Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

1

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 18 (Autumn 2020)

Contents

EDITORIAL p. 5

Statement re: Issue #12 (2013) p. 6

ARTICLES

‘Do you all want to die? We must throw them out!’: Class Warfare, Capitalism, and

Necropolitics in Seoul Station and Train to Busan

Jessica Ruth Austin p. 7

Maternal Femininity, Masquerade, and the Sacrificial Body in Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya,

or The Moor

Reema Barlaskar p. 30

The Thing in the Ice: The Weird in John Carpenter’s The Thing

Michael Brown p. 47

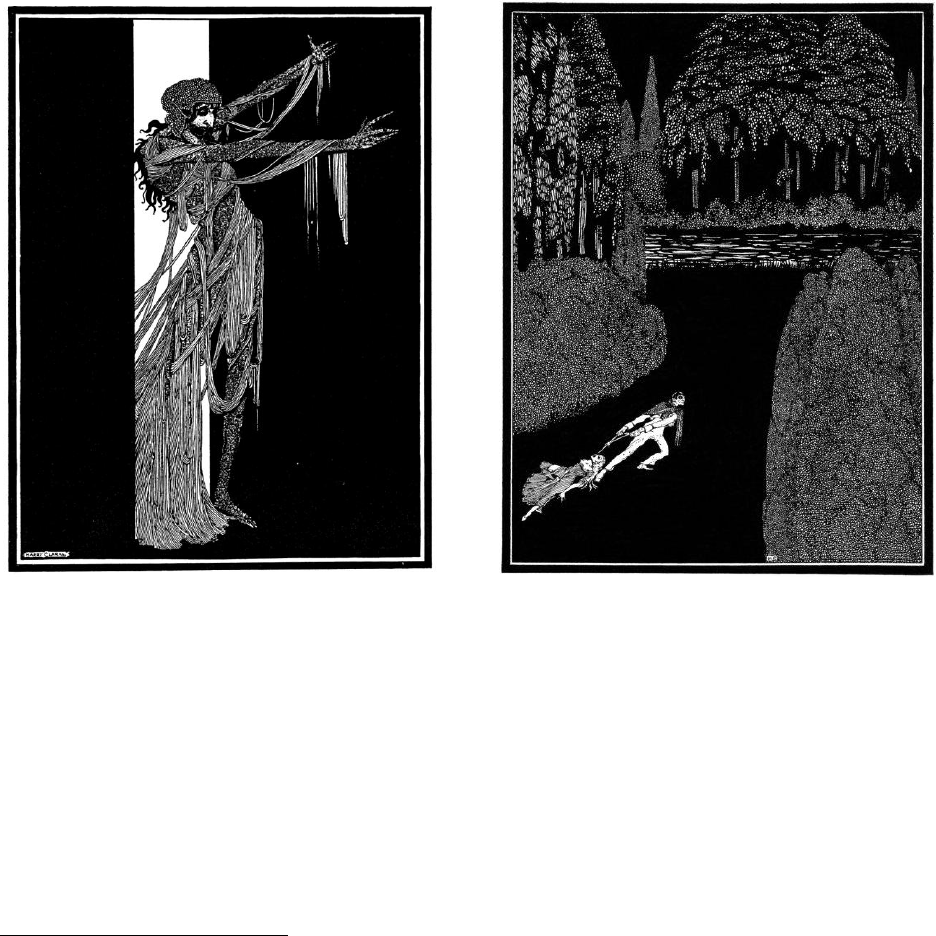

Harry Clarke, the Master of the Macabre

Marguerite Helmers p. 77

Gods of the Real: Lovecraftian Horror and Dialectical Materialism

Sebastian Schuller p. 100

Virgins and Vampires: The Expansion of Gothic Subversion in Jean Rollin’s Female

Transgressors

Virginie Sélavy p. 121

BOOK REVIEWS: LITERARY AND CULTURAL CRITICISM

B-Movie Gothic, ed. by Justin D. Edwards and Johan Höglund

Anthony Ballas p. 146

Werewolves, Wolves, and the Gothic, ed. by Robert McKay and John Miller

Rebecca Bruce p. 151

Jordan Peele’s Get Out: Political Horror, ed. by Dawn Keetley

Miranda Corcoran p. 155

Rikke Schubart, Mastering Fear: Women, Emotions, and Contemporary Horror

Miranda Corcoran p. 161

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

2

Posthuman Gothic, ed. by Anya Heise-von der Lippe

Matthew Fogarty p. 165

Jessica Balanzategui, The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema: Ghosts of Futurity at the

Turn of the Twenty-First Century

Jessica Gildersleeve p. 168

Neo-Victorian Villains: Adaptations and Transformations in Popular Culture, ed. by

Benjamin Poore

Madelon Hoedt p. 172

William Hughes, Key Concepts in the Gothic

Kathleen Hudson p. 176

Murray Leeder, Horror Film: A Critical Introduction

Kathleen Hudson p. 179

Dracula: An International Perspective, ed. by Marius-Mircea Crişan

Giorgia Hunt p. 183

Darryl Jones, Sleeping with the Lights On: The Unsettling Story of Horror

Laura R. Kremmel p. 186

Kyna B. Morgan, Woke Horror: Sociopolitics, Genre, and Blackness in Get Out

Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet p. 189

The Cambridge Companion to Dracula, ed. by Roger Luckhurst

Christina Morin p. 192

Yael Shapira, Inventing the Gothic Corpse: The Thrill of Human Remains in the Eighteenth-

Century Novel

Christina Morin p. 196

Rebecca Duncan, South African Gothic: Anxiety and Creative Dissent in the Post-Apartheid

Imagination and Beyond

Antonio Sanna p. 199

James Machin, Weird Fiction in Britain 1880-1939

John Sears p. 202

Bryan Hall, An Ethical Guidebook to the Zombie Apocalypse: How to Keep Your Brain

Without Losing Your Heart

Tait C. Szabo p. 205

Howard David Ingham, We Don’t Go Back: A Watcher’s Guide to Folk Horror

Richard Gough Thomas p. 208

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

3

BOOK REVIEWS: FICTION

The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories, ed. by A. Worth

Erin Corderoy p. 211

William Orem, Miss Lucy; and Dacre Stoker and J. D. Barker, Dracul

Ruth Doherty p. 215

Doorway to Dilemma: Bewildering Tales of Dark Fantasy, ed. by Mike Ashley

Murray Leeder p. 218

The Pit and the Pendulum and Other Tales, ed. by David Van Leer

Elizabeth Mannion p. 220

BOOKS RECEIVED p. 223

TELEVISION AND PODCAST REVIEWS

Dark, Seasons 1-3

Taghreed Alotaibi p. 225

Forest 404

Elizabeth Parker p. 228

The Purge

Thomas Sweet p. 231

Siempre Bruja/Always a Witch, Seasons 1 and 2

Rebecca Wynne-Walsh p. 236

The Order, Seasons 1 and 2

Rebecca Wynne-Walsh p. 241

FILM REVIEWS

Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror

Sarah Cullen p. 245

Overlord

Kevin M. Flanagan p. 249

Halloween

Gerard Gibson p. 252

US

Gerard Gibson p. 256

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

4

Suspiria

Nicole Hamilton p. 261

Midsommar

Dawn Keetley p. 266

Pet Sematary

Rebecca Wynne-Walsh p. 272

EVENT REVIEWS

Folk Horror in the Twenty-First Century

Máiréad Casey p. 276

Theorizing Zombiism

Miranda Corcoran p. 287

HAuNTcon

Madelon Hoedt p. 296

INTERVIEW

With Aislinn Clarke

Máiréad Casey p. 300

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS p. 308

Editor: Dara Downey

ISSN 2009-0374

Published Dublin, 2020

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

5

EDITORIAL NOTE

Welcome to Issue #18 of The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies. This issue marks the

14

th

anniversary of the journal, which was established in October 2006 by Elizabeth McCarthy

and Bernice Murphy, with the support of what was then the M.Phil. in Popular Literature in the

School of English in Trinity College Dublin. The IJGHS has seen a number of changes since

then in terms of the editorial team, the online platform we use to bring you our open-access

content, and the frequency of publication.

The current issue marks one such change, albeit a temporary one. Due to a range of

personal circumstances, we did not publish an issue in 2019, and Issue #18 is therefore even

longer than usual, with six articles, covering a range of topics from eighteenth-century gothic to

contemporary theories of speculative realism, and over a hundred and fifty pages of reviews,

covering academic books, fiction, TV and podcasts, film, and events, capped off with an

interview with Northern-Irish filmmaker Aislinn Clarke.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank our many contributors for their hard work

and patience over the past eighteen months, which have been unusually unpredictable, both for

us personally and on a global scale. As a small, independent, self-funded journal, run mainly by

precariously employed scholars and those who have left academia, we are very much at the

mercy of forces larger than ourselves, a situation that any good gothic hero or heroine should

recognise all too easily. We have also, however, been incredibly lucky in terms of receiving

support (whether editorial, technical, and moral) from a wonderful and very generous network. I

am particularly grateful for the help of Niall Gillespie, Valeria Cavalli, Indira Priyadarshini

Gopalan Nair, and Jennifer Daly over the past few months, as well as the excellent work done

by our reviews editors, Sarah Cullen, Ruth Doherty, Elizabeth Parker, and Leanne Waters.

We will be releasing details of our new Call for Papers shortly, via our website

(https://irishgothicjournal.net/), and our social-media pages on Facebook, Twitter, and

Instagram. Please email us (irishjournalgothichorror@gmail.com) if you have any queries, and

we’re always happy to receive submissions of articles and reviews on a rolling basis

throughout the year. And in the meanwhile, we hope that you enjoy Issue #18, just in time for

Halloween.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

6

Statement re: Issue#12 (2013)

On 5 October 2020, the editors were made aware that the article ‘Ghosted Dramaturgy: Mapping

the Haunted Space in Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More’ from issue 12 (2013), by Dr. Deidre

O’Leary (Manhattan College), took liberally, and in an uncredited fashion, from Dr. Alice

Dailey’s published article ‘Last Night I Dreamt I Went to Sleep No More: Intertextuality and

Indeterminacy at Punchdrunk’s McKittrick Hotel’ (in Borrowers and Lenders: A Journal of

Shakespeare and Appropriation (Winter 2012)). Dr. O’Leary’s article has been retracted due to

plagiarism.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

7

‘Do you all want to die? We must throw them out!’: Class Warfare,

Capitalism, and Necropolitics in Seoul Station and Train to Busan

Jessica Ruth Austin

The undead, and the notion of life beyond death, have long been important components of gothic

literature, and, arguably, this is increasingly the case in modern popular culture. Carol Margaret

Davison has noted that ‘many gothic works meditated on death and death practices as a signpost

of civilisation’.

1

This essay explores the ways in which ‘undead practices’ function as a signpost

of social inequality in a society, with zombie narratives as a useful tool for theorising death and

death practices. In particular, the link between zombies and necropolitics (where it is decided

which people in society live and which will die) is made explicit in the South-Korean films Seoul

Station and Train to Busan.

2

As I argue here, in these films, zombies are culturally representative

for a South-Korean audience that is viewing them, and moreover, are connected to South-Korean

death practices. I argue that these films highlight important necropolitical practices in South-

Korean society today, with South-Korean audiences experiencing these zombie narratives

differently to models outlined in previously published work on Western consumption of zombie

narratives.

As Achille Mbembe has proposed, necropolitics could be described as ‘the ultimate

expression of sovereignty’ when it comes to ‘the power and the capacity to dictate who may live

and who must die’, a formulation that, as this essay argues, can usefully be applied to the zombie

horror genre, and specifically to Seoul Station and Train to Busan.

3

This essay covers the way

that these films represent necropolitical practices in South Korea in terms of work and labour,

and of political hierarchies that have emerged in South-Korean society because of this. This

essay utilises the concept of cinesexuality and work on zombies by Patricia MacCormack, who

argues that films can evoke specific, distinct responses from domestic audiences, due to the

presence of symbolism specific to the films’ cultures of origin, evoking a deeper pleasurable

1

Carol Margaret Davison, ‘Trafficking in Death and (Un)dead Bodies: Necro-Politics and Poetics in the Works of

Ann Radcliffe’, The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, 14 (2015), 37-48 (p. 39).

2

Seoul Station, dir. by Yeon Sang-ho (Studio Dadashow, 2016); and Train to Busan, dir. by Yeon Sang-ho (Next

Entertainment World, 2016).

3

Achille Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, trans. by L. Meintjes, Public Culture, 15.1 (2003), 11-40 (p. 11).

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

8

experience than for those watching without these cultural referents. I argue here that this

framework means that South-Korean domestic zombies symbolise a particular necropolitical

inequality when it comes to class and labour that is specific to South Koreans, in opposition to

Western offerings, which often symbolise over-consumerism.

The story of Seoul Station (a prequel to the events of Train to Busan) centres on a young

ex-prostitute and runaway named Hye-sun. She has run away from her former brothel but has

ended up with little money and a boyfriend who wishes to pimp her out again. Hye-sun

represents a class of women who started to arrive in Seoul from the 1970s onwards, called

‘mujakjŏng sanggyŏng sonyŏ’, which can be translated as ‘a girl who came to the capital without

any plans’.

4

In her attempts to escape from the zombies she encounters, she is often hindered by

authority figures such as police and soldiers, and the only help she receives is from the homeless

community. She dies at the end of the narrative, with few people mourning her loss, only

disappointed that they can no longer use her body for labour, making hers a necropolitical death.

Her story reflects specific South-Korean anxieties over their newly developed class structure.

Train to Busan similarly reflects on current South-Korean anxieties over class. The protagonist

Seok-woo is a workaholic who is taking his young daughter Su-an on the train from

Gwangmyeong Station to Busan. It soon becomes apparent that zombies are on the train and at

the stations where the train subsequently tries to stop. The film’s narrative shows how class and

necropolitics dictate decisions made by characters on the train as to who is ‘worthy’ of living and

who should die. This is epitomised in a scene where the rich, bourgeois, CEO character Yon-suk

moves healthy survivors out of ‘his’ train carriage. He convinces the other first-class passengers

to throw out the survivors from down the train, exclaiming ‘[d]o you all want to die? We must

throw them out!’ This scene is at the epicentre of South-Korean anxieties about class, and

frustrations around how rich elites have in the past disregarded human life for profit.

These films can be understood through the lens of Peter Dendle’s 2007 essay ‘The

Zombie as Barometer of Cultural Anxiety’, which argues that zombies should not be read as

simply a paranormal entity, as they are often used to highlight important contemporary social

issues. For example, Dendle asserts that the 1932 film White Zombie, directed by Victor

Halperin, locates the zombie as highlighting the ‘alienation of the worker from spiritual

4

Jin-Kyung Lee, Service Economies: Militarism, Sex Work, and Migrant Labor (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 2010), p. 86.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

9

connection with labour and from the ability to reap reward from the product of labour’.

5

Dendle

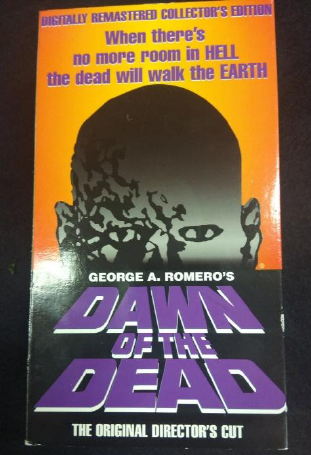

suggests that later zombie movies, such as those by George A. Romero, portray society as

nihilistic, and a ‘sign of an over-leisurely society, unchecked power and its desires for

consumption’.

6

Critical responses to the zombie film tend to focus on this later interpretation of

the zombie as a symbol of consumption, leaving a gap in literature for different interpretations of

the zombie, which this essay aims to fill, arguing that the zombie in South-Korean narratives has

a necropolitical focus as opposed to one relating to consumption; a consumption allegory is a

Western zombie narrative trait rather than one that can be applied to global cinema. South Korea

has had domestically successful zombie anthologies, and films such as The Neighbor Zombie,

Goeshi, and Doomsday Book differ from Dendle’s model by focusing on family and societal

hierarchies as opposed to consumption habits. The two films analysed here follow this tradition

in South-Korean cinema zombie narratives.

7

Train to Busan was the first South-Korean zombie movie to be hugely successful on the

international market, making $85 million, compared to films such as The Neighbor Zombie,

which barely made $17,000 on the international market.

8

It is therefore important, following

MacCormack’s model, to examine the cultural specifics of these films, as they are now reaching

a wider audience. Although early scholarly work on the zombie noted the contribution of stories

of voodoo zombies from Haiti and other diverse cultural narratives, recent scholarly analysis of

the zombie has tended to have an Anglo-centric basis.

9

For Train to Busan and Seoul Station in

particular, an eagerly awaited sequel, Peninsular, is expected in late 2020 and is expected to also

5

Peter Dendle, ‘The Zombie as Barometer of Cultural Anxiety’, in Monsters and the Monstrous: Myths and

Metaphors of Enduring Evil, ed. by Niall Scott (New York: Rodopi, 2007), pp. 45-57 (p. 46).

6

Dendle, ‘The Zombie as Barometer’, p. 54.

7

The Neighbor Zombie, dir. by Hong Young-guen and Jang Yun-jeong (Indiestory, 2010); Goeshi, dir. by Kang

Boem-gu, (Hanrim Films, 1981); and Doomsday Book, dir. by Kim Jee-woon and Yim Pil-sung (Zio Entertainment,

2012).

8

Box Office Mojo, ‘Train to Busan’, n. d.

<https://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=intl&id=traintobusan.htm> [accessed 1 October 2019]; and IMDB,

‘The Neighbor Zombie’ n. d. <https://pro.imdb.com/title/tt1603461?rf=cons_tt_atf&ref_=cons_tt_atf> [accessed 2

October 2019].

9

Dendle, ‘The Zombie as Barometer’, p. 46. See also Christian Moraru, ‘Zombie Pedagogy: Rigor Mortis and the

US Body Politic’, Studies in Popular Culture (2012), 34, 105-27 (pp. 106-07); Kyle William Bishop, ‘Vacationing

in Zombieland: The Classical Functions of the Modern Zombie Comedy’, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts

(2011), 22.1, 24-38; Justin Ponder, ‘Dawn of the Different: The Mulatto Zombie in Zack Synder’s Dawn of the

Dead’, Journal of Popular Culture (2012), 45.3, 551-71; Helen K. Ho, ‘The Model Minority in the Zombie

Apocalypse: Asian-American Manhood on AMC’s The Walking Dead’, Journal of Popular Culture (2016), 49.1,

57-76, (p. 59); and Tim Lazendorfer, Books of the Dead: Reading the Zombie in Contemporary Literature (USA:

University Press of Mississippi, 2018), p. 10.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

10

do well on the international market, making these films ripe for academic analysis distinct from

this Anglo-centric base. Although I focus on analysing these films through a different cultural

lens, previous work by Helen Ho on The Walking Dead does offer a starting point for an analysis

of the films examined in this essay. She states that

Zombie narratives […] offer a unique lens through which to investigate our current social

structures and relations: wholly nested within existing structural frameworks of

race/gender/class, viewers are given the opportunity to watch survivors on screen who

test, challenge, or dismantle those frameworks as they establish a new social order.

10

While Ho uses this lens to then investigate American social structures, this essay uses this idea to

look at social structures/relations from a South-Korean point of view. Although South-Korean

zombie movies have many commonalities with their American-produced counterparts (including

lots of gore and special effects), the social issues that are found within these films connect

specifically with the class divides and necropolitics that South Korea is currently facing. This

essay therefore utilises American-based readings of zombie films, which suggest that zombie

films hold allegorical symbolism for class relations and consumption habits to Americans, and

applies them with an awareness of the specificity of the South-Korean setting. South-Korean

spectators will experience their zombie movies through their own cultural lens, and, as I argue in

this essay, their zombie narratives rarely, if at all, symbolise over-consumption, but instead focus

on necropolitical issues that are present in South-Korean society.

As a means of moving beyond such American-focused readings, Patricia MacCormack’s

theory of ‘cinesexuality’ provides a useful theoretical framework through which to discuss these

films. She argues that horror films (especially zombie films) can break established societal

‘rules’ (such as heterosexuality and the nuclear family being preferred dominant modes of

society) due to the discomfort and effects of pain that a spectator experiences while watching

zombies tear apart everyone – not just those with a poor social standing. As MacCormack

asserts,

They are not wolves or women (because they are no longer striated and signified within a

human taxonomy) but they are human to the extent that they belong to the same form-

structure, albeit increasingly tentative depending on their state of dishevelment. If their

10

Ho, ‘The Model Minority’, p. 60.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

11

bodies are our bodies, and we desire them while they are impossible non-cinematically,

disgusting in their resemblance, then it is our bodies which must resemble theirs.

11

MacCormack argues that cinema is one of the most prolific modes of modern communication

and that ‘it is able to mask ideology behind claiming to be fictional’.

12

Consequently, for the

viewer, cinema is able to ‘affirm possible realities’.

13

MacCormack notes that in Western

filmmaking, for instance, the ways in which woman are taught ‘how to be an attractive desirable

woman’ in society is reflected in actresses chosen for mainstream films, helping solidify this

‘reality’.

14

This essay argues that the films analysed here integrate necropolitical ideology so as to

‘affirm’ a reality that South Koreans live every day, in that many of these narratives highlight

contemporary social inequality, and the use of zombies as a ‘death practice’ tries to expose this

inequality. I also argue that this is why zombie films from South Korea are different allegorically

to those in Western cinema, in that cinesexuality acknowledges that a spectator’s experiences

will affect their interpretation of the film:

If viewing self includes a modality of memory (including individual and social history)

assembled as an immanent remembered present with screen, then the particularities of

that memory, including its oppressions, subjugations and powers, are co-present with the

event. One’s self is mapped according to the importance placed on these memories and

the modal configurations they make with the present self.

15

In this sense, cinesexuality highlights how a spectator’s experiences of power dynamics and

cultural memories are mapped onto the film they are watching. A reading incorporating

MacCormack’s idea of cinesexuality thus stresses the extent to which South-Korean spectators to

have a culturally and socially important connection to the film, in much the same way that

Americans may experience their own culturally embedded anxieties when experiencing

American-produced zombie media texts. This assertion emerges from one of MacCormack’s

most important points in Cinesexuality – that spectatorship is ‘less about the object of analysis,

11

Patricia MacCormack, Cinesexuality (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 112.

12

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 3.

13

Ibid.

14

MacCormack, ‘A Cinema of Desire: Cinesexuality and Guattari’s Asignifying Cinema’, Women: A Cultural

Review (2005), 16.3, 340-55 (p. 342).

15

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 35.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

12

apprehension or perception and more about the means by which that object is experienced’.

16

More usefully for my purposes here, MacCormack goes on to explain that zombie-gore

cinesexuality in particular involves ‘desire for that which is immediately recognizable as us and

not us, so the way we can conceive body as form is opened up as a series of “asignified

planes”’.

17

What this suggests is that zombie bodies allow spectators to impose their own

interpretations onto these bodies and this can also offer the chance to examine how spectatorship

can become an act of activism or ethics.

Tim Huntley argues that a cinesexuality framework means that ‘the viewer must become

other’, and that this is imperative when it comes to the ethical viewing of cinema.

18

Huntley

contends that ‘cinesexuality promotes a case for difficult thought and painful thinking that shares

a relation both metaphorical and metonymical with difficult watching; painful viewing’.

19

Not

only does cinesexuality then work as a productive framework for analysing zombie narratives,

due to the actual physical repulsion experienced by viewers when watching zombies cannibalise

humans on screen, but also because zombie narratives often represent ‘painful’ social issues such

as inequalities of race, class, and gender.

20

As I argue here, this model of cinesexual

spectatorship is a useful tool for analysing the experience of South Koreans watching Seoul

Station and Train to Busan. Moreover, doing so helps draw attention to the ways in which these

films critique many of the necropolitical issues, such as labour, in South Korea today, a

characteristic that, I argue, was a contributing factor to their popularity.

Labour and Work

There has been a distinct and rapid shift when it comes to labour and work in South Korea, with

the service industry becoming a relatively new one compared to Western countries. This has led

to historical tension between different ‘necropolitical classes’ of people in South Korea, which

has become an important part of recent cinema narrative. In Seoul Station, necropolitics in South

Korea is most evident in the way that the homeless are treated throughout the storyline. In the

real-world Seoul Station, homelessness has been a fact of life since 1998, when the Square

16

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 14.

17

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 113.

18

Tim Huntley, ‘Abstraction is Ethical: The Ecstatic and Erotic in Patricia MacCormack’s Cinesexuality’, The Irish

Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 8 (2010), 17-29 (p. 17).

19

Huntley, ‘Abstraction is Ethical’, p. 18.

20

Moraru, ‘Zombie Pedagogy’, pp. 106-07.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

13

became infamous as a space ‘where enormous numbers of homeless people resided’.

21

The

South-Korean government made it illegal to sleep in public places to try and rectify this ‘issue’,

but these policies were unpopular and often viewed as attempts at social ‘cleansing’. In South

Korea, a common derogatory term to describe the homeless is ‘Purangin – who wander because

they cannot adjust to a work-place and family life’.

22

For those who use this term, the homeless

of Seoul Station are those who do not want to live up to societal standards. Critics argued that

these policies were ‘actually designed to protect “regular” citizens who might be offended or

harmed in some way by the presence of homeless people’.

23

The idea that the ‘homeless Other’

could ‘offend’ others just by existing is an example of how Mbembe describes the processes

through which government authorities decide who deserves to live and who dies; as he asserts,

‘the perception of the existence of the Other as an attempt on my life, as a mortal threat or

absolute danger whose biophysical elimination would strengthen my potential to life and

security’.

24

For Mbembe, in both early and late modernity, this imagined threat means that the

‘Other’ is created by those in power for reasons not based in fact.

25

In a powerful set of scenes in Seoul Station, the first infected person, and then fully

turned zombie, is a homeless man who resides at the Square. In the first fifteen minutes of the

film, we watch the old homeless man become sick and die, despite the best efforts of his

homeless friend to receive help from a pharmacist and the police, all of whom turn him away due

to seeing the homeless duo as pests and troublemakers. Here, then, the homeless Other is no

longer an imagined threat but a real one. Shaka McGlotten proposes that ‘zombies are […] a

radicalized underclass, a group of revolutionaries united by their shared oppression and arrayed

against the capitalist powers that be and those seduced by them’.

26

In cinesexual terms, then, the

use of a Purangin as the first zombie to appear can be interpreted as symbolic for the South-

Korean spectator. As MacCormack puts it,

21

Jesook Song, ‘The Seoul Train Station Square and Homeless Shelters: Thoughts on Geographical History

Regarding Welfare Citizenship’, in Sittings: Critical Approaches to Korean Geography, ed. by Timothy R.

Tangherlini and Sally Yea (Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), pp. 159-72 (p. 160).

22

Song, ‘The Seoul Train’, p. 166, italics in original.

23

Song, ‘The Seoul Train’, p. 163.

24

Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, p.18.

25

Ibid.

26

Shaka McGlotten, ‘Zombie Porn: Necropolitics, Sex, and Queer Socialities’, Porn Studies 1.4 (2014), 360-77 (p.

366).

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

14

The definitions of the meanings and desires of those bodies that watch may

simultaneously be multiplied and investment in any position as opposed to the fictive

disappears. It is no longer a question of which are fictive and which realistic, but which

are more resonant with established dominant fictions.

27

The dominant fiction from the South-Korean government – that the homeless of Seoul Station

constitute a necropolitical threat – is brought alive through both films, which, for South-Korean

spectators, may evoke the culturally specific social taboo of becoming a Purangin themselves.

This is also why it is so powerful that the Purangin are also among the few characters to try and

help Hye-sun survive in Seoul Station.

Stephen Shaviro notes that violations of social taboo in horror are significant ‘not so

much on account of what they represent or depict on the screen as of how they go about doing

it’.

28

This is important when we consider historical representations of the zombie in Eastern

cinema, as South-Korean zombie films tend to share more similarities with Western zombie

movies than other Eastern cinematic offerings. In Japan for instance, Rudy Barrett has noted,

many popular films use the zombie as a form of comedy-relief, because the monster is seen as a

Western phenomenon, since the overwhelming majority of Japanese people are cremated rather

than buried.

29

Therefore, ‘the iconic imagery of zombies rising from the grave is not only

culturally disconnected from the mainstream, it’s also completely impossible to depict

realistically in Japan’.

30

Moreover, Chinese cinema has had little influence on South-Korean

zombie films, because, until very recently, the Communist Party censored depictions of zombies

(and other supernatural monsters) for ‘promoting cults or superstition’, and only recently allowed

international zombie offerings to be shown in their cinemas.

31

As well as this, the zombies

(jiāngshī) that are referred to in Chinese folklore would be considered more akin to vampires in

their appearance, due to having long claws and a hatred of sunlight. Although there are steadily

increasing numbers of zombie films from Hong Kong, mainland China still heavily censors any

domestic filmmakers, which has put a constraint on any domestic offerings.

27

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 115.

28

Stephen Shaviro, The Cinematic Body (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), p. 114.

29

Ruby Barrett. ‘Why Japan Laughs At Zombies: Bbbbbraaaainnnnzz Braaaainzzz!! HEY! Why Aren’t You

Running?!’, Tofugu, 24 June 2014 <https://www.tofugu.com/japan/japanese-zombies/> [accessed 1 January 2019].

30

Ibid.

31

Charles Clover and Sherry Fei Ju, ‘China Unleashes Zombie Films to Boost the Box Office’, The Financial

Times, 16 June 2017 <https://www.ft.com/content/3878eed6-3ebc-11e7-9d56-25f963e998b2> [accessed 1 January

2019].

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

15

This may be why Train to Busan and Seoul Station display a focus on necropolitical

labour of the kind that is found in Western zombie narratives like Land of the Dead, Dead

Rising: Watchtower, and The Dead Don’t Die.

32

However, Seoul Station and Train to Busan

differ from these US offerings in their representation, as they focus on labour issues specific to

South-Korean history. In her work on South-Korean service economies, Jin-Kyung Lee defines

necropolitical labour as ‘[e]xtraction of labor from those “condemned” to death, whereby the

“fostering” of life, already premised on an individual’s death or disposability of her or his life, is

limited to serving the labor needs of the state or empire and capital’.

33

In South Korea, the

migration of the rural proletariat into major cities in the latter half of the twentieth century

increased this necropolitical labour (as mentioned above), creating an urban middle class, which

had not previously existed in great numbers. In South Korea, the creation of a particularly

wealthy middle class is therefore a far more recent occurrence than in Western countries; indeed,

Myungji Yang argues that this class was created artificially, stating that ‘the formation of an

urban middle class was a political-ideological project of the authoritarian state to reconstruct the

nation and strengthen the regime’s political legitimacy’.

34

Therefore, surplus female labour in

particular led to a new ‘“social-sexual” category of working-class women, that is, as prostitutes

on the margins of rapidly industrializing South-Korean society’.

35

Not only did this create a new

labour category for women but, as Lee also noted, this newly formed middle class experienced

‘greater inter- and intragenerational mobility’ than ever before.

36

However, Shin Arita has found evidence to suggest that this has since stagnated; ‘in

Korea a person’s social consciousness is determined to a large degree by his native region and

this cuts across social classes’.

37

This may be because South Korea has a different class structure

than Western countries, due to South-Korean society’s emphasis on collectivism over

32

Land of the Dead, dir. by George A. Romero (Universal Pictures, 2005); Dead Rising: Watchtower, dir. by Zach

Lipovsky (Crackle, 2015); and The Dead Don’t Die, dir. by Jim Jarmusch (Focus Features, 2019).

33

Lee, Service Economies, p. 82.

34

Myungji Yang, ‘The Making of the Urban Middle Class in South Korea (1961-1979): Nation-Building,

Discipline, and the Birth of the Ideal National Subjects’, Sociological Enquiry, 82.3 (2012), 424-45 (p. 424).

35

Lee, Service Economies, p. 86.

36

Ibid.

37

Shin Arita, ‘The Growth of the Korean Middle Class and its Social Consciousness’, The Developing Economies, 2

(2003), 201-20 (p. 207).

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

16

individualism.

38

Neil Englehart has argued that this a defining characteristic of Asian cultures,

‘characterized by a set of values that includes obedience to authority, intense allegiance to

groups, and a submergence of individual identity in collective identity’.

39

And this is still

culturally significant today; for example, a comparative study found that homeless teens in the

United States display individualistic behaviours, while South-Korean teens display collective

group behaviours.

40

There is even a growing sentiment that the more recent South-Korean move

away from collectivism is not even individualistic, but rather a move towards egotism, in that,

instead of promoting self-reliance and independence, moral behaviour becomes self-interest.

However, this move towards egotism is not seen as a moral behaviour for most South Koreans,

and these frustrations appear in Train to Busan and Seoul Station; the narrative portrays wealthy

characters as egotists who only look out for themselves, and this characterisation is seen in other

recent popular South-Korean movies such as Flu and Deranged.

41

Lead character Seok-woo is presented in Train to Busan as a middle-class workaholic

who is uncaring when it comes to business decisions that have repercussions for others. In

conversation with his secretary Kim, he is depicted as callous and comparable in attitude to

wealthy CEO Yon-suk who is, as discussed below, depicted in an unambiguously negative light:

Kim: What should we do?

Seok-woo: Sell all related funds.

Kim: Everything?

Seok-woo: Yeah.

Kim: They’ll be serious repercussions. Market stability and individual traders will …

Seok-woo: Kim?

Kim: Sir?

Seok-woo: Do you work for the lemmings?

Kim: [character pauses]

Seok-woo: Sell everything right away.

42

38

Sanna, J. Thompson, Kim Jihye, Holly McManus, Patrick Flynn, and Hyangcho Kim, ‘Peer Relationships: A

Comparison of Homeless Youth in the USA and South Korea’, International Social Work, 50.6 (2007), 783-95 (p.

785).

39

Neil A. Englehart, ‘Rights and Culture in the Asian Values Argument: The Rise and Fall of Confucian Ethics in

Singapore’, Human Rights Quarterly, 22.2 (2000), 548-68 (p. 550).

40

Thompson and others, ‘Peer Relationships’, p. 783.

41

Park Sang-seek, ‘Transformation of Korean Culture from Collectivism to Egotism’, Korea Herald, 5 November

2018 <http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20181104000265> [accessed 13 September 2019]; Flu, dir. by

Kim Sung-su (CJ Entertainment, 2013); and Deranged, dir. by Park Jung-woo (CJ E&M, 2012).

42

Train to Busan, 00:04:58-00:05:21.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

17

For many South-Korean viewers, while his characterisation becomes more sympathetic as the

film’s narrative develops, it is likely that Seok-woo would not be seen as an inherently relatable

or likeable character to begin with, as he is represented as a ruthless individualist, sacrificing

traders (the collective) for personal gain. Some scholars are critical of using social class

‘warfare’ as a narrative strategy, asserting that the zombie narrative can actually reinforce these

supposed norms, rather than challenging these power differentials. But this initial portrayal of

Seok-woo is intrinsically important to the South-Korean viewer, in that he represents the new

Korean class system, which is criticised as egotistical; however, he ends up redeeming himself

later by working back for the ‘collective’ good. This may give a South-Korean viewer a moment

of subversive cinesexual pleasure, due to him resisting a total move into egotism. The overall

shift towards individualism by the new middle class is not always seen negatively, but when it

moves into the realm of egotism, South-Korean audiences and film narratives prefer to revert

back to more traditional collective norms. This is important, in that South-Korean audiences gain

a cinesexual pleasure by watching this egotism punished or ‘corrected’, whereas it is monetarily

rewarded in real life, something that is at odds with their values. This also suggests that South-

Korean cinema does not end up reinforcing norms.

For Lina Rahm and Jörgen Skăgeby, the idea of ‘prepping’ for the zombie apocalypse

and the idealisation of ‘how the strongest survive’ has reinforced certain negative ideals; they

state that ‘the zombie metaphor corresponds well to the normative model of the “best prepared

body”, and reinforces the development of skills and mindsets that are fundamentally sexist,

ageist, and ableist’.

43

However, in cinesexual terms, zombies do not always reinforce stereotypes

but are capable of dismantling them too; for MacCormack, ‘the term “zombie” guarantees that

any dismantling cannot lead to death and must lead to something else post-death. Viewing

zombies does not lead to fear of death but its own “something else.”’

44

Using a cinesexual

argument, the zombie in these films can be read, not as signifying literal death but as allegorical

for the death of collectivism. This is because many of the zombie-related deaths are caused by a

character making an individualistic (or egotistical) choice rather than one that is good for the

collective.

43

Lina Rahm and Jörgen Skăgeby, ‘Preparing for Monsters: Governance by Popular Culture’, Irish Journal of

Gothic and Horror Studies, 15 (2015), 76-94 (p. 83).

44

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 99.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

18

Furthermore, when thinking in terms of capitalism (which is associated with the rise of

individualism), spectators end up realising that Seok-woo embodies the category of cultural

zombie – that is, ‘characters who have lost self-identity or the capacity for volition’ – without

being a literal member of the undead.

45

This is because the focus given to corporate culture

rather than the health or wellbeing of the collective is an important issue that South Korea is

facing; zombies function to scrutinise allegorically this state of affairs throughout the two films.

Shaviro argues that the zombie is ‘a nearly perfect allegory for the inner logic of capitalism’.

46

Seoul Station and Train to Busan represent this ‘logic’ as developing at the expense of the

collective, producing a South-Korean zombie narrative that is distinct from Western zombie

texts, which focus on consumption.

To elaborate, Mbembe has argued that necropolitics and

necropower account for ‘new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are

subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead’.

47

Seok-woo

therefore becomes, for the South-Korean spectator aware of such issues, an imaginative

representation of necropolitical labour. The characterisation and eventual demise of Hye-sun in

Seoul Station also performs this function.

Jin-Kyung Lee proposes that prostitution can also be considered as necropolitical labour,

in that it is ‘sexual violence via commercialisation’.

48

In Seoul Station, in death, Hye-sun is still

only considered as valuable via the necropolitical labour that she brought her pimp (Suk-gyu) in

life. When Hye-sun dies, Suk-gyu initially seems sad at the prospect of her death, but quickly his

thoughts turn to the money he has now lost:

Suk-gyu: Wake up! Hey! Hye-sun? Dammit, don’t die, baby! Hye-sun, please don’t, I’m

sorry! Hye-sun! It’s all my fault! Please don’t die! Pay me back first, you bitch!

49

Her death is necropolitical; for Lee, ‘work itself’ can be seen ‘as necessarily incurring injury and

harm to the body and mind – work as trauma, violence, and mutilation that indeed lies in

continuum with death’.

50

Hye-sun’s entire worth has been tied into the labour that her body can

45

Sang-seek, ‘Transformation of Korean Culture ‘, n. p.; and Kevin Alexander Boon, ‘Ontological Anxiety Made

Flesh: The Zombie in Literature, Film and Culture’, in Monsters and the Monstrous, pp. 33-43 (p. 40).

46

Shaviro, The Cinematic Body, p. 98.

47

Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, p. 40.

48

Lee, Service Economies, pp. 80-82.

49

Seoul Station, 01:28:20-01:28:47.

50

Lee, Service Economies, p. 83.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

19

produce. However, viewers may feel some cinesexual pleasure when it is revealed that Hye-sun

has become a zombie and proceeds to eat Suk-gyu before the movie promptly ends. McGlotten

argues that zombie narratives help to expose the viewer to the ideology of necropolitics and

labour, in that they are representative of a body that has been used up in the ‘service of profit’.

51

By having Hye-sun turn into a zombie, who then eats the person who was exploiting her labour,

the film makes a powerful comment to South Koreans who may feel discomfort surrounding the

society’s current attitude to work and labour. In addition, McGlotten claims that such films

‘allegorize the logical end to capitalist society’ and perhaps, for South-Korean audiences, a

possible return to a collective mentality, often at the expense of comforts that the political elite

have thus far enjoyed.

52

Necropolitics and the Political Elite

This criticism of economic individualism appears as a common trope that has appeared in many

South-Korean horror or disaster movies; it often comes in the guise of high-level military

commanders making decisions that benefit them necropolitically (saving the rich and powerful

who keep them in their high-powered positions) or a minority of CEOs who make individualist

decisions for profit. In films such as Flu and Deranged, ordinary citizens who are portrayed as

sympathetic protagonists are often oppressed by military forces trying to quarantine ‘infected’

citizens. In Seoul Station, towards the end of the film, the army have quarantined the protagonist

Hye-Sun and others in an infected neighbourhood; Suk-gyu (her pimp) tries to get through to her,

but is pushed back by the soldiers, who proclaim that the citizens’ protesting is simply

‘annoying’. The location of the film and the response of the military can be evocative for a

South-Korean spectator, in that, until the early 1990s, Seoul Station ‘was the site of mass

demonstrations urging political action against authoritarian regimes’.

53

This ties in with

MacCormack’s cinesexual assertion that spectators view films with ‘established dominant

fictions’ and nostalgic memory in their minds.

54

For South-Korean viewers, then, a necropolitical

and cinesexual experience may occur because they may have living memory of times where the

government took an authoritarian view on who would live and who would die. In Flu, both

51

McGlotten, ‘Zombie Porn’, p. 365.

52

Ibid.

53

Song, ‘The Seoul Train’, p. 160.

54

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 115.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

20

infected and uninfected people are quarantined in the same place by the army and South-Korean

government. Even though uninfected individuals were told that they would only be held for

forty-eight hours if they remained in good health, officials decide to hold them within the

quarantine to keep the rest of the country safe, especially the nearby capital of Seoul. This has

necropolitical implications, depicting authoritarian forces that enact a preference for keeping the

wealthy who live in the capital ‘safe’, by letting those who live in the less affluent suburbs and

rural areas die. In Seoul Station, this fear of the army and government using martial law to create

a quarantine is dramatised later when the commander of the police force becomes scared, while

notifying Hye-sun’s boyfriend that the government was now entirely in control of trying to

‘contain’ the zombie outbreak. The following exchange takes place:

Ki-woong: What’s up with those soldiers? What’ll happen now?

Commander: Capital Defence Command [panicked pause] is now in full control.

55

This fear of governmental control when it comes to disasters, which often require co-ordination

from different authorities, may also provide a cinesexual experience when it comes to recent

memory for South Koreans, such as the critical response to the government handling of the

Sewol Ferry disaster in 2014; the ferry crashed en route from Incheon to Jeju, killing 273 people,

many of them high-school students. The South-Korean government was criticised for their

botched co-ordinating of the coastguards’ rescue attempt, and for also downplaying their own

culpability when it came to the poorly enforced shipping regulations, which were a secondary

cause in the ship’s mechanical difficulties. Using MacCormack’s model, disasters such as this

allow us to view a lack of confidence in the political elite as a dominant narrative in South

Korea, which may constitute a subtext to the containment narratives in Seoul Station and Train to

Busan. Using MacCormack’s theory then, we can suggest that South-Korean audiences

experience a cinesexual pleasure when government officials are overrun in movies later in the

narrative.

In Train to Busan, the necropolitics concerning South-Korean class warfare are

represented via the character of Yon-suk, a wealthy CEO. Since the revival of Korean cinema in

the 1990s, an overarching theme has been that of taking revenge against egotistic capitalistic

characters. Andrew Lowry attributes this directly to the social upheaval of the time, as ‘social

55

Seoul Station, 01:07:39-01:07:47.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

21

anger was and is directed at business leaders, most of whom stayed quiet and got wealthy while

the earlier regime was shooting students in the streets’.

56

South-Korean horror films that critique

wealthy, capitalist characters, who are often depicted as saving themselves at the expense of

poorer characters, include Flu, OldBoy, I Saw the Devil, Snowpiercer, Parasite, and of course

Seoul Station and Train to Busan.

57

A similar critical depiction of the capitalist class is also seen

in Deranged, in which mutated horse-hair worms infect human beings through the water supply.

The infected, being controlled by the worms, begin to consume copious amounts of water or

throw themselves into nearby rivers so that the worms can proliferate and infect more humans.

By the end of the film, the spectator finds out that, in fact, a group of wealthy CEOs created

these worms, knowing that they had the cure stored in warehouses, which they could then sell at

top prices to the infected, while also increasing their company’s stock prices – and that they had,

of course, saved a remedy especially for themselves first.

This compliments the necropolitics seen in Train to Busan, as we see Yon-suk use his

wealth and position to kill off ‘less deserving’ passengers. When the train stops at Daejeon

Station, which turns out to be overrun by zombies, Yon-suk tries to save himself from the

zombie hoard by insisting that the train conductor leave other passengers behind. Later in the

film, the protagonist Seok-woo, his daughter Su-an, and a number of other passengers use

various measures to combat or avoid zombies as they move through the train cars to get to the

first-class cabin car where other survivors, including Yon-suk, are hiding. When Seok-woo

confronts and accuses Yon-suk of not saving other passengers, and actively using others as a

human shield, Yon-suk convinces the other passengers that Seok-woo is a threat:

Seok-woo: Why did you do it? You bastard! You could have saved them! Why?

Yon-suk: He’s infected! He’s one of them! This guy’s infected! His eyes! Look at his

eyes! He’ll become one of them! Do you all want to die? We must throw them out!

Train attendant: Those of you who just arrived, I don’t think you can stay with us, please

move to the vestibule.

58

56

Andrew Lowry, ‘Slash and Earn: The Blood-Soaked Rise of South-Korean Cinema’, The Guardian, 31 March

2011 <https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2011/mar/31/south-korean-cinema-blood-saw-devil> [accessed 1

October 2019].

57

Oldboy, dir. by Park Chan-wook (Show East, 2003); I Saw the Devil, dir. by Park Hoon-jung (Softbank Ventures

Korea, 2011); Snowpiercer, dir. by Joon-ho Bong (Moho Film, 2013); and Parasite, dir. by Joon-ho Bong (CJ

Entertainment, 2019).

58

Train to Busan, 01:15:50-01:16:39.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

22

Although it can be suggested that Yon-suk is lying about the survivors being infected because he

just wants them out of the first-class carriage, and that this scene therefore acts as a

characterisation tool, it also highlights the necropolitics surrounding these survivors to the South-

Korean spectators. The purpose of the exchange between Seok-woo and Yon-suk makes the

‘othering’ of the survivors apparent. The willingness of the first-class passengers to believe that

the survivors are turning into zombies when they are clearly not infected connects closely with

Mbembe’s theorisation of making the ‘Other’ into a threat that can legitimately be

extinguished.

59

MacCormack notes that othering of bodies occurs when they are split into

majoritarian or minoritarian (part of the elite or part of the minority); she states that ‘minoritarian

bodies are signified via their failures to be majoritarian – not female but not-male, not queer but

not-heterosexual and so forth’.

60

In this way, the survivors are already zombie Others, even

though they are not infected with the zombie virus. Yon-suk’s willingness to immediately enact

necropolitics by judging which passengers are minoritarian compared to his perceived

majoritarian self is reminiscent of historical events in South Korea such the April Revolution,

where President Syngman Rhee used violence to suppress opposing views.

61

Yon-suk uses

misinformation and then violence to try to ensure that he survives, which was a common way

previous South-Korean governments operated to keep the masses from overthrowing an

authoritarian rule. In cinesexual terms, the positioning of ‘the spectator as a desiring subject and

the relation between the image and spectator as a decision toward openness and grace or

reification of subject’ means that viewers are directed towards an ethical viewpoint regarding the

Yon-suk character, a viewpoint which may be less evident to viewers from a different socio-

cultural context.

62

However, it is becoming a minoritarian Other that in the end saves the survivors. Upset at

the death of her sister and disgusted by the banishment of the survivors, Jong-gil opens up the

doors and allows the zombie horde inside the first-class cabin. This is a pivotal scene, due to the

reversal of the zombies’ role – from monsters to heroes – as they are used to dispose of the ‘real

59

Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, p. 18.

60

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 65.

61

Lee Moon-young, ‘When the April 19 Police Officers Asked the Marshall Commander to Borrow 100,000

Bullets’, Hani, 18 April 2011 <http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/473473.html> [accessed 30

January 2019].

62

MacCormack, ‘An Ethics of Spectatorship: Love, Death and Cinema’, in Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of

Cinema, ed. by Ian Buchanan and Patricia MacCormack (London and New York: Continuum, 2008), pp. 130-42 (p.

132).

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

23

monsters’. For MacCormack, the tendency to view zombies merely as monsters can become

theoretically problematic. She writes,

When publicly disseminated and consumed, the separation of the zombie as Other

engenders both discursive and material power differentials. The theoretical nuances and

potentially disruptive capacities of zombies-as-monsters are thus lost due to a

fundamental rupture and subsequent hostility between humanity and what is now

something else. This separation, we argue here, is maintained by the arbitrary, but

specific, ‘rules of zombies’.

63

Therefore, it is vital to explore zombie narratives via a cinesexuality lens, as doing so highlights

zombie narratives’ potential for creating an ethical experience for the spectator via the figure of

the zombie. Shaviro notes this in relation to Romero’s zombie movies, arguing that zombies

‘serve to awaken a passion for otherness and for vertiginous disidentification that is already

latent within our own selves’.

64

The zombies in Seoul Station and Train to Busan are only

identifiable (and we are only on ‘their side’) when they begin disposing of the elite. Spectators of

the movie can therefore experience how becoming the minoritarian ‘Other’, and thus rejecting

the class structure present in South Korea, can save them from being cannibalised (by zombies or

ideologically). Jong-gil’s opening up of the first-class cabin (representing capitalist and corrupt

government) to allow the zombies to eat, and thus transform the first-class passengers into the

‘Other’, may therefore produce powerful cinesexual experiences for South-Korean spectators.

Within this framework, for spectators of Train to Busan, Yon-suk’s death later in the film

offers overt cinesexual pleasure. Yon-suk is characterised in the narrative as a totem for, or

crystallisation of, the revelations of corruption that emerged in South Korea in the years

preceding the release of the two movies. Specifically, the film’s positioning of Yon-suk as using

immoral means to stay alive has parallels with the immoral actions of South-Korean government

officials and CEOs in real life. For instance, President Lee Myung-bak (2008-13) was associated

with the company BBK, which had been implicated in stock-price manipulation in 2007, but he

was not arrested until 2018; President Park Geun-hye (2013-17) was impeached six months

before the two films release due to corruption.

65

In cinesexual terms, major corruption so close to

63

Rahm and Skăgeby, ‘Preparing for Monsters’, p. 82.

64

Shaviro, The Cinematic Body, p. 113.

65

Justin Fendos, ‘South Korea Goes from One Presidential Scandal to Another’, The Diplomat, 3 November 2017

<https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/south-korea-goes-from-one-presidential-scandal-to-another/> [accessed 30 May

2019].

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

24

the release of these two films could be understood to have affected the viewing process for South

Koreans. This is similar to the way in which Shaviro describes how, when watching zombie

movies, he ‘enjoy[s] the reactive gratifications of resentment and revenge, the unavowable

delights of exterminating the powerful Others who have abused [him]’.

66

For those watching

Yon-suk throughout the movie, the tension created by his actions leads to the cinesexual release

of watching him pay the consequences (with his death).

A powerful exchange in Seoul Station concerning necropolitical labour occurs between a

man wearing a ‘Be the Reds’ T-shirt and a homeless man. ‘Be the Reds’ was a phrase used on

merchandise for the 2002 FIFA World Cup Korean Republic football team, when the team

reached the semi-finals. This image acts as an important signifier even before any words are

exchanged, due to the social connotations of ‘Be the Reds’ to South Koreans. Although it was a

popular phrase in 2002, controversy befell the slogan when it was trademarked later in 2003. The

original artist retaliated by trade-marking the font instead, and thus no official ‘Be the Reds’

shirts were made after this, essentially meaning that capitalist individualism ruined the message

of collectivism behind the shirt.

67

The ‘Be the Reds’ shirt exemplifies to the spectator the social

strata within South Korea, the exact opposite of what the shirt and slogan was trying to achieve

in the World Cup – a unification. For MacCormack, ‘the question is not how real an image is in

encouraging us to address difference, but to what extent it makes us different subjects within a

shifted ecology as an environment not of subjects populating a space but a system of differential

relations’.

68

Therefore, the image of the rich character wearing a shirt that is supposed to

represent collectivism acting in his own self-interest can have a cinesexual effect on the

spectator; South Koreans are told that they should all be industrious for the good of South Korea,

but instead find themselves in a corporate workplace culture that horror films like Train to Busan

and Deranged criticise.

The ‘Be the Reds’ shirt also serves as a sign of the concomitant visual othering of the

homeless man, which many South Koreans will experience in a culturally charged way due to the

treatment of the homeless at Seoul Station referred to above. Yang argues that, in the 1960s,

when the middle class was being created by government incentives, the government employed

66

Shaviro, The Cinematic Body, p. 116.

67

Anon., ‘Red Devils to Sport New Official T-Shirt and Slogan’, Chosun Entertainment, 2 January 2006

<http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/01/02/2006010261003.html> [accessed 15 June 2020].

68

MacCormack, ‘An Ethics of Spectatorship’, p. 142.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

25

ideology to do so, stating that ‘the state could manage its population with less coercion and

violence by imposing the social discipline throughout society and creating more obedient and

industrious subject’.

69

‘Industrious’ is the operative word here, and serves to highlight why the

‘Be the Reds’ scene is so important. ‘Be the Reds’ is associated implicitly with a form of

national identity that is set in opposition to the so-called ‘Purangin’, figured by contrast as lazy,

spendthrift, and thus less deserving of life, in the necropolitical system. This is evident when it

comes to the verbal exchange between ‘Be the Reds’ and the homeless man:

Be the Reds: You bastards! I worked for my country! I’m different from you trash! You

are all useless! I don’t know how I got myself mixed up with you all! It looks like the

commies are behind this! But me? I don’t deserve to die here! I dedicated my life to this

country! I’m a good person. I’m a good person.

Homeless man: Out of my way. Dammit! I’m the same too! I made sacrifices for this

country! So how did I end up this way? Know why? Because this country doesn’t care

about us! But we worked ourselves to death, you fools! But the thing is, I must survive! I

want to live!

70

This kind of social anxiety is currently present in South Korea; there is a pervasive feeling that

being economically productive means that one is a ‘good’ member of South-Korean society. This

may be why this necropolitical narrative is far more pronounced in South-Korean horror movies

than in Western media texts, and why cinesexuality becomes important as a tool for analysis: a

cinesexuality lens allows us to interpret why narratives are culturally relevant to those who view

them rather than assuming, in this case, that all zombie narratives are about over-consumption. In

South Korea, as Arita’s study suggests, the urban middle class and ‘Be the Reds’ class system is

‘largely closed to intragenerational inflow mobility’, to the extent that ‘garnering [a white-collar]

job is greatly dependent upon a person’s level of education’.

71

Train to Busan and Seoul

Station’s use of zombies, and the interactions between those who are fleeing them, present to the

spectator the necropolitical labour of the extra-cinematic South Korea. Therefore, a South-

Korean audience may find cinesexual catharsis in seeing a character proclaiming that economic

productivity should not be the main aim of social collectivism in South Korea, especially given

the educational and social obstacles that prevent many from achieving this ideal.

72

This is a

69

Yang, p. 492.

70

Seoul Station, 01:07:56-01:09:23.

71

Arita, p. 218.

72

Ibid.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

26

theme evident in other South-Korean movies such as Deranged, in which the main character Jae-

hyuk is positioned to be viewed sympathetically by the spectator, because he lost his life savings

and job at a university due to a bad investment on the stock market, following which he is

shamed into taking a job as a pharmaceutical sales representative.

73

He has access to one of the

last boxes of the cure for the parasite and instead of saving it for himself, he tries to give away

some of the medicine to an ill mother and child. The implication here is that Jae-Hyuk is on the

side of collectivism rather than capitalist individuality, and thus is a character who may resonate

cinesexually with South-Korean viewers. For much the same reason, we are encouraged to grow

to like Seok-woo later in Train to Busan because he tries to save/look after not only himself but

his daughter, a Purangin, a pregnant woman, her husband, and two young teenagers. Instead of

passively watching the film, spectators may therefore engage in an ethical reading, via

cinesexuality.

Conclusion: Ethical Viewing Practices as Resistance

A cinesexual framework allows us to investigate how spectators may make ethical judgments

when watching Seoul Station and Train to Busan; in cinesexual terms, it is important to evaluate

the cultural importance of narrative choices and their effects on spectatorship. This essay has

argued that the representation of homelessness and labour versus the political elite has a specific

significance to South Koreans and may influence how they view the film. Within a cinesexuality

framework of the kind outlined here, spectators of Seoul Station and Train to Busan can see the

infected zombies as politically allegorical; death by zombie doesn’t mean a physical death but is

a representation to the viewer of how groups such as the Purangin, and those in the harsh

corporate culture permeating South-Korean workplaces, are being sacrificed already through

necropolitics. As MacCormack notes,

When we desire cinesexually we must think what extra-cinesexual social relations and

intensities the break away from dialectic communication will affect. As the fold of image

and spectator demands a rethinking of human subjectivity so too does this third trajectory

affect social relations.

74

73

Paul G. Bens, ‘Movie Review: Deranged (2012)’, Nameless Digest, 19 February 2017

<https://www.namelessdigest.com/movie-review-deranged-2012/> [accessed 1 October 2019].

74

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 143.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

27

Scholars focusing on Western media texts note that zombies tend to function ‘as metaphors for

American anxieties over potential catastrophes, ranging from viral pandemics to global warming

to alienation to consumer society’, as well as demonstrating the ‘limitations of social structures

and patriarchy’.

75

In Western zombie movies, seeing a rich person get eaten by zombies and the

plucky working-class under-dog survive is a common theme; scenes such as this appear in TV

shows such as Dead Set, Z-Nation, and in the film Land of the Dead.

76

For Henry Giroux and

Dendle, these representations are familiar and sometimes even cathartic due to a well-established

social-class system, which some see as unfair.

77

In a similar way, but with important cultural

differences, as has been argued here, Seoul Station and Train to Busan are effective in cinesexual

terms for South-Korean viewers because they encourage the spectators to form ethical

judgements on the characters through their own cultural lens.

The zombie-as-metaphor is becoming increasingly utilised to describe necropolitical

spheres. Giroux proposes that ‘zombie politics’ is an apt descriptor to describe the way that

politicians in the United States often make decisions that increase human suffering, making some

people more likely to live or die.

78

MacCormack’s cinesexuality theory prompts the spectator to

make a ‘decision toward openness and grace or reification of subject and object through

perception via pre-formed signification’.

79

Thus ‘zombie politics’ can be situated as central to the

experience of watching Seoul Station and Train to Busan, which is subject to a specific

negotiation of the South-Korean environment, subjectivity, and social relations. In the process,

the figure of the zombie in these films serves to create an ethical viewership, in MacCormack’s

terms.

Death images are important in that, as mentioned previously by MacCormack, zombies

do not depict a literal death but a change, in thinking and in action. As I have argued here, Seoul

Station and Train to Busan use zombies as an important narrative tool to dramatise social forces

in South Korea. For Shaviro, zombie narratives in general enable spectators to understand and

sometimes resist those that are acting upon them:

75

Ho, ‘The Model Minority’, p. 59.

76

Deadset, dir. by Yann Demange (Zeppotron, 27-31 October 2008); Z-Nation, pro. by Karl Schaefer (The Asylum,

2014-18); and Romero (2008).

77

Dendle, ‘The Zombie as Barometer’, p. 47

78

Henry A. Giroux, ‘Zombie Politics and Other Late Modern Monstrosities in the Age of Disposability’, Policy

Futures in Education, 8.1 (2010), 1-7 (p. 1).

79

Ibid.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

28

The zombies do not […] stand for a threat to social order from without. Rather, they

resonate with, and refigure, the very processes that produce and enforce social order. That

is to say, they do not mirror or represent social forces; they are directly animated and

possessed, even in their allegorical distance from beyond the grave, by such forces.

80

Kevin Boon argues that ‘the zombie […] is the most fully realized articulation of this dynamic

interdependency between the human self and the monstrous other’.

81

However, it has been

argued in this article that the zombies in Seoul Station and Train to Busan do not occupy a binary

between human and the Other for the spectator. A more accurate way to describe these zombies

comes from Dendle, who asserts that ‘the essence of the “zombie” at the most abstract level is

supplanted, stolen, or effaced consciousness; it casts allegorically the appropriation of one

person’s will by that of another’.

82

I have argued that cinesexual enjoyment of zombies allowed

South Koreans to ‘become’ the Other, to experience the necropolitics being enacted in their

culture. Moreover, Lazendorfer has noted that Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari use zombies to

‘signify the particular relation between death and capital that modern life has produced: they are

“a work myth”’.

83

The relation between class warfare and labour discussed here is evident not

only in Seoul Station and Train to Busan but is a common narrative in other films such as Flu

and Deranged, all of which use zombies to make that relation explicit.

Seoul Station and Train to Busan can therefore be read as critiques of South-Korean

culture, and investigating the cinesexual experiences of spectators renders this critique even

more explicit, as does situating it within necropolitics and politically motivated ethical

arguments as to ‘who should live and who should die’. A possible explanation for the popularity

of zombie narratives may be found in the frequency with which those who are typically ‘saved’

by necropolitics in the real world (the wealthy, the oppressors) rarely share this opportunistic fate

in the zombie movie. In Seoul Station and Train to Busan (and the other South-Korean movies

referenced here), the rich are just as likely to become a zombie as anyone else. For cinesexual

spectators, this is just one of the many pleasures available while watching these films.

Zombies in Seoul Station and Train to Busan create a repulsion-versus-desire effect; the

zombies represent the aspirations of current South-Korean culture (to be mindlessly

80

Shaviro, The Cinematic Body, p. 100.

81

Boon, ‘Ontological Anxiety’, p. 34.

82

Dendle, ‘The Zombie as Barometer’, p. 47.

83

Lazendorfer, Books of the Dead, p. 1.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

29

economically active and individualistic), but also image the negative social forces that result

from these aspirations; they represent social issues, but also a desire to change. For Huntley,

horror is one of the areas in which cinesexuality challenges spectatorship, in that on-screen

deaths ask significant questions about images of death.

84

Zombie narratives are important

ethically because they require the spectator to answer questions about what the zombies

represent:

These films are about death, corroding, rotting and dishevelled flesh, about breakdown

and dysfunctions of narrative, body, society and reality. That’s the very point. What does

it mean to live the organized body, society and cinematic image as part of coherent

narrative film? These images show the death of what?

85

Therefore, it remains important to analyse zombie films through a cinesexual framework, as

doing so helps to reveal how different spectators may perceive deaths differently.

84

Huntley, ‘Abstraction is Ethical’, p. 19.

85

MacCormack, Cinesexuality, p. 116.

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

18 (2020)

30

Maternal Femininity, Masquerade, and the Sacrificial Body in Charlotte

Dacre’s Zofloya, or The Moor

Reema Barlaskar

Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya, or The Moor (1806) is an unconventional tale about an aristocratic

woman dominated by her sadistic tastes and desires. It appropriates topics of erotic violence,

abandoned insatiability, and demonic love to engage a language of excess that eighteenth-

century critics described as too ‘shock[ing]’ for the ‘delicacy of a female pen [….] and mind’.

1

Such critical reviews, associating a female writer’s ‘pen’ with the ‘delicacy’ of her mind,

reflected a general rise in discourse about women’s education, conduct, and manners that, in

turn, shaped the moral rubric of contemporary novels.

2

As Dacre’s critics objected, the text’s

display of excess modes of desire, and extensive focus on libidinal femininity, transgress the

discursive boundaries prescribed to female reading and writing. Additionally, desire is not only

reflected in female figures but also in ‘rational’ male characters. However, as this essay argues,

when framed within earlier eighteenth-century representations of gender identity, the novel’s

display of provocative gender-bending suits the aesthetic practices of the eighteenth-century

masquerade.

Dacre articulates gender as a cultural performance reflective of the aesthetic and

discursive conventions produced by the masquerade, a public space providing individuals license

to explore and challenge the construction of gender identity.

3

In the masquerade, according to

Terry Castle, gender-related and social role reversals served as a popular mode of aesthetic

1

The eighteenth-century periodical The Annual Review’s response to Dacre’s novel can be found in the Broadview

Press edition of the novel. See Charlotte Dacre, Zofloya, or the Moor: A Romance of the Fifteenth Century, ed. by

Adrianna Craciun (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 1997), p. 10. All subsequent references to the main

fictional text within this article will be cited via a page number in the body of the article.

2

See Nancy Armstrong’s Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1987) for a discussion on eighteenth-century conduct manuals, the rise of the novel, and

feminisation of discourse; and Ann Mellor’s Romanticism and Gender (London: Routledge, 1992) for an

examination of political tracts and writings promoting a ‘moral revolution in female manners’ in response to the

French Revolution (p. 10). For discussions on gothic fiction and domesticity, see Kate Ellis’s The Contested Castle:

Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989), which

analyses how Ann Radcliffe’s gothic classics, The Mystery of Udolpho (1794) and The Romance of the Forest

(1791), domesticate the sublime in revealing the oppressive structure of the home, rather than portraying the terror

produced by nature, the focus of masculine gothic.

3

Terry Castle, Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction