324

324-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

ISSN 1679-3951

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Abstract

Keywords:

Ensaio teórico sobre as avaliações de políticas públicas

Resumo

Palavras-chave

Ensayo teórico sobre las evaluaciones de políticas publicas

Resumen

Palabras clave:

DOI:

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

325-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

INTRODUCTION

Although widely discussed in Brazil and in the world, the term “public policy” may adopt several meanings. According to

Secchi (2014), lan-speaking countries nd it dicult to disnguish two terms from the English language: polics and policy.

For Bobbio, Maeucci and Pasquino (1998), the rst refers to a set of human acvies pertaining to the polis or to the

State; and, according to Secchi (2014), the second denotes something more concrete, that has relaon with acons, and

decisions. Thus, “public policy” is aligned with the meaning of policy, i.e., it refers to the process of polical construcon,

acng, and decision. It may be said that public policy is closely linked to state acons, however, there are other currents of

thought that indicate a mul-centric scenario (SECCHI, 2014). In the mul-centered approach, there appears a network of

public policy made up of government actors, private and non-governmental organizaons, and mullateral organizaons

(FREY, 2000; SECCHI, 2014). From the conceptual point of view, besides involving several actors in the formulaon or

implementaon, public policies are muldisciplinary and have an impact on the economy, and sociees (SOUZA, 2006;

HOWLETT, RAMESH and PERL, 2013). In view of the aforemenoned denions, we may infer that the study of public policy

is a complex phenomenon with a mulplicity of actors internal or external to the State (HOWLETT, RAMESH and PERL, 2013).

Consequently, the search for analycal processes is a way to reduce the complexity of the object and to simplify the analysis.

In order to do so, the division into stages was established, under the aegis of the policy cycle and in relaon to the various

phases of the polical process arranged in a sequenal and interdependent way (FREY, 2000; HOWLETT, RAMESH and PERL,

2013; SECCHI, 2014). Among the formats observed in the literature, we have chosen to describe the applied resoluon of

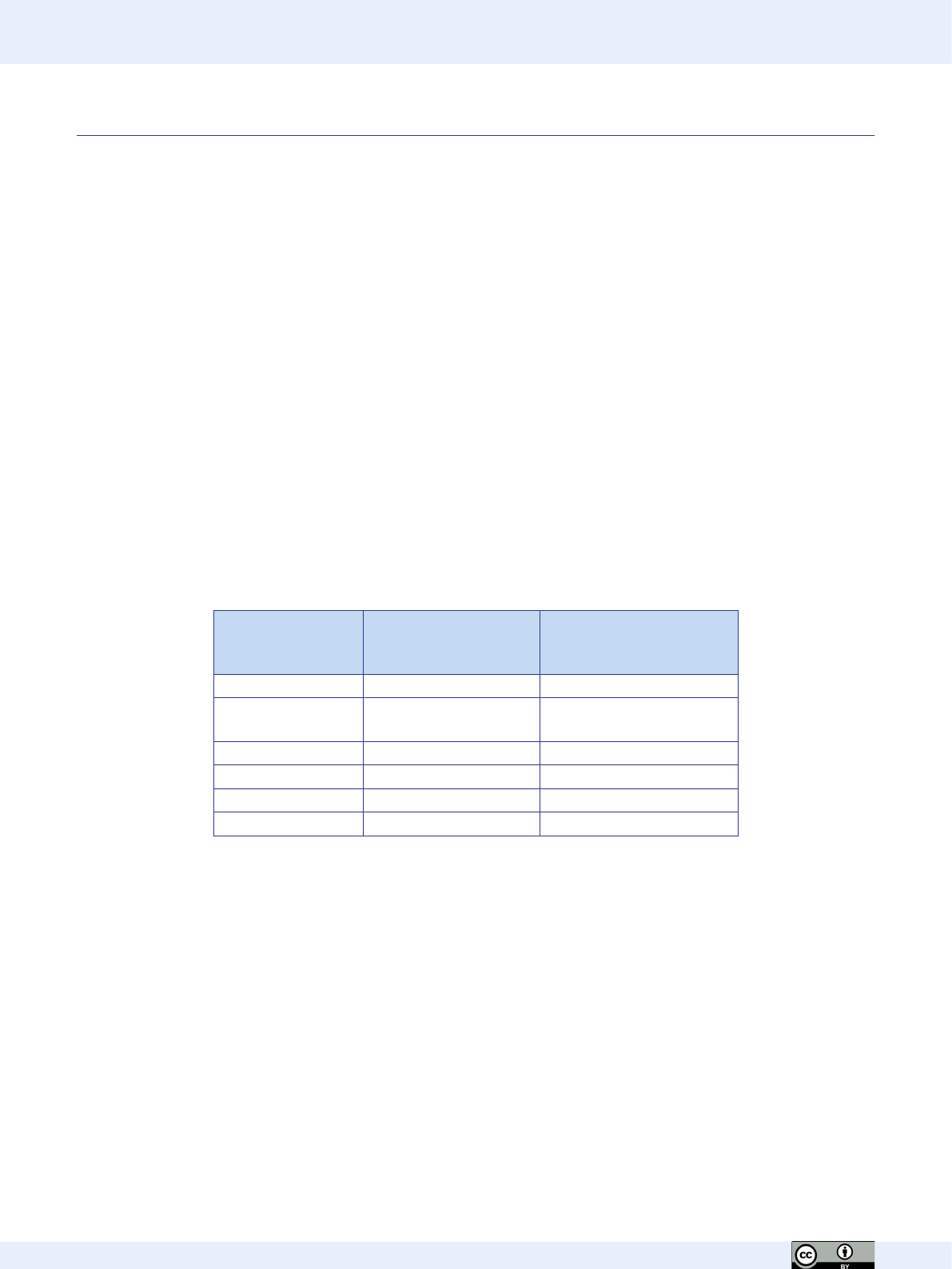

problems and the stages corresponding to the polical cycle, based on Howle, Ramesh and Perl (2013) and Secchi (2014)

– Box 1 summarizes these connecons.

Applied problem

resoluon

Polical cycle stage

according to Howle,

Ramesh e Perl (2013)

Polical cycle stage

according to Secchi (2014)

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Since it is a holisc eld with several unfolding events, this study proposes to specically analyze the historical process of

structuring one stage of the polical cycle, namely evaluaon. Given its conceptual, methodological, and developmental

importance, the evaluaon of public policies, public programs, or public processes is included in the contemporary research

agenda as an essenal tool for the improvement of public policies in all spheres of government, and in the global scenario. The

United Naons (UN), the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Organizaon for Economic Co-operaon

and Development (OECD), the Economic Commission for Lan America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and the Lan American

Center for Public Administraon and Development (Clad) emerge as protagonists in the generaon of methodologies, and

evaluave projects (RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012).

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

326-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

The eecve use of evaluave processes can contribute to the transparency of public acts, as well as to present forms of

control and monitoring of governmental acons to cizens, thus guaranteeing the legimacy of the policies or programs

developed (WEISS, 1999; ALA-HARJA and HELGASON, 2000; MOKATE, 2002; VEDUNG, 2009; RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012).

Nevertheless, it is worth nong that, because of its polical nature, evaluaons can contribute to the maintenance or not of

a certain policy, somemes linked to the proposions and strategies of the pares involved (RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012;

ARRETCHE, 2001; CRUZ, 2015).

Carvalho (1999) notes that the evaluaon presents a high degree of complexity and specicity, factors that increase the diculty

in incorporang the evaluave acvity in the day-to-day of the administrators, since there are mulple actors, objecves,

causes, eects, and outcomes. In this sense, in order to contribute to the debate on public policy evaluaon, this arcle

devotes the next topics to the historical rescue of the study of the evaluaon, as well as to the details of the exisng models,

types, and methodologies in the literature and recent internaonal trends inserted in this discussion. For the construcon

of this theorecal essay, we opted for advanced search in the following databases: SCOPUS, Web of Science, Google Scholar,

SciELO, USP Bank of Theses and Dissertaons, VHL, and Capes Journal Portal. The main keywords of the research were:

“public policies”; “evaluaon”; and “public policy evaluaon”. Nevertheless, this search also resulted in an amplicaon of

the literature through the arcles analyzed.

THEORETICAL REVIEW

The literature considers the end of the 1950s as a cornerstone of the evaluave studies. According to Vedung (2010), the

historical process of studies on evaluaon in the global context can be divided into four diusion waves. Each wave is indicated

for a period of me and coined according to social, polical, and economic issues. The construcon of this metaphor refers

to the constant renewal of the scenario resulng from the repeve movement of the waves and the constant sediment

deposits for the creaon of a base (VEDUNG, 2010). Using this theorecal framework, we opt for describing the evoluon of

the evaluave studies using Vedung’s diusion wave concepon (2010).

The rst wave, or diusion phase of the evaluaon studies, dates back to the late 1950s, consolidated in the mid-1960s

(DERLIEN, 2001; TREVISAN and BELLEN, 2008; VEDUNG, 2010; PICCIOTTO, 2015), and is characterized as “the wave oriented

to science” (VEDUNG, 2010). The studies belonging to this period in me are related to the emergence of the Welfare State,

especially in the countries with reformist aspiraons in that period, especially United States of America (USA), France, Germany,

Sweden, and Canada (DERLIEN, 2001; VERDUNG, 2010; PICCIOTTO, 2015).

The main objecves of the studies of this phase were following up and analyzing the results of the policies implemented;

Derlien (2001) aributes to this set of studies the informaon funcon. These are evaluaons with the purpose of assessing

the eects and results of the policy or program, as well as idenfying possible posive or negave consequences. These

studies also aimed to verify points to be improved and to indicate recurrent failures (DERLIEN, 2001). “The focus was on the

improvement of the program, and administrators were interested in using evaluaon as a feedback mechanism” (TREVISAN

and BELLEN, 2008, p. 537). For Vedung (2010), it was during this period that evaluaons emerged from a context of radical

raonality; the structure of evaluave thinking was guided by the noon of “sciencaon” of processes of public policy, and

public administraon. The evaluaon would bring to the government an air of raonality with a scienc and fact-based scaold

(ROSSI and WRIGHT, 1984; WEISS, 1999; VEDUNG, 2010). In his paper on public sector reform, Thoenig (2000) reinforces the

raonality described by Vedung (2010) and conrms the informaon funcon proposed by Derlien (2001), stang that if the

use of evaluaon is oriented to acon, it must concentrate on providing usable knowledge. For the author, the evaluaon is

much more likely to be accepted if its informaonal aspect is emphasized (THOENIG, 2000).

The second me period, or the second wave described by Vedung (2010), named “dialogue-oriented wave”, dates back to

the mid-1970s, in a context in which researchers argued that assessments should be more pluralisc, driven by progressive

ideals (VEDUNG, 2010; PICCIOTTO, 2015).

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

327-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

It is discussed the inseron of all the actors involved in the intervenon to be analyzed, from researchers and policians to

operators of the policy or program in queson (VEDUNG, 2010). Rossi and Wright (1984) emphasize the growth in the use of

qualitave research in this period, a model that is convergent to the inclusive thinking of the me, jusfying its use based on

the lower costs of these surveys at the local level, and with greater ulity and exibility for administrators. These evaluave

models would support beer the parcipatory comprehensiveness and would bring greater contact with reality (ROSSI

and WRIGHT, 1984; VEDUNG, 2010). Summing up the characteriscs of this wave, Vedung (2010, p. 270, our translaon)

explains that, “in contrast to the science-induced wave, the dialogue-oriented wave rested on communicave raonality.

Instead of producing truths, a dialogic evaluaon would generate broad agreements, consensus, polical acceptability, and

democrac legimacy”.

On the other hand, the third wave, named by Vedung (2010) “neoliberal wave”, introduced in the early 1980s, modied once

again the evaluaon studies standard. Vedung (2010) and Piccioo (2015) describe this period as a neoliberal ood in the

eld of evaluave studies, focusing on reducing the state, and promong free market and public-private partnerships. In the

USA, the new evaluave concepons followed the dismantling of social programs promoted by Ronald Reagan (ROSSI and

WRIGHT, 1984). The emerging management model was the New Public Management (NPM), with greater focus on results in

relaon to the processes. Vedung (2010, p. 270, our translaon) complements by arguing that “decentralizaon, deregulaon,

privazaon, civil society and, in parcular, customer orientaon have become new slogans. Previously considered the soluon

to the problems, the public sector had become the problem to be solved”. Derlien (2001) aributes the mapping funcon to

this wave, and the studies focus on diagnosing the policies or programs that can be cut based on the negave results presented

and on the consequences of the privazaon of certain state funcons or acvies; nancial eciency in the conducon of

public policies and programs is aimed at (DERLIEN, 2001).

In their contribuon, Ala-Harja and Helgason (2000) indicate that, in this phase, evaluaon was understood as a tool capable

of jusfying policies and reallocang nancial resources. At the governmental level, the evaluators focus on the Ministry of

Finance and audit organs. In conclusion, Vedung (2010) summarizes that the evaluaon acvies of the third wave were

mainly directed to accountability, performance measurement and consumpon, search for the quality of services provided,

and comparave evaluaons.

Following, the fourth and last wave described by Vedung (2010) is called “wave of evidence: the return of experimentaon”.

This wave of evaluave studies took shape in the decades of 1990 and 2000, especially in the North Atlanc and Nordic

countries. These are evidence-based studies and, in this sense, Piccioo (2015) emphasizes that those involved in assessment

studies are “surng” this fourth wave. Studies focused on scienc evidence aim to separate what works from what does not

work (VEDUNG, 2010; PICCIOTTO, 2015).

The authors highlight that studies with experimental approaches, by using randomizaon (control and treatment groups) or

quasi-experimental, have as main objecve the vericaon of the impacts caused by the public policy or program (VEDUNG,

2010; PICCIOTTO, 2015). Complementarily, Silveira, Vieira, Capobiango et al. (2013) resume the concept of evaluaon that

seeks to understand and know the consequences of an acon, as well as to ancipate its possible results. In the meanwhile,

internaonal organizaons, academics, and governments began to perform systemac reviews of the literature, in order to

strengthen the research bases, guaranteeing greater raonality to the process. Vedung (2010) classies this movement of

incessant search for scienc evidence as a return to the science-based model, however, with a new style. In Derlien’s view

(2001, p. 107, our translaon), evaluaon at this me has the funcon of legimaon: “it is believed that scienc evidence

juses polical decisions, either to improve, reduce or eliminate programs.”

In view of the internaonal panorama presented, it is necessary to make a geographical breakdown for the discussion on the

evaluaon studies eld in Brazil. Unlike the countries with a long tradion of evaluang public policies and programs, Brazil

entered at a late me in this phase of the polical cycle. According to Mokate (2002, p. 90, our translaon):

Despite what has been said and according to what was published about the importance of evaluaon

processes, it is sll uncommon to nd social programs or policies in Lan America that have a rigorous

systemac evaluaon process incorporated into daily processes of administraon and decision-making.

The concern about evaluang public policies or programs is something that has recently been incorporated into the polical

agenda, since administrators’ priority was channeled into the policy formulaon process, with lile emphasis on the other

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

328-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

stages of the cycle (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003; ALVES and PASSADOR, 2011; CRUMPTON, MEDEIROS, FERREIRA et al., 2016).

This incorporaon was reported in the mid-1980s, aer the experience of structural reforms in the state apparatus proposed

in various parts of the world, in order to reduce government costs and make it more ecient (PAULA, 2005). Therefore, a

greater and less fragmented use of evaluaon in Brazil only appears during the third wave described by Vedung (2010) or

during the legimizaon funcon proposed by Derlien (2001).

On the other hand, the adopon of evaluave pracces in countries such as Brazil aims at strengthening instuonal

arrangements and providing administrators with an analysis of the policies adopted (CRUMPTON, MEDEIROS, FERREIRA et

al., 2016). In their study, Crumpton, Medeiros, Ferreira et al. (2016) compared the evaluave studies carried out in Brazil and

the USA, in order to present the degree of establishment of this type of research in the countries; as a result, it is found that,

unlike the USA, the area of research in evaluaon is not fully established in Brazil, although there is an eort on the part of

the researchers to change this picture.

It is believed that, in the Brazilian case, the public databases available present reliability problems (some have declared

data), unavailable data, and disconnuity in the indicators producon; such factors may contribute to the low adherence to

quantave evaluave studies. Therefore, evaluaons in the country would be between the second wave proposed by Vedung

(2010), with more qualitave assessments of local character and specic policies analysis, and the third wave, focused mainly

on accountability, performance measurement, and search for quality in the services provided.

At any rate, it should be emphasized that there is a strengthening of the evaluaon study to seek best pracces and theories,

contribung in a substanal way to the creaon of an evaluave “culture” capable of embracing the complexity and specicies

of each policy or program in queson (CARVALHO, 1999; UNDP, 2016).

The evoluonary trajectory of evaluave processes in Brazil and in the world facilitates understanding that there is no single

method or standard dened at the present me. There is a mulplicity of approaches and methodologies covering a wide

range of opons. Based on the assumpon that evaluaons are not the same, Cohen and Franco (2008), and Ramos and

Schabbach (2012) suggest the descripon of the dierent forms of evaluaon according to a series of criteria, namely use, me,

objecves, who performs it, to whom it is intended for, what is the expected outcome, among others. Costa and Castanhar

(2003) call the variety of concepts and methodologies of evaluaon studies a conceptual entanglement. The authors indicate

that the knowledge of several theorecal alternaves contributes greatly to the choice of the most appropriate method for

each type of policy or program to be evaluated.

According to Faria (2005), it is possible to indicate at least four types of use for the evaluaon: instrumental; conceptual;

persuasive; or claricaon. The instrumental use refers to the importance of quality and the adequate propagaon of the

results achieved, in order to turn the evaluaon somewhat tangible, and feasible of employability. Weiss (1998) adds that

the instrumental use of evaluaon might guide decision-makers as it enables a return to the history of the program analyzed,

provides feedback to evaluaon praconers, and also highlights the objecves established for the program.

The second use, called conceptual, is oen applied to those that do not have direct contact with the program formulaon

(local technicians); It is, therefore, necessary to provide informaon about the policy or program, to present its nature and

operaon, and to introduce them to the impacts and results achieved (FARIA, 2005). We may state that the main objecve

of the conceptual use is the learning provided to the actors; in this regard, Mokate (2002, p. 127, our translaon) emphasizes

that “summing up, evaluaon allows us to enrich management processes with dynamic learning. Far from being a devilish

monster, then, the assessment may have a new image, that of a guardian ally”. Complementarily, Ramos and Schabbach (2012)

indicate that learning can be enhanced when technicians acvely parcipate in the evaluaon process.

Addionally, the third use, called persuasive, described by Faria (2005, p. 103), “occurs when it is used to mobilize the support

towards the posion that decision-makers already have about the necessary changes in the policy or program”. The evaluaon,

at that moment, has the funcon of legimizing the desired changes and winning new supporters for this movement. Finally,

the use of claricaon is proposed as a result of the accumulaon of knowledge originated from the several already performed

evaluaons (FARIA, 2005) and becomes capable of guiding the governmental agenda. Mokate (2002) states that the maturaon

of a new management paradigm, focused on evaluave pracces, may be an ally in incorporang evaluaon as a natural and

gradual process for the achievement of the objecves proposed.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

329-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

In order to provide a foundaon for the dierenaon between the various moments of the evaluaon, Cohen and Franco

(2008) divide it into ex ante evaluaon and ex post evaluaon.

Ex-ante evaluaons are those performed prior to the decision-making process and may be said to serve as an input to decision-

making on the implementaon of social policies or programs (COTTA, 2001; COHEN and FRANCO, 2008). Furthermore, Ramos

and Schabbach (2012) arm that, in this type of evaluaon, a diagnosis is generated on the situaon observed, contribung

with the adequacy of the available resources to the proposed objecves (viability vericaon), also being able to serve as a

direcon tool for the maintenance and/or formulaon of policies or programs.

The ex post classicaon indicates that the evaluaons are performed during the execuon of a project or at the end of the

project. When evaluang refers to the intermediate moment (process evaluaon), the conclusions may found decisions of

connuity or disconnuity of a certain policy or program (COTTA, 2001; COHEN and FRANCO, 2008; TREVISAN and BELLEN,

2008; RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012). With regard to terminal evaluaons (which measure impact and outcome, for example),

ex-post evaluaons provide informaon concerning the experience gained and can support future decisions on the same

policy or program or contribute to the construcon of an evaluaon model to another objecve or similar experiences (COTTA,

2001; COHEN and FRANCO, 2008; TREVISAN and BELLEN, 2008; RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012). Based on the literature, we

may infer that ex post evaluaons are more widespread both in academic and praccal applicaons; thus, they present beer

established and more sophiscated methodologies.

Similarly, Scriven (1991) denes two terms for the evaluaon moments: formave evaluaon and summave evaluaon.

The formave evaluaon resembles the funcon of the ex post intermediate evaluaon, being conducted during the process

of implementaon or development of the program, and has as purpose providing an analycal reading to the decision makers.

The summave evaluaon is directed aer the compleon of the program (terminal ex post), providing administrators and

users with a judgment of the overall value of the program (SCRIVEN, 1991; TREVISAN and BELLEN, 2008). From the same

point of view, Ramos and Schabbach argue that the evaluaon rangs made by Scriven (1991) also present connecons

with the nature of evaluaon, whether it is program formaon (formave assessments) or analysis and producon of

informaon (summave assessment). Weiss (1998) argues that the simplicity proposed in Scriven’s denion (1991)

does not diminish the reach of the evaluave purposes, but produces informaon that contributes to the modicaon or

maintenance of the program.

Regarding the classicaon of the evaluaon from the point of view of who executes it or parcipates in it, it can be stated

that there is a consensus in the literature regarding the disncon in four types: external evaluaon; internal evaluaon;

mixed evaluaon; and parcipatory evaluaon. Firstly, Cohen and Franco (2008) warn that evaluaons performed by people

outside the organizaon tend to emphasize the method applied to the detriment of specic knowledge of the area in which

the policy or program is developed. Coa (1998) contributes with the discussion informing that external evaluaons add an

exempon to the evaluave pracce, however, the external evaluator has greater dicules of accessing the data. In addion,

we can cite as an advantage the greater objecvity of the external evaluators, because they do not parcipate in the internal

processes, besides the possibility of comparison with similar programs (COHEN and FRANCO, 2008; RAMOS and SCHABBACH,

2012). In the view of Thoenig (2000), in his arcle on public sector reform, external evaluaons may play a crucial role in

decision making; the author cites the case of Greece, which performed external evaluaons for decision-making in relaon

to the structural funds of the European Union.

With regard to internal evaluaons, the advantages presented by the literature are the reducon of the conicts generated by

the inseron of external people or organizaons; the possibility of review and learning regarding the processes executed in a

given policy or program; the greater theorecal and technical knowledge of the specic features evaluated. However, internal

evaluaons risk losing objecvity and paral conclusions, since they are developed by those involved in the formulaon and

implementaon of the analyzed program (WEISS 1998; COTTA 1998; COHEN and FRANCO 2008; VEDUNG 2009; RAMOS and

SCHABBACH, 2012).

Then, we have the mixed evaluaon, which combines the two models described. Basically, the goal of mixed assessment

is to add eorts and ensure synergy between the actors involved in the acon. The potenalies of each model are then

combined and the impacts or biases which are presented individually are reduced (COHEN and FRANCO, 2008; RAMOS and

SCHABBACH, 2012).

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

330-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

Finally, there exists the parcipatory evaluaon, which has as a main objecve reducing the distance between the organizers

and producers of the evaluaon and the beneciaries of the evaluated policies or programs. It allows the parcipaon of users

in all phases of the polical cycle, favoring opinion, and meeng the specic demands of these actors (COHEN and FRANCO,

2008, RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012). For Paon (1999), parcipatory evaluaon should consider priories and eects and

establish common denions for both evaluators and beneciaries.

The author describes some steps to make parcipatory evaluaon feasible, such as conducng interacve sessions to discuss

aspects of the evaluaon; discussion and mode of use of priories, purposes, and denions; and proposal of an ideal evaluaon

model that sases all the condions exposed in the previous stages (PATTON, 1999). Addionally, Spink (2001) exposes the

importance of parcipatory evaluaon, already highlighted, capable of strengthening the es between the involved ones,

helping to maintain the democrac evaluaon pracce. However, one should take into account the dimension of the policy

or program evaluated; in this regard, Ramos and Schabbach (2012) suggest that parcipatory evaluaons work adequately

only on small projects or local programs. In turn, Carvalho (1999, p. 89) argues that:

In fact, in dealing with more circumscribed units (an instuon or a program), parcipatory evaluaon

becomes a rich procedure, since its accomplishment is shared with the agents and beneciaries involved

(in the program or instuon), allowing a reecve and socialized appropriaon among the various

subjects of moving acon in addion to the evaluaon.

We should emphasize, therefore, that parcipatory evaluaon promotes the incorporaon of individuals into decision-making

and favors social learning, and cizenship (CARVALHO, 1999). Ceneviva and Farah (2012) emphasize that bureaucrats should

not work in isolaon, on the contrary, evaluaon is a tool for transparency of public acts and cizens can and should inform

themselves and supervise the acons promoted by polical actors.

Regarding the approach, the evaluaons can be classied in qualitave, quantave, and mixed methods. In short, Weiss

(1998) classies qualitave research as those that present themselves in words and quantave ones, in numbers. The author

complements by stang that quantave assessments collect data and transform it into numerical informaon, strongly

supported by stascs, mathemacal, and econometric methods. Quantave approaches can use sophiscated tools in

data analysis, which idenfy relaonships between one or more variables, and can encompass a large sample universe, as

well as provide informaon on the extent and distribuon of a phenomenon (WEISS, 1998). On the other hand, qualitave

evaluaons tend to use less structured tools, such as interviews, observaonal techniques and document analysis (WEISS,

1998). Garcia (2001, p. 29) argues that:

The evaluaon has to be operated with a broad vision, guided by a judgment of value, something

eminently qualitave, focused on complex processes, in which the elements in interacon do not always

produce measurable manifestaons, and some of these elements may not present quanable aributes.

Rossi and Wright (1984) argue that, for social research, as in the case of public policies study, the qualitave approach displays

advantages because it has the capacity to promote approximaon with reality and is exible to contemplate the complexity

entailed in such policies. Mokate (2002) alludes to the great discussions in the social sectors that place qualitave and

quantave approaches on dierent sides of the same arena. It is an exaggerated compeon about which method is most

ecient, eectual or eecve. These dierences are aributed to the reasons for which, in part, evaluaons are not rounely

instuonalized as a roune of the administrave pracce.

In terms of results, a large part of the naonal and internaonal literature discusses the advantages and disadvantages

of each approach, however, there is growing acceptance that the integraon between them is the best soluon to the

theorecal confrontaons (SILVEIRA, VIEIRA, CAPOBIANGO et al., 2013). The dierences between the approaches generate

opportunies for complementaon, adding the similaries and increasing the synergy between the pares (MOKATE, 2002).

It is in this area that the mixed methods approach is inserted, which are nothing more than the combinaon of qualitave

and quantave assessments. Mokate (2002, p. 114, our translaon) argues that “parcularly, the evaluaon may also be

applied to quantave and qualitave methods to generate dierent types of informaon which together correspond to the

dierent quesons proposed by the evaluaon process.”

Scriven (1996) establishes the skills of an evaluator and notes the use of mixed methods, arguing that the evaluator should

present basic qualitave domains such as quesonnaire use and observaonal methods. The control of polarizaon between

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

331-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

approaches is also necessary to combine such praccal tests, measurement procedures, judgment and narrave evaluaon,

and case study techniques. Therefore, Bloch, Soresen, Graversen et al. (2014) argue that the use of mixed methods contributes

to the use of the best available data sources, with the aim of providing comprehensive and robust answers. However, the

authors present the me taken, the resources, and the commitment to build the pragmac aspects of the evaluaon as

limitaons to the use of mixed methods, (BLOCH, SORENSEN, GRAVERSEN et al., 2014). Costa, Pegado, Ávila et al. (2013) add

that quantave research leads to a generalizaon of results generated by standardized informaon. On the other hand,

qualitave research will probably provide data on social circumstances and environments, giving emphasis to the cultural

and contextual dimensions.

Considering the methodology applied to the evaluaon, Costa and Castanhar (2003) group the evaluaons in process evaluaon;

goals evaluaon; and impact assessment. As for the process evaluaon, according to Costa and Castanhar (2003, p. 980):

Its objecve is to detect possible defects in the elaboraon of procedures, to idenfy barriers, and

obstacles to its implementaon and to generate important data for its reprogramming, through the

registraon of events and acvies. Thus, the proper use of the informaon produced during the

development of the program allows introducing changes in its content during its execuon.

With purposes similar to those of the formave evaluaon described by Scriven (1991), the process evaluaon systemacally

assesses the evoluon of policies or programs, as well as follows its internal processes. Its uses allow to contemplate the content

of the program, the relaonship between what was planned and what has been executed, the reach of the target users, and

the success or failure in the correct delivery of the benets (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003; RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012).

Furthermore, we have the goals evaluaon, described by Costa and Castanhar (2003) as the most tradional evaluaon

methodologies. It aims to “measure the degree of success that a program achieves in relaon to the achievement of previously

established goals” (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003, p. 997). We may consider this type of evaluaon as an ex post evaluaon

since it requires the program to be completed to be evaluated (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003). Ramos and Schabbach (2012)

present a dierent conceptualizaon, called results evaluaon, but with objecves similar to the goals evaluaon; In this

context, the eects and consequences of a given policy are measured, determining its success or failure based on eecve

changes in the populaons beneted.

The evaluaon, once considered as a way of measuring the performance of policies or programs, being such performance the

achievement of goals (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003) or the results evaluaon (RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012), needs criteria

to structure and, nally, to measure the contracted consequence (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003). In this manner, three basic

dimensions prevail to measure the results obtained (DRAIBE, 2001; COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003; ALVES and PASSADOR, 2011):

• of economic origin, signies to achieve the objecves of the program, by priorizing established

standards, with the lowest possible cost-benet rao;

• measures the degree to which goals and objecves have been achieved, thus translang in a simplied

way the result achieved;

• also treated in the literature as a measure of impact, indicates the posive eects related to the program

target public. It is a broader dimension, because it analyzes the economic, socio-cultural, environmental, and

instuonal aspects, that is, eecvity measures both the quanty and the quality of the goals reached by the

program.

In the chain of ideas, Costa and Castanhar (2003), and Ramos and Schabbach (2012) agree on the last denion proposed: the

impact assessment. It is therefore inferred that impact assessment covers not only the results achieved in terms of eciency,

eecvity, and ecacy, but also changes in the target populaon as a result of the implementaon of the evaluated policy

or program. Coa (1998, p. 113) adds that:

The dierence between the results evaluaon and impact assessment, therefore, depends eminently

on the scope of the analysis: if the objecve is to inquire about the eects of an intervenon on

the public served, then it is a results evaluaon; if the intenon is to capture the reexes of this

same intervenon in a broader context, then it is an impact assessment. Or, put another way, the

results evaluaon is aimed at measuring the intermediate results of the intervenon, and the impact

assessment, its nal results.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

332-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

We may compare the impact assessment to the summave evaluaon proposed by Scriven (1991), which is executed ex

post to the realizaon of the program or project. In summary, this evaluave model uses methodological structures that

provide cause and eect relaonships between the acons performed by the program and the eects promoted in the target

community (COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003; RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012). In order to do so, it is necessary to follow two

guidelines noted by Coa (1998): a) the objecves must be dened to include the idencaon of measurable goals; and b)

the implementaon of the policy or program must be at least sasfactory to support an impact assessment without bias or

even to make it unfeasible.

It is also worth menoning the importance of the research designs and outcomes for each type of evaluaon: of a process,

goals/results or impacts, depending on the problem that it responds to. In view of this need, Box 2 describes, without the

pretension of exhausng them, each of the designs and outcomes presented in the literature (SCRIVEN, 1991; WEISS, 1998;

COTTA, 1998; OECD, 2002; COSTA and CASTANHAR, 2003; VEDUNG, 2009; CAMELO JUNIOR, FERNANDES, JORGE et al., 2011;

RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012; SILVEIRA, VIEIRA, CAPOBIANGO et al., 2013)

Design/outcome Brief descripon Evaluaon type

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

333-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

In conclusion, in view of the variety and complexity of the applicaons, methods, tools, approaches, moments and actors

involved in the evaluaon process, the next secon explores internaonal trends about the evoluon of evaluaon studies,

with the aim of comparing them under the point of view of types, methodologies, and outcomes.

RECENT NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL TENDENCIES

In the face of ever more complex and turbulent scenarios, global trends are converging towards structuring and strengthening

internaonal evaluaon acons, supported by government agencies, independent agencies, mullateral organizaons, and

civil society organizaons. It is clear that the pares agree that evaluave acvies are important for good governance and

can contribute to the advancement of more eecve, ecacious, and ecient social public policies (RAMOS and SCHABBACH,

2012; EVALPARTNERS, 2015). In order to achieve it, this topic maps, without the pretension of exhausng them, the acons

developed and presents acons executed by internaonal organizaons.

Internaonal organizaons such as the World Bank, UN and OECD parcipate and play a key role in building and strengthening

instuonalized evaluave pracces. The aim is to develop methodological frameworks and tools to improve the design,

execuon, and evaluaon of programs or projects around the world (RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012).

In this context, 2015 was established by EvalPartners and approved by the UN as the internaonal year of evaluaon. The

organizaon, built through partnerships between the Internaonal Organizaon for Evaluaon Cooperaon (IOCE) and the

United Naons Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in partnership with several major organizaons, aims to create a network of global

evaluators who can contribute to the evaluaon of public policies in their countries (EVALPARTNERS, 2016). According to

the guidelines of the organizaon, the iniave aims at contribung to the improvement of the capacies of civil society

organizaons (CSOs), as well as at involving them strategically and expressively in the naonal evaluaon processes, with the

aim of developing systems of evaluaon and ensure equity in acons (EVALPARTNERS, 2016). To this end, they developed

the Global Assessment Agenda (or EvalAgenda2020). The document, approved by the delegates of the Global Assessment

Forum, held in Nepal in 2015, provides a guide for future assessment, and for the strengthening of evaluators from dierent

countries and organizaons (EVALPARTNERS, 2016).

The European Union has also developed a project to evaluate the structural policies of the bloc, as well as the idencaon

and use of innovave pracces for evaluaon methodologies, as well as mulsectoral involvement with the objecve of

reducing poverty (SOPHIE PROJECT, 2015).

In the context of Lan America, the Lan American and Caribbean Network of Monitoring, Evaluaon and Systemazaon

(ReLAC), in cooperaon with the Foment to the Evaluaon Capacies Project (Foceval Project) of the Ministry of Planning

and Economic Policy of Costa Rica (Mideplan), and the German Instute for Development Cooperaon Assessment (DEVAL)

conducted a series of public consultaons with experts and evaluaon professionals during the years 2014 and 2015 and

presented the rst dras at the IV ReLAC Conference in 2015. Recently, in August 2016, they released a document summarizing

this proposal entled Guidelines for Evaluaon for Lan America and the Caribbean, with objecve of enriching the common

guideline for the theorecal and praccal formaon of evaluators in the region, and insgang the culture of evaluaon in

the connent (BILELLA, VALENCIA, ALVAREZ et al., 2016).

We may conrm the performance of the Evaluaon and Results Learning Center for Brazil and Lusophone Africa (FGV EESP-

Clear), based at the Getulio Vargas Foundaon (FGV) in São Paulo, which benets from the muldisciplinary environment

of the FGV, which is one of the six regional centers that make up the Clear iniave - which involves several countries and

aims to improve policies and programs with development of capacies, and monitoring and evaluaon systems. Among the

axes of monitoring and evaluaon research, the following project: a) training; b) technical assistance; c) generaon of new

evidence; and d) diusion of evidence and knowledge (FGV CLEAR, 2018).

Sll in Brazil, another iniave is gaining notoriety among the scienc community: The Center for Data Integraon and

Knowledge for Health (Cidacs), created in 2016 and linked to the Oswaldo Cruz Foundaon of Bahia (Fiocruz Bahia), which

promotes research and interdisciplinary projects with processing, integraon, and analysis of large data. The aim is to contribute

to the use of innovave methodologies, to provide professional and scienc training, and to support decision-makers in

relaon to public social policies, especially health determinants, and environmental condions (CIDACS, 2018).

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

334-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

It is also worth nong that there is a global eort aimed at building an agenda based on integraon among all internaonal

organizaons, guided mainly by the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Naons

Development Program (UNDP, 2016). The rst ve years envisaged by EvalAgenda2020 have as priority the creaon and

strengthening of mechanisms for the evaluaon of SDGs. Box 3 summarizes the main acons (UNDP, 2016; UNO, 2016;

EVALPARTNERS, 2015; OECD, 2016; SOPHIE PROJECT, 2012; BILELLA, VALENCIA, ALVAREZ et al., 2016; CLEAR, 2018; CIDACS,

2018; IBGE, 2018).

Organizaon Acon developted Brief descripon

per capita

Bolsa Família

Minha Casa Minha Vida

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

335-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

It is clear to understand that evaluave acvies are important for good governance and can contribute to the advancement

of more eecve, ecacious, and eecve public policies (RAMOS and SCHABBACH, 2012; EVALPARTNERS, 2015). We should

emphasize that, as can be deduced from the academic and governmental research organizaons, it is important to strengthen

the study of evaluaon in order to seek best pracces and theories, greatly contribung to the creaon of an evaluave

“culture” capable of encompassing the complexity and the specicies of each policy or program in queson (CARVALHO,

1999; UNDP, 2016).

Based on the theorecal framework built and the assessments made by mullateral organizaons, the main theorecal gaps

observed are: a) studies involving mulple countries; b) use of the mixed methods approach; c) evaluave studies combining two

or more public policies; d) strengthening, training, and structuring of evaluaon pracces in developed and developing countries;

e) use of the results of evaluaons to inform and improve public policies; and f) parcipatory evaluaons - contemplaon of

all the actors involved (administrators, decision makers, formulators, implementers, executors, and beneciaries).

In view of the eorts presented, the importance of robust, unbiased, and mul-method approaches is evident. According

to the above, it is observed that developed countries have already incorporated in their polical agenda the evaluaon as a

process, dierent from what occurs in Brazil and in other developing countries, where the evaluaon of public policies and

programs sll suers from disconnuity and unavailability of reliable and complete data, as well as integrated informaon

systems that facilitate access to informaon, which would contribute greatly to decision making.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In consonance with the search for arculated models for the development of governmental strategies to combat poverty

and promote cizenship in Brazil, several internaonal organizaons have been developing integrave and intersectoral

proposals aimed at improving the quality of life of the world’s populaon. Acons such as the establishment of UNDP SDGs

and comparave and shared studies among countries belonging to the OECD are examples of such eorts.

In Lan America, there is a growing search for evaluave acons to strengthen and improve the public policies adopted in

the region, mainly related to addressing social vulnerabilies. Nevertheless, the scenario demands the development of the

professional capacies of the governments and increase the performance of civil society in monitoring and control. The evoluon

and internalizaon of evaluaon processes contribute to the development of robust and comprehensive methodologies. From

the 1980 decade, there is a growing search for models capable of combining quantave and qualitave informaon (mixed

methods), aiming at improving and making the evaluaon more realisc regarding the complexity of the analyzed policies.

The search for new robust and comprehensive evaluaon methodologies is essenal for the development and evoluon of

evaluaon acvies, providing administrators with concrete, real, and applicable data. Therefore, the aim is to use innovave

methodologies, providing professional and scienc training, and supporng decision-makers in relaon to public social

policies, especially health-related ones.

However, it is worth menoning that, in the Brazilian case, the available public databases present problems of reliability,

unavailable data and disconnuity in the producon of indicators; such factors may contribute to the low adherence to

quantave evaluave studies. Thus, evaluaons in Brazil would have more qualitave evaluaons of local character and

analysis of specic policies, mainly focused on accountability and performance measurement and in search of the quality of

services provided. There are also experiments that promote interdisciplinary research and projects based on the processing,

integraon, and analysis of large data quanes (big data).

Fortunately, we should note that the data demonstrate the strengthening of the study of evaluaon in Brazil, in order to

seek best pracces and theories, enormously contribung to the creaon of an evaluaon “culture” capable of embracing

the complexity and specicies of each policy or program in queson. However, it is also necessary to emphasize the

importance of connuous evaluaon acons, especially in scenarios with scarce nancial, human, and material resources.

Such evaluaons may contribute to the adequate allocaon of resources and the strengthening of control acons by the

responsible agencies.

336-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

REFERENCES

ALA-HARJA, M.; HELGASON, S. Em direção às melhores práticas

de avaliação. , v. 51, n. 4, p. 5-60, 2000.

ALVES, T.; PASSADOR, C. S. : condições

de oferta, nível socioeconômico dos alunos e avaliação. São Paulo:

Annablume, 2011.

ARRETCHE, M. T. S. Tendências no estudo sobre avaliação. In: RICO,

E. M. (Org.). : uma questão de debate.

São Paulo: Cortez, 2001.

BILELLA, P. D. R. et al.

.Buenos Aires: Akian, 2016.

BLOCH, C. et al. Developing a methodology to assess the impact of

research grant funding: A mixed methods approach.

, v. 43, p. 105-117, 2014.

BOBBIO, N.; MATTEUCCI, N.; PASQUINO, G. .

1. ed. Brasília: Editora da UnB, 1998.

CAMELO JUNIOR, J. S. et al. Avaliação econômica em saúde: triagem

neonatal da galactosemia. , v. 27, n. 4,

p. 666-676, 2011.

CARVALHO, M. C. B. Avaliação parcipava: uma escolha metodológica.

In: RICO, E. M. (Org.). : uma questão

de debate. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1999. p. 87-94.

CENEVIVA, R.; FARAH, M. F. S. Avaliação, informação e responsabilização

no setor público. , Rio de Janeiro,

v. 46, n. 4, p. 993-1016, 2012.

CENTRO DE INTEGRAÇÃO DE DADOS E CONHECIMENTOS PARA

SAÚDE – CIDACS. . 2018. Available at: <hps://cidacs.

bahia.ocruz.br/sobre/quem-somos/>. Accessed on: July 18, 2018.

COHEN, E.; FRANCO, R. . 8. ed. Rio de

Janeiro: Vozes, 2008.

COSTA, A. F. et al. Mixed-methods evaluaon in complex programmes:

the national reading plan in Portugal.

, v. 39, p. 1-9, 2013.

COSTA, F. L.; CASTANHAR, J. C. Avaliação de programas públicos:

desaos conceituais e metodológicos.

, Rio de Janeiro, v. 37, n. 5, p. 969-992, 2003.

COTTA, T. C. Metodologias de avaliação de programas e projetos

sociais: análise de resultados e de impacto.

, v. 49, n. 2, p. 103-124, 1998.

COTTA, T. C. Avaliação educacional e polícas públicas: a experiência

do Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Básica (Saeb).

, v. 52, n. 4, p. 89-111, 2001.

CRUMPTON, C. D. et al. Avaliação de polícas públicas no Brasil e nos

Estados Unidos: análise da pesquisa nos úlmos 10 anos.

, Rio de Janeiro, v. 50, n. 6, p. 981-1001, 2016.

CRUZ, M. M. Avaliação de polícas e programas de saúde: contribuições

para o debate. In: MATTOS, R. A.; BAPTISTA, T. W. F. (Org.).

. Porto Alegre: Rede Unida, 2015.

p. 285-317.

DERLIEN, H.U. Una comparación internacional en la evaluación de las

polícas públicas. , v. 52, n. 1, p. 105-124, 2001.

DRAIBE, S. M. Avaliação de implementação: esboço de uma metodologia

de trabalho em polícas públicas. In: BARREIRA, M. C. R. N.; CARVALHO,

M. C. B. (Org.).

. São Paulo: IEE/PUC-SP, 2001. p. 13-42.

EVALPARTNERS. . 2015. Available

at: <hp://www.evalpartners.org/sites/default/les/documents/

EvalAgenda2020.pdf>. Accessed on: July 15, 2016.

EVALPARTNERS. . [2016]. Available at:

<hp://www.evalpartners.org/global-evaluaon-agenda>. Accessed

on: July 27, 2016.

FARIA, C. A. P. A políca da avaliação de polícas públicas.

, v. 20, n. 59, p. 97-109, 2005.

FGV CLEAR.

. 2018. Available at:

<hp://fgvclear.org/pt/sobre-o-fgv-clear/>. Accessed on: July 17, 2018.

FREY, K. Polícas públicas: um debate conceitual e reexões referentes

à práca da análise de polícas públicas no Brasil.

, n. 21, [n.p.], 2000.

GARCIA, R. C. Subsídios para organizar avaliações da ação

governamental. , n. 23, p. 7-70, 2001.

HOWLETT, M.; RAMESH, M.; PERL, A.

: uma abordagem integradora. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier,

2013.

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA – IBGE.

. 2018a. Available at: <hps://ods.ibge.gov.br/>.

Accessed on: Apr. 25, 2018.

MOKATE, K. M. Convirendo el “monstruo” en aliado: la evaluación

como herramienta de la gerencia social. ,

v. 53, n. 1, p. 89-134, 2002.

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT

– OECD.

. Paris: OECD, 2002.

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS – ONU.

. 2015.

Available at: <hps://nacoesunidas.org/pos2015/agenda2030/>.

Accessed on: July 27, 2016.

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS – ONU.

: Eval2016-2020. [s.l]: EvalPartners, 2016.

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT

– OECD. : a pilot assessment

of where OECD countries stand. [2016]. Available at: <hp://www.

oecd.org/std/oecd-measuring-distance-to-the%20sdgs-target-pilot-

study-web.pdf>. Accessed on: July 27, 2016.

PATTON, M. Q. . 1999. Available

at: <hp://gametlibrary.worldbank.org/FILES/284_Ulisaon%20

Focused%20evaluaon%20in%20Africa.pdf>. Accessed on: July 25,

2016.

PAULA, A. P. P. : limites e potencialidades

da experiência contemporânea. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 2005.

337-337

Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 17, nº 2, Rio de Janeiro, Apr./Jun. 2019.

eoretical essay on public policy evaluations

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador

PICCIOTTO, R. Democrac evaluaon for the 21

st

century. ,

v. 21, n. 2, p. 150-166, 2015.

PROGRAMA DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA O DESENVOLVIMENTO –

PNUD.. [2016]. Available

at: <hp://www.pnud.org.br/ods.aspx>. Accessed on: July 27, 2016.

RAMOS, M. P.; SCHABBACH, L. M. O estado da arte da avaliação

de políticas públicas: conceituação e exemplos de avaliação no

Brasil. , Rio de Janeiro, v. 46, n. 5,

p. 1271-1294, 2012.

ROSSI, P. H.; WRIGHT, J. D. Evaluaon research: an assessment.

, v. 10, p. 331-352, 1984.

SCRIVEN, M. . 4. ed. Newbury Park: Sage, 1991.

SCRIVEN, M. Types of evaluaon and types of evaluator.

, v. 17, n. 2, p. 151-162, 1996.

SECCHI, L. : conceitos, esquemas de análise, casos

prácos. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cengage Learning, 2014.

SILVEIRA, S. F. R. et al. Polícas públicas: monitorar e avaliar para quê?

In: FERREIRA, M. A. M.; ABRANTES, L. A. (Org.).

.Viçosa: Triunfal, 2013. p. 301-327.

SOPHIE PROJECT. . [2015]. Available at: <hp://www.

sophie-project.eu/pdf/conclusions.pdf>. Accessed on: Aug. 08, 2016.

SOPHIE PROJECT.

. [2012]. Available at: <hp://www.sophie-project.

eu/project.htm>. Accessed on: Sept. 13, 2016.

SOUZA, C. Polícas públicas: uma revisão da literatura. ,

v. 8, n. 16, p. 20-45, 2006.

SPINK, P. Avaliação democráca: propostas e práca.

, n. 3, p. 7-25, 2001.

THOENIG, J. C. A avaliação como conhecimento ulizável para reformas

de gestão pública. , v. 51, n. 2, p. 54-71, 2000.

TREVISAN, A. P.; BELLEN, H. M. V. Avaliação de polícas públicas: uma

revisão teórica de um campo em construção.

, Rio de Janeiro, v. 42, n. 3, p. 529-550, 2008.

VEDUNG, E. . New Brunswick:

Transacon, 2009.

VEDUNG, E. Four waves of evaluaon diusion. , v. 16,

n. 3, p. 263-277, 2010.

WEISS, C. H. Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluaon?

, v. 19, n. 1, p. 21-33, 1998.

WEISS, C. H. The interface between evaluaon and public policy.

, v. 5, n. 4, p. 468-486, 1999.

Lilian Ribeiro de Oliveira

Claudia Souza Passador