NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

DISTRIBUTIONAL NATIONAL ACCOUNTS:

METHODS AND ESTIMATES FOR THE UNITED STATES

Thomas Piketty

Emmanuel Saez

Gabriel Zucman

Working Paper 22945

http://www.nber.org/papers/w22945

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

December 2016

We thank Tony Atkinson, Oded Galor, David Johnson, Arthur Kennickell, Jean-Laurent

Rosenthal, John Sabelhaus, David Splinter, and numerous seminar and conference participants

for helpful discussions and comments. Antoine Arnoud, Kaveh Danesh, Sam Karlin, Juliana

Londono-Velez, Carl McPherson provided outstanding research assistance. We acknowledge

financial support from the Center for Equitable Growth at UC Berkeley, the Institute for New

Economic Thinking, the Laura and John Arnold foundation, NSF grant SES-1559014, the Russell

Sage foundation, the Sandler foundation, and the European Research Council under the European

Union's Seventh Framework Programme, ERC Grant Agreement No. 340831. The views

expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National

Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2016 by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. All rights reserved. Short

sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission

provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.

Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States

Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman

NBER Working Paper No. 22945

December 2016

JEL No. E01,H2,H5,J3

ABSTRACT

This paper combines tax, survey, and national accounts data to estimate the distribution of

national income in the United States since 1913. Our distributional national accounts capture

100% of national income, allowing us to compute growth rates for each quantile of the income

distribution consistent with macroeconomic growth. We estimate the distribution of both pre-tax

and post-tax income, making it possible to provide a comprehensive view of how government

redistribution affects inequality. Average pre-tax national income per adult has increased 60%

since 1980, but we find that it has stagnated for the bottom 50% of the distribution at about

$16,000 a year. The pre-tax income of the middle class—adults between the median and the 90th

percentile—has grown 40% since 1980, faster than what tax and survey data suggest, due in

particular to the rise of tax-exempt fringe benefits. Income has boomed at the top: in 1980, top

1% adults earned on average 27 times more than bottom 50% adults, while they earn 81 times

more today. The upsurge of top incomes was first a labor income phenomenon but has mostly

been a capital income phenomenon since 2000. The government has offset only a small fraction

of the increase in inequality. The reduction of the gender gap in earnings has mitigated the

increase in inequality among adults. The share of women, however, falls steeply as one moves up

the labor income distribution, and is only 11% in the top 0.1% today.

Thomas Piketty

Paris School of Economics

48 Boulevard Jourdan

75014 Paris, France

Emmanuel Saez

Department of Economics

University of California, Berkeley

530 Evans Hall #3880

Berkeley, CA 94720

and NBER

Gabriel Zucman

Department of Economics

University of California, Berkeley

530 Evans Hall, #3880

Berkeley, CA 94720

and NBER

1 Introducti on

Income inequality has i n cr ea sed in many developed countries over the last se veral decades.

This trend has attrac te d considerable interest among academics, polic y- m akers, and the gen er a l

public. In recent years, followin g up on Kuznets’ (1953) pioneering attempt, a number of authors

have used administrative tax records to construct long-run series of top income shares (Alvaredo

et al., 2011-2016). Yet despite this endeavor, we still face three importa nt l i m i t at i o n s when

measuring income inequality. First and most importa nt, there is a larg e gap between nation al

accounts— wh i ch focus on macro totals and growth—and inequality studies—which focus on

distributions using survey and t a x data, usu al l y without trying to be ful l y consistent with

macro totals. This gap makes it hard to address questions such as: What fraction of economic

growth accrues to the bo t t om 50%, the middle 40%, and the top 10% of the distribution? How

much of the rise in income inequality owes to changes in the share of labo r and capital in national

income, and how much to changes in the dispersion of labor earni n gs , capital ownership, and

returns to capital? Second, about a third of U.S. national income is redistributed through taxes,

transfers, and public good spending . Yet we do not have a good measure of how the distribution

of pre-ta x income differs from the distribution of po st -t a x income, mak i n g it hard to assess how

government redi st ri b u t i o n affects inequality. Th i rd , existing income inequality st a t i st i cs use the

tax unit or the household as unit of observation, ad d i n g up t h e i n co m e of men an d women. As a

result, we do not have a clea r vi ew of how long-run trends in income concentration are shaped by

the major changes in women labor force participation—and gender inequality general l y— th a t

have occurred over the last century.

This paper attempts to compute ineq u a l i ty statistics for the United States that overcome the

limits of existing series by creating distributional national accounts. We combine tax, survey,

and n a t i on a l accounts data to bui l d new series on the distribution of national inc om e since

1913. In contrast to previo u s attempts that capture less than 60% of US n at i on a l income—

such as Census bureau estimates (US Census Bureau 2016) and top income shares (Piketty

and Saez, 2003)—our estimates capture 100% of the nati o n al income recorded in the natio n a l

accounts. This enables us to provide decomposit i o n s of growth by income groups consistent

with macroeconomic growth. We co m p u t e the distribution of both pre-tax and post -t ax income.

Post-tax series deduct all tax es and add back all transfers and publi c spending, so that both

pre-tax and post-tax in co m es add up to national incom e. This al l ows us to provide the first

comprehensive view of how government redistribution affects inequality. Our benchmark series

uses the adult individual as the unit of obser vation and splits in co me eq u al l y a m o n g spouses.

1

We also rep o r t series in which each spous e is assigned her or his own labor income, enabling us

to study how long-run changes in gender inequality shape the distribution of i n co m e.

Distributional nation al accounts provide information on the dynamic of income acro ss the

entire spectrum—from the bottom decile to the top 0. 00 1% — th a t , we believe, is more accurate

than existing inequality data. Our estimates capture employee fringe benefits, a growin g source

of income for the middle-class that is overlooked by both Census bureau estimates and tax

data. They capture all capital income, which is large—about 30% of total national income—

and concentrated, yet is very imperfectly covered by surveys—due to small sample and top

coding issues—and by tax data—as a large fraction of capit a l income g oes to pension funds and

is re ta i n ed in corporations. They make it possible to produce long-run inequality statistics that

control for socio-demographic changes—such as the rise in the fraction of retired individuals

and the decline in household size—contrary to the currently available tax-based series.

Methodologically, our contribution is to construct mic ro -fi l e s of pre-tax and post-tax income

consistent with macro aggregates. These micro-files contain all the variables of the national

accounts and synthetic individ u a l observations that we obtain by statistical l y match i n g tax

and survey data and making explicit assumptions about the distribution of income categories

for whi ch there is no directly available source of i n fo r m at i o n . By construction, the t o t al s in

these micro-files add up to the national accounts totals, while the distributions are consistent

with those seen in tax and survey d a t a. These files can be used to compute a wide array

of distributional statistics—labor and capi ta l i n co m e earne d , taxes paid, transfer s rece i ved,

wealth owned, etc. —by age groups, gender, and marital status. Our objective, in the years

ahead, is to c on st r u ct similar micro-files in as many countries as possible in order to better

compare inequality across countries.

1

Just like we u se GDP or national income to compare the

macroeconomic performances of countries today, so coul d distributional national accounts be

used to compare ineq u a l i ty across countries tomorrow.

We stress at the outset that there are numerous data issues involved in distributing national

income, discussed in the text and the online appendix.

2

First, we take the national accou nts

as a given sta rti n g point, although we a r e well aware that the national accounts themsel ves are

imperfect (e. g. , Zucman 2013). They are, however, the most reasona b l e starting point, because

they aggregate all the available information from surveys, tax data, corporate income state-

1

All updated files and results will be made available on-line on the World Wealth an d Income Database

(WID.world) website: http://www.wid.world/. All the US results and data are also posted at http:

//gabriel-zucman.eu/usdina/.

2

The online appendix is available at http://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/PSZ2016DataAppendix.pdf.

2

ments, and balance sheets, etc., in an standardized, internationally-agr eed -u pon and regularly

improved upon accounting framework. Secon d , impu t i n g all national income, taxes, transfers,

and public goods spending requires making assumptions on a number of complex issues, such as

the economic incidence of taxes and who benefits from government spending. Our goal is not to

provid e definiti ve answers to these questions, but rather to be comprehensive, consist ent, and

explicit about what assumptions we are making and why. We view our paper as attempting to

construct prototyp e distributional national accounts, a pr ot o type that could be improved upon

as more dat a become available, new knowledge emerges on who pays t ax es and benefits from

government spend i n g , an d refined estimat i o n techniques are developed—just as today’s national

accounts are regularly improved.

The analysis of our US distributional national acco u nts yield s a number of striking findings.

First, our data show a sharp diverge n ce in the growth experienced by the bottom 50% versus

the rest of th e economy. The average pre-tax income of the bottom 50% of adults has stagnated

since 1980 at a bout $16,000 per adult (i n constant 2014 dollars, using the national income

deflator), while average national income per adult has grown by 60% to $64,500 in 2014. As a

result, the bottom 50% income share has coll ap se d from about 20% in 1980 to 12% in 2014. In

the meantime, the average pre-tax income of top 1% adu l ts rose from $420,000 to about $1.3

million, and their income share increa sed from about 12% in the early 1980s to 20% in 2014.

The two gr o u p s have essential l y switched their income shares, with 8 points of national income

transferred from the bottom 50 % to the top 1%. The top 1% income shar e is now almost twice

as lar g e as the bottom 50% s h are, a group th a t is by definition 50 t i m es more numerous. In

1980, top 1% adults earned on average 27 times more than bottom 50% adults before tax while

today they earn 81 times more.

Second, gover n m ent redistribut i on has o ffse t only a small fraction of the increase in pre-tax

inequality. Even after taxes and transfe rs , there has been close to zero growth for working-age

adults in the bottom 50% of the distribution since 1980. The aggregate flow of individualized

government transfers ha s increased, but these transfers are largely targeted to the elderly and

the middle-class (individuals above the me d i an and below the 90th percentile). Transfers that

go to the bottom 50% have not been large enough to lift income significantly. Given the massive

changes in the pre-tax di st r i b u t i on of natio n a l income si n ce 1980, there are clear limits to what

redistributive policies can achieve. In light of the collapse of bottom 50% primary incomes,

we feel th a t policy discussions should focus on how to equalize the distribution of p r i m a ry

assets, including human capital, financial capital, and bargaining power, rather than merely

3

ex-post redistribution. Poli ci es that could raise bottom 50% pre-tax incomes include improved

education and access to skills, which may r eq u i re major changes in the system of education

finance and admission; reforms of l a bo r m a rket institutions, in cl u d i n g minimu m wage, corporate

governance, and wo r ker co-determination; and steeply progressive taxation, which can affect pay

determination and pre-tax distr i b u t i on , particularly at the top end (see, e.g., Piketty, Saez and

Stantcheva 2014, and Piketty 2014).

Third, we find that the upsurge of top incomes has mostly been a capital- d r i ven phenomenon

since the lat e 1990s. There is a widespread view that rising income inequ al i ty most ly owes to

booming wages at the top end, i.e., a rise of the “wor k i n g rich.” Our results confirm that this

view is correct from the 1970s to the 1990s. But in contra st to earlier decades, the increase in

income concentration over the last fifteen years owes to a boom in the in com e from equity and

bonds at the top. The working rich are either turning into or bei n g replaced by rent i er s. Top

earners became younger in the 1980s and 1990s but have been growing older since then.

Fourth, the r ed u c ti o n in the gender gap has mitigated the increase in inequality among

adults since the la te 1960s, but the United States is still characterized by a spectacular glass

ceiling. When we allocate labor incomes to indivi d u a l earners (instead of splitting it equally

within couples , as we do in our benchmark series), the rise in inequality is less drama tic , than k s

to the rise of female labor market participation. Men aged 20-64 earned on average 3.7 times

more labor income than women aged 20-64 i n the early 1960s, while they earn 1.7 times more

today. Until the early 1980s, the top 10%, top 1%, and top 0.1% of the labor income distribution

were less than 10% women. Since then, this share has increased, but the increase is smaller the

higher one moves up in the distrib u t i on . As of 2014, women make only about 16% of the top

1% lab o r income earners, and 11% of the top 0.1%.

The paper is organized as fol l ows. Section 2 relates our work to the existing literature.

Section 3 lays out our methodology. In Section 4, we present our results on the distribution

of pre-tax and post-tax national income, and we provide decompositions of growth by income

groups consistent with macroeconomic growth. Sectio n 5 analyze s the role of changes in gender

inequality, factor shares, and taxes and transfers for the dynamic of US i n co m e inequality. S ec-

tion 6 compa r es and reconciles our r esu l t s with previous estimates of US income con centration.

We conclude in Secti on 7.

4

2 Previous Attempts at Introducing Distributional Mea-

sures in the National Accounts

There is a long tradition of research attempting to introdu ce distributional measures in the

national accounts. The first national accounts in history—the famou s social tables of King

produced in the late 17th century—were in fact distributional national accounts, showing the

distribution of England’s income, consump t i o n , and saving across 26 social classes—from tem-

poral lords and baronets down to vagrants—in the year 1688 (see Barnet t , 1936). In the Uni t ed

States, Kuz n et s was interested in both national income and i ts distribut i o n and made path-

breaking advances on both fronts (Kuznets 1941, 19 53 ) .

3

His innovation wa s estimating top

income shares by combining tabulations of federal income tax returns—from wh i ch he derived

the income o f top earners using Pareto extrapolations—and newly constructed national accounts

series—that he used to compute the total incom e denominato r. Kuznets, however, did not fully

integra t e the two approa ches: his inequality series capture taxable income only and mis s all

tax-exempt cap i t al and labor income. The top income shares later computed by Piketty (2001,

2003), Piketty and Saez (2003), Atkinson (2005) and Alvaredo et al. (2011-2016) extended

Kuznets’ methodology to more countries and years but did not address this shortcoming.

Introdu ci n g distri b u t i on a l measures in the national accounts has received ren e wed i nterest

in recent years. In 2009, a report from the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Per-

formance an d Social Progress emphasized the impor t an c e of incl u d i n g distributional measures

such as household income quintiles in the Sy st em of National Account s (Stiglitz, Sen and Fi-

toussi, 2009). In response to th i s report, a number of countries, su ch as Australia, introduced

distributional statistics in their national accounts (Australian Bureau of Statistic, 2013) while

others are i n the process of doing so. Furlong (2014), Fixler and Johnson (2014), McCully

(2014), and Fixler et al. (2015) describe the ongoing U.S. effort, which focuses on scaling u p

income from the Cur re nt Population Survey to match personal income.

4

There are two main methodological differences between our paper and the work currently

conducted by statistical agencies. Fi r st , we start with tax data—rather than surveys—that we

supplement with surveys to capture forms of income that are not visible in tax returns, s u ch

as tax-exempt transfers. The use of tax data is critical to capture the to p of the d i st ri b u t i o n ,

3

Earlier attempts include King (1915, 1927, 1930).

4

Using tax data, Auten and Splinter (2016) have recently produced US income conc entration stati s t ic s since

1962 that improve upon the Piketty and Saez ( 2003) fiscal income series by distributing total personal income

(instead of total pre-tax and post-tax national income as we do here) from the national accounts. We view their

work as complementary to ou rs .

5

which ca n n ot be studied properly with s u rveys becau s e o f top-coding, insu ffi ci e nt over-sampling

of the top, sampling errors, or non-sam p l i n g errors.

5

Second, we are primarily inte re st ed in

the distribution of total n at i o n al income rather than household or personal income. National

income is in our view a m o r e meaningful starting point, because it is interna t i on a l l y comparable,

it is the aggregate used to comp u t e macroeconom i c growth, and it i s comprehensi ve, including

all forms of in co m e that eventually accrue to in d i v i d u a l s.

6

While we focus on national income,

our micro-files can be used to st u d y a wide range of income concepts, i n cl u d i n g the household

or perso n a l income concepts more traditionally analyzed.

Little work has contrasted the distributio n of pre-tax income with that of post -t ax income.

Top income sha r e studies only deal with pre-tax income, as many forms of transfers are tax-

exempt. Official income st a ti s ti c s fr om the Census Bureau focus on pre-tax income and include

only some government transfers (US Census Bureau 2016).

7

Congressional Bu d g et Office esti-

mates compute both pre-tax and post-tax inequality measures, but they include only Federal

taxes and do not try to incorporate government consumption (US Congressional Budget Office

2016). By contrast, we at t em pt to allocate all taxes (in cl u d i n g State and local taxes) and all

forms of government spending in order to provide a comprehensive view of how government

redistribution affects inequality.

Last, there is a large and growing theoretical literature jointly analyzing economic growth

and income dist ri b u t i o n . Historically, the Kuznets curve theory of how inequality evolves over

the path of development ( Ku zn e ts , 1955) came out of the seminal empirical work by Kuznets

(1953) on US incom e inequality. We hope that our estimates will similarly be fruitful to stimulate

future theoretical work on the interplay between growth and inequality.

8

5

Another possibil i ty would be to use the CPS as the baseline dataset and supplement it with tax data for the

top decile, where the CPS suffers from small samples, poorly measured capital income, and top-coding issues.

The advantage of starting from the CPS would b e that it has been the most widely known and used dataset to

analyze US income and wage inequality for many decades. We leave this alternative approach to future work.

6

Per son al income is a concept that is specific to the U.S . National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

It is an ambiguous concept (neither pre-tax, nor post-tax), as it does not deduct taxes but adds back cash

government transfers. The System of National Accounts (United Nations, 2009) does not us e personal income.

7

In our v i ew, not deducti n g taxes but counting (some) transfers is not conceptually meaningful, but it parallels

the definition of personal income in the US national accounts.

8

In recent decades, a lot of the work on inequality and growth has focused on the role of credit constraints

and wealth inequality (see, e.g., Galor and Zeira, 1992). Our data jointly capture wealth, capital income, and

labor income, making it possible to cast light on this debate and to study changes in the structure of inequality,

e.g., the extent to w hi ch there has truly been a demise of the capitalists-workers class structure (Galor and Moav

2006).

6

3 Methodolo gy to Distribute US N a ti ona l Income

In this section, we outline the main concepts and methodology we use to distribute US national

income. All the data sou r ce s and computer code we use are described in Online Appendix A;

here we focus on the main conceptual issues.

9

3.1 The Income Concept We Use: National Income

We are interested in the distribution of total national income. We fo l l ow the official definition of

national income codified in the latest System of National Accounts (SNA, United Nati on s, 2009),

as we do for all other national accounts concepts used in this paper. National i n co m e is GD P

minus capital dep r eci a t i on plus net income recei ved from abroad. Although macroeconomists,

the press, and the general public often focus on GDP, na t i on a l income is a more meaningful

starting point for two re aso n s. First, capital depreciation is not economic incom e: it does

not allow one to consume or accumulate wealth. Allocating depreciation to individuals woul d

artificially inflate the economic income of capital owners. Second, including foreign income is

important, because for ei gn dividends and interest are sizable f or top earners.

10

In moving away

from GDP and toward national income, we follow one of the recommendations m ad e by the

Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi (2009) commission and also return to the pre-World War II focus on

national income (King 1930, Kuzne ts , 1941).

The national income of the United States is the sum of all the labor i n co m e—t h e flow return

to human capital—and capital income—the flow ret u r n to non-human capital—that accrues

to U.S. resident individuals. Some parts of national income never show up on any person’s

bank account, but it is not a reason to ignore them. Two prominent examples are the imputed

rents of homeowners and taxes. First, there is an economic return to owning a house, whether

the house is rented or not; national income therefore includes bot h monetary rents—for houses

rented out —a n d im p u t ed rents—for owner-o ccu p i e rs . Secon d , some income is immediately pai d

to the government in the form of payroll or corporate ta x es, so that no individual ever feels it

9

A discussion of the general issues involved in creating distributional national accounts is presented in Al-

varedo et al. (2016). These guidelines are not specific to the United States but they are based on the lessons

learned from constructing the US distribut i on al national accounts presented here, and from similar on-going

projec t s in other countries.

10

National income also includes the sizable flow of undistributed profits reinvested in foreign companies that

are more than 10% U.S.-owned (hence are class i fie d as U.S. d ir e ct investments abroad). It does not, however,

include undistributed profits reinvested in foreign companies in which the U.S. owns a share of less than 10%

(classified as portfolio investments). Symme tr i cal l y, national income deducts all t h e primary income paid by the

U.S. to non-residents, including the undistributed profits reinvested in U.S. companies that are more than 10%

foreign-owned.

7

earns th a t fractio n of national income. But these taxes are part of the flow return to capital and

labor and as such accrue to the owners of the factors of production. The same is true for sales

and excise taxes. Out of their sales proceeds at market prices (including sales taxes), producers

pay workers labor income and owners cap i t al income but must also pay sales and excise taxes to

the government. Hence, sales and excise taxes are part of national income even if they are not

explicitly part of employee compensation or profits. Who exactly earns the fraction of nationa l

income pai d in the form of corporate, payroll, and sales taxes is a tax in ci d en c e question to

which we return in Secti on 3.3 bel ow. Although national income inclu d es all th e flow retur n

to the factors of production , it does not include the ch a n g e in the price of these factors; i.e., it

excludes the capital gains caused by pure asset price changes.

11

National in co m e is larger an d has been g r owing faster than the other income concepts tr ad i -

tionally used to study in eq u al i ty. Figure 1 provides a reconciliation betwe en national income—as

recorded in the national accounts—a n d the fiscal income reported by ind i v i d u a l taxpayers to the

IRS, for labor and capital income separately.

12

About 70% of national income is labor income

and 30% is capital income. Although most of national labor income is reported on tax returns

today, the gap between taxable labor income and national labor income has been growing over

the last several decades. Untaxed l a bor income includes tax-exempt fringe benefits, employer

payrol l taxes, the labor income of non filers (large before the early 1940 s) and unreported labor

income due to tax evasion. The fraction of labor income which is taxable has declined from 80%-

85% in the post-Wor l d War II decades to just under 70% in 2014, due to the rise of employee

fringe benefits. As for capital, on l y a third of total capital income is reported on tax returns.

In addition to the imp u t ed rents of homeowners and various taxes, untaxed capital income in-

cludes the di v i d end s and interest paid to tax-exempt pension accounts, and corporate retained

earnings. The l ow ratio of taxable to t ot a l capital income is not a new p h en o m eno n —t h er e is no

trend in this ratio over time. However, when taking into account both labor and capital incom e,

the fraction of national income that is reported in individual income tax da t a has declined from

70% in the late 1970s to about 60% today. This result implies that tax data un d er -e stimate

11

In the long-run, a large fraction of capit al gains arises fr om the fact that corporations retain part of their

earning, which leads to share price appreciation. Since retained earnings are part of national income, these

capital gains are in effect included in our series on an accrual basis. In the short run, however, most capital

gains are pure asset price effects. Thes e short-term capital gains are ex cl u de d from national income and from

our series.

12

A number of studies have tried to reconci l e totals from the national accounts and totals fr om household

surveys or tax data; see, e.g., Fesseau, Wolff and Mattonetti ( 2012) and Fesseau and Mattonetti (2013). Such

comparisons have long bee n conducted at nation al levels (for example, Atkinson and Micklewright, 1983, for

the UK) and th er e have been earlier cross country comparisons (for example in the OECD report by Atkinson,

Rainwater , and Smeeding, 1995, Section 3.6).

8

both the levels and growth rates of U.S. incomes. They particularly under-estimate growth for

the middle-class, as we shall see.

3.2 Pre-tax Income and and Post -ta x Income

At the individual level, income differs whether it is observed before or after the operation of th e

pension system and government redistribution. We therefor e define three inco m e concepts that

all add up to national income: pre-tax factor income, pr e-t a x national income, and post-t ax

national income. The key difference between pre-tax factor income and pre-tax nati on a l income

is the treatment of pensions, which are counted on a contribution basis for pre-tax factor income

and on a distribution basis for pre-tax national income. Post-tax nation a l income deducts all

taxes and adds back all publ i c spend i n g, including publi c goods consu m p t i on . By con st r u ct i on ,

average pre-tax facto r income, pre-tax national income, and post-tax national incom e are all the

same in our benchmark series (and equal to average nati o n al income), which makes comp ar i n g

growth rates straightforward.

Pre-tax factor income Pre-tax factor income (or more simply factor income) is equal to

the sum of all the income flows accruing to the individual owners of the factors of p r oduction,

labor and capital, before taking into accou nt the operation of pensions and the tax and transfer

system. Pension benefits are not included in factor income, nor is any form of private or public

transfer. Fact or income is also gross of all taxes and all contrib u t i o n s, including contri b u t i ons

to private pensions and Soci al Security. One problem with this con ce p t of income is that retired

individuals typically have littl e factor income, so that the inequality of facto r income tends to

rise mechanically with the fraction of old-age individuals in the popu l a ti o n , potentially bi as i n g

comparisons over time a n d across countries. Look i n g at the distribution of factor incomes can

however yield certain i n si ghts, especially if we restrict the analysis to the working-age popula ti o n .

For instance, it al l ows to measure the distribution of labor costs paid by empl oyers.

Pre-tax national income Pre-tax national income (or more sim p l y pre-tax income) is our

benchma rk concept to stu d y the distribution of income before government intervention. Pre-

tax income is equal to th e sum of all income flows going to labor and capital, after taking into

account the operation of private and public pensions, as well as disab i l i ty and unemployment

insurance, but before taking into account other taxes and transfers. That is, the only difference

with factor income is that we deduct the contributions to private an d public pensions includ i n g

Social Security—old age, survivors and disability—and unemployment insurance from incomes,

9

and add back the corresponding benefits.

13

Pre-tax income is broader but co n cep t u a l l y similar

to what the IRS attempts to tax, as pensions, S oci a l Security, and unemployment benefits are

largely taxable, while contributions are largely tax deductible.

14

Post-tax national income Post-tax nationa l income (or more simply post-tax income)

is equal to pre-tax income after subtracting all ta xes and adding all forms of government

spending—cash transfers, in-kind transfers, and collective con su m p t i on expenditures.

15

It is

the income that is available for saving and for the consumption of private and p u b l i c goods.

One advantage of allocati n g all forms of government spending to individual s—a n d not just cash

transfers—is that it ensures that post-tax income adds up to national income, just like factor

income and pre-tax income.

16

It can be useful, however, to focus on post-tax income including

cash transfer s transfers only—for instan ce to study the distribution of private co n su m p t i on .

We therefore define post-tax dispos abl e income as pre-tax national income minus all taxes plus

monetary transfers only. Post-tax disposable income does not add up t o national income but is

easier to measure than post-tax national income, bec au se it does not require allocatin g in-kind

transfers and collective consumption expenditure across the distribution.

Our objective is to construct the distrib u t i on of factor income, pre-tax income, a n d post-tax

income. To do so, we match tax data to survey data and make explicit assumptions about the

distribution of income categories for which there is no available source of informat i o n . We start

by describing how we move from fiscal income to total pre-tax income, before describ i n g how

we deal with taxes and tran s fer s to obtain post-tax income.

3.3 From Fiscal Income to Pre-Tax National Income

The starting point of our distribu t i on a l na t i on a l accou nts is the fiscal income reported by tax-

payers to the IRS on individual income tax returns. The main data source, for the post-1962

13

Cont r ib u t ion s to pensions include the capital income earned and reinvested in tax-exempt pension plans

and accounts. On aggregate, contributions to private pensions largely exceed distributions i n the United States,

while contributions to Social Security have been smaller than Social Security disbursements in re ce nt years

(see Appendix Table I-A10). To match national income, we add back the surplus or deficit to individu als ,

proportionally to wage income for private pensions, and proportionally to taxes paid and benefits received for

Social Security (as we do for the government deficit when computing post-tax income, see below).

14

Social Security benefits were fully tax exempt before 1984 (as well as unemployment benefits before 1979).

15

Social S ecu r i ty and unemployment insurance taxes were already subtracted in pre-tax income and the

corresponding benefits added in pre-tax income, so they do not need to be subtracted and added again when

going from pre-tax to post-tax income.

16

Government spending typically exceeds government revenue. I n order to match national income, we add

back to individuals the government deficit proportionally to taxes paid and benefit s received; see Section 3.4

below.

10

period, is the set of annual public-use micro-files created by the Statistics of Income division

of the IRS and available through the NBER that provide i n fo r m at i o n for a lar g e sample of

taxpayers with detailed income categories. We supplem ent this dataset using the internal use

Statistics of Income (SOI) Individual Tax Return Sample files from 1979 onward.

17

For the

pre-1962 period, no micro-files are available so we rely instead on the Piketty and Saez (2003 )

series of top in com es which were const r u ct ed from annual tabulations of income and its com-

position by si ze of income (U.S. Trea su r y Department , Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of

Income, 1916-present). Tax data contain information about most of the components of pre-

tax income, including private pension distrib u t i on s— th e vast majority of which are taxable—,

Social Security benefits (taxable since 1984), and unemployment compensation (taxable since

1979). However, they miss a growing fr act i o n of labor income and about two-thirds of economic

capital income.

Non-filers To sup p l em ent tax data, we start by adding synthetic observations rep r esenting

non-filing tax un i t s using the Current Population Survey (CPS). We identify non-filers in the

CPS based on their taxable income , and weight these observations such that the total number

of ad u l t s in our final dataset matches the total number of adults living in the United States, for

both the working-age population (aged 20-65) and the elderly.

18

Tax-exempt labor income To capture total pre-tax labor income i n the economy, we pro-

ceed as follows. First, we compute employer payroll taxes by applying the statutory tax rate

in each year. Second, we allocate non - t ax a b l e health and pension fringe benefits to individual

workers using i n fo r m ati o n reported in the CPS.

19

Fringe benefits have been r eported to the

17

SOI maintains high quality individual tax sample data since 1979 and population-wide data s in ce 1996. All

the estimates using internal data presented in this paper are gathered in Saez (2016). Saez (2016) uses intern al

data statisti cs to supplement the public use files with tabulat ed information on age, gender , earnings split for

joint filers, and non-fil er s characteristics which are used in this study.

18

The I RS receives information returns that also allow to estimate the income of non-filers. Saez (2016)

computes detailed statistics for non-filers using IRS data for the period 1999-2014. We have used these statistics

to adjust our CPS-based non-filers. Social security benefits, the major income category for non-filers, is very

similar in both CPS and IRS data and does not need adjustment. However, there are more wage earners and

more wage income per wage earner in the IRS non-filers statistics (perhaps due to the facts that very small

wage earners may report zero wage income in CPS). We adjust our CPS non-filers to match the IRS non-filers

char act e ri s ti c s; see Appendix Section B.1.

19

More precisely, we use the CPS to estimate the probability to be covered by a retirement or health plan in

40 wage bins (decile of the wage dist ri b ut i on × marital status × above or below 65 years old), and we impute

coverage at the micr o-l e vel using these es t i mat ed probabilities. For health, we then impute fixed benefits by

bin, as estimated from the CPS and adjusted to match the macroeconomic total of employer-provided health

benefits. For p en si ons , we assume that the contributions of pension plans participants are proportional to wages

winsorized at the 99th percent il e .

11

IRS on W2 forms in recent years—employee contributions to defined contribution plans since

1999, and health insurance since 2013 . We have che cked that our imputed pension benefits are

consistent with the high quality information reported on W2s.

20

They are also consistent with

the results of Pierce (2001), who studies non-wage compensat i on using a different dataset, the

employm e nt cost i n d ex micro-data. Like Pierce (2001) , we find that the changing dist r i b u t i on

of non-wage benefits has slightly reinforced the rise of wage inequ a l i ty.

21

Tax-exempt capital income To ca p t u r e total pre- t ax capital income in the economy, we first

distribute the total amount of household wealth r eco r d ed in the Financial Accounts following

the methodology of Saez and Zucman (2016). That is, we capitalize the interest, d i v i d en d s

and realized capital gains, rents, and business profits reported to the IRS to capture fixed-

income claim s, equ i t i es , tenant-occupied housing, and business assets. For itemizers, we impute

main homes and mortgage debt by capitalizin g property taxes and mo r tg a ge interest paid. We

impute all forms of wealth that do not generate repo rt a b l e income or deductions—currency,

non-mortgage debt, pensions, mun i ci p al bonds before 1986, a n d homes and mortgages for non-

itemizers—using the Survey of Consumer Finances.

22

Next, for each asset class we compute

a macroeconomic yield by dividing th e total flow of capital income by the total value of the

corresponding a sset . For instance, the yield on corporate equities is the flow of corporate

profits—distributed and retained—accruin g to U.S. reside nts di v i d ed by the market value of

U.S.-own ed equ i t i es. Last, we multiply indi v i d u al wealth components by the correspo n d i n g

yield. By construction, th i s procedure ensu r es that indiv i d u a l capital inc om e adds up to total

capital income in the economy. In effect, it blows up dividends and capital gains observed in

tax data in order to match the macro flow of corporate p r o fi t s including retained earnings—and

similarly for other asset classes.

Is i t reasonable to assume that retained earnings are distributed like dividends and realized

capital gains? The wealt hy might invest in compan i es that do not distribute di v i d en d s to

avoid the dividend tax, and they might never sell their shares to avoid the capital gains tax,

in which case retained earnings would be more concentrated than dividends and capital gains.

Income tax avoidance might also have changed over time as t o p dividend tax rates rose and

20

The Statistics of Income divis i on of the IRS produces valuable statistics on pension contributions reported

on W2 wage inc ome forms. In the future, our imputations could be refi n ed using individual level information

on pensions (and now health insurance as well) available on W2 wage income tax forms.

21

In our estimates, the share of total non-wage compensation earned by bottom 50% income earners has

declined from about 25% in 1970 to about 16% today, while the share of taxable wages earn ed by bottom 50%

income earners has fall en from 25% to 17%, see Appendix Table II-B15.

22

For complet e methodological details, see Sae z and Zucman (2016).

12

fell, biasi n g th e tren d s in our in eq u a l i ty series. We have investigated this issue careful l y an d

found no evidence that such avoidance behavior is quantitat i vely significant—even in periods

when top dividend tax rates were very high. Since 1995, there is comprehensive evidence from

matched estates-income tax returns that taxab l e rates of r et u r n on equity are similar across the

wealth distribution, suggesting tha t equities (hence retained earnings) ar e distributed similarly

to dividends and capital gains (Saez and Zucman 2016, Figure V). This also was true in the

1970s when top divi d en d tax rates were much higher. Exploi t i n g a publicl y available sample of

matched estates-income tax returns for people who died in 1976, Saez and Zucman (2016) find

that despi te facing a 70% top marginal inco m e tax rate, individuals in th e top 0.1% and top

0.01% of the wealth distribution had a high dividend yi el d (4.7%), almost as lar ge as the average

dividend yield of 5.1%. Even then , wealthy peop l e were unable or unwilling to disproportionally

invest in non-divid en d paying equities. These results suggest that allocat i n g retained earnings

proportionally to equity wea l t h is a reasonable ben chmark.

Tax incidence assumptions Computing pre-tax income requires making tax incidence as-

sumptions. Should the corporate tax, for instance, be fully added to corporate profit s, hence

allocated to shareholders? As is well known, the burden of a tax is not necessarily borne by

whoever nominally pays i t. Behavioral responses t o taxes can affect the relative price of factors

of production, thereby shifting the tax b u r d en from one factor to t h e other; taxes also genera t e

deadweig ht losse s (see Fullerton and Metcalf, 2002 for a survey). In this paper, we do not

attempt to measure th e complete effects of t axes on econ omi c behavior and the money- m et r i c

welfare of each individual. Rather, and perhaps as a reasonable first approximation, we make

the following simple assumptions regarding tax incidence.

23

First, we assume that taxes neither affect the overall level of national income nor its distri-

bution across labor a n d capital. Of course this is unli kely t o be true. An alternative stra t eg y

would be to make explicit assumptions about the elasticit i es of supply and demand for labor

and capital, so as to estimate what would be the counterfactual level of output and income

if the tax sy st em did not exist (one would also need to model how public infrastructures are

paid for, and how they contribute to the production functi on ) . This is beyond the scope of

the present paper and is left for future work. We prefer to adopt a more modest objective:

we s i m p l y assume that pre-tax and p o st -ta x income both add up to the same national income

total, and that taxes on capital are borne by capital only, while taxes on labor are borne by

23

For a detailed discussion of ou r tax incidence assumptions, see the Online Appendix Section B.4.

13

labor o n l y. In a standard tax inci d en ce model, th i s is indeed the case whene ver the elasticity e

L

of labor supply with r espect to the net-of-tax wage rate and the elastici ty e

K

of capital supply

with respect to the net-of-tax rate of return are small r el a t i ve t o the elasticity of substitution σ

between capital and labo r .

24

This implies, for instance, that payr o l l taxes are entirely paid by

workers, irrespective of whether they are nominally paid by employers or employees.

Second, within the capital sector , and consistent with the seminal analysis of Harberger

(1962), we allow for the cor porate tax to be shifted to forms of capital other than equitie s.

25

We di ffer from Harberger ’ s analy si s only in that we treat residential real estate separately.

Because the residential real estate m arket does not seem perfectly integrated with finan ci a l

markets, it seems more reasonable to assume that corporate taxes are borne by all capital

except residential real estate. We symmetrical l y assume that residential property taxes only fall

on residential real estate. Last, we assume that sales and excise taxes are paid proportionally

to factor income minus saving.

26

We have also tested a numbe r of alternative tax incidence

assumptions, and found only second-order effects on the level and time pattern of our pre-tax

income series .

27

Our incid en ce assumptions are broadly similar to the assump t i on s made by

the US Congressional Budget Office (2016) which produces di st r i b u t i on a l sta ti s ti c s for Fed er a l

taxes only.

28

Our micro-files are con st r u ct ed in such a way that users can make alternative

tax incidence assumptions. These assumptions might b e i m p r oved as we learn more abou t the

economic incidence of taxes. It is also worth noting that our tax incidence assumptions only

matter for the d i s tr i b u t i o n of pre-tax income—th ey do not matter for post-tax series, which by

definition subtract all taxes.

24

However whenever sup p ly effect s cann ot be neglected, the aggregate level of domestic output and national

income will be affected by the tax system, and all taxes will be partly shifted to both labor and capital.

25

Harberger (1962) shows t hat un d er reasonable assumptions, cap i t al bears exactly 100 percent of the cor porate

tax but that the tax is shifted t o all forms of capital.

26

In effect, this assumes that sales taxes are shifted to prices rather than t o the factors of production so

that they are borne by consumers. In practice, assumptions about the incidence of sales taxes make very little

difference to the level and trend of our income shares, as sales taxes are not very important in the Unite d Stat es

and have been constant to 5%-6% of national income since the 1930s; see Appendix Table I-S.A12b.

27

For instance, we tried allocating the corporate t ax to all capital assets including housing; allocating residential

property taxes to all capital assets; allocating consumption taxes proportionally to income (instead of income

minus savings). Non e of this made any significant difference.

28

CBO assumes t h at corporate taxes fall 75% on all forms of capital and 25% on labor income. Because U.S.

mul t i nat i on al firms can fairly easily avoid US taxe s by shifting profits to offshore tax havens without having to

chan ge t h ei r actual production decisi on s ( e. g. , through the manipulation of transfer prices), it does not seem

plausible to us that a significant share of the US corporate tax is borne by labor (see Zucman, 2014). By contrast,

in small countries—where firms’ l ocation decisions may be more elastic—or in countries that tax capital at the

source but do not allow firms to easily avoid taxes by artificially shifting profits offshore, it is likely that a more

sizable fraction of cor porate taxes fall on labor.

14

3.4 From Pre-Tax Income to Post-Tax Income

To move from pre-tax to post-tax inco m e, we deduct all taxes and add back all government

spending. We incorporate all levels of government (federal, state, and local) in our analysis of

taxes and government spending, which we decompose into monetary transfers, in-kin d transfers,

and collect i ve consumption expenditure. Using our micro-files, it is p o ssi b l e to separate federal

from state and local taxes and spending.

Monetary social transfers. We impute all monetar y social transfers d i r ectl y to recipients.

The main monetary transfers are the earne d income tax credit, the aid for families with de-

pendent children (which became the t em porary aid to needy famili es in 1996), food stamps,

29

and supplementary security income. Together, they make about 2.5% of n at i o n al income, see

Appendix Table I-S.A11. (Remember that Social security pensions, unemployment insu r a n ce,

and disability benefits, which together make about 6% of national i n com e , are already included

in pre–tax in co me) . We imp u t e monetary transfers to their beneficiaries based on rules and

CPS data.

In-kind social transfers. In-kind social tra n sfe rs are all transfers that are not mon et a r y (or

quasi-monetary) but are individualized, that is, go to specific beneficiaries. In-k i n d transfers

amount to about 8% of nationa l income today. Almost all in-kind t r an sf er s in the United

States correspond to health benefits, primarily Medicare and Medicaid. Beneficiaries are again

imputed based on rules (such as all persons aged 65 and above or persons receiving disability

insurance for Medicare) or based on CPS data (for Medicaid). Medicare and Medicaid benefits

are imputed as a fixed amount per beneficiary at cost value.

Collective expenditure (public goods consumption). We allocate collective consump-

tion ex penditure proportionall y to post-tax disposa b l e income. Given that we know relatively

little about wh o benefits from spending on defense, police, the justice system , infrastructure,

and the like, this seems like the most reasonable ben chmark t o sta r t wi th . It has the advantage

of being neutral: our post-tax income sha re s are not affected by the allocation of public good s

consumption. There are of course other possi b l e ways of allocating public g ood s . The two polar

cases would be distributing public goods equally (fixed amount p er adult), and proportionally

29

Food stamps (renamed supplementary nutrition assistance pr ogr ams as of 2008) is not a monetary transfer

strictly speaking as it must be used to buy food but it is almost equivalent to cash in practice as food exp e nd it ur es

exceed benefits for most families (see Currie, 2003 for a survey).

15

to weal t h (which might be justifiabl e for some types o f public goods, such as police and defense

spending). An equal allocation would increase the level of income at the bottom, but wou l d not

increase its growth, because pu b l i c goods spending has been constant around 18% of n a t i on a l

income since the end of World War II. Our tr ea t m ent of public goods could easil y be im p r oved

as we learn more about who benefits from them.

In our benchmark series, we also allocate pub l i c education co n su m p t i o n expenditure pro-

portionally to post-tax disposable income.

30

This can be justified from a lifetime per spective

where everybody benefits from education and where higher earners attended better schools and

for longer. In the Online Appendix Sect i on B. 5. 2 , we propose a polar alternative where we con-

sider the current parents’ perspective and attribute education spending as a fix lump sum per

child.

31

This slightly increases the level of bottom 50% post-tax incomes but without affecting

the trend.

32

Government deficit Government revenue usually does not add u p to total government ex-

penditure. To match national income, we impute the primary government deficit to individuals.

We alloca t e 50% of the deficit proportionall y to taxes paid, and 50% p r oportionally to bene-

fits received. This effectively assumes that any government defici t will translate into increased

taxes and reduced government spending 50/50. The imputation of the deficit does not affec t

the distribut i on of in c om e much, as taxes and government spending are both p r o gr es si ve, so

that increasing taxes and reducing government spending by the same amount has little net dis-

tributional effect. However, imputin g the deficit affects real growth, especiall y when the deficit

is large. In 2009-2011, the government deficit was aro u n d 10% of national income, abo u t 7

points higher than usual. The growth of post-tax incomes would have been much stronger in

the aftermath of th e Great Recession had we not allocated the defi ci t back to individuals.

33

30

That is, we treat government spending on education as government spending on other pu bl i c goods such as

defense and police. Note that in the Sy st em of National Accounts, public education consumption expenditure are

included in individual consumpti on expenditure (together with public health spending) rather than in c ol le ct i ve

consumption expenditure.

31

For married couples, we attribute each child 50/50 to each parent. Note that children going to college and

supported by parents are typically claimed as dependents so that our lump-sum measure gives more income to

families supporting children thr ou gh college.

32

See Appendix Figure S.23.

33

Int er es t income paid on government debt is included in individ ual pre-tax income but is not part of national

income (as it is a transfer from government to debt holders). Hence we also de du ct inter es t income paid by the

government to US residents in proportion to taxes paid and benefits received (50/50).

16

4 The Distributi on of National Income

We st ar t the analysis with a description of the levels and trends in pre-tax income and post-tax

income across the di st r i b u t i on . The unit of obser vation is the adult, i.e., the U.S. resident age d

20 and over.

34

We use 20 years old as the age cut-off—instead of the official majority age,

18—as many young adults still depend on their parents. Throughout this section, the income

of marri ed couples is split equ al l y between spouses. We will analyze how assigning each spouse

her or his own l abor in com e affects the results in Section 5.1.

4.1 The Distribution of Pre-Tax and Post-Tax Income in 2014

To get a sense of the distribution of pre-tax and post-tax national in co m e in 2014, consider first

in Table 1. Average income per adult in the United States is equal t o $64,600—by definition, for

the ful l adult population, p r e- t ax and post-tax average nation a l incomes are the same. But this

average masks a great deal of heterogeneity. The bottom 50% adults ( m or e than 117 mi l l i on

individuals) earn on average $16,200 a year before taxes and transfers, i.e., about a fourth of the

average income economy wide. Accordingly, the bottom 50% receives 12.5% (a fourth of 50%)

of total national pre-tax income. The “middle 40% ”—the group of adults with income be tween

the median and the 90th percentile that can be described as the middle class—has roughly the

same average pre-tax income as the economy-wide average. That is, the pre-tax income share

of the mi d d l e 40% is close to 40%. The top 10% earns 47% of total pre-tax income, i.e., 4.7

times the average income. There is thus a ratio of 1 to 20 between average pre-tax income in

the top 10% and in the bottom 50%. For context , this is much more than the ratio of 1 to 8

between average income in the United States and average income in China—about $7,750 per

adult in 2013 using market exchange rates to convert yuans into dollars.

35

Moving further up

the income distribution, the top 1% earns abou t a fifth of total national income (20 times the

34

We i n cl ud e the institutionalized population in our base population. This includes prison inmates (about

1% of adult population in the US), population living in old age institutions and mental institutions (about

0.6% of adult populat i on) , and the homeless. The instit u t i onal i ze d population is generally not covered by

surveys. Furlong (2014) and Fixler et al. (2015) remove the income of ins ti t u t ion al i zed households from the

national account aggregates to construct their distributional series. We prefer to take everybody into account

and allocate zero incomes to institutionalized adults when they h ave no inc ome. Such adults file tax returns

when they earn income.

35

All our results in this paper use the same national income price index across the US income distribution

to compute real income, disregar di n g any potenti al differences in prices across groups. Using our micr o-fi le s, it

woul d be straightforward to use different price index es for different groups. This might be desirable to study the

inequality of consumption or standards of living, which is not the focus of the current paper. Should one deflate

income differently across the distribution, then one should also use PPP-adjusted exchan ge rates to compare

average US and Chinese income, r ed u ci ng the gap between the two countries to a ratio of approximately 1 to 5

(instead of 1 to 8 using market price exchan ge rates).

17

average income) and the top 0.1% close to 10% (100 times the average income, or 400 times the

average bottom 50% income). The top 0.1% income share is close to the bottom 50% sh ar e.

Post-tax nation a l incom e is more equally distri b u te d than pre-ta x incom e: the t a x and

transfer syst em is progressive overall. Transfers play a key role for the bottom 50%, where

post-tax national income ($25,000) is over 50% higher than pre-tax national income. This

is, however, entirely due to in-ki n d transfers and collective expenditures: post-tax disposable

income—including cash transfers but excluding in-kind transfers or public goods—is onl y slightly

larger than pre-tax nation a l income for the bott om 50%. That is, th e bottom 5 0 % pays roughly

as much in taxes as what it receives in cash transfers; it does not benefit on net from cash

redistribution. While the bottom 50% earns a bo u t 40% of the average post-tax inc om e, the

top 10% earns cl o se to 4 times the average post-tax income (i.e., the top 10% post-tax share

is 39%). After taxes and transfers, ther e i s thus a ratio of 1 to 10 between the average income

of the top 10% and of bottom 50%—still a larger difference than the ratio of 1 to 8 between

average national income in the United States and in China. Taxes and government spending

reduce top 10% incomes by about 17 % , top 1% incomes by 23%, and top 0.1%, top 0.01%, and

top 0 . 00 1% incomes by abo u t 27%. Taken together, government taxes and transfers are overall

slightl y progressive at the top.

In Appendix Table S.7, we also report the distr i b u t i on of factor in co m e, that is, income

before any tax, transfer, and before the operation of the pension system. Unsurpri s i n gl y, since

most re ti r ee s have close to zero factor income, the bottom 50% factor income share is lower

than the bot t o m 50% pre-tax income sh a re , by abou t two points. Th e average factor in co m e of

bottom 50% earners i s $13,300 in 2014, significantly less than their average post-tax dispo sa b l e

income. That is, if one uses facto r income as the benchmark series for the distributio n of

income befor e government intervent i on , then the bottom 50% appear s as a net beneficiary of

cash redistri b u ti o n . For the top 10% and above, factor income and pre-tax income are almost

identi ca l as social security and pensions are a very small fract i on of income at the top.

4.2 Long-Run Trends in the Distribution of Income and Growth

There have been considerable lon g-r u n chan ges in income inequality in the United States over

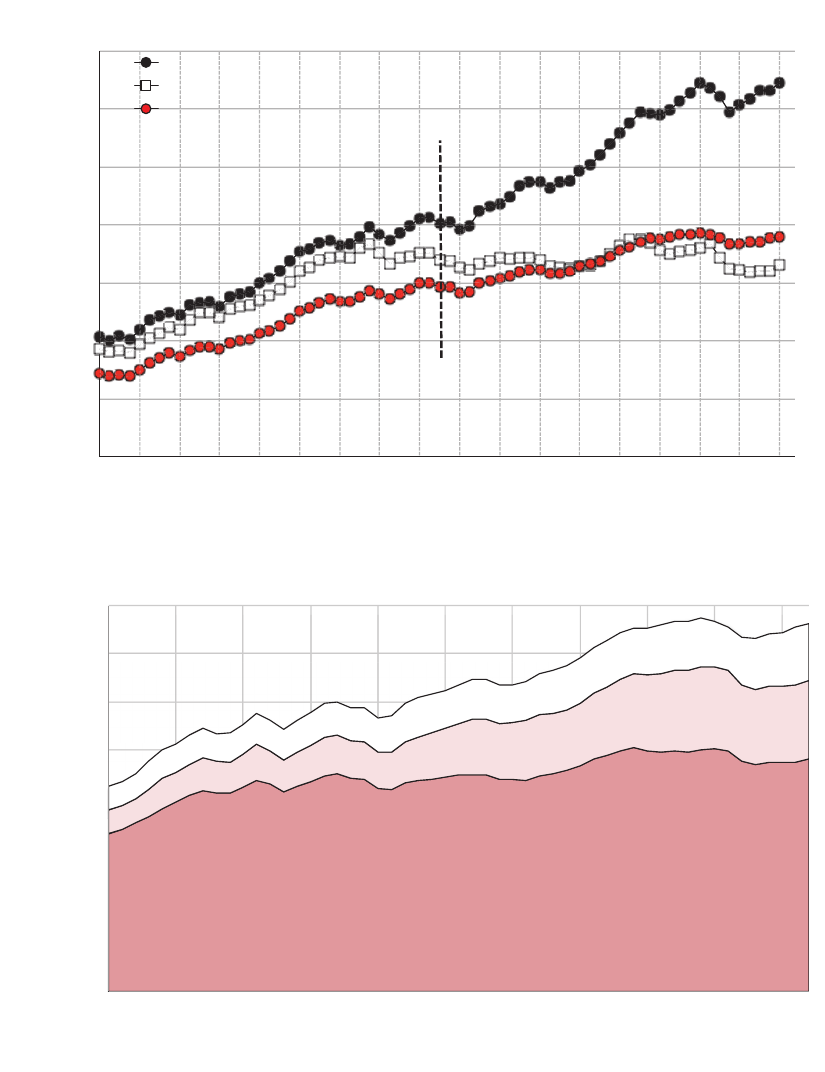

a century. Figure 2 displays the share of pre-tax and post-tax inco m e going to the top 10%

and top 1% adults. Top pre-tax income shar es fell in the first half of the twentiet h century

and have been rising rap i d l y since the early 1980s. Pre-tax top income shares are a l m os t at the

same level today as they were at their peak in the late 1920s just before the Great Depress i on .

18

The U-shaped evolution over the last century is similar to the one seen in fiscal income series

(Piketty and Saez, 2003), although there are differences, as we explain in Section 6 where we

reconcile our findings with other estimates of US income inequality.

Top post-tax income shares have also followed a U-shaped evol u t i o n over time, but exhibit

a less marked upward swing in recent decades. In particular, they have not return ed to their

level of a century ago. Early in the twentieth century, when the government was sma l l an d

taxes low, post-tax and pre-tax top incomes were similar . Pre-tax and post-tax shares started

divergi n g during the New Deal for the top 1% and World Wa r II for the top 10%—when federal

income taxes increased significantly for that group as a whole. And although post-tax inequality

has incr ea sed significantly since 1980, it has risen less than pre-tax inequality. Between 1980

and 2014, the top 10% income share rose by about 10 points post-tax and 13 points pre-tax.

As a result of the si g n i fi ca nt 2013 tax increases at the top, post-t a x top income shares have

increased less than pre-tax income shares in very recent years. Overall, redistributive polici es

have p r evented post-tax inequality from returning all the way to pre-New Deal levels.

Table 2 decom po ses growth by income groups since World War II in two 34 year long sub-

periods. From 1946 to 1980, real macroeconomic growth per adult was strong (+95%) and

equally distributed—in fa ct , it was slightly equalizing, as bo t to m 90% grew faster than top

10% incomes.

36

In the next 34 years period, from 1980 to 2014, aggregat e growth slowed down

(+61%) and became extremely uneven. Looking first at income before taxes and trans fer s,

income stagnated for bottom 50% earners: for this group , average pre-tax income was $16, 00 0

in 1980—expressed in 20 1 4 dollars, u si n g the national income deflator—and still is $16,200 in

2014. Growth for the mi d d l e 40% was weak, with a pre-tax incr eas e of 42% since 1980 (0.8% a

year). At th e top, by contrast, average income mo r e than doubled for the top 10%; it tripled for

the top 1%. The further one moves up the ladder, the high e r the growth rates, culminating in an

increase of 636% for the top 0.001%—ten times the macroeconomic growth rate. Such sharpl y

divergent growth experiences over decades hi g h l i g ht the need for growth statistics disaggregated

by income groups.

Government redistribution made growth more equitable, but only slightly so. After taxes

and transfers, the bottom 50% only grew +21% since 1 98 0 (0.6% a year). That is, transfers

erased about a third of the gap between macr oeconomic growth (+60%) and growth at th e

bottom (0% before government intervention). Taxes did not hamper the u p s u rg e of income at

the top: after taxes and transfers the top 1% nearly doubled, the top 0.1% nearly tripled, the

36

Very top incomes, however, grew more in post-tax terms then in pre-t ax terms between 1946 and 1980,

because the tax system was more progressive at the very top in 1946.

19

top 0.001% grew 617% , almost as much as pre-tax.

4.3 The Stagnation of Bottom 50% Average Income

Perhaps the most striking develo p m ent in the U.S. ec on o my over the last decades is the stagna-

tion of income in the bottom 50%. This evolution therefore deserves a careful analysis.

37

The

top panel of Fi gu r e 3 shows how the pre-tax and post-tax income shares of the botto m 50%

have evolved since the 1960s. The p r e-t a x share increased in the 19 60s as the wage d i st r i b u t i on

became more equal—the real federal minimum wage rose significantly in th e 1960s and reached

its historical ma x i mum in 1969. The pre-tax share th e n declined from about 21% in the 1969

down to 12.5% in 2014. The post - ta x share initially increased more then the pre-tax share

followin g President Johnson’s “war on poverty”—the Food Stamp Act was passed in 1965; aid

to families with dependent children increased in the second half of the 1960s, Medi ca i d was

created in 1965 . It then fell along with th e pre-tax income share. The gap between the pre-

and p ost - ta x share of income ea rn e d by the bottom 50% incr ea sed over time. This is not due

to the growth of Social Security benefits—because pre-tax income includes pension and social

security benefi t s—b u t owes to the rise of transfers other than Social Security, chiefly Medicaid

and Medicare. In fact, as shown by the bottom panel of Figure 3, almost all of the meager

growth in real bottom 50% post-tax income since the 1970s comes from Medicare and Medi-

caid. Excluding those two transfers, average bottom 50% post-tax income would have stagnated

around $20,000 since the late 1970s. The bottom half of the adult population has thus been

shut off from econom i c growth fo r over 40 years, and the paltry increase in their disposable

income has been absorbed by increased health spending.

The growth in Medicare and Medicaid transfers reflects an increase in the generosity of the

benefits, but also the rise in the price of health serv i ce s provided by Medicare and Medi cai d —

possibly above what people would be willing to pay on a private market (see, e.g. , Finkel-

stein, Hendren, and Luttmer 20 16 )— an d perh ap s an increase in the econom i c surplus of health

provid er s in the medical a n d pharmaceutical sectors. To put in perspecti ve the average annual

health trans fer of about $5,000 received by bottom 50% individuals, note that it represent s the

equivalent of less than a week of the average pre-tax income of top 10% individuals (about

$300,000) and a bit more than a day of the average pre-tax income of top 1% individual s ($1.3

37

There is a large literature documenting the stagnation of low-skill wage earnings (see, e.g., Katz and Autor,

1999). The US Census bureau (2016) official statistics also show very little growt h of median family income in

recent decades. Our value added is to include all national income accruing to the bottom 50% adults, to contrast

pre-tax and post-tax incomes, and to be able to compare the bottom to the top of the distribu t ion in a single

dataset representative of th e US population.

20

million). Concretely, the in-kind health redistribu ti o n received by botto m 50% individuals is

equivalent to about one week of attention provided by an average top-decile health provider, or

one day of attention provided by an average top-percentile health provider.

Figure 3 also di sp l ays the average post-tax disposable income of bottom bottom 50 % earners—

including cash transfers but excluding in-kind transfers and collecti ve consumption expen d i -

tures. For the bottom half of the distribution, post-tax disposabl e income has stagnated at

about $15,000–$17,000 since 19 8 0. This is about the same level as average bottom 50% pre-tax

income. In other words, it is solely through in-kind health transfers and collective expenditure

that the bottom half of the distribution s ees it s in co m e ri se a bove i t s pr e-t a x l evel and beco m es

a net beneficiary of redistribution. In fact, until 2008 the bottom 50% paid more in taxes than

it received in cash transfers. The post-tax disposable in co m e of bottom 50% adults was lifted

by the large government deficits run during the Great Recession: Post-tax disposable income

fell much less than post-tax income—which imputes the deficit back to individuals as negative

income—in 2007-2010.

From a purely logical standpoint, t h e sta gn a t i on o f bottom 50% income might reflect d em o -

graphic cha n g es ra th e r tha n d eeper evolutions in the distribution of li fet i m e in c om es. People’s

incomes tend to first rise with age—as workers build human capital and acquire experience—an d

then fall during retirement, so population aging may have pushed the bottom 50% income share

down. It would be interesting to estimate how the bottom 50% lifet i m e in c om e has changed

for different cohorts.

38

Existing estimates suggest that mob i l i ty in earnings did not increase

in the lo n g- ru n (see Kopczuk, Saez, and Song, 2010 for an analysis using Socia l Security wage

income data), so it seems unlikely that the increase in cross-sectional in co m e inequality—an d

the colla p se in the bottom 50% income shar e—co u l d be offset by rising lifetime mobility out of

the bot t o m 50%.

To shed more light on this issue, we have computed the evolution of bottom 50% incomes

within different age gro u p s separately.

39

For the working-age population, as shown by the top

panel of Figure 4, t h e average botto m 50% income rises with age, from $13,000 for adults aged

20-44 to $23,000 for adults aged 45-65 in 2014—st i l l a very low level. But the most striking

finding is that among worki n g- ag e adults, average bottom 50% pre-tax income has collapsed

since 1980: -20% for adults aged 20-45 and -8% for those between 45 and 65 years o l d . It is only

38

In our view, both the annual and lifetime perspective are valuable. This paper focuses on the annual

persp e ct i ve. It captures cross-sectional inequality, which is particularly relevant for lower income groups that

have l im i te d ability to smooth fluctuations in income through saving. Constructing life-time inequality series is

left for future re sear ch.

39

We can do this decomposition by age star t i ng in 1979 when age data become available in internal tax data.

21

for the elderly that pre-tax income has been rising, because of the increase in Social Security

benefits and private pensions distributions. Americans aged above 65 and in the bott o m 50%

of that age group now have the same average income as all bottom 50% adults—about $16,000

in 2014—whi l e they earned much less in 1980.

40

After taxes and transfers, as shown by the

bottom panel of Figure 4, the average income of bottom 50% seniors now exceeds t h e average

bottom 50% income in the full population and has grown 70 % since 1980. In fact, all the

growth in post-tax bottom 50% income owes to the increase in income for the elderly.

41

For the

working -a ge population, post-tax botto m 50% income has hardly increased at all since 1980 .

We reach the same conclusion when we look at the average pos t-t ax disposabl e income of the

bottom 50% adults aged 20 to 45: it has stagnated at very low levels—around 15,000$ .

There are thr ee main lessons. First, since income has coll ap se d for the bottom 50% of all

working -a ge groups—including experienced workers above 45 years old—it is unlikely that the

bottom 50% of lifetime income has grown much since the 1980s. Second, the stagnation of the

bottom 50 % is not due to population aging—quite t h e contrary: it is onl y the income o f the

elderly which is r i si n g at the bo t to m . For the bottom half of the working-age po p u l at i o n , average

income befo r e government intervention has fallen since 19 80 —t h i s is true whether one looks at

pre-tax income (including Social Security benefits) or factor income (excluding Social Secur i ty

benefits).

42

Third, despite the rise in m ean s -t est ed benefits—includi n g Medicaid and the Earned

Income Tax Credit, created in 1975 and expanded in 1986 and the early 1990s—government

redistribution has not enhanced income growth for low- an d moderate income wor k i n g- ag e

Americans over the last three decades. There are clear limits to what taxes and transfers can

achieve in the face of such massive changes in the pre-tax distribution of income li ke those that

have occurred since 1980. In our view, the main conclusion is that the policy discussion sh o u l d

focus on h ow to equalize the distribution o f primary assets, including human capital, financial

capital, and bargaining power, rather than merely ex-post redistribution.

The stagnation of income for th e bottom 50% contrasts sharply with the up su r g e of th e top

40

The vast majority—about 80% today—of the pre-tax i n come for bottom 50% elderl y Americans is pension

benefits. Howeve r, the income from salaried work has been growing over time and now accounts for about 12%

of the pre-tax income of poor elderly Americans (close to $2,000 on average out of $16,000); the r es t is accounted

for by a small c apit al income residual. See Appendix Table II-B7c.

41

In turn, most of the growth of the post-tax income of bot t om 50% elderly Americans has been due to

the rise of health benefits. Without Medicare and Medicaid (which covers nursing home costs for poor elderly

Americans), average post-tax income for the bottom 50% seni ors would have stagn at ed at $20,000 since the early

2000s, and would have increased only modestly since the early 1980s when it was around $15,000; see Appendix

Table II-C7c and Appendix Figure S.5.

42

More broadly, for the working-age p opu l at ion , growth is nearly identical whether one looks at factor income

or pre-tax income. For det ai l ed series on the distribution of factor income, see Appendix Tables II-A1 to II-A14.

22