Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Research Monograph

Understanding COVID-19

Among People of Dominican

Descent in the U.S.:

A Comparison of New York, New Jersey,

Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania,

Rhode Island and Connecticut

Ramona Hernandez, Ph.D.

Pedro Ortega, Ph.D

Nancy Sohler, Ph.D.

Sarah Marrara, M.S.

Understanding COVID-19

Among People of Dominican

Descent in the U.S.:

A Comparison of New York, New Jersey,

Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania,

Rhode Island and Connecticut

Ramona Hernandez, Ph.D.

Pedro Ortega, Ph.D

Nancy Sohler, Ph.D.

Sarah Marrara, M.S.

Research Monograph

Dominican Studies Research Monograph Series

About the Dominican Studies Research Monograph Series

e Dominican Research Monograph Series, a publication of the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, docu-

ments scholarly research on the Dominican experience in the United States, the Dominican Republic, and

other parts of the world. For the most part, the texts published in the series are the result of research projects

sponsored by the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute.

About CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Founded in 1992 and housed at e City College of New York, the Dominican Studies Institute of the City

University of New York (CUNY DSI) is the nation’s rst, university-based research institute devoted to the

study of people of Dominican descent in the United States and other parts of the world. CUNY DSI’s mis-

sion is to produce and disseminate research and scholarship about Dominicans, and about the Dominican

Republic itself. e Institute houses the Dominican Archives and the Dominican Library, the rst and only

institutions in the United States collecting primary and secondary source material about Dominicans. CUNY

DSI is the locus for a community of scholars, including doctoral fellows, in the eld of Dominican Studies,

and sponsors multidisciplinary research projects. e Institute organizes lectures, conferences, and exhibitions

that are open to the public.

Graphic Designer & Layout Artist

Javier Pichardo

Subscriptions/Orders

e Dominican Studies Research Monograph Series is available by subscription, individual copies, and bulk

orders. Please visit our website to place your order or subscription request.

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

e City College of New York

160 Convent Avenue, NA 4/107

New York, NY 10031

T 212.650.7496

F 212.650.7489

E dsi@ccny.cuny.edu

www.ccny.cuny.edu/dsi

Copyright © 2022 CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Executive Summary

e present study “Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.S.: A

Comparison of New York, New Jersey, Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Connecticut”

is the rst research study to examine the experience of people of Dominican origins residing in the United States

(U.S.) amidst the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. e current study is based on a probabilistic

and representative sample of Dominicans across the seven states in which the majority—85%—of Dominicans

living in the U.S. reside.

e Dominican Studies Institute (CUNY-DSI) at City College and the School of Medicine, both of the

City University of New York, conducted this study. ese institutions brought together a team of researchers

who worked on the design of the study and the parameters of the data analysis. e purpose of the study was

twofold: First, to create knowledge on COVID-19 based on empirical evidence as it relates to the Dominican

people and, second, to encourage the scientic community, particularly in the area of health, to study the

eects of the pandemic on the dierent ethnic groups that make up the U.S.

Methodology

is study is the rst to disaggregate people of Dominican origin in the U.S., and analyze how they have

been aected by the COVID-19 pandemic. e survey was conducted between October 5 and November 11 of

2021 and is based on a probabilistic sample of 794 people of Dominican origin, residing in seven states: New

York, New Jersey, Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. e largest portion

of the sample (N=554; weighted N=634.5) was drawn from six northeastern states. e remaining sample

(N=240; weighted N=159.5) was drawn from Florida. Using this strategy, we administered surveys online and

via telephone. Criteria for inclusion in the study were being at least 18 years of age and having been born in

the Dominican Republic or identifying as being of Dominican ancestry. e survey was administered in either

English or Spanish depending on the respondent’s preference. Participants were given a $25 gift card at the

conclusion of the survey as compensation for their time and participation.

i

Main Findings

Percentage of incidence of COVID-19

(1) Twenty-four percent of respondents reported having contracted COVID-19 themselves.

(2) Among those who were infected with COVID-19:

• 90% reported that they isolated in their home away from other household members;

• 11% said they had been hospitalized.

(3) Twenty percent of Dominicans interviewed said that someone else in their household contracted

COVID-19; 29% reported that relatives in another household contracted the virus, and 28% said they

knew someone else who contracted it.

Vaccination

4) An astonishingly high 77% of those interviewed reported that they had been vaccinated at the time of

the survey, between October 5 and November 11, 2020.

5) e proportion of people of Dominican origin who are vaccinated is likely to rise to 89% if we add the

percentage of those who, at the time of the survey, reported that they were planning to be vaccinated

in the near future.

6) Only 4.2% of respondents reported that they did not plan to vaccinate because they did not believe

in vaccines.

7) Of vaccinated Dominicans, the majority received the Pzer vaccine (47%) or Moderna (32.0%), while

a small percentage received the Johnson and Johnson vaccine (16%).

8) Among vaccinated respondents, an overwhelming majority (93%) reported having had received the

vaccine in their state of residence, 5% in another U.S. state, and 2% in the Dominican Republic.

Reasons that motivated Dominicans to get vaccinated

9) Seventy-ve percent of Dominicans got the vaccine primarily to protect themselves from COVID-19,

while 20% said they were vaccinated primarily because it is a social responsibility. In comparison, a

small proportion reported having been vaccinated due to social pressure (2.7%).

Time spent to get to the vaccination place

10) A majority of Dominicans (71%) commuted for less than 30 minutes from their residence or workplace

to obtain a vaccination. A substantial proportion said they commuted between 30 minutes to an hour

(24%), and a smaller proportion said their commute was longer than an hour (5%).

ii

Use of masks against COVID 19

11) Seventy-nine percent of Dominicans reported that they “always or almost always” wore a mask in indoor

public settings at the height of the rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, while 13% reported that they

“sometimes” wore a mask, 4% “rarely” wore a mask and only 3% reported “never” wearing a mask.

12) e percentage of mask use was high especially in states where COVID-19 was more prevalent, such

as New Jersey (86%) and New York (82%). In Florida, three-quarters of Dominicans wore masks.

13) With regard to the current use of face masks, there is variability by age and place of birth:

• 90% of those 50 years of age and older reported “always or almost always” wearing a mask com-

pared to young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 (62%);

• 81% of Spanish dominant respondents reported “always or almost always” wearing a face mask

compared to English dominant respondents (75%);

• 84% of respondents born in the Dominican Republic reported “always or almost always” wear-

ing a face mask compared to 62% of their U.S.-born counterparts.

Stress during the pandemic

14) 52% of Dominicans interviewed said they felt nervous, anxious or on edge the week before the interview.

15) Between 14.38% and 42.05% of respondents in each state in our study reported being unable to stop

worrying almost every day the week before the interview. Rhode Island had the largest proportion of

respondents who said that they were worrying almost every day the week prior to the survey.

Sources of information on COVID-19

16) To obtain information on COVID-19, people interviewed were most likely

to consult cable, local or network news outlets (38%) or social media

networks (30%) such as Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter,

WhatsApp, YouTube, and Snapchat.

17) Older Dominicans were more likely to rely on cable, local or network

news outlets (60% of respondents 50 years of age and older) compared

with younger Dominicans (24% for people between the ages of 18 to 29 years).

18) Conversely, younger Dominicans were more likely to rely on social

media for COVID-19-related news (39% among young adults between

the ages of 18 to 29 years) compared with older Dominicans (13% of

people 50 years of age and older).

iii

Table of Contents

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i

Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . i

Main Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . 1

Latino/a/x Research Vacuum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

e Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Attitude Towards Vaccines and Propensity to Vaccination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Reasons for Vaccination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Accessing Vaccination Places . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Mitigation Strategies for Combating the Spread of COVID-19 . . . . . .. . . . . . . . 11

Stress and the Pandemic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . 13

Main Sources of Information on COVID-19 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Conclusion & Policy Recommendation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Works Cited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

1

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent

1

in the U.S.:

A Comparison of New York, New Jersey, Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania,

Rhode Island and Connecticut

2

Authors:

Ramona Hernandez, Ph.D., Professor of Sociology & Director CUNY DSI, CCNY

Pedro Ortega, Ph.D., Post-Doctoral Fellow, CUNY DSI, CCNY

Nancy Sohler, Ph.D., Associate Medical Professor, CUNY School of Medicine, CCNY

Sarah Marrara, M.S., Senior Researcher, CUNY DSI, CCNY

Introduction

Despite the relative newness of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the scientic community has already produced a

considerable amount of research related to the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, this research has focused on

health outcomes associated with infection, its genetics and functioning, nding ways to neutralize the virus

and/or take it out of circulation, its impact on healthcare systems, and its economic impact, both gains and

losses. Probably the most remarkable COVID-19-related research is the rapid development of several vaccines

for adults and children, in a quest to prevent further spread and mutation of the lethal virus in any of its

variations (Creech, 2021; Tregoning et al., 2021; Kahn et al., 2020). Equally notable is the impact of research

guiding recommendations to prevent the spread of the virus, including its newest variant, Omicron, circulating

at the time of this writing (Abassi, 2021) that has made new behaviors, avoiding crowds, covering part of one’s

face, and keeping six-feet apart in public spaces, socially normative nowadays in the United States and other

parts of the world.

On April 11, 2020, near the start of the pandemic, Aleem Maqbool (2020), wrote in BBC News, Washington,

about the impact of COVID-19 on the African American population: “… the racial disparities shown in the

number of people dying of coronavirus-related causes have sadly been unsurprising.” Since then, researchers in

the elds of medicine and social science have contributed rigorous studies on the subject, highlighting racial

and ethnic disparities and injustices related to the pandemic.

Ford, Reber, and Reeves (2020) examined the racial gap in death rates associated with COVID-19 across

the U.S. ese colleagues found that:

Death rates among Black people between 55-64 years are higher than for white people aged 65-

74, and death rates are higher for Blacks aged 65-74 than for whites aged 75-84, and so on. In

every age category, Black people are dying from COVID at roughly the same rate as white people

more than a decade older. Age-specic death rates for Hispanic/Latino people fall in between.

e same pattern was found in a study of mortality rates in England (Aldridge, 2020), which reported that

Black African, Black Caribbean, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian communities are at increased risk for death

compared with their White Irish and White British counterparts.

1 In this study, the term “people of Dominican descent” refers to Dominicans born in the Dominican Republic and people

born in the U.S. to Dominican parents. Similarly, for readability purposes, the terms Dominican and people of Dominican descent

or ancestry will be used interchangeably throughout the study.

2 e order of names of states is based on the demographic size of the population of Dominican descent in the U.S. States

are listed on a descendent order, from larger to smaller.

2

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

In New York City, Holtgrave et, al. (2020) found that the:

Estimated per-population COVID-19 fatality rates were 0.03%, 0.18%, and 0.12% for

white non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic adults, respectively. e 3.48-

fold disparity for Hispanic, relative to white, communities was explained by dierences in

infection experience, whereas the 5.38-fold disparity for non-Hispanic Black, relative to white,

communities was primarily driven by dierences in both infection experience and in the need

for hospitalization, given infection.

Similar racial/ethnic patterns are reported in studies on COVID-19 incidence and hospitalization among

people segmented by racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Garg et al.,2020; ebault, Ba Tran, Williams, 2020),

perceptions of risk of contagion, and knowledge about the virus (e.g., Gupta, 2020; Alsan et al., 2020; Chinni,

2020; Feldman & Bassett, 2021; NYU Furman Center, 2020; Singh & Koran, 2020; See also Jones, et al. 2020).

In Fall 2020 the COVID-Collaborative, a compilation of leading experts in health, education and the

economy, studied perceptions about the eectiveness of the vaccines against COVID-19 among Blacks and

Latinos (COVID Collaborative, 2020; Wan, 2020). is research revealed drastic dierences between the

groups with regard to their perceptions about the benet of a vaccine. Among Black respondents, only 14%

trusted that the vaccine would be safe and only 18% thought it would be eective in protecting them against

COVID-19. However, among Latino respondents, 34% trusted the safety and 40% trusted the eectiveness

of the vaccine. While trust in or willingness to receive the vaccine has increased across both groups since Fall

2020, (Hamel et al., 2021) these initial ndings are noteworthy.

Latino/a/x Research Vacuum

Despite the substantial data on race/ethnicity pattern, relatively little research attention has focused

specically on how COVID-19 has aected the Latino/a/x population. It is unclear if the current COVID-19

research ndings for the Latino/a/x population as a whole applies to the dierent national/ethnic subgroups. It

is therefore worth asking whether the virus has impacted the dierent Latino/a/x subgroups in the same way

and in similar proportions, given the groups national and cultural diversity. In a similar vein, it is important

to know the impact of COVID-19 on the immigrant population as compared with immigrants’ U.S.-born

children. Nativity status diers dramatically among the national/ethnic subgroups, with some group’s

populations consisting of up to 70% of U.S.-born.

Likewise, there is a generalized view that the Latino/a/x population has hesitated to undergo vaccination

against COVID-19, as evinced in the systematic and multimillion-dollar campaign specically targeting

Spanish-speaking people (Leon 2021; Preidt 2021). Yet, it is not known whether all Latino/a/x subgroups

had similar baseline attitudes about vaccination and it has not been explored whether they have reacted in a

similar fashion to interventions to increase vaccination uptake. Ascertaining variation in Latino/a/x groups’

responsiveness to the dierent interventions not only acknowledges the cultural and historical diversity of the

Latino/a/x population, but it may be a more eective and cost-eective strategy as well.

e demographic weight of the Latino/a/x population and its forecasted growth in the coming years is an

inescapable reality. In the same way, it is a reality that the Latino/a/x population is not homogeneous and this

heterogeneity matters because it informs behavior in society. ese realities must be addressed in COVID-19

research and public health campaigns.

For example, the most recent data indicate that the burden of COVID-19 on the Latino/a/x population is

larger than previously estimated in terms of excess mortality (Sheils 2021). In New York City, for instance, one of

the cities most aected by COVID-19, the cumulative case rate and cumulative hospitalization rate exceed Blacks,

3

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Whites, and Asians. (Despres 2021) ough Dominicans make up the largest Latino/a/x population in New York

City, there is not one single study pinpointing at whether the Latino/a/x that had died there were of Dominican

descent. Yet, personal Facebook pages and word-of-mouth news systematically disseminated heartbreaking

information about the many Dominicans who were being hospitalized or had passed because of COVID-19.

Our study has two purposes. First, to create knowledge to help ll research gaps by examining the impact

of COVID-19 on the population of Dominican descendants residing in the U.S. Second, to motivate the

scientic community conducting research on health issues to perceive the Latino/a/x population as one that

is not homogeneous but one that is characterized by inherent dierences produced by historical and cultural

experiences and contexts. Such a perspective would not only be in consonance with the group’s reality but

would also be innovative, reecting scientic advances.

A nal note on the contributions of this study: Dominicans as a group sit rmly at the intersection of

Black/Afro and Latino/a/x identity. Understanding how the COVID-19 virus has impacted them and, in

turn, how they have dealt with it, may prove useful for understanding similar population segments. Likewise,

with this study we provide new cultural perspective on disease management and mitigation eorts, while

further dissecting/interrogating the role of race, ethnicity, nativity, and socioeconomic status on COVID-19’s

disproportionate impact in communities of color. COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic the world faces,

lessons learned from this study may prove life-saving both now and in the future.

4

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

e Study:

Attitude Towards Vaccines and Propensity to Vaccination

We evaluated the attitude and propensity of Dominicans to be vaccinated at the time of the survey. e

results of the survey reveal that the population of Dominican descent responded massively and positively to

the COVID-19 vaccination process. Analysis show the following results: over two-thirds of respondents (77.

29%) reported having been vaccinated at the time of the interview and just under a third (11.76%) stated that

they planned to get vaccinated as soon as they had an opportunity. A small proportion of respondents (6.74%),

reported being unsure whether they would get the vaccine, and an even a smaller proportion of respondents

(4.22%) underscored that they were not going to get vaccinated because they did not believe that getting

vaccinated was the solution to the pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus (see gure 1).

Figure 1

COVID-19 Vaccination and Plans to Get Vaccinated

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

ese results highlight the positive attitude of Dominicans towards the immunization process, getting

vaccinated at high rates. Accordingly, respondents’ willingness to vaccinate also shows the group’s preference

for using protocols approved to confront the COVID-19 pandemic. As indicated in gure 1, most Dominicans

respected the recommendations issued by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Consistent

with the above nding is the low proportion of those who responded that they did not “plan to get vaccinated

because they did not believe in vaccines,” as reected in the aforementioned gure 1.

5

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Figure 2

Receiving all Required Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Of respondents who reported having received a vaccine, 94.84% interviewed indicated that they had

already received or planned to receive all of the required doses in the vaccine series.

Further analysis shows the same positive trend in each of the seven states selected for this study of Dominicans

attitudes towards vaccination as a preventive measure against getting and spreading the COVID-19 virus.

Table 1 presents interviewees’ responses regarding their attitude towards immunization against

COVID-19 stratied by state. While most respondents reported already receiving a vaccination in each

state, Pennsylvania had the lowest proportion of vaccinated respondents (64.56%) and New York reported

the highest proportion (83.02%).

Table 1

Percent of Respondents Who Reported Being Vaccinated

or Plans to be Vaccinated for COVID-19 by State

States

Categories

Received the

vaccine

Plans

to vaccinate

Plans to vacci-

nate uncertain

Does not believe

in the vaccine

(no plans to vaccinate)

New York

83.02 9.82 3.92 3.24

New Jersey

76.30 14.10 5.70 3.90

Massachusetts

72.84 12.69 10.76 3.71

Florida

70.30 12.32 11.27 6.11

Pennsylvania

64.56 17.04 12.20 6.19

Rhode Island

71.85 13.82 14.33 -

Connecticut 78.12 9.83 4.31 7.74

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

6

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

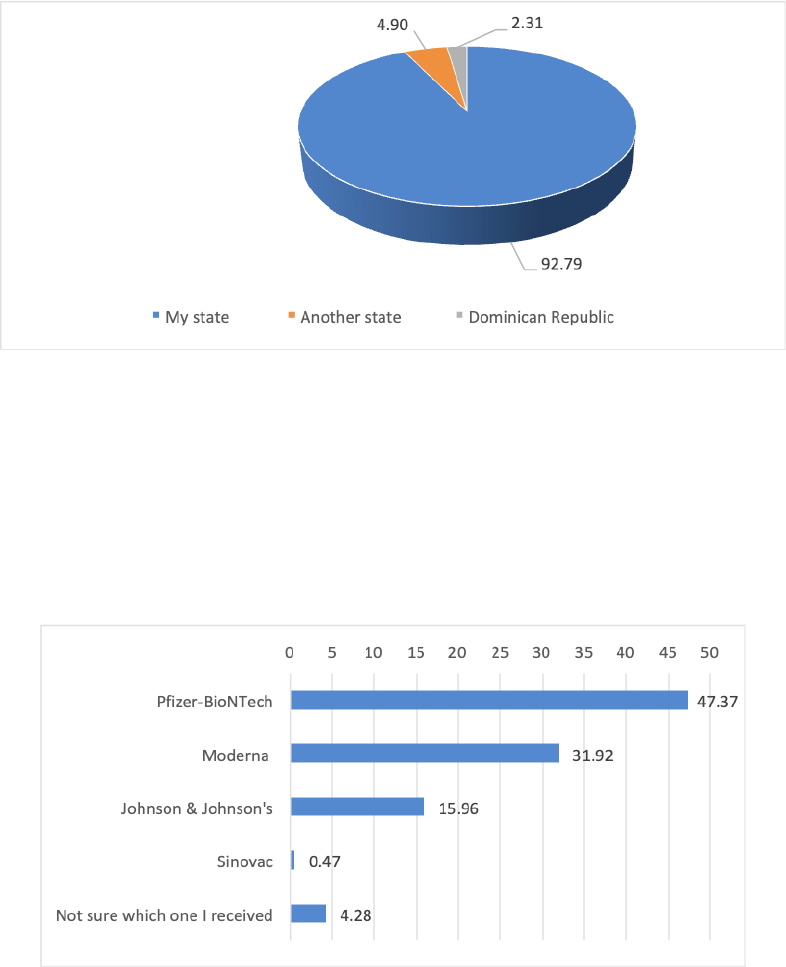

Further examination of the data reveals that, among vaccinated respondents, an overwhelming majority

(92.79%) reported having had received the vaccine in their states of residence rather than traveling to another

state (4.90%) or to the Dominican Republic (2.31%) to receive the vaccine (see gure 3).

Figure 3

Vaccinated Location

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

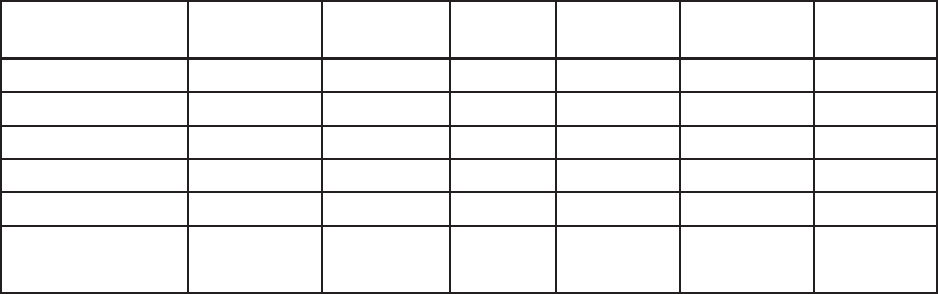

With regards to the vaccine brand received, most respondents reported having received the Pzer vaccine

(47.37%), followed by Moderna (31.92%) and Johnson and Johnson (15.96%). Only 4.28% of vaccinated

people interviewed in this study said they did not remember or were unsure of the brand of vaccine they

received (see gure 4).

Figure 4

Brands of COVID-19 Vaccine

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

7

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Respondents were also asked whether they had any preference regarding vaccine brand. We found that less

half (45.87%) had a preference (see gure 5).

Figure 5

Preference for a Particular Brand of Vaccine

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Disaggregated by gender, we found that men and women reported similar values regarding a preference

for a specic brand of vaccine (48% and 44%, respectively). However, we observed notable dierences by age

group and place of birth. Younger people indicated greater selectivity, with 53% of respondents between the

ages of 18 and 29 reporting a preference for one vaccine over another. is percentage dropped to 40% among

people 50 years of age and older. Additionally, 50% of Dominicans born in the U.S. reported a preference

for one vaccine over another and this dropped to 43% among Dominicans who were born in the Dominican

Republic. (See gure 6.)

Figure 6

Preference for a Particular Brand of Vaccine

By sex, age, and place of birth

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

8

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Finally, interviewees who were not yet vaccinated but planned to be, were asked whether they would

accept a vaccine other than their preferred option or wait to receive the vaccine of their choice. Responses

showed that it was more important for people of Dominican descent to be vaccinated against COVID-19

than wait to receive a vaccine of preference: 59.03% would accept a vaccine if the vaccine of their preference

was unavailable, while only 35.23% indicated that they would delay vaccination until their brand of choice

became available (see gure 7).

Figure 7

If Preferred COVID-19 Vaccine is Not Available,

Would Accept Another or Would Wait for Preferred Brand

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

9

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Reasons for Vaccination

Vaccinated respondents and those who planned to get vaccinated were asked about what motivated them

to get vaccinated. A desire to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus was the primary reason behind an

overwhelming majority of respondents’ decision to be vaccinated. Social responsibility, or a desire to protect others,

followed as the second reason encouraging respondents to get vaccinated. Conversely, only 2.7% of vaccinated

respondents surveyed reported that they decided to be vaccinated because they felt pressured. (See gure 8).

Figure 8

Most Important Reason for Vaccinating or Planning to Vaccinate Against COVID-19

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

When stratifying these data by the state, we found that more than 70% of respondents from each of the

states except Massachusetts and Rhode Island decided to be vaccinated or planned to be in order to protect

oneself from COVID-19. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, 53.66% and 67.73% respectively reported

vaccinating to protect oneself.

Social responsibility was the second most common reason motivating respondents to get vaccinated,

with the highest values in Massachusetts (44.41%) and Rhode Island (32.27%) and values between 13.92%

and 20.02% in the other states. Interestingly, being forced, operationalized in this study as “social pressure,”

emerged as the reason least mentioned by respondents, registering values lower than the other two reasons

across all states considered for this study, as it is shown in table 2.

10

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Table 2

e most important reason for getting vaccinated,

by state

States

To protect

myself

Social responsibility

Because of

social pressure

None of these

reasons

Total

New York

75.91 20.02 2.15 1.93 100.00

New Jersey

75.31 19.40 4.11 1.18 100.00

Massachusetts

53.66 44.41 1.93 - 100.00

Florida

78.69 18.47 1.68 1.16 100.00

Pennsylvania

77.56 13.92 3.53 4.99 100.00

Rhode Island

67.73 32.27 - - 100.00

Connecticut 71.98 18.17 9.85 - 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Accessing Vaccination Places

Nearly three quarters of vaccinated interviewees (72.65%) reported that it took them 30 minutes or less to

reach the vaccination site from their place of residence or from their place of employment. Moreover, 22.29%

commuted 30 minutes to an hour to their selected vaccination facility, and only 5.06% reported taking more

than an hour, as shown in gure 9.

Figure 9

Amount of Time to Access Vaccination Places

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

11

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

ese responses were similar for women and men (71% and 74%, respectively, reporting travelling 30

minutes or less to be vaccinated), but there were dierences by age group. Younger people (18-29 years and

30-39 years) reported traveling more than 30 minutes to be vaccinated at a greater frequency than older people

(40-49 years and 50 years and older). ere were also dierences by place of birth. Respondents born in the

U.S. were less likely than respondents born in the Dominican Republic to report travelling 30 minutes or less

to their vaccination site (68% and 75%, respectively). See gure 10.

Figure 10

Distance to Access the Place of Vaccination

by Sex, Age, and Country of Births

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Mitigation Strategies for Combating the Spread of COVID-19

e warning voice issued in the city of Geneva by the general director of the World Health Organization

(WHO), Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, on March 11th, 2020, was merely the trigger for the new social

norm that would bring a set of rules for people’s behaviors inside and outside their homes. e use of facemasks,

keeping physical distance, and frequently washing one’s hands have been recommended as mitigation strategies

to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In many public places, people were required to wear face coverings and

keep 6 feet apart. ese behaviors have become socially normative, signaling a coded message that, in addition

to addressing health concerns, it also reected care, responsibility, and respect for others. ose who decided not

to follow the recommended behavior in public spaces were ostracized, faced a discriminatory and judgmental

attitude against them which sometimes resulted in confrontations between those who adhered to the norm and

those who violated it (Marks 2021).

12

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

us, as shown in gure 11, our study collected data from respondents on how often they wore masks during

their indoor activities outside their homes, such as visits to grocery stores, hairdressers or beauty salons, on while

on public transport, at church, at work or in other shared spaces during the most severe months of the pandemic.

Findings from this study show that an overwhelming proportion of Dominicans followed the directives to wear

masks in recommended places and few did not obey the recommendation suggested by the CDC. A solid 79.12% of

respondents reported that they always or almost always wore masks in selected indoor places, 17.09% said they used

it sometimes or rarely, while only a small proportion (2.78%) reported “never” using masks in designated spaces.

Figure 11

Wearing Masks in Indoor Public Places

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Stratifying these data by state reveals that New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York and Florida recorded the

highest percentage of respondents who wore masks always or almost always when performing indoor activities

(85.67%, 84.96%, 82.01% and 74.92% respectively), while Rhode Island, Connecticut and Pennsylvania

reported the lowest percentage of respondents who wear face covering in designated spaces (49.43%, 52.45%,

and 64.12%, respectively), as shown in table 3.

Table 3

Wearing Masks Indoor Public Places

by State

States

Always or

almost always

Sometimes Rarely Never

Not

responding

Total

New York 82.01 10.11 3.64 2.51 1.73 100.00

New Jersey 85.67 9.88 1.80 1.91 0.74 100.00

Massachusetts 84.96 15.04 - - - 100.00

Florida 74.92 17.42 2.75 4.49 0.41 100.00

Pennsylvania 64.12 22.39 8.36 5.13 - 100.00

Rhode Island 49.43 28.15 22.42 - - 100.00

Connecticut 52.45 12.60 31.88 3.07 - 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

13

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

It is worth noting that most respondents continued to cover their face even after restrictions were eased. Table

6 shows responses to whether respondents continued to wear masks at the time of the survey. Patterns were similar

to those reported during the height of the pandemic, with those in New Jersey (78.86%), New York (78.23%),

Massachusetts (74.94%) and Florida (70.23%) reporting the highest proportions and those in Connecticut

(66.27%), Pennsylvania (54.94%) and Rhode Island (49.43%) reporting lower proportions (see table 4).

Table 4

Wearing Masks Indoor Spaces at the Time of the Survey

by State

States

Always or

almost always

Sometimes Rarely Never

Not

responding

Total

New York

78.23 11.48 5.46 3.46 1.60 100.00

New Jersey

78.86 12.99 6.42 1.773 - 100.00

Massachusetts

74.94 23.21 1.85 - - 100.00

Florida

70.23 18.46 7.35 3.58 0.38 100.00

Pennsylvania

54.94 23.43 15.21 3.54 2.88 100.00

Rhode Island

49.43 28.15 22.42 - - 100.00

Connecticut 66.27 9.82 17.40 3.44 3.07 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Stress and the Pandemic

Respondents were asked a series of questions that allowed us to ascertain how often Dominicans reported:

a) feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge, b) not being able to stop or control worrying c) having little interest

or pleasure in doing things, and d) feeling down, depressed or hopeless. ese results are presented in tables

5, 6, 7, and 8.

Overall, about half of the surveyed population in each state endorsed experiencing each of these

symptoms at some time during the week before the interview. We highlight below the proportion of the

samples that did not experience each symptom, despite the pandemic, and the variation in these symptoms

across the seven states.

Looking at the proportion of respondent who reported that they did not experience a feeling of nervousness

during the week prior to the interview, there was notable variation across the states. In Connecticut, 64.91%

reported not feeling nervous while in Rhode Island, only 20.46% of respondents reported this. Conversely,

between 3.18% and 22.07% reported feeling nervous almost every day during the week prior to been

interviewed, as indicated in table 5.

14

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Table 5

Feeling Nervous, Anxious or on Edge

Last Seven Days Before the Interview

by State

States Not at all Some days More than half

Almost

every day

Total

New York

47.10 25.90 12.13 14.87 100.00

New Jersey

53.96 20.01 11.43 14.60 100.00

Massachusetts

46.67 26.07 24.07 3.18 100.00

Florida

42.87 27.30 16.98 12.86 100.00

Pennsylvania

43.85 30.63 13.62 11.90 100.00

Rhode Island

20.46 27.65 37.56 14.33 100.00

Connecticut 64.91 13.03 - 22.07 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Table 6 shows that, across the seven states, between 34.79% and 65.97% of respondents did not experience

worry during the seven days prior to the interview. Again, respondents from Connecticut had the largest

proportion reporting that they did not worry at all the week prior to been interviewed.

Table 6

Unable to Stop or Control Worrying the Last Seven Days Before the Interview

by State

States Not at all

Some

days

More than half

Almost

every day

Total

New York

52.49 17.34 15.78 14.38 100.00

New Jersey

52.17 25.76 7.49 14.59 100.00

Massachusetts

39.96 21.99 19.76 18.29 100.00

Florida

49.59 23.19 12.82 14.40 100.00

Pennsylvania

35.17 13.31 36.61 14.91 100.00

Rhode Island

34.79 8.84 14.33 42.05 100.00

Connecticut 65.97 10.17 - 23.86 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Conversely, between 14.38% and 42.05% reported being unable to stop worrying almost every day the

week prior to the interview. Again, Rhode Island had the largest proportion of respondents who said that they

were worrying almost every day the week prior to the survey.

e patterns reported above were also found when examining whether respondents felt interest or pleasure

in performing daily life activities. at is, between 29.30% and 71.33% did not have little interest or pleasure,

with Connecticut being the state with the largest proportion lacking this sign of depression. Between 2.19%

and 21.92% reported having little interest or pleasure in carrying out daily life tasks, with Rhode Island having

the largest proportion reporting this outcome (27.65%, see table 7).

15

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Table 7

Little Interest or Pleasure in Doing ings

During the Last Seven Days Before the Interview

by State

States Not at all Some days More than half

Almost

every day

Total

New York

52.45 19.41 11.46 16.68 100.00

New Jersey

51.96 22.60 11.99 13.45 100.00

Massachusetts

38.81 23.66 15.61 21.92 100.00

Florida

51.83 20.15 15.94 12.08 100.00

Pennsylvania

36.64 25.47 21.90 15.99 100.00

Rhode Island

29.30 43.05 - 27.65 100.00

Connecticut 71.33 14.96 11.52 2.19 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Table 8 shows similar ndings for feelings of depression or hopelessness. Future studies should investigate

further these feelings as they may have existed prior to the pandemic.

Table 8

Feeling Down, Depressed or Hopeless

During the Last Seven Days Before the Interview

by State

States

Not at all Some days More than half

Almost

every day

Total

New York

52.63 21.71 12.62 13.04 100.00

New Jersey

57.75 15.10 14.90 12.25 100.00

Massachusetts

50.63 14.74 20.68 13.95 100.00

Florida

51.59 25.14 13.88 9.38 100.00

Pennsylvania

41.57 27.52 14.39 16.53 100.00

Rhode Island

34.79 20.13 31.26 13.82 100.00

Connecticut

64.33 19.80

11.88 3.98 100.00

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

e next section addresses the question of how interviewees obtained information about COVID-19, a

topic that generated much discussion given that prominent politicians and spokespeople did not agree on the

validity of the information regarding COVID-19.

16

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

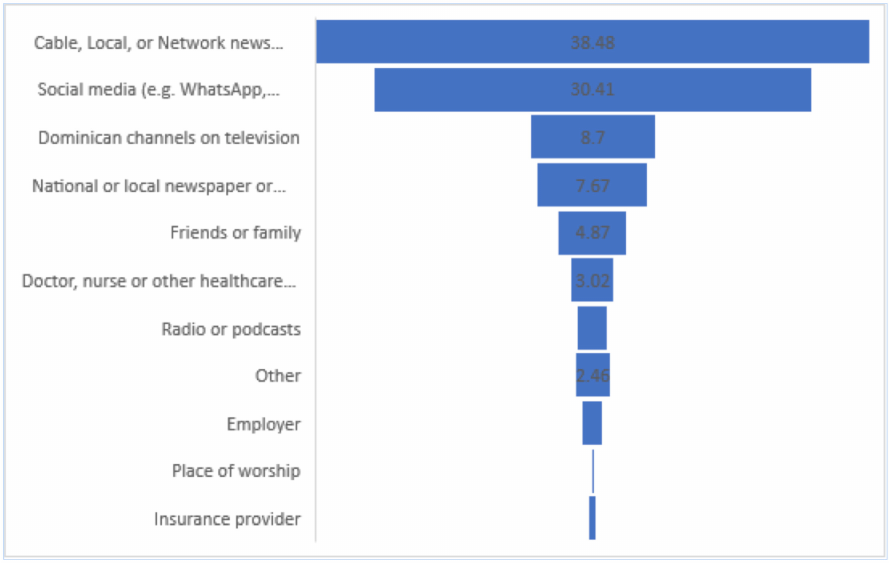

Main Sources of Information on COVID-19

Respondents were asked to identify the main sources they used to inform themselves about COVID-19

during the two weeks before the interview. e Internet was the most common source (38.48%), followed by

virtual social networks, such as Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, WhatsApp, YouTube, and Snapchat

(30.41%). In contrast, less than 8.7% of respondents said that they obtained information about COVID-19

primarily through Dominican television channels, and 3.2% obtained information from doctors and nurses.

See gure 12.

Figure 12

Main Source of Information About COVID-19

Last Two Weeks

by State

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Stratifying these data by state, revealed similar ndings in each state. Between 31.46% and 40.27% of

respondents from six states reported receiving information about COVID-19 mainly via the Internet. However,

in Rhode Island only 23.12% choose the Internet as main source of information for COVID-19 (see table 9).

Table 9 shows that between 17.47% and 51.56% of respondents in each state obtained information about

COVID-19 through virtual social networks, with Rhode Island having the lowest and Connecticut having the

highest proportion. In Rhode Island, each of the sources - internet, social media, television, and local newspapers-

were equally likely to be selected. In the other states, where the Internet and social media outlets were substantially

more likely to have been selected, traditional news communication outlets had an anemic representation.

17

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Table 9

Main Source of information about COVID-19 in Last 2 Weeks

by States

States

Internet, news

on the web

Social Media

Dominican

TV Channels

local

newspapers

Radio

New York

40.00 30.12 8.74 8.79 1.98

New Jersey

36.27 31.92 1.46 1.46 2.09

Massachusetts

36.03 39.78 7.79 7.79 -

Florida

40.27 26.30 9.61 9.61 1.95

Pennsylvania

37.28 25.06 9.53 9.53 4.94

Rhode Island

23.12 17.47 17.43 17.43 13.82

Connecticut 31.46 51.56 8.74 8.74 -

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

Table 10 shows the fall of traditional news media in contrast to the relevance acquired by the Internet

and virtual social networks as sources of information preferred by the people interviewed. Stakeholders who

were once decisive in the construction and dissemination of information that was perceived as accurate and

eective, are progressively disappearing from the public scene. Among the displaced we found professionals

who enjoyed high prestige in society, such as doctors and nurses, and employers in the workplace, among

others. is is illustrated in table 10.

Table 10

Main Source of information about COVID-19 in Last 2 Weeks

by States

States

Doctors &

nurses

Health

Insurance

Employer

Friends Other

New York

2.20 0.39 0.97 3.31 3.4

New Jersey

4.50 1.13 0.82 7.46 2.74

Massachusetts

- - 2.98 1.65 -

Florida

4.02 0.45 - 7.01 2.37

Pennsylvania

6.42 2.20 6.56 6.42 1.58

Rhode Island

- - 13.82 - -

Connecticut - - 3.44 3.07 -

Source: CUNY DSI & CUNY School of Medicine, COVID-19 Survey 2021.

18

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

is study shows that though the presence of the Internet and virtual networks are growing aggressively

among Dominicans, in general, traditional means of communication still remain competitive among

Dominicans in general, but in some regions more than others, and among some segments of the population, at

least as far as information related to the pandemic is concerned.

Finally, the radio station that, since its creation, became one of the main sources of information and molder

of public opinion, today tend to occupy a negligible place in society as a vehicle for disseminating information.

It is worth noticing that it is in the state of Rhode Island that radio has a higher representation (13.82%),

relative to the other states, among respondents.

Conclusion & Policy Recommendation

In conclusion, this study illustrates that people of Dominican descent in the U.S. had a high rate of

compliance with vaccination and other public health recommendations related to the pandemic. In fact, almost

8 in 10 respondents had been vaccinated by the second week of November 2021, and more than 9 in 10 of those

vaccinated had received both doses by this time. Similarly, most respondents were able to vaccinate in their state

of residence and very close to their homes or place of work, and vaccinated out of personal and social concern,

not because of coercion. Public health campaigns should consider this information when addressing health

crises in this population in the future.

It is also clear that not all Dominicans trust the same mediums of communication. While older Dominicans

still preferred traditional means of communication to get information about COVID-19, younger Dominicans

obtained this news mostly from social media outlets. is is to say, that policy makers should design strategies

of communication that are not just language based but also generational.

A substantial number of respondents showed symptoms of stress, anxiety, or depression, with these outcomes

varying signicantly by state. In the states of Massachusetts and New Jersey, for instance, approximately 15%

felt depressed or hopeless a few days of the week prior to the week of the interview, this percentage jumped to

27% in the state of Pennsylvania. A limitation of this data is that we cannot determine if these ndings are

unique to the Dominican population in these states, or whether Dominicans felt this way before the COVID-19

pandemic. It is also possible that other factors unrelated to the pandemic were causing these feelings. ese are

questions that the present study did not investigate. Yet, it would be important to better understand the reasons

for the high incidence and the variation among the states in order to develop appropriate community-level

interventions that target these issues within the Dominican population.

is study also shows that Dominican immigrants are likely to follow the protocols in place to mitigate

the propagation of the virus in higher proportion than U.S.-born Dominicans. Future studies should consider

nativity status and perhaps length of time in the U.S., important variables that may help shed light not only on

the group’s behavior but also on structural dierentiations within the group.

Acknowledgments

is study has benetted from the expertise and advisory of Dr. Rafael A. Lantigua, Professor of Medicine

at Columbia University Medical Center and Associate Dean for Community Services Programs at the Vagelos

College of Physicians and Surgeons at the same institution. His long history of active involvement in research

on issues that aect the quality of life in minority populations and especially Dominicans made him an

invaluable asset to this project. We also are indebted to Mariela Pichardo, Research Assistant at CUNY DSI,

for her editorial assistantship.

19

Understanding COVID-19 Among People of Dominican Descent in the U.SA.

R. Hernandez, P. Ortega, N. Sohler & S. Marrara

Works Cited

1. Abbasi, J. (2021). Omicron Has Reached the US—Here’s What Infectious Disease Experts Know

About the Variant. JAMA.. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.22619.

2. Aldridge, R. W., Lewer, D., Katikireddi, S. V., Mathur, R., Pathak, N., Burns, R., Fragaszy, E. B.,

Johnson, A. M., Devakumar, D., Abubakar, I., & Hayward, A. (2020). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic

groups in England are at increased risk of death from COVID-19: indirect standardisation of NHS mortality

data. Wellcome Open Research, 5, 88. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15922.2.

3. Alsan, M., Stantcheva, S., Yang, D., Cutler, D. (2020). Disparities in Coronavirus 2019 Reported

Incidence, Knowledge, and Behavior Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open, 3(6), e2012403. doi:10.1001/

jamanetworkopen.2020.12403.

4. Chinni, D. (2020, April 12). Coronavirus risk for African Americans tied

to more than race. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/meet-the-press/

coronavirus-risk-african-americans-tied-more-race-n1182146.

5. COVID Collaborative. (2020). Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy in Black and Latinx

Communities. https://www.covidcollaborative.us/content/vaccinetreatments/

coronavirus-vaccine-hesitancy-in-black-and-latinx-communities.

6. Creech, C.B., Walker, S.C., & Samuels, R.J. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines. JAMA, 325(13),1318–

1320. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.3199.

7. Despres, C. (2021) Update: Coronavirus Cases Rates and Death Rates

for Latinos in the United States. Salud America. https://salud-america.org/

coronavirus-case-rates-and-death-rates-for-latinos-in-the-united-states/.

8. Feldman, J. M., & Bassett, M. T. (2021). Variation in COVID-19 Mortality in the US by Race

and Ethnicity and Educational Attainment. JAMA Network Open, 4(11), e2135967. https://doi.org/10.1001/

jamanetworkopen.2021.35967.

9. Ford, T., Reber, S., & Reeves, R. (2020). Race Gaps in COVID-19 Deaths Are Even

Bigger than ey Appear. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/16/

race-gaps-in-covid-19-deaths-are-even-bigger-than-they-appear/.

10. Garg, S., Kim, L., Whitaker, M., O’Halloran, A., Cummings, C., Holstein, R., Prill, M., Chai,

S. J., Kirley, P. D., Alden, N.B., Kawasaki, B., Yousey-Hindes, K., Niccolai, L., Anderson, E. J., Openo,

K. P., Weigel, A., Monroe, M. L., Ryan, P., Henderson, J., … Fry, A. (2020). Hospitalization rates and

characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-conrmed coronavirus disease 2019: COVID-NET,

14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. , 69(15), 458-464. doi:10.15585/mmwr.

mm6915e3PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref.

11. Gupta, S. (2020, April 10). Why African Americans may be especially

vulnerable to COVID-19. ScienceNews. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/

coronavirus-why-african-americans-vulnerable-covid-19-health-race.

20

CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

12. Hamel, Liz, Lopes, L., Sparks, G., Kirzinger, A., Kearney, A., Stokes, M., & Brodie, M. (2021). KFF

COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: September 2021. KFF. https://www.k.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-nding/

k-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-september-2021/.

13. Holtgrave, D. R., Barranco, M. A., Tesoriero, J. M., Blog, D. S., & Rosenberg, E. S. (2020).

Assessing racial and ethnic disparities using a COVID-19 outcomes continuum for New York State. Annals of

Epidemiology, 48, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.06.010.

14. Jones, J., Sullivan, P. S., Sanchez, T. H., Guest, J. L., Hall, E. W., Luisi, N., Zlotorzynska, M.,

Wilde, G., Bradley, H., & Siegler, A. J. (2020). Similarities and Dierences in COVID-19 Awareness,

Concern, and Symptoms by Race and Ethnicity in the United States: Cross-Sectional Survey. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e20001. https://doi.org/10.2196/20001.

15. Leon, B. (2021, October 5). U.S. News. Medical Mistrust Fuels Vaccine Hesitancy

Among Hispanics. https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2021-10-05/

medical-mistrust-fuels-vaccine-hesitancy-among-hispanics.

16. Maqbool, A. (2020, April 11). Coronavirus: why has the virus hit African Americans so hard? BBC

News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52245690.

17. Kahn, B., Brown, L., Foege, W., & Gayle, H. (2.). (2020). Framework for Equitable Allocation of

COVID-19 Vaccine. National Academies Press.

18. NYU Furman Center. (2020). COVID-19 Cases in New York City, a

Neighborhood-Level Analysis. e Stoop. https://furmancenter.org/thestoop/entry/

covid-19-cases-in-new-york-city-aneighborhood-level-analysis.

19. Preidt, R. (2021, October 5). Many Latinos are hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine. NPR. https://

www.npr.org/2021/02/01/962905232/many-latinos-are-hesitant-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine.

20. Sheils M, Haque, A. T., Haozous, E. A., Albert, P. S., Almeida, J. S., García-Closas, M., Nápoles,

A. M., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Freedman, N. D., & Berrington de González, A. (2021). Racial and Ethnic

Disparities in Excess Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic, March to December 2020. Annals of Internal

Medicine 2021. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2134.

21. Singh, M., & Koran, M. (2020, April 18). e Virus Doesn't Discriminate but Governments Do':

Latinos Disproportionately Hit by Coronavirus. e Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/

apr/18/the-virus-doesnt-discriminate-butgovernments-do-latinos-disproportionately-hit-by-coronavirus.

22. ebault, R., Ba Tran, A, & Williams, V. (2020, April 7). e coronavirus is infecting and

killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/

nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-

shows/?arc404=true.

23. Tregoning, J.S., Flight, K.E., Higham, S.L., Wang, Z., & Pierce, B. F. (2021). Progress of the

COVID-19 vaccine eort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus ecacy, eectiveness and escape. Nat Rev

Immunol 21, 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00592-.

24. Wan, William. (2020, November 23). Coronavirus Vaccines Face Trust Gap in Black and Latino

Communities, Study Finds. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/11/23/

covid-vaccine-hesitancy/.