HOW TO INCREASE CITATIONS TO LEGAL

SCHOLARSHIP

ROB WILLEY

*

& MELANIE KNAPP

*

Abstract

Using nearly 250,000 law review articles published on HeinOnline over

a five-year period, the authors analyze citation patterns and their

relation to characteristics of the articles such as title length, number of

authors, article length, publication format, and more. The authors also

describe past citation studies and best practices in Search Engine

Optimization (SEO). The authors find that factors beyond article quality

likely impact scholarly citations. Drawing from the lessons in the

citation patterns, article characteristics, and SEO best practices, the

authors offer techniques to increase the article citation counts of

articles published in U.S. law journals. Using lessons from the SEO

world, the authors conclude with a detailed discussion of potential

problems with citation ranking schemes, such as citation cartels,

keyword stuffing, and perverse incentives for authors to avoid writing

on obscure but important legal topics.

*

[email protected], Faculty and Web Services Librarian, George Mason University Law

Library.

*

[email protected], Associate Director, George Mason University Law Library.

The Ohio State Technology Law Journal

158

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION...................................................................... 160

OUR INTEREST IN CITATIONS ................................................... 161

LEVERAGING GOOGLE’S EXPERTISE FOR SCHOLARS .................. 162

“BLACK HAT” SEO & MANIPULATION OF U.S. NEWS’S SCHOLARLY

IMPACT ................................................................................... 164

TL;DR ........................................................................................ 166

METHODOLOGY ..................................................................... 168

CITATION BREAKDOWN ........................................................ 171

CHARACTERISTICS OF WELL-CITED ARTICLES ................ 173

CHARACTERISTIC ONE: LONG ARTICLES ................................... 174

SEARCH ENGINES AND SEO EXPERTS PREFER LONGER

CONTENT ............................................................................ 176

WHY LONGER CONTENT GETS MORE CITATIONS .................. 179

SUGGESTIONS TO LENGTHEN ARTICLES ............................... 184

EXAMPLE ARTICLES ............................................................ 187

ARE LONGER ARTICLES REALLY BETTER? ........................... 188

CHARACTERISTIC TWO: SHORT TITLES WITHOUT COLONS ........ 188

TITLE LENGTH ................................................................... 188

TITLE COLONS .................................................................... 189

ADDITIONAL ACADEMIC STUDIES .........................................190

SEARCH ENGINES AND SEO EXPERTS ALSO FAVOR SHORTER

TITLES ................................................................................ 193

NO SEO STUDIES ON USE OF COLONS .................................. 198

WHY ARE SHORTER TITLES WITHOUT COLONS PREFERRED?

.......................................................................................... 198

EXAMPLE TITLES ................................................................ 199

CHARACTERISTIC THREE: WRITE ON A POPULAR TOPIC ........... 200

SEO AND TOPIC SELECTION ............................................... 202

INCORPORATING POPULAR TOPICS ...................................... 203

FINDING POPULAR TOPICS ................................................. 204

COMPETITOR ANALYSIS ...................................................... 208

ADDITIONAL ITEMS TO CONSIDER.................................... 209

PUBLISH IN A WIDELY ACCESSIBLE JOURNAL .......................... 209

PUBLISH IN A TOP JOURNAL .................................................... 212

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

159

CITE YOURSELF? ..................................................................... 213

PUBLISH WITH A WELL-CITED AUTHOR ................................... 215

PUBLISH WITH A CO-AUTHOR? ................................................ 215

CHECK HEIN RECORDS AND ENSURE CREDIT FOR YOUR WORK

WITH ORCID ............................................................................ 216

MORE SEO PRACTICES TO CONSIDER....................................... 217

LESSONS FROM SEO FOR U.S. NEWS’S SCHOLARLY

IMPACT RANKING .................................................................. 221

FACTORS BEYOND QUALITY MAY IMPACT CITATIONS ............... 224

INCREASED PRESSURE LEADS TO STRONGER MOTIVES FOR ABUSE

...............................................................................................225

CITATION CARTELS ................................................................. 226

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TOP JOURNALS TO FAVOR THEIR SCHOLARS

.............................................................................................. 228

KEYWORD STUFFING .............................................................. 229

SEO EXPERTS & LAW SCHOOLS .............................................. 229

DECREASE IN IMPORTANT BUT LESS POPULAR TOPICS ............. 230

DO CITATIONS FOLLOW THE SCHOLAR? .................................. 232

PUBLISHING THE SAME CONTENT IN MULTIPLE PLACES .......... 232

LACK OF COVERAGE OF NON-LEGAL SOURCES ......................... 233

ISSUES WITH OCR TEXT RECOGNITION ................................... 234

“NO FOLLOW”: AVOID CITATIONS COUNTING WHEN YOU DO NOT

SUPPORT THE SCHOLARSHIP .................................................... 235

CONCLUSION ......................................................................... 236

160

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

Introduction

Like many authors, we wrote this article because we want to share our

ideas, thoughts, and data. One way to verify that others are taking in

what we’ve shared is to monitor this article’s citation count. So, like

most scholars, we wrote this article to get cited.

In this article, we share characteristics that correlate to increased

citations in legal scholarship, with the goal of helping scholars get cited

more. We found these characteristics by looking at the differences

between articles that are well-cited and those that are not, searching for

characteristics that the data indicate will increase chances of citation.

Based on our findings, we created a set of guidelines to increase the

likelihood that an article will be cited. Our interest in this area grew out

of experience, working closely with faculty publications, and with

optimizing websites for Google’s search algorithm. That is why we use

SEO studies on Google’s algorithm as a source of comparison to many

of our findings.

When we began this study, we had theories on what would lead to

increased citation counts, primarily based on our personal preferences

and what we knew about Search Engine Optimization (SEO). In some

cases, the data aligned with our assumptions, but, in several instances,

the study’s results surprised us. They may surprise you too. Regardless,

we believe that if you are a scholar writing to get cited, you will benefit

from reading this article. At the very least, it will make you think

differently about how you write, structure, and publish your article. The

majority of the articles we reviewed have a legal focus, but many of the

findings align with similar studies in other fields.

1

1

See, e.g., Maarten van Wesel, Sally Wyatt & Jeroen ten Haaf, What a Difference a Colon

Makes: How Superficial Factors Influence Subsequent Citation, 98 SCIENTOMETRICS 1601

(2014) (finding, as we did, that longer articles tend to get more citations).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

161

Over the course of gathering data, one thing that stood out is how many

articles have no citations. The total set we considered included 242,924

articles. From that set, 199,865 articles (or roughly 82 percent) had zero

citations. Don’t let that be you! What you have to say matters. Put in the

time, whether by using the suggestions in this article or ideas of your

own, to make sure people read and consider your work.

Perhaps the potential for increased emphasis on citations that U.S.

News’ proposed law school faculty scholarly impact ranking would add

also helped put the idea for this study on our minds. If done well, this

new ranking system has the potential to improve U.S. News’ influential

law school ranking. However, the proposal has a wide range of pitfalls.

Using the experience of other disciplines and the SEO world, we

conclude this article by highlighting some of these pitfalls. Our hope is

that drawing attention to these issues will allow the relevant parties to

learn from the mistakes others have already made.

Our Interest in Citations

Our library is responsible for uploading faculty papers to SSRN.

2

We

also help faculty with various research projects as they author articles.

Through our experience, we’ve seen how much download and citation

counts matter to faculty. This makes sense, as they are a factor in tenure

decisions and generally viewed as a measure of a scholar’s influence.

3

Given our closeness to the process, the importance of citations had been

2

SSRN FAQ Page, SSRN, https://www.ssrn.com/index.cfm/en/ssrn-faq/

[https://perma.cc/M9FE-ACTK] (“SSRN is a platform for the dissemination of early-stage

research.”).

3

Erin C. McKlernan et al., Use of the Journal Impact Factor in Academic Review, Promotion,

and Tenure Evaluations, ELIFE, Jul. 31, 2019, at 1; Dag W. Aksnes, Liv Langfeldt & Paul

Wouters, Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic

Concepts and Theories, SAGE OPEN, Feb. 7, 2019, at 1.

162

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

in the back of our minds for years. With U.S. News’ proposed ranking

system, the focus on citations will only increase.

4

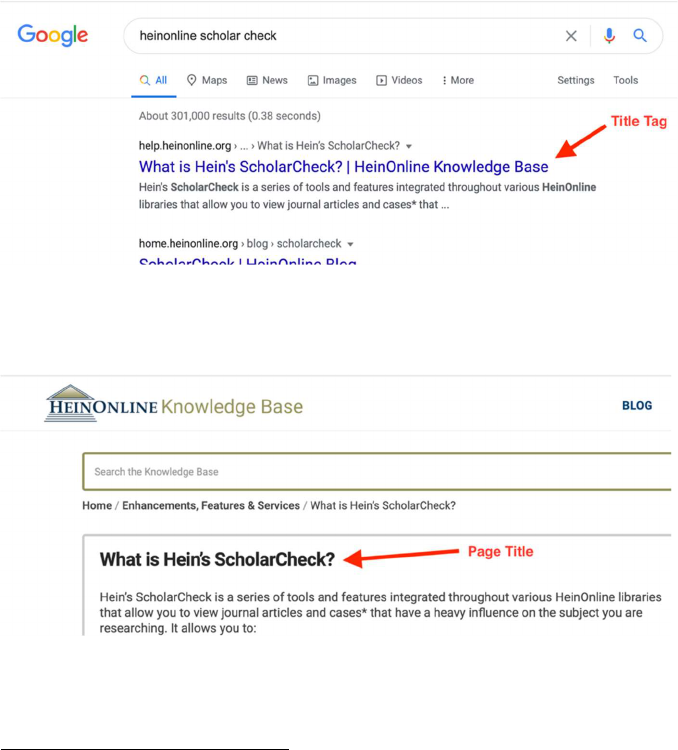

Leveraging Google’s Expertise for Scholars

We started our study by thinking about why some articles gain

widespread popularity, while others do not. Experience with Search

Engine Optimization,

5

an industry that has grown out of website

owners’ desire to rank well in search results, led us to wonder whether

some of the principles SEO experts have identified would apply to

scholarly articles.

6

Ranking well on Google has similarities to being

well-cited. Most obviously, Google’s ranking algorithm considers the

websites that link to (i.e., cite) the webpages it ranks.

7

Additionally,

Google’s algorithm looks at factors that indicate whether the content it

4

Robert Morse, U.S. News Considers Evaluating Law School Scholarly Impact, U.S. NEWS

(Feb. 13, 2019, 1:00 PM), https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/college-rankings-

blog/articles/2019-02-13/us-news-considers-evaluating-law-school-scholarly-impact

[https://web.archive.org/web/20200212212525/https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/coll

ege-rankings-blog/articles/2019-02-13/us-news-considers-evaluating-law-school-scholarly-

impact].

5

For interested readers, here’s a little more on SEO. Google regularly crawls the internet for

content. It then creates an index of that content and runs it through an algorithm. How the

algorithm values or rates the indexed content determines where each webpage displays in

search results. The earlier a webpage appears in results, the more likely a user will access it.

Although underlying motivations may differ, the goal of most website owners is to increase

quality traffic to their websites, which means they want to be as close as possible to the top

position in search results. Google does not reveal how its algorithm works. Since there is no

authoritative source for what will lead to a high website ranking, people have speculated,

conducted studies, and done extensive research on what websites can do to increase their

chances of ranking well. Generally, these efforts to rank well in search results are referred to

as Search Engine Optimization or SEO.

6

Cf. Mary Whisner, My Year of Citation Studies, Parts 1-4, 110 L. LIBR. J. 167, 167-80, 283-

94, 419-28, 561-77 (2018) (Once we started research, we found that others had similar ideas.

For example, Mary Whisner investigated what leads an article to be well-cited). If you are

interested in another perspective on this topic, we recommend also taking a look at Whisner’s

work.

7

See What is SEO?, MOZ, https://moz.com/learn/seo/what-is-seo [https://perma.cc/VWD6-

VLJ4] (chart under How SEO works heading indicating that SEO professionals view link

related items as making up roughly 40 percent of Google’s ranking algorithm).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

163

ranks provides the information people are seeking — similar to how a

citation indicates that the citing author found an article useful.

8

Here,

it’s important to remember that Google’s algorithm does not simply

look at the content itself — proper spelling, grammar, character count,

etcetera — Google also factors in indicators from actual users.

9

For

example, Google tracks how often users click an item when it appears

in their search results (the “click-through rate” in SEO jargon).

10

This

indicates how effective a page’s title and search snippet are. This data

signals people’s preference for one piece of content over another, and

Google uses this information to adjust its algorithm to better match its

users’ preferences. Scholarly articles also have titles, and the search

snippet has similarities to an article abstract. Given these and other

similarities, we thought there might be common ground between well-

cited articles and well-ranked websites.

Furthermore, there is a reason that Google’s search engine dominates

the search market.

11

Think about your own experience with Google

compared to a less popular search engine. In most instances, Google

provides superior results. Google gives users excellent results because

Google has spent countless dollars and hours honing and refining search

algorithms by analyzing the behavior of billions of users. Our study has

similar aims: we, like Google, want to find what types of content people

prefer and why. Of course, websites and scholarly articles are different,

and we consider those differences in our analysis.

8

See How Search Algorithms Work, GOOGLE,

https://www.google.com/search/howsearchworks/algorithms/ [https://perma.cc/HB2U-633K].

9

Id.

10

Brian Sutter, 7 User Engagement Metrics That Influence SEO, FORBES (Mar. 24, 2018, 5:32

PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/briansutter/2018/03/24/7-user-engagement-metrics-that-

influence-seo/#6726bec6567b [https://perma.cc/2DT3-DVAX].

11

Estimates of Google’s share of the search engine market vary, but it’s clear that Google

dominates. See, e.g., Search Engine Market Share Worldwide Jan - Dec 2019, STATCOUNTER:

GLOBAL STATS, https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/worldwide/2019

[https://perma.cc/RCX2-N6WD] (putting Google’s market share at 91.89 percent in 2019).

164

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

As it turns out, most of the characteristics we identify as increasing the

chances of citation align with generally accepted SEO principles. This

led us to examine other SEO principles for items that we did not include

in our study but that may apply to legal scholars. Below we layout the

findings of our study and the corollary SEO principles, followed by

additional SEO principles that we did not study but may still have

relevance.

“Black Hat” SEO & Manipulation of U.S. News’ Scholarly Impact

Of course, applying SEO principles to legal scholarship has the

potential to impact articles in both positive and negative ways, as we

touch on in our concluding section. Today, most SEO experts include

helping their clients create the “compelling and useful content” that

Google says it wants as a key part of their services.

12

In the early days

of SEO, this wasn’t the case. Early iterations of Google’s algorithm

were much less advanced, and SEO experts quickly discovered they

could trick the algorithm to get their client’s sites to rank higher.

13

As

Google caught on to these tricks, it adjusted its algorithm and essentially

punished websites that used these tactics.

14

These adjustments have

made Google’s algorithm more difficult to deceive.

15

The increased

difficulty, combined with the risks of Google penalizing sites caught

attempting to manipulate its algorithm, has led most SEO experts to

12

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Starter Guide, GOOGLE HELP: SEARCH CONSOLE HELP,

https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/7451184?hl=en [https://perma.cc/8B3F-

83PQ].

13

Razvan Gavrilas, 44 Black Hat SEO Techniques that Will Tank Your Site, COGNITIVE SEO,

https://cognitiveseo.com/blog/12169/44-black-hat-seo-techniques/ [https://perma.cc/8BRV-

NP42] (illustrating that examples of this include: keyword stuffing, the practice of adding

keywords in a way that hurts the writing; paying for links to your site; and so on).

14

Id.

15

But see Roger Montti, SEO Contest Exposes Weakness in Google’s Algorithm, SEARCH

ENGINE J. (Nov. 13, 2018), https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-algorithm-

loopholes/278093/

[https://web.archive.org/web/20200104220816/https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-

algorithm-loopholes/278093/] (discussing how a website written in nonsensical strings of

Latin nearly won a ranking contest between SEO experts).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

165

focus on making sites easy to use, easy for Google’s bots to access, and

filled with good content. As deceptive tactics fell out of favor, they

became referred to as “black hat” SEO.

16

Doing something with the intent of deception, even if the thing being

deceived is an algorithm, seems intrinsically wrong. Yet, attorneys can

likely understand the ethical dilemma that early SEO experts faced.

Like attorneys, SEO experts have a duty to advocate on behalf of their

clients. This includes the use of all legal methods. Most black hat SEO

tactics are not and have never been illegal, so many SEO experts viewed

using them as a duty to their clients. Further, black hat tactics became

so widespread that an expert who did not use these tactics risked letting

the sites they managed drop below inferior sites in the search result

rankings.

17

With the SEO background in mind, we wondered: will law schools

attempt to game and deceive the U.S. News and other ranking systems

the way early SEO experts gamed Google’s algorithm? They will have

similar motivations to those held by SEO experts, and the stakes for law

schools may even be higher. Plus, the early U.S. News system or other

scholarly impact ranking schemes may be particularly susceptible to

abuse, as Google’s algorithm was in its early days. Deans trying to

decide what to do may argue that not doing everything they can to

increase citation counts may lead to good schools dropping below peers

who choose to aggressively go after citations. Given these sorts of

arguments and the stakes involved, it seems likely that at least some

schools will try to manipulate the system. So, after our discussion on

ways to increase citations, we will briefly examine how schools and

scholars could manipulate the rankings.

16

What Is Black Hat SEO?, WORDSTREAM, https://www.wordstream.com/black-hat-seo

[https://perma.cc/EE83-YK75].

17

See A Brief History of SEO, HEROSMYTH (Apr. 20, 2020),

https://www.herosmyth.com/article/brief-history-seo [https://perma.cc/YYD9-WSMM].

166

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

To conclude the discussion of manipulative tactics, we want to point out

that the goal of this paper is not to create “black hat” tactics for legal

scholars. We do not recommend doing anything that will deceive

readers or algorithms. We recommend incorporating our suggestions

into your work only when you believe it can enhance the quality of your

work. There is a difference between purposefully manipulating a system

and applying lessons from the success of others to help your work have

a broader impact.

TL;DR

18

This article is on the longer side because the data indicates that longer

articles tend to be cited more often. However, we realize that many in

our target audience do not have time to read through and pull out all the

details. So, for those who just want a findings summary, we created a

simple chart.

19

18

TL:DR, MERRIAM WEBSTER, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/TL%3BDR

[https://perma.cc/YPF9-GRBD] (defining TL;DR as an informal abbreviation for “too long;

didn’t read.”).

19

We give full details on our dataset in the body of the paper, but a few notes may aid in

understanding the chart. Our study focused on three sets of articles from 2015-2019

(inclusive): one with the most-cited articles over that time period, a second with a subset of

articles with three citations, and a third where each article in the set has one citation and at

least one author with over 100 total citations to their name. We think the dataset with authors

that have over 100 total citations offers the best comparison to the top articles. Consequently,

the chart only includes the most-cited article data and the data from articles with one citation

written by at least one author with over 100 total citations.

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

167

Table 1: TL;DR Summary of Recommendations for Increasing

Citations

Recommendation Details More

Details

DO — Write long

articles

Top articles averaged 63 pages per

article.

The most frequently occurring page

lengths for top articles were 68 and 66

pages respectively.

79 percent of top articles were between

36-90 pages.

By comparison, less cited articles

averaged 27 pages, per article and 72

percent

ranged between 2

-

3

5

pages.

Page

174

DO — Keep titles

short

Top articles averaged 52 characters per

title.

The most frequently occurring title

lengths for top articles were 27 and 32

characters respectively.

Only 6.8 percent of top article titles had

over 100 characters.

By comparison, less cited articles

averaged 70 characters per title and 18

percent

had over 100 chara

cters per title.

Page

188

DON’T — use colons

in your title

Only 32 percent of top articles had a

colon in the title.

Comparatively, 55 percent of less cited

articles had a colon in the title.

Page

189

DO — Write on a

popular/timely topic

Articles on trending topics appear to garner

more citations per article than articles on other

topics.

Page

200

CONSIDER —

Publishing in widely

accessible journals

Limited data indicates that journals available

on Hein have more citations per article than

those with embargoes or not available.

Page

209

168

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

DO — Publish in a

top journal

37 percent of top articles were published

in one of 2018 W&L Law Journal

Rankings top-ten journals.

Only 4 percent of less cited articles were

published in one of 2018 W&L Law

Journal Rankings top

-

ten journals.

Page

212

CONSIDER —

Publishing with a co-

author

Our data only showed a slight difference in

number of authors per paper between different

segments, but other researchers have found

publishing with a co

-

author to be beneficial.

Page

215

DO

Read the rest of the article

.

Methodology

U.S. News’ proposal for its Scholarly Impact metric called for using

citations to articles available on HeinOnline and published in the

previous five years.

20

Since part of this paper looks at issues with U.S.

News’ proposal, and many law school deans and faculty are likely most

interested in any use of citations that may impact the U.S. News’

ranking, we used the five most recent years for our study. Further, the

databases, technologies, and expectations of authors change over time,

so what may have led to a high citation count fifteen or more years ago,

may not today.

21

We also chose to pull our data from HeinOnline (Hein)

20

Morse, supra note 4.

21

See Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 HARV. L. REV. 193

(1890) (the most cited article of all-time on HeinOnline, The Right to Privacy, does follow our

recommendation when it comes keeping the title short (just 20 characters), but it falls well

short of the ideal article length (28 pages, while the top articles in our study averaged 63

pages)). Also, below we discuss an older, similar study by Ian Ayres and Fredrick E. Vars. Ian

Ayres & Fredrick E. Vars, Determinants of Citations to Articles in Elite Law Reviews, 29 J.

LEGAL STUDS. 427, 440 (2000) (finding an optimal page length of 53 pages, less than our

study found optimal).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

169

because U.S. News plans to use Hein’s data for its ranking

22

and because

Hein, arguably, has the best collection of legal journals of any

database.

23

Hein includes data for number of times accessed, articles

citations, and case citations. U.S. News plans to use “citations,

publications and other bibliometric measures”

24

for its ranking. Since

there are comparatively few case citations, we used only article citations

to rank the articles in our datasets.

When we pulled our data on the most-cited articles, Hein had 242,924

published articles from 2015-2019 (inclusive) in its Law Journal

Library.

25

Since Hein had more articles than we could reasonably

collect data on and analyze, we opted to focus on the top and bottom

ends of the entire set of data, hypothesizing that any trends would be

most pronounced at the extremes. Picking the top was easy: we simply

gathered data on the 500 most-cited articles between 2015-2019 (we’ll

refer to this sample as the “top-articles”). Choosing what to include in

the bottom proved harder. There were roughly 4000 articles with 3

22

Morse, supra note 4; see also Paul Caron, U.S. News to Publish Law Faculty Scholarly

Impact Ranking in 2021, TAXPROF BLOG (Nov. 9, 2020),

https://taxprof.typepad.com/taxprof_blog/2020/11/us-news-to-publish-law-faculty-scholarly-

impact-ranking-in-2021.html [https://perma.cc/GM96-X3AY] [hereinafter Caron, U.S. News

to Publish] (publishing an email stating that U.S. News plans to publish its first scholarly

ranking in 2021 and will use Hein for data).

23

See Bonnie J. Shucha, Representing Law Faculty Scholarly Impact: Strategies for

Improving Citation Metrics Accuracy and Promoting Scholarly Visibility, 40 LEGAL

REFERENCE S. Q. 81 (2021).

24

Morse, supra note 4.

25

Hein is constantly adding articles to its collection. On May 21, 2020, less than a month after

we completed our data gathering for this portion, the count had gone up to 245,973.

HEINONLINE (2020). Further, Hein notes that its library now includes material beyond

traditional law journals. HEINONLINE MARKETING DEPARTMENT, LAW JOURNAL LIBRARY,

https://heinonline.org/HeinDocs/LawJournalLibrary.pdf (“Though initially named the ‘Law’

Journal Library, this resource has grown from a small collection of law reviews to a

multidisciplinary journals database spanning more than 39 million pages. Its coverage is

comprehensive, beginning with the first issue ever published, and includes works from 60

different countries, as well as all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The nearly 3900

journals in the library span more than 1500 research subjects, including political science,

history, technology, religion, business, gender studies, psychology, and many more.”).

170

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

citations, by including every tenth article in this subset, we would have

around 400 articles, giving us a similar sample size to the top-articles

sample. We’ll refer to this sample as the “bottom-articles, 3 citations.”

While gathering the articles with 3 citations, we realized that a

significant number were written by authors with only 3 total citations,

likely indicating students who only authored a single note or

comment.

26

It didn’t seem fair to compare students writing a single

article as a journal requirement with faculty whose careers depend on

scholarship. And, although we didn’t analyze this, it also seems possible

there is a bias against citing student authored work. We also noticed that

on average articles in the bottom sample were slightly younger than

those at the top.

27

This makes sense for the simple fact that the older

articles had more opportunity to garner citations.

28

Since the top-end we

had chosen had two clear advantages over our first bottom sample, we

decided to do a second bottom sample. For the second version, we

looked at articles with one citation and only included articles from 2015

where at least one author had 100 or more total citations to their name

(we’ll refer to this sample as the “bottom-articles, author over 100

citations”). 2015 is the oldest year in our study, which meant that

articles collected under the new criteria had maximum time to get cited.

One hundred total citations may not seem like that many when Hein’s

most cited author has 28,279 total citations,

29

but these top authors are

the exception, in a class by themselves. To get a sense of this, of the

faculty Hein currently lists as being associated with Yale, 18 percent

26

Having so few citations indicates little incentive to gain them and, likely, very few

published works. Although other scenarios are possible, we think it most likely that these are

students who wrote a single note as part of a journal requirement.

27

Adding up all the years in each data set and calculating the average had the most-cited

articles coming in at 2015.73, while the set with three citations came in at 2016.29.

28

Ayres & Vars, supra note 21, at 430; see also Whisner, supra note 6, at 170 (noting that

four out of the five most cited works from the study came from the study’s earliest year).

29

Law Journals - Most-Cited: Authors, HEINONLINE, https://heinonline.org/ (last visited May

21, 2020) (as of May 21, 2020, Cass Sunstein (28,279 article citations) led Richard Posner

(24,155 article citations) by 4124 citations). These citations were compiled using Hein’s

authors profiles. From the databases landing page, navigate to “Law Journal Library”; choose

“LibGuide”; choose “Most-Cited”; scroll down and select “Authors.”

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

171

have under 100 total citations.

30

If 18 percent of the faculty at a top

school have under 100 citations, it becomes clearer that one hundred is

a significant number of citations, requiring a concerted effort by the

author. Adding this requirement eliminated most student authored

works. For these reasons, we believe our bottom-articles, author over

100 citations has better data. However, despite its shortcomings, we

decided to also include our findings on the original bottom-articles, 3

citations sample to provide an additional perspective.

For our top-articles sample, we wanted to capture a complete picture at

one moment in time. To do that, we gathered all our data for that subset

from April 9 – 15, 2020. While gathering the data, we monitored for

any changes to the ordering of the articles — none were observed. With

the bottom datasets, we were less concerned with capturing them at an

exact moment in time as both were only samples of a larger set and, as

long as they met the criteria we set, would suffice for our needs. We

compiled our bottom-articles, 3 citations sample between March 5 –

April 23, 2020, and our bottom-articles, author over 100 citations

sample between March 3 – April 8, 2020.

Our study focuses on correlation, not causation. With so many

variables, proving causation is very challenging. However, we believe

that correlation can give a strong indication of what’s working even

without proving causality.

Citation Breakdown

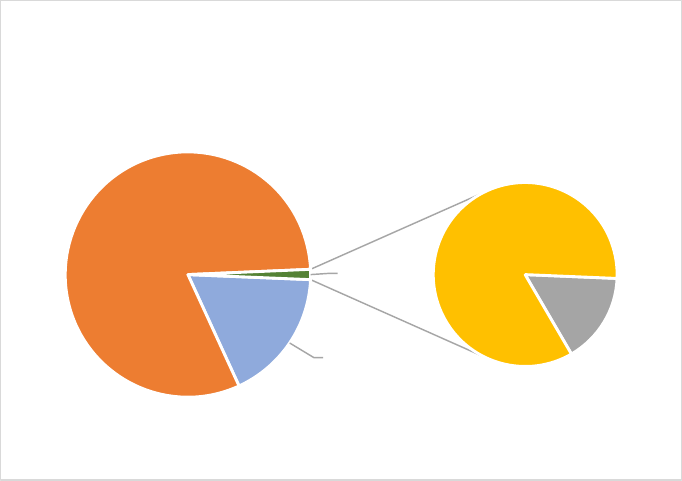

To gain context, the total population of law review articles from 2015-

2019 in Hein was 242,924 when we gathered our data. As detailed

above, we chose subsets of the top and bottom-most cited for our in-

30

We calculated these numbers with data from Hein’s author profiles. Author Profiles by

Institution: Yale Law School, HEINONLINE, https://heinonline.org/ (from the databases landing

page, navigate to “Law Journal Library”; choose “Author Profiles”; scroll down to access data

on Harvard and Yale).

172

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

depth analysis. We also grouped the entire set of 242,924 by number of

citations (i.e., how many articles had 10 citations, 11 citations, and so

on). The results surprised us. First, 199,865 (82 percent) of the articles

had zero citations.

31

Knowing how much time most authors invest in

writing these articles, we found this troubling, but also realized it

signaled a need for our article. Second, the number of citations needed

for an article to be considered a “well-cited” article within the past five

years, turned out to be lower than we had anticipated. Only the top 1.1

percent of all articles were cited ten or more times. Given this, it seems

reasonable to call any article with ten or more citations “well-cited.”

Further, it would certainly be fair to call an article with 24 citations (the

lowest number of citations any article in our top-articles sample had)

well-cited, especially since articles with 24 or more citations made up

only 0.2 percent of the total population.

31

Our percentages here vary a bit from an older study, where Thomas Smith found that 43

percent of articles are not cited at all, and about 79 percent get ten or fewer citations. Smith’s

study included articles much older than our five-year cap. So, this might indicate that there is

hope of citation for the articles not yet cited in our study—maybe citations will eventually

come their way. Or perhaps the citation network identified by Smith has grown even more

skewed in the time between his study and ours. Smith also included citations by cases, while

we only look at citations between articles. One final possibility is that the variation is due to

differences in coverage between LexisNexis, which Smith used, and HeinOnline. Thomas A.

Smith, The Web of Law, 44 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 309, 335-36 (2007).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

173

Figure 1: Citation characteristics for the full population of 242,924

articles

Characteristics of Well-Cited Articles

With an idea of the bigger picture and some background on our

methods, we will now discuss our findings in detail with a focus on how

the information can help authors increase their citation counts and

whether our findings align with those in the SEO world. Specifically,

this section discusses the differences we identified between the articles

in the top-articles sample and the two bottom-article samples. All the

differences between the characteristics discussed in this section are

statistically significant based on t-tests run in Excel, unless otherwise

indicated.

43,059

17.7 %

1-23 times

199,865

82.3 %

0 times

529

0.2 %

"top

articles"

24 or more

times

2787

1.1 %

3316

1.4 %

"well

cited"

10 times

Citation Count Breakdown (number of times cited)

Total number of articles is 242,924 (100%)

174

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

Others have studied correlations between easily measurable factors and

number of citations,

32

but, within the legal discipline there are

comparatively few citation studies.

33

Outside the legal field, there are

an abundance of studies looking at factors that influence citations.

34

Some of these studies considered data across multiple disciplines and

found that what can lead to citations in one discipline may not in

another.

35

For example, in some disciplines, longer titles do better,

while in others, shorter titles garner more citations (this is detailed

further below). The difference across disciplines means legal authors

should proceed with caution before relying on citation studies outside

the legal arena and keep the differences between disciplines in mind

when we discuss non-legal studies, including the SEO studies that we

focus on.

Characteristic One: Long Articles

Articles in the top-articles sample averaged 63 pages per article,

compared to 27 pages per article in the bottom-articles, author over

100 citations sample and 35 pages per article in the bottom-articles, 3

citations sample. Within the top-articles sample, the most frequently

occurring page lengths were 68 and 66 pages. As shown in Chart One:

Page Count Range and Frequency, the majority (57 percent) of

articles in the top-articles sample fell within 47-79 pages, with the vast

majority (79 percent) coming in between 36-90 pages. On the other side,

most (72 percent) of the articles in the bottom-articles, author over

32

E.g., Whisner, supra note 6, at 167.

33

Ayres & Vars, supra note 21. (Ian Ayres and Fredrick E. Vars produced the best study we

found, a well-done and thorough examination of factors that influenced citations of articles

published from 1980 to 1995 in the Harvard Law Review, Stanford Law Review, and The Yale

Law Journal).

34

See van Wesel et al., supra note 1, at 1602-04 (collecting studies on different factors that

increase citations across a wide range of disciplines and providing new research on various

factors that influence Sociology, General & Internal Medicine, and Applied Physics).

35

See, e.g., id. at 12.

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

175

100 citations were between 2-34 pages, with most (67 percent) of the

bottom-articles, 3 citations falling between 14-46 pages.

The longest article in the top-articles sample is 166 pages long and the

shortest comes in at 2 pages. Wide variations also appeared in both the

lower data sets: articles in the bottom-articles, author over 100

citations ranged from 1 to 94 pages and bottom-articles, 3 citations

had articles from 2 to 142 pages. Clearly, we have found trends, not

rules. The data establishes that you can write an article much shorter

than 63 pages and still get loads of citations. Likewise, you can write an

article over 60 pages and get few citations.

Figure 2: Pages per article (top articles only)

Our data shows that articles in our top-articles sample tended to be

significantly longer than those in our less-cited samples. Strengthening

this assertion, Ian Ayers and Fredrick Vars conducted a study much like

ours and found a similar correlation.

36

They looked at articles published

in Harvard Law Review, Stanford Law Review, and The Yale Law

36

Ayres & Vars., supra note 21, at 440.

176

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

Journal between 1980 and 1995.

37

Like us, they found that longer

articles tended to receive more citations than shorter ones.

38

However,

their research identified 53 pages as the optimal length for citations, ten

pages less than the average of our top-articles sample.

39

We did not

seriously investigate why the optimal length Ayers and Vars identified

turned out shorter than what we found, but we hypothesize that the

optimal article length has increased over time. A quick review indicates

that we might be correct: the top-ten most-cited articles from 1900-1910

averaged 23 pages long, with no articles over 35 pages.

40

The difference

between our results and Ayers and Vars could also stem from differing

methods of data analysis. Regardless of the reason, both our study and

Ayers and Vars found that longer articles tend to be cited more than

shorter ones.

41

Therefore, we recommend that scholars strive to write

longer papers, at least 50 pages in length (close to what Ayers and Vars

found, within where most articles in our top-article sample fell, and

over the length of most papers in both our less-cited samples).

Search Engines and SEO Experts Prefer Longer Content

How do Google and SEO experts feel about article length? Before

answering, we need to make clear that what is considered a long blog

post or webpage differs significantly from what most people consider a

long law review article. In December 2013, 74 percent of Medium

articles were 825 words or less (or roughly one and a half pages single

37

Id. at 429.

38

Id. at 440.

39

Id.

40

Reasons for this (and verifying the hypothesis) are outside the scope of this piece but could

include: relatively higher printing costs in earlier eras, earlier articles discussing areas of the

law that had yet to develop all the complexities they later did, or a desire of newer authors to

write longer articles than their predecessors.

41

Studies from other fields have made similar findings. See, e.g., John Hudson, Be Known by

the Company You Keep: Citations—Quality or Chance?, 71 SCIENTOMETRICS 231, 234 (2007)

(finding that citations increase as page length does in a study of two economic journals).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

177

spaced), with 94 percent under 1650 words (roughly 3 single spaced

pages).

42

With that context in mind, several studies indicate that Google and SEO

experts prefer longer content. First, Google appears to favor (i.e., rank

higher) longer content.

43

Second, a study of 912 million blog posts

found that longer content tends to get (a) more backlinks

44

and (b) more

social media shares.

45

Specifically, the study found that “long-form

42

Mike Sall, The Optimal Post Is 7 Minutes, MEDIUM: DATA LAB (Dec. 2, 2013),

https://medium.com/data-lab/the-optimal-post-is-7-minutes-74b9f41509b

[https://web.archive.org/web/20210217052851/https://medium.com/data-lab/the-optimal-post-

is-7-minutes-74b9f41509b] (“[o]verall, 74 percent of posts are under 3 minutes long and 94

percent are under 6 minutes long”). See also Read Time and You, MEDIUM: BLOG (June 3,

2014), https://blog.medium.com/read-time-and-you-bc2048ab620c

[https://web.archive.org/web/20210414144548/https://blog.medium.com/read-time-and-you-

bc2048ab620c] (“[r]ead time is based on the average reading speed of an adult (roughly 275

WPM). We take the total word count of a post and translate it into minutes. Then, we add 12

seconds for each inline image. Boom, read time.”).

43

See Matt Bentley, Data-Driven SEO Part 2: Does Long Content Really Rank Better?, CAN I

RANK, http://www.canirank.com/blog/does-long-content-rank-better/ [https://perma.cc/SRE2-

Y6KM] (discussing issues with other studies but still finding that longer content tends to rank

better than shorter content); see also Pandu Nayak, In-Depth Articles in Search Results,

WEBMASTER CENTRAL BLOG (Aug. 6, 2013),

https://developers.google.com/search/blog/2013/08/in-depth-articles-in-search-results

[https://perma.cc/U8Z3-82D6]; see also Dan Shewan, What Is Long-Form Content and Why

Does It Work?, WORDSTREAM: BLOG (Aug. 27, 2019),

https://webmasters.googleblog.com/2013/08/in-depth-articles-in-search-results.html

[https://perma.cc/A3VY-FBQJ] (stating that a Google search algorithm update was designed

to “help users find in-depth articles”).

44

Backlinks are links from another website to yours.

45

Brian Dean hypothesized that one reason longer content may rank better is because it has

more backlinks, one of the ranking signals used by Google. However, Bentley argues that long

content actually does not get more backlinks and long content ranks better simply because it

actually tends to be better. Bentley’s sample size is smaller than Dean’s. Regardless of who is

right on the backlinks point, both agree that longer content ranks better—only the reason is in

dispute. See Brian Dean, We Analyzed 912 Million Blog Posts: Here’s What We Learned

About Content Marketing, BACKLINKO (Feb. 19, 2019), https://backlinko.com/content-study

[https://perma.cc/PXY6-QC5F]; see also Shewan, supra note 43 (discussing WordStream’s

increased user engagement and traffic with the website’s switch to longer content and

178

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

content gets an average of 77.2 percent more links than short articles.”

46

It found that, while the preferred length is shorter for social shares than

backlinks, longer content still outperforms shorter content, with posts

of 1000 to 2000 words getting 56.1 percent more shares than ones with

less than 1000 words.

47

User preference for longer web content implies that most people using

Google

48

prefer longer content. We consider the increase in backlinks

and social shares especially relevant because backlinks (links from an

outside site to the studied site)

49

and social media shares are the web

equivalents of citations in academic journals, with backlinks being the

stronger corollary.

50

When an author cites another author, they usually

do so to support a claim they’ve made or, less often, to refute the other

author. Either way, the cited author has done enough to gain the

attention of their peers. Similarly, when a webpage links to another

additional studies finding benefits with longer content); see also Ideal SEO Content Length:

Flushing the Goldfish Cliché Down the Toilet, SWEOR (Mar. 5, 2020),

https://www.sweor.com/seocontentlength [https://perma.cc/8ZXZ-5HQR]. But see Bentley,

supra note 43 (finding, in a smaller study, that longer content does not bring more links).

46

Dean, supra note 45.

47

Id. But see Matthew Howells-Barby, The Anatomy of a Shareable, Linkable & Popular

Post: A Study of Our Marketing Blog, HUBSPOT (Sept. 16, 2015),

https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/seo-social-media-study [https://perma.cc/D9RR-QGCL]

(finding that the longest articles got the most social shares in a study of 6192 blog posts in late

2015).

48

This article only looks at articles written in English and, consequently, also only considers

English SEO findings and recommendations, with a focus on the U.S.

49

Backlinks are also referred to as “inbound links” or “incoming links.” If a New York Times

article linked to a Wall Street Journal article, the Wall Street Journal article would have a

backlink from the New York Times article.

50

Interestingly, just as most of the articles in the period we looked at had zero citations, most

blog posts get zero backlinks or social shares. Dean, supra note 45 (“[t]he vast majority of

online content gets few social shares and backlinks. In fact, 94 percent of all blog posts have

zero external links.”).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

179

page, it does so either to support or refute something said on the page.

51

Tweets and other social shares have similar purposes. The fact that both

long web pages and long legal articles get more attention than short ones

signals a preference in both areas for longer content. To sum up, the

SEO research aligns with what we found: longer content is generally

more likely to be cited. However, as we touched on above, our study,

the one by Ayres and Vars, and some SEO studies found the benefit of

length only extends so far.

52

Why Longer Content Gets More Citations

As to why longer content is more cited, we identified several possible

reasons. More content means an opportunity to cover more topics,

including tangential ones. If an article focused on antitrust has a well-

done section on law and economics, perhaps citations to the law and

economics portion push the article’s citation count past similar articles

that only discuss antitrust. Hein uses artificial intelligence to create a

list of topics for many articles in its Law Journal Library.

53

While

collecting data, we recorded and counted these topics. The top-articles

sample averaged 5.29 topics per article, while the bottom-articles,

author over 100 citations sample averaged 4.90 and the bottom-

articles, 3 citations 5.12.

54

The difference between the top-articles and

bottom-articles, author over 100 citations supports our inference that

51

Because links signal to Google support for the linked to website, savvy website owners will

tell the search engine when they do not actually support the content they are linking to. See

The Beginner’s Guide to SEO: Link Building & Establishing Authority, MOZ,

https://moz.com/beginners-guide-to-seo/growing-popularity-and-links

[https://perma.cc/R4U8-XFZS] (discussing follow vs. no-follow links and how they can be

used to avoid passing support to a linked to website).

52

See Dean, supra note 45 (finding that 1000-2000 words is the optimal length for social

media shares); see also, Sall, supra note 42 (finding 7 minutes, roughly 1600 words, to be the

optimal length for capturing the most reading time).

53

Lauren Mattiuzzo, Alexa: Research Artificial Intelligence in HeinOnline for Me,

HEINONLINE BLOG (Jan. 14, 2020), https://home.heinonline.org/blog/2020/01/alexa-research-

artificial-intelligence-in-heinonline-for-me/ [https://perma.cc/RS65-UABE].

54

Note that while the difference between 5.29 and 4.90 is statistically significant, the

difference between 5.29 and 5.12 is not.

180

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

covering more topics may increase an article’s citation count. Further,

another study of law review citations found that only two out of the 100

citations they reviewed cited the article to build on or respond to it.

55

The other 98 were either used to support a fact or opinion or for unclear

reasons.

56

If articles are mainly being cited for facts or opinions, an

article with factually accurate tangents has more chance of being cited

than one without.

Another possibility, offered by some SEO experts

57

and at least one law

professor,

58

is that readers equate length with authority or expertise.

This seems logical. In the legal arena, we tend to assume that a multi-

volume treatise is more authoritative than a single volume hornbook.

We also generally think books provide a greater level of detail than

articles, and so on. Since most authors want to support their assertions

with the most authoritative content available, it follows that they would

prefer longer articles to shorter ones when given the choice.

It may also be that readers consider longer articles easier to skim.

Personally, we find reading a dense, 100+ page article daunting and

often not worth the effort when we only need a small portion of it. Our

guess is that at least some other members of the legal community feel

similarly. For us, and like-minded scholars, scanning a long article to

quickly home in on what you need is often faster than reading an entire

short article. Further, perhaps authors of longer articles realize that

55

Jeffrey L. Harrison & Amy R. Mashburn, Citations, Justifications, and the Troubled State

of Legal Scholarship: An Empirical Study, 3 TEX. A&M L.R. 45, 74 (2015); see also James E.

Krier & Stewart J. Schwab, The Cathedral at Twenty-Five: Citations and Impressions, 106

YALE L.J. 2121, 2122 (1997) (stating that survey articles are cited frequently because they

conveniently convey facts).

56

Harrison & Mashburn, supra note 55.

57

Manick Bhan, Content Length and SEO: Does it Really Matter?, LINKGRAPH (Mar. 9,

2020), https://linkgraph.io/content-length-and-seo-does-it-really-matter/

[https://perma.cc/6HDE-87PE] (“[l]ong copy gives the impression of expertise, credibility,

and extensive knowledge on a topic.”).

58

See Scott Dodson, The Short Paper, 64 J. LEGAL EDUC. 667, 668 (2014) (arguing against

long papers but stating that legal scholars “use length as a proxy for the value of the work”).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

181

increased length requires tighter organization and use additional reading

aids that make it easier to scan the content, like a table of contents and

plenty of headings. When it comes to shorter articles, some researchers

might feel guilty about not reading the entire thing and may fear missing

the part most important to them if they do not. When this is the case,

reading a “short” twenty-page article will usually take longer than

scanning a 100-page piece and only reading the five relevant pages.

Some SEO experts have drawn similar conclusions.

59

We did not gather

any data relevant to this hypothesis, but, as discussed further below,

authors of long articles should do their best to make skimming easy for

their readers.

Most SEO experts agree that the earlier a website appears in search

results, the more likely a searcher will view it.

60

It is very likely that the

top results in legal databases also get more traffic than the lower ones,

suggesting another possible reason longer articles are cited more often.

Depending on the database’s algorithm, longer articles may appear

higher in legal database search results, making them more likely to be

found and cited. Early versions of Google’s algorithm ranked content

higher partially based on the number of times a searched-for word

appeared on a website.

61

Google has since adjusted its algorithm, but

the legal databases most people use for law reviews have less

sophisticated search algorithms that may still use the total number of

times the searched for keyword appears as a factor in ranking results by

59

Neil Patel, How Long Should Your Blog Articles Be? (With Word Counts for Every

Industry), NEILPATEL: BLOG, https://neilpatel.com/blog/long-blog-articles/

[https://web.archive.org/web/20210421223524/https://neilpatel.com/blog/long-blog-articles/].

60

E.g., Kelly Shelton, The Value of Search Results Rankings, FORBES (Oct. 30, 2017, 8:00

AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2017/10/30/the-value-of-search-

results-rankings/#6bc667c144d3 [https://perma.cc/9B8U-BH3Z] (discussing studies that

found websites on the first page of Google’s search results get between 71 percent and 92

percent of clicks, with second page results getting only 6 percent).

61

See Megan Marrs, The Dangers of SEO Keyword Stuffing, WORDSTREAM: BLOG (Oct. 23,

2017), https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2012/03/21/dangers-of-keyword-stuffing

[https://perma.cc/6P4C-JTLZ] (explaining that increasing the number of times a keyword

appeared on a website was once a way to rank better for that keyword).

182

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

relevance.

62

Additionally, the main legal databases (Westlaw and Lexis)

allow users to run searches that only display results where the entered

keyword occurs at least x number of times, favoring longer articles.

63

Longer articles also have more space and opportunity to work in related

keywords and synonyms that authors may search for, further increasing

their chances of appearing sooner in search results.

64

Again, our data

does not support or disprove this assertion, but it does seem possible

that part of the success longer articles enjoy stems from favorable

treatment by the legal database algorithms and search options.

While we suspect all legal database algorithms lag behind Google, some

do claim significant advances. For example, Westlaw has claimed to be

“the world’s most advanced legal search engine.”

65

For different

reasons, long articles could also excel within more advanced legal

search algorithms, as long webpages do in Google’s algorithm.

Google’s algorithm favors webpages that users spend more time on.

66

In the past, Westlaw has stated that its algorithm determines relevancy

62

Susan Nevelow Mart, The Algorithm as a Human Artifact: Implications for Legal

[Re]Search, 109 L. LIBR. J. 387 (2017).

63

Developing a Search with LexisNexis, LEXISNEXIS, https://www.lexisnexis.com/bis-user-

information/docs/developingasearch.pdf [https://perma.cc/G75W-VJYZ]; Westlaw Edge Tip:

What Is the “At Least” Function, and How Do I Use It?, THOMSON REUTERS,

https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/blog/westlaw-edge-tip-what-is-the-at-least-functional-and-

how-do-i-use-it/ [https://perma.cc/4XHH-87AU].

64

See How to Keep Keyword Density Natural and Avoid Keyword Stuffing, SEMRUSH: BLOG

(Apr. 15, 2013), https://www.semrush.com/blog/how-to-keep-keyword-density-natural-and-

avoid-keyword-stuffing/ [https://perma.cc/LLN3-5R43] (stating that the best way to

“naturally” avoid keyword stuffing is to increase the word count).

65

WestSearch: The World’s Most Advanced Legal Search Engine, WESTLAW,

http://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/wln2/l-355700_v2.pdf

[https://perma.cc/U7NZ-25UR]; see also Mart, supra note 61, at 413-15 (finding that

Westlaw’s algorithm delivers the most relevant results among the legal databases studied).

66

Dean, supra note 45.

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

183

based on a variety of factors, including “usage by research

professionals.”

67

Ultimately, we cannot be sure how Westlaw’s proprietary algorithm

currently works, but it is possible that it has followed the industry

leader, Google, and factored in the amount of time users spend viewing

content. Long articles require more time to read, at least if you read all

the content (see above for an instance where that may not be the case).

Thus, a long article may fair better in an algorithm that factors in the

amount of time a user spends on a page. Additionally, Westlaw has

previously stated that it factors in “meaningful interactions” when

ranking and returning results.

68

The listed examples of “meaningful

interactions” Westlaw gives, include print, email, and downloads.

69

Pre-

COVID, research showed a preference for print when it comes to longer

sources.

70

Further, personal experience and logic dictate that users are

67

Compare WestlawNext Q&A Session: Refining Your Results, THOMPSON REUTERS: LEGAL

SOLUTIONS BLOG (June 18, 2010), https://blog.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/legal-

research/westlawnext-qa-session-refining-your-results/

[https://web.archive.org/web/20181003060731/https://blog.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com

/legal-research/westlawnext-qa-session-refining-your-results] (responding to the question,

“[h]ow is relevancy determined?” by stating that “[r]elevancy is determined by a number of

factors that include search terms, KeyCite, key numbers, and usage by research

professionals”), with WestSearch: The World’s Most Advanced Legal Search Engine,

WESTLAW, http://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/wln2/l-355700_v2.pdf

[https://perma.cc/26AR-FBTA] (stating only that Westlaw’s search algorithm emulates “the

best practices of experienced legal researchers”); and Westlaw Edge: The Most Intelligent

Legal Research Service Ever, THOMPSON REUTERS: LEGAL,

https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/westlaw [https://perma.cc/TV77-XSXT]

(making no mention of user behavior as a factor in the search process).

68

WestlawNext Q&A Session: Refining Your Results, supra note 67.

69

Id.

70

Matt Enis, Academic Ebook Sales Flat, Preference for E-Reference Up, LIBR. J. (Sept. 28,

2020), https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=academic-ebook-sales-flat-preference-

for-e-reference-up# [https://perma.cc/2H9S-QLJ2]; Bethany Cartwright, We Asked Our

Audience What They Really Think of PDF Ebooks: A HubSpot Experiment, HUBSPOT:

MARKETING (June 23, 2017, 8:00 AM), https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/pdf-preferences-

184

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

more likely to print, email, or download a longer piece for later because

reading will require setting aside time and may need to be done over

multiple sessions. As with the time on page theory, we cannot be sure if

Westlaw, or other databases, still factor in print, email, and downloads.

If they do, it could lead to long articles appearing earlier in search

results, increasing their chances of being cited.

Ultimately, we cannot definitively determine why longer articles tend

to get more citations. Investing additional effort in researching theories,

like a feeling that longer articles are more authoritative, could provide

more insight. However, the proprietary nature of the algorithms that

deliver users’ results and likely play a role in citations (by putting some

articles earlier in search results) would make exploring some of our

other ideas challenging. So, while verifying these theories is outside the

scope of this paper, we thought readers would still find them interesting

and hope that we, or other researchers, can explore these sometimes-

competing ideas in the future.

Suggestions to Lengthen Articles

Having established a link between article length and number of

citations, we now offer suggestions on how to lengthen articles without

negatively impacting quality. Practically speaking, it is helpful to know

how many words are on a typical law journal page, as it might differ

from the word processor you use to draft your work. While it will vary

depending on the law journal, the general rule that law journals have

experiment [https://perma.cc/7D6L-N45F]; But see Matt Enis, College Students Prefer Print

for Long-Form Reading, Ebooks for Research, LIBR. J. (Mar. 27, 2018),

https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=college-students-prefer-print-long-form-reading-

ebooks-research-lj-survey [https://perma.cc/B9WF-KAEY] (indicating students prefer ebooks

when researching).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

185

adopted is 5000 words equals ten law review pages.

71

To flesh that out

further:

Table 2: Conversion: Number of Words to Number of Pages

72

Number of Words

Number of Pages

5

,

000 words

10 pages

10,000 words

20 pages

15,000 words

30 pages

20,000 words

40 pages

25,000 words

50 pages

30

,000 words

60 pages

35,000 words

70 pages

40,000 words

80 pages

Based on our findings, you should target between 25,000 to 35,000

words, the equivalent of roughly 50-70 law journal pages.

Another practical consideration: many journals limit article length.

73

In

fact, a good number claim to limit article length below 63 pages.

74

So,

71

See Allen Rostron & Nancy Levit, Information for Submitting Articles to Law Reviews &

Journals, SSRN, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1019029

[https://perma.cc/KDZ5-KZL2].

72

Conversion chart created from understanding of Joint Statement of eleven law reviews

concerning article length. See, e.g., Article Length, DUKE L.J. (2021),

https://dlj.law.duke.edu/about/submissions/article-length/ [https://perma.cc/4B6H-Z9BN].

73

For example, Drexel Law Review, Florida Law Review, and North Carolina Law Review all

“prefer” submissions no longer than fifty law review pages (including footnotes); Harvard

says it “[w]ill not publish articles exceeding 30,000 words (roughly 60 law review pages)

except in extraordinary circumstances;” Stanford Law Review has a limit of 30,000 words

(roughly 60 law review pages) and “values brevity and looks favorably on pieces significantly

below the 30,000 word ceiling”; St. Thomas Law Journal “wants only 5,000 to 15,000 words

(roughly 30 law review pages), excluding footnotes. Rostron & Levit, supra note 71.

74

Id. (A few exceptions from the journals examined in Information for Submitting Articles to

Law Reviews & Journals, include Texas Law Review, where most articles should be within

the 40–70-page range, and Vanderbilt, which prefers “submissions of 20,000 to 35,000 words,

including text and footnotes (40 to 70 journal pages”)).

186

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

what should an author do when debating between hitting a word count

that could increase citations and one that will meet a journal’s

requirements? First, there is evidence that journals do not follow their

own article length limits, assuming that is the case, then authors have

no reason to limit length.

75

Second, if authors are faced with an actual

choice, they should consider the journals they are targeting.

76

If all are

similarly ranked, then our data suggest preferring journals that do not

have page limits.

Of course, when attempting to increase your word count, you should not

simply fill your article with extraneous words. Instead, focus on how

you can improve the article with additional length. The SEO world has

tools that can help with this by finding related topics and concepts.

77

However, SEO tools target and tend to work best with more general

topics and struggle to provide useful information on the complex,

nuanced, and niche topics of most law review articles.

78

So, while SEO

tools may be worth a look to see if they prompt you to think of a new

avenue, their actual results will likely be of limited use. Instead, focus

on applying the concepts behind the tools. Put yourself in the reader’s

75

Stephen M. Bainbridge, Law Review Word Limits Go Unenforced .... at Least at Harvard

and Yale, PROFESSORBAINBRIDGE.COM (Oct. 15, 2013),

https://www.professorbainbridge.com/professorbainbridgecom/2013/10/law-review-word-

limits-go-unenforced-at-least-at-harvard-and-yale.html [https://perma.cc/8ETV-6BM5].

76

As an aside, many of the journals with limits say something similar to the Cornell’s flagship

journal, “[t]he Cornell Law Review will not publish pieces exceeding 35,000 words except in

extraordinary circumstances.” Submitting Articles and Essays to Cornell Law Review,

CORNELL L. REV.: SUBMISSIONS, https://www.cornelllawreview.org/submissions/

[https://perma.cc/65D4-TA2V]. However, we did not see any journals that listed what

constitutes “extraordinary circumstances.” If it is related to the author’s name recognition,

then that would seem unfair because it is limiting the ability of those who most need citations

to get them, while allowing well-known authors to further pad their citation counts and

increase the gap over their less well-known peers. Rostron & Levit, supra note 71.

77

Joshua Hardwick, 10 Free Keyword Research Tools (That Aren’t Google Keyword

Planner), AHREFS BLOG (Apr. 7, 2021), https://ahrefs.com/blog/free-keyword-research-tools/

[https://perma.cc/D8TQ-HAEQ].

78

E.g., ANSWERTHEPUBLIC, https://answerthepublic.com/ (search run May 26, 2020) (a search

for “Agency Statutory Interpretation” pulls up zero questions, while a search for “fashion”

generates eighty).

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

187

shoes. What additional questions might they have that are relevant to

your paper? Consider running your article by colleagues or students to

see where they have questions or would like more detail. While this

manual approach lacks the amount of data behind SEO tools, it should

generate additional ideas. Do not focus solely on yourself; remember

your audience and keep in mind what will interest them.

Additionally, consider how extra length can help your article to rank

better in search algorithms.

79

If you can do it naturally, work in

synonyms and similar words for your most important points. Like SEO

experts, we only recommend this approach if you can do it naturally.

80

Not only will you hurt your chances of being cited if your writing is

poor, but Google eventually altered its algorithm to punish websites that

unnaturally crammed in keywords in an effort to rank higher.

81

We

suspect that legal search engines would do the same if the practice

became widespread in legal scholarship.

Example Articles

For those who are curious, we decided to include a few example articles

that support our findings. Remarkably, the most cited article in our

study, Big Data's Disparate Impact, came in at 62 pages (recall that the

average number of pages for articles in our top-articles sample is 63

pages) and, when the data was collected, had 177 citations. Was this

article by Cass Sunstein, the most cited author on Hein (28,239 citations

when the top-articles data was gathered)? No. It was authored by Solon

Barocas (cited 329 times when the data was gathered) and Andrew D.

Selbst (cited 266 times). On the other side, Government-Operated

79

Michelle Ebbs, 10 Easy Ways to Increase Your Citation Count: A Checklist, AJE SCHOLAR,

https://www.aje.com/arc/10-easy-ways-increase-your-citation-count-checklist/

[https://perma.cc/VU5A-K6XP]; e.g., Joran Beel et al., Academic Search Engine Optimization

(ASEO): Optimizing Scholarly Literature for Google Scholar & Co., 41 J. SCHOLARLY

PUBLISHING 176, 184 (2010).

80

How to Keep Keyword Density Natural and Avoid Keyword Stuffing, supra note 64.

81

See Irrelevant Keywords, GOOGLE SEARCH CENTRAL,

https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/66358?hl=en [https://perma.cc/GA9U-JEX2]

(stating that overloading with keywords “can harm your site's ranking”).

188

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

Drones and Data Retention, comes in at 22 pages and has only 1

citation, despite the timely and compelling topic. Of course, these are

just examples used to illustrate the point. Our data set also has counter

examples, like Cass Sunstein’s Chevron as Law, which had only 3

citations when the data was gathered despite the recognizable author

and its 72-page length.

Are Longer Articles Really Better?

Our article focuses on what types of articles are more likely to be cited.

While the data indicates longer articles are more likely to be cited, this

does not mean that they are actually better. Personally, we dread the

idea of reading a 60+ page law review article and agree with Scott

Dodson that shorter is better.

82

However, with longer articles being cited

more often, it seems likely they are here to stay. Changing this trend

would require putting less emphasis on citations and finding another

proxy for value.

Characteristic Two: Short Titles Without Colons

Title Length

The average title in the top-articles sample had 52 characters (including

spaces). The bottom-articles, author over 100 citations sample

averaged 70 title characters, while the bottom-articles, 3 citations

sample had an average of 73 characters per title. Within the top-articles

sample, the two most frequently occurring title lengths were 27 and 32

characters. In the top-articles sample, 60 percent of the article titles had

between 19-57 characters, while 66 percent of the titles in the bottom-

articles, author over 100 citations sample fell between 34-98

characters, and 64 percent of the bottom-articles, 3 citations sample

titles were between 25-89 characters (see chart below for a visual

overview of the distribution). Further, 76 percent of articles in the top-

82

Dodson, supra note 58, at 667.

2021]

WILLEY & KNAPP

189

articles sample fell below 70 characters and only 7 percent were over

100 characters, while in the bottom-articles, author over 100 citations

sample, 54 percent fell under 70 characters, and 18 percent came in over

100 characters. In sum, while “short” is a relative term, we found that

articles with more citations tend to have shorter titles when compared

to less cited articles.

While character length is the most precise measure of title length, word

count provides a different and useful perspective. In the top-articles

sample, titles averaged 7.30 words, while the bottom-articles, author

over 100 citations sample averaged 10.28 words, and the bottom-

articles, 3 citations sample averaged a nearly identical 10.67 words. 60

percent of the titles in the top-articles sample had between 1 and 7

words and 84 percent fell below 12 words, with the two most common

title lengths coming in at 3 and 5 words respectively. Thus, titles with

fewer words tended to be cited more often in our dataset.

Not all articles followed the trends in their respective samples. The

longest title in the top-articles sample came in at 210 characters, while

the shortest title was 5 characters. Titles in the bottom-articles, author

over 100 citations sample ranged from 7 to 194 characters, with the

bottom-articles, 3 citations sample titles coming in between 11 and

218 characters. As with article length, the ranges indicate that we found

title length trends, not rules.

Title Colons

Whether a title had a colon also proved statistically significant, with

more cited articles less likely to include a colon in the title. Thirty-two

percent of titles in the top-articles sample had colons, while 55 percent

of titles in the bottom-articles, author over 100 citations sample, and

50 percent of titles in bottom-articles, 3 citations sample had colons.

190

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 18.1

Additional Academic Studies

Studies outside the legal realm indicate that whether long or short titles