Federal Agency Use of Electronic Media

in the Rulemaking Process

Cary Coglianese

University of Pennsylvania

Final Report to the Administrative Conference of the United States

December 5, 2011

This report was prepared for the consideration of the Administrative Conference of the

United States. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect

those of the members of the Conference or its committees.

1

Federal Agency Use of Electronic Media in the Rulemaking Process

*

Cary Coglianese

†

One of the most significant powers exercised by federal agencies is their power to make

rules. These agency rules or regulations bind millions of individuals and businesses, imposing

substantial costs on them for compliance. Agencies impose their rules, however, in an attempt to

advance important goals for society. The nation’s economic prosperity, public health, and

security all depend on rules issued by administrative agencies.

Given the substantive importance of agency rulemaking, the process by which agencies

develop these rules has long been subject to procedural requirements aiming to advance

democratic values of openness and public participation. The Administrative Procedure Act of

1946 (APA), for example, has mandated that agencies provide the public with notice of proposed

rules and allow them an opportunity to comment on these proposals before they take final

effect.

1

Since 1966, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) has established that the public has a

right to access certain information held by the government.

2

Court decisions reviewing agency

rules have tended to reinforce these statutes’ principles of openness and public participation in

the rulemaking process.

3

With the advent of the digital age, government agencies have encountered both new

opportunities and new challenges in carrying out these longstanding principles. The

development of the Internet has resulted in increasing efforts to make more rulemaking

*

This report was prepared for the consideration of the Administrative Conference of the United States. The views

expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the members of the Conference or its

committees.

†

Edward B. Shils Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science, University of Pennsylvania Law School, and

Director, Penn Program on Regulation. The author gratefully acknowledges the dedicated support provided by a

team of website reviewers from the student body of the University of Pennsylvania Law School as well as excellent

assistance provided by members of the University of Pennsylvania Law School library, faculty support, and

information technology staffs. Several student research assistants also assisted in various aspects of this study.

Jessica Goldenberg provided crucial and capable overall management of the website analysis discussed in Part III

and played a key role in the interviews discussed in Part IV; Eric Merron provided support with data entry and

analysis on the website analysis; David Rosen assisted with interviews, research, and drafting; Christopher Wahl

provided extensive support with research, drafting, and editing; Kamya Mehta provided research and drafting on

several discrete issues; and Stephanie Lo studied website accessibility to the disabled. Professor Stuart Shapiro of

Rutgers University helpfully consulted and provided assistance with the website coding.

1

5 U.S.C. § 553 (2006).

2

Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2006).

3

See, e.g., Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins., 463 U.S. 29, 49 (1983) (affirming that “an

agency must cogently explain why it has exercised its discretion in a given manner”); Citizens to Preserve Overton

Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 419 (1971) (holding that litigation affidavits are an “inadequate basis for review” under

the APA, which requires that the “whole record” developed by the agency in the rulemaking process be considered);

Sierra Club v. Costle, 657 F.2d 298 (D.C. Cir. 1981) (finding that the legitimacy of unelected administrative

rulemakers is dependent upon “the openness, accessibility, and amenability of these officials to the needs and ideas

of the public from whom their ultimate authority derives”).

2

information available online as well as to elicit public participation via electronic means of

communication. Across the full range of functions and services they provide, federal agencies

have made great strides to connect with the public through electronic media, such as websites.

Indeed, as one government official recently noted, “When people interact with an agency today,

they are most likely to go to its website. The website has become the front door for members of

the public to interact with their government.”

4

And data seem to bear this out. Although

measures of overall satisfaction in the federal government have recently declined, public

satisfaction with agency websites remains quite strong.

5

Indeed, according to an analysis by the

American Customer Satisfaction Index, “federal websites are one of the most satisfying aspects

of the federal government.”

6

Of course, when it comes to the use of electronic media, no entity can rest on its laurels.

Agencies may be able, first of all, to do better still than they are doing at present. Moreover, the

rapid pace of innovation in both new technologies and new applications of existing technologies

requires the federal government to continue seeking improvements in order to maintain public

satisfaction. Despite the current level of satisfaction with federal websites, the Obama

Administration has already targeted agency websites as a major part of its “Campaign to Cut

Waste,” specifically seeking “ways to improve the online experience with Federal websites.”

7

Some agencies undoubtedly trail behind others in their use of electronic media. And not all

functions of agencies have achieved the same level of accessibility via the Internet. General

satisfaction levels do not necessarily measure how well agencies are doing with respect to their

use of electronic media in support of their rulemaking functions, for example.

In this report, I survey the landscape of agencies’ contemporary efforts to use electronic

media in the rulemaking process. Drawing on a review of current agency uses of the Internet, a

systematic survey of regulatory agencies’ websites, and interviews with managers at a variety of

federal regulatory agencies, I identify both existing “best practices” as well as opportunities for

continued improvement. As such, this study, commissioned by the Administrative Conference

of the United States (ACUS), is intended as one further input into a broader series of

government-wide efforts to study and improve federal agencies’ use of electronic media. Over

the years, many agencies have used the Internet to improve greatly the public’s access to

information about rulemaking and to provide enhanced opportunities for public input into agency

decisions. Through both large, cross-cutting initiatives – such as the online portal

Regulations.Gov – as well as smaller ones at individual agencies, the federal government has

undertaken numerous efforts to promote transparency of and public participation in the

rulemaking process. In addition, a growing administrative infrastructure has emerged both

within and across agencies, such as through the government-wide Federal Web Managers

4

Telephone interview with Rachel Flagg, Co-Chair of the Federal Web Managers Council (July 1, 2011).

5

The American Customer Satisfaction Index, Citizen Satisfaction with Federal Government Services Plummets,

January 25, 2011, available at http://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=237:acsi-

commentary-january-2011&catid=14&Itemid=297. In citing public satisfaction with government websites, I am not

suggesting that satisfaction provides the appropriate metric for designing and assessing agency websites, but only

that such satisfaction indicates how important government websites have become as a means of public interaction

with the government. For further discussion of satisfaction, see infra Part V, Recommendation 7.

6

Id.

7

Erin Lindsay, Open for Questions: Live Chat on Improving Federal Websites, July 11, 2011, available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/07/11/open-questions-live-chat-improving-federal-websites.

3

Council, for standardizing and improving the design of federal agency websites as well as

agency use of interactive electronic media. As such, this report emerges at an energetic time in a

field fertile for governmental innovation, with undoubtedly no shortage of ideas for continued

development of the federal government’s digital infrastructure.

What makes this report distinctive is its principal focus on electronic media as it pertains

to agency rulemaking. In addition to suggesting that agencies continue many of their efforts to

improve their use of electronic media generally, I offer seven recommendations in this report for

both ACUS and agencies to consider with the specific aim of improving the accessibility of

rulemaking through the use of digital technology. These recommendations are linked by an

emphasis on using electronic media, such as agency websites and social media tools, to facilitate

public participation in the rulemaking process.

In Part I of this report, I present a brief history of the early development of the federal

government’s use of electronic media in the rulemaking process so as to clarify both the goals of

so-called e-rulemaking as well as to clarify what aspects of agencies’ use of electronic media this

report is, and is not, principally aimed at addressing. It is not, for example, focused on the

federal rulemaking portal, Regulations.gov, which has already been the subject of several

detailed reports offering numerous recommendations.

8

Nor does it provide an in-depth

assessment of the Department of Transportation-Cornell University collaboration on Regulation

Room, which also has generated separate assessments by those involved in its development.

9

In Part II of this report, I provide illustrative descriptions of a broad range of e-

rulemaking practices that exist beyond just Regulations.gov or Regulation Room, in order to

draw particular attention to the ways that agencies have used websites and social media in

connection with rulemaking. This part highlights what might be considered current “best

practices” across the federal government in the use of electronic media to support rulemaking.

This part makes concrete the existing efforts underway and provides a baseline against which to

consider recommendations for further improvements.

In Part III, I discuss the results of a systematic study of the characteristics and features of

90 federal agency websites. This study replicates and builds upon a similar study from about

five years ago, providing a comprehensive account of the differences that continue to exist across

federal agency websites and of the remaining opportunities to make improvements in how

rulemaking information is provided through these sites.

In Part IV, I synthesize the findings from a series of interviews conducted with officials

at ten regulatory agencies about their use of electronic media to support rulemaking. These

interviews were intended to supplement the quantitative analysis of agency websites, providing

8

Cary Coglianese, Heather Kilmartin & Evan Mendelson, Transparency and Public Participation in the Federal

Rulemaking Process: Recommendations for the New Administration, 77 G

EO. WASH. L. REV. 924, 939-41 (2009);

C

OMMITTEE ON THE STATUS AND FUTURE OF FEDERAL E-RULEMAKING, ACHIEVING THE POTENTIAL: THE FUTURE OF

FEDERAL E-RULEMAKING (2008), available at http://ceri.law.cornell.edu/erm-comm.php. I was a member of the

Committee on the Status and Future of Federal e-Rulemaking.

9

Cynthia R. Farina et al., Rulemaking 2.0, 65 U. MIAMI L. REV. 395 (2011).

4

qualitative insights from those directly involved in the development and management of agency

use of electronic media.

Finally, in Part V, drawing upon my findings in Parts II, III, and IV, I present and explain

a series of seven recommendations for consideration by ACUS to enhance public participation in

e-rulemaking. These recommendations are intended as additional inputs into the ongoing

management processes within and across agencies that aim to make websites and other uses of

electronic media “a bright spot for government in years to come.”

10

I. The Development and Goals of E-Rulemaking

Throughout the past several decades, the Administrative Conference of the United States

(ACUS) has taken a leadership role in efforts to guide the effective deployment of digital

technology by administrative agencies. As early as 1988, ACUS adopted recommendations on

the release of computer-stored information, noting that “[n]ew information technologies can

improve public access to public information.”

11

In 1990, ACUS reaffirmed that “[c]hanges in

the format of agency information from paper to existing and future electronic media [should] not

reduce the accessibility of information to the public.”

12

A few years later, the Clinton

Administration’s National Performance Review recommended that agencies “increase use of

information technology” in the rulemaking process.

13

In 1996, Congress passed the Clinger-

Cohen Act that called upon agencies to improve their management of information technology so

as, among other things, to improve the “dissemination of public information.”

14

Starting in the 1990s, agencies began to use the Internet in earnest to communicate with

the public about rulemaking and other important functions and services. The public began to be

able to access the Federal Register and the Code of Federal Regulations online,

15

and Congress

amended the Freedom of Information Act in an attempt to facilitate the greater disclosure of

electronic information.

16

Agencies started to create online docket rooms and to accept public

10

The American Customer Satisfaction Index, supra note 5.

11

Admin. Conf. of the U.S., Recommendation 88-10: Federal Agency Use of Computers in Acquiring and Releasing

Information, 1 C.F.R. § 305.88-10 (1988), available at http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/admin/acus/3058810.html.

See also Henry H. Perritt, Electronic Acquisition and Release of Federal Agency Information: Analysis of

Recommendations Adopted by the Administrative Conference of the United States, 41 A

DMIN. L. REV. 253, 255

(1989); Admin. Conf. of the U.S., Recommendation 89-8: Agency Practices and Procedures for the Indexing and

Public Availability of Adjudicatory Decisions, 1 C.F.R. § 305.89-8 (1989), available at http://www.law.fsu.edu/-

library/admin/acus/305898.html.

12

Admin. Conf. of the U.S., Recommendation 90-5: Federal Agency Electronic Records Management and Archives,

1 C.F.R. § 305.90-5 (1990), available at http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/admin/acus/305905.html.

13

NAT’L PERFORMANCE REV., OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT, REG04: Enhance Public Awareness and

Participation, in I

MPROVING REGULATORY SYSTEMS (Sept. 1993), available at http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/npr/-

library/reports/reg04.html.

14

40 U.S.C. § 11302(b).

15

See Cary Coglianese, E-Rulemaking: Information Technology and the Regulatory Process, 56 ADMIN. L. REV.

353, 363 (2004) [hereinafter Coglianese, Information Technology].

16

Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-231, 110 Stat. 3048 (amending 5

U.S.C. § 552).

5

comments submitted by email.

17

In some rulemakings, electronically submitted comments

numbered in the tens of thousands.

18

With the dawn of the new century, interest in e-rulemaking grew. Congress passed the E-

Government Act in 2002, requiring federal agencies to accept electronically submitted public

comments on rules and to publish regulatory dockets online.

19

Several large regulatory agencies,

such as the Department of Transportation and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

established their own online docket systems.

20

Although few other agencies took steps to create

online docket systems, some did develop electronic dialogues over proposed rules that “actively

encourage[d] considered back-and-forth conversation.”

21

In its first term, the Bush Administration took steps to centralize e-rulemaking. In

January 2003, it rolled out a centralized web-based portal for rulemaking information known as

Regulations.gov, which was envisioned both as a one-stop shop for information about

rulemaking across the entire federal government as well as a central input site for public

comments.

22

Two years later, Regulations.gov came to be supported by a Federal Docket

Management System (FDMS) that could house in one central electronic location rulemaking

information that otherwise had been kept in disparate paper and electronic dockets scattered

across the federal government.

23

By 2008, it could be said that “[m]ore than 170 different

rulemaking entities in 15 Cabinet Departments and some independent regulatory commissions

[were] using a common database for rulemaking documents, a universal docket management

interface, and a single public website for viewing proposed rules and accepting on-line

comments.”

24

Regulations.gov has garnered considerable attention from academic observers as well as

governmental practitioners. Although Regulations.gov has received many plaudits,

25

it has been

subjected to its share of criticism too. Some observers, for example, have faulted the

completeness of the information Regulations.gov purports to contain, the usability of its search

17

See Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at 364.

18

For further discussion of the history of e-rulemaking, see Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at

363-66. Subsequent empirical analysis has failed to find that the introduction of electronic submissions of

comments made any systemic impact on the number of comments agencies received, even though in a few highly

salient rules the number of comments did appear to increase. See Cary Coglianese, Citizen Participation in

Rulemaking: Past, Present, and Future, 55 D

UKE L. J. 943 (2006) [hereinafter Coglianese, Citizen Participation];

Steven J. Balla & Benjamin M. Daniels, Information Technology and Public Commenting on Agency Regulations, 1

R

EG. & GOVERNANCE 46 (2007).

19

E-Government Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-347, 116 Stat. 2899 (2002) (codified as amended in scattered

sections of 5, 10, 13, 31, 40, 41, and 44 U.S.C.).

20

See Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at 364-65.

21

Thomas C. Beierle, Discussing the Rules: Electronic Rulemaking and Democratic Deliberation 7 (Resources for

the Future, Discussion Paper No. 03-22, 2003), available at http://www.rff.org/documents/RFF-DP-03-2.pdf.

22

See Coglianese, Citizen Participation, supra note 18, at 946.

23

Id.

24

COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS AND FUTURE OF FEDERAL E-RULEMAKING, supra note 8.

25

A page on the Regulations.gov website lists all of its awards. See http://www.regulations.gov/#!aboutAwards (last

visited July 13, 2011). In addition, the General Services Administration and the Federal Web Managers Council

have listed Regulations.gov as an example of a “best practice” in a governmental website for its effort to consolidate

regulatory information and reduce duplication across agencies. See Agency Examples, H

OWTO.GOV, http://www.-

usa.gov/webcontent/reqs_bestpractices/best_practices/examples.shtml (last visited June 16, 2011).

6

function, and the overall complexity of its design.

26

Agency officials, governmental auditors,

and independent expert panels have scrutinized Regulations.gov, offering numerous

recommendations for its improvement in management, functionality, and design.

27

In response

to these suggestions, Regulations.gov has been modified considerably over the years, so that the

site’s functionality has markedly improved over its initial design. Although more improvements

can surely be made, the developers of Regulations.gov have no shortage of recommendations to

consider, so this report focuses on agency websites and uses of social media which are distinctive

enough to warrant their own study.

28

Whether with Regulations.gov, websites, or social media tools in mind, information

technology’s proponents have emphasized several distinct, potentially complementary goals for

the use of electronic media in the rulemaking process: (1) promoting democratic legitimacy, (2)

improving policy decisions, and (3) lowering administrative costs.

29

First, information

technology can be designed to help inform the public about prospective decisions and thereby

enable them to contribute input to governmental decision makers that is both more meaningful as

well as more frequent.

30

Second, information technology can enhance the quality of public

policy decisions.

31

One way it does so is by facilitating participation by a broader set of experts

and other knowledgeable commentators. As I have written elsewhere, “[t]he local sanitation

engineer for the City of Milwaukee … will probably have useful insights about how new EPA

drinking water standards should be implemented that might not be apparent to the American

Water Works Association representatives in Washington, DC.”

32

In other words, information

technology better allows government officials to tap into what the current administrator of the

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Cass R. Sunstein, has called the public’s

“dispersed knowledge.”

33

As President Obama has indicated, “public officials benefit from

having access to that dispersed knowledge.”

34

Finally, information technology can lower

administrative costs.

35

Well-designed information systems can enable agency staff to increase

26

For a summary of such complaints, see Farina et al., supra note 9, at 403-04.

27

Jeffrey S. Lubbers, A Survey of Federal Agency Rulemakers’ Attitudes About E-Rulemaking, 62 ADMIN. L. REV.

451 (2010); Coglianese, Kilmartin & Mendelson, supra note 8; C

OMMITTEE ON THE STATUS AND FUTURE OF

FEDERAL E-RULEMAKING, supra note 8; CURTIS W. COPELAND, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL 34210, ELECTRONIC

RULEMAKING IN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT 37-42 (2008), available at

http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34210.pdf; U.S.

GOV’T ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE, GAO-10-872T, ELECTRONIC

RULEMAKING: EFFORTS TO FACILITATE PUBLIC PARTICIPATION CAN BE IMPROVED 29 (2003), available at

http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03901.pdf.

28

Assessments of the Department of Transportation’s use of the Regulation Room developed by researchers at

Cornell University would also be informative, but as others are already engaged in such analysis Regulation Room is

treated as outside the scope of this report. See Farina et al, supra note 9.

29

Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at 372. See also Farina et al., supra note 9, at 407-08

(dividing the goal of improving policy so as to generate a four-fold set of goals: (1) “regulatory democracy,” (2)

“new information,” (3) “better policy,” and (4) “doing more with less.”)

30

Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at 372-74.

31

Id. at 374.

32

Cary Coglianese, Weak Democracy, Strong Information: The Role of Information Technology in the Rulemaking

Process, in G

OVERNANCE AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY: FROM ELECTRONIC GOVERNMENT TO INFORMATION

GOVERNMENT 101, 117 (Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger & David Lazer eds., 2007).

33

CASS R. SUNSTEIN, INFOTOPIA: HOW MANY MINDS PRODUCE KNOWLEDGE (2006).

34

Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government, 2009 DAILY COMP. PRES. DOC. 10 (Jan. 21, 2009).

35

Coglianese, Information Technology, supra note 15, at 376.

7

their productivity, reduce the costs of replying to FOIA requests, and eliminate overlapping

reporting requirements.

Each of these goals can be found in the current administration’s Open Government

Initiative. On his first day in office, President Obama issued a government-wide memorandum

calling upon agencies to promote transparency, public participation, and collaboration, reasoning

that “[o]penness will strengthen our democracy and promote efficiency and effectiveness in

Government.”

36

Elaborating on the principles outlined in the President’s memo, the Office of

Management and Budget (OMB) subsequently called upon agencies to increase their use of the

Internet to advance the President’s goals.

37

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

further clarified that “the Internet should ordinarily be used [by agencies] as a means of

disclosing information, to the extent feasible and consistent with law.”

38

In early 2011, President

Obama issued an executive order on regulation that called upon agencies to “afford the public a

meaningful opportunity to comment through the Internet on any proposed regulation” and urged

agencies to use the online dockets accessible via Regulations.gov.

39

More recently, he has issued

a further executive order, as part of a broader effort to improve customer service, that calls upon

agencies to develop better ways of serving the public via the Internet.

40

The clear signal from

the current administration – and a signal extending back to the earliest days of e-rulemaking –

has been for agencies to use electronic media to engage early and often with the public.

II. Current Uses of the Internet and Agency Rulemaking

Around the world, “nearly all governments have websites.”

41

The World Wide Web

provides a platform for governments to communicate with their citizens and with other

individuals and organizations; for members of the public to communicate to government

officials; and for both government officials and the public to interact with each other using Web-

based tools and media. In these ways, information technology has assertedly “empowered

36

Memorandum, supra note 34.

37

Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Exec. Office of the President, Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments

and Agencies: Open Government Directive 1 (Dec. 8, 2009), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/assets/-

memoranda_2010/m10-06.pdf.

38

Office of Info. & Reg. Affairs, Exec. Office of the President, Memorandum for the Heads of Executive

Departments and Agencies: Disclosure and Simplification as Regulatory Tools

6 (Jun. 18, 2010), available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/inforeg/disclosure_principles.pdf.

39

Exec. Order. No. 13,563, 76 Fed. Reg. 3821, 3821-22 (Jan. 18, 2011). See also Cary Coglianese, New Executive

Order Promotes Public Participation, R

EGBLOG (Jan. 18, 2011), http://www.law.upenn.edu/blogs/regblog/2011/-

01/new-regulation-executive-order-promotes-public-participation.html.

40

Exec. Order. No. 13,571, 76 Fed. Reg. 24339, 24339 (Apr. 27, 2011). In implementing this executive order, the

Obama Administration plans both to seek public input on ways to improve agency use of the Internet and to update

federal guidelines on the development of agency websites. See The Open Government Partnership: National Action

Plan for the United States of America 8 (Sep. 20, 2011), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/-

us_national_action_plan_final_2.pdf.

41

U.N. DEP’T OF ECON. & SOC. AFFAIRS, U.N. E-GOVERNMENT SURVEY 2010: LEVERAGING E-GOVERNMENT AT A

TIME OF FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC CRISIS, at 77, U.N. Doc. ST/ESA/PAD/SER.E/131, U.N. Sales No. E.10.II.H.2

(2010), available at http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan038851.pdf.

8

citizens to become more active in expressing their views on many issues, especially on issues

concerning environment, health, education and other areas of government policy.”

42

Enthusiasm about e-government has contributed to a proliferation of uses of electronic

media by U.S. regulatory agencies. A complete accounting of all federal government uses of

electronic media in connection with rulemaking would be an expansive undertaking; however,

even a brief review of the highlights in this area reveals a striking breadth of innovation and

provides, in combination with the original data collection reported in Parts III and IV of this

report, a useful point of reference for recommendations to ACUS. Obviously the best of these

current practices within agencies should be emulated by other agencies. Regulatory agencies

have constructed new websites specifically to support public access to and participation in their

rulemaking proceedings, and they have also begun to use social media tools to support their

rulemaking efforts. In addition, several government-wide initiatives as well as private projects

have emerged that either make rulemaking information available to Internet users or otherwise

support agency rulemaking.

A. Agency Websites

Each regulatory agency has its own website, replete with information about all aspects

of its operations and activities. In Part III, I report on the findings of a comprehensive study of

both the general features of these individual agency websites as well as specific features related

to rulemaking. Here it is helpful to note that a few agencies have recently developed highly

specialized portions of their own websites to support their overall rulemaking efforts. These

practices deserve to be highlighted as the kind of efforts that all major rulemaking agencies

should consider.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)

43

maintains a specialized

webpage entitled “Public Comments,” which allows users to submit and view comments on all

of CFTC’s open rulemakings (Figure 1).

44

CFTC also maintains a separate webpage for all of

the rules proposed under the Dodd-Frank Act.

45

Links from the CFTC homepage take users to

both webpages. At these webpages, users may submit their own comments as well as sort and

search for comments that others have submitted. A help feature explains how to use the

website to submit a comment on the proposed rules.

46

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created a website that the agency

initially called its “Rulemaking Gateway” but now calls a “Regulatory Development and

42

Id. at 84.

43

U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMM’N, http://www.cftc.gov (last visited June 6, 2011).

44

Public Comments, U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMM’N, http://comments.cftc.gov/PublicComments/-

ReleasesWithComments.aspx (last visited June 6, 2011).

45

Dodd-Frank Proposed Rules, U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMM’N,

http://www.cftc.gov/LawRegulation/-DoddFrankAct/Dodd-FrankProposedRules/index.htm (last visited June 14,

2011).

46

How to Submit a Comment, U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMM’N, http://www.cftc.gov/LawRegulation/-

PublicComments/HowtoSubmit/index.htm (last visited June 14, 2011).

9

Figure 1: U.S. Commodity Future Trading Commission’s Public Comments Webpage

Source: http://comments.cftc.gov/PublicComments/ReleasesWithComments.aspx (last visited May 23, 2011)

Retrospective Review Tracker” – or what the agency refers to as “Reg DaRRT,” for short. As

the agency has described, Reg DaRRT “provides information to the public on the status of

EPA’s priority rulemakings and retrospective reviews of existing regulations.”

47

EPA

rulemakings appear on Reg DaRRT soon after the agency’s Regulatory Policy Officer

approves their commencement, typically appearing online well in advance of the appearance of

any notice of the rulemaking in the semiannual regulatory agenda or in any Federal Register

notice.

48

Reg DaRRT enables the public to track rulemakings from the earliest pre-proposal

47

Reg DaRRT, U.S. ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY, http://www.epa.gov/regdarrt (last visited Oct. 14, 2011). Reg DaRRT

was previously named the Rulemaking Gateway, but was renamed on August 22, 2011. See Recent Upgrades, U.S.

ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY, http://yosemite.epa.gov/opei/RuleGate.nsf/content/upgrades.html (last visited Oct. 14,

2011). Reg DaRRT contains the same basic design as the Gateway and much the same features. It differs in that

Reg DaRRT no longer provides an easy way to identify and provided input on EPA rules open for comment, see

infra notes 188-191 and accompanying text, but it also allows users to view the agency’s retrospective reviews of

existing regulations. Id. The transition from Rulemaking Gateway to Reg DaRRT occurred after an initial version

was shared with ACUS and discussed by its rulemaking committee. In this final report, most references to this

example of an agency’s innovative use of electronic media are to Reg DaRRT rather than to Gateway.

48

About Reg DaRRT, U.S. ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY,

http://yosemite.epa.gov/opei/RuleGate.nsf/content/about.html?opendocument (last visited Oct. 14, 2011).

10

stage through to completion.

49

To facilitate commenting, Reg DaRRT provides users with

instructions on how to comment on a regulation on Regulations.gov.

50

Users may view all Reg

DaRRT rules in one list or may sort through them by their phase in the rulemaking process or

by other criteria.

51

In response to Executive Order 13,563,

52

Reg DaRRT also allows users to

view EPA’s retrospective reviews of current regulations.

53

Figures 2 and 3 provide

screenshots of Reg DaRRT. Figure 2 shows its homepage, while Figure 3 shows its display of

the full list of EPA rules on Reg DaRRT.

Figure 2: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Reg DaRRT: Homepage

Source: http://www.epa.gov/regdarrt (last visited Oct. 14, 2011)

49

Reg DaRRT, supra note 47.

50

Comment on a Regulation, U.S. ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY, http://yosemite.epa.gov/opei/RuleGate.nsf/content/-

phasescomments.html?opendocument (last visited Oct. 14, 2011).

51

Reg DaRRT, supra note 47.

52

Exec. Order. No. 13,563, 76 Fed. Reg. 3821, 3821-22 (Jan. 18, 2011) (requiring that agencies conduct

“retrospective analyses of existing regulations”).

53

Retrospective Review, U.S. ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY, http://www.epa.gov/regdarrt/retrospective/ (last visited Oct.

14, 2011).

11

Figure 3: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Reg DaRRT: List of Rules

Source: http://yosemite.epa.gov/opei/RuleGate.nsf/content/allrules.html?opendocument (last visited Oct. 14, 2011)

Many other agency websites contain pages dedicated to regulations. The CFTC and

EPA’s sites are distinctive, though, in that they provide an easily accessible but comprehensive

list of the agencies’ proposed rules. The Department of Labor’s website, by way of contrast,

includes a page devoted to regulations where users can find links to the Department’s regulatory

agenda and other helpful information (Figure 4). The “featured items” on the page include only

a subset of actions from the agency’s regulatory agenda, presumably ones that agency managers

think will be of the greatest interest to the public.

54

Only toward the bottom of the webpage,

does a box appear that is labeled “Other Regulations Currently Open for Comment;” it contains

listings for three rulemakings.

54

Regulations, U.S. DEP’T OF LABOR, http://www.dol.gov/regulations (last visited July 17, 2011).

12

Figure 4: U.S. Labor Department Regulations Webpage

Source: http://www.dol.gov/regulations/ (last visited July 17, 2011)

B. Social Media

Social media may provide agencies with a potentially powerful tool for “get[ting] public

input on pending proposed rules in the early planning stages,” as suggested by Professor Beth

Noveck, former United States Deputy Chief Technology Officer and former director for the

White House Open Government Initiative.

55

Social media tools include blogs, Facebook,

Twitter, IdeaScale, and other online discussion platforms.

56

These tools have raised some

questions about how best to deal with privacy and security concerns as well as how to handle

55

Alice Lipowicz, Use Digital Tools for Better Rulemaking, Former Official Advises, FED. COMPUTER WK. (Jan. 26,

2011), http://fcw.com/Articles/2011/01/26/Former-White-House-deputy-CTO-advises-immediate-actions-for-

improved-erulemaking.aspx.

56

Id.

13

records management and Freedom of Information Act requests.

57

Nevertheless, agencies

increasingly use them for diverse purposes.

For example, the Department of Agriculture Forest Service recently published a proposed

Forest Planning Rule which it had developed with the assistance of a dedicated website and blog

(Figure 5).

58

The Forest Service created a website solely for this rulemaking on which it posted

announcements, news releases, and other relevant information.

59

To create a forum for public

deliberation, the Forest Service also created a blog on which users could offer input.

60

Although

comments on the blog were not considered “official formal comments,” the Service encouraged

participation and received over 300 comments via the blog that helped inform the proposal

development.

61

Federal agencies have turned also to more popular online platforms, such as Facebook and

Twitter. Facebook allows users to sign up and create what is effectively their own personal

webpage.

62

Each Facebook page has its own web address and contains information its owner

wishes to allow other users to view, including updates displayed on a virtual “wall.”

63

Visitors

to a personal profile can post messages on the wall that are visible to both the owner and other

visitors.

64

Owners and visitors can also post pictures, videos, and links to other websites.

65

Although originally intended for individual persons, Facebook now is a popular venue for

commercial, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. For example, the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) maintains an active Facebook page, updating its wall almost daily with

links to news articles, photos submitted by members of the public, videos of projects by

university students, job postings, and other pieces of information.

66

Only on occasion, though,

does EPA post information on Facebook specifically pertaining to any of its rulemakings.

67

Twitter allows users to post and receive short messages known as “tweets.”

68

A user may

choose to “follow” other users’ tweets, receiving tweets whenever they are posted by way of a

customized page that lists the most recent tweets from the users that one is following.

69

Although tweets are limited to no more than 140 characters, they may contain links to other

57

GREGORY C. WILSHUSEN, U.S. GOV’T ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE, GAO-10-872T, INFORMATION MANAGEMENT:

CHALLENGES IN FEDERAL AGENCIES’ USE OF WEB 2.0 TECHNOLOGIES 1 (2010), available at http://www.gao.gov/-

new.items/d10872t.pdf.

58

Planning Rule, U.S. DEP’T OF AGRIC., http://fs.usda.gov/planningrule (last visited June 17, 2011).

59

Id.

60

Forest Service Planning Rule Blog, U.S. DEP’T OF AGRIC., http://planningrule.blogs.usda.gov (last visited June 17,

2011).

61

Collaboration & Public Involvement, U.S. DEP’T OF AGRIC., www.fs.usda.gov/goto/planningrule/collab (last

visited July 13, 2011). The blog elicited only somewhat more than 300 comments, while the total number of

comments received overall, through means other than the blog, exceeded 300,000. Forest Service Planning Rule

Blog, supra note 58.

62

FACEBOOK, http://www.facebook.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

63

Id.

64

Id.

65

Id.

66

U.S. Envtl. Prot. Agency, FACEBOOK, http://www.facebook.com/EPA (last visited June 6, 2011).

67

Id.

68

TWITTER, http://twitter.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

69

Id.

14

Figure 5: U.S. Forest Service Forest Planning Rule Blog

Source: http://planningrule.blogs.usda.gov/ (last visited July 17, 2011)

media, such as websites, photos, and videos.

70

One advantage of tweets’ limited size is that they

can be transmitted through both computers and handheld devices, allowing instantaneous and on-

the-go access to information.

71

Numerous regulatory agencies use Twitter. The EPA, for

example, maintains numerous Twitter accounts, ranging from EPAnews (for press releases),

72

EPAgov (for general announcements),

73

and EPAresearch (for research announcements),

74

not to

mention accounts for EPA’s various regional offices.

75

The Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC) similarly has a news account, SEC_News,

76

as well as an account for

information related to legal filings, SEC_Litigation.

77

70

Id.

71

Id.

72

EPAnews, TWITTER, http://twitter.com/EPAnews (last visited June 14, 2011).

73

EPAgov, TWITTER, http://twitter.com/EPAgov (last visited June 14, 2011).

74

EPAresearch, TWITTER, http://twitter.com/EPAresearch (last visited June 14, 2011).

75

See, e.g., EPAregion3, TWITTER, http://twitter.com/EPAregion3 (last visited June 14, 2011).

76

SEC_News, TWITTER, http://twitter.com/SEC_News (last visited June 14, 2011).

77

The Twitter account SEC_Litigation was removed during the writing of this report. For a similar SEC Twitter

account, see SEC_Enforcement, T

WITTER, http://twitter.com/SEC_Enforcement (last visited June 14, 2011).

15

Ideascale is a web-based “crowdsourcing” software that government agencies have

started to use to structure public input and dialogue.

78

The software allows users to post their

ideas to a webpage where other users can discuss and vote on these ideas.

79

The software keeps

track of which ideas received the most votes and discussion, and then ranks the discussions and

ideas according to popularity.

80

The most popular ideas are automatically placed at the top of

the page.

81

The White House has used IdeaScale to develop its agenda for its Open Government

Initiative;

82

the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has used it in developing its

National Broadband Plan;

83

and the Department of Labor (DOL) has used it to obtain public

suggestions and comments on proposed regulations.

84

The White House is currently in the process of creating what it considers a “next

generation public engagement platform,” known as ExpertNet.

85

True to its billing, the platform

is being developed using public input provided through a wiki set up by the White House.

86

The

platform is intended to facilitate a structured dialogue by allowing government officials to post

discussion topics on current policy concerns and by attracting contributions from experts.

C. Government-Wide Websites and Resources

As already noted, Regulations.gov, which is managed by EPA, provides online access to

regulatory documents prepared by or submitted to agencies from across the federal govern-

ment.

87

Members of the public can also submit comments on proposed rules via Regulations.

gov.

88

The homepage of Regulations.gov now shows users which regulations have garnered the

most comments and also lists newly posted regulations and regulations with open comment

periods.

89

The site contains both simple

90

and advanced

91

search options.

A separate website, Reginfo.gov, serves as the online location of the Unified Agenda of

Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions – otherwise known as the semiannual regulatory

agenda because it is published twice every year, once in the spring and once in the fall.

92

The

78

IDEASCALE, http://ideascale.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

79

Id.

80

Id.

81

Id.

82

Open Government Dialogue, IDEASCALE, http://opengov.ideascale.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

83

Broadband.gov, IDEASCALE, http://broadband.ideascale.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

84

Dep’t of Labor Reg. Rev., IDEASCALE, http://dolregs.ideascale.com (last visited June 6, 2011).

85

David McClure, Expert Net: Two More Weeks to Weigh In, THE WHITE HOUSE (Jan. 6, 2011, 2:53 PM),

http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/01/06/expertnet-two-more-weeks-weigh.

86

Id.; See also Expert Net, WIKISPACES, http://expertnet.wikispaces.com/Getting+Started (last visited June 6, 2011).

87

REGULATIONS.GOV, http://www.regulations.gov (last visited June 8, 2011). Regulations.gov reports that “there

are nearly 300 agencies whose rules and regulations are posted to [the site].” See About Us, R

EGULATIONS.GOV,

http://www.regulations.gov/#!aboutPartners (last visited Oct. 3, 2011).

88

REGULATIONS.GOV, supra note 87.

89

Id.

90

Id.

91

Advanced Search, REGULATIONS.GOV, http://www.regulations.gov/#!advancedSearch (last visited June 8, 2011).

92

REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov (last visited June 8, 2011).

16

agenda contains lists of rulemakings for all federal agencies, sorted by stage of regulatory

development (e.g., proposed rules versus final rules).

93

Users can also search for rulemakings by

a Regulation Identifier Number (RIN), which is given to every rulemaking as it commences.

94

Reginfo.gov also dedicates a separate webpage – the “Regulatory Review Dashboard” –

to proposed rules currently under review by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

(OIRA).

95

The Dashboard uses pie charts and bar graphs to display data on the number of rules

by agency, rule stage, length of review, and economic significance.

96

This part of the site

includes its own search engine

97

and provides access to archives of OIRA’s past reviews.

98

In addition to Regulations.gov and Reginfo.gov, both of which are specifically devoted to

regulation, several other government-wide websites bear noting. FDsys.gov is the homepage of

the Federal Digital System (FDsys), operated by the U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO).

99

FDsys, a recent update of what had previously been known as GPO Access, makes legislative,

executive, and judicial documents available online.

100

At FDsys, for example, the user can find

an electronic archive of the Federal Register, the executive branch’s official publication and

published source of all proposed and final rules.

The “Federal Register 2.0” website, managed by the National Archives and Records

Administration (NARA) and GPO, provides a user-friendly interface to an online version of the

Federal Register.

101

Federal Register 2.0 contains search capabilities and, for rulemakings, a

timeline linking to all related Federal Register notices.

102

For proposed rules still open for

comment, Federal Register 2.0 provides a link to Regulations.gov, where a user may submit a

comment.

103

93

See, e.g., Agency Rule List – Fall 2010, REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/agencyRuleList (last

visited June 8, 2011).

94

Search of Agenda/Regulatory Plan, REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaSimpleSearch (last

visited June 8, 2011).

95

Regulatory Review Dashboard, REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/EO/eoDashboard.jsp (last

visited June 6, 2011).

96

Id.

97

Search of Regulatory Review, REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoAdvancedSearchMain (last

visited June 6, 2011).

98

Historical Reports, REGINFO.GOV, http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoHistoricReport (last visited June 6, 2011).

99

Federal Digital System, U.S. GOV. PRINTING OFFICE, http://www.fdsys.gov (last visited June 6, 2011).

100

Id.

101

FEDERAL REGISTER 2.0, http://www.federalregister.gov (last visited June 6, 2011). President Obama has

announced that the Federal Register will no longer be printed in hard copy but instead will only be issued

electronically. Robert Jackel, Federal Register Will No Longer Be Printed, Obama Says (June 22, 2011), available

at http://www.law.upenn.edu/blogs/regblog/2011/06/federal-register-will-no-longer-be-printed-obama-says.html.

102

See, e.g., Hazardous Materials: Requirements for Storage of Explosives During Transportation, FEDERAL

REGISTER 2.0, http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2011/06/07/2011-13837/hazardous-materials-requirements-

for-storage-of-explosives-during-transportation (last visited June 8, 2011).

103

See, e.g., Petition Requesting Safeguards for Glass Fronts of Gas Vented Fireplaces, FEDERAL REGISTER 2.0,

http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2011/06/08/2011-14020/petition-requesting-safeguards-for-glass-fronts-of-

gas-vented-fireplaces (last visited June 8, 2011).

17

Finally, HowTo.gov provides a series of “best practice” guidelines for agencies in their

development of websites, use of social media, and operation of contact centers.

104

A “Tech

Solutions” section of this site showcases technological innovations and explains how agencies

can use them to improve their websites and other IT operations.

105

HowTo.gov is the product of

the Federal Web Managers Council, a group of senior government web managers organized

under the auspices of the General Services Administration (GSA).

106

The Web Council issues

guidelines and recommendations aimed at “increas[ing] the efficiency, transparency,

accountability, and participation between government and the American people.”

107

D. Nongovernmental Websites on Federal Rulemaking

In addition to governmental websites, several nongovernmental websites deserve

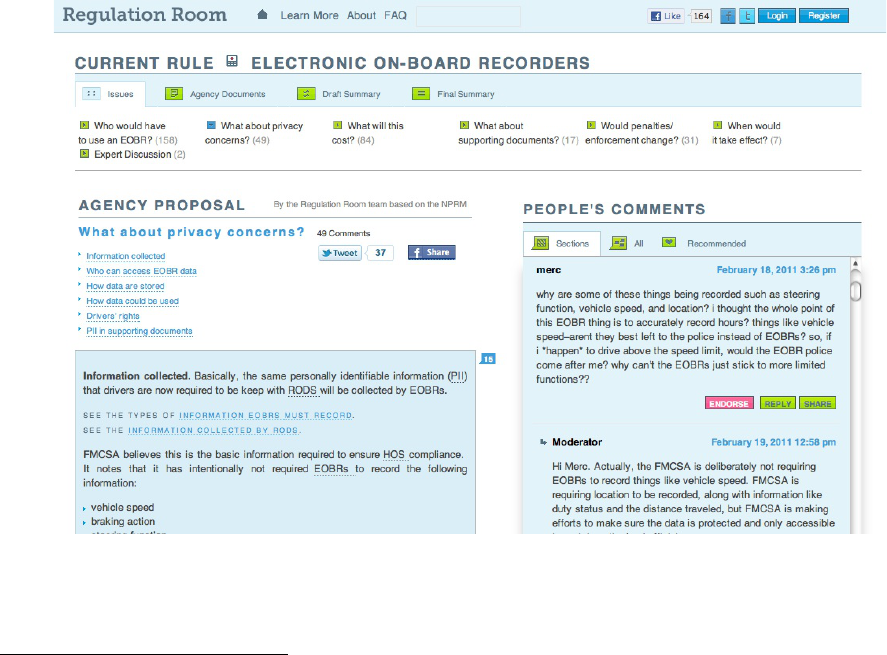

mention. The Regulation Room

108

is an e-rulemaking pilot program co-sponsored by the

Department of Transportation and Cornell University that seeks to complement Regulations.gov

(Figure 6).

109

Although the Regulation Room website supports public dialogue over selected

DOT rulemakings, it is not an official governmental site.

110

Users can submit comments and ask

questions about a proposed DOT rule, and then their comments are synthesized and submitted as

an official comment.

111

To date, Regulation Room has facilitated public discussion on a

proposed rule that would ban texting by truckers and on another proposed rule that would force

the disclosure of airline baggage fees.

112

OpenRegs.com is a private website that allows users to locate recently proposed and

recently promulgated regulations.

113

Maintained by a research fellow at the Mercatus Center at

George Mason University in collaboration with a web editor, OpenRegs.com claims to provide a

more usable alternative to Regulations.gov and agency docket databases.

114

The site lists both

proposed regulations and final regulations after they are published in the Federal Register.

115

Visitors may sort through these announcements by agency, topic, or date of publication.

116

For

proposed rules, the homepage also allows users to sort proposals by the comment period, finding

104

HOWTO.GOV, http://www.howto.gov (last visited June 6, 2011).

105

Tech Solutions, HOWTO.GOV, http://www.howto.gov/tech-solutions (last visited June 8, 2011).

106

Federal Web Managers Council, HOWTO.GOV, http://www.usa.gov/webcontent/about/council.shtml (last visited

June 6, 2011).

107

Federal Web Managers Council, Putting Citizens First: Transforming Online Government, HOWTO.GOV, 1

(November 2008), http://www.usa.gov/webcontent/documents/Federal_Web_Managers_WhitePaper.pdf.

108

REGULATION ROOM, http://regulationroom.org (last visited June 6, 2011).

109

Alice Lipowicz, DOT e-Rulemaking Pilot Project Encounters Minor Glitch, FED. COMPUTER WK. (Feb. 2, 2011),

http://fcw.com/articles/2011/02/02/dot-erulemaking-pilot-project-encounters-minor-glitch.aspx.

110

About, REGULATION ROOM, http://regulationroom.org/about (last visited June 6, 2011).

111

Id.

112

Id.

113

OPENREGS.COM, http://openregs.com (last visited June 8, 2011).

114

About, OPENREGS.COM, http://openregs.com/about (last visited June 8, 2011).

115

OPENREGS.COM, supra note 113.

116

Id.

18

Figure 6: Regulation Room

Source: http://regulationroom.org/ (last visited June 10, 2011)

proposals with comment periods that have recently opened or periods that soon will close.

117

Through RSS feed and email subscription features, users can be updated on new proposals.

118

OpenRegs.com also includes options for commenting and tweeting,

119

an editor’s blog,

120

and an

iPhone app.

121

A website for researchers and analysts interested in the use of electronic media in

rulemaking can be found at E-Rulemaking.org, a website maintained by the Penn Program on

Regulation at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

122

E-Rulemaking.org contains

research papers, government reports, news accounts, and links to governmental and

nongovernmental websites related to information technology and the regulatory process.

117

Id.

118

Using This Site, OPENREGS.COM, http://openregs.com/learn/site (last visited June 8, 2011).

119

See, e.g., Cotton Board Rules and Regulations: Adjusting Supplemental Assessment on Imports, OPENREGS.COM,

http://openregs.com/regulations/view/108895/cotton_board_rules_and_regulations_adjusting_supplemental_assess-

ment_on_imports (last visited June 8, 2011).

120

Open for Comment, OPENREGS.COM, http://blog.openregs.com (last updated Jan. 26, 2010).

121

iPhone, OPENREGS.COM, http://openregs.com/iphone (last visited June 8, 2011).

122

E-Rulemaking, http://www.law.upenn.edu/academics/institutes/regulation/erulemaking/ (last visited July 13,

2011). As the faculty director of the Penn Program on Regulation, I created E-Rulemaking.org and oversee its

maintenance.

19

III. Systematic Analysis of Agency Websites and Rulemaking

As the review in Part II has illustrated, agencies across the federal government – and even

a few entities outside of government – are using electronic media in a variety of ways to inform

and engage with the public over rulemaking. The most dominant method, of course, has been to

provide information on an agency website, which has become each agency’s “front door” to the

public.

123

Just as the website has increasingly become the face of retail business, it has

increasingly become the face of government. Accordingly, public officials and scholars looking

to assess the quality of government in the digital age have increasingly turned to the website as

their object of study.

124

For the purpose of informing any recommendations on the use of

electronic media to support rulemaking, it was necessary first to review past research on agency

websites and then to undertake to study the current state of agency websites, particularly with

rulemaking in mind, to identify patterns and gaps in current practices. This Part reports the

results of a study of 90 federal agency websites which provides a foundation upon which to base

recommendations for improvement.

A. Past Research

In one of the earliest studies of agency websites, Genie Stowers issued a report in 2002

ranking federal agency websites based on their features,

125

noting in particular a lack of attention

to websites’ accessibility to the disabled.

126

The Congressional Management Foundation also

conducted a study of websites for each Member of Congress in 2002, giving each site a grade

based on a scorecard of qualities such as “audience, content, interactivity, usability, and

innovations.”

127

A few years later, a study on digital government by Brooking Institution scholar

Darrell West singled out the website for analysis, studying legislative, executive, and judicial

websites at both the federal and state levels in the United States.

128

West found that, at least as

of 2005, “many government websites [were] not offering much in the way of online services.”

129

Since 2002, the United Nations (UN) has annually assessed government websites around

the world.

130

The UN has specifically examined “how governments are using websites and Web

portals to deliver public services and expand opportunities for citizens to participate in decision-

making.”

131

Based on the latest survey, conducted in 2010, the United States appears to have

made progress since the time of West’s study. The U.S. ranked second to Korea across the world

in terms of overall quality of e-government,

132

a measure which takes into account the online

123

See Telephone Interview, supra note 4 and accompanying text.

124

See infra Part III.A.

125

Genie N. L. Stowers, The State of Federal Websites: The Pursuit of Excellence, THE BUSINESS OF GOVERNMENT,

23 tbl.4 (August 2002), http://www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/FederalWebsites.pdf.

126

Id. at 19.

127

NICOLE FOLK ET AL., CONGRESSIONAL MANAGEMENT FOUNDATION, CONGRESS ONLINE 2003: TURNING THE

CORNER ON THE INFORMATION AGE 3 (2003).

128

DARRELL M. WEST, DIGITAL GOVERNMENT (2005).

129

Id. at 69.

130

STEPHEN A. RONAGHAN, U.N. DEP’T OF ECON. & SOC. AFFAIRS AND AM. SOC’Y FOR PUB. ADMIN.,

B

ENCHMARKING E-GOVERNMENT: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE (2002), available at http://unpan1.un.org/-

intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan021547.pdf.

131

U.N. DEP’T OF ECON. & SOC. AFFAIRS, supra note 41, at 59.

132

Id. at 60.

20

availability of government services, the extent and penetration of the Internet and

telecommunications technology across the country, and the overall level of literacy and

educational attainment in the country.

133

The UN has separately studied each country’s “use of the Internet to facilitate provision

of information by governments to citizens (‘e-information sharing’), interaction with

stakeholders (‘e-consultation’), and engagement in decision making processes (‘e-decision

making’).”

134

On this measure, known as the “e-participation index,” the United States ranked

first in the world in the UN study released in 2008.

135

In developing a subsequent report, the UN

changed its method of indexing, such that in 2010 the U.S. ranked only 6

th

in the world in terms

of e-participation, a function both of a scoring of websites and of a scoring for “citizen-

empowerment.”

136

A separate UN assessment of just the “quality” of countries’ websites in

terms of e-participation placed the U.S. even somewhat lower in the rankings.

137

In addition to providing these overall rankings, the UN researchers asked about the

internal features or characteristics of government websites. For example, across the globe, the

UN found that “[s]ite maps can be found on slightly over 50 percent of national portals….

[despite a map being a] very useful feature [that] helps citizens to find pages on the website

without having to guess where information might be found.”

138

Just as the UN survey has compared U.S. government websites to government websites

in other countries, some recent research has sought to compare agency websites with commercial

ones. In a 2009 article, Forrest Morgeson and Sunil Mithas compared customer service survey

results from users of ten federal government websites with survey responses from users of

commercial websites.

139

They found that, compared with commercial websites, “e-government

Web sites are perceived by their own customers as less customizable, less well organized, less

easy to navigate and less reliable.”

140

Taken together, the existing research suggests that the U.S. federal government’s

websites rate better when compared to most other countries than they do to business websites. In

addition, the U.S. government perhaps may be doing less well in keeping up with the latest

features related to public participation in governmental decision making.

133

Id. at 109-13.

134

Id. at 113.

135

U.N. DEP’T OF ECON. & SOC. AFFAIRS, U.N. E-GOVERNMENT SURVEY 2008: FROM E-GOVERNMENT TO

CONNECTED GOVERNANCE, at 58, U.N. Doc. ST/ESA/PAD/SER.E/112, U.N. Sales No. E.08.II.H.2 (2008),

available at http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan028607.pdf.

136

U.N. DEP’T OF ECON. & SOC. AFFAIRS, supra note 41, at 85 & tbl.5.1.

137

The U.S. tied for seventh place on website quality, although due to ties, a total of 10 countries’ websites ranked

higher than the U.S. in terms of quality. Id., at 85.

138

Id. at 78.

139

Forrest V. Morgeson III & Sunil Mithas, Does E-Government Measure Up to E-Business? Comparing End User

Perceptions of U.S. Federal Government and E-Business Web Sites, 69 P

UB. ADMIN. REV. 740 (2009). The ten

agency websites were selected to provide a mix of “agencies delivering benefits, providing services, and performing

regulatory functions.”

140

Id. at 744.

21

B. Rulemaking and Agency Websites

The existing research, however, has focused on agency websites in general, and not

specifically on websites in connection with agency rulemaking. To fill this gap, I co-authored a

study, released in July, 2007, that measured website features specifically related to agency

rulemaking.

141

Until that time, most of the research on e-rulemaking focused on ways to use the

Internet to allow the electronic submission of public comments, ranging from the advent of email

submission of public comments to the one-stop, government-wide comment funnel,

Regulations.gov.

142

Other scholarship at the time tended to play out scenarios by which digital

government would “transform” or “revolutionize” the relationship between the public and

agency decision makers.

143

My co-author, Stuart Shapiro, and I conducted our study on the premise that any such

transformation would presumably begin with the ubiquitous agency website. We selected 89

federal regulatory agency websites to study, drawing on all agencies that had completed more

than two rules per cycle during the preceding two years.

144

We recruited graduate students to

code each agency website according to a uniform protocol we created. The protocol was

designed to collect website information in three broad categories: (1) the ease of finding the

agency’s website, such as by typing in the agency name or acronym directly or using Google; (2)

general website features, including the presence of a search engine, a site map, help or feedback

options, other languages, and disability friendly features; and (3) the availability and access to

regulatory information, such as the kind of information the public could otherwise find in a paper

rulemaking docket.

145

Although we learned that agency websites could be easily located,

146

the general features

of agency websites were not as consistently favorable. Search engines were present on the home

pages of almost all of the agency websites, and user feedback and help features could be found

on a majority of sites, but less than half of the sites were readable in a language other than

English and only 4 of the 89 sites surveyed had what we deemed “disability friendly” features.

147

More notably, regulatory information was too often lacking. Although more than half of the

websites included one or more words related to rulemaking on the home pages (e.g., “rule,”

“rulemaking,” “regulation,” or “standard”), other key words related to participation in

rulemaking – like “comment,” “Proposed Rules,” and “docket” – could not be found on most of

the home pages.

148

141

Stuart Shapiro & Cary Coglianese, First Generation E-Rulemaking: An Assessment of Regulatory Agency

Websites (Univ. of Pa. Law Sch. Pub. Law & Legal Theory Research Paper Series, Paper No. 07-15, 2007),

available at http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=980247.

142

Balla & Daniels, supra note 18.

143

Beth Simone Noveck, The Electronic Revolution in Rulemaking, 53 EMORY L.J. 433, 433 (2004); Stephen M.

Johnson, The Internet Changes Everything: Revolutionizing Public Participation and Access to Government

Information Through the Internet, 50 A

DMIN. L. REV. 277, 320 (1998).

144

Shapiro & Coglianese, supra note 141, at 3. We determined the frequency of rulemaking by examining five

issues of the semiannual regulatory agenda published in the Federal Register.

145

Id. at 2-3.

146

Id. at 3.

147

Id.

148

Id. at 3-4.

22

Strikingly, rulemaking dockets either did not exist online or were not easy to locate. Our

study had been conducted before the government-wide adoption of the Federal Docket

Management System that underlies Regulations.gov, so online dockets at that time, if they

existed, would have been found on agency websites. Only 44% of the agencies surveyed had a

link to some type of docket on their home page.

149

Dockets were found on the site maps of only

three agencies’ websites, and the coders could find dockets on only two additional sites through

the use of the website’s search engine.

150

When we gave student coders two additional minutes

per website to locate the docket by whatever means possible, they could find only seven

additional dockets.

151

We also compared websites across different agencies. We ranked agencies based on

three scores: (1) the ease of finding the website and the general website characteristics; (2) the

regulatory content on the website; and (3) the sum of the first and second scores.

152

We found

that those agencies that promulgated more rules tended to have websites that were slightly easier

to find, but they did not tend to have sites with more features.

153

Remarkably, we found no

major difference between the two groups in terms of the accessibility of regulatory information –

with the one exception being that it was actually easier to find a link to a docket for agencies that

regulated less frequently.

154

We concluded that agency websites had much untapped room for improvement. We

urged greater attention be given to websites as an important mediating juncture between the

public and the agency with respect to rulemaking, suggesting that “at the same time scholars and

government managers justifiably focus on new tools, some thought also be given to standards or

best practices for the accessibility of regulatory information on the first generation tool, the

worldwide web.”

155

C. Agency Websites and Social Media Today

To help inform the Administrative Conference of the United States (ACUS)

consideration of recommendations about agencies’ current use of the Internet in support of

rulemaking, I undertook to replicate and extend my earlier study in order to determine whether

agencies had made progress in the intervening years and to identify both new developments and

any new concerns. This second study, conducted in March 2011, followed the earlier study in its

design and in most of the coding protocols, but it also included additional coding for agency’s

use of social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, which were not in widespread use at the time

data were collected for the earlier study (November 2005).

149

Id. at 3.

150

Id.

151

Id.

152

Id. at 5.

153

Id. at 4.

154

Id. For 46 agencies from which we could obtain reliable data on their number of employees, we analyzed

whether website features varied according to agency size. We found no clear pattern in our results relating to

agency size.

155

Id. at 6.

23

As with the earlier study, I drew upon the semiannual regulatory agenda for the sample of

agencies to include in the study. Out of about 180 agencies reporting some final rulemaking

over the course of the previous two years (2009-2010), a total of 90 agencies were included in

the study because they reported an average of two or more rulemakings completed during each

six-month period covered by the agenda.

156

Sixteen law students coded the websites on a single

day in March 2011, each using a uniform coding protocol and following a collective training

session. Each coder separately collected data on two websites – the Federal Communications

Commission and the Department of Transportation – to measure intercoder reliability (.93).

157

1. General Website Characteristics

For the most part, coders again had no difficulty finding the agency webpage. As in the

earlier study, Google not surprisingly enables users to find government agencies easily by name

or acronym. In at least two cases – the Rural Utility Service and the Minerals and Management

Service – coders encountered difficulty because the agencies had been disbanded or merged into

other agencies at the time of the coding – even though they had appeared in the latest version of

the semiannual regulatory agenda.

158

The Minerals Management Service, for example, had been

folded into a new entity known as the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and

Enforcement following the Gulf Coast oil spill in 2010.

Once at the website, coders started coding at the homepage, checking first for general

website features. Of the 90 websites coded:

• 89 agency websites displayed a search engine

• 79 websites included some facility to ask a question or provide feedback

• 70 agency websites included a link to site index/site map on the homepage

• 26 websites offered what the coders considered a clear disability-friendly feature,

such as text equivalents for non-text features (as opposed to a general statement of

policy on accessibility to the disabled)

The use of each of these navigational aids increased in the five years since the previous study.

However, fewer sites than before included a text-only option (only 3 out of 90, as opposed to 9

out of 89 in 2005). About the same number of websites (32 out of 90) provided translations in

languages other than English as in 2005, and of these 32 sites seven provided multiple non-

English language options.

156

Some of these “agencies” were actually sub-agencies or offices within cabinet level departments or other larger

agencies. In the case of the Environmental Protection Agency, the listings in the Regulatory Agenda refer to statutes

administered by the agency (e.g., “Clean Air Act”), so effort was made where possible to find the corresponding

office (e.g., “Office of Air and Radiation”) and code its portion of the EPA website. About 10 entries from the

regulatory agenda listings that would otherwise have qualified for inclusion were excluded because either they were

not really agencies (e.g., “procurement regulation”) or were effectively coterminous with agencies already included

(e.g., “Department of Homeland Security Office of the Secretary”).

157

In addition, Stuart Shapiro, one of the coauthors of the 2007 study, duplicated the work of each of the student

coders for one agency website each.

158

In such a case, the coders reviewed and recorded data for the new agency’s website.

24

This time, coders looked for links to various policy statements. Almost every website (89

of 90) included a link to a privacy policy, but only 39 included a link to “Open Government,” an

initiative of the Obama Administration that calls upon agencies to develop plans for improving

transparency and public participation. In only 29 instances could coders find an agency policy

on the treatment of public comments, such as guidelines about impermissible content (obscenity

or profanity, commercial endorsements) or agency policies about the posting of comments.

2. Social Media

Social media – or Web 2.0 features – have definitely secured a foothold use among

regulatory agencies, but they remain far from ubiquitous. Of the 90 websites coded:

• 21 contained a link for learning more about the agency’s social media presence

• 32 included a listserv subscription for email updates

• 55 provided a general RSS “feed” option, whereas only 4 provided a feed specifically

devoted to rulemaking

• 31 displayed a link to a general blog

o 14 blogs were used for postings by the agency head

o Only one agency could be found that had a blog specifically devoted to

rulemaking

• 39 websites featured a link to Facebook, but only 18 of these agency Facebook pages

mentioned at least one word related to rulemaking in a posting (i.e., rule, regulation,

rulemaking, standard, law, legislation, or statute)

• 43 websites contained a link to Twitter, with only 17 having a tweet that mentioned at

least one of the specified words related to rulemaking

• 43 websites included a link to YouTube, a commercial site for posting videos

• 24 linked to Flickr, a commercial site for posting photos

• 14 websites included links to other social media applications, including 4 that link to

MySpace, a less popular version of an online community like Facebook

• 31 websites provided podcasts, or online audio recordings

• 14 agencies had an option to download a widget (or small software application), although

coders failed to find any of these widgets directly relevant to rulemaking

• 7 websites provided an option to receive cell phone updates of some kind

Overall, these findings indicate that a sizeable portion of agencies – but by no means a majority –

have started to make use of social media. However, even among those agencies that are using

social media, they do not yet use these Web 2.0 tools much in connection with their rulemaking.

3. Rulemaking Information

Agencies admittedly have many governmental responsibilities beyond just rulemaking, so

their needs for communication on their websites also obviously range beyond just rulemaking.