Page 1 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

During economic downturns, the federal government can use tax and spending

policies to support economic growth and limit the detrimental effects on

individuals and families. The federal budget contains mechanisms—known as

automatic stabilizers— that alter tax and spending levels in response to changes

in economic conditions without direct intervention by policymakers. For example,

in an economic downturn—when incomes and the employment level fall—tax

liabilities may decrease, and more people may become eligible for certain

government benefits, such as unemployment insurance and food assistance.

Conversely, when incomes and the employment level rise, tax liabilities may rise,

and fewer people may be eligible for government benefits.

Given the key role that automatic stabilizers can play in supporting the economy

and the well-being of individuals and families, it is important to understand how

effectively they are operating.

It is also important to understand their impact on

the broader federal budget. We have previously reported that the federal

government faces an unsustainable long-term fiscal future. Debt held by the

public is projected to exceed its historical high of 106 percent of gross domestic

product (GDP) within the next 10 years. Well-designed automatic stabilizers

could help the federal government balance the short-term need to promote

growth during an economic downturn with longer term concerns about fiscal

sustainability.

You asked us to review several issues related to automatic stabilizers. This

report examines the effects of automatic stabilizers on the economy, the well-

being of individuals and families, and the federal government’s fiscal condition,

based on an extensive review of academic and government literature.

• Studies we reviewed showed that automatic stabilizers reduced the

detrimental effects of recent economic downturns. They prevented the

economy from getting worse by generating additional economic activity.

• Studies showed that during economic downturns, programs with an automatic

stabilizer component had various positive effects on the well-being of

individuals and families, such as alleviating poverty and supporting positive

health outcomes including improved nutrition and healthy birth weights.

However, it is difficult to isolate the effects of automatic stabilizers, because

studies frequently did not separately analyze the automatic portions of these

programs and discretionary changes made by policymakers to address

economic downturns.

• Automatic stabilizers contributed to federal deficits in the wake of recent

economic downturns, according to Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

analysis. However, they are not the key driver of debt over the long-term.

U.S. Government Accountability Office

Economic Downturns

: Effects of Automatic

Spending Programs

and Taxes

GAO

-24-106056

Report to Congressional

Requesters

November

16, 2023

Why This Matters

Key Takeaways

Page 2 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Automatic stabilizers can be taxes or spending programs that automatically

adjust based on economic conditions. Figure 1 provides examples of how tax

provisions and spending programs work as automatic stabilizers and affect the

economy.

Figure 1: Effects of Automatic Stabilizers during Economic Downturns

In general, the economy goes through alternating periods of upswings—or

expansions—and downturns—or contractions. This pattern is commonly referred

to as the business cycle.

1

A recession is a specific type of economic downturn.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) defines a recession as a

significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and

that lasts more than a few months.

2

According to NBER, while all criteria need to

be met to some degree, extreme conditions in any one criterion may offset

another. For example, in the case of the most recent recession in March and

April 2020, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, NBER concluded that the drop in

economic activity had been so great and so widely diffused that the downturn

should be classified as a recession despite its brevity. NBER defines an

economic expansion as occurring after the economy reaches its lowest point and

economic activity begins to increase.

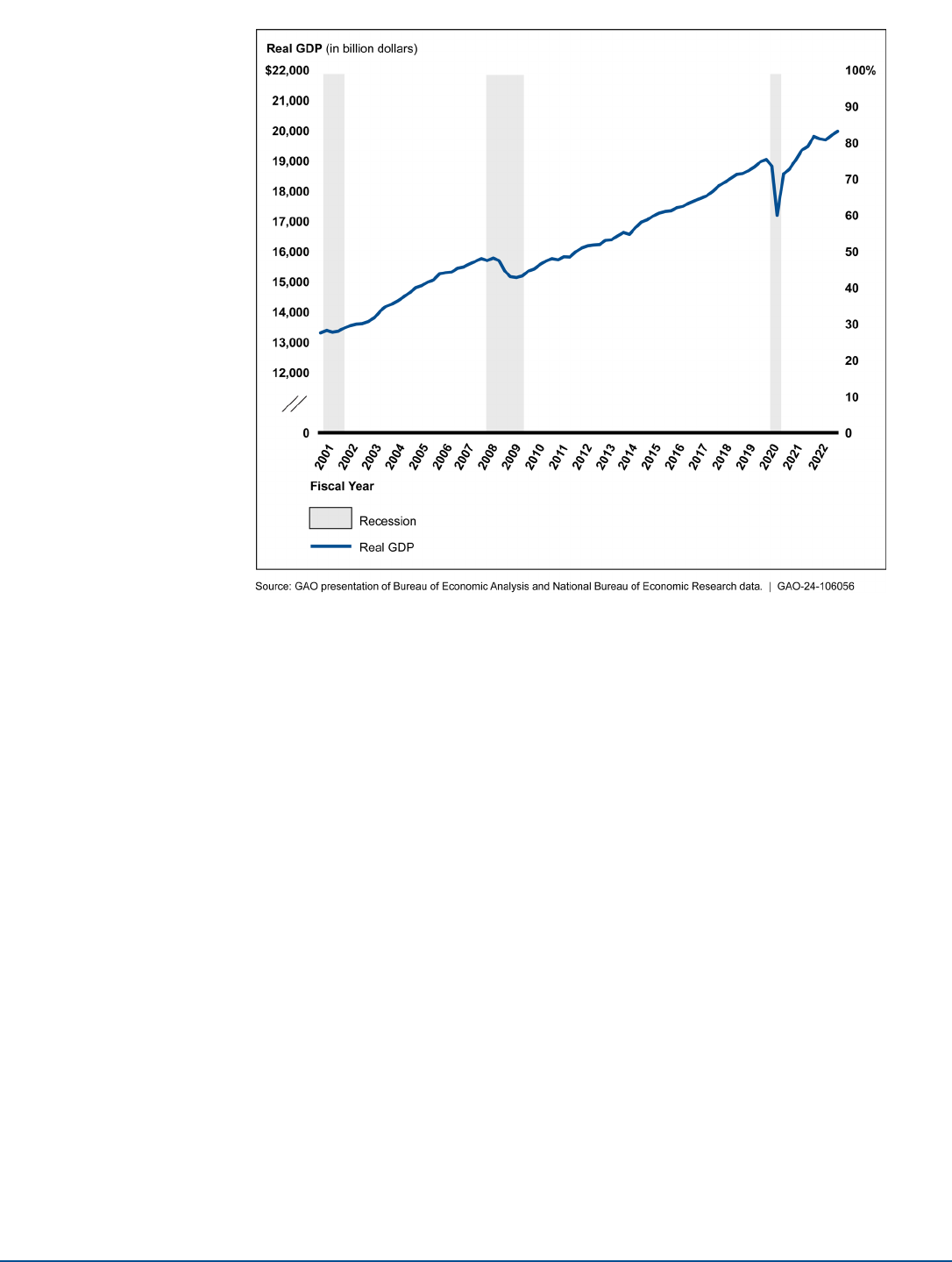

Since 2000, the U.S. economy has experienced three recessions. Figure 2

shows changes in GDP since 2001, as well as the dates of recessions as

determined by NBER. After a recession officially ends, it may take time for the

economy to return to its pre-recession level of activity. For example, after the

Great Recession ended in June 2009, the economy, as measured by GDP, did

not return to its pre-recession level until late 2010.

How do automatic

stabilizers

work?

When is an economic

downturn categorized

as a recession?

Page 3 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Figure 2: Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Fiscal Years 2001–2022

The effects of a recession on unemployment and wages can also extend beyond

the official recession dates as determined by NBER. For example, the

unemployment rate continued to increase for 5 months after NBER determined

the 2001 recession had ended, as shown in figure 3.

Page 4 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Figure 3: Seasonally Adjusted Unemployment Rate, Fiscal Year 2001–2022

a

Seasonal adjustment removes seasonal patterns to compare data across months. Monthly unemployment is

generally reported as seasonally adjusted data.

The federal government has two broad sets of tools that it can use to mitigate the

effects of economic downturns and promote growth.

• Monetary policy, such as lowering interest rates, can encourage economic

activity. Monetary policy is directed by the Federal Reserve and includes

policies that affect the money supply, interest rates, and credit availability.

• Fiscal policy, such as increasing government spending, lowering tax

revenue, or some combination of both, can also encourage economic activity.

In addition to automatic stabilizers, Congress and the President can make

temporary changes to taxes or spending programs—referred to as

discretionary fiscal policy. For example, the federal government provided over

$4.6 trillion in response to COVID-19, including for programs aimed at

addressing the rapid and severe economic downturn caused by the

pandemic.

Figure 4 summarizes how these tools are used to promote growth during

economic downturns.

What tools does the

federal government

have to respond to

economic downturns?

Page 5 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Figure 4: Tools to Counter Economic Downturns

The relative effectiveness of automatic stabilizers in promoting economic growth

depends, in part, on prevailing interest rates in the economy. During economic

downturns, the Federal Reserve can take actions to lower the federal funds rate,

which influences other interest rates in the economy, thereby promoting lending

and economic growth.

3

During the Great Recession and the onset of the COVID-

19 pandemic, the federal funds rate was consistently near zero.

This limited the

Federal Reserve’s ability to use one of its key monetary policy tools to lower

interest rates to promote growth. In such cases, fiscal policy, including automatic

stabilizers, tends to have a comparatively larger impact on economic activity.

Studies we reviewed noted that automatic stabilizers likely played an especially

important role in supporting the economy during periods where the federal funds

rate was consistently near zero, such as during the Great Recession and the

COVID-19 pandemic recession.

4

Once the economy begins to recover,

policymakers may choose to increase interest rates, decrease spending, or

increase tax revenue to prevent the economy from growing too quickly and

causing inflation.

Automatic Tax-Related Functions in Economic Downturns

•

Individual income tax: As taxpayers’ income declines, they owe

less in taxes. Additionally, the tax rates applied to their income

can drop due to the progressive tax rate structure, further

lowering the amount they owe.

•

Payroll tax: As employment and wages fall, workers and

employers pay less in payroll taxes.

• Corporate income tax: As profits decrease, corporations owe less

taxes.

• Production and import taxes: As consumption of goods declines, production and import taxes may

decrease.

Source: GAO analysis of Congressional Budget Office, Congressional Research Service, and Internal Revenue Service information (text); Michael

Flippo/stock.adobe.com (photo). | GAO-24-106056

Multiple taxes act as automatic stabilizers by lowering taxes when incomes fall

and raising taxes when incomes rise. According to CBO, the major types of taxes

that act as automatic stabilizers are (1) individual income tax, (2) payroll taxes

(taxes that pay for Medicare, Social Security, and unemployment insurance), (3)

corporate income tax, and (4) taxes on production and imports. CBO data shows

that these taxes account for nearly all federal revenue.

What are the main tax-

related automatic

stabilizers?

Page 6 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

The individual income tax is the largest automatic stabilizer in the federal budget.

The U.S. has a generally progressive rate structure for its income tax, meaning

that it applies lower tax rates at lower income levels and higher tax rates at

higher income levels. Progressive income tax systems, which have higher tax

rates for higher levels of income, act as automatic stabilizers because they

moderate fluctuations in after-tax income. When a taxpayer’s income declines in

an economic downturn, the top tax rate applied to their income may be reduced.

As a result, they experience less change to after-tax income, which reduces the

effect of income loss on spending.

Social Security and Medicare payroll tax amounts are based on the taxable

earnings of workers. These taxes are paid by employers, employees, and the

self-employed and are generally a percentage of earnings. Unemployment

insurance taxes are paid by employers to states based on worker earnings.

When earnings decline in an economic downturn, the amount of tax paid on

those earnings also declines.

There are three major spending programs in the U.S. that act as automatic

stabilizers, according to CBO analysis:

• Unemployment Insurance (UI),

•

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and

•

Medicaid.

5

Unemployment Insurance

Automatic Unemployment Insurance Functions in

Economic Downturns

•

Enrollment increases as more individuals lose jobs and become

eligible for UI.

•

Eligibility period lengthens when state unemployment rate meets

the trigger for Extended Benefits.

Source: GAO analysis of Congressional Research Service and Department of Labor information (text); Lane Erickson/stock.adobe.com (photo). |

GAO-24-106056

UI is a joint federal-state program that provides temporary financial assistance to

eligible workers who have become unemployed through no fault of their own. UI

benefits are funded primarily through taxes that states levy on employers.

According to the Department of Labor, UI program administration is financed

through a federal tax on employers, and the benefits replace a portion of a

claimant’s previous employment earnings.

6

UI use surged at the onset of the

COVID-19 pandemic, as initial UI claims rose nearly 3,000 percent from about

200,000 per week to more than 6 million per week during late-March and early-

April 2020.

7

The UI program also includes an Extended Benefits program where states

extend unemployment insurance benefits for up to an additional 13 weeks when

their unemployment rates meet a certain threshold.

8

The federal government

funds 50 percent of payments under the Extended Benefits program as part of

normal UI operation. However, federal funding for UI claims and Extended

Benefits can vary depending on temporary changes in law enacted in response

to economic downturns.

9

What are the main

spending

-related

automatic stabilizers?

Page 7 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Automatic Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Functions in Economic Downturns

• Enrollment increases as incomes fall and more people become

eligible and apply for SNAP.

•

Benefits are calibrated to income, so as incomes fall, benefit

amounts can increase (up to maximum threshold).

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture information (text); https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/logo-guidance (image). | GAO-24-106056

SNAP provides food benefits to low-income families to supplement income and

benefits so they can afford nutritious food. The benefit is funded by the federal

government, with administrative costs shared by states.

10

Average participation

in SNAP rose by 16.6 percent during the economic downturn caused by the

COVID-19 pandemic, from 35.7 million for fiscal year 2019 to 41.6 million for

fiscal year 2021.

11

SNAP benefit eligibility and amounts are determined by a

household’s income and assets.

Medicaid

Automatic Medicaid Functions in Economic Downturns

•

Enrollment increases as incomes fall and more people become

eligible.

•

Enrollment may increase as people become unemployed and lose

employer-provided health insurance.

Source: GAO analysis of Congressional Research Service and Health and Human Services information(text); WDnet Studio/stock.adobe.com

(photo). | GAO-24-106056

Medicaid finances health care coverage for millions of low-income and medically

needy people.

12

Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal government and states,

with the federal government matching state expenditures based on a statutory

formula that covers at least half of states’ expenditures. Enrollment for Medicaid

rose by 15.7 percent from before the economic downturn caused by the COVID-

19 pandemic, from nearly 64.1 million in February 2020 to more than 74.1 million,

in the aftermath of this economic downturn, in February 2021.

13

Temporary Changes to Automatic Stabilizer Programs

Discretionary fiscal policy during recent economic downturns included temporary

changes to automatic stabilizer programs.

14

For example, during the Great

Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress and the president made the

following temporary changes:

• UI. Increased benefit amounts, expanded benefits to new groups, and

extended the length of time a person could receive benefits.

15

• Medicaid. Increased federal share of funding. To receive the increased

funding, states and territories were required to meet certain conditions, such

as maintaining Medicaid enrollment during the COVID-19 public health

emergency.

• SNAP. Suspended certain eligibility and state recertification requirements

and increased benefit amounts.

16

Page 8 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Preventing Further Economic Decline

Studies we reviewed found that, overall, automatic stabilizers limited the depth of

economic downturns.

17

• One such study found that between 1970 and 2015, automatic stabilizers

helped smooth fluctuations in economic activity.

18

Specifically, annual GDP

growth would have been 0.82 percentage points lower during recessions

without automatic stabilizers.

19

Conversely, during periods of economic

expansion, annual GDP growth would have been 0.13 percentage points

higher without automatic stabilizers.

20

• Another study found that over 2008–2009, U.S. GDP would have been 0.75

percent lower without automatic stabilizers.

21

• Both studies considered the total effect of automatic stabilizers at the federal,

state, and local levels of government, which exceeds the effect of federal

automatic stabilizers alone. Moreover, their findings are sensitive to

assumptions regarding the spending and saving behavior of households and

businesses affected by automatic stabilizers.

Generated Additional Economic Activity

There is some evidence that automatic stabilizers can generate a larger

economic effect than the amount initially spent—known as a multiplier effect. The

multiplier is the ratio of the resulting economic activity to the change in program

spending. For example, as program enrollees spend SNAP and UI benefits,

additional income is generated for individuals and business involved in the

production and distribution of goods and services. This dynamic can create a

cycle of increased spending in the economy, particularly when the economy is

not operating at full capacity.

One study we reviewed estimated the one-year multiplier of SNAP spending

during economic downturns to be 1.5.

22

In other words, every $1 spent on SNAP

during the year would generate $1.50 in economic activity. Another study—

focused on the Great Recession—estimated a slightly larger SNAP multiplier

early in the recession. The study pointed out that multipliers tend to be larger

when the economy is operating far below its potential.

Other studies we reviewed found UI multipliers between 1 and 1.9.

23

Multiplier

estimates vary, in part, because the studies all relied on different economic

models and assumptions. Moreover, some of the studies made no distinction

between automatic and discretionary SNAP or UI spending and others focused

exclusively on discretionary increases.

The effects of UI on unemployment rates are influenced by multiple factors. For

example, UI benefits can potentially create a disincentive for individuals to seek

employment, which could increase the unemployment rate. However, by

sustaining consumption by households that suffered job loss, UI benefits can

also increase demand for goods and services, thus bolstering economic activity

and reducing the unemployment rate. At the same time, UI tax penalties levied

on employers that have laid off workers in the past can help prevent additional

layoffs. We reviewed a number of studies that measured how changes to UI

benefits affected the unemployment rate during the Great Recession, but we did

not find any focused on the more recent COVID-19 pandemic recession at the

time of our review.

How have automatic

stabilizers affected the

economy during recent

economic downturns?

How has

unemployment

insurance affected

the

un

employment rate?

Page 9 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

UI benefits had mixed but generally limited effects on the unemployment rate,

based on studies that we reviewed. One study used labor market data to

compare adjacent counties in neighboring states and found no evidence that

state-level UI benefit extensions substantially affected employment during the

Great Recession.

24

This study estimated that UI benefit extensions did not

change the county-level employment to population ratio by more than 0.35

percentage points. We also reviewed studies that were more dependent on

assumptions about economic behavior to estimate these effects; the results were

mixed, ranging from reducing unemployment by 0.4 percentage points to

increasing the unemployment rate by 1.4 percentage points.

25

These estimates

vary in part due to differences in the assumptions applied.

Unemployment Insurance Taxes

Employers’ state UI tax rates can vary depending in part on their past

experience laying off workers who subsequently receive UI benefits, commonly

called their experience rating. A higher experience rating leads to higher UI tax

rates.

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO-24-106056

One study found that UI taxes may also affect the unemployment rate.

26

The

study showed that states where firms faced higher UI tax penalties for dismissing

workers saw smaller employment responses to national economic shocks

between 2001 and 2019. The study estimated that, because tax increases

associated with higher experience ratings create a disincentive for firms to lay off

workers, experience ratings prevented an additional rise in unemployment during

the Great Recession.

27

Studies we reviewed found that expansions to UI benefits during the early 2000s

recession and Great Recession, including increases to benefit amounts and

duration, had limited to modest effects on the length of unemployment spells and

could lead to better job matches. For example, studies:

• found that a 10-week extension in UI benefits increased average periods of

unemployment for eligible workers by 1.5 weeks, with little variation between

the Great Recession and the early 2000s recession;

28

• estimated that increasing the UI maximum duration by 20 weeks lead to a

2.5-week increase in unemployment duration;

29

and

• estimated that a 10 percentage point increase in the share of workers’

income replaced by UI benefits increased unemployment duration by 0.5

weeks.

30

Two studies we reviewed developed models that assessed how changes to UI

benefit amounts and duration potentially affect unemployment duration.

31

Namely, as UI generosity (maximum benefit and duration) increases, eligible,

unemployed workers have reduced incentives to search for jobs, which may

increase their duration of unemployment. However, these models rely on a set of

simplifying assumptions that may not completely capture all the impacts of

increased UI generosity. For example, as UI recipients spend benefits and

stimulate the local economy, individuals not eligible for UI may be more likely to

find employment than if UI had not been expanded.

Another study noted that UI extensions that took place from 2000-2013 allowed

individuals to search longer, eventually leading to job matches of better quality.

32

This study’s estimates suggest that UI benefit extensions increased earnings for

workers transitioning out of unemployment. This outcome was especially true for

Do adjustments to

unemployment

insurance

during

economic downturns

affect

individuals’

unemployment

outcomes

?

Page 10 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

workers with less access to credit, who saw an even higher match quality and an

increased probability of staying at their eventual job following reemployment.

These findings are consistent with our June 2022 report, which examined studies

that analyzed the relationship between expanded UI benefits and workers’

incentives to return to work.

33

We found that expanded UI benefits had limited

disincentive effects on workers’ decisions to return to work. Specifically, the

studies we reviewed for that report either found that expanded UI had no

disincentive effects or, if they found some effect, it was limited to a small group of

workers.

Researchers found that UI, SNAP, and other social safety net programs helped

prevent rises in poverty and declines in income during recent economic

downturns.

34

However, these studies typically did not separate discretionary

changes in program benefits from regular benefits. The studies also did not

typically account for behavioral responses from benefit recipients, such as

decisions about spending versus saving or the number of hours worked, in

evaluating what outcomes would have occurred in the absence of these

programs.

35

Social Safety Net. Programs that assist low-income individuals and families with cash

aid, food, shelter, health care, and other supports. While studies we reviewed varied in

the set of programs considered as part of the social safety net, they all included SNAP,

UI, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

Source: GAO analysis of relevant literature. | GAO-24-106056

Alleviated Poverty

Studies we reviewed found that SNAP and UI—both regular benefits and

discretionary changes—helped prevent rises in poverty and helped moderate

income fluctuations during recent recessions.

• SNAP helped the poorest households moderate income fluctuations and,

during the Great Recession, was particularly effective in reducing deep

poverty (an income at or below 50 percent of the poverty line) as well as

poverty among households with children.

36

• UI also helped keep people out of poverty. One study looking at the poverty

rate during the COVID-19 pandemic found this rate declined by 1.5

percentage points between January and June 2020.

37

The study found that,

without regular and expanded UI benefits, poverty would have instead risen

by 0.8 percentage points. Another study found that, across the 2001

recession and the Great Recession, workers who exhausted UI benefits saw

family poverty rates rise substantially and other social safety net programs

only made up for a small fraction of lost UI income.

38

One study we reviewed found that UI replaced earnings during economic

downturns, but the effect varied over time.

39

Specifically, a study found that in

2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, UI payments replaced all the earnings lost

for over half of UI beneficiaries. In comparison, in 2009, amid the Great

Recession, UI payments replaced all the earnings lost for 19 percent of UI

beneficiaries.

40

How have automatic

stabilizer programs

affected income,

poverty, and wealth?

Page 11 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Effects Varied Across Demographic Groups

Studies we reviewed found that the effects of social safety net programs varied

more broadly across demographic groups and income levels.

41

For example,

studies found

• the reduction in household income variability after receiving benefits was the

largest among the following types of families: low-income, female-headed,

Black, and those with less education; and

42

• the social safety net reduced the extent to which income in households with

children changed as the unemployment rate changed.

43

However, the social safety net seemed to have had no mitigating effect on

poverty for children in households with immigrant heads.

44

Sustained Home Values

Studies we reviewed found that more generous UI benefits during the Great

Recession reduced mortgage delinquency and foreclosures.

45

These studies

compared housing market outcomes across states with varying UI generosity.

One study found that longer extended UI duration reduced mortgage delinquent

balances as long as homes had not lost value.

46

Another study found that higher maximum extended UI benefits reduced

mortgage delinquency and foreclosures among displaced workers.

47

Consequently, the expansion of UI benefits during the Great Recession stabilized

the housing market by moderating the decline in home values in areas with rising

unemployment. Specifically, while states with the least generous UI benefits saw

home values decline with rising county-level unemployment rates, this did not

occur in states with the most generous UI benefits.

Automatic stabilizer programs generally limited the rise of food insecurity (lack of

access to enough food for an active, healthy life) during economic downturns but

did not fully address increased need.

48

Studies we reviewed suggested that

SNAP helped protect against food insecurity during the Great Recession and

COVID-19 pandemic.

49

For example, one study estimated that if SNAP were not

available, self-reported food hardship would have increased by as much as 8.4

percentage points during the Great Recession, relative to the observed increase

of 2.6 percentage points.

50

In addition, another study showed that, during the

COVID-19 pandemic, self-reported food insufficiency rates declined following a

discretionary 15 percent increase to SNAP benefits in January 2021.

51

Medicaid expansion—as authorized by the Patient Protection and Affordable

Care Act—was also associated with a reduced risk of food insecurity during the

pandemic.

52

Specifically, one study found that newly unemployed workers in

states that expanded Medicaid were less likely to experience moderate or severe

food insecurity following job loss relative to unemployed workers in states that did

not expand Medicaid.

53

However, it is unclear whether Medicaid expansion

caused lower rates of food insecurity, in part because other social safety net

programs may be present in states that expanded Medicaid.

Social safety net programs did not fully address food insecurity during the

COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in October 2021, following the September

2021 expiration of more generous UI payments, the number of households that

reported not having enough to eat began to rise steadily.

54

One study found three

explanations of why social safety net programs did not fully address food

insecurity and other measures of economic hardship during the pandemic:

55

How have automatic

stabilizer programs

affected food

insecurity?

Page 12 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

• Barriers to early financial relief, such as delays resulting from overwhelmed

state UI systems, slow implementation of discretionary changes in programs

by the states, and application requirements.

56

• The relatively small magnitude of SNAP spending compared to UI spending.

For example, the study identified that UI payments had increased to an

average of $23.5 billion per week from May through July 2020. During the

same time frame, SNAP payments increased to an average of about $1

billion per week.

• Coverage gaps for some groups that were excluded from social safety net

programs, including unemployed workers who did not receive UI.

Provided Health Insurance

Studies consistently found higher rates of health insurance coverage following

job loss in states with expanded or more generous Medicaid benefits.

57

Specifically, studies found

• during the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of increase in the number of people

without health insurance due to job loss was lower in states that expanded

Medicaid (2.9 percent increase in uninsurance) than in states that did not

expand Medicaid (10.7 increase in uninsurance).

58

• during the Great Recession, as unemployment rates increased, individuals in

states with less generous Medicaid eligibility guidelines were more likely to

become uninsured.

59

Comparing insurance outcomes across states may partially reflect systematic

differences across states that are not directly related to Medicaid generosity,

such as state-level differences in the administration of other safety net programs.

Supported Positive Health Outcomes

Studies found more generous Medicaid, UI, and SNAP benefits to be associated

with better health outcomes.

Medicaid. In one study, during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals who recently

lost jobs and lived in states that expanded Medicaid were more likely to be

covered by Medicaid and less likely to suffer from severe mental distress relative

to those living in states that did not expand Medicaid.

60

One study examined the

role of Medicaid in mitigating the association between unemployment and

adverse birth outcomes during the 2001 recession and Great Recession.

61

This

study found that Medicaid generosity reduced the degree to which

unemployment was associated with adverse birth outcomes, and this reduction

was strongest among Black mothers.

62

UI. Another study found that higher discretionary UI generosity was associated

with better birth outcomes, especially among less educated and unmarried

mothers.

63

This study, using data from 1970–2019, estimated that a one standard

deviation increase in benefit caps was associated with a 3.4 percent increase in

average birth weight.

64

A separate study found that when UI replaces a greater

share of recipients’ former income, recipients are more likely to have health

insurance coverage and use health care.

65

During economic downturns, these

effects were stronger and accompanied by improvements in self-reported health

status.

How have automatic

stabilizer programs

affected people’s

health?

Page 13 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

SNAP. Two studies we reviewed explored the benefits of SNAP in improving

health outcomes. In one study, individuals living in states where SNAP was more

generous and easier to access were more likely to be in better overall self-

reported health.

66

Another study summarized a round table discussion of federal,

think tank, and academic researchers.

67

Round table participants discussed

findings from their research that linked SNAP to improved health outcomes, such

as a reduction in childhood obesity, through better nutrition and reduced stress.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

The EITC supplements earnings for low- to moderate-income workers and working

families by providing a tax credit based on earnings from work. The amount of the

credit grows with additional earnings up to a maximum threshold, plateaus, and then

decreases with earnings beyond that threshold. The EITC is neither available for

families that did not earn any income in a given tax year, nor for high-income workers.

Source: GAO analysis of Internal Revenue Service information. | GAO-24-106056

Studies we reviewed found that the EITC has a mixed record as an automatic

stabilizer.

68

Specifically, two studies found that overall, more low-income workers

became eligible for the EITC during economic downturns.

69

However, these

studies also found that certain types of families and individuals, such as highly

educated individuals, were more likely to become eligible for the credit, while

others lost eligibility.

One study used tax and census data from 2005 to 2011 and found that workers

with reduced income from employment may gain eligibility for the credit or qualify

for a larger tax credit than they would have received otherwise.

70

The study also

found that unmarried women with less education were less likely than those with

more education to become eligible due to a decrease in earnings. The study also

found that married taxpayers where one working spouse lost employment could

become eligible. On average, less educated single mothers with children were

more likely to lose employment for an entire tax year and therefore lose eligibility

for the credit.

The other study analyzed state and federal data from 1996 to 2008 and found

that, overall, more taxpayers claim the EITC during economic downturns.

71

This

study found that married taxpayers who may have seen reduced earnings for one

spouse may become eligible for the EITC. The study also found that highly

skilled individual taxpayers with reduced earnings may become eligible for the

EITC during economic downturns.

As with most federal programs, automatic stabilizer programs operate throughout

the business cycle. They represent expenditures in the federal budget even when

the economy is doing well. When the economy is not operating at its full

potential, more people become eligible for UI, SNAP, and Medicaid, and the

government spends more on these programs.

Similarly, federal tax revenues are higher when the economy is operating at its

full potential and lower when it is not. For example, revenues from individual

income taxes dropped 22 percent amid the Great Recession and its aftermath,

from $1.1 trillion in 2008 to $899 billion in 2010.

72

Automatic stabilizers increased the federal budget deficit in all but 5 years

between 2001 and 2022, in amounts ranging from 0.1 to 2.2 percent of GDP (see

fig. 5.) Automatic stabilizers helped increase the budget surplus in 2001 and

reduced the deficit in 2006 and 2007 by amounts ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 percent

To what extent does the

EITC

act as a stabilizer

d

uring economic

downturns

?

How do automatic

stabilize

rs affect the

federal budget

?

Page 14 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

of GDP. In 2005 and 2008, automatic stabilizers did not significantly increase or

decrease the deficit.

CBO projects that automatic stabilizers will continue to increase federal deficits

through 2033, though their effects will be strongest in the first half of that period.

In the second half of that period, CBO projects that economic conditions will

reach their long-run historical average values, which will reduce the effects of

automatic stabilizers on the federal budget deficit.

Figure 5: Contribution of Automatic Stabilizers to the Federal Budget Deficit as a Share of

Potential Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Fiscal Years 2001–2033

The full effect of automatic stabilizers on the federal budget is not known

because the studies we reviewed do not capture all ways in which the economic

changes that result from automatic stabilizers may affect federal spending and

revenues. As noted above, studies find that during economic downturns,

automatic stabilizers support income, employment, and economic output. These

effects can then lead to improved budgetary conditions as revenue increases and

the need for spending is reduced. Therefore, there may be fiscal effects of

automatic stabilizers that have not been precisely measured.

73

While automatic stabilizers have contributed to budget deficits in recent years,

they are not the key driver of federal debt over the long term. In May 2023, we

reported that increasingly large budget deficits were driving unsustainable debt

levels.

74

Large annual budget deficits occur because spending is increasing more

than revenue and the government is spending more on interest to service its

growing debt.

In fiscal year 2022, automatic stabilizers contributed $67 billion to the federal

budget deficit, according to CBO. However, the federal budget deficit was almost

$1.4 trillion that year, the fourth-largest recorded nominal federal deficit in history

To what extent do

automatic stabilizers

contr

ibute to federal

debt over the

long

term

?

Page 15 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

behind the budget deficits in fiscal years 2021, 2020, and 2009, all periods of

economic distress.

The gap between revenue and spending is expected to increase in the coming

years, in large part because of the projected increases in Medicare, other federal

health care, and Social Security program spending, and net interest spending

compared to relatively lower projected increases in revenue.

75

Federal health

care and Social Security spending are rising because the population is aging and

health care is getting more expensive. As a result of these factors, debt held by

the public is expected to exceed its historical high of 106 percent of GDP within

the next 10 years. We have previously suggested that Congress develop a plan

to address the government’s fiscal outlook and promote fiscal sustainability.

76

We provided excerpts of a draft of this report to CBO for review and comment.

CBO staff provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We also provided informational copies of a draft of this report to the Department

of the Treasury and the Office of Management and Budget.

This report examines the effects of automatic stabilizers on the economy, the

well-being of individuals and families, and the federal government’s fiscal

condition.

To describe automatic stabilizers, relevant federal programs, and economic

concepts, we reviewed our prior reports, federal agency information, and CBO

and Congressional Research Service publications.

To identify the economic and well-being effects of automatic stabilizers, we

conducted a literature review, beginning with a literature search for studies that

analyzed the relationship between automatic stabilizer programs and the

economy or well-being. We focused our search on articles that analyzed the

effects of automatic stabilizers during recent economic downturns or intervening

periods of economic growth, from 2001 to 2022.

We also used keyword searches to identify well-being outcomes associated with

key automatic stabilizer programs. Key words included wealth, poverty,

employment, health insurance, hunger, and food security. We searched multiple

databases to identify relevant articles, including Scopus, EconLit, Proquest

Sociology Collection, Proquest SciTech Premium Collection, Proquest Policy File

Index, Proquest Dialog Social SciSearch and the U.S. Department of Commerce

National Technical Reports Library. Our searches identified 319 documents from

peer reviewed journals, government-issued reports, working papers, and

publications from nongovernmental organizations.

We also identified 69 documents based on expert recommendations, searches

for related CBO, Congressional Research Service, and inspector general work;

relevant article citations; and our own prior work. Overall, our literature search

contained 388 documents. To assess the relevance of these documents, a policy

analyst and an economist or methodologist separately reviewed each article to

agree on relevance. We considered articles relevant if the articles (1) described

automatic stabilizers’ effect on the U.S. economy or the well-being of individuals

or families in the U.S., or (2) described how automatic stabilizers have affected

the federal government’s fiscal condition from 2001 through 2020.

To assess methodological quality and determine whether an article was

appropriate to include in the literature review, two economists independently

conducted in-depth reviews. These in-depth reviews entailed an assessment of

each study’s research methodology, including its data quality (when applicable),

research design, and analytic techniques, as well as a summary of each study’s

Agency Comments and

Third

-Party Views

How GAO Did This

Study

Page 16 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

major findings and conclusions. We also assessed the extent to which each

study’s data and methods supported its findings and conclusions. We prioritized

studies based on their methodological soundness and use of empirical data

analysis. We determined that 41 articles were relevant and appropriate for our

analysis. See the bibliography for a full list of relevant articles.

Our report presents findings from the body of knowledge included in these

articles. To the extent that findings from these articles vary, we mention the

differences in our report. All studies have limitations and to varying extents make

assumptions about behaviors and how the economy works. Despite these

limitations, we determined that the studies we included provide reliable

information about the effects of automatic stabilizers.

To describe changes in economic conditions over time and periods of economic

downturn, we reviewed data on the business cycle, GDP, and unemployment

rate. Specifically, we used data from 2001 to 2022 from the National Bureau of

Economic Research, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and Bureau of Labor

Statistics.

To describe the extent to which automatic stabilizers have affected the federal

government’s fiscal condition since 2001, we reviewed data and analysis

published by CBO, reviewed research from the Federal Reserve System, and

spoke with CBO and Federal Reserve System staff.

We assessed the reliability of all sources of data and found them to be

sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2022 to November 2023 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those

standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient,

appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence

obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on

our audit objectives.

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Chairman

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Michael F. Bennet

United States Senate

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this

report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At

that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the

Secretary of the Treasury, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget,

and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on

the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

4800.

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, Congressional Relations,

[email protected], (202) 512-4400.

List of Addressees

GAO Contact

Information

Page 17 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Staff Acknowledgments: Thomas McCabe (Assistant Director), Laurel Plume

(Analyst-in-Charge), Yiwen (Eva) Cheng, Samantha Lalisan, Alec McQuilkin, Ed

Nannenhorn, and Rachel Schultz made key contributions to this report.

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube. Subscribe to our

RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

This work of the United States may include copyrighted material, details at

https://www.gao.gov/copyright.

Page 18 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

This appendix contains credit, copyright, and other source information for figures

in this product when that information was not listed adjacent to the figure.

Aizer, Anna and Claudia Persico, “Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Policy Response

and Child Well-Being.” Recession Remedies: Lessons Learned from the U.S. Economic

Policy Response to COVID-19 (Washington, D.C.: The Hamilton Project and the Hutchins

Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, Brookings Institution, 2022).

Appendix I Additional

Source Information for

Graphics

Bibliography

Page 19 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Benitez, Joseph, “Comparison of Unemployment-Related Health Insurance Coverage

Changes in Medicaid Expansion vs Nonexpansion States During the COVID-19

Pandemic,” JAMA Health Forum, vol. 3 no. 6 (2022).

Benitez, Joseph A., Victoria E. Perez, and Jie Chen. “Did Medicaid Slow Declines in

Access to Health Care During the Great Recession?” Health Services Research, vol. 56

(2021): 655–667.

Benitez, Joseph, Victoria Perez, and Eric Seiber. “Medicaid Access During Economic

Distress: Lessons Learned From the Great Recession.” Medical Care Research and

Review, vol. 78, no. 5 (2021): 490–501.

Bitler, Marianne and Hilary Hoynes. “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the

Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession.” Journal of Labor

Economics, vol. 34, no. 1, pt. 2 (2016): S403–S444.

Bitler, Marianne, Hilary Hoynes, and Elira Kuka. “Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and

the Social Safety Net in the United States.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management,

vol. 36, no. 2 (2017): 358–389.

Bitler, Marianne, Hilary Hoynes, and Elira Kuka. “Do In-Work Credits Serve as a Safety

Net?” The Journal of Human Resources, vol. 52 no. 2, Spring (2017): 319–350.

Bitler, Marianne P., Hilary W. Hoynes, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. “The Social

Safety Net in the Wake of COVID-19.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer

(2020): 119–145.

Blinder, Alan S. and Mark Zandi. The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

(Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 15, 2015).

Boone, Christopher, Arindrajit Dube, Lucas Goodman, and Ethan Kaplan.

“Unemployment Insurance Generosity and Aggregate Employment.” American Economic

Journal: Economic Policy, vol. 13 no. 2 (2021): 58–99.

Canning, Patrick and Brian Stacy. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP) and the Economy: New Estimates of the SNAP Multiplier, Economic Research

Report Number 265. U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, July

2019.

Cashin, David, Jamie Lenney, Byron Lutz, and William Peterman. “Fiscal Policy and

Aggregate Demand in the USA Before, During, and Following the Great Recession.”

International Tax and Public Finance, vol. 25 (2018):1519–1558.

Chalom, René, Fatih Karahan, Kurt Mitman, and Benjamin Pugsley. Liquidity Effects of

Unemployment Insurance Benefit Extensions: Evidence from Consumer Credit Data.

Paper presented at a meeting of the Society for Economic Dynamics, 2019.

Congressional Budget Office. Automatic Stabilizers in the Federal Budget: 2023 to 2033.

Washington, D.C.: 2023.

Davig, Troy and Michael Redmond. Accounting for Changes in the U.S. Budget Deficit.

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Kansas City, M.O.: 2014.

Di Maggio, Marco and Amir Kermani. The Importance of Unemployment Insurance as an

Automatic Stabilizer. Working Paper No. 22625 (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of

Economic Research, Sep. 2016).

Duggan, Mark, Andrew C. Johnston, and Audrey Guo, Experience Rating As An

Automatic Stabilizer. Working paper 30651 (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of

Economic Research, Nov. 2022).

Farooq, Ammar, Adriana D. Kugler, and Umberto Muratori. Do Unemployment Insurance

Benefits Improve Match and Employer Quality? Evidence from Recent U.S. Recessions.

Page 20 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Working Paper 27574, (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of Economic Research, rev.

Apr. 2022).

Follette, Glenn and Byron Lutz. Fiscal Policy in the United States: Automatic Stabilizers,

Discretionary Fiscal Policy Actions, and the Economy. Finance and Economics

Discussion Series No. 43, Federal Reserve Board. Washington, D.C.: 2010.

Hamersma, Sarah, Yilin Hou, Yusun Kim, and Douglas Wolf. “Business Cycles, Medicaid

Generosity, and Birth Outcomes.” Population Research and Policy Review, vol. 37

(2018): 729–749.

Han, Jeehoon, Bruce D. Meyer, and James X. Sullivan. “Income and Poverty in the

COVID-19 Pandemic.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer (2020): 85–118.

Hanson, Kenneth. The Food Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier (FANIoM) Model

and Stimulus Effects of SNAP, Economic Research Report Number 103, U.S.

Department of Agriculture, October 2010.

Hardy, Bradley L. “Income Instability and the Response of the Safety Net.” Contemporary

Economic Policy, vol.35, no.2 (2017): 312–330.

Hsu, Joanne W., David A. Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer. “Unemployment Insurance as a

Housing Market Stabilizer.” American Economic Review, vol. 108 no. 1 (2018): 49–81.

Jones, Maggie R. “The EITC Over the Great Recession: Who Benefited?” National Tax

Journal, vol. 70, no. 4 (2017): 709–736.

Kekre, Rohan. “Unemployment Insurance in Macroeconomic Stabilization.” Review of

Economic Studies, vol. 90 (2023): 2439-2480.

Kuka, Elira. “Quantifying the Benefits of Social Insurance: Unemployment Insurance and

Health.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 102, no. 3 (2020): 490–505.

Larrimore, Jeff, Jacob Mortenson, and David Splinter. “Earnings Shocks and Stabilization

During COVID-19.” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 206 (2022): 1–9.

Mandal, Bidisha, Nilton Porto;,D. Elizabeth Kiss, Soo Hyun Cho, and Lorna Saboe-

Wounded Head. “Health Insurance Coverage during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role

of Medicaid Expansion.” Journal of Consumer Affairs (2022): 1–24.

McKay, Alisdair and Ricardo Reis. “The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S.

Business Cycle.” Econometrica, vol. 84, no. 1 (2016): 141–194.

Meyer, Bruce D. and Derek Wu. “The Poverty Reduction Of Social Security And Means-

Tested Transfers.” ILR Review, vol. 71, no. 5 (2018): 1106–1153.

Miller, Daniel P. and Taryn W. Morrissey. “SNAP Participation and the Health and Health

Care Utilisation of Low-income Adults and Children.” Public Health Nutrition, vol. 24, no.

18 (2021): 6,543–6,554.

Mukhopadhyay, Sankar. “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion on Job Loss Induced Mental

Distress During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US.” SSM – Population Health, vol. 20

(2022): 1–14.

Nakajima, Makoto. “A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit Extensions.”

Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 59 (2012): 686–702.

Noghanibehambari, Hamid and Mahmoud Salari. “The Effect of Unemployment

Insurance on the Safety Net and Infant Health in the USA.” Economic Annals, vol. LXVII,

no. 234 (2022): 7–28.

Pei, Yun and Zoe Xie. “A Quantitative Theory of Time-Consistent Unemployment

Insurance.” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 117 (2021): 848–870.

Page 21 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Pilkauskas, Natasha V., Janet Currie, and Irwin Garfinkel. “The Great Recession, Public

Transfers, and Material Hardship.” Social Service Review, vol. 86 no. 3 (2012): 401–427.

Rothstein, Jesse and Robert G. Valletta. “Scraping by: Income and Program Participation

After the Loss of Extended Unemployment Benefits.” Journal of Policy Analysis and

Management, vol. 36, no. 4 (2017): 880–908.

Russek, Frank and Kim Kowalewski. How CBO Estimates Automatic Stabilizers. Working

Paper 2015-07, Congressional Budget Office. (Washington, D.C.: 2015).

Valletta, Robert G. “Recent Extensions of US Unemployment Benefits: Search

Responses in Alternative Labor Market States.” IZA Journal of Labor Policy, vol. 3, no. 18

(2014): 1–25.

Zedlewski, Sheila, Elaine Waxman, and Craig Gundersen. Round Table on SNAP’s Role

in the Great Recession and Beyond. The Urban Institute, 2012.

1

A business cycle refers to the period where overall economic activity fluctuates between a high

point (peak) and a low point (trough). When the economy begins to rise out of a trough, it marks the

beginning of a new cycle. Business cycles vary in length and magnitude.

2

Recessions are designated by a committee of experts within the NBER, a private nonprofit

research organization that focuses on understanding the U.S. economy. The NBER committee

uses indicators such as employment, personal income, industrial production, and quarterly GDP

growth to calculate monthly data on recessions.

3

The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions lend federal funds

(balances held at Federal Reserve Banks) with each other overnight.

4

Rohan Kekre, “Unemployment Insurance in Macroeconomic Stabilization,” Review of Economic

Studies, vol. 00 (2023): 2; Glenn Follette and Byron Lutz, “Fiscal Policy in the United States:

Automatic Stabilizers, Discretionary Fiscal Policy Actions, and the Economy,” Finance and

Economics Discussion Series No. 43, Federal Reserve Board. (Washington, D.C.: 2010),16;

Alisdair McKay and Ricardo Reis, “The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S. Business Cycle,”

Econometrica, vol. 84, no. 1 (2016): 1.

5

According to CBO officials, CBO considers programs automatic stabilizers for the purposes of its

budget estimates when the level of spending is most affected by the business cycle. Officials said

that CBO excludes programs that are too small to be considered a major program or are not

affected by the business cycle. For the purposes of this report, we limited our analysis to the

spending programs CBO identified as automatic stabilizers. Frank Russek and Kim Kowalewski,

How CBO Estimates Automatic Stabilizers, Congressional Budget Office (Washington, D.C.: Nov.

2015).

6

There are 53 different UI programs operated in the states, the District of Columbia (D.C.), Puerto

Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). UI benefits are based on a percentage of an individual’s

earnings over a recent 52-week period up to a state maximum amount. See Department of Labor

UI Tax Fact Sheet, accessed Oct. 11, 2023; and UI Fact Sheet, accessed June 29, 2023

(https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/aboutui.asp).

7

An initial claim is the first claim filed by a person, and is used to determine eligibility for benefits. A

state UI office reviews each initial claim and either accepts or rejects it, with benefits paid to those

claims that are accepted. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Applying for and

Receiving Unemployment Insurance Benefits during the Coronavirus Pandemic (Washington, D.C.:

Sept. 2021), https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2021/article/applying-for-and-receiving-unemployment-

insurance-benefits-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic.htm

8

All states pay up to 13 weeks of extended benefits if the unemployment rate among those eligible

for UI for a specified 13-week period is at least 5 percent and is 120 percent of the average of the

rates for the same 13-week period in each of the two previous years. States can also choose to pay

an additional 7 weeks of extended benefits if the unemployment rate among those eligible reaches

certain thresholds.

9

For example, the CARES Act temporarily provided an additional $600 benefit that augmented

weekly UI benefits, and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act temporarily provided 100

Endnotes

Page 22 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

percent federally financed Extended Benefits for certain states. Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 2104, 134

Stat. 281, 318 (2020); Pub. L. No. 116-127, § 4105, 134 Stat. 178, 195 (2020).

10

SNAP covers the 50 states, D.C., USVI, and Guam. Also, in lieu of SNAP, Nutrition Assistance

Program (NAP) block grant funding is provided to Puerto Rico, the Commonwealth of the Northern

Marianas Islands, and American Samoa. Additionally, the Food Distribution Program on Indian

Reservations provides, in lieu of SNAP benefits, food commodities to low-income households on

Indian reservations and to Native American families residing in Oklahoma or in designated areas

near Oklahoma.

11

According to NBER, the recession driven by the COVID-19 pandemic took place from March to

April of 2020. Annual data on SNAP are used to compare pre-recession average participation in

2019 to post-recession average participation in 2021. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and

Nutrition Service, SNAP Data Tables National Level Annual Summary on Participation and Costs

(data as of June 9, 2023), accessed July 11, 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-

nutrition-assistance-program-snap

12

Mandatory eligibility for Medicaid is extended to certain groups, such as qualified pregnant

women and children. States can also develop a “medically needy program” for those with

significant health needs who do not meet low-income thresholds. All states, the District of

Columbia, and the U.S. territories participate in Medicaid; however, the federal government’s

financing of Medicaid in the territories is subject to a capped allotment and coverage requirements

vary from those applicable to the states and the District of Columbia.

13

Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, March 2023 Medicaid

and CHIP Enrollment Trends Snapshot, accessed July 5, 2023,

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-

and-chip-enrollment-trend-snapshot/index.html. According to the National Bureau of Economic

Research, the COVID-19 recession took place in March and April of 2020.

14

For the purposes of this report, discretionary fiscal policy refers to actions taken by policymakers

to adjust taxes and spending on a short-term basis in response to emerging issues that affect the

level, composition, and distribution of national income and output. Discretionary fiscal policy may

include actions taken to adjust discretionary spending, mandatory spending (i.e., budget authority

generally provided by laws other than appropriations acts), or revenues. The budget process is a

major vehicle for determining and implementing federal fiscal policy. Discretionary spending refers

to budget authority, outlays, or other budgetary resources that are provided and controlled by

appropriations acts.

15

Temporary changes to UI during the COVID-19 pandemic included (1) Pandemic Unemployment

Assistance, which authorized UI benefits to individuals not otherwise eligible who could not work for

COVID-19 related reasons; (2) Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, which

generally authorized additional weekly benefits; (3) Pandemic Emergency Unemployment

Compensation, which generally authorized additional weeks of UI benefits for those who had

exhausted their regular UI benefits; and (4) the Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation

program, which authorized additional UI benefits for those whose benefits did not account for

significant self-employment income and who thus may have received a lower regular UI benefit

than they would have received had they been eligible for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance.

16

Temporary changes to SNAP during the COVID-19 pandemic included issuing emergency

allotments and allowing the Department of Agriculture to adjust federal requirements for SNAP

related to issuing benefits, reviewing applications, and reporting requirements. Pub. L. No. 116-

127, § 1101(a)-(i), 134 Stat. 178, 179-80 (2020).

17

These studies first estimate the size of automatic stabilizers as the change of government

revenues and expenditures in response to economic shocks. Then, they derive the impact of

stabilizers on economic activity either using a macroeconomic model or by applying estimates of

the marginal propensity to consume of households and businesses to the revenue and expenditure

changes. David Cashin, Jamie Lenney, Byron Lutz, William Peterman, “Fiscal Policy and

Aggregate Demand in the USA Before, During, and Following the Great Recession.” International

Tax and Public Finance, vol. 25 (2018) and Follete and Lutz, “Fiscal Policy in the United States.”

18

Cashin et al., “Fiscal Policy and Aggregate Demand,”1538.

19

The rate of GDP growth may be positive or negative. In particular, GDP growth may be negative

during a recession.

Page 23 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

20

At the federal level, the stabilizers considered in this study include personal (individual) and

corporate income, payroll, production and import taxes, and unemployment insurance taxes on the

revenue side, as well as UI, SNAP, and Medicaid on the expenditure side. At the state and local

level, stabilizers include cyclical responses for personal and corporate income taxes and sales

taxes.

21

At the federal level, the stabilizers considered in this study include personal (individual) and

corporate income taxes, social insurance contributions (such as Social Security and Medicare

payroll taxes), excise taxes, and custom duties on the revenue side, as well as UI, SNAP, and

Medicaid, and federal welfare payments before 1996 on the expenditure side. The authors also

considered federal welfare payments post 1996, which were not cyclically sensitive, as well as

Social Security Old Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance, which had negligible

cyclical effects. At the state and local level, stabilizers include cyclical responses for personal and

corporate income taxes, federal grants for Medicaid and Assistance for Families with Dependent

Children (since replaced by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program), and other

small transfers. Follette and Lutz, “Fiscal Policy in the United States,” 17.

22

Specifically, it found that a $1 billion increase in SNAP spending due to new enrollment during a

downturn would generate $1.5 billion in GDP. This study used a social accounting matrix multiplier

model that relates production input to output. It assumed that new SNAP benefit recipients have the

same spending and saving behavior as the average existing SNAP household. It also assumed that

prices and interest rates are fixed in the one-year horizon and that government spending does not

crowd out private spending, which is less likely during an economic downturn. A related study from

2010 estimated the SNAP multiplier to be 1.79. This study assumed new SNAP recipients’ behavior

to match the observed average instead of marginal propensities to save and consume, which tends

to bias the multiplier estimate upward. Patrick Canning and Brian Stacy, The Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Economy: New Estimates of the SNAP Multiplier,

Economic Research Report Number 265, U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research

Service (Washington, D.C.: July 2019).

23

Marco Di Maggio and Amir Kermani, “The Importance of Unemployment Insurance as an

Automatic Stabilizer,” Working Paper No. 22625 (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of Economic

Research, 2016): 2; Kenneth Hanson, The Food Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier

(FANIoM) Model and Stimulus Effects of SNAP, Economic Research Report Number 103, U.S.

Department of Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 2010), iv; Kekre, “Unemployment Insurance in

Macroeconomic Stabilization,” 24; Alan S. Blinder and Mark Zandi, The Financial Crisis: Lessons

for the Next One, (Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 15, 2015): 18.

24

Christopher Boone, Arindrajit Dube, Lucas Goodman, and Ethan Kaplan. “Unemployment

Insurance Generosity and Aggregate Employment,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy,

vol. 13 no. 2 (2021):60.

25

Kekre, “Unemployment Insurance in Macroeconomic Stabilization,”2439; Yun Pei and Zoe Xie, “A

Quantitative Theory of Time-Consistent Unemployment Insurance,” Journal of Monetary

Economics, 117 (2021): 849; Makoto Nakajima, “A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit

Extensions,” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 59 no. 7 (2012): 686.

26

Mark Duggan, Andrew C. Johnston, and Audrey Guo, Experience Rating As An Automatic

Stabilizer, Working Paper No. 30651 (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of Economic Research,

Nov. 2022): 2.

27

This study did not holistically examine the economic effects of experience rating, including

potential effects on firms’ decisions to hire.

28

The author noted that his estimates lie in the middle-to-upper end of the range of past estimates.

He also assumed that state-level job search behavior and outcomes are unrelated to state-level UI

extensions, except through factors that trigger the extensions. Robert G. Valletta, “Recent

Extensions of US Unemployment Benefits: Search Responses in Alternative Labor Market States,”

IZA Journal of Labor Policy, vol. 3, no. 18 (2014): 20.

29

Nakajima, “A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit Extensions,” 698.

30

Nakajima, “A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit Extensions,” 697.

31

Pei and Xie, “A Quantitative Theory of Time-Consistent Unemployment Insurance” and Nakajima,

“A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit Extensions.”

Page 24 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

32

Ammar Farooq, Adrianna D. Kugler, Umberto Muratori, “Do Unemployment Insurance Benefits

Improve Match and Employer Quality? Evidence from Recent U.S. Recessions,” Working Paper,

No. 27574 (Cambridge, M.A.: National Bureau of Economic Research, rev. April 2022), 20-21.

33

GAO, Unemployment Insurance: Pandemic Programs Posed Challenges, and DOL Could Better

Address Customer Service and Emergency Planning, GAO-22-104251 (Washington, D.C.: June 7,

2022).

34

Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same?

The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession,” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 34, no. 1, pt.

2 (2016); Jeff Larrimore, Jacob Mortenson, and David Splinter, “Earnings Shocks and Stabilization

during COVID-19,” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 206 (2022). Bruce Meyer and Derek Wu, “The

Poverty Reduction of Social Security and Means-Tested Transfers,” ILR Review, vol. 71, no. 5

(2018). Marianne Bitler, Hilary Hoynes, and Elira Kuka, “Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and

the Social Safety Net in the United States,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 36,

no. 2 (2017); Bradley L. Hardy, “Income Instability and the Response of the Safety Net,”

Contemporary Economic Policy, vol.35, no.2 (2017).

35

Bitler and Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same?;” Meyer and Wu,

“The Poverty Reduction of Social Security and Means-Tested Transfers;” Hardy, “Income Instability

and the Response of the Safety Net;” Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka, “Child Poverty, the Great

Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the United States.”

36

Bitler and Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same?,” S422.; Meyer

and Wu, “The Poverty Reduction of Social Security and Means-Tested Transfers,” 1136. Bitler and

Hoynes (2016) also found SNAP and UI to be marginally more countercyclical during the Great

Recession than in previous cycles since 1980.

37

Jeehoon Han, Bruce D. Meyer, and James X. Sullivan, “Income and Poverty in the COVID-19

Pandemic,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer (2020): 87.

38

Jesse Rothstein and Robert G. Valletta, “Scraping by: Income and Program Participation After the

Loss of Extended Unemployment Benefits,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 36,

no. 4 (2017): 880, 882.

39

Larrimore et al., “Earnings Shocks and Stabilization during COVID-19,” 104,602.

40

The study notes that this finding is consistent with the supplemental UI benefits provided by the

CARES Act in 2020. Because these benefits were a fixed weekly amount and not tied to wages

while working, lower-earning beneficiaries were the most likely to replace their earnings. The study

defined earnings as wages and salaries, excluding self-employment.

41

While these studies varied in the set of programs considered as part of the social safety net, they

all included SNAP and UI. Bitler and Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the

Same?;” Hardy, “Income Instability and the Response of the Safety Net;” Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka,

“Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the United States.”

42

This study also mentions that despite being effective at reducing poverty, since 1980 the safety

net appears less responsive to instability for the same demographic groups. Hardy, “Income

Instability and the Response of the Safety Net,” 327.

43

Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka, “Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the

United States,” 358.

44

According to the study, immigrants are not able to access a large share of the safety net due to

lack of eligibility (for unauthorized immigrants) or because access is more limited. Bitler, Hoynes,

and Kuka. “Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the United States,”

380.

45

René Chalom, Fatih Karahan, Kurt Mitman, and Benjamin Pugsley, “Liquidity Effects of

Unemployment Insurance Benefit Extensions: Evidence from Consumer Credit Data,” Paper

presented at a meeting of the Society for Economic Dynamics (2019); Joanne W Hsu, David A.

Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer, “Unemployment Insurance as a Housing Market Stabilizer,” American

Economic Review, vol. 108 no. 1 (2018).

46

According to the study, this finding implies that as long as home prices maintain their values,

mortgage holders receiving UI benefits may use their benefits to pay down housing debts. There

may be less incentive to pay down mortgage debt in a time when house prices are depressed.

Page 25 GAO-24-106056 Economic Downturns

Chalom et al., “Liquidity Effects of Unemployment Insurance Benefit Extensions,” 7.

47

Hsu, et al., “Unemployment Insurance as a Housing Market Stabilizer,” 50.

48

We use the term “food insecurity” to refer to multiple measures of food scarcity used in different

studies, to include “food insufficiency” and “food hardship.”

49

Natasha Pilkauskas, Janet Currie, and Irwin Garfinkel, “The Great Recession, Public Transfers,

and Material Hardship,” Social Service Review, vol. 86 no. 3 (2012): 12; Anna Aizer and Claudia

Persico, “Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Policy Response and Child Well-Being,” Recession

Remedies: Lessons Learned from the U.S. Economic Policy Response to COVID-19 (Washington,

D.C.: The Hamilton Project and the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, Brookings

Institution, 2022): 273; Marianne Bitler, Hilary Hoynes, and Diane Schanzenbach, “The Social

Safety Net in the Wake of COVID-19,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer (2020):

121.

50

The authors defined food hardship based on self-reported responses to whether, in the past 12

months, the household received free food or meals or whether household members experienced

hunger due to not being able to afford enough food. Pilkauskas et al., “The Great Recession, Public

Transfers, and Material Hardship,” 12.

51

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. N, tit. VII, § 702, 134 Stat. 1182,

2092 (2020). “Food insufficiency” is a measure used for the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse

Survey. Specifically, households were considered food insufficient if they reported sometimes or

often not having enough food to eat in the past 7 days. Aizer and Persico, Recession Remedies,

273.

52

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act gave states the option to expand their Medicaid

programs by covering nearly all adults with incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty

level. Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010), as amended by the Health Care and Education

Reconciliation Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-152, 124 Stat. 1029 (2010). States that expanded

Medicaid eligibility criteria made individuals that lost employment-sponsored health insurance more

likely to be eligible to enroll in Medicaid.

53

Sankar Mukhopadhyay, “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion on Job Loss Induced Mental Distress

during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US,” SSM – Population Health, vol. 20, 101279 (2022): 9.

54

This study used self-reported food insufficiency data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse

Survey. Aizer and Persico, Recession Remedies, 274.

55

Bitler, et al., “The Social Safety Net in the Wake of COVID-19,” 121.

56