Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 1

Interpersonal Conflict and Academic

Success: A Campus Survey with Practical

Applications for Academic Ombuds

PHOEBE MORGAN, HEATHER FOSTER, AND BRIAN AYRES

ABSTRACT

A team of student researchers supervised by

a certified organizational ombuds surveyed

the interpersonal conflict experiences of 106

undergraduates on a university campus that

offers limited ombuds services to students.

While a small minority of respondents

reported disputes about university policies or

disagreements with university personnel,

nearly all (90%) reported conflicts with other

students within a year of the survey. Intimate

relationships (i.e., friends, roommates, and

romantic partners) accounted for the

majority of the conflicts. While most claimed

the conflicts mentioned in the survey did not

seriously impact daily life, 70% said the

conflicts negatively impacted their academic

efforts. About one-third of those who

reported having a conflict said they had

sought the assistance of a third party, and

25% of those who did so turned to a faculty

member for help in dealing with conflicts

with other students. When asked to rate the

importance of various qualities of third-party

assistance, respondents felt a trained

volunteer would most likely facilitate a

satisfactory resolution. Despite the small

sample size and the limitations of the data

collection design, the results suggest a range

of practical applications for academic

ombuds.

KEYWORDS

Student conflict, interpersonal conflict,

ombuds, academic ombuds, student success

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 2

INTERPERSONAL CONFLICT AND ACADEMIC SUCCESS: A CAMPUS

SURVEY WITH PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIC

INTRODUCTION

Much of the work of the academic ombuds regard listening to and facilitating resolution

assistance for visitors dealing with interpersonal conflict. About half of all visits to an ombuds

office involve concerns regarding relationships with peers and those charged with the

responsibility to evaluate their performance (Katz, Soza, & Kovack, 2018). Moreover, even when

issues raised with an ombuds fall into a different category, they often emerge from an initial

complaint about interpersonal discord. As a result, on a day-to-day basis, academic ombuds

devote much of their time listening to conflict-related concerns, providing one-on-one conflict

coaching, serving as third-party mediators, and referring their visitors to appropriate support

services (Gadlin, 2000).

Over time trends may surface that connect these interpersonal issues to larger systemic ones.

When viewed as a whole, the interpersonal concerns of visitors to an ombuds office may point to

the unmet conflict resolution needs of an entire group or community. They may also highlight

common practices or policies that precipitate or aggravate the interpersonal dispute. Finally, they

can signify a hostile environment, a toxic subculture, and the inappropriate actions of one

individual or a group of bad actors. When trends such as these emerge, ombuds are often the

first to identify connections between interpersonal discord and organizational dysfunction

(Wagner, 1998; Rowe, 1991). Through their formal annual reports and informal conversations,

academic ombuds assist leadership in developing expectations and prioritizing services for

conflict resolution (Schneck & Zinsser, 2014; Katz, Sosa, & Kovak, 2018).

Key to identifying and describing trending concerns is the effective utilization of data (Barkat,

2015), and visitor tracking data (VTD) is most commonly used for that purpose. Careful

deployment of VTD can provide compelling descriptions of trends from the visitor’s point of view.

However, the generalizability of VTD is quite limited. Such data cannot, for example, speak to the

concerns of constituents who have not yet visited an ombuds office, or how the experiences of

those who seek ombuds assistance compare with those who do not. Survey data are ideal for

addressing the question of prevalence, but few ombuds programs have the expertise or

resources to design and implement survey projects. Because many ombuds are solo practitioners

without research budgets, they rely upon the research findings of others (Rowe & Bloch, 2012).

Historically, research within and for the ombuds community has tended to be qualitative, in the

form of historical analyses (e.g., Claussen, 2013), in-depth interview (e.g., Levine-Finely & Carter,

2010), or ethnographic field studies (e.g., Emerson, 2008; Harrison & Morrill, 2004). While

qualitative research projects like these have advanced theoretical understandings, their ability to

establish the prevalence of practices, needs or experiences are limited. In contrast, survey data

can provide snapshots of concerns in the aggregate, identify the needs and experiences of those

who have not yet visited an ombuds office. Such survey results can be deployed to improve

outreach to underserved constituent groups, inform prevention training programming, and

suggest effective intervention strategies.

The preponderance of ombuds scholarship about conflict has been from a practitioners’ point of

view. Less has been written from the standpoint of those who visit the offices of those

practitioners. Our understanding of the experiences and expectations of actual and potential

visitors to an ombuds office is largely anecdotal, and analyses are often limited to internal

tracking data. The project described in this article seeks to address this gap by posing a series of

questions focused on the needs of student constituents — specifically, their experiences of

interpersonal conflict and efforts to resolve them. How many disputes or disagreements does the

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 3

average student experience in an academic year? When conflict arises, how much does it impact

their daily lives and academic performance? Who, or what offices do students turn to when they

seek help in resolving their disputes or disagreements? Finally, when students seek help with

interpersonal conflicts, what characteristics of third-party assistance do they prefer?

The following pages pursue these questions by reporting key findings from a campus-wide survey

of undergraduates attending a university where conflict resolution services are abundant and

diverse, but access to the campus’s ombuds program is limited

1

. The subsequent report is

presented in four sections. The next section describes the project’s origins, the focus of its

inquiry, and how a team of student researchers worked together to realize it. Section two reviews

the relevant literature to provide a rationale for the study’s methodology and describes how the

data were collected and analyzed. The third section presents the key findings, and the final

section discusses the survey’s limitations and practical applications for academic ombuds.

PROJECT ORIGIN

The idea for this project was born in a special topics course for criminology, and criminal justice

majors called CCJ 480: Alternative Dispute Resolution (CCJ 480-ADR). The first author designed

the course after serving a three-year term in the dual role of faculty member and coordinator of

the university’s Faculty Ombuds Program where faculty brought to the office a wide range of

concerns, teachers and advisors commonly asked for assistance in dealing with conflicts they

had with students, as well as conflicts between their students. In many cases, the students

involved visited the FOP upon invitation and either participated in mediation or were referred to

another office or program that offered conflict resolution services specifically for students.

Inspired by the experience, the first author developed the course as a means to help students

hone their conflict management skills.

The students enrolled in CCJ 480-ADR bring to the course a vibrant and diverse stock of

common knowledge informed by their direct and highly personal experience of conflict. The

course addresses and challenges their knowledge by exposing them to scholarly theories and

research about it. Over the years, about 500 CCJ majors have completed nine sections of CCJ

480-ADR. Students appreciate how the course material resonates with the challenges they face

in everyday life. In particular, they find immediate application concerning their struggles to

understand and deal with the stress of interpersonal conflict with other students. Consequently,

course assignments involve connecting the macro (universal principles about conflict and

resolution) to the micro (the particularities of lived experiences of roommate troubles, dating

discord, and disagreements between a team and club members). For many, this approach

catalyzes personal, academic and professional growth in the management of interpersonal

conflict.

Each semester CCJ 480-ADR students work in teams to complete term projects that showcase

their expertise on an issue or topic relevant to the course. Designed to meet the university’s

requirements for the liberal studies capstone experience, many of these term projects become

significant service learning initiatives. CCJ 480-ADR students have, for example, served the

campus community by conducting conflict management workshops for students living in resident

halls, Greek life council members, student executive council members, peer mentors, and

athletes. On Valentine’s Day, teams have provided ‘pop up’ street clinics to help those in romantic

relationships resolve conflicts with their loved ones. Projects like these help fill in the gaps of the

university’s conflict resolution services system.

1

Due to budgetary constraints, in 2007 the University Ombuds Office charter was discontinued and in

2009 a Faculty Ombuds Program was established.

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 4

In 2014, a team of five graduating CCJ majors led by the third author decided to serve the

campus by surveying the experiences of students about the types, amount and consequences of

interpersonal conflict among undergraduates. In brainstorming the survey’s focus, the team drew

upon their own life experiences to posit that interpersonal conflict between students is a common

experience that significantly impacts the quality of daily life and academic performance.

Reflecting on the re-occurring themes of class discussions, the team felt that because conflicts

with university personnel more often become newsworthy (Astor, 2018; Carroll, 2003; Lembo,

2016; Taylor & Sandeman, 2016), the significance of interpersonal conflicts between students is

too often underappreciated or overlooked altogether.

The team began their investigation by defining key terms. Drawing upon assigned readings, the

team defined conflict as broadly as possible to include disputes, disagreements or differences of

opinions between individuals that often, but do not always, create a sense of discord, disquiet or

stress (Willett, 1998). Interpersonal conflicts were defined as those occurring between peers and

in the context of relationships that involved regular or ongoing personal interaction (i.e., friends,

loved ones, teammates and roommates).

From here, the team turned their attention to operationalizing the concept of academic success.

Based on a review of the mission and purpose statements for a variety of student success

programs, the team defined academic success as the achievement of personal, social and career

development arrived at through academic engagement. While benchmarks of student success

vary across programs, the two most commonly used are the successful completion of a course

and the timely progression to graduation (see, for example, North Dakota State’s Student

Success Collaborative at https://www.ndsu.edu/enrollmentmanagement/studentsuccess). In order

to support the achievement of these larger goals, student success centers provide resources to

achieve behaviors like regular class attendance, effective study and note-taking, timely

submission of work, and classroom activity engagement (a good example is Pittsburgh State’s

Student Success Program at https://www.pittstate.edu/office/student-success-

programs/academic-success-workshops.html).

With these definitions in hand, the team searched the scholarly literature for relevant research.

While they discovered numerous research reports regarding conflicts between students and their

teachers and advisors, this phase of the project revealed a gap in the literature regarding conflicts

between students and the impact of those conflicts on academic success.

RELEVANT RESEARCH AND RESEARCH DESIGN

The team began their review of published research with studies of student-student conflict at the

college level. They found that a majority of the articles focus on conflict that occurs within the

context of evaluative relationships – i.e., a conflict between students and those with authority to

evaluate their academic success (teachers, internship supervisors, or graduate advisors). Of

those, the results of one study suggest that family and friends can play a positive role in the

management of conflict with those who evaluate academic success. A survey of 55 international

graduate students and 53 faculty supervisors reported that advisors were more likely than

students to feel conflicts had been successfully resolved. Interestingly, 73% of the students

surveyed said they would talk with a family or a friend before talking with their advisor,

department head or dean of student life (Adrian-Taylor, Noels, & Tischler, 2007). A similar survey

of 153 graduate students found that instructors and advisors who appeared to be competent

conflict managers were more likely to be trusted to assist in conflict intervention or management

(Punyanunt-Carter & Wrench, 2008). A third study found that more than half of the participants

said the conflict between students and their preceptors was frequent, and 46% said such conflict

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 5

impeded academic growth (Manchur & Mayrick, 2003). Finally, an assessment of conflict

management training for graduate teaching assistants found the conflict management styles of

their supervisors was related to their success (Brockman, Nunez, & Basu, 2010).

The team also found a few reports focused exclusively on the interpersonal conflicts of students.

In a 2010 survey of 3,844 students from 9 institutions of higher education, for example, 29.2% of

the respondents visited campus clinics for help in dealing with interpersonal conflicts and ranked

the problem of conflict second only to mood difficulties (Krumrie, Newton, & Kim, 2010).

Furthermore, the survey found that interpersonal conflict problems were often embedded in

reports of mood regulation, eating disorders, performance anxiety, and life satisfaction.

Although not a study of conflict per se, a study measuring the impact of stress on student success

reported that more than half of the 100 undergraduates who participated in a survey claimed

conflicts with roommates (61%) and conflicts with romantic partners (57%) were stressful (Ross,

Niebling, & Heckert, 1999). Another survey of 140 female undergraduates found a statistically

significant correlation between conflict and mood regulation (Creasey, Kershaw, & Boston, 1999).

In that study, those with secure relationships with friends and romantic partners were less likely to

report negative conflict management experiences, and those with negative conflict management

experiences were more likely to struggle with mood regulation. In 2010, DiPaola and colleagues

surveyed the experiences of 208 undergraduates regarding a variety of relational categories and

found that the closeness of the relationship was positively related to the intensity of the

interpersonal conflict. The emotional impact of conflicts with friends, roommates and loved ones,

for example, were more intense than those with strangers (DiPaola, 2010).

A few studies reported on the consequences when interpersonal conflict is ill-managed or allowed

to escalate. In 2013, for example, McDonald and Asher (2013) analyzed the responses of 157

college students to a series of interpersonal conflict vignettes and found that emotional intensity

correlated with revenge as a conflict resolution strategy and that students were more likely to

endorse hostile goals with romantic partners than with friends or roommates. Similarly, a

qualitative analysis of 153 student accounts of roommate troubles found that) in the early stages

of discord students go along to get along, but as roommate troubles escalate, students

increasingly embrace antagonistic strategies (Emerson, 2008 & 2011). Finally, in a more recent

survey of 1811 high school seniors, Courtain and Glowacz (2018) found students capable of

perspective-taking were more likely to choose conflict resolution strategies that would improve the

relationship, while students prone to impulsivity were more likely to adopt conflict management

strategies likely to damage the relationship.

When viewed together, the results of these studies suggest that peer conflict (i.e., disputes and

disagreements with another student) can have as significant an impact on the college experience

as evaluative conflict (i.e., disputes and disagreements with teachers, advisors, coaches, mentors

and other campus authorities responsible for assessing academic success). The review further

suggests that not all peer relationships are the same and differences among them can color the

character of the conflict and therefore the impact it has on life satisfaction and academic

performance. Specifically, the amount of intimacy or closeness in the relationship could be a

significant factor in how students experience conflicts with each other. Inspired by their own

experiences, and informed by the relevant literature, the team posed the following research

questions for further investigation:

How prevalent is peer conflict among college and university students?

How does the prevalence of conflicts between students compare with conflicts students

have with university personnel?

What is the impact of conflict on efforts to achieve academic success?

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 6

What role does intimacy play in the conflict experience?

Whom do students turn to when they seek help in resolving their interpersonal conflict?

What characteristics of a third party intervention do students associate with resolution

satisfaction?

At this point, the team drafted a series of forced choice questions designed to describe the

prevalence of interpersonal conflicts among undergraduates, the perceived impact of those

conflicts have on daily life and academic success, and to identify the types of personnel that

undergraduates seek help from, as well as the types of conflict intervention they prefer. Because

the research literature review did not uncover replicable questionnaire items, the team designed,

pre-tested and revised an original 27-item questionnaire (see Appendix). The items are organized

by four key concepts: 1. Demographics, 2. Conflict with University Personnel, 3. Conflict with

Other Students, and 4. Dispute Resolution Assistance. Serving as a validity hedge, the 27

th

item

on the questionnaire was open-ended, inviting respondents to share any additional information of

their choosing.

Once exemption from IRB review was obtained, the team deployed a non-probability sampling

approach that combined the techniques of geographic cluster sampling and quota sampling

(Kalton, 1983). Seven high traffic areas on campus were identified (i.e., classroom buildings,

libraries, computer commons, union, parking lots, shuttle bus stations, etc.) and a team member

was assigned to each station. For one morning or afternoon during a week in April 2014, each

team member randomly selected potential participants from those who passed by. The final

sample of 106 undergraduates was large enough and diverse enough to support statistical

analyses of the resulting responses.

KEY FINDINGS

At the conclusion of the data collection phase, a group of research interns led by the second

author joined the team. Using the Statistical Package for The Social Sciences (SPSS), they

completed data entry, ran the statistics and created graphical displays for course credit.

DEMOGRAPHICS

About 58% of the 106 respondents were female, 46% were nonwhite, and 60% were in-state

students. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, this profile is typical for

undergraduates enrolled in a four-year public university in the U.S. during 2018 (NCES, 2018).

Majors from all the colleges at this university were represented, although, when compared to

institutional data, the sample’s science majors were slightly over-sampled and English majors

were slightly under-sampled. The sample was also skewed toward traditionally-aged freshmen

and sophomores in that the average age was not quite 20 years old. Sixty-seven percent of the

participants lived in residence halls, and 71% of them shared living quarters with at least two

other students. When viewed as a whole, these demographics suggest that there were ample

opportunities for those who participated in the study to have experienced conflicts with other

students in a variety of circumstances and settings.

CONFLICTS WITH UNIVERSITY PERSONNEL

The team’s review of news media and scholarly literature revealed concern about conflicts

between students and university personnel. Consequently, four questionnaire items sought to

capture the amount and types of conflict the respondents had with university personnel. Only

17.9% of the 106 respondents said they had ever had a dispute or disagreement about university

policy or had ever taken issue with the decisions of a representative of the university. Those 18

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 7

respondents were given a list of 41 programs or departments and asked to check all that was

relevant. The most common choices were parking services (46%), academic advising (39.3%)

and class grades (32.2%). Similarly, they were given a list of six common issues and asked to

identify all that applied and the most common answers were similar: parking (52%) and

instruction/academic support (30%).

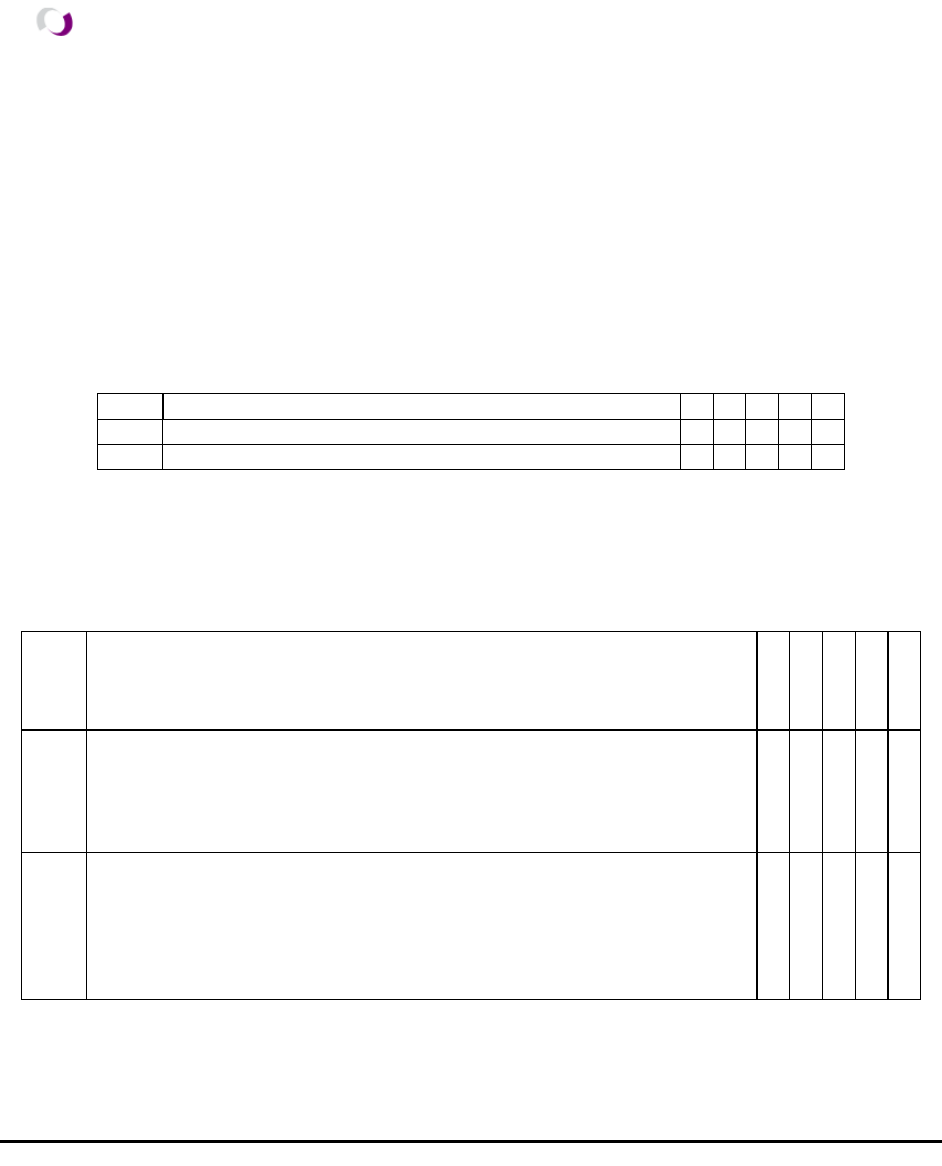

Finally, the 18 students who reported disagreements with university personnel or disputes

regarding university policies and practices were given a list of nine potential academic

consequences and asked to rate on a five-point scale the seriousness of the impact (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Seriousness of Conflict with University Personnel on Academic Success (n = 18)

While the overall average rating of seriousness for all nine consequences was just above 1.43, or

“not serious at all,’ it is important to note that all 18 respondents indicated that, as a result of their

conflict with university personnel, they had to drop or withdraw from a class and 16 of them

claimed their graduations were delayed.

CONFLICTS WITH OTHER STUDENTS

In contrast to conflicts involving university personnel, conflicts with other students were common.

Of the 106 students who completed the questionnaire, 90% (n = 96) said they had experienced at

least one conflict with another student within a year of their participation in the survey. These 96

respondents reported a total of 848 disputes or disagreements with other students, averaging 8.5

disputes per respondent. Approximately one third (32%) of the respondents generated about half

(53%) of these reported conflicts; thus, for these 33 students, interpersonal conflict may be a

common feature of college life. When asked to estimate the number of conflicts experienced

within the last year, one respondent wrote “a million,” and another wrote, “too many to count.” In

the open comment section of the survey, a freshman further elaborated: “fights with my roommate

[happen] every single day.” Moreover, a rising senior explained: “[in every class] there’s always

one group member who wants to make the rest of us miserable.”

Because the review of published research indicated that the amount of intimacy is a factor

affecting a student’s conflict experience, the team took a closer look at the distribution of reported

Seriousness of Impact

Impact

3.11

2.79

2.72

2.5

2.42

2.39

2.32

2.06

1.94

0 1 2 3 4 5

Had to drop or withdraw from a class

Thought about transferring to another school

Unable to meet a class deadline

Had to delay my graduation

Did not do my best work on an assignment

Unable to concentrate on schoolwork

Had to miss class

Unable to perform well at an on-campus job

Thought about dropping out of college

Not serious

at all

Very

Serious

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 8

conflicts across a continuum of intimacy defined by seven types of relationships. At the low end of

the continuum are strangers, toward the middle are relationships with acquaintances – i.e.,

teammates and classmates, and at the high end are relationships with friends, roommates, and

romantic partners. Figure 2 displays two distributions across the continuum. The first distribution

is the number of respondents who reported a disagreement or dispute with another student for

seven categories (labeled as "Relationship Type"). The second distribution is the number of

disagreements or disputes those respondents reported (labeled as "Conflicts"). So, for example,

within one year of the survey, 71 respondents reported a total of 258 conflicts with a student who

was considered a friend.

Figure 2: Conflicts with Other Students

Figure 2 shows that the preponderance (78%) of the 848 student-to-student conflicts occurred at

the high end of the intimacy continuum – i.e., friends, roommates or romantic partners (this

category includes boyfriends, girlfriends and spouses). In contrast, just 22% of the 848 conflicts

involved acquaintances (i.e., teammates, classmates, and co-workers, for example) and

strangers. Interestingly, a sizable minority (33%) of these 96 respondents reported conflicts

across the entire continuum. i.e., all seven relationship categories. For these students, conflict

may be an endemic feature of everyday social interaction.

In light of the literature review, the survey included items that could assess the impact of conflicts

across the intimacy continuum. Thus, those who reported disputes or disagreements with other

students were then asked to rate on a five-point scale the seriousness of the impact of their

conflicts on daily life by each of the seven types of relationships. Overall, the average impact on

daily life was only 1.83. Thus, on a daily basis, in the words of one respondent, disputes or

disagreements with other students were “no big deal.” In fact, in their open comments, a few

respondents said they felt the conflict in a close relationship was normal or even healthy. One

female respondent, for example, said an “occasional clearing of the air makes us [roommates] get

along better.”

Respondents who had experienced one or more conflicts with another student within a year of the

survey were asked to rate the seriousness of the impact of those conflicts on the same list of nine

academic consequences that were provided to those who reported conflicts with academic

personnel. Figure 3 compares two distributions: (1) the average ratings of the seriousness of

impact of student conflicts and (2) the average ratings of the seriousness of conflicts with

university personnel.

44

32

48

47

71

67

49

44

32

49

58

258

256

151

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Stranger Teammate Classmate Coworker Friend Roommate Romantic

Partner

Number of Responses

Relationship Type

Relationship Type (n = 96) Conflicts (total # = 848)

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 9

Figure 3: Seriousness of the Consequences of Conflict on Academic Performance

About the academic consequences of conflicts of other students, the range of average ratings for

each category was 2.04 -2.43, or somewhere between “serious” and “somewhat serious.” The

highest ratings were “did not do my best work” (2.43), “unable to meet a class deadline” (2.39)

and “unable to concentrate on schoolwork” (2.21). While the most serious consequence of a

conflict with university personnel was “had to drop or withdraw from a class,” the most serious

consequence of conflict with another student was “thinking about dropping out of college.” In the

open comments, a respondent explained that “bullying by teammates” had caused him/her to

consider “forfeiting an athletic scholarship” and transferring to another university.

DISPUTE RESOLUTION ASSISTANCE

The team’s review of the research revealed a gap in the literature concerning resolution

assistance seeking. For this reason, the final section of the questionnaire included eight items

designed to gather information about the respondents’ efforts at seeking assistance in resolving

their interpersonal conflicts with students, as well as their perceptions of differing models of

conflict intervention. Those who had reported experiencing disputes or disagreements with

anyone associated with the university (i.e. university personnel or other students) were given a

list of 20 potential third parties that included a variety of university representatives (for example,

instructors, counselors and student life representatives) as well as personal contacts (i.e.,

students, parents, and lawyers) and asked to indicate if they had contacted any of them for

assistance. Of the 106 who completed the survey, only 37 said they had asked for help from any

university representative. Only eight of the 20 types of university representatives were selected.

Figure 4 displays the percentage of responses for each of the eight categories.

0 1 2 3 4 5

Thought about dropping out of college

Had to drop or withdraw from a class

Had to delay my graduation

Did not do my best on an assignment

Unable to meet a class deadline

Thought about transferring to another school

Unable to perform well at an on campus job

Unable to concentrate on schoolwork

Had to miss class

Seriousness of Impact

Impact

Conflict w/

other students

(n = 96)

Conflict w/

University

personnel

(n = 19)

Very

Serious

Not serious

at all

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 10

Figure 4: Third Parties Contacted for Conflict Assistance

Given the number of roommate disputes reported in this survey, it is surprising that less than 9%

of the respondents sought help from a resident hall staff member. Equally surprising is the fact

that the number of contacts with academic personnel (i.e., faculty members and academic

advisors) exceeds that of non-academic personnel (resident hall staff, coaches, legal aid, other

students, parents, and personal lawyers). About a fourth (24.5%) of the 37 respondents who

answered this question contacted faculty members, and 16.2% asked their academic advisors to

help them find a resolution. In the open comments, one freshman explained that an instructor’s

insensitivity to his/her plight in dealing with an abusive boyfriend increased his/her stress. The

respondent explained “[my] teachers didn’t want to hear it and didn’t care.” In contrast, an

upperclassman was “forever grateful” that his/her professor provided the opportunity to make up

an exam missed due to a late night argument with a boyfriend.

The next set of questions sought information about the perceived outcomes of respondents’

efforts in resolving conflicts with either university personnel or with other students. When asked if

their most recent disagreement or dispute had been resolved, only 25% said yes. The rest

indicated they were either still in conflict (45.8%), a resolution was in progress (12.5%), or unsure

if the conflict had been resolved (17%). Respondents who had sought help from university

personnel were then asked to rate on a five-point scale their satisfaction with three elements: the

process, outcome, and effort. Even though 48 respondents reported contacting university

personnel for conflict resolution assistance, only 20 respondents choose to rate these items. With

one meaning “not satisfied at all” and five meaning “completely satisfied,” the overall average

rating for was 2.25 or “satisfied.” In an open comment, one student expressed dissatisfaction with

the efforts of a peer TA’s attempts to facilitate resolution of group project conflict and two other

respondents described the interventions of resident life hall workers (student workers) as “lame”

and “bad.”

While most college and university campuses provide students with third-party conflict resolution

assistance, there is significant diversity in the types of models that are deployed. The academic

ombuds model, for example, emphasizes neutrality. Those without an ombuds office may rely

upon university personnel who have received advanced training in mediation, advocacy, or

conflict coaching. Finally, some campuses may operate peer volunteer mediation programs.

Missing in the literature reviewed were efforts to assess students’ resolution assistance

preferences. To that end, the questionnaire included three questions that sought to learn more

2.7

5.4

10.8

10.8

13.5

16.2

16.2

24.5

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Legal Aid

Resident Hall Staff

Coaches & Mentors

Other Students

Office Staff

Parents & Lawyers

Academic Advisor

Faculty

Percent of total response

Third Parties Contacted

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 11

about preferences students might have when seeking a third party to facilitate conflict resolution.

The team identified three qualities of a third party – neutrality, professionalism, and voluntariness

– could impact a student’s satisfaction with the resolution process or outcome. Neutrality was

operationalized as “someone who does not decide right or wrong, but who works to make sure

the process and outcome is fair for all parties.” Professionalism was characterized as “someone

with special education or training in the facilitation of conflict resolution.” The third,

“voluntariness,” was defined as “a peer who draws upon personal experience and some training

to help facilitate a fair resolution.”

All respondents (regardless of whether or not they had experienced conflict within a year of the

study) were asked to reflect on their most recent dispute or disagreement and rate the importance

of each characteristic for achieving a satisfactory resolution. Respondents rated the importance of

each characteristic on a scale of one to five, with one being “not very important at all” and five

being “very important.” While all three characteristics were deemed important for a satisfactory

resolution, the help of a trained volunteer was rated as slightly more important (4.0) than the

presence of either a neutral party (3.63) or professional resolution facilitation (3.58).

DISCUSSION

While interest in the empirical study of student conflict has grown in recent years, the focus of

attention has been on conflicts in the context of evaluative relationships (i.e., teachers and

advisors). Similarly, a cursory review of recent news media suggests conflicts with university

personnel seem to be more newsworthy than conflicts between students (see for example Carroll,

2003; Lembo, 2016; Taylor & Sandeman, 2016). And empirical studies of student-student conflict

has been predominately qualitative and limited to conflicts between roommates. Drawing upon

their direct experiences as college students, the team that pursued this project saw a gap in the

literature and endeavored to address it. What they were able to discover supports the widespread

view interpersonal conflict can affect the quality of a student’s social life. However, the project

goes further to suggest that interpersonal conflict may impact academic success. When viewed

together these insights suggest assisting students in managing and resolving their interpersonal

conflicts is neither a student support issue nor an academic issue. It is both. As such, effective

conflict management and resolution services should be prioritized accordingly.

Thus, to maximize their effectiveness, those who assist students on the “support side of the

house” (i.e., resident life staff, diversity and disability advisors, clinicians, etc) need to assess and

then take into consideration the extent to which everyday conflicts over seemingly

inconsequential issues like food, cleanliness, money owed and parking can impact academic

performance. Similarly, those who labor on the “academic side of the house” (faculty, mentors,

tutors and academic advisors) would do well to remember that as ‘first responders,” they are

often the first to see the effects of interpersonal conflict on academic performances (Kafka, 2018).

Academic ombuds practitioners are uniquely positioned to facilitate collaborations between

student support and academic personnel and help them assess their shared need to provide

effective conflict assistance and coordinate the efforts of all those who touch the social lives and

academic endeavors of college students. As conflict resolution experts, academic ombuds

practitioners can play leading roles in brainstorming and implementing effective conflict

management and conflict resolution protocols. This report points to a range of possible

preliminary actions. Before discussing those first steps, it is important to knowledge the limitations

imposed by the inevitable challenges that characterize student research.

While the demographics of the final sample were similar to those of the institution and national

population, the extent to which it represents those populations is incalculable (Kalton, 1983).

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 12

Therefore, while suggestive, the results are not conclusive. Future replications could, however,

explore the extent to which the findings can be generalized to other campuses. Furthermore, the

small size of the final sample resulted in comparison groups too small to meet the assumptions

necessary for confidence in statistical tests of differences between answers to multiple questions

(Henkel, 1976). Relatedly, although the five-point barometric scales that were used do meet the

assumptions for valid associative models, insufficient variation did not meet the muster for

regression modeling (Fox, 1991). As a result, the ability to predict the extent to which

interpersonal conflicts or the amount of intimacy of those conflicts could impact either academic

success, or preferences for conflict resolution was beyond the scope of this study. Despite these

limitations, the descriptive statistics reported in this article do provide some insights for academic

ombuds work.

While the charters of academic ombuds programs vary considerably from one campus to another,

there are opportunities to apply elements of this project to support the efforts of academic

ombuds practitioners. On a daily basis student ombuds spend much of the day listening to

concerns, investigating the facts, identifying the issues and brainstorming strategies for resolving

them. For those who work directly with students, the key findings of this survey could inform the

development of a series of questions that could support a deeper reflection regarding program

goals and best practices. For example, this survey found that a small group of students appeared

to be conflict ‘magnets.’ If visitor data show similar trends, the ability to identify these types of

students early and assess to what extent their magnetism is due to circumstance or conflict style

could lead to more efficient and effective interventions. Doing so could reduce the number of

‘frequent flyers’ and perhaps relieve the conflict intervention loads of the other programs across

the campus that are working with the same high conflict students.

Similarly, the findings revealed a number of ‘hot spots’ where the number of student conflicts was

particularly high. This insight might lead to a deeper consideration of how visitor tracking data

could be collected or organized to identify high traffic areas. While the findings could spark

conversation, direct application of the instrument used to collect the data could capture trends

that visitor tracking forms are unable to capture. A campus-wide survey using the CCJ 480-ADR

questionnaire could be deployed to determine the extent to which students are effectively utilizing

an ombuds program. If, for example, the survey trends are dramatically different from visitor

trends, an ombuds program might need to reassess their outreach initiatives or take a closer look

at the menu of conflict resolution services provided to students.

While the thought of launching a campus-wide survey could seem overwhelming, the CCJ 480-

ADR initiative offers a glimpse into the power of student research. By sponsoring a team of

supervised student researchers (by, for example, supporting service learning class projects,

thesis research, or field research internships) an academic ombuds office can obtain social

science data that could fill in the gaps left by visitor tracking data; thus, taking program

assessment and budget justification processes to the next level of sophistication. Such

participation could also raise a program’s campus profile and add value by directly contributing to

their institution’s teaching and research missions.

The findings in this report suggest a possible connection between student conflict and academic

success. In the past institutions have placed the management of student conflict issues in the

student life or student support ‘silos.’ As a result, the preponderance of resources and training for

conflict resolution was dealt to personnel in those silos. While academic personnel like faculty

and advisors receive support for classroom management, training for helping students with their

interpersonal conflicts has not been a high priority. Yet, most of the students in this study

contacted teachers and advisors for help. This suggests that faculty and mentors may serve as

‘first responders’ when students feel overwhelmed by the conflicts they have with other students.

Academic ombuds practitioners are uniquely positioned to raise awareness about the role that

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 13

academic personnel can play in helping their students. For starters, ombuds practitioners can

prioritize specialized training in effective interpersonal conflict intervention for new faculty, and

academic advisor hires. Further, they can facilitate conversation across and collaboration

between the “support” and “academic” silos. Sharing the findings from the survey reported in this

study, or the results of its replication could be the first step toward supporting a more integrated

approach to the management of student interpersonal conflicts.

Finally, the students who participated in this survey noted that interpersonal conflicts had

negatively impacted their academic efforts. The recent rise of a Student Success Movement has

provoked a significant rethinking of what constitutes success, the factors that undermine and

facilitate it, and what institutions can do to support it (Konrad, 2018). As a result, many colleges

and universities are making student success programming a high priority. Such programs provide

a diverse menu of services that attend to the mental, social and intellectual needs of students.

The experiences reported in this study suggests that conflict resolution services could bolster the

efforts of Student Success Centers and Programs. A partnership between academic ombuds

offices and their institutions' student success initiatives might be worth considering. By pooling

resources, such a partnership could support the establishment of a peer mediation program or

the development of a noncredit interpersonal conflict management class or training series geared

toward the specific needs of students.

CONCLUSION

In just one semester and with minimal resources, a team of students designed and implemented

a survey of undergraduate conflict experiences. Inspired by their personal experiences and a

sense that the research to date has not adequately addressed those experiences, they designed

an original questionnaire. While the generalizability of the findings is limited by the practical

constraints of the project, they provide insights for future investigation and practical application.

When viewed as a whole, the results suggest that interpersonal conflict is a ubiquitous

experience for college students and that most of them are, most of the time, successfully

managing them. However, some students, either due to circumstance or to their conflict

management styles, have an uncommon amount of conflict in their lives or struggle with conflicts

that have negatively colored their college experience. As experts in conflict management and

dispute resolution, academic ombuds are uniquely positioned to raise awareness about and

meaningfully address the interpersonal conflict concerns of college and university students. This

article has aspired to provide academic ombuds with ideas and resources to address the conflict

needs of their students.

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 14

REFERENCES

Adrian-Taylor, Shelley Rose, Kimberly A. Noels, and Kurt Tischler. "Conflict between international

graduate students and faculty supervisors: Toward effective conflict prevention and

management strategies." Journal of Studies in International Education 11, no. 1 (2007):

90-117.

Astor, Maggie. “7 Times in history when Students turned to activism,” The New York Times

(March 5, 2018): https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/05/us/student-protest-

movements.html, last accessed 03-20-19.

Barkat, John S. "Blueprint for success: Designing a proactive organizational ombudsman

program." Journal of the International Ombudsman Association 8, no. 1 (2015): 36-60.

Brinkert, Ross. "Conflict coaching and the organizational ombuds field." Journal of the

International Ombudsman Association 3, no. 1 (2010): 47-53.

Brockman, Julie L., Antonio A. Nunez, and Archana Basu. "Effectiveness of a conflict resolution

training program in changing graduate students style of managing conflict with their

faculty advisors." Innovative Higher Education 35, no. 4 (2010): 277-293.

Carroll, Jill. “Dealing with nasty students,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (March 31, 2003):

https://www.chronicle.com/article/Dealing-With-Nasty-Students/45135, last accessed 03-

22-19.

Claussen, Cathryn L. "The evolving role of the ‘ombuds’ in American higher education." In

Cynthia Gerstle-Pepin’s (Ed.) Survival of the Fittest: The Shifting Contours of Higher

Education in China and the US, pp. 85-100. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (2014).

Conrick, Maeve. "Problem-solving in a university setting: The role of the

ombudsperson." Perspectives: Policy & Practice in Higher Education 4, no. 2 (2000): 50-

54.

Courtain, Audrey, and Fabienne Glowacz. "Youth’s conflict resolution strategies in their dating

relationships." Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2018): 1-13.

Creasey, Gary, Kathy Kershaw, and Ada Boston. "Conflict management with friends and romantic

partners: The role of attachment and negative mood regulation expectancies." Journal of

Youth and Adolescence 28, no. 5 (1999): 523-43.

DiPaola, Benjamin M., Michael E. Roloff, and Kristopher M. Peters. "College students'

expectations of conflict intensity: A self-fulfilling prophecy." Communication Quarterly 58,

no. 1 (2010): 59-76.

Emerson, Robert M. "Responding to roommate troubles: Reconsidering informal dyadic

control." Law & Society Review 42, no. 3 (2008): 483-512.

Emerson, Robert M. "From normal conflict to normative deviance: The micro-politics of trouble in

close relationships." Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 40, no. 1 (2011): 3-38.

Fox, John. Regression Diagnostics: An Introduction (1991): Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 15

Gadlin, Howard. “The ombudsman: What’s in a name?” Negotiation Journal (January 2000): 37-

48.

Harrison, Tyler. “My professor is so unfair: Student attitudes and experiences of conflict with

faculty,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24 no. 3 (2007): 349-68.

Harrison, Tyler and Calvin Morrill. “Ombuds processes and dispute reconciliation,” Journal of

Applied Communication Research, 32 no. 04 (2004): 318-42.

Henkel, Ramon E. (1976). Tests of Significance. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kalton, G. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences: Introduction to Survey Sampling

(1983). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kafka, Alexander. “How faculty can be first responders when students need help,” The Chronical

of Higher Education (October 9, 2018): https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Faculty-

Advisers-Can-Be/244757, last accessed May 1, 2019.

Katz, Neil, Katherine Sosa, and Lin Kovack. "Ombuds and conflict resolution specialists:

Navigating workplace challenges in higher education." Journal International Ombudsman

Association (2018): 1-38.

Krumrei, Elizabeth J., Fred B. Newton, and Eunhee Kim. "A multi-institution look at college

students seeking counseling: Nature and severity of concerns." Journal of College

Student Psychotherapy 24, no. 4 (2010): 261-83.

Konrad, Matt (2018). “The Student success movement: Creating a college completion culture,”

Scholarship America: https://scholarshipamerica.org/blog/the-student-success-

movement-creating-a-college-completion-culture/, last accessed May 13, 2019.

Levine-Finely, Samantha and John Carter. “Then and now: Interviews with expert US

organizational ombudsmen,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 28 no. 2 (2010): 111-39.

Lembo, Katie. “An open letter to teachers who are rude to their students,” The Odyssey

(December 4, 2016): https://www.theodysseyonline.com/open-letter-teachers-rude-

students, last accessed 03-20-19.

Mamchur, Cindy, and Florence Myrick. "Preceptorship and interpersonal conflict: a

multidisciplinary study." Journal of Advanced Nursing 43 no. 02 (2003): 188-96.

McDonald, Kristina L., and Steven R. Asher. "College students' revenge goals across friend,

romantic partner, and roommate contexts: The role of interpretations and

emotions." Social Development 22, no. 3 (2013): 499-521.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Undergraduate Enrollment,” The Condition of Education

at a Glance (May 2018): https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cha.asp, last

accessed 03-04-2019.

Punyanunt-Carter, Narissra M., and Jason S. Wrench. "Advisor-advisee three: graduate students’

perceptions of verbal aggression, credibility, and conflict styles in the advising

relationship." Education 128, no. 4 (2008): 578-88.

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 16

Ross, Shannon E., Bradley C. Niebling, and Teresa M. Heckert. "Sources of stress among

college students." Social Psychology 61, no. 5 (1999): 841-846.

Rowe, Mary. “The ombudsman’s role in a dispute resolution system, Negotiation Journal, 7 no.4

(1991): 351-62.

Rowe, Mary, and Brian Bloch. "The solo organizational ombudsman practitioner and our need for

colleagues: a conversation." Journal of the International Ombudsman Association 5, no.

2 (2012): 18-22.

Schneck, Andrea and John Zinsser. “Preparing to be valuable: Positioning ombuds programs,”

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 7 no. 01 (2014): 23-47.

Taylor, Matthew and George Sandeman. “Graduate sues Oxford University for 1M over his failure

to get a first,” The Guardian (December 2016):

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/dec/04/graduate-sues-oxford-university-

1m-failure-first-faiz-siddiqui, last accessed 03-22-19.

Tompkins Byer, Tessa. "Yea, nay, and everything in between: Disparities within the academic

ombuds field." Negotiation Journal 33, no. 3 (2017): 213-238.

Wagner, Marsha L. "The ombudsman’s roles in changing the conflict resolution system in

institutions of higher education." (1998). CNCR-Hewlett Foundation Seed Grant White

Papers, https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/seedgrant/, last accessed 03-20-19.

Willett, Lynn. "Student affairs and academic affairs: Partners in conflict resolution," pgs. 128-140

in Susan A. Holton’s (ed.) Mending the Cracks in the Ivory Tower (1998): Anker

Publishing, Bolton, MA.

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 17

AUTHOR BIOS

Dr. Phoebe Morgan earned her PhD in Justice Studies from Arizona State University-Tempe In

1995. Since that time she has been a professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern

Arizona University-Flagstaff. From 2008 until 2011 she coordinated the Faculty Ombuds Office

and earned her COOP certification in 2012. She chaired the Department of Criminology and

Criminal Justice from 2015 until 2018. She has published research on the topics of litigation

decision making, complaint processing, and dispute resolution. She currently teaches college

classes about the courts and alternatives to dispute resolution and supervises individualized

undergraduate and graduate research projects. She regularly provides sexual harassment

prevention training workshops to employers like Coca-Cola Distribution and SDB Construction,

Inc. She serves the local community by offering free interpersonal conflict management classes

and is a volunteer court appointed special advocate (CASA) for Coconino County.

(phoebe.morgan@nau.edu)

(phbmrgn@gmail.com)

Heather Foster earned a Master’s of Science in Applied Criminal Justice from Northern Arizona

University-Flagstaff in 2017. Her thesis, “How do video games normalize violence? A qualitative

content analysis of popular video games,” is among ProQuest’s 25 most-accessed dissertations

and theses. She currently works for the Santa Barbara California Zoo.

(heather_foster@yahoo.com)

Brian Ayres holds a BS in Criminology and Criminal Justice from Northern Arizona University-

Flagstaff (2014). Mr. Ayres aspires to attend law school and is currently a fraud analyst for the

Attorney General of Florida.

(Bayres54@gmail.com)

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 18

APPENDIX

CAMPUS SURVEY: UNDERGRADUATE DISPUTE EXPERIENCES

Thank you for taking the time to participate in this questionnaire. The purpose of this survey is to assess

the current dispute resolution of students. Your answers are anonymous and will not be associated with

your identity. Your participation is voluntary and you may choose to quit at any time without

consequences. You must be at least 18 years of age and an enrolled at this university. Completing

this questionnaire signifies your agreement to participate in this survey. This questionnaire was created

by CCJ undergraduate to fulfill course requirements. If you have questions or concerns regarding this

survey please contact the instructor at XXX-XXX-XXXX. For any questions or concerns regarding your

rights as a research participant, contact the Human Research Protection Office at XXX_XXX_XXXX.

I. DEMOGRAPHICS

For the next three questions, fill in the blank.

Q1. _____ How many semesters have you taken classes at NAU?

Q2. _____ How many people do you share a living space with?

Q3. _____ What is your age?

For the next seven items, check the box that best fits your answer.

Q4. What is your sex?

1.☐ Male 2.☐ Female

Q5. In which college is your major?

1. ☐ Arts & Letters

2. ☐ Education

3. ☐ Engineering/Forestry/N. Sciences

4. ☐ Health and Human Services

5. ☐ Education

6. ☐ Social & Behavioral Sciences

7. ☐ Graduate College

8. ☐ Business

9. ☐ University College

10. ☐ Extended Campuses

Q6. Do you live on or off campus?

1. ☐ On-campus 2. ☐ Off-campus

Q7. What best describes your residency status:

1. ☐ In-state resident

2. ☐ Out-of-state resident

3. ☐ International

Q8. Are you a transfer student?

1. ☐ Yes 2. ☐ No

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 19

Q9. On which campus do you take most of your classes?

1. ☐ Community College Campuses

2. ☐ Main Campus

3. ☐ An Extended Campus (online or statewide campus)

Q10. What ethnicity do you classify yourself as?

1. ☐ Native American

2. ☐ Asian American

3. ☐ African American

4. ☐ Hispanic American

5. ☐ International

6. ☐ White

7. ☐ Mixed (Two or more of any category)

8. ☐ Unknown

II. CONFLICTS INVOLVING UNIVERSITY PERSONNEL

The items in this section focus on your experiences regarding disputes or disagreements about university

policies and rules, as well as the decisions and actions of university personnel.

Q11. Have you ever had, or do you currently have, a dispute/disagreement about a university policy or

rule?

1. ☐ Yes 2. ☐ No

Q12. Have you ever had or do you currently have a dispute/disagreement about how university

personnel has implemented university policies, rules; or the decisions of a university representative?

1. ☐ Yes 2. ☐ No

Q13. If you answered “yes” to Q11 or Q12, which of the following are/were relevant?

Check all that apply.

1. ☐ Your Class grade

2. ☐ Academic Advising

3. ☐ Admissions

4. ☐ Association of Students

5. ☐ Athletics

6. ☐ BB Learn

7. ☐ Bookstore

8. ☐ Campus Health Services

9. ☐ Theft or Assault

10. ☐ Library Services

11. ☐ Dining Services

12. ☐ Disability Resources

13. ☐ Education Abroad

14. ☐ Extended Campuses

15. ☐ Family Housing

16. ☐ Financial Aid

17. ☐ Campus Health Service

18. ☐ Parking/Shuttle Services

19. ☐ Gateway Student Center

20. ☐ Tuition Benefits

21. ☐ Graduate Admissions

22. ☐ Campus Payment Card

23. ☐ Campus Maintenance

24. ☐ Billing/Payment Services

25. ☐ Greek Life

26. ☐ Intramural Activities

27. ☐ Course Registration Services

28. ☐ Meal Plans

29. ☐ E-mail Services

30. ☐ Office of Parent Services

31. ☐ Parking Services

32. ☐ Fees or Charges

33. ☐ Resident Life

34. ☐ Military Benefits

35. ☐ Student Life

36. ☐ Student Senate

37. ☐ Online Access

38. ☐ Study Abroad

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 20

39. ☐ Transfer Credits

40. ☐ Parking & Shuttle

41. ☐ Tuition Benefits

42. Other: ____________________

Q14. If you answered “yes” to Q11 or Q12, which of the following best describes the general nature of

your most recent dispute/disagreement regarding university policies, rules or the decisions of university

personnel? Check all that apply.

1. ☐ Financial/Monetary

2. ☐ Employment

3. ☐ Entitlement to Resources/Support

4. ☐ Instruction/Academic Support

5. ☐ Lifestyle choices

6. ☐ Parking

Q15. If you answered “yes” to Q11 or Q12, think about the most recent dispute or disagreement you have

had university personnel and the impact it may have had on your academic success while enrolled at

this university. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 = not serious at all, and 5 = very serious, rate the seriousness

of the impact for each type of consequence. For each item circle the number that best indicates your

rating.

1. Unable to concentrate on schoolwork

1

2

3

4

5

2. Had to miss a class

1

2

3

4

5

3. Unable to meet a class deadline

1

2

3

4

5

4. Didn’t do my best work on a course assignment

1

2

3

4

5

5. Had to drop or withdraw from a class

1

2

3

4

5

6. Had to delay graduation

1

2

3

4

5

7. Thought about dropping out of college

1

2

3

4

5

8. Thought about transferring to another university

1

2

3

4

5

9. Unable to perform well at on-campus job

1

2

3

4

5

III. INTERPERSONAL DISPUTES WITH OTHER STUDENTS

The items in this section focus on your disagreements or disputes you have had with other students

while enrolled at this university.

Q16. Looking back over the past year, estimate of the number of disputes or disagreements you have

had with the following:

1. _____ Roommates

2. _____Classmates

3. _____ Friends

4. _____ Teammates

5. _____ Boyfriend or Girlfriend

6. _____ Co-workers

7. _____ Stranger

Q17. If you have had a dispute or disagreement with another student while enrolled at this university,

think about how the conflict impacted your daily life. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 = not serious at all and 5

= very serious, rank the overall seriousness of the impact on your daily life for each type of person

you have had a disagreement or dispute with. Indicate your rating by circling the number:

1. Roommates

1

2

3

4

5

2. Classmates

1

2

3

4

5

3. Friends

1

2

3

4

5

4. Teammates

1

2

3

4

5

5. Boyfriend, Girlfriend or Spouse

1

2

3

4

5

6. Co-workers

1

2

3

4

5

7. Stranger

1

2

3

4

5

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association

JIOA 2019 | 21

Q18. Below is a list of behaviors that can undermine a student’s effort to graduate in a timely manner. If

you have had a dispute or disagreement with anyone at this university – i.e., university personnel or

other student while enrolled at this university, think about the extent to which the conflict may have

caused any of the nine behaviors. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 = not serious at all and 5 = very serious,

rate the seriousness of the impact any had on your academic success. Circle the number that best

indicates your rating.

1. Unable to concentrate on schoolwork

1

2

3

4

5

2. Had to miss a class

1

2

3

4

5

3. Unable to meet a class deadline

1

2

3

4

5

4. Didn’t do my best work on a course assignment

1

2

3

4

5

5. Had to drop or withdraw from a class

1

2

3

4

5

6. Had to delay graduation

1

2

3

4

5

7. Thought about dropping out of college

1

2

3

4

5

8. Thought about transferring to another university

1

2

3

4

5

9. Unable to perform well at on-campus job

1

2

3

4

5

IV. DISPUTE RESOLUTION ASSISTANCE

While the previous set of questions focused on disputes or disagreements you have had while enrolled at

this university, this section focuses on your experience seeking assistance in resolving them.

Specifically, the following items seek your experiences and opinions regarding the efforts of authorities

(university personnel, your parents, lawyers or police, for example) to help students resolve their

disputes.

Q19. Take a moment to think about your most recent dispute you have had while enrolled at this

university. Which of the following did you contact for assistance to finding a resolution? Check all that

apply.

1. ☐ Faculty

2. ☐ Teachers Assistant

3. ☐ Lab Assistant

4. ☐ Athletic Coach

5. ☐ Resident Advisor

6. ☐ College Dean

7. ☐ Campus Program Coordinator

8. ☐ Provost

9. ☐ Student Legal Aid

10. ☐ Academic Advisor

11. ☐ Police Officer

12. ☐ Mentor

14. ☐ Office Staff

15. ☐ Office Director

16. ☐ University Vice President

17. ☐ Office Staff

18. ☐ Other Student

19. ☐ Parent

20. ☐ Personal or family lawyer

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association Morgan, Foster, and Ayres

22

Q20. In thinking about your most recent disagreement or dispute with anyone associated with the

university (i.e. conflicts with university employees, or with other students), has it been resolved?

1. ☐ Yes

2. ☐ No

3. ☐ Unsure

4. ☐ Still In the Process

If you have ever asked university personnel to help you resolve a dispute or disagreement, rate their

effort(s) on a scale of 1-5 with 1 = not satisfied and 5 = very satisfied. Circle the number that best

indicates your rating.

Q21.

Satisfaction with the resolution process

1

2

3

4

5

Q22.

Satisfaction with the end result of your resolution effort

1

2

3

4

5

Q23.

Satisfaction with university personnel’s resolution efforts

1

2

3

4

5

For the next three questions, seek your opinion about the different types of conflict resolution models that

are commonly found on college and university campuses. Reflecting on the types of

disagreements/disputes you have had while enrolled in this university, on a scale of 1-5 rate the

importance of each quality for a satisfactory resolution with 1 = not important at all and 5= very

important. Circle the number that best indicates your rating.

Q24.

A neutral party does not decide which side is right or wrong, but works

to make sure the process is fair for everyone. How important is it to you

that the person helping you find a resolution remains neutral?

1

2

3

4

5

Q25.

A conflict resolution professional is someone who has obtained a

certificate or a degree that allows them to specialize in a conflict

resolution practice. How important is it to you that the person helping you

find a resolution is a credentialed professional?

1

2

3

4

5

Q26.

A peer mediator is someone who draws upon their personal experience

to help those like them resolve their disputes. Peer mentors are unpaid

volunteers who receive some training. How important is it to you that the

person helping you find a resolution is another student who has

experienced conflicts like yours?

1

2

3

4

5

V. Open Response

Q27. Is there more you would like us to know? To protect your anonymity, we ask that you avoid sharing

information that might reveal you identity or the identity of anyone else.

Thank you for completing this questionnaire.