2022

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City:

What Are the Issues? What Are the Strategies?

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City:

What Are the Issues? What Are the Strategies?

December 2022

Center for Health Workforce Studies

School of Public Health, University at Albany

State University of New York

1 University Place, Suite 220

Rensselaer, NY 12144-3445

Phone: (518) 402-0250

Web: www.chwsny.org

Email: [email protected]

Center for Health Workforce Studies

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................ 1

METHODS ................................................................................................................................................................. 1

Primary Data Sources ................................................................................................................................ 2

Secondary Data Sources............................................................................................................................ 3

Data Analysis............................................................................................................................................... 4

FINDINGS .................................................................................................................................................................. 4

Recruitment and Retention Challenges................................................................................................... 4

Strategies Used to Address Recruitment and Retention Diculties ................................................... 7

NYC Health Workforce Trends.................................................................................................................. 9

Registered Nursing Education in NYC: Preliminary Findings ..............................................................13

LIMITATIONS...........................................................................................................................................................13

DISCUSSION............................................................................................................................................................14

CONCLUSIONS .......................................................................................................................................................16

REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................................................17

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

The New Jewish Home Geriatrics Career Development Program ..................................................................... 6

NYC Health + Hospitals Nursing Residency Program.......................................................................................... 7

FutureReadyNYC...................................................................................................................................................... 8

Jamaica Hospital Student Nurse Summer Externship Program ........................................................................ 9

AHRC Retention Support Coordinator ...............................................................................................................10

TABLES AND FIGURES

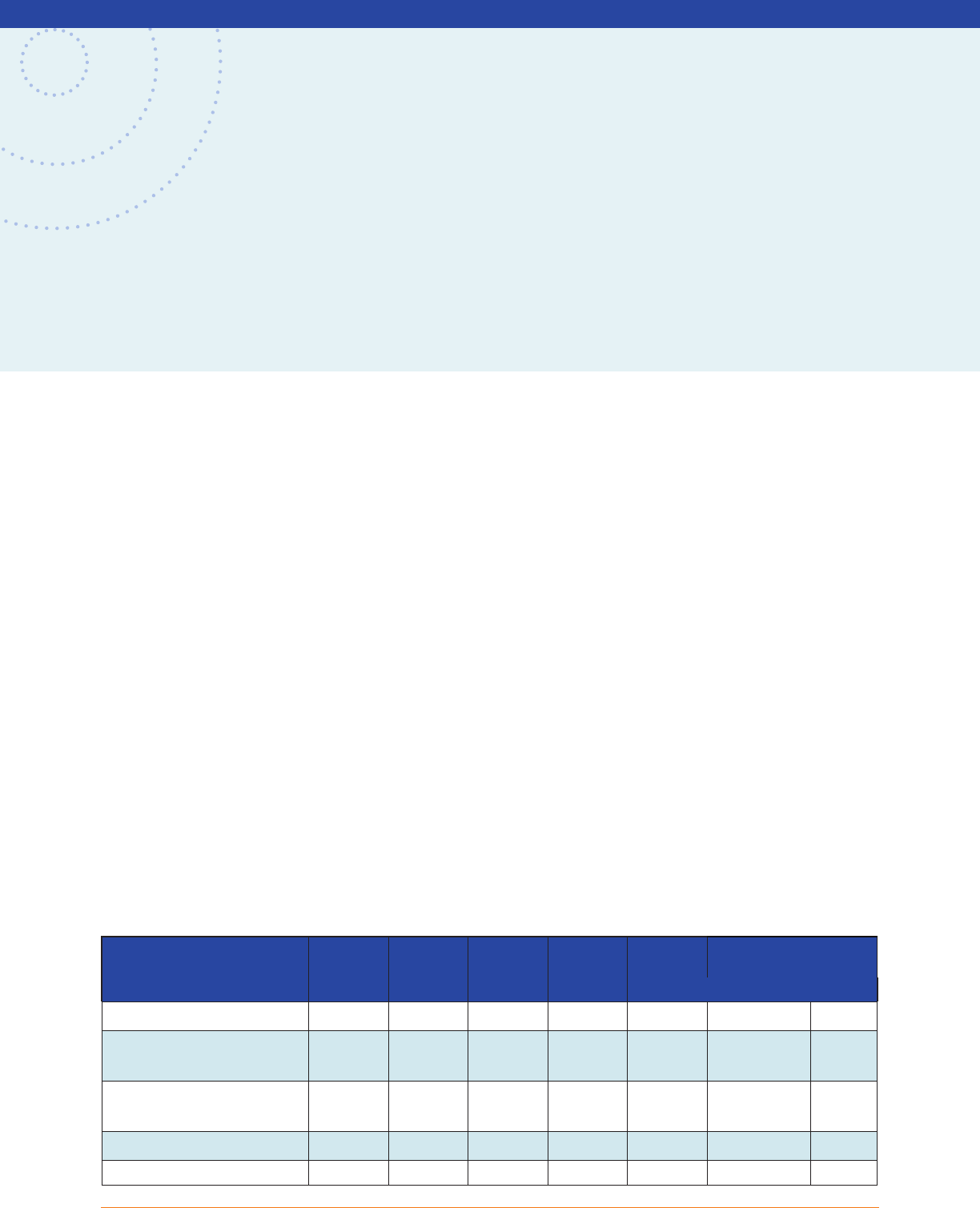

TABLE 1. Health Care Occupations with Recruitment and Retention Diculties in NYC by Setting ............. 5

FIGURE 1. Employment Growth in NYC, 2000-2021 (Standardized to 2000).................................................... 8

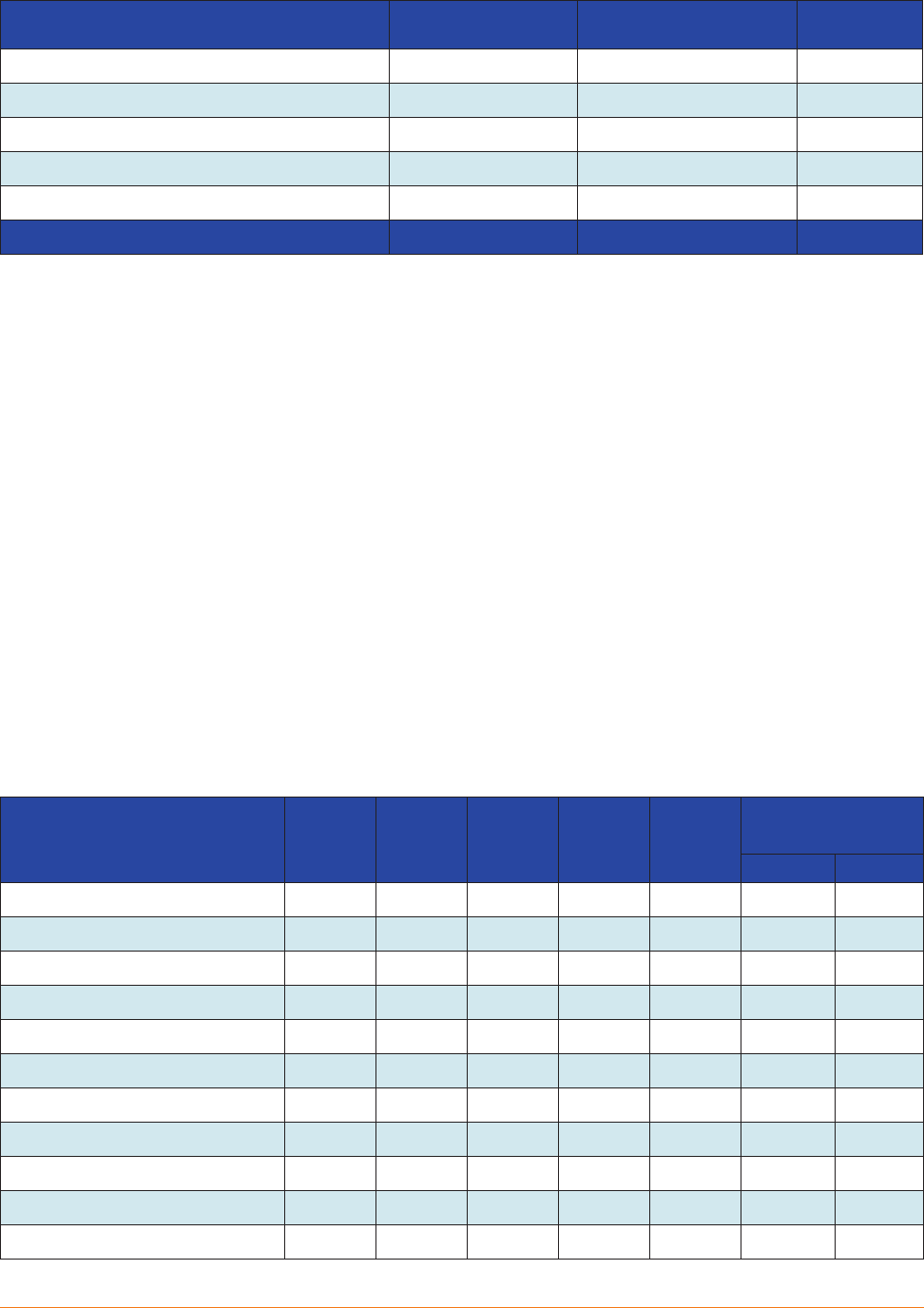

TABLE 2. Health Care Sector Employment in the New York City Region, by Setting, 2016-2020................... 9

TABLE 3. Employment Projections for NYC for Selected Occupations, 2018-2028 .......................................10

TABLE 4. Employment Projections for NYC by Setting, 2018-2028..................................................................11

TABLE 5. Count of RNs by License Address ........................................................................................................11

TABLE 6. The RN Workforce in NYC by Location of Residence and Work Setting..........................................12

TABLE 7. Number of Graduations in Selected Health Professions Education Programs in NYC,

2017-2021 ...............................................................................................................................................................12

ii

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

INTRODUCTION

The health workforce is a vital component of New York State’s health care delivery system. Eorts to

expand access to care, improve the quality of care, or address health disparities depend on the availability

of a diverse, well-trained, and adequately sized health workforce. Many states, including New York State

(NYS), face the ongoing challenge of health worker maldistribution. For instance, while the overall supply

of health workers appears to be adequate, these workers are not evenly distributed, resulting in areas that

are underserved. Chronic workforce shortages in primary care, oral health, and behavioral health have

persisted in many rural and inner-city communities of the state. Currently, nearly 30% of New Yorkers

reside in federally designated Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs), with many of these shortage

areas located in New York City (NYC).

1

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial impacts on the state’s health care delivery system as well as

on its health workforce. Initially, in response to surging COVID-19 cases, NYS used an array of strategies,

sometimes using executive orders to build workforce surge capacity, to make better use of the available

health workforce and to facilitate licensing health professionals from other states. In addition, health

professions education programs faced pandemic-related disruptions that jeopardized their students’ ability

to meet educational program requirements. More recently, health care providers report growing diculty

recruiting and retaining patient-care sta in all health care settings, including acute care, ambulatory care,

long-term care, and home health care.

The Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) is a research center based at the University at Albany

School of Public Health. Established in 1996, the mission of CHWS is to provide timely, accurate data and

conduct policy-relevant research on the health workforce to support health workforce planning and poli-

cymaking. CHWS monitors NYS’s health workforce and has studied long-standing workforce recruitment

and retention challenges reported by the state’s health care providers.

METHODS

CHWS, in collaboration with City University of New York (CUNY) and with support from 1199 SEIU League

Training and Upgrading Fund, conducted a study to identify the workforce issues that health care providers

face in the greater NYC area (the 5 boroughs of NYC, plus Long Island and the lower Hudson Valley), including

the factors contributing to recruitment and retention challenges, COVID-19 impacts, and the strategies

used to address these challenges.

Research questions included:

● What health professions/occupations are the most dicult for NYC healthcare providers to

recruit and why?

● What health professions/occupations are the most dicult for NYC health care providers to

retain and why?

1

Center for Health Workforce Studies

● Do recruitment and retention diculties vary by provider type?

● What strategies are health care providers using to recruit and retain needed workers?

● What are recent trends in the deployment of and demand for health workers in NYC?

● What impacts has the COVID-19 pandemic had on the health professions educational pipeline,

particularly registered nursing, in relation to admissions, graduations, capacity constraints,

transition to practice, and demand for new graduates?

The study used a mixed-methods approach to assess health workforce recruitment and retention issues

currently experienced by NYC health care providers, to understand the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic

has contributed to these issues, and to identify strategies used by providers to attract and retain workers.

Primary Data Sources

Key Informant Interviews

Semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted from May-August 2022 with approximately 15

human resources (HR) sta and Chief Learning Ocers from hospitals and hospital systems, including

safety net hospitals, academic medical centers, and community hospitals; long-term care facilities; home

health care agencies; and ambulatory care providers, including federally qualied health centers (FQHCs)

in the greater NYC area. Interview participants were selected through a convenience sample, with atten-

tion paid to location, organizational size, and sponsorship. Additionally, group interviews were held from

April-June 2022 with Chief Nursing Ocers from NYC health care organizations and in August 2022 with

HR sta from FQHCs.

Interviewees were asked about current recruitment and retention challenges; contributing factors, including

pandemic impacts; and potential strategies used to address these diculties. A team of 3-4 researchers

convened Zoom interviews, which lasted 30-45 minutes on average. Prior to the scheduled interview, a list

of questions was sent to participants that included:

● What professions/occupations are hardest to recruit?

● What professions/occupations are hardest to retain?

● What are the most common reasons for diculty in recruitment/retention?

● What strategies are used address stang challenges?

● How are gaps in transition to practice (preparation/readiness of new sta) being addressed?

● Are there any strategies in place to bolster training pipelines?

Health Care Employer Demand Surveys

Since 2000, CHWS has been surveying health care providers across NYS annually to learn more about their

recruitment and retention challenges and to determine whether there is variation by setting (hospitals,

long-term care, home care, and ambulatory care) and/or by geography. This data source supported a trend

2

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

analysis to determine whether recruitment and retention issues have changed over time, including a better

understanding of COVID-19 impacts on attracting and retaining health workers. The employer-demand

survey ndings for nursing homes, long-term facilities, and home health care agencies were based on

surveys conducted in 2022. The employer-demand survey ndings for hospitals and FQHCs were based

on surveys conducted in 2021. The most recent report of ndings from health care employer-demand

surveys can be found at: https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CHWS_RR_InfoGraphic_

Final_Updated-1-24-22.pdf and at https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/CHWS_FQHC_

RR_InfoGraphic_Final.pdf.

Survey of Nursing Deans of RN Education Programs in NYS

For over 20 years, CHWS has conducted an annual survey of the deans of NYS’s registered nurse (RN)

education programs. The survey asks about nursing program applications, admissions, and graduations as

well as the deans’ assessment of the local job market, barriers to expanding program capacity, and more

recently, COVID-19 impacts on their programs. The survey was conducted in the spring and summer of

2022, and it included separate surveys for associate degree RN programs and baccalaureate degree RN

programs. An analysis of data from this source was used to assess the RN educational pipeline in NYC,

including COVID-19 impacts. The most recent report based on ndings from this survey can be found at:

https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NURSING-ED-REPORT-NY-UT-2022.pdf

Secondary Data Sources

The Integrated Postsecondary Data System

The Integrated Postsecondary Data System (IPEDS) is a compilation of surveys conducted annually by

the US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. IPEDS includes information on

institutional characteristics, student nancial aid, faculty, and graduations by award level and by program

for educational programs from every college, university, and technical and/or vocational institution that

participates in the federal student-nancial-aid program. Data analyzed include nal data from academic

years 2016-2017 through 2019-2020 and provisional data from the 2020-2021 academic year. Data from

IPEDS were used in this study to assess trends in graduations from health professions education programs

in NYC.

The American Community Survey

The American Community Survey (ACS) is conducted each year by the US Census Bureau and is used to

provide population estimates by a variety of indicators, including age, gender, race and ethnicity, educa-

tional level, occupation, occupational setting, income, and socioeconomic status. The 5-year estimates can

be broken down by various geographic levels, including state, county, subcounty, census tract, and census

block. ACS data were used to develop estimates of RN employment in NYC. Data from the 2015-2019 5-year

estimates were used for the analysis.

3

Center for Health Workforce Studies

NYS Department of Labor employment data and 10-year projections

The NYS Department of Labor (NYSDOL) Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QWEC) data were

used to count the number of jobs in in health care by setting for the years 2017-2021 by NYSDOL region.

Additionally, NYSDOL developed regional projections for the 2018-2028 period by both occupation and

setting and the projections include counts of both newly created positions and annual job openings that

are a result of worker departures (retirements, job changes, departures from the eld). These data were

used to assess NYC health workforce employment trends over a 10-year period.

NYS Education Department RN licensure data

Licensure data from the NYS Education Department (NYSED) for the years 2018-2022 were used to count

the number of licensed RNs in NYC. NYSED uses licensees’ addresses to determine the county of residence.

The 5 boroughs of NYC were aggregated to obtain a regional total.

Data Analysis

All analyses were NYC-focused. IPEDS data were used to assess trends in graduations from health profes-

sions education programs. ACS data were used to estimate the number of RNs employed in health care

settings regardless of where they lived. NYSDOL employment data were used to report the number of health

care jobs in NYC. NYSDOL projections were used to identify the professions and occupations projected

to be in greatest demand over the 10-year period. NYSED licensure data were used to assess trends in

licensed RNs by geography.

The University at Albany Institutional Review Board (IRB) conducted a review of the interview protocols and

the proposed secondary data analysis and determined that the research was not human subjects research

and did not require an IRB application.

FINDINGS

Recruitment and Retention Challenges

Nurse leaders and HR sta from health care providers in all settings identied RNs as one of the occupations

most dicult to recruit and retain (Table 1). They also reported that licensed practical nurses (LPNs) were

also among the most dicult to recruit. HR sta from hospitals reported that clinical laboratory techni-

cians and technologists; MRI, ultrasound, and surgical technicians; respiratory therapists; and radiologic

technicians were also dicult to recruit and retain. HR sta from hospitals, home health care agencies, and

ambulatory care indicated that physicians, social workers, medical assistants, and clerical sta were dicult

to recruit and retain. HR sta from long-term care providers and home health care agencies reported that

home health aides were dicult to recruit and retain.

4

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

TABLE 1. Health Care Occupations with Recruitment and Retention Diculties in NYC by Setting

Setting Most Dicult to Recruit and Retain

Hospitals Behavioral health providers

Clinical laboratory technicians

Clinical laboratory technologists

Licensed practical nurses (recruitment only)

MRI, ultrasound, and radiologic technicians

Nurse practitioners

Registered nurses

Respiratory therapists

Social workers

Surgical technicians

Long-Term Care Providers Certied nurse aides

Clerical sta

Home health aides

Licensed practical nurses

Nursing directors and managers

Registered nurses

Home Health Care Home health aides

Licensed practical nurses

Nurse practitioners

Personal care aides

Registered nurses

Social workers

Ambulatory Care Providers Clerical sta

Licensed practical nurses

Medical assistants

Nurse practitioners

Obstetricians/gynecologists

Primary care physicians

Psychiatrists

Registered nurses

Social workers

Support sta

Reasons for Recruitment and Retention Diculties

Health workforce recruitment was problematic for providers prior to the pandemic. However, the COVID-19

pandemic exacerbated health workforce shortages in NYC, dramatically increasing the number of occupa-

tions in short supply as well as the magnitude of the shortages. Some of the occupations in short supply

have been problematic for many years, even prior to the pandemic. Some are newer, eg, the recruitment

diculties of LPNs reported by hospitals. Key informant interviewees in hospitals indicated they added

more LPN positions due to the diculties recruiting and retaining RNs.

5

Center for Health Workforce Studies

The New Jewish Home Geriatrics Career Development Program

The New Jewish Home Geriatrics Career Development (GCD)

is a workforce development training program for under-

served young people. GCD bridges the gap between geri-

GCD currently partners with 10 under-resourced New York

City public high schools to serve students in grades 10-12

through a 3-year after-school or out-of-school program. GCD

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

atric care job opportunities and underserved young people.

GCD provides hands-on experience, paid internships, job

training, and courses in healthcare certications aligned with

the needs of the industry.

Each year GCD serves approximately 275 participants ages

14-24 across 2 programs at no cost to the participants.

also trains young adults ages 18-24 who are disconnected

from education and employment through a 3-month full-

time skill development program that includes human devel-

opment, social support, foundational professional training,

healthcare career orientation, skills training for certication,

and connection to employment. There have been nearly

1,000 graduates since 2006.

Key informants generally agreed that a critical factor contributing to recruitment problems was that demand

for workers outstripped supply. As a result, there was great competition for available workers. Many

informants noted that many social-service agencies, retail stores, and fast-food restaurants are in direct

competition for the same entry-level workers. Key informants also indicated that noncompetitive salaries

contributed to the problem. An example cited frequently was that RNs were often drawn to travel or agency

nurse positions that paid much higher wages than NYC health care providers could oer them. This trend

extends beyond NYC.

2

NYC respondents to the employer-demand survey also agreed that a general shortage of workers and

noncompetitive salaries were key reasons for recruitment diculties. Long-term care respondents to the

survey also indicated that refusal to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine or booster also contributed to recruitment

and retention diculties. Home care respondents to the survey indicated that a lack of exible scheduling

and transportation challenges also contributed to recruitment diculties in home care agencies in NYC.

Most key informants noted a generational shift among prospective job candidates, indicating that younger

applicants were much more concerned with work-life balance and the need for organizational support for

worker resilience to address burnout. These younger workers seemed less mission-driven and more likely

to create boundaries that better separate work and personal life through behaviors such as “quiet quitting.”

3

These applicants were much more likely to want exible hours and, in some instances, the opportunity to

work remotely. Additionally, key informants across settings reported an increasing amount of “ghosting”

by prospective new hires who accepted jobs but never began employment. They also described new hires

who began employment but only stayed long enough to obtain the necessary experience to get a higher

paying job, often in a dierent setting.

Key informants as well as respondents to the employer-demand survey indicated that the retention of

health care workers by providers in NYC worsened during the pandemic. They attributed retention dicul-

ties to a variety of factors. Many workers experienced stressful working conditions (extremely ill patients

6

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

NYC Health + Hospitals Nursing Residency Program

NYC Health + Hospitals implemented a 12-month nurse

residency program in 2019 using evidence-based Vizient/

AACN curriculum for newly hired registered nurses (RNs)

The benets of the program include increasing retention

rates for the participating RNs who learn strategies for deliv-

ering patient care. The RNs participate in group seminars on

with less than 1 year experience or RNs who are new to their

decision-making, conict-resolution, end-of life care, health-

specialty. The sessions occur once a month over a 12-month

care quality, and patient safety, among other topics. RNs

period. The program starts at time of hire and is designed

participating in the program develop and present a poster

to build condence, build relationships, and develop leader-

on an evidenced-based practice topic that improves the

ship skills through shared learning and mentoring.

quality of patient care

and stang shortages) that resulted in attrition, often from patient-care positions. Many older workers

retired. Some workers who left their jobs were concerned about COVID-19 exposure and the potential

impact on themselves and their families. In addition, many workers found better paying jobs that were

often less stressful both in and out of health care. Some nurses pursued opportunities as travel nurses

or agency nurses, which tended to be higher paying. Other factors that contributed to attrition included

family commitments (childcare or eldercare) and transportation issues.

Strategies Used to Address Recruitment and Retention Diculties

Key informants described a variety of strategies they used to attract and retain workers. Some key infor-

mants described using incentives to attract health care professionals, particularly service-obligated schol-

arships and loan-repayment programs such as the Primary Care Service Corps, Doctors Across New York,

and the National Health Service Corps. In 2020, there were nearly 600 health care professionals who

participated in these programs and were fullling service obligations in NYC.

4

Informants also described partnerships with educational institutions to support career advancement

opportunities for new recruits as well as existing workers. Among the strategies used through these collab-

orations were standardized career-ladder programs (eg, nurse aide to LPN to RN) or internships or extern-

ships oered to health-professions students who would then go on to become employees after training.

Informants emphasized the value of local recruitment, indicating that community residents were more

likely to consider employment close to home.

Key informants discussed the urgent need to support new graduates’ transition to practice. During the

pandemic, RN students had limited access to clinical-training sites, greatly reducing direct-patient experi-

ence. According to Chief Nursing Ocers, many providers provide nurse residencies to new RN hires to help

them acclimate to patient care. However, preceptor shortages were problematic and challenged the eec-

tiveness of these residencies and oversight of clinical training for RNs and other health care professionals.

7

Center for Health Workforce Studies

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

FutureReadyNYC

Northwell Health, a hospital-based healthcare system,

partnered with the New York City Department of Educa-

tion to create “FutureReadyNYC.” It introduces students

The aim of FutureReadyNYC is to help students visualize

their career paths by introducing earn-and-learn and profes-

sional development pathways connected directly to their

in grades 9-12 to healthcare roles and gives them a better

studies. Additionally, FutureReadyNYC aims to remove

understanding of opportunities at Northwell Health based

barriers to employment and spark interest in healthcare that

on high-demand jobs. The program is operating at 4 high

drives participants to become future innovators, leaders,

schools throughout New York City.

and clinicians, while building relevant skills to support their

readiness for economically secure careers in healthcare.

Retention strategies reported by key informants included retention bonuses, worker-resilience programs,

exible hours, and use of hybrid models when possible. Some key informants added more support sta

(LPNs and nurse aides) to ease the demands placed on RNs, while others used agency sta to reduce

the need for overtime by existing nursing sta. One focus group participant described using a “retention

coordinator” whose job entailed working with both new and existing sta to assess their satisfaction with

working conditions and to the extent possible, make changes that supported worker retention. A few key

informants indicated that they were exploring the potential for recruiting foreign-trained RNs as a strategy

but indicated that the process was both costly and lengthy and had not yet proved fruitful.

FIGURE 1. Employment Growth in NYC, 2000-2021 (Standardized to 2000)

90%

100%

110%

120%

130%

140%

150%

160%

170%

Percentage of Job Growth

Year

Health Care Employment All Other Employmetn Sectors

Source: NYSDOL, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

8

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

Jamaica Hospital Student Nurse Summer Externship Program

Jamaica Hospital oers a 9-week paid externship program

each year that employs 30 nursing students during the

summer. RN students who are eligible for this program must

be currently enrolled in an accredited RN program and must

This program gives the student nurses an opportunity to

integrate theoretical knowledge with clinical skills and begin

to develop basic, critical thinking skills through the applica-

tion of the nursing process under the supervision of a nurse

have completed 2 semesters of clinical nursing rotations

preceptor. The program for 2022 began on June 26. Student

in an acute care setting and be entering their nal year of

externs were assigned to specic medical surgical units and

nursing education.

they also rotated through critical care and the emergency

department to gain more experience.

Some key informants described involvement in programs at local primary and secondary schools designed

to help students learn about health care career opportunities as well as expanded volunteer programs at

their facilities. They indicated that such programs may assure a future health workforce drawn from local

communities.

NYC Health Workforce Trends

Health Care Employment

● The Covid-19 pandemic aected both overall employment and health care employment in NYC.

Between 2019-2020, jobs in the health care sector in NYC declined by 4%, while jobs in all

other employment sectors dropped by 15%. Jobs in the health care sector in NYC, however,

rebounded in 2021, surpassing the number of jobs in 2019 (Figure 1). National trends indicate

a similar pattern of job loss in health care, with the number of jobs rebounding in 2021, though

not to the pre-COVID-19 levels.

5

● Jobs in home health care grew the fastest between 2016-2020 in NYC.

Between 2017-2021, jobs in home health care in NYC grew by 40%, jobs in ambulatory care grew

by 3%, and jobs in hospitals grew by 2% (Table 2). Jobs in nursing homes and residential-care

facilities in NYC both declined by 13% during the same period.

TABLE 2. Health Care Sector Employment in the New York City Region, by Setting, 2016-2020

Setting 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Change Between

2018-2022

Number Percent

Hospitals 205,662 205,108 208,304 211,577 209,483 3,821 1.9%

Ambulatory care (excluding

home health care)

129,172 129,152 134,312 122,008 132,903 3,731 2.9%

Nursing home and residential

care facilities

50,172 49,834 49,134 45,785 43,542 -6,630 -13.2%

Home health care 151,886 178,335 205,851 203,713 213,270 61,384 40.4%

Total 536,892 562,429 597,601 583,083 599,198 62,306 11.6%

Source: NYSDOL, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

9

Center for Health Workforce Studies

BEST PRACTICES FROM THE FIELD

AHRC Retention Support Coordinator

AHRC, a federally qualied health center, has implemented

the new role of retention support coordinator (RSC). The

RSC focuses on retaining and engaging with rst-year direct

support professionals (DSPs). The RSC sends out onboarding

The RSC creates training plans for struggling DSPs when

requested, which are discussed and approved by managers.

The RSC also meets with program directors and human

resources business partners to identify “focus areas” at

surveys at 30-, 60-, and 90-days after the start of employ-

specic locations that have increased turnover, increased

ment, and exit surveys to the rst-year DSPs who resign. The

complaints, or reports of low morale.

RSC also conducts “stay” interviews after DSPs successfully

complete their probationary periods.

Employment Projections

● Jobs for home health aides and personal care aides are projected to grow the fastest in NYC

between 2018-2028.

Home health aide positions are projected to grow by nearly 72% between 2018-2028 in NYC,

with more than 37,000 annual openings (Table 3). There are projected to be nearly 32,000

annual openings for personal care aides during the same time period.

TABLE 3. Employment Projections for NYC for Selected Occupations, 2018-2028

Title

Number of Jobs

Projected Change

Between 2018-2028

Average

Annual

Openings

2018 2028 Number Percent

Home Health Aides 165,810 285,030 119,220 71.90% 37,185

Personal Care Aides 126,720 210,360 83,640 66.00% 31,855

Registered Nurses 78,470 97,570 19,100 24.30% 6,610

Nursing Assistants 39,790 45,570 5,780 14.50% 5,361

Medical Assistants 13,670 19,220 5,550 40.60% 2,367

Licensed Practical Nurses 15,380 19,360 3,980 25.90% 1,722

Medical and Health Service Administrators 14,440 17,920 3,480 24.10% 1,630

Healthcare Social Workers 7,040 9,600 2,560 36.40% 1,069

Clinical Lab Technologists and Technicians 7,900 9,370 1,470 18.60% 691

Nursing Practitioners 6,480 8,990 2,510 38.70% 664

Physician Assistants 5,770 8,140 2,370 41.10% 632

Radiologic Technologists 5,200 6,440 1,240 23.80% 443

Surgical Technologists 2,530 2,910 380 15.00% 258

Respiratory Therapists 2,260 2,940 680 30.10% 205

Source: NYSDOL, Jobs in Demand/Projects, Long-Term Occupation Projections, 2018-2028.

10

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

● Driven by the growth of home health aide and personal care aide jobs, home health care

employment in NYC is projected to grow the fastest between 2018-2018.

Jobs in home health care are projected to grow the fastest in NYC between 2018-2028, increasing

by nearly 66%. Jobs in hospitals and nursing and residential-care facilities are projected to

increase by 13% and nearly 11%, respectively, during the same time period.

TABLE 4. Employment Projections for NYC by Setting, 2018-2028

Industry Title

Number of Jobs

Projected Change

Between 2018-2028

2018 2028 Number Percent

Ambulatory health care services 330,500 547,230 216,730 65.6%

Hospitals 213,450 241,210 27,760 13.0%

Nursing and residential care facilities 81,590 90,140 8,550 10.5%

Source: NYSDOL, Jobs in Demand/Projects, Long-Term Occupation Projections, 2018-2028.

Registered Nursing Employment in NYC

● Between 2018-2022, the number of licensed RNs with NYC addresses increased by nearly 8%.

Statewide, the number of total RN licenses increased by more than 17% between 2018-2022

(Table 5). The number of licensed RNs with NYC addresses increased by slightly over 9%, while

the number of RNs with other NYS addresses grew by nealry 9%. In contrast, licensed RNs with

out-of-state addresses increased by nearly 50% over the same time period.

● One in 10 RNs working in NYC lives in another state.

Based on an analysis of ACS data, 10% of RNs working in NYC live outside of NYS, including

11% of RNs working in hospitals (Table 6). In contrast, only 5% of RNs working in home health

care in NYC live outside of NYS.

TABLE 5. Count of RNs by License Address

2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Change Between

2018-2022

Number Percent

RNs with New York City addresses 68,802 71,070 72,103 73,956 75,128 6,326 9.2%

RNs with other NYS addresses 168,642 173,420 175,237 181,132 183,315 14,673 8.7%

RNs with addresses outside NYS 64,763 72,928 80,864 90,124 96,752 31,989 49.4%

Total NYS RN licenses 302,207 317,418 328,204 345,212 355,195 52,988 17.5%

Source: NYSED.

11

Center for Health Workforce Studies

TABLE 6. The RN Workforce in NYC by Location of Residence and Work Setting

Setting NYS Addresses # (%)

Out of State Addresses

# (%)

Totals

Home health care 3,298 (95.1%) 169 (4.9%) 3,467

Ambulatory care (other than home care) 6,229 (90.5%) 653 (9.5%) 6,882

Hospitals 51,431 (89.2%) 6,254 (10.8%) 57,685

Nursing homes/LTC 5,682 (91.4%) 532 (8.6%) 6,214

Other employment sectors 6,839 (92.8%) 534 (7.2%) 7,373

Total NYC RN workforce 73,479 (90.0%) 8,142 (10.0%) 81,621

Source: ACS, 5-Year Estimates, 2015-2019.

The NYC Health Professions Educational Pipeline

● Between 2017-2021, social worker graduations in NYC grew by 650, or almost 22%.

The number of graduations from social worker education programs in NYC grew by 650, or

almost 22% between 2017-2021 (Table 7). Additionally, the number of graduates from LPN

education programs in NYC increased by 139 or by nearly 67% during the same time period.

In contrast, the number of pharmacist graduates from NYC education programs declined by 277

or by 46%. While the number of pharmacist graduates has decreased, research has indicated

that the number of pharmacy graduates is still exceeding average annual job openings.

6

The

number of RN graduates from NYC education programs also decreased, declining by 80 or by

just over 2% between 2017-2021. Finally, the number of clinical laboratory technologist grad-

uations declined by 51 or by almost 38% during the same time period. The number of surgical

technology graduations also fell between 2017-2021.

TABLE 7. Number of Graduations in Selected Health Professions Education Programs in NYC, 2017-2021

Occupational Program 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Change Between

2017 and 2021

Number Percent

Clinical Laboratory Technicians 34 32 26 24 26 -8 -23.5%

Clinical Laboratory Technologists 136 113 88 102 85 -51 -37.5%

Licensed Practical Nurses 208 243 334 287 347 139 66.8%

Mental Health Counselors 346 357 359 411 353 7 2.0%

Pharmacists 602 546 298 328 325 -277 -46.0%

Physician Assistants 637 665 610 608 602 -35 -5.5%

Radiation Therapists 205 239 227 231 225 20 9.8%

Registered Nurses 3612 3,322 3,197 3,376 3,532 -80 -2.2%

Respiratory Therapists 23 28 0 0 43 20 87.0%

Social Workers 3,014 2,980 3,109 3,112 3,664 650 21.6%

Surgical Technologists 113 146 104 138 94 -19 -16.8%

Source: IPEDS.

12

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

Registered Nursing Education in NYC: Preliminary Findings

The 2022 Nursing Deans and Directors survey is currently in the eld. To date, over 30% of RN educa-

tion programs in NYC have responded to the survey (nearly a quarter of associate degree nursing (ADN)

programs and over 36% of baccalaureate degree nursing (BSN) programs. The following summarizes

preliminary ndings based on responses from NYC nursing education programs to date.

Nearly half of the deans reported that applications to their programs were comparable to last year. While

half of ADN deans indicated that applications to their programs were somewhat higher, only 18% of BSN

deans reported a higher number of applications compared to the previous year. More than 70% of the

deans indicated that the number of acceptances to their programs was comparable to last year.

Nearly three-quarters of the deans reported turning away qualied applicants for the 2021-2022 school

year. The reasons most often cited for turning away qualied applicants included faculty shortages, insuf-

cient number of clinical training sites, and program admissions caps. Over 33% of BSN deans cited lack

of classroom space as a reason for turning away qualied applicants.

More than 70% of deans indicated that they were recruiting faculty to ll vacant positions. On average, deans

reported recruiting for 3 faculty positions, and 80% of the positions were full time. More than two-thirds

of deans reported hiring adjunct faculty to ll these vacancies. When asked about the reasons for faculty

leaving their positions, the deans most commonly cited retirements, accepting nursing positions elsewhere,

making a career change in nursing, or family obligations.

When asked about COVID-19 impacts on their programs, two-thirds of deans cited reduced access to clin-

ical training sites which greatly reduced the preparedness of their graduates for entry into practice. All of

the deans reported increased use of simulation to help students complete clinical training requirements,

while some reported using alternate clinical settings to address this issue.

Nearly 80% of deans reported many job openings for their graduates. All BSN deans reported many jobs

in hospitals and in nursing homes, while all ADN deans reported many jobs for their graduates in nursing

homes. Nearly all deans agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic created more demand for newly trained RNs.

LIMITATIONS

Participants for the key informant interviews were selected using a convenience sample. Consequently,

they may not be representative of the population of health care providers in NYC, which could limit the

generalizability of ndings.

The hospital response rate to the employer-demand survey was low. This could result in selection bias,

eg, hospitals having the most dicult challenges responding to the survey which could limit the general-

izability of ndings.

13

Center for Health Workforce Studies

NYSDOL data were used to report the number of health care jobs in NYC. These data are potentially aected

by several factors, including closures, mergers, and expansions of health facilities. Consequently, large

changes in jobs in specic health sectors (ie, hospitals, nursing homes, or home health care) may reect

changes in ownership or the service delivery system rather than changes in the workforce. Additionally,

more recent changes in jobs and employment such as temporary or permanent layos or retirements due

to the COVID-19 pandemic may not be reected in the data.

NYSDOL 2018-2028 job projections include counts of both newly created positions and annual job openings

that are a result of worker departures (retirements, job changes, departures from the eld). Occupations

with a small increase in the number of new jobs but a high number of annual openings typically reect

signicant annual turnover rather than expansion of the occupation. Limitations to these projections include

unanticipated external factors such as recessions, changes in scope of work or education for specic occu-

pational titles, changes in state and/or federal reimbursement, and advances in technology. Additionally,

these projections did not account for the eects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the need for health care or

the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on the health care workforce.

NYSED licensure counts are based on the mailing address of licensees, which could be either a home or a

practice location. Certain individuals in the le may be licensed to practice in NYS but may live and/or work

in another state. Some individuals who are licensed in a health care profession may be working part time,

may not be working in the profession at all, or may be working in the profession in another state. Conse-

quently, licensure counts tend to overestimate the number of active health professionals working in NYS.

Not all health professions graduations reect newly licensed individuals entering a profession. For example,

some RN graduates are BSN completers, ie, they are already licensed nurses who obtained a higher nursing

degree. Additionally, graduation may not make a person qualied to practice in a profession. For example,

graduating with a bachelor’s degree in social work does not qualify a person for licensure in NYS.

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic had profound impacts on the state’s health care delivery system as well as its

workforce. Initially, as COVID-19 pandemic cases surged, demand for acute care services rose sharply.

NYS used a number of dierent strategies, sometimes through executive order s to build health workforce

surge capacity, to make better use of the available health workforce and to facilitate licensing health profes-

sionals from other states. Many hospital systems hired travel RNs to ll stang gaps. This may explain the

dramatic increase in the number of RNs licensed in NYS with out-of-state addresses. The use of travel RNs,

however, is not a long-term solution. Decreased hospital admissions, especially from elective surgeries, in

conjunction with increased workforce costs, have nancially stressed hospitals even further.

Additionally, during that time, many providers, particularly in ambulatory care, cut back or stopped services

entirely, temporarily or permanently closing oces and laying o sta. This, in part, may explain the 4%

drop in health care employment between 2019-2020. For many patients, in-oce ambulatory visits were

14

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

replaced by telehealth or teledentistry visits. While national data have shown a rebound in health care

employment, the number of health care jobs has not returned to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels. This,

in combination with the increased number of retirements, has stressed the health care workforce even

further.

As acute COVID-19 cases began to subside, health care providers in all settings experienced great diculty

recruiting and retaining workers, particularly in patient care. While health worker shortages were not a new

phenomenon, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically increased the number of occupations in short supply

as well as the magnitude of the shortages. Other employment sectors were also experiencing widespread

labor shortages at that time and were also competing for the same entry-level workers. As a result, there

was very strong competition for workers in general and in health care settings specically.

RNs, LPNs, and social workers were identied as very dicult to recruit by providers across all health care

settings. Hospitals also reported diculty recruiting behavioral health providers, radiologic technicians,

surgical technicians, respiratory therapists, and laboratory technicians and technologists. Long-term care

providers also reported diculty recruiting nursing directors, CNAs, and clerical sta. Home care providers

reported diculty recruiting and retaining home health aides and personal care aides. Ambulatory care

providers reported diculty recruiting physicians, nurse practitioners, behavioral health providers, clerical

sta, and medical assistants.

A critical factor that contributed to recruitment problems was that demand for workers outstripped supply,

resulting in greater competition for available workers. Noncompetitive salaries were also problematic.

Those occupations considered hard to recruit were also identied as hard to retain and the COVID-19

pandemic contributed to more attrition from the workforce. Many workers experienced stressful working

conditions (extremely ill patients and stang shortages) and left their jobs, including many older workers

who retired. Some workers left their jobs because they were concerned about COVID-19 exposure and

the potential impact on themselves and their families. Other workers found better paying jobs both in

and out of health care. Other factors that contributed to increased attrition included family commitments

(childcare or eldercare) and transportation issues.

Employers observed a generational shift in how younger employees view their jobs. These workers prioritize

work-life balance by engaging in behaviors such as “quiet quitting” in order to avoid burnout and maintain

better balance between their work and personal lives. Employers recognized the need to structure workers’

jobs to support resilience and help workers achieve this balance, giving them a sense of control, while

ensuring the work gets done. Eorts to address these concerns have the potential to reduce behaviors

such as “ghosting” by new employees, who may be attracted to a work culture that prioritizes resilience

and balance. One key informant described using a retention coordinator who was tasked with worker

outreach and the development of strategies to support sta retention.

15

Center for Health Workforce Studies

The COVID-19 pandemic also impacted the health professions education pipeline. While there was little

change in the number of new RN graduates between 2020-2021, there was a change in new RNs’ practice

readiness. During COVID-19, many health care providers were unable to accommodate clinical rotations for

students and as a result, nursing students had limited experience working directly with patients. According

to many of the individuals interviewed, this left them much less prepared for working in patient-care

settings. Nursing deans indicated that they cannot easily expand program capacity as they are constrained

by limited access to clinical training sites and faculty shortages.

A variety of health workforce recruitment strategies were identied and included service-obligated scholar-

ships and loan-repayment programs. Other providers reported educational partnerships to support career

advancement, including career ladders. Nurse residencies were a common strategy to support transition to

practice for new RN graduates. Retention strategies included sign-on bonuses, worker resilience programs,

and exible hours. Also, providers added more support sta or agency sta to reduce demand on patient-

care RNs. It is unclear how successful these strategies have been in the short term and what their impact is

long term. Thus, it is important to assess the eectiveness of these strategies and to identify best practices.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to identify the workforce issues that NYC health care providers were facing, the factors

contributing to recruitment and retention challenges, including COVID-19 impacts, and the strategies used

to address these challenges. Data drawn from a variety of sources, both primary and secondary, were used

to answer the research questions posed. Findings suggest widespread workforce shortages exacerbated by

the COVID-19 pandemic. Providers identied a variety of strategies that can potentially reduce the supply/

demand imbalances currently faced by NYC health care providers. Strategies that can potentially alleviate

health workforce shortages require collaborative eorts by a wide array of stakeholders including, among

others, providers, educators, labor, management, and governmental entities.

16

Health Worker Recruitment and Retention in New York City

REFERENCES

1

US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources & Services Administration. Health work-

force data, tools, and dashboards. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/

health-workforce-shortage-areas

2

Carbajal E, Plescia M, Gooch K. Why don’t hospitals just pay full-time nurses more? Becker’s Hospital

Review. January 21,2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/nursing/

the-complexity-behind-travel-nurses-exponential-rates.html

3

Wilks C. 5 Reasons Why Quiet Quitting Is Great for Your Mental Health. Psychol Today. Accessed August

29, 2022. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/human-ourishing-101/202208/5-reasons-why-quiet-

quitting-is-great-your-mental-health

4

Harun N, Martiniano R. The Impact of Service-Obligated Providers on Healthcare in New York State. Rensselaer,

NY: Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, SUNY Albany; September 2020.

5

Cantor J, Whaley C, Simon K, Nguyen T. US healthcare workforce changes during the rst and second years

of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(2):e215217. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.5217.

6

Lebovitz L, Rudolph M. Update on pharmacist workforce data and thoughts on how to manage the over-

supply. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):ajpe7889. doi:10.5688/ajpe7889.

17

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jean Moore, DrPH, FAAN

Director, Center for Health Workforce Studies

As director, Dr. Moore is responsible for administrative aspects and participates in the prepa-

ration and review of all CHWS research projects and reports, ensuring their policy relevance.

She also plays a key advisory role for CHWS, its activities, and the outcomes of its work. Dr.

Moore has served as principal investigator for more than 35 health workforce research studies

and authored nearly 70 publications, including peer-reviewed journal articles and reports.

Robert Martiniano, DrPH, MPA

Senior Program Manager, Center for Health Workforce Studies

Dr. Martiniano has an extensive background in health workforce research and program

management, including 11 years at the New York State Department of Health. He has worked

with a number of dierent communities, agencies and membership organizations on devel-

oping community health needs assessments, identifying provider and workforce shortages

based on the healthcare delivery system and the health of the population, and understanding

the impact of new models of care on the health care workforce—including the development

of emerging workforce titles.

Patricia Simino Boyce, PhD, MA, BS

University Dean for Health and Human Services, CUNY

Patricia Simino Boyce is the University Dean for Health and Human Services (HHS) at CUNY.

Dr. Boyce is responsible for the portfolio of HHS undergraduate and graduate degrees, and

credit-bearing certicate programs across CUNY’s 25 colleges and graduate schools, repre-

senting 40,000 enrolled students. Dr. Boyce provides strategic direction across CUNY’s HHS

portfolio and collaborates with academic leadership, industry partners, and key stakeholders

to mobilize resources, best practices, partnerships, and innovations to ensure distinction in

CUNY’s academic programs and clinical experiences that drive career success for students and

meet industry needs for the healthcare, allied health, public health, and human service elds.

School of Public Health | University at Albany, SUNY

1 University Place, Suite 220 | Rensselaer, NY 12144-3445

www.chwsny.org