Reference Checking in

Reference Checking in

Federal Hiring:

Federal Hiring:

MAKING THE CALL

MAKING THE CALL

A Report to the President and the Congress of the United States

by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

THE CHAIRMAN

U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD

1615 M Street, NW

Washington, DC 20419-0001

September 2005

The President

Pr

esident of the Senate

Speaker of the House of Representatives

Dear Sirs:

In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this Merit Systems

Pr

otection Board report, “Reference Checking in Federal Hiring: Making the Call.”

The Federal Government’s human capital is its most vital asset. It is crucially important that our

employment selection pr

ocedures identify the best applicants to strengthen the Federal workforce with well-

qualified and highly committed employees. Properly conducted reference checks are a key component of a

hiring process that will select the best employees from each pool of applicants. In particular, reference

checking is a necessary supplement to evaluation of resumes and other descriptions of training and

experience. By using reference checks effectively, selecting officials are able to hire applicants with a strong

history of performance, rather than those who may have creatively exaggerated less impressive achievements.

Reference checking also helps Federal employers identify and exclude applicants with a history of

inappropriate workplace behavior.

This report reviews the use of reference checking in public and private sectors, and identifies best practices

which, when follow

ed, increase the contribution reference checking makes to hiring decisions. There is

currently little standardization of Federal reference checking, and little training offered in how to conduct

this process effectively. Agencies can certainly improve in this regard. We also note that there are strong

legal protections for Federal employers who make reference checking inquiries and for former employers who

provide job-related information about applicants. MSPB recommends that agencies improve the quality of

their reference checking practices and check applicant references before making each hiring decision.

I believe you will find this report useful as you consider issues affecting the Federal Government’s ability to

select and maintain a highly qualified workfor

ce.

Respectfully,

Neil A. G. McPhie

Reference Checking in

Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

A REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT AND THE

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE

U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD

U.S. Merit Systems Pr

otection Board

Neil A. G. McPhie, Chairman

Barbara J. Sapin, M

ember

Office of Policy and Evaluation

Director

Steve Nelson

Deputy Director

John Crum, Ph.D.

Project Manager

John M. Ford, Ph.D.

Project Analyst

James J. Tsugawa

T

able of Contents

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .i

Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Why Employers Do Not Check References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Legal Issues Associated With Checking References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Benefits of Reference Checking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Direct Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Long-Term Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

Best Practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Reference Checking Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Information From Applicants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29

Selecting Reference Providers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

Checking the References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

Evaluating the Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36

The Hiring Decision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

Answering the Call: Providing References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Legal Issues for Reference Providers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40

The Role of the Reference Provider . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .44

The Other Side of the Table: Advice for Applicants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .47

Future Developments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

Some Possible Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

Sources of Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51

Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53

Executive Summar

y

R

eference checking is a common and familiar hiring practice. Minimally, a

reference check involves a conversation—usually a phone conversation—

between a potential employer and someone who knows the job applicant.

A properly conducted reference check is not an informal, gossipy exchange of

unsubstantiated opinions about a job applicant. Seven characteristics set reference

checking apart from casual conversation and make it a valid and useful component

of the hiring process.

Properly conducted reference checks are:

1. Job-related. The focus of a reference checking discussion is on an applicant’s

ability to perform the job.

2. Based on observation of work. The information provided by a reference

must be based on experience observing or working with a job applicant.

3. Focused on specifics. The discussion must be focused on particular job-

related information common to all job applicants to ensure fairness. Skillful

probing and comparing of information ensures that the process produces more

than a superficial evaluation.

4. Feasible and efficient. Because reference checking is focused, it can be

conducted quickly. It provides a reasonable return for the small amount of time

needed to do it well.

5. Assessments of the applicant. The information obtained from reference

checking may be used to determine whether an applicant will be offered a job.

Reference checking procedures therefore are assessments subject to employment

regulations, such as the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

and they must conform to accepted professional measurement practice.

6. Legally defensible. It is necessary for reference checks to meet high

professional standards, and reference checkers can meet these standards within

the constraints of the law.

7. Part of the hiring process. The purpose of the reference check is to

inform a decision about hiring. The results need to complement other

assessments used in that process.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

i

Executive Summary

A r

eview of best practices in hiring reveals that reference checking is widely

practiced in both public and private sectors. It is used both to verify information

obtained from job applicants, such as facts about previous employment, and to

assess skills and abilities relevant to the job to be filled. There is marked variation

in the degree to which employers structure and standardize reference checking.

Training in effective reference checking is often not available to those who must

conduct it. Increasing attention to structuring reference checking according to

best practices and shifting responsibility from human resources (HR) personnel to

hiring supervisors has the potential to raise the perceived and actual value of

reference checking.

Employers who do not check references give a variety of reasons. Checking

references may seem too time intensive when long-term benefits are ignored.

Employers may trust the referrals from friends or current employees, while ignoring

risks of perceived favoritism. Some employers want to avoid redundant

assessments, and mistakenly believe that reference checks are always duplicative of

other assessments. And some employers just do not want to risk uncovering

disconfirming evidence about a job applicant to whom they have become

emotionally committed.

Reference checking raises legal concerns as well. It is legal to request information

about an applicant’

s past job performance. Reference checkers in general have a

qualified immunity against charges of invasion of privacy so long as they restrict

their inquiries to job-related issues. Many organizations require applicants to sign a

formal waiver that gives reference checkers permission to discuss on-the-job

behavior with former employers. The Declaration for Federal Employment (OF-

306) form serves this purpose in Federal hiring. Reference checking is occasionally

made less reliable in Federal hiring when an employee is granted a “clean record” as

part of a settlement agreement with the former employer.

Conducting reference checks has a number of advantages. Direct benefits include

making better and more informed hiring decisions, impr

oving job-person match,

improving on self-report assessments of training and experience, demonstrating

fairness and equal treatment of all job applicants, and sending a message about the

high expectations of the employer. Longer term benefits include avoiding the costs

of a bad hire, maintaining employee morale by making quality hires, and gaining

the public’s trust that civil servants take hiring seriously.

Although reference providers are generally willing to disclose factual information

about an applicant’

s employment history, they may need to be persuaded through

skillful questioning to discuss sensitive topics or make evaluative judgments. Many

reference providers have misconceptions about potential liability associated with

providing information about former employees. However, providing reference

information need not be avoided—it can be done within the bounds of legality.

Reference providers should play their role carefully, but need not fear legal

consequences if they follow a fe

w guidelines. They should verify that a reference

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

ii

Executive Summary

checker is legitimate.

They should avoid providing letters of reference because these

are less useful in reference checking. Reference providers can avoid the appearance

or actuality of maliciousness by keeping their comments focused on the applicant’s

job-related behavior. By providing examples and detailed descriptions, reference

providers ensure that their evaluative judgements are firmly grounded in reality.

Job applicants should support reference checking and play an active role in making

connections between reference checkers and reference providers. They should select

reference providers who have observed their work and who are available to

communicate their observations clearly and accurately. Applicants should be candid

about their strengths and weaknesses in the hiring process. Any less-than-flattering

information about the applicant is best communicated to the employer by the

applicant, rather than discovered during reference checking.

Reference checking will likely change in the future. Some anticipated sources of

change are shifts in patterns of business communication and the use of technology

,

innovations in assessment practice, and differences caused by the average length of

employment and probationary employment periods.

Given the state-of-the-art practice and potential of reference

checking as an assessment in Federal hiring, the following

is recommended:

1. Hiring officials should conduct reference checks for each hiring decision.

2. Hiring officials should develop and follow a thoughtful reference checking

strateg

y that is an integral part of the hiring process.

3. Hiring officials should use a consistent reference checking process that

treats all applicants fairly

, obtains valid and useful information, and

follows legal guidelines.

4. Agencies should require applicants to provide appropriate professional

refer

ences and make applicants responsible for ensuring that they can

be contacted.

5. Agencies should review and possibly revise their formal systems of records

so that supervisors may r

eview past performance information when

providing references.

6. Agency human resources personnel should require job applicants to

complete the Declar

ation for Federal Employment (OF-306) form early in

the application process.

7. Agencies should increase standardization of and training in effective

refer

ence checking techniques.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

iii

Executive Summary

8.

The U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) should develop

guidelines to help agency personnel follow appropriate procedures for

checking and providing references.

9. Supervisors and other employees should provide candid and appropriate

reference information.

Reference checking has an important role to play in the Federal hiring process. It

should be more than a formality conducted b

y administrative staff. It should be

more than a casual, unstructured phone conversation between supervisors. It

should certainly not be an illegal and inappropriate exchange of gossip about

unsuspecting applicants. Reference checking can improve the quality of the Federal

workforce by reducing the number of unqualified, unscrupulous, and otherwise

unsuitable applicants whose liabilities escaped detection during the earlier phases of

the hiring process. If reference checking is to reach this potential, it will require

cooperation among Federal hiring officials, applicants for Federal employment, and

reference providers. The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB)

recommends that agency policy makers, human resources professionals, hiring

officials, job applicants, and former supervisors of these applicants appropriately

utilize their roles to make reference checking work.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

iv

Background

M

any aspects of the Federal hiring process seem strange and unfamiliar to

job applicants from the private sector. Most have never encountered

rating schedules, veterans’ preference, multiple posting of job openings

under different hiring authorities, and other oddities of Federal hiring practice.

Some aspects of Federal hiring are more familiar, such as employment tests,

structured interviews, and reference checking. In both public and private sector

hiring, it is common for the employer to contact former supervisors and other

coworkers of job applicants to verify their employment histories and ask questions

that help determine their potential as new hires. This practice can make an

important contribution to the hiring decision.

This report highlights best practices that increase the value of reference checking to

the hiring process. It is argued that the benefits of conducting reference checks

outweigh the risks and potentially negative consequences. To improve the hiring

process, cooperation among job applicants, hiring officials, and reference providers

is recommended.

Reference checking is a common and familiar hiring practice. Minimally, a

refer

ence check involves a conversation—usually a phone conversation—between a

potential employer and someone who knows the job applicant. Reference checking

experts further refine the definition to describe a reference checking process that is

both useful and legal.

1

In doing so, they make it clear that a properly conducted

reference check is not an informal, gossipy exchange of unsubstantiated opinions

about a job applicant.

2

Rather, seven characteristics set reference checking apart

from casual conversation and make it a valid and useful component of the

hiring process.

Properly conducted reference checks are:

1. Job-related. As with a structured interview, the focus of a reference checking

discussion is on an applicant’s ability to perform the job. Legitimate job-related

1

See Edward C. Andler and Darla Herbst, The Complete Reference Checking Handbook (2nd Ed.),

Washington, DC: American Management Association, 2003; and Paul W. Barada and J. Michael

McLaughlin, Reference Checking for Everyone, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

2

Barada offers the following definition: “A reference check is an objective evaluation of a candidate’s past

job performance, based on conversations with people who have actually worked with the candidate within

the last five to seven years.” (Barada, op. cit., p. 2) Similarly, Andler describes the reference check in these

terms: “The reference check is usually carried out by the hiring manager or employment staff and

determines actual competency on the job. This type of check involves an in-depth conversation with

someone who knows or has worked with the candidate.” (p. 156).

A R

eport by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

1

Backgr

ound

topics include performance in past jobs, work habits, job-related competencies,

and appropriateness of past on-the-job behavior. Departures from this focus are

unprofessional at best—and may be counterproductive or even illegal.

3

2. Based on observation of work. The information provided by a reference

must be based on experience observing or working with a job applicant.

Personal references from outside the work context may be biased by the

provider’s relationship with the applicant. Even when personal references

provide candid and well-intentioned information, a characterization from this

perspective may not accurately reflect an applicant’s job performance. Reference

checking is crucially important as a way of obtaining information about a

candidate’s training and experience from a source other than the candidate.

Information from those who have observed the applicant does not suffer from

the biases of self-report and self-evaluation that are present in much of the

training and experience assessments used in Federal hiring.

3. Focused on specifics. A reference checking discussion in which the hiring

official passively hopes that useful information will be volunteered by the

reference provider or emerge by chance will rarely be a good use of anyone’s

time. The discussion must be focused on particular job-related information

common to all job applicants to ensure fairness. Skillful probing and comparing

of information is needed to ensure that the process produces more than a

superficial evaluation of each applicant.

4. Feasible and efficient. Because reference checking is focused, it can be

conducted quickly. Given a reasonable job analysis, developing reference

checking questions should not take a great deal of time. Reference checking is

most efficient when it is the final step in a multiple-hurdle assessment process.

It can be used to evaluate three finalist applicants, each of whom provides three

references, in a few hours of total time. Reference checks can provide a great

return for the small amount of time needed to do them well.

5. Assessments of the applicant. The information obtained from reference

checking has high-stakes implications—applicants may or may not be offered a

job as a result. As assessments, reference checking procedures are subject to

employment regulations, such as the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures,

4

and must conform to accepted professional measurement practice.

5

As an assessment, reference checking must be thoughtfully combined with other

assessments used to hire. It should supplement or complement, not merely

duplicate, other assessments of job qualifications.

3

According to Title 5, U. S. Code, §2302 (b)(10), it is a prohibited personnel practice to discriminate

based on the personal conduct of an employee or applicant, unless such conduct adversely affects the on-the-

job performance of the employee/applicant or others. Criminal convictions are exempted from this

prohibition, and may be considered in employment decisions.

4

Section 60-3, “Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,” 43 FR 38295 (29 C.F.R Part

1607), August 1978.

5

Principles for the Validation and Use of Personnel Selection Procedures (4th Ed.), Bowling Green OH:

Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2003; and Standards for Educational and Psychological

Testing, Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association, 1999.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

2

Backgr

ound

6. Legally defensible. It is not only necessary for reference checks to meet

high professional standards—it is possible for reference checkers to meet these

standards within the constraints of the law. By following the guidelines in this

report, hiring officials checking references can request and obtain information

about job applicants without fear of legal consequences. Reference providers can

share job-related information with the same level of protection.

7. Part of the hiring process. The guiding purpose of the reference check is

to inform a decision about hiring. This cannot happen if it is performed too

late in the hiring process to affect the outcome. Nor can it happen if there is no

formal way to integrate the results of the reference check into the hiring process.

It is important to distinguish reference checks from two similar hiring activities that

are bey

ond the scope of this report.

Records checks may also be job-related and play a r

ole in employment decisions,

but they involve straightforward fact gathering from official document sources that

may be far removed from the applicant’s former work environment. They do not

necessarily include probing of the information obtained and may not yield

sufficient information to substantially influence an employment decision. Records

checks can often be safely delegated to administrative or HR personnel who need

not have experience with the job being filled.

Useful records-checking procedures include verifying the dates of employment, job

titles, salary histor

y, and other information from an applicant’s resume. Some of

this information can be sought during a reference check, but this should not be the

primary focus. Depending on the particular position being filled, employers may

be required to conduct criminal records checks (sometimes called “court checks”),

verify citizenship status or otherwise determine eligibility for employment, or verify

that applicants hold necessary licenses or credentials. Some records checks create

obligations for employers who conduct them. For example, if an employer obtains

credit information from credit reporting organizations, the Fair Credit Reporting

Act requires that this information be shared with applicants and that they be given

an opportunity to correct or respond to any negative findings. In addition,

employers are obligated to keep such information confidential and not share it with

third parties.

6

The importance of verifying educational credentials has recently been highlighted in

the Federal sector by public exposure of several agency officials who lack the

educational qualifications claimed on their resumes. Verification of college degrees,

transcripts, and other pertinent records is necessary given the negative impact on

agency performance and credibility when applicants falsify their way into positions

of public trust. This verification can be accomplished in a straightforward manner

by contacting the records office in each degree-granting institution. It is also

6

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) is found in Title 15 of the U.S. Code, §1681. See

www.ftc.gov/os/statutes/fcra.htm.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

3

Backgr

ound

prudent to verify the legitimacy of the granting educational institution as well as the

individual claims of an applicant.

7

Background investigations are more comprehensive than reference checks, and

involve scrutiny not only of applicants’ work history, but also details about their

friends, family, professional associations, financial transactions, and personal habits.

These investigations play an important role in selecting employees for positions of

high trust. The focus is on the trustworthiness and integrity of applicants, as

evidenced by their behavior and relationships with others over a long period of

time. The investigations are performed by specialists trained to probe and analyze a

great deal of information about each applicant.

8

In contrast, reference checks are

conducted with a sample of former coworkers by hiring officials. Reference checks

focus on job-related skills and behavior rather than larger issues of character

or suitability.

One additional perspective on reference checking is in order. Like rating schedules,

evaluation of r

esumes, and numerous other assessments, reference checking focuses

primarily on applicants’ past behavior and accomplishments. It relies on the

behavioral consistency principle—that the most reliable predictor of future

behavior, such as job performance, is past behavior. This principle has a long and

productive history in employee selection. It can be a strong basis for hiring

decisions when an applicant’s past work settings and responsibilities are similar to

those expected in the future.

9

Reference checking verifies an applicant’s description

of past experience and allows the reference checker to evaluate how closely this

experience matches the requirements of the job.

7

See, for example, “Purchases of Degrees from Diploma Mills,” U.S. General Accounting Office, GAO-

03-269R, Washington, DC, November 2002; and “Diploma Mills: Federal Employees Have Obtained

Degrees from Diploma Mills and Other Unaccredited Schools, Some at Government Expense,” U.S.

General Accounting Office, GAO-04-771T, Washington, DC, May 2004. See also the resources for

checking the accreditation of educational institutions on the Department of Education Web site

(www.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/).

8

The specific requirements for Federal background investigations are contained in 5 C.F.R. Part 731.

9

See Frank L. Schmidt, J. R. Caplan, Stephen Bemis, R. Decuir, L. Dunn, and L. Antone, “The

Behavioral Consistency Method of Unassembled Examining,” U.S. Office of Personnel Management,

Personnel Research and Development Center, Washington, DC, 1979. When the past and anticipated

future jobs are less similar, or when a candidate has experienced significant personal development or other

change, the behavioral consistency perspective has less value. In these circumstances, assessments that

measure candidate ability directly, or future-oriented assessments, such as situational judgment tests, should

be given greater weight in a hiring decision.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

4

Reference Checking as an

Employment Practice

A

n examination of current employment practice reveals that reference

checking is widely accepted. However, there is considerable variation in

what information is requested from reference providers, the quality of

information they actually provide, and how employers use this information.

Reference checking among Federal employers, as will be shown later in this section,

may become more standardized in the future due to greater emphasis by the Office

of Personnel Management (OPM). An overview of reference checking in both

public and private sectors follows.

Widely Practiced. Checking references is a widespread, but by no means

universal, hiring practice. Professional reference checking firms indicate that

roughly half of employers perform some form of reference checking as a routine

part of the hiring process.

10

Interviews conducted by the Corporate Leadership

Council (CLC) revealed that five of the six private sector companies they studied

conduct reference checks as a regular step in hiring.

11

A recent regional staffing

survey found that reference checking was the most commonly used (85 percent)

pre-employment screening procedure.

12

Surveys of human resources professionals

by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) indicate that just over

half (52 percent) of employers have a formal policy that governs the reference

checking process, and fewer than half (38 percent) have a clear, written policy.

13

As

might be expected, most reference checking (85 percent) is done by phone.

14

Employers tend to check references more often when hiring managerial or

professional-level employees and less often when hiring administrative or technical

employees.

15

There is considerably less reference checking for part-time or

10

Andler, op. cit.; Barada, op. cit.

11

“Trends in Reference Checks for Professional-Level Employees,” Washington, DC: Corporate Leadership

Council, 2004.

12

“16th Annual Thomas Staffing Survey Results,” Irvine, CA: Venturi Staffing Partners, 2001.

Downloaded from www.thomas-staffing.com on July 5, 2004.

13

SHRM has conducted two recent surveys of human resource professionals about reference checking

policies and practices in their organizations. The first report (SHRM Reference Checking Survey, Alexandria,

VA: Society for Human Resource Management, 1998) is based on 854 responses (32 percent) to surveys faxed

to 2,640 randomly selected SHRM members in July 1998. The second report (Mary Elizabeth Burke,

2004 Reference and Background Checking Survey Report, Alexandria, VA: Society for Human Resource

Management, 2004) is based on 345 responses (18 percent) to surveys emailed to 1,926 SHRM members.

While participants reported on reference checking in a variety of organizations across the United States, only

a small percentage of the participants (5 percent in 1998, 6 percent in 2004) worked in local, State, or

Federal agencies. These were primarily private sector surveys.

14

SHRM 1998, op. cit.

15

Barada, op. cit.; SHRM 2004, op. cit.

A R

eport by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

5

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

temporary hires than for full-time positions. This pattern may be due to the greater

perceived cost of making a “bad hire” when hiring permanent, higher salaried

employees. It may also be due to the, presumably, more highly developed

professional and social networks among professional employees, which provide a

greater number of potential contacts from whom to obtain information. There is

also some indication that organizations check references less often when qualified

applicants are scarce and positions are harder to fill. Clearly, there is a great deal of

variation among organizations in specific reference checking policies and practices.

Assess Applicant Integrity. Many organizations use reference checks to assess

applicant integrity. Nevertheless, organizations often differ in the kind of

information they expect from reference checks. A scan of the popular business and

HR literature reveals that reference checks are frequently used to identify deliberate

exaggerations and outright misrepresentations of experience and work history. The

readers of this literature will find case studies of individuals hired into positions of

great responsibility and trust who misuse resources, make bad decisions, and

generally wreak havoc within their employing organizations —unfortunate

consequences that might have been avoided had the employer “done its

homework.” While research has shown that measures of honesty and integrity can

be useful for pre-employment screening purposes, reference checks can provide a

less resource-intensive proxy for these formal integrity tests.

16

Employers implement this “integrity test by proxy” by collecting information from

applicants about former employers, length of employment, job titles,

responsibilities, salary, and other verifiable details. The employers then contact

reference providers and ask them to verify this information. This allows employers

to identify applicants who have been dishonest in their application. Many

employers believe that such deception is an indication of the applicant’s likelihood

of being dishonest as a future employee. Consequently, they will remove an

applicant from consideration for lying on a job application or resume.

17

Some will

also remove an employee if this behavior comes to light after hiring.

While this strategy clearly identifies some dishonest applicants, less is known about

those who slip through. C

rafty applicants who exaggerate or embellish their work

histories, or who provide carefully coached “personal” references, may still be

successful in their deceptions when reference checking is not done carefully.

Assess Other Competencies. Reference checks are also used to assess job-

related competencies not adequately assessed in other ways. The competencies

assessed through reference checks can range from highly technical competencies

specific to an applicant’s former job responsibilities to more general competencies

common to all work environments. Reference providers are often requested to

16

For a recent review, see Iain Coyne and Dave Bartram, “Assessing the Effectiveness of Integrity Tests: A

Review,” International Journal of Testing, vol 2, no 1, pp. 15–34.

17

SHRM 1998 research cited previously found that 90 percent of employers who check employment

history have found falsification by applicants. The most frequently falsified information is length of

employment, salary, and job title. As a result, most (96 percent) of the organizations SHRM surveyed state

on job applications that any falsification is grounds for removal from consideration. The 2004 survey found

a similar pattern.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

6

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

evaluate applicants’ abilities to communicate, work on a team, and get along with

others in the workplace.

18

Most employers use this information as a check or

additional perspective on their impressions of these abilities from applicant

interviews and application materials.

Often, when there is little formalization of the information obtained from reference

pro

viders about an applicant’s proficiency level, information obtained in this

manner is treated as confirming or disconfirming information from other parts of

the assessment process in an informal “pass or fail” manner. Some employers

acknowledge this informality by describing reference checking as part of a “sniff

test” intended to turn up anything missed by formal assessment.

Perceived Value Varies. Although as discussed earlier, reference checking is

very common in the private sector, there is some variation in how much the

information obtained from reference checking is valued. For example, CLC reports

that some organizations that check references are satisfied with the information they

obtain, but give it little weight in the hiring decision.

19

Some differences of opinion about the value of reference checking are related to the

type of information that different employers try to obtain. In a 1998 survey,

SHRM found that employers are highly satisfied (91 percent) with results when

they inquire about factual matters such as work history. They are less satisfied (45

percent) with information that involves some judgment or opinion, such as whether

a previous employee would be rehired. Employers also report low satisfaction with

information obtained about more complex characteristics such as job qualifications

(30 percent), interpersonal skills (19 percent), and personality characteristics (17

percent). Finally, employers report quite low satisfaction (30 percent) with

information obtained when asking about an applicant’s violent or bizarre behavior

in the former work setting.

Reference checking, then, as it is often practiced, is considered effective to verify

facts, less so to obtain judgments and sensitive information or as an alternativ

e to

direct assessment for job-related competencies. A comparison of the 1998 and

2004 SHRM survey findings reveals a greater tendency in recent years for reference

checkers to focus on verifying facts than to address more complex issues. But is this

an inherent limitation of reference checking or just the perception of these reference

checkers? Before concluding the former, two additional issues should be

considered.

First, there seems to be variation in the quality of reference checking procedure.

SHRM’s 2004 sur

vey found that 81 percent of organizations that do reference

checking employ standardized questions. While this level of standardization is

commendable, it does mean that one-fifth of the organizations surveyed do not

have a structured questioning process. Without standardization of core reference

checking questions, it becomes a more difficult and more subjective task to compare

information obtained from different reference providers. Of greater concern is the

18

SHRM 1998, op. cit.; SHRM 2004, op. cit.

19

“Trends in Reference Checks for Professional-Level Employees,” op. cit.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

7

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

fact that only half of reference checking organizations offer their reference checkers

some kind of training in the process.

20

Under conditions of low standardization and

training, reference checkers might well be more successful in eliciting simple facts

from reference providers than in obtaining more complex or sensitive information.

The second issue concerns who conducts the reference checks. SHRM has

consistently found that many organizations delegate refer

ence checking to HR

personnel.

21

Survey research conducted with human resources specialists who check

references has found that many of these individuals do not believe references

provide credible information.

22

This perception of limited usefulness may result in

reference checking being given a low priority. When reference checking is a low

priority, it may not be done, or may be done in a perfunctory and ineffective

manner. Unstructured, inconsistent, and unreflective reference checks may not

produce useful information. To practitioners who are unfamiliar with best

practices, this poor return may seem intrinsic to reference checking as a method.

Agency Reference Checking Also Varies. In the Federal employment

arena, as in the workplace generally, there is also considerable variation among

agencies in reference checking practice. OPM, the Federal Government’s central

human resources authority, provides little direct guidance on the topic of reference

checking. The Delegated Examining Operations Handbook

23

advises agencies to

verify information provided on the job application or resume, but does not specify

how this should be done. OPM’s Strategic Human Resources Policy group

reinforces the status of reference checking as an assessment and emphasizes agency

responsibility to use valid assessments, but currently provides no detailed guidance

for best practices in checking references.

24

MSPB gathered information about reference checking by Federal employers in a

recent governmentwide survey.

25

Results indicated that most (76.5 percent)

supervisors who had hired a professional or administrative employee included

reference checking as a component of the hiring process. Reference checks were

20

SHRM 2004, op. cit., found that 52 percent of organizations surveyed offer reference checkers training

in “detecting red flags” and only 44 percent offered general training in conducting effective reference checks.

21

SHRM 1998, op. cit., reports that 67 percent of surveyed organizations delegate reference checking to

HR personnel. SHRM found that 15 percent of employers contracted reference checking to outside

contractors and only 14 percent had reference checks conducted by the individual who would manage the

candidate in the new job. This trend persisted in 2004 (SHRM 2004, op. cit), with 61 percent of reference

checks conducted by HR personnel, 17 percent by managers, and 17 percent by outside contractors.

22

“Trends in Reference Checks for Professional-Level Employees,” op. cit.; Lawrence S. Kleiman and

Charles S. White. “Opinions of Human Resource Professionals on Candor of Reference-Givers,”

Psychological Reports, vol 74, no 1, pp. 345–346.

23

Delegated Examining Operations Handbook, Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Personnel Management

(OPM), 2003.

24

Some agency personnel misunderstand the distinction between reference checking and background

investigation and as a result contact OPM’s investigations unit, which does not provide official guidance to

agencies looking to improve their reference checking practice.

25

For a description of this governmentwide survey, see The Federal Workforce for the 21st Century: Results of

the Merit Principles Survey 2000, Washington, DC: U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, September 2003.

The results reported here are from a subset of 311 Federal managers with recent Federal hiring experience.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

8

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

used along with other assessment methods, most often with evaluation of

application materials, personal recommendations, level of education, and

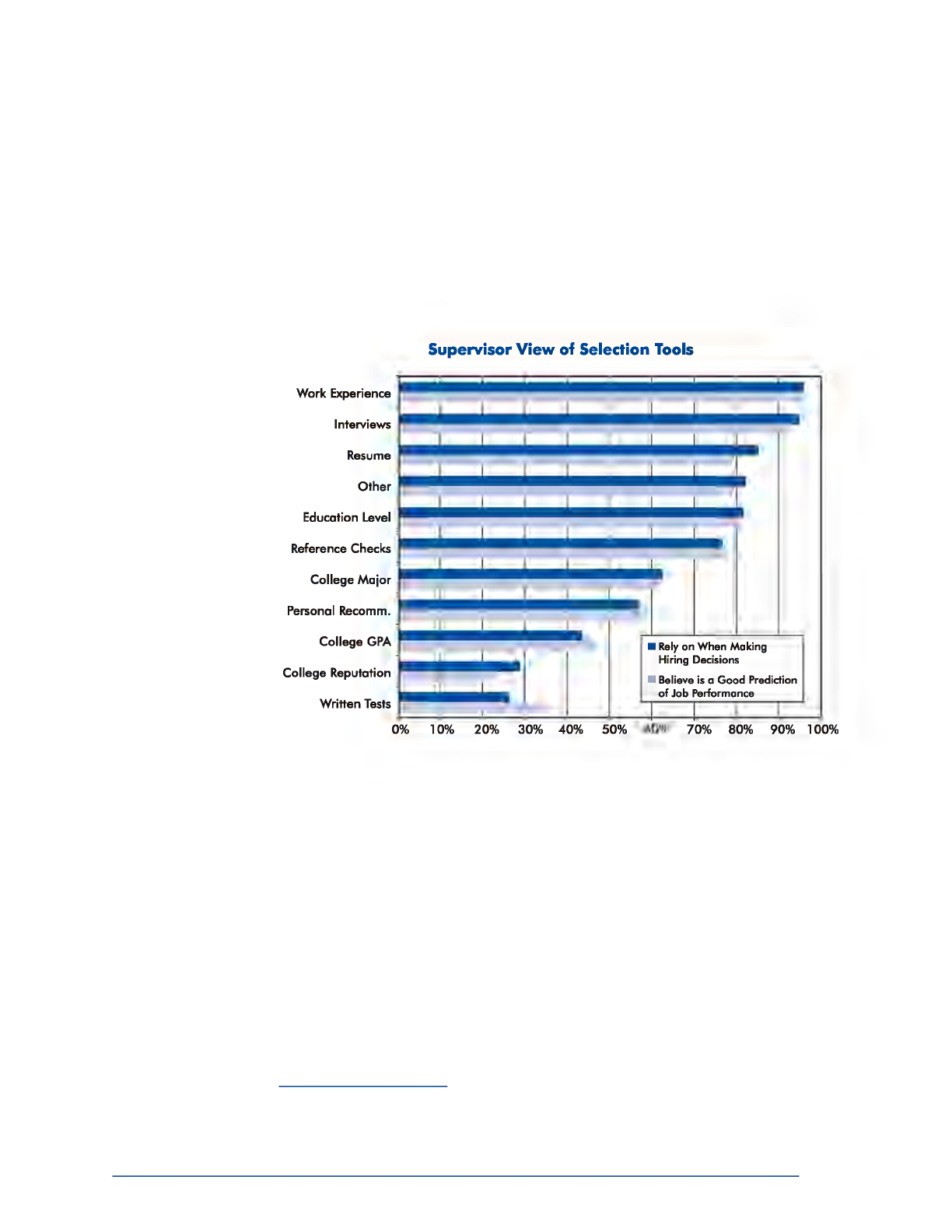

unspecified “other” assessments. The majority of supervisors (77.6 percent) believe

that reference checking predicts job performance to either a very great or moderate

extent. A greater number of managers find credibility in the predictive utility of

prior work experience (95.7 percent) and employment interviews (92.6 percent).

Reference checks are viewed as valuable predictors of job performance more often

than personal recommendations, college grade point average, college major, or

written tests. Federal managers see reference checking as having about the same

predictive value as level of education.

To better understand how agencies use reference checking, MSPB researchers

discussed its role in hiring with managers and human resources specialists from six

Federal agencies.

26

Discussions revealed variation in practice among the agencies

comparable to that reported in the private sector. Some agencies expect human

resources specialists to check references, while others leave reference checking to the

discretion of hiring officials. Some agencies provide reference checking training if it

is requested, but no agency personnel reported any standardized procedure followed

in their agency. One agency devotes a small section of its supervisor training

manual to reference checking, but the official who drew attention to this section

lamented that this topic received much less attention than other supervisory

responsibilities.

26

This was not a formally constructed sample. The goal was to examine the range of reference checking

practices in Federal agencies by talking with practitioners in several very different work contexts.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

9

Work

Experience

Interviews

Resume

Other

Education Level

Reference Checks

College

Major

Personal Recomm.

College GPA

College Reputation

Written

Tests

Supervisor

View

of Selection Tools

•

Rely

on When Making

Hiring Decisions

Believe is a Good Prediction

of

Job Performance

0%

1

0%

20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

The content of reference checking inquiries varied across agencies as well as within

agencies. Whereas some personnel follow a strict practice of only verifying

information provided in the job application, others address job performance and

qualifications more broadly, asking reference providers to evaluate applicants’

communication or interpersonal skills. Several reported that their agency had

recently “caught” applicants who provided false information on job applications.

They reported greater attention to reference checking as a result of these incidents.

Most saw reference checking as useful, but none thought it provided better

information than interviews, formal testing, or other formal assessments used in

their agencies. Reference checking was universally regarded as a last step in hiring

that had some chance of identifying an unqualified or dishonest applicant.

All agency personnel contacted were well aware that reference checking inquiries

must be job-related to remain within legal bounds. Several provided detailed

explanations of general employment interviewing techniques, including the

inappropriateness of discussing applicant gender, ethnicity, religion, or other private

matters. Although most reported some concern about legal risks of reference

checking, few had personally encountered problems or knew of any problems

within their respective agencies. Several pointed to the HR literature as the source

of their concerns. This recurring concern for legal consequences, despite little

evidence of any such consequences, matches what is reported from the private

sector.

27

This concern will be discussed further when the risks and benefits of

checking references are reviewed.

Growing Emphasis in Federal Hiring. Reference checking practice in the

Federal sector may be changing. OPM has issued a “45-Day Hiring Model”

designed to accelerate the hiring practice and allow agencies to meet staffing needs

quickly.

28

Agencies are expected to use this model effectively in order to receive an

acceptable (“green”) score for their performance on the President’s Management

Agenda.

29

OPM has included reference checking as one of the eight recommended

hiring actions in this model.

It remains to be seen what long-term effects this guidance will have. Is the 3-to-5-

day time frame recommended b

y OPM for checking references sufficient? Will

agencies follow OPM’s recommendation to check references, or will they accelerate

the hiring process further by skipping this step? Will agencies conduct reference

checks with appropriate care and use the resulting information responsibly? While

the effects on future practice are yet unclear, OPM’s emphasis on reference checking

is likely to encourage its use, as well as increase the discussion of best reference

checking practices in Federal hiring.

27

SHRM 1998, op. cit.; SHRM 2004, op. cit.

28

Kay Coles James, “The 45-Day Hiring Model,” Memorandum for Heads of Departments and Agencies,

Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Personnel Management, May 6, 2004.

29

“The President’s Management Agenda,” Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, Office of

Management and Budget, 2002, www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2002/mgmt.pdf.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

10

Reference Checking as an Employment Practice

Realizing the Potential. Clearly the quality of reference checking varies in

both private and public sectors. It is difficult to determine the potential of

reference checking as a hiring practice when little distinction is made between

standardized, well-designed reference checks conducted by trained supervisors who

are familiar with the position being filled and informal, unstructured reference

checks conducted reluctantly by untrained and disinterested HR personnel.

Employment interviews once suffered from an uncertain reputation as assessments.

It was not until practitioners and researchers distinguished between unstructured

interviews and interviews structured according to best practices that the strengths of

structured interviews became apparent.

30

Similarly, the strengths of properly

conducted reference checks will become more apparent when they are distinguished

from less formal efforts.

30

The Federal Selection Interview: Unrealized Potential, Washington, DC: U.S. Merit Systems Protection

Board, February 2003.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

11

Costs and Risks of

Reference Checking

C

hecking references is a straightforward process that requires minimal time

from hiring officials and much less training, organizational support, and

applicant cooperation than many other hiring practices. Many employers,

applicants, and reference providers endorse it. Some hiring officials do not perform

reference checks, however. Reluctance to check references stems primarily from

resource constraints in the operational environment of the hiring organization.

Legal concerns also emerge from regulations and agency policy governing applicant

privacy and appropriate dissemination of workplace information.

Why Employers Do Not Check References

Lack of Time. Checking references may seem like an unnecessary step in the

hiring process. Hiring officials and their employees are busy and have other

demands on their time. By the time references are checked, it is typically late in the

hiring process. An employer has narrowed the original pool of applicants to a small

number of seemingly superior finalists. It may seem redundant to check references

when other assessments have already been used.

This is a valid concern, but managers must consider not just costs but the cost-

benefit tradeoff of conducting reference checks. A few phone discussions for a

small, final set of job candidates require very little time. The potential benefit of

uncovering useful information is high relative to this small cost.

Trusted Referral. Reference checking may seem unnecessary if a job applicant

has been referred or endorsed by a trusted colleague of the hiring official. This

conclusion can be particularly tempting when the recommending source is a high-

performing current employee. Experience has shown that this can increase the

chances that the applicant will be another high-performing employee.

31

However, reference checking may still be useful in this situation for a number of

reasons. The hiring official needs to confirm any such judgment. In order to avoid

a situation that might appear to involve some sort of favoritism, the selecting

official should make an extra effort to confirm that the information received from

trusted sources is accurate. It is important to avoid even the appearance of

31

See, for example, Emilio J. Castilla, “Social Networks and Employee Performance in a Call Center,”

American Journal of Sociology, vol. 110, no. 5, pp. 1243–1283.

A R

eport by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

13

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

favoritism or unfair preference. This is a central concern in public sector

employment, where prohibited personnel practices formally forbid favoritism.

32

Reliance on a personal connection may create additional awkwardness when new

hires do not work out and must be removed during the probationary period—and

charges of favoritism are more likely.

Not for Certain Types of Employee. Some employers may avoid checking

references for professional or managerial employees because they believe it is

insulting or that people at this level should not be subjected to this kind of scrutiny.

However, experience has shown that people hired at all levels commit dishonest acts

or may lack key competencies needed to perform in a specific job. The cost of a

bad hire is multiplied at levels of greater responsibility not only due to higher salary

costs, but also to the greater potential damage of poor or marginal performance.

Conversely, some employers believe that applicants for lower paid positions should

not be subjected to refer

ence checks. They reason that it is “not worth it” for this

level of employee. This is the same rationale behind the low incidence of reference

checking for temporary employees. This is shortsighted. In highly interconnected

and team-oriented environments, all employees have important roles to play. Less-

than-satisfactory performance as well as dishonesty in any employee has a high cost,

not only in wasted time and resources, but also to the reputation of the employer.

Redundant Assessment. Some particular reference checking questions may

indeed be unnecessary if the important job-related qualifications have been assessed

by other means. Two questions should be asked before dispensing with reference

checks, however. First, do the other methods have high validity to assess these

competencies? Many assessment methods have demonstrated generally greater

validity than reference checks.

33

Even so, the validity of any assessment method in

practice can be greatly reduced by poor implementation or mismatch with the

competencies being assessed. Reference checks may provide much better

information than other assessments as they are actually implemented. They may

also serve as a way to improve on these assessments by helping hiring officials to

decide between similarly rated applicants.

Second, are the assessments credible? Hiring officials should carefully consider how

other assessments depend on “self-r

eports,” or information supplied about the job

applicant by the job applicant. Resumes, rating schedules, and other self-reports of

training and experience may be subjected to rigorous expert scrutiny and formal

evaluation processes. It can still be difficult to distinguish between well-

32

Title 5, U. S. Code, §2301, states that hiring officials should not solicit or consider employment

recommendations based on factors other than personal knowledge or records of job-related abilities or

characteristics.

33

For a discussion of some validity issues associated with checking references, see Michael G. Aamodt,

Mark S. Nagy, and Naceema Thompson, “Employment references: Who are we talking about?” paper

presented at the annual meeting of the International Personnel Management Association Assessment

Council, June 1998. For a discussion of the comparative validity of different assessment methods, see Frank

L. Schmidt and John. E. Hunter, “The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology:

Practical and theor

etical implications of 85 years of research findings,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 124, no. 2,

pp. 262–274.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

14

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

documented stellar per

formance and a “good story” cribbed from the

accomplishments of others. Rather than solving this problem, automated staffing

systems can make it worse by creating a false sense of security about the

“objectivity” of self-report data once they reside in a database.

34

The problem of unreliability in self-report assessments has a straightforward

solution: verification using sources other than the applicant. Reference checking is

one approach to such verification. Records checks and a second “hurdle” of direct

assessments with applicants are variations of the same strategy. Nevertheless,

reference checks are less expensive than most direct assessments and, unlike records

checks, allow probing as additional information is uncovered. They are important

components of any hiring process that relies on self-reported training and

experience data.

Fear of Bad News. Although it is not usually advanced as a deliberate rationale

for omitting a reference check, sometimes hiring officials just may not want to risk

hearing bad news. A hiring official may become convinced during the decision

process that a future star employee is within reach. (“It has taken so long to find a

good prospect. Why raise any issues that could delay or derail this hire?”) This fear

can lead to delaying or avoiding reference checking, while emphasizing positive

information already identified about the applicant. Even when references are

checked, reference checkers may avoid pursuing any lines of questioning that call

their impression of applicants into question.

35

The inadvisability of avoiding

potentially bad news is plain—this is not a good reason to leave references

unchecked. Further, hiring officials should trust their intuition if they realize that

they “fear” bad news about a particular applicant. This impression may come from

information about the applicant that does not “add up.” Reference checking is the

appropriate method to resolve this type of uncertainty.

Fear of Legal Consequences. Some private sector employers, and some

agency hiring officials as well, worry about legal repercussions when they inquire

into a prospective employee’s background. Some incorrectly believe that it is illegal

to discuss employee performance with an employee of another organization. As a

result, some hiring officials may neglect reference checking, or perform it in a

perfunctory manner, asking only “softball” questions about inconsequential aspects

of the applicant’s former employment.

Although there are some legal issues, much of this fear is unwarranted. So long as

refer

ence checkers focus their inquiries on job-related issues and treat all applicants

equitably, reference checking is a legally defensible activity. The next section

reviews the key legal considerations associated with reference checking.

34

Identifying Talent through Technology: Automated Hiring Systems in Federal Agencies, Washington, DC:

U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, August 2004.

35

This so-called verification bias has been identified and formally studied in several different types of

decision processes. The general recommendation to counteract it is to actively seek information that is

potentially disconfirming. For an overview of the verification bias, see P. C. Wason and P. N. Johnson-Laird,

Psychology of Reasoning: Structure and Content, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

15

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

Legal Issues Associated With Checking References

There are four primary legal concerns associated with reference checks. The first

involves misconception about the legal risks of checking references. Organizations

that check references must also be concerned about invasion of an applicant’s

privacy in the information they request. An additional concern is the possibility of

negligent hiring accusations when employers do not take sufficient care to check an

applicant’s background. Finally, “clean record” settlement agreements increase the

possibility that reference checks of former Federal employees may be ineffective in

determining the true abilities of that employee.

Misconceptions. Reference checkers may be hampered by incorrect beliefs held

by agency officials, potential reference providers, and others. A recurring

misconception among those asked about reference checking is that discussing

performance or job-related behavior of an employee is not legal. It is certainly

possible to conduct reference checking in an irresponsible manner that exposes an

employer, or agent thereof, to claims of discrimination or allegations that the

reference checking resulted in damage to an applicant’s privacy or reputation. As a

general rule, actionable legal claims result from poor practice—they are not

inherent in reference checking any more than libel is inherent in newspaper

publishing. The key is responsible practice.

More detailed recommendations for productive and defensible reference checking

practice will be revie

wed in a following section. It suffices here to outline the

general guidelines for reference checking. First, all questions asked about applicants

should relate to the requirements of the job and to employee performance and

conduct in their previous job. Second, reference checkers should avoid asking

about employee behavior outside the workplace, particularly about religious

practices or other private matters.

Invasion of Applicant Privacy. Concerns about privacy stem from a long

history of legal interpretation of the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

36

It is now

clear that American citizens enjoy a constitutionally grounded “right to privacy.”

The right to privacy has been enhanced further by the passage of statutes such as

the Privacy Act of 1974. Violation of this right can provoke litigation and result in

civil penalties.

However, the right to privacy is not absolute. Employment laws recognize that

employ

ers have special needs to access work history information.

37

Past and

potential employers have generally been granted a “qualified immunity” to discuss

the employment-related performance and behavior of employees with each other.

38

This immunity means that employment-related questions about an applicant’s

36

See, for example, Griswold v. State of Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

37

Title 5 U.S. Code §1302, 3301.

38

Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982). For a recent review, see Markita D. Cooper, “Job Reference

Immunity Statutes: Prevalent But Irrelevant,” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 11, no. 1, pp.

1–68, 2001.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

16

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

behavior may, as a general rule, be asked and answered with minimal risk of legal

liability so long as an applicant’s rights are not knowingly violated.

39

Applicant Waivers. Some private sector employers introduce an additional

level of protection against invasion of privacy claims. They require job applicants to

sign a waiver that does the following:

1. Specifically authorizes the potential employer to contact references to discuss

an employ

ee’s competence, performance, and suitability;

40

2. Affirms that all information in application materials is accurate; and

3. Releases the employer and reference providers from liability resulting from

appropriate r

eference checking discussions.

Many waivers provide protection for applicants as well by outlining the reference

checking procedur

e and the general type of questions that will be asked.

A waiver requirement may seem to unnecessarily duplicate protection already

present in the law

. Applicants grant an implied waiver by applying for a job when

reference checking is an announced part of the hiring process. However, not only is

the express written waiver stronger legal protection, it has additional advantages.

First, it may convince some applicants not to risk misrepresenting themselves.

Second, it may reduce the costs an employer could incur from defending its right to

check references. A poorly informed applicant might challenge a reference checking

procedure unsuccessfully, but still require the employer to expend resources in

defense. This is less likely to occur when the applicant has formally acknowledged

the employer’s right to check references.

The Declaration for Federal Employment (OF-306) contains a waiver that is signed

by applicants for F

ederal employment. The waiver states, “I consent to the release

of information about my ability and fitness for Federal employment by employers,

schools, law enforcement agencies, and other individuals and organizations to

investigators, personnel specialists, and other authorized employees of the Federal

Government.”

41

The Federal Circuit has stated that “OPM has the authority to

require all individuals to complete all appointment forms, including the OF-306

and SF-86 forms, even after the date on which the appointment takes place.”

42

Unfortunately, it has become common practice for applicants not to receive this

form until the hiring process has concluded. In such cases the OF-306 does not

extend protection to reference checking activities and does not set applicant

expectations that information may be obtained from former employers.

39

Harlow and its progeny; The Privacy Act of 1974 (Privacy Act).

40

Barada, op. cit., p. 42, recommends that this waiver explicitly state that “the person seeking employment

gives away his or her right to privacy in exchange for the opportunity to gain employment.” SHRM 1998,

op. cit., found that 86 percent of the organizations they surveyed require job applicants to sign such formal

waivers allowing former employers to be contacted and references to be checked. SHRM 2004, op. cit.,

found only a slight decrease (to 72 percent) in the waiver requirement.

41

Available from OPM’s Web site at www.opm.gov/forms/pdf_fill/of0306.pdf.

42

McFalls v. Office of Personnel Management, 49 Fed. Appx, 312 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 10, 2002).

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

17

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

Several agency HR personnel raised the applicant waiver issue. They highlighted

advantages of the structured SF-171 job application formerly required of all Federal

job applicants. They acknowledged that accepting resumes introduces greater

flexibility and reduces applicant burden. However, the SF-171 sets applicant

expectations appropriately by making the issue of contacting previous supervisors

explicit much earlier in the hiring process. They affirmed that the OF-306 is often

deployed too late. The advantages of accepting resumes for agencies and applicants

alike argue against the return of the SF-171. However, it would be a simple change

to require applicants to sign an OF-306 in time to check the references of a final set

of candidates for each job vacancy.

Negligent Hiring. In a typical negligent hiring claim, an injured party alleges

that an employer knew or reasonably should have known that another employee

was unfit for the job for which he or she was employed. The harmed employee’s

case hinges on a showing that the employer’s act of hiring created an unreasonable

risk of harm. In the private sector, the legal risk for negligently hiring an employee

is real and significant. In the Federal Government, however, the legal risk for

negligent hiring is minimized by the sovereign immunity of the United States from

suit. Sovereign immunity is a legal concept applicable to the Federal Government

that serves to immunize the government from lawsuits except to the extent that the

immunity is waived by a Federal statute. The Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) is a

statute that provides a limited waiver of sovereign immunity. The FTCA is the

exclusive remedy for common law torts committed by Federal employees acting

within the scope of their employment. The FTCA exempts certain acts and

omissions by Federal employees, including the exercise of discretionary functions

such as the hiring, supervision and training of employees. The courts have rejected

FTCA claims involving negligent hiring, supervision and training of employees,

finding that they fall within the “discretionary function exception.”

43

Nonetheless,

a prudent course may be to assume that such immunity is never certain.

44

An employer’s best protection against a negligent hiring claim is to conduct a

reasonable inquiry into an applicant’s work history—a reference check—and, of

course, an employer must do this effectively and impartially with each applicant

under serious consideration for employment.

45

Hiring officials also need to

maintain perspective on this risk by remembering that it rarely becomes an issue.

SHRM found that few of the (mostly private sector) organizations it surveyed about

reference checking practices had ever been accused of negligent hiring. The

majority of survey participants (97 percent) were sure that no claim had been made

against their organization in the previous three years.

46

Less formal discussions with

43

See, e.g. Tonelli v. U.S., 60 F.3d 492 (8th Cir. 1995); KW Thompson Tool Co. v. U.S., 836 F.2d 721

(1st Cir. 1988); Cuoco v. Bureau of Prisons, 2003 WL 22203727 (SDNY 2003).

44

Based on this team’s research, all but one Federal Circuit that has addressed the issue has rejected, on

sovereign immunity grounds, negligent hiring claims brought by victims of assault or battery. See, for

example, Cuoco v. U.S. Bureau of Prisons, 2003 (SDNY 2003); Tonelli v. United States, 60 F.3d 492 (8th Cir.

1995); K.W. Thompson Tool Co. v. U.S., 836 F.2d 721 (1st Cir. 1988).

45

Andler, op. cit., p. 51; Barada, op. cit., p. 135.

46

SHRM 2004, op. cit. In 1998, SHRM reported that 90 percent of participating organizations had not

had a negligent hiring claim in the previous 3 years.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

18

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

Federal agencies found similar results—little direct experience with this legal issue,

but definite concern about the possibility.

Clean Records. The final legal issue, the impact of “clean records” upon the

reference checking process, does not constitute an immediate risk for reference

checkers, but can affect the accuracy of information obtained from Federal

Government employers. A “clean record” generally refers to an employee’s official

employment record that has been altered in a manner favorable to the employee as

a result of a settlement agreement between the employee and an employer. A

typical “clean record” settlement agreement contains a promise by the employer to

treat the employee “as if the employee had a clean record,” or words to that effect.

The agreement may also contain the employer’s agreement to remove adverse

information from the employee’s official employment record. In some cases, as the

result of a “clean record” settlement agreement, a former supervisor or human

resources specialist may know of inappropriate behavior or poor performance by a

job applicant, but may not be free to release or discuss this information. In these

cases, agency personnel cannot discuss the employee’s record candidly without

violating the settlement agreement.

While there is no empirical data addressing the percentage of applicants that possess

“clean r

ecords,” the number is likely relatively small. First, common sense suggests

that the number of employees who have entered into settlement agreements is

comparatively small in relation to the large number of Federal employees. Second,

“clean record” settlement agreements have come under increased criticism in recent

years, especially within the public sector. For instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Federal Circuit (Federal Circuit) observed that “such agreements invite

trouble.” The Federal Circuit explained that a “clean record” is problematic because

“[t]he employee expects, perhaps unrealistically, that with a ‘clean record’ potential

employers will be unable to find out about adverse actions taken by the former

employer. The former employer, when asked, must either outright lie, or attempt

some artful evasion which, because other employers now recognize what these

agencies do, in fact fools no one.”

47

Another constraining factor is the difficulty

that agencies face in fully implementing “clean record” agreements and the ease

with which they can be inadvertently breached.

Notwithstanding the difficulties resulting from “clean records,” the fact remains that

such agreements continue to occur

. As a result, there is a risk that an applicant who

has engaged in past misconduct or was a poor performer, but who has an artificially

“cleaned” record, will be hired by a misinformed employer. As of the date of this

report, there does not appear to be a published legal decision that addresses a claim

of negligent hiring related to a clean record settlement agreement. Hiring officials

should, nevertheless, consider the possibility of a clean record when they encounter

references who offer only basic facts about an applicant’s previous employment

without a convincing reason for withholding further information. This is a

particular concern when an applicant provides references from the former

employer’s human resources staff rather than from the previous work team.

47

Pagan v. Department of Veterans Affairs, 170 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

A Report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board

19

Costs and Risks of Reference Checking

While r

eference checking is not accomplished without some risks, prudent practice

allows the reference checker to avoid them. The risks of engaging in appropriate

reference checking are minimal. And, as the next section demonstrates, reference

checking has benefits beyond protecting an employer from charges of negligent

hiring practices.

Reference Checking in Federal Hiring:

Making the Call

20

Benefits of Reference Checking

Direct Benefits

T

his section summarizes the benefits of conducting thorough and disciplined

reference checks. Some benefits are near-term and straightforward. Others

are better characterized as risks or problems avoided by reference checking

and may be less appreciated.

Make Better Hiring Decisions. Reference checking is part of a larger effort to

identify the best available applicant for each open position. While other forms of

competency assessment such as structured interviews, assessment centers, traditional

tests, and even some training and experience measures have greater measurement