1Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

2023

O ur Epidemic

of Loneliness

and Isolation

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the

Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

2Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Table of Contents

Letter from the Surgeon General 4

About the Advisory 6

Glossary 7

Introduction: Why Social Connection Matters 8

What is Social Connection? 10

Current Trends: Is Social Connection Declining? 12

Trends in Social Networks and Social Participation 13

Demographic Trends 15

Trends in Community Involvement 16

What Leads Us to Be More or Less Socially Connected? 16

Groups at Highest Risk for Social Disconnection 19

Impacts of Technology on Social Connection 19

Risk and Resilience Can Be Reinforcing 21

Call Out Box: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic 22

Individual He

alth Outcomes 24

Survival and Mortality 24

Cardiovascular Disease 26

Hypertension 26

Diabetes 27

Infectious Diseases 28

Cognitive Function 28

Depression and Anxiety 29

Suicidality and Self-Harm 29

Social Connection Influences Health Through Multiple Pathways 30

Social Connection Influences Biological Processes 32

Social Connection Influences Psychological Processes 33

Social Connection Influences Behaviors 34

Individual Educational and Economic Benefits 34

Educational Benefits 34

Economic Benefits 35

Chapter 1

Overview

8

Chapter 2

How Social Connection

Impacts Individual

Health and Well-Being

23

3Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Socially Connected Communities 37

The Benefits of More Connected Communities 39

Population Health 39

Natural Hazard Preparation and Resilience 40

Community Safety 41

Economic Prosperity 41

Civic Engagement and Representative Government 42

The Potential Negative Side of Social Connection 43

Societal Polarization 44

The Six Pillars to Advance Social Connection 47

Pillar 1: Strengthen Social Infrastructure in Local Communities 48

Pillar 2: Enact Pro-Connection Public Policies 49

Pillar 3: Mobilize the Health Sector 50

Pillar 4: Reform Digital Environments 51

Pillar 5: Deepen our Knowledge 52

Pillar 6: Cultivate a Culture of Connection 53

Recommendations for Stakeholders to Advance Social Connection 54

National, Territory, State, Local, and Tribal Governments 55

Health Workers, Health Care Systems, and Insurers 56

Public Health Professionals and Public Health Departments 57

Researchers and Research Institutions 58

Philanthropy 59

Schools and Education Departments 60

Workplaces 61

Community-Based Organizations 62

Technology Companies 63

Media and Entertainment Industries 64

Parents and Caregivers 65

Individuals 66

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence 67

Acknowledgments 69

References 72

Chapter 3

How Social Connection

Impacts Communities

36

Chapter 4

A National Strategy

to Advance

Social Connection

45

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

When I first took office as Surgeon General in 2014, I didn’t view

loneliness as a public health concern. But that was before I embarked

on a cross-country listening tour, where I heard stories from my fellow

Americans that surprised me.

People began to tell me they felt isolated, invisible, and insignificant.

Even when they couldn’t put their finger on the word “lonely,” time and

time again, people of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds, from

every corner of the country, would tell me, “I have to shoulder all of life’s

burdens by myself,” or “if I disappear tomorrow, no one will even notice.”

It was a lightbulb moment for me: social disconnection was far more

common than I had realized.

In the scientific literature, I found confirmation of what I was hearing.

In recent years, about one-in-two adults in America reported experiencing

loneliness.

1-3

And that was before the COVID-19 pandemic cut off so

many of us from friends, loved ones, and support systems, exacerbating

loneliness and isolation.

Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling—it harms both individual

and societal health. It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular

disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death.

The mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that

caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day,

4

and even greater than

that associated with obesity and physical inactivity. And the harmful

consequences of a society that lacks social connection can be felt in

our schools, workplaces, and civic organizations, where performance,

productivity, and engagement are diminished.

Given the profound consequences of loneliness and isolation, we have

an opportunity, and an obligation, to make the same investments in

addressing social connection that we have made in addressing tobacco

use, obesity, and the addiction crisis. This Surgeon General’s Advisory

shows us how to build more connected lives and a more connected society.

If we fail to do so, we will pay an ever-increasing price in the form of our

individual and collective health and well-being. And we will continue

to splinter and divide until we can no longer stand as a community or

a country. Instead of coming together to take on the great challenges

before us, we will further retreat to our corners—angry, sick, and alone.

Letter from the Surgeon General

Dr. Vivek H. Murthy

19th and 21st Surgeon General

of the United States

5Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

We are called to build a movement to mend the social fabric of our nation.

It will take all of us—individuals and families, schools and workplaces,

health care and public health systems, technology companies,

governments, faith organizations, and communities—working together to

destigmatize loneliness and change our cultural and policy response to it.

It will require reimagining the structures, policies, and programs that shape

a community to best support the development of healthy relationships.

Each of us can start now, in our own lives, by strengthening our

connections and relationships. Our individual relationships are an

untapped resource—a source of healing hiding in plain sight. They

can help us live healthier, more productive, and more fulfilled lives.

Answer that phone call from a friend. Make time to share a meal. Listen

without the distraction of your phone. Perform an act of service. Express

yourself authentically. The keys to human connection are simple, but

extraordinarily powerful.

Vivek H. Murthy, M.D., M.B.A.

19th and 21st Surgeon General of the United States

Vice Admiral, United States Public Health Service

Each of us can start now, in our

own lives, by strengthening our

connections and relationships.

Loneliness and isolation represent profound threats to our health and

well-being. But we have the power to respond. By taking small steps

every day to strengthen our relationships, and by supporting community

efforts to rebuild social connection, we can rise to meet this moment

together. We can build lives and communities that are healthier and

happier. And we can ensure our country and the world are better poised

than ever to take on the challenges that lay ahead.

Our future depends on what we do today.

6Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

A Surgeon General’s Advisory is a public statement that calls the

American people’s attention to an urgent public health issue and provides

recommendations for how it should be addressed. Advisories are

reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s

immediate awareness and action.

This advisory calls attention to the importance of social connection for

individual health as well as on community-wide metrics of health and

well-being, and conversely the significant consequences when social

connection is lacking. While social connection is often considered

an individual challenge, this advisory explores and explains the

cultural, community, and societal dynamics that drive connection and

disconnection. It also offers recommendations for increasing and

strengthening social connection through a whole-of-society approach.

The advisory presents a framework for a national strategy with specific

recommendations for the institutions that shape our day-to-day

lives: governments, health care systems and insurers, public health

departments, research institutions, philanthropy, schools, workplaces,

community-based organizations, technology companies, and the media.

This advisory draws upon decades of research from the scientific

disciplines of sociology, psychology, neuroscience, political science,

economics, and public health, among others. This document is not an

exhaustive review of the literature. Rather, the advisory was developed

through a substantial review of the available evidence, primarily found

via electronic searches of research articles published in English and

resources suggested by a wide range of subject matter experts, with

priority given to meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews. The

recommendations in the advisory draw upon the scientific literature and

previously published recommendations from the National Academies

of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, the American Heart Association, and the World

Health Organization.

The findings and recommendations in the advisory are also informed by

consultations with subject matter experts from academia, health care,

education, government, and other sectors of society, including more

than 50 identified experts who reviewed and provided individual detailed

feedback on an early draft that has informed this advisory.

For additional background and to read other Surgeon General’s

Advisories, visit SurgeonGeneral.gov

About the Advisory

LEARN MORE

Visit our website for more

information and resources

about social connection:

SurgeonGeneral.gov/Connection

7Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Belonging

A fundamental human need—the

feeling of deep connection with social

groups, physical places, and individual

and collective experiences.

5

Collective Efficacy

The willingness of community

members to act on behalf of

the common good of the group

or community

.

6

Empathy

The capability to understand and

feel the emotional states of others,

resulting in compassionate behavior.

7,8

Loneliness

A subjective distressing experience

that results from perceived

isolation or inadequate meaningful

connections, where inadequate refers

to the discrepancy or unmet need

between an individual’s preferred

and actual experience.

9,10

Norms of Reciprocity

A sense of reciprocal obligation that

is not only a transactional mutual

benefit but a generalized one; by

treating others well, we anticipate

that we will also be treated well.

11,12

Social Capital

The resources to which individuals

and groups have access through

their social connections.

13,14

The term

social capital is often used as an

umbrella for both social support

and social cohesion.

15

Social Cohesion

The sense of solidarity within

groups, marked by strong social

connections and high levels of social

participation, that generates trust,

norms of reciprocity, and a sense

of belonging.

13,15-18

Glossary

Social Connectedness

The degree to which any individual

or population might fall along the

continuum of achieving social

connection needs.

19

Social Connection

A continuum of the size and

diversity of one’s social network

and roles, the functions these

relationships serve, and their

positive or negative qualities.

10,19,20

Social Disconnection

Objective or subjective deficits in

social connection, including deficits

in relationships and roles, their

functions, and/or quality.

19

Social Infrastructure

The programs (such as volunteer

organizations, sports groups, religious

groups, and member associations),

policies (like public transportation,

housing, and education), and physical

elements of a community (such

as libraries, parks, green spaces,

and playgrounds) that support the

development of social connection.

Social Isolation

Objectively having few social

relationships, social roles, group

memberships, and infrequent

social interaction.

19,21

Social Negativity

The presence of harmful interactions

or relationships, rather than the

absence of desired social interactions

or relationships.

19,22

Social Networks

The individuals and groups a person is

connected to and the interconnections

among relationships. These “webs

of social connections” provide the

structure for various social connection

functions to potentially operate.

18,23

Social Norms

The unwritten rules that we follow

that serve as a social contract to

provide order and predictability

in society. The social groups we

belong to provide information and

expectations, and constraints on

what is acceptable and appropriate

behavior

.

24

Social norms reinforce

or discourage health-related and

risky behaviors (lifestyle factors,

vaccination, substance use, etc.).

25

Social Participation

A person’s involvement in activities

in the community or society that

provides interaction with others.

26,27

Social Support

The perceived or actual availability of

informational, tangible, and emotional

resources from others, commonly

one’s social network.

10,28

Solitude

A state of aloneness by choice that

does not involve feeling lonely.

Trust

An individual’s expectation of

positive intent and benevolence

from the actions of other people

and groups.

29-31

8Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Chapter 1

Overview

Introduction: Why Social Connection Matters

Our relationships and interactions with family, friends,

colleagues, and neighbors are just some of what create

social connection. Our connection with others and our

community is also informed by our neighborhoods, digital

environments, schools, and workplaces. Social connection—

the structure, function, and quality of our relationships

with others—is a critical and underappreciated contributor

to individual and population health, community safety,

resilience, and prosperity.

6,17,32-36

However, far too many

Americans lack social connection in one or more ways,

compromising these benefits and leading to poor health

and other negative outcomes.

People may lack social connection in a variety of ways, though it is often illustrated

in scientific research by measuring loneliness and social isolation. Social isolation

and loneliness are related, but they are not the same. Social isolation is objectively

having few social relationships, social roles, group memberships, and infrequent

social interaction.

19,21

On the other hand, loneliness is a subjective internal state.

It’s the distressing experience that results from perceived isolation or unmet need

between an individual’s preferred and actual experience.

9,10,19

The lack of social connection poses a significant risk for individual health and

longevity. Loneliness and social isolation increase the risk for premature death by

26% and 29% respectively.

37

More broadly, lacking social connection can increase

the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

4

In

addition, poor or insufficient social connection is associated with increased risk

of disease, including a 29% increased risk of heart disease and a 32% increased

risk of stroke.

38

Furthermore, it is associated with increased risk for anxiety,

depression,

39

and dementia.

40,41

Additionally, the lack of social connection may

increase susceptibility to viruses and respiratory illness.

42

KEY DATA

Lacking social connection

can increase the risk

for premature death as

much as smoking up to

15 cigarettes a day.

9Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

The lack of social connection can have significant economic costs to individuals,

communities, and society. Social isolation among older adults alone accounts

for an estimated $6.7 billion in excess Medicare spending annually, largely due

to increased hospital and nursing facility spending.

43

Moreover, beyond direct

health care spending, loneliness and isolation are associated with lower academic

achievement

44,45

and worse performance at work.

46-48

In the U.S., stress-related

absenteeism attributed to loneliness costs employers an estimated $154 billion

annually.

46

The impact of social connection not only affects individuals, but also

the communities they live in. Social connection is an important social determinant

of health, and more broadly, of community well-being, including (but not limited to)

population health, community resilience when natural hazards strike, community

safety, economic prosperity, and representative government.

13,15,17,34-36,49,50

What drives these profound health and well-being outcomes? Social connection

is a fundamental human need, as essential to survival as food, water, and shelter.

Throughout history, our ability to rely on one another has been crucial to survival.

Now, even in modern times, we human beings are biologically wired for social

connection. Our brains have adapted to expect proximity to others.

51,52

Our distant

ancestors relied on others to help them meet their basic needs. Living in isolation,

or outside the group, means having to fulfill the many difficult demands of survival

on one’s own. This requires far more effort and reduces one’s chances of survival.

52

Despite current advancements that now allow us to live without engaging with

others (e.g., food delivery, automation, remote entertainment), our biological need

to connect remains.

The health and societal impacts of social isolation and loneliness are a critical

public health concern in light of mounting evidence that millions of Americans lack

adequate social connection in one or more ways. A 2022 study found that when

people were asked how close they felt to others emotionally, only 39% of adults

in the U.S. said that they felt very connected to others.

53

An important indicator

of this declining social connection is an increase in the proportion of Americans

experiencing loneliness. Recent surveys have found that approximately half of

U.S. adults report experiencing loneliness, with some of the highest rates among

young adults.

1-3

These estimates and multiple other studies indicate that loneliness

and isolation are more widespread than many of the other major health issues of

our day, including smoking (12.5% of U.S. adults),

54

diabetes (14.7%),

55

and obesity

(41.9%),

56

and with comparable levels of risk to health and premature death.

Despite such high prevalence, less than 20% of individuals who often or always

feel lonely or isolated recognize it as a major problem.

57

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

KEY DATA

Approximately half of

U.S. adults report

experiencing loneliness,

with some of the highest

rates among young adults.

10Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Together, this represents an urgent public health concern. Every level of increase

in social connection corresponds with a risk reduction across many health

conditions. Further, social connection can be a proactive approach to living a

fulfilled and happy life, enhancing life satisfaction, educational attainment,

and performance in the workplace, as well as contributing to more-connected

communities that are healthier, safer, and more prosperous.

Unsurprisingly, social connection is generally not something we can do alone and

not something that is accessible equitably. That is partially because we need others

to connect with, but also because our society —including our schools, workplaces,

neighborhoods, public policies, and digital environments—plays a role in either

facilitating or hindering social connection.

10,32

Moreover, it is critical to carefully

consider equity in any approach to addressing social connection, as access and

barriers to social opportunities are often not the same for everyone and often

reinforce longstanding and historical inequities.

This advisory calls attention to the critical role that social connection plays in

individual and societal health and well-being and offers a framework for how we

can all contribute to advancing social connection.

What is Social Connection?

Social connection can encompass the interactions, relationships, roles, and

sense of connection individuals, communities, or society may experience.

10, ,2019

An individual’s level of social connection is not simply determined by the number

of close relationships they have. There are many ways we can connect socially,

and many ways we can lack social connection. These generally fall under one of

three vital components of social connection: structure, function, and quality.

• Structure

The number of relationships, variety of relationships (e.g., co-worker, friend,

family, neighbor), and the frequency of interactions with others.

• Function

The degree to which others can be relied upon for various needs.

• Quality

The degree to which relationships and interactions with others are positive,

helpful, or satisfying (vs. negative, unhelpful, or unsatisfying).

These three vital components of social connection are each important for

health,

4,32

and may influence health in different ways.

20

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

11Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

FIGURE 1: The Three Vital Components of Social Connection

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

The three Vital Components of Social Connection

The extent to which an individual is socially c

onnected depends on multiple factors, including:

Structure the number of variety of relationships and frequency of interactions

Examples

Household size

Friend circle siz

e

Martial/partnership status

Function the degree to which relationships serv

e various needs

Examples

Emotional support

Mentorship

Support in a crisis

Quality The positi

ve and

negative aspects of

relationships and

interactions

Examples

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship strain

Social inclusion or exclusion

Source Hot-Lunstad J. Why Social Relationships Are Important for Physical Health: A Systems Approach to Understanding and odifying Risk and Protection.

Annu Rev Psychol.2018;69:437-438

12Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

It’s also critical to understand other defining features of social connection.

First, it is a continuum. Too often, indicators of social connection or social

disconnection are considered in dichotomous ways (e.g., someone is lonely

or they’re not), but the evidence points more to a gradient.

58,59

Everyone falls

somewhere on the continuum of social connection, with low social connection

generally associated with poorer outcomes and higher social connection with

better outcomes.

59

Second, social connection is dynamic. The amount and quality of social connection

in our lives is not static. Social connectedness changes over time and can be

improved or compromised for a myriad of reasons. Illness, moves, job transitions,

and countless other life events, as well as changes in one’s community and society,

can all impact social connectedness in one direction or another. Further, how

long we remain on one end of the continuum may matter. Transient feelings of

loneliness may be less problematic, or even adaptive, because the distressing

feeling motivates us to reconnect socially.

60

Similarly, temporary experiences of

solitude may help us manage social demands.

61

However, chronic loneliness (even

if someone is not isolated) and isolation (even if someone is not lonely) represent

a significant health concern.

21, ,63 62

Third, much like the absence of disease does not equate to good health, the

absence of social deficits (e.g., loneliness) does not necessarily equate to high

levels of social connection. Although some measures of social connection

represent the full continuum, others only focus on deficits, which do not capture

the degree to which social assets may contribute to resilience, or even enable

thriving.

58

Consider two examples: first, an individual who is part of a large,

highly-involved family, and second, an individual who has regular contact with

colleagues through work but has little time for personal relationships outside of

work. In each case, such an individual is not objectively isolated and may not feel

subjectively lonely. However, in both cases key measures of isolation and loneliness

may miss whether they are reaping the benefits of social connection in other ways,

such as feeling adequately supported or having high-quality, close relationships.

Current Trends: Is Social Connection Declining?

Across many measures, Americans appear to be becoming less socially connected

over time.

12,64

This is not a new problem—certain declines have been occurring

for decades. While precise estimates of the rates of social connection nationally

can be challenging because studies vary based on which indicator is measured,

when the same measure is used at multiple time points, we can identify trends.

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

13Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Changes in key indicators, including individual social participation, demographics,

community involvement, and use of technology over time, suggest both overall

societal declines in social connection and that, currently, a significant portion of

Americans lack adequate social connection.

A fraying of the social fabric can also be seen more broadly in society. Trust

in each other and major institutions is at near historic lows.

65

Polls conducted

in 1972 showed that roughly 45% of Americans felt they could reliably trust

other Americans; however, that proportion shrank to roughly 30% in 2016.

66

This corresponds with levels of polarization being at near historic highs.

65,67

These phenomena combine to have widespread effects on society, including

many of the most pressing issues we face as a nation.

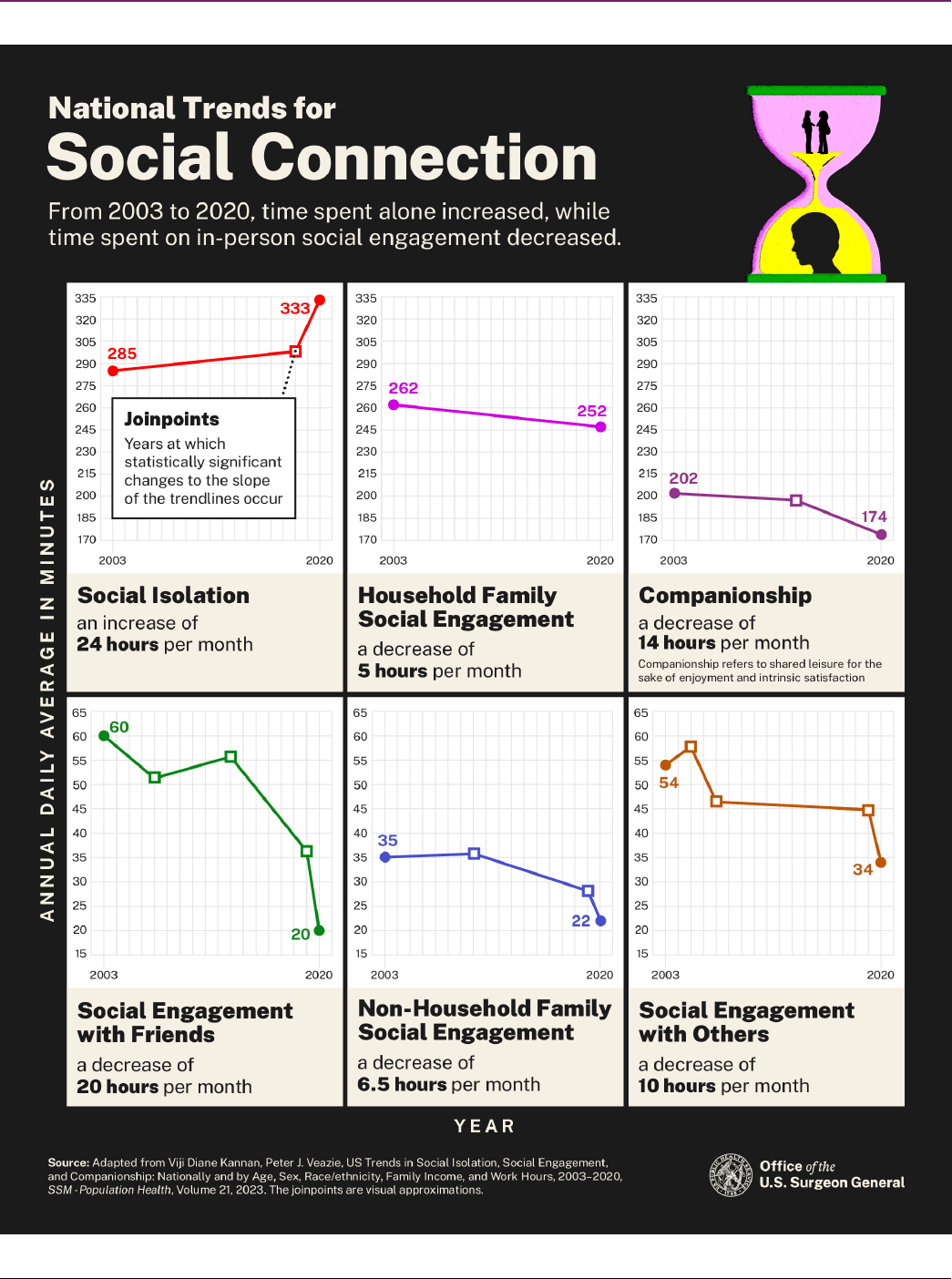

Trends in Social Networks and Social Participation

Social networks are getting smaller, and levels of social participation are declining

distinct from whether individuals report that they are lonely. For example, objective

measures of social exposure obtained from 2003-2020 find that social isolation,

measured by the average time spent alone, increased from 2003 (285-minutes/day,

142.5-hours/month) to 2019 (309-minutes/day, 154.5-hours/month) and continued

to increase in 2020 (333-minutes/day, 166.5-hours/month).

64

This represents an

increase of 24 hours per month spent alone. At the same time, social participation

across several types of relationships has steadily declined. For instance, the amount

of time respondents engaged with friends socially in-person decreased from 2003

(60-minutes/day, 30-hours/month) to 2020 (20-minutes/day, 10-hours/month).

64

This represents a decrease of 20 hours per month spent engaging with friends.

This decline is starkest for young people ages 15 to 24. For this age group, time

spent in-person with friends has reduced by nearly 70% over almost two decades,

from roughly 150 minutes per day in 2003 to 40 minutes per day in 2020.

64

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated trends in declining social participation.

The number of close friendships has also declined over several decades.

Among people not reporting loneliness or social isolation, nearly 90% have three

or more confidants.

57

Yet, almost half of Americans (49%) in 2021 reported having

three or fewer close friends —only about a quarter (27%) reported the same in

1990.

68

Social connection continued to decline during the COVID-19 pandemic,

with one study finding a 16% decrease in network size from June 2019 to June 2020

among participants.

69

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

KEY DATA

Polls conducted in 1972

showed that roughly 45%

of Americans felt they

could reliably trust other

Americans; however,

that proportion shrank

to roughly 30% in 2016.

14Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

FIGURE 2: National Trends for Social Connection

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

National Trends for Social Connection

From 2003 to 2020, time spent alone increased, while time spent on in-person social engagement decreased.

Social

Isolation

an

increase of

24 hours

per month

from 285

to 333

Household

Family

Social

Engagement

a decrease

of 5 hours

per month

from 262 to

2

5

2

Companio

nship a

decrease

of 14

hours per

month

companio

nship

refers to

shared

leisure for

the sake

of

enjoymen

t and

intrinsic

satisfactio

n from

202 to 174

Social

Engage

m

nte with

Friends

a decreas

e of 20

hours

pmeor nth

f6r0o to 20

Non-

household

Family

Social

Engagement

decrease of

6.5 hours

per month

from 35 to

22

Social

Engagement

with others

a decrease

of 10 hours

per

month

from

54 to 34

w

Source: Adapted from Viji Diane Kannan, Peter J. Veazie, US Trends in Social Isolation, Social Engagement, and Companionship: Nationally and by Age, Sex, Race/ethnicity, Family Income, and Work

Hours, 2003-2020, SSM-Population Health, Volume 21, 2023. The joinpoints are visual approximations. Office of the U.S. Surgeon General

15Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

Demographic Trends

Societal trends, including demographic changes such as age, marital/partnership

status, and household size, also provide clues to current trends. For example,

family size and marriage rates have been in steady decline for decades.

70

The percentage of Americans living alone has also increased decade-to-decade.

In 1960, single-person households accounted for only 13% of all U.S. households.

70

In 2022, that number more than doubled, to 29% of all households.

70

The reasons people choose to remain single or unmarried, have smaller families,

and live alone over time are complex and encompass many factors. Yet at the same

time, it is important to acknowledge the contribution these demographic changes

have on social disconnection because of the significant health impacts identified

in the scientific evidence. Moreover, awareness can help individuals consider these

impacts and cultivate ways to foster sufficient social connection outside of chosen

traditional means and structures.

The research in this section points to overall declines in some of the critical

structural elements of social connection (e.g., marital status, household size),

which helps to explain increases in reported loneliness and social isolation and

contributes to the overall crisis of connection we are experiencing. Finally, this

suggests we have fewer informal supports to draw upon in times of need—all while

the number of older individuals and those living with chronic conditions continues

to increase.

Awareness can help individuals

consider these impacts and cultivate

ways to foster sufficient social

connection outside of chosen

traditional means and structures.

KEY DATA

In 1960, single-person

households accounted

for only 13% of all U.S.

households. In 2022, that

number more than doubled,

to 29% of all households.

16Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Trends in Community Involvement

Although the concept of community has evolved over time, many traditional

indicators of community involvement, including with religious groups, clubs,

and labor unions, show declining trends in the United States since at least the

1970s.

12,71

In 2018, only 16% of Americans reported that they felt very attached

to their local community.

72

Membership in organizations that have been important pillars of community

connection have declined significantly in this time. Take faith organizations, for

example. Research produced by Gallup, Pew Research Center, and the National

Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey demonstrates that since the

1970s, religious preference, affiliation, and participation among U.S. adults have

declined.

73-75

In 2020, only 47% of Americans said they belonged to a church,

synagogue, or mosque. This is down from 70% in 1999 and represents a dip

below 50% for the first time in the history of the survey question.

75

Religious

or faith-based groups can be a source for regular social contact, serve as a

community of support, provide meaning and purpose, create a sense of belonging

around shared values and beliefs, and are associated with reduced risk-taking

behaviors.

76-78

As a consequence of this decline in participation, individuals’ health

may be undermined in different ways.

16

What Leads Us to Be More or Less Socially Connected?

A wide variety of factors can influence an individual or community’s level of social

connection. One organizing tool that helps us better understand these factors is

the social-ecological model.

79,80

This model organizes the interrelated factors that

affect health on the individual level, in our relationships, in our communities, and

in society. Each of these levels—from the smallest to the broadest—contribute to

social connection and its associated risks and protection for health.

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

16

KEY DAT

%

A

In 2018, only 16% of

Americans reported

that they felt very

attached to their

local community.

17Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

FIGURE 3: Factors That Can Shape Social Connection

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

Factors That Can

Shape Social Connection

Individual

• Chronic disease

• Sensory and functional impairments

• Mental health

• Physical health

• Personality

• Race

• Gender

• Socioeconomic st

atus

• Life stage

Relationships

• Structure, function, and

quality

• Household size

• Characteristics and

behaviors of others

• Empathy

Community

• Outdoor space

• Housing

• Schools

• Workplace

• Local government

• Local business

• Community organiz

ations

• Health care

• Transportation

Society

• Norms and values

• Public policies

• Tech environment and use

• Civic engagement

• Democratic norms

• Historical inequities

18Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

Social connection is most often viewed as driven by the individual —one’s genetics,

health, socioeconomic status, race, gender, age, household living situation, and

personality, among other factors. These can influence motivation, ability, or access

to connect socially. As we’ve seen, the level of one’s connection is also dependent

on the structure, function, and quality of relationships. However, connectedness is

influenced by more than simply personal or interpersonal factors. It is also shaped

by the social infrastructure of the community (or communities) in which one is born,

grows up, learns, plays, works, and ages.

Social infrastructure includes the physical assets of a community (such as libraries

and parks), programs (such as volunteer organizations and member associations),

and local policies (such as public transportation and housing) that support the

development of social connection.

The social infrastructure of these communities is in turn influenced by broader

social policies, cultural norms, the technology environment, the political

environment, and macroeconomic factors. Moreover, individuals are simultaneously

influenced by societal-level conditions such as cooperation, discrimination,

inequality, and the collective social connectedness or disconnectedness of the

community.

23

All of these shape the availability of opportunities for social connection.

In sum, social connection is more than a personal issue. The structural and social

characteristics of the community produce the settings in which people build,

maintain, and grow their social networks.

36,81,82

Because many contributors to social

connection go beyond an individual’s control, in order to promote health, change

is needed across the full scope of the social-ecological model. While every factor

listed in Figure 3, as well as some not captured, can be important contributors to

social connection, it’s important to look across these levels. That gives us clues

to barriers to connection and the types of interventions which could successfully

increase social connection. This broader view can also help identify what places

groups at highest risk for social isolation and loneliness, as well as factors that

reinforce cycles of risk or resilience.

…in order to promote health, change

is needed across the full scope of the

social-ecological model.

19Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

Groups at Highest Risk for Social Disconnection

Anyone of any age or background can experience loneliness and isolation, but some

groups are at higher risk than others. Not all individuals or groups experience the

factors that facilitate or become barriers to social connection equally. Some people

or groups are exposed to greater barriers. It’s critical to examine and highlight the

disproportionate risk they face and to target interventions to address their needs.

Although risk may differ across indicators of social disconnection, currently,

studies find the highest prevalence for loneliness and isolation among people with

poor physical or mental health, disabilities, financial insecurity, those who live

alone, single parents, as well as younger and older populations.

1, ,

For example,

while the highest rates of social isolation are found among older adults,

8364

64

young

adults are almost twice as likely to report feeling lonely than those over 65.

1

The rate of loneliness among young adults has increased every year between 1976

and 2019.

84

In addition, lower-income adults are more likely to be lonely than those

with higher incomes. Sixty-three percent of adults who earn less than $50,000

per year are considered lonely, which is 10 percentage points higher than those

who earn more than $50,000 per year.

1

These data do not suggest that individual

or demographic factors inherently generate loneliness or isolation. Rather, the

data enable us to understand the different socioeconomic, political, and cultural

mechanisms that may indicate higher risk for certain groups and lead to loneliness

and isolation.

Additional at-risk groups may include individuals from ethnic and racial minority

groups, LGBTQ+ individuals, rural residents, victims of domestic violence, and

those who experience discrimination or marginalization. Further research is needed

to fully understand the disproportionate impacts of social disconnection.

Impacts of Technology on Social Connection

There is more and more evidence pointing to the importance of our environments

for health, and the same is true for digital environments and our social health.

A variety of technologies have quickly and dramatically changed how we live,

work, communicate, and socialize. These technologies include social media,

smartphones, virtual reality, remote work, artificial intelligence, and assistive

technologies, to name just a few.

These technologies are pervasive in our lives. Nearly all teens and adults under

65 (96-99%), and 75% of adults 65 and over, say that they use the internet.

85

Americans spend an average of six hours per day on digital media.

86

One-in-three

U.S. adults 18 and over report that they are online “almost constantly,”

87

and

KEY DATA

The rate of loneliness

among young adults has

increased every year

between 1976 and 2019.

20Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

the percentage of teens ages 13 to 17 years who say they are online “almost

constantly” has doubled since 2015.

88

When looking at social media specifically,

the percentage of U.S. adults 18 and over who reported using social media

increased from 5% in 2005 to roughly 80% in 2019.

89

Among teens ages 13 to 17

years, 95% report using social media as of 2022, with more than half reporting it

would be hard to give up social media.

88

Although tech adoption is relatively high

among all groups, Americans with disabilities,

90

adults with lower incomes,

91

and

Americans from rural areas

92

continue to experience a persistent, albeit shrinking,

digital divide. They are relatively less likely to own a computer, smartphone,

or tablet, or have broadband internet access.

90-92

Technology has evolved rapidly, and the evidence around its impact on our

relationships has been complex. Each type of technology, the way in which

it is used, and the characteristics of who is using it, needs to be considered

when determining how it may contribute to greater or reduced risk for social

disconnection. There are multiple meta-analyses

93-96

and reviews

97-105

examining

this topic that identify both benefits and harms.

Several examples of benefits include technology that can foster connection

by providing opportunities to stay in touch with friends and family, offering

other routes for social participation for those with disabilities, and creating

opportunities to find community, especially for those from marginalized

groups.

97,106-108

For example, online support groups allow individuals to share their

personal experiences and to seek, receive, and provide social support—including

information, advice, and emotional support.

95,104

Several examples of harms include technology that displaces in-person

engagement, monopolizes our attention, reduces the quality of our interactions,

and even diminishes our self-esteem.

97, ,110109

This can lead to greater loneliness,

fear of missing out, conflict, and reduced social connection. For example, frequent

phone use during face-to-face interactions between parents and children, and

between family and friends, increased distraction, reduced conversation quality,

and lowered self-reported enjoyment of time spent together in-person.

111-113

In a

U.S.-based study, participants who reported using social media for more than

two hours a day had about double the odds of reporting increased perceptions of

social isolation compared to those who used social media for less than 30 minutes

per day.

114

Additionally, targets of online harassment report feelings of increased

loneliness, isolation, and relationship problems, as well as lower self-esteem

and trust in others.

115

Evidence shows that even perpetrators of cyberbullying

experience weakened emotional bonds with social contacts and deficits in

perceived belongingness.

115

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

KEY DATA

In a U.S.-based study,

participants who reported

using social media for

more than two hours a

day had about double

the odds of reporting

increased perceptions of

social isolation compared

to those who used social

media for less than

30 minutes per day.

21Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

Understanding how technology can enhance or detract from social connection is

complicated by ever-changing social media algorithms, complex differences in

individual technology use, and balancing concerns over obtaining private user data.

Advancing research in this area is essential. With that said, the existing evidence

illustrates that we have reason to be concerned about the impact of some kinds of

technology use on our relationships, our degree of social connection, and our health.

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

…the existing evidence illustrates

that we have reason to be concerned

about the impact of some kinds of

technology use on our relationships,

our degree of social connection,

and our health.

Risk and Resilience Can Be Reinforcing

The factors that facilitate, or become barriers to, social connection can also

reinforce either a virtuous or vicious cycle.

116

Economic status, health, and service

are just a few illustrative examples—better social connection can lead to better

health, whereas less social connection can lead to poorer health. However, each of

these can be reinforcing. Being in poorer health can become a barrier to engaging

socially, reducing social opportunities and support, and reinforcing a vicious

cycle of poorer health and less connection.

117-119

A similar kind of pattern could

occur among those struggling financially. For example, financial insecurity may

require someone to work multiple jobs, resulting in less leisure time and limiting

opportunities for social participation and connection—which, in turn, could provide

fewer resources and financial opportunities. While these cycles can be reinforcing,

they are not always negative. There is, for instance, a virtuous cycle between

social connection and volunteerism or service. Those who are more connected

to their communities are more likely to engage in service, and those who are

engaged in service are more likely to feel connected to their communities and the

individuals in it.

120

Interestingly, there is also evidence showing that the well-being

benefits associated with volunteering are even greater for those with higher social

connectedness than those with less.

121

Because these cycles can be reinforcing,

prioritizing social connection can not only disrupt vicious cycles but also reinforce

virtuous ones.

22Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

While social connection had been declining for

decades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the onset of

the pandemic, with its lockdowns and stay-at-home

orders, was a critical time during which the issue

of connection came to the forefront of public

consciousness, raising awareness about this critical

and ongoing public health concern.

Many of us felt lonely or isolated in a way we had

never experienced before. We postponed or canceled

meaningful life moments and celebrations like

birthdays, graduations, and marriages. Children’s

education shifted online—and they missed out on the

many benefits of interacting with their friends. Many

people lost jobs and homes. We were unable to visit our

children, siblings, parents, or grandparents. Many lost

loved ones. We experienced feelings of anxiety, stress,

fear, sadness, grief, anger, and pain through the loss of

these moments, rituals, celebrations, and relationships.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic was a collective

experience, it impacted certain populations differently.

Frontline workers had a different experience than

those who could work from home. Parents managing

their own work and their children’s online school had a

different experience than single young people unable

to interact in-person with friends. And those at greater

risk of severe COVID-19, including older individuals,

those living in nursing homes, and people with

underlying health conditions, faced unique challenges.

Emerging data suggests that people with close and

CALL OUT BOX

Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

positive familial connections may have had a different

experience than those without. A recent national

survey showed that, by April 2021, 1 in 4 individuals

reported feeling less close to family members

compared to the beginning of the pandemic.

122

Yet, at the same time, about 1 in 5 said they felt closer

to family members,

122

perhaps indicating that the

pandemic exacerbated existing family dynamics of

connection or disconnection.

We also witnessed first responders, health care

workers, community members, neighbors, and

volunteers stepping up and offering their social

support to one another. Service can be a powerful

source of connection. From September 2020 to

September 2021, the majority (51%) of U.S. individuals

ages 16 and older reported informally helping

others.

123

This represents more than 120 million

U.S. individuals helping informally, in addition to an

estimated 60 million individuals formally volunteering

through an organization during the same period.

123

By engaging in service work, many were able to find

and create pockets of connection for themselves and

others during a public health crisis.

While profoundly disruptive in so many ways, the

COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to reflect

more deeply on the state of social connection in our

lives and in society. As we emerge from this era,

rebuilding social connection and community offers

us a promising and hopeful way forward.

CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW

23Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

How Social Connection

Impacts Individual

Health and Well-Being

Chapter 2

Extensive scientific findings from a variety of disciplines,

including epidemiology, neuroscience, medicine,

psychology, and sociology, converge on the same

conclusion: social connection is a significant predictor

of longevity and better physical, cognitive, and mental

health, while social isolation and loneliness are significant

predictors of premature death and poor health.

10, , ,1243220

In fact, the benefits of social connection extend beyond

health-related outcomes. They influence an individual’s

educational attainment, workplace satisfaction, economic

prosperity, and overall feelings of well-being and life

fulfillment. This chapter summarizes the rapidly growing

body of evidence on the relationship between various

indicators of social connection and these outcomes

for individuals.

24Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

Individual Health Outcomes

Survival and Mortality

“Over four decades of research has produced

robust evidence that lacking social connection—

and in particular, scoring high on measures of

social isolation—is associated with a significantly

increased risk for early death from all causes.”

10

2020 Consensus Study Report,

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine

Evidence across scientific disciplines converges on the conclusion that socially

connected people live longer. Large population studies have documented that,

among initially healthy people tracked over time, those who are more socially

connected live longer, while those who experience social deficits, including

isolation, loneliness, and poor-quality relationships, are more likely to die earlier,

regardless of the cause of death.

37,125-128

Systematic research demonstrating

the link between social connection and mortality risk dates to one of the first

large-scale longitudinal epidemiological studies conducted in 1979.

129

This

research found that people who lacked social connection were more than twice

as likely than those with greater social connection to die within the follow-up

period, even after accounting for age, health status, socioeconomic status,

and health practices.

129

More recent estimates, based on synthesizing data across 148 studies, with an

average of 7.5 years of follow-up, suggest that social connection increases the

odds of survival by 50%.

128

Indeed, the effects of social connection, isolation, and

loneliness on mortality are comparable, and in some cases greater, than those of

many other risk factors (see Figure 4) including lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking,

alcohol consumption, physical inactivity), traditional clinical risks factors (e.g.,

high blood pressure, body mass index, cholesterol levels), environmental factors

(e.g., air pollution), and clinical interventions (e.g., flu vaccine, high blood pressure

medication, rehabilitation).

128,130

5

KEY D

0%

ATA

Data across 148 studies,

with an average of 7.5 years

of follow-up, suggest that

social connection increases

the odds of survival by 50%.

25Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

FIGURE 4: Lacking social connection is as dangerous as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

Over the years, the number of studies, the rigor of their methods, and the size of

the samples have all increased substantially, providing stronger confidence in this

evidence. These replicate the finding that social connection decreases the risk of

premature death.

Taken together, this research establishes that the lack of social connection is

an independent risk factor for deaths from all causes, including deaths caused

by diseases.

131

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

Lacking social connection is as dangerous as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

Lacking Social Connection has the highest

odds of Premature Mortality

Followed by Smoking up to 15 cigarettes

daily

Followed by Drinking 6 alcoholic drinks

daily

Followed by Physical inactivity

Followed by Obesity

Followed by Air pollution

Source: Holt-Lunstad J. Robles TF, Sbarra

DA. Advancing So

cial Connection as a Public

Health Priority in the United States.

American Psycholo

gy. 2017;72(6):517-530.

doi:10,1037/amp0000103. This graph is a

visual approximation.

Office of the U.S. Surgeon General

26Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

Cardiovascular Disease

The evidence linking social connection to physical health is strongest in heart

disease and stroke outcomes.

10,58

Dozens of studies have found that social

isolation and loneliness significantly increase the risk of morbidities from these

conditions.

10, ,133132

Among this evidence, a synthesis of data across 16 independent

longitudinal studies shows poor social relationships (social isolation, poor social

support, loneliness) were associated with a 29% increase in the risk of heart

disease and a 32% increase in the risk of stroke.

38

Interestingly, these effects

can begin early in life and stretch over a lifetime. Research has also found that

childhood social isolation is associated with increased cardiovascular risk factors

such as obesity, high blood pressure, and blood glucose levels in adulthood.

133-135

Further, in a 2022 statement, the American Heart Association concluded that

“social isolation and loneliness are common, yet underrecognized, determinants

of cardiovascular health and brain health.”

133

Heart failure patients who reported high levels of loneliness had a 68% increased

risk of hospitalization, a 57% higher risk of emergency department visits, and

a 26% increased risk of outpatient visits, compared with patients reporting low

levels of loneliness.

136

Combining data from 13 studies on heart failure patients,

researchers found that poor social connection is associated with a 55% greater

risk of hospital readmission.

137

This was consistent across both objective and

perceived social isolation, including living alone, lack of social support, and poor

social network. Furthermore, evidence suggests that people who are less socially

connected, particularly those living alone, may be less likely to make it to the

hospital, increasing their risk of dying from a cardiac event.

138

Conversely, a heart

attack is less likely to be fatal for people living with others or who have more social

contacts, perhaps because of the immediate response and availability of help

during the event.

138

Hypertension

High blood pressure (hypertension) is one of the leading causes of cardiovascular

disease.

139

Several studies demonstrate that the more social support one has, the

greater the reduction in the possibility of developing high blood pressure, even

in populations who are at higher risk for the condition, such as Black Americans.

Greater social support in this group is associated with a 36% lower risk of high

blood pressure in the long-term.

140

Among older adults, the effect of social isolation

on hypertension risk is even greater than that of other major clinical risk factors

such as diabetes.

59

KEY DATA

A synthesis of data

across 16 independent

longitudinal studies shows

poor social relationships

(social isolation, poor

social support, loneliness)

were associated with a

29% increase in the risk

of heart disease and a

32% increase in the risk

of stroke.

27Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

Since high blood pressure most often doesn’t have symptoms, it is possible for

people to be unaware of even severe underlying cases.

141

The disorder may remain

undiagnosed for years, which can elevate the risk for a wide range of physiological

complications.

141

However, among older adults, people with higher perceived

emotional support from family and friends, and with frequent exposure to

health-related information within their social networks, are significantly less

likely to have undiagnosed and uncontrolled hypertension.

142

The results of many research studies also reflect a strong correlation between

social connection and high blood pressure control. Regular participation in two or

more social or community-based groups

143

; emotional and informational support

from family, friends, professional contacts, community organizations, and peer

groups

144-146

; and frequent network interactions

142

may improve hypertension

management, including following treatment recommendations and long-term

lifestyle adjustments. Findings from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging

Project (NSHAP) suggest a “causal role of social connections in reducing

hypertension,” particularly in adults over the age of 50.

59

Diabetes

Evidence gathered over the last 25 years has demonstrated that social context

is important to the development and management of diabetes.

147

Population-based

studies show the impact of social connection on the development of type 2

diabetes and diabetic complications.

148,149

For example, social disconnection

(poor structural social support

150

and living alone

151

in men, low emotional support

in women,

152

and not having a current partner in women older than 70

153

) has been

linked to an increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes. Furthermore,

living alone increased the risk of developing type 2 diabetes among women with

impaired glucose tolerance.

154

By contrast, social connection has been associated with better self-rated health

and disease management among individuals with diabetes.

155-157

The involvement

and support of family members has also been repeatedly shown to improve disease

management and the health of people with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes.

147

Whereas, smaller social network size has been associated with newly diagnosed

type 2 diabetes and complications from diabetes.

148,149

These associations between

social connection and broader diabetic outcomes including diagnosed pre-diabetes

and type 2 diabetes, macrovascular complications (e.g., heart attack, stroke) and

microvascular complications (e.g., diabetic retinopathy, impaired sensitivity in

the feet, and signs of kidney disease) were independent of blood sugar (glucose)

control, quality of life, and other cardiac risk factors.

148,149

KEY DATA

The involvement and

support of family members

has been repeatedly

shown to improve disease

management and the

health of people with

type 1 diabetes and

type 2 diabetes.

28Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

What explains this phenomenon? Diabetic outcomes may be better among people

who are more socially connected due to better diabetic management behaviors

and patient self-care such as medication adherence, physical activity, diet, and

foot care. For example, in a meta-analysis of 28 studies, social support from

family and friends was significantly associated with better self-care, particularly

blood sugar monitoring.

158

Finally, evidence from the National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey found that among older adults with diabetes, those with

a large social support network size (at least six close friends) had a reduced risk

of all-cause mortality.

159

Infectious Diseases

People who are less socially connected may have increased susceptibility and

weaker immune responses when they are exposed to infectious diseases. In a

series of studies examining factors that contribute to illness after exposure to

viruses like the common cold and flu, loneliness and poor social support were

found to significantly contribute to the development and severity of the illnesses.

42,160

In one study where participants were exposed to a common cold virus, individuals

with social ties to six or more diverse social roles (e.g., parent, spouse, friend,

family, co-worker, group membership) had a four-fold lower risk of developing a

cold when compared to people who had ties to fewer (1-3) diverse social roles.

161

These effects cannot be explained by previous exposure, since those who are

more socially connected have stronger immune responses independent of baseline

antibody count—suggesting stronger immune responses even when exposed to

new viruses.

42

A study conducted on immune responses to the COVID-19 vaccine

found that a lack of social connection with neighbors and resultant loneliness was

associated with weaker antibody responses to the vaccine.

162

Cognitive Function

Substantial evidence also links social isolation and loneliness with accelerated

cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia in older adults,

10,41

including

Alzheimer’s disease.

163

Chronic loneliness and social isolation can increase the

risk of developing dementia by approximately 50% in older adults, even after

controlling for demographics and health status.

41

A study that followed older adults

over 12 years found that cognitive abilities declined 20% faster among those who

reported loneliness.

164

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

5

KEY D

0%

ATA

Chronic loneliness and

social isolation can

increase the risk of

developing dementia

by approximately 50%

in older adults.

29Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

When taken together, this evidence consistently shows that wider social networks

and more frequent social engagements with friends and family are associated with

better cognitive function and may protect against the risk of dementia.

40,165

This suggests that investments in social connection may be an important public

health response to cognitive decline.

Depression and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety are often characterized by social withdrawal, which

increases the risk for both social isolation and loneliness; however, social isolation

and loneliness also predict increased risk for developing depression and anxiety

and can worsen these conditions over time. A systematic review of multiple

longitudinal studies found that the odds of developing depression in adults is more

than double among people who report feeling lonely often, compared to those who

rarely or never feel lonely.

39

Furthermore, in older adults, both social isolation and

loneliness have been shown to independently increase the likelihood of depression

or anxiety.

166

These findings are also consistent among younger people. A review

of 63 studies concluded that loneliness and social isolation among children and

adolescents increase the risk of depression and anxiety, and that this risk remained

high even up to nine years later.

167

Importantly, social connection also seems to protect against depression even

in people with a higher probability of developing the condition. For example,

frequently confiding in others is associated with up to 15% reduced odds of

developing depression among people who are already at higher risk due to their

history of traumatic or otherwise adverse life experiences.

168

Suicidality and Self-Harm

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

KEY DATA

Loneliness and social

isolation among children

and adolescents

increase the risk of

depression and anxiety.

“Social isolation is arguably the strongest and most

reliable predictor of suicidal ideation, attempts, and

lethal suicidal behavior among samples varying in

age, nationality, and clinical severity.”

169

2010 Study, “The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide”

While many factors may contribute to suicide, more than a century of research has

demonstrated significant links between a lack of social connection and death by

suicide. This research suggests that social connection may protect against suicide

as a cause of death, especially for men.

30Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

One study found that among men, deaths due to suicide are associated with

loneliness and more strongly with indicators of objective isolation such as living

alone.

170

In this study of over 500,000 middle-aged adults, the probability of

dying by suicide more than doubled among men who lived alone. The same study

showed that for women loneliness was significantly associated with hospitalization

for self-harm.

170

Further, when examining suicidality among nursing home and

other long-term care facility residents,

171

cancer patients,

172

older adults,

173

and

adolescents,

174

systematic reviews of studies on loneliness, social isolation, and low

social support were associated with suicidal ideation. These links may result from

a low sense of belonging and perceiving oneself as a burden to others.

169

Loneliness and low social support are also associated with increased risk of

self-harm. In a review of 40 studies of more than 60,000 older adults, an increase

in loneliness was reported to be among the primary motivations for self-harm.

175

Given the totality of the evidence, social connection may be one of the strongest

protective factors against self-harm and suicide among people with and without

serious underlying mental health challenges.

Social Connection Influences Health

Through Multiple Pathways

While the effects of social connection on health are clear, research also helps

explain how our level of social connection ultimately results in better or worse

health. A key part of the explanation involves understanding how social connection

influences behavioral, biological, and psychological processes, which in turn

influence health outcomes. A large body of evidence has identified several

plausible pathways (see Figure 5).

59,176-180

31Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

FIGURE 5: How Does Social Connection Influence Health?

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

How Does Social Connection Influence Health?

Social connection influences health through three principal pathways: biology, psychology, and behavior.

Components

Social Connection

Processes

Biology Stress Hormones, Inflammation, Gene Expression

Psychology Meaning/Purpose, Stress, Safety, Resilience,

Hopefulness

Behaviors Physical Activity, Nutrition,

Sleep, Smoking Treatment

Outcomes

Health Outcomes such as heart disease,

stroke, and diabetes can lead to an

individual's morbidity and premature

mortality.

Source: Holt-Lundtad J. The Major Health Implications of Social Connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2021;30(3):251-259. Office of the U.S. Surgeon General

32Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

CHAPTER 2: INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

Social Connection Influences Biological Processes

The role of social connection on biology emerges early in life and continues

across the life course, contributing to risk and protection from disease.

59

Several

reviews document that social connection can influence health through specific

biological pathways, including cardiovascular and neuroendocrine dysregulation,

181

immunity,

42,177,182-184

and gut-microbiome interactions.

185,186

Because regulation of

these systems is critical for good health, the documented influence between social

connection and these biological pathways likely explains the impact on the risk of

the development of disease.

Biological systems often do not operate independently. This means that increases

in blood pressure, circulating stress hormones, and inflammation may occur

simultaneously, potentially compounding risk across several biological systems.

187

One biological pathway of great interest is inflammation, given that it has been

implicated as a factor in many chronic illnesses.

188

Evidence shows that being

objectively isolated, or even the perception of isolation, can increase inflammation

to the same degree as physical inactivity.

59

Similarly, lower social support is

associated with higher inflammation.

189,190

Chronic inflammation throughout the

body has been linked to various chronic illnesses across the lifespan, such as

cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease,

as well as a variety of mental, cognitive, and physical health outcomes

188,191

that