Title page

October 2023

Advancing Racial and Social Equity in

Wisconsin Farm to School

Strategies for Investing in Historically

Underserved Producers

About the Research Team

This project is a collaborative eort between the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Human Ecology’s

(SoHE) Civil Society and Community Research Department and Center for Community and Nonprofit Studies

(CommNS), the University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension Community Food Systems Program, and

REAP Food Group.

The research team included:

● Allison Crook, Research Coordinator, SoHE

● Allison Pfa Harris, Farm to School Director, REAP

● Jess Guey Calkins, Community Food Systems Educator, Extension Dane County

● Dr. Jennifer Gaddis, PI, Associate Professor, Civil Society and Community Studies, SoHE

● Dr. Amy Washbush, Co-PI, Associate Director for Engaged Research, CommNS, SoHE

● Sara Gia Trongone, PhD Student, University of Wisconsin-Madison Sociology Department

For more information, visit:

https://foodsystems.extension.wisc.edu/advancing-racial-and-social-equity-in-wisconsin-farm-to-school

To reach the research team directly: allisonph@reapfoodgroup.org, [email protected]

About the Advisory Committee

The Advisory Committee provided guidance on the project, with a focus on inclusivity and the development of

resources and strategies to better support Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), socially disadvantaged,

and historically underserved growers and producers in Wisconsin. Thank you to all of the advisory committee

members:

● Amanda Chu, Northeastern Wisconsin Technical College | SLO Farmers’ Co-op | NEW Food Forum

● Andrew Bernhardt, Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection

● Angela Moragne, That Salsa Lady | That Hood Ranch

● Lizzie Messerli, Wisconsin Rapids Public Schools

● Sara George, Renewing the Countryside

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the generous support of the Wisconsin Idea Collaboration Grant,

funding of which comes from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension and the Oce of the Vice

Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education.

Additionally, we are grateful to Vanessa Herald and Emma Richmond-Boudewyns for their support in the early

stages of this project. Thank you also to the many organizations that provided feedback and advice for this

project: Marbleseed, the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection, the Wisconsin

Department of Public Instruction, the School Nutrition Association of Wisconsin, the Healthy School Meals for All

Coalition, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, For Independent Hmong Farmers Corp., and the Michael

Fields Agricultural Institute.

2

Cover page …………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 1

Acknowledgments .…………………………………………………………………………………………….….. 2

Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3

Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………….... 4-5

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6

Historically Underserved Producers ………………………………………………………………………….. 7

Farm to School in Wisconsin ………………………………………………………………………………... 8-9

Farm to School Sales Landscape …………………………………………………………………………. 10-11

Producer Entry into School Markets ………………………………………………………………………... 12

Barriers to Entering the Farm to School Market ……………………………………………………. 13-16

Recommendations for the Farm to School Market …………………………………………………….. 17

Recommendations for Policy Changes ………………………………………………………………... 18-19

Recommendations for Schools and Producers ……………………………………………………….... 20

Recommendations for Organizations ……………………………………………………………………... 21

Healthy School Meals for All Wisconsin …………………………………………………………………... 22

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23

3

Background, Study Purpose, and Methods

Farm to school procurement¹ has immense potential to support economic, environmental, and racial justice, while

also respecting workers and educators, animal welfare, and student health. By prioritizing values-aligned school

meals, school districts can play a critical role in the positive transformation of the food system.

In order to do this, more information is needed about food producers’ experiences in the farm to school market, as

relatively few historically underserved producers have access to farm to school contracts. Advancing racial

and social equity in Wisconsin farm to school requires equitable access to farm to school markets. Wisconsin lacks

data to provide a holistic understanding of how these particular producers access farm to school markets.

This study aims to better understand how Wisconsin’s historically underserved producers are participating

in farm to school procurement, with a focus on understanding how to make their participation in school

food supply chains easier and more profitable. To examine trends, a statewide survey was launched in

February 2023 and six focus groups were held between February and April 2023. In total, 38 survey responses²

were gathered and 21 producers participated in focus groups.

4

Executive Summary October 2023

¹ One of the three components of farm to school, in which local foods are purchased, promoted, and served in the cafeteria or as a snack or taste test.

² The survey response size of 38 is considered a representative sample size. This is evaluated in relation to the Wisconsin Local Food Purchase Assistance Program

(WI LFPA), which engaged the most comprehensive gathering of socially disadvantaged producers across the state—of the 163 LFPA producers awarded, 61% identify as

BIPOC, and 90% identify as socially disadvantaged. Hence, 23% participation of the sum of LFPA producers demonstrates a representativeness rate for this study.

Participant Demographics

21.5% of participants were located in the Northern region of the

state, 13.5% were located in the Central region of the state, and

65% were located in the Southern region of the state.

Among the survey participants of this study, only 1 in 4 producers

are selling their products to schools. Producers that have been

operating their business for 6-10 years were more likely to be

selling to schools than those who have been in operation for 5

years or less, showing that a more established farm has greater

success in accessing farm to school markets. Of those who are

currently selling to schools, all participants produced more than

one type of product (vegetables and meat, for example). The key

issue seems to be that respondents who are not currently

selling to schools have not tried to access farm to school markets. Specifically, 83% of those not currently

selling to schools have not tried to sell to schools. That said, among respondents that are not currently selling to

schools, have not sold to schools in the past, and have not tried selling to schools, 89% are interested in

selling to their distribution area. There is a discrepancy, then, between interest and actualization.

Image represents producers that participated in the survey

5

Summary of Barriers

If historically underserved producers want to access the farm to school market, but are not, what challenges are

they confronting? Producers noted numerous barriers in accessing farm to school procurement, including:

● Knowledge: Producers are unsure how to begin cultivating a connection with schools, with many feeling

overwhelmed by the process and unsure about what products, form, quantity, and delivery schedule

schools are looking for.

● Price: Producers are unsure of schools’ funding for local products, the price point to set, their ability to

compete with large legacy farms or agribusiness corporations like Sysco, and the flexibility of the contracts

around crop failure.

● Seasonality and Infrastructure: The principal growing season for producers is not during the school year,

and this raises a number of issues around processing, aggregation, distribution, and storage of their

products.

● Food Safety: Producers are unsure what food safety standards they must meet to sell to schools. There is

also a lack of needed certifications and infrastructure.

Summary of Recommendations

To address the barriers raised by historically underserved producers, the following recommendations are outlined

for the stakeholder groups of policymakers, schools, and organizations:

Policy Changes

● Create or bolster funding to

support local food purchasing in

schools and supply chain

infrastructure

● Statewide eort for farm to

school, similar to that of the

Wisconsin Local Food Purchase

Assistance Program

School/Producer Partnerships

● Schools adopt values-aligned

procurement models

● Farm to school pilot programs

● Stipends for producers to do

in-school education

● Preseason (or forward) contracts

Organizational Support

● Create a central place to find

farm to school information

● Build a farm to school network

to connect producers to schools,

and include other relevant

actors across the supply chain

● “Train-the-trainer” models

6

The U.S. federal government spends $18.7 billion per year on school breakfast and lunch programs that feed

roughly 30 million preK-12 students. According to the Rockefeller Foundation’s true cost analysis, these programs

generate $21 billion in net value to society through improved health outcomes and poverty reduction. Yet, their

true value could be greatly increased by altering programs and policies to prioritize racial justice, local economic

development, and environmental sustainability.

Stakeholders in Wisconsin and across the U.S. are experimenting with strategies to increase the value of school

meals by serving a greater percentage of “good food” in their cafeterias (as defined by the National Farm to

School Network). Shifting procurement to align with “good food” values has multiple public benefits, including:

(1) enhancing the financial viability of small/mid-scale food enterprises that keep wealth circulating in community

economies; (2) creating new opportunities for historically underserved food producers to access sizable, stable

markets; and (3) ensuring high quality nutrition for students of all socioeconomic and racial backgrounds.

Farm to school procurement is an important strategy for sourcing “good food.” 75% of Wisconsin school food

authorities (SFAs) included in the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Farm to School Census reported serving

local food in the 2018-2019 school year. The National Farm to School Network has documented the numerous and

multifaceted benefits of farm to school for students, producers, and communities.

Farm to school gives students access to high quality local food, ensuring that they have the nutrition needed to

succeed in the classroom. Students are also able to engage in hands-on learning about agriculture, health,

nutrition, and food. For producers, schools oer institutional markets for their products that can provide a

significant financial opportunity for their business. Farm to school also supports communities by connecting

producers, teachers, school administrators, parents, and students. Purchasing food from local producers

strengthens the local economy and creates new jobs across the supply chain (food production, processing,

aggregation, and distribution). Local purchasing reduces food waste and decreases the environmental impacts

related to the transportation of food.

However, tight budgets, federal procurement rules, market dynamics, and long-term impacts of the COVID-19

pandemic make it challenging for schools—particularly those that serve historically disadvantaged populations—

to fully engage in farm to school procurement. At the same time, relatively few historically underserved producers

have access to farm to school contracts.

By identifying the most promising strategies for increasing historically underserved producers’ access to farm to

school markets, this study addresses a pressing research need.

To that end, this study:

(1) Examined the current landscape of historically underserved growers and value-added food producers in

Wisconsin and their current access to farm to school markets, and

(2) Identified the opportunities and needs of historically underserved growers and producers to participate

in farm to school markets.

The following pages present a detailed analysis of these findings and corresponding recommendations for action.

Introduction

7

Farming is a challenging profession. The work is at the whim of the weather, with increasing unpredictability as

climate change advances. Land is expensive and inaccessible to many. The margins of profit are razor thin. The

work takes a toll on the body, and is often isolating. These challenges are only compounded by historical and

present-day discrimination faced by particular demographics of farmers. To acknowledge this reality, the USDA

has created a distinctive category to describe farmers in these circumstances: historically underserved.

Historically underserved farmers are producers that have been “historically underserved by, or subject to

discrimination in, Federal policies and programs.” Farmers that fall under this category include beginning

farmers, socially disadvantaged farmers, veterans, and limited resource farmers.

As a note, throughout this report, the term “historically underserved producers” (or “producers”) will be

used to encompass farmers as well as value-added producers.

In the most recent Census of Agriculture, the eects of this discrimination are apparent nationally and at the

state-level. Across the United States, 95% of all farmers are White, 64% are male, only 27% are beginning

producers, and only 11% are veterans. Within the state of Wisconsin, 99% of all farmers are White, 65% are Male,

only 23% are beginning producers, and only 8% are Veterans. As an attempt to further address these inequities,

and move towards structural food system change, this study is among a number of recent projects and

programs around the state of Wisconsin focusing on historically underserved producers. The research team

hopes that this report, in addition to the work of the Local Food Purchase Assistance program (LFPA) and Local

Foods for Schools (LFS) program, begins to create a more inclusive and thorough understanding of farming and

value-added food production within the state and conveys the needed changes for farm to school programs to be

more viable and profitable for these growers. By better understanding the situation of these producers,

strategies and solutions can be catered to address their unique challenges, barriers, and opportunities.

This study focuses specifically on the diculties that historically underserved producers face when engaging with

the farm to school market. All participants in this study self-identified as belonging to one of the above groups.

The findings of this report, therefore, represent these particular producer demographics. That said, it is

likely that the recommendations posed would benefit all producers.

Historically Underserved Producers

Farm to School in Wisconsin

The true value of school food in Wisconsin could be greatly increased by

altering existing programs and policies to prioritize racial justice, local

economic development, and environmental sustainability. Shifting school

food procurement to align with “good food” values has multiple public

benefits, including (1) enhancing the financial viability of small/mid-scale

food enterprises that keep wealth circulating in community economies; (2)

creating new opportunities for historically underserved food producers to

access sizable, stable markets; and (3) ensuring high quality nutrition for

students of all socio-economic and racial backgrounds.

Farm to school procurement is among the most common strategies that

school districts use for values-aligned school meals, however relatively few

historically underserved food growers and value-added producers have

access to farm to school contracts.

The aim of this study is to better understand the experiences of

Wisconsin’s historically underserved producers with farm to school

procurement, with a focus on understanding the experiences of BIack,

Indigenous, Hmong, and other producers of color. The goal of this study

is to better identify the needs and opportunities of these producers and

to therefore make their sales to schools easier and more profitable.

To examine statewide trends, the research team created a producer survey

and distributed it from February through May 2023. The team conducted

two in-person focus groups: one in February 2023 at the Marbleseed

Organic Farming Conference in La Crosse, WI, and one in April 2023 at

Fondy Farm in Mequon, WI. An additional four virtual focus groups were

conducted between February and April 2023. In total, 38 responses were

collected from the surveys and 21 people participated in the focus groups.

The research team utilized Qualtrics for the study’s survey, and uploaded

survey data into STATA to generate descriptive statistics for key items where

What is Farm to School?

According to the National Farm to

School Network, “farm to school

implementation diers by location but

always includes one or more of the

following:

○ Procurement: Local

foods are purchased,

promoted, and served

in the cafeteria or as a

snack or taste test;

○ School gardens:

Students engage in

hands-on learning

through gardening;

and

○ Education: Students

participate in education

activities related to

agriculture, food,

health, or nutrition.”

For the purposes of this study, due to

the potential economic impact on

producers, this study focused on the

procurement aspect of farm to school.

the response rate was greater than or equal to five. The team transcribed the focus group audio recordings and

developed a shared code book. All textual data was then coded with Dedoose, a qualitative analysis software

program that facilitates simultaneous coding and agreement scoring across multiple coders. The research team

then grouped data into key themes with supporting evidence. All open-ended survey responses were also coded in

Dedoose according to the code book. Insights from the qualitative and quantitative data are shared in this report.

8

Demographics of Study Participants

The demographics of study participants varied among gross cash farm income (GCFI), years of farm

operation, geographical location, and types of products sold (see tables). 62% of the survey participants

owned their land, 27% leased their land, and 11% had another land arrangement (i.e., tribally owned,

conservation easement land, or free community land).

The geographic breakdown of participants within this study follows the regional distribution of the Wisconsin

Local Foods Database. Using the three central categories, 23% of survey participants were located in the

Northern region of the state, 23% were located in the Central region of the state, and 54% were

located in the Southern region of the state. The focus group participant regional breakdown was as

follows: 20% Northern region, 4% Central region, 76% Southern region.

9

Figure 1: Map showing the distribution of producers that

participated in the survey

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Among the survey participants of this study, only 1 in 4

producers are selling their products to schools. Of the 10

respondents selling to schools, 60% have been selling to

schools or school districts for 4 years or more. 50% of these

respondents only sell to one school, but 20% sell their products

to 11 or more schools. Of the 28 respondents not currently

selling to schools, 15%

sold their products to schools in their

distribution area in the past

and 85% did not. All of the

respondents who used to sell to schools in the past would be

interested in doing so again.

Of the 19 survey respondents who

are not currently selling to

schools, have not sold to schools in the past, and have not

tried selling to schools,

89% of respondents are interested

in selling to their distribution area.

A number of producers noted that they had never sold to

schools, with some not even knowing that schools were a

possible market for their products. There was a general

interest among survey and focus group participants in selling

to schools, and a need expressed to better understand the

process as it felt overwhelming. One producer from Dunn

County said,

“I have not done any farm to school and feel

really intimidated by the process.”

In the survey and focus groups, it was not uncommon for

producers to sell to schools on an irregular basis and in small

quantities. One Grant County producer described a process of

“

typically hav[ing] a regular monthly transaction, where the

10

school ends up with 2-3 meals during the month having [my] beef utilized.”

Few producers reported regularly

selling to schools or selling to them in a high quantity.

While this study focuses on the procurement aspect of farm to school, when the definition of farm to school was

posed to producers in the focus groups, many found that they had in fact participated in the educational

realm of farm to school. One producer based in Milwaukee stated, “

We will bring tomato seeds… And we show

[the students] how to plant them and grow in a little cup or even a cardboard carton. And [we] watch them be

fascinated by it. And they ask questions like you know they didn’t know that tomatoes and things actually come

from soil.”

Some producers have used schools gardens as a way to connect to cultural heritage and support

disadvantaged youth. Another Milwaukee-based producer mentioned that they are growing “

specific to a

Hmong population. So [they are] finally going to be able to grow bitter melon in the school garden.”

Image represents producers that participated in the survey

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Farm to School Sales Landscape

11

Larger farms seem more likely to sell their products to

schools (farms with incomes of at least $50,000), with a higher

likelihood of selling to schools as farm income increases

($100,000 or more). 63% of farms with incomes of $100K or

more sold to schools, whereas 50% of farms with incomes of

$50K or more sold to schools.

That said, across farm income sizes, very few survey respondents

indicated they had sold to schools in the past. Those with the

lowest on-farm incomes are the least likely to be currently

selling or to have sold their products to schools in the past.

Among survey participants, producers operating their business

for 6-10 years were more likely to sell to schools than those in

operation for 5 years or less, showing that a more established

farm has greater success in accessing farm to school

markets. Regardless of years of farm operation, the issue seems

to be that respondents who are not currently selling to

schools have not tried to access farm to school markets.

Specifically, 83% of those not currently selling to schools have

not tried to sell to schools.

Of those who are currently selling to schools, all participants

produced more than one type of product (vegetables and

meat, for example). As farms increase the diversity of products

sold, their likelihood of selling to schools increases.

This study found that producers participating in the

procurement aspect of farm to school vary greatly in scale.

Some sell only one product at a small scale to one school, while

others have weekly deliveries of numerous products to multiple

districts. Some have also been donating food to schools. Findings

from the survey indicate that:

89% of farms in the Northern region are not currently selling

to schools. Of the 8 farms in the North not currently selling to

schools, 88% did not sell to schools in the past, and 71% have not

tried to sell their products to schools.

56% of farms in the Central region are not currently selling

to schools. Of the farms in the Central region not currently

selling to schools, 60% did not sell to schools in the past, and

67% have not tried to sell their products to schools.

75% of farms in the Southern region are not currently selling

to schools. Of the farms in the South not currently selling to

schools, 93% did not sell to schools in the past, and 93% have

not tried to sell their products to schools.

According to the most recent Farm to

School Census, in the state of Wisconsin,

69% of school food authorities (SFAs) use

local food in the National School Lunch

Program (NSLP). 16% of SFAs develop

food products with local producers, and

19% have farmers visit their schools.

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Table represents producers that participated in the survey

Many farm to school relationships were initiated by the producer. Examples given were that the producer’s

(grand)children went to the school or that they (or another family member) worked in the school. Some schools

are pursuing local producers—sometimes asking about specific items (e.g. squash); sometimes sending producers

requests to bid. Some challenges mentioned were not having strong relationships to schools in Wisconsin

and needing to learn more to know how to meet the needs of the school as a producer. While some

producers cold-called the schools or used the DPI website to navigate farm to school, a personal relationship is

helpful. Critical to the success of selling to schools is developing strong communication practices between

producers and school personnel—particularly around how much product the schools need and when they

need it. As one Walworth County producer put it,

“The networking and moments to take time with schools have

“My wife is a high school English teacher, so she

cultivated a relationship with the food manager

at the high school cafeteria. It was very

organically grown.” -Grant County producer

12

Producer Entry into School Markets

There are four procurement methods

that schools use to make purchases,

outlined in the table. Local food

purchases are most often completed

through the micro and small purchase

procurement methods. Visit the

Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI)

Local Procurement webpage for

additional information.

For producers in the study that have

successfully sold to schools,

relationships within the school were

critical to their success, such as having

a friend in the school administration. As

one producer from Polk County put it:

“

It's about connections, and networking.

So knowing people within the

organization who know people… it's like

a relationship to the actual people on the

ground.”

Single purchase is below

$250,000

Procurement tool:

3 Bids and a Buy

Transaction below $10,000

(or the local purchase threshold,

whichever is less)

Procurement tool: Retain receipts

from transaction to support price

was “reasonable.” Spread

around future business as able.

Aggregate value of contract

award is equal to or above

$250,000

Formal Procurement tool:

Invitation for Bid (IFB)

Aggregate value of contract

award is equal to or above

$250,00

Formal Procurement tool:

Request for Proposal (RFP)

been helpful and allowed us to find people who are

interested in seeing farms and schools work together.”

Producers who have successfully sold to schools have

received high praise for the quality of their products.

Reasons cited for farm to school success are the quality

of producers’ products and good customer relationship

skills from producers in communication with schools.

13

Barriers to Entering the Farm to School Market

The National Farm to School Network underscores that “policies addressing the historical and ongoing inequities

between Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) farmers and their white counterparts are ultimately

necessary for BIPOC producers to experience a level playing field on which to participate in farm to school” (Farm

to School Policy Handbook, 7).

Though Wisconsin has not extensively analyzed the unique barriers of BIPOC producers related to farm to school,

a University of Minnesota (UMN) Extension and UMN School of Public Aairs study researched this subject in the

neighboring state of Minnesota. Themes that emerged related to barriers faced by BIPOC producers include:

● Historical inequities around land use and distribution

● Forced removal and pilfering of land from Indigenous people

● Systematic denial of land and money to BIPOC farmers

● Requiring of refrigeration and transportation in larger markets is cost prohibitive, making it hard for small

and medium scale farms to enter these markets

● Younger people are not entering the field, reducing the number of future farmers

According to the Minnesota study, the structural inequities that make farm to school additionally challenging for

BIPOC producers are: equipment, time, business skills, land access and ownership, and transportation. Additional

barriers included cultural barriers around language, education, and a lack of agricultural exposure.

These themes also emerged within this study. The following pages provide detailed descriptions of barriers.

discussed in focus groups and survey responses.

Knowledge

A central theme was that producers may not be aware that schools are a potential market for their

products. As one Dane County producer put it,

“I just thought that schools got food from the government. And

they had to buy certain things. And they had to have certain foods on the menu for kids. So I literally never even

thought of it. I didn't even know that that was something that existed.

” The sense of overwhelm in trying to

navigate the farm to school process was a strong theme that appeared in all focus groups; the time,

knowledge, and networking capacity needed to be successful to sell in these markets felt unfeasible to

many. Succinctly said by one Polk County producer,

“I have no idea who to even contact.”

Another Polk

County-based producer shared,

“I think it's at least a mental and logistical barrier, if not an actual physical

barrier, to us to be able to do farm to school.”

Producers have also struggled with school personnel not being

supportive of farm to school. An Adams County producer who works in public education said:

“Even with having

an 'inside' connection, administration and the school boards have been against implementing farm to school.”

“[S]elling to schools is important, but I think… the government pushes and rewards very large legacy farms.

And they leave nothing else for the small guys. Because we are gardens in comparison to them. I think the

government thinks that a small farm is like 80 acres. That's twice the size of this entire farm. So, us with our

two to four acre parcels—in the government's eyes, we basically don't exist.” -Milwaukee-based producer

Barriers to Entering the Farm to School Market

For producers to access the school market, they need additional

people to support the process. Many producers are already at or

above capacity and do not have the energy to navigate the farm

to school process on top of everything they are already doing.

Additional sta (at the farm or within other agencies) to take on

these roles would facilitate their participation in farm to school.

Additionally, producers are unsure what types of products

schools are looking for, and at what quantity they would

need to produce these products. Many producers expressed

a willingness to plan ahead and grow particular products if

they knew that the school wanted them and would purchase

them. Some producers assumed that the volume they could oer

of their products would be too low for schools’ needs. During the

focus groups, some producers found it helpful to hear of the

small quantities that others had sold to schools (60 lbs of beef,

for example). Also, some producers assumed that schools have a

low budget for purchasing food, and were concerned that they

could not sell their products at those prices. As one Dane County

producer put it,

“I would need an initial sense of how much

product [schools] would need, how often, in what

14

form, and at what price.”

Producers are curious about what resources or programs schools have for

purchasing local food, and what incentives are oered to encourage this purchasing. A Polk County-based

producer said,

“I wonder what exists out there for a school like ours. Not that our nutrition director has a ton of

time on her hands.”

Producers are unsure how to initiate contact with a school to see if they would be interested in purchasing

their products. Some producers within this study noted challenges when navigating the DPI website, particularly

when searching for school contacts. Regarding the Wisconsin Local Foods Database (LFD), managed by the DPI

AmeriCorp Wisconsin F2S Program, one producer noted that they called a school contact listed in the database

and never got a call back. There is a lack of understanding among producers about how purchasing contracts are

made, and an assumption that producers need to know the process in order to engage in conversations with

schools. As one Grant County producer put it,

“[I]nstead of having to make three or four phone calls to get to the

right person, it would just be nice to know who's the head of food services, and maybe they don't have all the

authority to decide who's buying what.”

Producers want to know what specific foods schools want, and if there is flexibility around accepting dierent

product forms or product substitutes. Producers expressed concerns about the feasibility of having their

products in the forms that schools need. This was expressed both as a concern around the consistency of the

product (size of chicken breast, or apple, for example), and the ability of schools to use the product in raw or

unprocessed forms (since many schools lack infrastructure for scratch cooking).

As one Door County producer

mentioned,

“being able to be consistent in size, shape, and quantity… [S]ometimes that's really hard.”

Producers

are hoping that schools have flexibility in what products they can accept, since producers may need to

swap out dierent products as a result of the inevitable challenges that are part of the growing season.

Price

Producers are unclear about what price point they should set. Small producers, in particular, are concerned

about the profitability of selling to schools. Producers feel that they cannot compete with larger farms and

corporations—like Sysco, specifically—for the school food market. This sentiment includes concerns about the

ability to break into what appears to be a market dominated by distributors like Sysco, due to the the lower price

point of their products, the quantity of products they can provide, and the flexibility and ease of buyers to use

their service as a “one stop shop.” As one Forest County producer concisely put it,

“Pricing is always a sticking

point, because we can't compete with Sysco.”

There is a serious concern from producers that they will not be

able to sell their products to schools at a price point that reflects the value of their products. This diers

from other market options, such as farmer markets and restaurants. As one Grant County producer described it,

“The pricing is always challenging… absolutely we want—as smaller producers—we want to maximize returns for

our work.”

There is also a concern about the ability for schools to value the extra-nutritional benefits of buying

these products, such as supporting cultural foodways. Expressed by one Dane County producer, “

and then also,

what I may grow is Afro-Indigenous food or culturally relevant food. [The schools] may not even know what that

looks like. How do you even begin to quantify that? What is the value for that? I have my own personal passions

about what is valuable about it.”

Producers have a lack of knowledge around typical school food market prices, and what to charge for

these contracts. Some producers expressed frustration around the time it takes for them to receive payment from

their products when selling to schools. One producer, finding the payment timeline to be too long, specifically

requested to receive payment from schools within 30 days of receiving their product.

15

“[T]hese school districts–to get the best price, they may be locked into someone for a decade… I don't know

enough about the industry... I would think there [are] brokers, or that it's just a whole industry in and of itself.

How does a small producer even begin... to go to the Madison Metropolitan School District and say, ‘Hey, I'd

like to be part of your food system.’ ”

-Dane County producer

Seasonality and Infrastructure

A very frequently cited concern from producers (especially vegetable farmers) is that their prime growing

season is during the summer when school is out of session. As one Forest County producer put it,

“it's that

seasonality of everything. So how do you fix that? I don't know.”

In order to sell to schools, producers need access

to summer school markets, or storage infrastructure so that they can safely store their products until school is

back in session. Season-extension infrastructure, such as green houses or high tunnels, would also help. Likewise,

meat producers are concerned about the storage capacity of schools, which would dictate when the producers

would schedule butchering and how much freezer space producers would need to have.

Producers that have attempted to sell their products to schools raised a number of additional barriers. Many

producers named distribution as one of the biggest challenges. The convenience of the delivery location,

delivery frequency, and vehicle needed were all cited as concerns. The receiving logistics around when products

can be delivered and what infrastructure schools have for accepting deliveries were named as challenges.

One Vernon County producer mentioned that “

the one account we are able to facilitate works because it is directly

on one of our existing delivery routes and we're able to deliver during their narrow receiving window.”

For many

producers, the process for selling to schools is unclear, especially as to how transferable the process is

across schools or districts, and whether contingency plans are available if the producer encounters issues

with providing the product they were contracted to sell. Producers are unsure about how large their operation

needs to be to provide the quantities schools need, the logistics around acceptable product forms, and how

delivery infrastructure works. Some producers expressed that they

“need a clear outline for requirements from

local schools”

(Marathon County producer).

Food Safety

Producers also have significant concerns about the food safety requirements for selling to schools. These

include concerns about on-farm certifications and inspections, as well as concerns about the aggregation,

distribution, transportation, and processing components required for getting food from farm to school. Producers

had specific questions about how the Food Safety Modernization Act aects selling to schools, and if Good

Agricultural Practices (GAP) certification is needed. Many focus group participants were concerned about the

feasibility of getting these certifications.

Many challenges were brought up around the post-harvest of farm products, including the processing of the

product, the storage of the product, and the distribution or delivery of products to schools. Having to process

their farm products in order to be in the form schools need causes a problem for producers. For example, schools

have asked for lettuce to be prewashed and cut, or for squash to be peeled, de-seeded, and cubed. In these

cases, the producers are bound by additional food safety protocols and many lack the time or facilities to do the

processing at their farms or store the processed products. It would be advantageous to growers if schools or

local supply chain partners could process the raw form of their products. As a Dane County producer put

it,

“it doesn't seem like schools can handle the processing needed for most crops. We have had luck with carrots

and daikon radishes, but it seems like they basically don't want anything else.”

Processing of food is often a

bottleneck for schools to accept local products, and third-party processors could provide this support.

16

“Our biggest challenge is fitting into the system that the food service directors have in place for ordering and

delivering.” -Juneau County producer

Recommendations for the Farm to School Market

17

SUMMARY OF BARRIERS

● Knowledge: Producers are unsure how to begin cultivating a

connection with schools, with many feeling overwhelmed by

the process and unsure about what products, form, quantity,

and delivery schedule schools are looking for.

● Price: Producers are unsure of schools’ funding for local

products, the price point to set, their ability to compete with

large legacy farms or agribusiness corporations like Sysco,

and flexibility of the contracts around crop failure.

● Seasonality and Infrastructure: The principal growing

season is not during the school year, and this raises a number

of issues around processing, aggregation, distribution, and

storage of their products.

● Food Safety: Producers are unsure what food safety

standards they must meet to sell to schools. There is also a

lack of needed certifications and infrastructure.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The study’s recommendation highlights are summarized below. The following pages outline recommendations for

the three stakeholder groups of policymakers, schools and producers, and organizations.

18

Policymakers at the local and state level play an important role in making farm to

school more viable for producers and schools across the state. In pursuit of farm

to school policy that addresses the needs of historically underserved producers,

the National Farm to School Network (NFSN) calls for

“legislation that embeds

racial equity in school food procurement preferences as well as land, capital, and

infrastructure access measures, environmentally sound growing practice

incentives, and decision-making power for BIPOC farmers… ensur[ing] that there

are economically viable small and local farms for schools to support”

(NFSN Policy

Handbook, page 19)

.

In particular, the policy changes below are needed.

Additional funding, in the following forms:

● Local food incentives for schools, which would encourage school food

purchases from local producers. As local foods often cost more and may

require more labor to prepare for meal service, a local food incentive could

bring their cost comparable to those of larger vendors. These local food

purchases have multiple benefits: they circulate more money within the

The Local Foods for Schools

(LFS) Program

Through the LFS Program,

Wisconsin’s Department of

Public Instruction (DPI) has

issued non-competitive

sub-awards to School Food

Authorities (SFAs) and

Non-SFAs, like aggregators,

to help address the

challenges of supply chain

disruptions. Sub-awards are

used for local food purchases

targeting small businesses

and/or socially

disadvantaged producers.

local economy; supporting, maintaining, and creating jobs within the local food supply chain. Mechanisms

for funding an incentive vary (NFSN Policy Handbook, page 31). Wisconsin could consider mimicking the

Local Foods for Schools Program (see description in text box), creating additional or lump-sum

reimbursement programs, or matching reimbursement up to a certain amount.

○ Critical to the success of local food incentives is moderating the administrative requirements

needed to collect impact data, so that the paperwork for these incentives is manageable for

producers and school nutrition programs.

● Infrastructure Investment. To be able to access the farm to school market, additional capital investment

is needed for producers so that they can access greenhouses, food storage space, and refrigerated food

transport vehicles.

○ Producers are open to investing in this infrastructure, but are concerned about potential liability;

they ask that other creative solutions be discussed—like using school greenhouses to extend their

growing season, having schools invest in food processing infrastructure, or having distribution

support.

■ The Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection’s (DATCP) Wisconsin

Resilient Food Systems Infrastructure Program oers one example of how funding for this

infrastructure could be distributed. Producers as well as middle of the supply chain actors

(aggregators, processors, distributors) need infrastructure investment to create a robust,

viable farm to school market within the state.

○ For producers that do not own their land, the precarity of land access makes it dicult for them to

invest in further infrastructure. Reducing barriers to land ownership must also be supported.

Special policy consideration should be made for producers in these circumstances.

Recommendations for Policy Changes

19

Equitable farm to school requires making an investment in a

statewide program that would build on the successful model of

the Wisconsin Local Food Assistance Program (WI LFPA).

A number of producers participating in this research are current

participants of the WI LFPA, and they referenced LFPA initiatives that

they believe would be helpful for farm to school. While the WI LFPA

services food banks and food assistance programs, producers noted

that a similar initiative would be helpful for selling to schools. Schools

face many of the same food purchasing issues faced by food banks

and food assistance programs. The Wallace Center Initial Impacts

Report highlights how the LFPA has helped to support and build more

resilient local food systems, expanded economic opportunities for

local and socially disadvantaged producers, and helped to provide

more culturally relevant foods to families and communities. Notable

LFPA initiatives that would be helpful to farm to school include:

● Funding to purchase supplies, like packaging and seeds,

up front. LFPA participants received up to 20% of their total

funding award upfront.

● Outsourced transportation logistics. The WI LFPA provides

Additional recommendations to bolster the farm to school process in Wisconsin include:

● Fully fund the state farm to school grant program, which is included in Wisconsin Act 293 but has never

been funded.

● Use State Administrative Expense (SAE) funding to support statewide farm to school eorts, such as

supporting farm to school positions and continuing farm to school educational opportunities in the state.

● Review state-level licensing requirements and identify opportunities to streamline or reduce

regulations to meet the needs and scale of the local food supply chain.

● Financial support for regional farm to school support organizations to convene and provide local and

regional strategies for moving local foods into schools.

● Financial support for data aggregation eorts on local and regional economic impacts, as well as racial

equity impacts, to identify gaps in programming and provide guidance for future practices and policies.

● Promote programs and policies that encourage purchases from socially disadvantaged and local

producers when possible, as the LFPA and LFS programs have done.

● Within all recommendations, farm to school needs to support Native American food sovereignty and

ensure all funding and policies promote racial and governmental equity (NFSN Policy Handbook, page 35).

support to producers in transporting product from the farm, or a central drop location, to the identified

end-user or the Wisconsin Food Hub for aggregation. The Wisconsin Food Hub then distributes product to

its final destination.

● Food safety support, both in terms of refrigerated transportation and in having a source to directly

connect with to help with licensing and insurance questions.

Recommendations for Schools and Producers

20

Regular contact between school nutrition professionals and producers is

needed to build relationships, allowing each to provide feedback to one

another, address concerns, and build creative solutions to these challenges.

Producers see themselves playing an important role in educating schools

and students about their products and the benefits of sourcing and eating

local food. School nutrition professionals are faced with unique challenges

to process and serve this food, and can provide insight on their needs when

purchasing products. Collaborative recommendations include:

● School nutrition professionals, communities, and producers need

to encourage their districts to support the school nutrition

programs in eorts of values-aligned procurement. This

framework encourages those with purchasing power, like schools, to

purchase food with values in mind instead of solely focusing on

price. Values include environmental sustainability, valued workforce,

animal welfare, local economies, community health and nutrition,

and racial equity. Keeping food values in mind when making

purchases places people over profits, and is a means to make farm

to school more viable and profitable for producers across the state.

● Piloting farm to school purchases for taste tests and one-o

events can be a way for producers and schools to work together to create a values-aligned sales

relationship with lower risks to both the farm and school.

● Providing stipends for producers to do education in the schools. Producers are a wealth of information

around agriculture, health, environmental sustainability, and nutrition. Providing funded opportunities for

producers to teach students oers hands-on education for the students to connect with local food and

growers, and oers producers needed supplemental income, especially during the o season. Interacting

with historically underserved producers can spark students’ interest in agriculture, and is especially

important for girls and BIPOC students to see themselves as belonging within the farming community.

● Forward Contracts. Preseason contracts, also known as forward contracts, are an agreement between the

school and producer for a future purchase of product. They allow producers to plan ahead early in the

season (planting time), and could allow them to extend the season with a greenhouse or other methods if

they knew a purchase was secure. That said, forward contracts are not commonplace among farm to

school markets, and even when they exist, they are not ironclad guarantees of payment, leaving producers

vulnerable to financial loss due to crop failure or other unforeseen circumstances.

○ For the producer’s success in forward contracts, crop insurance and financial support from

appropriate state and local farming organizations are important, as it is unlikely a school can

advance pay a certain percentage of the total sale for no product.

○ School nutrition programs should continue to advocate for producer support programs similar

to the LFPA, which provides 20% of funding upfront to producers. Programs like these build strong

farm to school relationships and lessen risks, especially for small and beginning producers.

Recommendations for Organizations

State agencies, community groups, and nonprofits need to continue to support building connections and

relationships between school nutrition programs and producers. Some successful examples include:

● Brown County’s Farm to School Taskforce

○ This serves as an example of how introductions can grow farm to school relationships between

schools and producers.

● One-o events, like REAP Food Group’s Local Procurement Roundtable

○ This is another example of how to bring producers, schools, and other critical players together to

increase the capacity of the entire farm to school system, including food sourcing, supply chain

infrastructure, mentorship, and product demand.

Producers are asking state agencies, such as the University of Wisconsin, Extension, DPI, or DATCP, to take on the

administrative and bureaucratic burden of figuring out how to make farm to school an easier process for

producers. In particular, historically underserved producers requested:

● A central hub with information about all Wisconsin farms and schools, including which participate in

farm to school. This needs to be straightforward and targeted; some existing websites include

comprehensive farm to school information that is not aimed specifically at producers. While DPI and DATCP

have created the Wisconsin Local Foods Database and Marketplace Meetings, some producers in this study

reported diculty finding and navigating these resources. A central hub with basic, easily digestible, and

accessible farm to school information would be a big help for many producers. Study participants

expressed interest in resources such as a website, webinars, trainings, and fliers.

● Mentoring and information sharing. This information sharing needs to be across the whole supply

chain—paying attention to producers, distributors, aggregators, processors, and finally buyers (schools).

As an example: during the focus groups, many producers found it helpful to hear from others who had

successfully sold to schools, and they mentioned that it would be beneficial to have more opportunities to

speak with other producers. Organizational support could be used to provide informal networking

opportunities, formal mentorship, and coaching programs. Additionally, it would be helpful to provide

information on how to impact farm to school policy, and resources to support producers with farm to

school engagement.

Unrestricted, upfront financial support for train-the-trainer models on wholesale readiness. These funds

(e.g., stipends) should be designated for regional farm to school support organizations and experienced

producers. Financial support for experienced producers to train other producers fosters important relationships

and compensates more experienced producers for their time and expertise.

“...[A]nd just really paying attention to every step that needs to happen, for the workflow of it

all, and just making sure that the producer and the school district or whoever we're looking to

sell to is also very well informed and that everybody understands.” -Dane County producer

21

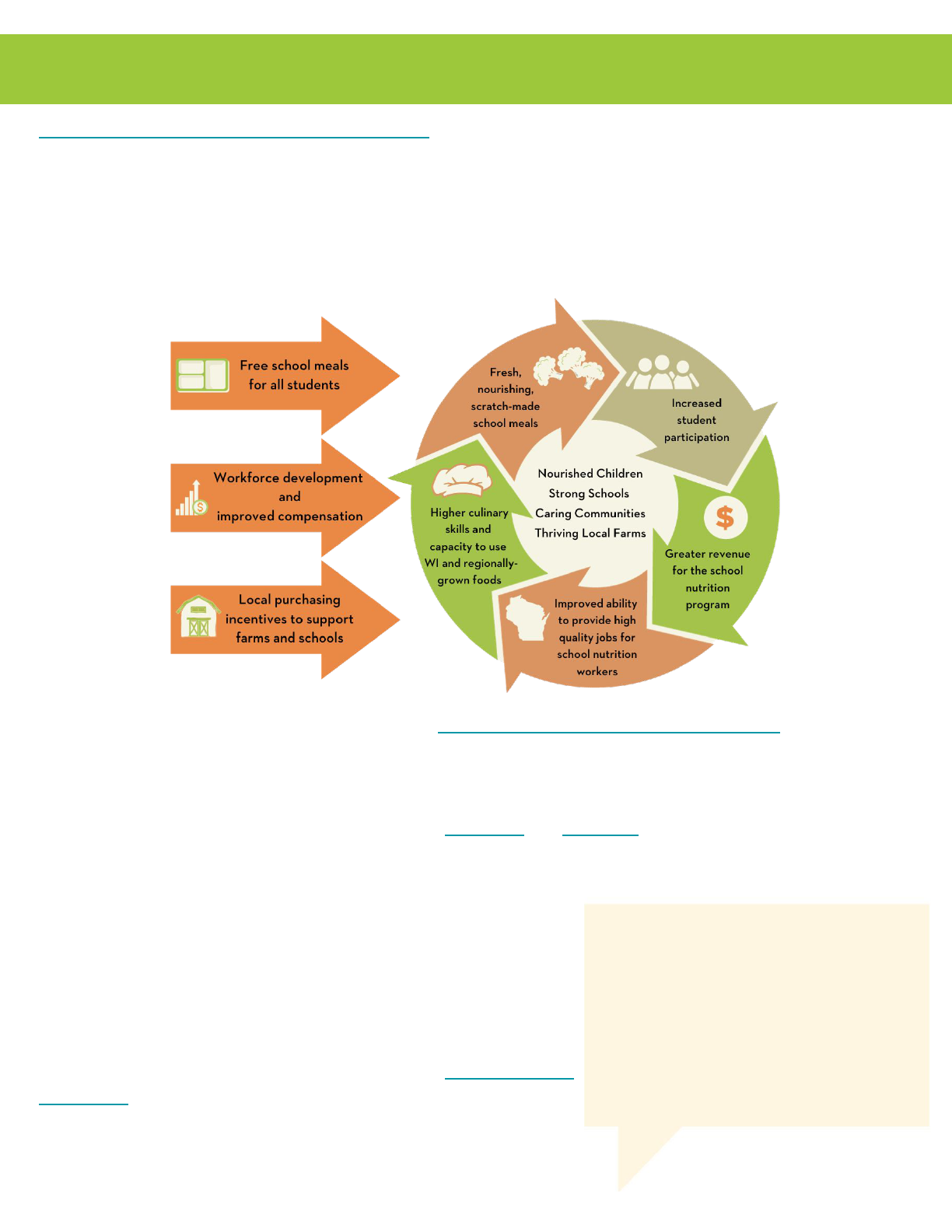

Healthy School Meals for All Wisconsin

The Healthy School Meals for All Coalition (HSM4A) is an organization made up of more than 80 individuals,

groups and organizations in Wisconsin advocating for free school meals for all K-12 students.

Free school meals would provide all students with access to school breakfast and lunch at no cost to their families

and reduce the administrative burden for school nutrition professionals. Free meals for all is also a strategy to

advance farm to school within Wisconsin by stabilizing school cafeteria revenues and administrative processes

and allowing school nutrition directors to spend additional time and energy on building relationships with local

producers.

According to the National Farm to School Network’s report on State Universal (Free) Meal Policies, states with free

meals for all have also increased their investment in the local food system, often through local food purchasing

policies like incentives and grant programs. These policies also emphasize values-based purchasing so that

schools can source products from producers who are historically underserved or are using environmentally-friendly

practices. For local purchasing incentive programs in Minnesota and California, applicants that “pledge to

purchase from emerging producers such as women, veterans, persons with disabilities, Native American/Alaska

Native, communities of color, young and beginning farmers, and LGBTQ+ farmers” are given priority for funding.

"Local farmers want to feed kids in local

schools. There is a huge disconnect

between local growers and school lunch

programs. Administrators and School

Boards need to support teachers looking

to implement on-campus and Farm to

School programming.”

-Farmer

speaking in support of HSM4A

HSM4A’s eorts complement the work of this study and have

substantive potential to bolster Wisconsin farm to school. In addition

to advocating for free meals for all, the research team recommends

advocacy for local food purchasing policies, specifically purchasing

from historically underserved producers within the state. These, in

conjunction with workforce development and improved compensation

for school nutrition professionals (as discussed in the Hungry for Good

Jobs Report on the state of Wisconsin’s school nutrition workforce),

are necessary ingredients to maximize the true value (social,

economic, and environmental) of school meal programs in Wisconsin.

22

23

Conclusion

This study:

(1) Examined the current landscape of historically underserved growers and value-added food producers in

Wisconsin and their current access to farm-to-school markets, and

(2) Identified the opportunities and needs of historically underserved growers and producers to participate

in farm to school

Farm to school procurement oers a powerful opportunity for the state of Wisconsin to prioritize racial justice,

economic development, and environmental sustainability. The barriers faced by historically underserved producers

in accessing the farm to school market are unique, and the changes needed to address these challenges are

equally specific. By providing a deeper understanding of the circumstances of historically underserved producers,

and corresponding recommendations for change, the hope is that the findings of this study produce actionable

results across the state.

By shifting the farm to school procurement model to one that supports “good food values,” Wisconsin can:

(1) enhance the financial viability of small/mid-scale food enterprises that keep wealth circulating in

community economies;

(2) create new opportunities for historically underserved food producers to access sizable, stable markets;

and

(3) ensure high quality nutrition for students of all socio-economic and racial backgrounds.