COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

Investment opportunities and growth pathways to

higher value addition, resilience, and inclusion

CREATING MARKETS IN

THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

October 2023

About IFC

IFC — a member of the World Bank Group — is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging

markets. We work in more than 100 countries, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in developing

countries. In fiscal year 2022, IFC committed a record $32.8 billion to private companies and financial institutions in developing countries,

leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity as economies grapple with the impacts of

global compounding crises. For more information, visit www.ifc.org.

For more information, visit www.ifc.org.

© International Finance Corporation 2023. All rights reserved.

2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20433

www.ifc.org

The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of

applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions

or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation,

typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and

conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International

Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent.

Cover Photos: Shutterstock/Wirestock Creators, metamorworks, GreenOak, Kitreel, and antoniodiaz.

iii

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IV

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS V

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VII

A Roadmap for the Short to Medium Term x

Key Private Sector Investment Opportunities to Grow Markets in a Sustainable Economy xiv

COUNTRY CONTEXT

1.1 Macroeconomic Fundamentals: Strong Growth but Shrinking Fiscal Space and

Lagging Inclusion 1

1.2 Disaster and Climate Change Risks Present an Increasingly Critical Challenge 5

1.3 The Role of the Private Sector in Pivoting toward a More Inclusive and Resilient Economy 8

. PRIVATE SECTOR CONTEXT

2.1 Most SMEs Are Characterized by Low Productivity, High Informality, and Low-Quality Jobs 11

2.2 FDI Is Concentrated in Tourism and Real Estate and Has Not Suciently

Contributed to GVC Integration 12

2.3 Exports Mirror the Concentration in FDI and Reveal a Strong Duality in the Dominican

Economy 17

2.4 The Reconfiguration of Global Value Chains (Nearshoring) Is a Window of

Opportunity for the DR 22

. KEY CHALLENGES TO PRIVATE SECTOR GROWTH

3.1 Regulatory Complexity and Institutional Fragmentation, Leading to an Opaque Business

Environment 28

3.2. The Skills Gap and Low-Quality Education 35

3.3. Energy and Electricity 41

. KEY PRIVATE SECTOR INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES TO GROW MARKETS

4.1 Medical Devices 48

4.2 Industrial Real Estate and Eco-industrial Parks 70

4.3 Agri-logistics 95

APPENDIX

Appendix A: History of Special Fiscal Regimes in the Dominican Republic 123

Appendix B: Mapping of Investment Incentives in the Dominican Republic and Comparator

Countries 125

Appendix C: Government Measures to Support the Private Sector amid the COVID-19 Pandemic 128

NOTE

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Dominican Republic Country Private Sector Diagnostic was prepared by a joint

team from the World Bank Group led by Jade Salhab (Senior Private Sector Specialist,

IBRD) and Juan Pablo Celis Gomez (Economist, IFC). The core team included David

Corcino Paulino (Private Sector Specialist, IBRD) and Diana Hristova (Consultant,

IBRD). Substantive contributions were provided by Nadia Rocha (Lead Economist,

IBRD), Fausto Patino (Economist, IBRD), Sylvia Solf (Lead Economist, IBRD),

Yago Aranda Larrey (Private Sector Specialist, IBRD), Christina Wiederer (Senior

Economist, IBRD), Tulio Marti (Consultant, IBRD), and Luis Aldo Sánchez Ortega

(Consultant, IBRD), Alvaro Espitia (Consultant, IBRD) and Mike Nyawo (Consultant,

IBRD), Luiz Almeida (Economist, IFC), Adrian Fossaceca (Economist, IFC), in

addition to valuable suggestions by María Paulina Mogollón (Principal Investment

Ocer, IFC), Carina Fichard (Senior Investment Ocer, IFC), Pedro Rodriguez

(Program Leader, IBRD), Huong Mai Nguyen (Energy Specialist, IBRD), Gabriel

Roberto Zaourak (Senior Economist, IBRD), and Carmen Amaro (Operations Ocer,

IBRD).

The medtech sector assessment was led by Gloria Ferrer and Kieron Swift (The Cluster

Competitiveness Group). The eco-industrial parks sector assessment was led by Etienne

Kechichian (Senior Economist, IBRD) and Carlos Senon Benito (Financial Sector

Specialist, IBRD), with substantive contributions by David Corcino Paulino (Private

Sector Specialist, IBRD), Ignacio Miró (Consultant, IBRD), and Nidal Mahmoud

(Consultant, IFC), Georey Mersan (Operations Ocer, IFC). Finally, the agri-

logistics sector assessment was led by Alvaro Diaz, Dayana Peñaranda and Ivan Ruiz

(The Cluster Competitiveness Group).

Administrative support was provided by Paula Houser, María Hermann, Alexandra

Soto Ortiz, and Margarita Camposano.

The team is also grateful to government and private sector representatives who

generously shared their time and insights. The team is grateful for the valuable

comments provided by the WBG peer reviewers: Roberto Echandi (Senior Trade

Specialist, IBRD), and Vincent Palmade (Lead Economist, IBRD).

This work was carried out at the request and under the guidance of IFC and World

Bank leadership. The team is grateful for the ongoing support and guidance provided

throughout the preparation of the Country Private Sector Diagnostic by Yira Mascaró,

Tatiana Nenova, Luciana Harrington (Strategy Ocer, IFC), Denis Medvedev, Michel

Kerf, Ronke-Amoni Ogunsulire, Carolina Cardenas, and Alexandria Valerio.

v

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

B2B business-to-business

B2C business-to-consumer

BCRD Central Bank of the Dominican Republic

BPO business process outsourcing

CAGR compound annual growth rate

CDEEE Corporación Dominicana de Empresas Eléctricas Estatales

CEM Country Economic Memorandum

CNE National Energy Council

CNZFE Consejo National de las Zonas Francas (National Council of Free Trade

Zones)

CO2 carbon dioxide

CPSD Country Private Sector Diagnostic

DGA General Directorate of Customs

DR Dominican Republic

DVX indirect value added

EDE Empresas Distribuidoras de Electricidad

EIP eco-industrial park

E&S environmental and social

ESG environmental, social, and governance

EU European Union

FDI foreign direct investments

FVA foreign value added

GDP gross domestic product

GHG greenhouse gas

GTR general tax regime

GVC global value chain

IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

ICT information and communication technology

IDA International Development Association

IDB Inter-American Development Bank

IFC International Finance Corporation

vi

IMF International Monetary Fund

IP industrial park

ITBIS Tax on the Transfer of Industrialised Goods and Services

KPO knowledge process outsourcing

LAC Latin America and the Caribbean

MARENA Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources

MEM Ministry of Energy and Mines

MERCADOM Dominican Wholesale Center for Agricultural Supplies

MESCyT Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology

MFA Multi Fiber Agreement

MH Ministry of Finance

MICM Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and SMEs

MNC multinational corporation

MSME micro, small, and medium enterprise

ND-GAIN Notre Dame-Global Adaptation Initiative

OECD Organisation from Economic Co-operation and Development

PA productive alliances

PPA power purchase agreement = the normal nomenclature

PPD public-private dialogue

PPP public-private partnership

PVRS photovoltaic rooftop systems

R&D research and development

REIT real estate investment trust

SEZ special economic zone

SME small and medium enterprise

STEM science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

TFP total factor productivity

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

VAT value added tax

VUCE Ventanilla Única de Comercio Exterior (Single Window for Foreign

Trade)

WDI World Development Indicators

vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Dominican Republic (DR) has long had a strong private sector, which has

supported two decades of remarkable growth and poverty reduction. The country

is the Caribbean’s largest economy—and the eighth largest in Latin America—with

a population of 11.2 million (2022). The Dominican Republic is endowed with

productive resources that, together with market-oriented reforms and macroeconomic

stability, have positioned the country as an attractive investment destination. Foreign

direct investments (FDI) of about 4 percent of GDP, on average, have over the past 20

years fueled tourism, services, manufacturing, construction, and mining (figure 2.12).

1

Supported by domestic demand and favorable external conditions, the DR’s economy

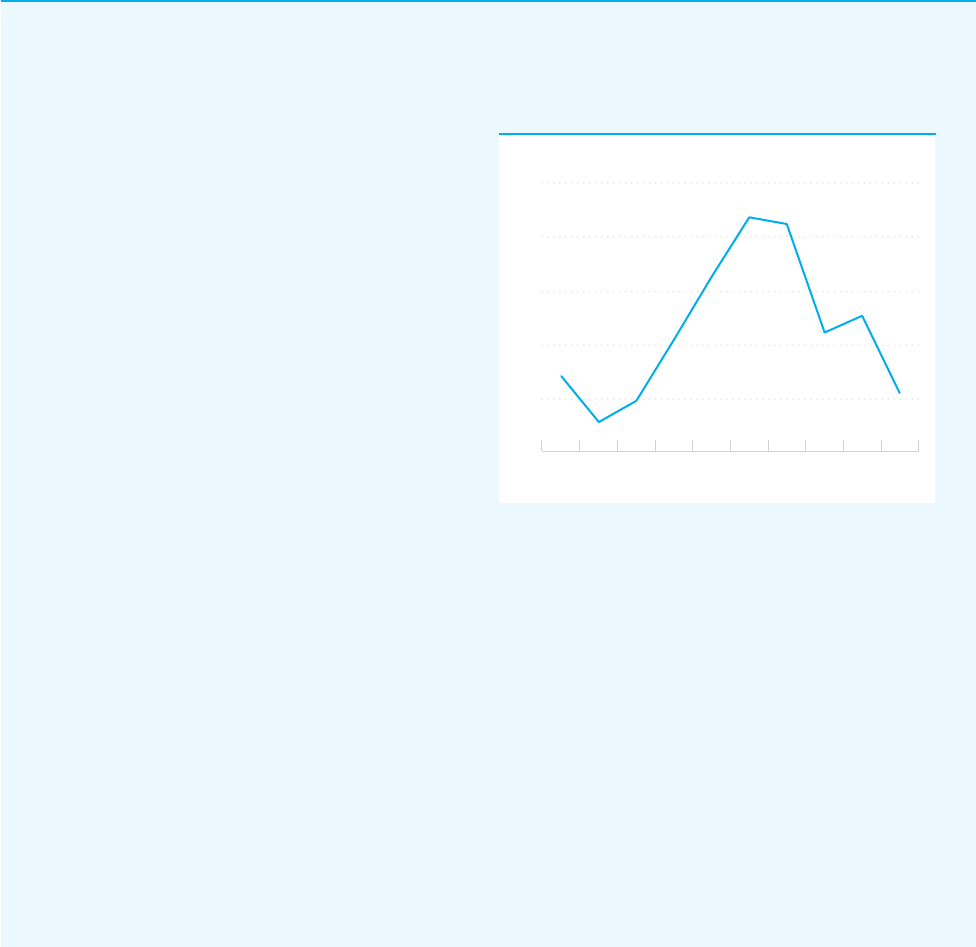

expanded by 5.8 percent, on average, over 2005–19 (Figure 1.1)

2

, driven primarily by

capital accumulation. Private investment reached 24 percent of GDP in 2019, higher

than its regional peers such as Jamaica (21 percent) and Guatemala (12.4 percent), and

gaining on Panama (31 percent)

3

. Substantial growth also led to reductions in poverty

and inequality. The poverty line for the DR, as an upper-middle-income country, is

defined as less than US$6.85 in 2017 purchasing power parity per day. From 2002 to

2004, the DR’s poverty rate increased from 40 percent to 57 percent of the population

because of the economic shock from the banking crisis, but the rate began a steady

decline in 2013 and by 2021 had fallen to 23 percent. The country has also reduced

extreme poverty to less than 1 percent as of 2021.

4

Income inequality has also

improved as reflected by the Gini coecient falling from 0.51 to 0.38 over 2000–21.

5

Despite strong economic growth and progress in social indicators, labor informality

remains high and poverty reduction has been spatially imbalanced. Average poverty

reduction conceals significant gaps: three out of four people moving out of poverty

during 2017–19 lived in urban areas, where poverty rates were lower than in rural

areas. According to the ongoing World Bank Poverty Assessment, poverty in the two

provinces near Haiti is twice as high as in the Santo Domingo metropolitan area

(where economic activity is concentrated) and the tourism centers (Cibao Nordeste

and Yuma). Moreover, as identified by the World Bank Jobs Diagnostic (2021), the

Dominican economy has performed quite well in terms of the number of new jobs

generated over the past two decades. The economy’s performance has been less

successful in generating high-quality jobs.

6

The incidence of informality is high in

general and when compared with other countries. In the Dominican Republic, 57.3

percent of workers were informal in 2021, above structural or regional peers like

Costa Rica (39.3 percent) and Panama (55.7 percent). These workers tend to work in

small firms and have low skills. Informality is often a symptom of low productivity

and low wages, but it is also part of a vicious cycle. High informality could reflect

low benefits associated with paying taxes or social security contributions. At the

same time, high informality reduces the tax base and the viability of social insurance

systems, which can result in a lower quantity and quality of public goods and services.

These eects are particularly important in the Dominican Republic, where fiscal space

is increasingly limited.

viii

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

Public sector debt is sustainable, but downside risks persist and remain elevated. The

Dominican Republic’s fiscal space has been strained by the policy measures deployed

during the pandemic, but preexisting costly fiscal incentives were already eroding

revenues and making public finances vulnerable to shocks. The government launched

a robust fiscal and monetary policy response to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis, which

lessened poverty impacts. The debt of the consolidated public sector grew from 37

percent to 51 percent of GDP over 2010–19 and further to 69 percent by end-2020,

before gradually decreasing in 2021 and 2022, closing at 58.6 percent of GDP in

2022 (figure 1.3)

7

. But the fiscal challenges predate the pandemic. Tax collection is

3.2 percentage points of GDP lower than the average for regional peers (Guatemala,

Jamaica, Panama) and 4.5 percentage points of GDP lower than structural peers

(Costa Rica and Bulgaria), reflecting a narrow base because of tax incentives and

exemptions—more than 4 percent of GDP—coupled with relatively low collection

eciency (figure 1.5)

8

. Although public finances are deemed sustainable, the debt ratio

can be derailed by external shocks.

Climate change looms as a fundamental risk to the DR’s development trajectory,

increasingly threatening the economic contribution of critical sectors, such as tourism

and agriculture. The stability of the growth path is and will continue to be subject to

risks from recurrent natural events that hit Caribbean countries, and that are likely to

increase in frequency and magnitude with climate change. The country scored 46.5

on the 2020 ND-GAIN Index, with 100 being the highest possible score, ranking

101st out of 182 evaluated countries. This score reflects its limited preparedness to

improve resilience against climate-related vulnerabilities. Additionally, the Dominican

Republic is the world’s 12th-most-aected country by natural disasters over 1998–

2017, according to the 2019 Global Climate Risk Index, with hurricanes generating

annual economic losses of 0.5 percent of GDP on average since the early 2000s. In

this context, diversifying the export and FDI portfolio to greener products—as well

as upgrading productive infrastructures, such as industrial parks, to become more

resilient to climate eects—can strengthen the sustainability of the country’s economic

growth and mitigate climate-change-related risks such as to tourism, agriculture, and

manufacturing plants.

Exports and FDI contribute to the DR’s economic performance, but their portfolios

are undiversified and increasingly dependent on tourism and a small number of

goods, exacerbating the exposure to climate change risks. Exports are heavily

concentrated in tourism, agricultural commodities such as cacao and bananas, and

gold, although a burgeoning diversification is notable owing to the recent growth

in higher-value-added manufacturing exports. In fact, tourism accounts for an

impressive 44 percent of total exports (2019).

9

This sectoral concentration is also

manifested in FDI, which is largely resource and eciency-seeking:

10

Tourism

captured 25 percent of FDI inflows in 2022, followed by real estate, with 15 percent

(figure 2.12)

11

. Considering that tourism is particularly exposed to climate change

impacts, adaptation and impact mitigation measures should include not only

diversification within tourism (away from beach tourism) but also diversification of

both FDI and exports beyond tourism. The DR’s participation in global value chains

remains, indeed, among the lowest in the world (figure 2.16), adding on average 30

percent of value added to exports since 2000, a rate below global structural peers

such as Tunisia (57 percent) and Costa Rica (37 percent).

12

ix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Amid a declining share of exports, however, manufacturing activities in special

economic zones (SEZs) are contributing to a surge in higher-value-added products and

diversification, although with an associated fiscal burden. Exports of the Dominican

Republic peaked at about 34 percent of GDP in 2000–04 and have been on a declining

trend since 2004, reaching 24 percent of GDP in 2019 (figure 2.17). The downward

trend has been partially mitigated as of 2013 by the surge of gold exports. On the flip

side, the growth rate of medical device manufacturing (5.1 percent)—all located in

industrial parks benefiting from the SEZ regime—outpaced that of total exports (4.5

percent) in the 2011–20 period. (figure 4.4) Given the SEZ regime’s contributions to

export diversification and value addition, but also the cost of the fiscal expenditure it

represents, recent analyses by the World Bank and the Inter-American Development

Bank have highlighted the need for a robust cost-benefit analysis to help optimize its

scope and impacts.

However, the Dominican economy is characterized by a constraining duality, resulting

from the absence of meaningful backward linkages between the small number of

formal and export-oriented firms operating under the SEZ regime (774 firms) and

the larger group of local firms (5,198 firms) in the manufacturing and related services

sector under the general tax regime (GTR)

13

. This duality manifests in three main

dimensions. First, GTR exports are mostly oriented toward the European market

and rest of the world, whereas SEZ exports are almost entirely directed to the United

States. Second, exports dier in technological content and complexity levels across

regimes. Sixty percent of SEZ exports have some level of technology and involve

some level of sophistication in their production process, unlike non-SEZ exports,

which are predominantly commodities (for example, gold, cocoa, and bananas). Last,

non-SEZ exports lack diversification: gold and ferronickel account for half of GTR

exports, while the other products have single-digit shares (figure 2.20)

14

. In contrast,

SEZ exports are less concentrated, with the highest share (medical devices) reaching

18 percent, with tobacco, electrical equipment, and jewelry also all reaching double-

digit shares.

15

In this context, maximizing linkages between SEZ and non-SEZ firms

is an important challenge. Pro-business reforms have not always yielded the expected

results in terms of linkages, and tax incentives remain the default measure to address

market failures. Recent decades did, however, witness an array of economic reforms

including the liberalization of foreign exchange transactions, trade agreements, and the

elimination of price controls and of restrictions on FDI in almost every sector.

x

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

A ROADMAP FOR THE SHORT TO MEDIUM TERM

Given this country and private sector context, the global reconfiguration of some

global value chains (GVCs)—often referred to as “nearshoring”—represents a timely

opportunity for the DR to harness and pivot toward a more competitive, inclusive,

and resilient economic trajectory. Trade tensions between the United States and China,

COVID-19, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are leading to the reversal of global

economic integration. Firms and policy makers are increasingly considering trusted

countries with aligned political preferences to make supply chains less vulnerable to

geopolitical tensions. However, the interest to relocate operations is not uniformly

distributed across regions, with surveys of multinational companies indicating that

only 4 percent of the global reshuing of FDI is considering Latin America as a

destination. The DR’s outlook, however, seems favorable within this global setting.

In 2022, total FDI closed 33 percent higher than its pre-pandemic level and surpassed

the US$4 billion threshold for the first time in history, with SEZs’ FDI inflow being 39

percent higher than in 2019 (figure 2.25)

16

. Most importantly, industrial SEZ exports

increased 11 percent in real terms between 2019 and 2022, with medical devices and

pharmaceuticals contributing to almost half of that growth

17

.

To fully seize this opportunity, the Dominican Republic’s unique selling proposition

should be more strongly based on structural and sustainable competitive advantages.

Beyond capitalizing on its natural endowments, such as its strategic geographic

location, the DR should strengthen its assets in key enabling sectors such as education,

logistics, and financial services by harnessing the private sector and leveraging capital

markets. For example, the DR could accomplish desired results by prioritizing policy

eorts that structurally improve its human capital, industrial infrastructure, and

energy mix while also promoting capital market mobilization instruments, such as

specialized investment vehicles and green bonds. It could further support public-private

partnerships and cross-border private sector investment. The structural reinforcement

of its assets and enabling sectors will gradually decrease the country’s dependence

on fiscal incentives and widen the range of policy options to level the field across the

economy while sustaining and increasing the attractiveness of the DR for investors. In

turn, this reinforcement will have the added value of reducing barriers to growth for

small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to become suppliers to exporting firms (or start

directly exporting) and to boost formal job creation.

To help inform this pivot, this Country Private Sector Diagnostic (CPSD) identifies

three cross-cutting policy areas that are critical for a more resilient and inclusive

(including on gender aspects) path forward, and also provides sector assessments

of three sectors where private capital can be leveraged to contribute to this pivot.

The three identified policy challenges are (a) improving the business environment by

gradually decreasing complexity and the fragmentation of the institutional context; (b)

enhancing education and skills development to reduce the skills mismatch in sectors

with strong export potential and to improve linkages with local suppliers; and (c)

reforming the electricity sector to reduce the cost of energy, increase the reliability

of the grid, and promote the renewable energy sector in line with the country’s

decarbonization targets. The three sector assessments focus on one tradable sector

(medtech), one domestic sector (real estate with a focus on eco-industrial parks), and

one enabling sector (agri-logistics). The sector-assessment sample is meant to merely

illustrate the potential of harnessing and accelerating private investment in a three to

five years’ horizon, in a way that supports diversification (away from dominant sectors

such as tourism and minerals) while promoting a more resilient and inclusive economy.

xi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A Complex Business Environment and Fragmented Institutional

Context

The DR has implemented several reforms to ease constraints in dierent business

regulatory areas, but the prevailing business environment continues to be perceived

as opaque and aected by excessive discretion. Measures over the course of recent

years include the introduction of the Formalízate one-stop shop for business

registration; the 2019 amendment of the Law of Commercial Corporations and

Limited Liability Companies; the enactment of a new Law on Movable Collaterals in

2020; the introduction of a specialized commercial court division and a mediation-

and-conciliation framework; the adoption in 2017 of the Law on the Securities

Market; the enactment of the law on Publicly-Oered Securities; and Law No. 167-

21 on Regulatory Reform and Simplification of Administrative Procedures. More

recently, in 2022 the Portal for Dominican Government Services was launched.

This platform centralizes information about dierent administrative procedures.

18

Reform eorts have resulted in gradual improvements in international rankings,

but the country’s standing across various indicators remains low. The Transparency

International’s Corruption Perception Index 2022 ranks the DR at 123rd position out

of 180 countries, up from 137th out of 180 countries in 2019.

19

In the World Bank’s

Worldwide Governance Indicators 2022 update, the DR scored 54.8 out of 100 points

in the Government Eectiveness indicator, up from 38.9 in 2019.

20

The DR also ranks

78th out of 141 in the World Economic Forum’s overall Global Competitiveness Index

2019, up from 92nd out of 138 countries in 2017.

21

Complex business regulations and fragmented institutions play a key role in creating

the conditions for an opaque business environment. The processes of licensing and

authorization are unwieldy, mainly as a result of (a) a lack of database and information

sharing across agencies; (b) a lack of eective risk-based regulations and systems;

and (c) the poor or partial digitalization of licensing and authorization processes.

Various policies and lack of action have aected the problem. First, the presidentially

championed Zero Bureaucracy initiative aims to streamline and digitalize licensing

and procedures for investors, but existing fragmentation hampers reform eorts.

Second, an insucient level of coordination and synergies among the large number of

institutions supporting the development of the private sector exacerbates the perception

of a fragmented and complex business environment and reduces the eectiveness

of private sector support. For example, interviews consistently pointed to weak

operational coordination between institutions responsible for investment promotion

and aftercare, suggesting that this task remains dependent on the personal initiative

of appointees, and that a framework for a clear vision, strategy, and coordination is

pending. Third, even though some tax exemptions under the various fiscal regimes

have arguably helped attract FDI and diversify exports, others have been found to

constrain productivity and backward linkages.

xii

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

The assessment recommends specific policy actions that would enhance DR’s

competitiveness and business climate. The critical steps to streamlining, modernizing,

and digitalizing the regulatory environment for business include (a) creating a fully

integrated transactional service delivery platform for the private sector (across all

regimes, even if gradually); (b) automating the approval process of firm establishment;

(c) digitalizing and streamlining the licensing processes; (d) introducing risk-based

approaches for licensing and permitting;(e) providing comprehensive and interactive

information on all available incentives on the websites of investment promotion

agencies; and (f) strengthening the regulatory and institutional framework for digital

governance. Recommendations for improving the coordination and client orientation

of private sector support institutions include two measures: (a) mapping and

comparing the de jure and de facto mandates and activities of the three FDI promotion

and aftercare-related agencies and (b) articulating a results-based framework for

client orientation and strategic coordination between the three institutions through

an interinstitutional memorandum of understanding or a special purpose vehicle. And

finally, for improving FDI attraction and retention, it is recommended that an ex post

holistic assessment be made of the impact of incentives in the DR, the corresponding

return on investment, and reforms needed, leveraging the International Monetary

Fund–provided assessment tools already used by the Ministry of Finance of the

Dominican Republic.

The Skills Gap and Low-Quality Education

Educational outcomes in the Dominican Republic are far below what would be

expected for a country at this level of economic development. Labor productivity is

roughly half the level of aspirational peers and 44 percent lower than in structural

peers

22

. The resulting skills shortage and mismatch is one of the most important

structural obstacles to private sector investment and growth across the economy—

but especially so for high-value-added activities. For example, a detailed assessment

of the skills, competencies, and professional training for logistics in the Dominican

Republic conducted by the World Bank in 2023 revealed that there is increased

stang demand driven by the growth and expansion of the logistics sector, with the

biggest share of vacancies at the operative level (50 percent to 60 percent), and at

the administrative level (30 percent to 40 percent). The survey found a shortage of

candidates with adequate logistics skills in the market, with 85 percent of interviewed

companies perceiving a shortage of qualified candidates for operative level positions

(especially crane operators) and 78 percent indicating a shortage of qualified sta

for administrative level positions. Consequently, most companies recruit personnel

without proper knowledge, and then invest in on-the-job training related to the

specific technical or operational aspects of the job. The availability of pre-employment

education for logistics is limited, with 45 percent of companies indicating limited

vocational oerings and 75 percent indicating limited university and college oerings,

the provision of which is further exacerbated by weak foundational skills in science,

technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

xiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Progress toward gender parity in education has not been matched by a comparable

increase in economic opportunities for women. The country ranks 112 out of 189

countries worldwide in the 2020 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

Gender Inequality Index, and the COVID-19 crisis has widened existing gaps,

especially among the most vulnerable. Women are more likely than men to experience

unemployment and to work fewer hours; they are also likely to earn less than men even

when employed in the same sector (on average they earn 85 percent of men’s earnings).

The wage gap is even larger in the informal sector, where women make only 60 percent

of men’s earnings on average. Top interventions to close gender gaps include expanding

access to aordable and quality child care, facilitating school-to-work transition,

attracting more women into STEM fields, and improving the performance of women-

owned firms.

The assessment recommends specific actions by the private sector to close the skills

gap across industries in the Dominican Republic, including (a) leveraging performance-

based skills by private sector workers in industrial sectors such as logistics, medtech,

or other growing fields, based on successful work placements; (b) increasing

labor force proficiency in English through a comprehensive language program; (c)

improving awareness of job and career opportunities in these growing sectors and

increasing educational enrollment in STEM-related fields; (d) increasing and scaling

sector-specific training programs focused on specialization areas, technologies, and

capabilities identified by firms in these growing sectors; (e) adapting, scaling, and

improving university programs that provide specialized skills relevant for growing

sectors through collaboration between industry and academia; and (f) reforming

incentives to support FDI investors who provide targeted continued education and

upskilling of employees.

Energy and Electricity

Poor performance of the Dominican Republic’s electricity sector is a major

impediment to a sustainable and inclusive economic growth. The electricity sector

is characterized by one of the region’s highest prices for the industrial sector, a

precarious and economically inecient supply, frequent outages, a fragmented

institutional framework, weak regulatory enforcement, and a financially unsustainable

distribution segment that requires large subsidies from the central government. In

addition, high reliance on imported fossil fuels for generation (80 percent of total

supply)

23

poses a threat to the financial and environmental sustainability of the sector.

To enhance climate resilience and sustainability, the government has facilitated the

development of renewable energy resources to mitigate the country’s dependence on

imported fossil fuels and lower the sector’s carbon intensity. The Electricity Pact is

supporting a least-cost approach to power generation through a recently signed decree

establishing competitive auctions for renewable energy with opportunities for local

and international project developers. Removing distortions in the energy sector can

potentially unlock a 0.09 percentage point increase in the GDP by reducing blackouts

that disrupt manufacturing activity.

24

xiv

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

The assessment recommends specific policy actions to increase the penetration of

renewables in line with the country’s decarbonization targets. Recommendations

include (a) implementing and streamlining competitive tenders to lower taris and

mitigate the risk of developer concentration; (b) optimizing the stability and integration

of renewable energy into the power grid; (c) preemptively addressing environmental

and social issues through a standardized approach, including biodiversity and land

rights acquisition assessments; (d) enabling the introduction of battery systems in the

market; and (e) increasing investment in the transmission sector.

KEY PRIVATE SECTOR INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES TO

GROW MARKETS IN A SUSTAINABLE ECONOMY

While cross-cutting constraints are gradually addressed, the CPSD also highlights

opportunities in three sectors where private sector capital and investment can be

leveraged to diversify and boost exports while helping the economy pivot toward a

more resilient and inclusive trajectory. First, the medtech assessment helps showcase

how private sector investments and public policy actions can support growth in high-

value-added manufacturing sectors (which are also leading employers of women),

while helping to develop backward linkages and scale a new growth paradigm that

is more inclusive of local SMEs and local talent. Recommendations aim to help seize

potential nearshoring opportunities (and manufacturing FDI more broadly) and

strengthen the broader set of high-value-added manufacturing sectors in the DR, such

as electronics and pharmaceuticals. Second, the industrial real estate sector assessment

shows how ripe opportunities for the development of eco-industrial parks (EIPs) can

improve access to the next generation of serviced industrial land. A better industrial

infrastructure will strengthen the competitive advantage of the DR and reduce the

share of fiscal incentives in its unique value proposition. The private sector already

plays a leading role in oering serviced industrial land in the DR, but reforms can

help better leverage capital markets, increase resilience in the face of disaster risks,

decarbonize the growth of manufacturing, improve the circularity of the economy, and

position the DR as a leading destination in Latin America for green FDI. Third, the

agri-logistics sector assessment identifies investments and reforms that can promote

climate-smart agriculture, while also providing a blueprint of how logistics, more

broadly, can better leverage the geographic position of the DR to promote higher-

value added exports. The rationale for the shortlisting of these three sectors is rooted

in many considerations (elaborated upon in the report) that include export and FDI

diversification away from dominant sectors like tourism), the wider relevance of the

analysis to similar sectors, and the opportunity to showcase how capital markets

can be leveraged to achieve developmental objectives, as well as complementarity to

recently published diagnostics and reports.

xv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Medtech Sector

The DR is an attractive location for eciency-seeking medtech firms, but addressing

persistent challenges could greatly enhance growth and linkages with the local

economy. The Dominican Republic is a politically and economically stable country

with proximity to US headquarters of multinational corporations (MNCs) that are

major medical device manufacturers. Exports have grown substantially, and since

2009 the medtech sector has rivaled the DR’s apparel sector for the highest volume

of exports and has become the largest exported group of goods with US$2.2 billion

in 2022 (figure 4.4).

25

Many globally leading medtech firms are now present in the

Dominican Republic and their plants supply global value chains of some medical

products such as disposables, surgical and medical instruments, and therapeutic

devices. The sector has also contributed to increasing the skills premium in the

DR labor market and been a leading employer of women (64 percent share of total

employment in the sector - figure 4.5).

26

Global trends are driving the increased demand in the medtech sector in the

Dominican Republic and provide opportunities for private sector investment to

transform health care and facilitate earlier disease detection, less invasive procedures,

and more eective treatments. Demographic factors around the world, such as an

aging population, mass displacement of people, and income polarization, as well as

rapidly increasing spending on health care, are among the trends that are changing the

demand for medtech. Technological innovations are helping companies develop new

models for health care and facilitating a shift from a treatment-of-the-sick approach

(reactive model) to a prevention-and-cure approach (proactive model). Finally,

existing high standards of product safety and quality concerns contribute to a high

concentration in the global industry, as few firms can sustain the high investment

costs required and simultaneously maintain strong global production and marketing.

However, medtech firms have struggled to find local suppliers and continue to rely on

their global suppliers rather than try to source locally, which presents some challenges.

Channeling the growing foreign investment in medtech in the Dominican Republic

into the local economy requires connecting MNCs with firms located domestically

(local or foreign), because most of the growth comes when the already established

MNCs increase their production and add vertically integrated operations. Key

constraints and challenges include (a) reducing the technical gap between the local

suppliers and the MNCs’ requirements, (b) developing technological skills and digital

capabilities, and (c) improving the local entrepreneurship ecosystem. Alternatively,

it would require attracting foreign firms that can source inputs and complete the

supply chain within Dominican territory. All these actions are necessary to build the

foundation for the next wave of FDI (including in other sectors), because proximity

and competitive labor costs are insucient to continue attracting investment in the

medical devices sector.

xvi

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

The assessment identifies opportunities to increase the competitiveness of the medtech

sector in two identified markets:

• Disposable medical devices and therapeutical products for the US market. Most

firms in the Dominican Republic already specialize in producing and exporting low-

risk medical devices, which have the lowest barriers to entry and least demanding

requirements. The main challenges in this segment are related to the regulatory

context and the lack of quality management systems, low technical capabilities

for product design and production, information asymmetry between buyers and

suppliers, and the lack of an accreditation body for sterilization and lab testing

companies. Local suppliers also face long receivables delays and high cost of

improvements to meet requirements, as well as low bargaining power in the face of

international supply contracts and MNC vertical integration. The CPSD identifies

specific private sector investment opportunities for disposables (or Class 1) medical

devices, such as (a) providing increased ancillary services to MNCs, including

sterilization and lab testing, or local production of main packaging supplies, and

(b) increasing local manufacturing of components, such as molded components,

extruded plastic tubes, and metal components.

• Services for health care providers. The general transition toward preventive health

care provides development opportunities for medtech services segments that use

medical devices and technologies supported by information and communication

technology (ICT). The main constraints, however, include limited human capital to

drive higher-value outsourcing services and a low level of English fluency, insucient

experience in existing business process outsourcing (BPO) operations with process

definition and execution requiring teams to use dierent interfaces and automation,

and low research and development (R&D) networking and agglomeration spillovers.

The CPSD identifies specific private sector investment opportunities in services

to health care providers, including investing in local BPO and knowledge process

outsourcing (KPO) companies to position the country as a US nearshore hub of

outsourced services, such as appointment scheduling, and digitalization including

telemedicine, patient portals, and data analytics.

Finally, the assessment recommends specific policy actions to grow DR medtech

markets in three to five years. These include (a) narrowing the certification and

accreditation gap between domestic and international firms; (b) supporting technology

and capability adoption by digitalizing firms and providing incentives to upskill

domestic firms; (c) establishing an R&D program to strengthen firm capabilities in

medtech by improving firm categorization, performing technical audits, piloting

collaboration between anchor firms and suppliers, and developing customized training

programs; (d) increasing access to invoice factoring to local suppliers to improve their

liquidity and increase their investment in competitiveness-enhancing infrastructure,

machinery, technology, and capacity building; (e) shifting the FDI strategy toward

a proactive approach by adopting a nearshoring strategy that targets high-potential

sectors (such as medtech) and reinforcing the value chains and stronger integration

in GVCs; (f) simplifying registration processes for the establishment of medtech

companies under the regime for SEZs; and (g) incorporating the medtech sector in the

priority list when creating a single window centralizing the reception of information

and interconnecting agencies and databases. Importantly, the medtech sector should

especially benefit from skill development interventions aimed at closing the skills

gap, which are outlined in more detail in the section on that cross-cutting constraint,

section 3.2.

xvii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Industrial Real Estate and Eco-industrial Parks Sector

The Dominican Republic has leveraged industrial parks for decades to spur

manufacturing-led growth. As of 2022, 86 of them were dedicated to exports and had

enabled the expansion and diversification of the country’s export basket, with exports

from firms under the SEZ regime (to which all exporting firms in industrial parks

belong) increasing from US$4.2 billion in 2010 to US$7.8 billion in 2022.

27

Although

the share of total exports of goods by these firms had decreased from 62 percent to

57 percent in the same period, the main reason was the emergence of gold exports

and ferronickel (accounting for 49 percent of total exports by firms under the GTR in

2022 - figure 2.20).

28

Industrial parks have also attracted US$2.9 billion in FDI during

2010–22 (figure 2.12). However, exceptional tax treatment and labor regulations have

also led to trade-os and reduced positive spillover eects. Although the fiscal policy

layer of the Dominican Republic’s industrial parks needs to be further analyzed within

the larger macroeconomic and political-economy context, the essential aspect of the

industrial parks’ value proposition to customers (other than their overall geographic

proximity to US markets and integration with ecient logistic corridors to that

market) lies in the adequacy of the infrastructure and its business services to hosted

industrial activities. Strengthening these aspects can only reduce the weight of fiscal

incentives in the overall unique value proposition.

There has been an acceleration in the demand for serviced industrial land (that is,

industrial parks) in the Dominican Republic (figure 4.11). In 2022, the country had

approximately 49 million square feet of industrial shells (that is, actual buildings

ready to be rented out), of which 47.5 million square feet were occupied, resulting

in a 96 percent occupation rate.

29

Nearshoring estimations suggest that throughout

a 5-year horizon, the country could host between US$1.5 billion and US$2.7 billion

of additional exports, with the baseline growth projections generating a minimum

estimated need of 8.3 million square feet for new industrial shell space or a 19 percent

increase of total capacity relative to 2021.

30

Recent data show that 5 million square

feet have been already built and occupied in 2022, surpassing the one-year growth

estimations of industrial shell space based on nearshoring. Data for 2022 are starting

to confirm that this demand is materializing, as FDI toward SEZs increased by 28

percent compared with 2021 and was 38 percent higher than its pre-pandemic levels

(figure 2.25).

31

With global consumer appetite moving toward more sustainable products, industrial

real estate with environmental and social indicators in place could help the Dominican

Republic increase its export competitiveness in the long term. Eco-industrial parks

provide an alternative to classic industrial land development approaches. Research

has shown that EIPs provide a center of excellence for environmental, social, and

governance (ESG) compliance, knowing that studies show a positive correlation

between ESG-score improvements by firms and their share price. EIPs can also enable

the economy to gradually shift its unique selling proposition from one based on special

fiscal regimes to one based on the quality of infrastructure and services, stronger

resilience to the eects of climate change, and adequate certifications and standards

for firms seeking to decarbonize their production process and compete in the emerging

global green economy—in addition to equally important assets such as improved skills,

business environment processes, and energy reliability and cost.

xviii

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

Among the various constraints that slow down the development of such a new

generation of industrial parks, two stand out: inecient industrial land markets and

limited access to adequate long-term finance. Industrial land markets are inecient

in the Dominican Republic. The lack of a clear ex ante definition of which lands can

respectively be used for residential, industrial, or agricultural purposes creates a lack

of visibility on which assets are available on the market, as well as distortions in their

pricing. Commercial and residential uses (which are higher in density, often with

higher rates of return on investment) can crowd out industrial uses. Taking stock of

this, and of the apparent shortage of land dedicated to industrial development, the

government launched the Santo Domingo 2050 decree, which incorporates 985 million

square feet of public land and dedicates a significant part of it to the creation of an

industrial corridor around the Circunvalación de Santo Domingo Avenue (that is,

the beltway). Provided adequate territorial and land use plans are elaborated shortly,

this policy action can significantly help address the constraint on the short term.

Another key constraint relates to the lack of diversity and depth in the financial market

to provide adequate access to long-term finance to develop green assets and nudge

developers to respond to the demand of industrial land with higher ESG standards.

Finally, the report also highlights gaps in the DR’s legislation as it relates to industrial

parks’ sustainability practices and shortcomings hindering the crowding in of private

sector capabilities into underutilized public assets.

The assessment identifies and describes three main market opportunities where the

private sector can be leveraged to be part of the solution and contribute to resilient and

green industrial growth. In a three- to five-year horizon, projections of nearshoring

opportunities suggest an increase in demand for high-quality industrial land at a higher

rate than recent growth trends, yielding an investment need of up to US$690 million

(see investment opportunity section):

• Establishing special purpose vehicles that tap into capital markets to provide

competitive sources of long-term finance to developers of greenfield EIPs. Total

expansion in industrial shell space in the next five years is projected to be between

4.4 million square feet, based merely on past growth performance, and 8.3 million

square feet, based on the nearshoring-backed baseline scenario. Access to more

suitable long-term finance can increase the interest of the private sector in the

development of EIPs—instead of regular Class B industrial parks (IP)—and real

estate investment trusts (REITs) and debt funds, based on institutional capital

mobilization, could be an option to achieve that goal. EIPs will also help showcase

how IPs can evolve beyond fiscal incentive-based competitive advantages to compete

on a more substantive unique value proposition.

xix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• Green retrofitting of existing parks through sustainability-linked long-term finance,

including corporate loans, bonds, and project finance. The energy eciency of

buildings could increase by 27 percent if the roof and exterior walls were better

insulated, glass eciency for windows were increased, and more ecient lighting

were installed for internal and external areas. In terms of water eciency, a

typical factory shell can save 9.63 percent by employing lower-flow technologies in

restrooms and kitchens.

32

Furthermore, IPs’ exposure to 15 hazards was analyzed

under four hazard categories of wind, water, fire, and geoseismic risk. A preliminary

assessment was conducted of their vulnerability and the adoption of recommended

resilience measures to mitigate relevant hazards. The results suggested that industrial

park assets in the Dominican Republic could strongly benefit from retrofitting and

upgrading to incorporate resilience measures that help avoid economic losses for

park operators and tenants. A range of long-term finance vehicles and instruments

could facilitate that work.

• Investments in utility-scale photovoltaic rooftop systems (PVRS) to decarbonize

industrial growth. PVRSs could ease the burden of high electricity bills significantly,

thereby reducing occupancy costs for tenants. These systems can be significant in

the Dominican Republic where electricity prices are among the highest in the region.

Potential installed capacity of existing industrial parks in the DR is approximately

400 megawatts. From the park operator perspective, an alternative use of PVRSs

is utility-scale generation, which creates an additional line of business for parks

by becoming a renewable energy supplier to the grid through a purchasing power

agreement (PPA) with distribution companies. A major industrial park in the country

is developing PVRS, which could serve as a scalable precedent for a green market

that would benefit from better access to long-term finance.

Finally, the assessment also recommends specific actions to (a) improve access to

serviced industrial land (that is, industrial parks) by promoting coherent land use

planning that identifies suited lands for sustainable industrial development, and their

related infrastructure and connectivity needs; (b) leverage domestic and international

capital markets to provide green long-term finance to the development of EIPs through

seed public financing and investment trusts strictly focused on developing green

industrial parks or EIPs; (c) facilitate access to green finance to existing industrial

zones to strengthen their resilience and promote decarbonization; (d) introduce reforms

that improve EIP-related regulations, such as the adoption of green certifications and

standards for zones and responsible use of resources.

xx

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

Agri-logistics Sector

The Dominican Republic’s geographic position is an outstanding asset for the

development of logistics, yet some challenges in infrastructure and services remain

to be addressed. In terms of transportation infrastructure, the main gaps for agri-

logistics in the DR are related to the insucient and inadequate conditions of

secondary and tertiary roads. Significant investments have been made in the expansion

and modernization of the port and airport infrastructure, but air transportation

infrastructure can further benefit from improvements and regulatory upgrading. As

for services, authorities have made recent strides toward improving the institutional

framework for logistics, but competition and market demand issues in the ground

transportation services sector continue to constitute a major drag on the DR’s logistics

performance. Key challenges include (a) anticompetition practices in the transport

market resulting in uncompetitive price setting for shipments, (b) weak contract

enforcement with producers, (c) informality, (d) empty returns in shipping trips, and (e)

a greatly outdated truck fleet. Weaknesses in cold-chain management (exacerbated by

issues related to energy reliability and aordability) and logistic services are among key

hindrances for export competitiveness in semi-perishable and perishable Dominican

products, such as fruits.

This sector assessment focuses on agri-logistics because of the key role it can play

in driving climate-smart agricultural development, and it highlights constraints

and investment opportunities in three markets for fruit produce. In particular, the

agri-logistics assessment focuses on fruits as a relevant group that oers growth

opportunities in local and global markets. The diagnostic includes a description of the

main global trends in the agricultural markets and their corresponding implications

for agri-logistics agents and processes, which tend to point more strongly toward

shortcomings in “soft” logistics—rather than transport and infrastructure per se. The

agri-logistics value chain, with its constraints and opportunities, diers depending on

the end market.

The first market highlighted in the assessment for furthering competitiveness of the

agri-logistics sector is international buyers in export markets, such as the United States

and the European Union. High-value-added fresh fruits need a reliable cold chain and

traceability with an emphasis on reducing the environmental footprint. Global trends

indicate a growth in consumption of healthy foods and environmental responsibility,

the emergence of new regional and global competitors in the fresh fruit segment,

and an increasing relevance of cold-chain reliability during handling, transport, and

storage. Challenges in the agri-logistics value chain for international markets relate to

(a) poor post-harvesting and handling due to deterioration of secondary and tertiary

road networks, (b) low control of temperature and humidity variables, (c) low cold-

chain capacity in warehousing and consolidation centers, (d) inadequate packaging

and processing and gaps in the last-mile cold chain, and (e) inadequate customs

inspection practices for port and air freight. The CPSD identifies specific private

sector investment opportunities in agri-logistics for this international market that

would help increase the capacity of cold-chain storage and rural collection centers, the

local production of main packaging supplies (such as boxing, strapping, and pallets),

and the sophistication of agri-logistics services provided through data analytics and

technological solutions.

xxi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The second market is in the local hospitality industry (indirect exports). The main

implications of global trends for agri-logistics actors relate to the need to provide

traceability to consumers and hospitality buyers. Hotels also require minimally

processed fresh fruits produce, a better shelf life, and high-quality products, and the

local agricultural sector already supplies 85 percent of the total fresh primary products

required by the tourism industry.

33

Challenges in the agri-logistics value chain for

the hospitality industry include (a) the lack of rural accessibility, (b) post-harvest

heat removal facilities and temperature-controlled warehouses near farms, (c) the

low quality of equipment and noncompliance with delivery times, and (d) the lack of

production capacity and technology for IV range products, those fruits and vegetables

ready for consumption with minimal processing. The CPSD identifies specific private

sector investment opportunities in agri-logistics for the hospitality market that would

improve specialized agri-logistics services, such as on-demand planning and daily

transport with cold-chain capacity of ready-to-eat small batches of locally sourced

products or extension of the services of fruit packaging companies (through skills and

technology acquisition) to include ready-to-eat products—for example, peeled fruit,

juice, smoothies, and sauces.

The third is the local wholesale markets and supermarkets, because the per capita

consumption of fresh fruit and milk in the Dominican Republic is higher than the

world average. The central implication of global trends for the local agri-logistics

supply chain relates to increasing the quality of fruits and food locally sourced by

improving times from farm to the table while supporting local producers in planning

their crops and harvest. Challenges for local wholesale markets and supermarkets

include (a) inconsistent refrigerated transportation from farms to packing houses,

(b) uncompetitive transportation services, (c) obsolete packaging equipment and

technology, and (d) underdeveloped logistics automation processes. The CPSD

identifies specific private sector investment opportunities for the local wholesale

market that would improve the quality of services in the chain from farmer to retailer,

cold-chain facilities for the wholesale market, and specialized transport from farms to

collection centers to supermarkets, wholesale markets, and grocery stores.

The assessment recommends specific actions in the agribusiness logistics sector. These

include measure to (a) improve last-mile logistics, such as structuring investment

projects (by obtaining concessionary loans, blended finance, or equity) to build or

upgrade cold-chain capabilities and facilities; (b) improve first-mile logistics and

collection capacity by supporting firms (particularly SMEs) through concessional

loans or lines of credit to increase cold chain storage and rural collection center

capacity, as well as sophistication of services through technological solutions and

data analysis; (c) facilitate the export process and reduce storage times in the port/

airport by improving awareness of the Single Window for Foreign Trade (VUCE)

and implement an integrated simultaneous inspection system at ports/airports; (d)

develop a comprehensive intervention program to improve food safety; (e) promote

productive alliances and/or value chain–specific public-private dialogues between, on

the one hand, supermarkets and fruit producer associations and, on the other hand,

agri-logistics agents and tourism operators to address information asymmetries and

improve alignment between suppliers and buyers; (f) redefine MERCADOM’s strategy

to reinforce its role as a supplier to other businesses (business-to-business [B2B]),

rather than business-to-consumer (B2C); (g) build skills in areas such as food handling,

pre-cooling, cold-chain equipment and facilities operations, and fruit-packaging

xxii

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

management through a specialized training program; and (h) carry out a supplier

development program, with a financing component (soft loans or matching grants),

for packaging. The agri-logistics sector can also benefit from skills development

interventions aimed at closing the skills gap; these are outlined in more detail in

section 3.2, where the cross-cutting constraints on skills are addressed.

Table ES.1 summarizes all the policy recommendations in the CPSD.

TABLE ES.. SUMMARY OF POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS DETAILED IN THE REPORT

THEME/SECTOR POLICY RECOMMENDATION TIMELINE

Regulatory

Complexity and

Institutional

Fragmentation

Streamlining

and modernizing

the regulatory

environment for

business

• Automate approval process of firm establishment in SEZs.

• Map and concentrate information on all available incentives on the CNZFE

website.

• Digitalize and streamline the licensing processes.

• Introduce risk-based approaches for licensing and permitting.

Short term

• Create a fully integrated transactional service delivery platform for firms.

• Strengthen the regulatory and institutional framework of digital

governance.

Medium term

Improving private

sector institutions

• Map and compare the de jure and de facto mandates of the FDI

promotion and aftercare-related agencies.

Short term

• Articulate a results-based framework through an inter-institutional MOU

between the three investment promotion institutions.

Short term

Improving FDI fiscal

incentives

• Make an evidence-based assessment of all fiscal incentives to quantify

their value addition.

Medium term

Skills Gap and

Low Quality of

Education

Closing the skills gap

(applies to all sectors

covered below)

• Leverage performance-based private sector provision of vocational skills.

• Increase labor force proficiency in English through a comprehensive

language program policy.

• Improve public awareness and attractiveness of jobs in growing sectors

such as medtech and logistics.

Short term

• Establish more comprehensive sector-specific specialized training

programs for skills in high-demand sectors.

• Scale and improve university programs that provide specialized skills in

growing sectors; reform curricula based on industry-academia dialogue.

• Promote FDI investment in continued education and upskilling of

employees.

Medium to long

term

Energy and

Electricity

Increasing

penetration of

renewables

• Implement and streamline competitive tenders by establishing

standardized project documents.

• Optimize the country’s grid renewable energy integration and stability.

• Address E&S issues through a standardized approach.

• Enable the market introduction of battery systems.

Short term

• Increase investment in the transmission sector. Medium to long

term

Note: CNZFE = Consejo National de las Zonas Francas; E&S = environmental and social; FDI = foreign direct investments; SEZ = special economic zone.

xxiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

THEME/SECTOR POLICY RECOMMENDATION TIMELINE

Medical Devices Strengthening

certification and

accreditation

• Adopt measures to narrow the certification and accreditation gap

between domestic and foreign firms.

Short to

medium term

Incubating and

promoting linkages

• Support technology and capability adoption through dedicated programs

with financial instruments.

• Establish an R&D program to increase firms’ investment in higher-value-

added product/service development.

Medium term

• Increase access to invoice factoring to local suppliers to improve liquidity

and increase investment.

Short to

medium term

Orienting FDI

promotion to linkages

• Shift the FDI strategy toward a proactive approach focused on reinforcing

the value chains, and targeting critical suppliers in the GVC, to ensure the

enabling environment for MNCs to invest in the Dominican Republic.

Short term

Closing the skills gap

• Recommendations are consolidated and outlined under the Skills Gap

section.

Short term

Reducing

bureaucratic hurdles

for investment

• Simplify registration processes for the establishment of medical devices

companies under the SEZ regime.

• Incorporate the medtech sector in the priority list when creating a single

window.

Short to

medium term

Eco-industrial Parks Improving access to

serviced industrial

land

• Identify land within Santo Domingo 2050 for EIP development.

• Map the land available for industrial park development or expansion in

existing parks.

• Consider PPP-based development of industrial land owned or currently

managed by ProIndustria.

• Consider the legal process that would allow ProIndustria to hire private

management.

Short term

• Elaborate a comprehensive land use plan for EIP development within

Santo Domingo 2050

Medium term

Leveraging capital

markets and green

finance

• Clarify and codify a regulatory framework of REITs.

• Modify the mandate of public sector trust to mobilize capital markets.

• Promote green finance to retrofit brownfield EIPs.

• Promote the creation of debt funds to facilitate access to long-term

finance.

Short term

• Explore the possibility of creating a public-private REIT focused on EIPs. Medium term

Introducing reforms

to EIP regulation

• Develop a national strategy for EIPs with a potential certification scheme.

• Strengthen institutional support to IP operators.

• Integrate EIP requirements into the development and operation of public-

private developed IPs.

Short term

• Improve building codes associated with green buildings and develop

institutional support that promotes green building certification.

Medium term

Note: EIP = eco-industrial park; FDI = foreign direct investments; GVC = global value chain; IP = industrial park; MNCs = multinational corporations; PPP = public-private

partnership; R&D = research and development; REIT = real estate investment trust; SEZ = special economic zone.

xxiv

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

THEME/SECTOR POLICY RECOMMENDATION TIMELINE

Agri-logistics Closing the skills gap

• Recommendations are consolidated and outlined under the Skills Gap

section.

Short term

Closing the

infrastructure gap

• Adopt multiple measures related to improving last-mile logistics (such

as increasing cold-chain capabilities in ports, airports, and wholesale

markets; building cold storage for cargo inspection processes).

• Adopt multiple measures related to improving first-mile logistics and

collection capacity (such as rural collection centers and cold-chain

storage).

Short Term

Addressing market

and governance

constraints

• Adopt multiple measures (such as implementing simultaneous inspection

systems in ports/airports); ensure interoperability with the VUCE to

facilitate the export process and reduce storage times in the port/airport.

• Develop and implement a comprehensive intervention program to

improve food safety.

• Promote PA between fruit producers and supermarkets.

• Promote PA and/or facilitate PPD between agri-logistics agents and

tourism operators.

• Redefine MERCADOM's strategy to be focused on B2B, instead of B2C.

• Carry out supplier development programs, with a financing component

for packaging in the Dominican Republic.

• Facilitate access to equipment and technology adoption loans.

Short Term

Note: B2B = business-to-business; B2C = business-to-consumer; MERCADOM = Dominican Wholesale Center for Agricultural Supplies; PA = productive alliances; PPD =

public-private dialogue; VUCE = Ventanilla Única de Comercio Exterior.

1

. COUNTRY CONTEXT

. MACROECONOMIC FUNDAMENTALS: STRONG

GROWTH BUT SHRINKING FISCAL SPACE AND LAGGING

INCLUSION

The Dominican Republic (DR) experienced strong overall economic growth during

the past decades. The country has a population of 10.4 million (2020) and is the

largest economy of the Caribbean and Central America, and eighth largest in Latin

America and the Caribbean (LAC), reaching US$114 billion in 2022. With growth

averaging 5.8 percent per year from 2005 to 2019, the DR outperformed most LAC

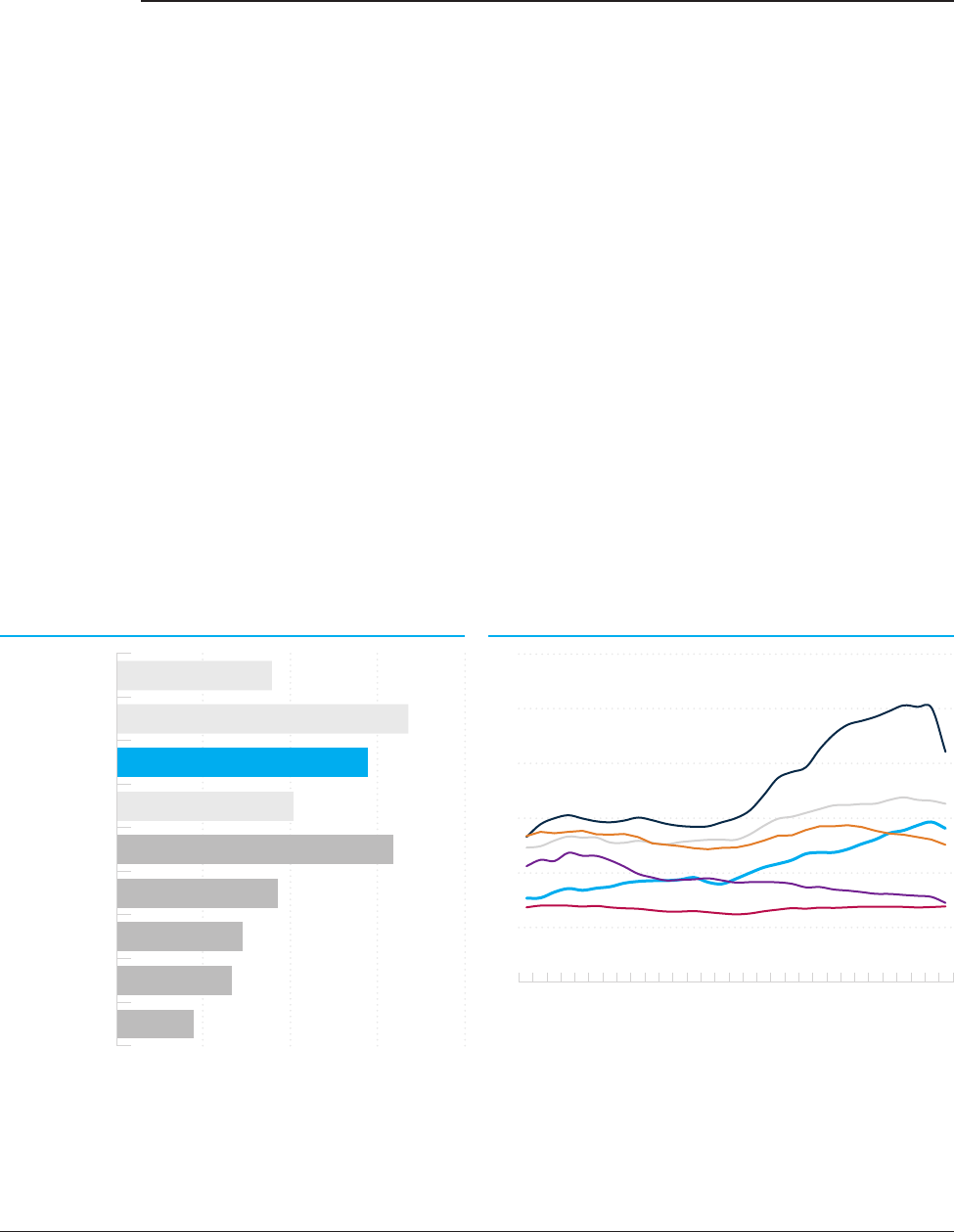

economies and became one of the top performers among emerging markets (figure

1.1). Two decades of fast economic growth (interrupted only in 2002–03 by a banking

crisis and more recently by the COVID-19 pandemic) allowed the country’s per capita

income to increase almost threefold.

34

As figure 1.2 indicates, there was a catch-up or

economic convergence process in the DR. The remarkable growth was underpinned

by macroeconomic stability and an array of market-oriented economic reforms. The

reforms started in the 1990s and included tax incentives, the liberalization of foreign

exchange transactions and trade agreements, and elimination of price controls and of

restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) in almost every sector.

FIGURE .. REAL GDP GROWTH, AVERAGE %

FIGURE .. GDP PER CAPITA IN THE DR AND SELECTED

PEER COUNTRIES IN PERCENTAGE OF US GDP PER CAPITA,

Source: CPSD core team based on World Bank World Development Indicators dataset.

Note: GPD = gross domestic product.

*IBRD and IDA countries only for regional aggregates. GDP per capita is measured using 2017 constant prices adjusted by purchasing power parity.

GUATEMALA

PANAMA

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

COSTA RICA

SOUTH ASIA

EUROPE &

CENTRAL ASIA

MIDDLE EAST &

NORTH AFRICA

LATIN AMERICA &

THE CARIBBEAN

OECD MEMBERS

%

%

%

%

%

%

%

% % % % %

COSTA RICA

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

PANAMA

JAMAICA

GUATEMALA

LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN*

.%

2

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC

Poverty and inequality have declined consistently since the early 2010s. While the

poverty rate (defined as the population with less than US$6.85/day, adjusted by

purchasing power parity) increased from 41 to 57 percent of the population over

2002–04 because of the economic shock from the banking crisis, since 2013 there has

been a steady decline, and by 2021 it had fallen to 23 percent. Similarly, the middle

class (incomes between US$13/day and US$70/day) expanded from 25 to 42 percent,

outnumbering the poor in 2014. Income inequality improved (the Gini coecient

fell from 0.51 to 0.38 over 2000–21), as the per capita income for the poorest 40

percent of the population grew compared to the top 60 percent (3.4 versus 2.9 percent,

respectively, during 2004–16 and 6.2 versus 5.8 percent, respectively, during 2017–19).

Despite the country’s sustained growth levels and strong economic outcomes,

improvements in its social indicators remain below target. The rates of poverty

reduction in the DR are comparable to those achieved by other regional peers, despite

the DR’s higher economic growth. Persistent inequality is linked to a lack of high-

quality job opportunities. Despite robust economic growth, more than half of the jobs

in the DR are in the informal sector, mostly concentrated in nonexporting activities.

Additionally, the country’s performance in reducing monetary poverty has narrowed

the gaps between rural and urban areas, but there is room for improvement. Three

out of every four people that moved out of poverty between 2017 and 2019 resided in

urban areas, where poverty rates were already lower than in rural areas.

35

COVID-19

emergency transfers narrowed the urban-rural gap, but recent simulations suggest

that after their removal, the gap could widen again since the crisis did not remove

structural inequalities across regions. Finally, since 2005, poverty rates have been

consistently higher among women than men, and by 2019 the share of women-headed

households living below the poverty line was 25 percent (versus 19 percent for men-

headed households).

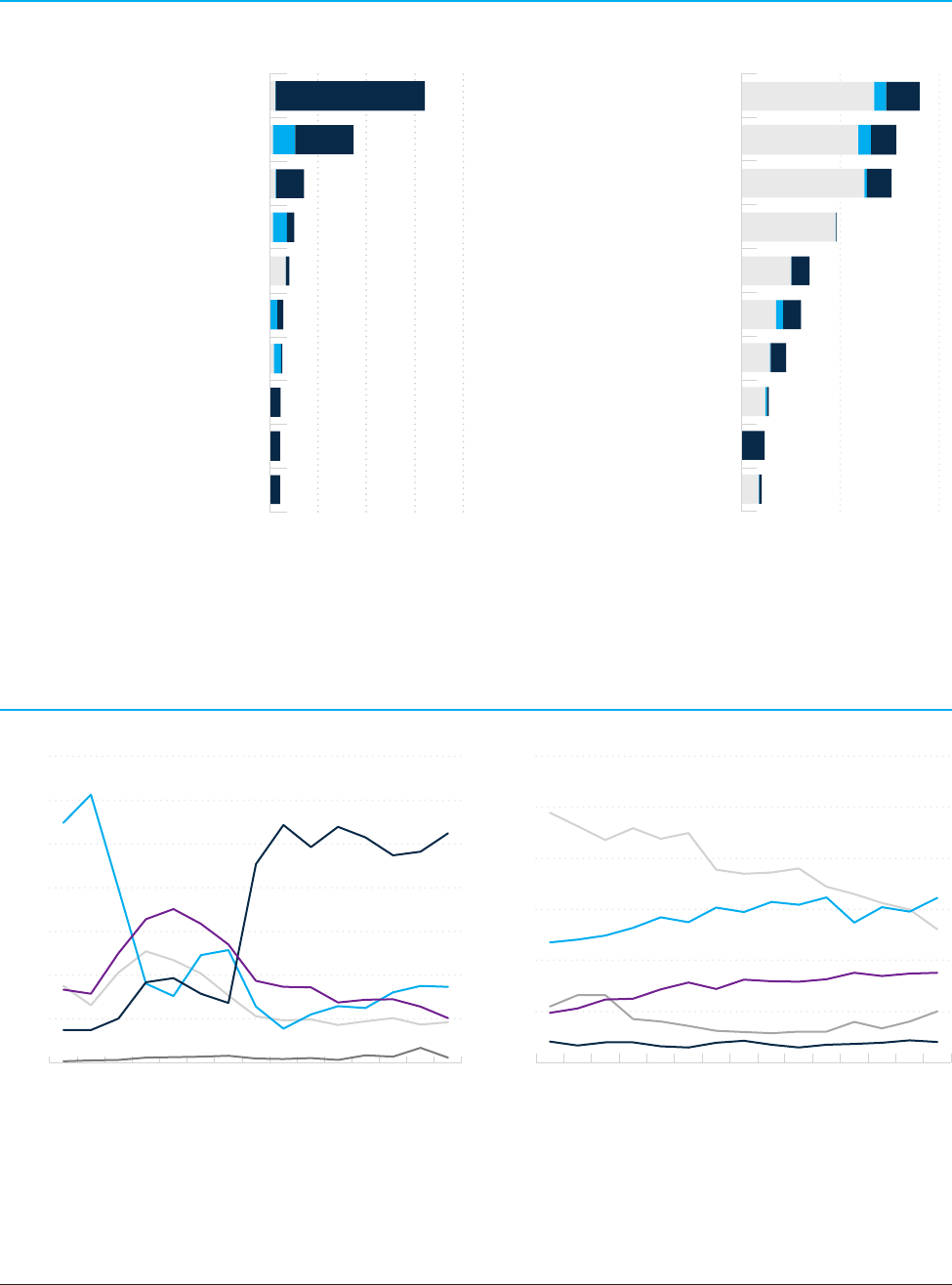

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank assessments, the

public-debt-to-GDP ratio remains sustainable but has been increasing steadily and

significantly since 2005 (figure 1.3), reflecting fiscal weaknesses that were compounded

by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the central government balance deteriorated

sharply (figure 1.4), due largely to emergency spending, resulting in an increase in debt

levels—notably external. The 4.2 percent of GDP fiscal stimulus that was adopted

in 2020 in response to COVID-19 is slowly being lifted as the recovery gathers pace

(COVID-19-related spending amounted to about 3.3 percent of 2020 GDP, while

forgone revenue reached 0.9 percent of GDP). Although public debt declined in 2021

as the fiscal position gradually returns to prepandemic levels and growth recovers,

weaknesses in the government debt profile expose it to risks from peso depreciation

and higher interest rates globally, because external debt accounts for three-fifths of

total consolidated debt (figure 1.3).

3

COUNTRY CONTEXT

FIGURE .. CONSOLIDATED PUBLIC DEBT AS PERCENTAGE

OF GDP

FIGURE .. CENTRAL GOVERNMENT FISCAL BALANCE AS

PERCENTAGE OF GDP

Source: CPSD team’s calculations based on data from Minister of Finance and Central Bank of the Dominican Republic.

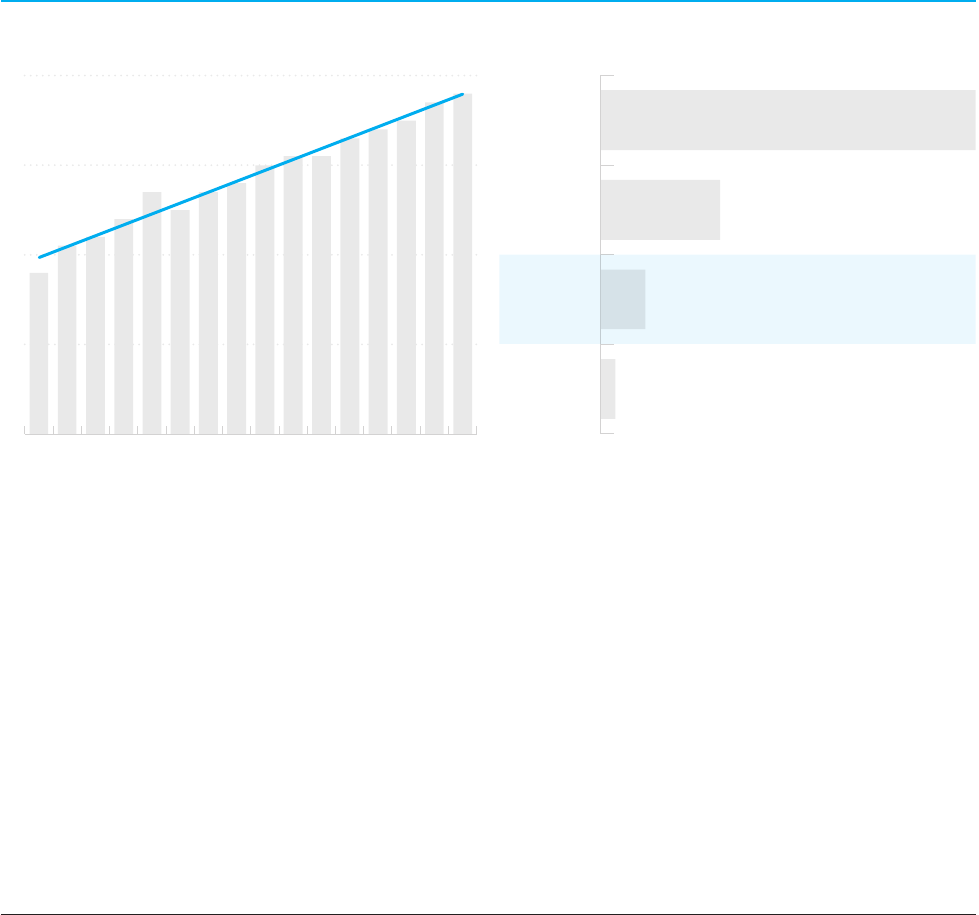

Beyond the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on public finances, the Dominican

Republic has historically been among countries with the lowest levels of revenue as a

share of GDP in the region (figure 1.5). Low tax revenues can be partially attributed