Reprinted with permission from Reading Teacher, Vol. 66, Issue 4, December 2012, January 2013

Irene C. Fountas

•

Gay Su Pinnell

Guided

Reading

“ The compelling benefits of guided reading for students may elude us unless we attend

to the teaching decisions that assure that every student in our care climbs the ladder of success.

Let’s think about some of the areas of refinement that lie ahead in our journey of developing expertise.”

The Romance

and the Reality

COMPLIMENTARY COPY FOR IRA ATTENDEES

fountasandpinnell.com | heinemann.com | 800.225.5800

Over their influential careers, Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell have

closely examined the literacy learning of thousands of students. In

1996 they revolutionized classroom teaching with their systematic

approach to small-group reading instruction as described in their

groundbreaking text, Guided Reading. Since then, their extensive

research has resulted in a framework of professional development

books, products, and services built to support children’s learning.

Fountas and Pinnell’s work is now considered the standard in the field

of literacy instruction and staff development. Teachers worldwide

recognize their deep understanding of classroom realities and their

respect for the challenges facing teachers.

Consult these Fountas & Pinnell research-based, practical resources

to effectively implement guided reading in your school/classroom

Over 20 Years

of Literacy

Leadership

Guided Reading: Good First

Teaching for All Children (1996)

Guiding Readers

and Writers(2000)

Teaching for Comprehending

and Fluency (2006)

Genre Study: Teaching with Fiction

and Nonfiction Books, K–8+ (2012)

The Fountas & Pinnell Prompting Guides (2011)

Irene C. Fountas

•

Gay Su Pinnell

www.FountasandPinnellLeveledBooks.com

MATCHING TEXTS TO READERS

FOR

EFFECTIVE TEACHING

Leveled Books, K–8: Matching Texts

to Readers for Effective Teaching (2006)

www.fountasandpinnellleveledbooks.com (2012)

www. Fo unt asa nd Pin nel lL eve le d Bo oks .com

2010

–

2012 Edition

33,000

T

HE

F

OU NTAS

&

P

INNELL

IRENE C. FOUNTAS

GAY SU PINNELL

NOW WITH O VER

TITL ES

The Fountas & Pinnell Leveled Book

List, K–8+, 2010-2012 Ed.

Fountas & Pinnell

The preeminent voices in literacy education...

T

h

e

R

o

m

a

n

c

e

.

.

.

MK-087 07/2014

continue the conversation.

Visit www.fountasandpinnell.com

for downloadable copies of

these articles and papers.

If we take a

romantic view, we could say

that once we have the book room,

small-group lessons, and leveled books and

things are running smoothly, we have arrived in

the implementation of guided reading. However,

the heart of this article is what we have learned from

many years of engaging teachers and students in

guided reading—what its true potential is,

and what it takes to realize it.

The Reading Teacher

GUIDED READING:

The Romance and the Reality

Vol. 66 Issue 4, pp. 268-284

T

h

e

R

o

m

a

n

c

e

.

.

.

According to research,

several factors make a difference in

students’ literacy learning, and each factor

is related to the selection and use of texts in

classrooms. Texts may be analyzed quantitatively, but

researchers suggest that qualitative analyses that only a

human reader can offer are also critical to understanding

text complexity. When we consider all the factors,

we realize that text complexity is far more than

a “number”, a “level”, or a “score”.

The Critical Role of Text Complexity

in Teaching Children to Read,

Fountas and Pinnell, ©2012

T

h

e

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

.

.

.

With an increase in

technology use among preschoolers

and school-aged children, an increase in

prekindergarten enrollments, and an increase in

full-day kindergarten programs, literacy achievement

is trending upward, expectations have risen, and

teaching is shifting. As a result of these changes, we

have made minor adjustments to the recommended

goals on the F&P Text Level Gradient.

TM

The F&P Text Level Gradient

TM

Revision

to Recommended Grade-Level Goals.

Fountas & Pinnell,

© 2012

T

h

e

R

e

a

l

i

t

y

.

.

.

Guided Reading: The Romance and the Reality

THE FOLLOWING ARTICLE was published in The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013. In

this article Fountas and Pinnell examine the growth and impact of guided reading, small group teaching for

differentiated instruction in reading that was inspired by their early publications. Guided reading has shifted the

lens in the teaching of reading to a focus on a deeper understanding of how readers build effective processing

systems over time and an examination of the critical role of texts and expert teaching in the process. In this article

Fountas and Pinnell realize that there is always more to be accomplished to ensure that every child is successfully

literate. The exciting romance with guided reading is well underway, and the reality is that continuous

professional learning is needed to ensure that this instructional approach is powerful.

THE INSIDE TRACK

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 pp. 268–284 DOI:10.1002/TRTR.01123 © 2012 International Reading Association

R

T

GUIDED

READIN

G

The Romance and the Reality

Irene C. Fountas

■

Gay Su Pinnell

I

n thousands of classrooms around the world,

you will see teachers working with small groups

of children using leveled books in guided

reading lessons. The teachers are enthusiastic

about providing instruction to the students in ways

that allow them to observe their individual strengths

while working toward further learning goals. Books

are selected with specific students in mind so that

with strong teaching, readers can meet the demands

of more challenging texts over time.

Readers are actively engaged in the lesson as

they learn how to take words apart, flexibly and

efficiently, while attending to the meaning of a text.

They begin thinking about the text before reading,

attend to the meaning while reading, and are

invited to share their thinking after reading. They

deepen their understanding of a variety of texts

through thoughtful conversation. The teachers have

embraced guided reading, “an instructional context

for supporting each reader’s development of effective

strategies for processing novel texts at increasingly

challenging levels of difficulty” (Fountas & Pinnell,

1996, p. 25).

As we look back over the decades since we wrote

our first publication about guided reading, we

recognize that there has been a large shift in schools

to include guided reading as an essential element of

high-quality literacy education. With its roots in New

Zealand classrooms (Clay, 1991; Holdaway, 1979),

guided reading has shifted the lens in the teaching of

reading to a focus on a deeper understanding of how

readers build effective processing systems over time

and an examination of the critical role of texts and

expert teaching in the process (see Figure 1).

We realize that there is always more to be

accomplished to ensure that every child is

successfully literate, and that is our thesis in this

article—the exciting romance with guided reading

is well underway, and the reality is that continuous

professional learning is needed to ensure that this

instructional approach is powerful.

There is an important difference between

implementing parts of a guided reading lesson and

using guided reading to bring readers from where

they are to as far as the teaching can take them

in a given school year. If you are a teacher using

guided reading with your students, we hope that,

as you read this article, your effective practice will

be confirmed while you also find resonance with

some of the points of challenge that will expand

your professional expertise. If you are a system

leader, we hope you will find new ways to support

Irene C. Fountas is Professor in the Graduate School of Education at

Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; e-mail ifountas@

lesley.edu.

Gay Su Pinnell is Professor Emeritus in the School of Teaching and

Learning at The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA; e-mail pinnell.1@

osu.edu.

trtr_1123.indd 268 11/17/2012 10:54:42 AM

4

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

269

the educators on your team as they

continue to refine and expand the

power of their professional practice.

The Romance

As an instructional practice, guided

reading is flourishing. As teachers move

to a guided reading approach, the most

frequent question they ask is: What

are the rest of the students doing? The

first agenda for the teacher is to build a

community of readers and writers in the

classroom so the students are engaged

and independent in meaningful and

productive language and literacy

opportunities while the teacher meets

with small groups (Fountas & Pinnell,

1996, 2001). The teaching decisions

within guided reading lessons become

the next horizon. Next we discuss some

of the changes that have taken place

with the infusion of guided reading.

Providing Differentiated

Instruction

Classrooms are full of a wonderful

diversity of children; differentiated

instruction is needed to reach all of

them. Many teachers have embraced

small-group teaching as a way of

effectively teaching the broad range of

learners in their classrooms. Because

readers engage with texts within their

control (with supportive teaching),

teachers have the opportunity to see

students reading books with proficient

processing every day. In addition, it is

vital to support students in taking on

more challenging texts so that they

can grow as readers, using the text

gradient as a “ladder of progress” (Clay,

1991, p. 215). Inherent in the concept of

guided reading is the idea that students

learn best when they are provided

strong instructional support to extend

themselves by reading texts that are on

the edge of their learning—not too easy

but not too hard (Vygotsky, 1978).

Using Leveled Books

One of the most important changes

related to guided reading is in the type

of books used and the way they are used.

Teachers have learned to collect short

texts at the levels they need and to use

the levels as a guide for putting the right

book in the hands of students (Fountas &

Pinnell, 1996). The term level has become

a household word; teachers use the

Figure 1 Structure of a Guided Reading Lesson

“The teaching

decisionswithin

guided reading

becomethe next

horizon.”

trtr_1123.indd 269 11/17/2012 10:54:43 AM

5

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

270

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

gradient of texts to organize collections

of books for instruction. They collaborate

to create beautiful book rooms that bring

teachers across the grade levels to select

books from Fountas and Pinnell (1996,

2001, 2011) levels A through Z.

In many schools, neatly organized

boxes, shelves, or baskets make it

possible for teachers to “shop” in the

common book room. They can access

a wide variety of genres and topics and

make careful text selections. Book rooms

often have special sections for books

that are not leveled—enlarged texts (“big

books”) and tubs of books organized

by topic, author, or genre for interactive

read-aloud or book club discussions.

Publishers have responded to

teachers’ “love affair” with leveled

books by issuing thousands of new

fiction and nonfiction titles each year.

Most of these texts are short enough

to be read in one sitting so readers can

learn something new about the reading

process—strategic actions that they

can apply to the longer texts that they

read independently. The individual

titles enable teachers to choose

different books for different groups

so that they can design a student’s

literacy program and students can take

“different paths to common outcomes”

(Clay, 1998).

Conducting Benchmark

Assessment Conferences

Because they need to learn students’

instructional and independent reading

levels, teachers engage in authentic,

text-based assessment conferences

that involve students in reading real

books as a measure of how they read,

a process that 20 years ago was new

to many. Administered during the

first weeks of school, an assessment

conference with a set of carefully

leveled texts yields reliable data to guide

teaching (e.g., Fountas and Pinnell,

2012). The information gained from

systematic assessment of the way a

reader works through text provides

teachers with new understandings

of the reading process. Teachers are

learning that accurate word reading is

not the only goal; efficient, independent

self-monitoring behavior and the

ability to search for and use a variety of

sources of information in the text are

key to proficiency.

Using Running Records

toDetermine Reading Levels

A large number of teachers have

learned to use the standardized

procedure of running records (Clay,

1993) to make assessment more robust.

They can code the students’ reading

behaviors and score the records, noting

accuracy levels. From that information,

they make decisions about the level

that is appropriate for students to

read independently (independent

level) and the level at which it would

be productive to begin instruction

(instructional level). Sound assessment

changes teachers’ thinking about

the reading process and is integral to

teaching.

Using a Gradient of Text

toSelect Books

The A to Z text level gradient (Fountas

& Pinnell, 1996) has become a teacher’s

tool for selecting different texts for

different groups of children. Teachers

have learned to avoid the daily struggle

with very difficult material that will not

permit smooth, proficient processing—

no matter how expert the teaching.

Instead, they strive for text selection that

will help students read proficiently and

learn more as readers every day, always

with the goal of reading at grade level

or above. Teachers look to the gradient

as a series of goals represented as sets of

reading competencies to reach across the

school years.

Attending to Elements

ofProficient Reading: Decoding,

Comprehension, and Fluency

Assessment of students’ reading levels

and the teaching that grows out of it

go beyond accurate word reading. In

addition to the goal of effective word

solving, teachers are concerned about

comprehension of texts. Many students

“Sound assessment changes teachers’

thinkingabout the reading process and is

integralto teaching.”

“Efficient, independent

self-monitoring

behavior and the

ability to search for

and use a variety of

sources of information

in the text are key to

proficiency.”

trtr_1123.indd 270 11/17/2012 10:54:43 AM

6

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

R

T

271

learn to decode very well and can

read words with high accuracy. Their

thinking, though, remains superficial,

sometimes limited to retelling or

remembering details or facts.

Comprehension is assessed in

different ways, usually after reading.

Attention is increasingly focused on

comprehension as the central factor

in determining a student’s ability to

read at a level. Fluency, too, has gained

importance in teaching, especially

because it figures so strongly in effective

reading. Teachers are concerned

about students’ ability to process

texts smoothly and efficiently, and

specific instruction is dedicated to the

development of reading fluency.

Using the Elements of a Guided

Reading Lesson

Teachers have learned the parts

of the guided reading lesson—

internalized the elements, in fact,

so that they consistently provide an

introductionto a text, interact with

students brieflyas appropriate while

reading, guide the discussion, make

teaching pointsafter reading, and

engage students in targeted word work

to help themlearn more about how

words work. They have learned ways

of extending comprehension through

writing, drawing, or further discussion.

Evenstudents know the parts of the

lesson in a way that promotes efficient

work.

Building Classroom Libraries

for Choice Reading

Teachers have realized the importance

of a wide inventory of choice reading

in building students’ processing

systems. They have created beautifully

organized classroom libraries filled with

a range of fiction and nonfiction texts

that encourage students’ independent

reading. You can notice books with

their covers faced front, arranged

by author, topic, or genre, as well as

books organized by series or by special

award recognition. Students choose

books according to their interests and

spend large amounts of time engaged

with texts of their choice that do not

require teacher support for independent

reading.

The End of the Beginning

All these developments have been

accomplished with tremendous effort

and vision on the part of teachers,

administrators, and others in the

schools or district. It takes great

effort, leadership, teamwork, and

resources to turn a school or district

in the direction of rich, rigorous,

differentiated instruction. Creating

a schedule, learning about effective

management, collecting and organizing

leveled books, providing an authentic

assessment system and preparing

teachers to use it, and providing the

basic professional development to get

guided reading underway—all are

challenging tasks. Having an efficiently

running guided reading program is

an accomplishment, and educators

are justifiably proud of it. However,

as Winston Churchill said, “Now

this is not the end. It is not even the

beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps,

the end of the beginning.”

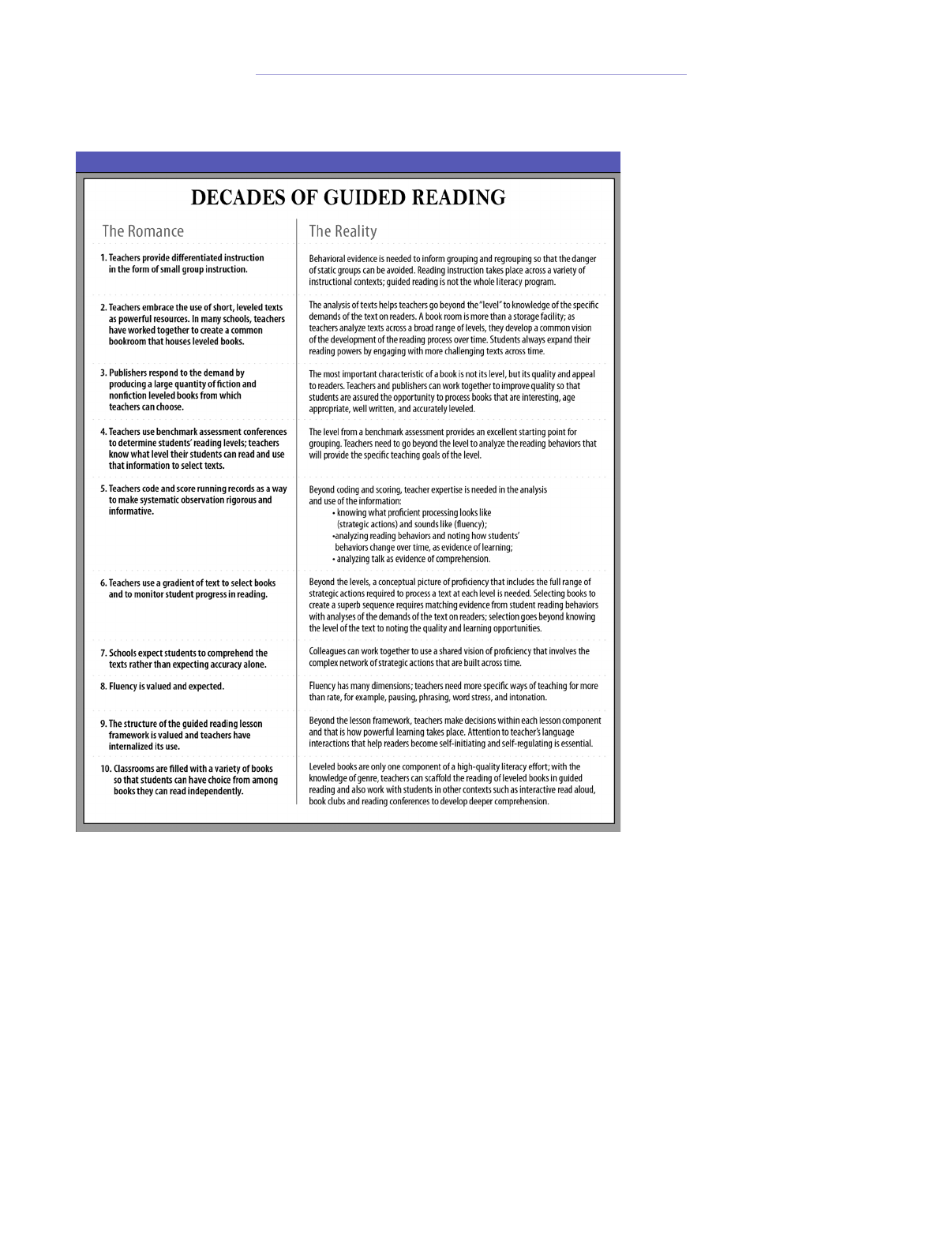

Many have experienced the romance

in the journey, and the reality is that

there will be more for everyone to

learn as we move forward. We have

summarized our general observations

of the accomplishments of decades

of guided reading and the challenges

ahead in Figure 2.

Of course, our descriptions will not

fit any one teacher or group of teachers,

but along with relevant challenges, we

hope they provoke thinking by raising

some issues related to growth and

change. The compelling benefits of

guided reading for students may elude

us unless we attend to the teaching

decisions that assure that every student

in our care climbs the ladder of success.

Let’s think about some of the areas of

refinement that lie ahead in our journey

of developing expertise.

The Reality

The deep change we strive for

begins with the why, not the how,

so our practices can grow from our

coherent theory. Our theory can also

grow from our practice as we use

the analysis of reading behaviors to

build our shared understandings and

vision. To changeour practices in an

enduring way, we need to change

our understandings. If we bring our

old thinking to a new practice, the

rationales may not fit (Wollman,

2007). Teaching practice may often be

enactedin a way that is inconsistent

with or even contrary to the underlying

theory that led to its development

(Brown & Campione, 1996; Sperling

&Freedman, 2001).

The practice of guided reading

may appear simple, yet it is not simply

“It takes great effort, leadership, teamwork,

and resources to turn a school or district in

the direction of rich, rigorous, differentiated

instruction.”

trtr_1123.indd 271 11/17/2012 10:54:43 AM

7

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

272

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

another word for the small-group

instruction of the past. We address

three big areas that offer new learning

in the refinement of teaching in guided

reading lessons, bringing together the

romance in guided reading with the

reality of its depth. These areas can be

summarized as readers and the reading

process, texts, and teaching. As we

discuss each area, notice the aspects that

reflect your growing edge as a reading

teacher.

A Shared Understanding

oftheProcess of Reading

Some teachers have learned to be

satisfied with their students simply

reading accurately. This practice has

led to pushing students up levels

without evidence of their control of

the competencies that enable them

to think within, beyond, and about

texts at each level. The goal of the

guided reading lesson for students is

not just to read “this book” or even

to understand a single text. The goal

of guided reading is to help students

build their reading power—to build

a network of strategic actions for

processing texts. We have described

12 systems of strategic activities,

all operating simultaneously in the

reader’s head (see Figure 3).

Thinking Within the Text. The first

six systems we categorize as “thinking

within the text.” These activities are

solving words, monitoring and correcting,

searching for and using information,

summarizing information in a way that

the reader can remember it, adjusting

reading for different purposes and genres,

and sustaining fluency. All these actions

work together as the reader moves

through the text. It is essential to

solve words; after all, reading must

be accurate. It is just as important to

engage the other systems. Readers

constantly search for information in

the print, in the pictures; they know

when they are making errors, and if

necessary, they correct them. They

reconstruct the important information

and use it to interpret the next part

of the text. Kaye’s (2006) study of the

word solving of proficient second-grade

readers showed the following:

When students are efficiently

processing text, they flexibly draw

from a vast response repertoire. They

use their expertise in language and

their knowledge of print, stories,

and the world to problem solve as

they read. Supported by mostly

correct responding, readers are

able to momentarily direct their

attention to thedetail of letters

and sounds as needed. When they

needto problem solve words in

greater detail, second graders can

draw upontheir orthographic and

phonological knowledge with incredible

flexibilityand efficiency, usually using

the larger subword units. Then they are

free to get back to the message of the

text. (p. 71)

Figure 2 Decades of Guided Reading

trtr_1123.indd 272 11/17/2012 10:54:43 AM

8

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

273

Thinking Beyond the Text. The next

four systems call for “thinking beyond

the text.” They are inferring, synthesizing,

making connections, and predicting.

Reading is a transaction between the text

and the reader (Rosenblatt, 1994); that is,

the reader constructs unique meanings

through integrating background

knowledge, emotions, attitudes, and

expectations with the meaning the

writer expresses.

When several of us read the same

text, we do try to understand the

writer’s message and share much

with each other. At the same time,

each reader’s interpretation is unique.

Readers infer what the writer means but

does not say; they make connections

with their personal experiences

and other texts. They bring content

knowledge to the text and synthesize

new ideas. They make predictions

before, during, and after reading.

Thinking About the Text. The last two

systems represent how the proficient

reader analyzes and critiques the text.

Readers hold up the text as an object

that they can look back at and analyze.

They notice aspects of the writer’s

craft—appreciate language, literary

devices such as use of symbolism, how

characters and their development are

revealed, beginnings and endings.

They critique texts: Are they accurate?

Objective? Interesting? Well written?

A Complex Theory. Reading is

far more than looking at individual

wordsand saying them. Readers

are in the fortunate position of

encounteringlanguage that is created

mostly by unknown individuals

whomay be distant in space and

time. The systems of strategic actions

take place simultaneously in the

brain duringthe complex process of

reading. The proficient reader develops

a networklike a computer, only

thousandsof times faster and more

complex. The brain learns, making new

connections constantly and expanding

the system. Clay (1991) described the

process:

This reading work clocks up more

experience for the network with each of

the features of print attended to. It allows

the partially familiar to become familiar

and the new to become familiar in an ever-

changing sequence. Meaning is checked

against letter sequence or vice versa,

phonological recoding is checked against

speech vocabulary, new meanings are

checked against the grammatical and

semantic contexts of the sentence and

Figure 3 A Network of Processing Systems for Reading

“The reader constructs unique meanings through

integrating background knowledge, emotions,

attitudes, and expectations with the meaning the

writer expresses.”

trtr_1123.indd 273 11/17/2012 10:54:45 AM

9

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

274

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

the story, and so on. Because one route

to a response confirms an approach

from another direction this may allow

the network to become a more effective

network. However the generative

process only operates when the reading

is ‘good,’ that is, successful enough to

free attention to pick up new information

at the point of problem-solving. An

interlocking network of appropriate

strategies which include monitoring and

evaluation of consonance or dissonance

among messages that ought to agree is

central to this model of a system which

extends itself. (pp. 328–329)

The amazing thing is that all of

this complex cognitive activity is

accomplished simultaneously and at

lightning speed; proficient readers are

largely unconscious of it (Clay, 1991).

We are writing here about the efficient,

effective, fluent processing that allows

readers to keep the greater part of

attention on the meaning of the text.

Teachers cannot see into the brains

of effective readers, and the process

breaks down the moment you make

readers try to describe their processing

(much like watching your fingers while

playing the piano).

However, skillful teachers have a

sharp observing eye, with the ability to

notice and understand the evidence of

processing shown in the behaviors of

students—how they read and what they

reveal through conversation about what

they read. Understanding the reading

behaviors that are evident in a student

who is processing well helps the teacher

detect inefficient or ineffective reading

and take steps to offer support. You can

also notice the way proficient readers

change over time; sometimes progress is

detectable every day!

When students engage in smooth,

efficient processing of text with deep

understanding, they can steadily

increase their abilities. That means

much more than just moving up levels;

the goal is to build effective processing

systems. It isn’t easy, but guided reading

offers that opportunity.

Fluent Processing: An Essential

Element of Effective Reading. Deep

comprehension is not synonymous

with speed, nor, surprisingly, is reading

fluency. Some in the educational

community seem to have become

obsessed with speed. However,

measuring fluency only as words

per minute is a simplistic view and a

procedure that may do harm. In our

work, we emphasize pausing, phrasing,

word stress, and intonation far more

than rate.

Rasinski and Hamman (2010)

reviewed the research and found that

the norms for reading speed have

gone up, but these increases have

not been matched by improvement

in comprehension. They believe that

the way reading fluency has been

measured has influenced practice and

in some places had a devastating effect

on reading itself. We now see students

who read rapidly and robotically, often

skipping without problem solving every

word not instantly recognized. The

result is a loss of comprehension and

confusion for the student about what it

means to read.

We recognize that proficient readers

do move along at a satisfying rate,

but fluency can’t be measured by rate

alone—certainly not by measuring

the rate of reading word lists. Reading

fluency means the efficient and effective

processing of meaningful, connected,

communicative language. According

to Newkirk (2011), “the fluent reader is

demonstrating comprehension, taking

cues from the text, and taking pleasure

in finding the right tempo for the text”

(p. 1). He hastens to explain that he does

not mean the laborious, word-to-word

struggle to read something that is clearly

too hard for the reader. And he says

there is no ideal speed. The speed has to

do with the relationship we have with

what we read. He describes his own

entry to a book:

I enter a book carefully, trying to get a

feel for this writer/narrator/teller that I

will spend time with. I hear the language,

feel the movement of sentences, pay

attention to punctuation, sense pauses,

feel the writer’s energy (or lack of it),

construct the voice and temperament of

the writer. (p. 1)

Oral Language: An Essential Element

of Effective Reading. Reading is

language and language is thinking. One

of the purposes of guided reading is to

bring the control of oral language to the

processing of a text. Of course, oral and

written language have important and

subtle differences, but oral language is

the most powerful system the young

child brings to initial experiences with

the reading process. As readers grow

more proficient, language still plays

a strong role. The most obvious is the

role of the oral vocabulary, which is

extremely important. However, teachers

also consider the reader’s grasp of

sentence complexity and the speaker’s

understanding of metaphor, simile,

“When students engage in smooth, efficient

processing of text with deep understanding, they

can steadily increase their abilities.”

trtr_1123.indd 274 11/17/2012 10:54:46 AM

10

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

275

expression, idioms, and other nuances

of speech.

Students’ language development is

important, and there is no better way to

expand it than to engage them in lively

conversation (not just questions and

answers) about any exciting subject as

well as about books. When students talk

about their reading, they tend to use the

language of texts, which is usually more

complex than their own. Guided reading

includes such discussion every day,

and teachers are working toward richer

conversations that will extend students’

language far beyond a dry recounting of

the story.

Using Systematic Assessment

The assessment system needs to

provide the behavioral evidence

that isconsistent with a shared

understanding of the reading

process.Itshould link directly to our

teaching. Good assessment is the

foundation for effective teaching.

Assessment in its simplest form

means gaining information about the

learners you will teach. The “noticing”

teacher tunes in to the individual

reader and observes how the reader

works througha text and thinks about

how the reading sounds. For some

teachers, assessment stops at finding

levels because they have not had

the opportunity to develop further

understandings of the value of specific

behaviors to inform teaching. The

assessment may be used to report levels,

and then the data are filed without the

benefit of their richness.

Using Assessment to Group and

Regroup Readers. In a comprehensive

approach to literacy education, small-

group teaching is needed for the

carefulobservation and specific

teachingof individuals that it allows,

as well as for efficiency in teaching

and the social learning that benefits

each student. For some teachers,

guided reading groups may have

become the fixed-ability groups of

the past. Teachersneed to become

expert in forming and reforming

groups to allowfor the differences in

learning thatare evident in students.

Some students may not develop the

same reading behaviors in the same

order andat the same pace as others.

The key to effective teaching is your

ability to make different decisions for

different students at different points

in time, honoring the complexity of

development.

A key concept related to guided

reading is that grouping is dynamic—

temporary, not static. Teachers

group and regroup students as they

gain behavioral evidence of their

progress. In our experience, the reason

groups don’t change enough is that

no systematic ongoing assessment

system is in place for teachers to use

to check their informal observations

with what students demonstrate when

asked to read a text without teacher

support. When teachers use ongoing

running records in a systematic way

(more frequently with lower achieving

students and less frequently with higher

achieving students), the data are used to

make ongoing adjustments to groups.

Often the only assessment in place is

beginning, middle, and end of year

assessment, and nothing systematic

happens in between.

Often teachers have a history of

using prescriptive programs in which

students are expected to pass through

the same books or materials so groups

may remain the same for a long period

of time. In guided reading, text selection

does not follow a fixed sequence that

students must progress through; there

are no workbooks or worksheets that

must be completed before moving

forward. Teachers are expected to select

different books for the groups and to

move students more quickly or slowly

forward as informed by their expert

analysis.

Using Assessment to Guide Teaching

All Year. A system for interval

assessment such as a benchmark

assessment conference using running

records even two or three times a

year isnot enough. The benchmark

information is old news in a few

weeks. To make effective decisions

for readers, you also need an efficient

system for ongoing assessment using

running records. A running record

usingyesterday’s instructional

book takes the place of benchmark

assessmentwith “unseen text.” The

running record becomes a useful tool

for assessing the effects of yesterday’s

teaching on the reader.

“Good assessment

is the foundation for

effective teaching.”

“Teachers need to become expert in forming and

reforming groups to allow for the differences in

learning that are evident in students.”

trtr_1123.indd 275 11/17/2012 10:54:46 AM

11

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

276

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

Your professional development may

have stopped with coding and scoring

reading behaviors; you may not have

had the opportunity to become expert

at their analysis and use in informing

your teaching. When you go beyond

coding and scoring, you make a big

shift in the way you think about your

teaching decisions in the lesson. Rather

than teaching the level or the book, you

notice and are able to use the behavioral

evidence to guide your next teaching

moves. We see this kind of teaching as

the “precision teaching” that makes

guided reading lessons powerful.

Reading teachers are like scientists

gathering precise data and using it to

form hypotheses. For example, you

can use running records or benchmark

assessments to:

■

Assess the accuracy level

■

Assess fluency

■

Observe and code oral reading

behaviors systematically to note

what students do at difficulty or at

error and learn how students are

solving problems with text

■

Engage the student in conversation

to assess comprehension at several

levels

From Assessment to Teaching: Using

a Continuum of Literacy Learning.

When you understand the complexity

of the reading process, you are able

to teach toward the competencies of

proficient readers. A precise description

of the behaviors of proficient readers

from levels A to Z constitutes the

curriculum for teaching reading. A

level is not a score; it stands for a set of

behaviors and understandings that you

can observe for evidence of, teach for,

and reinforce at every level.

Think about all the behaviors that

are observable in readers who process

a text well. Of course the behaviors

of effective processing at level A will

look very different from those at level

C or M or S. To support your ability to

teach for changes in reading behaviors

over time, we developed The

Continuum of Literacy Learning Grades

PreK-8: A Guide to Teaching (Pinnell

& Fountas, 2011). The Continuum

provides a detailed description of the

behaviors of proficient readers that are

evident in oral reading, in talk, and in

writing about reading so that you can

teach for change in reading behaviors

over time.

Understanding Leveled Texts

and Their Demands on Readers

The Fountas & Pinnell A–Z text gradient

and high-quality leveled books are

powerful tools in the teaching of reading

(see Figure 4). The appropriate text

allows the reader to expand her reading

powers. To become proficient readers,

students must experience successful

processing daily. Not only should they

be able to read books independently,

building interest, stamina, and fluency;

they also need to tackle harder books

that provide the opportunity to grow

more skillful as a reader.

Successful processing of the more

challenging text is made possible by an

expert teacher’s careful text selection

and strong teaching. If the book is too

difficult, then the processing will not be

proficient, no matter how much teaching

you do.

Consider the situation when

everystudent in the room (and

sometimesin the grade level) is

readingthe same book. Most of the

readers will not be encountering text

“Successful processing of the more challenging

text is made possible by an expert teacher’s

careful text selection and strong teaching.”

Figure 4 F&P Text Level Gradient

trtr_1123.indd 276 11/17/2012 10:54:46 AM

12

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

277

that,with teacher support, causes

them to expand their reading powers.

For some,the books are too easy;

for many,much too hard. There

are many reasons for whole-group

instruction, and we recommend that

it take place every day in interactive

read-aloud or reading minilessons.

However,ensuring that all students

develop an effectivereading process

requires differentiated instruction. One-

size-fits-all or single-text teaching does

not meet the varied needs of diverse

students.

Many teachers use levels to select

the books for students, but that

raises several more questions. First,

not all leveled books are equal. Just

because a book has a level does not

mean it is a high-quality selection.

Some leveledbooks are formulaic

or not accurately leveled. Teachers

need to look carefully at books in

the purchasing process to assure

they are well written and illustrated.

They also need to check to be sure

that the Fountas and Pinnell level

has been accurately determined. It

will be frustrating to select a book

and beginto use it with a group,

only to find it is too easy or too

difficult to support learning. Second,

when teachers understand the 10

text characteristics that are used to

determine the level,they understand

its demands on the reader and can

useit in a more powerful way in

teaching.

Understanding a text is far more

than noticing hard words and coming

up with information or a “main idea.”

Skilled teachers of guided reading

understand how a text requires a reader

to think—the demands that every text

makes on the reader. We consider an

understanding of text characteristics

an extremely important area of teacher

expertise.

Teachers do more than apply

mechanical formulas by looking at

sentence and word length (although

those are important); we recommend

an analysis that takes into account

text complexity. We have described 10

characteristics of text difficulty (see

Figure 5).

Teachers consider the

characteristics of genres and special

forms; some genres and forms are

more difficult than others, with

simpler and more complex texts

of every type. Teachers notice and

understand the text structure—

the way it is organized—as well

as underlying structures such as

compare and contrast. They assess

the level of content (what background

knowledge will be required) and the

themes and ideas. Highly abstract

themes and ideas make a text more

challenging. Many texts have complex

language and literary features such as

elaborate plots, hard-to-read dialogue,

or figurative language that make the

Figure 5 Ten Characteristics Related to Text Difficulty

trtr_1123.indd 277 11/17/2012 10:54:47 AM

13

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

278

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

texts more interesting and at the same

time more challenging.

Sentence complexity, too, is a

factor, one that is usually measured

by mechanical readability formulas.

Works with many embedded clauses

and long sentences are harder. Teachers

also consider the number of long,

multisyllabic, or hard to decode words

in a text and the complexity of the

vocabulary. Illustrations in fiction can

add meaning or mood to the text, and

graphics in nonfiction offer additional

complex information. Book and print

features play a role as well. The size of

print, layout, punctuation, and other

text features such as charts, diagrams or

sidebars—all go into the analysis of text

difficulty.

Using these characteristics, we

created the A to Z text gradient

to give teachers a useful tool for

guidedreading instruction and a

picture of student progress over time

(see Figure 6). Notice how Ronald has

progressed from kindergarten through

grade 8 in a high-quality instructional

program.

The gradient offers guidance in

selecting texts, but it’s important to

remember that levels are not written

in stone. Background experience

and unique characteristics of readers

figure into their processing of texts so

that most students read along a fairly

narrow range of levels, depending on

interest and whether they are working

independently or with strong support.

We would not situate a reader at a

single level and insist that all reading

be there.

The ability to analyzetexts

represents important teacher

knowledge that takes time to develop.

Many teachers of guidedreading have

spent a great dealof time analyzing

and comparingtexts using the 10

characteristics and have become

“quick” analyzers of texts. They

match up their understandings with

their knowledge of the students

in the group. When they teach a

guided reading lesson, they can plan

quickly what they need to say in

the introduction and anticipate key

understandings to talk about in the

discussion. When you understand

the inner workings of a text, you can

introduce it well and guide a powerful

discussion.

Teaching for a Processing

System: The Role of Facilitative

Talk in Expanding Reading

Power

At first, guided reading may be

perceived only as a process of

convening small groups, using

Figure 6 Record of Book-Reading Progress

trtr_1123.indd 278 11/17/2012 10:54:48 AM

14

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

279

leveled books, and following a lesson

framework. Often, teachers use the

small-group format, the steps of the

lesson, and a set of leveled books but

bring their old theory to this new

practice. Professional development

support does not go far enough to

enable them to do powerful teaching

beyond these initial steps. Guided

reading is much more. It is an

instructional context within which the

precise teaching moves and language

choices are related to the behaviors

observed, moment by moment, and

which guide the reader to engage in

problem solving that expands his or

her reading power.

The skilled teacher of guidedread-

ing makes decisions throughout the

lesson that are responsive to the learn-

ers. Each element supports readers in

a different way, with the goal of help-

ing them think and act for themselves.

You expertly shape the introduction

to support readers’ ability to success-

fully process the text. The introduction

sets the stage for effective reading of

the text. During reading, you can use

language to demonstrate, prompt,

and support the reader in efficient

processing.

Your language is also a critical

areaof your expertise. Through

preciselanguage, you facilitate

readers’problem-solving power

and their ability to initiate effective

actionsas they become self-

regulatingreaders (Clay, 2001).

Use language in specific ways

to demonstrate, show or teach,

prompt for, and reinforce strategic

actions. With brief yet powerful

facilitativelanguage, you can

scaffold students during the time you

sample oral reading. Short, focused

interactions with individuals allow

readers to learn how to problem solve

for themselves (Fountas & Pinnell,

2009). Some examples of precise

language that helps students build a

processing system are presented in

Figure 7.

As your students discuss the text,

you can use facilitative language

that promotes dialogue. Get readers

thinking and using what they know.

Through the discussion, they expand

comprehension. Your teaching points

address the precise needs of the learners

you teach. They involve responsive

teaching based on your observation

of the readers and the opportunities

offered by the text. Notice the examples

of specific language to support analytic

thinking in the discussion of a text (see

Figure 8).

“The ability to analyze texts represents

importantteacher knowledge that takes

timetodevelop.”

Figure 7 Facilitative Talk

trtr_1123.indd 279 11/17/2012 10:54:49 AM

FACILITATIVE TALK

Teach Prompt Reinforce

SEARCHING

FOR AND USING

MEANING

INFORMATION

You can try that again

and think what would

make sense.

Try that again and

think what would

make sense.

You tried that

again and now it

makes sense.

SEARCHING FOR

AND USING

VISUAL

INFORMATION

You can look for a

part you know. (Use

finger to cover last

part.)

Look for a part you

know.

You looked for

a part

you knew and it

helped you.

FLUENCY

You need to put your

words together so it

sounds like talking.

Listen to how I read

this.

Put your words

together so it

sounds like talking.

You put your

words together

and it sounds like

talking.

SELF-

MONITORING

It has to make sense

and look right, too.

Let me show you how

to check.

Does that make

sense and look

right?

That makes sense

and looks right.

15

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

280

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

Through word work, you help

readers develop flexibility with

wordsand word parts, noticing

syllables, working with letters and

sounds, andunderstanding the

morphemic structure of words. The

option to extend the understanding

of a text involves more than just

an assignment. Many teachers

of guidedreading have students

use theirreaders’ notebooks to

write abouttheir reading in a way

that supports and expands their

comprehension.

Using Self-Reflection to Grow

in Teaching Guided Reading

High-quality, highly effective

implementation of guided reading

involves a process of self-reflection.

You are very fortunate if you have a

colleague with whom you can talk

analytically about lessons. Each

time you work with a small group

of students, you can learn a little

more and hone your teaching skills.

(We believe that students who have

teachers who also are learning

are equally fortunate. That makes

the whole experience a lot more

exciting!)In Figures 9 and 10, we offer

some guidance for you to pause and

ponder.Ask yourself some critical

questions about the guided reading

lesson. You’ll find that you become

more aware of the skillful teaching

moves you have made, as well as

Figure 8 Examples of Language to Support Analytic Thinking About Text

Note. From Fountas & Pinnell (2012).

Figure 9 Pause and Ponder: Teaching

the Reader

Figure 10 Pause and Ponder: Results

of the Lesson

trtr_1123.indd 280 11/17/2012 10:54:50 AM

16

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

281

the thought that “I might have…” or

“tomorrow I will…”. Reflective teaching

is rewarding because you are learning

from teaching.

Providing Variety and

Choice in the Reading

Program

Educators have sometimes made

the mistake of thinking that guided

reading is the reading program or

that all of the books students read

should be leveled. We have argued

against the overuse of levels. We

have neverrecommended that the

school library or classroom libraries

be leveledor that levels be reported to

parents.

We want students to learn to select

books the way experienced readers

do—according to their own interests,

by trying a bit of the book, by noticing

the topic or the author. Teachers can

help students learn how to choose

books that are right for them to read

independently. This is a life skill. The

text gradient and leveled books are

a teacher’s tool, not a child’s label,

and should be deemphasized in the

classroom. Levels are for books, not

children.

Guided reading provides the

small-group instruction that allows

for a closer tailoring to individual

strengths and needs; however, students

also need age-appropriate, grade-

appropriate texts. Therefore, guided

reading must be only one component

of a comprehensive, high-quality

literacy effort that includes interactive

read-aloud, literature discussion in

small groups, readers’ workshop with

whole-group minilessons, independent

reading and individual conferences,

and the use of mentor texts for writing

workshop. Students learn in whole

group, small group, and individual

settings.

Guided reading instruction takes

place within a larger framework that

brings coherence to the students’

school experience. It does not stand

alone. The expert teacher is able to

draw students’ attention to important

concepts across instructional contexts.

For example, a teacher may help

students attend to how readers need to

think about not only what the writer

says (states), but also what he or she

means (implies) in contexts such as

these:

■

Guided reading (small group,

leveled books)

■

Literature discussion (small-group

book clubs or whole class, not

leveled books)

■

Interactive read-aloud (whole class,

not leveled books)

■

Independent reading with

conferences (individual, not leveled

books, self-selected)

■

Reading minilessons (whole class,

not leveled books)

In guided reading and

interactiveread-aloud, the teacher

selects the book; in other contexts,

students havechoice. They are taught

ways to assess a text to determine

whether it will be interesting and

readable. Whole-class minilessons

often involve using a whole range

of books as mentor texts. The

entire literacy/language program

representsasmooth, coherent whole

in which students engage a variety

of strategic actions to process a wide

variety of texts.

Growth Over Time

The lesson of guided reading

development over the years is that

it cannot be described as a series

of mechanical steps or “parts” of a

lesson. The lesson structure is only

the beginning of providing effective

small-group instruction for students of

all ages. Powerful teaching within the

lesson requires much more.

It is interesting to reflect on what

aspects of guided reading tend to be

easiest or hardest for teachers to take

on. Bryk et al. (2007) found empirical

evidence for teacher development of

some of the complexities of guided

reading. He and his colleagues

constructed an instrument called

the Developing Language and

Literacy Teaching rubrics and tested

it for reliability. A series of controlled,

systematic observations indicated that

the instrument distinguished between

“novices” and “experts” in several

contexts for literacy teaching.

A very helpful result of the study

was that the analysis of items revealed

a “scale” that provided evidence of

the dimensions of instruction from

less to more frequently observed

(item difficulty), and this item map

was consistent across teachers. The

researchers were able to demonstrate

increasing levels of sophistication.

In Figure 11, you see the chart for

“The lesson structure is only the beginning of

providing effective small-group instruction...

Powerful teaching within the lesson requires

much more.”

trtr_1123.indd 281 11/17/2012 10:54:51 AM

17

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

282

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

development of levels of expertise in

guided reading.

On the horizontal axis, you see

dimensions of instruction, and on the

vertical axis, you see the level of item

difficulty, meaning that it seemed to

take longer for teachers to develop this

area of expertise in guided reading, and

these items tended to separate novices

from more expert teachers. It seems that

early on, teachers take on tasks such as

book selection (aided by the levels and

the bookroom) and parts of the lesson

such as text introduction. We would

argue that even these components

require complex thinking and can be

improved once acquired. Effective

prompting for use of strategies also

raises the sophistication, and, finally,

acting “in the moment” to engage

students in a rich discussion and make

teaching points based on observation

are the most challenging on this scale.

In addition, when we consider that this

study was completed before a great deal

of new research on comprehension was

accomplished, the need for ongoing

professional development is compelling

indeed.

We realize that achieving a high

level of expertise in guided reading is

not easy. It takes time and usually the

support of a coach or staff developer.

Research indicates that it is fairly easy

to take on the basic structure of guided

reading, for example, the steps of

the lesson. However, that is only the

beginning of teacher expertise. Teaching

for strategic actions and “on your feet”

interaction with students is much more

challenging.

You bring an enormous and complex

body of understandings to the teaching

of guided reading. Yet, with appropriate

high-quality professional development

and ongoing support, it is possible for

every teacher to implement guided

reading more powerfully in every

classroom. Skilled teachers of guided

reading have the pleasure of seeing

shifts in their students’ reading ability

every week—sometimes every day.

Through guided reading, students

can learn to deeply comprehend texts.

And perhaps most importantly, they

experience the pleasure of reading well

every day.

To make the guided reading

journey successful, we call for

resources in the form of excellently

written, attractive, and engaging

leveled books and for access to high-

quality professional development

for teachers. Our own experience

Figure 11 Development of Expertise in Guided Reading

Note. From Bryk et al (2007).

“Teaching for strategic actions and

‘onyourfeet’interaction with students is

muchmore challenging.”

trtr_1123.indd 282 11/17/2012 10:54:51 AM

18

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

www.reading.org

283

indicates that one-to-one literacy

coaching with a highly trainedand

knowledgeable professionaldeveloper

is very effective.An important

federallyfundedstudy supports

theuseof coaches (Biancarosa,

Hough,Dexter & Bryk, 2008; see

www.literacycollaborative.org for a

summary). Teachers had professional

development and coaching over four

years to implement all elements of a

literacy framework. The research team

gathered data on 8,500 children who

had passed through grades K–3 in 17

schools; they collected fall and spring

Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early

Literacy Skills (DIBELS) and Terra Nova

data from these students as well as

observational data on 240 teachers. The

primary findings showed that:

■

The average rate of student

learningincreased by 16% in the

first implementation year, 28%

in the second year, and 32% in

the third year—very substantial

increases.

■

Teacher expertise increased

substantially, and the rate of

improvement coincided with

the extent of coaching teachers

received.

■

Professional communication

among teachers in the schools

increased over the three-year

implementation, and the literacy

coordinator (coach) became

more central in the schools’

communication networks.

Guided reading was only one

component of the literacy framework

implemented in the schools researched

in the preceding study, but it was

an important one. The importance

of the literacy coach, who conducts

professional development sessions,

models good teaching, and most

importantly observes teachers in

the classroom and dialogues with

them to collegially mentor their

growth inunderstanding and

implementation of effective teaching,

appeared to be paramount in the

process. And even these schools

were only at thebeginning of the

journey. However, the study shows

that achieving substantial schoolwide

growth ispossible if a community of

educatorsare willing to undertake the

journey.

The Beginning

In this article, we have described

somewonderful changes that have

brought teaching closer to students. If

we take a romantic view, we could say

that once we have the book room, small-

group lessons, and leveled booksand

things are running smoothly, we have

arrived in the implementationof guided

reading. However, the heart of this

article is what we have learned from

many years of engaging teachers and

students in guided reading—what its

true potential is, and what it takes to

realize it. That’s the reality.

In the case of guided reading,

facingreality reaps endlessly positive

rewards. Facing reality means that

thereis more exciting learning to do.

Teaching and managing educational

systems is energizing when we are

working collaboratively toward new

goals. The accomplishments we have

already made simply give way to new

insights.

You may have made a very

goodbeginning in using guided

reading to develop your students’

reading power, and that is a

satisfying accomplishment.It is

alsoadevelopmentthat enables

youtohave important insights that

you can build upon. As you look

at your educationalprogram, you

may benoticing some of the issues

we havedescribed here. That can

put youonthe path to work toward

evenhigher goals on behalf of your

students. We hope youare excited

toknow that morechallenges

lie aheadin your growing

professionalexpertise and thatthere

aretools to help you meet those

challenges.

REFERENCES

Biancarosa, G., Hough, H., Dexter, E., & Bryk,

A. (2008, March). Assessing the value-added

effects of coaching on student learning. Paper

presented at the meeting of the National

Reading Conference, Orlando, FL.

Brown, A.L., & Campione, J.C. (1996).

Psychological theory and the design of

innovative learning environments: On

procedures, principles and systems. In

Glaser, R. (Ed.), Innovations in learning: New

environments for education (pp. 289–325).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bryk, A., Kerbow, D., Pinnell, G.S.,

Rodgers,E.,Hung, C., Scharer, P.L.,

et al. (2007). Measuring change in the

instructionalpractices of literacy teachers.

Unpublished manuscript.

Clay, M.M. (1991). Becoming literate: The

construction of inner control. Auckland, New

Zealand: Heinemann.

Clay, M.M. (1993). An Observation Survey of

Early Literacy Achievement. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Clay, M.M. (1998). Different paths to common

outcomes. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Clay, M.M. (2001). Change over time in children’s

literacy development. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

“Achieving substantial schoolwide growth is

possible if a community of educators are willing

to undertake the journey.”

trtr_1123.indd 283 11/17/2012 10:54:52 AM

19

GUIDED READING: THE ROMANCE AND THE REALITY

284

The Reading Teacher Vol. 66 Issue 4 Dec 2012 / Jan 2013

T

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (1996). Guided

reading: Good first teaching for all children.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2001). Guiding

readers and writers: Teaching comprehension,

genre, and content literacy. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2009). Prompting

guide part 1: For oral reading and early writing.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2011). Fountas

andPinnell benchmark assessment systems

1 and 2 (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2012). Prompting

guide part 2: For comprehension. Portsmouth,

NH: Heinemann.

Holdaway, D. (1979). Foundations of literacy.

Sydney, Australia: Ashton Scholastic.

Kaye, E.L. (2006). Second graders’ reading

behaviors: A study of variety, complexity, and

change. Literacy Teaching and Learning, 10(2),

51–75.

Newkirk, T. (2011). The art of slow reading.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Pinnell, G.S., & Fountas, I.C. (2011). The

continuum of literacy learning, grades preK-8: A

guide to teaching (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Rasinski, T., & Hamman, P. (2010). Fluency:

Why it is “Not Hot.” Reading Today, 28, 26.

Rosenblatt, L.M. (1994). The transactional

theory of reading and writing. In R.B.

Ruddell, M.R. Ruddell, & H. Singer

(Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of

reading (4th ed., pp. 1057–1092). Newark,

DE: International Reading Association.

doi:10.1598/0872075028.48

Sperling, M., & Freedman, S.W. (2001). Research

on writing. In Richardson, V. (Ed.), Handbook

of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 370–389).

Washington, DC: American Educational

Research Association.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society:

The development of higher psychological

processes.Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Wollman, J.E. (2007). “Are we on the same

bookand page?” The value of shared

theoryand vision. Language Arts, 84(5),

410–418.

trtr_1123.indd 284 11/17/2012 10:54:52 AM

20