/13,".%3"3&.*5&12*38/13,".%3"3&.*5&12*38

$)/,"1 $)/,"1

*22&13"3*/.2".%)&2&2 *22&13"3*/.2".%)&2&2

.3&10&12/.",/.;*$3".%-0,/8&&&,,&*.()&.3&10&12/.",/.;*$3".%-0,/8&&&,,&*.()&

/%&1"3*.(/,&/'&$/5&1870&1*&.$&2/%&1"3*.(/,&/'&$/5&1870&1*&.$&2

"*3,*...&-2+8

/13,".%3"3&.*5&12*38

/,,/63)*2".%"%%*3*/.",6/1+2"3)33020%72$)/,"1,*#1"180%7&%4/0&.!"$$&22!&3%2

&342+./6)/6"$$&223/3)*2%/$4-&.3#&.&:328/4

&$/--&.%&%*3"3*/.&$/--&.%&%*3"3*/.

&-2+8"*3,*....3&10&12/.",/.;*$3".%-0,/8&&&,,&*.()&/%&1"3*.(/,&/'&$/5&18

70&1*&.$&2

*22&13"3*/.2".%)&2&2

"0&1

)3302%/*/1(&3%

)*2)&2*2*2#1/4()33/8/4'/1'1&&".%/0&."$$&223)"2#&&."$$&03&%'/1*.$,42*/.*.*22&13"3*/.2".%

)&2&2#8"."43)/1*9&%"%-*.*231"3/1/' $)/,"1,&"2&$/.3"$342*'6&$".-"+&3)*2%/$4-&.3-/1&

"$$&22*#,&0%72$)/,"10%7&%4

Interpersonal Conflict and Employee Well-Being:

The Moderating Role of Recovery Experiences

by

Caitlin Ann Demsky

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Science

in

Psychology

Thesis Committee:

Charlotte Fritz, Chair

Leslie Hammer

Robert Roeser

Portland State University

©2012

i

Abstract

Recovery during nonwork time is essential for restoring resources that have been

lost throughout the working day (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Recent research has begun to

explore the nature of recovery experiences as boundary conditions between various job

stressors and employee well-being (Kinnunen, Mauno, & Siltaloppi, 2010; Sonnentag,

Binnewies, & Mozja, 2010). Interpersonal conflict is an important work stressor that has

been associated with several negative employee outcomes, such as higher levels of

psychosomatic complaints (Pennebaker, 1982), anxiety, depression, and frustration

(Spector & Jex, 1998). This study contributes to recovery research by examining the

moderating role of recovery experiences on the relationship between workplace

interpersonal conflict and employee well-being. Specifically, it was hypothesized that

recovery experiences (e.g., psychological detachment, mastery, control, relaxation,

negative work reflection, positive work reflection, and social activities) would moderate

the relationship between interpersonal conflict and employee well-being (e.g., job

satisfaction, burnout, life satisfaction, and general health complaints). Hierarchical

regression was used to examine the hypotheses. Relaxation was found to be a significant

moderator of the relationship between self-reported interpersonal conflict and employee

exhaustion. Additional analyses found mastery experiences to be a significant moderator

of the relationship between coworker reported interpersonal conflict and both dimensions

of burnout (exhaustion and disengagement). Several main relationships between recovery

experiences and employee well-being were found that support and extend earlier research

on recovery from work. Practical implications for future research are discussed.

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my committee for their insightful comments and suggestions that

have helped strengthen my thesis project. Without your input and expertise, this

document would not be what it is today. In particular, I would like to thank my advisor,

Charlotte Fritz, for providing me with invaluable assistance and advice over the course of

this project. I would also like to thank my cohort and classmates for their emotional

support, feedback, and help over the past year. Finally, I would like to thank my family

and friends for their continued support of my educational pursuits.

iii

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................... i

Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. ii

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iv

List of Figures .................................................................................................................... vi

Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1

Interpersonal Conflict at Work ................................................................................3

Recovery from Work Demands ...............................................................................8

Specific Recovery Experiences..............................................................................17

Work-Related Well-Being .....................................................................................25

General Well-Being ...............................................................................................28

Interpersonal Conflict and Employee Well-Being .................................................29

Recovery Experiences as Potential Moderators .....................................................32

Method ..............................................................................................................................45

Procedure ...............................................................................................................45

Participants .............................................................................................................48

Measures ................................................................................................................48

Results ...............................................................................................................................54

Preliminary Analyses .............................................................................................54

Hypothesis Testing.................................................................................................56

Hypothesis 1...........................................................................................................57

Hypothesis 2...........................................................................................................57

Hypothesis 3...........................................................................................................58

Hypothesis 4...........................................................................................................59

Hypothesis 5...........................................................................................................59

Hypothesis 6...........................................................................................................60

Hypothesis 7...........................................................................................................60

Additional Analyses ...............................................................................................61

Discussion .........................................................................................................................64

Implications............................................................................................................70

Contributions and Limitations ...............................................................................71

Future Research .....................................................................................................75

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................77

Tables ................................................................................................................................78

Figures ...............................................................................................................................95

References .......................................................................................................................102

Appendix: Survey Items ..........................................................................................117

iv

List of Tables

Table 1: Table of Variables and Measurement Scales ......................................................78

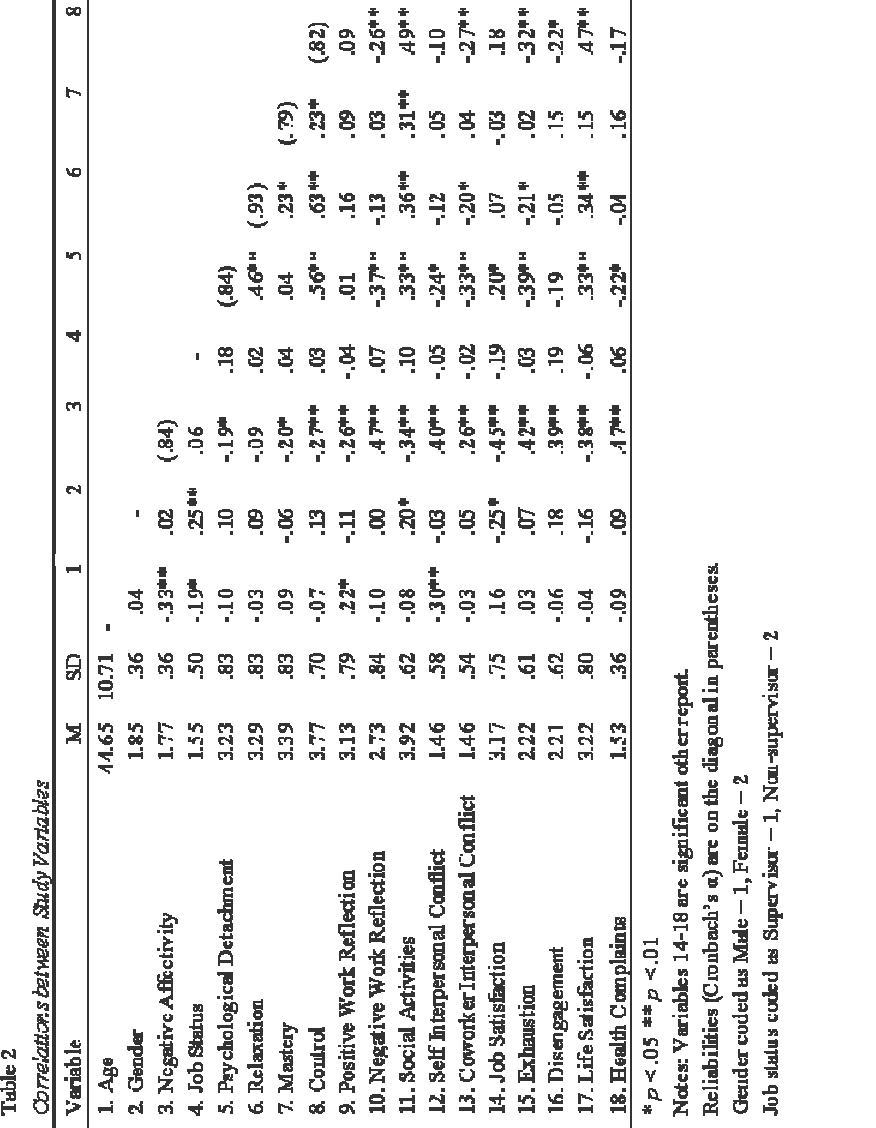

Table 2: Correlations between Study Variables ...............................................................79

Table 3: Hierarchical Regression Results for Psychological Detachment as a Moderator

of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-Being ........81

Table 4: Hierarchical Regression Results for Psychological Detachment as a Moderator

of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being .................82

Table 5: Hierarchical Regression Results for Relaxation as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-Being ..................83

Table 6: Hierarchical Regression Results for Relaxation as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being ...........................84

Table 7: Hierarchical Regression Results for Mastery Experiences as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-Being Outcomes .85

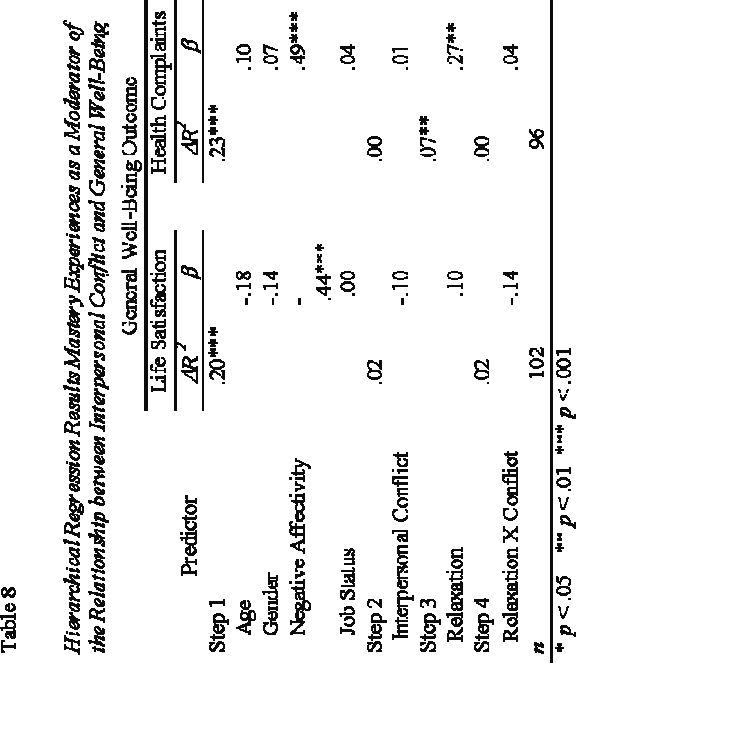

Table 8: Hierarchical Regression Results for Mastery Experiences as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being ...........................86

Table 9: Hierarchical Regression Results for Control as a Moderator of the Relationship

between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-Being ........................................87

Table 10: Hierarchical Regression Results for Control as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being ...........................88

Table 11: Hierarchical Regression Results for Social Activities as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-Being ..................89

Table 12: Hierarchical Regression Results for Social Activities as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being ...........................90

Table 13: Hierarchical Regression Results for Positive Work Reflection (PWR) as a

Moderator of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-

Being .................................................................................................................................91

Table 14: Hierarchical Regression Results for Positive Work Reflection (PWR) as a

Moderator of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being

............................................................................................................................................92

Table 15: Hierarchical Regression Results for Negative Work Reflection (NWR) as a

Moderator of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Work-Related Well-

Being .................................................................................................................................93

v

Table 16: Hierarchical Regression Results for Negative Work Reflection (NWR) as a

Moderator of the Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and General Well-Being

............................................................................................................................................94

vi

List of Figures

Figure 1: Hypothesized Model of the Relationship between Relationships between

Interpersonal Conflict and Well-Being with Recovery Experiences as Moderators ........95

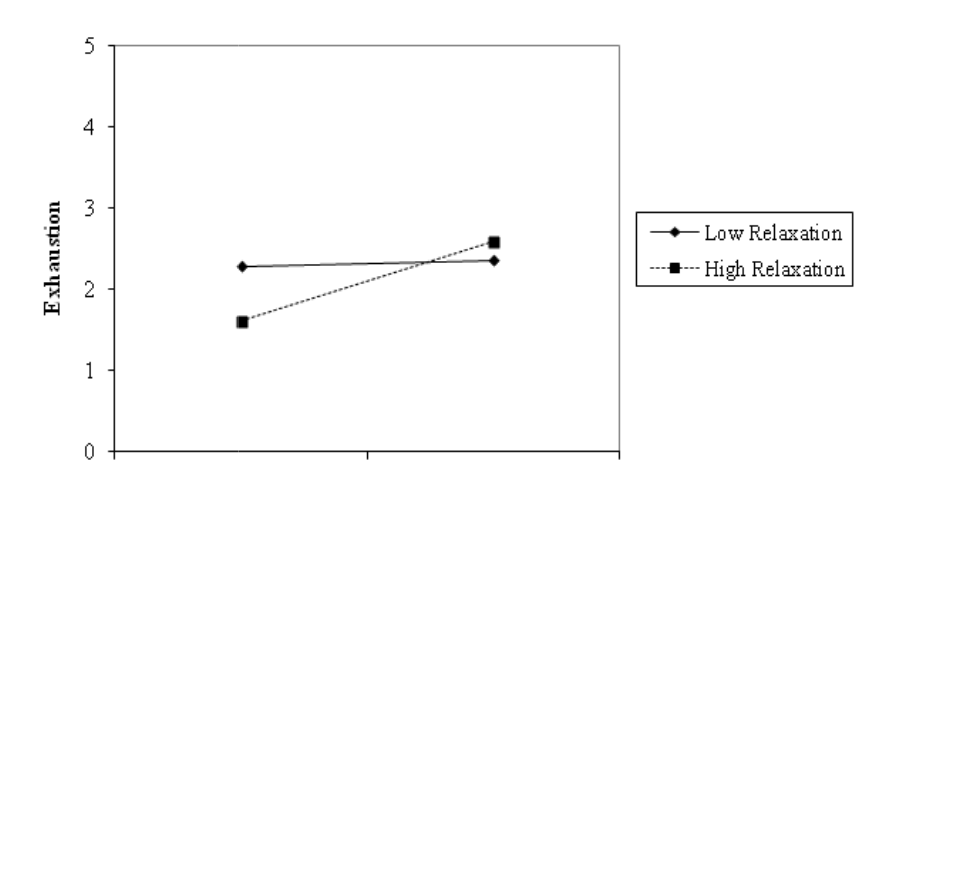

Figure 2: Relaxation as a Moderator of the Relationship between Self-Reported

Interpersonal Conflict and Exhaustion .............................................................................96

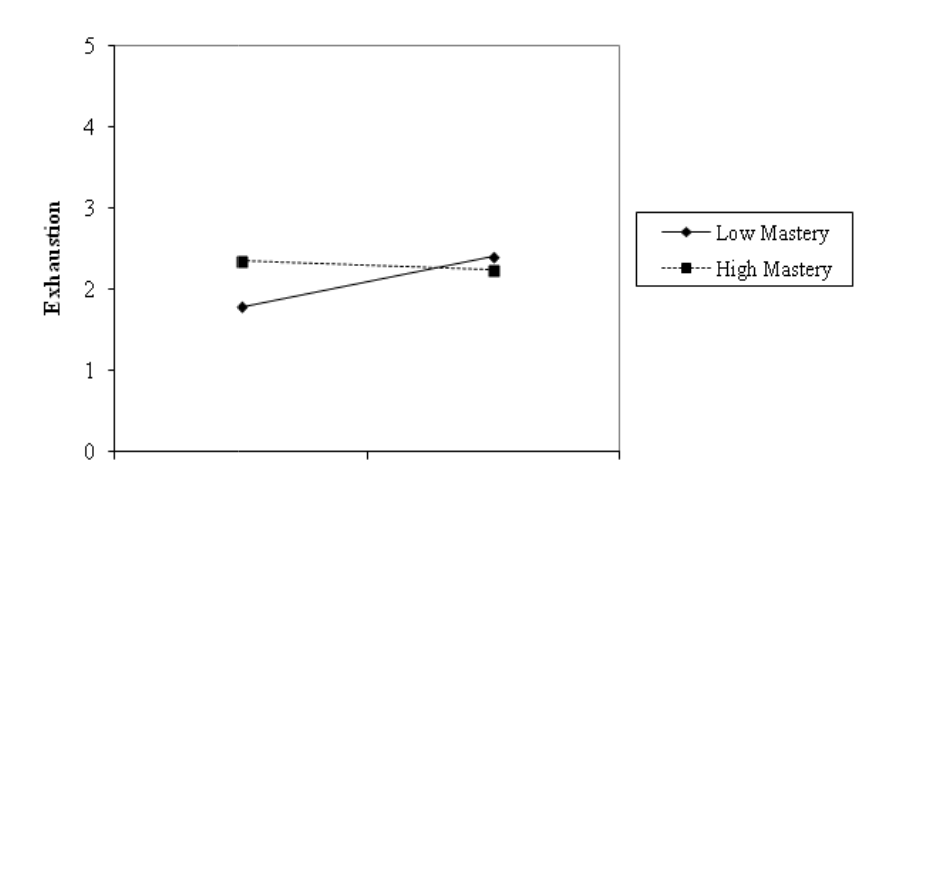

Figure 3: Additional Analyses: Mastery Experiences as a Moderator of the Relationship

between Coworker-Reported Interpersonal Conflict and Exhaustion ..............................97

Figure 4: Additional Analyses: Mastery Experiences as a Moderator of the Relationship

between Coworker-Reported Interpersonal Conflict and Disengagement ........................98

Figure 5: Additional Analyses: Psychological Detachment as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Coworker-Reported Interpersonal Conflict and Exhaustion

(Controlling for Age, Gender, and Job Status) ..................................................................99

Figure 6: Additional Analyses: Psychological Detachment as a Moderator of the

Relationship between Coworker-Reported Interpersonal Conflict and Disengagement

(Controlling for Age, Gender, and Job Status) ................................................................100

Figure 7: Additional Analyses: Relaxation as a Moderator of the Relationship between

Coworker-Reported Interpersonal Conflict and Life Satisfaction (Controlling for Age,

Gender, and Job Status) ...................................................................................................101

1

Interpersonal Conflict and Employee Well-Being:

The Moderating Role of Recovery Experiences

In today’s fast-paced society, it is common to interact with numerous individuals

throughout a workday, including supervisors, coworkers, and customers. While one may

hope that each of these interactions is pleasant and meaningful, this is not always the

case. For various reasons, employees who interact with a variety of people throughout the

workday may occasionally experience interpersonal conflict at work. Interpersonal

conflict at work is a common source of work stress that can be associated with adverse

outcomes for its victims. Most commonly, interpersonal conflict at work manifests itself

in petty arguments, spreading rumors, and gossiping (Spector & Jex, 1998). More

specifically, interpersonal conflict has been defined by researchers as an organizational

stressor consisting of disagreements between individuals in the workplace (Spector &

Jex, 1998). Conflict in the workplace can create hostile environments that add additional

demands for employees. Victims of interpersonal conflict at work often use emotion

regulation and rational thinking to cope with feelings of frustration and anger that arise

from the conflict. These strategies may leave them feeling drained and unable to cope

with additional demands at work or at home (Grandey, 2000).

Past research has indicated several negative outcomes associated with

interpersonal conflict at work. For example, experienced interpersonal conflict at work is

related to higher levels of anxiety, depression, frustration, and intention to quit (Spector

& Jex, 1998). These findings suggest that interpersonal conflict is associated with

substantial negative outcomes for employees. While it is important that organizations

2

address interpersonal conflict in the workplace, it is also essential that employees who

encounter conflict at work have strategies that facilitate their ability to cope with the

conflict. Much of the research surrounding interpersonal conflict has focused on

identifying antecedents and outcomes, however, few studies have offered suggestions for

possible strategies to ameliorate the negative impacts of interpersonal conflict at work. It

can be assumed that even in the case of an organization that has been proactive in

eliminating interpersonal conflict, these contentious encounters are often inevitable.

One possible way for employees to lessen potential negative impacts of

workplace stressors is to intentionally spend time recovering from work during nonwork

time. Several specific recovery experiences have been identified as ways for individuals

to recover from work stress (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Through recovery from work

individuals are able to separate themselves from work demands, enabling them to return

to work feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. In the context of interpersonal conflict at

work, recovery may lessen the possible negative impacts of workplace conflicts. For

example, mentally distancing oneself from work may help individuals disengage from the

conflict they experienced at work that day. Similarly, spending time with others outside

of work may allow individuals to seek social support from friends and family.

The current study is an examination of the relationship between interpersonal

conflict and employee well-being outcomes. Specifically, I focus on well-being outcomes

that are both job-related (job satisfaction and burnout) and general (life satisfaction and

general health). In line with past research, I propose that there will be negative

relationships between interpersonal conflict and indicators of well-being. However, this

3

study moves beyond previous research by examining recovery experiences as possible

moderators of the relationship between workplace interpersonal conflict and employee

well-being. The results of this study will provide insights for individuals dealing with

interpersonal conflict at work, as well as for organizations seeking to implement

interventions to counteract the negative associations between interpersonal conflict and

employee well-being.

Interpersonal Conflict at Work

Job stressors. There is a substantial body of research dedicated to examining the

various employee-level effects of job stressors. Individuals monitor and appraise events

in their environment (Lazarus, 1991). Events that are seen as threats to well-being are

considered job stressors and may induce negative emotional reactions like anger or

anxiety (Spector, 1998). Various workplace conditions have been identified as job

stressors, including role conflict and ambiguity (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, &

Rosenthal, 1964), situational constraints (Peters & O’Connor, 1980), low autonomy

(Spector, 1986), and workload (Spector, 1987). These work stressors have been

associated with a variety of employee outcomes, including both job performance and

well-being. Additionally, as will be described below, interpersonal conflict is another job

stressor that has received attention in the research literature (Spector & Jex, 1998).

Workplace interpersonal conflict. Interpersonal conflict at work can manifest

itself in several ways, and can range in severity from spreading rumors to physical

assault. Conflict at work can consist of covert behaviors that are indirect and less

4

identifiable, or overt behaviors with very direct and obvious intentions (Spector & Jex,

1998). While a wide variation of interpersonal conflict may be found across and within

organizations, the majority of interpersonal conflicts include petty arguments and gossip,

and not actual physical attacks (Schat, Frone, & Kelloway, 2006). Regardless of the

interpersonal conflict manifestation, can elicit anger and frustration in employees who

encounter it (Keenan & Newton, 1985). As a result, employees who encounter

interpersonal conflict at work may have difficulties disengaging from thoughts of the

conflict and may ruminate about the experience even after leaving the workplace at the

end of the day. They may also be less engaged in their work out of fear of future

conflicts. Over time, these continued thoughts of the experienced conflict may lead to

detrimental outcomes for employees, such as higher levels of anxiety, frustration, and

burnout (De Dreu, Dierendonck, & Dijkstra, 2004b).

While the current study utilizes Spector and Jex’s (1998) explanation of

interpersonal conflict, it is important to consider other operationalizations of the

construct. Past research has examined various forms of conflicts in the workplace, using

terms such as incivility, bullying, aggression, and counterproductive work behaviors

(e.g., Schat et al., 2006; Bowling & Beehr, 2006; Barling, Dupre, & Kelloway, 2009;

Hershcovis & Barling, 2009; Hershcovis, 2011). Barki and Hartwick (2004) note that

even within studies pertaining explicitly to interpersonal conflict, researchers rarely agree

on one single definition of interpersonal conflict, or avoid defining the construct

altogether. Barki and Hartwick (2004) define interpersonal conflict as “a dynamic process

that occurs between interdependent parties as they experience negative emotional

5

reactions to perceived disagreements and interference with the attainment of their goals”

(p. 234). Additionally, they discuss three general themes used to describe conflict:

disagreement, interference, and negative emotion. Each of these three themes is thought

to represent cognitive, behavioral, and affective manifestations of conflict, respectively.

Disagreement occurs when parties involved think that a divergence of needs, thoughts,

opinions, or goals exists. Interference occurs when one party’s behaviors interfere with,

or oppose another party’s attainment of its own objectives, needs, or goals. Lastly,

negative emotions such as fear, jealously, anger, anxiety, and frustration have been used

to characterize interpersonal conflict.

Several organizational and individual factors have been linked to increased

incidents of interpersonal conflict in the workplace. The Dollard-Miller frustration-

aggression theory (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer & Sears, 1939) suggests that

frustration occurs when an instigated goal sequence or behavioral sequence is interrupted.

When this occurs an individual may respond with aggression, especially when a

substitute response for the prevented goal sequence is not available. Later research

expanded the theory by including the mediating presence of an emotional reaction

(Spector, 1978; Spielberger, Reheiser & Sydeman, 1995). In this expanded model, the

frustration of a task performance or personal goal by one of a number of possible sources

(e.g., supervisors, subordinates, coworkers, procedures, or formal structure) leads to an

emotional response of frustration or anger. These emotional reactions are associated with

behavioral outcomes, with severe frustration and no expectation of punishment being

6

linked to organizational and interpersonal aggression, as well as eventual withdrawal and

goal abandonment.

Fox and Spector (1999) proposed a theoretical model of counterproductive work

behaviors pertaining to interpersonal and organizational aggression, which is relevant in

the current context of interpersonal conflict. The work of Fox and Spector (1999)

expands the original Dollard-Miller frustration-aggression theory, by including both

emotional and behavioral reactions to frustration. In the work context, certain stressors,

such as situational constraints, may serve to block an intended organizational goal,

causing individuals to become frustrated (Peters & O’Connor, 1980). Behavioral

reactions to frustration on the job, pertinent to the current study, include lowered job

performance, absenteeism, turnover, and both organizational and interpersonal aggression

(Spector, 1978). Accordingly, Fox and Spector (1999) found that events in the workplace

(e.g., situational constraints) were related to organizational counterproductive behaviors

(including workplace aggression) and were mediated by affective responses to

frustration.

Spector and Jex (1998) conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies utilizing the

Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale. The results of this meta-analysis demonstrated that

interpersonal conflict at work was most strongly related to several job stressors (e.g., role

conflict, role ambiguity, and low autonomy). This meta-analysis further supports the

model of frustration-aggression presented by Fox and Spector (1999), which suggests that

situational constraints as well as individual factors contribute to affective and behavioral

reactions, one of which is increased interpersonal aggression.

7

Affective events theory. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) posited affective events

theory (AET) as an alternative explanation to theories that focus on satisfaction with

one’s job as an evaluative judgment process. Instead, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996)

argue that job satisfaction is a consequence of affective events in the workplace that

direct attention away from features of the work environment and toward events or

proximal causes of affective reactions. Additionally, they suggest that patterns of affect

will influence both overall feelings about one’s job as well as discrete work behaviors.

Importantly, AET also acknowledges the multidimensional nature of affect—employees

can feel angry, proud, frustrated, or joyful. Each of these different reactions has different

behavioral implications in the workplace.

At the core of AET are affective reactions, which occur in response to work

events. These affective reactions can be influenced by one’s disposition, and lead to both

attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Affective reactions to workplace events influence

work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction). Behavioral outcomes are grouped into two

categories: affect driven behaviors and judgment driven behaviors. Affect driven

behaviors follow directly from affective reactions and are influenced by processes like

coping and mood management (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Judgment driven behaviors,

on the other hand, are mediated by satisfaction.

In the context of workplace interpersonal conflict, AET is useful for explaining

the potential linkage between interpersonal conflict and job satisfaction, one of the

several dependent variables in the current study. Experiencing conflict would be one

work event that would elicit an affective reaction. This affective reaction would in turn

8

lead to attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. The attitudinal outcomes may include

lowered levels of job satisfaction, frustration, or anger.

Recovery from Work Demands

Recovery from work refers to a process during which individual functional

systems that have been called upon during the workday return to their prestressor levels

(Meijman & Mulder, 1998). Recovery can be described as a psycho-physiological

process (Meijman & Mulder, 1998), and has been conceptualized as being the opposite of

the strain process, in which prolonged activation results in stress reactions. During

recovery from work (e.g., during evenings or weekends) employees are able to disengage

from work demands and focus on nonwork activities, which allow time for emotional and

cognitive systems that were activated during work to restabilize. One’s personal

resources (e.g., feelings of self-efficacy, energy, etc.) are depleted throughout the

workday in response to work demands. It is essential that employees engage in recovery

experiences during nonwork time so that resources exhausted throughout the workday

can be regenerated. Recovery is necessary for one’s health and well-being, as prolonged

exposure to stressors without sufficient recovery can lead to health deterioration

(McEwen, 1998). Recovery from work demands can be described in the context of

different theoretical frameworks. Several of these frameworks are described below.

Effort-recovery model. The effort-recovery model (Meijman & Mulder, 1998)

outlines the process of responding to cognitive demands. The model identifies three

determinants: work demands, work potential, and decision latitude. These three factors

together determine two specific outcomes: the work product, and short-term

9

physiological and physical reactions. The work product refers to the goods or services

that are a direct outcome of the work, while short-term reactions are seen as adaptive

responses at the physiological, behavioral, and subjective level, and are manifested as

lowered employee health. When exposure to work stressors ceases, the engaged

psychobiological systems stabilize at pre-stressor levels, a process described as recovery.

When these same systems are called upon outside of work, the opportunity for recovery

is significantly decreased. In these instances, individuals are required to engage in

compensatory mechanisms, further drawing upon reserves of resources. Extended

exposure to work demands without significant time for recovery is therefore assumed to

impair individual well-being.

Conservation of resources theory. Hobfoll’s (1989) conservation of resources

(COR) theory posits that individuals strive to maintain, build, and protect their resources.

Resources are defined as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that an

individual values or that serve as a means for obtaining further objects, energies,

conditions, or personal characteristics (Hobfoll, 1989). Psychological stress occurs in

response to three potential situations: (a) a threat to an individual’s resources, (b) actual

loss of resources, or (c) failure to gain resources after investment of resources.

The COR model identifies four types of resources. Object resources are valuable

due to their actual nature, or their potential to be used as a status symbol (e.g., luxury

items). Personal characteristics can also be seen as resources, in that they aid in the stress

resistance process (e.g., self-efficacy, positive sense of self; Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll &

Lilly, 1993). Building personal characteristic resources may also allow for the

10

development of more resources in other categories. Conditions are subjective resources,

in the sense that they are sought after and valued (e.g., marriage and job seniority).

Lastly, energies (e.g., time, money, and knowledge) are seen as resources in that they aid

in the quest for additional resources.

Resources may be viewed as more or less valuable depending on various

individual, group, and societal factors. Furthermore, various environmental factors may

threaten these resources. The actual or possible loss of resources is seen as a threat

because, at the most basic level, resources are instrumental to individuals, and because

individuals often find self-worth in the resources they have at their disposal. Hobfoll

(1989) argues that loss is central to many of the theories of psychological stress, and

points to numerous studies that have examined significant life events, specifically loss

events, that cause stress (Dohrenwend, 1978; Holmes & Rahe, 1967; Sarason, Johnson, &

Siegel, 1978). Additionally, more ambiguous life events can be seen as stressful in the

extent to which they are perceived as “undesirable.” Furthermore, research indicates that

the loss of resources is much more salient and detrimental to individuals than resource

gains (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993).

The COR model predicts that those confronted with stress will seek to minimize

resource loss (Hobfoll, 1989), and those who are not presented with stress will seek to

build and develop new resources, so as to offset the possibility of future resource loss.

When people develop new resources, they may experience positive well-being (Cohen &

Wills, 1985). Those that are unable to build new resources, however, are particularly

11

vulnerable and may be more likely to develop self-protective styles in the hopes of

preventing future resource loss (Arkin, 1981; Cheek & Buss, 198l).

In the context of COR theory, engaging in recovery experiences outside of work

allows individuals to restore resources that were lost while at work. It is also possible that

some recovery experiences may allow one to build new resources, which is a key feature

of COR theory. For example, taking time to relax after work may allow individuals to

restore emotional energy that was depleted during a particularly trying day at work. The

same may be said for cognitive resources that were called upon during the workday.

While employees may feel exhausted at the end of the workday, which would signal a

decreased level of resources, taking time to relax, detach from work, or engage in social

activities with friends and family may leave one feeling rejuvenated by the end of the

evening. Additionally, particular recovery strategies entail engaging in learning

experiences (e.g., mastery experiences), which offer the opportunity for building new

resources. For example, learning a new language or rock climbing during nonwork time

may facilitate the development of a new skill or the increase of such personal resources

as self-efficacy and a positive sense of self.

Ego depletion model. Past research on recovery from work has also included the

concept of ego depletion. The theory of ego depletion assumes that the self’s various acts

of volition draw on a similar limited resource, such that acts of volition will have a

negative impact on subsequent acts of volition (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, &

Tice, 1998). Baumeister and colleagues (1998) found support for this explanation over

the course of four unique experiences. In each of these cases, individuals who were

12

required to exert self-control and conscious acts of volition were more likely to give up or

persist for a shorter period of time on subsequent tasks than those who were not required

to exert self-control. Additional support for the ego depletion model has been

demonstrated for cases in which participants are asked to regulate and suppress emotional

responses. Those who were asked to regulate and control their emotions were again

linked to subsequent decreases in physical stamina (measured by the length of time

participants could continuously squeeze a handgrip) and the ability to regulate further

emotional responses (Muraven, Tice, & Baumeister, 1998).

Ego depletion is relevant to the process of recovery from work, such that reacting

to work stressors may require conscious acts of volition (e.g., engagement in a work

task). The acts of volition in response to these stressors reduce one’s self-regulatory

resources, which in turn may impair subsequent acts of volition (e.g., decreased effort in

the second task). The lack in self-control may also impair individual well-being (e.g.,

increased levels of fatigue, burnout, etc.). By engaging in recovery experiences,

employees are able to rebuild the resources that were lost by engaging in multiple acts of

volition during the workday. For example, by relaxing or mentally distancing oneself

from work, an individual is able to regain self-regulatory resources necessary for work.

Mood regulation. Recovery from work also provides opportunities to restore

positive affect that may have been diminished during the workday as a result of various

work stressors. One’s ability to self-regulate mood is crucial to maintaining social

relationships, particularly under stressful situations. For example, Larsen (2000)

13

describes mood regulation as a series of control processes in which individuals act

directly to control their mood.

Some research has suggested that mood repair may be one of the core functions of

recovery (Fuller, Stanton, Fisher, Spitzmuller, Russell, & Smith, 2003). Individuals may

undertake various strategies in the process of mood regulation, including both cognitive

and behavioral approaches (Parkinson, Totterdell, Briner, & Reynolds, 1996; Thayer,

Newman, & McClain, 1994). Parkinson and Totterdell’s (1999) research on mood

regulation strategies provides insight into the ways in which individuals actively seek to

control their moods. Two particular types of strategies were suggested by Parkinson and

Totterdell (1999): diversionary and engagement strategies. Diversionary strategies

involve avoiding negative and stressful situations and seeking distractions from such

situations (e.g., relaxation-oriented, pleasure-oriented, or mastery-oriented experiences).

Engagement strategies involve actively confronting or accepting stressful situations. Both

of these forms of engagement strategies involve an affect-directed and situation-directed

component. Diversionary strategies appear to be most related to recovery experiences, as

they allow an individual to disengage from stressful experiences and regain lost

resources. In contrast, engagement experiences may keep individuals cognitively

occupied with stressors, which would lead to continued resource losses (Sonnentag &

Fritz, 2007). This framework is directly relevant to research on recovery from work, as an

active component of recovery is the process of regulating one’s mood and responses to

daily stressors, which will become apparent in employee well-being.

14

Recent research has demonstrated an association between recovery experiences

and emotional states. For example, Fritz, Sonnentag, Spector, and McInroe (2010a) found

that recovery experiences (e.g., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and

control) during the weekend were related to affective states during the following work

week. Specifically, relaxation was associated with increased positive affect and decreased

negative affect during the following work week. Mastery was associated with higher

levels of positive affect at the end of the weekend, and psychological detachment was

associated with positive affective states both at the end of the weekend and at the end of

the following work week. Additionally, a recent diary study by Sonnentag, Binnewies,

and Mozja (2008) found an association between a lack of psychological detachment in

the evening and negative activation and fatigue the following morning. On the other

hand, evening relaxation was associated with morning serenity, and mastery experiences

in the evening were related to positive activation in the morning.

Mechanisms linking work and nonwork domains. While it is necessary to

discuss in detail the several theoretical frameworks used to support the notion of recovery

during nonwork time, it is also important to acknowledge work being done in the area of

work-family research that offers alternative explanations for the impacts of work on

home life. Edwards and Rothbard (2000) discuss several mechanisms that link the work

and family domains. They define a linking mechanism as “a relationship between a work

construct and a family construct. Linking mechanisms can exist only when work and

family are conceptually distinct” (p. 180). The six general categories of linking

mechanisms include: spillover, compensation, segmentation, resource drain, congruence,

15

and work-family conflict. These linking mechanisms are relevant to the research being

done on recovery from work, as several of these mechanisms may be useful for

explaining the necessity of recovery during nonwork time.

Spillover refers to effects of work and family on one another that generate

similarities between the two domains (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000), and consists of two

versions: one in which spillover is characterized as a similarity between a work domain

construct and a distinct but related family domain construct, and another version in which

spillover consists of experiences between domains. This spillover between domains can

be either positive or negative. Recovery from work may be increasingly necessary in

situations of negative spillover to prevent negative experiences in one domain from

affecting the other domain as well. For example, recovery after work may prevent

increased levels of fatigue due to work from negatively impacting one’s involvement in

family domain activities. In their recent chapter on the quality of work life, Hammer and

Zimmerman (2010) provide an overview of positive spillover and health outcomes.

Work-family positive spillover has been linked with lower risks of mental illness,

depression, and problem drinking. Furthermore, Hammer and Zimmerman point out

recovery from work as a new direction in the work-family field. While spillover is

particularly relevant to the concept of recovery from work, there are several other linking

mechanisms that may be important as well.

Compensation, another linking mechanism, consists of efforts to offset

dissatisfaction in one domain by seeking satisfaction in another domain, and comes in

two forms: the reallocation of importance, and supplemental compensation. Recovery

16

from work may be particularly relevant to this second type of compensation, in which

individuals seek to engage in recovery experiences as a way of offsetting less than

satisfactory work experiences. Segmentation refers to “an active process whereby people

maintain a boundary between work and family” (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000, p. 181).

This linking mechanism may be most relevant to the process of mentally and physically

distancing oneself from work during nonwork time in an attempt to disengage from work

demands. Resource drain is another linking mechanism that refers to the transfer of

personal resources (e.g., time, attention, energy) from one domain to another. Recovery

from work may decrease employees’ experience of resource drain, as engaging in

recovery experiences allows for the rebuilding of resources necessary for both work and

family domains. Congruence, another linking mechanism, refers to the “similarity

between work and family, owing to a third variable that acts as a common cause” (p.

182). For example, overarching life values or general aptitudes and intelligence may

affect both the work and family domains. Lastly, work-family conflict refers to a form of

interrole conflict in which the demands of work and family are incompatible, in which

meeting the demands of one domain makes it difficult to meet demands in the other

domain. Work-family conflict has been separated into three forms: time-based, strain-

based, and behavior-based (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). In this context, recovery from

work may be most relevant to forms of strain-based work-family conflict. Strain-based

work-family conflict refers to a process by which strain (e.g., dissatisfaction, anxiety,

fatigue) from one domain makes it difficult to meet demands of the other domain. By

engaging in recovery experiences during nonwork time, employees may be able to lessen

17

the detrimental outcomes associated with work demands, thereby allowing for increased

resources to be allocated to the family domain.

Specific Recovery Experiences

Various experiences outside of the work domain have been suggested to

contribute to recovery from work. Building on past research on recovery from work I will

focus on several specific recovery experiences that will be described in more detail

below.

Psychological detachment. Psychological detachment can be described as

physically and mentally separating oneself from the working environment. Detachment

can result from the simple physical act of leaving work and going home, or refraining

from thinking about work-related problems or issues while at home (Sonnentag & Fritz,

2007). In the context of the effort-recovery model, psychological detachment may help

individuals restore resources lost while at work. After work, it is important that the same

systems that were activated by work stressors are no longer called upon, so that an

individual’s psychobiological systems are able to return to prestressor levels. By

psychologically detaching from work, an individual is no longer exposed to the demands

of various work stressors, and is able to recover the resources that were lost in response

to the work demands of that day. Additionally, in accordance with the theory of mood

regulation, psychologically detaching from work can allow individuals to remove

themselves from work situations associated with negative emotions.

Several empirical studies have suggested that psychological detachment from

work during nonwork time is an important factor in recovery from work demands.

18

Psychological detachment from work has been linked to positive mood and low fatigue in

the evening before bedtime and the next morning (Sonnentag & Bayer, 2005; Sonnentag

et al., 2008). Psychological detachment has also been linked to lower levels of health

complaints, emotional exhaustion, depressive symptoms, need for recovery, and sleep

problems and higher levels of life satisfaction (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). A recent study

also found that higher levels of self-reported psychological detachment were associated

with higher levels of significant-other reported life satisfaction and lower levels of

emotional exhaustion (Fritz, Yankelevich, Zarubin, & Barger, 2010b). Additionally, low

levels of psychological detachment were associated with high levels of emotional

exhaustion and need for recovery, and also partially mediate the relationship between job

stressors and strain reactions (Sonnentag, Kuttler, & Fritz, 2010). Psychological

detachment during the weekend has also been associated with certain aspects of positive

affect during the following workweek (e.g., joviality and serenity; Fritz et al., 2010a).

Relaxation. Relaxation is associated with low activation and positive affect

(Stone, Kennedy-Moore, & Neale, 1995), and can result from various leisure activities,

including meditation, a light walk, or casual social activities. According to COR theory,

individuals strive to maintain, build, and protect their resources (Hobfoll, 1989).

Relaxation as a recovery experience is helpful for those individuals who are in need of

maintaining and protecting their resources, particularly after having lost resources at

work. In this case, relaxation may expedite the process by which systems that were

activated by work stressors return to prestressor levels. Relaxation may also foster mood

regulation, as engaging in relaxation after work may help reduce high activation negative

19

affect (e.g., anger) that may have resulted as a response to various work stressors.

Through relaxation experiences such as taking a walk or reading a book, an individual

may be able to both reduce negative mood as well as restore positive mood.

Relaxation during nonwork time has been linked to lower levels of health

problems, emotional exhaustion, need for recovery, and sleep problems and higher levels

of life satisfaction (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). In addition, Sonnentag and colleagues

(2008) showed that higher levels of relaxation in the evening were related to serenity the

following morning. Keeping in line with mood regulation theory, relaxation during the

weekend has also been associated with higher levels of joviality, self-assurance, and

serenity and lower levels of fear, hostility, and sadness at the end of the weekend as well

as at the end of the following work week (Fritz et al., 2010a).

Mastery. Engaging in mastery experiences is another form of recovery during

which an individual seeks to build new internal resources. This may be accomplished by

seeking out new and challenging activities and learning experiences (Sonnentag & Fritz,

2007). Mastery experiences are assumed to challenge the individual without overtaxing

his or her capabilities (Siltaloppi, Kinnunen, & Feldt, 2009). While these mastery

experiences may put additional demands on the individual, they also enhance recovery by

allowing for the development of new resources such as skills, competencies, and self-

efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Hobfoll, 1998). Mastery experiences would allow individuals to

build new resources of their own choosing. These additional resources are helpful in

confronting subsequent stressors, and in many cases, may increase an individual’s

feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy. Engaging in mastery experiences during nonwork

20

time may also allow individuals to regulate their mood, particularly in response to

negative affective states that may have been elicited by interpersonal conflicts at work.

Mood regulation theory posits that individuals are able to actively engage in strategies in

the process of mood regulation, and mastery experiences typify an engagement strategy

in which individuals select activities that will increase positive affect and feelings of self-

efficacy.

Mastery experiences during vacation have been found to be negatively related to

exhaustion after vacation (Fritz & Sonnentag, 2006). Mastery has also been shown to be

negatively related to emotional exhaustion, depressive symptoms, and need for recovery,

and positively related to life satisfaction (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Furthermore, mastery

experiences during the weekend have been associated with higher levels of positive affect

(e.g., joviality, self-assurance, and serenity) at the end of the weekend (Fritz et al.,

2010a).

Nonwork control. Nonwork control refers to an individual’s ability to decide

what leisure experiences he or she will partake in during recovery from work (Sonnentag

& Fritz, 2007). Control over one’s recovery experiences may be particularly important

for mood regulation. As Parkinson and Totterdell (1999) describe, there are various

strategies individuals engage in to change their own moods in response to particular

situational experiences. As diversionary strategies have been suggested as being most

related to recovery experiences (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007), it is possible that engaging in

control over one’s recovery experiences will allow an individual to select activities that

elicit recovery experiences that will be most helpful in improving one’s mood. In

21

addition, while diversionary strategies should be most related to recovering from work

experiences, it is also possible that control is utilized to engage in other recovery

experiences that are more related to engagement strategies as a means of coping with the

negative outcomes of workplace stressors. As individuals strive to maintain and protect

resources, engaging in control over one’s experiences may allow an individual to target

specific resources for rebuilding, which will prevent future resource loss.

Control over one’s experiences allows for a positive reevaluation of potentially

stressful situations and has been found to be positively related to individual well-being

(Lazarus, 1966; Bandura, 1997). Conversely, low levels of control have been linked to

psychological distress and anxiety (Rosenfield, 1989). In situations of low control, one’s

ability to react to and influence the surrounding environment is diminished, which may in

turn lead to negative self-evaluations and lowered self-worth. For example, research by

Griffin, Fuhrer, Stansfeld, and Marmot (2002) indicates that women who had low levels

of control at home experienced higher levels of depression five years later than women

high in control. Similarly, men low in control at home showed higher depression and

anxiety levels than men with high levels of control (Griffin et al., 2002).

Control during leisure time may satisfy an individual’s need for control, and in

turn increase feelings of self-efficacy and competence (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). It is

also possible that control over leisure experiences allows individuals to select recovery

experiences that will be most helpful for the restoration of resources. Sonnentag and Fritz

(2007) demonstrated links between control and lower levels of health complaints,

22

emotional exhaustion, depressive symptoms, need for recovery, and sleep problems, and

higher levels of life satisfaction.

Social activity during nonwork time. Engaging in social activities includes

meeting new people and spending time with friends and family. Social activities offer an

opportunity to seek and receive social support from others (Sonnentag, 2001). Engaging

in social activities may allow individuals to halt the process of resource loss that occurs

in response to work stressors. Engaging in positive social activity may also allow

individuals to regain emotional resources through social support from friends and family.

This gain in resources will bolster reactions to future threats of resource loss. It is also

likely that various social activities result in the creation of new resources (e.g., self-

esteem, extended social network), which also helps individuals to cope with future

resource threats and losses. Furthermore, in line with mood regulation theory, engaging

in social activities with friends and family allows individuals to regulate their moods in

such a way that increases positive affect. Engaging in pleasant activities with social

contacts allows an individual to disengage from work and possible negative impacts of

interpersonal conflict at work.

Seeking social support is beneficial for individual health (Viswesvaran, Sanchez,

& Fisher, 1999), and can serve as a vehicle to replenish one’s depleted physical and

emotional resources (Westman, 1999). Research further suggests that engaging in social

activities with friends and family may call for less self-regulation than engaging in social

interactions with coworkers, supervisors, or customers (Grandey, 2000). Nonwork

experiences such as social activity have also been associated with positive individual

23

outcomes. Fritz and Sonnentag (2005) found positive relationships between social

activities on the weekend and well-being at the beginning of the following work week.

Engaging in social activities in the evening after work has also been associated with

higher levels of well-being before going to sleep (Sonnentag, 2001).

Work reflection. Reflecting on one’s work has been examined as another

potential recovery experience. Fritz and Sonnentag (2005) specifically examined positive

work reflection, which refers to reflecting on one’s job in a positive way during nonwork

time. Engaging in positive work reflection may act as a type of reappraisal of stressful

work situations (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In positively reappraising work, stress

reactions may be reduced, which leads to the restoration of resources. Additionally,

positively reflecting on one’s work allows an employee to focus on the positive aspects of

the job, and the things that one enjoys about their work. Thus, it may allow for the

creation of new resources, or the increase of existing resources. For example, thinking

about the work goals that one has already accomplished may lead to greater self-efficacy,

which in turn may be associated with increased well-being (Westman, 1999; Fritz &

Sonnentag, 2005). Positive work reflection may also be related to the development of

new goals concerning an individual’s work.

Fritz and Sonnentag (2005) found that positively reflecting on one’s work over

the weekend significantly and negatively predicted burnout at the beginning of the

following work week. The findings on positive work reflection suggest that it is not only

limited to the work or nonwork domain, but that it may have important implications for

both life domains (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Fritz & Sonnentag, 2005).

24

It may also be the case that individuals reflect negatively on their jobs while away

from work. Contrary to positive work reflection, negative work reflection entails thinking

about the undesirable aspects of one’s job, such as those aspects that are not enjoyable

(Fritz & Sonnentag, 2006). Thinking negatively about one’s job may in turn consume

resources or prevent necessary regeneration processes, which in turn may lead to

decreased well-being and performance (Etzion, Eden, & Lapidot, 1998; Sonnentag &

Bayer, 2005). Negative work reflection during vacation has been shown to be associated

with higher health complaints and exhaustion after vacation (Fritz & Sonnentag, 2006).

Related to negative work reflection, rumination is a particular response style in

which individuals repetitively think about their negative emotions, focus on their

symptoms, and worry about the meaning of their negative emotions (Lyubomirsky,

Caldwell, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Rumination appears to

contribute to feelings of hopelessness for the future and uncertainty. Engaging in negative

work reflection would be very similar to employees ruminating about their work

experience. In the context of mood regulation, negative and positive work reflection can

be seen as examples of engagement strategies. Though engagement strategies are less

indicative of recovery experiences, reflecting on work is an example of actively

confronting and accepting work stressors. Regarding positive work reflection, an

individual may actively accept work stressors as a challenge and use thoughts about work

to develop future work goals and strategies. Conversely, negative work reflection results

in the continued use of resources needed at work, instead of creating strategies or goals

25

for dealing with stressors, or disengaging from them altogether as with diversionary

strategies.

Work-Related Well-Being

As mentioned previously, I will view well-being variables as belonging to one of

two domains: work-related well-being and general well-being. Work-related well-being

will include job satisfaction and burnout, which will be discussed below.

Job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is one of the most widely studied attitudes in

Industrial & Organizational Psychology (Kinicki, McKee-Ryan, Schriesheim & Carson,

2002), and is defined as a multidimensional attitudinal response to one’s job that has

cognitive, affective, and behavioral components (Smith, Kendall & Hulin, 1969; Hulin &

Judge, 2003). Weiss (2002) defined job satisfaction as “a positive (or negative) evaluative

judgment one makes about one’s job or job situation” (p. 175).

Both antecedents and outcomes of job satisfaction have been studied extensively.

For example, self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, internal locus of control, emotional

stability, and negative affect have been linked to job satisfaction (Judge & Bono, 2001;

Siu, Lu, & Cooper, 1999). In the work context, a variety of factors have been linked to

job satisfaction, such as specific job characteristics, pay (Brasher & Chen, 1999), and

justice perceptions (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). Specifically, research has linked

each of the five core characteristics of job tasks (Hackman & Oldham, 1976): skill

variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and task feedback to job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction also seems to be related to more general indicators of well-being,

such as anxiety, depression, burnout, cardiovascular disease, subjective physical illness,

26

strain, higher levels of self-esteem and general mental health (Faragher, Cass, & Cooper,

2005) and sleep problems (Spector, 2006). A meta-analysis focusing on business

outcomes of job satisfaction showed relationships between job satisfaction and customer

satisfaction-loyalty, profitability, productivity, employee turnover, and safety outcomes

(Harder, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis indicated a

modest but significant relationship between job satisfaction and job performance (r = .20;

Judge, Thoreson, Bono, & Patton, 2001; Harrison, Newman, & Roth, 2006). Lastly,

several studies have demonstrated a link between job satisfaction and another outcome

variable of this study, life satisfaction. Generally, individuals who are more satisfied with

their jobs tend to be more satisfied with their life as well, and several possible

explanations (e.g., spillover, compensation, and segmentation) have been given for this

relationship (Spector, 2006).

Burnout. When individuals are exposed to work stressors over a significant

period of time without the opportunity to recover, burnout is often a likely outcome.

Maslach (1982) originally conceptualized burnout as a syndrome affecting service

workers, consisting of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal

accomplishment. Burnout, generally speaking, is a response to chronic work stressors, in

which individuals feel depleted and unable to further cope with work demands.

Subsequent research on burnout has identified two relevant dimensions of

burnout, namely, exhaustion and disengagement (Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou, &

Kantas, 2003). While Maslach’s (1982) initial conceptualization of burnout had important

psychometric and theoretical limitations (Kalliath, 2001), Demerouti’s and colleagues’

27

(2003) revised conceptualization of burnout was not only applicable to a wide range of

occupations, but had stronger theoretical and psychometric properties (e.g., Halbesleben

& Demerouti, 2005). According to Demerouti and colleagues (2003), exhaustion is a

reaction to prolonged exposure to work stressors, and in this context refers to emotional,

physical, and cognitive forms of exhaustion. This definition of exhaustion is similarly

applicable to employees who engage in prolonged physical labor or information

processing. Disengagement is a physical and emotional response that can manifest itself

as distancing oneself from one’s work, or having negative feelings towards one’s work.

The relevant scale measuring disengagement refers to emotions toward the work tasks as

well as to a devaluation and mechanical execution of the work (Demerouti et al., 2003).

According to the effort-recovery model, burnout is a likely outcome of prolonged

activation, specifically when individuals are unable to regain resources that were lost to

dealing with work stressors.

For example, burnout has been found to be associated with a variety of work

stressors. Specifically, burnout has been linked to low levels of perceived control at work,

high levels of role conflict, and work overload (Spector, 2006). It is important to include

burnout in the conceptualization of employee well-being, as it is a likely outcome of

dealing with chronic work stressors, particularly if individuals are lacking an outlet in

which they are able to recover from such stressors.

28

General Well-Being

In addition to the domain of work-related well-being, I will also be addressing

more general indicators of well-being, including life satisfaction and general health

complaints. Both of these constructs will be discussed in more detail below.

Life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is a global indicator of an individual’s

perceptions of their quality of life, and is seen as a cognitive-judgmental aspect of

individual happiness. Each individual assesses his or her own quality of life with a

different and unique set of standards (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985),

meaning that different individuals may place varying levels of importance on different

aspects of life (e.g., health and finances).

Life satisfaction can be seen as a result of satisfaction across various domains, one

of which would include work. As such, it has been positively (Judge & Watanabe, 1993)

associated with job satisfaction. It is important to note that confirmatory factor analyses

did identify the two scales of satisfaction as separate constructs (Judge & Watanabe,

1993). Additionally, a meta-analysis (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998) found a negative

relationship between work-family conflict and life satisfaction further supporting the

notion that life satisfaction is affected by multiple domains. Accordingly, life satisfaction

was shown to be lower among dual-career couples suggesting work can have a significant

impact on one’s level of life satisfaction.

Health complaints. Past research indicates that prolonged exposure to stressors is

associated with decreased levels of physical health. Health complaints have been viewed

as an overall indicator of poor well-being and refer to physical symptoms of stress or

29

minor problems (Watson & Pennebaker, 1989) such as headaches and sleep disturbances.

Chronic work stress has been linked to a number of detrimental health outcomes, such as

heart disease, ulcers, headaches, cancer, and diabetes. Additionally, under high levels of

work stressors, individuals are more prone to engage in negative health behaviors such as

smoking, drug and alcohol use, and violence. Lastly, work stress has also been linked to

higher levels of family conflict, sleep disturbances, and depression (see Greenberg &

Baron, 2008 for a review).

According to the effort-recovery model, if an individual is unable to recover after

prolonged activation due to work stressors, negative outcomes such as reduced well-

being and health are often the case. In the case of failing to recover, an individual

continually taxes the psychological and physiological systems that are called into action

as a result of dealing with such work stressors. When these systems fail to recover to

prestressor levels, compensatory mechanisms are often called upon, further draining

resource reserves. It is this continual activation and further taxation on one’s systems that

often leads to negative health outcomes for those dealing with chronic work stress. For

example, the depletion of one’s resources often becomes apparent in the form of

increased psychosomatic complaints (Pennebaker, 1982).

Interpersonal Conflict and Employee Well-Being

Research has demonstrated that interpersonal conflict is a work stressor that may

come in various forms, including overt and covert behaviors by coworkers (Spector &

Jex, 1998). Employees experiencing interpersonal conflict may experience a host of

30

negative outcomes as a response including impaired well-being (Stoetzer et al., 2009).

Conflict in itself is inherently stressful. Negative emotions, threatened self-esteem, and

heightened cognitive effort as a result of interpersonal conflict can impact an individual’s

physiological resources in a multitude of ways (De Dreu et al., 2004b). The ego depletion

model has been offered as a possible explanation for these relationships. Specifically,

research indicates that asking individuals to regulate and control their emotions is

associated with subsequent decreases in physical ability and the ability to regulate further

emotional responses (Baumeister et al., 1998; Muraven et al., 1998). For these reasons, it

is important to further examine the negative impacts of interpersonal conflict at work, and

to investigate factors that may help alleviate negative outcomes.

An overview of possible negative outcomes of interpersonal conflict at work

indicates that dealing with conflict at work is associated with higher levels of stress

hormones which deplete the physiological system (McEwen, 1998; De Dreu, Van

Dierendonck, & Best-Waldhober, 2004a). This depletion of one’s systems may become

manifest as psychosomatic complaints, such as persistent headaches and upset stomachs

(Pennebaker, 1982). Additionally, enduring conflict at work may lead to decreased

individual well-being through increased rumination, alcohol intake and low-quality sleep

(Cooper & Marshall, 1976; Danna & Griffin, 1999).

One meta-analysis (Spector & Jex, 1998) further indicates that interpersonal

conflict at work is associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, frustration and

doctor visits. Workplace aggression, a similar construct, has also been linked to employee

31

health and well-being (Herschovis & Barling, 2009). Specifically, workplace aggression,

regardless of the source, was related to higher levels of emotional exhaustion and

depression and lower levels of physical well-being and general health. According to the

results of Hershcovis and Barling’s (2009) meta-analysis, supervisor, co-worker, and

outsider aggression were all related to general health, emotional exhaustion, depression,

and physical well-being. Supervisor aggression was shown to have stronger adverse

impact on general health than co-worker aggression. On the other hand, co-worker

aggression had a greater adverse impact than supervisor aggression on physical well-

being. In comparing co-worker aggression and outsider aggression, co-worker aggression

had a stronger adverse impact than outsider aggression on physical well-being. Lastly, in

comparing supervisor aggression to outsider aggression, supervisor aggression had a

stronger adverse impact on general health than outsider aggression.

In addition to the meta-analytic evidence for the detrimental consequences of

workplace interpersonal conflict and workplace aggression, a recent longitudinal study

also examined problematic interpersonal relationships at work and their effects on

employee depression levels (Stoetzer et al., 2009). This study examined a cohort of

Swedish employees over two years. In addition to looking at interpersonal conflict, the

researchers also examined social support, exclusion by superiors, and exclusion by co-

workers. All four of these variables, including conflict at work, were related to higher

levels of depression among employees. Previous depression was controlled for,

suggesting that interpersonal conflict is associated with subsequent lowered well-being,

32

above and beyond lowered well-being being a possible predictor of conflict. In summary,

interpersonal conflict at work has been associated with a variety of well-being outcomes,

which implies that it is an important workplace stressor that necessitates further study.

It is important to note that while this study conceptualizes interpersonal conflict at

work as leading to detrimental health outcomes, it is also possible that lowered levels of

well-being lead to workplace interpersonal conflict. In this case, employees would come

to work with lowered levels of resources, which would potentially result in a lowered

ability to engage in emotion regulation, and subsequently, higher levels of interpersonal

conflict. However, this process poses a separate and unique research question that could

potentially be addressed with longitudinal research designs. In the context of COR theory

(Hobfoll, 1989), it is possible that interpersonal conflict in the workplace is associated

with lowered well-being, and for those with lowered levels of resources, may set off a

‘loss spiral,’ which would in turn be associated with subsequent higher levels of

interpersonal conflict. For the purposes of the current study, interpersonal conflict will be

conceptualized as an antecedent to lowered well-being.

Recovery Experiences As Potential Moderators

As the previous section suggests, there have been numerous studies linking

interpersonal conflict at work to potential individual outcomes, including employee well-

being. Additionally, interpersonal conflict is only one of many work stressors, many of

which (including role conflict, role ambiguity, lack of control, and perceived workload)

have been examined in detail with respect to employee well-being outcomes (e. g.,

33

Jackson & Schuler, 1985; Spector, 1986; Spector, Dwyer, & Jex, 1988; Jex & Beehr,

1991; Spector & Jex, 1998). Recent research has also examined the benefits of various

recovery experiences outside of work on employee well-being and performance (Fritz &

Sonnentag, 2005; 2006; Sonnentag & Bayer, 2005; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Only

recently, however, have particular recovery experiences been examined as possible

boundary conditions in the relationship between work stressors and well-being outcomes

(Siltaloppi et al., 2009; Kinnunen et al., 2010; Sonnentag et al., 2010).

A recent study examined the direct and moderator roles of psychological

detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control in the relationship between time demands,

job control, and justice of the supervisor and work-related well-being (Siltaloppi et al.,

2009). In this study, work-related well-being was measured as need for recovery, job

exhaustion, and work engagement. Psychological detachment and mastery were found to

moderate the relationship between job control and need for recovery; additionally,

relaxation was shown to moderate the relationship between time demands and job

exhaustion. More specifically, higher levels of detachment and mastery were associated

with lower need for recovery, both generally and particularly in a low control situation,

compared to those low in detachment. Secondly, job exhaustion was higher in situations

of high time demands and low relaxation. Employees high in relaxation expressed a

weaker negative association between time demands and job exhaustion.

Furthermore, a recent study examining recovery experiences as moderators of the

relationship between job insecurity and well-being outcomes indicated differential effects

34

of recovery experiences as buffers against the negative outcomes of work stressors

(Kinnunen et al., 2010). Specifically, across a sample of 527 employees from various

occupations, relaxation moderated the relationship between an insecure job situation and

need for recovery, such that individuals with low relaxation experienced higher need for

recovery in conditions of high job insecurity. Control was also found to moderate the

relationship between job insecurity and need for recovery. Individuals with high levels of

control experienced significantly lower need for recovery under conditions of low job

insecurity, though under conditions of high job insecurity, individuals with both high and

low control experienced similar levels of need for recovery. Lastly, psychological

detachment was found to moderate the relationship between job insecurity and vigor at

work, such that individuals with high psychological detachment experienced similar

levels of vigor at work under both low and high conditions of job insecurity, while those

with low psychological detachment experienced lower vigor at work under conditions of

high job insecurity. Job insecurity is just one of many daily stressors faced by employees,

and it is possible that recovery experiences will play differing roles as moderators

depending on the form of work stressor.

A recent longitudinal study by Sonnentag and colleagues (Sonnentag et al., 2010)

examined the role of psychological detachment during nonwork time as a moderator of

the relationship between job demands and psychological well-being and work

engagement. Among a sample of 309 human service employees, psychological

detachment was shown to moderate the relationship between job demands and

35

psychological well-being and work engagement, such that those with high levels of job

demands and low levels of psychological detachment experienced higher levels of

psychosomatic complaints and decreased levels of work engagement. In the present

study, various recovery experiences may buffer against negative outcomes of

interpersonal conflict at work. Thus, the current study seeks to extend recent research

examining recovery experiences as moderators, particularly by exploring interpersonal

conflict as the workplace stressor in question.

According to the effort-recovery model, extended effort at work requires a period

of recovery afterwards in order for an individual’s psychobiological systems to return to

the prestressor level. In the context of this study, interpersonal conflict at work acts as a

work stressor that will engage psychological and physiological processes. Over time, this

activation will be associated with impairments in well-being and health. Therefore,

recovery is necessary for alleviating the negative outcomes associated with work

stressors. In addition, specific recovery experiences outside of work may buffer against

the negative impacts of interpersonal conflict. Thus, though there may be detrimental

outcomes associated with interpersonal conflict at work, engaging in various recovery