Cross-Border Trade and

Corruption along the

Haiti-Dominican Republic

Border

MARCH 2019

PROJECT DIRECTOR

Michael Matera

LEAD AUTHOR

Mary Speck

CO-AUTHORS

Linnea Sandin

Mark Schneider

A Report by the

CSIS AMERICAS PROGRAM

Cross-Border Trade and

Corruption along the

Haiti-Dominican Republic

Border

PROJECT DIRECTOR

Michael Matera

LEAD AUTHOR

Mary Speck

CO-AUTHORS

Linnea Sandin

Mark Schneider

A Report by the

CSIS AMERICAS PROGRAM

MARCH 2019

i

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

Acknowledgments

is report is made possible by the support of the American

people through the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID.) e contents of this report are the sole

responsibility of CSIS and do not necessarily reflect the views

of USAID or the United States Government.

Cette rapport est rendue possible grâce au soutien du peuple

Américain par l’intermédiaire de l’Agence Américaine pour le

Développement International (USAID). Le contenu de cette

rapport relève de la seule responsabilité de CSIS et ne reflète

pas nécessairement les vues de l’USAID ou du gouvernement

des États-Unis.

e authors would like to thank the Americas Program sta

and aliates and the CSIS iLab team for their support on this

project, especially Sarah Baumunk, Mia Kazman, Arianna Ko-

han, Georges Fauriol, David Lewis, Jeeah Lee, Emily Tiemeyer,

and William Taylor. e authors would also like to thank those

in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Washington, D.C. who

provided valuable input on the report and support throughout

our research process.

About CSIS

Established in Washington, D.C., over 50 years ago, the

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)

is a bipartisan, nonprofit policy research organization

dedicated to providing strategic in sights and policy

solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a

better world.

In late 2015, omas J. Pritzker was named chairman

of the CSIS Board of Trustees. Mr. Pritzker succeeded

former U.S. senator Sam Nunn (D-GA), who chaired the

CSIS Board of Trustees from 1999 to 2015. CSIS is led

by John J. Hamre, who has served as president and chief

executive ocer since 2000.

Founded in 1962 by David M. Abshire and Admiral

Arleigh Burke, CSIS is one of the world’s preeminent

international policy in stitutions focused on defense and

security; regional study; and transnational challenges

ranging from energy and trade to global development

and economic integration. For eight consecutive years,

CSIS has been named the world’s number one think tank

for defense and national security by the University of

Pennsylvania’s “Go To ink Tank Index.”

e Center’s over 220 full-time sta and large network

of aliated schol ars conduct research and analysis

and develop policy initiatives that look to the future

and anticipate change. CSIS is regularly called upon

by Congress, the executive branch, the media, and

others to explain the day’s events and oer bipartisan

recommendations to improve U.S. strategy.

CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly,

all views expressed herein should be understood to be

solely those of the author(s).

© 2019 by the Center for Strategic and International

Studies. All rights reserved

1

Summary

An economic chasm separates the two countries sharing

the island of Hispaniola. Until the mid-twentieth century,

both had roughly the same GDP, but while the Dominican

Republic (DR) has enjoyed decades of economic growth,

Haiti’s economy has languished, crippled by political tur-

moil and natural disasters. Although both countries have

roughly the same population—nearly 11 million—the DR’s

economy is ten times bigger.

Largely uncontrolled cross-border trade highlights these

dierences, straining bilateral relations. Exports from the

Dominican Republic worth hundreds of millions of dollars

enter Haiti illegally each year, depriving the government

of revenues needed to create jobs and provide basic ser-

vices and stifling the growth of Haiti’s own agricultural and

industrial sectors. Meanwhile, Haitians—unable to find

employment, education, or health care at home—cross into

the DR, swelling the country’s undocumented population.

Attempts by both governments to curb these flows—by

banning certain types of cross-border trade or deporting mi-

grants —have done little but encourage corruption. Haitian

customs agents—bribed or intimidated by powerful parlia-

mentarians and businesspeople—allow importers to bring

shipments across the border without proper inspections.

Dominican soldiers let Haitian workers or traders cross the

border only if they pay “tolls” to avoid deportation.

Eective, ecient border regulations would benefit both

countries. Haiti needs Dominican products and know-how;

the Dominican Republic needs Haitian workers and foreign

market access. Facilitating formal trade would stimulate

investment, creating jobs on both sides of the border. It

would also increase the tax revenues needed as Haiti copes

with declining foreign assistance.

Both governments are navigating mega-corruption scan-

dals. Dominican ocials reportedly took bribes from Ode-

brecht, a Brazilian engineering company; Haitians allegedly

misused funds provided under PetroCaribe, Venezuela’s oil

alliance. In Haiti, these allegations threaten government

stability: violent protests shut down businesses, govern-

ment oces, and schools in Port-au-Prince for more than a

week in February, cutting o access to food and health care.

Cross-border commerce is especially important for resi-

dents of impoverished communities along both sides of the

border. Tens of thousands of people trade at 14 border mar-

kets, nearly all of which are located inside the Dominican

Republic. Few locally produced goods are traded, however,

so the markets do little to help local farmers move up the

value chain from subsistence to commercial farming.

e good news is that Haiti and the DR have in recent years

signed agreements to combat contraband and customs

fraud at their borders and to explore joint development

projects. e bad news is that these measures exist only on

paper. Haiti’s political instability is one reason they have

not been implemented; mistrust between the two govern-

ments is another.

Nonetheless, there are glimmers of progress. Successful pri-

vate ventures—such as the CODEVI industrial park, which

produces textiles for export under U.S. trade preferences—

demonstrate the border region’s potential for near-sourcing

job-creation. Donor-funded programs to train and equip

public ocials—such as providing customs ocials with

digital technology—should make Haitian institutions more

transparent and ecient. Projects focused on the border-

lands aim to improve the capacity of local government and

encourage the creation of local value-chains.

is report briefly examines the two countries’ divergent

economic fortunes and then looks at the conditions along

the border, including the problems of irregular trade, lost

revenues, corruption, and border poverty. Our research

has also identified a series of recommendations that could

help increase customs revenues and combat corruption

while also strengthening border security and fostering local

development. Both countries could benefit from adopting

anti-corruption practices and emulating cross-border pro-

grams that have proven successful elsewhere in the Amer-

icas. But these eorts will only succeed if the public and

private sectors in both countries overcome mutual mistrust

and commit to working together.

Success also requires sustained support from the inter-

national community, which should provide additional

financing, oversight, and training. To address entrenched

corruption-- especially within Haitian customs and the

Dominican military -- both countries should consider en-

listing multilateral help to create independent investigative

and prosecutorial capacity.

2

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

Detailed recommendations, directed at both governments,

the private sector, and donors, appear below. ey have

four fundamental objectives:

1) Building Trust. is should include regular presidential

and cabinet-level meetings, the implementation of joint

programs to address common problems along the border,

and the promotion of local cross-border associations.

2) Combatting corruption. Haiti should prioritize customs

reform while the Dominican Republic must address corrup-

tion within security forces stationed along the border.

3) Facilitating formal trade. Dominican and Haitian

customs agencies should digitize and share invoices and

customs declarations. Border markets should operate on

both sides of the border.

4) Promoting development in the border region. Both

countries should work with donors to create a cross-border

fund to stimulate economic growth, provide social services,

strengthen security, and protect the environment.

Recommendations

FOR THE HAITIAN AND DOMINICAN GOVERNMENTS

To build trust:

• Hold annual or biannual summits to build trust and

discuss concrete measures to regulate trade and

migration. e two presidents should also establish

mechanisms for fluid high-level communications, such

as a hotline between their oces and joint cabinet

meetings to discuss bilateral commerce, security, and

development.

• Reinvigorate the Mixed Bilateral Commission to pro-

pose, monitor, and implement joint measures on trade,

migration, energy, and the environment, including

establishing permanent oces in both countries.

• Continue donor-initiated eorts to create local

cross-border associations to prevent conflict; promote

mutual problem-solving and development; and build

understanding through joint cultural, educational, and

athletic events.

• Provide bona fide residents of the border region with

identification documents that permit travel for trade,

employment, education, or health care.

To facilitate formal trade:

• Establish a schedule for implementing bilateral agree-

ments on real-time digital sharing of invoices and cus-

toms declarations between the two customs agencies.

• Explore joint sanitary and phytosanitary standards

through discussions with agricultural and food safety

ocials from both countries as well as producers and

traders.

• Provide language training (Spanish, French, and Creole)

for customs and immigration ocers, security forces,

and other public ocials along the border. is should

also include training to ensure respect for citizens’

rights and discourage discrimination and abuse.

• Start the process of co-locating customs, immigration,

and police ocers from both countries within joint

facilities at each of the four ocial border crossings.

To promote border development:

• Relaunch eorts to elaborate a joint border devel-

opment plan that identifies and supports binational

business initiatives and public-private partnerships,

such as those designed to promote the near-sourcing of

manufacturing operations closer to the U.S. market.

• Continue working with donors on binational eorts to

ensure food security and combat malnutrition along

both sides of the border by helping small farmers

increase the production of higher value crops, prevent

soil erosion, and bring their produce to market.

FOR THE HAITIAN AND DOMINICAN PRIVATE SECTORS

To promote development and combat corruption:

• Convene a convention of business leaders from both

countries to discuss measures to facilitate trade and

promote development within the border region, such

as joint eorts to attract investment by manufacturers

interested in near-sourcing goods for the U.S. market.

• Work with the Mixed Bilateral Commission and its sub-

committees to promote trade, combat corruption, and

stimulate development along the border.

• Launch public anti-corruption campaigns and promote

transparent business practices through industry associ-

ations and chambers of commerce in both countries.

• Establish mechanisms for business owners and con-

sumers to report corrupt practices within the public

and private sectors, such as confidential email address-

es or telephone lines operated by business associations

within the two countries.

• Work with their respective customs agencies to estab-

lish an authorized trader system whereby those with

a record of compliance (certified by independent tax

auditors) enjoy expedited processing .

FOR THE HAITIAN GOVERNMENT

To combat corruption within the customs agency:

• Insulate customs from political interference by estab-

lishing an independent board of directors and man-

dating yearly auditing by an international financial

institution, such as the IMF.

• Assure merit-based recruitment and promotion by us-

ing competitive entrance exams and requiring customs

3

agents to fill out periodic asset declaration forms.

• Identify and confiscate illegally imported goods by

strengthening the capacity of customs to set up check

points along major highways and to spot-check inven-

tory held at warehouses.

• Minimize discretionary decisions at the border by im-

plementing a risk-based inspections regime and requir-

ing pre-arrival, online declarations, and tax payments.

• Publish annual reports listing all companies, organiza-

tions, and individuals receiving customs exemptions;

the purpose of these benefits; and their fiscal and

economic impact.

• Encourage private-sector compliance by instituting an

authorized trader system whereby those with a record

of compliance (certified by independent tax auditors)

enjoy expedited customs procedures.

• Give the customs agency a measure of financial autono-

my by granting it a percentage of gross customs receipts

to be used to increase salaries and strengthen operations.

• Appoint a special prosecutor to investigate customs

fraud by government ocials and private individuals

or companies.

To strengthen border security:

• Increase the presence of Polifront at border crossings.

• Ensure the rapid deployment of Polifront and other po-

lice units operating along the border by providing them

with all-terrain vehicles and boats.

• Enhance border surveillance capabilities.

FOR THE DOMINICAN GOVERNMENT

To combat corruption and abuse:

• Appoint a special prosecutor with the power to investi-

gate and prosecute alleged corruption and human rights

abuses by security forces along the border.

• Locate Creole-speaking ombudsmen within border

areas and empower them to document abuse against

migrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent.

• Provide human-rights training for security forces and

public ocials along the border.

• Establish an orderly deportation/repatriation process for

Haitian citizens in cooperation with Haitian authorities.

FOR MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENTS ALONG THE BORDER

To facilitate formal trade:

• Open binational markets on the Haitian side of the bor-

der, perhaps alternating days of operation with those in

the DR.

• Establish binational commissions whose members

are elected by the traders themselves to help manage

market operations, reduce tensions, and encourage the

collection of taxes or fees. ese commissions should

provide anonymous hotlines or other means for traders

to report corrupt demands by civilian, police, or mili-

tary ocials on either side of the border.

• Encourage credit cooperatives and other financing

opportunities for traders at the border markets so they

can reduce operating costs and diversify or expand

product lines.

FOR DONORS AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY

• Continue technical assistance and funding to help Hai-

tian ocials install, use, and maintain the Automated

System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) at all customs

oces and industrial parks and to ensure a smooth

interface with Dominican customs.

• Condition overall external budgetary support on the

implementation of DR-Haiti protocols providing for

online data sharing of invoices and other documents

between the two agencies, along with other measures

to ensure transparency and combat corruption.

• Strengthen the capacity of both countries to share

information and coordinate eorts to fight corruption

along the border. Provide support to allow governments

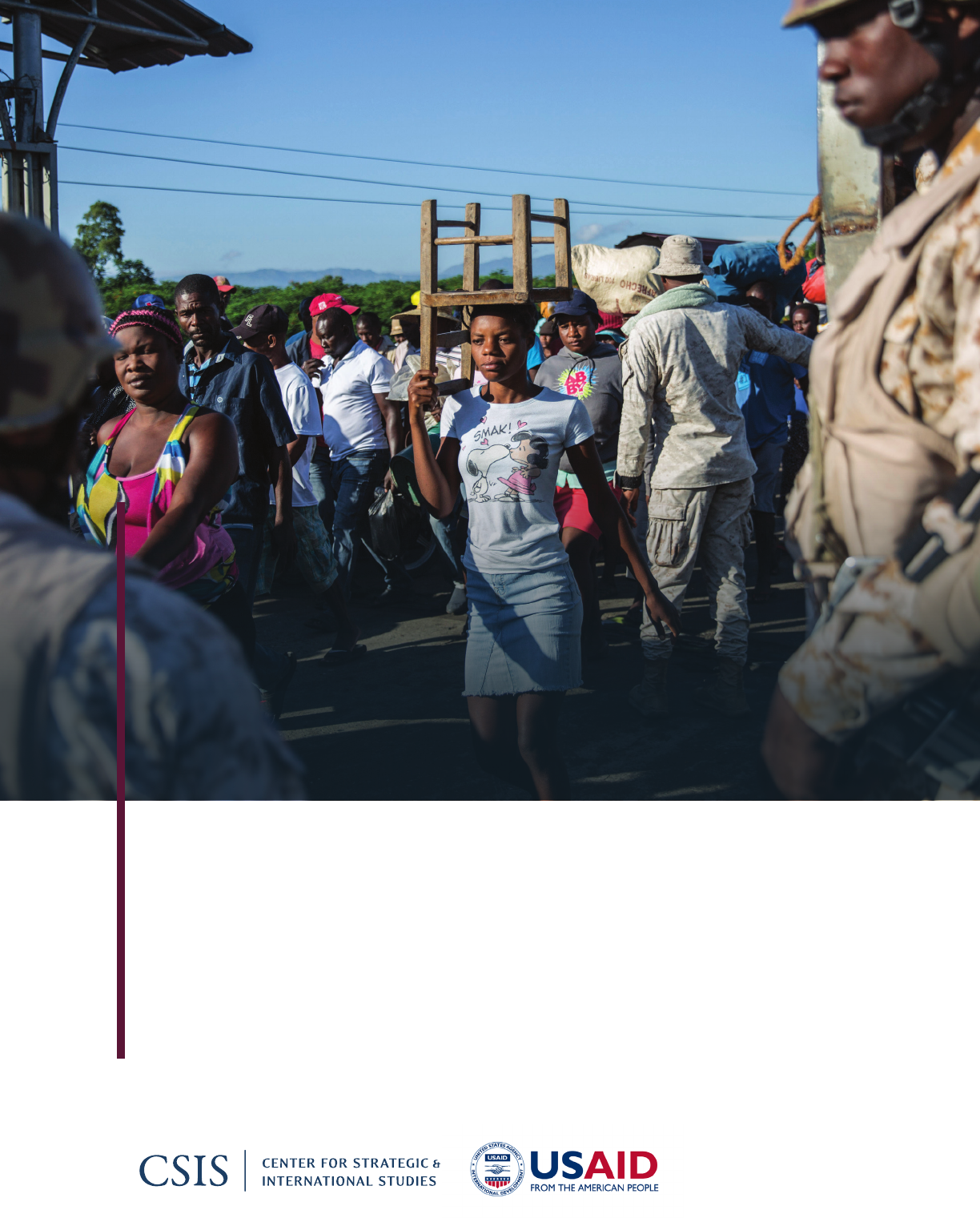

“DR Border Market”: Haitians crossing the border at Dajabon to

participate in the bi-weekly border market. Photo: Linnea Sandin

4

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

markets located at the two countries’ four ocial border

crossings. While Dajabón attracts the greatest number of

participants, the market at Jimaní, across from the Haitian

town of Malpasse in the southern corridor handles the

largest volume of merchandise given its proximity to Port-

au-Prince, which is less than two hours away by road. e

Elías Piña/Belladère market in the central corridor handles

the next-largest volume of trade followed by Pedernales/

Anse-à-Pitres, two isolated fishing villages on the south-

ern coast.

3

ere are also hundreds of other small (albeit

unocial) markets located at about a dozen points along

the border.

More than 180,000 buyers and sellers participate in the

border markets, according to a 2010 census, including about

95,000 Dominicans and 86,000 Haitians. Nearly all these

markets—including the four located at ocial crossings—lie

on the Dominican side of the frontier.

4

e market is bina-

tional in name only: goods mainly flow from the DR to Haiti,

with most entering the country as contraband not subjected

to duties. Informal trade into Haiti and irregular migration

into the Dominican Republic breed fraud on both sides of

the border. In Haiti, corrupt ocials—allegedly backed by

powerful politicians, especially parliamentarians represent-

ing border districts—ignore contraband. In the Dominican

Republic, military ocers reportedly enrich themselves by

demanding payment from those entering the country as

unlicensed vendors or undocumented workers.

Both countries would benefit from strengthening and regu-

larizing trade and labor along their common border. Mistrust

and prejudice—exacerbated by the two neighbors’ enormous

economic divergence—have undermined the political will

needed for sustained bilateral cooperation.

is report examines the divergent economic development

of the two countries; their asymmetric trade relations; and

the impact of illegal trade on industry, government finances,

and institutions. It explores ways to regularize and strength-

en the border while also stimulating the trade that is vital

for economic development in both countries. CSIS experts

conducted interviews with more than a dozen ocials and

experts in Washington, DC. e team also spent two weeks

in Haiti and the Dominican Republic interviewing govern-

ment ocials, business leaders, and development experts in

Port-au-Prince and Santo Domingo and visiting the customs

oce at Malpasse, Haiti, the border market in Dajabón, Do-

minican Republic, and the free zone in Ouanaminthe, Haiti.

and civil society representatives from within the region

(Chile, Uruguay, Colombia) to take the lead in oering

technical assistance and sharing best practices.

• Fund cross-border projects to promote economic de-

velopment, provide social services, strengthen security,

and protect the environment.

• Jointly establish a cross-border development fund that

includes the extension of credit to encourage export

agriculture and provide insurance or other instruments

to minimize risk.

• Define a plan for expanding Polifront border police

with continuing support from Canada, the United

States, and (while it remains in Haiti) MINUJUSTH.

• Help security forces in both countries establish joint

centers for information-sharing and conduct joint

surveillance.

Introduction

e bridge spanning the river that divides the commune

of Ouanaminthe in Haiti from the town of Dajabón in the

Dominican Republic opens to pedestrian trac every Monday

and Friday at 8 a.m. Haitians rush through the metal border

gates, jostling toward the market pavilion located less than

a hundred meters inside the DR. Some carry bags filled with

goods—mostly imported products, such as used clothing, toi-

letries, rice, or garlic—that they hope to sell, but the majority

come ready to haul merchandise away, pulling empty carts,

pushing wheelbarrows, or balancing plastic crates or basins on

their heads.

e market is a hive of economic activity that has generated

growth on both sides of the border. Vendors cram the two-sto-

ry building and a warren of stalls located outside, selling fresh

produce plus a wide array of other goods: cartons of eggs,

sacks of flour, bottled water and soft drinks, clothing and

shoes, plastic furniture, and non-prescription medicines.

anks largely to Haitian trade, the municipality of Dajabón

has expanded from about 28,000 people in 2010 to more than

40,000 in 2018, according to local estimates.

1

Just across the

Massacre River, the district of Ouanaminthe has grown even

more rapidly, swelling to an estimated population of more

than 100,000.

2

But this rapid growth also generates tensions: Haitians resent

the flood of goods that bypass customs, thereby depriving the

government of the revenues needed to provide basic ser-

vices and infrastructure. Dominicans want access to Haitian

consumers and Haitian labor but fear the growing Haitian

population along their border will spill into their country as

undocumented immigrants.

e Dajabón/Ouanaminthe market, located in the northern

corridor of the island of Hispaniola, is one of four biweekly

Mistrust and prejudice—exacerbated

by the two neighbors’ enormous

economic divergence—have undermined

the political will needed for sustained

bilateral cooperation.

5

CSIS began focusing on the problem of illegal trade be-

tween Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 2017. e US-

AID Mission in Haiti provided the funding for this report.

See Methodology, p. 14

Divergent Fortunes

e two nations that split the island of Hispaniola share

similarly turbulent histories from the sixteenth through

the early twentieth centuries. Both suered three centuries

under colonial rulers who quickly wiped out most of the

indigenous Taino population, replacing them with African

slaves to work the island’s ranches, mines, and plantations.

Haiti, the wealthier colony, gained independence from

France in 1804—17 years before the eastern side of the

island broke away from Spain—becoming the world’s first

black republic. Haitian forces unified the island—by occupy-

ing eastern Hispaniola and freeing its slaves—from 1822 to

1844.

5

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

both countries endured political turmoil, bankruptcy, and

U.S. occupation followed by decades of dictatorship: in the

DR, Rafael Trujillo ruled from 1930 until 1961; in Haiti, the

Duvalier dynasty—François (“Papa Doc”) and his son Jean-

Claude (“Baby Doc”)—held power from 1957 to 1986.

Until the mid-twentieth century, the two sides of Hispaniola

were also similarly poor. In 1960, the DR and Haiti had about

the same GDP per capita; by 2005, the DR’s had tripled while

Haiti’s had halved.

6

at gap has continued to widen over the

past decade: while economic growth in the DR has averaged

nearly 6 percent a year—one of the fastest rates in the Amer-

icas—Haiti’s has barely exceeded 2 percent a year.

7

Today,

the DR has an average per capita income of about $7,000,

still below the Latin American/Caribbean average ($9,000)

but nearly ten times Haiti’s ($765). Haiti is poor even by

the standards of the world’s poorest continent: its average

income is about half that of sub-Saharan Africa ($1,554).

8

What explains this divergence? Politics and nature have both

contributed to Haiti’s relative decline. While the Dominican

Republic has enjoyed decades of relatively stable, busi-

ness-friendly governments, Haiti has endured continuing

political unrest and frequent natural disasters. Since 1986,

Haiti has had 12 changes of government, including four mil-

itary takeovers plus two foreign interventions by U.S. forces

(1994–95) and UN peacekeepers (2004–2017).

9

During the

same period, the DR has had five changes of government,

all of which took place via mostly-peaceful elections.

10

Haiti

also endured a trade embargo imposed by the Organization

of American States (OAS) in the early 1990s after a military

coup deposed the first elected government after the Duvalier

dictatorship. Manufacturing, which depended on exports to

the United States, declined abruptly, from 18 percent of GDP

in 1990 to 10 percent of GDP in 1994.

11

en in January 2010—just as the elected government of

President René Préval seemed to be achieving a measure of

political peace and economic recovery following the turmoil

of President Aristide’s return and then second ouster—na-

ture dealt Haiti another blow with an earthquake that left

more than 200,000 dead and an estimated $8–13 billion in

damages.

12

Following the quake came two years of drought, a

cholera epidemic, and a 2016 hurricane that destroyed much

of the island’s agricultural production.

13

Small wonder that Haiti’s education and health levels are

worse than those next door: Haiti’s literacy rate is 77 per-

cent (DR: 92 percent), the mortality rate for children under

5 years old is 69 per 1,000 births (DR: 26 per 1,000 births),

and maternal mortality is 359 per 100,000 births (DR: 92 per

100,000 births).

14

Asymmetric Commerce

roughout much of the twentieth century, there was little

formal commerce between Haiti and the Dominican Repub-

lic. e border itself remained disputed until 1929, when

under pressure from the United States—which occupied

Haiti from 1915 to 1934 and the DR from 1916 to 1924—

the two countries signed a border treaty that was revised in

1936 to set the present frontier. Isolated from both Port-au-

Prince and Santo Domingo, the borderlands evolved into a

bilingual, bicultural region where Haitian and Dominican

families mingled and intermarried. Some Haitians became

0 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 700,000 800,000 900,000

Exports to Haiti

Imports from Haiti

Dominican Republic: Imports & Exports (thousands of USD)

Source: Trademap-Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (Kotra)

6

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

argues that this lost revenue would have been more than

enough to cover the country’s 2015 fiscal deficit.

24

is unregulated merchandise enters Haiti not only with-

out being taxed but also without facing sanitary inspec-

tions. e importation of chicken meat and eggs from the

DR is an especially contentious issue, given the nascent

Haitian poultry industry and its potential to generate

jobs and income in rural areas.

25

e Haitian government

banned poultry products from the DR in 2013, citing the

danger of avian flu, over the Dominican government’s

vigorous protests.

26

e ban was ineective, whether or not it was merited.

According to a Haitian producer, trucks continue to enter

Haiti via Malpasse “full of eggs, floor to ceiling.”

27

e

DR exports about one million eggs into Haiti every day,

according to one estimate, all of which enter without pay-

ing duty or passing inspection.

28

e trade is particularly

intense in the tourism o-season, when DR egg producers

allegedly dump excess production next door.

29

Such unregulated trade further undermines Haitian

enterprises that are already struggling to survive amid

widespread poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and

political uncertainty. e DR’s poultry industry employs

about 170,000 people; Haiti’s employs only 6,000 but

could potentially employ three times that number, plus

hundreds of thousands more in related industries, such as

feed production and distribution.

30

“ere is no way a country like Haiti can build an indus-

try without some breathing room,” said an executive with

Jamaica Broilers, which would like to expand operations

in Haiti. “e DR protects its own poultry industry while

undermining the one here.”

31

In October 2015, the Haitian Ministry of Economy and

Finance (MEF) attempted to limit cross-border trade by

banning the importation by land of 23 more products,

ranging from foodstus (including wheat flour, cooking

oil, biscuits, pasta, bottled water, and beer) to construction

materials (such as cement, rebar, and heavy equipment,

whether sold or rented). In addition to citing quality con-

trol and security, the ministry said the measure’s objective

was to “recover the hundreds of millions of fiscal revenues

lost to contraband” by forcing exporters to send goods

through the country’s ports, where they were more likely to

face inspection.

32

elite members of Dominican communities as businesspeo-

ple, professionals, and property owners.

15

at cooperation ended tragically in 1937 when President

Trujillo decided to secure control of the border region by

cleansing it of Haitians. Soldiers under Trujillo’s direct com-

mand killed an estimated 15,000 people, forcing thousands

more to flee communities where many had lived for gener-

ations.

16

For the next 50 years, the border remained closed

to most commerce, though the Dominican government

continued to allow plantation owners to bring Haitians

across the border to harvest sugarcane.

17

e two governments signed an agreement in 1987 to

reopen the border, but trade started to grow only after

1991, when the DR openly defied the OAS embargo (on the

grounds that desperate Haitians might cross the border as

refugees) by allowing cross-border trade.

18

Bilateral trade

grew slowly in the 1990s, however. By 2001, there was still

only a small trade deficit—less than $100 million—in the

DR’s favor.

Over the next 12 years, however, Haitian imports surged—

from $208 million in 2002 to more than $1 billion in

2013—while exports barely budged. In 2015, the Domini-

can Republic ocially exported about $1 billion to Haiti but

imported only $4 million from it.

19

Since then Dominican

exports have fallen as Haiti took steps to ban certain prod-

ucts (see below). e bilateral trade deficit remains huge,

however. In 2017 the DR’s exports to Haiti came to about

$853 million while its imports from Haiti totaled approxi-

mately $42 million.

20

Irregular Trade

Most of this bilateral trade (85 percent) moves overland,

and much of it is never ocially registered, making it

hard to gauge the true dimensions of the Haiti/DR trade

imbalance. ese unregistered imports include goods that

are under-invoiced at the border and those that are simply

unreported to Haitian authorities. A 2016 study estimated

that about $259 million in merchandise is registered at

Dominican, but not Haitian, customs and another $375

million is not registered in either country, though the

authors recognized that the “exact values of informal

trade are extremely dicult” to determine.

21

is implies

that Haitian authorities do not collect taxes on some $634

million in goods, many of which compete with domesti-

cally-made products.

22

Like many less-developed countries, Haiti depends on

customs to fund government expenditures: about one third

of total revenues come from taris and other fees collected

at ports and land border crossings. Estimates of the Haitian

government’s annual revenue losses from uncollected taxes

or fees at the border range from $184 million to $440 mil-

lion.

23

Former Haitian finance minister Daniel Dorsainvil

Unregulated trade further undermines

Haitian enterprises that are already

struggling to survive amid widespread

poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and

political uncertainty.

7

designed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development—should reduce the degree of discretion given

to customs ocers, which makes them vulnerable to temp-

tation and intimidation. Document-scanning plus online

value declarations and electronic payments should also re-

duce clearance times, making it less convenient to circum-

vent customs procedures and easier to share information

within the Haitian MEF and with Dominican agencies

41

e government also loses revenues through legal loopholes.

Tax expenditures—including customs and sales tax exemp-

tions—not only drain the treasury of revenues but also

undermine competition. A 2015 World Bank study found

that powerful, family-based economic groups benefited

disproportionately from fiscal and customs duties incentives,

paying duties that were 13 percent lower on average than

those paid by other companies in the same sector.

42

e MEF is starting to take steps to monitor and control these

benefits. e ministry website lists the amount of customs

and tax exemptions in each economic sector for the past five

years, though it does not publish a complete list of the com-

panies receiving preferential treatment.

43

In December 2018,

the MEF announced that it would eliminate customs waivers

granted to public institutions and reduce those given to NGOs.

e finance minister has also expressed support for an inde-

pendent commission to monitor tax incentives to make sure

they are generating job-creating investments as required.

44

A better-regulated border would also provide the Dominican

Republic with much-needed financial resources. Like Haiti,

the DR has cut capital spending as it struggles to increase gov-

ernment revenues and decrease the deficit. e country’s tax

ratio (revenues as a percentage of GDP) averages 13 percent,

well below the average regional ratio (25 percent) and slightly

below that of Haiti (14 percent). Like Haiti, the DR loses sub-

stantial revenues through exemptions and other legal loop-

holes.

45

Evasion is also major reason for low tax collections:

DR authorities estimate they lose 61 percent of potential

income tax collection and about 35 percent of the value-added

tax (VAT).

46

Significant evasion occurs at the border, where

merchants overstate exports to qualify for VAT rebates.

47

e border markets provide an easy, if inecient, way

to evade duties. Haitian importers hire individuals to

go back and forth across the borders, bringing large

e Haitian government did not publish its reasons for

selecting the products included in the ban, leading some

to suspect that its real intent was to favor certain produc-

ers and/or private port owners.

33

While the ban decreased

ocial exports from the DR, its impact on products brought

over the border informally is less clear. Many of the food

and consumer goods listed continued to be sold openly at

border markets, such as the one at Dajabón.

34

Like the poultry ban, the unilateral measure provoked

outrage in the Dominican Republic, which accused Haiti

of violating both bilateral and international commercial

accords.

35

According to the Dominican government, the

ban has cost DR exporters about $300 million.

36

Dominican

companies that produce construction materials have been

especially hard-hit. Gerdau-Metladom, a Brazilian-Do-

minican firm that manufactures rebar, sent nearly half of

its production to Haiti before the ban. Exports across the

border fell to 17 percent of the firm’s production in 2016

and to less than 3 percent in 2018.

Before the ban, the company shipped rebar overland to

Haitian builders, which meant it could oer smaller amounts

on a just-in-time basis. Post-ban, it cannot compete with big

producers from countries like China and Turkey able to hire

entire container ships. “We’ve been the victims of dumping,”

the company’s commercial director said. “We believe in fair

trade practices and following procedures 100 percent.” He

pointed out that rebar should be easy to monitor and tax, as

it is shipped on flatbed trucks: “You can count the coils.”

37

Dominican producers argue the ban has helped, rather

than hindered, informal commerce. e ban is “damaging

Dominican production and the Haitian government is not

increasing its revenues,” said the head of the Dominican

Steel Association. “What has happened is that informality

has exploded.”

38

Lost Revenues

e ban on overland commerce reflects Haiti’s desperation

to increase revenues as foreign assistance declines. External

grants increased after the 2010 earthquake but fell sharply

afterwards. Concessional loans—such as the PetroCari-

be funds oered by Venezuela—have also dried up. With

foreign help, the government managed in recent years to

reduce the government deficit (from 7.1 percent of GDP in

2014 to 3.5 percent in 2015) and to slowly increase tax col-

lection (from about 11 percent of GDP during 2008–2009

to 14 percent in 2015–2016).

39

But the decline in foreign

assistance has undermined the government’s ability to

make the investments in infrastructure and human capital

needed to raise output and productivity. Between 2012 and

2016, capital expenditure fell by 50 percent.

40

Haiti’s implementation of the Automated System for Cus-

toms Data (ASYCUDA)—a computerized customs system

Both governments recognize the need

to regularize their mutual border. Over

the past 20 years, they have signed a

series of agreements to designate oicial

border crossings, establish procedures

and hours of operation, encourage legal

commerce, and fight contraband.

8

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

control,” said a high-ranking diplomat.

55

Some Haitians felt

equally frustrated, attributing the cancellation to their gov-

ernment’s suspicion of its economically powerful neighbor.

“e problem is that border development will continue,

with or without our participation,” said a Haitian ocial.

“But the Dominicans will be the main operators, which is

exactly what we don’t want.”

56

Mutual Corruption

e two governments’ failure to work together against

corruption along the border not only undermines legit-

imate trade but also trust in government. Both Haitians

and Dominicans perceive border ocials as dishonest: “If

you work at the border, you will inevitably be corrupted,”

said an ocial with a Dominican business association.

57

“Honest people are ostracized,” said an economist who has

worked in the Haitian public sector. “Besides, dishonesty

is hard to resist when you are struggling to pay school fees

and see colleagues building houses or buying cars.”

58

In Haiti, border enforcement varies widely depending on

the port of entry and even the ocial involved, according

to businesspeople and consultants. Instead of selectively

inspecting shipments based on an assessment of relative

risk, customs ocials try to inspect all cargo, though they

rely on the importers’ own declarations of value and quan-

tity. Limits on imports for personal use are routinely flout-

ed, and discrepancies in paperwork ignored. “ere are no

procedures, no control,” said an international consultant.

59

Such disorganization means that decisions are left to the

discretion of individual customs ocials, which provides

ample opportunities for petty corruption.

Disorganization at the border also allows corruption on a

grander scale. Most contraband enters Haiti through ocial

crossings by the truckload, according to a variety of sourc-

es, often with the complicity of elected Haitian ocials.

“We’re not talking about goods crossing the border via mo-

torbikes,” said a Haitian industrialist. “We’re talking about

large trucks traveling with armed guards.”

60

“Everybody

knows that senators and deputies have the power to put

their own people in customs,” said a manufacturer who im-

ports raw materials. “ey send their ocial cars to make

sure it gets through customs. I’ve seen it happen.”

61

Even some government ocials recognize the customs

agency needs to be purged and insulated from political

influence. “Customs directors are not chosen for their tech-

nical or professional expertise,” said a high-level ocial.

shipments into Haiti piecemeal under exemptions for

personal use. Better infrastructure, clear rules, and

streamlined customs procedures would make such fraud

uneconomical. Said a regional trade association ocial,

“It should be more ecient simply to pay duties rather

than to pay 50 people to empty a warehouse.”

48

Both governments recognize the need to regularize their

mutual border. Over the past 20 years, they have signed a

series of agreements to designate ocial border crossings,

establish procedures and hours of operation, encourage

legal commerce, and fight contraband.

49

Cooperation

agreements signed in 2014 by the Haitian and Dominican

customs directors enumerate specific actions to facilitate

bilateral cooperation, including language training (in

Spanish, French, and Creole) and the establishment of a

binational council to promote dialogue, fight contraband,

and identify obstacles to legal commercial exchange.

50

e

two countries have also explored measures such as co-lo-

cating customs and migration ocials.

Both governments recognize the need to regularize

their mutual border. Over the past 20 years, they have

signed a series of agreements to designate ocial border

crossings, establish procedures and hours of operation,

encourage legal commerce, and fight contraband

e agreements also include the digital exchange of

information between the two countries, essential to en-

suring that goods cross the border legally and eciently.

Haitian capacity to share information should be en-

hanced by the completion of a $10 million USAID project

to provide the government with the computers, techni-

cal support, and training to manage public revenues and

expenditures. e World Bank plans to provide another

$15 million to help Haiti manage public finances.

51

Under an initiative sponsored by the U.S. government,

ocials from both countries traveled to Laredo, Texas,

in December 2016 to witness U.S.-Mexican cooperation

along the world’s busiest border. Ocials from both

countries discussed not only mutual eorts to reinforce

customs and migration controls, but also initiatives for

border development, such as creating a regional energy

network, tourism promotion, and an investment fund.

52

Haitian and Dominican ocials worked together to

prepare an agreement between the two heads of state,

which was scheduled to be signed in Port-au-Prince by

both foreign ministers in September 2017.

53

But Haitian president Jovenel Moïse’s government abruptly

canceled the event, citing security concerns amid violent

protests over recent tax hikes.

54

Dominican ocials felt

blindsided, suggesting that “economic interests” within

Haiti prevented the government from resolving potentially

explosive problems along their mutual border. “Someday,

commercial problems are going to become social prob-

lems, which neither Haiti nor the Dominican Republic can

Customs officers face not only

political pressure but also the threat of

physical violence.

9

“ey are chosen based on political criteria. And in politics

you have to give something back.”

62

Customs ocers face not only political pressure but also the

threat of physical violence. e Malpasse crossing in south-

ern Haiti was the scene of confrontations that left six people

dead in November 2018. e violence reportedly began when

a Haitian customs agent shot a suspected smuggler, enraging

local traders who set fire to the customs oce, killing those

inside and destroying more than $80,000 worth of comput-

ers and communications equipment.

Haiti’s newly minted border police, known as Polifront,

could not arrive in time to help the small local police force:

rocks and burning tires blocked the one road to Malpasse.

“is should not have happened,” said Polifront Command-

er Marc Justin. “Customs does not have the training to use

weapons. An adequate police presence would have stopped

the violence from even starting.”

63

e United States and the UN are training and vetting Po-

lifront, which had a total force of 350 at the end of 2018.

64

Even this small force is operating on a shoestring, accord-

ing to Commander Justin. It needs more all-terrain vehicles

to reach informal crossing points and boats to monitor

both the coastline and the large saline lake—known as

Étang Saumâtre or Lake Azuéi—that straddles the border

at Malpasse.

65

Small boats piled high with boxes and crates

shuttle across the lake in full view of border ocials unable

to stop or inspect them.

Polifront is dwarfed by the size of security forces on the

other side of the border. e Dominican Republic has

deployed 1,000 members of its Specialized Land Border

Security Corps (CESFRONT) along the border, plus about

13,500 regular troops.

66

ese troops are charged with

stopping the irregular movement of people and contra-

band goods across the border. Among the goods confiscat-

ed in large quantities along the Haitian border are contra-

band cigarettes and Chinese garlic, which costs a fraction

of the DR-grown product.

67

(ere appears to be little drug

tracking along the Haiti/DR border; the Dominican Re-

public is an important transit country for South American

cocaine destined for North America or Europe, but most

arrives and leaves via fast boat or commercial container

without passing through Haiti.

68

)

But the military’s most important mission at the border

is preventing Haitians from entering the DR illegally.

According to the Dominican migration service, authori-

ties expelled about 132,000 Haitians in 2018, including

75,000 turned back at the border and 57,000 deport-

ed from inside the country.

69

Although Haitians have

worked in the Dominican sugar and other industries for

more than a century, the DR government has periodi-

cally—sometimes brutally—cracked down on migrants.

Expulsions picked up after a 2013 Constitutional Court

decision armed laws that retroactively deny citizenship

to Haitians without at least one Dominican parent, in-

cluding those who have lived in the DR for generations.

70

Haitian ocials complain that Dominican authorities

transport deportees to the border without prior notice,

making it impossible for the Haitian government to pre-

pare for their repatriation.

71

Nonetheless, Haitians continue to cross the border for

work, though at the mercy of Dominican military of-

ficials who determine who stays or goes. Laborers pay

bribes to work; traders endure shakedowns to buy or sell

goods. ose traveling beyond the border may contract

experienced Dominicans to handle the “tolls” paid to sol-

diers at each checkpoint.

72

“Dominican military person-

nel on the border play a major role, and collect substan-

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

GDP per Capita (current USD)

Latin America & Caribbean

Dominican Republic

Sub-Saharan Africa

Haiti

Source: World Bank Open Data.

10

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

countries as significant manifestations of corruption

throughout the public and private sectors.

80

Businesses associations in both countries should actively

promote public-private anti-corruption initiatives while

adopting internal anti-corruption compliance practices,

such as Transparency International’s Integrity Toolkit.

81

e

Haitian Manufacturers’ Association (ADIH) and the Domin-

ican Republic Industries Association (AIRD), for example,

should work with local chambers of commerce to establish

confidential mechanisms to report corrupt practices along

the border, such as providing confidential email addresses

or telephone lines, and then cooperate with authorities to

investigate fraud and abuse.

Both countries could benefit from regional expertise and

assistance. While corruption remains a scourge in much of

Latin America and the Caribbean, some countries, such as

Chile and Uruguay, stand out for innovative and eective

measures to promote good governance and transparency.

Others, such as Colombia, can share lessons learned as they

struggle to overcome decades of corruption and insecurity.

Bilateral donors and multilateral institutions should use

already-engaged entities to promote regional coopera-

tion to evaluate anti-corruption eorts and promote best

practices.

82

In Central America – where governments face

both violent criminal gangs and entrenched corruption

– Guatemala and Honduras have enlisted multilateral in-

stitutions to help them investigate and prosecute complex

cases involving high-level political figures and powerful

criminal groups.

83

Cross-Border Challenges,

Joint Opportunities

Corruption is not the only problem both countries have in

common. Although the Dominican Republic has achieved

upper-middle-income status over the past 50 years, much

of the population remains relatively poor. About 30 per-

cent—50 percent in rural areas—live below the national

poverty line.

84

Poverty is especially pervasive in the DR’s borderlands.

ree of the country’s five poorest provinces lie along the

border: Elías Piña (83 percent poor), Pedernales (75 per-

cent), and El Seibo (71 percent).

85

Like Haiti’s borderlands,

the Dominican side lacks paved roads, schools, potable

water, and good jobs. e DR also faces deforestation

along the border: the province of Dajabón had the highest

rate of tree cover loss in the country with a 19 percent

decline between 2001 and 2017.

86

Poverty and neglect in the Haitian and Dominican hinter-

lands make cross-border trade especially important. De-

spite cultural and linguistic dierences, most exchanges

between Dominican and Haitian merchants at the border

tial income, in admitting undocumented Haitians into

the country for a fee,” according to a 2010 study based

on fieldwork along the border.

73

Or as a Haitian business-

man involved in cross-border trade put it: “For a Domin-

ican soldier, being assigned to the border is like winning

the lottery.”

74

Corruption is the one of the most contentious political

issues in both countries, and indeed throughout the

region. Both governments are navigating mega scan-

dals: Dominican ocials reportedly took more than $92

million in bribes from Odebrecht, a Brazilian engineering

company; Haitian ocials allegedly misused close to $2

billion in funds provided under PetroCaribe, a preferen-

tial payment program oered by Venezuela.

75

Both Santo Domingo and Port-au-Prince have weathered

massive anti-corruption protests. While mostly peaceful

in the DR, demonstrations in Haiti – over grievances rang-

ing from higher gas and food prices to government graft

and impunity – have turned violent. In 2018 protestors

blocked streets and battled police during July, October,

and November.

76

In February 2019, the protests erupted

again, shutting down businesses, schools, and govern-

ment oces for more than a week while cutting o access

to food and health care. In addition to calling for an inde-

pendent investigation into the misappropriation of Petro-

Caribe funds, protestors have demanded the resignation

of both the Haitian president and the prime minister.

77

In response Prime Minister Jean Henry Céant announced

a series of emergency measures February 16, including

budget cuts and an end to ocial privileges, measures

to revive the economy and raise wages plus additional

eorts to combat corruption and prevent smuggling. He

also promised more resources to enable the judiciary to

complete the investigation and pursue the prosecution

of those implicated in the PetroCaribe scandal.

78

e Odebrecht and PetroCaribe scandals are only the

most visible manifestation of corruption: citizens across

the island view fraud as pervasive. Haiti and the

Dominican Republic score badly on Transparency In-

ternational’s Corruption Perception Index, which ranks

countries based on expert assessments and surveys.

Of the 32 countries surveyed in the Americas, Haiti is

ranked second worst, above only Venezuela; the Domini-

can Republic is among the bottom ten.

79

Corruption is a two-way street: for every dishonest

ocial, there is a citizen or company paying for special

treatment. e public and private sectors of both Haiti

and the DR should focus greater attention on compliance

with the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption

and the United Nations Convention against Corruption

(UNCAC) and on developing comprehensive national

plans of action (and where appropriate, a binational

plan) to begin to address what is recognized in both

11

local technological institute and regional university. e

goal is to assist local producers in building value chains for

dairy products, fruits and vegetables, and honey produc-

tion.

91

Promoting agriculture is especially important in Haiti,

where the sector employs about 40 percent of the labor

force. Haitian farmers struggle to increase productivity and

compete against imports from the DR and the United States

in a sector that lacks adequate infrastructure, research and

extension services, and access to credit.

92

e EU/UNDP program provided training for both merchants

and government ocials on labor and human rights, includ-

ing the rights of migrants and returnees. It also organized

the region’s first binational sports festival for boys and girls

from both countries.

93

e program supported local human

rights NGOs in both countries, oering workshops for Do-

minican security forces and Haitian police on migrant rights,

organizing eorts to assist repatriated migrants in Haiti,

and conducting information campaigns in both countries to

prevent domestic violence and labor exploitation.

94

USAID’s Local Works, a five-year program that began in

2018, is another eort to improve livelihoods along the

border by working with civil society organizations to iden-

tify community needs, share their findings with donors,

are friendly. e border markets are generally peace-

ful, despite apparent chaos. “Buyers and sellers interact

cordially, courteously, and even jokingly with each other

in all three markets observed,” according to a 2010 Pan

American Development Fund (PADF) study.

87

Merchants

from both countries protested the Haitian government’s

ban on the cross-border sale of 23 products, warning that

it would encourage corruption and lead to shortages of

food and other essential items.

88

e location of border markets within the Dominican

Republic renders Haitian traders vulnerable to abuse

on both sides of the border. Dominican municipalities

set the rules governing market access and collect rental

payments and other fees from vendors. Haitian vendors

are sometimes forced to pay more for market access than

their Dominican counterparts or risk confiscation of

their merchandise.

89

Constructing border markets within Haiti would protect

Haitian merchants while also providing Haitian munic-

ipalities with local revenues. at may finally happen in

Ouanaminthe. A project funded by the European Union

and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

financed both the renovation and expansion of market

facilities in Dajabón and a new market on the other side of

the Massacre River. e enlarged market in Dajabón opened

in 2017; the one in Haiti still consisted only of steel girders

in December 2018, nearly two years behind schedule. It is

scheduled to open in 2019.

e EU/UNDP program, which ended in December 2016,

also laid the groundwork for greater local cross-border

cooperation on development, especially in the northern

corridor. Municipal ocials in both Dajabón and Ouana-

minthe received training in administration, planning, and

small business development. e program strengthened

Dajabón’s local development agency and created a parallel

oce in Ouanaminthe. Ocials from both cities visited El

Salvador to observe binational markets along its borders

with Honduras and Nicaragua.

90

Some projects carried out in the DR could be replicated in

or extended to Haiti, including creating a center for food

quality (complete with laboratory) in partnership with a

The largest employer in northeastern

Haiti, CODEVI provides steady jobs to

10,500 Haitians, an on-site day-care

center, plus education and health bene-

fits. Manufacturers get preferential access

to the U.S. market under legislation that

eliminates or reduces duties on Haitian

apparel exports.

“Haiti Lake”: Goods being smuggled across the D.R.-Haiti border

via Lake Azuei . Photo: Mark Schneider

12

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

and execute initiatives. It will also encourage public-pri-

vate initiatives, such as partnerships between companies

and vocational institutions. Although Local Works so far

operates only in the Dominican Republic, its goals include

building bridges across border communities divided by

language and culture.

95

Among the most important public-private initiatives in

the northern corridor is the local free zone: CODEVI, an

industrial park founded in 2003 by a Dominican textile

company with financing from the World Bank. e park,

located in Ouanaminthe, has attracted investment from

the United States, China, Sweden, and Sri Lanka, among

others.

96

As the largest employer in northeastern Haiti,

CODEVI provides steady jobs to 10,500 Haitians, an on-

site day-care center, plus education and health benefits.

Manufacturers get preferential access to the U.S. market

under legislation that eliminates or reduces duties on

Haitian apparel exports.

97

e Quisqueya Binational Economic Council—a joint

eort by Dominican and Haitian entrepreneurs to pro-

mote economic development along the border—argues

that industrial parks could generate hundreds of thou-

sands of jobs along the border

by attracting investors looking

for near-sourcing opportunities

in the Caribbean. e American

Chamber of Commerce in the Do-

minican Republic also promotes

near-sourcing and co-production

to increase the competitiveness

of U.S. firms while enhancing

stability and prosperity in both

countries.

98

It could also re-

duce friction over the two most

contentious bilateral issues:

migration and trade. e only

wall needed on the border, says

Fernando Capellan, president of

CODEVI, is a “wall of jobs.”

99

e Mixed Bilateral Domini-

can-Haitian Commission—created

in 1996 by then-Presidents Joa-

quín Balaguer of the DR and René

Préval of Haiti—should provide a

platform for cooperation between

ocials in both countries. e two

foreign ministers agreed in 2017 to

reactivate the commission so that

the two governments could work

together on bilateral concerns

such as migration, trade, energy,

and deforestation. Little has been

accomplished, however. “We have

reached 84 agreements,” said a

Dominican diplomat. “Not one has been implemented.”

100

e foreign ministries of both countries understand the need

for fluid high-level cooperation and have been preparing for

a presidential summit in early 2019.

101

Regularly scheduled

presidential and ministerial meetings should become a feature

of the bilateral relationship. e two countries should also

establish a timetable, with benchmarks, for the implementa-

tion of already-signed protocols for cooperation between the

two custom agencies. Donors should continue helping both

agencies increase their technical and administrative capacities

to make revenue collection more ecient and transparent.

Conclusion

Mutual fears and prejudices, fueled by a history of war,

occupation, and exploitation, have long divided the two

nations sharing the island of Hispaniola. But Haiti and

the Dominican Republic also have common interests in

promoting growth and combatting fraud, especially along

their porous, chaotic border. Crude attempts to curtail

cross-border trade have simply driven commerce under-

ground, fueling corruption in the process. Formal trade

Dajabón

Hato Viejo

Comenda

Cánada Miguel

El Cacique

Malpasse (Jimaní)

Pedernales

Hondo Valle

El Corozo

Restauración

Tilory

Guayajayuco

Bánica

Los Cacaos

Bi-National Markets along the

Haiti-Dominican Republic Border

Source: Mariela Mejía, “Mercados fronterizos: comercio entre el caos,” Diario Libre

13

EXAMPLES from other Latin American countries

provide lessons for Haiti and the Dominican

Republic on how to prevent conflict, enhance

security, and promote cross-border cooperation.

In 1995, Peru and Ecuador fought a 19-day war over about

50 miles of disputed border along the Cenepa River in the

upper Amazon basin. e conflict was brief but bloody,

involving thousands of troops, fighter jets, helicopters,

anti-aircraft artillery, and land mines.

1

Hundreds—perhaps

more than a thousand—died in a jungle war that cost both

sides up to $1 billion in damages.

2

e fighting triggered in-

tense hemispheric diplomacy led by the four countries (the

United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile) that had served

as guarantors of the 1942 Rio Protocol, which settled a pre-

vious border dispute. Peace accords signed after three years

of negotiation fixed the boundary per the 1942 protocol but

guaranteed Ecuador access to the Amazon river. Diplomats

sweetened the deal with incentives aimed at preventing fu-

ture conflicts: agreements designed to encourage trade and

development in the border region, backed by promises of $3

billion in aid from donors, international financial institu-

tions, and the private sector.

3

Among the most important outcomes of the 1998 peace

accords are:

• e creation of a binational border development plan and

fund to build infrastructure, facilitate investment, and pro-

mote cultural exchanges among communities on both sides

of the border.

4

• Regular presidential and joint cabinet meetings to discuss

bilateral issues and assess progress along the border.

5

• Expansion of bilateral trade, which rose from about $100 mil-

lion in 1996 to $3 billion in 2014, and better infrastructure and

services for communities within the border region, including

new or improved roads, access to sanitation services and elec-

tricity, hundreds of new schools, and dozens of health clinics.

6

1 William R. Long, “Peru, Ecuador Battle on Small but Deadly Scale: Latin America: As peace talks hit snag, platoon-size units continue war in

Amazon rain forest.,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1995, http://articles.latimes.com/1995-02-08/news/mn-29584_1_talks-hit-snag.

2 Beth A. Simmons, “Territorial Disputes and Their Resolution: The Case of Ecuador and Peru,” Peaceworks No. 27, United States Institute of

Peace, April 1999, 12.

3 “Peru and Ecuador Sign Treaty to End Longstanding Conflict, New York Times, October 27, 1998, https://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/27/world/

peru-and-ecuador-sign-treaty-to-end-longstanding-conflict.html.

4 See the Peruvian chapter’s website at https://planbinacional.org.pe.

5 “Presidentes Vizcarra y Moreno encabezan XII Gabinete Binacional Perú-Ecuador,” Andina, October 26, 2018, https://andina.pe/agencia/noti-

cia-presidentes-vizcarra-y-moreno-encabezan-xii-gabinete-binacional-peruecuador-729799.aspx.

6 Marcel Fortuna Biato, “The Ecuador-Peru Peace Process,” Contexto Internacional 38, no. 2 (May/August 2016), 629, 632.

7 U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Relations with Mexico: Fact Sheet,” Bureau of Western Hemisphere Aairs, April 1, 2018, https://www.state.

gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35749.htm.

8 Congressional Research Service, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues and Implications, RL32934 (2018), 10-11, https://fas.org/sgp/

crs/row/RL32934.pdf.

9 “Mexico, U.S. Sign Accords on Customs, Border Cooperation,” Reuters, March 26, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-mexico-co-

operation/mexico-u-s-sign-accords-on-customs-border-cooperation-idUSKBN1H300H; “CBP, Mexican Counterparts Sign Agreements for

Better Cooperation,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, March 30, 2018, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/spotlights/cbp-mexican-counter-

parts-sign-agreements-better-cooperation.

10 See the “Charter,” NADB, http://www.nadb.org/pdfs/publications/Charter_Eng.pdf.

11 For more on these and other projects, see www.nadb.org.

e U.S.-Mexico border is among the busiest in the world,

with about $1.7 billion worth of two-way trade and hun-

dreds of thousands of legal border crossings every day.

7

Giv-

en the importance of these exchanges, the two governments

have developed multiple cooperation mechanisms, ranging

from forums for cabinet-level discussion—including the

High-Level Economic Dialogue to promote competitiveness

and job creation and the High-Level Regulatory Cooperation

Council to oversee safety and health standards—to customs

and migration procedures carried out jointly by Mexican

and U.S. ocials at the border itself.

8

Both governments

continue to upgrade their cooperation: in March 2018,

they signed agreements to expedite trade, ensure customs

compliance, and combat illicit activities. Measures included

joint inspections at more border crossings to reduce costs

and wait times, and information-sharing to ensure the qual-

ity and safety of agricultural produce.

9

In addition, the United States and Mexico jointly fund envi-

ronmental projects on both sides of the Rio Grande. When

the two countries signed the North American Free Trade

Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, they also created the North

American Development Bank (NADB) with an initial $3

billion in capital provided by both governments.

10

e bank

funds energy, sanitation, water, and air quality projects for

communities within an area extending 100 km north of the

border and 300 km south.

Among its recent projects are:

• Loans to purchase new buses—fueled by low-emission diesel

or compressed natural gas—to improve public transportation

and enhance air quality in northern Mexico.

• Grants for water and wastewater projects to benefit commu-

nities in Texas and New Mexico.

• Financing of a public-private partnership to build a desali-

nation plant in Baja California.

11

14

— cross-border trade and corruption along the haiti-dominican republic border

governed by clear, enforceable rules could generate eco-

nomic growth while curtailing the power of the corrupt

interests that thrive on illegal commerce.

Haiti desperately needs the tax revenues it is losing to

powerful economic and political interests at the border.

By strengthening customs collection, the government

would also demonstrate that it is genuinely committed

to eradicating corruption at every level of government,

including Parliament. Donors are growing impatient with

government inaction on corruption and rule of law is-

sues: the U.S. Congress in February in approving FY2019

foreign assistance directed the State Department to work

with Haiti and the DR to develop plans to strengthen

border security, enhance customs operations, and mini-

mize corruption.

102

Neighboring countries with cultural and economic dier-

ences as stark as those separating Haiti and the Domin-

ican Republic have managed to put aside their conten-

tious, sometimes violent, common histories to promote

trade along their common borders.

103

Bridging the economic chasm that separates Haiti and the

Dominican Republic will not be easy or quick. But the two

countries—like those in the examples above—can take steps

to overcome mistrust, combat corruption, and promote bor-

derland development. Separation is not an option. e two

economies are already profoundly integrated, though many

of the exchanges now taking place are informal or illegal.

Both governments have the means to make customs more

ecient and importing contraband more dicult. With

international help, they can also work together to combat

corruption and to provide impoverished border communi-

ties with better jobs, infrastructure, and services.

Methodology

e Americas Program at CSIS conducted research

for this report over approximately three months. e

four-member team used a variety of sources, including

journal articles, government documents, meetings with

experts in Washington, D.C., and interviews with stake-

holders in Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

e team initiated its research in Washington, D.C.,

meeting with experts from the U.S. government, multilat-

eral institutions, the private sector, and academia. ese

interviews provided background information on social,

economic, and political conditions in Haiti and the Do-

minican Republic and on foreign assistance from USAID

and multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, the

IMF, and the Inter-American Development Bank.

In November 2018, members of the CSIS team traveled

to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where they conducted more

than two dozen interviews with business people, U.S.

and U.N. diplomats, the Haitian government, and civil

society researchers and activists. Members of the team

also travelled to the border crossing at Malpasse to inter-

view customs agents and border security ocials.

In December 2018, members of the CSIS team traveled

to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where they held

more than a dozen meetings with government ocials,

business leaders, and diplomats. Members of the team

also travelled to the Dajabón/Ouanaminthe border cross-

ing to observe the market, the CODEVI industrial park,

and to speak with local business and government repre-

sentatives.

CSIS would like to thank the following institutions for

their help:

U.S. Government

• Department of State

– USAID

– Embassy to Haiti

– Embassy to the Dominican Republic

• U.S. Congress

Haitian Government Institutions

• Oce of the President

• Prime Minister

• Foreign Relations Ministry

– Embassy of Haiti to the US

– Permanent Mission to the Organization of American

States

• Bank of the Republic

• Finance Ministry

• General Directorate of Taxes

• General Customs Administration

• Border Police (Police Frontalière - POLIFRONT)

• Counter Narcotics Police (Brigade de Lutte contre le

Trafic de Stupéfiants -BLTS)

Dominican Government Institutions

• Foreign Relations Ministry

• Treasury Ministry

• Central Bank

• General Directorate of Internal Taxes

• General Directorate of Customs

• National Competitiveness Council

• Municipality of Dajabón

• Embassy of the Dominican Republic to the U.S.

Multilateral Institutions

• European Union Delegation to the Dominican Republic

• International Monetary Fund

• Inter-American Development Bank

15

• Organization of American States

• United Nations, Department of Political and Peace-

building Aairs

• United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti

(MINUJUSTH)

• World Bank

Private Enterprise Groups

• American Chamber of Commerce, Port-au-Prince

• American Chamber of Commerce, Santo Domingo

• Caribbean Export Development Agency, Santo Domingo

• CODEVI and Grupo M, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

• Dominican Industries Association (Asociación de

Industrias de la República Dominicana (AIRD), Santo

Domingo

• Haitian Manufacturers Association (Association des

Industries d’Haïti -ADIH), Port-au-Prince

• Retailers Asociation (Asociación de Comerciantes De-

tallistas), Dajabón, Dominican Republic