Recommendations to Strengthen the Resilience of New

Jersey’s Nursing Homes in the Wake of COVID-19

June 2, 2020

PROJECT BACKGROUND

2

Rapid Assessment of NJ’s COVID-19 Response for LTC

• In response to the growing impact of COVID-19 on nursing home residents and staff, in early May, the New Jersey Department of Health (DOH)

engaged Manatt Health (Manatt) to undertake a rapid assessment of the state’s COVID-19 response targeted toward the long-term care (LTC)

system.

• Manatt was charged with providing the state with a set of actionable recommendations over the near-term and intermediate to longer-term

aimed at improving the quality, resilience and safety of the state’s LTC delivery system now and for the future.

• Over the three-week project, Manatt undertook a review of relevant literature, conducted a data review, evaluated national best practices and

actions taken in other states, and conducted over fifty interviews with stakeholders from:

• New Jersey state government

• New Jersey associations

• New Jersey labor representatives

• New Jersey nursing homes

• New Jersey consumer and advocacy groups

• National experts

• Other states

• Based on this assessment, this report presents a series of recommendations over the near-term (next 4 months) and intermediate to longer-

term (5+ months) to:

• Strengthen emergency response capacity

• Stabilize facilities & bolster workforce

• Increase transparency & accountability

• Build a more resilient & higher quality LTC system

Context

3

This report was updated on 6/4/2020 to correct minor typos. The content of the report did not change.

Comment on Limitations

• This report was developed over a three-week period when the COVID-19 landscape in New Jersey was changing rapidly. The

recommendations in this report are informed by the most up-to-date information at that point in time, but Manatt recognizes that

week to week – and often day by day – there are new developments and information relating to the COVID-19 crisis.

• The primary focus of this report is skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), nursing facilities and special care nursing facilities (collectively

referred to in this report as nursing homes) licensed by the state of New Jersey, rather than the full range of congregate care settings

that operate in the state. Additional work may be done to identify which of these recommendations can be extended to those care

settings. The term “LTC facilities” is used when recommendations apply to facilities beyond nursing homes.

• While this report is about nursing homes, the people who reside in nursing homes have diverse needs. They include people with both

short- and long-term stays, and people with dementia, serious mental illness, traumatic brain injury and intellectual/developmental

disabilities.

• Because this report was developed during statewide “stay-at-home” orders and while nursing home visitation was restricted, Manatt

did not conduct any in-person visits to nursing homes. Instead, Manatt held video and telephonic calls with many stakeholders,

including a sampling of facilities, as well as trade associations, labor representatives, consumer advocates and many others. In the

future, in-person visits could further inform these recommendations.

• This report highlights a set of recommendations deemed to be high-impact actions that the State can take. It does not represent the

full spectrum of actions and improvements that the state may want to consider. Many of the recommendations in this report are

interdependent.

• Importantly, implementation of many of these recommendations will require further planning, and statutory or regulatory changes,

and many of these recommendations will require additional funding.

4

CONTEXT

5

COVID-19 Has Shone a Light on Heroes

Throughout COVID-19, we have seen unsung heroes who have stepped

up to an extraordinary degree—including many government leaders and

staff and nursing home administrators. Most notably, the front-line staff

in nursing homes, who placed their own health and the health of their

families at risk, deserve our recognition and gratitude.

6

Despite efforts to manage spread of coronavirus in NJ and elsewhere, COVID-19 fed on and exposed

weaknesses in our health care system, perhaps most notably in our nursing homes.

How Did We Get Here?

• As the outbreak unfolded, the situation was rapidly

changing on the ground, which impacted both the federal

and state responses.

• Similar to other states, New Jersey’s initial preparedness

coordination was more focused on external threats to the

state, with an emphasis on responding to the risk from

international travel.

• New Jersey quickly pivoted to focusing on the health care

delivery system response focus, though—as was true in

many states—with greater emphasis on inpatient hospital

surge capacity planning and support. The focus on

hospitals prompted the prioritization of the distribution of

supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE) and other

resources to that sector.

• DOH released a series of

guidance directed toward LTC

facilities beginning on March 3* and began to distribute

some PPE to nursing homes later in the month.

The Situation and Challenges

Are Not Unique to New Jersey

New Jersey Was Hit Early and Hard

• New Jersey had its first diagnosed COVID-19 case on March 4; at that time, testing was

scarce and the

testing and spread-risk was focused on symptomatic people. Along with the

broader New York City metropolitan area, cases rapidly increased in March.

• Likely due to its proximity to New York City and density, New Jersey ranks second nationally

behind New York in cases (160,918) and deaths (11,721) as of June 2.

*See Appendix on state actions addressing COVID-19 in nursing homes.

NY

376,520

(21%)

NJ

160,918

(9%)

Rest of US

1.16

million

(70%)

COVID-19 Cases

Share of US Population

NY

6%

NJ

3%

Rest of US

91%

7

Source: Manatt analysis of COVID-19 infection and death data file received from NJ DOH received on May 26, 2020; U.S. Census, Population Reference Bureau, “Annual

Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties in New Jersey: July 1, 2019”, data.census.gov

New Jersey’s outbreak peaked in late March through early April, with a substantial portion of the

population affected.

How Did We Get Here? (cont.)

8

Residents of nursing homes were particularly vulnerable.

Most tragically, high community spread in New Jersey brought

COVID-19 into New Jersey’s nursing homes.

How Did We Get Here?

(cont .)

• The state’s Wanaque Center for Nursing and

Rehabilitation had a serious, widely covered

viral outbreak among a particularly vulnerable,

specialized community of children using

ventilators just over a year ago.

• The Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington,

was the center of the first major U.S. COVID-19

outbreak, and nursing homes in Europe were

ravaged by the virus.

Nursing homes are hotspots for

infectious disease outbreaks and

were quickly hit by COVID-19

• New Jersey has many old facilities, many

with 3- and 4-bedded rooms.

• A large percentage of nursing homes in New

Jersey have documented infection control

deficiencies and citations.

• Nursing homes are staffed by workers who

are also subject to community spread; many

of whom came from communities with large

outbreaks.

Certain characteristics of New Jersey

nursing homes—which are not

unique to the State—put them at

particularly high risk of an outbreak

Nursing homes are

congregate settings

that are the home for

people prone to

infection with

weakened capacities

to fight back.

9

Why It Matters: Protecting our Families, Neighbors and Caretakers

People living in nursing homes are our mothers and fathers, our sisters and brothers, our aunts and

uncles, our grandparents and great-grandparents, our former teachers, our veterans and our neighbors.

Nursing Home Demographics

People Living in Nursing Homes

• On an average day, over 45,000 New Jerseyans—approximately 0.5% of the state

population—are residing in a nursing home.

• People living in nursing homes have their own preferences and must have agency in

decisions that impact their homes and lives.

• Nursing home residents are among our most vulnerable community members. Many

are over 85 years of age, and they may be disabled, medically frail or have mental

impairments.

• Nursing homes provide crucial medical, skilled nursing and rehabilitative care for

both short stays (such as on a post-operative basis) and LTC. People receiving short-

term v. long-term care in nursing homes have very different needs.

• In New Jersey, two or three individuals often share nursing home rooms. There is a

growing movement in New Jersey and throughout the country to modernize nursing

homes to make them more home-like and less institutional.

• People living in nursing homes long term are often without means and/or have spent

down most of their resources before turning to Medicaid, which is the primary payer

for nursing home services.

New Jersey Nursing Home Demographics 2018

Medicaid Medicare Other Total

Average Daily

Census

26,570 6,823 12,455 45,847

Average Length

of Stay (days)

365 31 81 102

As of February 2020, about 20,500 Medicaid beneficiaries residing in

nursing homes were enrolled in managed long term services and

supports (MLTSS) and 6,500 were in fee-for-service.

Note: Underlying data is state reported totals (methodologies may vary; as such should be considered illustrative only). This analysis excludes New York due to discrepancies with its data.

50%

60%

62%

67%

43%

New Jersey

Connecticut

Massachusetts

Pennsylvania

US

Share of COVID-19 Deaths in Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities

as of 5/22

*Includes deaths of residents in all LTC facilities

As of 6/2:

5,965

10

Why It Matters: Protecting our Families, Neighbors and Caretakers cont.

Nursing home staff working on the front lines, who continue to place their own health and the health

of their families at risk throughout COVID-19, deserve support and protection.

Nursing Home Staff

• 54,361 staff work in New Jersey nursing homes, including nursing staff, food, cleaning, and administrative

staff.

• Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) provide most of the care in nursing

homes. CNAs are the backbone of the staff and provide close to

90% of direct care, including bathing,

lifting, toileting and assistance with daily activities, to New Jersey’s nursing home residents.

• Chronic staffing shortages of CNAs and LPNs put additional pressure on overworked staff.

• Further, due to the low wages, many nursing home staff nationally and in New Jersey work

more than one

job

, sometimes across multiple nursing homes, sometimes shifting between hospitals and nursing homes

or other part-time jobs.

o In New Jersey,

CNAs make an average of $15/hour and LPNs make an average of $27.65/hour.

• Some facilities pay higher wages in lieu of benefit packages; some facilities pay lower wages with benefits.

13% of workers have no

health insurance.

• The overwhelming majority of the New Jersey nursing home direct care workers are women who are racial

or ethnic

minorities. Half are immigrants.

• CNAs have experienced the same childcare and family care obligations during the pandemic that are

exacerbated when schools and child care are closed and family members are ill as everyone else – but like

all frontline responders, they cannot work from home.

Spotlight on NJ Direct Care Workforce

• CNAs: 15,606

• LPNs: 5,603

• RNs: 4,900

• Women: 91%

• Racial or Ethnic Minorities: 84%

o Black or African American: 61%

o Hispanic or Latino: 14%

o Asian or Pacific Islander: 7%

o Other: 2%

• Immigrants: 50%

NJ LTC Workers’ COVID-19 Status as of June 2

Cases 10,895

Deaths 107

11

COVID-19 Amplified Existing Systemic Issues

You cannot invent a system that works when a crisis hits; the system must already be in place.

Critical Themes

COVID-19 didn’t create the problem – it exacerbated the long-standing, underlying systemic

issues affecting nursing home care in New Jersey.

• Nursing homes were largely underprepared for the threat of a widespread infection and under-resourced due to long-standing staffing

shortages or low staffing ratios. Many had previously been cited for infection control deficiencies.

• There was room for improvement in bidirectional communications between nursing homes and DOH. Lapses on both sides may have

contributed to inconsistent compliance with DOH guidance.

• Nursing homes generally were not adequately tied into the larger system of care and typically do not have strong communications and

consult relationships and protocols with emergency departments. Further, there is often poor communication between nursing homes and

hospitals at the point of hospital admissions and discharges. In addition, there is a lack of interoperability between nursing home and hospital

electronic health records.

• Under-resourced state agencies did not have sufficient staff to deploy to facilities and conduct meaningful oversight prior to COVID-19.

o No LTC-focused preparedness plan was in place in the state prior to COVID-19 with respect to PPE, staffing back up plans or

communications from facilities to hospitals or families.

o Much of the oversight of nursing homes is highly prescribed by federal rules; the federal requirements are rigid, often resulting in paper

compliance and limited improvements.

• New Jersey’s LTC industry and its regulatory agencies were not equipped with the technological systems or the practiced processes to rapidly

collect and share data in support of the state’s public health response.

12

Person-Centered

Communication +

Collaboration

High Quality, Safe

Facilities

Aligned Regulatory

Oversight + Support

Emergency

Preparedness

Strong sense of purpose, mission and value

Technology-enabled and data-driven

Viable financial model(s)

Critical

enablers:

Regular communication

among and between patients,

families, employees, care

delivery partners, facilities

and regulators

Meaningful choice, with

access to supports to enable

living at home/preferred

residence as long as possible

Goals of care plans and

ongoing dialogue

Use of telehealth and

consumer-convenient

services and supports

Resident empowerment

and active engagement

around wellness

Key

elements:

Formal cross-agency

collaboration centered on LTC

Adequate staffing levels –

both overall and by skill level

Enhanced wages and benefits

to reduce turnover and

moonlighting and ensure

consistency

Modernized facilities with

more single rooms, updated

HVAC, broadband and IT

infrastructure

Strong infection control

policies and procedures.

Access to clinical expertise;

engaged clinical relationships

High degree of

transparency across system

Sufficient staff,

resources and expertise

state-level

Real-time use of data to

inform interventions,

educate public and hold

industry accountable

Payment aligned with

desired system outcomes

Clear emergency plans

at facility, regional and

state levels and defined

roles and responsibilities

Clear communications

plan

Ongoing training and

drills; learning system

with access to technical

assistance

Strong community

relationships

Culture of safety

Culture of quality

Meaningful forums for

stakeholders to provide input

and to participate in industry-

wide improvement

Culture of caring and

respect

Culture of problem-solving

Culture of accountability

More home-like and non-

institutional nursing homes

Clear bi-directional

family/caregiver channels

Elements of a High-Functioning, Resilient LTC System

Meaningful consequences

for consistently poor

performance

13

A Galvanizing Moment

While COVID-19 has shone a light on the structural deficiencies in how we provide and fund

LTC, it also presents an opportunity for meaningful change:

• LTC workers and facilities are on the frontline of the pandemic response.

• COVID-19 exposed weakness and vulnerabilities in the system that represent a tough—but not

insurmountable—set of challenges.

• Stakeholders across New Jersey have mobilized to support their neighbors and have collaborated in

new ways, demonstrating opportunities for greater alignment across the system.

• Policymakers and regulators have developed a clearer view of the key priorities for reform going

forward.

• Recovery from this crisis should be a catalyst for change, bringing together policymakers, providers,

community members and others to create a high-functioning, resilient LTC system.

14

Landscape Review

15

New Jersey’s Nursing Homes: Key Characteristics

Spotlight on New Jersey Nursing Homes

Total number of nursing homes 370

For-profit ownership 74%

Non-profit ownership 23%

Government owned 3%

Average number of residents per day per

nursing home

119

Bed occupancy rate 82%

Average number of beds per nursing home 145

Source: Manatt analysis of Nursing Home Compare data as of May 12th, 2020

Although New Jersey has a wide range of congregate care settings, including assisted living

facilities, veterans memorial homes, developmental centers, and group homes, this report

focuses primarily on nursing homes.

16

Infection Control Deficiencies in Nursing Homes

Approximately one-third of nursing homes surveyed by New Jersey in 2017 were cited for an infection

prevention and control deficiency.

Infection Prevention and Control Deficiencies Cited, by State, 2017

State Number of Surveyed

Nursing Homes

Number With an Infection

Prevention and Control Deficiency

Cited

Percentage of Surveyed Nursing Homes With an Infection

Prevention and Control Deficiency Cited

New Jersey 334 105 31.4%

Total Across U.S. 14,550 5,755 39.6%

Nursing Homes with Infection Prevention and Control Deficiencies Cited, by State, Aggregate of Surveys from 2013 through 2017

State Total Surveyed

Nursing Homes

2013-2017

Nursing Homes With

No Infection

Prevention and

Control Deficiencies

Cited

Nursing Homes With

Infection Prevention

and Control

Deficiencies Cited in

Only One Year

Nursing Homes With Infection

Prevention and Control

Deficiencies Cited in Multiple

Non-Consecutive Years

Nursing Homes With Infection

Prevention and Control

Deficiencies Cited in Multiple

Consecutive Years

New Jersey 374 95 (25%) 133 (36%) 55 (15%) 91 (24%)

Total Across U.S. 16,266 2,967 (18%) 4,309 (26%) 2,563 (16%) 6,427 (40%)

Source: Infection Control Deficiencies Were Widespread and Persistent in Nursing Homes Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic, GAO. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/707111.pdf

17

Distribution of COVID-19 Across New Jersey Nursing Homes: Early Observations

Based on available data, strong and consistent patterns between nursing home COVID-19 cases and deaths and potential predictive characteristics were

not immediately evident. Early observations included:

• The Central East, Central West, and South regions had fewer COVID-19 cases per 1,000 people and fewer nursing home cases per licensed bed

compared to the North East and North West; in other words, with some exceptions, the intensity of COVID-19 cases in nursing homes largely

mirrored their surrounding communities.

• Larger nursing homes have not had a higher rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases or deaths on a per licensed bed basis than smaller nursing homes.

• For-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes have had similar rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths per licensed bed (additional in-depth analysis

recommended); however, data were not available to consider for-profit and not-for-profit subgroups.

• An observed relationship has not been identified between the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Nursing Home Compare overall Star

rating or quality star ratings and total COVID-19 nursing home deaths per licensed bed in New Jersey. (Continuing evaluation is happening across the

industry, including new reporting requirements for direct reporting to CMS, and these issues are anticipated to receive much scrutiny in the coming

months.)

• Weak relationships – if any – have been observed between number of COVID-19 deaths per licensed bed and nursing home health and infection

control deficiencies given available data.

Key Takeaways

The early analytic results are based on Manatt’s analysis of available data, including the sources listed below.

• Nursing Home Compare data (https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html? – accessed, May 12, 2020)

• U.S. Census data (https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ - accessed, May 12, 2020)

• New Jersey LTC COVID-19 infection and death data

(

https://www.state.nj.us/health/healthfacilities/documents/LTCFacilitiesOutbreaksList.pdf - accessed, May 12, 2020)

• New Jersey COVID-19 dashboard data (https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/topics/covid2019_dashboard.shtml – accessed, May

22, 2020)

Manatt Health conducted an analysis of COVID-19 cases and deaths in New Jersey nursing homes reporting to CMS. These facilities were selected for in-depth review due to the availability

of information regarding Star ratings, survey results, licensed beds, health deficiencies, ownership status and staffing. The facility data from CMS were cross-walked to the New Jersey

COVID-19 dashboard for confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in LTC facilities as of May 22, 2020. See Appendix for additional details.

Note: On June 1, 2020, CMS released a first tabulation of survey data from the Nursing Home COVID-19 Data Source: CDC National Healthcare

Safety Network (NHSN). This data reflects data entered into the NHSN system by nursing homes as of May 24, 2020 and is anticipated to be

updated on a weekly basis. CMS reports this initial data tabulation is incomplete; only approx. 80% of facilities reported by the deadline. CMS

also notes that, as with any new reporting program, some of the data from their early submissions may be inaccurate as facilities learn a new

system. Of note, facilities may opt to report cumulative data retrospectively back to January 1, 2020, though no facility is required to report

prior to May 8, 2020. Therefore, some facilities may be reporting higher numbers of cases/deaths compared to other facilities, due to their

retrospective reporting. The availability of testing may impact the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases facilities report. Deaths in this data set

are only counted if they include a lab confirmation for COVID-19.

18

Notes: Chart presented for directional purposes only. Deaths reported by LTC facilities to DOH; deaths may not be lab confirmed. Total and nursing home-only deaths collected from separate data sources that may have

differences in data collection, compilation, and presentation methodologies resulting in slight deviations in totals by date when compared. Nursing home deaths only includes COVID-19 deaths attributable to nursing home

residents and nursing homes listed in the CMS Nursing Home Compare database. All other COVID-19 deaths, including nursing home staff deaths and those attributed to assisted living and non-Medicare/Medicaid certified

nursing homes are counted as “not nursing home.” Source: Manatt analysis of Nursing Home Compare data as of May 12th, 2020, U.S. Census data, Long Term Care Facility COVID-19 infections and deaths from New Jersey

as of May 22, 2020:

https://www.state.nj.us/health/healthfacilities/documents/LTC_Facilities_Outbreaks_List.pdf and the New Jersey COVID-19 dashboard

https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/topics/covid2019_dashboard.shtml ” as of May 22, 2020

By county, the percentage of total COVID-19 deaths that has occurred among nursing home residents

has ranged from 14% to 69%.

High Percentage of NJ COVID-19 Deaths Have Been in Nursing Homes

19

Anecdotes From the Field: Responses Were Inconsistent During COVID-19

Some facilities with 3- and 4-bedded rooms moved

patients closer together because they were so seriously

short-staffed. Their intention was to improve safety and

deploy workforce more strategically but in hindsight, it was

the opposite of what should have happened.

“

”

A nursing home began lowering its daily census in

February, restricting congregate meals, increased wages of

nursing home staff and limited their ability to work at

multiple facilities, stockpiled PPE and brought in a nurse

educator on infection control. She did rounds with them to

see how staff was using PPE and made suggestions on how

they could improve their use of PPE.

“

”

A nursing home began to disseminate COVID-19

information to staff and residents/families, to screen

visitors and test and train staff on hygiene procedures in

the facilities in January. The nursing home also isolated

residents and staff upon a positive test, and paid workers a

bonuses to retain workforce.

“

”

A large, isolated facility operates van carpools to bring staff

in from a large city in Northern New Jersey (which happens

to be a high community outbreak region). Even if staff

isolated and practiced good infection control in the facility,

social distancing in large van carpools is impossible

.

“

”

Nursing homes had to quickly adapt their everyday operations to respond to the challenges presented by

COVID-19. In hindsight, some may have exacerbated outbreaks.

At the beginning of the crisis, the feelings among most staff were fear and panic. They weren’t provided training on infection control and use

of PPE, and guidance kept changing. Some employers were opting out of the paid sick leave made available under the federal emergency

legislation. So people were going to work even if they were sick because they needed to get paid. Some facilities loosened their attendance

policies, but some did not.”

”

“

Note: These anecdotes are drawn from Manatt interviews with stakeholders.

20

Recommendations

21

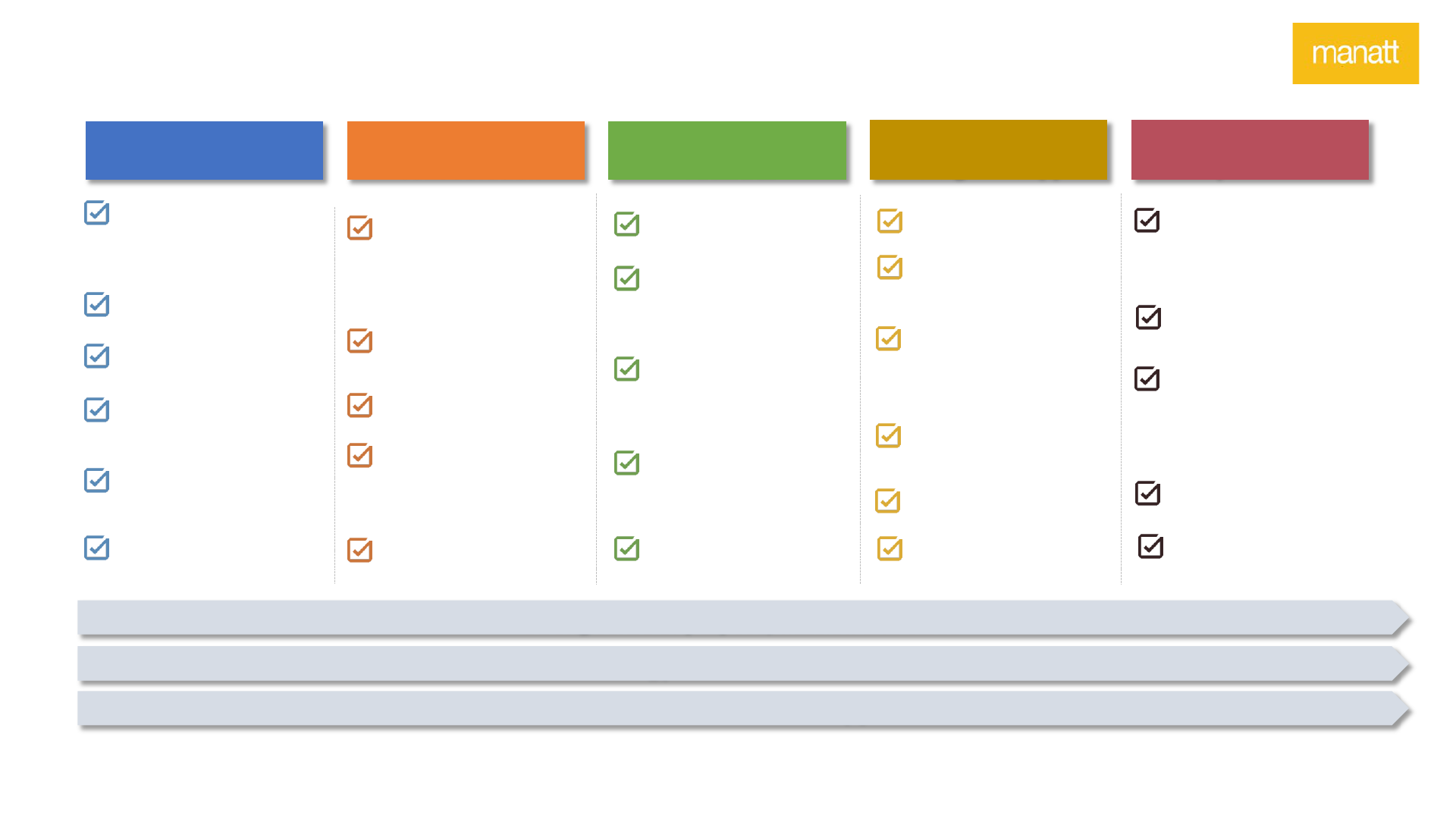

Recognize, Stabilize &

Resource the Workforce

Improve Oversight of and

Increase Penalties for Nursing

Homes

Consolidate and Strengthen

Response Through a Central

LTC Emergency

Operations Center

Implement “Reopening” Plan

and Forward-Looking Testing

Strategy

Strengthen Emergency

Response Capacity

Stabilize Facilities &

Bolster Workforce

Strengthen the ability to plan, coordinate

and execute effective responses to the

emergency and potential surges

Increase the responsibilities of and

support for New Jersey’s nursing homes

and their workers in the short and

longer-term

Increase Transparency &

Accountability

Build More Resilient &

Higher Quality System

Implement stronger mechanisms to

ensure a greater degree of accountability

and increase transparency through data

and reporting

Implement structures for stronger

collaboration and advance payment and

delivery reforms, including increasing

reliance on home- and community based

services (HCBS)

Institute COVID-19 Relief

Payments for Facilities &

Review Rates

Implement Strategy for

Resident & Family

Communications

Institute New Procedures to

Regulate and Monitor Facility

Ownership

Rationalize and Centralize LTC

Data Collection and Processing

Improve Safety and Quality

Infrastructure in Nursing

Homes

Strengthen State Agency

Organization and Alignment

Around LTC

Create Governor's Task Force

on Transforming New Jersey’s

LTC Delivery System

Core Recommendations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Note: Many of these recommendations are interrelated; the order of recommendations does not indicate relative priority.

22

Consolidate Response Effort Through a Central LTC Emergency

Operations Center: Context

• To manage reopening and potential future surges, New Jersey will need a tightly managed, unified

response and “true north” to coordinate resources and communications particularly in light of a

large fragmented LTC industry.

• New Jersey’s emergency management central command structure is widely seen as organized and

effective. It is unique in its organization under the State Police, but like many states, it more

frequently focuses on incident/hazard response and natural disasters, coordinating through a

network of county offices and a large number of highly decentralized public health offices.

• In support of the COVID-19 response, New Jersey reactivated a regional medical coordination

center (MCC) model, which has been effective in managing hospital capacity.

• However, in spite of an expanded emergency response focus on LTC facilities, there are many

moving parts and alternative mechanisms for nursing homes and other LTC facilities related to

reporting, seeking supplies (PPE and testing equipment) and addressing urgent issues. Facilities

have varying capacities to absorb and appropriately respond to the information and direction.

• With sufficient resources, DOH could mount a central infrastructure or capacity that coordinates

all activity and communications for nursing homes and LTC, which have proven to be the “eye of

the storm” in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Examples From Other States

• Delaware activated its State

Health Operations Center

(SHOC), which provides

command and control for all

public health emergencies.

SHOC operations include

“Points of Dispensing,”

alternate care sites, and a

joint centrally located

information center that

includes workers from

multiple state agencies.

• Colorado’s Unified Command

Center launched a Residential

Care Task Force which rapidly

implemented actions to

mitigate COVID-19 spread.

1

Context

23

Near-Term Recommendations

1. Establish New Jersey Long-Term Care Emergency Operations Center (LTC EOC) as the centralized command and resource for LTC COVID-

19 response efforts and communications.

• The LTC EOC would build on proven regional infrastructure and supplement (but not duplicate) and work in concert with the current

statewide COVID-19 emergency response efforts, as led by the Coronavirus Task Force, and supported by the New Jersey State Police’s

Office of Emergency Management (OEM).

• The LTC EOC would be led by DOH and staffed by DOH, Department of Human Services (DHS), or other agency staff (or through

contract support) as determined by DOH and DHS leadership. The LTC EOC team could also include clinicians, public health experts,

elder affairs and disability services representatives, emergency response/ New Jersey OEM representative(s), and other stakeholders

as DOH deems appropriate.

• The LTC EOC would have ongoing, direct communication mechanisms and feedback loops, including an advisory counsel, to obtain real-

time input from facility owners and staff, unions, resident/family advocacy representatives, and experts in the needs of special

populations, among other stakeholders, as appropriate.

• In addition, the LTC EOC would have a DOH staff person as the designated liaison to the industry.

• The LTC EOC would be charged with providing guidance to the State/OEM team to ensure that supplies are secured and distributed

rationally, critical staffing shortages are identified and solutions developed, problems are quickly surfaced and addressed, the

operational aspects of planned policies are vetted with industry and key stakeholders, and that policies and guidance are effectively

communicated to all stakeholders in order to ensure coordination and effectiveness.

Consolidate Response Effort Through a Central LTC Emergency

Operations Center: Recommendations

1

Indicates that a recommendation requires statutory or regulatory change.

24

Near-Term Recommendations

Consolidate Response Effort Through a Central LTC Emergency

Operations Center: Recommendations

1

• A dashboard could be developed (expanding on the current emergency data sources) to provide a real-time line of sight into on-

the-ground challenges and emerging issue areas and to proactively, for example, where and when a facility may need more than

30-days of PPE on hand.

• In addition to coordinating resource distribution, the LTC EOC would develop additional state guidance and federal guidance and

emerging best practices related to COVID-19-related infection control, symptom monitoring, use of telehealth and other. As with

the resource distribution guidance, the operational aspects of planned state guidance—including guidance suggested in other

recommendations—would be vetted with key stakeholders to ensure successful implementation.

2. Evaluate Regional Coordination Aligned with Hospital MCC Model

• New Jersey had a legacy regional medical coordination center (MCC) model* for disaster response (akin to the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA) Medical Operations Coordination Cells (

MOCCs)) to help facilitate regional capacity coordination and

communication across hospitals in the event of an emergency. DOH reactivated three regions to support the COVID-19 inpatient

response. A similar structure would be beneficial for LTC facility coordination, but is more challenging to stand up.

• One option is to expand on the existing regional MCCs and pair hospitals with nursing homes for infectious disease and infection

control consultation and emergency resource coordination, including potentially testing support as needed. This would require

additional funding and should be discussed as a potential model with FEMA among others.

*New Jersey consolidated its MCC operations from five into one center in 2018.

25

Design and Implement a “Reopening” Plan and Forward-Looking Testing

Strategy for Nursing Homes: Context

• Nursing homes support short stay (such as post-acute care rehabilitation) and long stay

(residential) needs and are critical providers of palliative care and end-of-life care for many. Most

of the short stays have stopped with the COVID-19 outbreak, but, as the health system resumes so-

called elective cases, patients will require high-quality, safe nursing home services and New

Jersey’s facilities will need to accept patient transfers.

• The nursing home ecosystem relies on many individuals from outside the facility, from medical

providers, to therapists, social workers, faith-based leaders, and health plan care managers, as well

as ancillary service providers. Family and other visitors and volunteers are also essential,

providing social visits and supplemental support services, including feeding, bathing, dressing,

personal care and other functions.

• In order to “reopen” nursing homes and resume normal operations, however, critical steps are

needed to fully prepare for a possible second wave and/or isolated outbreaks and protect

residents and staff to the fullest extent possible.

• New Jersey will need to provide clear guidance, direction and protocols, including on testing and

supplies, and facilities must act accordingly to ensure that nursing homes can safely reopen to

key providers such as hospice as well as visitors and new residents, that potential infections can be

identified and interventions swiftly implemented, and that there are sufficient contingencies in

place in the event of new crises. New Jersey has made progress in these areas, but additional work

is necessary.

2

Context

New Federal Guidance

• On May 18, the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS)

issued nursing home reopening

guidance for states focused on a

phased approach:

o Criteria for relaxing certain

restrictions and mitigating risk

of resurgence and factors to

inform decision-making

o Considerations allowing

visitation and services

o Recommendations for

restoration of survey activities

• On May 19, the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC)

updated and expanded its

guidance

for nursing homes, related to tiered

requirements by phase, testing

plans, and infection control.

26

Near-Term Recommendations

1. Develop a plan and provide guidance for how New Jersey nursing homes can comply with and implement

federal guidance on reopening. Through the LTC EOC, seek and incorporate feedback from stakeholders including

nursing homes, hospitals, and other providers on feasibility and clinical considerations.

• The guidance should provide, as a condition of reopening, that every facility have the following:

o Adequate isolation rooms/capabilities and the ability to cohort both staff and patients;

o An adequate minimum supply of PPE and test kits; and

o Sufficient staffing and a staffing contingency plan and appropriate staff training to carry out its responsibilities.

• The guidance should define acceptable models of cohorting (e.g., single rooms, separate wings/floors), the

staffing levels that must be in place, and how PPE and testing will be made available to facilities that are

unable to obtain them on their own.

• Implement a centralized FAQ resource, education sessions and focus groups to support nursing homes in

implementing this guidance.

• Require facilities to attest to meeting all requirements before opening their facility to new residents and

others, including family members, and if – at any time after opening – the circumstances change, they are

obligated to report any gaps that need to be addressed through the emergency center communications

mechanism.

• Do not permit hospitals to discharge patients to nursing homes unless such attestations are in place.

• The LTC EOC, with support or “strike” teams, will regularly check in on facilities’ capacity to reopen or stay

open, and where necessary, provide assistance to the facility during the public health emergency.

• Plan for the changes in policy and operations that may be needed if the flexibilities currently authorized

under federal 1135 waivers expire before future waves.

Design and Implement a “Reopening” Plan and Forward-Looking Testing

Strategy for Nursing Homes: Recommendations

New Federal Guidance

On May 18, the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services issued

nursing home reopening guidance

(

link) for States focused on a phased

approach:

o Criteria for relaxing certain

restrictions and mitigating the

risk of resurgence and factors

to inform decision-making.

o Considerations allowing

visitation and services in each

phase

o Recommendations for

restoration of survey activities

On May 19, the CDC updated and

expanded its guidance for nursing

homes, related to tiered

requirements by phase, testing

plans, and infection control (

link).

Examples From Other States

• Maryland has three types of statewide

strike teams support nursing homes:

testing teams (test and provide

instruction on cohorting), assistance

teams (assess equipment and supply

needs, triage residents), and clinical

teams (provide medical triage and

stabilize residents in the nursing home

to prevent transport to hospitals).

• Pennsylvania deployed a Medical

Assistance Team to provide staffing

support to facilities in need. The State

also developed detailed

guidance on

cohorting in response to test results.

• Minnesota designated nearly a dozen

LTC facilities as “COVID support sites.”

Facilities must be vetted by the state to

ensure they have adequate staffing,

supplies and infection-control

standards to accept COVID-19 patients,

including the ability to cohort

residents.

2

27

Near-Term Recommendations

2. Back-up Plan for Patient Placement in Event of Regional Outbreak or Surge

• The state should be prepared to support and quickly stand up at least three regional hub facilities for COVID-positive patients who do

not require hospitalization to manage capacity and centralize expertise in the event of future waves or case surges that overly tax the

system’s capacity to manage care.

• The LTC EOC and facilities should regularly monitor current capacity and intervention or patient redirection needs.

3. Forward-Looking Comprehensive Testing Plan

• New Jersey issued a mandatory testing Executive Directive on May 12 for nursing home residents and staff, which will provide a

baseline. The Executive Directive permits monetary penalties for non-compliant facilities; DOH should impose these penalties as

appropriate once there are sufficient testing kits available.

• Going forward, New Jersey will need a practical, feasible and flexible forward-looking testing policy:

Capacity to evolve over time:

• Should account for both advances in saliva testing, point-of-care

and serological testing and the ability to pivot to individualized

testing over frequent broad testing at the appropriate time.

• Future testing policies should consider the risk of spread by

group or setting, as well as the relationship to local infection

rates, which will change over time.

• Should include a combination of symptom screening and testing

for visitors with flexibilities for frequent visitors who were

previously tested and attest to certain infection control

protocols.

• In the event recurring testing is needed, the protocols should

prioritize the least invasive, most expedient methods available.

Centralized supports should include:

• Clear guidance for nursing homes that are able to

implement and manage a robust testing process in-house or

with their own system resources and associated funding

information.

• A mechanism by which nursing homes can partner with

select “hub” hospitals, based on the regional coordination

structure (as was successful in the Southern New Jersey

testing pilot) or preferred vendors.

• A network of preferred labs.

• Capability to quickly stand up state/hospital-supported

mobile testing units in the event of a surge.

Guidance on staff, supplies and funding:

• Facilities should provide on-site testing

opportunity to staff.

• Protocols should be developed related to staff

who work at multiple locations and

communication of testing results.

• Support for overall funding and supplies should be

developed through LTC EOC to ensure rational

allocation; nursing homes should be prioritized for

testing supplies.

• Long-term and ongoing reimbursement needs to

be further worked out at state and federal levels.

2

Design and Implement a “Reopening” Plan and Forward-Looking Testing

Strategy for Nursing Homes: Recommendations (cont.)

28

Near-Term Recommendations

4. Back-up Staffing Plan

• With ongoing testing, it is likely that staff – potentially on a rolling basis – will need to be quarantined or take sick leave due to exposure to

the virus (and/or for asymptomatic staff to be moved to COVID-19 wings/units).

• Each nursing home must develop a staffing back up plan, using the LTC EOC communication mechanism to alert the state to staffing

shortages. Options for ensuring adequate staffing will include a combination of (among others):

o “Bridge teams” (which could be formed in collaboration with hospitals, for example) to provide immediate temporary support;

o Staffing back up contracts negotiated by facilities, with encouragement to contract on a regional basis and potentially in partnership

with hospitals to achieve advantages of scale;

o National Guard deployments;

o Improved operations of the “Call to Serve” (volunteer) registry to improve vetting of volunteers qualifications and willingness to

volunteer in certain settings.

• Require nursing homes to report on staff quarantined or taking sick leaves to identify new or looming shortages.

Design and Implement a “Reopening” Plan and Forward-Looking Testing

Strategy for Nursing Homes: Recommendations (cont.)

Intermediate to Long Term Recommendations

• Given the financial challenges and costs faced by health care providers due to the pandemic, some nursing home operators in New Jersey may file for

bankruptcy or indicate an inability to continue operations.

• New Jersey should plan for such economic distress scenarios and evaluate options for receivership, management support and other mechanisms to

support distressed facility operators to ensure continuity of high-quality services to residents if needed.

2

29

Implement Strategy for Resident & Family Communications: Context

Examples From Other States

• New York strongly encourages nursing

homes to develop a communication

protocol for family, loved ones and

residents when visitation is suspended

that includes notification of suspected

cases of COVID-19 and regular updates.

• Massachusetts launched a family

resource line that is staffed seven days

a week from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Staffers

coordinate with state agencies to find

answers to callers’ questions, in

addition to directing them to the state’s

nursing home resource site.

• Florida is partnering with the

Alzheimer’s Association and other

stakeholders to distribute tablets

statewide and provide training to

nursing home and assisted living facility

residents to enable communication

with family.

Context

• Restricting visitation at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic was necessary to

protect nursing home residents; however:

o It cut residents off from regular communication with loved ones, and

o It prevented family members from playing a role in caring for residents and

monitoring the day-to-day operations of nursing homes.

• DOH has taken steps toward addressing these issues, such as issuing a

directive

to nursing homes in early April (in line with state statute and regulations) prior to

related federal guidance to notify all residents and staff members of suspected or

confirmed cases of COVID-19.

• Additional protocols and resources should be put in place to ensure frequent and

regular communications between families and residents and facility staff during

periods of restricted visitation.

• In addition, support is needed to ensure residents are able to leverage telehealth

opportunities and ensure continuity of care.

3

30

Near-Term Recommendations

• Develop guidance establishing expectations for nursing homes’ communications with residents and staff, families, and other representatives,

including Medicaid managed care plans and care managers, covering:

o Frequency of communications between (1) nursing homes and families, and (2) residents and their families.

o Content of communications, including updates on the resident, the facility, and COVID-19 cases.

• Disseminate guidance to residents, families, and representatives on the process for elevating concerns to nursing home staff, Medicaid

managed care plans, and relevant branch of the state (e.g., DOH or LTC Ombudsman).

• Strengthen MLTSS contractual requirements for care manager responsibilities at times when visitation is restricted.

• Further publicize process for nursing homes to request up to $3,000 to purchase communicative technology (e.g., iPads, Amazon Echo, etc.)

paid for using civil monetary penalty funding pools.

• Require nursing homes to dedicate a staff member to manage communications across residents, their families, and other representatives,

including supporting residents with using technology for personal calls and telemedicine.

Implement Strategy for Resident & Family Communications:

Recommendations

Intermediate to Long Term Recommendations

3

31

Recognize, Stabilize & Resource the Workforce: Context

Examples From Other States

• Illinois nursing home workers

secured a new contract that includes

an additional $2/hour for employees

working during the COVID-19 stay-at-

home order. The contract also

increased base pay rate to at least

$15/hour and expanded sick leave.

• Massachusetts funded a $1,000

signing bonus to workers who

registered through its LTC staffing

portal to work a minimum number of

hours at a nursing facility. Eligible

staffing types include: RN, LPN,

CNA/Patient Care Tech, OT, OTA, PT,

PTA, LICSW, and activities staff.

1

Neither New Jersey’s progressive paid sick leave policies (N.J. Stat. Ann. § 34:11D-8 (West)) nor the federal Families First Coronavirus

Response Act provisions relating to sick leave extend to all nursing home workers

Context

• Nursing home staff face a high risk of contracting and/or transmitting COVID-19

while caring for vulnerable residents.

• Nursing home staff earn close to minimum wage, have inconsistent access to

health coverage and sick leave

1

and are often not recognized or valued as part

of the health care workforce, factors that contribute to chronic staffing

shortages and turnover, and training gaps.

• Many nursing home staff work across multiple facilities to support their families.

• While some nursing homes in New Jersey have independently extended wage

enhancements to staff during the emergency, the state has not instituted wage

pass-throughs or other forms of supplemental pay to workers.

• Wage enhancements can help mitigate the need for staff to continue to work

across multiple facilities, decreasing the risk of exposure for themselves and

residents.

4

32

Near-Term Recommendations

Recognize, Stabilize, & Resource the Workforce: Recommendations

• Ensure all nursing home staff have access to paid sick leave.

• Institute wage enhancements for staff who work a minimum number of hours in a single nursing home, now and for future

COVID-19 waves (could be funded through Medicaid or Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding).

Intermediate to Longer-Term Recommendations

• Work with legislature to create a workforce development and appropriations package to:

o Design and implement minimum staffing ratios for RNs, LPNs, and CNAs that are aligned with differential needs of

nursing home residents (e.g., residents with dementia). Prohibit professional staff serving in administrative roles from

counting toward these ratios.

o Establish a wage floor and wage pass-throughs for future Medicaid rate increases. Wage increases should be linked to

expectations for additional training for workers to strengthen quality of care.

• Strengthen training and certification requirements and opportunities, including annual in-service education requirements to

build skills and expand scopes of practice.

• Seek federal and state funding to develop a direct care workforce career development program focused on recruitment,

training and career advancement.

4

33

Institute COVID-19 Relief Payments for Nursing Homes & Review

Rates Going Forward: Context

Relevant Federal Guidance

• In March, CMS released a Disaster

Relief State Plan Amendment

template, permitting states to

temporarily increase rates for

services covered through Medicaid

fee-for-service

• In mid-May, CMS released

guidance to states on ways to

effectuate temporary provider rate

increases through Medicaid

managed care.

Context

• To respond to COVID-19, nursing homes have additional costs related to cleaning, facility

reconfiguration, PPE, testing and staffing, while they are losing revenue from the lack of

rehabilitation stays after elective procedures. Nursing homes have a short-term need to fund these

new costs to promote safety.

• To date, approximately one-third of states have made COVID-19 relief payments to nursing homes to

offset increased costs and to ensure sufficient liquidity to maintain full operations; New Jersey has not

done so.

• Medicaid is the largest payer for LTC services. While DHS has instituted multiple rate increases since

fiscal year 2016, current Medicaid rates do not anticipate wage increases and state-of-the-art

equipment, among other expenses.

• Some nursing homes across the country, however, have generated large profits.

o For example, nationwide in

2016, for-profit SNFs had an average Medicare profit of 14%, with

one-quarter of facilities having a profit of over 20.2%. However, Medicaid is the largest payer

for nursing homes and individual facility potential profitability also depends in part on whether

and to what extent the home serves Medicaid-covered residents.

o These profits may represent funds that are diverted from the provision of care and facility

upgrades. DOH and DHS have limited insight into how nursing homes are using their publicly-

funded revenues.

5

34

Institute COVID-19 Relief Payments for Nursing Homes & Review

Rates Going Forward: Recommendations

Near-Term Recommendations

• Rely on federal coronavirus relief and stimulus funding, including

CARES Act funding, and/or Medicaid to provide temporary relief

payments to nursing homes. Any new disbursements should net out

previously received CARES Act funding. (See Appendix for description of

CARES Act funding.)

• New Jersey may want to consider whether temporary relief payments

should be tied to compliance with reporting and other requirements.

Examples From Other States

• Connecticut increased nursing home

provider rates by 10% to cover:

o Staff retention bonuses, overtime,

and shift incentive payments

o New costs related to screening

visitors, PPE, and cleaning and

housekeeping supplies

o Other COVID-related costs

• Massachusetts temporarily enacted a 10%

Medicaid rate increase for nursing homes

to support additional staffing, infection

control and supply costs. Facilities that

create dedicated COVID-19 wings and

units and follow necessary safety

protocols are eligible for an additional

15% rate increase.

5

35

Institute COVID-19 Relief Payments for Nursing Homes & Review

Rates Going Forward: Recommendations (cont.)

1. Review Rates and Link Any Increases to Quality and Safety

• Contract with a vendor to conduct a rate study to assess: (1) sufficiency of Medicaid nursing home rates to cover direct care and administrative costs (e.g.,

reporting); (2) the distribution of nursing home spend between direct care, administrative costs, and other expenses; (3) nursing home resident acuity levels; (4)

potential to apply acuity adjustments to rates; and (5) rate implications of staffing recommendations in this report. Vendor should have experience working with

at least 10 other states and/or health insurance carriers on health rating and have expertise on rates for nursing homes.

• If rate modifications are recommended, seek legislative authorization for increases. Require a portion of any rate increase be passed through to nursing home

workers, similar to state legislation passed for personal care services, and tie increases to quality and safety improvements. For example, require facilities to:

o Meet new staffing level requirements;

o Have staff participate in a state direct care workforce career development program; or

o Implement policies for improved coordination with MLTSS and care managers.

• Review DHS’s multi-year Medicaid value-based payment strategy, including the Quality Incentive Payment Program, to ensure incentives focus on key priorities

for quality improvement and consider whether incentives are enough of a “carrot” to impact behavior.

2. Create a Direct Care Ratio (DCR) Reporting and Rebate Requirement

• To ensure payments to nursing homes–including any increases–are used for resident care, seek legislative authorization to develop a nursing home DCR—similar

to the medical-loss ratio (MLR) requirements that apply to insurance plans—that requires facilities to use no more than a certain percentage of revenues for

administrative costs and profits. Insurance MLRs range from 80-89%. Set DCR based on historical cost reports and adjust as needed based on new financial

reporting requirements.

o Audit cost reports and recover payments in excess of the DCR requirements.

o Monitor performance of nursing homes to inform adjustments to DCR.

Intermediate to Longer-Term Recommendations

5

36

Institute New Procedures to Regulate and Monitor Nursing Home

Ownership: Context

Examples From Other States

• Massachusetts provides

an opportunity for public

input on any proposed

CHOW or notice of intent

to sell or close a SNF.

Applicants must

submit

three years of projected

profit and losses, and

projected three years’

capital budget.

• New York requires a CON

review process, including

a public hearing, for

CHOWs.

Context

• Nationally and in New Jersey, the ownership of facilities has become heavily for-profit and is frequently changing

hands. A facility may change ownership multiple times in a single week.

• For-profit facilities have opaque financials and can use complex ownership and management structures to obscure

the entities responsible for delivering care, curtailing the ability of the state and residents to hold them accountable.

• Rigorous change of ownership (CHOW) requirements are critical for ensuring accountability and promoting quality

and stability of the workforce. Current DOH processes fall short:

o DOH currently collects information from anyone with a 10% director or indirect ownership interest; however,

many states require the disclosure of anyone with a 5% (or less) interest.

o CHOWs are not public, and DOH has not historically disapproved a CHOW.

o Facilities that change ownership are not subject to any additional oversight or reporting following the change.

• The certificate of need (CON) process provides a more rigorous review of new facilities; however, a loophole in the

CON process allows new facilities to acquire previously approved but not utilized “paper beds” from other owners.

o Every five years, a facility may request approval of up to 10 beds or 10% of its licensed bed capacity, whichever

is less, without CON approval. Some facilities never actually add the beds, but holds approval or gives

approved beds to a “paper bed” broker. New owners can acquire “paper beds” (the beds acquired through the

add-a-bed process but never used) through the CHOW process, allowing them to skip the CON process

entirely.

6

37

Institute New Procedures to Regulate and Monitor Nursing Home

Ownership: Recommendations

• Increase transparency in CHOWs.

o Require disclosure of all direct and indirect owners having any or a 5% or more (states vary in their approaches) ownership interest and

all related parties that will be providing services to the facility.

o Require a proposed budget to be submitted with the CHOW application.

o Publicly post proposed CHOWs and solicit constituents’ feedback.

o Require closer scrutiny of quality and compliance with MLR requirements in the 2-3 years following a CHOW; including annual licensure

surveys.

o Impose a waiting period following a CHOW during which another CHOW cannot occur.

• Do not approve CHOWs when DOH has concerns regarding the prospective owner; instead, if necessary to protect residents, propose

temporary receivership or solicit a temporary manager. To the extent permitted by law, DOH could have a standing contract with a vendor that

can be triggered if the need arises.

• Close loopholes that allow significant changes without DOH oversight.

o Require prior approval before allowing a facility to delegate facility management to a third party.

o Revise the regulation to clarify that all beds added through the “add-a-bed” process solely be used by the facility and make these beds

nontransferable.

Intermediate to Longer-Term Recommendations

6

38

Improve Oversight of and Increase Penalties for Non-Compliant Facilities:

Context

Examples From Other

States

• Nebraska commenced

receivership against Skyline, and

Minnesota has been a receiver

and engaged a managing agent

for a facility at least three times

in the last ten years.

• Massachusetts creates and

publishes its own performance

report for each facility, which

includes changes of ownership.

It also performs state licensure

surveys biannually. Its Center for

Health Information and Analysis

collects significant data about

the quality, affordability,

utilization, access, and

outcomes of the health care

system in the state.

Context

• Survey and complaint processes are primary mechanisms for protecting residents who are unable to

advocate for themselves.

• DOH’s certification and survey and complaint investigatory arm has been historically under-resourced and

understaffed.

o DOH is unable to perform all of its CMS-mandated activities. It has 4,000 backlogged complaints, 700

of which are high priority due to the nature of the complaint. Some complaints are over two years old.

• DOH performs CMS-required facility surveys timely; however, there is broad agreement that the CMS survey

process is flawed. For instance, nursing homes are subject to the same survey intensity regardless of

historical compliance, and while the surveys are unannounced, facilities are often able to predict when they

will occur and ramp up staffing and alter existing procedures to produce better outcomes.

• CMS has authority over the sanctions and penalties imposed for CMS survey deficiencies. Penalties are

frequently reduced by CMS through the appeals process. Even when financial penalties are imposed, they do

not deter bad behavior. Nationally and in New Jersey, facilities have the same problems year-over-year.

• DOH has independent authority to impose penalties, revoke a license, appoint a receiver or temporary

manager or cease new admissions for violations of New Jersey requirements. Historically, DOH has not

exercised this authority.

• Complaints and other quality data are reported to several different entities, including the LTC Ombudsman,

DHS, Medicaid managed care plans and DOH, but are not aggregated. No one has a full picture of the quality

of care or recurring issues.

7

39

Improve Oversight of and Increase Penalties for Non-Compliant Facilities:

Recommendations

• Increase DOH funding and staff so that surveys can be performed and complaints can be investigated timely; perform licensure surveys of poor

performing facilities at least every two years that focus on fewer areas and validate through observation that the facility actually complies with its

policies. Require DOH to perform a survey of infection control and sanitation compliance of each facility every six months.

• Impose more serious sanctions—using New Jersey’s independent authority as needed—for top priorities.

o Impose more serious sanctions for infection control deficiencies.

o Exercise existing authority to impose more serious sanctions for non-compliance with state licensure requirements. Penalties should escalate

when the same deficiency is found on a subsequent survey or during a complaint investigation.

o Revise the regulations to increase the financial penalties for non-compliance.

• Terminate, revoke the license of, require temporary management of, or prohibit new admissions to poorly performing facilities (e.g., ones that have

repeat serious deficiencies, such as reusing single use equipment with multiple residents, or have a One Star Rating for consecutive years).

• Evaluate whether any willing provider requirement should continue – i.e., whether managed care plans should be empowered to end or suspend their

contracts with troubled facilities – and identify any other ways DHS can enhance Medicaid managed care plans’ role in monitoring quality as part of

network management and in coordination with DOH’s quality oversight.

• Leverage data obtained by CMS, DHS, DOH, Medicaid managed care plans, and the LTC Ombudsman to develop more robust reporting to identify

consistently poor performing facilities and those with a high number of substantiated complaints.

• Produce a nursing home report card for each facility that includes quality, complaint, and other information.

Intermediate to Longer-Term Recommendations

7

40

Rationalize and Centralize LTC Data Collection and Processing: Context

8

Examples From Other

States

• Massachusetts published its first

statewide nursing facility industry

report in 2019, highlighting

occupancy, operating expense,

utilization and staffing data, and

leveraged this data reporting

infrastructure to quickly collect

data from nursing homes on their

COVID-19 needs.

• Minnesota publicly provides

information on nursing home

staffing, rates, and quality.

• California collects and releases

comprehensive LTC facility

financial

data and utilization data

in machine-readable and easily-

analyzable formats as part of its

transparency efforts.

Context

• New Jersey’s LTC industry, DOH, DHS and DOH’s Division of Public Health Infrastructure,

Laboratories & Emergency Preparedness are not equipped with the technology, data, or analytic

staff to support ongoing data-driven oversight or to rapidly respond to public health

emergencies:

o LTC facilities struggle to understand and submit reliable data to satisfy a patchwork of

ever-changing federal, state and Medicaid managed care plan reporting requirements.

o State regulators are challenged to meaningfully collect, curate, analyze and use the

limited data received to support their core regulatory and program oversight functions

(e.g., capacity to measure and monitor population health/acuity).

• Industrywide underinvestment in modern technological and analytic infrastructure and

reporting has created an opaque, data-poor regulatory ecosystem that lacks nimbleness to

scale to regulatory need.

• Similar to other states, during the pandemic, New Jersey has relied on contractors and

associations to scale its information sharing capacity and deploy the most expedient system to

stand-up in some ways “makeshift” systems to quickly respond to the crisis, but will need to

migrate that data capacity and management in-house or cement a longer-term solution.

41

Rationalize and Centralize LTC Data Collection and Processing:

Recommendations

Near-Term Recommendations

1. Take actions to improve exchange of and access to critical information:

o Consolidate state and federal LTC COVID-19 reporting through the New Jersey Hospital Association (NJHA) PPE, Supply & Capacity portal; assess

current LTC facility COVID-19 reporting demands and standardize and consolidate them, where possible.

o Migrate NJHA portal onto DOH infrastructure; clearly communicate changes to LTC facilities.

o Establish centralized state LTC facility communication protocols to reduce duplicative outreach and increase information sharing; centralize

internal COVID-19 and LTC facility data reporting and storage to support cross-governmental information sharing (e.g., DOH, DHS, county OEM,

local health departments); establish automatic “alerts” to governmental points-of-contact, generated from LTC facility COVID-19 data

submissions that exceed established thresholds.

o Provide smaller LTC facilities with support (e.g., financial, staffing, technical assistance) to improve their health information technology (HIT)

capabilities, including data reporting.

o Compile complaints received across state agencies and review on a regular basis at the central emergency response system.

2. Implement new data reporting requirements:

o Focus should be on increasing market transparency and facilitating ability to enhance regulatory oversight.

o Require LTC facilities to publicly post (i.e., on websites) policies otherwise required to be compliant with state law, including outbreak response

plans, and have designated staff available to answer questions on policies.

8

42

Rationalize and Centralize LTC Data Collection and Processing:

Recommendations (cont.)

1. Develop centralized, rationalized, and scalable data and information-sharing infrastructure and protocols.

o Identify opportunities to eliminate duplicative reporting and/or standardize reporting requirements.

o Establish a centralized, cross-agency workgroup to monitor LTC-related data reporting.

o Assess state HIT needs to support technology-enabled and data-driven regulatory oversight across departments and

prospective uses (e.g., New Jersey Health Information Network, DHS risk adjustment); identify opportunities to centralize

and modernize state health data infrastructure, processes, and analytic capabilities.

o Assess LTC facility HIT needs to support population health management, interoperability, and modernized reporting

requirements.

o Identify and apply for federal funding to support infrastructure development.

2. Implement new data reporting requirements to increase market transparency and enhance regulatory oversight.

o Identify new data required from LTC facilities to support priority, cross-departmental regulatory needs; solicit nursing home

and managed care plan feedback on draft requirements, obtaining input on most efficient method of data collection and

specification; evaluate duplication of reporting across federal government, state agencies and managed care plans that might

be streamlined or automated; promulgate reporting requirements.

o Analyze data for oversight purposes, and make results public when possible.

o Produce public, annual report on the performance of New Jersey’s LTC system.

Intermediate to Longer-Term Recommendations

8

43

Improve Safety and Quality Infrastructure in Nursing Homes: Context

Context

• Promoting a safe and effective LTC system is a shared goal. Nursing homes must be safe, but they also must raise the bar

and improve quality.

• Infection control deficiencies are the most common type of deficiencies cited for nursing homes; Approximately

one-

third

of nursing homes surveyed by New Jersey were cited for an infection prevention and control deficiency in 2017.

Lessons learned from an infection

outbreak in a New Jersey facility in 2018 that resulted in the mortality of 11 children

could have been more widely implemented and leveraged as a catalyst for cultural change for other facilities and the

state.

• Quality improvement has multiple dimensions including structural (i.e., appropriate staffing, infection control expertise,

access to clinical consults as needed); process (i.e., protocols for infection control, training on use of PPE, etc.) and

outcomes (i.e. reduction in adverse events like falls with injury, bed sores, onset of pneumonia, increase in social

connectedness, functioning level, satisfaction with service and support by residents and families, among others).

• Level of clinical engagement and oversight (including role of the medical director), ensuring continuity of care during an

emergency (including review of care plans, advance directives, palliative care, coordination of medical care, and

transitions across care settings), and competency-based staffing and training are also important factors in building a

culture of quality.*

• Federal and state LTC oversight processes focus almost exclusively on citing and penalizing facilities. These are critical

functions but there are few opportunities for facilities to receive support and technical assistance to improve their

quality. Those that need help may be hesitant to disclose challenges for fear of penalties.

o New Jersey’s Infection Control Assessment & Response (ICAR) program provides consultations to facilities to

strengthen infection prevention, but funding for ICAR is dwindling, its capacity is limited, and its services do not

extend to broader quality improvement.

Examples from CMS and

Other States

• CMS has a targeted Probe

and Educate program that

helps providers reduce

claims denials and appeals

through one-on-one help.

• Florida deploys Rapid

Emergency Support Teams

to 200+ LTC facilities to

train staff on infection

controls and augment

clinical patient care.

• Missouri has a Quality

Improvement Program that

offers individual nurse

consultation and technical

assistance for the

completion of certain

assessments, quality

improvement, as well as

support groups and

workshops.

9

*DOH has provided financial support for nursing home workers to attend training programs , such as those through Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology and Rutgers Project ECHO,

but further training initiatives are needed.

44

Improve Safety and Quality Infrastructure in Nursing Homes:

Recommendations

Near-Term Recommendations

• Infection Control

o Mandate that every facility have a senior-level Infection Control Preventionist (ICP)* who reports to

the CEO and the Board of Directors. For facilities with over 100 beds, this position should be full-time

and the person should not have any other responsibilities.

o Request additional funding for the ICAR program (e.g., via civil monetary penalty funding pools).

o In addition, contract with a vendor or other entity able to rapidly assist in training and technical

assistance on infection control. For example, Rutgers University and NJHA have relevant experience to

rely on.

• Broader Quality Improvement

o Provide resources (e.g., civil monetary penalty funding pools) for a program either within DOH (but

outside of the enforcement arm) or a vendor to provide technical assistance to facilities on quality

improvement, best practices, or compliance with specific requirements, and that periodically reviews

whether the technical assistance is indeed improving quality of the nursing homes it supports.