1

FamilyTies,InheritanceRights,andSuccessfulPoverty

Alleviation:EvidencefromGhana

*

EdwardKutsoati

a

andRandallMorck

b

Thisdraft:February29,2012

Abstract

Ghanaian custom views children as members of either their mother’s or father’s lineage

(extendedfamily), butnotboth.Patrilineal customchargesaman’slineagewith caringforhis

widow and children, while matrilineal custom places this burden on the widows’ lineage – her

father,brothers,anduncles.Deemingcustominadequate,andtopromotethenuclearfamily,

Ghanaenactedthe IntestateSuccession(PNDC)Law 111,1985and1998 Children’s Act560to

force men to provide for their widows and children, as in Western cultures. Our survey shows

that, although most people die intestate and many profess to know Law 111, it is rarely

implemented. Knowledge of the law correlates with couples accumulating assets jointly and

with inter‐vivos husband to wife transfers, controlling for education. These effects are least

evident for widows ofmatrilineal lineage men, suggesting a persistence of traditional norms.

Widowswithclosertieswiththeirownortheirspouse’slineagereportgreaterfinancialsupport,

asdothoseveryfewwhobenefitfromlegalwillsoraccessLaw111and,importantly,widowsof

matrilineallineage.SomeevidencealsosupportsAct560benefitingnuclearfamilies,especially

if the decedent’s lineage is matrilineal. Overall, our study confirms African traditional

institutions’persistentimportance,andthelimitedeffectsofformallaw.

*

We are deeply grateful to Kofi Awusabo‐Asare for coordinating our household survey and his numerous

suggestions along the way.We are also gratefulto the managementofSocialSecurity andNational Insurance

Trust (SSNIT) Fund of Ghana for providing access to individual records; and the team of research assistants:

Yvonne Adjakloe, Eugene Darteh and Kobina Esia‐Donkoh for their superb field work; William Angko and Alex

Larbie‐MensahforthepainfultaskofcollectingtheSSNITdata;andGreatjoyNdlovuandPanosRigopoulosfor

excellentassistancewiththedataanalysis.WethankparticipantsattheNationalBureauofEconomicResearch

(NBER)/Africa Project meetings in Cambridge and Zanzibar for their comments; and gratefully acknowledge

financialsupportfromtheNBERandtheSSHRC.Theviewsexpressedhere howeveraresolelyours anddonot

reflectthoseoftheNBERortheSSNIT.

a

Department of Economics, Tufts University, Medford, MA USA 02155. Phone: +1 (617) 627‐2688.Email:

b

Distinguished University Professor and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Chair in Finance, University of

Alberta School of Business, Edmonton CANADA T6G2R6; Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic

Research.E‐mail:[email protected]

.Phone:+1(780)492‐5683.

2

1. Introduction

In much of sub‐Saharan Africa, the idea of a family extends beyond its conjugal members. A

lineage, or extended family, is a far larger web of relationships in which all members have a

commonancestor,eithermaleor female.One’srelationshipwithmembersofone’sextended

familymaybeasimportantas,andinsomecases,moreimportantthan,one’srelationshipwith

one’s spouses and children. Historically, lineages are bastions of emotional and financial

support (Plateau, 1991). Lineages can pay for education and training, and their social safety

netscansupport risk‐taking and entrepreneurship.However,expectationsofbeingsupported

by, and of having to support, members of one’s lineage can also deter human capital

accumulation, labor supply, entrepreneurship and risk taking.

1

The actual importance of

extendedfamiliesinanygivencontextisthusanempiricalquestion.

This study explores how inheritance rules in two distinct Ghanaian systems of defining

extended family membership interact with formal legal inheritance rules to affect asset

accumulationduringmarriageandtheeconomicsituationsofwidowsandtheirchildren.Until

1985,intestateinheritancesweredeterminedbytraditionalcustom,andthisdependedonhow

one’s extended family was defined.People whose tribal customs are matrilineal define their

lineages through their female bloodlines only:their mothers and maternal cousins, aunts,

uncles, grandparents, and so on are their blood kin; but their fathers and paternal cousins,

aunts, uncles, grandparents, and so on are not.People whose tribal customs are patrilineal

analogously define blood kinship as flowing through their paternal, but not maternal

bloodlines.Undermatrilineal lineagenorms,aman’schildrenarethusnothisbloodkin,and

hisheirshouldhe

dieintestate(withoutalegalwill)ishissister’sson,hisnearestbloodrelative

in the next generation. Under patrilineal norms, his estate devolves to his children, who are

consideredhisbloodkin.Underbothtraditionalnorms, widowshavenoinheritancerights,and

1

Africanextendedfamiliesareattractingnewattentioninboththetheoreticalandempiricaleconomics

literatures.Bertrand,MullainathanandMiller(2003)findolderrelativesbecomingeligibleforpensionpayments

affectadultlaborsupplydecisionsinblackSouthAfricanhomes.ChitejiandHamilton(2002)findtransfersfrom

richertopoorermembersof

African‐Americanfamiliesdeterwealthaccumulationmorethaninwhitefamilies.

HoffandSen(2005)modelextendedfamiliesbecomingpovertytraps;andAlgerandWeibull(2008and2010)

shothatthetheexpectationoffinancialassistancefromfamilymemberscanpreventthedevelopmentof

insurancemarkets.

3

are oftenleftwithnoassetsbecause of a traditional presumption that assets acquired during

marriage belong to the husband.Rather than relying on their husbands’ estates, they must

dependontheirlineages’socialsafetynets.

The1985IntestateSuccession (PNDC)Law111 wasenactedto alterperceivedadverse

effects of these traditional norms, especially on widows with husbands of matrilineal lineage.

Our surveys of widows living in villages selected for matrilineal, patrilineal or mixed lineage

norms,revealthataquarterofacenturylater,Law111islittleusedandtraditionalinheritance

normspersist.Thisconfirmspreviouswork(FIDA,2007;FenrichandHiggins,2005;andScholz

andGomez,2004).Welinkthistoadearthofinformationabouttheformallaw,lackofaccess

to the formal judicial system, and the continued social importance of overtly adhering to

traditionalnorms.Mostlow‐incomeGhanaians die intestate;andwhile someprofesstoknow

ofLaw111, remarkablyfewmakeuseofit.Thosewhoknowofthelawhave,however,built up

morefamilyassets jointly, evenaftercontrolling education level.Thiseffectis, however,least

evident for widows with husbands from matrilineal lineage traditions – the very people the

reformsfocusedonadvancing.

Wealsosurveywidowsabouttheextentofsupportfromtheirlineages,andtheiraccess

toeconomic(money,educationandhealthcare)andsocialsupport.Widowswhoacknowledge

closertieswithmembersofeithertheirownortheirspouse’slineagereportmoresupport,as

do those very few who made use of Law 111 or who inherited via a legal will.Intriguingly,

widows of matrilineal lineage also report better economic support, consistent with maternal

lineagesocialsafetynetsbeingmoreeffective.

Oursurveytargetswidowslivinginvillages,andnotconnectedtotheformalsectorof

theeconomy.

Whilethesearemostrepresentative,theinheritancepracticesofpeopleinthe

formalsectorarealsoofinterest.Duetothelowsurveyresponseratesfrommiddleandhigh

incomefamilies,wetherefore complementoursurveyanalysiswithindividual‐leveldata from

theSocialSecurityandNationalInsurance Trust(SSNIT),

thesolepension annuityprogramfor

retirees.Thisprogramprovidesretireeswithfixedpensionannuitiesandshould theydiebefore

theannuityexpirationdates,survivorbenefitspayabletoselectedheir(s).Inasecondattempt

to improve the economicsituations of widows and their children, the 1998 Children Act 560

4

mandatesthat60%ofthissurvivorbenefitpasstothedecedent’schildrenagedunder18,with

thedecedent’schoiceofbeneficiariesgoverningonlythedispositionoftheremaining40%.

Due to confidentiality rules, the SSNIT allowed access only to older files.Despite this

working against finding significant effects, the data provide some evidence that Act 560

benefitsthenuclearfamiliesofdecedents,especiallythoseofmatrilineallineage.

Together these results indicate that these formal legal reforms have a very limited

impactonmost Ghanaians.Specifically,theyareefficaciousonlyforpeopleconnectedtothe

formal economy.For most Ghanaians, living in villages and dependent on the traditional

economy,thereformsareeitherirrelevantorofindirecthelponly.

Ourstudycomplementsa growing empiricalliteratureontheeconomicsofthefamily;

and on the importance of inheritance rights in developing countries. Quisumbing and Ostuka

(2001) link land inheritance rights to skills acquisition decisions in Sumatra; Quisumbing,

Panyongayong, Aidoo and Otsuka (2001) report that improved women’s land rights in Ghana

incentivize the cultivation of tree crops, such as cocoa. Lastarria‐Cornhiel (1997) link

privatization to the land rights of marginalized Africans. Hacker (2010) provide a broad

literaturereview,anddiscussgender‐relatedinheritanceissuesindifferentpartsoftheworld.

Ellul,PaganoandPanuzi (2010), inasampleof10,004familyandnonfamilybusinesses across

38 countries, find that strict (traditional) inheritance laws interact with weak investor

protection laws to impede investment in family businesses, but not in non‐family businesses.

Where inheritance norms allow (or require) business owners to bequeath more substantial

proportions of their estates to non‐controlling heirs, investors are more reluctant to provide

externalcapital.

Thepaperisorganizedasfollows:Section2 provides a briefbackgroundontraditional

inheritancerulesinmatrilinealandpatrilineallineages.Section3

outlinestherelevantfeatures

of Law 111 and Act 560. Section 4 describes our data, and section 5 summarizes our

econometricmethodologyandempiricalresults.Section6concludes.

5

2. TraditionalInheritanceRules:ABackground

The inheritance rights of spouses and children depend on the form of their marriage and on

their lineage traditions.Marriages in Ghana can be monogynous or polygynous, and can be

ordinance marriages (legally valid civil or Christian marriages) or customary marriages as

prescribedbycustomarytribaltraditions.

2

Thelastisbyfarthemostpopular,withuptoeighty

percent of marriages in contemporary Ghana entered solely under the customary system

(Awusabo‐Asare,1990).

Inpractice,almostallcouplesmarryinatraditionalceremonyrecognizingthenewbond

between the two families.Subsequently, some follow up with an ordinance marriage in a

church.Theseareusuallywealthiercouples.Notalltraditionalmarriagescanbe recapitulated

as ordinance marriages because traditional marriages can be polygynous, while ordinance

marriagescannot.While theordinancemarriagemay specifyinheritancerules– for example,

thatequalthirdsmightgotothedecedent’sspouse,children,andextendedfamily–customary

rulestakeprecedenceinmarriagesthatarealsoenteredintraditionalceremonies.

Undercustomaryrules,thecorpseandallpropertyofapersonwhodieswithouthaving

writtenawill(anintestatedecedent)passestothefamily.One’sFamilyiscustomarilydefined

as one’s lineage: “the extended group of lineal descent of a common ancestor or ancestress”

(Kludze 1983, pp 60). The head of the lineage appoints a “successor” to assume the estate,

rights and obligations of the decedent on behalf of the lineage.Only a legal will overrides

customarylaw,andfewGhanaianshavelegalwills.

Theapplicable customarylawvariesacrossethnicgroups,andeachtribaltraditionisan

intricatebodyofrules, obligations, andnorms.However,Ghana’scustomary legalregimesas

regards inheritances can be meaningfully divided into two broad categories:matrilineal and

patrilinealtraditions:matrilinealandpatrilineal.

2

Islamicmarriagehasa'special'status,withtheQurandefiningmarriageandinheritancerules.Theseletaman

marryuptofourwomen,letonlymeninheritcertainassets,etc.Islamiclawshapesthecustomarytraditionsof

Muslimtribes,whichpredominateinthefarnorth.Consensualunions,withneitheran

ordinancemarriagenora

marriage under tribal custom, provide no inheritance rights whatsoever.A deceased common law spouses’

propertyrevertstotheirfamilies.Inter‐vivostransferstoacommonlawspousearesubjecttolegalchallenge.

6

Figure1:RegionalmapofGhanadepictingthe10regions.

Thematrilinealsocieties arefoundinthesouthwestregions(Ashanti,CentralandWestern),

and parts of Northern region. Patrilineal groups are in the southeastern (Greater Accra and

Volta)andtheUpperregions.

7

2.1 MatrilinealCustomaryInheritanceNorms

As figure 1 shows, the Akans (Ashanti, Central and Western regions; and the Lobi, Tampolese

and Baga (Northern Ghana) all use variants of matrilineal customary law. The Akans,

constituting about 48% of Ghana’s population and the largest tribe

3

, are often considered an

archetypicalmatrilinealculture.Undermatrilinealtradition,afamily’scontrollingspiritpasses

fromgenerationto generationonlythroughfemalebloodlines,fromwhomAkanchildrenare

believedtoinherittheir“fleshandblood,”i.e.,theirsourceofexistence(Bleeker(1966).Family

ties,tracedonlythroughfemaleancestors,defineone’sextendedfamily,lineage,ormatriclan.

4

Inamatrilinealtribe,oneisthusrelatedbybloodtoone’smother,fullsiblings,andhalf‐

siblings by a common mother (uterine half siblings), but not to one’s father nor to any half‐

siblings by a common father.Thus, children belong to their mother’s lineage, but not the

father’s.AtraditionalAkanmalethusfeelsbloodkinshiptohis mother'sbrother(w

ɔ

fa:pron.

wə‐fa),butatmostaweakconnectiontohisfather'sbrother.

An Akan male does not consider his children to be his blood kin.His closest blood

relativeinthenextgenerationishissister’sson,andthismaternalnephew(w

ɔ

fase:pron.wə‐

fa‐si)ishispresumedheirifhisbrotherspredeceasehimandhediesintestate.BecauseAkan

traditional rules revert a married couple’s acquired property to the decedent’s matrilineal

extended family (Awusabo, 1990), a widow and her children can be left destitute by the

husband’sdeath.Shemustthuslooktoherbrothersforsupport;andherchildrenmustlookto

theirmaternalunclesforbequests.Theexpectationofinheritinga maternaluncle’swealthis

oftensaidtobluntanAkannephew’sincentivestoacquirehumancapitalorseekajob,andis

capturedneatlyinan

oldAkanadage“w

ɔ

faw

ɔ

hontimenyeegyuma”(Lit.“Ihavearichuncle;

Idon’tneedajob”).

Notethatamatrilinealdefinitionofwhois,andisnot,inone’sfamilydoesnotimplya

matriarchalpowerstructureoverthatfamily.Chiefsandtriballeadersinmatrilinealtribesare

almost

always male, and the leaders of matrilineally defined extended families are almost

3

TheAkantribecontainssub‐groups,definedbytheirmostlymutuallyintelligibledialects.Thelargestgroupsare

theAsante,AkuapemTwi,Akyem,Brong(intheBrong‐Ahaforegion),FanteandAgona.

4

One’smatriclanispreciselythosewithwhomonesharesidenticalmitochondrialDNA.

8

alwaystheirhigheststatusmales.

5

Figure 2 illustrates how a matrilineal controlling spirit flows from generation to

generation.Themembersofamatriclan all share acommonfemaleancestor,towhomtheir

mothersaretiedbyfemale‐to‐femalelinesofdescent–showninblack.

Figure2:MatrilinealDefinitionofBloodRelatives

A circle represents a female and square represents a male. One’s lineage consists of all descendants

(white)ofallcommonfemaleancestorsthroughfemalebloodlines.Childrenofbothgendersbelong

to their mother’s, but not their father’s, lineage. One is thus related to one’s mother, but not one’s

fathers,and

toallmembersofone’smother’slineagebutnottomembersofone’sfather’slineage.

2.2 PatrilinealCustomaryInheritanceNorms

Themainpatrilineal societiesinGhana aretheGatribe(intheGreaterAccraregion),theEwe

tribe(intheVoltaregion),andtheDagombaandNanumbatribesintheUpperEastregion.Ina

patrilinealtribe,afamily’scontrollingspiritpassesfromgenerationtogenerationonlythrough

malebloodlines,andtheseconnectionsdefineone’sextendedfamily,orpatriclan.

6

Underpatrilinealcustom, one’sextendedfamily thusincludesone’s childrenaswell as

one’s father, siblings, half siblings by a common father, aunts and uncles, and so on. One’s

5

MatrilinealdefinitionsofethnicityarenotunknownintheWest.Forexample,oneisJewishbybirthonlyifone’s

motherisJewish.A Jewishfatherdoes not count.As withthe Akan,amatrilineal definitionof family didnot

implymatriarchalcontrolofancientHebrewtribesor kingdoms.Many

Americanaboriginalculturesalsousea

matrilinealdefinitionofbloodkinship‐theCherokee,Gitksan,Haida,Hopi,Iroquois,Lenape,andNavajo,among

others.

6

One’spatricianispreciselymalerelativeswithYchromosomesidenticaltothatofone’sfather,plustheir

immediatechildrenofbothgenders.

9

sistersandhalfsistersbyacommonfatheraremembersofone’slineage;buttheirchildrenare

not.Thisisbecause theybelongtothatsister’sorhalf‐sister’shusband’sfamily.Likewise,one’s

grandchildren through a son belong to one’s family, but grandchildren though a daughter

belongstotheirfather’sfamily,andarethusnotone’sbloodrelatives.

Figure3:PatrilinealDefinitionofBloodRelatives

A circlerepresents a femaleanda square represents a male.One’s lineageincludesall descendents

(white)ofcommonmaleancestorsthroughmalebloodlines.Childrenofboth gendersbelongtotheir

father’s,butnot their mother’s, lineage.Oneis thus related toallmembers of one’sfather’slineage

butnot

tomembersofone’smother’slineage.

In a patrilineal society, children inherit their father’s estate, and widows thus look to

theirchildrenforsupportseeOllennu(1966)fordetails.Figure3distinguishesmembersofa

commonpatriclan,inwhite,frompersonsnormallyconsideredrelativesinWesternsocieties,in

grey,whodonotcountasbloodrelativesin

apatrilinealculture.

2.3 CriticismsofTraditionalInheritanceNorms

AkeydifferencebetweenFigures2and3isthatmatrilinealculturesdonotnumberadeceased

man’s widow or children among his blood relatives.Western observers thus often see

patrilinealtraditionsasmoresupportiveofwidowsandchildren.

However, patrilineal norms also appears superficially more familiar to Western

observers, who may neither understand nor appreciate the support provided by brothers,

10

maternal half‐brothers, and maternal uncles in matrilineal societies. A widow with a wealthy

brotherinamatrilinealtribemaybemuchbetteroffthana widowinapatrilinealtribewhose

poorhusbandleftherchildrenameagerestate.Whichsystembetterprovidesforwidowsand

orphans on average is thus an empirical question, and may not even be subject to broad

generalization.Some communities might apply a given set of traditional norms with more

generositytowidowsandchildrenthanothers.

Publicized cases of impoverished widows and children in matrilineal tribes, buttressed

by survey evidence assembled by women’s advocacy groups and Christian organizations,

repeatedlymadethepovertyofwidows’andtheirchildrenapublicpolicyissueinthedecades

subsequenttoGhana’s1957independence.Widow‐headedhouseholdsthroughoutGhana,but

mostevidentlyinruralmatrilinealhomes,werehighlightedashavingextremelevelsofpoverty

– due, in part at least, to traditional inheritance norms. Intestacy law reform attracted

increasingdebate,butactualreformwasslowtocome.Onereasonforthisdeadlockwasthe

absence of a viable reform proposal; another was doubtless the legislators’ fear of providing

fodderfortribalchauvinists.

The case for reform grew to encompass several arguments.The most direct was the

caseforconjugal(nuclear)familiesretainingall ormostofadeceasedspouse’sassetstoshield

widowsandtheirchildrenfrompoverty.

But the case for reform went beyond such welfare considerations. Of at least equal

importance were the incentives inheritance customs

created for wealth accumulation by

individualsandconjugalfamilies.Especiallyinmatrilinealtribes,aplausiblecasewasmadethat

thetransferofaconjugalfamily’sassetstothedeceasedman’smaternalnephewundermines

the incentives of the husband and wife to acquire skills, exert effort, and accumulate assets;

andtoblunt

thesameincentivesinmaternalnephews.

Anotherproblemconcernsthealienabilityofassetspassed to a lineage.No individual

personownstheseassets,andtheconditionsunderwhichtheycanbeboughtandsoldarestill

murky.A lineage is a corporate entity, but often lacks necessary legal titles because

of the

difficulties of deeding an asset to multiple owners. For example, throughout Ghana, lineages

ownlandandotherassetsthat havenovaluebeyondtheirprimaryuse.Theseassetscannot

11

serve as collateral for a loan; and improvementstothemare the property of the lineage, not

theindividualwhopaysfortheimprovements.Individualsthushavescantincentivetoaddto

thevalueofsuchassets.Traditionalinheritancesystemsmightthusexplain,inpartatleast,the

failure of many sub‐Saharan countries to formalize titles to land and capital assets (De Soto

2000).Reforms that keep assets from reverting to lineages might ultimately spread clearer

propertyrightsandthusimproveallocativeefficiency.

It is possible to contract around these problems.But lineages must solve a collective

action problem to act in concert. Individuals can nullify traditional inheritance norms with a

legalwill.However,mostGhanaiansdieintestate.

7

Highilliteracyrates,alackofaccesstothe

formallegalsystem,andthe fearofretaliationbytheextendedfamilydoubtlessallplayarole.

Malesinmatrilinealhouseholdscanattempttoprotecttheirwivesandchildrenwithinter‐vivos

transfers;butthesecanbeundone–eitherlegallyorbysocialpressure.

In fact, actual monetary transfers may also go in the opposite direction: e.g., the child

pays money to the father. La Ferrara (2006) finds Akan (matrilineal) sons transferring more

money to their fathers than do otherwise similar sons in patrilineal cultures, especially if a

paternalaunt’ssonresideswith,orlivesinthesamevillageasthe,father.LaFerraraconcludes

thattheincreasedtransfersfrom Akansonsarepartiallyattemptstoinfluencetheirfathersto

directlandgiftstothem,ratherthantothefather’snephew.

3. LegalReforms

Bythemid‐1970s,acaseforcomprehensivereformwaswidelyacknowledged.Forexample,in

1979,theConstitutionoftheThirdRepublicofGhanaproclaimedinitsAarticle32(Woodman,

1985):

§2 No spouse may be deprived of a reasonable provision out of the estate of a spouse,

whetherthe

estatebetestateorintestate.

§3 Parliamentshallenactsuchlawsasarenecessarytoensurethateverychild, whetheror

not born in wedlock, shall be entitled to reasonable provision out of the estate of its

7

Inoursurveyofwidows,only8%reportedthattheirspousehadalegalwill.

12

parents.

Parliament,ofcourse,didnosuchthing,andtheConstitutionwasabolishedinamilitarycoup

laterthatyear.Themilitaryjuntareiteratedthetwopledges;buttooknoimmediatejudicialor

legislativeaction.

On June 14 1985, the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), the ruling military

junta, proclaimed four interrelated reforms that, in theory at least, radically reformed the

ground rules for intestate inheritances.These were: the Intestate Succession Law (PNDC Law

111,1985),theCustomaryMarriageandDivorce(Registration)Law(PNDCLaw112,1985),the

Administration of Estates Law (PNDC Law 113, 1985), and the Head of Family Accountability

Law(PNDCLaw114,1985).AllfourinitiativeswerejustifiedinanaccompanyingMemorandum

asreflecting“thegrowingimportanceofthenuclearfamily”relativetotheextendedfamily.

3.1TheIntestateSuccessionLaw(PNDCLaw111,1985)

The most important of these for our purposes, and for rebalancing customary inheritance

norms against the needs of surviving members of the conjugal family, is the Intestate

SuccessionLaw(PNDC)Law111,1985–hereinafterLaw111.Indeed,ithasbeencharacterized

asthemostradicallegislativereformevermadeintheprivatelawofGhana(Woodman,1985).

Wethereforepausetoelaborate.

AlthoughLaw111isphrasedtobegender‐neutral,itwasseenasavictoryforwomen,

andsohailedbywomenadvocacygroups.Thelawallowsawidowandherchildren–hitherto

completely denied rights to

the nuclear family’s assets under matrilineal norms – to be the

primarybeneficiariesofthedeceasedhusband.

ThewritofLaw111isrestrictedintwoways.First,thelawappliesonlytopropertynot

disposedofina legalwill.BecausemostGhanaiansdieintestate,thisrestrictionisnot

thought

ofparamountimportance.Moreimportantly,Law111 doesnotapply tolineageproperty –a

conceptunfamiliartomostWesternobservers.Muchland,andofothersortsofpropertytoo,

belongstoalineage,nottoanyindividual.Suchpropertyassignedtothedeceasedhusbandfor

use during his life automatically reverts to the lineage upon his death; and, in a matrilineal

13

tribe,mostlikelypassestooneormoreofhismaternalnephews.

8

Law111doesapplyonlyto

self‐acquiredproperty–assetsthedeceased,orhisnuclearfamily,purchasedorcreatedduring

his life.Because the husband is typically considered its sole owner, a conjugal family’s self‐

acquiredpropertyvirtuallyalwaysrevertedtoadeceasedhusband’slineage.Awoman’srole,in

whatever form, was rarely recognized.

The lawmakers explicitly referred to this issue in an

accompanying Memorandum, which explained the reforms thus: “It is the right that the

husbandwithwhomthewomanhaslivedandwhomshehasprobablyserved,isthepersonon

whosepropertyshemustdependafterhisdeath.”

Law 111 partitions a decedent’s assets into two categories:household chattels and

residue assets.Household chattels include all household belongings in regular use: clothes,

furniture, appliances, a family non‐commercial vehicle, farm equipment, and household

livestock. All household chattels automatically devolve to the conjugal family. Residue assets

includebusiness‐relatedandinvestmentassets:businessproperties,commercialvehicles,non‐

primary residential properties, bank accounts, savings, and investments.Residue assets are

distributed to members of the decedent’s conjugal family and extended family according to a

set of formulae set forth in sections 5 – 8 and 11 (Articles 1 and 2) of Law 111.Table 1

summarizesthese.

The first row of the table sets out a baseline case, where the decedent has surviving

relatives in all relevant classes.In this example, section 5 stipulates that 3/16 of the residual

goestothespouse,9/16tothesurvivingchildren,and1/4 tothelineage;thatlast to

besplit

equally between the parents and those entitled to inherit under the decedent’s traditional

norms.

8

Lineage property, which encompasses the extended family‐owned assets, is distinct from tribal property. A

typical example of tribal property is the communal land “owned,” in principle, by the paramount chieftaincy

(called the stool) in trust. Individuals have rights to use the land for farming, or for some other commercial

activity,byvirtueofmembershipofthetribebutonlywiththeconsentfromthestoo1(i.e.,thechief).Tribaland

lineagelandareessentiallyinalienablebecauseofa“tragedyoftheanti‐commons”problem.Allmembersofthe

currentlylivinggenerationofthelineageortribeareconsideredcustodians

forpropertythatalsobelongstoall

pastandfuturegenerations,andthuscannotbesoldwithouttheexplicitconsentofalllivinglineagemembers

pluscountlessdeceasedandunborngenerationsofthelineage–aconditionprospectivebuyerscanbecertainis

neversatisfied.Sagasaboundofforeignersthinkingthey

havepurchasedsuchpropertywhentheyhavenot.

14

Table1.ResiduePropertyDistributionunderIntestateSuccessionLaw(PNDCLaw111,1985)

The decedent’s residue property (property not classified as household chattels or lineage property) is

apportionedtorelativesbyoneofthefollowingformulas.Residueassetsincludebusiness‐relatedand

investment assets: business properties, commercial vehicles, non‐primary residential properties, bank

accounts, savings, and investments.The applicable formula depends on which of

the decedent’s

relativessurvive.

Livingconjugal&

extendedfamilymembers

ShareofresidueLaw111assignsto:

Spouse Children Parents Lineage

a

State

b

Ifallsurvive 3/16 9/16 1/8 1/8 0

Nolivingspouse‐ 3/4 1/8 1/8 0

Nolivingchildren 1/2‐1/4 1/4 0

Nolivingspouseorchildren‐‐3/4 1/4 0

Nolivingspouse,children,orparents‐‐‐1 0

Nosurvivingknownrelatives‐‐‐‐1

a. Tobedistributedinaccordancewiththetraditionsofthelineage.

b.Intrustforanypersonsubsequentlyidentifiedassufficientlyclosetodeceasedtobealegitimateheir.

Theotherrowsmodifythebaselineformulaintheabsenceofsurvivingheirsofoneor

more sorts.For example, the second line shows that if the decedent has no living spouse –

becauseofeitheradivorce or thespouse’spriordeath–whatwouldhavebeenthe spouse’s

share passes instead to the children.If the decedent has neither a living spouse nor living

children, what would have been their shares passes to the decedent’s lineage – with the

parentsreceiving3/4oftheresiduepropertyandtheremaining1/4distributedbythelineage

in accordance with its traditional norms.In the rare event of the decedent having no known

relativesofanykind,the residue property goestothestateintrust,andcansubsequently be

disbursedtoone“whowasmaintainedbythe intestateorwithwhomtheintestatewasclosely

identified”, should such a person be found to exist.Thus, someone who lived with, or was

related in some sufficiently close way to, the decedent can seek a court order to inherit a

portionoralloftheestate(seeWoodman,1985).

Over the more than a quarter of a century since Law 111 took effect, anecdotal

evidence and reports by women’s advocacy and religious groups concur that the law is not

widelyfollowed.Themost likelyreasons for this are a lack of information about the law,the

15

inaccessibilityoftheformallegalsystemtomanypeople,andaveryrealfearofreprisalsfrom

thelineageforviolatingcustomarylaws.Manyfamilies, especiallyinruralareas,knowonlythe

customary laws of their tribes. Moreover, government officials in these areas are often

reluctanttoenforcetheformallawandapplysanctionswhenitisviolatedbecausethesesame

officialsareoftenalsochargedbytheirtraditionalcommunitieswithupholdingcustomarylaws.

The formal law is a written body of knowledge, while customary law is passed along

orally, and thus more accessible to illiterate people.If legislation from Accra conflicts with

tribalcustom,thelatterusuallywinsout.A2007studybytheGhanaofficeoftheInternational

Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA, 2007) shows about 40% of survey respondents –

interviewed in Accra (the capital and mainly patrilineal), Kumasi (the second largest city and

predominantlymatrilineal),andKoforidua(amixtureofinheritancesystems)–hadeithernoor

an erroneous knowledge of Law 111 – with these responses much more frequent among

peoplewithlittleornoeducation.Amere3%hadacompleteknowledgeofthelaw.

9

TheFIDA

studypursuestheissuewiththefewrespondentswhoknewofthelaw.Eventhesefindactual

useofLaw111toberestrictedbymultiplebarriers.

Widows often lack the financial resources to mount a legal challenge, and are often

overwhelmedandfrustratedbyacumbersomelegalprocedure.Thewidowmustpetitionfora

LetterofAdministrationfromthecourtstogainstanding–andthisrequirestheapprovalofthe

head of the decedent’s lineage, typically a contending party. In addition, she must obtain

competentlegal guidance to executethisdocumentpreciselyinaccordance with the letter

of

Law111,foranyproceduralerrornullifieshercase.Addedtotheexpenseoflegaladviceisthe

cost of the decedents funeral and burial rituals, which the widow must pay in their entirety

shouldshecontestthecustomarylaw.Thesecostsareeasilyprohibitivegiventheimportance

of

elaborate funerals in Ghanaian cultures. The community typically expects a grand funeral,

andthisisonlyfinancialpossiblewiththesupportofthedecedent’slineage.

Perhaps even more daunting than all of these financial costs are the social costs a

9

Recenteducationdrivesandsocialawarenessprogramsareactivelyworkingtoinformpeopleoftheirrights

undertheformallegalsystem.Prominentamongthemare:theMinistryofWomenandChildren,theFederacion

InternaciondeAbogadas(FIDA,knowninGhanaastheInternationalFederationofWomenLawyers),the

Women’sInitiative

forself‐Empowerment(WISE),andWomeninLawandDevelopmentinAfrica(WiLDAF).

16

widow risks by challenging traditional norms. The repercussions from overtly disregarding

deeply rooted tribal custom can be devastating.This messy and divisive process, with all its

attendant costs, conflicts, and adverse consequences, can readily be avoided if the decedent

leftawill.ButtheFIDA(2007)studyreportsthatwomenareunlikely topresstheirhusbandsto

writeawill.Indeed,amajorityofinterviewedwidowsdidnotknowiftheirspouseshadawill,

and never discussed writing a will with him. This response from one respondent, when asked

why,capturesthegeneralsentiment:

“Icouldneverask[myhusband]ifhehadawillornot…..IfIasked,hemayeventhinkI

amplanningtokillhimsoIcantakehisassets;oraccusedmeofbeingawitchor

somethingbad.Hemayevenaskforadivorce.”

3.2 Survivors’(Pension)BenefitsundertheChildren’sAct560,1998

A second comprehensive reform to Ghanaian inheritance laws developed in stages, and

provides a wealth of government data pertaining to middle and high income Ghanaian

households, whose survey participation rates tend to be very low in any event. The Social

Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) runs the sole government‐sponsored pension

annuity program for retirees. Should the contributor die before his accumulated benefits are

fullydisbursed,60%oftheremainingbenefitspasstothedecedent’schildrenunder18.Each

contributor apportioned the remaining 40% to one or more chosen heirs. This reflects a

sequence of reforms, but primarily the Social Security Act (PNDC Law 247, 1991) and the

Children’sAct(Act560,1998),hereinafterLaw247andAct560,respectively.

Law 247 designates the permissible choices open to members of patrilineal versus

matrilineal cultures, and is summarized in Table 2.Thus, Law 247 prohibits a member of a

patrilineal culture from listing a sister’s son as an heir, and forbids a member of a matrilineal

culture from listing a father’s father or father’s brother as an heir. But in both cases, one has

theoptionofeitheradheringtothetraditionalnormsofone’slineageorbequeathingbenefits

toone’sconjugalfamily.

A pension contributor’s choice of heirs is confidential, buried in government files, and

17

available to interested parties only after the contributor’s death.This theoretically lets one

defy customary inheritance norms by bequeathing one’s accrued pension wealth to one’s

conjugalfamily,notone’slineage;withno‐onetoknowuntilwellafteroneissafelydead.

Thesocialsecuritysystemdatesback(atleast)to1946,whenChapter30ofthePension

Ordinance of 1946 provided government pensions for certain public sector employees, a

scheme that became known as CAP30. A mor e general social security system began with the

militarygovernmentofthetime,theNationalRedemptionCouncil,decreeing(NRCD127,1972)

the expansion of a previous Parliamentary Act 279 to establish a Provident Fund topayevery

formalsectorworkeralump‐sumupon retirement.In1991,another militarygovernment,the

ProvisionalNationalDefenceCouncilproclaimed theSocialSecurityAct(PNDCLaw247,1991),

hereinafter Law 247, under which the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) is

made the sole government‐sponsored pension system.The system resembles standard

Westernpensionsystemsinsomeways,butdeviatesmarkedlyfromtheminothers.Ourdata

covermuchoftheperiodwhenLaw247wasineffect.

10

Table2.Schedule45oftheSocialSecurityAct(PNDCLaw247,1991)

UnderLaw247,onlycertainpersonsareeligibletobelistedasheirstoadeceasedbeneficiary’sSSNIT

pensionaccruals.Differentchoicesetsareoffered tomembersofmatrilinealversuspatrilinealtribes.

Decedent’sTraditionalNorm Patrilineal Matrilineal

Mother,father allowed Allowed

Husband allowed Allowed

Wife,son,daughter allowed Allowed

Brother,sister allowed Allowed

Father’sfather allowed Prohibited

Mother’smother prohibited Allowed

Father’sbrother allowed Prohibited

Mother’sbrother prohibited Allowed

Mother’ssister prohibited Allowed

Sister’sson prohibited Allowed

Sister’sdaughter prohibited Allowed

10

AnewNationalPensionsAct(Act766)wentintoeffectonJanuary2010andexpandstheschemeunderLaw247

toincludevoluntarycontributionsfromself‐employedpersonsandindividualsintheinformalsector.Social

SecurityfortheinformalsectorwillbeadministeredbytheSSNITInformalSectorPensionFund.

18

Likemanygovernmentpensionschemes,theSSNITis apay‐as‐you‐gosystem:formal‐

sector workers’ current contributions fund benefits paid to pensioners. Law 247 requires that

all employers contribute 17.5% of their base salaries to the fund.This appears as a 5%

deduction from the employee’s monthly pay check, and is matched by a 12.5% employer

contribution invisible to the employee.Act 766 now allows the self‐employed to join the

systembymakingthefull17.5%contribution.

Also like many other systems, the SSNIT is a defined benefit system. The minimum

annualpensionbenefitis50%oftheaverageofthecontributor’shighestthreeannualsalaries

earned in the twenty years prior to retirement. The benefit rises by 1.5% of average of that

average for each additional year of work and contributions to the fund. So, theoretically,

anyone who retires at age 60, having contributed for 40 years to the fund, merits a pension

equalto80%ofaverageearningsintheretiree’sthreemostprosperousyears.

11

The major difference between most other pension systems and the SSNIT it its fixed

term:paidupcontributorsareentitledtoexactly144consecutivemonthlybenefitpaymentsin

retirement, no more and no fewer.Under Law 247, an individual becomes entitled to full

pensionbenefitsaftercontributingtotheschemefor240monthsandattainingtheageof60,

the mandatory retirement age.

12

The retiree then receives a monthly pension for the next 12

years.Whentheretireeturns72,thebenefitterminatesandtheretireemustrelyonrelatives

orsavings.Individualsmayoptoutof thisdefaultscenarioand receive25%ofthepayments’

present value as a lump‐sum upon

retirement, and the other 75% as monthly payments over

thenext12years.

Ifthecontributordiesbeforeage72,thepresentvalueoftheremainingpaymentsthe

contributor would have received, computed at the treasury rate over the same period, was

thenpaidtotheheirsthecontributorchosefrom

theoptionsmadeavailableinTable2.

13

The

largestsubsequentchangetothissystem,theChildren’sAct(Act560,1998)of1998,mandates

11

Earlyretirement,startingfromage55,withreducedpensionpaymentsispermittedunderLaw127.Individual

whoretirebeforeage60lose7.5%oftheirage60retirementbenefitforeachyearsuntiltheir60

th

birthday.

Peopleinhigh‐riskoccupations,suchasmining,areexemptedandcanretireat55yearswithfullpension.

12

Ifacontributorfallsshortoftherequired240months,thetotalcontributionsplusinterestathalftheT‐Billrate

isrefundedasalumpsumatretirement.

13

BenefitsarediscountedattheloweroftheprevailingTreasurybillrateand10.

19

thattheSSNITpay60%ofsuchsurvivorbenefitstothecontributor’sminorchildren(age18or

younger).In theory, whenever the SSNIT receives a procedurally complete claim, with all

necessary supporting documents (e.g., death and burial certificates), it should investigate the

familytoascertainwhetherornotthedecedenthasminorchildrennotlistedasbeneficiaries.

In practice, the SSNIT lacks the resources to do this, and merely ascertains the validity of the

submitted claim. The remaining 40% of the survivor benefit is then disbursed to the

beneficiaries the decedent selected from the appropriate column in Table 2, in the selected

proportions.

AnothermajordifferenceisthatGhana’sgovernmentsponsoredpensionprogramwas,

until very recently, restricted to formal‐sector employees.Workers in the informal sector –

subsistence agriculture, fishing, roadside stands, etc. – are not covered.

14

Some 80% of

Ghanaiansworkintheinformalsector‐subsistenceagriculture,fishing,roadsidestands,petty

trading,andthelike(Heintz,2005).SSNITdatathuspertainonlytomiddleandupperincome

Ghanaians.WethereforeusebothSSNITdataandsurveysofinheritancepatternsamonglow‐

incomeGhanaianstogainabroaderpictureofthecurrentsituation.

4. DataandEmpiricalStrategy

4.1 SurveyDataDescriptiveAnalysis

Wesurvey322widowslivinginfourvillagesinSouthernGhana:BortianorandIngleshiAmanfro

are both predominantly patrilineal, and in the Greater Accra Region; Abura Dunkwa and

NyankomaseAhenkroareintheCentralRegionandmostlineagestherearematrilineal.

Potential survey participants were identified with the help of a town or village council

member, a town leader or the traditional chief, whose approval were sought for our team of

researcherstoconductthesurvey.Householdswererandomlychosen,andthequestionnaires

were administered to an adult person in the house, in private. Because visits to randomly

selected seemingly more

affluent households in the urban areas generally yielded no

responses, our final data consist mostly of very low‐income respondents, though not the

14

Recentreforms(Act766,2008)mandatethattheSSNITorganizetheInformalSectorSocialSecurityFund,which

activelyencouragesinformalsectorworkerstosignupandsavefortheirretirement.

20

poorest of the poor living rough. About 50% of our respondents report no formal education,

and25%reportedthesamefortheirspouses.Theaverageis5yearsofformaleducation.Only

5.2%reportabankaccount(singleorjoint),though26%haveotherpersonalassets.Overhalf

nonethelessreportcontributingdirectlytotheconjugalfamily’swealth.

The survey data contain information to assemble a profile of each respondent’s age,

education level, inheritance system, years married, children (by spouse), minor children; and

marriage type (polygynous or monogynous). Our youngest respondent was 20 and our oldest

was93.ConsistentlywiththeethnicdistributioninGhana,about48%reporttheirtraditional

custom as matrilineal. Respondents also provided information to let us assemble similar

profiles of their spouses.Spouses’ profiles appear similar, though they are slightly more

educated–about8yearsofformaleducation.

A key part of our analysis is to gauge how respondents’ information about the law

shapedtheownershipstructure of thefamilyassets(i.e., individually ownedorjointly),which

law was applied in the distribution of the assets when a spouse died, and the welfare of the

family after the death. We therefore ask widows an additional set of questions.Nearly 47%

reportpriorknowledgeofthelaw,attheir marriage orbeforethedeathoftheirspouse.But

only3.2%ofwidowsreportitsuseintheircases.Rather,justover7.4%reporttheirdeceased

spousehavingawillandover75%reporttheestatehavingbeendistributedinaccordancewith

traditional norms. The remaining 14% did not know which rule was employed, or reported

usingareligious‐basedprincipletodivideuptheestate(e.g.,Muslim).Almost46%reportbeing

dissatisfiedwiththedistribution.

To assess widows’ economic and social status, we ask respondents to compare their

situations in the years immediately before versus after their spouse’s death. Because they

virtually all dwell entirely in the informal economy, questions about monetary income do not

capturetheir economicsituations. Wethereforeaskthemtoratetheireconomicsituationsor

opportunities, defined as access to financial services (formal or

informal), health care for

themselves and their children, and educational opportunities for their children. Access to

financial services in this context means an expectation of being able to borrow money in a

pinch from a financial institution, or from the head of the lineage or its more prosperous

21

members. Health care and education typically entail small informal monetary outlays. Thus,

obtaining needed medical care and clothing and provisioning children for school require cash

outlaysthat,inasubsistenceeconomy,typicallyrequireeconomicsupportfromone’slineage.

We are also interested in whether or not widows, if they attain better financial

situations than traditional law prescribes, encounter tension with their lineages, or those of

theirhusbands.Wethereforealsoaskeachwidowtocompare thequalityofherrelationships

withherspouse’sextendedfamily,beforeversusafterhisdeath.

Finally, we are interested in how divergent formal and customary laws affect welfare.

Wethereforeaskedwidowsquestionsabouttheireconomicpositionstoassesshowwelltheir

traditional support networks performed.Here, quantitative assessment is tricky.Previous

work(e.g.,Awusabo‐Asare,1999)findsthatpoorvillagers,suchasthoseweinterview,tendto

report their economic situation as very bad, leaving little variation to study.It is therefore

necessary tointroduceanorm,towhichtheycan compare themselves.However,acommon

norm is inappropriate because different lineages have markedly different capacities to help

theirlessfortunatemembers.Somelineagesincludegovernmentofficials,police,formalsector

workers, émigrés, or others, whose formal or informal income can be redistributed to needy

relations.Somelineagesbelongtotribeswithmineral rights,whoserevenue streamscanalso

be redistributed from chiefs to lineage heads and then to needy widows. However, most

lineages have few or no such resources, and genuinely cannot provide more than minimal

subsistencesupport.

Toextricateinformationaboutwelltraditionallineagesupportsystemsfunction, weask

eachwidowtoconsiderthefinancialcapacityofthelineageinquestiontosupport peoplesuch

as herself. With this benchmark in mind, she was then asked if she received any lineage

support; and if so, whether this was less than, about in line with, or more than that capacity

allowed. A study of “mixed marriages,” in which one spouse has a patrilineal tradition and

anotherhasamatrilinealtradition,wouldhavebeenespeciallyinstructivehere.Unfortunately,

interlineage marriages within our sample are extremely rare,

as Table 4.Roughly nine in ten

Ghanaians marry within their lineage tradition.Studying interlineage marriages would be

interesting,butTable4revealsoursampleofthesetobeverysmall.

22

Table4:MarriagePatterns:Withinversuscross‐lineagemarriages

Numbers ineachcellarenumbersofrespondentsofhorizontal lineage classificationwhose spouses

are in vertical lineage classification. Percentages to the right of these numbers are percentages of

respondents,percentagesbeloweachnumberarepercentagesofspouses.

Spouses’traditionallineage

Matrilineal Patrilineal Total

Respondents’

traditionallineage

Matrilineal

145 88.4% 19 11.6% 164

93.5% 11.4 50.9%

Patrilineal

10 6.3% 148 93.7% 158

6.5% 88.6% 49.1%

Total 155 48.1% 167 51.9% 322

Table 5 highlights differences in means by respondents’ inheritance options. Panel A

compareswidowswhoknowofLaw111torespondentswhodonot;whilePanelcomparesby

thedeceasedspouse’slineagetype.

Unsurprisingly, Panel A shows that knowledge of Law 111 correlates positively with

education, for both the respondents and spouses; and the educated are more likely to be in

monogamous marriages.Confirmingtheimportanceof financial incentives,knowledgeofLaw

111isalsogreateramongrespondentswhoreport contributingmorewealth totheirconjugal

families.

Widows who had knowledge of the law were significantly more likely to have settled their

deceasedspouse’sestateunderit.In fact,no‐oneindicatednoknowledgeofthelawpriorto

their spouse’s death made use of the law in dealing with the estate – suggesting that

proponents of the Law’s greater usage might consider more energetically distributing

information at the time

of a spouse’s death or serious illness.More surprisingly, though

consistently with previous studies such as FIDA (2007), Panel A shows that about 70% of

respondents with a prior knowledge of Law 111 nonetheless settled their deceased spouses’

estatesinaccordancewithtraditionallineageorreligiouscustoms,afigurethatis

onlyslightly

lessthanthatforrespondentswithnopriorknowledgeofLaw111.Presumably,muchorallof

theestatespassedtothelineageinbothcases.

23

Table5.MeansurveyresponsesbyknowledgeofLaw111

PanelA.Meansurveyresponses,bywidow’sknowledgeofLaw111,whichextendslimitedformal

legalinheritancerightstoconjugalfamiliesregardlessofcustomarylaw

KnowledgeofLaw111

Yes No Difference

RespondentProfile

Age(years) 52.9 56.6‐3.7 **

Education(yrsofformaleduc) 5.1 2.8 2.3 ***

Monogamyatmarriage(%ofwidows) 82.4 65.5 16.9 ***

Monogamyatspouse’sdeath(%ofwidows) 79.1 66.8 12.2 **

InformationonSpouse

Yearsmarried 23.8 23.9 0.1

Spouseeducation(yrsofformaleduc)

8.0 5.5 2.5 ***

Customary/Islamicmarriage(%) 82.6 85.0‐2.4

Noofchildren(withspouse) 4.6 4.8‐0.2

‐aged<18(atspousedeath) 1.8 1.9‐0.1

OwnershipofAssets

Jointaccountw/spouse(%ofwidows) 4.7 5.8‐1.1

Percentcontributedtofamilyassets(%) 27.6 18.4

9.2 ***

PersonalAssets(%ofwidows) 29.7 23.8 5.9

Inter‐vivosfromspouse:Asperabilityorbetter(%) 34.2 27.1 7.1 *

DistributionofAssets

Will(%) 12.8 2.9 9.8 ***

PNDCLaw 6.1 0.6 5.5 ***

Customary/Islamic 67.1 87.3‐20.2 ***

%dissatisfiedwith

distribution 36.2 47.9‐11.7 **

WelfareafterSpouseDeath

Economicsituation(%worseoff) 55.7 69.9

‐14.2 ***

Relationshipwithin‐law(%worse) 22.8 16.7

6.1 *

LineageFinancialSupport

Own:Asperabilityorbetter 31.5 31.2 0.3

Spouse’s:Asperabilityorbetter

14.1 12.1 2.0

Difference(ownminusspouse’s) 17.4 ***19.1 ***

LineageEmotionalSupport

Own:Asperabilityorbetter 49.7 52.6‐3.9

Spouse’s:Asperabilityorbetter 25.5 27.2‐1.7

Difference(ownminusspouse’s) 24.2 ***25.4 ***

24

PanelB.Meansurveyresponses,bycustomarylawapplicabletodeceasedspouse

Thecustomarylawofthedeceasedhusband’slineagedeterminesherinheritancerights.

Spouseinheritancecustom

Matrilineal Patrilineal Difference

RespondentProfile

Age(years) 54.6 55.1 0.5

Education(yrsofformaleduc) 5.1 2.8 2.3 ***

Monogamyatmarriage(%ofwidows) 79.1 68.1 11.0 **

Monogamyatspouse’sdeath(%ofwidows) 80.4 65.3 15.1 ***

InformationonSpouse

Yearsmarried 24.5 23.2 1.3

Spouseeducation(yrsofformaleduc) 7.5

5.8 1.7 ***

Customary/Islamicmarriage(%) 85.1 82.6 2.5

No.ofchildren(withspouse) 4.2 5.3‐1.1

‐aged<18(atspousedeath) 2.1 1.6 0.5 ***

OwnershipofAssets

Jointaccountw/spouse(%ofwidows) 3.9 6.6‐2.7

Percentcontributedtofamilyassets(%) 26.1 19.4 6.6

***

PersonalAssets(%ofwidows) 34.4 19.3 15.1 **

Inter‐vivosfromspouse:Asperabilityorbetter(%) 28.4 32.3‐3.9

DistributionofAssets

Will(%) 9.7 5.4 4.3 *

PNDCLaw 5.2 1.2 4.0 **

Customary/Islamic 70.7 85.4‐14.7 ***

%dissatisfiedwithdistribution 45.1 40.1‐5.0

WelfareafterSpouseDeath

Economicsituation(%worseoff) 50.3 75.4

‐25.1 ***

Relationshipwithin‐laws(%worse) 27.7 12.0

15.7 ***

LineageFinancialSupport

Own:Asperabilityorbetter 31.6 31.1 0.5

Spouse’s:Asperabilityorbetter 13.5 12.5 1.0

Difference(ownminus

spouse’s) 18.1 ***18.6 ***

LineageEmotionalSupport

Own:Asperabilityorbetter 58.1 44.9 13.2 **

Spouse’s:Asperabilityorbetter 31.0 22.2 8.8 *

Difference(ownminusspouse’s) 27.1 ***22.7 ***

25

Knowledgeofthe formallawcorrelateswithabettereconomicsituationinwidowhood

overall. However, it has little traction in explaining the relative economic and emotional

support widows receive from their lineages versus those of their husbands.Widows

knowledgeable of the law obtain insignificantly better financial support both from their own

and spouses’ lineages than do widows unfamiliar with the formal law. Indeed, widows

unfamiliar with the law actually report insignificantly better financial and emotional support

from their spouse’s lineage, relative to their own. Across the board, widows’ own lineages

providemoresupport.

Panel B repeats the exercise, but partitions the data by respondents’ spouses’

inheritance tradition. Knowledge of the law is substantially greater among widows whose

husbands were from a matrilineal tradition – suggesting women’s and various organizations

have successfully reached more of those the law was specifically intended to empower.

However,PanelBalsorevealsbothmatrilinealdeceasedspousesandtheirwidowstobebetter

educated, perhaps also partially explaining their better familiarity with the formal law.

Matrilineal spouses’ widows are also more likely to have been in monogynous marriages; a

situationthatpresumablyimprovedtheirimplicitbargainingpowerwiththeirhusbandandhis

family. Matrilineal widows reported having fewer children with their deceased husband,

althoughaslightly largernumberoftheirchildrenwerelessthan18 yearsoldatthetimeshe

becameawidow.

Widows of matrilineal spouses, those least likely to inherit a deceased spouse’s assets

under customary law, nonetheless report having contributed more to

the conjugal family’s

wealth, and also having accumulated more personal assets. This might explain their small,

though insignificantly, greater dissatisfaction with the distribution of those assets after their

husbands’deaths.

It seems knowledge of Law 111 mitigates any adverse effects husbands’ matrilliny on

theirwidow.Matrilinealmen’swidowsknowledgeableaboutLaw

111reportlessdissatisfaction

with the distribution of the conjugal family’s assets (36% vs. 48% were dissatisfied). Perhaps

knowledge of the law strengthens their bargaining power within the traditional inheritance

process.

26

Finally,widowsofmatrilineal lineagemenreportinsignificantlybetterfinancialsupport

bothfromboththeirownandtheirdeceasedhusbands’lineagesthandowidowsofpatrilineal

men. Widows of matrilineal men also report better emotional support from both lineages.

Recall from Table 4 that 93% of matrilineal men’s widows are themselves from matrilineal

cultures,sostrongsupportfromthewidow’slineageisunsurprising.Butthefindingthattheir

deceased husbands’ matrilineal lineages also support them, even though their children from

suchamarriagearenotconsideredtheirs,suggeststhatmatrilineallineagesingeneralprovide

unexpectedlystrongtraditionalsafetynetsforwidows.

4.2 PensionBequestsDataDescriptiveAnalysis

To complement our survey data, which cover very low‐income Ghanaians, we utilize official

dataonindividuals’bequestinstructionsregardingtheirSocialSecurityandNationalInsurance

Trust (SSNIT) benefits. These data pertain only to Ghanaians with employment in the formal

sector–personsconsideredtobeofmiddletohighsocioeconomicstatus.

Hardcopy records of each beneficiary’s instructions are retained by the SSNIT, and are

consideredconfidentialuntilthecontributor’s death. Thereafter,therecordisopenedso that

interested parties can learn of their rights, if any, to the deceased contributors remaining

benefits.Because of this confidentiality requirement, we were only allowed access to the

bequeathalinstructionsofdeceasedcontributorswhoseresidualpensionshadbeendisbursed,

and whose files were closed. Names, addresses, and other information that might identify

contributorsortheirrelativeswerewithheld.

OurtotalsampleofSSNITdataconsistsofrecordsof860contributorswhopassedaway

between1992(whenLaw247cameintoeffect)and2006.Themedianageatdeathis54years

(mean52.5years),whichislowerthanthemandatoryretirementageof60years.About70%

of our contributors were married at death; and only 10% are women – reflecting the

overwhelming predominance of men in the formal sector, and a corresponding slighter

predominance of women in the far larger informal sector. The data the SSNIT made available

alsocontainmoreobservationsfromlateryears.Weweretoldthisisbecausemanyolderfiles

areincomplete,missingmuchcriticalinformation,andlessreadilyaccessible.

27

Table6:SummaryStatisticsofPensionBequestData

Means of key variables for all files, files of matrilineal decedents, and files of patrilineal decedents.

Numbers in square brackets are sample sizes.Final column contains difference between matrilineal

and patrilineal mean, with t‐statistic for the difference bein g significantly different from zero in

parentheses.One,two,andthreeasterisksdenote

significancelevelat10%,5%,and1%,respectively.

Sample All Matrilineal Patrilineal

Difference

(t‐stat)

(i) (ii) (iii) (ii)minus(iii)

Ageatdeath(years)

Alldecedents 52.5[860] 52.13[421] 52.75[439]‐0.62(0.82)

Maledecedents 53.12[761] 53.14[357] 53.1[404] 0.02(0.20 )

Femaledecedents 47.27[99] 46.56[64] 48.57[35]‐2.01(‐0.83)

Married(fraction)

Alldecedents 69.7[600] 69.0[290] 71.0[310]‐2.0(0.55)

Maledecedents 71.9 72.5 71.3 1.3(‐0.39)

No.heirslisted

Alldecedents 2.64 2.85 2.43 0.422(3.25)***

Marrieddecedents 2.94 3.21 2.68 0.53(3.19)***

Maledecedents 2.67 2.96 2.41 0.55(3.79)***

Marriedmaledecedents 2.96[547] 3.29[259] 2.65[288] 0.64(3.63)***

IfclaimsadjustedbyAct560

a

4.91[250] 5.06[123] 4.76[127] 0.30(‐1.04)

Bequesttonuclearfamily(%)

Alldecedents 58.4 59.8 57.1 2.7(0.85)

Maledecedents 58.2 60.5 56.2 4.3(1.30)

Marriedmaledecedents 73.3 74.1 72.7 1.4(0.43)

Pre‐Act560decedents

b

51.8[348] 55.7[168] 48.2180] 7.5(1.52)

Post‐Act560decedents 62.9[512] 62.5[253] 0.633[259]‐0.008(‐0.21)

Act560auditeddecedents 0.547 0.564 0.530 0.034(0.575)

Benefitspaid/claim(2006/7)

c

4,500[85] 5,279[45] 3,622[40] 1,657(‐1.38)

Notes:

a. Lengthoftime(inyears)fromdeathofcontributortocompletionofdisbursementofsurvivorbenefits.

b. Act560,passedin1998,alteredthepermissibledistributionofsurvivorbenefits.

c. InGhanaiancedisperclaim.Theexchangeratein2006/2007wasapproximately¢1.00=US$1.00.

28

Summary statistics for the variables we construct from these records are reported in

Table6.Eachrecordsetsoutthecontributor’spensionbequeathaldecisionsandidentifiestheir

tribal background, from which we can infer their traditional inheritance custom.Each record

alsoliststhecontributor’smaritalstatus and most, though not all, provide the average ofthe

contributor’sbestthreeannualincomesfromamongthetwentyyearspriortothecontributor’s

death.

The46.5%ofcontributorsreporting tribalaffiliationsthatimplymatrilineal inheritance

normsalignswellwithanestimated48%forthenationalaverage.Thus,46.5%ofcontributors

chose from the list of permissible heirs under the matrilineal heading in Table 2, and the

remaining53.5%selectedheirsfromthelistunderthepatrilinealheading.

Recallfromsection3thatthepurposeofthisrestrictionistorestrictthecontributorto

leavingresidualbenefitstotheconjugalfamilyorthetraditionallineage.Bequestsofpension

benefitstoothers–e.g.personsnotbelongingtotheconjugalfamilyortraditionallineage–are

proscribed. Thus, the SSNIT does not permit a contributor from a patrilineal tribe to list

maternal uncle as an heir. Should a contributor attempt this, the list would be rejected.In

private conversations with SSNIT staff, we were told that the SSNIT cannot enforce this rule

completely.In practice, a mislabeled maternal uncle might become a heir. SSNIT officials

informed us that they simply lack the resources to thoroughly investigate each list of

beneficiaries and, in the absence of a challenge from other relatives and if the claims are

procedurally valid, simply distribute remaining funds to the pension recipients’ selected

beneficiaries without further investigation.The record of each contributor’s bequeathal

decision lists the chosen beneficiaries, the fraction of the total benefits bequeathed to each,

andtherelationshipofeachto

thecontributor.

Uponthedeathofacontributor,theSSNITtakesnoaction.Potentialheirsmustsubmit

claims for survivors’ benefits after a qualified contributor dies. SSNIT staff informed us in

private conversations that substantial benefits go unclaimed because heirs are unaware the

benefits exist, and because people who learn they are not listed beneficiaries often fail to

informthosewhoare oftheirrights.Unsurprisingly,contributorswhowere marriedatdeath

list more beneficiaries: 2.94 versus 1.94 for single contributors.Male contributors list more

29

beneficiariesthandofemalecontributors,andcontributorsfrommatrilinealtribeslistaslightly

largeraveragenumberofbeneficiaries(2.85)thandothosefrompatrilinealtribes(2.43).

Finally,eachrecordprovidesthetotalvalueofsurvivorbenefitspaidout.Thesecanbe

substantial by Ghanaian standards:the median for the 319 records closed in the 2006‐2007

fiscal year, when the Ghanaian cedi was at ¢1.00 = US$1.00, was ¢2,142; the mean was

¢4,500;andthestandarddeviationwas¢5,539.

15

Thebequestswerethustypicallyfourtoover

seventimesmorethanGhana’sGDPpercapita,whichthenstoodatonlyaboutUS$500.

Also recall from Section 2 that the 1998 Children’s Act 560 altered the permitted

distribution of survivors’ benefits by the SSNIT.Prior to this, the contributor’s list of

beneficiariesdeterminedthedistributionofallremainingbenefits;butafterwards60%ofthe

totalbenefitsmustgotothecontributor’schild(ren)under18years,regardlessofwhetherthey

are listed as beneficiaries or not and the remaining 40% is distributed in accordance with the

contributor’s list of beneficiaries. The SSNIT theoretically investigates each claim to uncover

other minor children, including illegitimate children, though in practice resource constraints

limitthis.Oneresultofthisisanincreaseinthenumberofbeneficiariesinrecordsclosedafter

1998becausetheSSNITaddsthenamesofminorchildrentothese.Thus,filesclosedunderAct

560 named an average of 4.91 beneficiaries each, while those closed prior to 1998 named an

average of 2.61 beneficiaries each. This Act thus substantially shifted SSNIT survivor benefits

away from what contributors initia lly intended and towards their own children.This proves

usefulineconometricanalysisbelow.

5. MethodologyandEconometricResults

Wenowexamineeconometricallytheimpactsofthesetworeforms.Ourgoalis toestimatethe

extenttowhichtribalinheritancenormsshapeeconomicoutcomesofthoseonthemarginsof

Ghanaian society; and for the case of retirees, how the reforms influence private, end‐of‐life

bequest decisions. We begin

the analysis with individuals’ bequest decisions about their

unexpiredpensions.Becauseweareinterestedin thestatusofwidows,we first focusonthe

90percentofourSSNITrecordsthataremales.

15

Not all 319 passed in that year; some died earlier, but survivor-benefits not disbursed until 2006.

30

5.1 PensionBequestDecisionsandtheChildren’sAct(Act560,1998)

The1998ChildAct560soughttoimprovethestatusofwidowsandtheirchildrenbyinstructing

theSSNITtoadjustsurvivors’benefitsso thatatleast60%ofunexpiredbenefitspasses tohis

minorchildren,regardlessofthecontributor’sinstructions.

Ideally, we would also like to investigate how Act 560 altered contributors’ bequest

decisions. In 1998, the changes were widely publicized, and contributors were urged to alter

theirbequeststoaccordwiththenewrules.Nodoubt,manycontributorsignoredthisadvice,

andlefttheiroriginalinstructionsinplace.Unfortunately,ourdata onclosedSSNITfilesinclude

too few decedents whose initial instructions are dated after 1998 to allow statistically

meaningfulanalysis.Wethereforecontrasttherecordedbequestdecisionsofcontributorswho

diedafter1999,someofwhichwerechangedtoreflectthenewrules,againstthedecisionsof

contributors who died earlier, and who thus felt no pressure to alter their instructions to the

SSNIT.Wetake1999,ratherthan1998,asourtransitionyeartoensurethatcontributorshad

sufficientopportunitytoreacttotherulechange.

Todeterminewhetherthenewrulealteredthenumberofheirscontributorslistintheir

SSNITfiles,weestimateregressionsoftheform

(1)

where isanindicatorvariablesettooneifthecontributor’sdeathoccurredafter

1999, and zero otherwise; is the logarithm of the age at which he died, and the

are individual characteristics including marital status and an indicator variable for the

contributorbeingamongthetop25%intotalunexpiredpension(Top25Pension)inthecohort

whodiedinthesameyear.Weinterpretthisindicatorvariableasaproxyforthecontributor’s

totalwealth,whichisunavailable.Finally,wecontrolforage,thecontributor’sageatdeath.

Table 7 reports estimated parameters for (1).The 2.67 grand mean summarizes a

statistically significant increase from a bit over 2.5 heirs per contributor prior to 1999 to just

31

below three thereafter.The typical contributor dying after 1999 thus names more heirs as

beneficiaries, regardless of customary law. The positive significant coefficient on ln(age)

indicatesthatoldermenalsonamemoreheirsinthebequestsdecisions.Whilethismightbe

explainedbyoldermenhaving had timetosirelarger families,butcouldalsobe duetoolder

menbeingmoreconscientiousabouttheirlegacies.

We include all male contributor files in the above analysis because many males who

declarethemselvesunmarriednonethelessreportchildren.Thesemaybewidowers,menwho

interpret the question as pertaining only to formally recorded marriages, or men with

illegitimatechildren;ortheSSNITmaynotupdatethisfieldwhenupdatingdataaboutchildren.

Re‐estimatingtheregressionsusingmaleswhoreportthemselvesasmarriedintheirSSNITfiles

generatesbroadlysimilarresults,thoughthepostAct560indicatorvariablenowfailstoattain

significance in the smaller sample.For completeness, we also estimate the regression for

femalecontributors(notshown)andformarriedfemalecontributors.Likemales,olderfemale

contributors have more heirs; but unlike their male coworkers, females list markedly fewer

heirsafterAct560thanbeforeit.Theverysmallsamplemakesthisresultsomewhatuncertain,

despiteitsstatisticalsignificance.

Concedingtheconsiderablelimitationsofourdataandmethodology,weinferthatthe

dataarenot inconsistentwitha discernable differencebetweenbequestdecisions beforeand

aftertheAct.ThepurposeoftheActwastoinducecontributorstoprovidemorefullyfortheir

conjugalfamiliesandtodivertbequestsawayfromtheirlineages.Toquantifyitseffectiveness,

wecalculatethetotalfractionsofunexpiredpensioncontributors’bequestspassedtodifferent

categoriesofrelatives,implicitlyassigningzerotounmentionedrelations.

Again, data limitations necessitate caveats.We need not have complete information

about each contributor’s family. For example, no children listed as beneficiaries means the

contributormadenoprovisionsforchildren,notthathehadnone.Hemayhaveneglectedto

updatehisrecordashisfamilygrew;orhemighthavedeliberatelyomittedhischildren.

We partition each contributor’s heirs into

two groups: conjugal (or nuclear) family –

sons, daughters and surviving spouse(s); and other lineage members. This partition highlights

the difficulties we confront in drawing inferences from these data:only 72% of males are

32

classifiedasmarried.Thisisfar lowerthatthemarriedfractionofthemalepopulation,known

fromcensusrecords;andthereforesuggeststhatmanycontributorslikelydonotupdatetheir

SSNITrecords.BecauseGhanaiancultureexertshugesocialpressureonmentofatherchildren,

mostplacemarriageandraisingafamilyamongtheirhighestlifepriorities.Thisisparticularly

soformenintheformalsector,whoseeconomicpositionsmakethemhighlymarriageable.

Table7.NumberHeirsListedinSSNITRecords

Dependentvariableisthelogarithmofthenumberofheirslistedbythedeceasedmalecontributorto

the SSNIT pension system. Reported values are OLS estimates, and numbers in parentheses are t‐

statistics. One,two,andthreeasterisksdenotesignificancelevelat10%,5%,and1%,respectively.

Sample Allmales

Marriedmales Marriedfemales

Matrilineal 0.086 (0.90) 0.120 (1.26)

‐0.332 (‐1.46)

Post‐Act560 0.100 (1.66*) 0.098 (1.25)

‐0.577 (‐2.75***)

Married 0.223 (3.40***)‐

‐

Top25 0.127 (1.68*) 0.158 (1.54)

‐0.967 (‐0.47)

Post‐Act560*matrilineal‐0.038 (‐0.42) 0.087 (0.74)

0.240 (0.78)

Married*matrilineal 0.122 (1.25)‐

‐

Top25*matrilineal 0.017 (0.16) 0.433 (0.31)

‐0.009 (‐0.03)

log(ageatdeath) 0.572 (5.85***) 0.593 (4.28***)

1.034 (3.04***)

Intercept‐1.842

(‐5.03***)‐1.707 (‐3.16***)

‐2.686 (‐1.95*)

R

2

0.13 0.08 0.26

Noofobs 761 547 53

33

Finally, every individual, no matter how isolated, belongs to a lineage.The only

conceivable exceptions would be orphaned foreigners from outside Sub‐Sharan Africa who

adoptGhanaiancitizenship.

Our regressions explaining the fraction of residual benefits each contributor in our

sample bequeathed to members of his nuclear family, as opposed to his lineage, which we

denote ,areoftheform

(2)

where the right‐hand side variables are defined as in regression (1).Because the dependent

variable is bounded by the unit interval, with mass at both endpoints, Table 8 reports tobit

regressions.

Unsurprisingly,marriedmenbequeathmoretoconjugalfamilies thandomenlistedas

unmarried.Because of the problem, mentioned above, of stale records, we re‐estimate the

tobitsrestrictingthesampletomendesignatedasmarried.Thethirdcolumnpresentsresults

forfemalecontributors.Again,ageissignificant:oldermenleavemorepensionwealthtotheir

nuclearfamilies.Asabove,thismaybebecauseoldermenhavelongertobuildlargerfamilies,

orbecausetheygrowmoreattachedtotheirconjugalfamilies.

Participants whose deaths occur after the 1999 implementation of Act 560 bequeath

12.7%moreoftheirpensionwealthtotheirnuclearfamilies.ThistooindicatesthattheActhad

an effect:When the law mandated that

contributors provide more to their nuclear families,

theycomplied.

34

Table8:Fractionofunexpiredpensionbequeathedtonuclearfamilymembers

Marginal effects estimated from Tobit regressions explaining fraction of benefits bequeathed to

surviving spouse(s) and children, as opposed to lineage. Right‐hand side variables are as in Table 5.

Numbersinparenthesesarerobustz‐statistics,adjustedforclusteringbyageofdeath.One,two,and

three asterisks denote significance level

at 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively. Note: Pseudo R‐squared

maynotrepresentvariationexplainedbydependentvariables.

Sample Allmales Marriedmales Allfemales

matrilineal 0.17 (1.97)** 0.001 (0.02)‐0.209 (‐0.88)

post560 0.127 (2.45)** 0.098 (1.97)**‐0.168 (‐0.91)

married 0.543 (7.71)***‐‐ 0.353 (1.97)**

Top25‐0.069 (‐1.15)‐0.055 (‐0.94)‐0.215 (‐1.14)

Post560*matrilineal‐0.136 (‐1.91)*‐0.074 (‐1.09) 0.267 (1.18)

Married*matrilineal‐0.146 (‐1.77)*‐‐ ‐0.120 (‐0.58)

Top25*matrilineal 0.034 (0.43) 0.018 (0.23) 0.296 (1.21)

Log(ageatdeath) 0.508 (5.47)*** 0.415 (4.59)*** 0.534 (2.20)**

R

2

0.18 0.04 0.11

Observations 761 547 99

35

In addition, the data show a secular time trend towards increasingpension allocations

tonuclearfamilies–perhapsbecauseofanongoingerosionoftraditionalvalues.Atimetrend

also accords with a growing social advocacy role for the SSNIT. SSNIT records office staff (in

particular, female staff) shared with us stories about how, over time, they increasingly

assertivelyremindedmenoftheir“responsibilitiestotheir nuclear family”, andtoprovidefor

theirspousesandchildrenwhenlistingheirsintheirSSNITrecords.Atimetrendaddedtothe

regressionsinTable8issignificant,butajumpisnonethelessdiscernibleat1999.Weconclude

thattheActhadaneffect.

Intriguingly, the tobits reveal that the Act’s major effect was not its intended one:

altering bequests by men from matrilineal tribes.These bequeathed more to their conjugal

families before the reform, and did not substantially increase these bequests to conjugal

familiesafter1999.Onepossibleexplanationisthatmenfrommatrilinealtribesusedpension

bequests to circumvent their tribal inheritance customs all along.These results appear

independentofthemagnitudeofunexpiredbenefits.TheSSNITbequestdecisionwas,afterall,

deliberatelyheldconfidentialuntilthecontributor’sdeath,andcould thusprovideprivacyfrom

pressure to adhere to the traditional inheritance system. Indeed, the SSNIT was intended, in

part at least, to provide a defense to men from matrilineal tribes who wished to provide for

theirchildren;butwhofearedthewrathoftraditionally‐mindedrelatives.

To further test if values might be genuinely changing, we gauge for married men’s

“generosity”towardstheirnuclearfamilies.Wedefine“generosity”asbequeathingmorethan

themandatoryminimumof60%tohisnuclearfamily.Thatis,generosity=1ifpercentNUC >

60%andzerootherwise.

Table 9 presents logistic regressions, similar in form

to (2) but with generosity on the

left‐hand side. Matrilineal and married males are more “generous” than patrilineal and

unmarriedmalestotheirchildren,andallmalesgrowmoregenerousafterAct560.However,

again, no discernible difference is evident in the Act’s effect on men from matrilineal versus

patrilinealbackgrounds.

36

Table9:GenerosityofPensionBequeststoNuclearFamily

Marginaleffectsare estimated usinglogitregressions explaininganindicatorvariablesettooneif

bequest to surviving spouse(s) and children, as opposed to lineage, exceeds the mandatory

minimumrequiredbylawforminors(60%).Right‐handsidevariablesareasinTable5.Numbersin

parentheses are robust z‐statistics,

adjusted for clustering by age of death.One, two, and three

asterisks denote significance level at 10%, 5%,and 1%, respectively. Note: Pseudo R‐squared may

notrepresentvariationexplainedbydependentvariables.

Sample Allmales Marriedmales Allfemales

matrilineal 0.235 (2.30)** 0.048 (0.76)‐0.361 (‐2.04)**

post560 0.118 (1.95)** 0.081 (1.47)‐0.346 (‐2.39)**

married 0.550 (10.92)*** ‐‐ 0.373 (2.09)**

Top25 0.035 (0.48) 0.024 (0.37)‐0.278 (‐1.29)

Post560*matrilineal‐0.105 (‐1.20)‐0.025 (‐0.31) 0.414 (2.70)***

Married*matrilineal‐0.133 (‐1.30)‐‐ ‐0.219 (‐0.88)

Top25*matrilineal‐0.118 (‐.018)‐0.02 (‐0.02) 0.218 (1.16)

Log(ageatdeath) 0.558 (5.61) 0.427 (4.71)***

0.523 (2.41)**

PseudoR

2

0.22 0.05 0.14

Observations 761 547 99

37

The generosity of female contributors’ pension bequeathals is remarkably different.

Althoughboth maleandfemalecontributorsaremore“generous”iftheyreportmorechildren,

femaleformalsectorworkersaredecidedlylessgeneroustotheirconjugalfamiliesiftheirtribal

traditionismatrilineal,andgrowevenlessgenerous afterAct560takeseffect.Policy makers

may wish to consider education programs directed at matrilineal females if further steps to

forcecontributorstoprovidefortheirownchildrenaredeemeddesirable.

Next,weestimatethelikelihoodthattheSSNITascertainsadecedent’sinstructionsto

beinviolationoftheAct560.Also,in caseswherethe SSNITdiscoversaviolationoftheAct,

weexplorethesizesoftheadjustmentsitimposes.

16

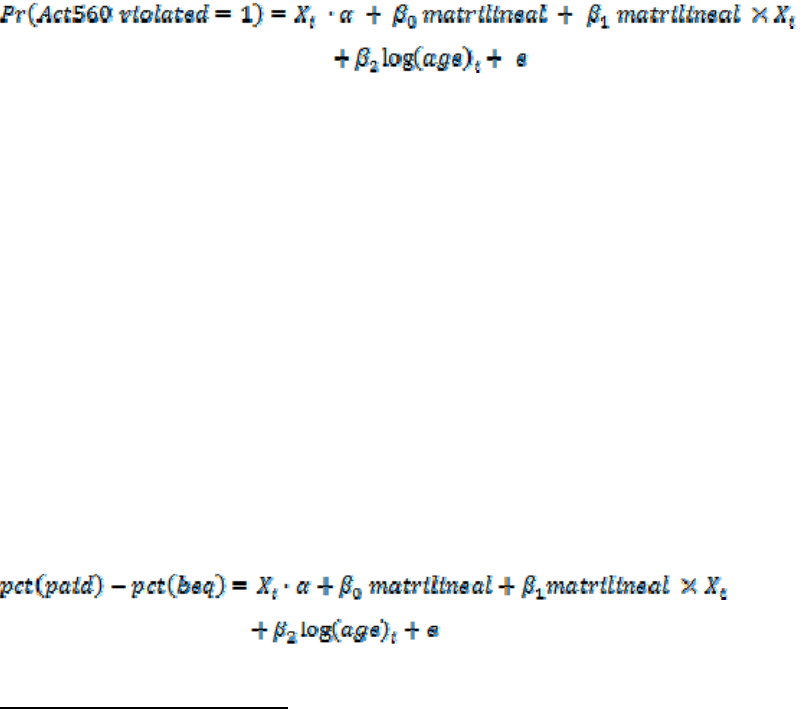

We estimate the probability of the SSNIT finding a violation using the following probit

regression:

(3)

where Act560violated is an indicator variable set to one if the SSNIT decides that the

contributor’sbequestsdecisionviolatesAct560,andtozerootherwise.Table10reportsthese

resultsinitsfirstcolumn.Theinstructionsofmarrieddecedentsareabout19%morelikelyto

violateAct560.Butolder menareactuallyless likely toleaveinstructionsthat violate the Act.