was expanded to 41 pages across three chapters in

the se cond edition. The second edition o f the book

also dealt with some of the themes that had been

missing from the first edition. These included, for

example, overtreatment, screening , research regula-

tion, and the use of research evidence to inform de-

cisions in health care.

The co-authors of the first ed ition of the book were

pleased that Paul Glasziou, an Australian general

practitioner, joined as a f ourth co-author to prepare

the 2nd edition of the book, and to add explanatory

diagrams. Comments were s olicited on drafts of this

2nd edition from a hundred people, including many

lay p eople as well as health professionals , journalists,

and researchers.

The book was pu blished by Pinter and Martin in

2011 [16]. By the end of 2018 , translations were avail-

able in Arabic, Ba sque, Catalan, Chinese, Croatian,

Danish, Farsi, French, German, Italian, Japanese,

Korean, Malay, Norwegian, Polish, Portugue se, Rus-

sian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, and Turkish. Texts of

the 2nd edition of Testing Treatments and transla-

tions are available free both through the Testing

Treatments sibling websites www.testingtreatments.org

and through the Cochrane Collaboration’s learning

programmes http://training.cochrane.org/search/site/

testing-treatments. The b ook is bein g downloaded for

free around 100 times a month, and 5965 pu blished

copies have been sold. Audio versions of the book in

Chinese, English and Spanish are also freely available

on the relevant websites. The audiobook in English

has accrued over 4000 listens on Sound Cloud.

Testing Treatments has been well received. In his

Foreword to the 1st edition, Nick Ross, a broadcaster,

wrote that the book is “good for our health [and]

important for anyone concerned about their own or

their family’s health, or the politics of health.” In his

Foreword to the 2nd edition Ben Goldacre, a researcher

and science writer, wrote “I genuinely, truly, cannot rec-

ommend this awesome book highly enough for its clar-

ity, depth, and humanity.”

Testing Treatments has also been well received by

others who have p ublished reviews of the book. It s

strengths were summed up succinctly by a Norwe-

gian physician who judged the book to be “Import-

ant, scary, and encouraging”. Others have written

that Testing Tre atment s is “aterrificlittlebook”

(BMJ ); “a tim ely, inspiring read” (Br J Gen Pract);

“… t he best available introduction to the m ethods ,

uses and value of fair testing” (He alth Affairs); and

that it “… will inform patients , clinicians and

researchers alike” (Lancet), and “

should be required

reading for e veryone interested in healthcare” (J Clin

Res Best Practices). The European Writers’ Associ-

ation noted that the book “… encourages users and

providers of healthcare to question a ssumptions , de-

tect bia ses, and raise questions about the quality of

the evidence if they find it unconvincing ”,andthe

Patient Information Forum concluded that “patient

groups would do well to read, inwardly digest and

then spread the word” (https ://en.testingtreatment-

s.org/book/the-book/reviews/).

Perhaps the best endorsement of the enduring value

of Te sti ng Treatment s is that people continue to go

to the trouble of translating it into other languages.

These reactions to the book probably reflect extensive

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 3 of 14

pre-publication piloting of the text with lay and pro-

fessional readers.

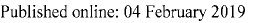

A TTi Editorial Alliance wa s convened by Iain Chal-

mers in 2013 to share experiences of using translations

of the book in different languages (Chen et al. 2015)

[17]. Yaolon g Chen, of Langzhou University, took over

the convenorship of the TTi Editorial Alliance at the

end of 2018 (Fig. 1). Because of the internationalisation

of the TTi, we have chosen to refer to TTi as Testing

Treatment s international.

At the time of writing, in December 2018, there are no

firm plans for a 3rd edition of Testing Treatment s. How-

ever, Paul Glasziou has had exploratory discussions

about extending coverage beyond tests of treatments to

encompass tests of (diagnostic and screening) tests.

James Lind's Introduction to Fair Tests of Treatments,

2019

The 2nd edition of Testing Treatments is nearly 200

pages long, and there have been occasional suggestions

that a shorter book covering similar ground would be

welcomed. As appropriate texts and images in six lan-

guages are already available as explanatory essays in the

James Lind Library (www.jameslindlibrary.org, and see

below), these will be compiled and published in a short

book in 2019. Although the book should be valuable in

its own right, we hope it will also help to draw attention

to The James Lind Library.

Websites

The James Lind Library (www.jameslindlibrary.org)

The web-ba sed James Lind Library (JLL) was created

in 2003, in collaboration with the Sibbald Library at

the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, to

explain and illustrate the development of fair tests of

treatments in health care. The website contains three

main types of material, categorized by methodo-

logical topic (www.jameslindlibrary.org/to pics/). A s

of the end of December 2018, 22 e xplanatory e ssays

(mentioned above) provide an over v iew in six lan-

guages of the topics addressed in the JLL. There are

well over 1000 record s represented in the JLL ,

including scans of key passages at a minimum (with

the majority of these sourced from the Sibbald

Library), a nd often including links to full text , por-

traits , and other material.

The third element of the JLL comprises over 250 ori-

ginal articles. These JLL articles provide brief histories,

commentaries, biog raphies, personal reflections, and

summaries and full texts of relevant doctoral theses. In

the year of the JLL’s launch, Kamran Abbasi, editor of

the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (JRSM) sug-

gested that JLL Articles could be republished in each

monthly issue of the JRSM. This republication arrange-

ment was initiated with an article by Richard Doll on

the introduction of clinical trials using factorial designs

in the late 1940s and early 1950s to compare more than

two treatments concurrently in the same study. More

Fig. 1 The Testing Treatments international Editorial Alliance, 18 September 2018, Cochrane Colloquium, Edinburgh. Back Row: Siti Nurkamilla

(Malay), Mona Nasser (Farsi), Karla Soares-Weiser (Portuguese), Iain Chalmers (representing Turkish), Marimar Ubeda (Basque), Andy Oxman

(English), Giordano Perez Gaxiola (Spanish), Rintaro Mori (Japanese), Myeong Soo Lee (Korean), Liliya Ziganshina (Russian), Mona Nabulsi (Arabic).

Front Row: Gerard Urrutia (Catalan), Benjarin Santatiwongchai (Thai), Minna Johansson (Swedish), Karsten Jorgensen (Danish), Astrid Austvoll-

Dahlgren (Norwegian), Gerd Antes (German), Douglas Badenoch (English), Roberto D’Amico (Italian), Yaolong Chen (Chinese), Tina Poklepovic

Pericic (Croatian). Missing: Philippe Ravaud (French), Metin Gulmezoglu (Turkish)

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 4 of 14

than 200 articles have since been republished in the

JRSM, allowing them to be indexed in PubMed and

other bibliographic databases. The readership of these

JLL articles is further extended through weekly posts on

Twitter and Facebook.

In recent years, under the Associate Editorial responsi-

bility of Douglas B adenoch assisted by Paul Glasziou,

the focus of the JLL has broadened beyond its previous

emphasis on the history of the control of systematic

errors (biases) and random errors (the play of chance)to

include material illustrating innovations in how research

evidence can serve the interests of patients more effect-

ively. For example, records and articles are being added

to illustrate key milestones and developments in

evidence summaries , levels of evidence, and evidence

appraisal.

In 2015, the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

(CEBM) at Oxford University hosted the launch of a beau-

tiful redesign of the JLL website created by Douglas Bade-

noch, Robin Layfield and their colleagues. More recently,

JLL materials have also been used in the development of

the CEBM’s Catalogue of Bias (www.catalogof bias.org).

The JLL is an internationally useful resource, for a

wide range of users. It receives around 200 visits per

day, with an aggregate total of more than 120,000 page

views per year. In a survey in January to April 2018,

more than 400 users of the JLL completed a short,

single-question survey. This revealed that just over half

the users are students; 14% identified themselves as

health professionals, 14% as researchers, 4% as members

of the public, 4% as teachers, and 2% as librarians or

information specialists.

The principal editorial responsibility for The James

Lind Library was with Iain Chalmers’ until the end

of 2018, when Mike Clarke t ook over from him,

with support from Patricia Atkinson and Dougla s

Badenoch.

Testing Treatments international (TTi) English

(www.en.testingtreatments.org)

Release of the 2nd edition of Testin g Tre atmen ts

(Evans et al. 2011) [16] wa s accompanied by the

launch of a website entitled Testing Treatments

interactive (TTi) Fig.2. The website wa s created prin-

cipally to make the text of the book freely and

widely available. Translators of the book into twenty

other languages have followed our example by estab-

lishing ‘sibling’ TTi websites to host translations of

the book in their different languages. In addition to

hosting texts of the book , TTi English and some

other T Ti websites added other resources to their

websites. TTi English, for example, de veloped and

hosted the Critical thinking and Appraisal Resource

Library (C ARL) (Castle et al. 2017) [18], and it

hosted the Key Concepts database, the plain language

gloss ary (GET-IT), the Claim Evaluation Tools

(see belo w), and a gui de to reliable information a bout

the effe ct s of tre atment s (https://en.testingtreatment-

s.org /create-test-claim-evaluation-tools-database/).

Fig. 2 Screenshot of TTi English homepage, 2012

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 5 of 14

Throughout the development of the TTi English web-

site we have consulted lay and professional end-users to

find out what they think of our work . The first formal

assessment of the site was conducted internally in 2012–

13. In late 2012, we surveyed users of the website to find

out more about them and their reasons for using the

site. We found that most users were “intermediaries”,

that is, people who were involved professionally in com-

municating or teaching about health research. Following

on from this, we recruited 20 such “intermediaries” for

hands-on user testing and semi-structured interviews.

They helped us to identify some important barriers to

user understanding.

In particular, many users, particularly patients,

expected a website called “Testing Treatments” to tell

them about specific treatments , rather than the process

of evaluating the effects of treatments in general. They

also told us that we needed to make our credentials

clearer (to reassure users we were not a “crank site”),

and to provide a glossary of jargon terms.

In response, we redesigned the site to guide users

to sources of information about specific treatments

(https://en.testingtreatments.org/testing-treatments-in-

teractive-tti/sources-trustworthy-information-treatmen-

t-effe cts/), and the JLI made clear how our work was

funded, and introduced the personnel behind the pro-

ject. We also collaborated with colleagues in S cotland

and Norway in work funded by the European Com-

mission to de velop a plain language glossary –

GET-IT (Moberg e t al. 2018) [19]. This data base was

designed by Robin Layfield and Douglas B adenoch,

who remain responsible for maintaining and de velop-

ing it.

In 2014, we commissioned the Critical Appraisal Skills

Programme (CASP) to do an external assessment of TTi

English based on interviewing and testing lay people and

some professionals. The further development of the

website reflected the findings. We made clear that the

users we were targeting were ‘intermediaries’ - teachers

of children and adults, journalist s, and science writers –

although not explicitly excluding lay users who wished

to teach themselves. We simplified the home page, to

emphasise that the website is concerned with ‘healthy

scepticism’; to give more emphasis to the resources con-

tained in the site; and to reduce clutter on the home

page Fig. 3.

This simplified front-end was developed in parallel

with the Informed Health Choices Project’s creation of a

Key Concepts framework for evaluating treatment claims

(Austvoll-Dahlgren et al. 2015 [20]; Chalmers et al. 2018

[21]; Oxman et al. 2018 [22]; and see below).

TTi English content was re-indexed using this tax-

onomy, and new resources were added regularly to en-

courage return visits. By this time, we had built up a

substantial collection of learning resources (TT Extra s),

which provided a clearer offering to users.

This content was expanded into the Critical think-

ing and Appraisal Resource Library (CARL). Open

access learning resources were identified to supple-

ment the learning from t he book. These were were

collated and indexed using the Key Concepts tax-

onomy. The resulting database was embedded in the

TTi English website (Fig. 4). The methods used to

create CARL have been documented by Castle and

his colleagues (2017) [18

].

A further external assessment was commissioned in

2016 to assess these changes. The findings th is time

made clear that we had over-reached ourselves! Feed-

back made clear that the website wa s attempting to

ser ve the needs of too many diverse groups , with the

result that people coming to it were unclear for whom

it had been developed. We concluded that we had

been too ambitious in imagining that the website

could ser ve the needs of teachers of too wide a range

of learners - primary school children, teenagers, un-

dergraduates , graduates , and individual members of

the public. It wa s clear that a radical rethink was

required.

After consultation and discussion by the editorial team,

we decided that two distinct websites should be created

from the TTi English site. One of these would return to

an earlier, simpler design with the public in mind; the

other would be developed explicitly to meet the needs of

Teachers of Evidence-Based Health Care Fig. 5.

Website of resources for teachers of evidence-

based health care

In 2018, the ideas and methods of the CARL database

were extended to include materials for teaching EBHC

to undergraduate or postgraduate health professionals,

and students with a special interest in EBHC, such as

Students for Best Evidence [https://www.students4beste-

vidence.net/].

The concept of such a database and a prototype

website were discussed over two meetings at the

Evidence-Based Health Care Conference in Sicily, set-

ting out the scope and processes. As the design and

conception de veloped, the group provided feedback ,

and helped to refine f unctionality and design, and

source further c ontent. The shared aim is for a global

sharing platform of materials for teaching EBHC, with

an emphasis on those that have reliable evidence of

effectiveness.

For inclusion, learning resources must be freely available

and be relevant to one or more of: the EBM Stages

(0 Why EBM? 1 Asking focused questions, 2 Finding

evidence, 3 Appraising evidence, 4 Decision making, 5

Evaluating performance), or one of the Key Concepts.

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 6 of 14

The development of the new website was supported

by the JLI until its launch on 1 November 2018. Support

to maintain the new website is now provided by the Na-

tional Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and

Cochrane UK, and the International Society for

Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC).

Given the diversity of courses, stages, and curriculum

contexts, the database provides modular materials for a

variety of uses such as: (i) preparing a lecture at short

notice, (ii) needing to find an amusing or engaging illus-

tration of EBHC concept s, (iii) planning a course on

EBHC, (iv) finding preparatory reading for students, or

(v) first-time course development.

The database was seeded with over 550 resources

identified through systematic searching of the internet

(Castle et al. 2017) [18]. The network started with about

40 members from around the world recruited at the Si-

cily meeting.

To be included in CARL, a learning resource must be

freely available and relevant to one or more of the: EBM

Stages, EBHC Competences, or Key Concepts, as set out

by Loai AlBarqouni and his colleagues (2018) [23]. Con-

tent is edited by Patricia Atkinson, Douglas Badenoch and

Paul Glasziou, with support from an Editorial Board of

six. End users suggest content for the Database, which is

checked, indexed and approved by editors before publica-

tion in the Database. Users can sign up for a regular email

digest of new resources that have been added to the Data-

base. Members can comment on or rate resources and

create ‘Bundles’ of resources for their own use Fig. 6.

The Teachin g EBHC website http://www.teachingebh-

c.org) was launched at the annual conference of the

Fig. 3 Screenshot of TTi English homepage, 2014

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 7 of 14

International Society for Evidence-Based Health Care in

the United Arab Emirates on 1 November 2018. Since

then, over 150 additional members have registered

on the w ebsite, and are contributing new learning

resources.

Paul Glasziou will be the caretaking editor of TTi Eng-

lish from April 2019, and he coordinates the development

of the website for Teachers of Evidence-Based Healthcare.

Douglas Badenoch remains intimately involved in both

websites.

GenerationR website (http://generationr.org.uk/)

The Young Persons’ Advisory Groups (YPAGs) for

clinical trials launched GenerationR at the Science

Museum in London in September 2013 to tell others

about how the y we re helping researchers design clin-

ical trials involving children. They invited Iain Chal-

mers to contribute to the launch and asked him to

speak a bout waste in research and how they might

help to reduce it. This led to discussions with repre-

sentatives and facilitators of a ll five YPAGs at many

meetings during 2014 and 2015.

The GenerationR report published in the spring of

2014 called for the creation of a dedicated GenerationR

website. This was achieved with funds provided through

the JLI and five planning meetings with YPAG members

coordinated by Jennifer Preston (Liverpool YPAG), and

facilitated by Douglas Badenoch, with support from

Patricia Atkinson and Iain Chalmers. The website was

launched in 2014, initially within TTi English, then sep-

arately at http://generationr.org.uk/ Fig. 7.

With the website established, the JLI focused on one

of the other recommendations in the GenerationR re-

port, which asked for “Work with the education sector

to promote clinical research education in schools, shar-

ing resources such as Testing Treatment s interactive …”.

Iain Cha lmers tried to promote collaboration among

YPAGs to de velop and evaluate training materials ,

with a view to creating a cadre of young people

equipped to promote l earning in schools (‘GenR Am-

bassadors’). This effort was unsuccessful, howe ver, not

least because YPAG facilitators were victims of yet

another internal reorganisation of the NHS , with

inevitable uncertainties about jobs and lines of

Fig. 4 Screenshot of TTi English homepage, 2016

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 8 of 14

accountability. These developments were a disappoint-

ing blow to JLI’s hopes to de velop a meaningful Gen-

erationR/JLI collaboration. Iain Chalmers de cided that

his time and other JLI resources should be redeployed

instead through involvement with primary schools in

the work o f the Informed Health Choices Project

(see below).

Databases

Since its inception in 2011, TTi English has hosted and

made accessible several ‘proto-databases’. As the JLI came

to an end, these have been established as stand-alone data-

bases which can be plugged into a variety of websites.

Critical thinking and assessment resource library

(CARL)

In April 2011, the JLI hosted an international meeting on

‘Enhancing Public Understanding of Health Research’,held

at Kellogg College, Oxford. The meeting was supported by

the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the

Wellcome Trust. In preparation for the meeting, an inven-

tory of interactive applications and learning materials to

teach people how to be critical users of information about

the effects of health care was prepared.

The meeting led to the creation of an international

Network to Support Understanding of Health Research

(NSUHR) and a proposal to develop BS Detective – aso-

cial media project to help people distinguish trustworthy

from untrustworthy health research and reporting. Exten-

sion and maintenance of the inventory of learning re-

sources was envisaged as a component of this initiative.

We were disappointed that, despite encouragement from

and detailed consultation with advisers at the Wellcome

Trust, the proposal for BS Detective was rejected by the

Trust.

Fortunately, NIHR’s support for the JLI enabled exten-

sion of the initial inventory of learning resources pre-

pared for the 2011 conference. To supplement the text

of the Testing Treatments book, learning resources in

the forms of text, video, audio and other media were

added as ‘TT Extras’ to the T Ti English website.

In 2012, funds were obtained from the European Com-

mission “to identify and develop materials to enhance

public understanding of clinical trials”. The JLI was one of

the partners in ECRAN - the European Communication

Fig. 5 Screenshot of TTi English homepage, 2018

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 9 of 14

on Research Awareness Needs (Mosconi et al. 2016) [24].

The JLI was a partner in the ECRAN project and learning

resources identified and developed by ECRAN were incor-

porated as TT Extras in the TTi English website.

The TT Extras provided the foundation for developing the

Critical thinking and Appraisal Resource Library (CARL) to

help people understand and apply key concepts in assessing

treatment claims (Castle et al. 2017) [18]. Additional learn-

ing resources were identified through relevant systematic

reviews (Nordheim et al. 2016 [25]; Austvoll-Dahlgren et al.

2016 [26]; Cusack et al. 2018 [27]; Albarqouni et al. 2018

[23]) and online and database searches.

CARL currently contains over 550 open-access learn-

ing resources in a variety of formats: text (including ex-

tracts from Testing Treatments and explanatory essays

from the James Lind Library), audio, video, web pages,

cartoons and lesson materials (Castle et al. 2017) [18].

At the end of 2018, responsibility for the maintenance

Fig. 7 Screenshot of GenerationR homepage

Fig. 6 Teachers of EBHC Learning Resources Database, 2018

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 10 of 14

and development of CARL was transferred from the JLI

to the Society of Evidence-Based Health Care.

Informed health choices databases

Soon after publication of the 2nd edition of Testing

Treatments in 2011, Andy Oxman, then a researcher at

the Global Health Unit in the Norwegian Knowledge

Centre for the Health Services, observed that the Testing

Treatments book alluded to many of the Key Concepts

that people need to consider when assessing the trust-

worthiness of claim s about the effects of treatments. He

proposed assessing whether these Key Concepts could

be taught to and successfully applied by primary school

children in low income countries when they were asses-

sing the trustworthiness of claims about health.

A project proposal –‘Supporting informed healthcare

choices in low-income countries’ - was developed and

submitted to the GLOBVAC programme of the Research

Council of Norway. The project came to be known as

the Informed Health Choices (IHC) Project (www.infor-

medhealthchoices.org). Iain Chalmers was grateful to

have been invited to become a member of the substan-

tial project team, along with other members in Norway

and East Africa, and to involve the JLI in the project.

Iain Chalmers’ principal involvement has been by

working with Andy Oxman and Astrid Austvoll-

Dahlgren to (i) identify the Key Concepts to be taught to

learners, and (ii) develop multiple-choice questions - the

Claim Evaluation Tools - to assess people’s ability to

apply the Key Concepts in practice (Austvoll-Dahlgren

et al. 2016 [25]; 2017 [28 ]). Since its creation, informa-

tion about the Key Concepts and Claim Evaluation Tools

has been made available through TTi English but separ-

ate databases have been or are being created for these

resources.

Key concepts database

A first list of 32 Key Concepts relevant to assessing the

trustworthiness of treatment claims was published by As-

trid Austvoll-Dahlgren and colleagues in 2015 (Austvoll--

Dahlgren et al. 2015) [20]. Since its first iteration, the list

has been reassessed every year, and currently consists of

44 concepts (Chalmers et al. 2018 [21]; Oxman et al. 2018

[22]). The list has provided an invaluable basis for organis-

ing and coding materials in TTi English, the JLL, and

CARL.TheKeyConceptshavealsobeenusedbyStu-

dents 4 Best Evidence (coordinated by Cochrane U K),

which has published blogs and short videos on all of

them (https://www.student s4beste vidence.net/tag/key-

concepts/).

The list of Key Concepts serves as a syllabus for devel-

oping learning resources. As such, it is a starting point

for teachers or researchers to develop tailored

interventions to help people in specific target groups to

make informed health choices. Although the list of IHC

Key Concepts was developed to promo te informed

choice of interventions to protect health, it has been

shown to be applicable in education more generally

(Chalmers et al. 2018 [21]; Sharples et al. 2017 [29]).

The draft 2018 edition of the Key Concepts for

promoting informed c hoices in health wa s presented

and discussed at international meetings in June in

Oxford and in Edinburgh in September. A meeting

in December 2018, convened by Andy Oxman and

Iain Chalmers , explored the extent to which the Key

Concepts can be applied to inter ventions in other

areas in which claims are made about the effects of

inter ventions – spe cifically, about agricultural, eco-

nomic, educational, environmental, informal learning,

international d evelopment, management, nutritional,

planetary health, policing , social welfare, speech and

language, and veterinary interventions.

Claim evaluation tools database

All the questions with the IHC’s Claim Evaluation Tools

database have been developed for use in children (from

the age of 10) as well as for adult s (including health pro-

fessionals). These multiple-choice questions can be used:

to test critical abilities in school and other teaching

settings

to evaluate out comes of educational interventions

assessed in randomised trials

to gauge critical abilities in a population, and thus

provide background information to help tailor

interventions to address peo ple’s educ ational needs.

The multiple-choice questions are currently available

in English, Norwegian, Chinese, Spanish, German and

Luganda, and a network of people working with or wish-

ing to work with the tools is emerging.

Evaluating the effects of educational

interventions

Although feedback on the resources discussed so far

in this article has been encouraging , there is no hard

evidence that they have promoted critical thinking

about treatment claims , let alone whether they have

been useful in applying any learning in practice

when making health choices. As made clear in a sys-

tematic review by Cusack and her colleagues (2018)

[27], robust evaluation of well-intentioned resources

designed to equip people to b e ‘health literate’ are

vanishingly rare (see, for example, Woloshin et al.

2008; [30] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/234

69386).

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 11 of 14

As mentioned above, the JLI failed to engage those

responsible for the Young Persons Advisory Groups

(YPAGs) and GenerationR in developing a progra mme

to foster and assess relevant learning amo ng the children

and young people associated with the groups (Chalmers

2016) [31]. In the light of this disappointment, the in-

volvement of Iain Chalmers, Patricia Atkinson, and the

JLI in the IHC Project (www.informedhealthchoices.org )

was very welcome, particularly as Testing Treatments

had been the starting place for the IHC Key Concepts.

The IHC Project developed teaching materials - a car-

toon story book and a podcast – and used randomised

trials involving over 10,000 Year 5 Ugandan primary

school children (Nsangi et al. 2017) [32] and over 500 of

their parents (Semakula et al. 2017) [33] to measure the

effects of the teaching materials on their assessment of

treatment claims. The teaching materials were successful

in promoting application of the Key Concepts in judging

the trustworthiness of treatment claims. A year later, the

children’s abilities had continued to improve, but those

of the parents had decayed (Nsangi et al.; Semakula

et al. unpublish ed data).

These experiments have provoked interest around the

world (http://www.informedhealthchoices.org/news/)and

a 53-min BBC World documentary about the research

was presented by David Spiegelhalter (The Documentary:

You can handle the truth), who described the IHC Project

as “a wholly new type of evaluative research.”

The JLI’s involvement in the IHC Project is the high

point of the Initiative’s efforts to meet its objectives over

the past 15 years.

Conclusions

This paper is the last of three papers summarizing the

three principal strands of work of the James Lind Initia-

tive during its 15-year life between 2003 and 2018. The

Fig. 8 The evolution of Testing Treatments English and the James Lind Library, 2003–2018

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 12 of 14

first of these papers described the development of the

James Lind Alliance (JLA), a process to help patients,

carers and clinicians to agree on research priorities. The

second paper reviewed efforts made by the JLI and

others to expose and address avoidable waste in re-

search. This third and final paper refers to the use of

talks, seminars, books, websites, databases and con-

trolled experiments to promote critical thinking about

treatment claims. Figure 8 illustrates how – beginning in

2003 – the James Lind Library and the 1st edition of

Testing Treatments evolved and led to the creation of

several other teaching an d learning resources, and to

some important controlled trials to assess their

effectiveness.

At the beginning of 2019, the JLI’s involvement with

these resources ended with Iain Chalmers’ retirement.

The contact authors for four of the principal resources

are now as follows:

TTi English for the Public: Paul Glasziou pglaszio@-

bond.edu.au

Informed Health Choices: Andy Oxman oxman@

online.no

CARL for Teachers of EBHC: Douglas Badenoch

douglas.badenoch@minervation.com

Abbreviations

CARL: Critical thinking and Appraisal Resource Library; CASP: Critical Appraisal

Skills Programme; CEBM: Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; EBHC: Evidence-

Based Health Care; ECRAN: European Communication on Research Awareness

Needs; GET-IT: Plain language glossary; IHC: Informed Health Choices Project;

JLA: James Lind Alliance; JLI: James Lind Initiative; JLL: James Lind Library;

JRSM: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine; MRC: (UK) Medical Research

Council; NIHR: National Institute for Health Research; NSUHR: Network to

Support Understanding of Health Research; TTi: Testing Treatments interactive/

international; YPAGs: Young Persons’ Advisory Groups

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Institute for Health Research for its support

of the James Lind Initiative; to the Naji Foundation for its support of user

testing of TTi English; and to the Research Council of Norway for its support

of the Informed Health Choices Project.

Funding

National Institute for Health Research, Research Council of Norway, and Naji

Foundation.

Availability of data and material s

The material discussed is openly accessible.

Authors’ contributions

IC (guarantor) – coordinator, James Lind Initiative, 2003–18; main author. PA

– administrator, James Lind Initiative, 2003–18; co-author. DB – co-editor,

CARL for Teachers of EHBC; co-author. PG – editor, TTi English; co-author.

AA-D – co-editor, TTi English; co-author. AO – director, Centre for Informed

Health Choices; co-author. MC – editor, James Lind Library; co-author. All au-

thors contributed to drafting, read three drafts, and approved the draft sub-

mitted for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Publisher’sNote

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1

James Lind Initiative, Oxford OX2 7LG, UK.

2

Minervation Ltd, The

Wheelhouse, First Floor, Angel Court, 81 St Clements Street Oxford, England

OX4 1AW, UK.

3

Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University,

Gold Coast QLD 4229, Australia.

4

Regional Centre for Child and Adolescent

Mental Health, Eastern and Southern Norway, Gullhaugveien 1-3, 0484 Oslo,

Norway.

5

Centre for Informed Health Choices, Norwegian Institute of Public

Health, Box 4404, Nydalen, N-0403 Oslo, PO, Norway.

6

Centre for Public

Health, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Block B, Queens University Belfast, Royal

Hospitals, Grosvenor Road, Belfast BT12 6BJ, UK.

Received: 29 December 2018 Accepted: 15 January 2019

References

1. Chalmers I. The James Lind initiative. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:575–6.

2. Lind J. A treatise of the scurvy. In three parts. Containing an inquiry into the

nature, causes and cure, of that disease. Together with a critical and

chronological view of what has been published on the subject. Edinburgh:

Printed by Sands, Murray and Cochran for A Kincaid and A Donaldson, 1753.

3. Chalmers I, Atkinson P, Fenton M, Firkins L, Crowe S, Cowan K. Tackling

treatment uncertainties together: the evolution of the James Lind initiative,

2003-2013. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:482–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0141076813493063.

4. Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, Chalmers I. Patients', clinicians' and the research

communities' priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch.

Research Involvement and Engagement. 2015;1:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/

s40900-015-0003-x http://www.researchinvolvement.com/content/1/1/2.

5. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of

research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374:86–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-

6736(09)60329-9.

6. Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, Dirnagl U, Chalmers I, Ioannidis JPA,

Salman RA, Chan A-W, Glasziou P. Biomedical research: increasing value,

reducing waste. Lancet. 2014;383:4–6.

7. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM,

Howells DW, Ioannidis JPA, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce

waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383:7–16.

8. Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D,

Schulz KF, Tibshirani R. Increasing value and reducing waste in research

design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:166–75.

9. Salman RA-S, Beller E, Kagan J, Hemminki E, Phillips RS, Savulescu J, Macleod

M, Wisely J, Chalmers I. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical

research regulation and management. Lancet. 2014;383:27–36.

10. Chan A-W, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC,

Krumholz HM, Ghersi D, van der Worp HB. (2014). Increasing value and

reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet. 2014;383:257–66.

11. Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, Michie S,

Moher D, Wager E. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of

biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383:267–76.

12. Glasziou P, Chalmers I. The $100bn a year scandal of wasted medical

research that distorts clinical practice and causes harm to patients. BMJ.

2018;363:k4645.

13. Evans I, Thornton H, Chalmers I. Testing treatments. In: British library; 2006.

14. Chalmers I, Milne I, Tröhler U, Vandenbroucke J, Morabia A, Tait G, Dukan E.

The James Lind library: explaining and illustrating the evolution of fair tests

of medical treatments. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of

Edinburgh. 2008;38:259–64.

15. Chalmers I. Launch of the redesigned James Lind Library – 20 May 2015.

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 25 June 2015. https://www.cebm.net/

2015/06/launch-of-the-redesigned-james-lind-library-20th-may-2015/.

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 13 of 14

16. Evans I, Thornton H, Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Testing treatments. Pinter and

Martin; 2011.

17. Chen Y, Chalmers I. On behalf of the TTi editorial Alliance. Testing treatments

interactive (TTi): helping to equip the public to promote better research for

better health care. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2015;8:98–102. https://

doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12155 http://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com.

18. Castle JC, Chalmers I, Atkinson P, Badenoch D, Oxman AD, Austvoll-Dahlgren

A, Nordheim L, Krause K, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Burls A, Mosconi P,

Hoffmann T, Cusack L, Albarqouni L, Glasziou P. Establishing a library of

resources to help people understand key concepts in assessing treatment

claims – the ‘critical thinking and appraisal resource library’ (CARL). PLoS One.

2017;12(7):e0178666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178666 http://www.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0178666.

19. Moberg J, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Treweek S, Badenoch D, Layfield R, Harbour

R, Rosenbaum S, Oxman AD, Atkinson P, Chalmers I. The plain language

glossary of evaluation terms for informed treatment choices (GET-IT) at

https://www.getitglossary.org. Research for All 2018;2:106–121.

20. Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Oxman AD, Chalmers I, Nsangi A, Glenton C, Lewin S,

Morelli A, Rosenbaum S, Semakula D, Sewankambo N. Key concepts that

people need to understand to assess claims about treatment effects.

Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2015;8:112–25 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

com/enhanced/doi/10.1111/jebm.12160/.

21. Chalmers I, Oxman AD, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Ryan-Vig S, Pannell S,

Sewankambo N, Semakula D, Nsang i A, Barqouni L, Glasziou P , Mahtani

K, Nunan D, Heneghan C, Badenoch D. Key concepts for informed

health cho ices: a framework for helping people learn how to assess

treatment claims and make informed choices. BMJ Evid Based Med.

2018;23:29–33.

22. Oxman AD, Chalmers I, Austvoll-Dahlgren a on behalf of the informed

health choices group. Key concepts for assessing claims about treatment

effects and making well-informed treatment choices [version 1; referees:

awaiting peer review]. F1000 Research 2018;7:1784 (https://doi.org/10.

12688/f1000research.16771.1).

23. Albarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, Young N, Ilic D, Shaneyfelt T,

Haynes RB, Guyatt G, Glasziou P. Core competencies in evidence-based

practice for health professionals: consensus statement based on a

systematic review and Delphi survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180281.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0281.

24. Mosconi P, Antes G, Barbareschi G, Burls A, Demotes-Mainard J, Chalmers I,

Colombo C, Garattini S, Gluud C, Gyte G, Mcllwain C, Penfold M, Post N,

Satolli R, Valetto MR, West B, Wolff S. A European multi-language initiative

to make the general population aware of independent clinical research: the

European communication on research awareness need (ECRAN) project.

Trials. 2016;17:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1146-7.

25. Nordheim LV, Gundersen MW, Espehaug B, Guttersud Ø, Flottorp S. Effects

of school-based educational interventions for enhancing adolescents’

abilities in critical appraisal of health claims: a systematic review. PLoS One.

2016;11(8):e0161485 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161485 PMID:

27557129.

26. Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Semakula D, Nsangi A, Oxman A, Chalmers I, Rosenbaum

S, Guttersrud Ø. The IHC Group. Measuring ability to assess claims about

treatment effects: the development of the ‘claim evaluation tools. BMJ Open.

2016;6:e013184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013184.

27. Cusack L, Del Mar CB, Chalmers I, Hoffmann TC. Education interventions to

improve people’s understanding of key concepts in assessing the effects of

health interventions: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(37).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0213-9 http://systematicreviewsjournal.

biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0213-9.

28. Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Guttersrud Ø, Nsangi A, Semakula D, Oxman AD. The

IHC group. Measuring ability to assess claims about treatment effects: a

latent trait analysis of the claim evaluation tools using Rasch modelling. BMJ

Open. 2017;0:e013185. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013185.

29. Sharples JM, Oxman AD, Mahtani KR, Chalmers I, Oliver S, Collins K, Austvoll-

Dahlgren A, Hoffmann T. Critical thinking in healthcare and education. BMJ.

2017;357:j2234.

30. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Welch HG. Know your chances: understanding

health statistics. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 2008.

31. Chalmers I. Report of the work of the James Lind Initiative (JLI), 1 August

2015–31 July 2016, submitted to the National Institute for Health Research.

32. Nsangi A, Semakula D, Oxman AD, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Oxman M,

Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Glenton C, Lewin S, Nyirazinyoye L, Kaseje M,

Chalmers I, Fretheim A, Ding Y, Sewankambo NK. Effects of the informed

health choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in

Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects: a cluster-

randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;390:374–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-

6736(17)31226-6

.

33. Semakula D, Nsangi A, Oxman AD, Oxman M, Austvoll-Dahlgren A,

Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Glenton C, Lewin S, Nyirazinyoye L, Kaseje M,

Chalmers I, Fretheim A, Kristoffersen DT, Sewankambo NK. Effects of the

informed health choices podcast on the ability of parents of primary school

children in Uganda to assess claims about treatment effects: a randomised

trial. Lancet. 2017;390:389–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31225-4.

Chalmers et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2019) 5:6 Page 14 of 14