Hamline University Hamline University

DigitalCommons@Hamline DigitalCommons@Hamline

School of Education and Leadership Student

Capstone Projects

School of Education and Leadership

Fall 2019

Promoting Student Metacognition to Aid the Writing Process Promoting Student Metacognition to Aid the Writing Process

Jessica Kramar

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_cp

Part of the Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Kramar, Jessica, "Promoting Student Metacognition to Aid the Writing Process" (2019).

School of

Education and Leadership Student Capstone Projects

. 390.

https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_cp/390

This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education and Leadership at

DigitalCommons@Hamline. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Education and Leadership Student

Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Hamline. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

PROMOTING STUDENT METACOGNITION TO AID THE WRITING PROCESS

by

Jessica A. Kramar

A Capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Education

Hamline University

Saint Paul, Minnesota

November 2019

Capstone Project Facilitator(s): Kelly Killorn

Content Expert: Shelley Orr

Peer Reviewer: Tessa Ikola

ABSTRACT

Writing is a process that occurs over multiple steps; this may seem both excruciating and tedious

to students. By encouraging metacognition throughout the process, teachers can create more

autonomous learners. This capstone uses reflective strategies that address the question How can

educators use independent and group reflection processes to help students assess their

understanding and mastery of writing state standards?

Research concludes that guided

interaction with feedback increases student accountability and understanding of effective writing.

Through a series of reflective strategies, modeling, and both critical and positive feedback,

teachers can shift the way students think about their own writing, benefiting both the classroom

culture and the mastery of writing assignments. A literature review implied that both the writing

process and metacognition are transferable critical thinking skills across content areas and

assignments that increase both student success and confidence. Because of this, a research unit

was designed to incorporate lessons to provide students with independent and discussion based

metacognitive strategies. Students were given examples of reflective practices to guide them.

Lessons also included opportunities for different types of reflective activities. Although it does

take additional time to include metacognition in the classroom, strategies should take place

frequently and purposefully to establish a culture of interactive reflection.

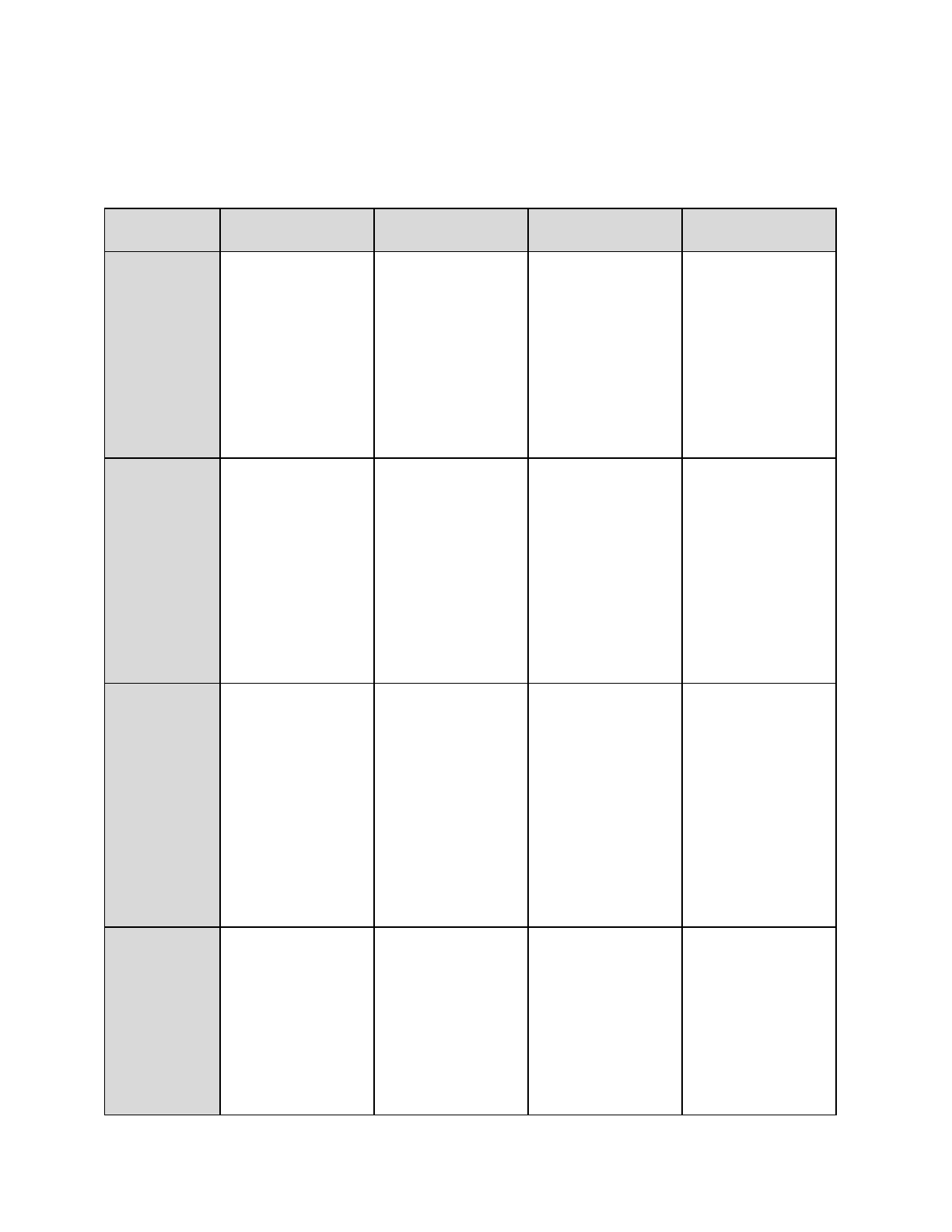

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE 5

Introduction 5

Professional Context 5

The Importance of Metacognition 7

How Metacognition Impacts Teacher Planning 8

Conclusion 9

CHAPTER TWO 11

Literature Review 11

Reflecting on the Writing Process 11

Foundations of Constructivist Theory 12

The Writing Process 14

Planning 16

Drafting 16

Revising and editing 17

Rewriting or trying a new approach. 18

What Teachers Contribute to Student Reflection 18

Feedback 20

Modeling 21

The student’s role during reflection 23

Individual Reflection 23

Participation in groups 25

Conclusion 27

CHAPTER THREE 28

Project Description 28

School Context and Rationale 29

Evidence of Learning 30

Writing Pedagogy 33

Benefits of Metacognition in Other Content Areas 34

Participants and Timelines 35

Conclusion 36

CHAPTER FOUR 36

Critical Reflection 36

Capstone Literature Review Highlights 37

Limitations of the Project 38

Project Successes 39

Application to the Profession 40

Conclusion 41

References 41

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

American schools have always obsessed over new ways to support and best serve our

students. As a means to promote intrinsic motivation and increased student accountability,

educators are encouraged to provide students with choice

and voice

. By releasing some of the

responsibility from teachers to their students at an appropriate level of development, “[s]tudent

voice and youth engagement provide examples of motivating youth academically through

data-driven reform” (Yonezawa, 2009, p. 206). One such way to encourage student voice is to

promote student discussion through metacognitive activities in small groups.

My capstone question is specific to my course and schedule: How can educators use

independent and group reflection processes to help students assess their understanding and

mastery of writing state standards?

This question will help me guide the small groups I conduct

weekly. The goal for these groups is to help students reflect on their understanding of writing

standards, so we can promote self-assessment and capacities for growth in learning, provide

remediation or extension, and help clarify anything they think is vague. By modeling and

scaffolding metacognition strategies, eventually students will be able to generate conversation on

a more independent basis.

Professional Context

As a young teacher, the best compliments I received revolved around being liked. It was

great to hear that students enjoyed being in class, but eventually, those compliments were not

fulfilling. It was not until I started hearing a new compliment that I truly felt like an effective

teacher: being in my class made students strong writers. Now, this was a statement I would hear

on exit surveys or from the teachers who had my former students, but they were few and far

between. That was when I was inspired to look at the practices centered around the writing

process, how I provided feedback, and how to engage students in their learning. These beliefs are

one of the reasons I attended a professional development session that was based on reflection.

During a staff development day, I registered for a session called “Student Reflection as a

Tool for Learning.” In this session, I experienced a bit of cognitive dissonance that made me

want to explore the topic further. First, they explained that stopping to predict what will happen

next in a book is evidence of student reflection. There were a few confused faces in the room,

including my own. I always assumed reflection was a final step in the learning process. Their

statement made more sense when the presenters defined reflection as a purposeful pause in

learning in order to move forward. Reflection to me was always thinking about your thinking; I

still was not sure if I completely agreed with that definition based on my own views of reflection.

Further research was needed.

Another moment during the professional development session that inspired me to dig into

metacognition was the emphasis on the instructor’s implementation of reflection using feedback.

They walked through all of the pros and cons they noticed and how they adjusted their practices.

Because their implementation was based on Jane Pollock’s text Feedback: The Hinge That Joins

Teaching and Learning

, a lot of their lessons revolved around students providing feedback for

each other. Based on my experience with students, I personally wanted to explore teacher

feedback, not peer feedback, because my former students provided superficial compliments

during peer review. They would express comments like, “good job!” or “strong paragraph” that

did not provide guidance for each other. I wanted to discover how to coach students on how to

look at their own writing critically in order to have discussions about with their peers to see if

that was more effective in aiding the writing process.

The outcome of this capstone is to help students assess their understanding of the

Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts, specifically in grades 9-10

writing as well as the Earned Honors Standards in the district where I work, in order to help

make adjustments to their learning or behaviors. Maybe their reflection leads them to coming

into my office hours. Maybe their self assessment helps them see that their topic sentences are

not claims, but summaries. They may even decide to visit our Writing Center with prepared

questions. Whatever their conclusion is, I want to help students improve their metacognition in

order to advance their writing. My teaching setting is contextualized in order to understand the

writing best practices that are present in the project.

The Importance of Metacognition

Reflection, metacognition, self assessment, and self evaluation are used interchangeably

throughout this project. Due to the abstract nature of reflection, researchers have taken multiple

routes to define it. In Benton’s 2013 research, they arrived at a holistic definition of reflection:

Metacognition encompasses a number of cognitive processes that could be called

thinking skills, study skills, or simply astute self-awareness and independent learning.

Metacognition cannot be relegated to a simple list of study or practice skills because it

requires a deeper level of thinking and a broader array of teaching and learning

activities... Educational researchers conclude that metacognition includes self-awareness,

self-evaluation, and self-regulation, leading to learners' increased control of their own

thought process (p. 53)

This cyclical process is intended to evaluate a student’s deep understanding of critical thinking

skills, and in this case it is the writing process. Research suggests that metacognition is

incredibly important for students for two main reasons: it creates a growth mindset and holds

students accountable for their learning (Nelson & Bishop, 2013, p. 19-21).

This topic is not only important to me, but is helpful for any educator because both

writing and reflection are cross curricular skills. In my school, our building goal for the

2018-2019 school year was anchored in ACT Writing scores. Math and science classes practiced

writing essays in their classes. This is essential in developing long-standing writing skills and

allowing writing in “other content areas enables students to make the connection between writing

well and providing well-written evidence of their understanding” (Merten, 2015, p. 18). One of

my goals for this project is to develop strategies and sentence stems that can be applied to any

subject or assignment.

How Metacognition Impacts Teacher Planning

I developed a personal interest in this subject matter when I realized the importance of

reflecting on my own teaching practices. It took a few years of teaching to realize that I did not

have all of the answers and best practices established after my undergraduate program and a year

or two of experience under my belt. Once I saw the power of metacognition and how it positively

impacted not only how I teach, but how my students performed, I knew that it was a skill I

wanted to encourage my students to practice.

Last year, I attempted to conduct small groups with minimal preparations and research. It

was unsuccessful for a couple of reasons. First of all, norms and behaviors were not established

enough. We are encouraged to use flexible spacing and meet outside of the classroom. When I

was not close enough to the large sliding doors that open my classroom to a meeting space, a

student was vaping in my classroom. It proved that I could not manage a classroom and conduct

discussions by physically separating the small groups from the rest of the class. I resolved to

begin this process by meeting in a corner of a classroom. Once trust is built and the norms are

solid, then I can consider moving small group discussions into the hallway or letting the Earned

Honors Standards in the district I work help students invest in their choice, but will naturally

organize students into groups that will have similar needs. If students have a more clear

discussion point, they might find more purpose in the activity.

The discussions also failed because they did not have a greater purpose. It focused too

much on how they felt about the class overall and not enough on the learning they were doing.

As my collaborative team becomes greater advocates for the revision process, I want to tie these

discussions into the requirements of our summative essay revisions. Nielsen discovered, “A key

motivation for the use of self-assessment practices in the writing classroom is to address the need

for students to develop strong habits of drafting and revision” (2014, p.7). Not only should

students value the opportunity to reflect, but they should also learn to value this writing process.

Conclusion

Reflection is a continuous process of self evaluation and application of new knowledge. It

is an essential part of learning that needs to have explicit instruction. I believe that my new, more

structured approach to individual and group reflection will yield better results. After reviewing

several articles, I have selected specific strategies for my small groups to perform. The general

process includes modeling reflection, practicing self evaluation, sharing student conclusions, and

creating a follow-up plan. It is intended to emphasize the importance of the writing process

which is a cycle of writing, feedback, reflection, and revision. Finally, I can apply the results of

our small group discussions to lesson plans to fit the needs of each class.

Chapter Two synthesizes current literature on metacognition, teacher feedback, small

group discussion, and the writing process. There is a focus on how teachers can instruct writing

and how to facilitate reflection throughout the writing process. Chapter Three describes the

project taking place in a tenth grade English classroom. Finally, my critical reflection is

presented in Chapter Four to complete my evaluation of how metacognition and small group

discussion aids the writing process and impacts my teaching practice.

CHAPTER TWO

Literature Review

Reflecting on the Writing Process

What do students do when teachers provide feedback on their writing? They look at the

raw score first and then sometimes they look at comments briefly, but quickly move on to the

next task. If teachers never instruct students on how to interact with feedback, specifically

through reflection strategies, students may never apply what they learn about the writing process.

Teachers should be “promoting and reinforcing key messages about reflection, combined with

opening up more opportunity for reflective learning talk within class sessions,” enabling students

“to share their learning and their reference points more authentically” (Nelson & Bishop, 2013,

p. 24). This begs the question: How can educators use independent and group reflection

processes to help students assess their understanding and mastery of writing state standards?

The literature mostly centers around how students internalize the writing process and teacher

feedback and its impact on their mindset. In this chapter, I will be discussing peer reviewed

research that defines metacognition and justifies its role within the classroom. This chapter

discusses the writing process as a constructivist approach to learning, current writing standards,

and the steps of the writing process. In regards to application, chapter two also outlines the

teacher's role in writing and metacognitive instruction, and the student's role in learning how to

write which includes self-assessment. To better understand self-assessment, it concludes by

discussing reflection and how students can do this individually and as part of a group.

By participating in a reflective process, students develop a growth mindset and the

continuous growth of effective writing. Part of this awareness is developed through the

discussion of their reflection. Nelson & Bishop acknowledged that some students have

preconceived notions of a reflective project as a means of highlighting their weakness as

students, but one goal of this research is to help students see reflection as a lifelong skill

transferable to not only their writing, but other content areas as well (2013, p. 21). Although it is

difficult to do so, confronting weaknesses actually encourages a growth mindset and forces

students to take the next step towards improvement. It also makes students assess whether the

writing process was completed successfully and what they can do next time if it was not. They

will not only focus on their weaknesses, but also evaluate what makes their writing effective.

Student accountability increases when sharing their reflections out loud. Nelson &

Bishop (2013) suggests think-pair-share pedagogical structure promotes metacognition. It

enables students to take a personal look at their own learning, then gradually discuss these

reflections with small groups, and finally the entire class (Nelson & Bishop, 2013, p. 21). One of

the goals of this project is to create a community of safe risk-taking and a comfortable place to

be vulnerable. The effects of the second step should not only benefit the student’s ability to

reflect, but Wenzel (2007) believed that peer and self reflection develops critical thinking skills

as well as student buy-in. Wenzel continues to argue that this creates a more respectful, confident

student learning community (p. 183). It will hopefully become an integral part of an educator’s

classroom culture, which directly connects to the use of small group discussions to improve

student’s understanding of the writing process and have organic conversations about writing.

Foundations of Constructivist Theory

Constructivism in the classroom dates back to Kant, Dewey, and Piaget, but it has only

grown in popularity since then. Dewey’s rejection of the traditional classroom revitalized

education and made it hands-on for students, including using their own personal reflections; this

new approach emphasized that “[m]ental activities are needed in learning in order for students to

process their learning experience to become knowledge. In other words, education is a process

of modification of personal experience” (Pardjono, 2016, p. 166). Under constructivism, students

were no longer passive participants. Memorization was no longer the core of education.

The goal of constructivist theory is for learning to become more personal to students as

the emphasis is switched to their prior knowledge and how educators can build upon it. Even

assessments began to evolve. Brooks and Brooks (1999) argued that this constructivist approach

evaluates what students can generate, demonstrate, and exhibit, and not just what they can

memorize (p. 16). That being said, students’ interaction with feedback and their own personal

reflections can allow them to build on their knowledge of the writing process, creating stronger,

more adaptive writers. Although the challenge of constructivism is understanding and assessing

someone else’s knowledge efficiently, it makes teachers evaluate their own practices for

effectiveness. Are teachers assessing memorization and the regurgitation of information? Or are

teachers encouraging students to reflect on their own understandings? It should be the

demonstration of knowledge. Jonassen, Davidson, Collins, Campbell, & Haag all conclude that

according to constructivists, making meaning is the main goal of the learning process, requiring

reflecting on what is known to students (Jonassen et al, 1995, p. 11). In order to truly prove this

understanding, teachers should emphasize the importance of the writing process and how it

builds student skills.

If constructivism is a meaning-making process, there needs to be a level of buy-in from

students. Because writing is a difficult skill that students tend to be intimidated by, educators

need to find ways to motivate students to continuously evaluate their writing abilities and how to

improve it. There are multiple factors that engage students in the writing process including “the

person's desire for success (or failure), the value of the task as a motivation, and the method used

toward success” (Liu, 2014, p. 1). Liu is arguing that this intrinsic motivation has a high

correlation to student success. If teachers can increase student goal setting and motivation,

students will make greater strides in their writing.

The Writing Process

The writing process is a multi-step approach to composing a complete and polished piece

of writing. There are multiple variations of the process, but most include at least four steps.

According to Keen (2017), writing composition includes “overlapping processes and

sub-processes used recursively, including prewriting, drafting, revising

and celebrating

[publishing]. The key principle is that as far as possible writing starts with, follows and may

contribute to the development of students’ own experiences and ideas” (Keen, 2017, p. 376).

Most states recognize the importance of using a writing process to support writing with increased

complexity. The Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts states that

students must be able to follow a writing process in order to prove their college readiness. These

anchor skills are required to be taught starting in sixth grade and continue to be developed until

graduation (2010, p. 89). For the purpose of this capstone, standard 9.14.5.5 “Use a writing

process to develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, drafting, revising, editing,

rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a

specific purpose and audience, and appropriate to the discipline” (2010, p. 89) is used. According

to Understanding by Design, planning begins with the objective of a lesson (Wiggins &

McTighe, 2011, p. 37).

Although this project focuses on building reflection as a skills, using this standard as a

clear goal provides a way for educators to measure the success of their students. Not only do

students to clearly understand what each step of the writing process is, but they will also be able

to follow the writing process effectively in order to create a polished and effective piece of

writing. The article “Turning the Standards Towards the Student—A Metacognitive Aspect”

suggested that students track their evidence of mastering the standard for the following benefits

for both students and teachers:

It gives student and instructor a chance to determine what has been covered well and

what needs to still be done. It can be constructivist in nature, but the gap analysis done

will become valuable to both the student and the instructor. The metacognitive reflections

on what has been done to allow the student to reflect on their understandings and allows

the instructor to determine whether what they believe was accomplished was indeed

accomplished (Marcoux, 2011, p. 68).

When teachers and students work as a team, they are able to fill in the learning gaps together and

see higher achievement.

Each step of the writing process is described below according to the definitions provided

by Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab. Purdue University is a long standing expert on all

formatting options, and is a credible resource for writing instruction and aid. In addition to the

description of the writing process, the importance of reflection during particular steps is also

crucial to meeting writing state standards. Nielson examined how their research supported self

assessment in their writing instruction: they believe the only way to reach expert status in the

writing process is to move past working memory and commit the process to long term memory

specifically through metacognition and learner autonomy (2014, p. 4). Therefore, not only is a

solid understanding of the writing process crucial to developing strong writers, but also

instructing metacognition within certain steps.

Planning. The first step of the writing process is known by many names: prewriting,

planning, brainstorming, outlining, and even think aloud. Purdue encourages students not to

“worry about whether or not [their ideas] are good or bad ideas. [Students] can brainstorm by

creating a list of ideas that [they] came up with, or drawing a map and diagram, or just writing

down whatever [they] can think of without thinking about grammar” (“Stages of the Writing

Process,” nd, para. 3).

Planning can come in many forms, but it is intended for students to

generate as many ideas as they can in order to have a starting point for their writing.

Drafting. A draft is the first time students begin to write their text in sentence and

paragraph form. It is usually unpolished and incomplete. Unfortunately, students tend to think

they are bad writers because they often turn in a draft without completing the writing process. A

draft is composed of paragraphs that create a beginning, middle, and end of a piece of writing. It

is also usually the first attempt at completing a writing task. Purdue University stated that the

goal of drafting is to produce “a clear direction in [a student’s] paper. When [students] are

required to submit a rough draft, it doesn't need to be perfect, but it does need to be complete.

That means, [they] shouldn't be missing any of the major parts of the paper” (“Stages of the

Writing Process”, nd, para. 4). Because the expectation is not perfection, drafting is often one of

the first forms for formative assessment for a particular paper.

Drafting allows students to receive feedback, and for perhaps the first time in the writing

process, reflect on the quality of their writing. According to Lee, “self- and peer assessment,

formative feedback through multiple drafting, and portfolios are ways of realizing formative

assessment in the classroom. Such classroom activities allow reflection, interaction and

opportunities to return to one’s text and improve it” (2011, p. 99). Because this is intended to

organize the thoughts generated in the planning process, it is expected that the student changes

their draft. It is discouraged to turn in a draft as a final product.

Revising and editing. After drafting, students should reassess their writing. Revising

and editing are closely related steps that are often revisited multiple times in a cyclical fashion.

Purdue suggested that when it comes to revision, students may add or remove paragraphs to

better support their thesis and genre. Simply put, they are reorganizing their writing in order for

their audience to follow their progression of ideas more efficiently (“Stages of the Writing

Process,” nd, para. 5). This is where feedback is most crucial. Sometimes, students apply their

feedback one point at a time, but sometimes they use it to build on their knowledge of writing as

a whole. “Even when using the feedback as a manual for corrections, students may enter into a

negotiation with the feedback, taking into consideration their own understanding of both the task

and the feedback provided” (Bader et al., 2019, p. 1023). This is the decision-making process

students enter as they choose what to keep and what to change.

Editing, on the other hand, is where students tend to concentrate their efforts when they

are given the opportunity to revisit their work. Purdue emphasized that this is “a lot like

polishing” student writing (“Stages of the Writing Process”, nd, para. 9). It is correcting

mechanical errors, focusing on grammatical perfection, and perhaps making more sophisticated

vocabulary choices. Although this is important to composing academic writing, student

improvement is rooted in revision that improves content objectives, not just English conventions.

Rewriting or trying a new approach. Standard 9.14.5.5 includes the opportunity to

rewrite or try a new approach because it aligns with common core beliefs that it will develop

writer resiliency. Rewriting is not typically intended for the entire piece of writing; it usually

takes place in the intro, conclusion, or a particularly weak paragraph. A new approach could

mean completely starting over. This is the last step outlined in the state standard. Truly, the last

step in the writing process is publishing (“Stages of the Writing Process,” nd, para. 11-12). It is

sometimes called “celebrating” in order to create a more positive mindset for students.

Publishing is usually when students submit their writing for grading.

What Teachers Contribute to Student Reflection

Yangin explained that during writing instruction, “the language teacher acts as a

facilitator, guide, feedback provider, and evaluator when students move along these steps” (2012,

p. 1). In order to demonstrate what metacognition looks like for our students, particularly when

engaging in the writing process, teachers should take an active role in demonstrating reflection

and facilitating discussion activities. These active learning styles can be effective when

presented with sufficient background knowledge and proper guidance throughout the unit. Of

course, Kranhenbuhl suggested that implementation must be used in context to allow students to

easily transfer knowledge for a deep understanding and increase chances of success (2016, p.

102). This being said, scaffolding information for students and setting them up for success via

modeling is crucial for these methods to be effective. Ultimately, the role of the teacher is to

“encourage students’ sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem through positive feedback,

reinforcement and modelling” (Nielsen, 2014, p. 12). This section discusses how educators aid

students in the writing and reflection process in two primary ways: through feedback and

modeling.

Despite the fact that metacognition is a largely independent skill, the teacher still has to

provide data or feedback, scaffold the skill, and support students along the way. Educators know

how point-hungry students can be, so it is important to not focus on the grade, but the actual

learning taking place. After guiding students through reflective strategies, educators are

responsible for helping “the students interpret the peer- and self-evaluation and provide guidance

aimed at improving the functioning of individual and group performance. Some instructors who

use peer-evaluation have noted that students are initially reticent to express criticism of their

peers and are overly generous in their evaluation” (Wenzel, 2007, p. 185). After effective

modeling and practice, students should begin to delve into the writing process with a more

critical eye and produce better results. It can also help educators lesson plan.

Teachers will be able to adjust lesson plans according to the needs identified by their

students. Student-to-student and student-to-teacher discussion and tracking of student learning

allows teachers to assess their pacing and instruction to adjust plans as needed by students

(Nielsen, 2014, p. 5). Ultimately, by tailoring lessons and writing conferences to fit the needs

expressed by students, student confidence should also increase.

Feedback. After drafting, teachers should have a better idea where each student’s

strengths and weaknesses are when it comes to their writing skills. Feedback is perhaps the most

crucial part of student reflection and improvement. Educators need to give them something to

think about. Gallagher and Kittle argued that teachers approach feedback and grading differently

depending on the stage of writing students are participating in. Educators have a different lens

when grading writing, so they often miss the shining moments students display, fixating on the

grading criteria they’ve established (2018, p.110). When educators miss the small gifts and focus

on the errors, they can greatly impact student confidence.

The effect feedback has on the student varies greatly. Bader, Burner, Hoem Iverson, and

Varga (2019) examined how students perceive feedback:

Feedback can be helpful, it may have no effect, or it may have a negative effect on

students’ learning, achievement and motivation. Against the backdrop of such results,

various studies have attempted to identify qualities of effective feedback practices, and

there is a growing consensus regarding the kind of feedback practice that is more likely to

yield positive learning gains. In this respect, student engagement in the feedback process

is seen as one of the key ingredients of effective feedback practices. (p. 1018-1019)

Knowing what Liu (2014) had to say about intrinsic motivation, students will only engage in

feedback and revision if they believe they can make improvements. First of all, students need to

believe that you are providing criticism that makes them better, not pointing out all of their flaws

as proof of their fixated skills (McGuire, 2015, p. 167). Teachers want students to know that

although there is room for growth, there are still a lot of good qualities present.

Teacher feedback is largely tied to student emotion. Bader, Burner, Hoem Iversen, and

Varga (2019) emphasized this statement by suggesting that positive teacher feedback has the

power to affirm or boost the learner’s personal view of their abilities and increase their

confidence of achieving mastery (p. 1024-1025). In other words, feedback should be both

encouraging and fair, and specific enough to point students towards improvement. Harvey,

Bauman, and Fredericks (2019) go as far as saying that “emotion can be as important as, if not

exceed, the role of cognition in some aspects of student reflection; for example, when reflecting

on strategies for future improvement” (p. 1148). This means it is crucial for teachers to help

students see their strengths as well as their areas of improvement. By providing meaningful and

positive feedback, students should feel more confident about sharing their criticisms during the

small group discussion.

Modeling. Students are encouraged when teachers are writing with them. Modeling the

writing process is more than just sharing what the teacher thinks when they write themselves.

Benton (2013) argued that it is not effective to simply verbalize one’s thoughts. Rather, teachers

should think aloud in carefully planned, specific ways to guide students to ask reflective

questions and adjust work accordingly (p. 53). Gallagher & Kittle explain that teachers must

model the entire writing process using a genre that is easily applied to other genres, as long as

teachers present the numerous issues each genre might encounter (Gallagher & Kittle, 2018, p.

1). When it comes to the writing process, teachers should also demonstrate the following:

● the way we move an idea to a draft

● how we plan writing that shows an idea from start to finish

● how we solve problems in a draft

● how we how we seek feedback and then honor the students’ analysis of our writing to

build confidence in their ability to give feedback to each other.

● The struggle of writing well. These demonstrations not only develop our empathy for

their struggle, but also show students that writers need persistence. (2018, Gallagher &

Kittle, p. 90)

Of course, this takes time, so building modeling into lessons takes strategic planning, but it helps

students build trust in their teacher as a professional as well as the process.

Teachers modeling self reflection during the writing process provide students with

examples of the next step in the thinking process. Nielson predicted patterns that may include

“beginning writers [who] might spend more time on paragraph structure and transitions.

Intermediate writers might focus on parallel structure and use of complex sentences. More

advanced writers might evaluate their use of descriptive language” (2014, p. 8). Superficial edits

do not move students to more advanced writing, but students might not know what it looks like

to make more sophisticated choices. Modeling can show how teachers think through grading

criteria. Teachers can model how to apply the rubric to an example of student writing in order to

accurately assess a piece for writing, as well as use rubrics as a meta-analysis tool that allows

students to recognize the progression of their writing and provide a vehicle for discussion

articulating how they can continue to work towards mastery through critical reflection (Watts &

Lawson, 2009, p. 612). This type of modeling is often absent in many classrooms due time

constraints, but shows an increase in student understanding.

The student’s role during reflection

Students need to learn how to sit in the driver’s seat with their learning. Of course,

teachers are instructors and guides, but “when students learn about metacognition, gain learning

strategies, and become active learners, it empowers them tremendously because they begin to

understand that thinking and learning are processes that they can control” (McGuire, 2015, p.

27). Teaching metacognition is teaching students how to think and that it is a multi-step process.

Reflection is widely considered a process of learning that the student engages in. Two

popular models are the DEAL Model for Critical Reflection and the 4Rs model. Ash and

Clayton’s DEAL Model consists of describing experiences, examining in light of specific

learning goals, and the articulation of learning which includes action plans towards the further

progress of student learning (2009). The 4Rs model has been in practice even longer, and refers

to reporting and responding, relating, reasoning, and reconstruction (Bain, Ballantyne, Packer, &

Mills, 1999). Regardless of the critical reflection program students participate in, they all

encourage student self awareness of their learning through multiple thinking steps. This will set

the students up for their peer discussions.

Individual reflection. Regardless of which model is followed, students must be able to

self-reflect in order to participate fully in the writing process. According to Lee (2019), both self-

and peer-evaluation aids students in their understanding of formative feedback through the

drafting process. These types of classroom activities facilitate interaction with feedback, allows

reflection, and provides students with opportunities to return to their writing and improve it

(2019, p. 1017). It gives purpose to not only the writing process, but it also engages students in

the feedback provided by the instructor. For effective reflection, educators should provide

students with individualized tasks as well as holistic prompts that inspires global response

(Nielsen, 2014, p. 11). These prompts help students focus on specific skills first so they are not

overwhelmed by large-picture questions.

There are many types of metacognitive strategies that students can participate in before

they proceed to groups or the next step in the writing process. The most common guide to self

reflection is through a series of critical analysis questions. Open-ended questions should give

students the opportunity to explore their work, such as “What do you see as the special strengths

of this paper?” and “What do you notice when you look back at your earlier work?”

(Underwood, 1998, p. 18). This is not the only way to encourage reflective activities. Wenzel

suggests that teachers take a numerical approach, allowing students to rank their work using a

specific set of criteria when they answer these questions (2007, p. 183). These questions may be

used during revision phases as well as a final reflection phase once the paper is published.

Reflection should also occur at the end of a writing assignment. Students “were asked to

reflect on how satisfied they were with their assignments, what the feedback told them to revise,

what they learned from the feedback, what revisions they made, and what helped them

successfully complete their assignments. Neither the peer reviews, nor the reflection notes were

graded” (Bader, Burner, Iversen, & Varga, 2019, p. 1019). Although they may not be able to

make improvements to the assignment that was just completed, students should be able to apply

what they learned on future assignments.

During the metacognition and writing process, it is important for students to self monitor

their thoughts in order to maintain a growth mindset. Students who have self deprecating and

negative thoughts tend to have a negative correlation to their learning efforts (Hirsch, 2001, p. 1).

To counter a possible fixed mindset, McGuire (2015) suggested having students simply pay

attention to their self talk for a day. Then, teachers should “encourage them to locate the answers

in their behavior and attitudes, rather than external circumstances. Invite your students to

metacognitively investigate their attribution theories and to consider the possibility that they hold

the power to change their results by changing their behavior” (McGuire, 2015, p. 99). If students

can control their behaviors and make positive changes, they may see greater results in their

learning knowing it is also something within their control. For example, students can evaluate

whether their essay had a low score because the teacher was being critical, or if they skipped the

outlining process and had a disorganized argument. Once students can self assess and work

towards a growth mindset, they are ready to collaborate with their peers.

Participation in groups. As stated before, students must self reflect to construct

important questions; then, they must reflect with their peers to have their questions answered and

construct new meaning from their experiences. This work is largely formative and not intended

to be a final assessment of students’ mastery of the writing process. In the research, multiple

authors suggested providing predetermined standards as well as sentence starters that promote

open ended evaluation and discussion (Benton, 2013; Jansen, 1995; Nelson, 2013; Wenzel,

2007). These reflection building blocks allow students to internalize the skills they are working

on and assess their own understanding or deficits in their discussion groups.

Peer-to-peer interaction allows students to both give feedback and apply criticism to their

writing. It is important to note that peer feedback should always be in addition to teacher

feedback (Yangin, 2012), and students should first reflect on their own writing first. In Bader,

Burner, Iversen, & Varga’s study, students tended to view peer feedback negatively, increasing

these negative feelings when it was the only feedback they received on a writing assignment. On

the other hand, Bader et. al also discovered that when it was in addition to teacher feedback,

students viewed peer feedback as a positive thing (2019, p. 1022). This interaction not only

builds individual writing skills, but it becomes a part of classroom culture. Nelson & Bishop

noted that metacognition evolves from an independent process such as private journaling in a

notebook that is only seen by a teacher, to a collaborative process where students have

collaborative discussions reflecting on common criteria students needed to process (2013, p. 22).

A goal for students reflection is for this type of peer-to-peer interaction to happen frequently and

effectively.

Reflecting on group goals during discussion also improves the transfer of knowledge.

Elias concluded their article by stating that “the focus on both individual social-emotional

competencies and improved group functioning helps prepare students for the many future

contexts in which their success will depend on both” (2015, para. 10). If they are all working

toward a common goal, such as revising together to create stronger essays, they should see more

purpose in the activity. It is also an affirmation of their own understanding as stated by Cook et

al. (2013) that students in groups show an increase in evaluating peers’ thinking, as well as being

more reflective about how to approach the information versus when they work alone (p. 962).

This is yet more support for incorporating student voice in the learning process.

One way teachers can see students using the writing process in groups is by monitoring

the use of school writing centers. Students can visit their writing center during lunch or their

prep, or teachers can invite writing coaches to facilitate conferences in their classroom. McGuire

presented the argument that many students do not utilize instructional centers because they are

stigmatized as a resource soley for struggling students (2015, p. 97). In fact, they counter this

assumption by rebutting, “learning center professionals can impact learning at both ends of the

performance spectrum, and at all levels in between” (McGuire, 2015, p. 111). It is up to the

instructor to create a culture of improvement by sharing anecdotes of students’ success and

showing students the benefits of conferencing with their peers. By inviting coaches into

classrooms, students get used to discussing their writing with a peer and hopefully self-select to

visit the writing center.

Creating the “Next Step.” Because the teacher has already modeled how to apply

feedback from the rubric, the desired outcome is for students to be able to look at both teacher

and student feedback and use it to edit and revise their essays. It also helps them see trends in

their own writing and set goals for future assignments. According to Chesbro (2008), students

who take a metacognitive approach recognize patterns in how their formative practice impacts

their overall grade, allowing them to predict how their future assignments will affect their grade.

Chesbro continued to argue that this interaction with students grades is essential to learning

because “teachers who distribute grades in a shroud of mystery are doing a deep disservice to

students” (Chesbro, 2008, p. 58). The more students interact with feedback and grades, the better

they will be at understanding the overall measurement of achievement in American schools: their

grade. If the reflection process is effective enough, this type of extrinsic motivation will shift.

Gallagher and Kittle stated, “When students are engaged in writing problems, they analyze what

they know and focus on addressing their weaknesses with their next composition; they work like

writers, not simply students” (2018, p. 104). It is then that the writing process is truly mastered.

Conclusion

The writing process can be traced back to the constructivist theory, as students are

building their knowledge and writing skills continuously. Minnesota State Standard 9.14.5.5

requires students to be able to follow all of the steps in the writing process: planning, drafting,

revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach (2010, p. 89). After the drafting phase,

teachers should provide formative or ungraded feedback, paying close attention to not only

errors, but also the strengths of the writer. This provides something for the individual student to

reflect on. In addition to teacher feedback, students should also participate in peer-to-peer or

small-group discussion. Discussion allows the students to authentically delve into feedback,

provide assistance to one another, and continue to develop their writing. Once the final steps in

the writing process are completed, students should reflect on their writing once more to set goals

for future writing assignments.

In Chapter Three, the application of this information is described. Tenth grade students

will be asked to track their personal reflections on their writing throughout the first quarter of the

school year. In addition to personal reflections, a variety of discussion strategies will be

implemented that focuses on the stages and success of the writing process. The success of this

project will be determined by the number of students who are meeting the state standard or who

are making progress towards mastery.

CHAPTER THREE

Project Description

According to the Understanding by Design Framework (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011), the

first stage of planning is to identify the desired results. As stated earlier, the goal of this project is

to fulfill the Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts standard 9.14.5.5:

“Use a writing process to develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, drafting,

revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most

significant for a specific purpose and audience, and appropriate to the discipline” (“College and

Career Readiness”, 2010, p. 89). With this standard in mind, I asked the question, How can

educators use independent and group reflection processes to help students assess their

understanding and mastery of writing state standards?

This project consisted of a series of

metacognitive activities that are formative in nature in order for students to assess their

competencies in the writing process. One goal of this project is to develop students’

self-reflection skills. Students will not only be self reflecting, but they will also be discussing

their findings in small groups to increase accountability and metacognition. All planning will be

completed using the Understanding by Design Framework created by Wiggins and McTighe

(2011).

School Context and Rationale

My school runs on a modified block schedule. Once a week, each class period is 86

minutes long. My project was conducted in five Pre-Advanced Placement English 10 classes.

All sophomores must take this course. Using the extended class periods, I will be guiding their

self reflection and conduct small group discussions that focus on writing standards. Students are

provided three to five Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts Grades

9-10, as well as multiple Earned Honors Standards, choosing two standards to focus on each unit.

This capstone was tied to three of my school’s learning targets targets for every lesson:

include intended purpose, encourage student voice, and assess student understanding. When

looking at my research question and desired outcomes, my project largely focuses on purpose,

voice, and assessment of understanding. Reflection strategies can either highlight the importance

of why the writing process is important (purpose) or it can help students examine their mastery

of the writing process (assessment). Through discussion groups, students will be able to have

their voices heard.

Earned Honors is a new program embedded into the Pre-AP English 10 curriculum at the

request of the school board and administration. We consider it an enhancement to an already

enriched course. It provides an opportunity for students to prove their understanding of

additional skills that are interdisciplinary or above grade level. If they meet these standards

multiple times throughout the semester, their transcript changes to “Honors Pre-AP English 10.”

The semester one Earned Honors Writing Standards are adapted from the College Board’s AP

rubrics as well as from Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts Grades

11-12. The two honors standards will be focusing on choosing the best evidence or appropriate

length of evidence to support a thesis statement and the use of rhetorical devices. I want to

provide these standards as options because students need to be intentional about their execution

of a skill in order to earn their honors indicator. They cannot earn honors if their writing

accidently or inconsistently meets the honors standard. On the other hand, students do not need

to attempt these additional skills, so they may choose two 9th-10th grade standards. Although

there are no Earned Honors standards that are directly related to the writing process, reflection is

a skill transferable to all critical thinking skills.

Evidence of Learning

The final goal for this unit was to produce a 4-6 page argumentative research essay using

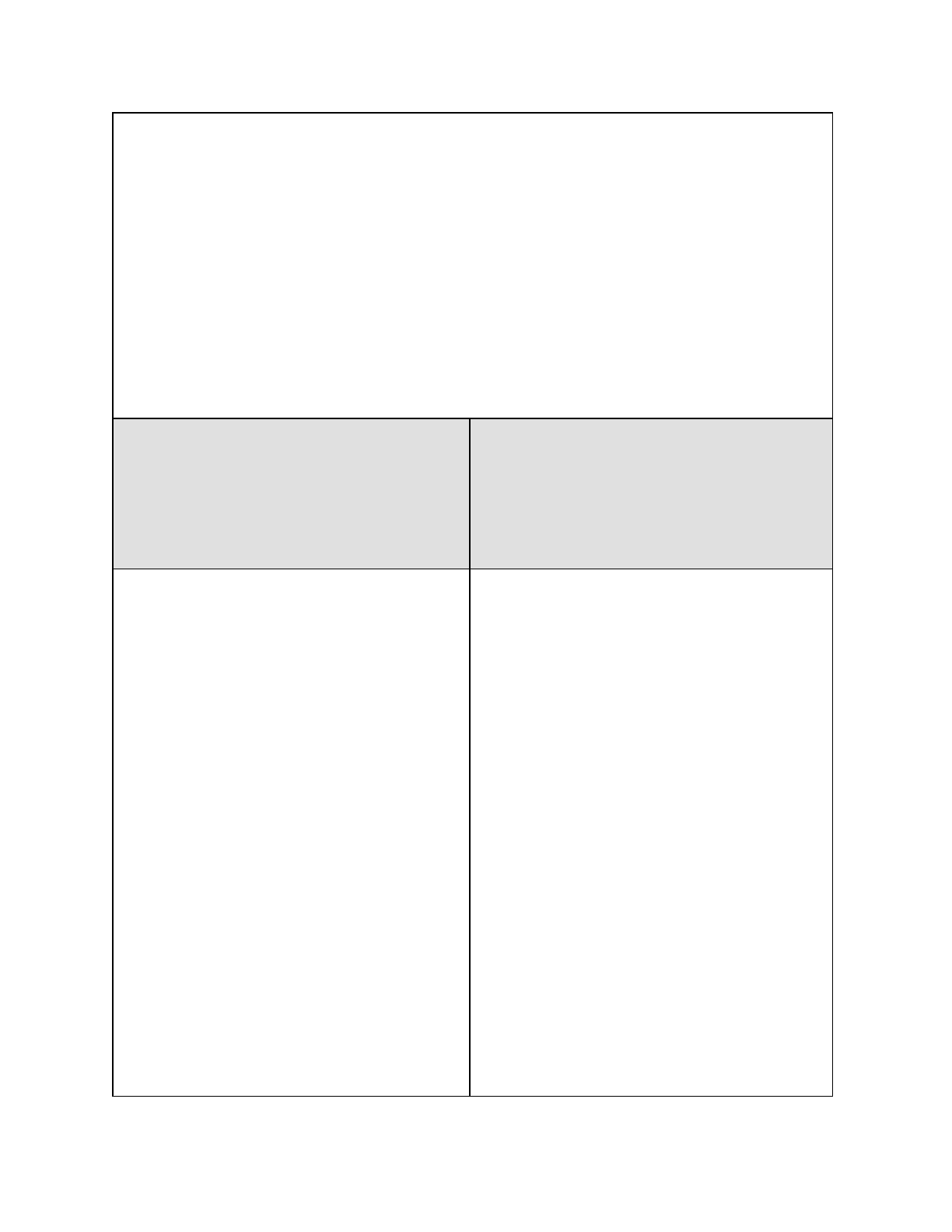

6-10 sources. Using Wiggins and McTighe’s (2008) design template (Appendix D), a unit was

created to work towards this summative assignment.

In order to measure metacognitive skills, I used a variety of assessments. Tomlinson

emphasized the importance of teaching “in a variety of ways to accommodate students' varied

readiness needs, interests, and learning preferences” (2006, p. 28). Feedback was provided on

both a rubric and written on their essay, on multiple formative assignments throughout the unit,

and students completed non-graded reflections in two different forms. Finally, students

participated in multiple small group discussions.

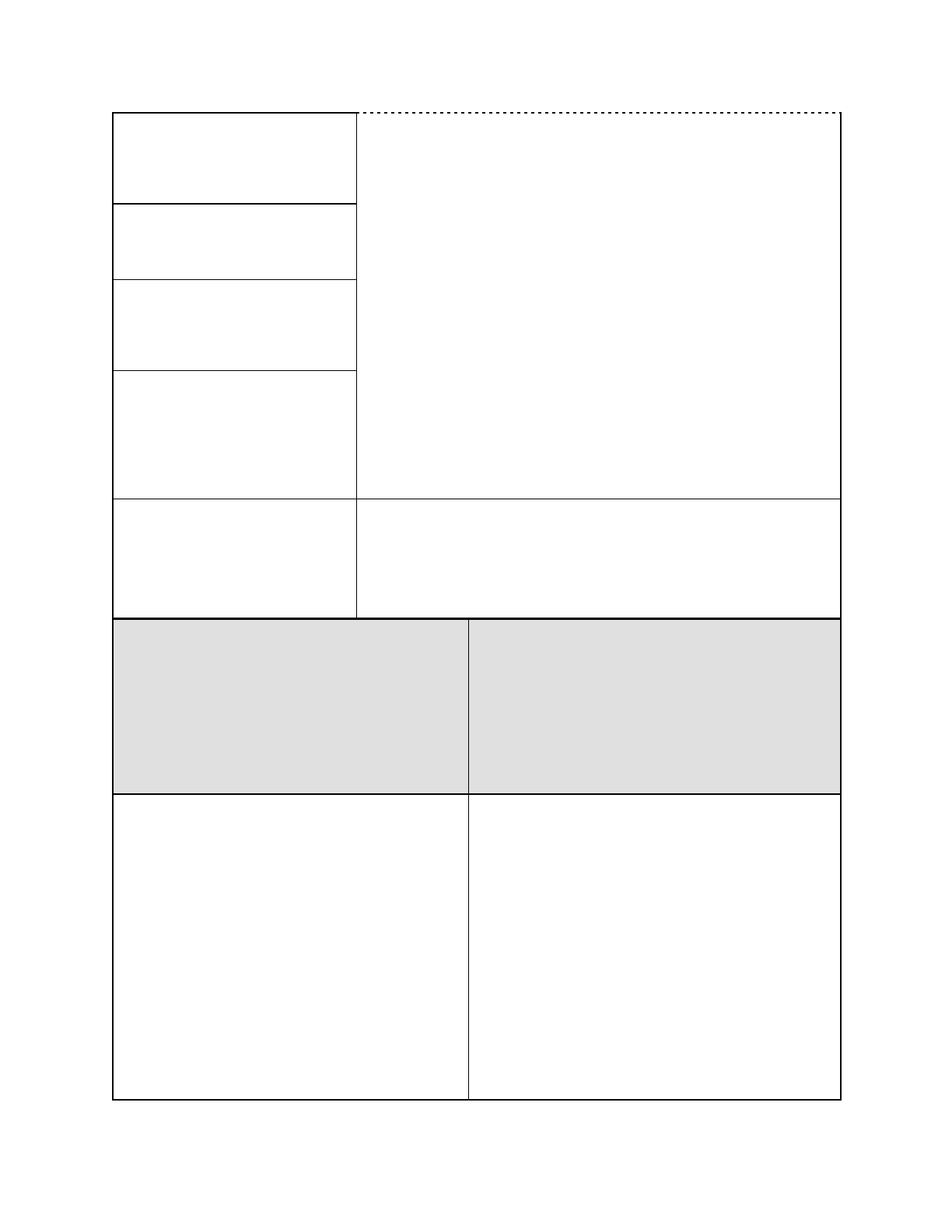

All summative writing assignments use the same standards based rubric (Appendix C)

because “educators should establish indicators of success, describe the criteria by which they will

measure success, measure students accordingly, and report the results in a clear and consistent

manner” (Tomlinson, 2006, p. 71). The rubric contains standards based indicators that measure

successful writing. Essays are evaluated based on their content, organization, style and language,

and mechanics. At the beginning of the unit, students reviewed this rubric as well as essay

comments for their first major writing assignment, a one paragraph explication essay. Bader,

Burner, Hoem, Iverson & Varga explained that “positive feedback has an important role to play

in affirming or boosting the learners’ self-perception of their capability and raising their

expectancy of success on a task” (2019, p. 1024-1025). Because of this, I made sure to comment

on one strength for every student’s essay.

In order to help students interact with their feedback to help them internalize the

information and construct new knowledge, a reflection form was provided (Appendix B). The

form helped students interpret teacher feedback from a previous unit and think about how they

can transfer their new knowledge to the next writing assignment. Providing time to think about

feedback is essential in making small group discussion more fruitful.

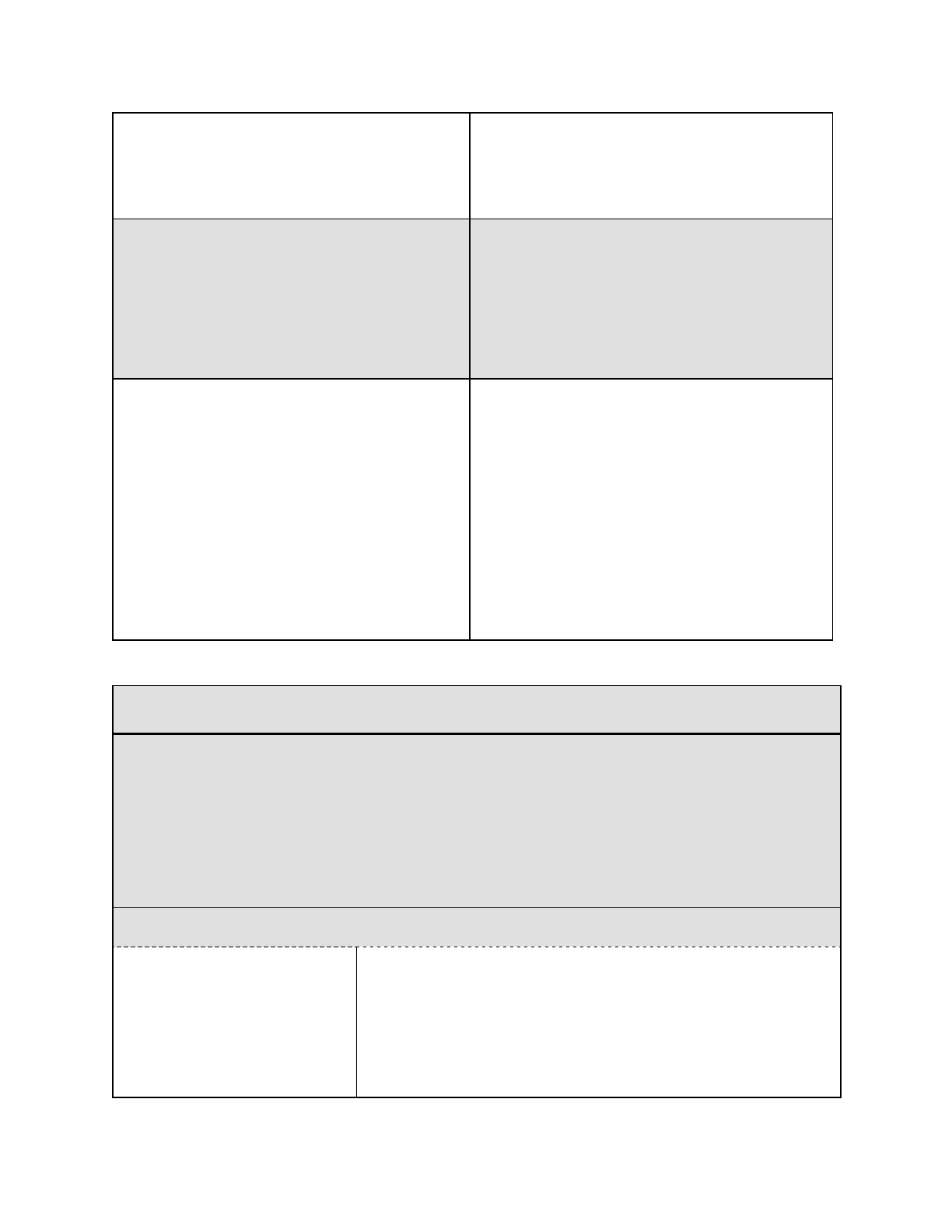

One of the more versatile reflection strategies is using an abstract rating system. Nelson

& Bishop recommended using “a visual rating system in the form of different colored paint

blotches (Murdoch, 2005), ranging from amazing through terrible, to their learning in a particular

area, with students selected at random to contribute and justify their selection (Nelson & Bishop,

2013, p. 21) Using this research, I created an emoji scale (see Appendix A). The scale ranged

from a “clueless” standpoint to the mastery of the skill as symbolized by the following emojis:

(pile of poo), (expressionless face), (smile), (smiling face with open mouth and

smiling eyes), and (unicorn). The emoji scale is an abstract visual representation of what they

thought of their writing accompanied by a justification. As an added bonus, visual representation

is suggested by WIDA (2012) to engage and accommodate Multiple Language students. By

using a little humor, it engaged students and allowed them to have a full range of attitudes about

their progress, including creating a growth mindset: “Using humor can encourage students to

take risks despite incurring temporary academic setbacks; therefore, students are able to further

engage in the learning process (Pollak & Freda, 1997). Students used this reflection check-in

multiple times throughout the unit to track their progress; it could be applied to a range of

processes and topics.

The final type of informal assessment was during group discussion. This type of group

collaboration was crucial because it “contributes to a student’s understanding of personal

self-esteem, ability to think symbolically and critically, willingness to cooperate with others, and

build communication skills” (Chenowith, 2016, p. 36-37). It also allowed students to be a part of

a learning community. As concluded from research, “[p]eer discussions may play a significant

role in supporting students in their interpretation and use of feedback” (Bader, Burner, Iversen,

& Varga, 2019, p. 1019). If students could effectively discuss their writing process and their

feedback, they could show evidence of moving towards mastery. This cycle of self reflection,

application of knowledge, and small group discussion is flexible to accommodate lesson

planning.

Writing Pedagogy

Metacognition as a part of a writing process approach to writing pedagogy emerges out of

constructivist theories of learning. Minnesota Common Curriculum State Standards (2010) also

recognizes the process approach, and I am following state standards in my curriculum design.

Students should be reflecting individually, with peers, and then individually again in order to

fully delve into their practices.

Neilson (2014) provided ten strategies to concentrate on student efficacy and classroom

collaboration when it comes to metacognition instruction. Teachers should provide detailed

instructions and practice time for self assessment strategies. Teach students how to correctly

evaluate specific writing criteria, provide models of each writing skill, and make sure

self-evaluation task are both specific and holistic. Take on writing together: encourage student

voice by creating evaluation criteria together, keep students motivated through positive

reinforcement, and always provide support or intervention time. Keep the stakes low by making

reflection formative, providing a safety net if students fail. The final three strategies encourage

independence and self-efficacy: allow sufficient independent work time on reflection activities,

give positive feedback to their strengths and model how to fix their weaknesses, and let students

revise their work after frequent, complete self assessment (Nielson, 2014, p. 9-12). Teachers

should regularly assess the effectiveness of their classroom practices and should use as many of

these strategies as possible.

With all of this in mind, I used Wiggins and McTighe’s (2011) idea that instruction

should be scaffolded in order for learners to be able to transfer the knowledge to their own skills.

As students become more familiar with each of the steps in the writing process, I provided less

instruction and support and rely on the questions they being forwards to guide them. Each step of

the writing process--planning, drafting, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new

approach--were all taught explicitly, with opportunities for guided and individual practice and

reflection. Wiggins and McTighe cautioned that it is common for students to “work too rigidly or

mechanically in applying their learning, rather than seeing application as use of an idea,” so

teachers need to “change the set up so that students realize that use of prior learning comes in

many guises” (2011, p. 115). Because the standard is for students to be able to follow the writing

process on their own, I used a variety of approaches to each step, as well as a variety of

assessments that helped students learn to be flexible with their thinking.

Benefits of Metacognition in Other Content Areas

Both writing and metacognition are skills that can be applied to multiple disciplines in

education. Ganz and Ganz (1990) discussed how the “use of graphic organizer construction (a

technique that expands study strategies beyond outlining) was enhanced by metacognitive

training” in history classes (p. 183). They also discussed the benefits of using a similar strategy

in biology. This has less to do with the actual outline strategy and more to do with teaching

students how to think about their thinking. Most importantly, metacognition helped students

become successful young adults (p.183). Ganz and Ganz (1990) argued that students with

essential metacognition skills “will be able to describe their thinking process, mental

organization, and future strategies when coping with a problem” (p. 184). Although content

knowledge is important, it is easily forgotten over time. Metacognition can help students relearn

or apply knowledge in new ways.

Participants and Timelines

This project was conducted in a high school setting. I teach in a large, wealthy district in

Minnesota. Almost 3,000 students attend the high school containing grades nine through twelve.

The minority enrollment is only 24% of the total student population. Administration approved

this project.

The course was a sophomore English class. Because I teach five sections of the same

course, approximately 155 students participated in this project. The course was designed to

prepare all students to take Advanced Placement courses in the future, so it is heterogeneous is

ability. English as a Second Language, Individualized Education Plan, and Section 504 students

are included in all activities, but may receive accommodations or modifications to fit their needs.

This is a required course; there is an option to earn an honors indicator by mastering skills above

grade level or across disciplines. There are two opportunities to earn honors using this writing

skill, but the goal will be for all students to meet grade level proficiency levels. If parents did not

want their students to participate, they opted out of the publication, but still participated in

activities.

Over the first quarter of the 2019-2020 school, I implemented a variety of metacognitive

strategies on block days, as well as instructed on the writing process during each unit. Block days

are extended class periods that allow for more instruction and work time in a single setting.

Metacognitive activities not only broke up the 88 minute class periods, but gave students more

time to delve into the writing process. In the primary weeks, students will be focusing on

individual practice, modeling, and feedback. After a few weeks, we shifted towards group

discussion. The final reflection focused on next steps and transferring knowledge to future

assignments.

Conclusion

This project was designed to meet the Minnesota State Standard 9.14.5.5. Through a

series of reflective activities, students assessed their mastery of the writing process. As their

teacher, I used a variety of assessments to measure their progress and provide feedback on how

to improve their self reflections. Through these strategies, the desired outcome is to not only rely

on using an effective writing process to strengthen their writing, but to make them overall

reflective learners. In the following chapter, I outline the successes and challenges of promoting

student metacognition, as well as evidence that determines the success of building the skill and

meeting state standards.

CHAPTER FOUR

Critical Reflection

In chapters one through three, I discussed my literature review and project design that

answers the question: How can educators use independent and group reflection processes to help

students assess their understanding and mastery of writing state standards?

Chapter one

included my personal and professional context, as well as the definition and importance of

metacognition. There is also a discussion on how it impacts teacher planning. Chapter two

contained a concise review of literature published about metacognition, the writing process, and

peer and teacher feedback. There is a brief history of constructivism and how it connects to

student reflection, a thorough outline of the writing process, and describes how students can

discuss their writing together. My project implementation was described in Chapter three and its

role within my school’s context. Chapter three discussed the evidence of learning gathered

before and during student discussion. It used Wiggins and McTighe’s (1998) frameworks to plan

reflective strategies into lessons to be both meaningful and effective activities to meet Minnesota

state writing benchmarks. Next, in Chapter four I reflect on my own learning during my

Capstone project. I highlight information from my literature review that was particularly

influential to the success of this project. Implementation and limitations of this research is also

discussed, followed by the benefits of this project’s practice. There is an overview of Chapter

four’s conclusion at the end.

Capstone Literature Review Highlights

Looking back at the search that guided me through this process, I noticed that it forced

me to shift my thinking in directions that I did not necessarily anticipate. I had always assumed

that reflection was important, but did not know how to use reflection strategies the most

effectively. This made me focus on teacher and peer feedback and how students could think

about it in a way that made them stronger writers instead of just connecting the feedback to their

grade.

I also struggled to find relevant information to answer my question. There was research

that focused on college level metacognition, reflection in general, or writing only, but rarely was

their research about reflecting about student writing. Synthesizing bits and pieces of this

information helped me create my project. The most helpful sources were sources that provided

sentence stems that could be applied to any content area to aid me in my design.

Starting with Minnesota writing standard 9.14.5.5 and Wiggins and McTighe’s UbD

(2011) helped me see how successful my collaborative team already is at designing lessons to

produce strong writers. I was able to use lessons that were already designed, but took intentional

breaks to stop and measure progress during different stages of writing. Students also set goals for

their next piece of writing to show how although it may be applied on a different assignment, it

can improve the same writing skill.

Limitations of the Project

Overall, there were a few aspects of the project that I would consider altering. One major

issue was that reflection took a lot of time. As many English educators know, the writing process

is tedious, but yields better results when it is not rushed. Adding additional steps between stages

of writing made me evaluate the allocation of class time. In the end, I was forced to give up

writing time in class in order to provide students with time for independent reflection and small

group discussion. Although it was effective in the transfer of knowledge, students were

dissatisfied with the amount of homework they had to meet submission deadlines.

The other limitation to this project that was concerning was the fact that students were

inconsistent with their level of insight when they wrote personal reflections and had small group

discussion. For example, one student wrote on their post-summative reflection that they did not

realize the importance of outlining their essay first, thus resulting in a lower organization rating

than they thought they would achieve; this prompted them to visit the Writing Center before the

next essay was due. In their small group discussion, the only comment that this student was

willing to share was that they “asked for more help” on their next essay. Other students would

have greatly benefited from their analysis, but it remained a hidden gem of a thought. In the

future, I can combat this by providing more effective modeling, much like Benton described.

Finally, a limitation of the project itself was the fact that a culture of reflection was not

established. To truly be successful, I believe that students will need the opportunity to stop and

reflect after multiple steps in the writing process over a variety of writing assignments. Although

I saw steps towards autonomous behavior in my students, I needed to provide them with more

practice during an entire school year.

Project Successes

One of the most significant successes of the implementation of reflective practices was

seeing an increase in writing conferences. This was mainly because of the implementation of the

emoji survey. Students recognized when they needed help. Not only did this reflection result in a

higher number of students seek guidance during class writing time, but they were more willing to

self advocate during office hours or consult peer writing coaches. My favorite outcome was that

students were generating more thoughtful, specific questions about their writing. Help sessions

moved away from questions like “Is this an ‘A paragraph’?” to inquiring about how to revise

their counterclaim to a more sophisticated argument. They seemed to care more about the writing

process than directly asking about the grade they would earn.

The other highlight I experienced was during a small group discussion. Using a

think-pair-share model allowed students to process their thoughts before bringing it to a larger

group. One group actually cheered for their classmate when they had a personal breakthrough.

The student had never let a peer review their writing before this year, but they finally let a friend

in class critique their work when they did not understand one of my comments. Their friend had

a similar comment, so they worked together to interpret, correct, and then verify that they applied

it effectively. They were successful together.

Because of these positive student experiences, I feel more confident in my writing

instruction. I noticed that in the past, I did not do enough modeling. It required more frontloading

in my lesson plans, but providing students with examples and showing them how I would move

through the writing process to create an improved draft seemed very purposeful. There is still

room for more examples and writing with my students, but this was a step in the right direction.

Application to the Profession

Taking the time to check for understanding before progressing through the lesson or onto

the next unit seemed invaluable. Not only do I think metacognition is helpful for the writing

process, but it can easily be applied to other content areas.

Thinking back to my own learning experience, I believe personal reflection would be

helpful in mathematics and science. These courses are truly constructivist in nature, and if I had

the opportunity to reflect on the shortcomings of some concepts, I could have seen what I needed

to practice more to prevent falling behind. Math and science educators could easily use some of

the reflection sentence stems to construct questions that apply to each skill that they are

instructing.

There is also a push to increase the amount of writing in social studies classes. Although

teachers in other contents should not be fully accountable for writing instruction, I do think it is

important for them to have a basic understanding of the writing process. This will help them

guide students in the organization phases of writing where they start compiling their arguments

and required content. The biggest challenge for these instructors would be finding time to allow

students to write and reflect.

Thinking back to my professional development experience, reflection is so much more

than feedback. Although I understand their theory that reflection is simply a meaningful pause in

the learning process, I think it is more interactive than that. In the past, reflection seemed like an

extra step to me. It was an optional practice that I knew was helpful, but did not necessarily

value. Moving forward, there are a few key takeaways that will impact my practice.

Reflection should happen frequently and in different forms. In the future, my goal will be

to implement at least two reflective strategies per unit. The strategies I am most comfortable with

are entrance and exit slips with guiding questions, the emoji scale, numeric rubrics, small group

discussion, verbal writing conferences, and quick writes. These are the most appealing to me

because they can easily be adapted to any content or assignment within my school’s

curriculum.They also do not feel like extra steps, but more like a purposeful guide through my

instruction so I can make adjustments that fit student needs.

Conclusion

Overall, providing students with the time to practice metacognition during the writing

process was successful. Students were able to think more critically about their writing in a way

that enabled them to seek more effective help and make greater strides in their learning.

Although reflection is incredibly helpful in adding value to the writing process, it does take a lot

of time. Educators must be willing to make sacrifices in order to embed metacognitive activities,

whether that be from time taken away instruction, activities, or work time. If teachers

concentrate on teaching students how to be reflective learners, they will see higher rates of

achieving standards and more concrete critical thinking skills.

References

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The

power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher

Education, 1

(Fall), 25–48.

Bader, M., Burner, T., Hoem Iversen, S. & Varga, Z. (2019) Student perspectives on formative

feedback as part of writing portfolios, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education,

44:7, 1017-1028, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1564811.

Benton, C. (2013). Promoting metacognition in music classes. Music Educators Journal,

100

(2),

52-59. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.hamline.edu:2048/stable/43288815

Brooks, J. G. & Brooks, M. (1999). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist

classrooms.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Chenowith, N. H. . (2014). Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Cultural Scaffolding in Literacy

Education. Ohio Reading Teacher, 44(1)

, 35–40. Retrieved from

http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.hamline.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eft&

AN=101191468&site=ehost-live

Chesbro, R. (2008). Using grading systems to promote analytical thinking skills, responsibility,

and reflection. Science Scope

, 32

(1), 58–60. Retrieved from

http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.hamline.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eft&

AN=507994866&site=ehost-live

Cook, E., Kennedy, E., and McGuire, S. Y. (2013). Effect of teaching metacognitive learning

strategies on performance in general chemistry courses. Journal of Chemical Education,

90 , 961– 967.

Council Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and the National Governors

Association. Minnesota Academic Standards English Language Arts K-12

. Minnesota

Department of Education, 2010. Retrieved from

https://education.mn.gov/MDE/dse/stds/ela/

Denton, D. (2011). Reflection and learning: Characteristics, obstacles, and implications.

Educational Philosophy & Theory, 43

(8), 838-852.

doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00600.%.

Elias, M. J. (2015, January 1). When Students Reflect on Group Participation and

Social-Emotional Goals. Edutopia

. Retrieved from

https://www.edutopia.org/blog/when-students-reflect-group-participation-and-social-emo

tional-goals-maurice-elias