American Fisheries Society Symposium 24:37–49, 1999

© Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 1999

37

Blue catfish Ictalurus furcatus are native to the

Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio River basins of cen-

tral and southern United States, and occupy Gulf

Coast streams from Alabama south into Mexico, and

northern Guatemala (Glodek 1980), and Belize

(Greenfield and Thomerson 1997). During the past

30 years they have been stocked into both Atlantic

and Pacific drainages. Blue catfish are considered a

big-river species. There is controversy over the physi-

cal appearance of blue catfish from various portions

of their native range because early workers were

confused by very large catfishes and described the

same species several times (Smith 1979), and blue

catfish from the Rio Grande River were considered

a subspecies (Knapp 1953). Previously, two subspe-

cies were recognized: I. f. furcatus in the central

United States and northern Mexico, and I. f.

meridionalis in eastern Mexico and Guatemala (Jor-

dan and Evermann 1896), however Lundberg (1992)

considers I. f. meriionalis conspecific with furcatus.

Recently, angling for blue catfish has become popu-

lar and several fishing-related television shows and

sporting magazines routinely address quality blue

catfish sportfisheries.

This paper summarizes the general biology and

life history of blue catfish, from a comprehensive

literature review, and from personal knowledge

gained from nearly 30 years of research on big river

species, including blue catfish. As I searched for ref-

erences, I was surprised at the shortage of technical

reports discussing life history and biology of the

species. I suspect that the shortage of information

on blue catfish results from the difficulty of ad-

equately sampling big river habitats. I also surveyed

48 state natural resource agencies about the status

of blue catfish.

Description

Blue catfish are the largest catfish in the United

States. The only freshwater fishes that reach larger

maximum sizes are alligator gar Lepisosteus spatula,

lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens, and white stur-

geon A. transmontanus. The current pole and line

record is 50.3 kg, from below Wheeler Reservoir,

Alabama, in 1996, however several states reported

that larger blue catfish have unofficially been caught.

Few authors provide total lengths, however Cross

(1967) reports a 139.7 cm, 40.5 kg blue catfish from

the Osage River in Missouri, in 1963, and a 165.1

cm, 45.2 kg blue catfish from the Missouri River in

South Dakota, in 1964. Like other catfishes, the blue

catfish is often described by several common names,

depending upon locality. Common names include:

white cat, white fulton, fulton, humpback blue,

forktail cat, and blue channel catfish. They are simi-

lar to channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus in appear-

ance, but differ in never having dark spots on their

A Review of the Biology and Management of Blue Catfish

KIM GRAHAM

Missouri Department of Conservation, Fish and Wildlife Research Center

1110 South College Avenue, Columbia, Missouri 65201-5299, USA

Abstract.—Blue catfish Ictalurus furcatus are a big river species, native to major rivers of the Mis-

sissippi River basin and Gulf Coast streams of the central and southern United States, south into

Mexico, northern Guatemala, and Belize. Blue catfish are native in 20 states and have been introduced

into nine others, mostly along the Gulf, Atlantic, and Pacific slopes. Blue catfish are largest of the

ictalurid catfishes, sometimes exceeding 45 kg and 165 cm, and can live over 20 years. Numbers in

their native range have been greatly reduced because of alteration of riverine habitats, particularly on

the periphery of their range. Blue catfish are migratory and prefer open waters of large reservoirs and

main channels, backwaters, and flowing rivers with strong current where water is normally turbid.

This species occurs over substrate varying from gravel/sand to silt/mud. Blue catfish are opportunistic

omnivores but adults eat a variety of animal life, including fish. Sexual maturity is usually attained at

4–7 years, and rapid growth is exhibited throughout life. Estimates of total annual mortality range

from 12 to 63%. Blue catfish are presently not popular with aquaculturists, but hybrids developed

with channel catfish I. punctatus are often used in fee-fishing lakes because of their rapid growth and

aggressive disposition. Blue catfish support sport fisheries in seven states, whereas 14 additional

states reported that they support both sport and commercial fisheries. About one-half of the 29 states

reporting blue catfish as present consider them economically and recreationally valuable. Nine states

reported they add diversity to existing fish populations, two manage them to develop quality or trophy

fisheries, and seven manage blue catfish for both.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM37

38 GRAHAM

back and sides (Pflieger 1997). Blue catfish in the

Rio Grande River, Texas, reportedly differ from other

blue catfish in that the juvenile and young are quite

speckled and many adults retain their spots (Wilcox

1960). Knapp (1953) reported that Rio Grande River

blue catfish have 35–36 anal fin rays, rather than

the usual 30–35. A major difference between blue

catfish and channel catfish is the configuration of

the air bladder (Pflieger 1997). The air bladder of

blue catfish has a definite constriction giving it a

two-lobed appearance, whereas the air bladder in

channel catfish is without constriction. Blue catfish

can be distinguished from channel catfish by the anal

fin which contains more rays (usually 30–35) and

its outer margin is straight and tapered like a barber’s

comb. Their tail is deeply forked, hence the Latin

name, furcatus, or forked, in reference to the tail.

Pflieger (1997) describes blue catfish as displaying

a distinctive wedge-shaped appearance because of

the high profile of the back near the dorsal fin. Un-

like the flathead catfish Pylodictis olivaris, which

also reaches large sizes, the lower jaw of blue cat-

fish never protrudes beyond the upper jaw. Color

can be variable, depending upon water clarity, but

most blue catfish larger than about 4.5 kg are pale

bluish-silver on the back and sides, grading to sil-

ver-white on the sides and white on the belly. Young

fish, 50–100 mm, are often nearly transparent, and

immature blue catfish, 250–450 mm, are usually

more silver or silver-white than adults, hence the

common name, “white cat.”

Distribution

Twenty-nine states reported having blue catfish

and 17 did not (Figure 1). Minnesota and Pennsyl-

vania considered the species extirpated. Pennsylva-

nia indicated that blue catfish were last reported in

the Monongahela River in 1886, and Minnesota re-

ported that they were once present in the Missis-

sippi and Minnesota rivers. In 1977, several thousand

were stocked in Lake St. Croix, Minnesota, and two

were captured the next year. Since then, no blue cat-

fish have been reported in Minnesota, and they are

currently considered a species of special concern.

The current distribution of blue catfish in the

United States is within the Mississippi River Basin,

and the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coastal slopes

(Figure 1). States not recording them are those in

the northeastern United States outside of the Ohio

River basin, the Great Lake states of Michigan and

Wisconsin, most Rocky Mountain states, and North

Dakota. During the Lewis and Clark expedition into

Montana, an interesting observation was made 22

May 1805: “Game was no longer in such abundance

since leaving the Musselshell and few fish were

caught and these were white catfish weighing two

to five pounds” (Coues 1965).

Sixteen states considered blue catfish to have

restricted distribution, while 13 states reported wide

distribution (Figure 1). Most of the states reporting

wide distribution are in the central and southeastern

United States. North Carolina reported that their

FIGURE 1. Distribution of blue catfish in the conterminous United States.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM38

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 39

native range of blue catfish is increasing within the

state. States reporting restricted distribution are those

bordering the Ohio River, upper Missouri River, west

coast, and southwestern states. Many of the states

reporting restricted distribution, including most of

the southwestern and western states and Florida,

have small populations resulting from introductions.

Virginia reported that blue catfish were intro-

duced in 1974, and that sport anglers indicate that

blue catfish may be replacing native channel catfish

populations in some areas of the state. Twenty states

reported blue catfish native, while nine indicated that

blue catfish in their respective states were introduced

(Figure 2). Most of the central, southern, and south-

eastern states report native populations of blue cat-

fish. Western and southwestern states of Washington,

Oregon, California, Arizona, Colorado, and eastern

and southeastern states of Maryland, Virginia, South

Carolina, and Florida have introduced blue catfish.

Washington and Oregon apparently introduced blue

catfish into the Snake River in the early 1900s, how-

ever they are presently extremely rare in both states.

California stocked them into large reservoirs in the

southern portion of the state in 1969. They adapted

well and currently provide sport fisheries. Also,

aquaculturists have developed hybrids with channel

catfish and routinely stock them in fee fishing lakes.

Arizona stocked blue catfish in a private pond in

1981 and report that they have never stocked them

in public waters, however they are known to exist in

extremely low numbers in the Colorado River sys-

tem. Blue catfish were stocked into reservoirs in the

eastern portion of Colorado in the Arkansas River

drainage in 1982. They were also stocked into the

Chesapeake Bay drainage in Virginia in 1974, in the

Potomac River in Maryland sometime between 1898

and 1905, and in the Escambia River drainage in

Florida, however these Florida introductions were

probably the result of escapees from Alabama, rather

than physical introductions. One of the most popu-

lar blue catfish fisheries is in Santee-Cooper Reser-

voir in South Carolina where blue catfish were

introduced, beginning in 1965.

Historical perspective

Records of large catfish date back to the Lewis

and Clark exploration of the Missouri River. They

described large “white” catfish, undoubtedly blue

catfish, reaching nearly 1.5 m in length. Heckman

(1950), in his Steamboating Sixty-Five Years on

Missouri’s Rivers, provides the following account:

“Of interest to fishermen is the fact that the largest

known fish ever caught in the Missouri River was

taken just below Portland, Missouri. This fish, caught

in 1866, was a blue channel cat and weighed 315 lb.

It provided the biggest sensation of those days all

through Chamois and Morrison Bottoms. Another

‘fish sensation’ was brought in about 1868 when two

men, Sholten and New, brought into Hermann, Mis-

souri, a blue channel cat that tipped the scales at

242 lb.” Heckman provides other evidence that it

was common to catch catfish weighing 125–200 lb

from the Missouri River during the mid 1800s. Even

Mark Twain, talked about seeing “a Mississippi cat-

fish that was more than six feet long” (Coues 1965).

FIGURE 2. Classification of blue catfish as native or introduced in the conterminous United States.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM39

40 GRAHAM

In November 1879, the U.S. National Museum re-

ceived a blue catfish weighing 150 lb from the Mis-

sissippi River near St. Louis. The fish was sent by

Dr. J. G. W. Steedman, chairman of the Missouri

Fish Commission, who purchased it in the St. Louis

fish market. The following quote from a letter from

Dr. Steedman to Professor Spencer F. Baird, U.S.

Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, suggests that

catfish of this size were not uncommon. “Your let-

ter requesting shipment to you of a large Missis-

sippi catfish was received this morning. Upon

visiting our market this afternoon, I luckily found

two—one of 144 lbs, the other 150 lbs. The latter I

shipped to you by express.”

Habitat

Blue catfish prefer open waters of large reser-

voirs and main channels, backwaters, and

embayments of large, flowing rivers where water is

normally turbid and substrate varies from gravel-

sand to silt-mud (Burr and Warren 1986). Many riv-

ers and reservoirs with blue catfish populations have

only mud or silt substrate. Blue catfish prefer deep,

swift channels and flowing pools (Jenkins and

Burkhead 1994), and large specimens were often

found in tailwaters below dams where currents were

swift and substrates consist of sand, gravel, and rock

(Mettee et al. 1996). Fish from these habitats are

extremely difficult to sample. Their affinity for swift

water and deep channels explains why blue catfish

life history is not well known. Although these cat-

fish can be stocked into small reservoirs to develop

specialized fisheries (Fischer et al. 1999, this vol-

ume), they are well suited to large, open-water res-

ervoirs, especially those with gizzard shad Dorosoma

cepedianum as forage (Graham and DeiSanti 1999,

this volume). Blue catfish tolerate moderately high

levels of salinity and can be grown in coastal waters

which does not exceed 8 ppt salinity for any extended

period of time (Perry and Avault 1970), however they

can tolerate salinity in estuaries to 11 ppt (Perry

1968), and in some waters at 14 ppt (Allen and Avault

1970).

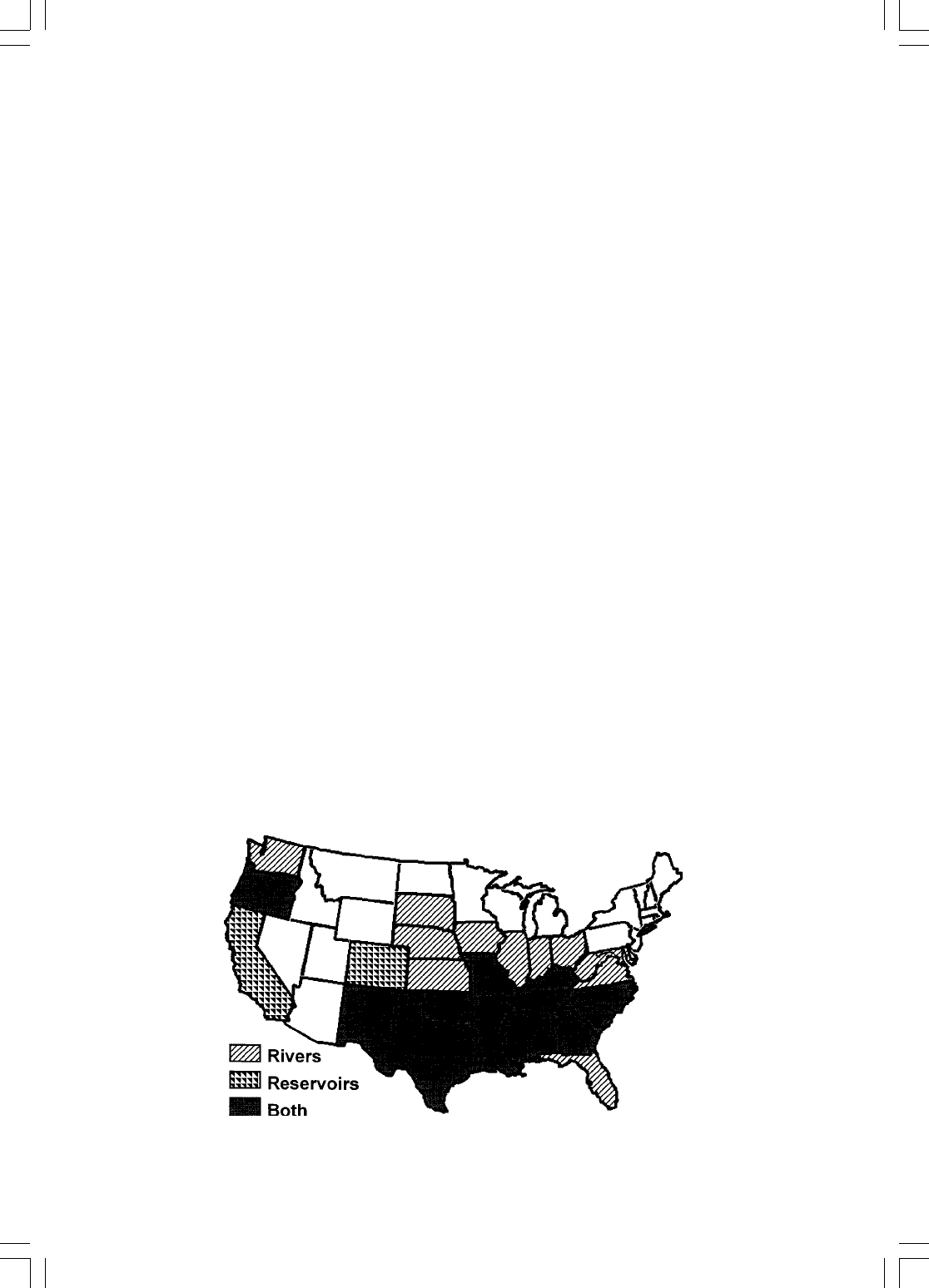

In twelve states, blue catfish are found prima-

rily in riverine habitats (Figure 3). All of these states,

except Florida and Washington, border the middle

and upper Missouri River or the northern borders of

the Ohio River and northeastern Atlantic slope states.

In Colorado and California, blue catfish are found

in reservoirs, and most of the states in the lower

Mississippi River basin, Gulf slope states, and south-

eastern Atlantic slope states (14 states) reported that

they are found in both rivers and reservoirs.

Movement

Blue catfish are the most migratory of the ictalurid

catfish, moving upstream in the spring and downstream

in the fall (Lagler 1961) in response to water tempera-

ture (Pflieger 1997). They move farther down the lower

Mississippi River where water is warmest in winter,

and upstream in summer (Jordan and Evermann 1916).

These migratory movements can span several hundred

km. Blue catfish moved considerably more during

spring than any other season in a 97-ha reservoir in

FIGURE 3. Primary waters with blue catfish in the conterminous United States.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM40

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 41

northwestern Missouri (Fischer et al. 1999). In Lake

of the Ozarks, Missouri, 75 of 1,500 (5%) stocked blue

catfish emigrated and were captured downstream by

anglers (Graham and DeiSanti 1999). Forty percent of

nearly 3,000 tagged blue catfish moved more than 16

km from their original point of capture. In Kentucky

Lake, Kentucky-Tennessee, a greater number of tagged

blue catfish moved upstream than down and their mean

distance traveled during the eight-year study (23.6 km)

was more than twice that of channel catfish (Timmons

1999, this volume). Blue catfish in the lower Missis-

sippi River moved 5–12 km from their release site af-

ter 363–635 d, and were more mobile than flathead

catfish (Pugh and Schramm 1999, this volume). Pugh

and Schramm also report that because of the fishes

ability to move great distances, blue catfish manage-

ment plans should consider a broad spatial scale. Long-

range movements, both upstream and downstream, are

common for large individuals as they seek spawning

sites.

Diet and feeding

A few published studies on food habits suggest

blue catfish were opportunistic and omnivorous feed-

ers. Blue catfish consume a variety of animal life,

including fishes, immature aquatic insects, crayfish,

fingernail clams, and freshwater mussels (Brown and

Dendy 1961; Minckley 1962; Perry 1969). In Cali-

fornia reservoirs, they were reported to eat Asiatic

clams Corbicula fluminea (Richardson et al. 1970).

Pflieger (1997) reported that blue catfish as small

as 100 mm ate some fish, but the bulk of their diet

was small invertebrates. Larger individuals, about

290 mm, ate mostly fish and larger invertebrates

(Perry 1969). In many large southern reservoirs, the

diet of large blue catfish was mostly gizzard shad or

threadfin shad Dorosoma petenense. Biologists along

the upper Mississippi River in Missouri, reported

that blue catfish were so gorged on freshwater mus-

sels one could see and feel mussel shells protruding

from the stomach wall. The senses of taste and smell

are more important than sight in locating food

(Robison and Buchanan 1988; Pflieger 1997); and

Pflieger (1997) suggested blue catfish feed mostly

on or near the bottom and to a lesser extent in the

midwater. In clear-water reservoirs, or tailwaters,

blue catfish capture their prey by sight. Mark Ambler

(Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation,

personal communication) reported that blue catfish

often suspend in deep water beneath schools of giz-

zard shad being fed upon by striped bass Morone

saxatilis, and seek and eat wounded and dead shad.

Before sophisticated fish-locating electronics, these

large catfish, often suspended 20 m from the bot-

tom, were inaccessible to anglers. Similarly, blue

catfish eat wounded gizzard shad after they pass

through the turbines of Harry S Truman Dam (Gra-

ham and DeiSanti 1999).

Sexual maturity and spawning

Maturity is generally reached at an earlier age

in the southern portion of their range than in the

north. Blue catfish mature at 4 or 5 years and at to-

tal lengths of 350–662 mm in Louisiana (Perry and

Carver 1973); Texas (Henderson 1972); and Ken-

tucky (Hale 1987; Hale and Timmons 1989). In the

Mississippi River near St. Louis, blue catfish become

sexually mature at about 381 mm (Barnickol and

Starrett 1951). Based on lengths of blue catfish cap-

tured in upper Lake of the Ozarks, Missouri, sexual

maturity is 420–480 mm, but at ages of 6–7 years

(Graham and DeiSanti 1999). In Louisiana, blue

catfish spawn in April through June (Perry and

Carver 1973), and early July in Iowa (Harlan et al.

1987).

The genital orifices of the two sexes are dis-

tinct (Moyle 1976). He reported that in the male,

the papilla is more prominent with a circular open-

ing; in the female, it is more recessed and the open-

ing slitlike. The testes of ictalurid catfishes are

morphologically different from most warmwater

fishes in that the glands are lobate and not compacted

into a solid-appearing gland (Sneed and Clemens

1963). They also report that the posterior one-fourth

of the testes is reduced and retains a pink color

throughout the year, but the anterior three-fourths

becomes progressively larger and whiter as the

spawning season approaches. Brooks et al. (1982)

report that when grading blue catfish (6- and 18-

month-old individuals) for future broodstock use, the

sex ratio was equal during simple grading for the

largest individuals, whereas when grading for the

largest channel catfish of the same age, the sex ratio

was dominantly males. They also report that the

weight-frequency distributions for 6- and 18-month-

old blue catfish were similar, but channel catfish

males were larger than females.

Spawning habits are relatively unknown

(Lagler 1961), but are believed to be similar to

those of channel catfish (Pflieger 1997; Hubert

1999, this volume). The species is a cavity nester.

Blue catfish seek protected areas behind rocks,

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM41

42 GRAHAM

root-wads, depressions, under cut streambanks, or

other areas where the currents are minimal to de-

posit eggs. Coker (1930) reports that mature eggs

of blue catfish attain a diameter of 2.5 mm,

whereas mature ova of 7–9 kg female blue catfish

were 3.0–3.3 mm in diameter (R. Dunham, Au-

burn University, personal communication). He

also stated that clutches of blue catfish fry from

spawns in ponds contained between 40,000 and

50,000 individuals. Hatching of eggs occurs in 7

or 8 d at water temperatures of 21⬚C to 24⬚C

(Henderson 1972; Pflieger 1997), and like most

other ictalurid catfishes, the male guards the eggs

and fry. Hatching success for blue catfish was es-

timated at 90%, and fry production per kg of fe-

male was higher for blue catfish than for channel

catfish (Tave and Smitherman 1982). Fecundity

estimates were from 900 to 1,350 eggs/kg of body

weight (Dunham, personal communication).

Survival and mortality

There was little information documenting mor-

tality of blue catfish, however, Kelley (1969) reported

a total annual mortality of blue catfish at 39% from

Tombigbee River, Alabama. In upper Lake of the

Ozarks, Missouri, blue catfish began to enter the

harvest at about 6 years of age and can contribute to

the sportfishery until they are 18 years of age (Gra-

ham and DeiSanti 1999). Total annual mortality es-

timates for this population ranged from 12 to 32%.

Because of rapid growth rates, these fish have the

capability to reach large sizes and provide high qual-

ity fisheries. Estimates of mortality for blue catfish

from Lake of the Ozarks were less than the 36–63%

reported from Kentucky Lake, Tennessee (Hale

1987). Hale also reported that catfish from Kentucky

Lake began entering the harvest at ages 4 and 5 and

contributed to the fishery until they were 13 years

of age.

Age and growth

Blue catfish growth is rapid, particularly after

they become piscivorous. Blue catfish growth rates

in upper Lake of the Ozarks, Missouri, were rela-

tively consistant between ages and sizes (Graham

and DeiSanti 1999). Growth of blue catfish in rivers

and reservoirs can be similar, if forage is adequate.

Growth rates of blue catfish in Lake Texoma, Okla-

homa, were reported to be more rapid than channel

catfish and nearly equal to flathead catfish (Jenkins

1956).

During the past 25 years, I have aged several

blue catfish from Missouri waters that exceeded

40 kg and 20 years. I determined catfish age and

growth rates by examining annual growth marks

on sections cut from pectoral spines, then back-

calculated annual growth (Marzolf 1955). Struc-

tures other than pectoral spines that are sometimes

used for aging include: opercular bones, vertebrae,

and dorsal spines (Ramsey and Graham 1991).

Increased growing season, warmer water, and of-

ten times, a more diverse forage base contribute

to faster growth in southern regions. Lengths at

age for blue catfish from several states (Table 1)

TABLE 1. Comparison of mean lengths (mm) of aged blue catfish from various populations and locations.

Tennessee Kentucky Kentucky Kentucky Kentucky Kentucky Barkley

Location River

a

Lake

b

Lake

b

Lake

c

Lake

d

Lake

e

Lake

d

State Tennessee Tennessee Tennessee Kentucky Kentucky Kentucky Kentucky

Age 1 135 142 145 132 76 117 76

2 198 229 239 221 165 213 188

3 252 287 295 274 239 310 302

4 297 343 356 318 302 391 376

5 356 401 427 363 311 480 455

6 429 447 483 424 432 559 584

7 513 500 551 485 483 627 658

8 582 423 627 549 564

9 699 551 671 584 666

10 846 587 607

11 693

12 737

13 813

Number

of fish 134 369 467 655 492 756 115

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM42

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 43

provides comparison, however caution must be

used because of differences in lengths of growing

seasons, ages of fish used in back-calculations,

and physical and chemical characteristics of the

aquatic environments. Blue catfish in the Rio

Grande River, Texas, grew at a faster rate than

fish in the 3-year-old Amistad Reservoir, Texas

(Henderson 1972), however, fish from different

sites within the reservoir grew at different rates.

Jenkins (1956) attributed decreasing growth rates

of blue catfish through 9 years in Lake Texoma,

Oklahoma, to inter-specific competition that oc-

curred as the fish community reached carrying

capacity. Intra-specific competition caused slow

growth of blue catfish in Kentucky Lake, Kentucky

(Conder and Hoffarth 1965), whereas growth im-

pairment of blue catfish in Kentucky Lake were

believed to be caused by both intra- and inter-spe-

cific competition (Freeze 1977). The fastest

growth rates for Kentucky Lake blue catfish are

believed to be in areas where intra-specific com-

petition was reduced by high harvest (Hale 1987).

In Oklahoma (Jenkins 1956) and Missouri

(Graham and DeiSanti 1999), blue catfish typi-

cally grew faster than channel catfish after the first

two years. In Missouri, growth rates remain

consistant among years through age 18 (Figure

4). Porter (1969) revealed that blue catfish in Ken-

tucky Lake, Tennessee, grew faster than channel

catfish, but displayed a slow, declining growth

rate. In another Kentucky Lake study, blue catfish

exhibited slow growth between ages 3 and 7 (Conder

and Hoffarth 1965), whereas average lengths of age

7 blue catfish in Barkley and Kentucky lakes were

12 and 4% greater, respectively, than age 7 channel

catfish (Freeze 1977). No significant differences in

growth patterns were found between sexes for blue

catfish (Hale 1987; Hale and Timmons 1990).

Population declines

Although populations of blue catfish are present

in several areas of the United States, primarily in

southern and southeastern states, blue catfish num-

Age 1 125 191 145 175 168 105

2 221 386 254 262 307 262 178

3 338 508 351 282 427 325 243

4 450 638 442 373 554 381 309

5 508 749 533 406 696 429 371

6 612 848 655 465 840 460 426

7 693 770 958 508 484

8 803 871 955 546 542

9 942 1,026 600

10 930 1,069 657

11 986 1,118 708

12 1,041 762

13 1,067 807

14 869

15 923

16 1,032

17 956

18 923

Number

of fish 122 57 190 103 93 2,389

a

Conder and Hoffarth (1965)

b

Hale and Timmons (1990)

c

Hale and Timmons (1989)

d

Freeze (1977)

e

Porter (1969)

f

Kelley (1969)

South South

State Alabama Louisiana Oklahoma Texas Carolina Carolina Missouri

Tombigbee Mississippi Lake Rio Grande Santee- Santee- Lake of

Location River

f

River Delta

g

Texoma

h

River

i

Cooper Lake

j

Cooper Lake

k

the Ozarks

l

TABLE 1. (continued.)

g

Kelley and Carver (1966)

h

Jenkins (1956)

i

Henderson (1972)

j

White and Lamprecht (1990)

k

White (1980)

l

Graham and DeiSanti (1999)

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM43

44 GRAHAM

bers are greatly reduced in waters in the periphery

of its native range. Declines are often associated with

aquatic habitat modification (stream channelization),

increased turbidity and siltation, changes in flow

regimes, drainage of natural standing water habi-

tats, industrial and domestic pollutants, pesticides,

and construction of impoundments. Before construc-

tion of impoundments on the upper Missouri River

and navigational locks and dams on the upper Mis-

sissippi and Ohio rivers, numbers of blue catfish were

higher. Trautman (1981) reports, “…it is obvious that

the readily-identifiable ‘Mississippi’ or ‘White’ cat-

fish was present before 1900 in the Ohio River be-

tween the Indiana state line and Belmont County.

The fishermen are in universal agreement that blue

catfish were far more abundant before the Ohio River

was ponded (before 1911) than it has been since, at

least many more fishes were caught before than af-

ter ponding.” The reduction in numbers of blue cat-

fish is directly correlated with the effort to remove

snags from the Missouri River to enhance early

steamboat travel (Hesse 1987). Hesse also reports

that channelization severely reduces the amount of

shallow water along a river, and confines fish to a

narrow, limited amount of habitat. Additionally, blue

catfish are apparently more sensitive to low dissolved

oxygen than channel catfish because they surface

before channel catfish in fish kills resulting from

low oxygen. According to sport anglers, blue cat-

fish are found dead more often than channel catfish

when harvested using trotlines in reservoirs having

thermoclines (R. Dent, Missouri Department of

Conservation, personal communication).

Fisheries

Because of their renowned qualities as a food

fish, sport and commercial fisheries are popular in

several states, and blue catfish are often found in

fish markets. Forbes and Richardson (1920) reported

that the flesh is of excellent quality and demands a

high price. According to Pflieger (1997), blue cat-

fish is a highly valued food fish because of its large

size and firm, well-flavored flesh. Blue catfish pro-

vide sport fisheries in seven states: the four

midwestern states of Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma,

and Colorado, the two western states of Washington

and California, and Florida in the southeastern

United States (Figure 5). Blue catfish support both

sport and commercial fisheries in 14 states, most of

which are in east-central and southeastern states

within the middle and lower Mississippi River and

Ohio River basins. No state considered the fish as

only a commercial species. Eight states on the pe-

riphery of their native range (Oregon in the west,

Arizona and New Mexico in the southwest, South

FIGURE 4. Length-weight relations for blue catfish from Alabama (log

10

W = -6.000 + 3.354 ⭈ log

10

L, N = 1,073),

Kentucky (log

10

W = -5.921 + 3.342 ⭈ log

10

L

,

N = 306), Missouri (log

10

W = -6.023 + 3.283 ⭈ log

10

L, N = 7,725), South

Carolina (log

10

W = -6.155 + 3.406 ⭈ log

10

L, N = 3,147), and Texas (log

10

W = -6.279 + 3.368 ⭈ log

10

L, N = 10,960).

Slopes for relationships from Kentucky and South Carolina overlay Missouri’s. State labels designate maximum size.

r

2

ⱖ 0.98 for all relations.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM44

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 45

Dakota and Iowa in the northern midwest, and Ohio,

West Virginia, and Maryland in the northeastern

United States) considered blue catfish populations

to be incidental in nature because their populations

are too small to support dependable sport or com-

mercial fisheries.

About one-half of the states where blue cat-

fish occur (15) considered the species

recreationally important. Blue catfish are consid-

ered recreationally valuable in most states within

the lower Missouri and Ohio River basins, and the

middle and lower Mississippi River basin, and in

Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and

Texas. They are not considered important sport

or commercial fish in western and southwestern

states, most upper midwest states, states in the

upper Ohio River basin and in Georgia and

Florida.

FIGURE 5. Status of sport, commercial, and incidental fisheries for blue catfish in the conterminous United States.

FIGURE 6. Management objectives for blue catfish in the conterminous United States.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM45

46 GRAHAM

Nine states reported that blue catfish add only

diversity to already existing fish populations (Fig-

ure 6). Two states indicated blue catfish provide

only quality and/or trophy fisheries, seven re-

ported they provide both diversity and quality and

trophy aspects, five states reported that blue cat-

fish were managed for other specific reasons, and

nine states reported that although blue catfish are

present in their state, they were not managed for

any specific purpose. States using blue catfish to

add diversity to fisheries include those states along

the lower Ohio and Mississippi River basins, and

Texas. Kansas and North Carolina were the only

states that manage their catfish as only quality or

trophy species, whereas seven states manage their

blue catfish populations for both diversity and

quality/trophy. Those seven states show no distri-

butional pattern by watershed. They range from

California in the west to Virginia in the east, and

to Florida in the south. Five states indicated that

their blue catfish populations were managed for

specific reasons. Nebraska stocked blue catfish

into several small public lakes to increase diver-

sity, however they no longer stock them and their

few remaining blue catfish are managed similar

to channel catfish. California stocked blue catfish

for Asiatic clam control and for aquaculture pur-

poses, probably as hybrids with channel catfish,

in pay lakes. Arkansas managed blue catfish for

shad control, and Alabama and Louisiana man-

aged them specifically for sport and commercial

fisheries. It was not surprising that nine states,

most of which are on the periphery of their native

range, do not manage for them. In most cases, blue

catfish numbers were low and sometimes provided

only accidental or unplanned fisheries.

Commercial harvest estimates were reported from

only nine states (Table 2). States with harvest estimates

were those along the middle and lower Mississippi

River basin, the lower Ohio River basin, and South

Carolina. Sport harvest estimates were available from

only five states (Table 2). These estimates were diffi-

cult to evaluate because in many cases not all blue cat-

fish sport fisheries had creel surveys. For example, in

Missouri, our sport harvest estimates were from only

two large reservoirs, yet there are blue catfish sport

fisheries in several mid-sized public lakes and sport

angling is becoming more popular on the Missouri and

Mississippi rivers. It appears that the highest sport har-

vests occur in Tennessee and South Carolina, and al-

though Alabama considers blue catfish an important

sport fish with high harvest, they had no estimates.

Due to self reporting, commercial fisheries sta-

tistics were difficult to evaluate. It appears that Loui-

siana, Kentucky, and Arkansas had the largest blue

catfish commercial harvests.

Culture

Blue catfish possess several attributes that make

them desirable for culture in temperate regions (Tidwell

and Mims 1990; Webster et al. 1995). Blue catfish have

a similar or higher dressing percentage than channel

catfish, have an aggressive nature making them suit-

able for pay-lakes (fee fishing) industry, and resistant

to some diseases that affect channel catfish, such as

enteric septicemia and channel catfish virus. Giudice

(1970) and Chappell (1979) report that a major advan-

tage to blue catfish in aquaculture was that they were

relatively easy to seine from ponds and they have high

individual weight gains in temperate regions (Tidwell

and Mims 1990).

Alabama NA 356–457 NA None

Arkansas NA NA 905,891 406

Illinois NA NA 345,098 381

Indiana NA NA <22,222 254

Kentucky 72,171 351 2,031,706 None

Louisiana 46,667 356–381 4,888,889 305

Mississippi NA NA 48,0431 305

Missouri 85,822 599 79,947 381

South Carolina 971,904 356-610 414,889 None

Tennessee 1,381,409 516 411,153 None

Virginia NA NA NA None

TABLE 2. Estimates of sport and commercial harvests (kg), mean size (mm), harvested by sport anglers, and mini-

mum sizes (mm) in the commercial harvest for blue catfish from various populations, as reported by state natural

resource agencies.

Sport Commercial

State Harvest (kg) Average sizes (mm) Harvest (kg) Minimum size (mm)

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM46

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 47

However, blue catfish are currently unpopular with

the aquaculture industry because of reported slow matu-

ration rates, poor food conversion, and poor spawning

success in captivity. Some aquaculturists believed that

blue catfish were more easily stressed and more sus-

ceptible to bacterial diseases than channel catfish, es-

pecially after handling or hauling.

Hybridization between blue catfish and chan-

nel catfish increases growth (Giudice 1966; Giudice

1970; Yant et al. 1976; Chappell 1979; Tave et al.

1981). Chappell (1979) reported that the hybrid pro-

duced by crossing male blue catfish with female

channel catfish had a faster growth rate, exhibited

greater feeding vigor, and had a better food conver-

sion and dressing percentage than either parent spe-

cies. Tave et al. (1981) indicated that these hybrids

were more susceptible to angling than either parent,

and that fishing success in pay lakes could be im-

proved by stocking hybrids.

Summary

Blue catfish are widely distributed in the United

States but restricted to states within the Mississippi

River basin and Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coast

slopes. Numbers of blue catfish generally increase

southward in the United States. It is a large river

species and the largest of all North American cat-

fishes. Its ability to reach large sizes makes the blue

catfish one of the most popular catfishes for pole

and line anglers. Blue catfish grow rapidly, are rela-

tively easy to catch, and the flesh is white, flakey,

and of extremely good texture. Commercially, the

blue catfish is a recreationally valuable species.

During the past several years, it has been introduced

into several states as a trophy species, to increase

species diversity for anglers, and as a predator to

control shad and Asiatic clams. Blue catfish popu-

lations will probably not expand their range substan-

tially in the near future because of their apparent

affinity for warmer climates, however those states

where blue catfish are already popular will likely

continue to manage the species a valuable sport and

commercial fish.

References

Allen, K. O., and J. W. Avault, Jr. 1970. Effects of salinity

on growth and survival of channel catfish, Ictalurus

punctatus. Proceedings of the Annual Conference

Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commis-

sioners 23(1969):319–331.

Barnickol, P. G., and W. C. Starrett. 1951. Commercial and

sport fishes of the Mississippi River between

Caruthersville, Missouri, and Dubuque, Iowa. Bulletin

of the Illinois Natural History Survey 25(5):267–350.

Brooks, M. J., R. O. Smitherman, J. A. Chappell, and R.

A. Dunham. 1982. Sex-weight relations in blue, chan-

nel, and white catfishes: implications for brood stock

selection. Progressive Fish-Culturist 44:105–107.

Brown, B. E., and J. S. Dendy. 1961. Observations on the

food habits of the flathead and blue catfish in Ala-

bama. Proceedings of the Annual Conference South-

eastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners

15(1961):219–222.

Burr, B. M., and M. L. Warren, Jr. 1986. A distributional

atlas of Kentucky fishes. Kentucky Nature Preserves

Commission Scientific and Technical Series 4.

Chappell, J. A. 1979. An evaluation of twelve genetic

groups of catfish for suitability in commercial pro-

duction. Doctoral dissertation. Auburn University,

Auburn, Alabama.

Coker, R. E. 1930. Studies of common fishes of the Mis-

sissippi River at Keokuk. U.S. Bureau of Fisheries

Bulletin 45(1929):141–225.

Conder, J. R., and R. Hoffarth. 1965. Growth of channel

catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, and blue catfish,

Ictalurus furcatus, in the Kentucky Lake portion of

the Tennessee River in Tennessee. Proceedings of the

Annual Conference Southeastern Association of

Game and Fish Commissioners 16(1962):348–354.

Coues, E., editor. 1965. History of the expedition under

the command of Lewis and Clark, volume 1. Dover

Publications Inc., New York.

Cross, F. B. 1967. Handbook of fishes of Kansas. Univer-

sity of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscella-

neous Publication 45.

Fischer, S. A., S. Eder, and E. D. Aragon. 1999. Move-

ments and habitat use of channel catfish and blue

catfish in a small impoundment in Missouri. Pages

239–255 in Irwin et al. (1999).

Forbes, S. A., and R. E. Richardson. 1920. The fishes of

Illinois (2nd edition). Illinois Natural History Sur-

vey, Urbana.

Freeze, T. M. 1977. Age and growth, condition, and length-

weight relationships of Ictalurus furcatus and

Ictalurus punctatus from Barkley and Kentucky lakes,

Kentucky. Master’s thesis. Murray State University,

Murray, Kentucky.

Giudice, J. J. 1966. Growth of a blue x channel catfish

hybrid compared to its parent species. Progressive

Fish-Culturist 28:142–145.

Giudice, J. J. 1970. Catfish breeding, selection and hy-

bridization. Pages 12–15 in J. G. Dillard, editor. Pro-

ceedings of the Missouri catfish conference.

Extension Division Publication 296, University of

Missouri, Columbia.

Glodek, G. S. 1980. Ictalurus furcatus (LeSueur) blue

catfish. Page 439 in D. S. Lee, et al. Atlas of North

American freshwater fishes. North Carolina State

Museum of Natural History, Raleigh.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM47

48 GRAHAM

Graham, K., and K. DeiSanti. 1999. The population and

fishery of blue catfish and channel catfish in the Harry

S Truman Dam tailwater, Missouri. Pages 361–376

in Irwin et al. (1999).

Greenfield, D. W., and J. E. Thomerson. 1997. Fishes of

the continental waters of Belize. University Press of

Florida, Gainesville.

Hale, R. S. 1987. Commercial catch analysis, spawning

season, and length at maturity of blue catfish in Ken-

tucky Lake, Kentucky-Tennessee. Master’s thesis.

Murray State University, Murray, Kentucky.

Hale, R. S., and T. J. Timmons. 1989. Comparative age

and growth of blue catfish in the Kentucky portion of

Kentucky Lake between 1967 and 1985. Transactions

of the Kentucky Academy of Science 50(1-2):22–26.

Hale, R. S., and T. J. Timmons. 1990. Growth of blue cat-

fish in the lacustrine and riverine areas of the Ten-

nessee portion of Kentucky Lake. Journal of the

Tennessee Academy of Science 65(3):86–90.

Harlan, J. R., E. B. Speaker, and J. Mayhew. 1987. Iowa

fish and fishing. Iowa Department of Natural Re-

sources, Des Moines.

Heckman, W. L. 1950. Steamboating sixty-five years on

Missouri’s rivers. Burton Publishing Company, Kan-

sas City, Missouri.

Henderson, G. G. 1972. Rio Grande blue catfish study.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Federal Aid in

Fisheries Restoration Project F-18-R-7, Job 11,

Progress Report, Austin.

Hesse, L. W. 1987. The catfish. Pages 18–23 in The fish

book. NEBRAKSAland Magazine 65(1), Nebraska

Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln.

Hubert, W. A. 1999. Biology and management of channel

catfish. Pages 3–22 in Irwin et al. (1999).

Irwin, E. R., W. A. Hubert, C. F. Rabeni, H. L. Schramm,

Jr., and T. Coon, editors. 1999. Catfish 2000: pro-

ceedings of the international ictalurid symposium.

American Fisheries Society, Symposium 24,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Jenkins, R. M. 1956. Growth of blue catfish (Ictalurus

furcatus) in Lake Texoma. The Southwest Naturalist

1(4):166–173.

Jenkins, R. E., and N. M. Burkhead. 1994. Freshwater

fishes of Virginia. American Fisheries Society,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Jordan, D. S., and B. W. Evermann. 1896. The fishes of

north and middle America. Bulletin of the United

States National Museum 47(1):134–135.

Jordan, D. S., and B. W. Evermann. 1916. American food

and game fishes. Doubleday, Page and Company, New

York.

Kelley, Jr., J. R. 1969. Growth of blue catfish Ictalurus

furcatus (LeSueur) in the Tombigbee River of Ala-

bama. Proceedings of the Annual Conference South-

eastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners

22(1968):248–255.

Kelley, Jr., J. R., and D. C. Carver. 1966. Age and growth

of blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus (LeSuer) in the re-

cent delta of the Mississippi River. Proceedings of

the Annual Conference Southeastern Association of

Game and Fish Commissioners 19(1965):296–299.

Knapp, F. T. 1953. Fishes found in the fresh waters of

Texas. Ragland Studio and Litho Printing Company,

Brunswick, Georgia.

Lagler, K. F. 1961. Freshwater fishery biology. William

C. Brown Company, Dubuque, Iowa.

Lundberg, J. G. 1992. The phylogeny of ictalurid catfishes:

a synthesis of recent work. Pages 392–420 in R. L.

Maiden, editor. Systematic, historical ecology, and

North American freshwater fishes. Stanford Univer-

sity Press, Stanford, California.

Marzolf, R. C. 1955. Use of pectoral spines and vertebrae

for determining age and rate of growth of the chan-

nel catfish. Journal of Wildlife Management

19(2):243–250.

Mettee, M. F., P. E. O’Neil, and J. M. Pierson. 1996. Fishes

of Alabama and the mobile basin. Oxmoor House,

Inc., Birmingham, Alabama.

Minckley, W. L. 1962. Spring foods of juvenile blue cat-

fish from the Ohio River. Transactions of the Ameri-

can Fisheries Society 91(1):95.

Moyle, P. B. 1976. Inland fishes of California. University

of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Perry, Jr., W. G. 1968. Distribution and relative abundance

of blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, and channel cat-

fish, Ictalurus punctatus, with relation to salinity.

Proceedings of the Annual Conference Southeastern

Association of Game and Fish Commissioners

21(1967):436–444.

Perry, Jr., W. G. 1969. Food habits of blue catfish and chan-

nel catfish collected from a brackish water habitat.

Progressive Fish-Culturist 31(1):47–50.

Perry, Jr., W. G., and J. W. Avault. 1970. Culture of blue

catfish and white catfish in brackish water ponds.

Proceedings of the Annual Conference Southeastern

Association of Game and Fish Commissioners

23(1969):592–605.

Perry, Jr., W. G., and D. C. Carver. 1973. Length at matu-

rity and total length-collarbone length conversions

for channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, and blue cat-

fish, Ictalurus furcatus, collected from the marshes

of southwest Louisiana. Proceedings of the Annual

Conference Southeastern Association of Game and

Fish Commissioners 26(1972):541–553.

Pflieger, W. L. 1997. The fishes of Missouri. Missouri

Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Porter, M. E. 1969. Comparative age, growth, and condi-

tion studies on the blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus

(LeSuer), and the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus

(Rafinesque), within the Kentucky waters of Kentucky

Lake. Master’s thesis. Murray State University,

Murray, Kentucky.

Pugh, L. L., and H. L. Schramm, Jr. 1999. Movement of

tagged catfishes in the lower Mississippi River. Pages

193–197 in Irwin et al. (1999).

Ramsey, D., and K. Graham. 1991. A review of literature on

blue catfish and channel catfish in streams. Missouri

Department of Conservation, Dingell-Johnson Project

F-1-R-40, Study S-38, Final Report, Columbia.

Richardson, W. M., J. A. St. Amant, L. J. Bottroff, and W.

L. Parker. 1970. Introduction of blue catfish into Cali-

fornia. California Fish and Game 56(4):311–312.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM48

BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF BLUE CATFISH 49

Robison, H. W., and T. M. Buchanan. 1988. Fishes of Ar-

kansas. University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville.

Smith, P. W. 1979. The fishes of Illinois. University of

Illinois Press, Urbana.

Sneed, K. E., and H. P. Clemens. 1963. The morphology

of the testes and accessory reproductive glands of the

catfishes (Ictaluridae). Copeia 1963(4):606–611.

Tave, D., A. S. McGinty, J. A. Chappell, and R. O.

Smitherman. 1981. Relative harvestability by angling

of blue catfish, channel catfish, and their reciprocal

hybrids. North American Journal of Fisheries Man-

agement 1:73–76.

Tave, D., and R. O. Smitherman. 1982. Spawning success

of reciprocal hybrid pairings between blue and chan-

nel catfishes with and without hormone injection.

Progressive Fish-Culturist 44(2):73–74.

Tidwell, J. H., and S. D. Mims. 1990. A comparison of

second-year growth of blue catfish and channel cat-

fish in Kentucky. Progressive Fish-Culturist

52(3):203–204.

Timmons, T. J. 1999. Movement and exploitation of blue

and channel catfish in Kentucky Lake. Pages 187–

191 in Irwin et al. (1999).

Trautman, M. B. 1981. The fishes of Ohio. Ohio State

University Press, Columbus.

Webster, C. D., J. H. Tidwell, L. S. Tiu, and D. H. Yancey.

1995. Use of soybean meal as partial or total substi-

tute of fish meal in diets for blue catfish (Ictalurus

furcatus). Aquacultural Living Resources 8:379–384.

White, M. G., III. 1980. Blue catfish age and growth studies.

South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Depart-

ment. South Carolina Federal Aid to Fish Restoration,

Project F-16-10, Job Completion Report, Columbia.

White, M. G., III, and S. D. Lamprecht. 1990. Fishing

mortality of large catfish in lakes Marion and

Moultrie, relative to type of fishing. South Carolina

Wildlife and Marine Resources Department. South

Carolina Federal Aid to Fish Restoration, Project F-

16-20. Job Completion Report, Columbia.

Wilcox, J. F. 1960. Experimental stockings of Rio Grande

blue catfish, a subspecies of Ictalurus furcatus, in

Lake J. B. Thomas, Colorado City Lake, Nasworthy

Lake, Lake Abiline, and Lake Trammel. Texas Game

and Fish Commission, Dingell-Johnson Project F-5-

R-7, Job E-2, Job Completion Report, Austin.

Yant, D. R., R. O. Smitherman, and O. L. Green. 1976.

Production of hybrid (blue x channel) catfish in ponds.

Proceedings of the Annual Conference Southeastern

Association of Game and Fish Commissioners

29(1975):82–86.

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM49

50 GRAHAM

CATGraham63.p65 01/28/2000, 9:03 AM50