Balance of

Payments and

International

Investment

Position Manual

Sixth Edition (BPM6)

Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual

Sixth Edition (BPM6)

Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual

IMF

Sixth Edition (BPM6)

2009

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Balance of

Payments and

International

Investment

Position Manual

Sixth Edition (BPM6)

© 2009 International Monetary Fund

Production: IMF Multimedia Services Division

Typesetting: Alicia Etchebarne-Bourdin

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Balance of payments and international investment position manual.—

Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2009.

p.; cm.

6th ed.

Previously published as: Balance of payments manual.

ISBN 978-1-58906-812-4

1. Balance of payments—Statistics—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Invest-

ments—Statistics—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Title: Balance of

payments manual. III. International Monetary Fund.

HG3881.5.I58 I55 2009

Price: US$80.00

Please send orders to:

International Monetary Fund, Publication Services

700 19th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20431, U.S.A.

Tel.: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: publications@imf.org

Internet: www.imfbookstore.org

iii

Table of Contents

Foreword ix

Preface xi

List of Abbreviations xvii

Chapter 1. Introduction 1

A. Purposes of the Manual 1

B. Structure of the Manual 2

C. History of the Manual 3

D. The 2008 Revision 4

E. Revisions between Editions of the Manual 5

Chapter 2. Overview of the Framework 7

A. Introduction 7

B. Structure of the Accounts 7

C. Metadata, Dissemination Standards, Data Quality, and Time Series 16

Annex 2.1 Satellite Accounts and Other Supplemental Presentations 16

Annex 2.2 Overview of Integrated Economic Accounts 18

Chapter 3. Accounting Principles 29

A. Introduction 29

B. Flows and Positions 29

C. Accounting System 34

D. Time of Recording of Flows 35

E. Valuation 40

F. Aggregation and Netting 46

G. Symmetry of Reporting 48

H. Derived Measures 48

Chapter 4. Economic Territory, Units, Institutional Sectors,

and Residence 50

A. Introduction 50

B. Economic Territory 50

C. Units 52

D. Institutional Sectors 59

E. Residence 70

F. Issues Associated with Residence 75

Chapter 5. Classifications of Financial Assets and Liabilities 80

A. Definitions of Economic Assets and Liabilities 80

B. Classification of Financial Assets and Liabilities by Type of Instrument 82

C. Arrears 97

iv

D. Classification by Maturity 97

E. Classification by Currency 97

F. Classification by Type of Interest Rate 98

Chapter 6. Functional Categories

99

A. Introduction 99

B. Direct Investment 100

C. Portfolio Investment 110

D. Financial Derivatives (Other than Reserves) and Employee Stock Options 110

E. Other Investment 111

F. Reserves 111

Chapter 7. International Investment Position

119

A. Concepts and Coverage 119

B. Direct Investment 122

C. Portfolio Investment 124

D. Financial Derivatives (Other than Reserves) and Employee Stock Options 125

E. Other Investment 126

F. Reserves 130

G. Off-Balance-Sheet Liabilities 130

Annex 7.1 Positions and Transactions with the IMF 130

Chapter 8. Financial Account 133

A. Concepts and Coverage 133

B. Direct Investment 135

C. Portfolio Investment 137

D. Financial Derivatives (Other than Reserves) and Employee Stock Options 137

E. Other Investment 138

F. Reserve Assets 141

G. Arrears 141

Chapter 9. Other Changes in Financial Assets and Liabilities Account 142

A. Concepts and Coverage 142

B. Other Changes in the Volume of Financial Assets and Liabilities 143

C. Revaluation 146

Chapter 10. Goods and Services Account 149

A. Overview of the Goods and Services Account 149

B. Goods 151

C. Services 160

Chapter 11. Primary Income Account 183

A. Overview of the Primary Income Account 183

B. Types of Primary Income 184

C. Investment Income and Functional Categories 202

Chapter 12. Secondary Income Account 207

A. Overview of the Secondary Income Account 207

B. Concepts and Coverage 207

C. Types of Current Transfers 210

Chapter 13. Capital Account

216

A. Concepts and Coverage 216

TABLE OF CONTENTS

v

B. Acquisitions and Disposals of Nonproduced, Nonfinancial Assets 217

C. Capital Transfers 219

Chapter 14. Selected Issues in Balance of Payments and International

Investment Position Analysis

222

A. Introduction 222

B. General Framework 222

C. Alternative Presentations of Balance of Payments Data 225

D. Financing a Current Account Deficit 227

E. Balance of Payments Adjustment in Response to a Current Account Deficit 230

F. Implications of a Current Account Surplus 232

G. The Balance Sheet Approach 234

H. Further Information 236

Appendix 1. Exceptional Financing Transactions

237

A. Introduction 237

B. Transfers 238

C. Debt-for-Equity Swap 238

D. Borrowing for Balance of Payments Support 239

E. Debt Rescheduling or Refinancing 239

F. Debt Prepayment and Debt Buyback 240

G. Accumulation and Repayment of Debt Arrears 240

Appendix 2. Debt Reorganization and Related Transactions 245

A. Debt Reorganization 245

B. Transactions Related to Debt Reorganization 253

Appendix 3. Regional Arrangements: Currency Unions, Economic

Unions, and Other Regional Statements 255

A. Introduction 255

B. Currency Unions 255

C. Economic Unions 261

D. Customs Arrangements 262

E. Other Regional Statements 264

Appendix 4. Statistics on the Activities of Multinational

Enterprises 269

A. Introduction 269

B. Coverage 270

C. Statistical Units 270

D. Time of Recording and Valuation 270

E. Attribution of AMNE Variables 270

F. Compilation Issues 271

Appendix 5. Remittances 272

A. Economic Concept of Remittances and Why They Are Important 272

B. Standard Components in the Balance of Payments Framework Related

to Remittances 272

C. Supplementary Items Related to Remittances 273

D. Related Data Series 275

E. Concepts 275

F. Data by Partner Economy 277

Table of Contents

vi

Appendix 6a. Topical Summary—Direct Investment 278

A. Purpose of Topical Summaries 278

B. Overview of Direct Investment 278

Appendix 6b. Topical Summary—Financial Leases 280

Appendix 6c. Topical Summary—Insurance, Pension Schemes, and

Standardized Guarantees 282

A. General Issues 282

B. Nonlife Insurance 283

C. Life Insurance and Annuities 286

D. Pension Schemes 287

E. Standardized Guarantees 288

Appendix 7. Relationship of the SNA Accounts for the Rest of the

World to the International Accounts 289

Appendix 8. Changes from BPM5 292

Appendix 9. Standard Components and Selected Other Items 301

A. Balance of Payments 301

B. International Investment Position 309

C. Additional Analytical Position Data 313

Boxes

2.1 Double-Entry Basis of Balance of Payments Statistics 10

2.2 Data Quality Assessment Framework 15

6.1 Examples of Identification of Direct Investment Relationships under

FDIR 102

6.2 Direct Investment Relationships with Combination of Investors 104

6.3 Direct Investment Relationship Involving Domestic Link 106

6.4 Derivation of Data under the Directional Principle 109

6.5 Components of Reserve Assets and Reserve-Related Liabilities 112

8.1 Entries Associated with Different Types of Debt Assumption 140

9.1 Example of Calculation of Revaluation Due to Exchange Rate Changes 148

10.1 Examples of Goods under Merchanting and Manufacturing Services

on Physical Inputs Owned by Others (Processing Services) 158

10.2 Recording of Global Manufacturing Arrangements 162

10.3 Numerical Examples of the Treatment of Freight Services 165

10.4 Numerical Examples of the Calculation of Nonlife Insurance Services 171

10.5 Numerical Example of Calculation of FISIM 174

10.6 Technical Assistance 182

11.1 Reinvested Earnings with Chain of Ownership 191

11.2 Numerical Example of Calculation of Interest Accrual on a

Zero-Coupon Bond 194

11.3 Numerical Example of Calculation of Interest Accrual on an Index-

Linked Bond—Broad-Based Index 196

11.4 Numerical Example of Calculation of Interest Accrual on an Index-

Linked Bond—Narrowly Based Index 197

11.5 Numerical Example of Calculation of Reinvested Earnings of a

Direct Investment Enterprise 203

A3.1 Recording of Trade Transactions in Currency and Economic Unions 259

A6a.1 Direct Investment Terms 279

A6b.1 Numerical Example of Financial Lease 281

TABLEOFCONTENTS

vii

A6c.1 Numerical Example of Calculations for Nonlife Insurance 283

Figure

2.1 Overview of the System of National Accounts as a Framework for

Macroeconomic Statistics Including International Accounts 8

Tables

2.1 Overview of International Accounts 14

2.2 Overview of Integrated Economic Accounts 18

2.3 Link between Instrument and Functional Categories 26

4.1 SNA Classification of Institutional Sectors 60

4.2 BPM6 Classification of Institutional Sectors 61

4.3 Selected Effects of a Household’s Residence Status on the Statistics of the

Host Economy 73

4.4 Selected Effects of the Residence Status of an Enterprise Owned by a

Nonresident on the Statistics of the Host Economy 74

5.1 Economic Asset Classification 81

5.2 Returns on Financial Assets and Liabilities: Financial Instruments and

Their Corresponding Type of Income 83

5.3 2008 SNA Financial Instruments Classification (with Corresponding

BPM6 Broad Categories) 84

6.1 Link between Financial Assets Classification and Functional Categories 100

7.1 Integrated International Investment Position Statement 120

7.2 Overview of the International Investment Position 121

8.1 Overview of the Financial Account 134

9.1 Overview of the Other Changes in Financial Assets and Liabilities Account 143

10.1 Overview of the Goods and Services Account 150

10.2 Reconciliation between Merchandise Source Data and Total Goods on a

Balance of Payments Basis 161

10.3 Treatment of Alternative Time-Share Arrangements 168

10.4 Treatment of Intellectual Property 176

11.1 Overview of the Primary Income Account 184

11.2 Detailed Breakdown of Direct Investment Income 204

11.3 Detailed Breakdown of Other Investment Income 205

12.1 Overview of the Secondary Income Account 208

13.1 Overview of the Capital Account 217

14.1 “Analytic” Presentation of the Balance of Payments 226

A1.1 Balance of Payments Accounting for Selected Exceptional Financing

Transactions 241

A3.1 Methodological Issues Relevant for Different Types of Regional

Cooperation 256

A5.1 Components Required for Compiling Remittance Items and Their Source 273

A5.2 Tabular Presentation of the Definitions of Remittances 274

A7.1 Correspondence between SNA and International Accounts Items 290

A9-I Currency Composition of Assets and Liabilities 313

A9-II Currency Composition of Assets and Liabilities 315

A9-III Currency Composition by Sector and Instrument 316

A9-IV Remaining Maturity of Debt Liabilities to Nonresidents 320

A9-V Memorandum/Supplementary Items: Position Data 320

Index

322

Table of Contents

ix

Foreword

The International Monetary Fund since its inception has had a compelling interest in

developing and promulgating guidelines for the compilation of consistent, sound, and

timely balance of payments statistics. This work underpins the IMF’s other responsi-

bilities, including conducting surveillance of countries’ economic policies and providing

financial assistance that enables countries to overcome short-term balance of payments

difficulties. Such guidelines, which have evolved to meet changing circumstances, have

been embodied in successive editions of the Balance of Payments Manual (the Manual)

since the first edition was published in 1948.

I am pleased to introduce the sixth edition of the Manual, which addresses the many

important developments that have occurred in the international economy since the fifth

edition was released. The fifth edition of the Manual, released in 1993, for the first time

addressed the important area of international investment position statistics. The sixth edi-

tion builds on the growing interest in examining vulnerabilities using balance sheet data,

as reflected in the addition of international investment position to the title, and extensive

elaboration of balance sheet components. The Manual also takes into account develop-

ments in globalization, for example, currency unions, cross-border production processes,

complex international company structures, and issues associated with international labor

mobility, such as remittances. In addition, it deals with developments in financial markets

by including updated treatments and elaborations on a range of issues, such as securitiza-

tion and special purpose entities.

Because of the important relationship between external and domestic economic devel-

opments, the Manual was revised in parallel with the update of the System of National

Accounts 2008. To support consistency and interlinkages among different macroeco-

nomic statistics, this edition of the Manual deepens the harmonization with the System of

National Accounts and the IMF’s manuals on government finance and on monetary and

financial statistics.

The revised Manual has been prepared by the IMF’s Statistics Department in close

consultation with the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics, which includes

experts from a range of member countries as well as international and regional organiza-

tions. In addition, input was received from specialized expert groups, and from member

countries and international organizations during regional seminars and public comment

periods on successive drafts of the Manual. In total, representatives from virtually all IMF

member countries participated in one or more of these initiatives. The process underly-

ing the revision of the Manual demonstrates the spirit of international collaboration and

cooperation, and I would like to commend all of the national and international experts

involved for their invaluable assistance.

I would like to recommend the Manual to compilers and users. I urge member countries to

adopt the guidelines of the sixth edition as their basis for compiling balance of payments and

international investment position statistics and for reporting this information to the IMF.

Dominique Strauss-Kahn

Managing Director

International Monetary Fund

xi

Preface

Introduction

1. The release of the sixth edition of the Balance of Payments and International Invest-

ment Position Manual (BPM6) is the culmination of several years of work by the IMF

Statistics Department and the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics (the

Committee) in collaboration with compilers and other interested parties worldwide. It

updates the fifth edition published in 1993, providing guidance to IMF member countries

on the compilation of balance of payments and international investment position data.

2. When the Committee decided in 2001 to initiate an update of the manual, it con-

sidered that, while the overall framework of the fifth edition (BPM5) remained adequate,

it needed to incorporate the numerous elaborations, clarifications, and improvements

and updates in methodology that had been identified since 1993, and to strengthen the

theoretical foundations and linkages to other macroeconomic statistics. The production of

BPM6 was conducted in parallel with the update of the OECD Benchmark Definition of

Foreign Direct Investment, and the System of National Accounts (SNA) to maintain and

enhance consistency among these manuals.

Consultative process

3. The production of BPM6 was characterized by extensive consultation. In addition to

the Committee’s oversight, there was significant outreach to the wider community.

Annotated outline

4. In April 2004, the IMF released an Annotated Outline for the update of the manual.

It included proposals and options for the style and content of the revised manual. Ques-

tions were posed on specific issues to gauge views. The outline was circulated to central

banks and statistical agencies, and was posted on the IMF website. Input was invited from

compilers and other interested parties worldwide. Altogether, 33 countries provided writ-

ten comments.

Technical expert groups

5. The Committee established four technical expert groups, with membership from

member countries and international agencies, to undertake detailed consideration of issues

and make recommendations on currency unions (Currency Union Technical Expert Group,

or CUTEG), direct investment (Direct Investment Technical Expert Group, or DITEG),

reserves (Reserve Assets Technical Expert Group, or RESTEG), and other issues (Balance

of Payments Technical Expert Group, or BOPTEG). DITEG was chaired jointly with the

OECD and had common membership and meetings with the OECD’s Benchmark Advi-

sory Group (BAG) to bring about consistent treatments. The issue papers and outcome

papers were posted on the IMF’s website. Many of the issues discussed also were relevant

xii

for the update of the SNA, thus ensuring coordination with the Advisory Expert Group on

National Accounts (AEG), which had been created by the InterSecretariat Working Group

on National Accounts as an advisory and consultative body for the update of the SNA.

6. In addition, other specialized groups provided input on such topics as trade in ser-

vices, merchandise trade, tourism, remittances, debt statistics, and fiscal statistics. Inter-

national organizations participated in all stages of the process directly and as members of

specialized groups.

Worldwide review

7. Draft versions of the Manual were published on the IMF website in March 2007 and

March 2008. In each case, worldwide comment was invited within a deadline of three months.

About 60 sets of comments were received on the 2007 version, and 20 on the 2008 version. In

addition, other draft versions of selected chapters and of the whole document were circulated

to Committee members, other departments of the IMF, and other interested parties.

8. Furthermore, an expert review of the draft version was undertaken in January 2008

by Mahinder Gill, a retired IMF staff member and former Assistant Director, who super-

vised the drafting of BPM5, to identify any inconsistencies or omissions in the document,

and to check the consistency with the SNA.

9. During 2008, a series of nine regional outreach seminars was conducted on the Man-

ual to explain the proposed changes and encourage comments on the content and drafting.

Representatives from 173 IMF member economies, along with a number of international

agencies, participated in these seminars and provided many useful suggestions.

10. Taking account of the written comments on the March 2008 draft, inputs from

the regional seminars, and the finalization of Volume 1 of the 2008 SNA, a new draft

version was circulated to Committee members in July 2008. Following a further round

of comments by Committee members and internal IMF review, the BPM6 was adopted

unanimously by the Committee in November 2008.

Major changes introduced

11. The overall framework of the fifth edition is unchanged and BPM6 has a high

degree of continuity with BPM5. Some of the most significant changes from the last edi-

tion are as follows:

• Revised treatment of goods for processing and goods under merchanting;

• Changes in the measurement of financial services, including Financial Interme-

diation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM), spreads on the purchase and sale

of securities, and the measurement of insurance and pension services;

• Elaboration of direct investment (consistent with the OECD Benchmark Definition

of Foreign Direct Investment, notably the recasting in terms of control and influ-

ence, treatment of chains of investment and fellow enterprises, and presentation on

a gross asset and liability basis as well as according to the directional principle);

• The introduction of the concepts of reserve-related liabilities, standardized guar-

antees, and unallocated gold accounts;

• New concepts for the measurement of international remittances;

• Increased focus on balance sheets and balance sheet vulnerabilities (including a

chapter on flows other than those arising from balance of payments transactions);

PREFACE

xiii

• Strengthened concordance with the SNA (such as the full articulation of the

SNA/Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual (MFSM) financial instrument

classification and the use of the same terminology such as primary and second-

ary income); and

• Extensive additions to the Manual, which is double the length of the original

because of added detail and explanation, and new appendixes (such as currency

unions, multinational enterprises, and remittances).

12. A detailed list of changes from BPM5 is provided in Appendix 8 of the Manual.

Acknowledgments

IMF staff

13. The BPM6 was produced under the direction of three Directors of the Statistics

Department (STA): Carol Carson (2001–04), Robert W. Edwards (2004–08), and Adelheid

Burgi-Schmelz (2008–). Lucie Laliberté was the responsible Deputy Director (2004–).

14. In the Balance of Payments Divisions, the editor of the BPM6 throughout the

project was Robert Dippelsman, Senior Economist, who provided the essential expert

continuity. Robert Dippelsman and Manik Shrestha, a Senior Economist and coeditor,

2002–06, were primary drafters of both the Annotated Outline and BPM6. The project

was supervised by Neil Patterson, Assistant Director (2001–06); Robert Heath, Division

Chief (2003–08); and Ralph Kozlow, Division Chief (2007–).

15. Many staff of the Balance of Payments Divisions contributed to the project.

John Joisce, Senior Economist (2001–), was closely involved in various aspects of

the project throughout. The following Senior Economist staff drafted Appendixes:

Andrew Kitili (Appendixes 1 and 2), René Fiévet (Appendix 3), and Margaret Fitzgib-

bon (Appendix 4). Jens Reinke, Economist, drafted Appendix 5. Pedro Rodriguez, an

Economist in the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department (SPR), contributed

material for Chapter 14. In addition to staff mentioned above, the following members

of the Balance of Payments Divisions conducted the nine regional seminars in 2008:

He Qi and Emmanuel Kumah (Deputy Division Chiefs); and Paul Austin, Thomas

Alexander, Antonio Galicia, John Motala, and Tamara Razin (Senior Economists).

Within the staff of the Balance of Payments Divisions, Simon Quin (Deputy Division

Chief); Colleen Cardillo, Jean Galand, Gillmore Hoefdraad, Natalia Ivanik, Eduardo

Valdivia-Velarde, and Mark van Wersch (Senior Economists); and Sergei Dodzin, an

Economist in SPR, made notable contributions to improving the overall quality of the

BPM6.

16. Carmen Diaz-Zelaya and Marlene Pollard prepared the BPM6 drafts for publica-

tion. In addition to these staff, Esther George, Elva Harris, and Patricia Poggi supported

the preparation of papers for presentation at the Committee or technical expert group

meetings.

The Committee

17. The BPM6 was prepared under the auspices of the Committee. The BPM6 ben-

efited immensely from the expert advice of Committee members throughout the process;

their contribution was crucial to the success of the project. The Statistics Department

wishes to acknowledge, with thanks, the members and the representatives of international

organizations on the Committee during 2001–08:

Preface

xiv

Members

Australia Zia Abbasi Korea Jung-Ho Chung

Michael Davies Russian Sergei Shcherbakov

Bronwyn Driscoll Federation Lidia Troshina

Ivan King Saudi Arabia Abdulrahman Al-Hamidy

Belgium Guido Melis Sulieman Al-Kholifey

Canada Art Ridgeway South Africa Ernest van der Merwe

Chile Teresa Cornejo Stefaans Walters

China Han Hongmei Spain Eduardo Rodriguez-Tenés

China, Hong Kong Lily Ou-Yang Fong Uganda Michael Atingi-Ego

SAR United Kingdom Stuart Brown

France Philippe Mesny

1

United States Ralph Kozlow

Germany Almut Steger Obie Whichard

Hungary Antal Gyulavári

India Michael Debabrata

Patra

Italy Antonello Biagioli

Japan Satoru Hagino

Joji Ishikawa

Teruhide Kanada

Makoto Kato

Hideki Konno

Takehiro Nobumori

Toru Oshita

Takuya Sawafuji

Hidetoshi Takeda

Takashi Yoshimura

Representatives of International Organizations

Bank for International Rainer Widera Organization for Ayse Bertrand

Settlements (BIS) Economic William Cave

European Central Werner Bier Cooperation and

Bank (ECB) Jean-Marc Israël Development

Carlos Sánchez- United Nations Masataka Fujita

Muñoz Conference on

Pierre Sola Trade and

Eurostat Elena Caprioli Development

Maria-Helena Figueira United Nations IvoC.Havinga

Jean-Claude Roman Statistics

Mark van Wersch Division

1

From 2004 onward, Philippe Mesny represented the Bank for International Settlements.

PREFACE

xv

Technical expert groups

18. Asnotedabove,theCommitteecreatedfourtechnicalexpertgroupstoadviseiton

specific issues. The Statistics Department is most grateful for the expert advice provided

bythemembersofthesetechnicalexpertgroups.

Balance of Payments Technical Expert Group (BOPTEG)

Chair: Neil Patterson

Secretariat: Robert Dippelsman and Manik Shrestha

Zia Abbasi (Australia); Jamal Al-Masri (Jordan); Christopher Bach (United States); Stuart

Brown (United Kingdom); Khady Beye Camara (Banque Centrale des États de l’Afrique

de l’Ouest, BCEAO); Raymond Chaudron (the Netherlands); Teresa Cornejo (Chile);

MichaelDavies(Australia);SatoruHagino(Japan);HanHongmei(China);JanuusKroon

(Estonia); Philippe Mesny (BIS); Pawel Michalik (Poland); Frank Oudekken (the Neth-

erlands); Carlos Sánchez-Muñoz (ECB); Ipumbu Shiimi (Namibia); Almut Steger (Ger-

many); Hidetoshi Takeda (Japan); Nuannute Thana-anekcharoen (Thailand); Charlie

Thomas (United States); Mark van Wersch (Eurostat); Chris Wright (United Kingdom).

Direct Investment Technical Expert Group (DITEG)

Co-Chairs: Neil Patterson and Ralph Kozlow

2

Secretariat: John Joisce and Marie Montanjees (IMF), and Ayse Bertrand and Yesim Sisik

(OECD)

Olga Aarsman (the Netherlands); Zia Abbasi (Australia); Roger de Boeck (Belgium);

Lars Forss (Sweden); Christian Lajule (Canada); Mondher Laroui (Tunisia); Jeffrey Lowe

(United States); Peter Neudorfer (ECB); George Ng (Hong Kong SAR); Frank Ouddeken

(the Netherlands); Paolo Passerini (Eurostat); Art Ridgeway (Canada); Carlos Sánchez-

Muñoz(ECB);BrunoTerrien(France);LidiaTroshina(RussianFederation);Markvan

Wersch (Eurostat); Carlos Varela (Colombia); Martin Vaughan (United Kingdom); Maiko

Wada(Japan);GraemeWalker(UnitedKingdom);StefaansWalters(SouthAfrica);and

Obie Whichard (United States).

Currency Unions Technical Expert Group (CUTEG)

Chair: Robert Heath

Secretariat: René Fiévet and Samuele Rosa (IMF)

Gebreen Al-Gebreen (Saudi Arabia); Olga Antropova (Belarus); Khady Beye Camara

(BCEAO); Miriam Blanchard (Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, ECCB); Luca Buldorini

(Italy);RemigioEcheverria(ECB);NazaireFotsoNdefo(BanquedesÉtatsdel’Afrique

Centrale,BEAC);JeanGaland(ECB);RudolfOlsovsky(CzechRepublic);Jean-Marc

Israël (ECB);

3

andMarkvanWersch(Eurostat).

Reserve Assets Technical Expert Group (RESTEG)

Chair: Robert Heath

Secretariat:AntonioGaliciaandGillmoreHoefdraad

Hamed Abu El Magd (Egypt); Koichiro Aritoshi (Japan); Kevin Chow (Hong Kong

SAR); Allison Curtiss (United Kingdom); Mihály Durucskó (Hungary); Saher El-Sherbini

(Egypt); Kelvin Fan (Hong Kong SAR); Fernando Augusto Ferreira Lemos (Brazil);

2

DITEGwasajointtaskforcewiththeOECD’sBenchmarkAdvisoryGroup(BAG).RalphKozlowwas

chairoftheWorkshopofInternationalInvestmentStatistics(thebodyoverseeingtheBAG)whileAssociate

Director for International Economics at the Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce,

before joining the IMF’s Statistics Department.

3

Cochaired the second meeting of CUTEG held in Frankfurt.

Preface

xvi

Reiko Gonokami (Japan); Hideo Hashimoto (Japan); Yang Hoseok (Korea); Mohammed

Abdulla A. Karim (Bahrain); Philippe Mesny (BIS); Jean Michel Monayong Nkoumou

(BEAC); Linda Motsumi (South Africa); Christian Mulder (Monetary and Capital Mar-

kets Department, IMF); Joseph Ng (Singapore); Ng Yi Ping (Singapore); Carmen Picón

Aguilar (ECB); Stephen Sabine (United Kingdom); Julio Santaella (Mexico); Dai Sato

(Japan); Ursula Schipper (Germany); Jay Surti (Monetary and Capital Markets Depart-

ment, IMF); Charlie Thomas (United States); Lidia Troshina (Russian Federation); and

Yuji Yamashita (Japan).

Preparation of issues papers

Issues papers for four technical expert groups were prepared by Olga Antropova, Ayse

Bertrand, Stuart Brown, Richard Button, Robert Dippelsman, Remigio Echeverria, René

Fiévet, Jean Galand, Antonio Galicia, Gillmore Hoefdraad, Ned G. Howenstine, Maurizio

Iannaccone, John Joisce, Andreas Karapappas, Andrew Kitili, Stephan Klinkum, Ralph

Kozlow, Marie Montanjees, Frank Ouddeken, Paolo Passerini, Valeria Pellegrini, Art

Ridgeway, Samuele Rosa, Carlos Sánchez-Muñoz, Manik Shrestha, Pierre Sola, Hidetoshi

Takeda, Bruno Terrien, Lidia Troshina, Philip Turnbull, Martin Udy, Mark van Wersch,

and Chris Wright.

Issues papers also were prepared by the following institutions: International and Finan-

cial Accounts Branch, Australian Bureau of Statistics; National Bank of Belgium; Sta-

tistics Canada; European Central Bank; Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong,

SAR; Bank of Japan; Service Central de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, Lux-

embourg; Balance of Payments and Financial Accounts Department, De Nederlandsche

Bank; Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, OECD; and the U.K. Office for

National Statistics.

Other acknowledgments

19. The BPM6 also benefited from comments by national compilers, international

agencies, and interested individuals from the private sector arising from the public com-

ment periods on the March 2007 and March 2008 drafts. The IMF Statistics Department

acknowledges, with gratitude, their contributions.

20. The IMF Statistics Department is grateful for the support and cooperation of the

editor of the SNA, Anne Harrison.

Adelheid Burgi-Schmelz

Director, Statistics Department

International Monetary Fund

PREFACE

xvii

List of Abbreviations

AEG Advisory Expert Group on National Accounts

AMNE Activities of Multinational Enterprises

BAG Benchmark Advisory Group

BCEAO Banque Centrale des États de l’Afrique de l’Ouest

BEAC Banque des États de l’Afrique Centrale

BIS Bank for International Settlements

BOOT Build, own, operate, transfer

BOPSY Balance of Payments Statistics Yearbook

BOPTEG Balance of Payments Technical Expert Group

BPM5 Balance of Payments Manual, fifth edition (1993)

BPM6 Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual,

sixth edition (2008)

CDIS Coordinated Direct Investment Survey

CIF Cost, insurance, and freight

CIRR Commercial Interest Reference Rate

CMA Common monetary area

The Committee IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics

CPC Central Product Classification

CPIS Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey

CR. Credit

CU Currency union

CUCB Currency union central bank

CUNCB Currency union national central bank

CUTEG Currency Unions Technical Expert Group

DI Direct investment

DITEG Direct Investment Technical Expert Group

DR. Debit

EBOPS Extended Balance of Payments Services (Classification)

ECB European Central Bank

ECCB Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

EcUn Economic union

ESO Employee stock option

FATS Foreign AffiliaTes Statistics

FCA Free carrier

FD Financial derivatives (other than reserves) and employee stock

options

FDIR Framework for Direct Investment Relationships

FISIM Financial intermediation services indirectly measured

FOB Free on board

GAB General Arrangements to Borrow

GATS General Agreement on Trade in Services

xviii

GDP Gross domestic product

GFSM Government Finance Statistics Manual

GNDY Gross national disposable income

GNI Gross national income

HIPC Heavily indebted poor country

HS Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System

IC Insurance corporations

ICPF Insurance corporations and pension funds

IIP International investment position

IMF International Monetary Fund

IMTS International merchandise trade statistics

ISIC International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic

Activities

ISWGNA InterSecretariat Working Group on National Accounts

LIBOR London interbank offered rate

MFSM Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual

MMF Money market fund

MSITS Manual on Statistics of International Trade in Services

n.a. not applicable

NAB New Arrangements to Borrow

n.i.e. not included elsewhere

NGO Nongovernmental organization

NPISH Nonprofit institution serving households

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

OFC Other financial corporations

OI Other investment

PF Pension funds

PI Portfolio investment

PRGF Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility

RA Reserve assets

RESTEG Reserve Assets Technical Expert Group

RRL Reserve-related liabilities

SDR Special Drawing Right

SNA System of National Accounts

SPE Special purpose entity

SWF Sovereign wealth fund

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

1

CHAPTER

1

Introduction

A. Purposes of the Manual

1.1 The sixth edition of the Balance of Payments

and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6,

the Manual) serves as the standard framework for sta-

tistics on the transactions and positions between an

economy and the rest of the world.

1.2 The main objectives of this Manual are as

follows:

(a) To provide and explain concepts, definitions,

classifications, and conventions for balance of

payments and international investment position

statistics;

(b) To enhance international comparability of data

through the promotion of guidelines adopted

internationally;

(c) To show the links of balance of payments and

international investment position statistics to

other macroeconomic statistics and promote

consistency between different data sets; and

(d) To provide a brief introduction to uses of data on

balance of payments, other changes in financial

assets and liabilities, and international invest-

ment position, as the international accounts of

an economy.

1.3 Data collection and other compilation proce-

dures and dissemination are not generally within the

scope of a conceptual manual such as this one. Deci-

sions on such issues should take into account circum-

stances, such as practical and legal constraints, and

relative size, that need to be judged in each economy

and that may explain departures from guidelines. The

IMF’s Balance of Payments Compilation Guide pro-

vides information on these issues.

1.4 The Manual provides a framework that is applica-

ble for a range of economies, from the smallest and least

developed economies to the more advanced and complex

economies. As a result, it is recognized that some items

may not be relevant in all cases. It is the responsibil-

ity of national compilers to apply international guide-

lines in a way appropriate to their own circumstances. In

implementing this Manual, compilers are encouraged to

assess the materiality and practicality of particular items

according to their own circumstances and are further

encouraged to revisit these decisions from time to time to

see whether circumstances have changed. Such decisions

necessarily rely on the professionalism and knowledge of

the compilers.

1.5 Factors to take into account when determin-

ing the items to be collected and the techniques used

include whether or not exchange controls exist, the rela-

tive importance of particular types of economic activi-

ties, and the diversity of institutions and the range of

instruments used in financial markets. In addition, data

collection for some items in the framework may be

impractical if the item is small and the data collection

cost is high. Conversely, compilers may wish to iden-

tify other items of particular economic interest in their

economy for which additional detail may be required

by policymakers and analysts.

1.6 This Manual is harmonized with the System

of National Accounts 2008 (2008 SNA), which was

updated in parallel. Relevant elements of the Monetary

and Financial Statistics Manual 2000 and Govern-

ment Finance Statistics Manual 2001 will be revised

to maintain their harmonization with the two updated

manuals. Conceptual interlinkages mean that balance

of payments and international investment position com-

pilers should consult with other statisticians to ensure

consistent definitions and provide data that can be rec-

onciled where they overlap.

1.7 The definitions and classifications in this Man-

ual do not purport to give effect to, or interpret, various

provisions (which pertain to the legal characterization

of official action or inaction in relation to such transac-

tions) of the Articles of Agreement of the International

Monetary Fund.

2

B. Structure of the Manual

1.8 The Manual has 14 chapters and 9 appendixes.

Theintroductorychaptersdealwithissuesthatcutacross

theaccounts(Chapters1–6)andarefollowedbychap-

ters that cover respectively each main account (Chapters

7–13),closingwithachapteronanalysisofdata.The

Manual states general principles that are intended to be

applicable in a wide range of circumstances. As well, it

applies the principles to some specific topics that have

been identified as needing additional guidance. Defini-

tions are given throughout the text, shown in italics.

1.9 Consistent with this structure, different aspects

ofatopicaredealtwithindifferentchapterstomini-

mizerepetition.Forexample,theclassificationofport-

folioinvestmentisacross-cuttingissue(Chapter6),as

arevaluationandtimingissues(Chapter3).Theposi-

tion, transaction, other changes, and income aspects

are dealt with in Chapters 7, 8, 9, and 11, respectively.

Linkages are emphasized by extensive cross-references.

In addition, for direct investment, insurance, and finan-

cial leases, appendixes have been included to allow the

readertoseethelinkagesamongthedifferentaccounts

for that topic.

1. Introductory chapters

1.10 Theintroductorychapters(Chapters1–6)cover

the following:

(a) Chapter 1 gives background to the Manual.

(b) Chapter 2 covers the accounting and dissemina-

tion frameworks.

(c) Chapter3dealswithaccountingprinciples.

(d) Chapters 4 deals with issues associated with

units, sectors, and residence.

(e) Chapter 5 deals with the classification of assets

and liabilities.

(f) Chapter 6 explains the functional categories.

2. Chapters for each account

1.11 Chapters7–13dealwiththeaccountsofthe

framework. Each account reflects a single economic

process or phenomenon and has a single chapter. The

orderofchaptersisamatterofconvention;inthisedi-

tion,theinternationalinvestmentpositionappearsfirst

to reflect the increased emphasis on its compilation and

analysis since the release of the fifth edition (BPM5)and

to explain financial assets and liability positions before

dealing with the investment income they generate.

1.12 Each chapter starts with a statement of general

economic principles. A simplified table designed to

give an overview of the account is also included in

each chapter. The text provides general definitions

of items in the account. Specific cases are given as

examplesoftheapplicationofthegeneraldefinitions

andtoclearupambiguities.Afullunderstandingof

eachaccountalsorequiresapplyingthewiderprin-

ciplesthatapplyacrossseveralaccounts,suchasvalu-

ation, timing, residence, and classification, as covered

in the introductory chapters.

3. Analysis

1.13 Chapter 14 provides an introduction to the

analysisofdata,withparticularreferencetomacroeco-

nomicrelationshipsasawhole.

4. Appendixes

1.14 Appendixes provide more details on spe-

cificissuesthatgoacrossseveralaccounts,includ-

ingchangesfromBPM5, currency unions, exceptional

financing,debtreorganization,andalistingofstan-

dard components.

5. Standard components and memorandum

items

1.15 Alistofstandarditemsforpresentingand

reporting the balance of payments and international

investmentpositionisgiveninAppendix9.Standard

items consist of standard components and memoran-

dum items.

(a) Standard components are items that are fully

part of the framework and contribute to the

totals and balancing items.

(b) Memorandum items are part of the standard pre-

sentation, but are not used in deriving totals and

balancing items.Forexample,whereasnominal

valueisusedforloansinthestandardcompo-

nents, memorandum items provide additional

information on loans at fair value, as discussed

in paragraphs 7.45–7.46.

In addition,

(c) Supplementary items are outside the standard

presentation, but are compiled depending on

circumstances in the particular economy,taking

intoaccounttheinterestsofpolicymakersand

analysts as well as resource costs (see the items

in italics in Appendix 9).

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT POSITION MANUAL

3

1.16 Thelistofstandarditemsshouldnotinhibit

compilersfrompublishingadditionaldataofimportance

to their economy. IMF requests for information will not

be limited to standard items when further details are

required to understand the circumstances of particular

economiesortoanalyzenewdevelopments.IMFstaff

occasionally will consult with authorities to decide on

the reporting of additional details. Few economies are

likely to have significant information to report for every

standarditem.Furthermore,dataforseveralcomponents

may be available only in combination, or a minor com-

ponentmaybegroupedwithonethatismoresignifi-

cant. The standard items should nevertheless be reported

totheIMFascompletelyandaccuratelyaspossiblein

accordance with the compilation framework. Compilers

areinbetterpositionsthanIMFstafftomakeestimates

andadjustmentsforitemsthatdonotexactlycorrespond

to the basic series of the compiling economy.

C. History of the Manual

1.17 Each new edition of the Manual is introduced

in response to economic and financial developments,

changesinanalyticalinterests,andaccumulationof

experience by compilers.

1.18 TheIMFshowedearlyinterestinstatistical

methodologywithitspublicationofthefirsteditionof

the Balance of Payments Manual in January 1948. The

major objective of that first Manual wastoprovidea

basis for regular, internationally standardized reporting

totheIMF.TheManual wasacontinuationofwork

startedbytheLeagueofNationstodevelopguide-

lines for balance of payments statistics. Economists and

other specialists from many countries contributed to

the Manual, and representatives of some 30 countries

and international organizations met in Washington,

D.C.,inSeptember1947tofinalizethefirstdraftof

the Manual.

1.19 ThefirsteditionoftheManual consisted pri-

marily of tables for reporting data and brief instruc-

tionsforcompletingthem.Nogeneraldiscussionof

balance of payments concepts or compilation methods

wasincluded,soitcanbesaidthattheManual grew out

of the listing of standard components.

1.20 The second edition was published in 1950,

greatlyexpandingthematerialdescribingtheconcepts

of the system.

1.21 The third edition was issued in 1961. It moved

beyond the previous editions by providing both a basis

for reporting to the IMF and a complete set of balance

of payments principles that could be used by countries

to serve their own needs.

1.22 The fourth edition was published in 1977.

Itrespondedtotheimportantchangesinthewayin

which international transactions were carried out and

to changes in the international financial system. Much

fullertreatmentsoftheunderlyingprinciplesofresi-

dence, valuation, and other accounting principles were

provided. The Manual also introduced flexibility in the

use of the standard components to construct various

balances, with no single presentation preferred.

1.23 ThefiftheditionwaspublishedinSeptem-

ber1993,followingalongperiodofdevelopmentthat

includedexpertgroupmeetingsconvenedbytheIMF

in1987and1992aswellastwoworkingpartiescover-

ingthecurrentandfinancialaccounts.Thiseditionwas

markedbyharmonizationwiththeSystem of National

Accounts 1993 (1993 SNA),whichwasdevelopedatthe

sametime.Thedecisiontoharmonizetheguidelines

wasaresultofincreasinginterestinlinkingdiffer-

ent macroeconomic data sets and avoiding data incon-

sistencies. BPM5 broughtaboutanumberofchanges

in definitions, terminology, and the structure of the

accounts, including removing capital transfers and non-

producedassetsfromthecurrentaccounttoanewly

designated capital account, the renaming of the capi-

talaccountasthefinancialaccount,andsplittingser-

vices from primary income (which previously had been

called factor services). Additionally, BPM5 introduced

microfoundations of units and sectors, consistent with

the SNA,ratherthantreatingtheeconomyasasingle

unit.Inaddition,theManual wasextendedbeyondbal-

ance of payments statistics to include the international

investment position.

1.24 The IMF subsequently published the Monetary

and Financial Statistics Manual 2000 and Government

Financial Statistics Manual 2001. These manuals also

brought about further harmonization of the statistical

guidelines,reflectingincreasingconcernsaboutthe

ability to link different statistical data, minimizing data

inconsistency, and enhancing analytical potential.

1.25 In1992,theIMFestablishedtheIMFCommit-

tee on Balance of Payments Statistics (the Committee),

as a continuing body for consultation with national

compilers and international organizations. A procedure

wasestablishedforpartialrevisionsofstatisticalguide-

lines between major revisions, as was done in the late

1990s for financial derivatives and aspects of direct

investment. (The procedures for partial revisions are

setoutinSectionE.)

Chapter 1 g Introduction

4

1.26 A number of related publications have been

developed since the 1993 edition. The Balance of Pay-

ments Compilation Guide was published in 1995. The

Guide complemented the Manual by providing practi-

cal advice on the collection and compilation of statis-

tics. The Balance of Payments Textbook was released

in 1996. It has a teaching orientation, for instance, giv-

ing numerical examples to illustrate general principles.

1.27 Some aspects of international accounts statis-

tics with particular interest were covered in specialized

guides. Those guides are Coordinated Direct Investment

Survey Guide (2008), Coordinated Portfolio Investment

Survey Guide (1996 and 2001), International Reserves

and Foreign Currency Liquidity: Guidelines for a Data

Template (2000), Manual on Statistics of International

Trade in Services (2002), External Debt Statistics:

A Guide for Compilers and Users (2003), Bank for

International Settlements Guide to the International

Banking Statistics (2003), International Transactions

in Remittances: Guide for Compilers and Users, and

the OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct

Investment (2008).

D. The 2008 Revision

1.28 At its 2001 meeting, the Committee decided

to initiate an update of the Manual by around 2008.

It was considered that although the overall frame-

work of the fifth edition did not need to change, a

new Manual should incorporate the numerous elabo-

rations and clarifications that had been identified

since 1993. Also, the sixth edition should strengthen

the theoretical foundations and linkages to other

macroeconomic statistics.

1.29 The Committee also decided to conduct the

update in parallel with the update of the 1993 SNA

and OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct

Investment.

1.30 The IMF released, through the Committee,

an Annotated Outline for the update of the Manual

in April 2004. It included proposals and options for

the style and content of the revised Manual. It was

circulated to central banks and statistical agencies,

as well as being made available on the Internet. Input

was invited from compilers and others on a global

basis. The Committee established technical expert

groups to undertake detailed consideration of issues

and make recommendations on currency unions,

direct investment, reserves, and other issues, respec-

tively. Draft versions of the Manual were published

on the IMF website in March 2007 and March 2008,

with invitations for worldwide comment. In addition,

other editions of selected chapters and the whole

document were circulated to Committee members

and other interested parties. A series of regional out-

reach seminars was conducted between January and

September 2008 to explain the changes in the Man-

ual and gain comments on the content. This process

led to a revised version submitted to the Committee

in November 2008.

1.31 Three major themes that have emerged

from the revision are globalization, increasing elabora-

tion of balance sheet issues, and financial innovation.

1.32 Globalization has brought several issues to

greater prominence. An increasing number of individ-

uals and companies have connections to two or more

economies and economies increasingly enter into

economic arrangements. In particular, there has been

increasing interest in the residence concept and in

information on migrant workers and their associated

remittance flows. Additionally, globalized production

processes have become more important, so treatments

have been developed to provide a fuller and more

coherent picture of outsourced physical processes (i.e.,

goods for processing) and sales and management of

manufacturing that do not involve physical posses-

sion (i.e., merchanting). Guidance is provided on the

residence and activities of special purpose entities and

other legal structures that are used for holding assets

and that have little or no physical presence. The results

of work on international trade in services and remit-

tances are included. Furthermore, for the first time,

specific guidance on the treatment of currency unions

is included.

1.33 The Manual reflects increased interest in bal-

ance sheet analysis for understanding international

economic developments, particularly vulnerability

and sustainability. Greater emphasis and elaboration

of the financial instrument classification in the SNA

and Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual are

designed to facilitate linkages and consistency. The

Manual provides considerably more detailed guid-

ance on the international investment position. It also

provides much greater discussion of revaluations and

other volume changes and their impact on the values

of assets and liabilities. The results of detailed work

over the past decade on international investment

position, direct investment, external debt, portfolio

investment, financial derivatives, and reserve assets

are incorporated into the new Manual. The move to

an integrated view of transactions, other changes, and

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT POSITION MANUAL

5

positions has been recognized in the amended title as

Balance of Payments and International Investment

Position Manual, with the acronym BPM6 used to

highlight the historical evolution from previous edi-

tions of the Manual, which were known as BPM5,

BPM4, and so on.

1.34 Financial innovation is the emergence and

growth of new financial instruments and arrangements

among institutional units. Examples of instruments

covered include financial derivatives, securitization,

index-linked securities, and gold accounts. An example

of institutional arrangements are special purpose enti-

ties and complex, multieconomy corporate structures.

Enhanced guidelines cover direct investment in cases

of long and complex chains of ownership, revised in

conjunction with the revised OECD Benchmark Defi-

nition of Foreign Direct Investment. Revised treat-

ments of insurance and other financial services are

adopted. The Manual also provides expanded treat-

ment on the issues of loan impairments, debt reorga-

nization, guarantees, and write-offs.

1.35 In addition, the Manual incorporates changes

arising from other statistical manuals, particularly the

2008 SNA. The harmonization with other macroeco-

nomic statistics is strengthened in terms of presentation

by more details on the underlying economic concepts

and their associated links with the equivalent parts of

the SNA and other manuals. Other changes were made

in response to requests to provide clarification or fur-

ther detail on particular topics.

1.36 The overall structure of the accounts and broad

definitions are largely unchanged in this edition, so the

changes are less structural than those made for the fifth

edition. Rather, economic and financial developments

and evolution of economic policy concerns are taken

into account, and clarification and elaboration of these

developments are provided. A list of changes made in

this edition of the Manual is included as Appendix 8.

E. Revisions between Editions of

the Manual

1.37 The IMF and the Committee have developed

procedures for updating the Manual on an ongoing

basis between major revisions. Under these procedures,

updates can be divided into four types:

(a) editorial amendments;

(b) clarifications beyond dispute;

(c) interpretations; and

(d) changes.

Each of these types of updates has a different set of steps

that are to be followed in the consultation process.

1.38 Editorial amendments refer to wording errors,

apparent contradictions, and, for non-English versions

of the Manual, translation errors. These corrections

affect neither concepts nor the structure of the system.

IMF staff will draft these amendments, which will be

brought to the Committee for advice. An errata sheet

will then be produced, and the amendments will be

publicized on the website.

1.39 A clarification beyond dispute arises when

a new economic situation emerges or when a situation

that was negligible when the Manual was produced has

become considerably more important, but for which

the appropriate treatment under existing standards is

straightforward. IMF staff will draft these clarifica-

tions, based on existing recommendations, and after

advice from the Committee, they will be publicized on

the website and by other means.

1.40 An interpretation arises when an economic

situation arises for which the treatment under the

Manual may not be clear. Several solutions on how

to treat the situation may be proposed, because it is

possible to have different interpretations of the Man-

ual. In this case, IMF staff, in consultation with the

Committee, will draft preliminary text that will be

sent to panels of experts, and to the InterSecretariat

Working Group on National Accounts (ISWGNA) (if

also relevant to the SNA). IMF staff will propose a

final decision, in consultation with the Committee.

Interpretations will be publicized on the website and

by other means.

1.41 A change to the framework arises when an

economic situation occurs in which it becomes appar-

ent that the concepts and definitions of the framework

are not relevant or are misleading and will require

change. In such a situation, parts of the Manual may

need to be substantially rewritten to reflect the needed

changes. In such a case, IMF staff, in consultation with

the Committee, will prepare proposals that will be dis-

seminated widely to panels of experts, the ISWGNA (if

also relevant to the SNA), and all IMF member coun-

tries. The Committee will advise how such changes

should be incorporated into the framework, whether

promulgated immediately through a booklet detailing

the amendments to the Manual or by issuing a new

Manual. Information will be produced and provided to

all countries with changes also publicized on the IMF

website and by other means.

Chapter 1 g Introduction

6

1.42 TheIMFwebsitewillprovideaconsolidated

list of these decisions.

1.43 A research agenda has been identified for pos-

siblefuturework.Itincludesthefollowing:

(a) ultimate investing economy and ultimate host

economyindirectinvestment(seeparagraph

4.156);

(b) whether direct investment relationships can be

achievedotherthanbyeconomicownership

ofequity(e.g.,throughwarrantsorrepos)(see

paragraph 6.19);

(c) pass-through funds (see paragraphs 6.33–6.34);

(d) reverse transactions (including short positions

and investment income that is receivable/pay-

ablewhileasecurityison-lent)(seeparagraphs

5.52–5.55, 7.28, 7.58–7.61, and 11.69);

(e) extendeduseoffairvaluesofloans(seepara-

graphs 7.48–7.49);

(f) how the risk and maturity structure of the finan-

cial assets and liabilities should be taken into

account in the reference rate for calculations of

financialservicesindirectlymeasured(seepara-

graphs 10.126–10.136);

(g) investment income, in particular the differ-

ent treatments of retained income for different

investmenttypesandtheborderlinebetween

dividends and withdrawal of equity (see Chapter

11, Primary Income Account);

(h) debt concessionality, in particular whether the

transfer element should be recognized and, if so,

howitshouldberecorded(seeparagraphs12.51

and 13.33); and

(i) emissions permits (see paragraph 13.14).

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT POSITION MANUAL

7

CHAPTER

2

Overview of the Framework

A. Introduction

2.1 This chapter first describes and illustrates how

theinternationalaccountsareanintegralconceptual

part of the broader system of national accounts. It then

covers important aspects of statistics such as time

series.

B. Structure of the Accounts

References:

2008 SNA, Chapter 2, Overview, and Chapter 16, Sum-

marizing and Integrating the Accounts.

IMF, The System of Macroeconomic Accounts Statis-

tics: An Overview,PamphletSeriesNo.56.

1. Overall framework

2.2 Theinternationalaccountsforaneconomysum-

marizetheeconomicrelationshipsbetweenresidents

ofthateconomyandnonresidents.Theycomprisethe

following:

(a) the international investment position (IIP)—a

statement that shows at a point in time the value

of:financialassetsofresidentsofaneconomy

thatareclaimsonnonresidentsoraregoldbul-

lion held as reserve assets; and the liabilities of

residents of an economy to nonresidents;

(b) the balance of payments—a statement that sum-

marizeseconomictransactionsbetweenresi-

dents and nonresidents during a specific time

period; and

(c) theotherchangesinfinancialassetsandlia-

bilities accounts—a statement that shows other

flows, such as valuation changes, that reconciles

the balance of payments and IIP for a specific

period, by showing changes due to economic

events other than transactions between residents

and nonresidents.

2.3 Theinternationalaccountsprovideanintegrated

framework for the analysis of an economy’s international

economic relationships, including its international eco-

nomic performance, exchange rate policy, reserves man-

agement, and external vulnerability. A detailed study

oftheuseofinternationalaccountsdataisprovidedin

Chapter 14, Selected Issues in Balance of Payments and

International Investment Position Analysis.

2.4 The framework provides a sequence of accounts,

eachoneencompassingaseparateeconomicprocessor

phenomenon,andshowsthelinkagesbetweenthem.

Whileeachaccounthasabalancingitem,theaccount

alsogivesafullviewofitscomponents.

2.5 The concepts of the international accounts are

harmonized with the System of National Accounts

(SNA), so they can be compared or aggregated with

other macroeconomic statistics. The framework for

macroeconomic statistics used in the SNA and interna-

tionalaccountsisshowninFigure2.1.

2.6 Theinternationalaccountsframeworkisthe

same as the SNA framework. However, some accounts,

which are shaded in Figure 2.1, are not applicable.

2.7 The framework is designed so that the core con-

cepts can be used to develop additional data sets, as

discussedinAnnex2.1tothischapter.

2. International investment position

2.8 The IIP is a statistical statement that shows at a

point in time the value of: financial assets of residents

of an economy that are claims on nonresidents or are

gold bullion held as reserve assets; and the liabilities

of residents of an economy to nonresidents. The differ-

encebetweentheassetsandliabilitiesisthenetposi-

tionintheIIPandrepresentseitheranetclaimonora

netliabilitytotherestoftheworld.

2.9 TheIIPrepresentsasubsetoftheassetsand

liabilitiesincludedinthenationalbalancesheet.In

8

addition to the IIP, the national balance sheet incorpo-

rates nonfinancial assets as well as financial assets and

liabilitypositionsbetweenresidents.Thisstatementis

described further in Chapter 7.

2.10 WhereastheIIPrelatestoapointintime,the

integrated IIP statement relates to different points in

time,andithasanopeningvalue(asatthebeginning

oftheperiod)andaclosingvalue(asattheendofthe

period). The integrated IIP statement reconciles the

openingandclosingvaluesoftheIIPthroughthefinan-

cial account (flows arising from transactions) and the

other changes in financial assets and liabilities account

(other volume changes and revaluation). So, the values

intheIIPattheendoftheperiodresultfromtrans-

actions and other flows in the current and previous

periods. The integrated IIP statement consists of the

accountsexplainedinChapters7–9(i.e.,theIIP,the

financialaccount,andtheotherchangesinfinancial

assets and liabilities account, respectively).

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT POSITION MANUAL

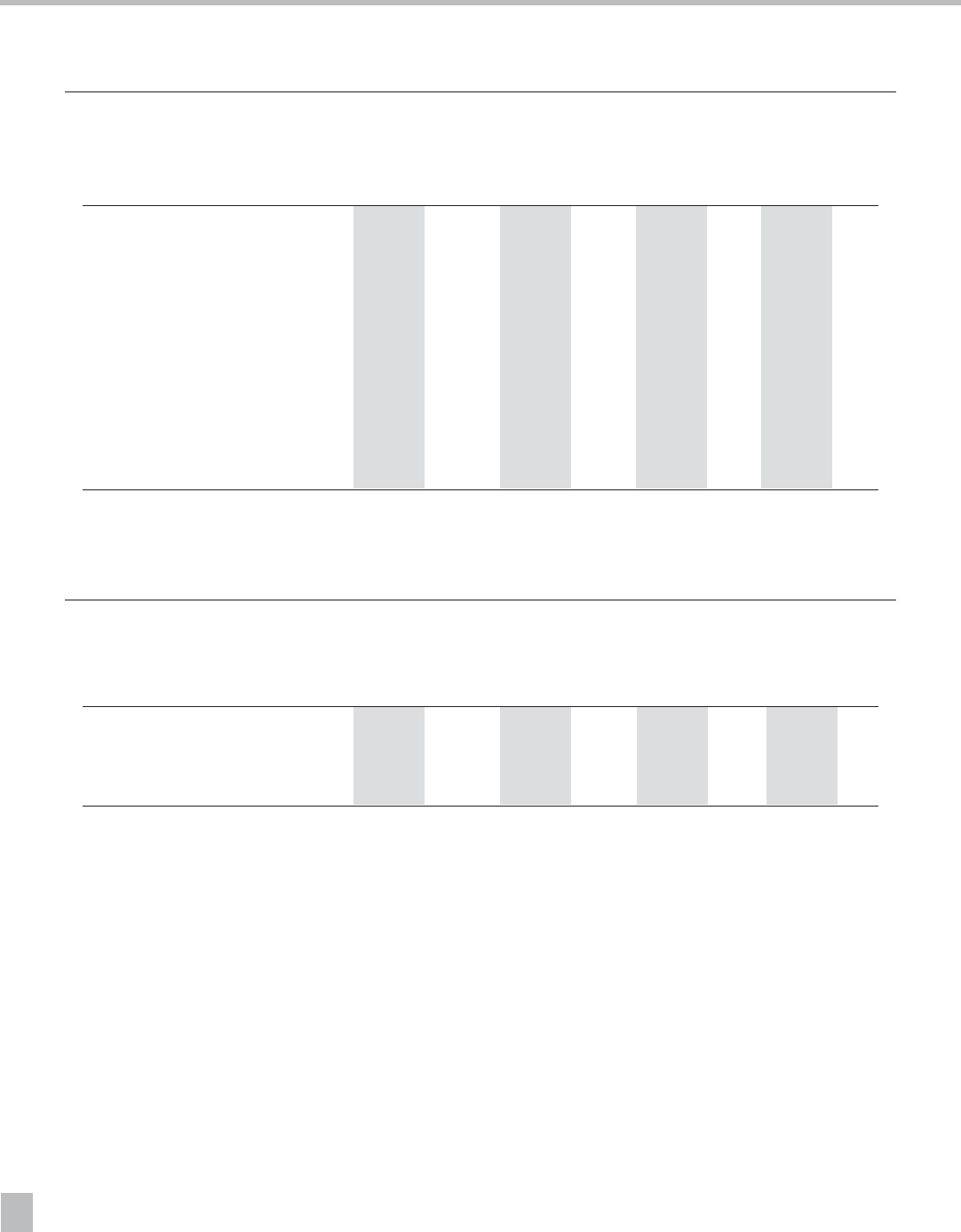

Transactions/Balance of payments:

Other flows:

Key:

Shaded accounts do not appear in the international accounts.

The arrows represent the contributions of assets to production and income generation (e.g., using nonfinancial assets as an input to production,

using financial assets to generate interest and dividends).

Figure 2.1. Overview of the System of National Accounts as a

Framework for Macroeconomic Statistics Including International Accounts

Goods and services

account

Production account

Value added/GDP

Generation of income

account

Operating surplus

Distribution of income

account

National income

Secondary distribution

of income account

Disposable income

Use of income account

Saving

Opening balance sheet

Financial assets and liabilities

Net worth

Accumulation accounts

Capital account

Net lending/net borrowing

Financial account

Net lending/net borrowing

Other changes in

financial assets and

liabilities

Net other changes

Closing balance sheet

Financial assets and liabilities

Net worth

Nonfinancial assets

Nonfinancial assets

Other changes in

nonfinancial assets

Name of account

SNA Balancing item

9

2.11 Thehighestlevelofclassificationusedinthe

IIP,financialaccount,andotherchangesinassetsand

liabilities account is the functional classification, which

iscoveredinChapter6.Thefunctionalcategoriesgroup

together financial instruments based on economic moti-

vations and patterns of behavior to assist in the anal-

ysis of cross-border transactions and positions. These

categories are direct investment, portfolio investment,

financial derivatives (other than reserves) and employee

stock options, other investment, and reserve assets. The

SNA doesnothavesuchcategories,preferringtorecord

financial account activity by type of instrument alone

(althoughdirectinvestmentisamemorandumitemto

the SNA instrument classification). Chapter 5 covers the

classificationoffinancialinstruments.

3. Balance of payments

2.12 The balance of payments is a statistical state-

ment that summarizes transactions between residents

and nonresidents during a period. It consists of the goods

and services account, the primary income account, the

secondary income account, the capital account, and

the financial account. Under the double-entry account-

ingsystemthatunderliesthebalanceofpayments,each

transactionisrecordedasconsistingoftwoentriesand

thesumofthecreditentriesandthesumofthedebit

entriesisthesame.(SeeBox2.1forfurtherelaboration

on the double-entry accounting system.)

2.13 Thedifferentaccountswithinthebalanceof

payments are distinguished according to the nature of

the economic resources provided and received.

Current account

2.14 The current account shows flows of goods, ser-

vices, primary income, and secondary income between

residents and nonresidents.Thecurrentaccountisan

importantgroupingofaccountswithinthebalanceof

payments. Its components are dealt with in the follow-

ing chapters:

• Chapter 10 discusses the goods and services

account. This account shows transactions in goods

and services.

• Chapter 11 discusses the primary income account.

This account shows amounts payable and receiv-

able in return for providing temporary use to

another entity of labor, financial resources, or non-

produced nonfinancial assets.

1

1

Allowinganotherentitytouseproducedassetsgivesrisetoa

service (see paragraph 10.153). In contrast, allowing another entity

• Chapter 12 discusses the secondary income

account. This account shows redistribution of

income, that is, when resources for current pur-

poses are provided by one party without anything

ofeconomicvaluebeingsuppliedasadirectreturn

to that party. Examples include personal transfers

and current international assistance.

2.15 The balance on these accounts is known as the

current account balance. The current account balance

showsthedifferencebetweenthesumofexportsand

incomereceivableandthesumofimportsandincome

payable(exportsandimportsrefertobothgoodsand

services, while income refers to both primary and sec-

ondaryincome).AsshowninChapter14,Selected

IssuesinBalanceofPaymentsandInternationalInvest-

ment Position Analysis, the value of the current account

balance equals the saving-investment gap for the econ-

omy. Thus, the current account balance is related to

understanding domestic transactions.

Capital account

2.16 The capital account shows credit and debit

entries for nonproduced nonfinancial assets and capital

transfersbetweenresidentsandnonresidents.Itrecords

acquisitions and disposals of nonproduced nonfinan-

cialassets,suchaslandsoldtoembassiesandsalesof

leases and licenses, as well as capital transfers, that is,

the provision of resources for capital purposes by one

party without anything of economic value being sup-

pliedasadirectreturntothatparty.Thisaccountis

described further in Chapter 13.

Financial account

2.17 The financial account shows net acquisition and

disposal of financial assets and liabilities. This account

is described in Chapter 8. Financial account transac-

tions appear in the balance of payments and, because

oftheireffectonthestockofassetsandliabilities,also

in the integrated IIP statement.

2.18 Thesumofthebalancesonthecurrentand

capitalaccountsrepresentsthenetlending(surplus)or

net borrowing (deficit) by the economy with the rest of

theworld.Thisisconceptuallyequaltothenetbalance

ofthefinancialaccount.Inotherwords,thefinancial

accountmeasureshowthenetlendingtoorborrowing

to use nonproduced nonfinancial assets gives rise to rent (paragraph

11.86) and allowing another entity to use financial assets gives rise

to investment income, such as interest, dividends, and retained earn-

ings (see paragraph 11.3).

Chapter 2 g Overview of the Framework

10

from nonresidents is financed. The financial account

plustheotherchangesaccountexplainthechangein

theIIPbetweenbeginning-andend-periods.

Gross and net recording

2.19 Thecurrentandcapitalaccountsshowtransac-

tions in gross terms. In contrast, the financial account

shows transactions in net terms, which are shown sepa-

rately for financial assets and liabilities (i.e., net trans-

actions in financial assets shows acquisition of assets

less reduction in assets, not assets net of liabilities).

Forresourcesthatenterandleaveaneconomy(such

asre-exportedgoods,andfundsintransit),itmaybe

analytically useful to present net flows as well. Each

oftheaccountsandtheborderlinesbetweenthemare

discussedinmoredetailinthespecificchapters.

4. Accumulation accounts

2.20 The accumulation accounts comprise the capi-

tal account, financial account, and other changes in

financial assets and liabilities accounts. They show the

accumulation (i.e., acquisition and disposal) of assets

and liabilities, their financing, and other changes that

affect them. Accordingly, they explain changes between

theopeningandclosingIIP/balancesheets.Whereas

the current account is concerned with resource flows

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT POSITION MANUAL

Recording for individual transactions

The recording of debits and credits underlies the account-

ingsystematthelevelofindividualtransactions.Eachtrans-

action in the balance of payments is recorded as consisting

of two equal and opposite entries, reflecting the inflow and

outflow element to each exchange. For each transaction, each

partyrecordsamatchingcreditanddebitentry:

• Credit (CR.)—exports of goods and services, income

receivable, reduction in assets, or increase in liabilities.

• Debit (DR.)—imports of goods and services, income

payable, increase in assets, or reduction in liabilities.

Examples

Asimpleexampleisforsaleofgoodstoanonresident

for100incurrency.Fortheseller:

Exports 100 (CR.)

Currency 100 (DR.—Increase in financial assets)

(The transaction involves the provision of physical

resourcestononresidentsandacompensatingreceiptof

financial resources from nonresidents.)

An example of a transaction involving only financial

asset entries is the sale of shares for 50 in currency. For

the seller:

Shares and 50 (CR.—Reduction in financial assets)

other equity

Currency 50 (DR.—Increase in financial assets)

(The selling party provides shares and receives cur-

rencyinreturn.)

An example involving the exchange of an asset for the

creationofaliabilityiswhereaborrowerreceivesaloan

of70incash.Fortheborrower:

Loan 70 (CR.—Increase in liabilities)

Currency 70 (DR.—Increase in financial assets)

(There are some more complex cases when three or

morepartiesareinvolved,e.g.,thecaseofdebtassump-

tion shown in Box 8.1.)

Aggregate recording

Inbalanceofpaymentsaggregates,thecurrentand

capital account entries are totals, while financial account

entries are net values for each category/instrument for

each of assets and liabilities (as explained in paragraph

3.31).Chapter3,AccountingPrinciples,PartCprovides

furtherinformationontheaccountingsystemusedinbal-

ance of payments statistics.

Asaresultofthetwo-entrynatureofeachtransaction,

thedifferencebetweenthesumofcreditentriesandthe

sumofdebitentriesisconceptuallyzerointhenational

balanceofpayments,thatis,inconcept,theaccounts

asawholeareinbalance.Asdiscussedinparagraphs

2.24–2.26, measurement problems cause discrepancies

in practice.

The two-entry nature of the balance of payments can

be presented in aggregate data in different ways. A pre-

sentationwherethenatureoftheentriesisconveyed

bythecolumnheadings(namely,credits,debits,net

acquisition of financial assets, and net incurrence of

liabilities) is adopted in Table 2.1. This presentation is

considered to be easily understood by users. Another

presentationiswherecreditentriesareshownaspositive

anddebitentriesasnegative.Thispresentationisuseful

forcalculatingbalances,butrequiresmoreexplanation

for users (e.g., increases in assets are shown as a nega-

tive value).

In the SNA presentation, a credit entry for the com-

pilingeconomyinthebalanceofpaymentscurrent

accountiscalledausebytherestoftheworldsector

(e.g.,exportsareusedbytherestoftheworld).Simi-

larly,adebitentryforthecompilingeconomyiscalled

provisionof“resources”intheSNA (e.g., imports are a

resourceprovidedbytherestoftheworld).Becausethe

SNA rest of the world accounts use the point of view of

thenonresidents,assetsofthecompilingeconomyinthe