www.collegeboard.com

Research Report

No. 2009-5

Examining the

Accuracy of

Self-Reported

High School

Grade Point

Average

Emily J. Shaw and Krista D. Mattern

The College Board, New York, 2009

Emily J. Shaw and Krista D. Mattern

Examining the Accuracy of

Self-Reported High School

Grade Point Average

College Board Research Report No. 2009-5

Emily J. Shaw is an assistant research scientist at the

College Board.

Krista D. Mattern is an associate research scientist at the

College Board.

Researchers are encouraged to freely express their

professional judgment. Therefore, points of view or

opinions stated in College Board Reports do not necessarily

represent official College Board position or policy.

The College Board

The College Board is a not-for-profit membership

association whose mission is to connect students to college

success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College

Board is composed of more than 5,700 schools, colleges,

universities and other educational organizations. Each

year, the College Board serves seven million students

and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,800 colleges

through major programs and services in college readiness,

college admission, guidance, assessment, financial aid,

enrollment, and teaching and learning. Among its best-

known programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT® and

the Advanced Placement Program® (AP®). The College

Board is committed to the principles of excellence and

equity, and that commitment is embodied in all of its

programs, services, activities and concerns.

For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com.

© 2009 The College Board. College Board, Advanced

Placement, Advanced Placement Program, AP,

SAT, Student Search Service and the acorn logo are

registered trademarks of the College Board. Admitted

Class Evaluation Service, ACES and inspiring minds

are trademarks owned by the College Board. PSAT/

NMSQT is a registered trademark of the College Board

and the National Merit Scholarship Corporation. All

other products and services may be trademarks of their

respective owners. Visit the College Board on the Web:

www.collegeboard.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mary-Margaret Kerns

and two anonymous reviewers for their very useful

comments on an earlier draft of this paper. The editorial

assistance of Robert Majoros was also appreciated. Special

thanks to Sandra Barbuti and Mylene Remigio for their

assistance in preparing the database for analysis.

Contents

Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Examining the Accuracy of Students’ Self-Reported

High School Grade Point Average . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

The SAT® Questionnaire and Self-Reported

HSGPA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Sample . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Materials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

SAT Scores . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

SAT Questionnaire (SAT-Q) Responses . . . 2

School-Reported HSGPA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Self-Reported HSGPA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Design and Procedure: Cleaning and Scaling the

HSGPA Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Descriptive Statistics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Reliability: Correlations Between Self-Reported

and School-Reported HSGPA . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Tables

1. HSGPA Grading Scales Across Higher

Education Institutions in the Study . . . . . . . . . . 8

2. Recoding of School- and Self-Reported

HSGPA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

3. Descriptive Statistics for the Academic

Measures (N = 40,301) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

4. Self-Reported Versus School-Reported

HSGPA Accuracy: Correlations, Percentage

of Exact HSGPA Match, Underreporting and

Overreporting of HSGPA in Grade Steps by

Race/Ethnicity, Parental Income, Parental

Education Level and SAT Score Band . . . . . . . . 9

5. Accuracy of Self-Reported HSGPA by HSGPA

Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

6. Percentage of Exactly Matching,

Underreporting, and Overreporting of HSGPA

by Demographic Characteristics in the SAT

Score Band . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Figures

1. HSGPA self-reported item on the SAT

Questionnaire (2005–2006) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2. Percentages of students underreporting, exactly

matching or overreporting their HSGPA . . . . 13

1

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between students’

self-reported high school grade point average (HSGPA)

from the SAT® Questionnaire and their HSGPA provided

by the colleges and universities they attend. The purpose

of this research was to offer updated information on the

relatedness of self-reported (by the student) and school-

reported (by the college/university from the high school

transcript) HSGPA, compare these results to prior studies

and provide recommendations on the use of self-reported

HSGPA. Results from this study indicated that even

though the correlation between the self-reported and

school-reported HSGPA is slightly lower than in prior

studies (r = 0.74), there is still a very strong relationship

between the two measures. In contrast to prior studies,

students underreport their HSGPA more often than

they overreport it. This shift could be due to a variety

of factors, including changes in grading practices in

high schools such as grade inflation, increased student

confusion in reporting weighted averages, variation in

recalculations of HSGPA by colleges and universities, and

other methodological factors.

Examining the

Accuracy of Students’

Self-Reported High

School Grade Point

Average

It is not uncommon to make use of self-reported

information from students, such as high school grades, test

scores, and extracurricular activities, in higher education

research. Primarily due to the difficulty and legality

in obtaining official school records or documentation

of such information, researchers and higher education

administrators are forced to rely on and make inferences

using students’ self-reported information. The question

then remains whether or not the self-reported information

is trustworthy or accurate. In particular, this paper will

focus on the accuracy of self-reported HSGPA across

all students, as well as by selected subgroups, including

gender, race/ethnicity, parental education and income

level, and SAT score band.

Prior research has examined the accuracy of students’

self-reported grades as compared to their actual grades

and has shown that there is a high correlation between

the two. Maxey and Ormsby (1971) analyzed a sample

of almost 6,000 students from 134 high schools, and

found that the correlation between self-reported and

actual grades ranged from 0.81 to 0.86. They did not

find any bias in the accuracy of reporting grades by

race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status, although they

did find that females tended to report their grades

slightly more accurately than males. Maxey and Ormsby

indicated that their findings support the validity of self-

reported grades for use in higher education research.

After reviewing a number of studies on this topic,

Baird (1976) also agreed that self-reported grades are as

useful as school-reported grades, citing that correlations

generally ranged from 0.80 to 0.96. Sawyer, Laing, and

Houston (1988) analyzed self-reported grades in various

courses with students’ actual grades from high school

transcripts. The results showed a median correlation

of 0.80, with higher accuracy for more content-specific

courses, such as chemistry, than for more diverse or

open-ended course work, such as “other history” (p. 11).

Similarly, in 1991, Schiel and Noble found the median

correlation between self-reported and actual grades in

various courses by sophomores from 83 high schools in

one Southern state to be 0.79. They concluded that while

self-reported grades appear to be sufficiently accurate

for use in research, they may not be the best information

to use when making crucial decisions about students,

such as admission decisions.

Most recently, Kuncel, Credé, and Thomas (2005)

conducted a meta-analysis of the validity of self-

reported HSGPA among other academic measures.

They examined 37 studies that included 60,926 students

and found the correlation between self-reported HSGPA

and actual HSGPA to be 0.82. The correlations were

also computed by gender and race/ethnicity. Kuncel

et al. did not find large differences in the validity of

self-reported HSGPA between females and males (0.82

versus 0.79, respectively); however, they did find that

the validity of self-reported HSGPA was greater for

white students than for nonwhite students (0.80 versus

0.66, respectively). Additionally, they found that lower

actual academic performance, based on SAT scores, was

associated with lower reliability of self-reported grades.

Kuncel et al. argued that self-reported grades may

be valuable and accurate reflections for academically

higher-performing students but are of much less use for

academically lower-performing students.

2

The SAT

®

Questionnaire and

Self-Reported HSGPA

The SAT Questionnaire, completed at the time of SAT

registration, asks students a number of questions regarding

their demographic and educational backgrounds, as well

as their academic interests and preferences in college or

university characteristics. This questionnaire is revised

periodically and is widely used in College Board research,

as well as by other researchers requesting these data.

One item from this questionnaire, commonly used in

educational research, asks students to indicate their

HSGPA on a 12-point scale ranging from a high of A+

to a low of E or F (see Figure 1). Research by Boldt (1973)

on the first version of the SAT Questionnaire, formerly

known as the Student Descriptive Questionnaire (SDQ),

found a median correlation of 0.87 between self-reported

and school-reported HSGPA, and that 79 percent of self-

reported and school-reported HSGPAs matched exactly

(as cited in Baird, 1976).

When there was a major revision to the SAT

Questionnaire in the 1985-86 academic year, Freeberg

(1988) studied the accuracy of student responses on

this updated instrument and found the correlation

between self- and school-reported HSGPA to be 0.79.

Additionally, 87 percent of the sample of 6,039 students

had a self-reported HSGPA that matched their actual

HSGPA. However, it should be noted that Freeberg’s

definition of an exact match was extremely broad,

with an A+ through a B–, for example, considered as

one grade unit or an exact match. Of those students

whose self-reported HSGPA did not match their actual

HSGPA, Freeberg found that students were much more

likely to overreport rather than underreport their

HSGPA. Freeberg noted that there were only very

slight differences in overreporting or underreporting by

gender and by race/ethnicity when controlling for prior

academic performance; however, students with a lower

actual HSGPA were far more likely to overreport their

HSGPA than were higher-performing students.

The current study examined the accuracy of self-

reported HSGPA, based on responses to the 2005–2006

version of the SAT Questionnaire, versus students’

school-reported HSGPA. This study was primarily

undertaken in order to provide updated information

on the relatedness of self-reported and school-reported

HSGPA, compare the results to previous studies, and

offer recommendations on the use of self-reported

HSGPA in future research.

Method

Sample

The students included in the sample were taken from the

national SAT admission validity study sample (for a full

description see Kobrin, Patterson, Shaw, Mattern and

Barbuti, 2008), whereby colleges and universities provided

first-year student performance data for the entering class

of fall 2006 to the College Board to validate the use of the

SAT for admission and placement in higher education.

Participating colleges and universities transmitted

their data to the College Board via the Admitted Class

Evaluation Service™ (ACES™). ACES allows institutions

to design local admission validity studies, and includes

an option of providing either HSGPA or HS rank from

their institutional records or from students’ self-reported

HSGPA or rank from their SAT Questionnaire responses.

Students with valid SAT scores and first-year grade point

averages (FYGPA), and who attended institutions that

chose to supply their own HSGPA (based on transcript

information from their own admission records), were

included in the sample. Students from institutions that

supplied high school rank were not studied because there

were a limited number of such instances. Ultimately,

40,301 students from 32 institutions were included in the

sample for this study.

Materials

SAT Scores

Official SAT scores obtained from the 2006 college-bound

senior cohort database were used in the analyses in order

to determine students’ academic performance subgroups.

This database is composed of the students who have an

SAT score and reported to graduate from high school in

2006. The SAT is composed of three sections — critical

reading, mathematics, and writing — and the score scale

range for each section is 200 to 800. Students’ most recent

scores were used.

SAT Questionnaire (SAT-Q) Responses

Self-reported HSGPA, gender, race/ethnicity, and parental

income and education level were obtained from the SAT-Q,

which is completed at the time the student first registers

for the SAT, and is updated by the student when he or she

chooses to retake the test. The accompanying instructions

on the SAT-Q note that student responses help provide

information about their academic background, activities,

and interests to aid in planning for college and to help

colleges find out more about students. They are also told

3

that the Student Search Service®

1

uses their responses,

provided that they give permission to do so.

School-Reported HSGPA

Students’ school-reported HSGPAs were based on high

school transcript information in their admission records

and were provided by the colleges and universities

they chose to attend. These HSGPAs were reported by

colleges and universities on a variety of scales, which

are shown in Table 1. Students at institutions reporting

HSGPAs on 0.00–4.00, 0.00–4.33, or 0.00–100.00

were included in the sample (k = 32), as HSGPAs on

other scales (e.g., 0.00–160.00) were too difficult to

interpret and translate for this study. Additionally, most

institutions reported HSGPAs on the 0.00–4.00 scale

(k = 22), so the school-reported HSGPA scale used in this

study was 0.00–4.00; HSGPAs between 4.00 and 4.33

were coded as 4.00.

Self-Reported HSGPA

Self-reported HSGPAs were obtained from the SAT-Q

completed by students during SAT registration (see

Figure 1). The self-reported HSGPA is on a 12-point scale

ranging from A+ (97–100) to E or F (below 65). This scale

can be translated to a conventional 12-point numeric

GPA scale ranging from 0.00 to 4.33. To be consistent

with the scale used by most colleges and universities in

the study and to avoid the artificial inflation of students’

overreporting their HSGPA, the self-reported HSGPA

scale was truncated to a 0.00–4.00 or an 11-point scale.

That is, the self-reported HSGPAs that were reported as

4.33 were truncated to 4.00. See Table 2 for self-reported

and school-reported numeric and letter-grade HSGPA

equivalents.

Design and Procedure: Cleaning

and Scaling the HSGPA Data

In order to determine matches and discrepancies between

self-reported HSGPA and school-reported HSGPA, both

measures had to be on the same scale. In keeping

with national research on HSGPA from the 2005 U.S.

Department of Education High School Transcript Study

(Shettle et al., 2007) and because it was the primary

HSGPA scale used by colleges and universities in the

sample (20 percent), it was determined that a 0.00 to

4.00 scale would be the most appropriate for the study.

Therefore, the self-reported HSGPA scale of 0.00–4.33

(5 percent of institutions) was truncated to 0.00 to 4.00

to prevent results from falsely indicating that students

were overreporting their own HSGPAs. In addition,

four institutions with HSGPAs on a 0.00–100.00 scale

were translated to the 0.00–4.00 scale (see Table 2 for

the scale translation details). The 0.00–4.00 scale can be

considered to be an 11-point ordinal scale that includes

the values 0.00, 1.00, 1.33, 1.67, 2.00, 2.33, 2.67, 3.00, 3.33,

3.67 and 4.00.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all academic measures were

computed, as well as correlations between the self-

reported and school-reported HSGPAs for the total

sample and by subgroup. Also, the percentage of students

underreporting, matching and overreporting their own

HSGPAs (self-reported) as compared to their school-

reported HSGPAs was calculated.

Descriptive Statistics

The mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum

for each academic measure examined in this study are

presented in Table 3. Of note, the mean difference in the

self-reported HSGPA minus the school-reported HSGPA

was near zero (–0.04), indicating that on average, students

accurately report their HSGPA with a slight tendency to

underreport (negative value) their HSGPA in comparison

to their school-reported HSGPA. In other words, the mean

school-reported HSGPA (M=3.58, SD=0.43) was slightly

higher than the mean self-reported HSGPA (M=3.54,

SD=0.45). The notion that students are underreporting

or that schools are overreporting HSGPAs is contrary to

prior research, specifically Freeberg’s (1988) study.

Reliability: Correlations Between

Self-Reported and School-

Reported HSGPA

The relationship between self-reported and school-

reported HSGPA for the total group as well as subgroups,

including gender, race/ethnicity, parental education,

parental income and SAT score band, is presented in

Table 4. Specifically, the correlations

2

and percentages of

1. When students take the SAT, for example, the College Board’s Student Search Service (SSS®) allows them the option to give their

names and information to colleges and scholarship programs that are looking for students like them. e following student

information can be sent to colleges and universities: name, address, gender, birth date, high school code, graduation year, ethnic

identication (if provided), intended college major (if provided), and e-mail address (if provided).

2. As the HSGPA scales are ordinal, nonparametric statistics would seem to be the most appropriate for examining correlations

with these data. However, because there are 11 HSGPA categories and a comparison of Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho yielded

extremely similar results, the Pearson correlations (parametric statistics) are reported in the tables.

students underreporting, matching and overreporting

were computed. Furthermore, the percentage of students

whose self-reported HSGPA was within +/– three grades

of their school-reported HSGPA was also computed.

Among all students, the correlation between self-

reported and school-reported HSGPA was 0.74. With

regard to gender, the correlation was slightly lower

for females (r = 0.73) than for males (r = 0.75). For

race/ethnicity, these correlations ranged from 0.65 for

Asian students to 0.76 for white students. For parental

education level, there was a correlation of 0.73 between

self-reported and school-reported HSGPA for students

whose parents have earned less than a bachelor’s degree,

while there was a correlation of 0.75 for students whose

parents have earned higher than a bachelor’s degree. For

parental income level, the correlation for students in the

lowest income bracket was 0.70, while the correlation for

students in the highest income bracket ($100,000+) was

0.77. The correlations by SAT score band show a large

variation with a correlation of 0.62 for the lowest score

band (600–1200) and a correlation of 0.71 for the highest

score band (1810–2400).

Next, the percentage of students whose self-reported

HSGPA exactly matched their school-reported HSGPA

was computed along with the percentage of students

who underreported their HSGPA by three grade points

and those who overreported their HSGPA by three

grade points (see Table 4). If one thinks of the 11-point

HSGPA scale ranging from 0.00 to 4.00, a student

reporting to have a B+/3.33 when their college also

reported their HSGPA as a B+/3.33 is considered to be

an exact match. A student reporting to have a B/3.00 but

who overreported by one grade point from the school

would have a B–/2.67 school-reported HSGPA. If the

same student had underreported by two grade points, he

or she would have an A–/3.67 school-reported HSGPA.

By summing the percentage of students underreporting

and overreporting within plus or minus three grade

points, one can determine a more comprehensive are

HSGPA match (e.g., all grades from A+ through B+

considered to be matching HSGPA).

For the total sample, 52 percent of students reported

an HSGPA that precisely matched their school-reported

HSGPA. Of the remaining 48 percent, 29 percent

underreported their HSGPA and 19 percent overreported

their HSGPA. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of exact

matches, underreporting and overreporting for the

sample. The percentage of students with a self-reported

HSGPA that was within one full grade (e.g., range of

B+ through B–) of the school-reported HSGPA was

89 percent (22 percent + 52 percent + 15 percent).

These findings suggest that when inaccurate reporting

does occur, the inaccuracy tends to be minimal in

magnitude. That is, for students who do not report an

exact match, they are likely to be off by only one grade

point, which translates to a 0.33 on the 0.00 to 4.00

scale. This is in keeping with the mean difference found

between self-reported HSGPA and school-reported

HSGPA (–0.04). The same analyses were conducted by

gender, race/ethnicity, parental education and parental

income subgroups and are also presented in Table 4.

With regard to gender, females more accurately

reported their HSGPA, with 54 percent of females having

an exact match compared to males with a 50 percent

match rate. Interestingly, males and females overreported

at relatively the same rate (20 percent and 19 percent,

respectively) as well as underreported at relatively the

same rate (29 percent and 28 percent, respectively). Using

the more liberal criteria of matching within one grade

level, the match rate increased to 89 percent for males

and 91 percent for females. For race/ethnicity, African

American students had the lowest exact match rate (42

percent), whereas Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander

students had the highest exact match rate (55 percent).

These percentages increased to 85 percent and 90 percent,

respectively, when self-reported and school-reported

HSGPAs were matched within one grade level of each

other. As for parental education and income, the match

rate tended to increase with education and income level.

Finally, the largest discrepancies of match rates occurred

in SAT score band groups. For students in the lowest

SAT score band, their exact match rate was 30 percent

(76 percent matched within +/– one grade) compared to

64 percent for students in the highest SAT score band

(94 percent matched within +/– one grade). That is,

higher-ability students were more than twice as likely

to accurately report their HSGPA. These results led to

an investigation of the match between self-reported and

school-reported HSGPA by students’ self-reported HSGPA

(see Table 5). The darkest shaded diagonal in Table 5

shows the percentage of HSGPAs that exactly match.

The lighter shades indicate the percentage overreporting

and underreporting within one grade by self-reported

HSGPA, with the lower row indicating overreporting and

the higher row indicating underreporting by the student.

The percentage of self-reported HSGPAs that exactly

matched the school-reported HSGPAs steadily decreased

as the school-reported HSGPA decreased, ranging from

a 78 percent match for an A to a 10 percent match for a

C.

3

The number of students reporting to have an HSGPA

equivalent to an A is 13,658 and decreases down to 48

for students reporting to have an HSGPA equivalent to

a C–. The percentage of students overreporting their

HSGPA steadily decreased as the HSGPA decreased, and

the percentage of students underreporting their HSGPA

increased as the HSGPA decreased.

4

3. Self-reported grades with less than 15 students in the group were not reported.

5

To disentangle the effects of accuracy of self-

reported HSGPA as a function of academic ability (SAT)

versus demographic characteristics, the percentage

of students exactly matching, and overreporting and

underreporting their HSGPA by gender, race/ethnicity,

parental education and income level by SAT score band

was computed and is provided in Table 6. Within

all subgroups, there is a consistent increase in the

percentage of HSGPAs that exactly match as the SAT

score band increases. Similar to Table 5, this indicates

that most subgroup differences related to the exact

HSGPA match percentages are linked to prior academic

performance rather than particular racial/ethnic or

parental income group membership, for example.

Discussion

The results of this research show that students are

essentially accurate in reporting their HSGPA. The

uncorrected correlation between self-reported and

school-reported HSGPA was 0.74, which is lower than in

earlier studies but still a strong correlation. Even more

encouraging, when the two measures were examined by

the traditional method of a match rate within one full

grade level (e.g., a self-reported A would be considered

a match to a school-reported A–), there was 89 percent

agreement, indicating that any discrepancies between the

two measures are very small.

In contrast to previous studies, this research found

that when students’ self-reported HSGPAs did not match

the school-reported information, their indication of

HSGPA was more likely to be lower than the school-

reported HSGPA. Previous studies showed more

students overreporting rather than underreporting their

HSGPA (Baird, 1976; Freeberg, 1988; Kuncel et al.,

2005; Maxey & Ormsby, 1971). The reasons for the

increase in underreporting by students could be the

result of numerous influences, including changes in

grading practices such as grade inflation in high schools,

increased confusion in reporting weighted averages and

other methodological factors.

One possible explanation for the increase in the

underreporting of students’ self-reported HSGPA is grade

inflation in U.S. high schools. Widespread grade inflation

in high schools over the past many years has been

well documented and discussed (see Camara, Kimmel,

Scheuneman, and Sawtell, 2003; Woodruff and Ziomek,

2004), with the largest proportional increases at the

higher end of the grade distribution (Camara, 1998;

Ziomek and Svec, 1995). With students actually receiving

higher high school grades, there is less “room” for the

students to overreport their HSGPA or indicate earning

higher HSGPAs than they have actually received. This is

clear when examining Table 5. Sixty-three percent of all

school-reported HSGPAs are at or above an A– (or 3.67).

There has also been an increase in the number

of students enrolled in honors, dual enrollment and

Advanced Placement® (AP®) courses throughout the

country (College Board, 2008), which can lead to some

confusion in the reporting of students’ weighted HSGPAs.

In 1971, Maxey and Ormsby explained that a slight drop in

the correlation between self-reported and school-reported

HSGPA was primarily the result of the introduction of

dual grading systems in the U.S. With increased honors

courses offered to students, there appeared to be confusion

when reporting weighted grades. Although students

are not often aware of their recalculated, or weighted

HSGPAs, colleges and universities are more likely to be

examining and reporting students’ recalculated HSGPAs

that may take into account advanced-level courses or

attendance at more academically competitive high

schools (Rigol, 2003). This certainly leads to a larger

discrepancy between self-reported and school-reported

HSGPA measures — and this discrepancy would likely

result in the school-reported HSGPAs being the higher

of the two.

There are also methodological influences that may

contribute to increased underreporting rather than

overreporting. In this study, there is probably a time

lapse between when the two sources of information

on HSGPA were collected. The students’ self-reported

information was collected at the time of their latest SAT

administration, whereas school-reported information

was collected at the time of their application to college.

Students may take the SAT in March of their junior year

of high school but apply to college in January of their

senior year. The later (school-reported) HSGPA could

be higher due to increased opportunities for growth and

maturity that could contribute to improved grades. It

could also be related to the increased opportunity for

seniors to take elective courses that tend to be more in

line with students’ interests and can sometimes be less

academically demanding. Students are also able to drop

some of their more advanced math and science courses

in their senior year, which could lead to higher HSGPAs.

In addition, the students in this sample had already

been admitted to college. As the results of this study

show, academically stronger students are less likely to

overreport their HSGPAs. Had the sample also included

students who ultimately did not go to college — or

perhaps included students from two-year institutions or

less selective institutions than those in the sample — the

students may have been less likely to underreport their

HSGPAs.

Similar to previous research, there were small

differences between race/ethnicity subgroups and

students of varying income levels, with regard to the

relationship between self-reported and school-reported

6

HSGPA (Freeberg, 1988; Kuncel et al., 2005; Maxey

and Ormsby, 1971; Sawyer et al., 1988). For gender, the

correlations for males and females were quite similar.

With regard to race/ethnicity, white students had higher

correlations between self-reported and school-reported

HSGPA than did nonwhite students. While there was

very little difference in the correlations by parental

education level, there was some difference by parental

income level, with the highest correlation for students in

the highest income category and the lowest correlation

among students in the lowest income category. Rather

than being related to actual wealth, this finding is likely

related to the association between greater social and

financial resources being linked to higher academic

performance that, in turn, is linked to more accurate

reporting of HSGPA. This was supported by the results

provided in Table 6. Students in the lowest SAT score

band had the lowest correlation between self-reported and

school-reported HSGPA among all subgroups analyzed.

For students in the lowest SAT score band, their exact

match rate was 30 percent (76 percent for a match within

+/– one grade) compared to 64 percent for students in the

highest SAT score band (94 percent for a match within

+/– one grade). These findings echo the recent meta-

analysis on the validity of self-reported HSGPA by Kuncel

et al. (2005), whereby higher-ability students reliably self-

reported their HSGPA, while lower-ability students were

much less reliable.

Limitations

There are a few limitations of this study that deserve

mention. Most of these limitations, however, are not

unique to this particular study but are characteristic of

the research in this domain. First, research examining

the comparability of self-reported and school-reported

HSGPA must first ensure that the measures are on the

same scale, which naturally introduces error into the

relationship. First, the researchers had to interpret the

many different school-reported HSGPAs and place them

all on one standard scale (after the college or university

had presumably done the same translation during the

admission process). Second, there is some error in self-

reported HSGPA as students from high schools with

various grading policies and standards must report

their HSGPA on the given SAT Questionnaire scale.

Students may be unsure as to the role of weighting in

their HSGPA and may also be unsure of whether to

report their weighted or unweighted HSGPA on the

SAT Questionnaire. Added instructions to this item or

perhaps the opportunity to write or “bubble” in their

precise HSGPA may ameliorate this issue.

Similarly, the accuracy of the match between self-

reported and school-reported HSGPA is highly reliant

on the operationalization of that grade match. Larger

bands of grades considered to be the same will result

in much higher match rates than exact matches of

self-reported and school-reported HSGPAs. This notion

is particularly important in comparing the results of

prior studies in this domain to each other and to the

current study. In order to be transparent and arm the

reader with the most complete information, this study

presents the results based on various categories of grade

matches. Furthermore, any discrepancies between the

self-reported and school-reported HSGPAs could be due

to temporal differences in the request and receipt of such

information.

Conclusion

This research analyzed the relationship between self-

reported and school-reported HSGPA among a large,

national sample of students. Findings suggest that

students are quite accurate in reporting their HSGPA.

While the correlation between the self-reported and

school-reported HSGPA is lower than the correlations

found in prior research, a strong relationship between

the two measures remains. In contrast to earlier related

studies, students underreported their HSGPA more often

than they overreported it. This shift could be due to a

variety of factors, including changes in grading practices

in high schools, increased student confusion in reporting

weighted averages, variation in recalculations of HSGPA

by colleges and universities, and other methodological

factors that include a time lapse in collection of the two

HSGPAs and a college-going sample.

Finally, this study highlighted the difficulty in

rescaling school-reported HSGPAs for comparison across

colleges, as well as the difficulty that must occur when

rescaling students’ HSGPAs for comparison within an

institution. When receiving thousands of applications

with HSGPAs on a wide variety of scales from students,

enrollment officers have the daunting responsibility

of scientifically and fairly placing these important

and complex admission criteria on the same scale for

comparison. Just as this process introduced error into

the current study, it is likely to introduce error into the

admission process. Future research should focus on ways

to fairly translate and recalculate HSGPAs at various

schools. It should also focus on the most effective ways to

increase the accuracy of students’ self-reported HSGPA.

7

References

Baird, L. L. (1976). Using self-reports to predict student

performance (Research Monograph No. 7). New York: The

College Board.

Camara, W. J. (1998). High school grading policies (College

Board RN-04). New York: The College Board.

Camara, W. J., Kimmel, E., Scheuneman, J., & Sawtell, E. A.

(2003). Whose grades are inflated? (College Board Research

Report No. 2003-04). New York: The College Board.

College Board. (2008). The 4th annual AP report to the nation.

New York: The College Board.

Freeberg, N. E. (1988). Analysis of the revised student descriptive

questionnaire, phase I (College Board Report No. 88-5).

New York: The College Board.

Kobrin, J. L, Patterson, B. F., Shaw, E. J., Mattern, K. D., &

Barbuti, S. M. (2008). Validity of the SAT for predicting first-

year college grade point average (College Board Research

Report No. 2008-5). New York: The College Board.

Kuncel, N. R., Credé, M., & Thomas, L. L. (2005). The validity

of self-reported grade point average, class ranks, and test

scores: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Review

of Educational Research, 75, 63–82.

Maxey, E. J., & Ormsby, V. J. (1971). The accuracy of self-

report information collected on the ACT test battery: High

school grades and items of nonacademic achievement (ACT

Research Report No. 45). Iowa City, IA: The American

College Testing Program.

Rigol, G. W. (2003). Admissions decision-making models: How

U.S. institutions of higher education select undergraduate

students. New York: The College Board.

Sawyer, R., Laing, J., & Houston, M. (1988). Accuracy of self-

reported high school courses and grades of college-bound

students (ACT Research Report 88-1). Iowa City, IA: The

American College Testing Program.

Schiel, J., & Noble, J. (1991). Accuracy of self-reported course

work and grade information of high school sophomores

(ACT Research Report 91-6). Iowa City, IA: The American

College Testing Program.

Shettle, C., Roey, S., Mordica, J., Perkins, R., Nord, C.,

Teodorovic, J., Brown, J., Lyons, M., Averett, C., & Kastberg,

D. (2007). The nation’s report card: America’s high school

graduates (NCES 2007-467). U.S. Department of Education,

National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC:

U.S. Government Printing Office.

Woodruff, D. J., & Ziomek, R. L. (2004). High school grade

inflation from 1991 to 2003 (ACT Research Report 04-4).

Iowa City, IA: The American College Testing Program.

Ziomek, R. L., & Svec, J. C. (1995). High school grades and

achievement: Evidence of grade inflation (ACT Research

Report 95-3). Iowa City, IA: The American College Testing

Program.

8

Table 1

HSGPA Grading Scales Across Higher Education

Institutions in the Study

Scale k % of Sample

Not provided 52 51%

0–1 1 2%

0–4 22 20%

0–4.33 6 5%

0–5 21 19%

0–20 1 0%

0–100 4 3%

0–110 2 1%

0–160 1 0%

Note: Students at institutions on the 0–1, 0–5, 0–20, 0–110 and

0–160 scales were not included in the analyses due to diffi-

culty in interpreting the scale values.

Table 2

Recoding of School- and Self-Reported HSGPA

School- and

Self-Reported

HSGPA

(0.00–100.00;

0.00–4.33)

Matched to

0.00–4.00 Scale

Matched to

Letter Grades

93.00–100.00;

3.671–4.330

4.00 A

90.00–92.99;

3.331–3.670

3.67 A–

87.00–89.99;

3.001–3.330

3.33 B+

83.00–86.99;

2.671–3.000

3.00 B

80.00–82.99;

2.331–2.670

2.67 B–

77.00–79.99;

2.001–2.330

2.33 C+

73.00–76.99;

1.671–2.000

2.00 C

70.00–72.99;

1.331–1.670

1.67 C–

67.00–69.99;

1.001–1.330

1.33 D+

65.00–66.99; 1.000 1.00 D

Below 65.00;

Below 0.999

0.00 E or F

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics for the Academic Measures (N = 40,301)

Academic Measure M SD Min. Max.

Self-Reported HSGPA 3.54 0.45 1.00 4.00

School-Reported HSGPA 3.58 0.43 1.33 4.00

Self-Reported HSGPA Minus School-Reported

HSGPA

–0.04 0.32 –3.00 2.00

SAT Critical Reading 554.86 92.10 200.00 800.00

SAT Mathematics 571.92 92.78 200.00 800.00

SAT Writing 547.99 90.91 200.00 800.00

9

Table 4

Self-Reported Versus School-Reported HSGPA Accuracy: Correlations, Percentage of Exact HSGPA Match,

Underreporting and Overreporting of HSGPA in Grade Steps by Race/Ethnicity, Parental Income, Parental

Education Level and SAT Score Band

Student Underreporting

Exact

Match

Student Overreporting

n r –3 –2 –1 +1 +2 +3

Total Sample 40,301 0.74 1% 5% 22% 52% 15% 3% 1%

Gender

Female 22,073 0.73 1% 5% 22% 54% 15% 3% 1%

Male 18,228 0.75 1% 5% 23% 50% 16% 3% 1%

Race/Ethnicity

American

Indian/

Alaska Native

238 0.73 2% 5% 23% 52% 15% 3% 2%

Asian/

Asian American/

Pacific Islander

4,559 0.65 1% 5% 23% 55% 12% 3% 1%

African

American

2,332 0.71 1% 7% 23% 42% 20% 6% 2%

Hispanic 2,089 0.72 1% 7% 21% 50% 16% 5% 1%

White 27,869 0.76 1% 5% 22% 53% 15% 3% 0%

Other 1,347 0.72 1% 5% 23% 49% 17% 4% 1%

No Response 1,867 0.71 1% 5% 21% 50% 18% 4% 1%

Parental

Education

Less than

Bachelor’s

11,901 0.73 1% 5% 22% 50% 17% 4% 1%

Bachelor’s 12,919 0.76 1% 5% 23% 53% 15% 3% 0%

More than

Bachelor’s

13,275 0.75 1% 5% 23% 54% 14% 3% 0%

No Response 2,206 0.69 1% 5% 22% 49% 17% 5% 1%

Parental Income

Up to $20,000 1,599 0.70 2% 6% 23% 46% 17% 5% 1%

$20,000 to

$60,000

7,557 0.73 1% 5% 21% 52% 15% 4% 1%

$60,000 to

$100,000

9,182 0.75 1% 5% 22% 53% 15% 3% 0%

$100,000 + 8,979 0.77 1% 5% 23% 53% 16% 3% 0%

No Response 12,984 0.74 1% 5% 23% 52% 15% 3% 1%

SAT Score

600–1200 826 0.62 3% 10% 26% 30% 20% 7% 2%

1210–1800 26,596 0.72 1% 6% 24% 47% 17% 4% 1%

1810–2400 12,879 0.71 0% 3% 19% 64% 11% 2% 0%

Note: One grade step is equivalent to the difference in a B– and a B. Two grades steps are equivalent to the difference in a B– and a

B+. Three grade steps are equivalent to the difference in a B– and an A–. Due to rounding, totals may not equal 100 percent. r repre-

sents the correlation between self-reported and school-reported high school GPA.

10

School-Reported HSGPA

Table 5

Accuracy of Self-Reported HSGPA by HSGPA Value

Self-Reported HSGPA

A

(n = 13,658)

A–

(n = 10,214)

B+

(n = 8,066)

B

(n = 5,671)

B–

(n = 1,704)

C+

(n = 675)

C

(n = 261)

C–

(n = 48)

A

(n = 14,825)

78% 32% 8% 3% 1% 2% 3% 2%

A–

(n = 10,547)

17% 45% 34% 14% 4% 2% 3% 4%

B+

(n = 7,795)

4% 17% 39% 35% 16% 7% 4% 8%

B

(n = 4,796)

1% 4% 17% 35% 40% 29% 18% 17%

B–

(n = 1,649)

0% 1% 2% 10% 28% 36% 32% 15%

C+

(n = 550)

0% 0% 1% 2% 9% 19% 28% 29%

C

(n = 126)

0% 0% 0% 0% 2% 5% 10% 17%

Note: HSGPA groups with fewer than 15 students are not reported.

11

Table 6

Percentage of Exactly Matching, Underreporting and Overreporting of HSGPA by Demographic

Characteristics in the SAT Score Band

SAT Score

Band

n

Student

Underreporting %

Exact

Match %

Student

Overreporting %

Gender

Female

600–1200 524 40% 31% 30%

1210–1800 15,065 30% 48% 21%

1810–2400 6,484 21% 68% 12%

Male

600–1200 302 42% 30% 28%

1210–1800 11,531 31% 46% 23%

1810–2400 6,395 25% 60% 15%

Race/Ethnicity

American Indian

or Alaska Native

1210–1800 183 32% 48% 20%

1810–2400 51 20% 65% 16%

Asian, Asian

American or

Pacific Islander

600–1200 78 51% 27% 22%

1210–1800 2,794 32% 50% 17%

1810–2400 1,687 23% 64% 13%

Black

600–1200 185 41% 24% 35%

1210–1800 1,910 30% 42% 28%

1810–2400 237 30% 54% 17%

Hispanic

600–1200 98 38% 31% 32%

1210–1800 1,602 30% 48% 22%

1810–2400 389 22% 62% 16%

White

600–1200 395 41% 34% 26%

1210–1800 18,143 31% 48% 22%

1810–2400 9,331 23% 65% 13%

Other

600–1200 36 25% 28% 47%

1210–1800 895 31% 44% 25%

1810–2400 416 26% 60% 14%

No Response

600–1200 30 37% 30% 33%

1210–1800 1,069 30% 44% 26%

1810–2400 768 24% 59% 17%

Parental

Education

< B.A.

600–1200 459 42% 28% 29%

1210–1800 9,406 29% 47% 23%

1810–2400 2,036 21% 67% 13%

B.A.

600–1200 205 39% 36% 26%

1210–1800 8,620 31% 48% 21%

1810–2400 4,094 23% 65% 13%

> B.A.

600–1200 95 41% 31% 28%

1210–1800 7,151 32% 47% 21%

1810–2400 6,029 24% 63% 14%

No response

600–1200 67 33% 27% 40%

1210–1800 1,419 30% 45% 25%

1810–2400 720 26% 58% 16%

Table 6 continued on next page

12

Table 6

continued

Percentage of Exactly Matching, Underreporting, and Overreporting of HSGPA by Demographic

Characteristics in the SAT Score Band

SAT Score

Band

n

Student

Underreporting %

Exact

Match %

Student

Overreporting %

Parental Income

<$20K

600–1200 122 48% 17% 35%

1210–1800 1,249 31% 46% 23%

1810–2400 228 22% 63% 15%

$20K–60K

600–1200 250 42% 33% 25%

1210–1800 5,598 29% 48% 23%

1810–2400 1,709 21% 69% 11%

$60–100K

600–1200 148 39% 36% 26%

1210–1800 6,332 31% 48% 21%

1810–2400 2,702 22% 67% 12%

>100K

600–1200 85 38% 33% 29%

1210–1800 5,289 32% 47% 21%

1810–2400 3,605 23% 61% 16%

No Response

600–1200 221 38% 29% 33%

1210–1800 8,128 31% 46% 22%

1810–2400 4,635 24% 63% 13%

Note: Groups with fewer than 15 students are not reported.

13

Underreporting OverreportingExact

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

28% 19%52%

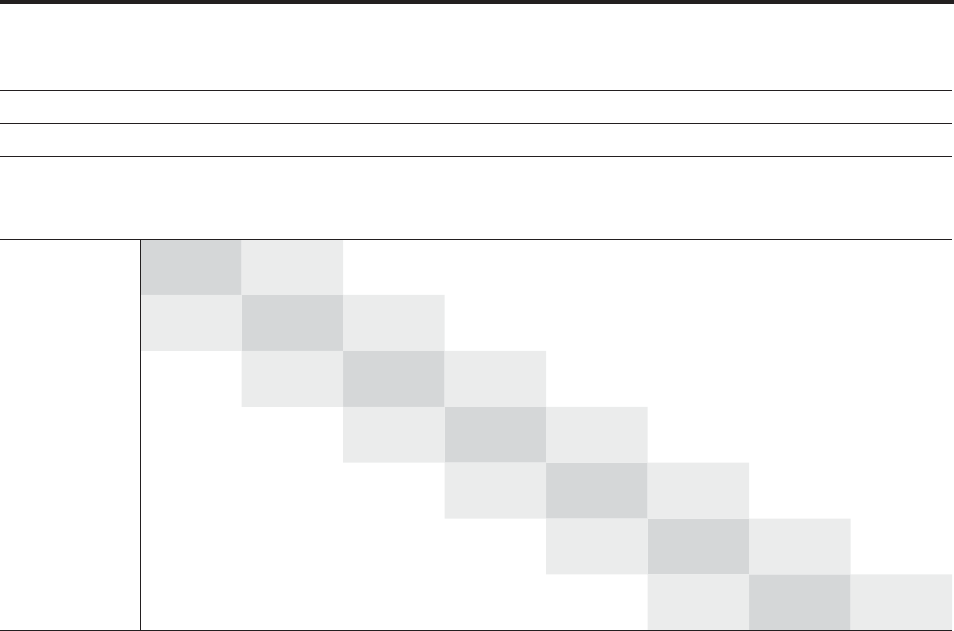

Figure 2. Percentages of students underreporting, exactly matching or overreporting their HSGPA.

The SAT Questionnaire allows you to provide information about your academic background, activities and interests

to help you in planning for college and to help colleges find out more about you. The Student Search Service

®

also

uses this information.

Indicate your cumulative grade point average for all academic subjects in high school.

• A+ (97–100) • C+ (77–79)

• A (93–96) • C (73–76)

• A– (90–92) • C– (70–72)

• B+ (87–89) • D+ (67–69)

• B (83–86) • D (65–66)

• B– (80–82) • E or F (Below 65)

GRADE POINT AVERAGE

Figure 1. Self-Reported HSGPA Item on the SAT Questionnaire (2005–2006).

A+ A A– B+ B– C+ C C– D+ D D– E/F

www.collegeboard.com