Employment Hysteresis

from the Great Recession

Danny Yagan

University of California, Berkeley, and National Bureau of Economic Research

This paper uses US local areas as a laboratory to test for long-term im-

pacts of the Great Recession. In administrative longitudinal data, I es-

timate that exposure to a 1 percentage point larger 2007–9 local un-

employment shock reduced 2015 working-age employment rates by

over 0.3 percentage points. Rescaled, this long-term recession impact

accounts for over half of the 2007–15 US age-adjusted employment de-

cline. Impacts were larger among older and lower-earning individuals

and typically involved a layoff but are present even in a mass-layoffs

sample. Disability insurance and out-migration yielded little income

replacement. These findings reveal that the Great Recession imposed

employment and income losses even after unemployment rates sig-

naled recovery.

I. Introduction

The US unemployment rate spiked from 5.0 percent to 10.0 percent over

the course of the Great Recession and then returned to 5.0 percent in

2015. However, the US employment rate (employment-population ratio)

I thank Patrick Kline, David Autor, David Card, Raj Chetty, Hilary Hoynes, Erik Hurst,

Lawrence Katz, Matthew Notowidigdo, Evan K. Rose, Jesse Rothstein, Emmanuel Saez, An-

toinette Schoar, Lawrence Summers, Till von Wachter, Owen Zidar, Eric Zwick, seminar

participants, and anonymous referees for helpful comments. Rose, Sam Karlin, and Carl

McPherson provided outstanding research assistance. I acknowledge financial support from

the Laura and John Arnold Foundation and the Berkeley Institute for Research on Labor and

Employment. This work is a component of a larger project examining the effects of tax expen-

ditures on the budget deficit and economic activity; all results based on tax data in this paper

are constructed using statistics in the updated SOI (Statistics of Income) Working Paper “The

Electronically published September 13, 2019

[ Journal of Political Economy, 2019, vol. 127, no. 5]

© 2019 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0022-3808/2019/12705-0012$10.00

2505

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

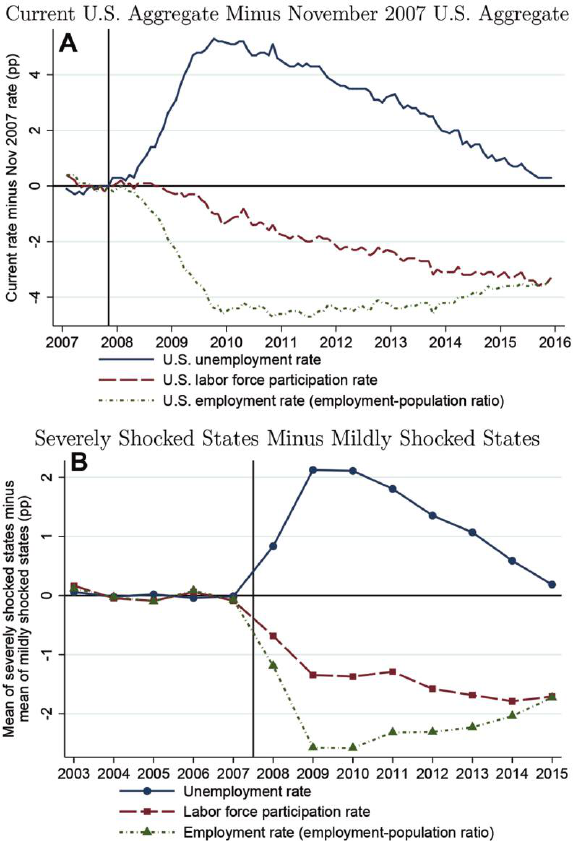

did not exhibit similar recovery. Figure 1A shows that the employment

rate declined 3.6 percentage points between 2007 and 2015, as millions

of adults exited the labor force.

1

Population aging explains a minority of

the employment rate decline: weighting 2015 ages by the 2007 age distri-

bution reduces the decline to 2.0 percentage points, and the unadjusted

age 25–54 employment rate declined by 2.6 percentage points. The de-

cline was concentrated among the low skilled (Charles, Hurst, and Noto-

widigdo 2016). The decline’s persistence contrasts with employment rate

recovery after earlier recessions— leading history-based analyses such as

Fernald et al. (2017) to doubt the possibility of employment “hysteresis”:the

Great Recession having depressed long-term employment despite the

unemployment recovery.

2

This paper tests whether the Great Recession and its underlying sources

caused part of the 2007–15 age-adjusted decline in US employment or

whether that decline would have prevailed even in the absence of the

Great Recession. It is typically difficult to test for long-term employment

impacts of recessions, for the simple reason that recession-independent

(“secular”) forces may also affect employment over long horizons (Ramey

2012). For example, the US employment rate rose by 2 percentage points

from the start of the 1981–82 recession to the late 1980s, as women con-

tinued to enter the labor force. In the context of the Great Recession, sec-

ular nationwide skill-biased shocks such as technical or trade changes

could have caused the entire 2007–15 employment decline, rather than

the recession.

I attempt to overcome this challenge by leveraging spatial variation in

Great Recession severity, along with data that minimize selection threats.

All US local areas by definition experienced the same secular nationwide

shocks, but some local areas experienced more severe Great Recession

shocks than other local areas. For example: Phoenix, Arizona—America’s

sixth-largest city—experienced a relatively large unemployment spike dur-

ing the Great Recession, while San Antonio, Texas—America’s seventh-

largest city—did not. A cross-area research design has the potential to dis-

tinguish recession impacts from secular nationwide shock impacts.

In the first part of the paper, I show, using public state-year aggregates,

that a cross-area research design is indeed fertile ground for studying the

labor market consequences of the Great Recession. Defining state-level

1

Variable definitions are standard and pertain to the age-16-and-over civilian noninsti-

tutional population.

2

This definition of hysterisis encompasses permanent impacts as well as transitory im-

pacts that last longer than elevated unemployment.

Home Mortgage Interest Deduction and Migratory Insurance over the Great Recession,” ap-

proved under Internal Revenue Service (IRS) contract TIRNO-12-P-00374 and presented at

the National Tax Association. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author

alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRS or the US Treasury Department. Data

and programs are provided as supplementary material online.

2506 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

shocks as 2007–9 employment growth forecast errors in an autoregressive

system (Blanchard and Katz 1992), I find that 2015 employment rates re-

mained low in the US states that experienced relatively severe Great Re-

cession shocks—even though between-state differences in unemploy-

ment rates had returned to normal (and despite normal between-state

population reallocation). Hence, the cross-area patterns of employment,

unemployment, and labor force participation closely mirrored the aggre-

gate cross-time patterns of figure 1A. The persistent cross-area employ-

ment rate difference departs from the Blanchard-Katz finding of rapid re-

gional convergence.

The state-year evidence does not imply persistent employment impacts

of the Great Recession, because of two potential forms of cross-area com-

position bias: post-2007 sorting on labor supply and pre-2007 sorting on

human capital. First, severe Great Recession local shocks caused long-

term declines in local costs of living (Beraja, Hurst, and Ospina 2016),

which may have disproportionately attracted or retained those secularly

out of the workforce, such as the disabled and the retired (Notowidigdo

2011).

3

Even without such post-2007 sorting on labor supply, severe Great

Recession local shocks may have happened to hit areas with particularly

large preexisting concentrations of individuals affected by secular nation-

wide shocks. For example, the Great Recession disproportionately struck

local areas that had experienced housing booms (Mian and Sufi 2014) at-

tracting low- and middle-skill construction labor, and low- and middle-skill

laborers have been relatively adversely affected by secular nationwide

shocks in recent decades (e.g., Katz and Murphy 1992).

4

Under either type

of cross-area sorting, severe Great Recession local shocks may not have

caused local residents’ 2015 nonemployment.

I therefore turn for the second part of the paper to longitudinal linked

employer-employee data in order to control for prominent dimensions

of cross-area sorting. The longitudinal component allows one to measure

individuals’ employment over time regardless of whether and where in

the United States they migrated—directly controlling for post-2007 sort-

ing on labor supply. The linked employer-employee component allows

one to control for fine interactions of age, 2006 earnings, and 2006 in-

dustry—proxies for pre-2007 human capital.

Specifically, I draw a 2 percent random sample of individuals from de-

identified federal income tax records spanning 1999–2015. The main

3

For example, “Warren Buffett’s Advice to a Boomer: Buy Your Sunbelt Retirement

Home Now” (Forbes, January 27, 2012; http://www.forbes.com/site s/janetnovack/2 012

/01/27/warren-buffetts-advice-to-a-boomer-buy-your-sunbelt-retirement-home-now/).

4

For example, “ You can’t change the carpenter into a nurse easily ...monetary policy

can’t retrain people” (Charles Plosser in “The Fed’s Easy Money Skeptic,” Wall Street Jour-

nal, February 12, 2011; http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1000142405274870470930457612

4132413782592).

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2507

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

FIG.1.— Persistent employment rate declines after the Great Recession (pp: percentage

points). A, Data are from official seasonally adjusted BLS US labor force statistics from Jan-

uary 2007 through December 2015. The data are monthly and refer to the adult (161) ci-

vilian noninstitutional population. The vertical line denotes November 2007, the last

month before the Great Recession. For each outcome and month, the graph plots the cur-

rent value minus the November 2007 value, so that each data point in these series denotes a

percentage point change relative to November 2007. See online figure A.1 for age-adjusted

versions and versions restricted to 25–54-year-olds. B, US states are divided into severely

(below-median) and mildly (above-median) shocked states, based on 2007–9 state-level

employment growth forecast errors in the autoregressive system of Blanchard and Katz

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

outcome of interest is employment at any point in 2015, equal to an indi-

cator for whether the individual had any W-2 earnings or any 1099-MISC

independent contractor earnings in 2015. The main sample is restricted

to those aged 30–49 (“working age”) in 2007 in order to confine the 1999–

2015 employment analysis to those between typical schooling and retire-

ment ages, and it is restricted to American citizens in order to minimize

unobserved employment in foreign countries. The analysis allows for

within-state variation by using the local-area concept of the commuting

zone (CZ): 722 county groupings that approximate local labor markets

and are similar to metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) but span the en-

tire continental United States. I use the universe of information returns

to assign individuals to their January 2007 CZ. Each individual’s Great Re-

cession local shock equals the percentage point change in her 2007 CZ’s

unemployment rate between 2007 and 2009 as recorded in the Bureau

of Labor Statistics (BLS) Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS).

I obtain 2006 four-digit North American Industry Classification System

(NAICS) industry codes for half of 2006 W-2 earners by linking W-2s to

employers’ tax returns.

I find that, conditional on 2006 age-earnings-industr y fixed effects, a

1 percentage point higher Great Recession local shock caused the aver-

age working-age American to be 0.39 percentage points less likely to be

employed in 2015. The estimate is very statistically significant, approxi-

mately linear in shock intensity, robust across numerous specifications,

and large: those living in 2007 in largest-shock-quintile CZs were 1.7 per-

centage points less likely to be employed in 2015 than initially similar in-

dividuals living in 2007 in smallest-shock-quintile CZs. Placebo tests indi-

cate no relative downward employment trend in severely shocked areas

before the recession, corroborating identification. Controlling for 2015

local unemployment rates suggests that the incremental 2015 nonem-

ployment took the form of labor force exit rather than long-term unem-

ployment. I similarly find impacts on 2015 wage and contractor earnings:

23.6 percent (2$997) of the individual’s preperiod earnings for every

1 percentage point higher shock.

One could be concerned that the foregoing within-industry analysis

fails to sufficiently control for pre-2007 sorting on human capital, as jobs

and therefore skill types in some industries are geographically differenti-

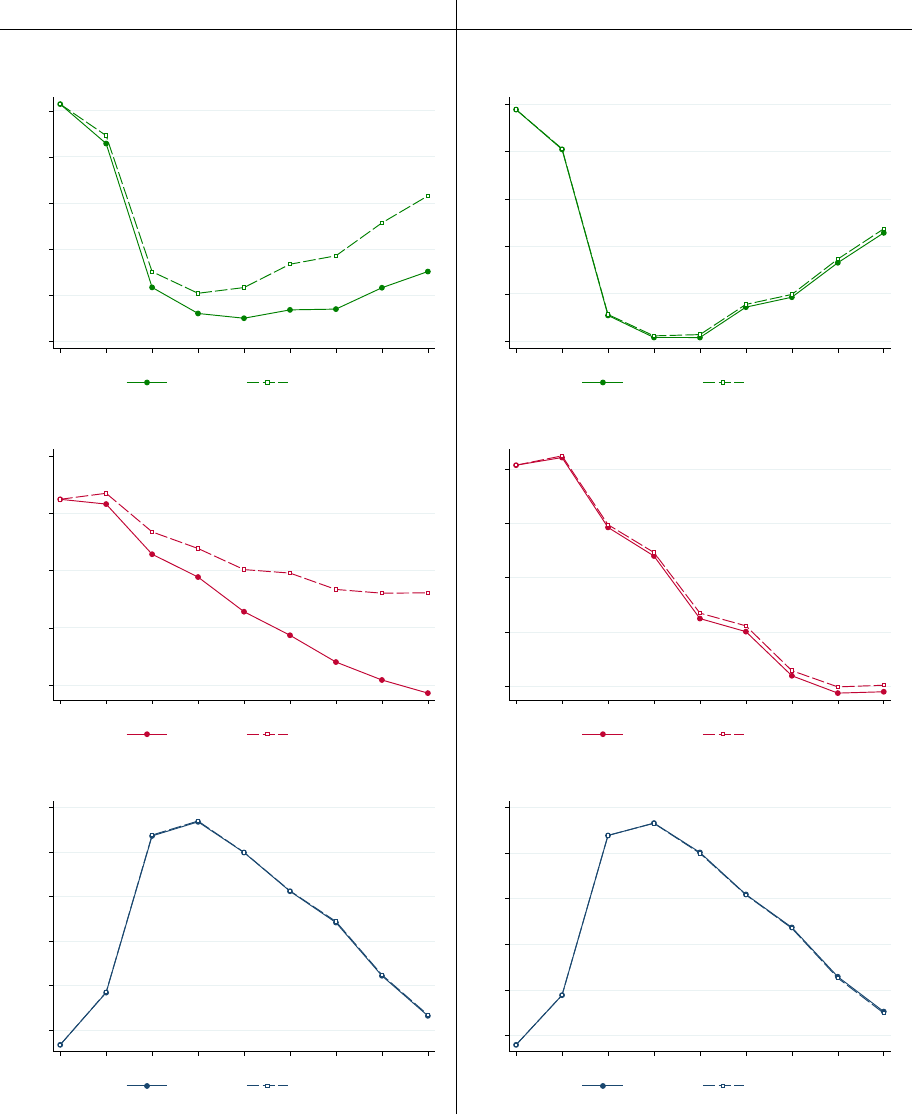

ated. Thus, as a novel robustness check, I approximate a within-job anal-

ysis, using a sample of 2006 workers at retail chain firms such as Walmart

(1992) estimated on 1976–2007 BLS LAUS state-year labor force statistics. For each out-

come and year, the graph uses LAUS to plot the unweighted mean in severely shocked

states, minus the same mean in mildly shocked states. Each series is demeaned relative to

its pre-2008 mean. See online appendixes A and B for more details.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2509

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

and Safeway that employ workers with similar skills to perform similar

tasks at similar salaries in many different local areas. Adding firm fixed ef-

fects in the retail sample attenuates the retail-sample employment effect

by 0.05 percentage points, or one-half of one standard error, to 20.36 per-

centage points, similar to the main estimate of 20.39 percentage points.

Certain comparisons suggest that the true average employment impact

could be closer to 20.30 percentage points per percentage point unem-

ployment rate shock. Naive extrapolation of the 20.30-for-1 and 20.39-

for-1 magnitudes would explain 58–76 percent of the US 2007–15 working-

age annual employment rate decline as a long-term impact of the Great

Recession. The actual implied aggregate impact depends on general equi-

librium amplification or dampening.

The recession’s impacts were highly uneven within local areas. The em-

ployment and earnings impacts were most negative for older individuals

and those with low2006 earnings. The latter pattern indicates thatthe Great

Recession induced a long-term increase in employment and earnings in-

equality across skill levels, not merely within skill levels across space. Im-

pacts do not appear smaller among mobile subgroups such as renters or

the childless.

Adjustment via migration and social insurance appears highly incom-

plete in replacing lost income. I find no statistically significant impact of

Great Recession local shocks on out-migration from one’s 2007 CZ, and

earnings in other CZs did not replace any lost 2015 earnings relative to

those exposed to smaller Great Recession local shocks. Great Recession

localshockscausedsignificantlyhigherunemploymentinsurance(UI)ben-

efits 2008–10 before UI benefits expired and insignificantly higher So-

cialSecurityDisabilityInsurance(SSDI)benefitsinallyears. I estimate that

2015 SSDI replaced 2 percent of lost 2015 earnings, or up to 6 percent at

the 95 percent confidence upper bound.

Finally, I find that most of the 2015 incrementally nonemployed in se-

verely shocked areas had been laid off at some point during 2007–14 and

were nonemployed in the entire 2013–15 period. However, higher layoff

rates do not appear to explain the results, as the impacts hold within a

sample of laid-off individuals. In particular, I find equally large impacts

when comparing workers who were displaced in a 2008–9 mass layoff.

Hence, interactions with area-level economic conditions appear key to any

full explanation of the long-term impacts—such as human capital decay

during extended nonemployment or persistently low local labor demand.

The paper’s findings constitute evidence of long-term employment im-

pacts of the Great Recession (cf. Fernald et al. 2017) and add to a large lit-

erature on the incidence of labor market shocks. Earlier work had found

long-term impacts on individuals’ earnings (Topel 1990; Jacobson, La-

Londe, and Sullivan 1993; Neal 1995; Kahn 2010; Davis and von Wachter

2011) and sometimes on local areas’ employment rates (Blanchard and

2510 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Katz [1992] vs. Black, Daniel, and Sanders [2002] and Autor and Duggan

[2003]) and individuals’ employment rates (Ruhm [1991] and Walker

[2013] vs. Autor et al. [2014] and Jarosch [2015]). I provide evidence of

long-term impacts of Great Recession local shocks on individuals’ employ-

ment rates, likely via labor force exit. This evidence reinforces the view of

Autor and Duggan and a large literature dating back at least to Bowen and

Finegan(1969) and Phelps(1972)that transitoryadverseaggregateshocks

can have persistent negative employment impacts even after unemploy-

ment recovers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II uses state-year

data to show that cross-area employment patterns mirrored aggregate

cross-time employment patterns 2007–15. Section III details the empiri-

cal design and longitudinal linked employer-employee data. Section IV

estimates overall impacts. Section V estimates impact heterogeneity. Sec-

tion VI investigates adjustment margins. Section VII documents layoff

and nonemployment trajectories. Section VIII discusses candidate mech-

anisms. Section IX concludes the paper.

II. Local Labor Markets Mirrored the Aggregate

This paper uses cross-area variation in Great Recession severity to test

whether the recession and its underlying sources caused part of the

2007–15 decline in the US employment rate displayed in figure 1A. I be-

gin by testing whether figure 1A’s aggregate cross-time employment pat-

terns have been mirrored across US local areas: did the local areas that

experienced severe Great Recession shocks also experience persistent

declines in employment and participation rates but not unemployment

rates, relative to mildly shocked areas? If so, then local labor markets may

indeed serve as a fruitful laboratory for understanding sources of aggre-

gate employment patterns.

A large literature has studied local labor market dynamics after local

employment shocks. The canonical analysis of Blanchard and Katz (1992)

found, in state-year data for 1976–90, that when a state experiences an ad-

verse employment shock, its population falls relative to trend but its un-

employment, participation, and employment rates return to parity with

those of other states in 5–6 years. That is, local shocks leave local areas

smaller but no less employed. This conclusion has been replicated in Eu-

ropean data (Decressin and Fatas 1995) and in a longer US state-year time

series (Dao, Furceri, and Loungani 2017). However, other papers have

found long-term participation and employment impacts of local shocks:

Black et al. (2002), Autor and Duggan (2003), and Autor, Dorn, and Han-

son (2013) found long-term impacts of specific types of US local shocks

on local SSDI enrollment, participation, and/or employment rates.

Hence, the existing literature presents a mixed picture.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2511

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

This section documents local labor market dynamics after Great Reces-

sion local employment shocks, with greater detail presented in online

appendixes B and C. For comparability to the broadest line of previous

work, I conduct this analysis at the state level and categorize states into

severely shocked states and mildly shocked states, using unforecasted

state-level changes in 2007–9 employment, derived from the autoregres-

sive system of Blanchard and Katz (1992). I estimate Blanchard and Katz’s

log-linear autoregressive system in state employment growth, state unem-

ployment rates, and state participation rates in LAUS data for 1976–2007.

The LAUS data are the annual BLS LAUS series of employment, popula-

tion, unemployment, and labor force participation counts in 1976–2015

for 51 states (the 50 states plus the District of Columbia). Annual counts

are calendar year averages across months. I then compute 2008 and 2009

employment growth forecast errors for each state—equal to each state’sac-

tual log employment growth minus the system’s prediction for that state—

and sum the tw o to obtain each state’s 2007–9 employment shock. Ro ughly

speaking, each state’s shock equals the state’s 2007–9 log employment

change minus the state’s long-run trend. Then, for expositional simplicity,

I group the 26 states with the most-negative shocks (e.g., Arizona) into the

severely shocked category and the remaining states (e.g., Texas) into the

mildly shocked category.

Figure 1B displays the 2003–15 time series of unemployment, partici-

pation, and employment rate differences between severely shocked states

and mildly shocked states. For each outcome and year, the graph plots the

unweighted mean among severely shocked states minus the unweighted

mean among mildly shocked states (the graph looks nearly identical

weighting by population). Within each series, I subtract the mean pre-

2008 severe-minus-mild difference from each data point, so each plotted

series has a mean of zero before 2008.

The figure shows that the unemployment rate in severely shocked states

relative to that in mildly shocked states spiked in 2008, peaked in 2009–

10, and returned by 2015 to its mean prerecession severe-mild difference.

Yet the 2015 employment and participation rates in severely shocked

states remained 1.74 percentage points below the corresponding rates in

mildly shocked states, relative to the mean prerecession severe-mild dif-

ferences. The implied 2015 cross-area employment gap is large: 2.01 mil-

lion fewer adults were employed in severely shocked states than in mildly

shocked states, relative to full recovery to the prerecession severe-mild em-

ployment rate difference.

Hence, the cross-area (severe-minus-mild) patterns of unemployment,

participation, and employment of figure 1B do indeed broadly mirror

the aggregate cross-time (current-minus-2007) patterns of figure 1A.More-

over, in the same sense that the aggregate employment aftermath of the

Great Recession appears to contrast with the aftermath of the early-1980s

2512 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

and early-1990s recessions, so too does the cross-area aftermath of the

Great Recession appear to contrast with the cross-area aftermath of those

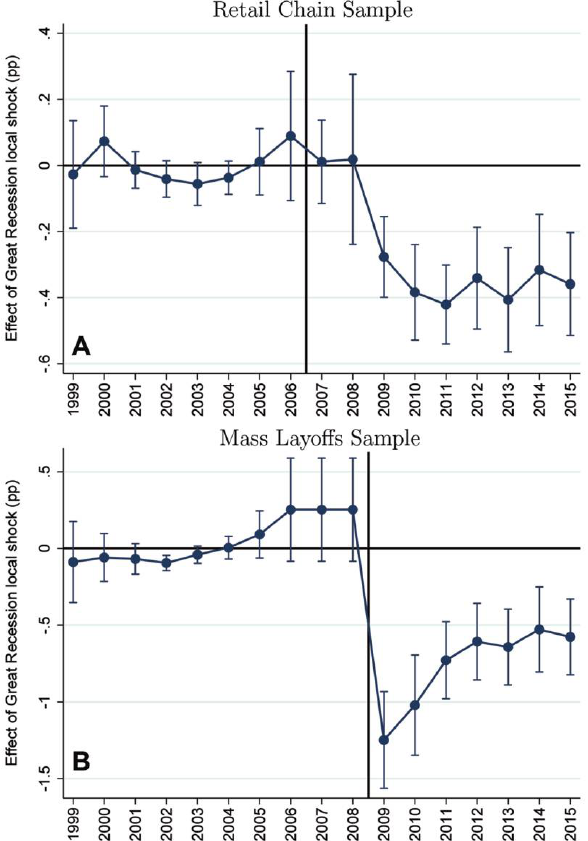

earlier recessions. Figure 2A repeats the employment rate series of fig-

ure 1B for the aftermath of the 1980s and 1990s recessions, treating the

early-1980s recessions as a single recession. The figure shows that cross-

state employment rates fully converged 4 years after the early-1990s reces-

sion and had converged by 1.65 percentage points (78 percent of the

t 5 0 divergence) 6 years after the early-1980s recession. Six-year conver-

gence aftertheGreatRecession wassmallerinbothabsoluteterms(0.85per-

centage points) and relative to the t 5 0 divergence (33 percent).

Blanchard and Katz(1992) suggest that the historical convergence mech-

anism is rapid population reallocation: a 21 percent state population

change relative to trend follows every 21 percent employment shock within

5–6 years.

5

Therefore,anatural possible explanationfor local employment

rate persistence after the Great Recession is that population reallocation

has slowed. Figure 2B investigates this possibility by plotting detrended

2007–14populationchanges—equalto eachstate’s2007–14percentchange

inpopulationminusthe2000–7percent changein thestate’spopulation—

versus the state’s 2007–9 employment shock. The graph shows that popu-

lation reallocation after the Great Recession was similar to the historical

benchmark: each 21 percent 2007–9 employment shock was on aver-

age accompanied by a 21.016 percent (robust standard error: 0.260) de-

trended population change.

6

Figure 2C shows the same conclusion when

the original Blanchard-Katz time range—1976–90, well before the recent

housing boom—is used to estimate state-specific population trends in the

Blanchard-Katz system. Population in severely shocked states fell in 2007–

15 relative to trend and relative to that of mildly shocked states, as much

as in the Blanchard-Katz benchmark.

To sum up, this section has found that aggregate 2007–15 cross-time

unemployment, participation, and employment rate patterns have been

mirrored in cross-area unemployment, participation, and employment

rate patterns over the same time period. Participation and employment

rates remained persistently low in the US states that experienced relatively

5

The unit elastic population response holds when reestimating the Blanchard and Katz

system on updated data for 1976–2015. The suggested causal chain is as follows: a state

(e.g., Michigan) experiences a one-time random-walk contraction in global consumer de-

mand for its locally produced traded good (e.g., cars), which induces a local labor demand

contraction and wage decline, which in turn induces a local labor supply (population) con-

traction, which then restores the original local wage and employment rate.

6

When not detrended, state population changes were largely uncorrelated with 2007–9

employment shocks, also shown in Mian and Sufi (2014) for the 2007–9 period only.

Blanchard and Katz (1992) find adjustment via population changes relative to trend. Gross

(out-)migration rates have declined modestly since 1980 (Molloy, Smith, and Wozniak

2011), but gross flows are still an order of magnitude larger than the net flows (population

reallocations) predicted by history in response to 2007–9 shocks.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2513

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

FIG.2.— Great Recession local adjustment in comparison to history. A, States are divided

into severely (below-median) and mildly (above-median) shocked states based on the sum

of 2008 and 2009 employment growth forecast errors, as described in figure 1B,repeating

the process for the early-1980s recessions (1980–82, treated as a single recession) and the

early-1990s (1990–91) recession. Then, for each recession and year relative to the reces-

sion, the graph plots the unweighted mean LAUS employment rate in severely shocked

states, minus the same mean in mildly shocked states. Each series is demeaned relative

to its prerecession mean. For comparability across recessions, year 0 denotes the last reces-

sion year (1982, 1991, or 2009), while year 21 denotes the last prerecession year (1979,

1989, or 2007); intervening years are not plotted. Online figure A.5 plots analogous graphs

for labor force participation, unemployment, employment growth, and population growth.

The post-2001-recession experience exhibited incomplete convergence before being inter-

rupted by positively correlated 2007–9 shocks (not shown). B, This graph uses LAUS data

to plot detrended 2007 –14 population changes—equal to each state’s 2007–14 percent

change in population minus its 2000–7 percent change in population—versus the state’s

2007–9 employment shock. Overlaid is the unweighted best-fit line, with a slope of 1.016

(robust standard error of 0.260). C, The dotted lines plot Blanchard-Katz (1992) history-

based predictions (Pred.) for state-level responses to a 21 percent 2007–9 state-level em-

ployment shock, based on feeding the 1976–90-estimated Blanchard-Katz system a 2.41

percent employment shock followed by a 2.59 percent employment shock. The solid lines

plot mean actual (Act.) state-level responses based on reduced-form regressions of 2008–14

state-level outcomes on 2007–9 state-level shocks. See online appendix B for more details.

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

severe employment shocks 2007–9, even though unemployment rates con-

verged across space. Reduced population reallocation does not explain

the local persistence. The cross-area aftermath of the Great Recession de-

parts from the broad historical findings of Blanchard and Katz (1992),

but they accord with findings of Black et al. (2002), Autor and Duggan

(2003), and Autor et al. (2013) from specific contexts. I now turn to iden-

tifying whether Great Recession local shocks caused individuals to have

lower 2015 employment.

III. Isolating Impacts of Great Recession

Local Shocks

The previous section showed that local labor markets were microcosms

of aggregate employment patterns in 2007–15: 2015 employment rates

remained unusually low in US local areas that experienced an especially

severe 2007–9 employment shock. However, that cross-sectional fact does

not imply that individuals were nonemployed in 2015 because of where

they were living during the Great Recession, in light of two selection

threats. First, the disabled, retirees, and others secularly out of the labor

force may have disproportionately stayed in or moved to severely shocked

areas in order to enjoy low living costs while forgoing employment. Even

without selective migration on post-2007 labor supply, severely shocked

areas may have been disproportionately populated before the recession

by individuals who subsequently suffered large nationwide contractions

for their skill types, such as construction workers or routine laborers, that

would have occurred even in the absence of the recession. Under either

selection threat, the 2015 residents of severely shocked areas might be

nonemployed now regardless of geography.

This section specifies my empirical strategy for using longitudinal

linked employer-employee data to isolate causal effects of Great Reces-

sion local shocks on individuals’ 2015 employment; 2015 is the most re-

cent year of data available. Additional details are listed in online appen-

dixes D and E, including design foundations in potential outcomes.

A. Empirical Design

I adopt an empirical design that closely follows earlier work using longi-

tudinal individual-level data to estimate long-term impacts of labor mar-

ket shocks (e.g., Jacobson et al. 1993; Davis and von Wachter 2011; Autor

et al. 2014). I estimate regressions of the form

y

i2015

5 bSHOCK

ci2007ðÞ

1 v

gi2006ðÞ

1 e

i2015

, (1)

where y denotes an employment or related outcome, i denotes an indi-

vidual, SHOCK

c(i2007)

is the Great Recession shock to the individual’s 2007

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2515

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

local area c, v

g(i2006)

denotes fixed effects for groups g of individuals de-

fined using individual pre-2007-determined characteristics, and e

i2015

is

a disturbance term. Here, b is the coefficient of interest: the causal effect

on one’s 2015 outcomes of living in 2007 in a local area that experienced

a one-unit-larger Great Recession shock.

I interpret b as the causal effect of Great Recession local shocks and

their underlying sources, which are empirically indistinguishable,

7

and I

refer to this effect as the causal effect of Great Recession local shocks. Al-

ternative interpretations include b reflectin g differential prerecession trends

(e.g., a downward pre-2007 employment trend in severely shocked areas)

or independent correlated local shocks (e.g., post-2009 floods in severely

shocked areas). However, my interpretation of b is sensible because se-

verely shocked and mildly shocked areas exhibited relatively similar pre-

recession trends in the outcomes of interest (shown below in Sec. IV.A) and

because post-2010 unemployment rates converged monotonically across

severely shocked and mildly shocked areas. Moreover, adverse 2010–

15 industry-based shift-share shocks are not positively correlated with ad-

verse Great Recession local shocks.

As in earlier work, the identifying assumption is selection on observ-

ables: individuals were as good as randomly assigned across local areas

within groups g. Also as in earlier work, I aim to satisfy this assumption, us-

ing rich longitudinal data to define groups finely along dimensions (e.g.,

age, prerecession earnings, and prerecession industry) that could be cor-

related with both Great Recession local shocks and omitted secular na-

tionwide shocks, and to restrict attention to subsamples in which the iden-

tifying assumption is particularly likely to hold. I use event study graphs

to evaluate potentially confounding prerecession trends.

B. Samples

I implement the pape r’s empirical design by using selected deidentified

data from federal income tax records spanning 1999–2015. Iconstructthree

samples as follows. All three samples are balanced panels of individuals.

Main sample .—The main sample comprises a 2 percent random sample

from what I call the full sample. The full sample comprises all American

citizens aged 30–49 (“working age”) on January 1, 2007, who had not died

by December 31, 2015, and who had a valid payee ZIP code on at least one

information return that indicates continental US residence in January

7

For example, if the underlying source of Great Recession local shocks was persistent

local spending contractions (Mian, Rao, and Sufi 2013), then 2015 employment could

in principle be depressed because of layoffs during the Great Recession or because local

spending remained depressed through 2015, among other possibilities.

2516 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

2007.

8

The age restriction confines the 1999–2015 employment analysis to

those older than schooling age and younger than retirement age. Birth,

death, andcitizenship data are drawn from Social Security Administration

(SSA) records housed alongside tax records.

9

Restricting attention to

those alive in 2015 excludes analysis of mortality effects, likely a conserva-

tive choice (Sullivan and von Wachter 2009). I describe geocoded informa-

tionreturnsin the next subsection.I randomly sampleindividuals fromthe

full sample by using the last two digits of the individual’s masked identifica-

tion number, yielding a main sample comprising 1,357,974 individuals.

Retail chain sample.—The retail chain sample comprises individuals in

the full sample whose main employer in 2006 was a retail chain firm and

who lived outside the local area of the retail chain firm’s headquarters. It

is constructed as follows. For every individual in the full sample with a

2006 W-2 form, I attempt to link the masked employer identification num-

ber (EIN) on the individual’s highest-paying 2006 W-2 to at least one busi-

ness return in the universe of business income tax returns 1999–2007.

10

I use the NAICS code on the business income tax return to restrict atten-

tion to workers whose 2006 firms operated in the two-digit NAICS retail

trade industries (44 or 45), for example, Walmart and Safeway.

11

I further

exclude employees living in 2007 in the CZ of their employer’s headquar-

ters, using the workers’ payee ZIP codes across their information returns

(see the next subsection) and the filing ZIP code on business income tax

returns and mapping these ZIP codes to CZs (the local-area concept de-

fined in the next subsection). Then, to identify CZs in which the 2006

firms operated, I further restrict thesample tofirms with at least 10 2006em-

ployees living in each of at least five CZs and then to the firms’ employees

living in 2007 in those CZs. This procedure yields a retail chain sample of

865,954 individuals at 524 retail firms.

12

8

In other contexts, “working age” sometimes refers to the age-15–65 population. My

sample lies within ages 15 and 65 in all years 1999–2015. I refer to the sample as working

age mainly to communicate that it omits individuals beyond normal retirement age.

9

Citizenship is recorded as of December 2016. Results are very similar when not condi-

tioned on citizenship status. Conditioning on citizenship reduces the possibility that 2007

residents are employed in other countries but appear nonemployed in US tax data.

10

Many firms’ workers cannot be linked to a business income tax return; see the next

subsection.

11

Accessed data lacked firm names. I do not know which specific firms survived the

sample restrictions. These example firms and their industry codes were found on Yahoo

Finance.

12

As in other US administrative data (e.g., the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer

Household Dynamics; see Walker 2013), specific establishments of multiestablishment

firms are not directly identified in federal tax data. My process infers firms’ CZ-level oper-

ations from workers’ residential locations. The retail chain sample is smaller than the uni-

verse of retail chain workers for four main reasons: the age restriction, the de facto exclu-

sion of workers at independently owned franchises, mismatches between W-2 EIN and

business return EIN (see Sec. III.C.3 below), and removal of workers at firm headquarters.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2517

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Mass-layoffs sample.—The mass-layoffs sample comprises all individuals

in the full sample who separated from an employer during a mass-layoff

event in either 2008 or 2009, after having worked for the employer during

the prior three calendar years inclusive of the separation year. It is con-

structed as follows, closely adhering to the sampling frame of Davis and

von Wachter (2011), except that I define an employer as an EIN-CZ pair

rather than an EIN; an EIN may represent a firm or a division of a firm.

Using the universe of W-2s and linking W-2 payee (residential) ZIP codes

to CZs, I compute annual employment counts at the EIN-CZ level. For an

employer to qualify as having a mass-layoff event in year t ∈ f2008, 2009g,

the employer must satisfy the following conditions: it had at least 50 em-

ployees in t 2 1; employment contracted by between 30 and 99 percent

from t 2 1tot 1 1; employment in t 2 1 was no greater than 130 percent

of t 2 2 employment; and t 1 2 employment was less than 90 percent of

t 2 1employment.

13

The mass-layoffs sample comprises all 1,001,543 in-

dividuals in the full sample who received a W-2 with positive earnings from

a mass-layoff employer in years t 2 2 through year t but not in t 1 1.

C. Variable Definitions

I now define variables. Year always refers to calendar year. Variables are

available for 1999–2015.

1. Outcomes

Similar to usage by Davis and von Wachter (2011) and Autor et al. (2014),

employment in a given year is an indicator for whether an individual has

positive Form W-2 earnings or Form 1099-MISC independent contractor

earnings (both filed mandatorily by the employer) in the year. Employ-

ment is thus a measure of having been employed at any time during the

year. Note that this annual employment measure differs from the conven-

tional point-in-time (survey reference week) measure used by the BLS. Al-

though not all self-employment is reported on 1099-MISCs, transition of

affectedworkerstoself-employmentlikelydoesnotexplaintheresults: Cur-

rentPopulationSurvey data indicatethatchanges in state self-employment

rates since 2007 were unrelated to changes in state formal employment

rates.

Earnings in a given year represents labor income and equals the sum of

an individual’s Form W-2 earnings and Form 1099-MISC independent

13

The 99 percent threshold protects against EIN changes yielding erroneous mass-layoff

events. The last two criteria exclude temporary employment fluctuations. A firm that ini-

tially qualifies as having mass-layoff events in both 2008 and 2009 is assigned a 2008 event

only.

2518 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

contractor earnings. All dollar values are measured in 2015 dollars, ad-

justed for inflation using the headline consumer price index (CPI-U),

and are top-coded at $500,000 after inflation. DI receipt is an indicator for

whether the individual has positive SSDI income in the year as recorded

on Form 1099-SSA information returns filed mandatorily by the SSA. SSDI

is the main US disability insurance program. UI receipt is an indicator for

whether the individual has positive UI benefit income in the year as re-

corded on Form 1099-G information returns filed mandatorily by state

governments.

2. CZ and Great Recession Local Shock

Allowing for within-state variation, an individual’s CZ is defined as her res-

idential commuting zone, a local-area concept used in much recent work

(Dorn 2009; Autor et al. 2014; Chetty et al. 2014). CZs are collections of

adjacent counties, grouped by Tolbert and Sizer (1996) using commuting

patterns in the 1990 census to approximate local labor markets. I calcu-

late, based on the 2006–10 American Community Surveys, that 92.5 per-

cent of US workers live in the CZ in which they work. Urban CZs are sim-

ilar to MSAs, but whereas MSAs exclude rural areas, every spot in the

continental United States lies in exactly one of 722 CZs.

The 2007 CZ is the CZ corresponding to the payee (residential) ZIP

code that appears most frequently for the individual in 2006 among the

approximately 30 types of information returns (filed mandatorily by insti-

tutions on behalf of an individual, including W-2s).

14

Information returns

are typically issued in January of the following year, so the ZIP code on an

individual’s 2006 information return typically refers to the individual’s

location as of January 2007. The 2015 CZ is defined analogously to the

2007 CZ, except that if an individual lacks an information return in 2014,

I impute CZ using informationreturnZIPcode from the most recently pre-

ceding year in which the individual received an information return. The

2007 state denotes the state with most or all of the 2007 CZ’s population.

Each individual’s Great Recession local shock equals the percentage point

change in the individual’s 2007 CZ’s unemployment rate from 2007 to

2009. Annual CZunemploymentrates are computed by aggregating monthly

population-weighted county-level unemployment rates from the monthly

BLS LAUS series to the CZ-month level, then averaging evenly within CZ-

years across months. Measuring local shocks in unitsof the unemployment

14

Numerous activities trigger information returns, including formal and independent

contractor employment, SSA or UI benefit receipt, mortgage interest payment, business

or other capital income, retirement account distribution, education and health savings ac-

count distribution, debt forgiveness, lottery winning, and college attendance. A compari-

son to external data suggests that 98.2 percent of the US population appeared on some

income tax or information return submitted to the IRS in 2003 (Mortenson et al. 2009).

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2519

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

rate change permits Section IV.D’s comparison to the aggregate shock,

which can be measured in the same units. Great Recession local shocks

are available on the author’s website, along with data that can be used to

approximate the paper’s main result using publicly available data, as dem-

onstrated in online appendix table 1.

3. Covariates

Age is defined as of January 1 of the year, using date of birth from SSA

records housed alongside tax records. Female is an indicator for being re-

corded as female in SSA records. Following Autor et al. (2014), an indi-

vidual had high labor force attachment if she earned at least $10,382 in 2015

dollars—the compensation for 1,600 hours of work at the 2004 federal

minimum wage in 2015 dollars—in each of the four years 2003–6. An in-

dividual had no labor force attachment if she had zero earnings in any year

2003–6. All other individuals had low labor force attachment. The term

1040 filer is an indicator for whether the individual appeared as either

a primary or secondary filer on a Form 1040 tax return in tax year 2006.

Married is an indicator for whether the individual was either the primary

or secondary filer on a married-filing-jointly or married-filing-separately

1040 return in tax year 2006. Number of kids equals the number of children

(zero, one, or two or more) living with the individual as recorded on the

individual’s 2006 Form 1040 if the individual was a 1040 filer and zero oth-

erwise. Mortgage holder is an indicator for whether a Form 1098 informa-

tion return was issued on the individual’s behalf by a mortgage servicer in

2006.

15

Birth state is derived from SSA records and, for immigrants, equals

the state of naturalization.

The 2006 industry equals the four-digit NAICS industry code on the

business income tax return of an individual’s highest-paying 2006 Form

W-2, whenever a match can be made between the masked EIN on the W-2

and the masked EIN on the business income tax return. Four-digit NAICS

codes are quite narrow, distinguishing, for example, between restaurants

and bars. As displayed below in summary statistics and similar to recent

work (Mogstad, Lamadon, and Setzler 2017; Kline et al. 2018), almost half

of all W-2 earners could not be matched—likely because the employer is

a government entity (which does not file an income tax return, covering

15–20 percent of employment) or because the firm uses a different EIN

(e.g., a non-tax-filing subsidiary) to pay workers from the one that appears

on the firm’s tax return. For the construction of fixed effects, I assign in-

dividuals with a missing industry code to their own exclusive industry;

15

A mortgage servicer is required to file a Form 1098 on behalf of any individual from

whom the servicer receives at least $600 in mortgage interest on any one mortgage during

the calendar year.

2520 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

I assign non-W-2-earning contractors to their own exclusive industry; and

I assign the nonemployed to their own exclusive industry. I show below

that results are nearly unchanged when the sample is restricted to the

nonemployed and those with a valid W-2 industry, for whom the correct

industry is universally observed.

The 2006 age-earnings-industry fixed effects are interactions between age

(measured in one-year increments), 2006 industry, and 16 bins of the in-

dividual’s 2006 earnings (in 2015 dollars inflated by the CPI-U) from the

individual’s highest-paying employer.

16

The 2006 firm equals the masked

EIN on the individual’s highest-paying 2006 W-2. The 2006 age-earnings-

firm fixed effects are constructed analogously to the 2006 age-earnings-

industry fixed effects. Other controls are used only for robustness checks

and are defined when used.

D. Summary Statistics

Table 1 reports summary statistics across the three samples. Of the main

sample, 79.1 percent were employed in 2015, with mean 2015 earnings

(including zeros and top-coded at $500,000) of $47,587; 6.2 percent re-

ceived SSDI income in 2015, and 25.6 percent received UI benefit in-

come in at least one of the years 2007–14. The sample is 49.3 percent fe-

male; 62.4 percent had high labor force attachment in 2003–6. The

average 2006 age is 39.9 years. The retail chain sample is on average more

female, less attached to the labor force, and less likely to be married. The

mass-layoffs sample is on average less female, more attached to the labor

force, less likely to be married, and more likely to have worked in construc-

tion or manufacturing in 2006 than the main sample. Industry in the main

sample is observed for 51.1 percent of W-2 earners. The average Great

Recession local shock was a 2007–9 increase in the local unemployment rate

of 4.6 percentage points, with a standard deviation of 1.5 percentage points.

Each of the three samples comprises roughly one million individuals.

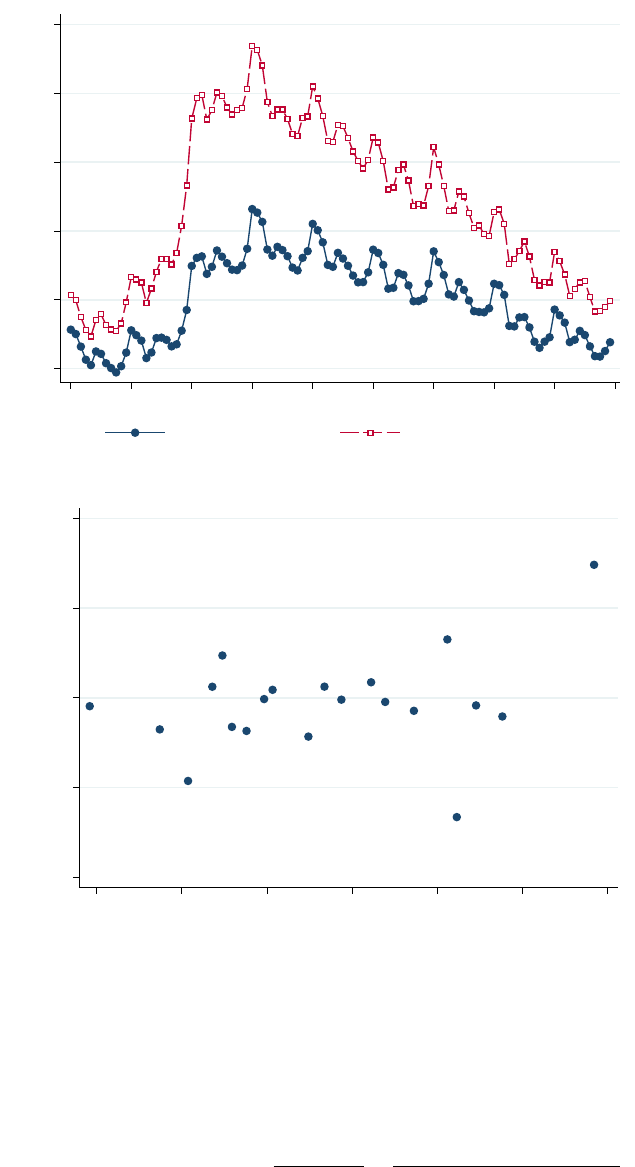

Figure 3 displays a heat map of Great Recession local shocks. Familiar

patterns are apparent, such as severe shocks in certain manufacturing ar-

eas and California’s Central Valley but not along California’s coast. Of the

variation in Great Recession local shocks, 30.0 percent is statistically ex-

plained by the house price–driven percent change in household net worth

in 2006–9 (Mian and Sufi 2009; correlation: 0.547). Recalling Section I’s

example, Phoenix—America’s sixth-largest city, shown in the medium-

dark-shaded CZ in the middle of Arizona—experienced a 77th percentile

16

The main result below is nearly identical when using Local CPI (consumer price in-

dex) 2—the more aggressive of the Moretti (2013) local price deflators—to locally deflate

2006 earnings before binning. Chosen to create roughly even-sized bins, the bin minimums

are $0, $2,000, $4,000, $6,000, $8,000, $10,000, $15,000, $20,000, $25,000, $30,000, $35,000,

$40,000, $45,000, $50,000, $75,000, and $100,000.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2521

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

TABLE 1

Summary Statistics

Main Sample Retail Chain Sample Mass-Layoffs Sample

Mean

(1)

Standard Deviation

(2)

Mean

(3)

Standard Deviation

(4)

Mean

(5)

Standard Deviation

(6)

Outcomes (in 2015):

Employed (%) 79.1 40.7 81.8 38.5 84.1 36.5

Earnings (2015 $) 47,587 63,784 33,381 44,557 48,204 62,830

UI receipt sometime 2007–14 (%) 25.6 43.6 28.3 45.0 52.2 50.0

DI receipt (%) 6.2 24.2 6.9 25.3 6.0 23.8

Personal characteristics (in 2006, 2007):

Female (%) 49.3 50.0 60.8 48.8 44.5 49.7

Age (years) 39.9 5.7 39.2 5.8 39.7 5.7

Aged 30–34 (%) 22.2 41.5 27.0 44.4 23.8 42.6

Aged 35–39 (%) 24.5 43.0 25.0 43.3 25.0 43.3

Aged 40–44 (%) 26.0 43.9 24.3 42.9 25.5 43.6

Aged 45–49 (%) 27.3 44.6 23.6 42.5 25.7 43.7

Earnings (2015 $) 45,652 55,122 33,424 36,708 52,511 55,336

No labor force attachment (%) 22.7 41.9 15.1 35.8 10.0 29.9

Low labor force attachment (%) 14.9 35.6 24.3 42.9 16.4 37.1

High labor force attachment (%) 62.4 48.4 60.6 48.9 73.6 44.1

Married (%) 62.8 48.3 52.2 50.0 52.9 49.9

0 children (%) 36.2 48.0 41.8 49.3 40.6 49.1

1 children (%) 22.6 41.8 22.9 42.0 23.4 42.3

21 children (%) 41.2 49.2 35.4 47.8 36.0 48.0

2522

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Mortgage holder (%) 38.3 48.6 25.9 43.8 38.4 48.6

Retail trade (NAICS 44,45; %) 5.2 22.3 100.0 .0 4.7 21.2

Construction/manufacturing (NAICS 23, 31–33; %) 11.9 32.4 .0 .0 17.7 38.2

Other observed industry (%) 25.9 43.8 .0 .0 34.9 47.7

Contractor (%) 4.2 20.1 .0 .0 .0 .0

Nonemployed (%) 11.5 31.9 .0 .0 .0 .0

Great Recession local shock (pp) 4.6 1.5 4.8 1.5 5.0 1.5

No. of individuals 1,357,974 865,954 1,001,543

No. of 2007 CZs 722 655 667

Note.—This table lists summary statistics for the paper’s three tax-data-based samples: the main sample (a 2 percent random sample), the retail chain

sample (all year-2006 nonheadquarters workers for identifiable retail chain firms), and the mass-layoffs sample (all workers who separated from a firm in a

2008 or 2009 mass layoff). All samples are restricted to American citizens aged 30–49 on January 1, 2007, who had not died by December 31, 2015 and who

had a continental United States ZIP code in January 2007. Earnings is the sum of W-2 wage earnings and 1099-MISC independent contractor earnings in the

calendar year, in 2015 dollars and top-coded at $500,000. “Employed” is an indicator for having positive earnings. “UI receipt sometime 2007–14” is an

indicator for having positive 1099-G unemployment insurance benefit income at some point in 2007–14. “DI receipt” is an indicator for having positive

1099-SSA disability insurance income in the calendar year. Age is measured on January 1, 2007. Labor force attachment is high if the individual had, in

every year 2003–6, earnings above 1,600 hours times the federal minimum wage, zero if the individual was nonemployed in any year 2003–6, and low oth-

erwise. “Married” is an indicator for filing a married-filing-jointly or married-filing-separately Form 1040 for tax year 2006. “Children” are dependent chil-

dren currently living with the individual as listed on the filed 1040 form. A 1040 filer is a primary or secondary filer on a 1040 form for tax year 2006. Dis-

played marriage and number-of-children statistics are restricted to 1040 filers; in regressions controlling for marriage or number-of-children fixed effects,

non-1040-filers are included as a separate group. “Mortgage holder” is an indicator for having positive mortgage payment listed on a Form 1098 in 2006

(mortgages held only in the name of a worker’s spouse or other third party are not included here). Industry categories are based on the NAICS code on the

business income tax return matched to the individual’ s highest-paying 2006 W-2 form. Nearly half of W-2 earners could not be matched, and individuals

who had only 1099-MISC independent contractor earnings are not matched; in fixed-effect regressions, unmatched 2006 W-2 earners, contractors, and the

nonemployed are assigned to three separate industries. The 2007 CZ derives from the individual’s January 2007 residential ZIP code, as reflected most

commonly on her 2006 information returns. Great Recession local shock (pp: percentage points) equals the 2009 unemployment rate in the individual’s

2007 CZ minus the 2007 unemployment rate in that CZ as reported in the BLS LAUS.

2523

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

FIG.3.— Great Recession local shocks. This map depicts unweighted octiles (divisions by increments of 12.5 percentiles) of Great Recession local

shocks across commuting zones (CZs). CZs span the entire United States and are collections of counties that share strong commuting ties. Each

CZ’s shock equals the CZ’s 2009 LAUS unemployment rate minus the CZ’s 2007 LAUS unemployment rate. In the individual-level analysis, I assign

each individual to the Great Recession local shock of the individual’s January 2007 CZ.

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

shock (6.0 percentage points), while San Antonio—America’s seventh-

largest city, shown in the large, faintly shaded, landlocked CZ in the

middle-bottom of Texas—experienced a 7th percentile shock (2.6 per-

centage points). The empirical analysis compares the 2015 outcomes of

individuals who were living in 2007 in places like Phoenix to initially sim-

ilar individuals who were living in 2007 in places like San Antonio.

IV. Overall Impacts

This section presents the paper’s main result: the estimated effect on

2015 employment of Great Recession local shocks. I begin by presenting

the main regression estimate visually and in table form, followed by ro-

bustness and extrapolation exercises.

A. Preferred Estimates

Figure 4A plots the time series of estimated effects of Great Recession lo-

cal shocks on employment. Each year t’s data point equals

^

b from the fol-

lowing version of equation (1) estimated on the main sample:

e

it

5 bSHOCK

ci2007ðÞ

1 v

gi2006ðÞ

1 e

it

, (2)

where relative employment e

it

; EMPLOYED

it

2 ð1=8Þo

2006

s51999

EMPLOYED

is

is i’s change in mean binary employment status from pre-

recession years to year t,SHOCK

c(i2007)

denotes the Great Recession shock

to i’s 2007 CZ, and v

g(i2006)

denotes 2006 age-earnings-industry fixed ef-

fects. Measuring employment outcomes relative to each individual’s pre-

recession mean transparently allows for baseline employment rate differ-

ences, similar to the relative cumulative earnings outcome of Autor et al.

(2014). The identifying assumption is that Great Recession local shocks

are as good as randomly assigned, conditional on age, initial earnings,

and initial industry. The sample and independent variable values are fixed

across figure 4A’s annual regressions; only the outcome varies from year

to year. The 95 percent confidence intervals are plotted in vertical lines

unadjusted for multiple hypotheses, based on standard errors clustered

by 2007 state.

The 2015 data point shows the paper’s main result: a 1 percentage

point higher Great Recession local shock (2007–9 spike in the CZ unem-

ployment rate) caused the average working-age American to be an esti-

mated 0.393 percentage points less likely to be employed in 2015. The

2015 impact of Great Recession local shocks is very significantly different

from zero, with a t-statistic of 4.1.

Figure 4B supports the linear specification of equation (2) by plotting

the underlying conditional expectation. It is constructed by regressing each

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2525

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

individual’sGreatRecessionlocalshock on theage-earnings-industryfixed

effects, computing residuals, adding the mean shock to the residuals, or-

dering and binning the residuals into 20 evenly sized bins, and plotting

mean 2015 relative employment within each bin versus the bin’s mean re-

sidual. The displayed nonparametric relationship between 2015 relative

employment and Great Recession local shocks is largely linear.

FIG.4.— Employment and earnings impacts of Great Recession local shocks. A, Regres-

sion estimates of the effect of Great Recession local shocks on relative employment, con-

trolling for 2006 age-earnings-industry fixed effects in the main sample. Each year t’s out-

come is year t relative employment: the individual’s year t employment (indicator for any

employment in t) minus the individual’s mean 1999–2006 employment. The 95 percent con-

fidence intervals are plotted around estimates, clustering on 2007 state. For reference, the

2015 data point (the paper’s main estimate) implies that a 1 percentage point higher Great

Recession local shock caused individuals to be 0.393 percentage points less likely to be em-

ployed in 2015. B, This graph nonparametricall y depicts the relationship underlying the main

estimate. It is produced by regressing Great Recession local shocks on 2006 age-earnings-

industry fixed effects, computing residuals, adding back the mean shock level for interpre-

tation, and plotting means of 2015 relative employment within 20 equal-sized bins of the

shock residuals. Overlaid is the best-fit line, whose slope equals 20.393. C, This graph rep-

licates A for the outcome of relative earnings: the individual’s year-t earnings minus the in-

dividual’s mean 1999–2006 earnings.

2526 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Returning to figure 4A, the prerecession time series of estimated ef-

fects constitute placebo tests supporting the identifying assumption that,

conditional on controls, Great Recession local shocks were as good as ran-

domly assigned. In particular, the 1999–2006 point estimates do not dis-

play a downwardpretrend that would suggest a negative 2015 point estimate

even in the absence of Great Recession local shocks. The graph makes

other statistics possible. For example, the 1999–2006 point estimates aver-

age zero by construction, but one could prefer to benchmark the 2015 es-

timate to a subset of prerecession estimates such as those for 1999–2001;

when subtracting the 1999–2001 mean estimate from the 2015 estimate,

one obtains the still-large effect of 20.316. When subtracting the 2004–

6 mean estimate, one obtains 20.507.

Table 2 displays coefficient estimates from equation (2) in the main

sample under various specifications. Column 4 corresponds to figure 4A’s

2015 data point, my preferred estimate. Columns 1–3 replicate the analysis

with coarser fixed effects and yield similar results, indicating relatively lit-

tle selection on the controlled dimensions among working-age Ameri-

cans. Column 5 displays ordered effect sizes by shock quintile, indicating,

for example, that living in 2007 in the most shocked quintile of CZs re-

sulted in the average individual being 1.75 percentage points less likely

to be employed in 2015 relative to living in 2007 in the least shocked quin-

tile. These effects are large, in that they are similar in magnitude to the

age-adjusted US employment rate decline 2007–15.

Full-year nonemployment indicates either long-term unemployment or

labor force nonparticipation (“exit”). Unemployment and participation

are not observed in tax data. To provide an indication of whether the non-

employment effects of Great Recession local shocks reflect labor force

exit, I test whether controlling for local unemployment persistence—

equal to the CZ’s 2015 unemployment rate minus its 2007 unemployment

rate—in the individual’s 2007 CZ (col. 6) or 2015 CZ (col. 7) attenuates

the main estimate. This test can be viewed as co nservative: controlling for

epsilon-higher unemployment persistence in relatively severely shocked

areas could fully attenuate the main estimate without that unemployment

persistence being able to explain it quantitatively. In practice, the controls

in columns 6 and 7 slightly and insignificantly attenuate the main estimate

from 20.393 to 20.366 and 20.364, respectively. This suggests that most

and possibly all of the 2015 nonemployment impact of Great Recession

local shocks took the form of labor force exit, consistent with cross-state

patterns in figure 1B.

17

17

Local unemployment rates converged throughout 2015. When only the July–

December period was used to define local unemployment persistence, the controls in

cols. 6 and 7 leave the estimate unchanged, at 20.392 and 20.393, respectively.

employment hysteresis from the great recession 2527

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

TABLE 2

2015 Impacts of Great Recession (GR) Local Shocks: Outcomes Relative to Pre-2007 Mean

N 5 1,357,974

A. 2015 Employment (pp)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

GR local shock 2.412 2.425 2.417 2.393 2.366 2.364

(.112) (.112) (.099) (.097) (.089) (.089)

Most severely shocked quintile 21.746

(.471)

Fourth shock quintile 21.144

(.434)

Third shock quintile 2.793

(.356)

Second shock quintile 2.181

(.320)

Age FEs X

Age-earnings FEs X

Age-earnings-industry FEs XXXX

Unemployment persistence in 2007 CZ X

Unemployment persistence in 2015 CZ X

R

2

.00 .00 .01 .07 .07 .07 .07

Outcome mean 27.23 27.23 27.23 27.23 27.23 27.23 27.23

Absolute outcome mean 79.1 79.1 79.1 79.1 79.1 79.1 79.1

Standard deviation of GR local shocks 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49

Interquartile range of GR local shocks 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31

2528

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

B. Additional Outcomes and Controls

Cumulative Employment

2009–15 (pp)

Earnings in

2015 ($)

Cumulative Earnings

2009–15 ($)

Employed in 2015 (pp)

(8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13)

GR local shock 22.700 2997 26,212 2.364 2.480 2.378

(.516) (168) (919) (.100) (.133) (.112)

Rust CZ GR local shock .067 2.035

(.192) (.148)

Other CZ GR local shock .094

(.250)

Age-earnings-industry FEs X X X X X X

Manufacturing share X

R

2

.07 .11 .13 .07 .07 .07

Outcome mean 240.5 6,249 27,646 27.23 27.23 27.23

Absolute outcome mean 563.9 47,587 317,011 79.1 79.1 79.1

Standard deviation of GR local shocks 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49 1.49

Interquartile range of GR local shocks 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31 2.31

Note.—All columns except col. 5 report coefficient estimates of the effect of Great Recession local shocks on postrecession outcomes in the main sample.

Column 5 divides individuals into quintiles based on their Great Recession local shocks and reports coefficients on indicators of shock quintiles, relative to the

least shocked quintile. Age fixed effects (FEs) are birth year indicators. Earnings FEs are indicators for 16 bins in the individual’ s 2006 earnings. Industry FEs

are indicators for the individual’s 2006 four-digit NAICS industry. Local unemployment persistence equals the 2015 LAUS unemployment rate minus the 2007

LAUS unemployment rate in either the individual’s 2007 CZ or the individual’s 2015 CZ. The outcome in cols. 1–7 is 2015 relative employment: the individual’s

2015 employment (indicator for any employment in 2015) minus the individual’s mean 1999– 2006 employment. The col. 8 outcome equals the sum of the

individual’s 2009–15 employment minus seven times the individual’s mean 1999–2006 employment. The col. 9 outcome equals the individual’s 2015 earnings

minus the individual’s mean 1999–2006 earnings. The col. 10 outcome equals the sum of the individual’s 2009–15 earnings minus seven times the individual’s

mean 1999–2006 earnings. Column 11 controls for the 2000 manufacturing share of employment in the individual ’s 2007 CZ, computed in County Business

Patterns. Columns 11 and 12 control for indicators (not shown) and interactions of a Rust-CZ indicator and an Other-CZ indicator, based on the individual’s

2007 CZ. A Rust CZ is a CZ with an above-median manufacturing share; an Other CZ is a CZ with a below-median manufacturing share and an above median

2006–9 change in housing net worth from Mian and Sufi (2014). The absolute outcome mean equals the outcome mean before subtraction of the prerecession

mean. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by 2007 state. For reference, col. 4 (the paper’s main specification) indicates that a 1 percentage point

higher Great Recession local shock caused individuals to be 0.393 percentage points less likely to be employed in 2015.

2529

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Figure 4C repeats figure 4A for the alternative outcome of relative

earnings: EARNINGS

it

2 ð1=8Þo

2006

s51999

EARNINGS

is

. Similar to figure 4A’s,

figure 4C’s coefficient estimates exhibit no consistent trend in the prere-

cession period and then fall persistently after the recession. Table 2, col-

umn 9, presents the graph’s 2015 data point, which indicates that living

in 2007 in a CZ that experienced a 1 percentage point higher unemploy-

ment shock caused the average working-age American to earn 997 fewer

dollars in 2015.

18

Column 10 indicates that when cumulative relative earn-

ings o

2015

t52009

½EARNINGS

it

2 ð1=8Þo

2006

s51999

EARNINGS

is

are considered, the

effect size cumulates to 2$6,212 over the 7-year period 2009–15. Multi-

plied by the interquartile range of Great Recession shocks, this last point

estimate implies an average cumulative earnings loss of $14,352, uncondi-

tional on layoff or nonemployment.

Finally, traditional analyses conceive of the Great Recession as a fluc-

tuation that interrupted a long-run trend. However, it is possible that the

mid-2000s period was a positive “masking” fluctuation(Charlesetal.2016)

around a long-run secular decline in manufacturing employment (Charles,

Hurst, and Schwartz 2018) without extremely low unemployment rates.

In that case, this section would still identify 2015 employment impacts

of the masking-ending recession, and one may then interpret 2015 em-

ployment as being in line with a premasking trend.

I test for the manufacturing-driven unmasking interpretation of this

section’s results in two ways. First, I use the Census Bureau’s County Busi-

ness Patterns (CBP) for 2000 to compute each CZ’s manufacturing share

of employment. Column 11 repeats column 4, except that it controls for

the individual’s 2007 CZ’s manufacturing share. The coefficient falls by

less than one-half of one standard error, to 20.364, and is still very statis-

tically significant.

19

Thus, the effect of Great Recession local shocks holds

within CZs with similar manufacturing shares. Second, for columns 12–

13, I use the Mian and Sufi (2014) county-level measure of the 2006–9

changeinhousing net worth to compute each CZ’s 2006–9changeinhous-

ing net worth. I then group individuals into three bins according to their

2007 CZ: CZs with an above-median manufacturing share (“Rust,” since

many are in Rust Belt states), CZs with a below-median manufacturing

share and a below-median (i.e., especially adverse) change in housing

net worth (“Sun,” since many are in Sun Belt states), and “Other” CZs.

Column 12 repeats column 4, except that it includes an interaction of the

18

Fig. 6B scales this estimate by the individual’s prerecession earnings. The earnings

analysis makes no correction for local cost-of-living changes. Measuring changes in local

living costs remains contentious, given the difficulty of measuring changes in local ameni-

ties (Moretti 2013) and a historical presumption that local amenities exactly offset appar-

ent cross-area real income differences (Rosen 1979; Roback 1982).

19

The coefficient is 20.358 when a quartic in the manufacturing share is controlled for.

2530 journal of political economy

This content downloaded from 136.152.029.121 on May 28, 2020 09:49:28 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Rust indicator and the Great Recession local-shock variable, an interaction

of the Otherindicatorandtheshock variable,andtheindicatorsseparately.

Column 13 repeats column 12, except without the Other indicator and in-

teraction. Both columns exhibit large and significant main effects of the

shock variable, indicating that the effect holds within Sun CZs and is not

driven only by Rust CZs. However, much room remains for manufacturing-

driven masking effects, including effects across industries and effects that

predated the recession or were otherwise not mediated by Great Recession

unemployment shocks.

B. Basic Robustness

Table 3 presents several robustness checks. Column 1 replicates the main

estimate, from table 2, column 4. Columns 2–5 control, respectively, for

individual-level characteristics that could independently determine labor

supply: gender, 2006 number of children, 2006 marital status, and 2006

home ownership fixed effects. In case residents of large or growing CZs

had different employment trajectories, column 6 controls for the individ-

ual’s 2007 CZ size, equal to the CZ’s total employment in 2006 as reported

in the CBP, while column 7 controls for the individual’s 2007 CZ’s size

growth, equal to the CZ’s log change in CBP employment from 2000 to

2006. Column 8 controls for the individual’s 2007 CZ’ s share of workers

who work outside the CZ, computed from the 2006– 10 American Com-

munity Surveys and motivated by recent work suggesting that commuting

options can attenuate local-shock incidence (Monte, Redding, and Rossi-

Hansberg 2015). As an early check of a policy mechanism, column 9 con-

trols for the individual’s 2007 state’s maximum UI duration over years

2007–15, derived from Mueller, Rothstein, and von Wachter (2015). Col-

umn 10 similarly controls for the individual’s 2007 state’s minimum wage

change 2007–15, using data provided by Vaghul and Zipperer (2016) and

used in Clemens and Wither (2014). The number of children, marriage,