BUILDING AMERICA’S WORKFORCE

Extending Unemployment Insurance

Benefits in Recessions

Lessons from the Great Recession

William J. Congdon and Wayne Vroman

February 2021

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 public health crisis have been swift and

severe for American workers, with the unemployment rate rising to 14.7 percent in

April 2020.

1

Among the principal policy instruments supporting workers through this

crisis is the federal-state Unemployment Insurance (UI) system, which provides cash

benefits to those who lose their jobs or, in some cases, lose work hours. As in past

recessions, policymakers have responded to deteriorating economic conditions by

expanding UI in different ways, such as covering new workers, increasing the amount

that benefits pay, and extending the length of time that workers can claim benefits.

The experience and performance of UI in past recessions with similar responses hold potential

lessons for the UI system in responding to both the current context and future recessions. In this brief,

we identify key themes from the literature on UI’s performance in the Great Recession that offer lessons

for extending benefits.

2

We draw on findings related to the performance of both the standing Extended

Benefits (EB) and temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) programs in the Great

Recession. These themes hold potentially useful lessons as extensions such as the current Pandemic

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program are implemented, as EB is triggered “on” in

many states, and as policymakers consider potential future extensions both to PEUC and other

emergency measures, as well as extensions or changes to the Federal Pandemic Unemployment

Compensation (FPUC) benefit.

We begin with a brief review of the unemployment context in the Great Recession and then review

research and evidence related to benefit extensions. From our review of that research, we generally

conclude that UI benefit extensions were central to the UI program’s effectiveness in meeting the

2

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

needs of both workers and the economy, but also posed program administration challenges. In

addition, we identify the following themes:

Benefit extensions played an important role in supporting workers and households in the Great

Recession.

UI benefit extensions played an important role in the overall macroeconomic stabilization

effects of UI spending in the Great Recession.

Research finds that benefit extensions in the Great Recession encouraged workers to remain in

the labor force and had only small effects on overall unemployment.

The Extended Benefits (EB) program, which automatically extends benefits in recessions,

required a set of ad hoc adjustments to perform effectively in the Great Recession.

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC), enacted in the Great Recession, created

challenges because of the program’s complexity and because it was not automatic.

In addition, we briefly discuss two features of the broader labor market and policy landscape that

have been noted in the literature and which relate to UI benefit extensions:

Average unemployment durations not only rose starkly in the Great Recession itself, but also

have exhibited a secular rise over many years both before and since Great Recession.

Since the Great Recession, a number of states have reduced of the maximum number of weeks

for regular UI benefits.

Unemployment in the Great Recession

The Great Recession, beginning in December 2007 and continuing through June 2009, was the most

serious economic downturn the US economy experienced to that point in more than three decades.

3

At

the depth of this recession, annual unemployment more than doubled from its prerecession level, from 7

million in 2007 to 14.8 million in 2010.

4

This recession’s effects on labor markets also persisted well into

the official recovery; the unemployment rate peaked at 10.0 percent in October of 2009, remained

above 8 percent through 2012, and did not fully return to its prerecession level until 2016.

5

Notably,

the Great Recession’s employment effects were not only deep but also prolonged, leading to unusually

long unemployment spells. At its peak in April 2010, nearly half of all unemployed workers—45.5

percent—were long-term unemployed, that is, unemployed for 27 weeks or longer.

6

Benefit Extensions in the Great Recession

The UI system responded by providing benefit extensions and implementing newly enacted emergency

benefits. This allowed workers to claim UI benefits for extended periods of time (longer than the then-

typical 26-week maximum duration of benefits). The extensions were provided under two separate

programs: Extended Benefits (EB) and Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC).

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

3

Extended Benefits

All states have federal-state EB programs, which provide additional weeks of UI benefits for workers

when the rate of unemployment in their state reaches or crosses a specified threshold. The EB program

traditionally has had a shared financial responsibility, half financed by the federal government and half

by the states. By default, EB is triggered “on” when the insured unemployment rate (IUR), an

unemployment measure based on UI claims data, in a state is at or above 5 percent and also at or above

120 percent of the average IUR in the same 13-week period in either of the prior two years, although

states may adopt alternative triggers.

7

The maximum duration of EB depends on the maximum duration

of regular UI benefits in the state and the trigger used by the state. In the Great Recession, the

maximum potential EB duration was 13 weeks in states using an IUR trigger and 20 weeks in states with

the optional TUR trigger (described below). Whittaker and Isaacs (2016) provide a recent review of EB

program details.

In the Great Recession, many states paid EB at some point—42 of the 53 UI programs triggered EB

on between 2008 and 2012 (Nicholson, Needels, and Hock 2014). Between 2008 and 2013, the EB

program provided $29.5 billion in benefit payments (Hock et al. 2016). The EB program operated

somewhat differently than usual in this period, however, principally because of two provisions in the

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) (Whittaker and Isaacs 2016).

8

First, under

ARRA the federal government assumed full financial responsibility for EB in most instances (through

2013). Second, this funding encouraged states to temporarily adopt an optional total unemployment

rate (TUR) trigger to activate the EB program. The TUR is a survey measure of state unemployment

based on the monthly labor force survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The TUR trigger is

activated when a state’s TUR is at or above 6.5 percent and also at or above 110 percent of its level in

the same three-month period in either of the prior two years. The TUR threshold is generally easier to

meet than the IUR trigger (Mastri et al. 2016). In addition to the 12 states that had a TUR trigger before

the ARRA, 26 states and the District of Columbia adopted a TUR trigger in response to the ARRA

(Mastri et al. 2016).

An additional difference for EB during the Great Recession was that the Tax Relief, Unemployment

Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 allowed states to look back three years, rather

than two, in determining whether to trigger EB on (Whittaker and Isaacs 2016).

9

This change was in

recognition of the fact that, during the Great Recession with unemployment high for a sustained period

of time but no longer rising, the lookback element of the IUR and TUR triggers might trigger states off of

EB, even with quite elevated levels of unemployment (Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie 2013). This

change expired in 2013.

Emergency Unemployment Compensation

In part because of some difficulties associated with the EB program, in times of recession the federal

government often provides a separate, temporary extension of unemployment benefits. In the Great

Recession, this took the form of the EUC program (Nicholson and Needels 2011). Initially established

with the Emergency Unemployment Compensation Act of 2008 (extended by subsequent legislation),

4

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

the EUC was fully federally financed. It usually paid benefits directly after people had fully exhausted

their eligibility for regular UI benefits.

10

Over the course of the Great Recession, the EUC program was extended for a temporary period in

11 separate pieces of federal legislation.

11

The extensions were prompted by persistently high

unemployment, which declined slowly from 2010 to 2013, while the EUC program was active. The EUC

maximum potential benefit duration was tied to state TURs, with higher TURs authorizing longer

durations. The EUC maximum was 53 weeks for much of 2010, 2011, and 2012.

12

Overall, the EUC

program provided large amounts of cash benefits to the unemployed. In 2010 and 2011, EUC payments

exceeded regular UI payments (Wandner and Eberts 2014).

13

Cumulative benefits through 2013, when

the program ended, totaled $230 billion (Hock et al. 2016).

Lessons from the Great Recession

Research finds that UI benefit extensions were central to the program’s effectiveness in meeting the

needs of both workers and the economy but also posed program administration challenges. The

empirical literature examining benefit extensions’ effects in the Great Recession generally finds they

had modest effects on work search behavior and suggests they may have moderated the rate of labor

force exit among the long-term unemployed. Research on the administration of these extensions notes

challenges they posed to state UI programs and to serving the overall UI system’s objectives.

Importance of Extensions for Households

Benefit extensions in the Great Recession were substantial in magnitude and duration. Combined, EB

and EUC paid more than $250 billion while active, providing major support for unemployed workers

during the Great Recession (Hock et al. 2016). In 2010 and 2011, benefits under these programs

accounted for the majority of unemployment benefits going to workers (Wandner and Eberts 2014). As

a result, these benefit extensions in the Great Recession provided a substantial component of the

general liquidity and consumption smoothing benefits that UI provides for workers and households

(Gruber 1997; Lee, Needels, and Nicholson 2017).

Several recent studies have suggested the importance of extended UI benefits for workers in the

Great Recession more directly by looking at outcomes for workers who exhausted even extended

benefits. Rothstein and Valletta (2017), for example, using data from Survey of Income and Program

Participation, find that the eventual exhaustion of benefits substantially reduced household income, and

these effects were more pronounced for low-income and single-parent households. They also find that

while households were more likely to participate in safety net programs, such as the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), after benefit exhaustion, these programs replaced only a fraction

of the income provided by UI benefits. As a result of the net decline in income, the poverty rate for these

families rose by 13 percentage points upon exhaustion of UI benefits.

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

5

Needels et al. (2016) examined the experiences of workers who exhausted their unemployment

benefits under the extended benefit programs, using combined survey and administrative data. They

find that employment and labor force participation for workers who exhausted benefits were lower four

to six years later compared with workers who did not exhaust their benefits. They also find those who

exhausted benefits experienced larger income losses, were more likely to live in poverty and more likely

to receive benefits from safety net programs such as SNAP than those who did not exhaust benefits.

Other recent research has illuminated how UI, by insuring individuals against precipitous declines in

income, forestalls other negative economic outcomes for households and families. Hsu, Matsa, and

Melzer (2018), for example, estimate that by supporting the income of unemployed homeowners, and

helping them to stay current on their mortgage payments, the UI extensions in the Great Recession

prevented roughly 1.3 million foreclosures between 2008 and 2013.

Macroeconomic Stabilization from Extensions

As the benefit extensions were a significant component of overall UI spending in the Great Recession,

they played an important role in macroeconomic stabilization effects of UI spending. Vroman (2010)

estimates that, inclusive of extended UI benefits, UI overall closed about two-fifths of the real GDP

shortfall caused by the recession. Of that total, he estimates the extended benefit programs

represented just under half of the overall stimulative effect of UI.

The relative importance of the extensions in the Great Recession was likely because of not only

their magnitude and duration, but also several details of their implementation. First, the EUC program

was implemented earlier in the recession than temporary extensions in previous recessions (Nicholson

and Needels 2011). Second, the federal funding of EB, along with adjustments to the EB triggers, led the

EB program to play a stronger role in the Great Recession than it had in the past several recessions

(Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie 2013).

In addition to helping stabilize the overall macroeconomy, the extensions may have helped promote

the relative efficiency of the overall labor market. As Rothstein (2011) and Farber, Rothstein, and

Valletta (2015) show, extended UI benefits in the Great Recession may have helped promote labor

force attachment among recipients. The theoretical literature also acknowledges that benefit

extensions might lead to improved matches and wages, although the empirical literature on this point

remains relatively limited, with ambiguous findings and little direct evidence from the context of either

the Great Recession or prior recessions (Nekoei and Weber 2015).

Response of Workers to Extensions

One concern raised by UI benefit extensions is the possibility that extending benefits may cause

claimants to remain out of work for longer than they otherwise would. The framework economists use

to understand and evaluate these effects is one in which the benefits of UI are weighed against the

“moral hazard” it might generate—that is, the disincentive to take a job that benefits may create (Baily

1978; Chetty 2008). In general, although an older economics literature tended to find more substantial

6

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

evidence of moral hazard from UI (e.g., Meyer 1990), more recent research tends to find these effects

are rather modest (e.g., Card, Chetty, and Weber 2007). Moreover, this framework recognizes these

effects could vary over the business cycle; that moral hazard may be less of an issue in recessions—when

jobs are comparatively scarce and needs are comparatively large (Schmieder, von Wachter, and Bender

2012; Kroft and Notowidigdo 2011; Landais, Michaillat, and Saez 2018).

Several recent academic studies have investigated the UI extensions’ effects on employment in the

Great Recession. Rothstein (2011) uses a set of identification strategies, including exploiting variation in

the EUC and EB programs, and data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), to estimate the effects

of UI benefit extensions during the Great Recession on employment outcomes. He finds that the

availability of extended benefits had a positive but small effect on the likelihood of eligible workers

remaining unemployed. He estimates that EUC and EB raised the unemployment rate in January 2011

by 0.1 to 0.5 percentage points (at a time when the observed unemployment rate was 9 percent).

Notably, he estimates that most of this effect is because of a reduction in the rate at which the

unemployed left the labor force rather than a reduction in the rate at which the unemployed become

employed.

Farber and Valletta (2015), also using CPS data, exploit variation in the EUC and EB extensions

across states to estimate the extensions’ effects in the Great Recession and compare their results with a

similar exercise examining the effects of the 2001 recession. The authors find the extensions led to a

small increase in unemployment durations, largely because of a reduction in individuals leaving the

labor force. They find this effect was stronger in the Great Recession than in the earlier recession.

Farber, Rothstein, and Valletta (2015) find qualitatively similar results examining the effects of the

extensions’ expiration that took place in 2012 and 2013.

Hock et al. (2016) use combined survey and administrative data from 12 states to describe the

claimants of extended benefits (EUC or EB) in 2008 and 2009 and their experiences during and

following their claims. The primary focus of the analysis was unemployment duration, reemployment,

and the linkage between benefit duration and reemployment. Although their research design does not

establish a causal relationship, their analysis finds that workers who were eligible for potentially longer

benefit durations had longer unemployment durations and fewer weeks of employment in the three

years following their initial claim. These associations may be a result of potential weeks of benefits

being greater in states that faced worse economic conditions.

Other approaches that examine UI’s effect on overall unemployment levels also find modest results.

Chodorow-Reich, Coglianese, and Karabarbounis (2019) examine state-level labor market responses to

UI extensions, identifying their estimates from differences between the real-time unemployment rates

that determined the duration of EUC benefits in the Great Recession and the revised estimates in later

data. They estimate that the effects of UI benefits extension from 26 to 99 weeks in the Great Recession

increased the unemployment rate by 0.3 percentage points or less.

14

Marinescu (2017) uses data from a

large online job board to show that although benefit extensions are associated with fewer job

applications, they do not reduce the number of vacancies, mitigating the extensions’ effects on

unemployment.

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

7

State Experiences Administering Extensions

EXTENDED BENEFITS

Administering the EB program in the Great Recession required state UI programs to make a number of

adjustments. Mastri et al. (2016) report the results of a 2012–13 survey of 51 UI programs (50 states

plus DC) that focused on adjustments made by state UI programs related to the ARRA’s UI provisions,

including state decisions to adopt the TUR. They find that most states adopting the TUR trigger (21 of

25) reported that federal funding of benefits was a primary reason for adopting. Conversely, many

states that did not adopt the TUR trigger (5 of 10) did not believe they would have triggered EB on using

the new trigger in the relevant time frame. Mastri et al. (2016) also report the results of an analysis

estimating that more than two-thirds of all EB first payments made between 2008 and 2012 resulted

from states adopting the TUR trigger following the ARRA.

This research indicates these temporary and ad hoc adjustments to EB—additional federal funding

of benefits, incentives to adopt the alternative trigger, and allowance for a longer lookback period—

made the program more difficult to implement. Many states (Mastri et al. 2016) reported that adopting

the TUR trigger posed implementation challenges. Almost all responding states reported that

reprogramming their data systems to handle the TUR posed challenges and also reported challenges

handling the increased number of claims. Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie (2013) also found in their

study that states reported challenges in communicating with claimants about these benefits.

Finally, in addition to issues that arose related to EB triggers, there are standing administrative

challenges associated with administering EB because of the imperfect alignment of eligibility standards

and work search requirements between EB claims and standard unemployment claims (Whittaker and

Isaacs 2016). Mastri et al. (2016), for example, report that about half of responding states noted the

challenges associated with documenting work search for EB payments.

EMERGENCY UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION

Administering EUC posed several administrative challenges for state UI programs, in part because of

the program’s complexity and changes made over the course of the program (Chocolaad, Vroman, and

Hobbie 2013). One aspect of the complexity arose from the fact that maximum potential duration of

benefits was linked to state TURs, leading to frequent changes in the maximum number of weeks. States

also identified challenges posed by the introduction of optional weekly benefit amount calculations in

mid-2010, which protected claimants from large declines in weekly benefits but required states to make

additional adjustments.

15

Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie (2013) found several states also reported

challenges associated with interactions between the EUC and EB programs.

A particular challenge EUC posed to states related to how the program was extended over time

(Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie 2013). At certain points, the program ended before Congress enacted

the next extension. For example, there were three breaks in EUC coverage during 2010, with the

longest being seven weeks in duration. After reaching enrollment and eligibility deadlines in EUC,

claimants typically stopped filing for benefits, meaning they had to initiate new applications for benefits

when EUC was subsequently extended. When EUC was extended, states were authorized to make

8

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

retroactive payments for the interim weeks. The states learned to advise EUC claimants to remain in

active claims status even though the program had terminated, although states indicated challenges in

communicating this to claimants.

Labor Market and Policy Context for Extensions

In addition to the body of literature on the effects of and experiences with the UI benefit extensions in

the Great Recession, research identifies two features of the broader labor market and policy landscape

that have continued to evolve since the Great Recession and relate to UI benefit extensions: changes in

the average duration of unemployment spells as well as the reduction in the maximum number of weeks

of UI benefits by a number of states.

Rising Unemployment Durations

An important feature of the labor market during and after the Great Recession with some relevance for

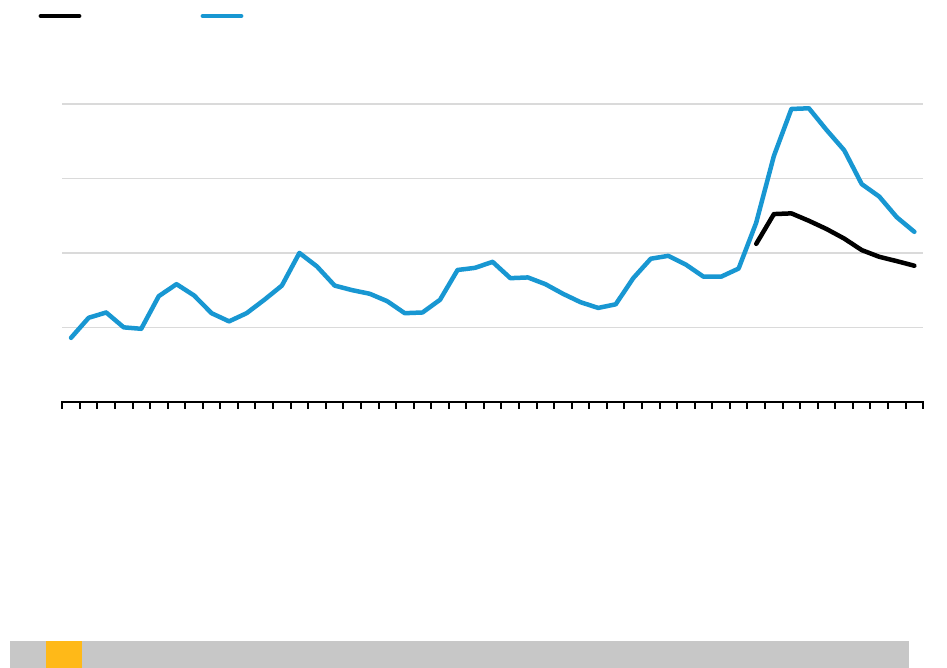

benefit extensions is the rise in average unemployment duration. Figure 1 displays the average duration

from the CPS for 1970 to 2018. Between 1970 and 2008, the mean ranged from a low of 8.6 weeks in

1970 to a high of 20.0 in 1983. During recovery from the Great Recession, however, mean duration was

much higher, even exceeding 39.0 weeks in 2011 and 2012.

FIGURE 1

Average Unemployment Duration, 1970–2018

Weeks

10

20

30

40

0

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2014 2018

Projection Average Duration

Sources: Mean annual unemployment duration from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Projected durations from estimation in

Vroman (2018).

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

9

Two features of unemployment duration over this period, both illustrated in figure 1, are notable.

First, while unemployment duration is known to increase during recessions, the increase in the Great

Recession was greater than in previous recessions. Analysis by Vroman (2018) estimates a model of

unemployment using three explanatory variables: the current year’s unemployment rate, the

unemployment rate lagged one year, and a linear trend from 1970. Although the regression provides a

good explanation of average unemployment duration between 1970 and 2008, it substantially

underestimates average duration for all 10 years between 2009 and 2018. Projected estimates from

this regression for these post-recession years are shown in figure 1. Second, there has also been a

strong upward trend in duration over the entire period shown here. The linear trend from the same

model indicates average duration has been increasing by 2.3 weeks a decade since 1970.

The longer unemployment duration of recent years, illustrated in figure 1, has implications for both

regular UI programs and extended benefit programs. It has led, for example, the exhaustion rate for

regular UI benefits to remain high even during the years of economic recovery predating the current

COVID-19 emergency. In 2017, for example, the exhaustion rate in the regular UI program was 36.4

percent—higher than in the years immediately before the Great Recession.

16

Understanding both the causes and consequences of longer unemployment durations is a topic of

active research (Valletta 2011; Valletta and Kuang 2012). One important question receiving some

recent attention in the literature and interest among policymakers, for example, is whether workers

suffering longer unemployment spells have a harder time finding work as a result (Shimer 2008). Kroft,

Lange, and Notowidigdo (2013) conducted an audit study, sending out fictitious résumés that were

otherwise identical but differed in the length of time they showed the applicant being out of work. They

found that callbacks declined with the length of time out of work, although this effect was weaker in

weaker labor markets. In a series of papers employing similar methodology, Farber and coauthors

(Farber, Silverman, and von Wachter 2016; Farber, Silverman, and von Wachter 2017; Farber, Herbst,

Silverman, and von Wachter 2019) find less conclusive evidence of such an effect.

State Reductions in Maximum Number of Weeks

An important feature of the policy landscape in the years following the Great Recession with some

relevance for benefit extensions has been the reduction in the maximum number of weeks of regular UI

benefits by some states. From the late 1970s through 2010, all state UI programs provided at least 26

weeks as the maximum potential duration in the regular program. Starting with Missouri and Arkansas

in 2011, however, some states began to lower their maximum potential durations below this level.

17

In

2019, for example, maximum potential durations were as low as 12 to 14 weeks in Alabama, Florida,

Georgia, and North Carolina. At the beginning of 2020—at the onset of the COVID-19 emergency—nine

states had a maximum potential duration of fewer than 26 weeks (three of which, in response to COVID,

returned to offering 26 weeks).

18

Reductions in maximum benefit durations affect the benefits UI provides, contributing to

reductions in recipiency rates and claims durations for unemployed workers, with direct implications for

both the need and mechanisms for implementing benefit extensions. In addition, the potential

10

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

consequences of these reductions for the countercyclical performance of UI is an important question.

As noted above, three states reversed their reduced maximums in the early stages of the COVID-19

emergency. In a few of the states with maximum durations below 26 weeks, such as Florida and North

Carolina, the maximum potential duration can rise with economic conditions, although in some cases

the triggers may be relatively insensitive to economic conditions or operate with a long lag.

Finally, reductions in state maximum durations have implications for how extended benefit

programs work (Isaacs 2018). The EB program, in particular, provides extended benefits with a

maximum duration that are a function of the state’s maximum duration of regular benefits. As a result,

states with a regular maximum duration of 26 weeks that have triggered on to EB can provide a

maximum of 13 or 20 weeks of EB payments (depending on their trigger, as described above), while

states with a maximum duration of less than 26 weeks of regular benefits can provide fewer weeks of

EB payments. For example, in August 2020, while Illinois had 20 weeks of EB (in addition to 26 weeks of

regular benefits), Florida had only 6 weeks of EB (in addition to 12 weeks of regular benefits).

19

Benefit Extensions in the COVID-19 Emergency

As noted above, some extensions to UI benefits have been implemented or triggered in the context of

the COVID-19 emergency, and further extensions are currently being considered. Some of the lessons

from the experience of the UI system with benefit extensions in the Great Recession might inform some

elements of benefit extensions in the current context:

The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program, created under the

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, provides workers with additional

weeks (originally 13 weeks, later extended to 24 weeks) of federally funded benefits.

20

At the

time of writing, claims are eligible for payment under PEUC through March 14, 2021.

Structurally, this program resembles the EUC program from the Great Recession, and some

lessons learned from EUC may be relevant. In particular, as policymakers consider whether

circumstances may warrant further benefit extensions under this program, building in triggers

that automatically extend the program based on economic conditions could avoid some of the

challenges and uncertainty created by the ad hoc extensions and resulting interruptions

experienced under the EUC program in the Great Recession, better serving state UI agencies,

workers, and the economy.

The EB program triggered on for nearly all states in the early stages of the COVID-19

emergency (in August 2020, for example, every state but South Dakota was triggered on).

21

The

experience of the EB program in the Great Recession potentially holds direct lessons for

ensuring the responsiveness of the program now. Taken together, the ad hoc adjustments to

the EB program in the Great Recession—additional federal funding of benefits, incentives to

adopt the alternative trigger, and allowance for a longer lookback period—reflect and identify

limitations of the EB program as it is currently structured. Evidence suggests that without these

temporary adjustments, EB would have been less responsive and less effective in the Great

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

11

Recession. Absent reforms to EB mirroring the adjustments made in the Great Recession, it may

either fail to perform as effectively or again require temporary patches. These limitations are

potentially magnified in states that have reduced their maximum duration of regular benefits,

which also reduces the duration of their EB programs.

Finally, policymakers are also currently considering the issue of extensions to the duration of

other elements of the UI system in the context of the COVID-19 emergency. For example, the

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) benefit, also originated under the

CARES Act, provided federally funded additions of $600 to weekly benefit amounts that

expired on July 31, 2020; the program was revived at the end of 2020, at the lower amount of

$300, and set to expire March 14, 2021.

22

Further extensions or modifications of this program

remain a subject of some policy debate as of the time of writing. Lessons from the Great

Recession on the both the substantial role that extended benefits played for households and

the broader economy, along with the evidence of their positive effects on labor force

attachment and small effects on unemployment, can inform those considerations.

Notes

1

Unemployment rate from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported tabulations: “Labor Force Statistics from the

Current Population Survey,” BLS, February 19, 2021, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

2

In a companion brief, we identify key themes from the literature on UI’s performance in the Great Recession that

offer lessons for covering more workers.

3

Recession dates from National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): “Business Cycle Dating,” NBER, accessed

August 1, 2020, https://www.nber.org/cycles.html.

4

Average annual unemployment levels from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported tabulations: “Labor Force

Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” BLS, February 19, 2021,

https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNU03000000.

5

Unemployment rate from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported tabulations: “Labor Force Statistics from the

Current Population Survey,” BLS, February 19, 2021, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

6

Percent unemployed 27 weeks or longer from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported tabulations: “Labor

Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” BLS, February 19, 2021,

https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS13025703.

7

States may also elect an optional IUR trigger of 6 percent (regardless of previous years’ levels) or an optional

TUR trigger, described below.

8

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub. L. 111-5, 123 Stat. 115 (February 17, 2009), Division B,

Title II, Subtitle A, Section 2003, https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ5/PLAW-111publ5.pdf.

9

Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, Pub. L. 112-96 (February 22, 2012), Title II,

https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ96/PLAW-112publ96.pdf.

10

Emergency Unemployment Compensation Act of 2008, Pub. L. 110-252, 122 Stat. 2323 (June 30, 2008), Title IV,

https://www.congress.gov/110/plaws/publ252/PLAW-110publ252.pdf.

11

The complicated legislative history of the EUC is illustrated in table 8.8 in Chocolaad, Vroman, and Hobbie

(2013).

12

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

12

Description of the EUC program including maximum weeks by year and claims by state and tier are provided at

“Emergency Unemployment Compensation 2008 (EUC08) and Federal-State Extended Benefit (EB) Summary

Data for State Programs,” DOL, March 29, 2004, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/euc.asp.

13

Figures from Wander and Eberts (2014), available at “Public Workforce Programs during the Great Recession,”

Monthly Labor Review, July 2014, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2014/article/public-workforce-programs-

during-the-great-recession.htm.

14

A third empirical approach, taken by Hagedorn, Manovskii, and Mitman (2016) identifies the employment effects

of UI benefit extensions by comparing outcomes between neighboring counties on either side of state lines (so

subject to different potential EUC or EB durations). The authors estimate substantial effects of the extensions on

participation and employment decisions using this approach; however, the literature suggests that this finding is

not robust. Boone, Dube, Goodman, and Kaplan (2016) show this effect is not robust to alternative specifications

and different data and find little evidence of an employment effect using this identification strategy. Dieterle,

Bartalotti, and Brummet (2020) also identify sources of bias in this method.

15

Unemployment Compensation Extension Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-205, 124 Stat. 2236 (July 2010).

16

Exhaustion rate from ETA reported summary data: “Monthly Program and Financial Data,” DOL, March 29,

2004, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claimssum.asp.

17

State maximum duration of regular benefits from recent issues of the “Comparison of State Unemployment

Insurance Laws”: “State Law Information,” DOL, March 29, 2004, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/statelaws.asp.

18

Tabulations of current state durations (and recent changes) are maintained by the Center for Budget and Policy

Priorities (CBPP): “Policy Basics: How Many Weeks of Unemployment Compensation Are Available?,” CBPP,

updated February 16, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/policy-basics-how-many-weeks-of-

unemployment-compensation-are-available.

19

As of August 18, 2020.

20

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Pub. L. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (March 27, 2020), Title II,

Subtitle A, https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ136/PLAW-116publ136.pdf. The extension to 24 weeks

at the end of 2020, along with other changes under the Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of

2020 is described in Jim Garner, “New COVID-19 Unemployment Benefits: Answering Common Questions,”

January 11, 2021, https://blog.dol.gov/2021/01/11/unemployment-benefits-answering-common-questions.

21

Trigger status for EB is reported here: “Trigger Notice No. 2020-31: State Extended Benefit (EB) Indicators

under P.L. 112-240,” August 16, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/trigger/2020/trig_081620.html.

22

For a discussion of some considerations related to extending the FPUC, see, for example, this recent CBO

publication: “Economic Effects of Additional Unemployment Benefits of $600 per Week,” CBO, June 4, 2020,

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56387. A description of the reinstated FPUC program under the Continued

Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020 is described in Jim Garner, “New COVID-19 Unemployment

Benefits: Answering Common Questions,” January 11, 2021, https://blog.dol.gov/2021/01/11/unemployment-

benefits-answering-common-questions.

References

Baily, Martin Neil. 1978. “Some Aspects of Optimal Unemployment Insurance.” Journal of public Economics 10 (3):

379–402.

Boone, Christopher, Arindrajit Dube, Lucas Goodman, and Ethan Kaplan. 2016. “Unemployment Insurance

Generosity and Aggregate Employment.” No. 10439. IZA Discussion Papers.

Card, David, Raj Chetty, and Andrea Weber. 2007. “The Spike at Benefit Exhaustion: Leaving the Unemployment

System or Starting a New Job?” American Economic Review 97 (2): 113–18.

Chetty, Raj. 2008. “Moral Hazard vs. Liquidity and Optimal Unemployment Insurance.” Journal of Political Economy

116 (2): 173–234.

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

13

Chocolaad, Yvette, Wayne Vroman, and Richard Hobbie. 2013. “Unemployment Insurance.” In The American

Recovery and Reinvestment Act: The Role of Workforce Programs, edited by Burt Barnow and Richard Hobbie,

chapter 8. Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, John Coglianese, and Loukas Karabarbounis. 2019. “The Macro Effects of

Unemployment Benefit Extensions: A Measurement Error Approach.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (1):

227–279.

Dieterle, Steven, Otávio Bartalotti, and Quentin Brummet. 2020. “Revisiting the Effects of Unemployment

Insurance Extensions on Unemployment: A Measurement-Error-Corrected Regression Discontinuity

Approach.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12 (2): 84–114.

Farber, Henry S., Jesse Rothstein, and Robert G. Valletta. 2015. "The Effect of Extended Unemployment Insurance

Benefits: Evidence from the 2012-2013 Phase-Out." American Economic Review 105:171–76.

Farber, Henry S., Dan Silverman, and Till von Wachter. 2016. “Determinants of Callbacks to Job Applications: An

Audit Study,” American Economic Review 106 (5): 314–18.

Farber, Henry S., Dan Silverman, and Till von Wachter. 2017. “Factors Determining Callbacks to Job Applications by

the Unemployed: An Audit Study." RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 3 (3): 168–201.

Farber, Henry S., Chris M. Herbst, Dan Silverman, and Till von Wachter, 2019. "Whom Do Employers Want? The

Role of Recent Employment and Unemployment Status and Age." Journal of Labor Economics 37 (2): 323–49.

Farber, Henry S., and Robert G. Valletta. 2015. “Do Extended Unemployment Benefits Lengthen Unemployment

Spells? Evidence from Recent Cycles in the U.S. Labor Market.” The Journal of Human Resources 50 (4): 873–909.

Gruber, Jonathan. 1997. “The Consumption Smoothing Benefits of Unemployment Insurance.” American Economic

Review 87 (1): 192–205.

Hagedorn, Marcus, Iourii Manovskii, and Kurt Mitman. 2016. “Interpreting Recent Quasi-Experimental Evidence on

the Effects of Unemployment Benefit Extensions.” NBER Working Paper 22280. Cambridge, MA: National

Bureau of Economic Research.

Hock, Heinrich, Walter Nicholson, Karen Needels, Joanne Lee, and Priyanka Anand. 2016. “Additional

Unemployment Compensation Benefits During the Great Recession: Recipients and their Post-Claim

Outcomes.” Washington, DC: Mathematic Policy Research.

Hsu, Joanne W., David A. Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer. 2018. “Unemployment Insurance as a Housing Market

Stabilizer.” American Economic Review 108 (1): 49–81.

Isaacs, Katelin P. 2018. “Unemployment Insurance: Consequences of Changes in State Unemployment

Compensation Laws.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Kroft, Kory, and Matthew Notowidigdo. 2016. “Should Unemployment Insurance Vary with the Local

Unemployment Rate? Theory and Evidence.” The Review of Economic Studies 83 (3): 1092–124.

Kroft, Kory, Fabian Lange, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2011. “Duration Dependence and Labor Market

Conditions: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” NBER Working Paper 17173. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau

of Economic Research.

Landais, Camille, Pascal Michaillat, and Emmanuel Saez. 2018. “A Macroeconomic Approach to Optimal

Unemployment Insurance: Applications.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10 (2): 182–216.

Marinescu, Ioana, 2017. “The General Equilibrium Impacts of Unemployment Insurance: Evidence from a Large

Online Job Board.” Journal of Public Economics 150:14–29.

Mastri, Annalisa, Wayne Vroman, Karen Needels, and Walter Nicholson. 2016. “States’ Decisions to Adopt

Unemployment Compensation Provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, Final Report.”

Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research.

Meyer, Bruce D. 1990. “Unemployment Insurance and Unemployment Spells.” Econometrica, 58(4): 757–782.

Needels, Karen, Walter Nicholson, Joanne Lee, and Heinrich Hock. 2016. “Exhaustees of Extended Unemployment

Benefits Programs: Coping with the Aftermath of the Great Recession.” Princeton, NJ: Mathematic Policy

Research.

14

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

Nekoei, Arash, and Andrea Weber. 2015. “Does Extending Unemployment Benefits Improve Job Quality?” IZA

Discussion Paper No. 9034. Bonn, Germany: IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Nicholson, Walter, and Karen Needels. 2011. “The EUC08 Program in Theoretical and Historical Perspective.”

Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research.

Nicholson, Walter, Karen Needels, and Heinrich Hock. 2014. “Unemployment Compensation During the Great

Recession: Theory and Evidence.” National Tax Journal 67 (1): 187–218.

Rothstein, Jesse. 2011. “Unemployment Insurance and Job Search in the Great Recession.” Brookings Papers on

Economic Activity. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Rothstein, Jesse, and Robert G. Valletta, 2017. “Scraping By: Income and Program Participation After the Loss of

Extended Unemployment Benefits.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36 (4): 880–908.

Schmieder, Johannes F., Till von Wachter, and Stefan Bender. 2012. “The Effects of Extended Unemployment

Insurance Over the Business Cycle: Evidence from Regression Discontinuity Estimates over 20 Years.” The

Quarterly Journal of Economics 127:701–52.

Shimer, Robert. 2008. “The Probability of Finding a Job.” American Economic Review 98 (2): 268–73.

Valletta, Robert G. 2011. “Rising Unemployment Duration in the United States: Composition or Behavior?”

Working Paper. San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Valletta, Robert G., and Katherine Kuang. 2012. “Why is Unemployment Duration So Long.” FRBSF Economic Letter

2012-3.

Vroman, Wayne. 2010. “The Role of Unemployment Insurance as an Automatic Stabilizer During a Recession.”

Washington, DC: IMPAQ International.

Vroman, Wayne. 2018. “Unemployment Insurance Benefits: Performance Since the Great Recession.” Washington,

DC: Urban Institute.

Wandner, Stephen A., and Randall W. Eberts, 2014. “Public Workforce Programs During the Great Recession.”

Monthly Labor Review. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Whittaker, Julie M., and Katelin P. Isaacs. 2016. Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits. Washington, DC:

Congressional Research Service.

About the Authors

William J. Congdon is a principal research associate in the Center on Labor, Human Services, and

Population. His research focuses on issues in labor market policy and social insurance, and his recent

work emphasizes the perspective of behavioral economics and the role of experimental methods for

understanding economic outcomes and developing public policy. He holds a PhD in economics from

Princeton University.

Wayne Vroman is an Urban Institute associate in the Center on Labor, Human Services, and Population.

He is a labor economist whose work focuses on unemployment insurance (UI) and other social

protection programs. He has directed several past projects on UI financing, benefit payments, and

program administration. He has developed simulation models to project the financing of UI in individual

states, most recently in Kentucky and Ohio. He has also worked on UI program issues in several foreign

economies. Vroman has a BA, MA, and PhD in economics from the University of Michigan.

EXTENDING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE BENEFITS IN RECESSIONS

15

Acknowledgments

This brief was prepared for the US Department of Labor (DOL), Chief Evaluation Office, by the Urban

Institute, under contract number 1605DC-18-F-00386/1605DC-18-A-0032. The views expressed are

those of the authors and should not be attributed to DOL, nor does mention of trade names, commercial

products, or organizations imply endorsement of same by the US Government. We are grateful to them

and to all our funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute,

its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and

recommendations of Urban experts. Further information on the Urban Institute’s funding principles is

available at urban.org/fundingprinciples.

The authors thank Pamela Loprest and Barbara Butrica at the Urban Institute, as well as Gay

Gilbert, Jim Garner, Robert Pavosevich, Jennifer Daley, Sande Schifferes, and Janet Javar at DOL, for

helpful comments and conversations that shaped the development of this brief. Any remaining errors

are our own.

500 L’Enfant Plaza SW

Washington, DC 20024

www.urban.org

ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE

The nonprofit Urban Institute is a leading research organization dedicated to

developing

evidence-based insights that improve people’s lives and strengthen

communities. For 50 years, Urban has been the trusted source for rigorous analysis

of complex social and economic issues; strategic advice to policymakers,

philanthropists, and practitione

rs; and new, promising ideas that expand

opportunities for all. Our work inspires effective decisions that advance fairness and

enhance the well

-being of people and places.

Copyright

© February 2021. Ur

ban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction

of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute.