REPORT 413

Review of retail life insurance

advice

October 2014

About this report

This report presents the findings of ASIC’s research into, and surveillance of,

personal advice given to consumers about life insurance.

The purpose of the project was to understand the advice consumers are

currently receiving about life insurance and to identify opportunities to

promote advice that is in the best interests of consumers.

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 2

About ASIC regulatory documents

In administering legislation ASIC issues the following types of regulatory

documents.

Consultation papers: seek feedback from stakeholders on matters ASIC

is considering, such as proposed relief or proposed regulatory guidance.

Regulatory guides: give guidance to regulated entities by:

explaining when and how ASIC will exercise specific powers under

legislation (primarily the Corporations Act)

explaining how ASIC interprets the law

describing the principles underlying ASIC’s approach

giving practical guidance (e.g. describing the steps of a process such

as applying for a licence or giving practical examples of how

regulated entities may decide to meet their obligations).

Information sheets: provide concise guidance on a specific process or

compliance issue or an overview of detailed guidance.

Reports: describe ASIC compliance or relief activity or the results of a

research project.

Disclaimer

This report does not constitute legal advice. We encourage you to seek your

own professional advice to find out how the Corporations Act and other

applicable laws apply to you, as it is your responsibility to determine your

obligations.

Examples in this report are purely for illustration; they are not exhaustive and

are not intended to impose or imply particular rules or requirements.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 3

Contents

Executive summary ....................................................................................... 4

A Background ............................................................................................ 9

Purpose of our project ............................................................................. 9

The life insurance industry in Australia .................................................... 9

The regulatory framework ......................................................................11

B Project scope and methodology ........................................................14

Phase 1: Understanding the industry ....................................................14

Phase 2: Assessing the quality of advice ..............................................15

C Our findings on the industry ..............................................................18

Number and types of policies ................................................................18

Assumptions made about the duration of policies .................................22

Distribution models and costs ................................................................23

Remuneration arrangements .................................................................24

Relationship between product design and lapse rates ..........................28

D Our findings on the quality of advice ................................................40

Overview of our findings ........................................................................40

Factors that affect the quality of advice .................................................41

Warning signs of poor advice ................................................................62

The challenge for insurers and advisers ................................................64

Appendix: Life insurance advice checklist ...............................................68

Key terms .....................................................................................................72

Related information .....................................................................................76

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 4

Executive summary

1 ASIC has a focus on life insurance advice because it is of critical importance

to the long-term financial wellbeing of Australian consumers. Life insurance

is a key product through which consumers manage risk for themselves and

their families.

2 Quality financial advice helps consumers identify their life insurance needs

and find appropriate and affordable products that meet those needs.

3 This report reviews the advice consumers receive about life insurance. It builds

on other work we have done focusing on the quality of retirement advice and

advice about self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs).

1

4 Consumers purchase life insurance in one of three ways:

(a) through an advice provider (adviser);

2

(b) directly from an insurer; or

(c) through their superannuation fund and the group life cover offered by

the fund.

5 This report focuses on the first distribution channel only—that is, distribution

through personal advice. It presents the findings of our research into, and

surveillance of, advice about life insurance.

3

Our purpose in this project was to

better understand:

(a) how life insurance is sold by advisers;

(b) how advisers are remunerated for that advice;

(c) the drivers behind product replacement advice to consumers; and

(d) the quality of the life insurance advice consumers receive.

6 Conducted between September 2013 and July 2014, our research project

involved two phases:

(a) industry roundtables and a survey of 12 insurers that manufacture and

distribute life insurance products under personal advice models

(phase 1); and

(b) a targeted surveillance of advisers who give personal advice to

consumers on life insurance products, which involved a review of

202 advice files (phase 2)—our surveillance targeted advisers who sell

a large amount of life insurance products.

1

See Report 279 Shadow shopping study of retirement advice (REP 279) and Report 337 SMSFs: Improving the quality of

advice given to investors (REP 337).

2

An advice provider is a person to whom the obligations in Div 2 of Pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations

Act) apply when providing personal advice to a retail client. This is generally the individual who provides the personal

advice. For ease of reference, we refer to advice providers as advisers in this report.

3

In this report, ‘life insurance’ means ‘retail life insurance’: see paragraph 37 for how we define ‘life insurance’ in this

report.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 5

7 This work builds on action we have taken to remove poor Australian

financial services (AFS) licensees and advisers from the industry where we

have found problems with life insurance advice. In these cases, we found

evidence of poor life insurance advice that resulted in considerable detriment

to consumers, including:

(a) evidence that advisers failed to adequately consider their clients’

personal circumstance and needs, leading to situations where consumers

received inferior policy terms, paid more for cover, had health issues

excluded and, in some cases, had claims denied where they previously

had cover; and

(b) evidence of unnecessary or excessive switching of clients between

policies to maximise commission income, with a failure to consider or

recommend insurance that reasonably correlated to clients’ personal

circumstances or objectives.

4

What we found

Industry trends

8 The most common policy type across the industry is a stepped premium

policy. The premium on a stepped premium policy increases or ‘steps up’

each year according to risk factors such as the client’s age.

9 In phase 1, we found that life insurance policies are lapsing at high rates. For

example, for stepped premium policies, we found that, in 2013, policy lapses

doubled from approximately 7% in the first year to 14% in the second year.

After the initial spike, lapse rates remain high (above 14%) for the next three

years before tapering.

5

10 The drivers behind these high lapse rates include:

(a) product innovation by insurers, such as changing actuarial assumptions

at underwriting or the redesign of key policy features such as definitions

and exclusions, which leads to the repricing of policies;

(b) age-based premium increases affecting affordability; and

(c) incentives for advisers to write new business or rewrite existing

business to increase commission income.

11 We also found a correlation between high lapse rates and upfront

commission models.

4

For example, see Media Release (13-019MR) ASIC cancels licences of national financial planning business and ASIC

advisory (12-60AD) ASIC accepts permanent undertaking from Adelaide adviser.

5

A policy lapse is when a policy ceases due to non-payment or cancellation by the client. We exclude claims and a policy

ceasing due to the insured person reaching a certain age (e.g. age 65) from our definition of a policy lapse. See

paragraphs 110–111 for our definition of a policy lapse.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 6

Advice quality

12 We reviewed 202 advice files as part of phase 2. Files were selected for

review from AFS licensees who were active in giving life insurance advice:

see Section B for the methodology employed for this surveillance.

13 Our sample included advice given before and after the mandatory

commencement date for the Future of Financial Advice (FOFA) reforms on

1 July 2013.

6

14 We rated the advice by reference to the conduct obligations in the

Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act) (see Table 1) that were in force at

the time the advice was given. These conduct obligations apply to personal

advice and include the obligation to give appropriate advice, to act in the

best interests of the client and to give priority to the interests of the client in

the event of a conflict of interest. If the advice complied with the law, we

rated the advice ‘a pass’. If the advice failed to meet the relevant legal

standard, we rated the advice ‘a fail’.

15 We also commissioned an independent advice review where an external

consultant reviewed a sample of files for quality checking and to ensure our

ratings were sound and consistent: see Section B for further detail on this

methodology.

16 We found that 63% of consumers received advice that met the standard for

compliance with the law, while 37% of consumers received advice that

failed to meet the relevant legal standard that applied when the advice was

given.

7

17 We found the quality of advice varied among the advice we rated as

compliant. We found advice that clearly met the needs of the client through

to files that were barely compliant with the legal threshold. We give some

examples of this advice in this report.

18 We have found significant room for improvement among the advice we

reviewed and we will be actively working with the advice industry to lift the

standard of life insurance advice.

19 Of the advice that we rated a fail, we found serious failings with respect to

compliance with the law.

20 We also found that the way an adviser was paid (e.g. under an upfront

commission model compared to a hybrid, level or no commission model)

6

Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial Advice) Act 2012 and Corporations Amendment (Further Future of

Financial Advice Measures) Act 2012.

7

For example, s945A of the Corporations Act for pre-FOFA advice, or the requirements under s961B, 961G, 961H and 961J

for post-FOFA advice, in addition to the switching requirements under s947D.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 7

had a statistically significant bearing on the likelihood of their client

receiving advice that did not comply with the law: see Figure 18.

21 Of the 202 files in our sample, we found that where the adviser was paid

under an upfront commission model, the pass rate was 55% with a 45% fail

rate. Where the adviser was paid under another commission structure, the

pass rate was 93% with a 7% fail rate: see Figure 18.

22 Our findings in this review indicate that the impact of adviser conflicts of

interest on the quality of life insurance advice is an industry-wide problem.

Addressing this problem will require an industry-wide response.

23 This is because an individual insurer may change its remuneration

arrangements to mitigate the effect of conflicts of interest among advisers

selling their policies, but is likely to lose business to competitors. This is

commonly referred to as the ‘first mover’ problem where the first mover is

disadvantaged relative to their industry peers who pick up the business lost

by the ‘first mover’.

24 The appendix to this report includes a checklist for advisers, AFS licensees,

compliance consultants and insurers about relevant factors to consider in

giving or assessing personal advice about life insurance. The checklist

covers existing obligations as well as further considerations for giving best

practice advice.

Recommendations

25 We recommend that insurers:

(a) address misaligned incentives in their distribution channels;

(b) address lapse rates on an industry-wide and insurer-by-insurer basis

(e.g. by considering measures to encourage product retention); and

(c) review their remuneration arrangements to ensure that they support

good-quality outcomes for consumers and better manage the conflicts of

interest within those arrangements.

26 We recommend that AFS licensees:

(a) ensure that remuneration structures support good-quality advice that

prioritises the needs of the client ;

(b) review their business models to provide incentives for strategic life

insurance advice;

Note: Strategic life insurance advice includes advice on the type, level, structure and

affordability of life insurance cover based on the client’s cash flow position and which

prioritises the client’s insurance needs. Strategic advice can be stand alone or, where

appropriate, provide the framework for product advice.

(c)

review the training and competency of advisers giving life insurance

advice; and

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 8

(d) increase their monitoring and supervision of advisers with a view to

building ‘warning signs’ into file reviews and create incentives to

reward quality, compliant advice.

27 Professional associations and training providers may wish to adopt the

checklist in the appendix to this report when reviewing their adviser training

and continuing professional development programs for their members.

Our further work

28 Where the advice failed to comply with the law, we will consider

enforcement action or other appropriate regulatory action with respect to the

individual adviser or, depending on the conduct, the AFS licensee.

29 We will engage with AFS licensees, advisers and their professional

associations about the issues they need to consider in giving compliant life

insurance advice. The life insurance advice checklist in the appendix will

form the basis for that engagement to lift the standard of life insurance

advice.

30 We will update our consumer information to provide better guidance for

consumers about their life insurance needs and important things to consider

when seeking life insurance advice.

31 We hope that the findings in this report will contribute to a more informed

discussion about the need for and access to appropriate life insurance

products and personal advice that is in the long-term interests of Australian

consumers.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 9

A Background

Key points

The purpose of our project was to understand the life insurance advice

consumers are currently receiving and to identify opportunities to promote

advice that is in their best interests.

This section provides some context and background to our project,

including an overview of:

• the life insurance industry in Australia; and

• the regulatory framework, including the FOFA reforms, which

commenced on a mandatory basis on 1 July 2013 and introduced new

conduct obligations for advisers who give personal advice about life

insurance.

Purpose of our project

32 Poor life insurance advice and sales practices have been an issue in ASIC

investigations and surveillances over many years.

33 The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services

(PJC), in its inquiry into the Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial

Advice) Bill 2011 and Corporations Amendment (Further Future of

Financial Advice Measures) Bill 2011 (PJC Inquiry), made specific

recommendations about the need to monitor the quality of advice about the

sale of risk insurance.

34 The purpose of our project was to understand the life insurance advice

consumers are currently receiving and to identify opportunities to promote

advice that is in their best interests.

The life insurance industry in Australia

35 There has been media and industry commentary about the sustainability of the

life insurance industry in Australia over the past year or more, a debate

generated by some key structural challenges facing the industry, including:

(a) increasing claims arising from deteriorating economic conditions;

(b) profit write-downs by major insurance companies;

(c) downstream issues affecting profitability, such as increasing costs and

increasing lapse rates; and

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 10

(d) changing cost structures and risks, with changes to the distribution of life

insurance products in Australia as many insurers move to a direct

distribution model.

8

36 As at 30 June 2013, there were 28 life insurance companies in Australia.

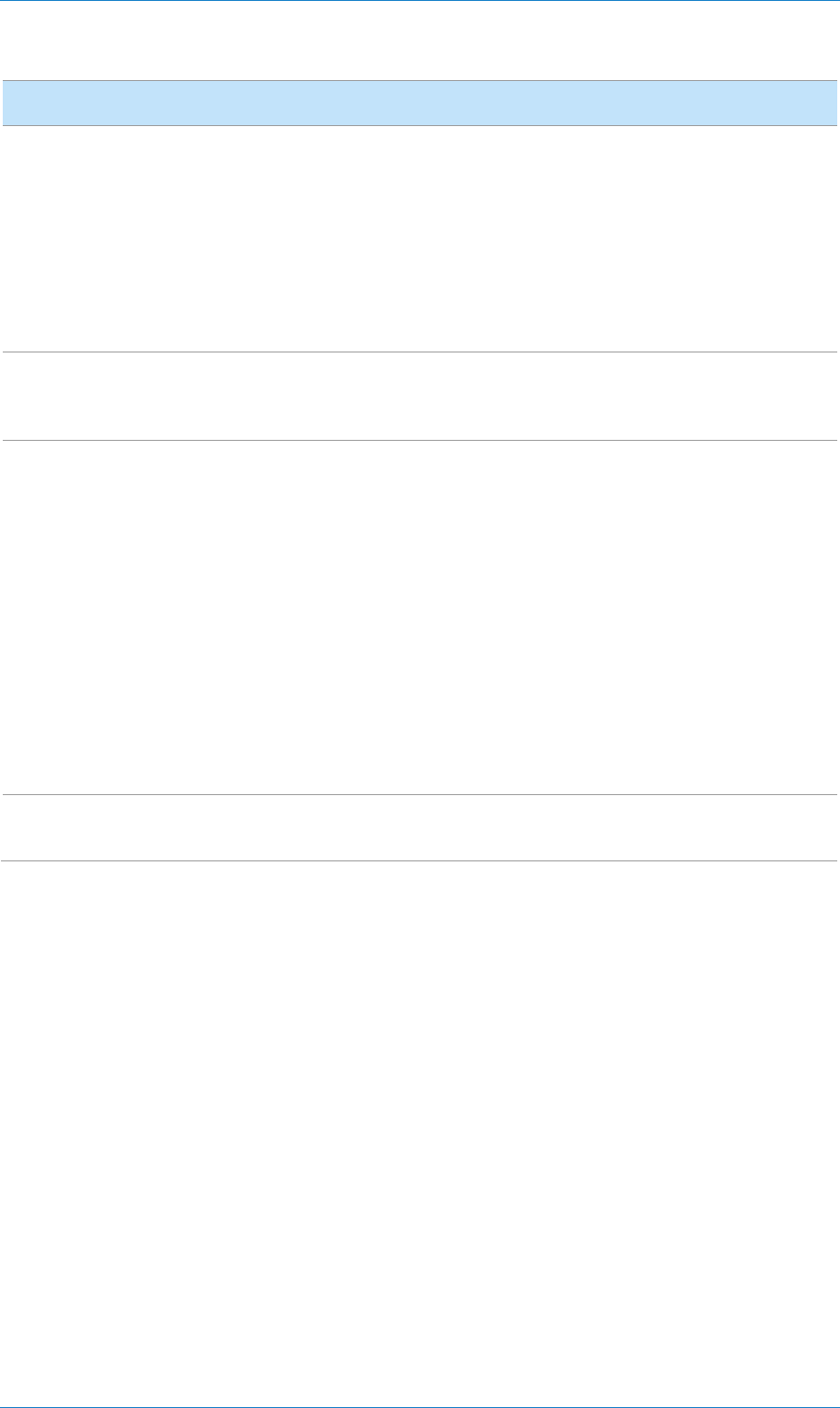

9

Figure 1 represents an aggregate overview of the life insurance industry in

Australia and the different business lines and product categories of

Australian insurers.

Figure 1: The life insurance industry in Australia

10

Source: Plan for Life, Group Total Inflows, Life insurance statistics, March 2014.

8

APRA, Insight, Issue 3, December 2013, p. 23.

9

APRA, Insight, Issue 3, December 2013. This figure remains current at the date of publication.

10

All values are total inflows of new and in force premiums as at March 2014. Values may not add up because of rounding.

Life insurance industry

($44.2b)

Group

($16.1b)

Individual

($19.8b)

Annuities

($8.2b)

Superannuation

($13.1b)

Ordinary

($6.8b)

Conventional /

investment linked

($11.1b)

Conventional /

investment linked

($0.4b)

Life risk income

protection ($0.3b)

Life risk lump sum

($1.7b)

Life risk lump sum

($4.4b)

Life risk income

protection ($2.0b)

When these policies are

sold under personal advice,

they are ‘life insurance

products’ for the purposes of

this report

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 11

37 For the purposes of this report, we define ‘life insurance’ as those lump sum

and income stream products, such as life and total and permanent disability

(TPD) insurance policies and trauma and income protection policies, sold to

retail clients under personal advice. These policies may be held or purchased

inside or outside the superannuation environment (excluding group life

policies). These policies are represented in the light grey boxes in Figure 1.

38 The total premium value of individual life risk policies without an

investment component is $8.4 billion. This figure includes both policies sold

under personal advice models, and policies sold directly or under general

advice or no advice models. As at March 2014, the individual life risk

policies sold under the combined models (personal, general, no advice)

represented about 19% of the life risk insurance sector. While there is no

comprehensive breakdown of the value of policies under advised sales

channels compared to the other channels, for historical reasons advised

channels remain dominant, although direct and online sales have seen

significant growth over recent years.

Note: In Plan for Life’s data, the category of ‘ordinary’ life insurance includes life

insurance purchased through an adviser and life insurance purchased through a direct

channel under a general or no advice model. The data does not distinguish the value of

those policies that relate to policies distributed through personal advice from those sold

under a direct distribution model.

The regulatory framework

39 As set out in Table 1, life insurers and advisers are subject to the statutory

standards and requirements of:

(a) the Corporations Act;

(b) the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act);

(c) the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Insurance Contracts Act); and

(d) the Life Insurance Act 1995 and the Life Insurance Regulations 1995.

Life insurers are also regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority (APRA).

Table 1: Regulatory framework for life insurers and advisers

Legislation/regulation

Overview of requirements

Corporations Act:

s763A, 766A, 912A,

Pts 7.7, 7.7A and 7.9

A retail life insurance product is a financial product. Insurers and advisers must hold

an AFS licence, or be the representative of an AFS licensee, as they deal in a

financial product (insurers) and provide financial product advice (advisers).

AFS licensees must comply with various obligations under the Corporations Act and

other financial services laws, including (but not limited to):

the general obligations in s912A to:

− provide financial services efficiently, honestly and fairly;

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 12

Legislation/regulation

Overview of requirements

− manage conflicts of interest;

− ensure representatives provide services competently; and

the financial services disclosure obligations in Pt 7.7 if the licensee is the

providing entity.

Part 7.7A introduced new conduct obligations for the provision of personal financial

product advice to retail clients, such as the best interests duty and related

obligations.

Part 7.9 includes the product disclosure obligations.

ASIC Act: s12CA,

12CB, 12DA and 12DB

The consumer protection provisions in the ASIC Act operate to protect consumers

from misleading and deceptive conduct or unconscionable conduct by AFS

licensees and representatives in the provision of financial services.

Insurance Contracts

Act: s13 and 29

The Insurance Contracts Act regulates the content and operation of insurance

contracts. It requires both the insurer and the insured to act towards the other, in

respect of any matter arising under or in relation to the contract, with the utmost

good faith.

The Insurance Contracts Act also sets out what consumers must do when applying

for an insurance policy, including their duty to disclose to the insurer all relevant

information about the risks the insurer is accepting. Section 29(3) allows an insurer

to avoid a policy within the first three years where the insured fails to comply with

their duty of disclosure.

The Insurance Contracts Amendment Act 2013 amends the remedies available for

insurers in cases of non-fraudulent non-disclosure under s29, so the insurer can

alter the sum insured (s29(4) and (10)) or retrospectively vary the contract in such a

way as to place the insurer in the position it would have been in if the non-disclosure

or misrepresentation had not occurred (s29(6), (7), (8) and (9)).

APRA Life insurers are also regulated by APRA, which supervises life insurers under the

Life Insurance Act 1995 and the Life Insurance Regulations 1995.

The FOFA reforms

40 The FOFA reforms introduced a suite of changes to the regulation of

personal financial advice for consumers. These changes included:

(a) a ban on conflicted remuneration (Divs 4 and 5 of Pt7.7A);

(b) new personal advice obligations, including:

(i) to act in the best interests of the client in relation to the advice

(s961B);

(ii) to ensure that the advice provided is appropriate to the client (s961G);

(iii) to warn the client if the advice is based on incomplete or inaccurate

information (s961H); and

(iv) to give priority to the interests of the client in the event of a

conflict of interest (s961J);

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 13

(c) a requirement to provide a fee disclosure statement to new clients

(s962H); and

(d) an extension of ASIC’s licensing and banning powers (s913B, 915C

and 920A).

Life insurance: Exemption from the ban on conflicted remuneration

41 The FOFA reforms did not extend the ban on conflicted remuneration to

individual life insurance sales under personal advice. That is, commission

payments for life risk insurance products (with the exceptions in

paragraphs 42(a)–42(b)) are exempted from the ban on conflicted

remuneration. Commission payments are the predominant remuneration

structure in the industry (see paragraph 89 for a description of the different

commission structures typically used in the life insurance sector). The

Corporations Amendment (Streamlining Future of Financial Advice)

Regulation 2014 does not impact on this exemption.

42 The exemption for life risk insurance is set out in s963B(1)(b) and

reg 7.7A.12A of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Corporations

Regulations), which exclude monetary benefits given in relation to life risk

insurance products, as defined by s764A(1)(e), unless they are given in

relation to:

(a) a group life risk policy inside superannuation (regardless of whether it

is for a default or another type of superannuation fund); and

(b) an individual life insurance policy for the benefit of a member of a

default fund.

11

11

Sections 29SAC(1)(a)(i) and 29SAC(1)(a)(ii) of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS Act) ban

commission payments on MySuper products.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 14

B Project scope and methodology

Key points

Conducted between September 2013 and July 2014, our research project

involved two phases:

• industry roundtables and a survey of 12 insurers that manufacture and

distribute life insurance products under personal advice models

(phase 1); and

• a targeted surveillance of advisers who give personal advice to

consumers on life insurance products (phase 2).

Phase 1: Understanding the industry

43 Phase 1 of our project began with two industry roundtables with 12 life

insurers (the insurers) to explain the scope of the project and to ensure that

our questions were appropriately targeted so as to gather the essential

information, while minimising the compliance burden on responding

insurers. We wish to thank the insurers for their cooperation and assistance.

44 We then used our compulsory notice powers to gather information from

the insurers currently writing life insurance policies under personal advice

models. We excluded insurers in run-off arrangements and we also excluded

life insurance sold directly to consumers under general or no advice models.

45 We asked the insurers questions about their current product book with a

focus on a specific list of retail policy types. Our objective was to better

understand at an aggregate industry level and at the individual insurer level:

(a) the policies and policy combinations issued to clients under personal

advice models;

(b) the policies currently in force for each policy type and how market

share was changing over time;

(c) the policy life cycles;

(d) distribution arrangements and remuneration models;

(e) information about lapse rates for each policy type, premium type,

distribution channel and remuneration model; and

(f) information about commission types and ‘clawback’ arrangements.

Note: A commission or benefit that is paid to an adviser is recovered, or ‘clawed back’,

by the insurer if the policy lapses within a certain period, usually within the first

12 months the policy is on foot.

46

Section C sets out our analysis of the data gathered.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 15

Phase 2: Assessing the quality of advice

47 Phase 2 involved a major surveillance of personal advice given to consumers

about life insurance.

48 This was a targeted surveillance in so far as the sample of files selected for

review was not a random sample of advice from randomly selected AFS

licensees or authorised representatives. Rather, our objective was to identify

the licensees and authorised representatives who were active in giving life

insurance advice so as to test the quality of advice these licensees were

giving.

49 To identify AFS licensees to include in our surveillance, we asked the

insurers identified in phase 1 to tell us the three licensees or authorised

representatives who had:

(a) the highest number of new ‘in force’ policies written in the relevant

period (2012 and 2013 financial years); and

(b) the highest number of policy lapses in the relevant period.

50 We asked for this information to identify AFS licensees who had recently

given new and replacement product advice. The responses to the question in

paragraph 49(b) were inconsistent due to differences in interpretation among

the participating insurers; we did not select any licensee on the basis of the

insurers’ response to this question. Nevertheless, our final sample included

both advice to new clients and replacement product advice.

51 Of the pool of AFS licensees identified in the high selling category by

insurers, we excluded licensees that had been the subject of recent regulatory

action by ASIC. We then chose two large licensees and three medium

licensees from the remaining pool. We added two small licensees to the

sample so that our final sample included advice from a broad mix of

licensees.

Note: The small licensees we selected were not chosen on the basis of known risk

factors. To maximise efficiency, we used seven files that ASIC had previously obtained

for different projects (in which the focus was not life insurance advice). The results

from these licensees had a negligible impact on the overall results of this report.

Conducting the file reviews

52 After we had identified the AFS licensees and authorised representatives

who would be included in the sample, we used our compulsory notice

powers to gather the following information:

(a) the name of the authorised representative who provided the advice on

the insurance and/or risk product;

(b) the client name;

(c) a description of the product name and/or type;

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 16

(d) the name of the insurer who paid the commission to the licensee;

(e) the date the commission was received by the licensee;

(f) the amount of upfront commission received; and

(g) the amount of ongoing commission received.

53 From this information, we requested client files for review based on:

(a) the date the commission was paid (to identify pre-FOFA and post-

FOFA advice);

(b) the amount of commission paid (to identify new advice that involved

the giving of a Statement of Advice (SOA) because this was an advice

review); and

(c) the types of life insurance products that were the subject of the advice to

ensure that our policy sample was reasonably diverse, covering a suite

of policy types (e.g. life, TPD, trauma and income protection

insurance).

54 We looked at 243 files in total. Our reviews were the subject of two quality

checks:

(a) 101 files were reviewed a second time by analysts who were former

financial planners with current Certified Financial Planner

qualifications; and

(b) 20 files (five pre-FOFA and 15 post-FOFA files) were reviewed by an

independent external consultant to ensure our ratings were sound and

consistent.

55 To maintain the integrity of our sample and analysis, we excluded from our

statistical analysis:

(a) files from two advisers where we had specific intelligence that they

were giving poor life insurance advice; and

(b) files that were inadequate or otherwise incomplete and this made it

impossible to rate the advice for the purpose of this review without

serving additional notices. We will be raising this issue individually

with the relevant AFS licensees.

56 Our final sample of advice included 202 advice files from seven AFS

licensees. It involved a random selection of advice from those licensees from

79 individual advisers and included a spread of pre-FOFA and post-FOFA

advice: see Table 2.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 17

Table 2: Review of advice files—Pre-FOFA and post-FOFA

Advice type

Number of files

Percentage of files

Pre-FOFA advice

94

47%

Post-FOFA advice

108

53%

Total

202

100%

57 The 202 files we reviewed included a broad range of advice types, including:

(a) advice to new clients;

(b) product replacement advice to new or existing clients; and

(c) scaled life insurance advice.

58 ASIC analysts used an advice review template to standardise the assessment

of the files. Most of the analysts were former financial planners with years of

practical experience.

59 We rated the advice against the relevant legal obligations in force at the time

the advice was given. If the advice complied with the law, we rated the

advice ‘a pass’. If the advice failed to meet the relevant legal standard, we

rated the advice ‘a fail’. As will be seen in our discussion of the case studies

and in our life insurance advice checklist (see the appendix), we identified

key areas for improvement to lift the quality of life insurance advice

consumers receive.

60 We rated the pre-FOFA advice a pass if the advice was appropriate (i.e. it

met the then test in s945A of the Corporations Act).

61 In rating the post-FOFA advice, we applied the new best interests duty

(s961B), the appropriate advice test (s961G) and the client priority rules

(s961J), and rated the advice a pass or a fail. Where there was some doubt as

to the final rating, we gave advisers the benefit of the doubt given the law

was new.

62 Section D sets out our detailed findings from phase 2.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 18

C Our findings on the industry

Key points

This section sets out our findings from phase 1 in which we sought to better

understand the life insurance policies sold under personal advice models.

For the 12 participating insurers in the survey, we found that:

• there were 2.6 million policies in force at 30 June 2013, representing a

5.8% increase over the previous year;

• life only and income protection policies are the most common policies;

• for the purposes of product design and pricing, insurers assume that

policies written will remain in force for an average duration of 86 months

(7.2 years);

• 58% of insurers distribute their policies through AFS licensees operating

personal advice models;

• upfront commission arrangements are the dominant remuneration

arrangement for advisers by a significant margin; and

• life insurance policies are lapsing at very high rates.

Number and types of policies

63 We asked insurers what policy types and/or combinations they issued under

personal advice models. Insurers sold:

(a) life cover only;

(b) life and TPD cover only;

(c) life and trauma cover;

(d) life, TPD and trauma cover;

(e) TPD cover only;

(f) TPD and trauma cover;

(g) trauma cover only;

12

(h) income protection cover; and

(i) income protection cover combinations.

13

64 At 30 June 2013, the insurers had 2.6 million policies in force. This

represents the total number of policies in force, not the lives insured, as

many consumers will hold more than one policy type.

12

Trauma insurance includes coverage for critical illness.

13

A minority of insurers sold policies in other combinations (e.g. income protection and trauma; income protection and TPD;

income protection, trauma and TPD). For consistency, we have grouped these policy combinations under the banner of

income protection combinations.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 19

65 The life insurance policies in force that were the subject of our survey grew

at a rate of 4.5% in 2011–12 and 5.8% in 2012–13: see Table 3.

Table 3: Life insurance policies in force (2011–13)

Year

Policies in force

Percentage growth

2010–11

2,357,047

N/A

2011–12

2,462,362

4.5%

2012–13

2,605,395

5.8%

66 Life only and income protection policies are the most common policies in

force, comprising 32% and 21% respectively of the overall policies in force

at 30 June 2013. Figure 2 shows the market share for each policy type as a

proportion of the total number of policies in force.

Figure 2: Market share of policy types (2011–13)

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40%

Life only

Life and TPD

Life and trauma

Life, TPD and trauma

TPD only

TPD and trauma

Trauma

Income protection

Income protection combinations

Market share

Policy type

2011

2012

2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 20

67 While still dominant, the market share of stand-alone life policies declined

across the survey period. Stand-alone trauma policies are increasing in

market share, along with other policy combinations such as TPD and trauma,

which has seen a 64% increase in market share in 2013, albeit off a low base.

68 The market share of other policy types or combinations has remained

relatively stable. However, the growth in newer policy combinations

suggests the market is moving away from stand-alone life or stand-alone

TPD cover. Instead, those policy types form the nucleus in newly configured

policy bundles comprising different policy combinations: see Figure 3.

Figure 3: Annual percentage change in market shares of policy types (2012–13)

Product innovation and product bundling

69 There are sound commercial reasons for insurers to redesign policies and/or

offer them in new policy combinations, including in response to advances in

the identification of new medical conditions or advances in the treatment or

-10% -5% 0% 5% 10%

15%

20% 25% 30% 35%

Life only

Life and TPD

Life and trauma

Life, TPD and trauma

TPD only

TPD and trauma

Trauma

Income protection

Income protection combinations

Growth rate

Policy type

Growth in 2012

Growth in 2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 21

prognosis of existing medical conditions. An insurer may redesign policies

with revised definitions and promote them to their distribution channels to

win market share or attract a new segment of the market.

70 New policies on issue may benefit the insurer by replacing high-cost legacy

policies, which may have been poorly designed or underwritten, or which

had unsustainably broad definitions or conditions. Product innovation and

redesign can therefore be a useful tool to manage claims exposures on a

legacy book of policies.

71 Product innovations and new policy combinations may also evolve from

regulatory changes.

14

72 Product innovation and product bundling can be a positive for consumers. It

may mean that they can:

(a) access new products with tailored cover; or

(b) access a broader class of products perhaps at lower cost (e.g. if an

insurer applies multi-cover discounts on premiums).

73 Product innovation and reconfigured policy combinations may also be

attractive to advisers where the cost, policy terms and definitions of new

products may be more suitable to a client than an existing product.

74 However, product innovation and bundling can also lead to overinsurance,

which may ultimately be unaffordable for consumers. Product innovation

may also provide a rationale for advisers to rewrite insurance for existing

clients in a way that delivers only marginal benefits to the client but at

significant additional cost to them. The structure of incentives in the advice

industry means that advisers have a clear financial incentive to write new

business for clients with existing insurances.

75 Insurers also have commercial incentives to write more business, and

product innovation and bundling is an important tool to gain or re-gain

market share in a competitive environment.

Product design

76 Life insurance products comprise ‘fixed’ and ‘moving’ parts. The fixed parts

include the product’s key features and benefits, and the actuarial

assumptions (such as the expected duration of the policies) that affect how

the product is priced at the time of underwriting. The moving parts include

those aspects of the policy customised to fit the client at the time of

underwriting and include the sum insured, any add-on benefits, exclusions or

loadings, and the premium type (stepped or level) chosen by the consumer.

14

For example, see the 2007 tax ruling (TR 2006/10) and 2014 amendments to the SIS Act and the Superannuation

Guarantee (Administration) Regulations 1993.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 22

77 The premium on a stepped premium policy typically increases each year with

age and they are the most common premium type across the industry. Level

premiums, by contrast, are fixed at the same level for the duration of the

policy. The value of a stepped premium versus a level premium differs for

different consumers and is a key factor for advisers to consider when weighing

up the affordability of cover for a client and their ability to retain the cover

over time.

15

Assumptions made about the duration of policies

78 We asked insurers about the assumptions they made about the duration of

policies written over the survey period. These forward-looking assumptions

tell us the average length of a policy, as anticipated by the insurers in the

year the policy was underwritten. They also inform how insurers price

policies at the commencement of the policy and price premium increases

over time. They are significant commercial decisions that shape the value of

the retail policy book at the time of underwriting and into the future.

79 There was a high degree of uniformity across the industry regarding assumed

policy durations for stepped premium policies.

80 Life insurance policies, singly or in combination with TPD and/or trauma

cover, had the longest assumed durations—between 86 and 93 months

(between seven and eight years) on average: see Figure 4.

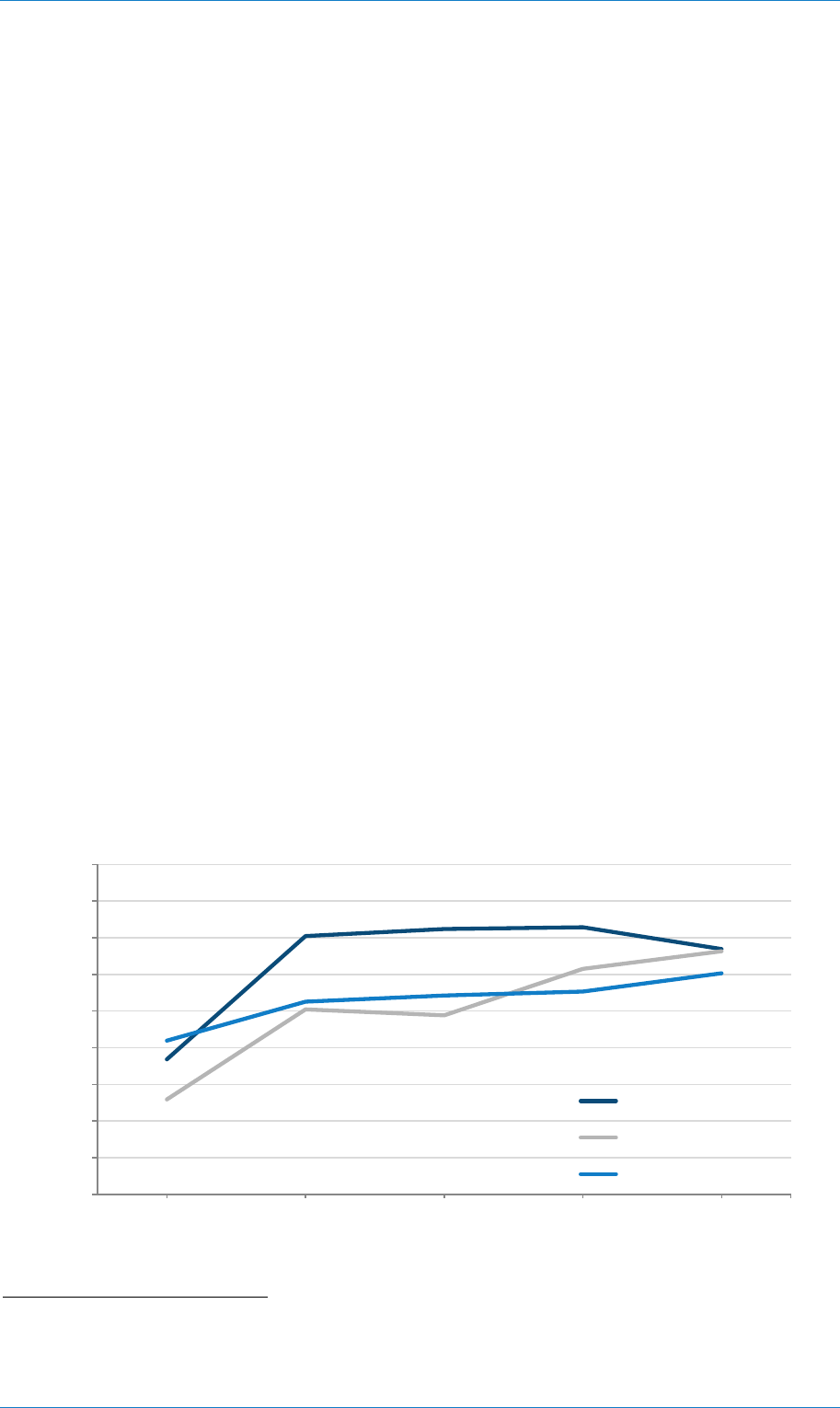

Figure 4: Average assumed durations for stepped premium policies by policy type (2011–13)

Note: This figure is based on 10 of the 12 insurers in our sample. Some insurers were omitted to maintain their anonymity or

because their data could not be compared accurately with other insurers’ data.

15

Stepped premiums have been criticised for discouraging longevity in product holdings because of the step increases in

premiums: see Ruth Liew, ‘Suncorp argues for life changes’, Australian Financial Review, 25 September 2013.

70

80

90

100

Life only Life and

TPD

Life and

trauma

Life, TPD

and trauma

TPD TPD and

trauma

Trauma Income

protection

Months

Policy type

2011 2012 2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 23

81 With some variation for different policy types, our data shows that, for the

purposes of product design and pricing, insurers assumed that policies

written in the relevant time period would remain in force for an average

duration of 86 months (7.2 years).

82 However, with the exception of income protection policies, the data shows

assumed durations for stepped premiums are decreasing.

83 Across the industry, insurers and their actuaries are revising downward the

expected duration of policies. These revisions affect policy pricing—if a

policy is assumed to be retained by the insured for a shorter duration, the

opportunity for the insurer to recover the cost of establishing the policy must

also be revised. This in turn affects the size of stepped premium increases

because the premium must cover costs over a shorter policy duration.

84 By contrast, insurers are assuming that level premium policies will have

significantly longer durations, at 109 months (9.1 years). However, the data

for level premium policies shows the same trend with insurers incrementally

revising the policy durations down across the survey period.

85 Assumptions made by insurers in the underwriting process have significant

commercial effects over time. Our analysis of this data suggests that insurers

are changing key actuarial assumptions about product duration, in an effort

to ‘catch up’ to changes in the market (e.g. increasing lapse rates).

Distribution models and costs

86 Insurers use a number of channels to distribute life insurance policies to

consumers. These include:

(a) retail personal advice models operated by the insurer or under the AFS

licence of a related corporate entity;

(b) retail personal advice models operated by another AFS licensee; and

(c) direct distribution models (i.e. a no advice model such as online

distribution channels, including comparison websites).

87 More than half of the insurers in our sample (58%) distribute their policies

through AFS licensees operating personal advice models. Of the remaining

42%, the majority reported that their policies were distributed by AFS

licensees where the advice model was not known by the insurer. One insurer

distributed its policies under a mix of advice models, including via their own

salaried employees.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 24

Remuneration arrangements

88 For life insurance distributed under personal advice models, advisers are

typically paid under commission arrangements. To identify the spectrum of

remuneration arrangements in the market, we asked insurers how they paid

their advice channels so we could understand:

(a) the most common remuneration arrangements in the market; and

(b) the extent to which those arrangements differed, depending on:

(i) whether advice was given (personal, general or no advice); and

(ii) whether the advice was given under the insurer’s own AFS licence

or by another licensee under its own licence.

89 We asked for this information across the survey period to understand the extent

to which remuneration arrangements may have changed over time.

Categories of remuneration arrangements

90 We also asked insurers to categorise their remuneration arrangements. The

following labels are commonly understood and applied in the industry:

16

(a) Upfront commission—This is generally an upfront commission of 100%

to 130% of the new business premium and an ongoing commission of

around 10% of renewal premiums.

(b) Hybrid commission—This is generally an upfront commission of 70%

of the new business premium and an ongoing commission of around

20% of renewal premiums.

(c) Level commission—This is generally a flat rate upfront commission of

around 30% on the new business premium and an ongoing commission

of around 30% of renewal premiums.

(d) No commission—This includes fee-for-service remuneration

arrangements, where typically the adviser would rebate any commission

paid by an insurer back to the client and the client would pay a fee for

service, as negotiated between the adviser and the client, which would

vary depending on the nature, scope and complexity of the advice

provided to the client.

(e) Salaried employee—In this case, remuneration is not by commission.

Clawback arrangements

91 We also asked insurers about the circumstances in which they claw back

commissions paid to advisers. A commission or benefit that is paid to an

16

For example, typically advisers are paid by an upfront commission and an ongoing commission, or trail, set at different

levels depending on the type of arrangement chosen by the adviser.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 25

adviser is recovered, or ‘clawed back’, by the insurer if the policy lapses

within a certain period, usually within the first 12 months the policy is on

foot.

92 Clawback arrangements are designed to provide a disincentive to advisers to

rewrite insurance cover for existing clients during the ‘clawback period’: see

paragraphs 122–128.

Commission arrangements

93 Typically, advisers who are paid by commission choose which commission

model they wish to be paid under in the insurance application form and the

commission is paid when the policy is in force.

94 Commission remuneration arrangements pay advisers for product sales

(upfront) and ongoing commissions on receipt of each year’s annual

premium. Commission remuneration arrangements mean that the advice cost

is built into the product (described as a commission).

95 The value of the commission to the adviser directly relates to the value of the

business to the insurer. This is because insurers calculate the commission as

a percentage of the annual premium paid by the client. The total premium on

the policy (or policies) the client purchases is affected by:

(a) any new or voluntary increases on the insured benefits or sum insured;

and

(b) any loadings (for age or existing medical conditions) or any additional

features or benefits that may apply to the policy.

96 Under commission arrangements, there is no necessary relationship between

the cost or complexity of the advice and the remuneration received by the

adviser. The consumer pays the premium to the insurer. The insurer pays the

commission to the AFS licensee. Each insurer applies its own formula for

each commission type in their remuneration schedule.

97 The amount of commission an adviser receives varies according to the terms

of their agreement with their AFS licensee. For example, a licensee may split

the commission earned on a fixed formula basis with the adviser, passing on

85% to the adviser and retaining the balance of 15% of the commission. In

other cases, the licensee may charge a fixed flat annual fee to the adviser and

pass on 100% of the commission earned to the adviser.

98 Advisers must disclose their remuneration arrangements in the SOA.

However, it may not always be clear to the client exactly how they are

paying for the advice. While the commissions are disclosed in the SOA, it

may appear to the client that the payment to the adviser comes from the

insurer and that they do not pay for the advice. Indeed, many SOAs leave the

section relating to the ‘advice fee’ blank or state N/A (not applicable).

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 26

Ultimately, the consumer pays through their premium for the commission to

be paid to an adviser.

99 Advisers can rebate (or ‘dial down’) the commission they would receive,

which reduces the premium a client pays by reducing the remuneration the

adviser will receive. Most insurers enable advisers to discount the premiums

by any whole percentage point up to a maximum of 30%. We found this to

be uncommon.

100 There is some variation among insurers in how they structure their

remuneration arrangements. Remuneration schedules include the

commission payments for each commission type, what premium discounts

may apply and in what circumstances (e.g. multi-policy discounts), and the

circumstances where commissions paid will be ‘clawed back’ by the insurer

in the event of a policy lapse within the first year.

101 Along with policy terms and claims experience, the remuneration

arrangements on offer by different insurers can have a significant bearing on

which insurer a given adviser may be more likely to recommend to their

clients.

102 Upfront commission models that pay on average 110% of a new business

premium to an adviser (with an ongoing commission of around 10%)

represent an incentive for advisers to:

(a) write new business;

(b) increase the sum insured or the level of cover the client holds because

the commission is calculated on the premium, which is based on the

sum insured, so generally the higher the premium paid, the more

revenue is earned by the adviser; and

(c) give product replacement advice to clients with existing insurance

arrangements, resulting in the adviser earning a new upfront

commission on the replacement policy, provided any clawback period

has expired on the current policy.

103 Upfront commission arrangements are the dominant remuneration

arrangement by a significant margin, at 82% of the industry. Figure 5 shows

the distribution of remuneration models across the industry and how that

distribution has changed across the survey period.

104 The average is very high—for some insurers, more than 90% of their advice

channels are paid under an upfront commission model. A minority of

insurers appear to be developing their hybrid distribution channels.

105 While there is some variation among insurers, the general trend is that

remuneration arrangements are relatively stable. The vast majority of

advisers choose to be remunerated under upfront commission models.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 27

Figure 5: Remuneration models—Averages (2011–13)

106 Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the breakdown of remuneration model by insurer

in 2012 and 2013.

Figure 6: Breakdown of remuneration model by insurer (2012)

Note: This figure is based on 11 of the 12 insurers in our sample. We omitted data from insurers only in circumstances where it

was necessary to maintain their anonymity or because their data could not be accurately compared with other insurers’ data.

0.7%

1%

4%

12%

82%

0.5%

1%

5%

13%

80%

0%

1%

5%

10%

84%

Salaried employee

No commission

Level commission

Hybrid commission

Upfront commission

Percentage of remuneration

Remuneration model

2011

2012

2013

98%

91%

90%

88%

80%

79%

80%

55%

79%

70%

68%

6%

6%

9%

18%

10%

11%

35%

14%

13%

26%

11%

5%

6%

5%

15%

4%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1

2

3 4

5

6

7

8 9

10

11

Percentage of remuneration

Insurer

Upfront commission Hybrid commission Level commission No commission

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 28

Figure 7: Breakdown of remuneration model by insurer (2013)

Note: This figure is based on 11 of the 12 insurers in our sample. We omitted data from insurers only in circumstances where it

was necessary to maintain their anonymity or because their data could not be accurately compared with other insurers’ data.

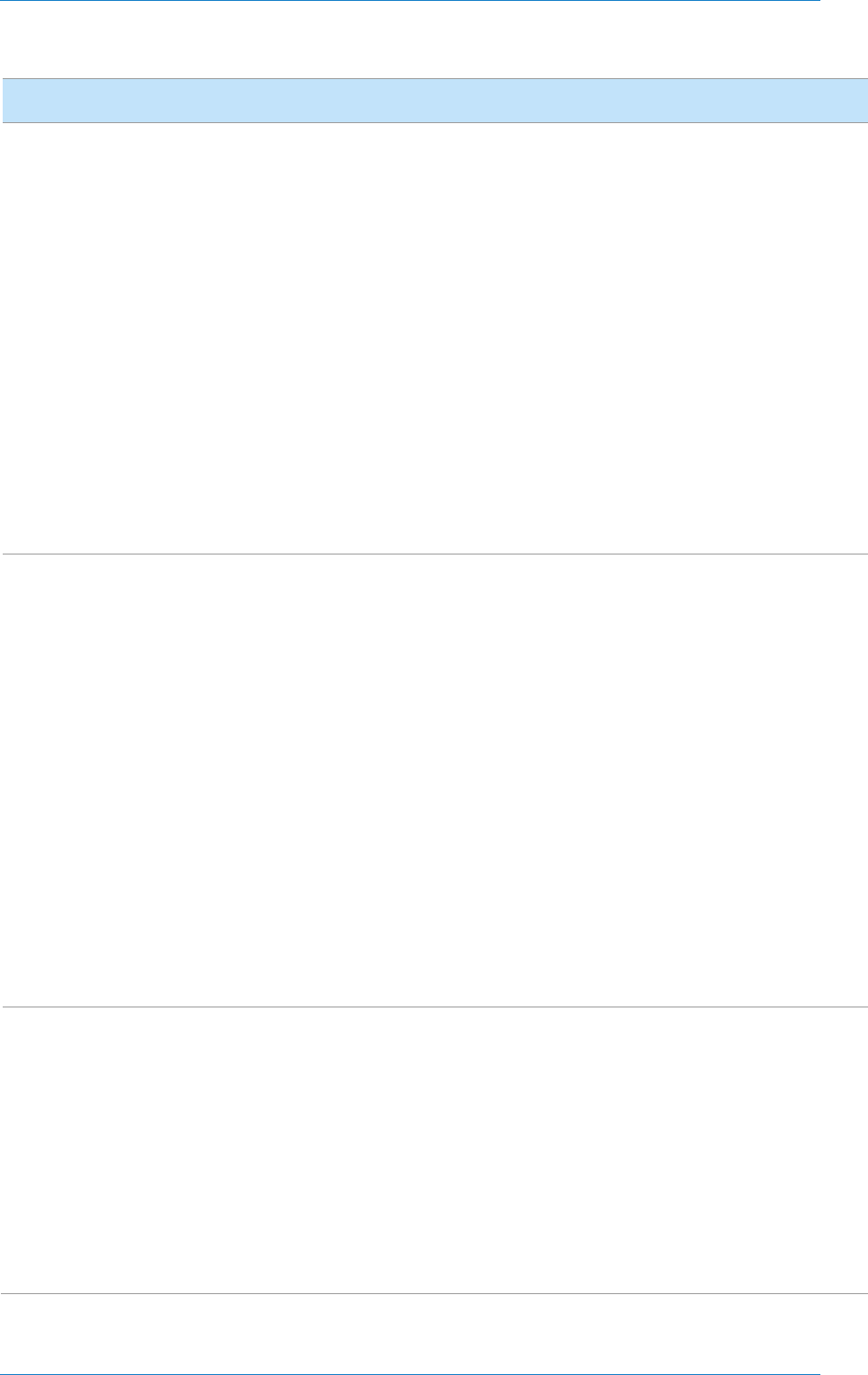

Relationship between product design and lapse rates

107 To understand the relationship between the assumptions built into product

design and policy lapse rates, we asked insurers:

(a) how many policies were in force for each policy type and distribution

channel;

(b) for each policy type, the average duration (expressed in months) of the

policies that ceased for any reason for each year in the survey period;

and

(c) the lapse rate (expressed as a percentage) for each policy type for both

stepped and level premiums for each year across the survey period.

108 The data about actual durations gives us a snapshot of average durations at a

moment in time: see Figure 8. For example, life only policies that ceased in

2013 for any reason were, on average, in force for 97 months, or just over

eight years.

Note: The figures for actual durations (Figure 8) are backward looking in time and

cannot be compared to figures for assumed durations (Figure 4), which are forward

looking projections as to the assumptions made at the time of underwriting.

109

The actual duration data also shows that, across 2011–13, life policies

remained in force for longer before ceasing for any reason. Regardless of the

reason that a policy ceases, policies are, on average and excepting life and

TPD, remaining in force for longer.

98%

91%

90%

89%

81%

79%

78%

78%

76%

72%

58%

6%

7%

8%

15%

10%

11%

18%

16%

13%

37%

11%

6%

13%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1 2

3 4 5 6 7 8

9 10 11

Percentage of remuneration

Insurer

Upfront commission Hybrid commission Level commission No commission

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 29

Figure 8: Average actual duration for stepped premium policies by policy type (2011–13)

Note: 11 of the 12 respondents provided data for this question. The data from one insurer could not be compared accurately

with the other data.

Lapse rates

110 For the purposes of this project, we defined a policy lapse as when a policy

ceases due to non-payment or cancellation by the client.

17

111 We do not consider the following examples to be policy lapses and asked

insurers to exclude these policy events from their responses:

(a) a claim on a policy;

(b) a policy ceasing due to the insured person reaching a certain age (e.g.

age 65);

(c) a change in ownership of a policy from individual ownership to SMSF

ownership, with the same underlying insured person and risk;

(d) a policy being unconditionally reinstated on payment of an outstanding

premium, after non-payment has occurred for a period of time;

(e) a policy owner electing to discontinue one of the benefits the policy

commenced with (e.g. the original policy had life, TPD and trauma

cover, but the policy owner chooses to discontinue the trauma cover,

while continuing with the life and TPD cover); and

(f) one person under a policy that covers multiple people ceasing to be

insured, but the policy remaining in force for the other person or people.

17

We asked insurers to apply our definition to calculate lapse rates. For commercial reasons, many insurers calculate the

lapse rate by reference to the value of the premium that lapsed (e.g. $5,000 or $50,000 premium lapsed). Calculating the

lapse rate in this way is relevant to the application of each insurer’s clawback arrangements.

0

20

40

60

80

100

Life only Life and

TPD

Life and

trauma

Life, TPD

and trauma

TPD TPD and

trauma

Trauma Income

protection

Months

Policy type

2011

2012

2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 30

112 Our objective was to better understand:

(a) what types of policies were lapsing and when those policies were

lapsing to identify any trends in lapse rates; and

(b) the overall lapse rate profile, to identify any factors that may affect the

lapse rate, such as consumer price sensitivity to premium increases or

the effect of incentives on adviser behaviour.

113 For this reason, we asked insurers to tell us their lapse rate (expressed as a

percentage) for each policy type across the three-year survey (June 2011 to

June 2013) period for both stepped and level premium types. We also asked

insurers to tell us the period in which a policy lapsed—that is, before the end

of the first year, from year 1 to year 2, year 2 to year 3, and so on up to year 5.

114 Regardless of the policy type, lapse rates are lowest in the first year of the

policy, and increase sharply from the first to the second year: see Figure 9

and Figure 10. For example, during the move from the first to the second

year:

(a) lapse rates for income protection policies increased from 9% to 16.4%

(see Figure 9); and

(b) lapse rates for ‘life and TPD’ policies more than doubled from 4% to

10% (see Figure 10).

Figure 9: Lapse rate by policy type—Stand-alone policies

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Up to year 1 Year 1 to year 2 Year 2 to year 3 Year 3 to year 4 Year 4 to year 5

Lapse rate

Policy duration

Life only

TPD

Trauma

Income protection

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 31

Figure 10: Lapse rate by policy type—Combination policies

115

For stepped premium policies that lapsed in 2013, policy lapses doubled

from approximately 7% for policies that had been held for less than a year to

14% for policies that had been held for between one year and two years: see

Figure 11. We found that these lapse rates remained persistently high

regardless of the policy duration (i.e. the length of time the policy had been

held before lapsing). This contrasts to the data for policy lapses in 2011,

when the lapse rate begins to taper after the initial spike after year 1. Across

the three-year time period, the data suggests that the profile of lapse rates is

changing. Lapse rates are increasing sharply after year 1 and remaining

persistently high for stepped premium policies.

Figure 11: Aggregate lapse rates for stepped premium policies

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Up to year 1 Year 1 to year 2 Year 2 to year 3 Year 3 to year 4 Year 4 to year 5

Lapse rate

Policy duration

Life and TPD

Life and trauma

TPD and trauma

Life, TPD and trauma

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Up to year 1 Year 1 to year 2 Year 2 to year 3 Year 3 to year 4 Year 4 to year 5

Lapse rate

Policy duration

2011 2012

2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 32

116 Stepped premium policies lapsed at a much higher rate than level premium

policies. Consumer price sensitivity to stepped premium price increases is

likely to be a contributing factor in the difference between the lapse rates for

stepped and level premium policies.

Note: Research by Investment Trends indicates that the price of premiums was the

reason 38% of people cancelled their life insurance—19% said they could no longer

afford the insurance and 19% said that the premiums increased too much. This research

also identified the fact that a significant driver in consumer switching is price sensitivity

to premium increases—33% of respondents in the Investment Trends research said that

lower premiums would make them more likely to change their life insurance provider

and, of consumers who did switch provider in the last two years, their reasons for

switching life insurers were premiums increasing too much (27%), and finding a

provider with cheaper premiums (21%).

18

117 Level premium policy lapse rates show a similar spike after the first year;

however, after this spike the lapse rates begin to taper down significantly:

see Figure 12.

118 This suggests that once the policies have been in force for the first few years,

consumers seem more likely to retain the policies over time and they are

therefore relatively less likely to lapse compared to stepped premium

policies.

119 Level premium policies are more likely to suit consumers who take them out

at a younger age and intend holding the policy for a long time. It is only after

a long period of time that the value of the initial high premium of a level

policy when compared to a stepped premium policy is realised.

Figure 12: Aggregate lapse rates for level premium policies

18

See Investment Trends, Investor product needs report, November 2013, I-352, I-350, I-351.

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Up to year 1 Year 1 to year 2 Year 2 to year 3 Year 3 to year 4 Year 4 to year 5

Lapse rate

Policy duration

2011 2012 2013

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 33

120 Stand-alone life insurance and income protection policies represent more

than 50% of the market share for life insurance in Australia: see Figure 2.

However, these policy types experienced lapse rates of 12%–16% in the

second year the policies are in force, with the lapse rates remaining high year

after year: see Figure 13.

Figure 13: Lapse rates for life only and income protection insurance

121 The lapse rates for life insurance policies covered by our survey are

consistent with the upward industry trend of lapse rates that APRA has

reported (see Figure 14):

Overall, annual lapse rates for both lump sum (death/TPD) and disability

income benefits have increased from 11%–12% per annum when they were

at their lowest level in 2006 to 16%–17% per annum in 2013.

19

19

APRA, Insight, Issue 3, 2013, p. 39, Figure 5. Note that APRA calculates lapse rates by premium, not policy number.

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Up to year 1 Year 1 to year 2 Year 2 to year 3 Year 3 to year 4 Year 4 to year 5

Lapse rate

Policy duration

Life only Income protection

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 34

Figure 14: Lapse rates for individual term life insurance

Source: Plan For Life, Life insurance statistics, June 2013, as cited in APRA, Insight, Issue 3, 2013, p. 39.

Lapse rates and commission clawback

122 Regardless of the policy type or premium type, our data shows a sharp

increase in lapse rates after policies have been in force for more than

12 months. These lapse rates then remain persistently high over time.

123 The 12-month period is significant for two reasons:

(a) for stepped premium policies, the policy renewal anniversary is the

point at which the first stepped premium increase will apply; and

(b) it is the point at which the clawback period expires for adviser

commissions.

124 The uniformity of the sharp increase in lapse rates after the expiry of the

clawback period suggests that the incentive for advisers to write new

business increases once the clawback period ends.

125 Some insurers taper their clawback arrangements so that 100% of the

commission is clawed back if the policy lapses within the first six months,

50% if the policy lapses at nine months, and so on.

126 Some individual insurers include in their remuneration schedules specific

measures designed to address high lapse rates among certain advisers or

affecting certain classes of policies. Such measures include:

(a) the application of longer clawback periods to some clusters of policies

or advisers;

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 35

(b) the exclusion of level premium policies from their clawback

arrangements;

(c) the application of specific clawback mechanisms to policies that are

being rewritten with the same insurer within a certain timeframe (e.g.

five years);

(d) restricting an adviser to level commission where that adviser’s lapse

rate exceeds a certain threshold; or

(e) restricting advisers to certain commission models subject to the age of

the insured at application.

127 While there was some common ground among these measures, there was

also significant diversity among approaches, including approaches to the

tapering of clawback periods. Commercial decisions about remuneration

arrangements at the individual insurer level are limited in their broader

industry impact. Where an adviser chooses their remuneration arrangement,

they have an incentive to write new business or rewrite existing business

with an insurer or insurers whose remuneration model is most attractive to

them.

128 Clawback arrangements are designed to provide a disincentive to advisers to

rewrite existing insurance cover for clients during the clawback period—that

is, to address the conflicts of interest inherent in a remuneration model that

gives advisers the incentive to write new business or rewrite existing

business. However, they generally have no application beyond the first year

of the policy and are therefore a blunt instrument to address structural issues

with remuneration arrangements.

Lapse rates and average policy durations

129 Our analysis of the insurer data shows that, at an aggregate level, policy

durations are increasing over time: see Figure 8. That is, at an aggregate

level, policies are being held for longer before a claim or other event occurs

(such as the insured reaching an age limit causing the policy to cease).

130 This may appear inconsistent with our findings that the assumed duration of

policies is decreasing and lapse rates are increasing. This is explained in part

by the fact that the average duration of a policy is arrived at by calculating

how long a policy has been held before ceasing for any reason (i.e. a

backward-looking measure), while assumed durations are a forward-looking

measure made by actuaries at the time of policy design.

131 Another relevant issue is the application of different definitions. Our

definition of actual duration includes a broader group of policies than our

definition of lapse rate, which explicitly excludes claims or a policy ceasing

due to the insured reaching an age limit: see paragraphs 110–111. This

means that the two data sets cannot be directly compared.

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2014

REPORT 413: Review of retail life insurance advice

Page 36

132 Policies in the actual duration data set include policies that may have

recently lapsed, including policies that end because the insured has met an

age limit (such as reaching age 65). Such policies may also have been held

by the insured for a long period of time. Demographic factors such as the

ageing of the population may also be contributing to the overall increase in

actual policy durations across the survey period.

133 A detailed analysis of these variables would require further data and analysis

and is beyond the scope of this report. However, in commenting on claims

experience, APRA recently expressed concerns that there may be an anti-

selection effect in certain policy cohorts, where less healthy lives will be

more inclined to retain their policies over time and more healthy lives less so

(particularly in the face of rising premiums).

20

Lapse rates and remuneration models

134 In addition to asking insurers about lapse rates by policy and premium type,

we also asked about lapse rates by remuneration model for both stepped and

level premium policies.

135 Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the lapse rates for stepped and level premium

policies respectively, by the three different commission arrangements—

upfront, hybrid and level. We excluded no commission and salaried

employment arrangements because the percentage of insurers’ distribution

channels that were remunerated in this way was extremely small, at less than

2%: see Figure 5.

Figure 15: Lapse rates by remuneration arrangement for stepped premium policies

20

APRA, Insight, Issue 3, 2013, p. 37.

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%