Youth and the Juvenile

Justice System

2022 NATIONAL REPORT

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

i

Charles Puzzanchera, Sarah Hockenberry, and Melissa Sickmund

National Center for Juvenile Justice

December 2022

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System:

2022 National Report

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

ii

This report was prepared by the National Center for Juvenile Justice, the research division of the

National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, and was supported by cooperative agree-

ment #2019–JX–FX–K001, awarded and managed by the National Institute of Justice with funding

support provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice

Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are

those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.

Copyright 2022

National Center for Juvenile Justice

3700 S. Water Street, Suite 200

Pittsburgh, PA 15203

Suggested citation: Puzzanchera, Charles, Hockenberry, Sarah, and Sickmund, Melissa. 2022.

Youth

and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile

Justice.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

iii

Preface

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System:

2022 National Report

is the fifth edi-

tion of a comprehensive report on

youth victimization, offending by

youth, and the juvenile justice system.

With this release, the report series has

adopted a new name (the series was

previously known as “Juvenile Offend-

ers and Victims”), but the focus of the

report remains unchanged: the report

consists of the most requested infor-

mation on youth and the juvenile jus-

tice system in the United States. De-

veloped by the National Center for

Juvenile Justice (NCJJ) for the Office

of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention and the National Institute

of Justice, the report draws on reliable

data and relevant research to provide a

comprehensive and insightful view of

youth victims and offending by youth,

and what happens to youth when they

enter the juvenile justice system in the

U.S.

The report offers—to Congress, state

legislators, other state and local policy-

makers, educators, juvenile justice pro-

fessionals, and concerned citizens—

empirically based answers to frequently

asked questions about the nature of

youth victimization and offending and

the justice system’s response. The ju-

venile justice system must react to the

law-violating behaviors of youth in a

manner that not only protects the

community and holds youth account-

able but also enhances youth’s ability

to live productively and responsibly in

the community. The system must also

intervene in the lives of abused and

neglected children who lack safe and

nurturing environments.

To respond to these complex issues,

juvenile justice practitioners, policy-

makers, and the public must have ac-

cess to useful and accurate information

about the system and the youth it

serves. At times, such information is

not available or, when it does exist, it

is often too scattered or inaccessible to

be useful.

This report bridges that gap by pulling

together the most requested informa-

tion on youth and the juvenile justice

system in the United States. The re-

port draws on numerous national data

collections to address the specific in-

formation needs of those involved

with the juvenile justice system. The

report presents important and, at

times, complex information using

clear, nontechnical writing and easy-

to-understand graphics and tables. It is

structured as a series of briefing papers

on specific topics, short sections that

can be read independently from other

parts of the report.

The material in this report represents

the most reliable information on

youth and their involvement with the

justice system through the 2019 data

year. Given the range of information

covered by the report, a data-year cut-

off had to be established. We elected

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

iv

2019 as a common anchoring point

because all the major data sets required

for the report were current through

2019 at the time we began writing.

The onset of COVID-19 in 2020

caused some data collections to be sub-

stantially delayed and thus unavailable

during the writing of the report. Fur-

ther, the various coronavirus mitigation

efforts introduced across the country,

such as school closures and stay-at-

home orders, likely impacted the type

and volume of behaviors that came to

the attention of the justice system, and

simultaneously necessitated changes to

policies and practices within youth-

serving agencies. Therefore, 2019 re-

flects the experiences of youth and the

juvenile justice system unencumbered

by the impacts of the pandemic.

We expect that this report will be used

mainly as a reference document, with

readers turning to the pages on specific

topics when the need arises. However,

we encourage you to explore other sec-

tions when time permits. In each sec-

tion, you will probably discover some-

thing new, something that will expand

your understanding, confirm your

opinions, or make you question what

you believe to be true.

It has been more than 20 years since

the first edition of this report. Since

that seminal publication, this report

has become a primary source of infor-

mation on youth victimization, offend-

ing by youth, and the justice system’s

response, and it will provide a context

for debates over the direction to take

to respond to these important social

issues.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

v

Acknowledgments

This report is the result of an ongo-

ing effort that has benefited from

the assistance of many individuals.

Authors at the National Center for

Juvenile Justice (NCJJ) for various

chapters and sections include:

Q Charles Puzzanchera (chapters on

youth population characteristics,

youth victims, offending by

youth, law enforcement and

youth crime, youth in juvenile

court, and youth in corrections).

Q Sarah Hockenberry (sections on

major depressive disorders, edu-

cation, victims of serious violence,

school crime, self-reported drug

use, chapters on youth in juvenile

court and youth in corrections).

Q Melissa Sickmund (chapter on

juvenile justice system structure

and process).

In addition to authors’ contribu-

tions, the following NCJJ staff pro-

vided assistance and review: Kristy

Bach (data collection activities on bul-

lying and self-reported drug use); Mo-

riah Taylor (foster care and adoption);

and Hunter Hurst IV (upper age of

juvenile court jurisdiction and transfer

statutes). Anthony Sladky, Jason

Smith, and Greg Chamberlin provided

computer programming and data anal-

ysis support. Nancy Tierney was re-

sponsible for report production (desk-

top publishing, graphics design,

layout, copy editing, and review).

Within the National Institute of Jus-

tice (NIJ), senior advisor Benjamin

Adams and social science research ana-

lyst Kaitlyn Sill, who serve as the proj-

ect monitors under NIJ Director

Nancy La Vigne, provided careful and

thoughtful review.

Finally, this work would not be possi-

ble without the efforts of the many in-

dividuals who collect and report the

data at the local, state, and national

levels—data that are the essence of this

report.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

vii

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics 1

Youth population demographics ....................................................................... 2

Youth in poverty ............................................................................................... 7

Living arrangements of youth ......................................................................... 10

Major depressive episodes in adolescence ........................................................ 12

Births to teens ................................................................................................ 14

School dropout rates ...................................................................................... 16

Chapter 1 sources ........................................................................................... 18

Chapter 2: Youth victims 21

Child maltreatment reporting by child protective services agencies .................. 22

Child maltreatment demographics .................................................................. 25

Child maltreatment perpetrators ..................................................................... 26

Child maltreatment fatalities ........................................................................... 27

Children in foster care .................................................................................... 28

Family reunification and adoption ................................................................... 30

Victimization survey of youth ......................................................................... 31

Victims of school crime .................................................................................. 33

Victims of bullying ......................................................................................... 34

Youth victims of reported violent crimes ......................................................... 36

Youth victims of violence and those that harm them ....................................... 38

Time-of-day analyses of youth victimization .................................................... 39

Location of youth victimization ...................................................................... 41

Youth homicide victims .................................................................................. 42

Firearm-related homicides of youth ................................................................ 45

Youth suicide victims ...................................................................................... 47

Chapter 2 sources ........................................................................................... 51

Chapter 3: Offending by youth 53

Self-reports vs. official data ............................................................................. 54

School crime ................................................................................................... 55

Drug and alcohol use by school students ......................................................... 58

Drug and alcohol use trends ........................................................................... 62

Serious violent crime committed by youth ...................................................... 64

Homicides by youth ....................................................................................... 65

Time-of-day analyses of youth offending ......................................................... 70

Chapter 3 sources ........................................................................................... 75

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

viii

Chapter 4: Juvenile justice system structure and process 77

History and overview of the juvenile justice system ......................................... 78

U.S. Supreme Court cases and the juvenile justice system ............................... 83

State definitions of juvenile court jurisdiction ................................................. 87

Juvenile justice system case processing ............................................................ 88

Public access to juvenile proceedings .............................................................. 93

State provisions for trying youth as adults ....................................................... 95

State criteria for transferring youth to adult court ............................................ 97

Changes to transfer laws between 2004 and 2019 ........................................ 100

Youth in the federal justice system ................................................................ 101

Chapter 4 sources ......................................................................................... 102

Chapter 5: Law enforcement and youth 105

Introduction to youth arrest data .................................................................. 106

Gender, age, and racial variations in youth arrests ......................................... 108

Youth proportion of total arrests .................................................................. 109

Youth arrest 10-year trends ........................................................................... 110

Female youth arrest trends ............................................................................ 111

Arrest trends of youth younger than age 13 .................................................. 113

Violent crime arrest trends ............................................................................ 115

Murder arrest trends ..................................................................................... 116

Robbery arrest trends ................................................................................... 117

Aggravated assault arrest trends .....................................................................118

Property Crime Index arrest trends ............................................................... 119

Burglary arrest trends ................................................................................... 120

Larceny-theft arrest trends ............................................................................ 121

Motor vehicle theft arrest trends ................................................................... 122

Arson arrest trends ....................................................................................... 123

Simple assault arrest trends ........................................................................... 124

Weapons law violation arrest trends .............................................................. 125

Drug abuse violation arrest trends ................................................................ 126

Disorderly conduct arrest trends ................................................................... 127

Age-specific arrest rate trends ....................................................................... 128

Clearance statistics ........................................................................................ 130

Violent crime arrest rates by state .................................................................. 132

Property crime arrest rates by state ............................................................... 133

Police disposition of youth arrests ................................................................. 134

Chapter 5 sources ......................................................................................... 135

Chapter 6: Youth in juvenile court 137

Introduction to

Juvenile Court Statistics

....................................................... 138

Delinquency caseload ................................................................................... 139

Delinquency case trends ............................................................................... 140

Gender variations in delinquency cases .......................................................... 142

Offense profiles by gender ............................................................................ 144

Racial/ethnic variations in delinquency cases ................................................ 145

Age variations in delinquency cases ............................................................... 148

Detention ..................................................................................................... 150

Detention variations by demographics .......................................................... 151

Formal vs. informal case processing .............................................................. 153

Adjudication ................................................................................................. 155

Disposition ................................................................................................... 156

Delinquency case processing ......................................................................... 158

ix

Judicial waiver .............................................................................................. 161

Racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system ............................. 163

Status offense cases ....................................................................................... 168

Status offense case processing ....................................................................... 171

Youth and subsequent referrals to juvenile court ........................................... 172

Chapter 6 sources ......................................................................................... 175

Chapter 7: Youth in corrections 177

Introduction to residential placement data .................................................... 178

Youth and residential facility operation trends ............................................... 180

Facility size trends ........................................................................................ 182

Offense characteristics and youth demographics ............................................ 183

State residential placement rates .................................................................... 185

Detained and committed populations ........................................................... 186

Offense profiles of detained youth by state ................................................... 188

Offense profiles of committed youth by state ................................................ 189

Offense profiles for detained youth and committed youth ............................. 190

Gender and age variations in the residential placement population ................ 191

Racial/ethnic variations in the residential placement population ................... 192

Racial/ethnic variations in residential placement rates by state .......................193

Length of stay for youth in residential placement .......................................... 194

Residential placement facility classifications ................................................... 196

Security features in residential placement facilities ......................................... 197

Crowding in residential placement facilities ................................................... 198

Screening for educational, substance abuse, and mental health needs ............ 199

Education evaluation in residential placement facilities .................................. 200

Substance abuse evaluation in residential placement facilities ......................... 201

Mental health needs evaluation in residential placement facilities ................... 202

Suicide risk evaluation in residential placement facilities ................................ 203

Deaths reported in residential placement facilities ......................................... 204

Tribal residential placement facilities ............................................................. 206

Sexual victimization in residential placement facilities .................................... 207

Youth in adult jails ........................................................................................ 210

Youth in adult prisons ................................................................................... 211

Chapter 7 sources ......................................................................................... 212

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

1

Chapter 1

Youth population

characteristics

1

Problems experienced by children

today are the products of multiple

and sometimes complex causes. Data

presented in this chapter show that

prevalence estimates for certain risk

factors associated with delinquency

have decreased while others have been

on the rise. For example, teenage

birth rates have declined to historical-

ly low levels; however, fewer children

are being raised in two-parent fami-

lies. The proportion of youth living in

poverty has decreased since 2010, and

was at its lowest level since 1975, but

the proportion of youth experiencing

major depressive episodes has in-

creased in recent years. Although high

school dropout rates have fallen for

most demographic groups, the rates

are still too high, especially in an em-

ployment market where unskilled

labor is needed less and less.

This chapter serves to document the

status of the U.S. youth population

on several indicators of child well-be-

ing and presents an overview of some

of the more commonly requested de-

mographic, economic, and sociological

statistics on youth. These statistics per-

tain to factors that may be directly or

indirectly associated with youth crime

and victimization. Although these fac-

tors may be correlated with youth

crime and/or victimization, they may

not be the immediate cause but may

be linked to the causal factor. The sec-

tions in this chapter summarize demo-

graphic, poverty, and living arrange-

ment data developed by the U.S.

Census Bureau, depression data from

the Federal Interagency Forum on

Child and Family Statistics, birth sta-

tistics from the National Center for

Health Statistics, and education data

from the National Center for Educa-

tion Statistics.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

2

The race/ethnicity profile of the youth population will change

considerably by 2050

In 2019, about 1 in 5 residents in the United States was

younger than 18

Q Between 2020 and 2050, the number of non-Hispanic Black youth is projected to

increase 7%, the number of non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander youth is projected

to increase 44%, the number of multi-racial youth is expected to grow 77%, and

the number of youth of Hispanic ethnicity is expected to increase 28%. Conversely,

the number of non-Hispanic White youth will decrease 16%.

Q As a result of these changes, the race/ethnicity profile of U.S. youth will shift: by

2050, nonwhite youth will account for 61% of the youth population under age 18.

Note: The proportion of American Indian youth is too small to label and was 1% in each year.

Source: Author's adaptation of U.S. Census Bureau's

Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by

Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019

and

Projected

Population by Single Year of Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: July 2016 to

July 1, 2060

[machine-readable data files].

2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

54%

14%

23%

4%

50%

14%

26%

5%

47%

14%

26%

6%

43%

14%

29%

7%

39%

14%

31%

7%

8%

White Black Hispanic Amer. Indian

Asian

Multi-race

Proportion of youth population ages 0−17

5%

6%

5%

7%

After a period of decline, the

youth population is expected to

increase through 2050

For 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau es-

timated that 73,088,675 persons in the

United States—22% of the popula-

tion—were under the age of 18. The

youth population reached a low point

in 1984 at 62.5 million, increased 19%

through 2010, and then declined 1%

through 2019.

Population projections from the Cen-

sus Bureau suggest that the decline in

the population under age 18 will soon

reverse, and the youth population will

increase through the middle of the

21st century, albeit slowly. Compared

with 2020, the youth population is ex-

pected to increase 2% by 2030 and 6%

by 2050. However, as Vespa and his

colleagues note, the U.S. is a graying

country: the growth in the population

ages 65 and older will outpace all other

age groups through 2050. In fact, by

the mid-2030s, persons age 65 and older

will outnumber the population under

age 18 for the first time in history.

The race/ethnicity profile of the

youth population has changed

In response to the Office of Manage-

ment and Budget’s 1997 revisions to

the federal data collection standards on

race and ethnicity, the 2000 decennial

census adopted revised racial classifica-

tions. Prior to the 2000 census, re-

spondents were asked to classify them-

selves into a single racial group: (1)

White, (2) Black or African American,

(3) American Indian or Alaska Native,

or (4) Asian or Pacific Islander. Start-

ing with the 2000 Census, Native Ha-

waiians and Other Pacific Islanders

were separated from Asians. In addi-

tion, respondents could classify them-

selves into more than one racial group.

Information about Hispanic ethnicity is

collected separately from race.

Not all national data systems have

reached the Census Bureau’s level of

detail for racial coding—and historical

data cannot support this new coding

structure, especially the multi-race cat-

egories.* Therefore, this report gener-

ally uses the four-race coding structure.

For ease of presentation, the terms

White, Black, American Indian, and

Asian are used.

When viewed through the lens of race

and ethnicity, the youth population has

undergone a sizeable shift.

Race/ethnicity profile, youth ages 0–17:

Pct. change

Race/ethnicity 2000 2019 2000–2019

Non-Hispanic

White 62% 52% –15%

Black 15 15 –1

American Indian 11 –9

Asian 46 57

Hispanic 17 25 49

In 2019, just over half (52%) of the

youth population was classified as non-

Hispanic White, down from 62% in

2000, while the proportion classified as

*The National Center for Health Statistics

modifies the Census Bureau’s population data

to convert the detailed racial categories to the

traditional four-race categories. This bridging

is accomplished by estimating a single racial

group classification of multi-race persons

based on responses to the National Health In-

terview Survey, which asked respondents to

classify themselves using both the old and new

racial coding structures.

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

3

non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic

American Indian changed little since

2000. Conversely, the proportion of

the youth population classified as non-

Hispanic Asian and Hispanic increased

between 2000 and 2019.

In 2019, one-fourth (25%) of youth in

the U.S. were of Hispanic ethnicity, up

from 17% in 2000. Population projec-

tions from the Census Bureau suggest

that the number of Hispanic youth in

the U.S. will increase between 2020

and 2050, bringing the Hispanic pro-

portion of the youth population to

31%.

Juvenile justice systems serve

populations that vary greatly in

racial/ethnic composition

In 2019, at least 9 of every 10 youth

in Maine, Vermont, and West Virginia

were non-Hispanic and White. In con-

trast, more than half of California’s and

New Mexico’s youth populations were

Hispanic (52% and 62%, respectively).

Other states with large Hispanic youth

populations were Arizona (45%), Ne-

vada (41%), and Texas (49%).

In 2019, American Indian/Alaskan

Natives accounted for at least 10% of

the youth population in five states:

Alaska (22%), Montana (10%), New

Mexico (10%), Oklahoma (12%), and

South Dakota (14%).

The states with the greatest proportion

of Black youth in their populations in

2019 were Alabama (30%), Georgia

(35%), Louisiana (38%), Maryland

(33%), Mississippi (43%), and South

Carolina (31%). The Black proportion

of the youth population was highest in

the District of Columbia (55%).

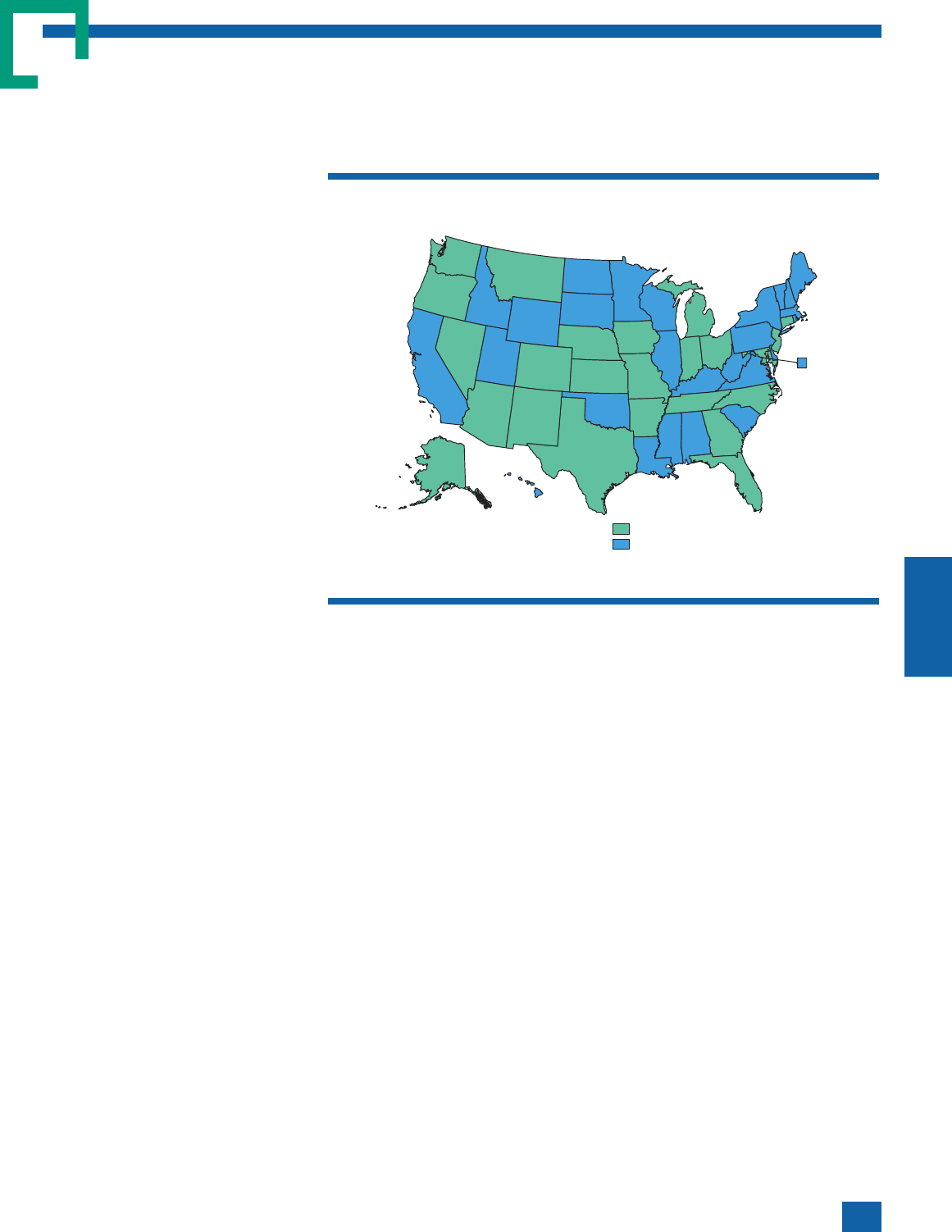

In 2019, non-Hispanic White youth accounted for less than half of

the 0–17 population in 11 states

Percent

change

2010–

2019

Racial/ethnic profile, 2019

2019

population

ages 0–17

Non-Hispanic

State White Black

American

Indian Asian Hispanic

U.S. total 73,088,700 –1% 52% 15% 1% 6% 25%

Alabama 1,088,700 –4 59 30 0 2 8

Alaska 180,400 –4 54 6 22 9 10

Arizona 1,641,700 1 40 6 5 4 45

Arkansas 701,300 –1 65 19 1 3 13

California 8,881,100 –4 28 6 1 14 52

Colorado 1,256,700 2 58 6 1 4 32

Connecticut 727,300 –11 56 13 0 6 25

Delaware 204,300 –1 50 28 0 5 17

Dist. of Columbia 128,000 26 24 55 0 3 17

Florida 4,234,000 6 44 21 0 3 31

Georgia 2,505,400 1 45 35 0 5 15

Hawaii 299,400 –1 20 3 0 57 20

Idaho 448,100 4 77 2 1 2 19

Illinois 2,817,300 –10 53 17 0 6 25

Indiana 1,569,400 –2 72 13 0 3 12

Iowa 728,000 0 78 7 0 3 11

Kansas 701,500 –4 68 8 1 3 19

Kentucky 1,004,300 –2 80 11 0 2 7

Louisiana 1,089,900 –2 52 38 1 2 7

Maine 249,600 –9 90 4 1 2 3

Maryland 1,338,200 –1 44 33 0 7 16

Massachusetts 1,353,600 –5 63 10 0 8 19

Michigan 2,144,300 –8 68 18 1 4 9

Minnesota 1,303,200 2 70 12 2 7 9

Mississippi 700,000 –7 50 43 1 1 5

Missouri 1,374,700 –3 74 15 1 3 7

Montana 228,900 2 80 2 10 1 7

Nebraska 476,000 4 70 8 1 3 18

Nevada 694,700 5 37 13 1 8 41

New Hampshire 255,800 –11 86 3 0 4 7

New Jersey 1,943,600 –6 47 14 0 11 27

New Mexico 477,200 –8 24 3 10 1 62

New York 4,031,900 –7 50 16 0 9 25

North Carolina 2,304,600 1 54 24 1 4 17

North Dakota 180,600 20 77 5 8 2 7

Ohio 2,581,400 –5 73 18 0 3 7

Oklahoma 953,900 2 57 10 12 3 18

Oregon 864,800 0 67 4 1 6 23

Pennsylvania 2,635,800 –5 68 15 0 4 13

Rhode Island 203,900 –9 59 9 1 4 27

South Carolina 1,113,700 3 56 31 0 2 10

South Dakota 217,800 7 73 4 14 2 7

Tennessee 1,511,000 1 67 21 0 2 10

Texas 7,406,800 8 33 13 0 5 49

Utah 929,900 6 76 2 1 4 18

Vermont 114,300 –11 91 3 0 3 3

Virginia 1,868,700 1 56 22 0 8 14

Washington 1,661,000 5 59 7 2 11 22

West Virginia 360,400 –7 91 5 0 1 3

Wisconsin 1,267,900 –5 71 11 1 4 13

Wyoming 133,600 –1 79 2 3 1 16

Note: Detail may not total 100% because of rounding.

Source: Authors’ analyses of Puzzanchera et al.’s.

Easy Access to Juvenile Populations

[online analysis].

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

4

Proportion of non-Hispanic Black youth in the youth population (ages 0–17), 2019

Proportion of non-Hispanic White youth in the youth population (ages 0–17), 2019

0% to 50%

50% to 75%

75% to 90%

90% or more

Percent White,

non-Hispanic

0% to 2%

2% to 10%

10% to 30%

30% or more

Percent Black,

non-Hispanic

Source: Authors’ adaptation of National Center for Health Statistics’

Vintage 2020 Postcensal Estimates of the Resident Population of the United States (April

1, 2010, July 1, 2010–July 1, 2020), by Year, County, Single-year of Age (0, 1, 2, .., 85 Years and Over), Bridged Race, Hispanic Origin, and Sex

.

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

5

Proportion of non-Hispanic Asian youth in the youth population (ages 0–17), 2019

Proportion of non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native youth in the youth population (ages 0–17), 2019

0% to 1%

1% to 2%

2% to 10%

10% or more

Percent American

Indian, non-Hispanic

0% to 1%

1% to 3%

3% to 10%

10% or more

Percent Asian,

non-Hispanic

Source: Authors’ adaptation of National Center for Health Statistics’

Vintage 2020 Postcensal Estimates of the Resident Population of the United States (April

1, 2010, July 1, 2010–July 1, 2020), by Year, County, Single-year of Age (0, 1, 2, .., 85 Years and Over), Bridged Race, Hispanic Origin, and Sex

.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

6

Proportion of Hispanic youth in the youth population (ages 0–17), 2019

Change in the juvenile population (ages 0–17), 2000–2019

0% to 5%

5% to 10%

10% to 35%

35% or more

Percent Hispanic

–10% and less

–10% to 0%

0% to 10%

10% and greater

Percent change,

2010–2019

Source: Authors’ adaptation of National Center for Health Statistics’

Vintage 2020 Postcensal Estimates of the Resident Population of the United States (April

1, 2010, July 1, 2010–July 1, 2020), by Year, County, Single-year of Age (0, 1, 2, .., 85 Years and Over), Bridged Race, Hispanic Origin, and Sex

.

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

7

The proportion of children living in poverty in 2019 was at its

lowest level since 1975

Exposure to poverty at an early

age is linked to delinquency

Research has often supported a con-

nection between poverty and involve-

ment in crime. Youth who grow up in

families or communities with limited

resources are at a higher risk of offend-

ing than those who are raised under

more privileged circumstances. Those

who are very poor or chronically poor

seem to be at an increased risk of seri-

ous delinquency. The timing of expo-

sure to poverty is especially important.

A meta-analysis by Hawkins et al. of

several studies found that family socio-

economic status at ages 6–11 is a

stronger predictor of serious and vio-

lent delinquency at ages 15–25 than

family socioeconomic status at ages

12–14. Similarly, Jarjoura, Triplett, and

Brinker found that poverty experienced

within the first five years of life signifi-

cantly increased subsequent delinquen-

cy involvement.

The linkage between poverty and de-

linquency, however, may not be direct.

Some argue that the problems associat-

ed with low socioeconomic status (e.g.,

inability to meet basic needs, low ac-

cess to support resources) are stronger

predictors of delinquency than socio-

economic status alone. For example,

Agnew et al. found that self-reported

delinquency was highest among indi-

viduals who experienced several eco-

nomic problems.

The child poverty rate has been

on the decline

The U.S. Census Bureau assigns each

person and family a poverty threshold

according to the size of the family and

ages of its members.* The national

poverty thresholds are used through-

out the U.S. and are updated for infla-

tion annually. In 2010, the poverty

threshold for a family of four with two

children was $22,113. In 2019, this

75 79 83 87 91 95 99 03 07 11 15 19

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Year

Percent in poverty

Under age 18

Ages 18−64

Age 65 and over

With the exception of multi-racial youth, the proportion of children living

in poverty in 2019 was at its lowest level since 2002 for all race/ethnicity

groups

Q More than one-third (37%) of the nearly 10.5 million youth younger than 18 living in

poverty in 2019 were Hispanic, while White youth accounted for 29% of all youth in

poverty, and Black youth accounted for 25%.

Q In 2019, the proportion of Black, American Indian, and Hispanic youth in poverty

was more than twice the proportion of White and Asian youth.

Notes: Race groups exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity can be of any

race.

Source: Author’s analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Current Population Survey (CPS) Table Creator

(for 2002-2017) and

Microdata Access, CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement

201903/202003

(for 2018-2019).

03 05 07 09 11 13 15 17 19

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Year

Percent under age 18 in poverty

Black

Hispanic

White

Asian

American Indian

Multi-race

Following a decade long decline, the proportion of children younger

than 18 living in poverty reached a new low in 2019

Q Between 2010 and 2019, the child poverty rate declined 8 percentage points while

the rate for persons ages 18–64 fell 4 percentage points. As a result, the proportion

of children living in poverty in 2019 was at its lowest level since 1975 and the pro-

portion of persons ages 18–64 in poverty reached its lowest level in two decades.

Source: Author’s adaptation of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Current Population Survey. Historical Pov-

erty Tables. Table 3: Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959–2019.

* Family members are defined as being related

by birth, marriage, or adoption.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

8

threshold was $25,926. In comparison,

the poverty threshold for a family of six

with four children was $34,161 in

2019.

Although the thresholds in some sense

reflect families’ needs, they are not in-

tended to be a complete description of

what individuals and families need to

live.

In 2019, 10% of all persons in the U.S.

lived at or below their poverty thresh-

olds. This proportion was greater for

persons under age 18 (14%) than for

those ages 18–64 (9%) and those above

age 64 (9%). The youngest children

were more likely to live in poverty than

their older peers: while 14% of children

ages 5–17 lived in households with re-

sources below established poverty

thresholds, 16% of children under age

5 did so.

Many children live far below poverty

thresholds in what is labeled as extreme

poverty. One technique for gaining a

perspective on the frequency of ex-

treme poverty is to look at the propor-

tion of children who are living below

50% of the poverty level—e.g., in

2019, how many children lived in fam-

ilies of four with two children and in-

comes less than $12,963, half the pov-

erty threshold. In 2019, 6% of persons

under age 18 were living below 50% of

the poverty level, higher than the pro-

portion of persons ages 18–64 and

persons over age 64 (4% each). This

proportion was once again highest for

children under age 5 (7%). In all, more

than 45% of children living in poverty

in 2019 lived in what can be character-

ized as extreme poverty.

In 2019, the proportion of children living in poverty ranged from a low of 3.6% in New Hampshire to a high

of 27.4% in Mississippi

Percent of persons living

below the poverty threshold, 2019

Percent of persons living

below the poverty threshold, 2019

State

All

ages

Ages

0–17

Ages

18–64

Over

age 64 State

All

ages

Ages

0–17

Ages

18–64

Over

age 64

U.S. total 10.5% 14.4% 9.4% 8.9% Missouri 9.4% 12.7% 8.0% 9.7%

Alabama 12.9 18.1 11.0 12.6 Montana 9.7 11.9 9.7 7.3

Alaska 10.2 14.2 9.7 5.0 Nebraska 8.7 15.4 6.7 5.8

Arizona 9.9 14.5 8.4 9.1 Nevada 10.4 14.4 9.2 9.3

Arkansas 14.1 18.8 12.8 12.4 New Hampshire 3.7 3.6 3.5 4.0

California 10.1 13.9 9.1 8.6 New Jersey 6.3 6.8 5.0 10.2

Colorado 9.3 11.8 9.3 5.4 New Mexico 15.3 22.0 13.7 11.9

Connecticut 8.3 10.8 7.3 8.8 New York 12.5 17.4 11.4 10.6

Delaware 6.5 10.2 6.0 4.1 North Carolina 12.7 19.9 11.3 8.4

Dist. of Columbia 12.5 14.6 11.4 15.1 North Dakota 8.1 8.7 7.9 8.2

Florida 11.5 13.3 10.8 11.6 Ohio 12.4 19.5 11.3 6.9

Georgia 12.1 15.8 10.9 10.7 Oklahoma 10.8 12.8 10.6 8.5

Hawaii 8.4 11.0 7.9 7.0 Oregon 8.1 9.9 7.6 7.7

Idaho 7.1 8.5 7.5 3.3 Pennsylvania 8.7 12.1 8.0 7.0

Illinois 9.3 12.9 8.6 6.9 Rhode Island 9.2 13.8 7.3 10.4

Indiana 10.1 14.4 8.9 8.5 South Carolina 15.1 22.1 14.2 9.7

Iowa 9.5 13.7 9.2 4.9 South Dakota 10.6 17.2 8.7 7.0

Kansas 9.5 14.4 8.2 6.7 Tennessee 13.1 19.6 11.2 11.3

Kentucky 13.6 17.1 12.0 14.5 Texas 11.1 15.0 9.5 10.7

Louisiana 17.9 26.0 15.4 15.1 Utah 7.3 8.0 7.5 4.8

Maine 10.4 13.9 10.0 8.6 Vermont 8.6 13.1 8.7 4.5

Maryland 7.0 11.1 5.6 7.0 Virginia 8.8 11.7 8.0 8.3

Massachusetts 7.5 9.6 7.4 5.7 Washington 7.0 10.0 6.5 4.5

Michigan 10.2 14.3 9.8 6.7 West Virginia 13.9 18.6 13.3 10.9

Minnesota 5.7 7.4 5.4 4.2 Wisconsin 8.4 11.3 7.3 8.2

Mississippi 19.2 27.4 18.2 10.7 Wyoming 9.2 11.9 8.7 7.5

Q Nationally, 14.4% of youth under age 18—nearly 10.5 million—were living in poverty in 2019; the proportion of children living

in poverty exceeded the national average in 17 states and the District of Columbia.

Source: Author’s adaptation of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Current Population Survey, 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement, POV46, Poverty

Status by State

.

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

9

In 2019, more than 1 in 4 Black children were living in poverty, and 1 in 8 were living in extreme poverty

(incomes less than half the poverty threshold)

Living below the poverty level Living below 50% of the poverty level

Age All White Black

Amer.

Indian Asian

Multiple

races Hispanic All White Black

Amer.

Indian Asian

Multiple

races Hispanic

All ages 10% 7% 19% 18% 7% 12% 16% 5% 3% 8% 9% 4% 6% 6%

Under age 18 14 8 27 21 8 14 21 6 4 12 11 4 8 8

Under age 5 16 9 31 25 6 20 21 7 4 14 11 3 10 9

Ages 5–17 14 8 26 20 8 12 20 6 4 11 11 4 7 7

Ages 18–64 9 7 16 16 7 11 13 4 4 7 9 4 5 5

Over age 64 9 2 19 21 10 6 16 4 3 7 9 5 2 7

Q There was little difference between the proportions of children in poverty compared with adults ages 18–64 in poverty for either White

or Asian populations in 2019. Children under age 18 in poverty and adults ages 18–64 in poverty differed by 8 percentage points in

the Hispanic population and 11 percentage points in the Black population.

Note: Racial categories (White, Black, American Indian, Asian, and multiple) do not include persons of Hispanic ethnicity. The Asian racial category in-

cludes Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders.

Source: Author’s adaptation of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Microdata Access, CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement 201903/202003

.

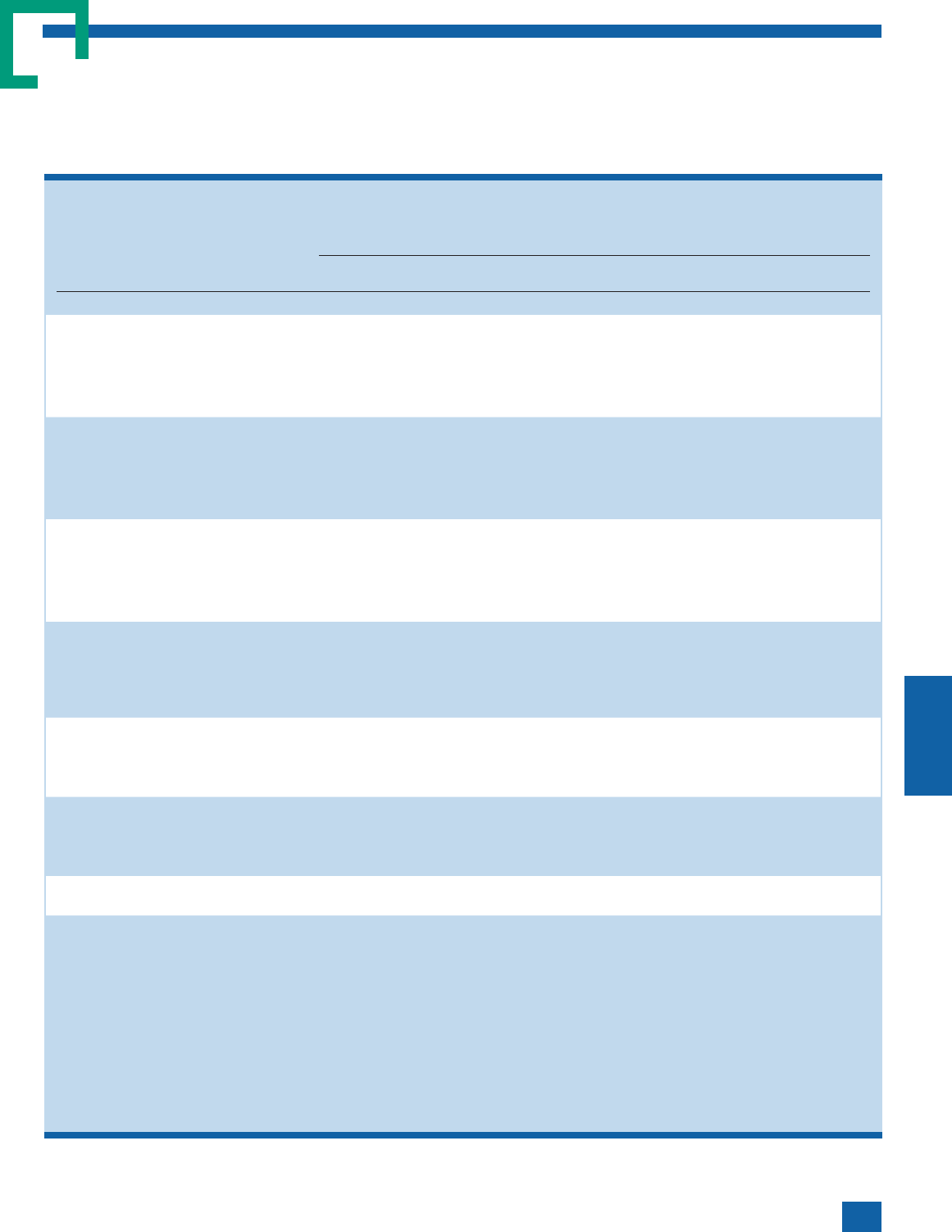

Proportion of youth (ages 0–17) living in poverty, 2019

0% to 10%

10% to 20%

20% to 30%

30% or more

Percent living

in poverty

Source: Authors analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program: 2019 Poverty and Median Household

Income Estimates - Counties, States, and National.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

10

The proportion of children living in single-parent homes more

than doubled between 1970 and 2019

Children living with two parents

generally report less delinquency

Research by Johnson, Hoffman, and

Gerstein as well as Hemovich and

Crano found that adolescents ages

12–17 living with two parents were

less likely to use alcohol, cigarettes,

and illicit drugs than their counterparts

not living in two-parent families. Like-

wise, a review by Kroese and colleagues

notes that existing research links grow-

ing up in a single-parent household

with an increased likelihood of crime

among adolescents. However, it is im-

portant to note that family structure

may not be the proximate cause of

problem behaviors. Rather, conditions

within the family, such as poor supervi-

sion and low levels of parental involve-

ment, are risk factors.

More than one-third of children

living with only their mothers were

in poverty

The economic well-being of children is

related to family structure. In 2019, 14%

of all children lived below the poverty

level. However, children living in mar-

ried couple families were less likely to

live in poverty (6%) than children liv-

ing with only their fathers (16%) or

only their mothers (36%). Family struc-

ture is also related to the proportion of

children in households receiving public

assistance or food stamps. Overall, 3%

of children in 2019 lived in households

receiving public assistance and 17%

lived in households receiving food

stamps, but the proportions were far

greater for children living in single-

mother families.

Percent of children receiving assistance,

2019:

Living

arrangement

Food

stamps

Public

assistance

All types 17% 3%

Two parents 10 1

Married 8 1

Unmarried 29 5

Single parent 35 6

Mother only 39 6

Father only 18 2

Neither parent 27 10

Q Between 1970 and 2019, the proportion of children living with their mothers in

single-parent homes increased from 8% to 17% for White children and from 30%

to 48% for Black children. For children of Hispanic ethnicity, the proportion in-

creased from 20% in 1980 to 24% in 2019.

Notes: Beginning with 2007, estimates for two-parent homes include married or unmarried parents

(biological, step, or adoptive). Persons of Hispanic ethnicity can be of any race; however, most are

White. Race proportions include persons of Hispanic ethnicity.

Source: Author’s analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Current Population Survey, Families and Living

Arrangements, Historical Tables

.

71 77 83 89 95 01 07 13 19

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Percent of youth under age 18 living with mother only

White

Black

Hispanic

Year

The proportion of children living in single-parent homes more than

doubled between 1970 and 2019

Q In 2019, 70% of children were living in two-parent families—a level that has

changed little since 2007. Most other children live in single-parent households.

Q Most children in single-parent families lived with their mothers in 2019, but a grow-

ing proportion were living with their fathers. Since 1970, the proportion of children

in single-parent homes living with their fathers grew from 1% to 4% in 2019.

Despite a recent decline, Black children were more likely than White or

Hispanic children to live with only their mother in a single-parent home

71 77 83 89 95 01 07 13 19

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Year

Percent of children (under 18) in living arrangement

Two parent

One parent

71 77 83 89 95 01 07 13 19

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Year

Percent of children (under 18) in living arrangement

Mother only

Father only

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

11

In 2019, 51% of children receiving

public assistance and 49% receiving

food stamps lived in single-mother

families. Two-parent families accounted

for 30% of children receiving public

assistance and 40% of those receiving

food stamps.

Seven in ten children lived in two-

parent families in 2019

Based on the Census Bureau’s Current

Population Survey, 85% of children

under age 18 were living in two-parent

families in 1970. The proportion de-

clined into the mid-2000s, where it fell

to 67% in 2005. By 2019, 70% of chil-

dren were living in two-parent (married

or unmarried) families. Most other

children lived in one-parent households.

The proportion of children living in

single-parent households increased

from 9% in 1960 to 25% in 2019.

Beginning with the 2007 Current Pop-

ulation Survey, more accurate data are

available to document the proportion

of children who live with married or

unmarried parents. In 2019, 4% of

children under age 18 were living with

two unmarried parents, up slightly from

3% in 2007. In 2019, 66% of children

under age 18 lived with married par-

ents. This proportion was highest for

Asian (86%) and White children (75%),

lower for Hispanic children (68%), and

lowest for Black children (42%).

Most children who live in single-parent

households live with their mothers. In

fact, this was the second most common

living arrangement of children in 2019.

The proportion of children living with

their mothers in single-parent house-

holds grew from 8% of the child popu-

lation in 1960 to 21% in 2019. In

1970, the mothers of 7% of the chil-

dren living in single-mother house-

holds had never been married; this

proportion grew to 49% in 2019.

The proportion of children living with

their fathers in one-parent households

grew from 1% in 1970 to 4% in 2019.

In 1970, the fathers of 4% of the chil-

dren living in single-father households

had never been married; this propor-

tion grew to 39% in 2019, a pattern

similar to the mother-only households.

The Census Bureau found a major dif-

ference between mother-only and fa-

ther-only households: cohabitation was

much more common in father-only

households. A living arrangement is

considered to be cohabitation when

there is an unrelated adult of the oppo-

site gender, who is not one’s spouse,

living in the household. In 2019, chil-

dren living in single-parent households

were more likely to have a cohabiting

father (28%) than a cohabiting mother

(9%).

Some children live in households head-

ed by other relatives or by nonrelatives.

In 2019, 3% of children lived in house-

holds headed by other relatives, and

about half of these children were living

in the home of a grandparent. (Across

all household types, 10% of children

lived in households that included a

grandparent.) In 2019, 1% of all chil-

dren lived with nonrelatives.

Most children live in a household

with at least one parent in the

labor force

Overall, 88% of children in 2019 lived

in families with one or both parents in

the labor force, i.e., employed or ac-

tively looking for work. Of all children

living with two parents, 97% had at

least one parent in the labor force, and

62% had both parents in the labor

force. When just one parent in two-

parent families was in the labor force,

87% of the time it was the father.

Among children living in single-parent

households, those living with fathers

only were more likely to have the par-

ent in the labor force than those living

with mothers only (87% vs. 78%).

In 2019, Asian youth were most likely to live with two parents while

Black youth were least likely

Notes: Persons of Hispanic ethnicity can be of any race; however, most are White. Race proportions

include persons of Hispanic ethnicity.

Source: Author’s analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s

Current Population Survey, 2019 Annual Social

and Economic Supplement

.

Hispanic

Asian

Black

White

non-Hispanic

White

All races

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

68% 24% 4% 4%

86% 10% 2% 2%

42% 46% 5% 7%

78% 14% 5% 3%

75% 17% 4% 3%

70% 21% 4% 4%

Percent of children (ages 0–17), 2019

Two parents, including unmarried parents

Mother only

Father only

Neither parent

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

12

In 2019, 3.8 million youth ages 12–17 reported experiencing

a major depressive episode

Major depressive episodes in

adolescence can have long lasting

effects

The Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration (SAM-

HSA) annually conducts the National

Survey on Drug Use and Health to

collect information from persons ages

12 and older in the U.S. In addition to

gathering information about substance

use behaviors, the survey also collects

information about depression; specifi-

cally, respondents are asked to report

whether they have had a major depres-

sive episode (MDE) in the 12 months

prior to the survey. According to the

American Psychiatric Association, an

MDE is defined as a period of at least

2 weeks when a person experiences a

depressed mood or loss of interest or

In 2019, 16% of youth ages 12–17 reported a major depressive

episode in the past 12 months, and 43% of these youth received

treatment

Percentage of youth (ages 12–17) reporting

occurrence in the last 12 months

Demographic

Major depressive

episode (MDE)

MDE with severe

impairment

MDE and received

treatment

Total 16% 11% 43%

Age

Ages 12–13 11 7 38

Ages 14–15 16 12 44

Ages 16–17 20 15 46

Gender

Male 9 6 37

Female 23 17 46

Race/ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic 16 11 50

Black, non-Hispanic 11 8 36

Hispanic 17 12 37

American Indian 12 12 NA

Asian 15 11 NA

Two or more races 21 15 NA

Q In 2019, youth ages 16–17, females, and multi-racial youth were more likely to

report an MDE than their counterparts.

* Treatment refers to seeing or talking to a medical doctor or other professional or using prescrip-

tion medication for depression.

NA: Data not available.

Source: Author’s adaptation of the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics’

America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-being, 2021

.

pleasure in daily activities, plus at least

4 additional symptoms of depression

(e.g., problems with sleep, eating, en-

ergy, concentration, and feelings of

self-worth).

Depression is known to have effects

not only on mental health but also on

physical health and can affect adoles-

cent development. As noted in the

2021 America’s Children: Key Nation-

al Indicators of Well-Being

report, fa-

milial and peer relationships may be-

come strained, depressive episodes

may continue into adulthood, academ-

ic performance may suffer, and youth

who reported at least one major de-

pressive episode in the prior 12 months

are more likely to begin using alcohol

or other drugs and are at greater risk

for suicide.

The likelihood of experiencing a

major depressive episode varied

by demographics

In 2019, 1 in 6 (16%) youth ages

12–17 reported having at least one

MDE in the prior 12 months. Older

youth (youth ages 16–17) and females

were more likely to report an MDE

compared with their counterparts. The

proportion of youth who reported hav-

ing an MDE was similar for White and

Hispanic youth and was higher than

the proportion for Black youth.

Approximately 1 in 10 (11%) youth

ages 12–17 reported having at least

one MDE that involved severe impair-

ment in the prior 12 months. That is,

the MDE adversely impacted the re-

spondent’s life in relation to home

management, work, close relationships

with others, and social life. Fewer than

half (43%) of youth who had at least

one MDE in the prior 12 months re-

ceived treatment. Compared with their

counterparts, youth ages 14 and older,

females, and White youth were more

likely to have received treatment.

A small proportion of youth

experienced an MDE and a

substance use disorder

According to SAMHSA, 2.7% of youth

reported having a substance abuse dis-

order (SUD) in the prior 12 months.

SUDs are characterized by impairment

caused by routine use of alcohol and/

or other drugs, that results in health

problems and failure to meet responsi-

bilities at home, work, or school.

Fewer than 2 in 100 youth (1.7%) re-

ported having both an MDE and SUD

in the prior 12 months. A similar pro-

portion of youth (1.4%) reporting an

SUD also reported having an MDE

with severe impairment. Compared

with youth who did not experience an

MDE in the prior 12 months, MDE

youth were more likely to have used il-

licit drugs, marijuana, or opioids, to

binge drink alcohol, or to smoke ciga-

rettes in the prior month.

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

13

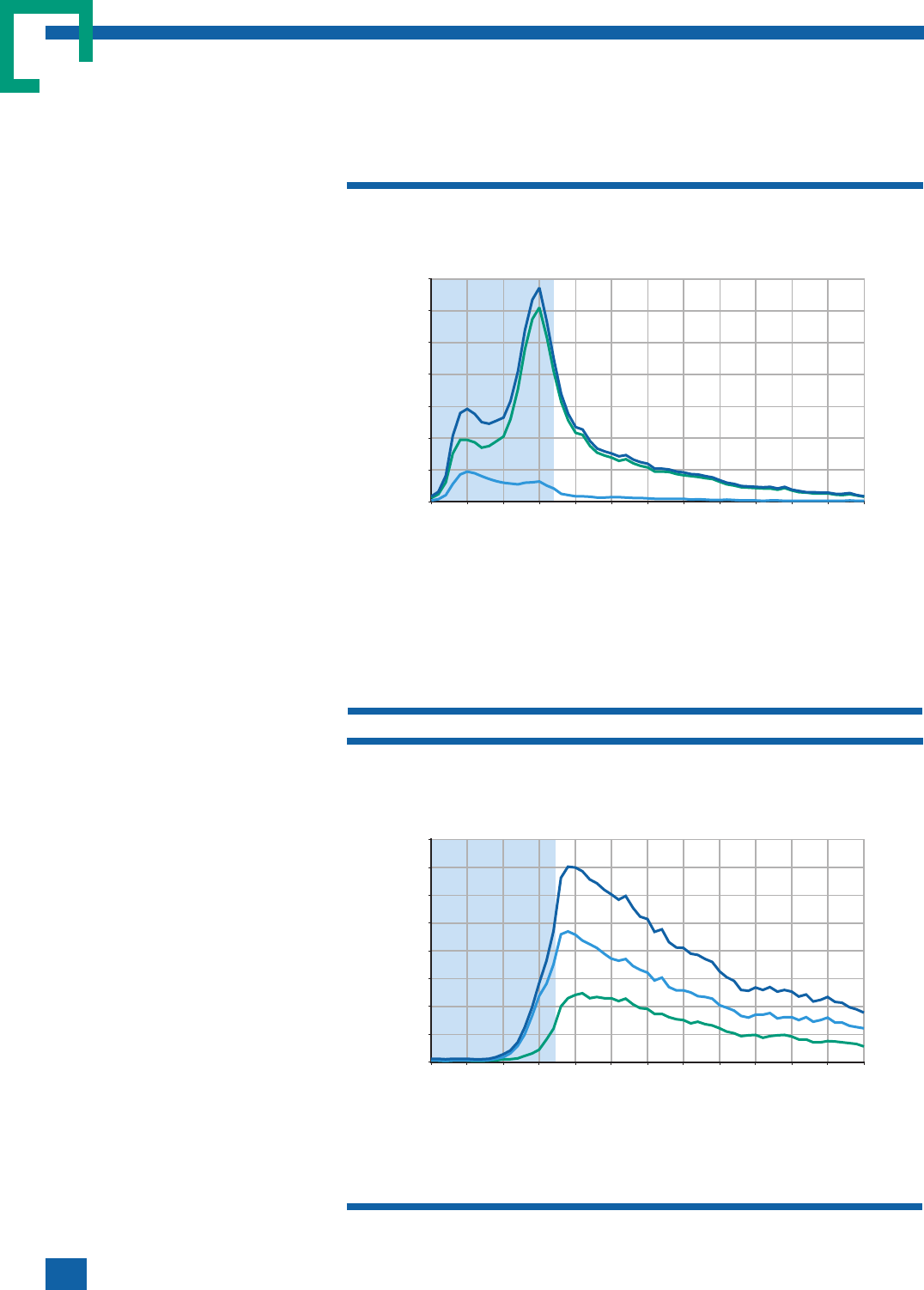

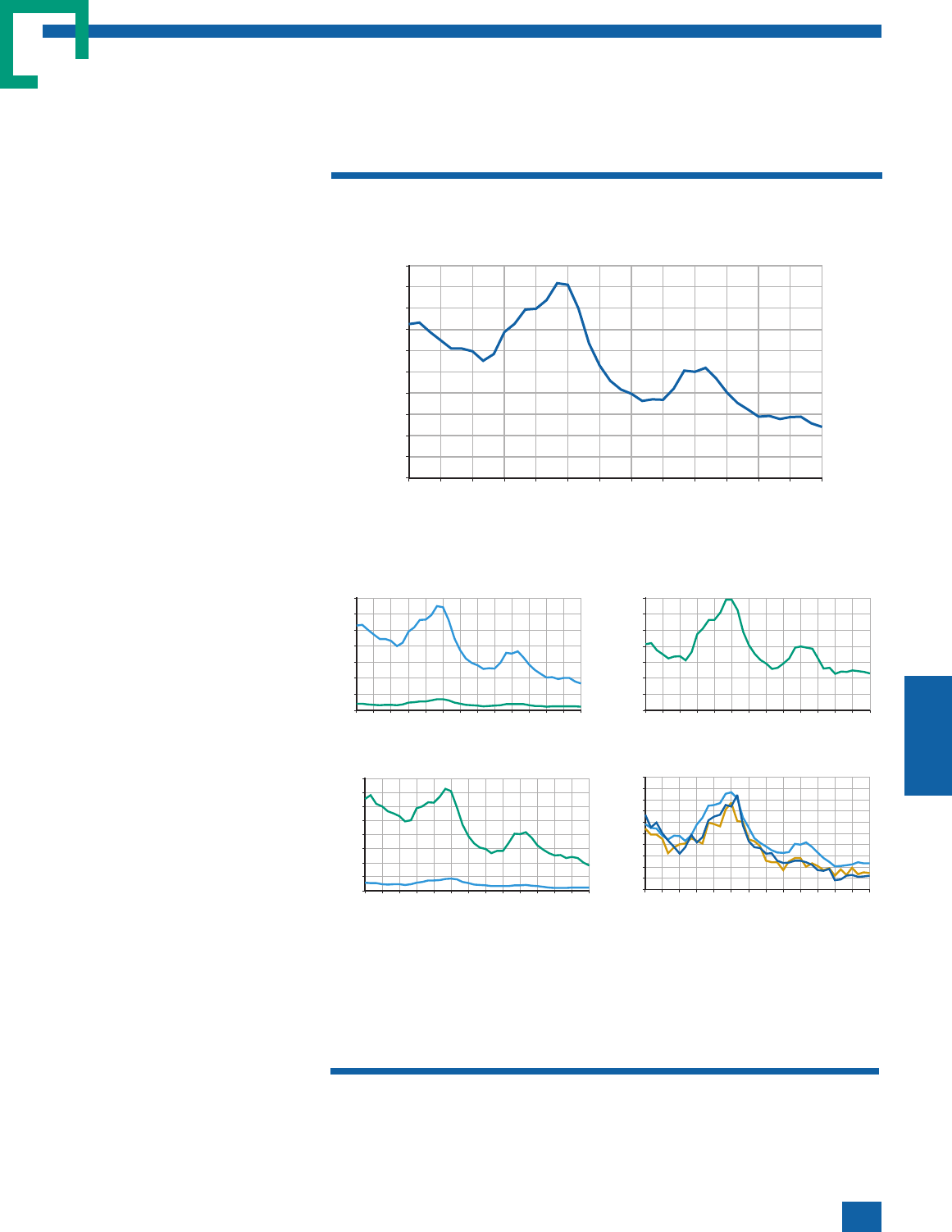

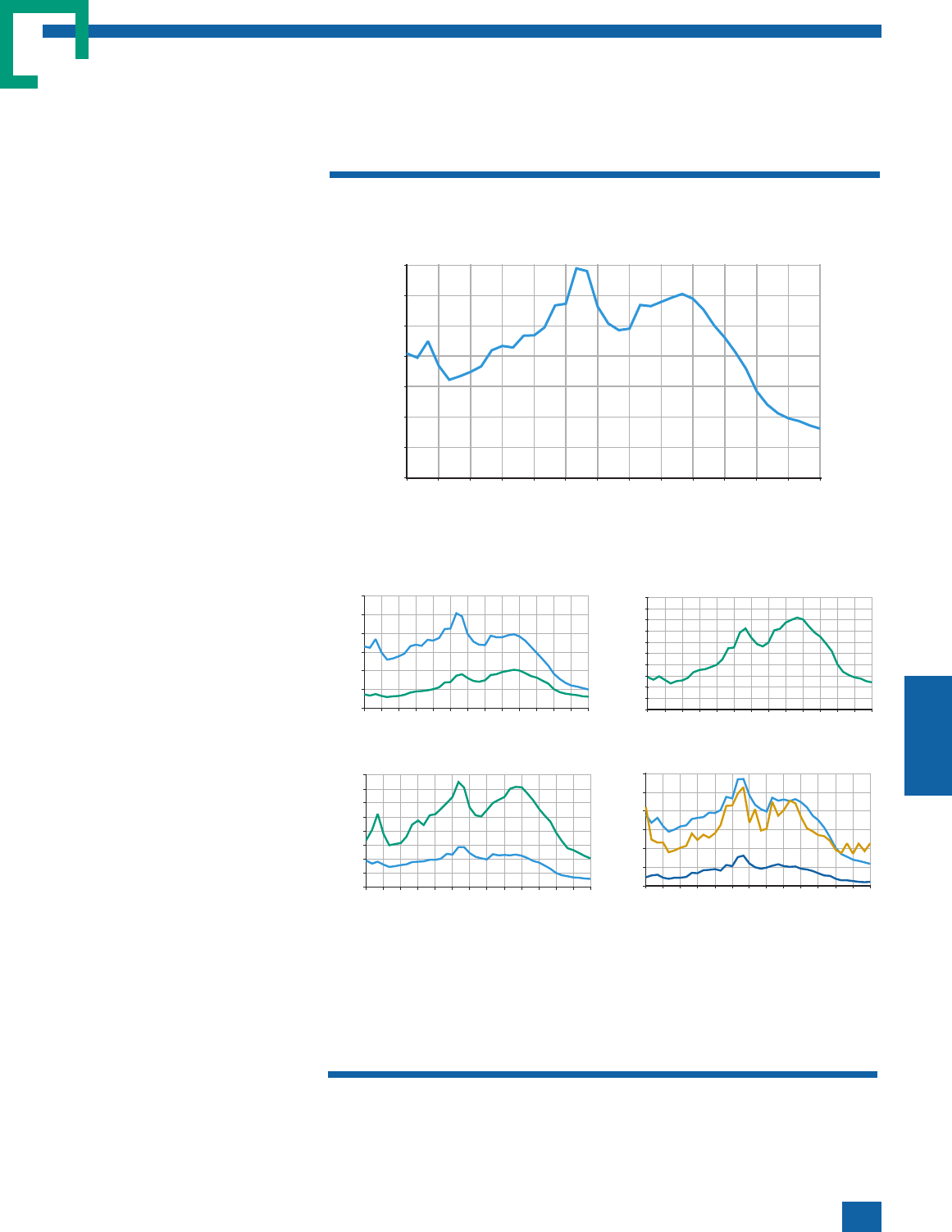

The proportion of youth ages 12–17 experiencing at least one major depressive episode has increased for all

demographic groups in recent years

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Percent of youth (ages 12−17) reporting a major depressive

episode (MDE) in the last 12 months

Female

Male

Total

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Of youth reporting MDE, percent reporting receivng

treatment in the last 12 months

Female

Male

Total

Q The proportion of youth reporting an MDE in 2019 (16%) increased 7 percentage points since 2004. Females (+10%), youth ages

16–17 (+8%), and White youth (+7%) had the largest percentage point increases between 2004 and 2019.

Q Overall, the likelihood of receiving treatment following an MDE increased 3 percentage points between 2004 and 2019, but the

level of increase varied by youth demographics.

Source: Author’s adaptation of the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics’

America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-being,

2021

.

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Percent of youth (ages 12−17) reporting a major depressive

episode (MDE) in the last 12 months

Ages 16−17

Ages 12−13

Ages 14−15

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Of youth reporting MDE, percent reporting receivng

treatment in the last 12 months

Ages 16−17

Ages 12−13

Ages 14−15

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

4%

8%

12%

16%

20%

Percent of youth (ages 12−17) reporting a major depressive

episode (MDE) in the last 12 months

Hispanic

White

Black

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Of youth reporting MDE, percent reporting receivng

treatment in the last 12 months

Black

Hispanic

White

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

14

The teenage birth rate declined considerably since the early

1990s

Teen birth rates reached a new

low point in 2019

Research suggests (see Martin et al.,

Ely and Driscoll, Hoffman and May-

nard, and Driscoll) that giving birth

during adolescence brings long-term

difficulties for the teen mother and her

child. Compared with babies born to

older mothers, babies born to adoles-

cent mothers, particularly younger ad-

olescent mothers, are at higher risk for

low birthweight and infant mortality.

In addition, giving birth during adoles-

cence is linked to limited educational

attainment for the teen mom, which

can adversely impact their employment

opportunities and future earnings, and

children born to teen moms are them-

selves less likely to complete high

school.

In 2019, the birth rate for older youth

(i.e., females ages 15–17) was 6.7 live

births for every 1,000 females in the

age group. In the same year, the birth

rate for young adults (i.e., women ages

18 and 19) was more than 4 times

greater (31.1). Conversely, the birth

rate for females ages 10–14 (0.2) was

well below the rates of older teens.

Teen birth rates have been on the de-

cline since 1991, but the decline for fe-

males ages 15–17 (83%) outpaced the

decline for young adults (67%)

through 2019. The rate for both age

groups in 2019 reached their lowest

levels since 1970. Birth rates for older

teens and young adults varied by race

and Hispanic ethnicity.

Births per 1,000 females, 2019:

Race/ethnicity

Ages

15–17

Ages

18–19

All races 6.7 31.1

White 3.8 22.3

Black 11.1 46.4

Hispanic 11.5 46.2

American Indian 13.5 51.8

Asian 0.9 5.2

Native Hawaiian/

Other Pacific Islander

7.7 53.8

Note: Race groups exclude persons of

Hispanic ethnicity. Hispanic youth can be

of any race.

The birth rate for White females ages

15–17 in 2019 was about one-third

the rates of Hispanic, Black, and Amer-

ican Indian females of the same age,

and about half the rate of Native Ha-

waiian/Other Pacific Islander females.

Across race/ethnicity groups, the birth

rate for females ages 15–17 declined

70% or more between 1991 and 2019,

and reached their lowest level since

1990.

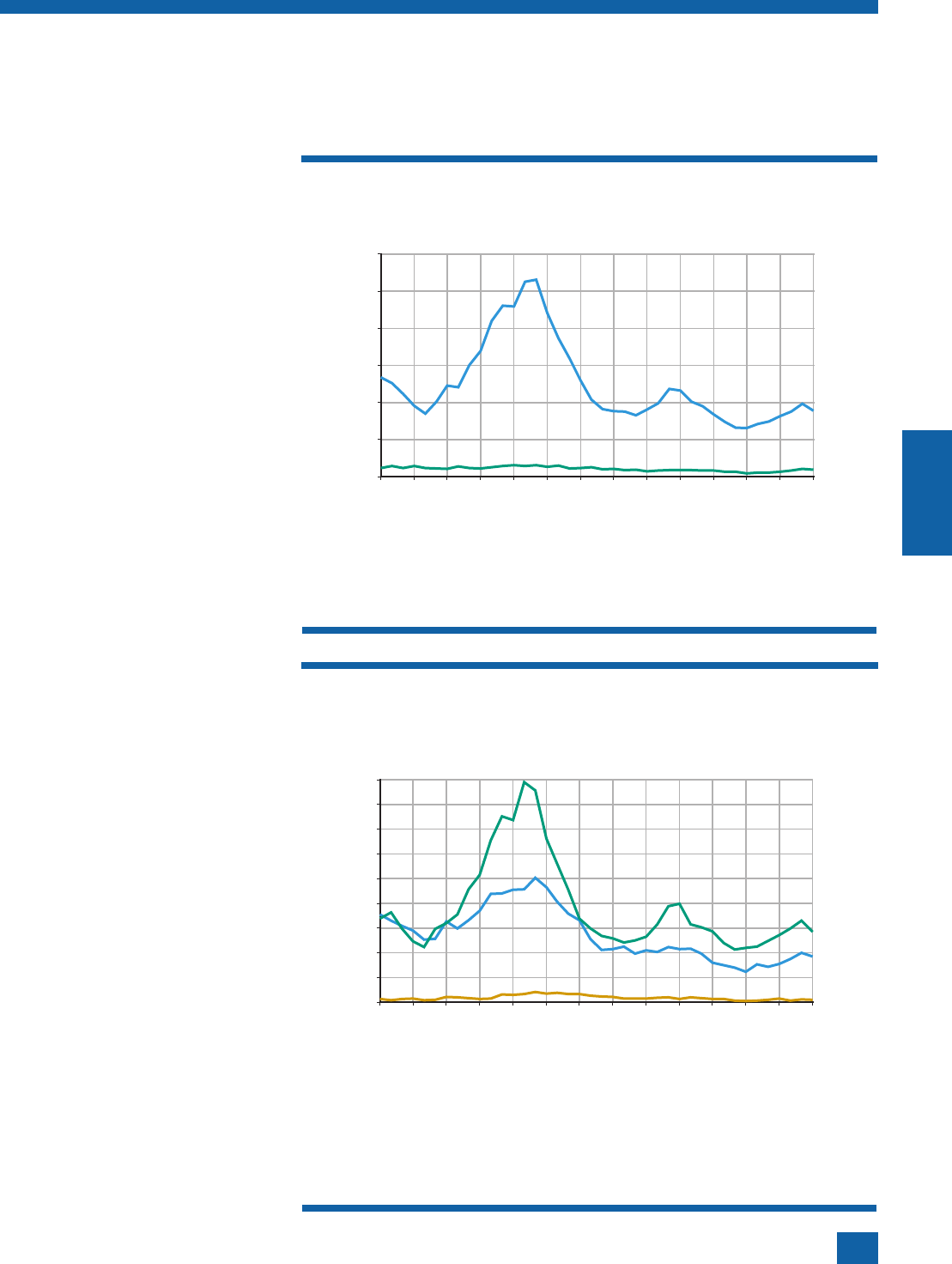

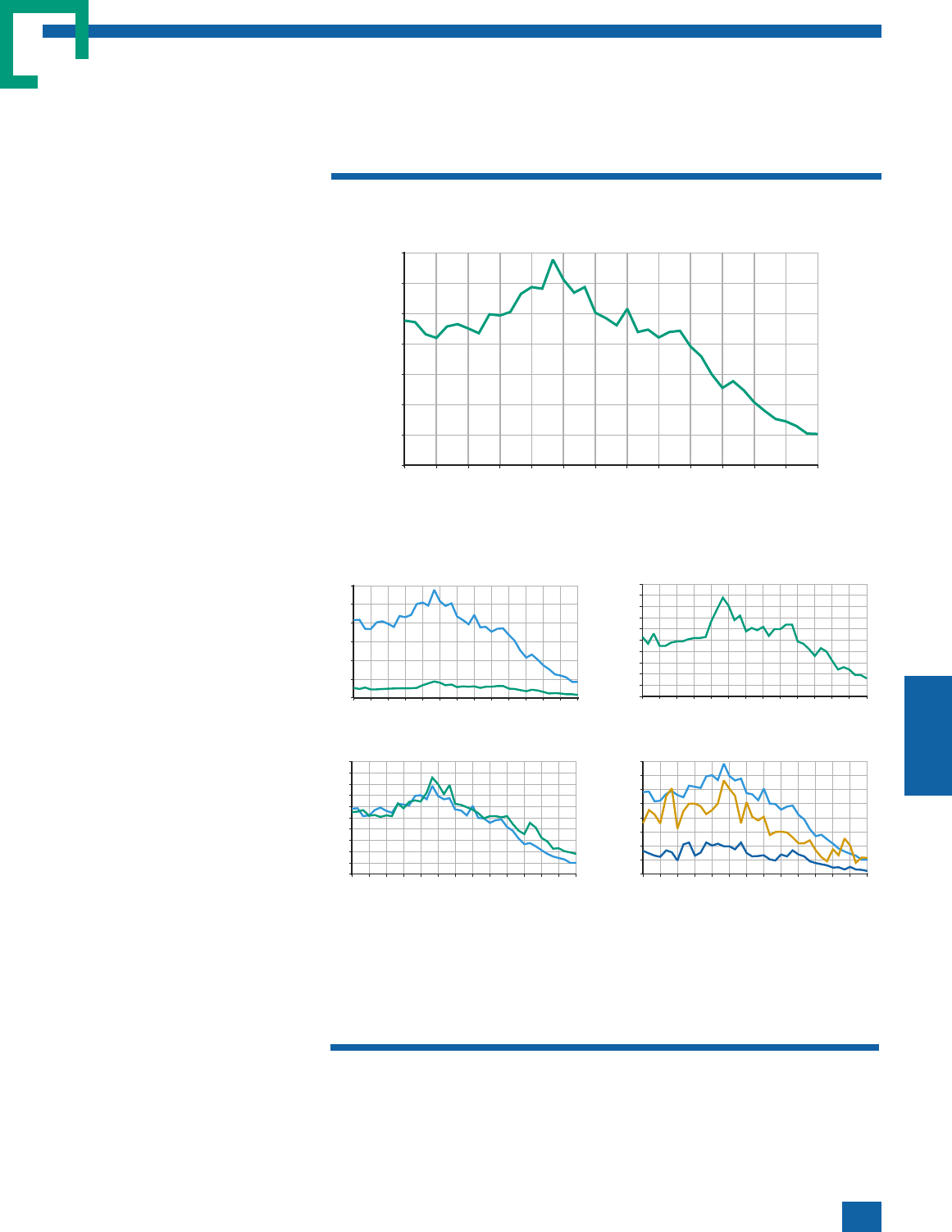

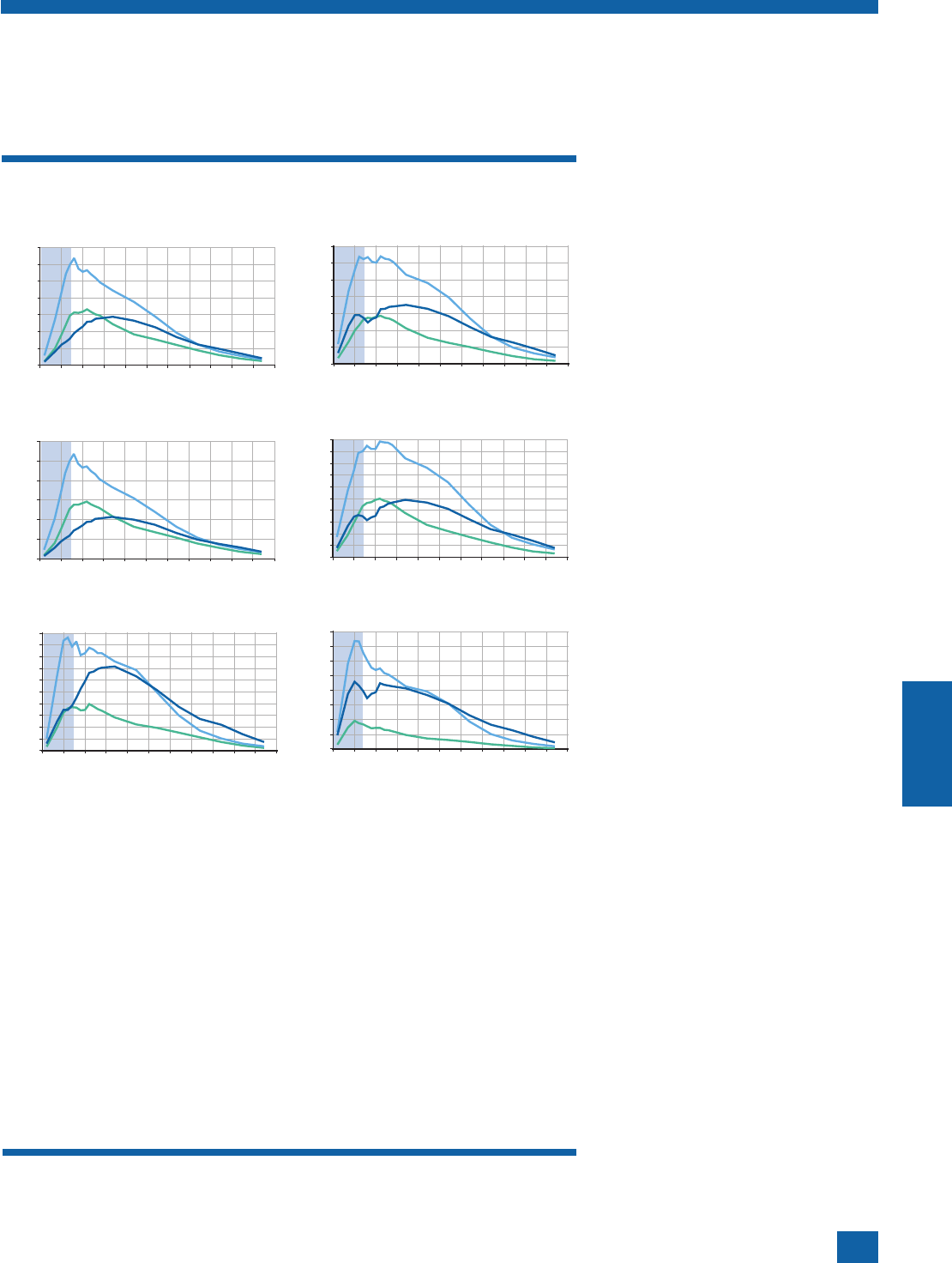

Birth rates in 2019 for both females ages 15–17 and young adults ages

18–19 were at their lowest level since 1970

55 59 63 67 71 75 79 83 87 91 95 99 03 07 11 15 19

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Year

Births per 1,000 females ages 15−19

Birth rate

Births to unmarried females

Percent of births to females ages 15−19

71 77 83 89 95 01 07 13 19

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Year

Births per 1,000 females in age group

Ages 15−17

Ages 18−19

71 77 83 89 95 01 07 13 19

0

10

20

30

40

Year

Births per 1,000 females in age group

Ages 15−17

Q The birth rate for teens ages 15–17 fell 21% between 1970 and 1986 and then in-

creased over the next 5 years back to its 1970 level. The birth rate for young adult

females ages 18–19 dropped even more than the rate for teens ages 15–17 be-

tween 1970 and 1986, falling 31%. Although the rate for young adults also in-

creased through 1991, the rate did not return to its 1970 level.

Q Since 1991, teen birth rates declined considerably; by 2019, the rates for both age

groups reached their lowest level since at least 1970.

The annual birth rate for females ages 15–19 declined substantially

between 1955 and 2019, while the proportion of these births that were

to unmarried women increased

Q In 1955, about 14% of births to females ages 15–19 were to unmarried women. By

2019, that proportion grew to 91%.

Source: Authors’ adaptation of Martin et al.’s Births: Final Data for 2019,

National Vital Statistics Re-

ports

, 70(2); National Center for Health Statistics’ annual series, Births: Final Data,

National Vital Statis-

tics Reports

, for the years 2000–2009; and Ventura et al.’s Births to Teenagers in the United States,

1940–2000,

National Vital Statistics Reports

, 49(10).

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

15

Birth rates for females ages 15–17 varied greatly across states in

2019, ranging from 1.7 in New Hampshire to 12.6 in Mississippi

Births per 1,000 females in age group, 2019

Ratio of ages

15–17 to 18–19State Age 15–19 Ages 15–17 Ages 18–19

United States 16.7 6.7 31.1 22%

Alabama 25.6 10.1 47.8 21

Alaska 18.3 6.2 39.9 16

Arizona 18.5 8.3 33.0 25

Arkansas 30.0 11.2 58.3 19

California 12.4 5.0 23.1 22

Colorado 13.9 6.1 25.7 24

Connecticut 7.7 3.3 13.5 24

Delaware 14.9 6.7 25.8 26

Dist. of Columbia 16.8 11.8 20.2 58

Florida 16.2 6.1 31.3 19

Georgia 19.7 8.0 36.8 22

Hawaii 15.7 5.4 32.0 17

Idaho 14.9 5.0 30.7 16

Illinois 14.6 5.8 28.0 21

Indiana 20.8 7.9 39.5 20

Iowa 14.1 5.1 26.5 19

Kansas 19.2 7.3 36.8 20

Kentucky 24.9 9.4 47.6 20

Louisiana 27.8 10.9 53.9 20

Maine 9.1 2.7 18.0 15

Maryland 13.9 6.0 25.5 24

Massachusetts 6.9 3.0 11.3 27

Michigan 15.1 5.5 28.9 19

Minnesota 10.1 3.7 19.9 19

Mississippi 29.1 12.6 53.1 24

Missouri 20.3 7.6 39.2 19

Montana 16.3 6.1 32.0 19

Nebraska 15.3 6.7 27.8 24

Nevada 18.9 7.0 39.5 18

New Hampshire 6.6 1.7 13.2 13

New Jersey 10.0 4.1 19.6 21

New Mexico 24.4 10.8 44.8 24

New York 11.4 4.7 20.6 23

North Carolina 18.2 7.7 32.6 24

North Dakota 15.6 5.3 29.5 18

Ohio 18.8 6.9 36.0 19

Oklahoma 27.4 11.0 52.1 21

Oregon 12.1 4.1 24.0 17

Pennsylvania 13.3 6.0 23.1 26

Rhode Island 10.0 4.7 15.6 30

South Carolina 21.6 8.5 39.8 21

South Dakota 19.2 8.6 34.9 25

Tennessee 23.7 8.9 46.6 19

Texas 24.0 10.7 44.6 24

Utah 12.0 3.8 24.9 15

Vermont 7.6 3.0 12.3 24

Virginia 13.6 5.3 25.1 21

Washington 12.7 4.5 25.4 18

West Virginia 25.2 9.1 49.3 18

Wisconsin 12.5 4.5 24.0 19

Wyoming 19.4 6.6 39.2 17

Q

Comparing birth rates for females ages 15–17 with those of young adults (ages 18

and 19) shows that the 15–17-year-old rate ranged from 13% of the young adult rate

in New Hampshire to 30% of the young adult rate in Rhode Island and 58% in the

District of Columbia.

Source: Authors’ adaptation of Martin et al.’s Births: Final Data for 2019,

National Vital Statistics

Reports

, 70(2).

The teenage birth rate in the

U.S. ranks among the highest

of industrialized nations

Birth rates for a large number of

countries are collected and dissemi-

nated by the World Health Organi-

zation. The most recent data avail-

able for industrialized countries

were not available for a common

year but ranged from 2016 to 2019.

Births per 1,000 females ages 15–19

Country

Birth

rate

Data

year

Russian Federation 21.5 2016

United States 16.7 2019

New Zealand 13.3 2019

United Kingdom 11.9 2018

Australia 9.4 2018

France 8.6 2018

Greece 8.6 2018

Israel 8.2 2018

Portugal 7.3 2018

Germany 7.2 2018

Canada 6.6 2018

Ireland 6.2 2018

Spain 6.2 2018

Austria 5.5 2018

Belgium 5.5 2018

Finland 4.3 2018

Sweden 4.2 2018

Italy 4.1 2018

Japan 3.1 2018

Netherlands 2.6 2018

Norway 2.6 2018

Switzerland 2.3 2018

Denmark 2.0 2019

Source: Authors’ adaptation of the

World Health Organization’s Global

Health Observatory, Adolescent Birth

Rate (per 1000 Women Aged 15-19

Years).

The birth rate for U.S. females ages

15–19 remained one of the highest

among industrialized nations. In

2010, however, the U.S. birth rate

for females ages 15–19 occupied

the top spot on this list. Following a

50% decline since 2010, the U.S.

rate now ranks second, more than

20% below the most recent rate for

the Russian Federation, but about

25% above the rate for New Zea-

land.

Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report

16

The high school dropout rate declined in the last 5 years, yet

more than 470,000 youth left high school in 2019

The dropout rate varies across

demographic groups

The National Center for Education

Statistics (NCES) publishes annual sta-

tistics of (1) the number of persons in

grades 10–12 who dropped out of

school in the preceding 12 months,

and (2) the percent of persons ages

16–24 who were dropouts. The first

statistic (the event dropout rate) pro-

vides an estimate of flow into the

dropout pool. The second statistic (the

status dropout rate) provides an esti-

mate of the proportion of dropouts in

the young adult population. Event

dropout rates are based on data from

the annual October Current Popula-

tion Survey (CPS). The CPS and the

American Community Survey (ACS)

are the sources for the status dropout

estimates.

Approximately 4 of every 100 persons

(4%) enrolled in high school in Octo-

ber 2018 left school before October

2019 without successfully completing a

high school program—in other words,

in the school year 2018-2019, about

470,000 youth dropped out and the

event dropout rate was 4.3%. The

2019 event dropout rate for males

(4.1%) was slightly lower than for fe-

males (4.5%), and the rates for White

(4.0%) and Black (4.1%) youth, were

less than the rate for Hispanic (5.7%)

youth.

Dropout rates are greater for

institutionalized youth than

noninstitutionalized youth

Over the years, demographic disparities

in annual event dropout rates have ac-

cumulated to produce noticeable dif-

ferences in status dropouts rates—i.e.,

the proportion of young adults (person

ages 16–24) who are not enrolled in

school and have not completed high

school (or received an equivalency cer-

tificate). The status dropout rate mea-

sure typically includes civilian, nonin-

Notes: Race groups exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity can be of any

race.

Source: Author’s adaptation of National Center for Education Statistics,

Digest of Education Statistics:

2019

, Table 219.55.

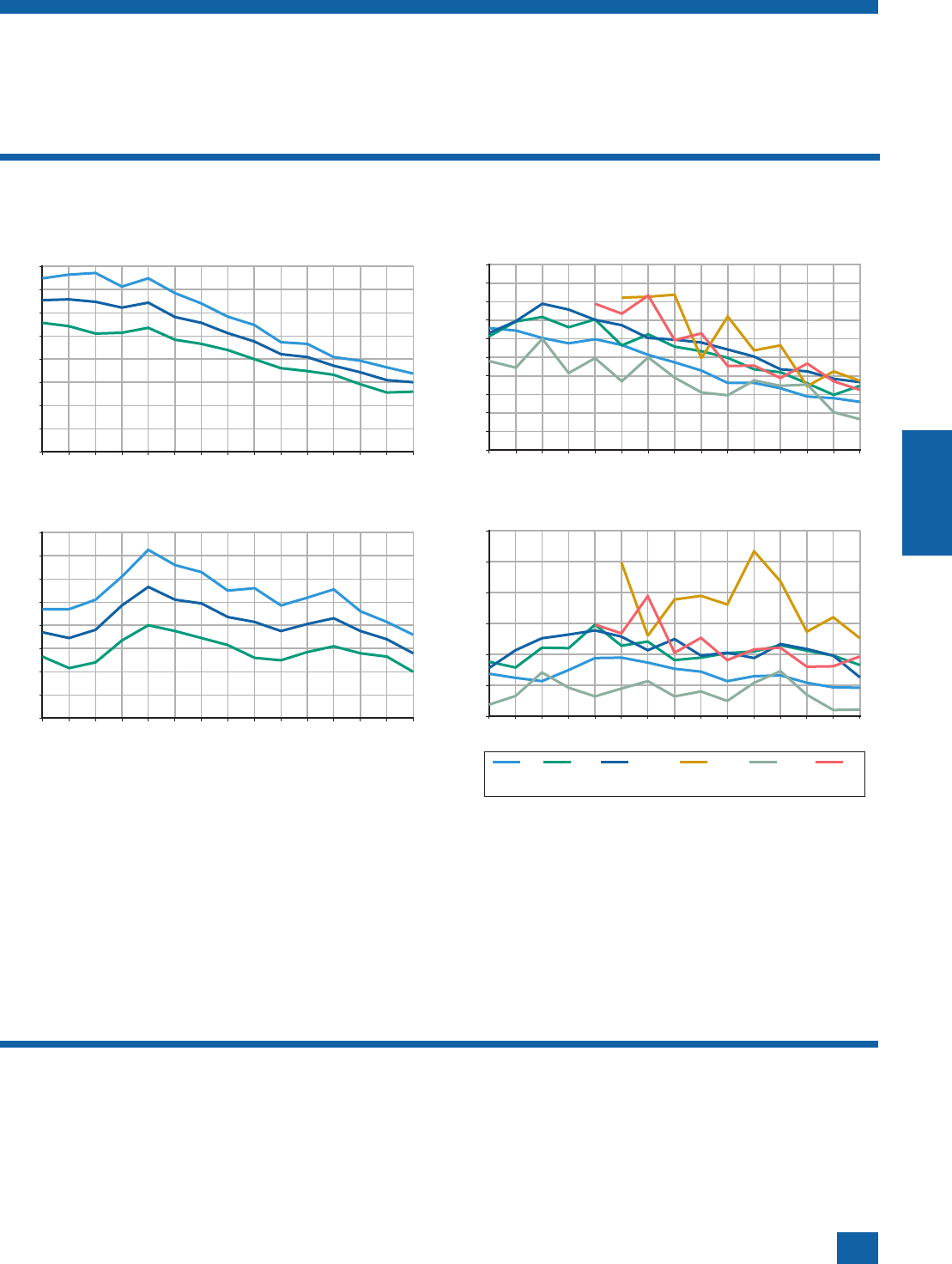

In 2019, dropout rates were highest for females, Hispanic youth, and

students living in western states

Total Male Female White Black Hispanic North-

east

Mid-

west

South West

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

4.3%

4.1%

4.5%

4.0%

4.1%

5.7%

4.5%

3.2%

3.7%

6.0%

Percent of youth who dropped out of grades 10−12 in the preceeding 12 months

Notes: Race groups exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity can be of any

race.

Source: Author’s adaptation of National Center for Education Statistics,

Digest of Education Statistics:

2019

, Table 219.55.

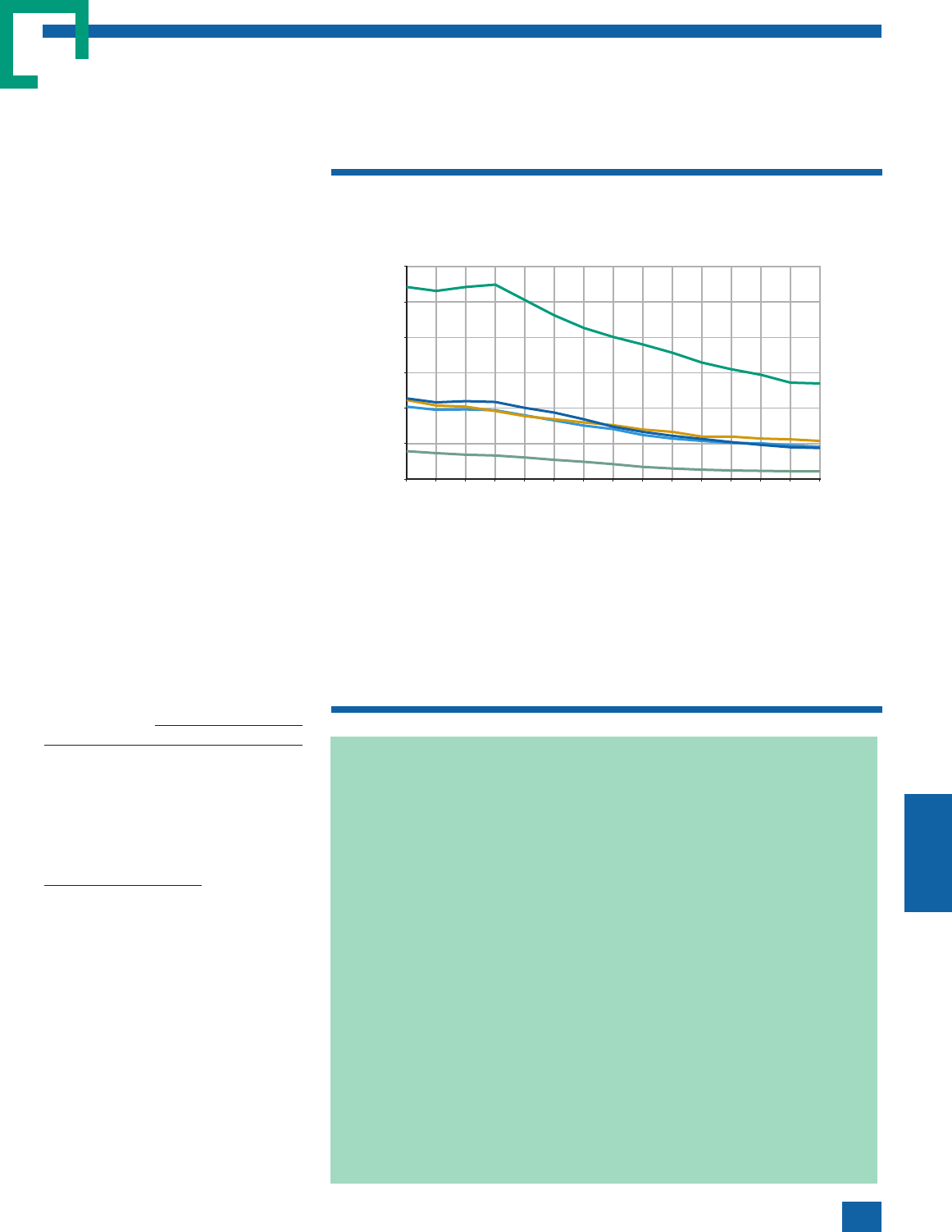

Dropout rates for White youth have remained below the rates of Black

and Hispanic youth

91 93 95 97 99 01 03 05 07 09 11 13 15 17 19

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

Percent of youth who dropped out of grades 10−12 in the preceding 12 months

Hispanic

Black

White

Total

Year

Chapter 1: Youth population characteristics

17

stitutionalized 16–24-year-olds. Youth,

such as those who are incarcerated or

in the military, are not included. How-

ever, the ACS allows for comparisons

of status dropout rates for 16–24-year-

olds living in households and noninsti-

tutionalized group quarters (i.e., col-

lege housing or military housing

located within the U.S.) with those liv-

ing in institutionalized group quarters

(i.e., prisons, nursing facilities, or other

healthcare facilities). Regardless of

race/ethnicity, status dropout rates

were substantially higher for institu-

tionalized youth than for other youth.

In 2019, the status dropout rate was

30% for institutionalized youth and 5%

for those living in households and non-

institutional group quarters.

Educational failure is linked to

unemployment

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

estimates that 38% of the 2018-2019

school year dropouts ages 16–24 were

in the labor force (employed or actively

looking for work), though 15% of

those dropouts were unemployed. In

comparison, 72% of the 2019 high

school graduates who were not in col-

lege were in the labor force, and a

greater proportion of this workforce

(18%) was unemployed.

Failing to complete high school

results in lower earnings

According to the Career Outlook re-

port by BLS, persons ages 25 and

older with less than a high school di-

ploma had the lowest median weekly

earnings and the highest unemploy-

ment rate. In 2019, for example, the

median weekly earnings among persons

ages 25 and older was 20% less for

those without a high school diploma

than those who completed high

school, and more than 50% less than

persons with a bachelor’s degree.

Q Among 25–34-year-olds who worked full-time, year-round in 2019, the median

earnings of those whose highest level of education was a high school diploma was

about 20% higher than those who did not complete high school, and the median

earnings of those who completed a bachelor’s or higher degree was more than

twice that of persons who did not complete high school.

*Includes equivalency credentials, such as the GED.

Source: Author’s adaptation of Irwin et al’s

Report on the Condition of Education

.

In 2019, persons who completed high school earned about $5,700 more

than those who did not complete high school

All

education

levels

Less than

high school

completion

High

school

completion*

Some

college,

no degree

Associate’s

degree

Bachelor’s

degree

or higher

$0

$10,000

$20,000

$30,000

$40,000

$50,000

$60,000

$70,000

$46,700

$29,300

$35,000

$39,700

$40,000

$59,700

Median annual earnings of full-time, year-round workers ages 25−34, 2019

The status dropout rate decreased for both noninstitutionalized and

institutionalized youth between 2010 and 2019

Status dropout rate

Noninstitutionalized Institutionalized

Race/ethnicity 2010 2019 2010 2019

Total 8% 5% 37% 30%

White, non-Hispanic 5 4 29 22

Black, non-Hispanic 9 5 42 35

Hispanic 16 7 44 35

American Indian/Alaskan Native 15 9 39 26

Asian 3 2 28 31

Two or more races, non-Hispanic 6 5 23 25

Q Among noninstitutionalized youth, American Indian/Alaskan Native and Hispan-

ic youth had higher status dropout rates than all other racial groups in 2010

and 2019. For institutionalized youth, Black and Hispanic youth had higher sta-

tus dropout rates in both years.

Q The status dropout rate among institutionalized youth decreased among most