RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 1

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA

Date of publication: 12 December 2022

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 2

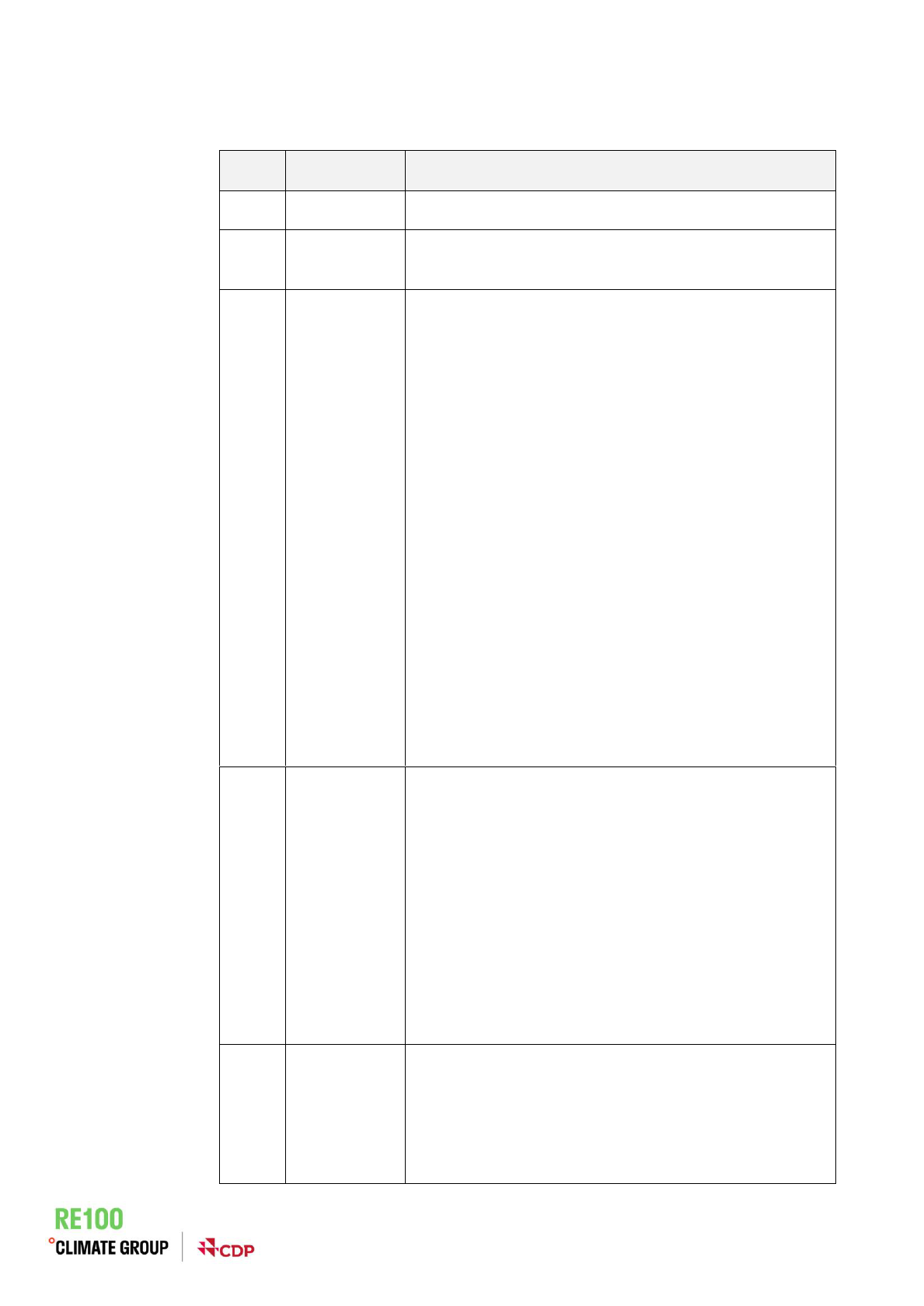

VERSION CONTROL

Version

Revision date

Revision summary

1.0

27 April 2016

First public version

2.0

January 2018

Updates to the list of Technical Advisory Group members and

formatting changes

3.0

22 March 2021

Minor edits about reporting

Additional information on third-party verification of consumption

Updates to recognized renewable electricity technologies: additional

specifications on biomass and hydropower

Updates to recognized renewable electricity procurement types: two

new types of passive procurement recognized

Additional information on making credible claims (previously called

‘Making Unique Claims’)

New reference to the external document RE100 Market Boundary

Criteria document version May 2019

Details on how to make claims for each procurement type have been

moved to a table in the Annex

New information on active vs. passive procurement of renewable

electricity

New text about the RE100 materiality threshold provisions, taken

from the materiality threshold document of December 2019

New information about maximizing impact

Minor edits to the list of TAG members

4.0

October 2022

Updates to recognized renewable electricity technologies: additional

specifications for sustainable hydropower

Revisions to recognized renewable electricity procurement types

Revisions to market boundary definitions in Europe

Introduction of a commissioning or re-powering date limit for

procurement of renewable electricity, with exemptions for certain

procurement types and grandfathering of eligible contracts

Formatting and structure changes for clarity

New introduction

Updates to the list of TAG members

4.1

12 December 2022

Correction in Appendix B to remove Ireland from the list of countries

in an international single market for renewable electricity in Europe

New appendix added to clarify guidance around operational

commencement dates eligible for grandfathering

Clarification added in Appendix C around biomass re-powering

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 3

Table of contents

Section One: Definitions of terms

5

Section Two: Introduction

6

1. What are the RE100 technical criteria?

6

2. What are the RE100 technical criteria based on?

6

Section Three: Recognized renewable energy resources

7

Section Four: Recognized procurement types for renewable electricity

8

1. Self-generation from facilities owned by the company

9

2. Direct procurement (contracts with generators)

2.1 Physical power purchase agreement (physical PPA)

2.2 Financial (virtual) power purchase agreement (financial/virtual PPA)

9

3. Contracts with electricity suppliers

3.1 Project-specific supply contract with electricity supplier

3.2 Retail supply contract with electricity supplier

10

4. Unbundled procurement of energy attribute certificates (EACs)

11

5. Passive procurement

5.1 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid, supported by EACs

5.2 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid in a market with at least a 95%

renewable generation mix and where there is no mechanism for specifically

allocating renewable electricity

12

Section Five: Requirements for procurement

14

1. Credibility of claims

14

2. Impact in procurement of renewable electricity

2.1 Impactful procurement

2.2 Commissioning or re-powering date limit, with exemptions and grandfathering

14

Section Six: Additional provisions

17

1. Organizational boundaries for electricity consumption

17

2. Material consumption of electricity

17

3. Third-party verification of consumption of renewable electricity

18

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 4

Appendix A: Credible claims to use of renewable electricity

21

Appendix B: Market boundaries

25

Appendix C: Re-powering of projects

28

Appendix D: Commissioning or re-powering date limit worked examples

29

Appendix E: Select studies in identifying procurement types

31

Appendix F: Operational commencement dates of contracts eligible for

grandfathering

33

Appendix G: Links with the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard

34

Appendix H: RE100 Technical Advisory Group (TAG) members

36

Appendix I: Additional resources and contact information

37

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 5

Section One: Definitions of terms

Renewable generator

An entity that owns or operates renewable electricity generation

projects.

Project, or facility

The physical plant generating electricity.

Generation

The electricity generated by a project, or facility.

Corporate buyer

An entity that is procuring renewable electricity for its operations and

may be seeking to make claims to its use. RE100 member companies

are corporate buyers.

Supplier, or utility

An entity that supplies electricity to corporate buyers.

Energy attributes

The physical characteristics and the environmental benefits of

electricity generation determined by those physical characteristics.

Energy attributes include, but are not limited to:

• Static information about the generation (technology type,

nameplate capacity, location, commissioning date, project

name, etc.).

• The released CO2e emissions associated with the

generation.

• The time and date (vintage, or sometimes a timestamp) of

generation.

Energy attribute

certificates (EACs)

Standardized, tradable instruments issued to a unit of generation

(generally, one MWh) which are used to aggregate and track energy

attributes. Depending on the system that issues them and the market

where they are used, corporate buyers may purchase them bundled

with or unbundled from the underlying generation to secure the

property rights to energy attributes. EACs are often interchangeably

referred to as Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs).

Bundled procurement

When energy and energy attributes are procured together, in the

same transaction.

Unbundled

procurement

When energy and energy attributes are procured separately, in

different transactions.

Project-specific

procurement

Procurement from specified projects. Project-specific supplies always

have complete transparency regarding the energy attributes in those

supplies. The projects procured from throughout the term of a project-

specific contract are stipulated in the contract. Project-specific

supplies typically use longer contract lengths.

Retail procurement

Procurement of an ‘off-the-shelf’, standardized renewable electricity

product. Project-specificity is not a requirement for retail procurement.

The supplier of a retail supply may vary the projects used in the

supply over the term of the contract. Retail supplies typically have

less transparency regarding the energy attributes in those supplies

and use shorter contract lengths.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 6

Section Two: Introduction

1 What are the RE100 technical criteria?

The RE100 technical criteria are the rules that member companies of the RE100

campaign observe when procuring renewable electricity and defining their

progress towards their RE100 targets. The technical criteria may also be used by

any corporate buyer as a guide for procurement of renewable electricity and

making claims to its use.

The RE100 technical criteria exist in the absence of a consistent global

framework that:

• Defines which energy resources are renewable;

• Defines requirements for credible claims to use of renewable electricity,

including specific market boundaries;

• Outlines appropriate boundaries for organization-wide targets on renewable

electricity consumption;

• Defines material consumption of electricity in the pursuit of these targets;

• Calls for third-party verification of consumption of renewable electricity; and

• Specifies impact in procurement of renewable electricity.

Renewable electricity markets are dynamic and vary country by country. To reflect this, RE100 may

introduce electricity accounting and reporting rules, provide regional or national context, and

provide further briefings on emerging best practice.

The RE100 technical criteria are set by the RE100 Technical Advisory Group (TAG) in consultation

with member companies, other stakeholders, and with the approval of the RE100 Project Board. A

list of TAG members is given in Appendix H. The TAG contributes to the development of the

technical criteria, but the entirety of the technical criteria may not reflect each TAG member’s views.

The technical criteria may be periodically revised for RE100 to maintain its mission as a global

leadership initiative of corporate buyers accelerating the transition to carbon-free grids by 2040.

The technical criteria do not exist purely as a reporting standard for corporate claims to use of

renewable electricity, but as the principles for corporate buyers to themselves contribute to the

decarbonization of grids through their direct actions, and through the signals to markets and

policymakers that their actions send.

2 What are the RE100 technical criteria based on?

The technical criteria are mostly an interpretation of the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard market-

based scope 2 accounting guidance. They apply principles for market-based greenhouse gas

emissions claims to renewable electricity usage claims by recognizing that both types of claims are

made possible by the same market-based instruments.

The technical criteria, in almost all cases, require a market-based instrument which gives a

corporate buyer making a claim to use of renewable electricity the property rights to renewable

electricity attributes. The procurement types recognized by the technical criteria, in almost all

cases, are categorizations of different contractual arrangements which convey these attributes to

corporate buyers.

Please see Appendix G for more information around the relationship between the technical criteria

and the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 7

Section Three: Recognized renewable

energy resources

RE100 considers electricity generated from the following energy resources

to be renewable:

• Wind;

• Solar;

• Geothermal;

• Sustainably sourced biomass (including biogas); and

• Sustainable hydropower.

RE100 does not include hydrogen in this list because hydrogen is not an energy

resource. Rather, it is an energy carrier which is manufactured, and has an

underlying energy resource as an input. Hydrogen is therefore only renewable if

the energy resource used in its manufacture is renewable. Similarly, RE100 does

not include energy storage in this list because energy storage is not an energy

resource.

Renewable electricity from biomass and hydropower can play a role in

decarbonization provided it is generated sustainably. RE100 only recognizes

renewable electricity generated from biomass and hydropower that is also

sustainable. RE100 recommends that this sustainability is proven through third-

party certification.

A non-exhaustive list of standards providing such certification includes:

• ISO 13065:2015 (specifies principles, criteria, and indicators for the bioenergy

supply chain to facilitate assessment of environmental, social and economic

aspects of sustainability)

• The Green-e® Renewable Energy Standard for Canada and the United States

• The Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI)

• The Hydropower Sustainability Council’s Hydropower Sustainability Standard

The TAG will study the environmental and social sustainability of these

technologies and may introduce related recommendations and criteria as

consensus around best practices develop.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 8

Section Four: Recognized procurement

types for renewable electricity

RE100 categorizes corporate procurement of renewable electricity into five broad

types. They differ in terms of the party being contracted with (directly with a

generator or through a more conventional contract with an electricity supplier),

whether the procurement of energy and energy attributes is bundled or

unbundled, and active versus passive procurement.

1 Self-generation from facilities owned by the company

2 Direct procurement (contracts with generators)

2.1 Physical power purchase agreement (physical PPA)

2.2 Financial power purchase agreement (financial/virtual PPA)

3 Contracts with electricity suppliers

3.1 Project-specific supply contract with electricity supplier

3.2 Retail supply contract with electricity supplier

4 Unbundled procurement of energy attribute certificates (EACs)

5 Passive procurement

5.1 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid, supported by EACs

5.2 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid in a market with at least

a 95% renewable generation mix and where there is no mechanism for

specifically allocating renewable electricity

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 9

1 Self-generation from facilities owned by the company

Corporate buyers can own their own projects. Projects might be on-site or off-site, on the grid, or

entirely off-grid. Corporate buyers must retain energy attributes to claim use of renewable

electricity. This means corporate buyers can consume directly from their projects, retain the

attributes, and claim use of renewable electricity. It also means corporate buyers can sell energy to

the grid, retain the attributes, and claim use of renewable electricity.

The generation may be issued with energy attribute certificates (EACs), which corporate buyers

can use to claim use of renewable electricity. The generation may be required to receive EACs. If

EACs are not issued, corporate buyers must have contracts that give them credible claims (see

Section Five: Credibility of claims) to support their claims to use of renewable electricity.

2 Direct procurement (contracts with generators)

Direct procurement describes procurement from, and contracting with, generators

themselves. It includes two forms of power purchase agreements (PPAs).

2.1 Physical power purchase agreement (physical PPA)

A physical PPA is a contract between a corporate buyer and a generator for the supply of

renewable electricity. A physical PPA can characterize purchases from on-site projects owned by

third parties, off-site projects to which there is a direct line, or off-site grid-connected projects. A

physical PPA typically uses a long-term contract.

Physical PPAs do not necessarily need to be bilateral between the corporate buyer and the

generator. A bilateral PPA requires the corporate buyer to also take responsibility for the off-take of

the power itself, including managing the moving and scheduling of the power to the corporate

buyer’s load, or into the wholesale power market (if the project is grid-connected). The corporate

buyer may need to be licensed to be able to do this. Alternatively, a trilateral PPA can involve an

additional party which is responsible for the off-take of the power from the project. This third party is

often an electricity supplier. A trilateral PPA may be advertised as a ‘retail PPA’, ‘sleeved PPA’, or a

‘third-party PPA’.

The generation may be issued with energy attribute certificates (EACs), which corporate buyers

can use to claim use of renewable electricity. If EACs are not issued, corporate buyers must have

contracts that give them credible claims (see Section Five: Credibility of claims) to support their

claims to use of renewable electricity.

2.2 Financial power purchase agreement (financial/virtual PPA)

A financial PPA (often called a virtual PPA – VPPA) is a purely financial transaction in which a

corporate buyer assumes market risk related to the sale of a generator’s electricity and receives

energy attributes. This can be done through a contract for difference, where the generator

exchanges the risk of selling the project’s generation to the wholesale market at a variable rate with

a fixed-price cash flow agreed with the corporate buyer. The corporate buyer therefore off-takes

market risk the generator would be exposed to by selling power at the fluctuating wholesale energy

price, and in return is entitled to the energy attributes.

Because a financial PPA is only a financial instrument, the corporate buyer must still separately

procure electricity for its operations. It is therefore a form of unbundled procurement. A financial

PPA can serve as a hedge for fluctuating electricity costs, and some corporate buyers may realize

a financial benefit from using them. A financial PPA typically uses a long-term contract.

The generation may be issued with energy attribute certificates (EACs), which corporate buyers

can use to claim use of renewable electricity. If EACs are not issued, corporate buyers must have

contracts that give them credible claims (see Section Five: Credibility of claims) to support their

claims to use of renewable electricity.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 10

3 Contracts with electricity suppliers

A contract with a supplier describes a conventional supply arrangement with an

electricity supplier for the supply of renewable electricity. Energy and energy

attributes are bundled together in their delivery to the corporate buyer.

RE100 recognizes two types of contracts with electricity suppliers: project-

specific, and retail. Appendix E contains guiding questions for corporate buyers

needing to identify whether a particular supply must be characterized as project-

specific or retail.

3.1 Project-specific supply contract with electricity supplier

A project-specific contract with a supplier describes an arrangement whereby the supplier procures

from specified projects on behalf of the corporate buyer. Often, the supplier holds a power

purchase agreement. The contract may be advertised as a ‘green tariff’, has complete transparency

regarding the energy attributes in the supply (meaning the corporate buyer always knows exactly

which specific projects they are purchasing from through their electricity supplier), and typically

uses a longer contract length.

The generation may be issued with EACs, which corporate buyers can use to claim use of

renewable electricity. The supplier may transfer the EACs to corporate buyers or otherwise redeem,

retire, or cancel them on behalf of corporate buyers. If EACs are not issued, corporate buyers must

have contracts that give them credible claims (see Section Five: Credibility of claims) to support

their claims to use of renewable electricity.

3.2 Retail supply contract with electricity supplier

A retail contract with a supplier describes an ‘off-the-shelf’ arrangement with an electricity supplier

for the supply of renewable electricity. The corporate buyer usually pays a per-kilowatt hour

premium through an additional line item on their monthly electricity bill for the renewable electricity.

This contract may be advertised as a ‘green electricity product’, has less transparency regarding

the energy attributes in the supply, and typically uses a shorter contract length. The supplier may

vary the projects from which energy attributes are sourced throughout the contract.

The generation may be issued with EACs, which corporate buyers can use to claim use of

renewable electricity. The supplier may transfer the EACs to corporate buyers or otherwise redeem,

retire, or cancel them on behalf of corporate buyers. If EACs are not issued, corporate buyers must

have contracts that give them credible claims (see Section Five: Credibility of claims) to support

their claims to use of renewable electricity.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 11

4 Unbundled procurement of energy attribute certificates

(EACs)

Energy attribute certificates (EACs) can be purchased alone, separate from the

underlying generation they are issued to, and separate from corporate buyers’

procurement of electricity for their operations.

Corporate buyers can purchase EACs

1

to pair with their consumption of purchased grid electricity.

This permits a claim to having consumed electricity with the attributes conveyed by the EACs

2

. The

EACs must be issued to generation located in the same market for electricity as the electricity

supply being decarbonized by the corporate buyer

3

. A purchase of renewable electricity generated

in one market cannot be equated to its consumption in a different market.

EACs can be procured through short or long-term contracts, with varying degrees of project-

specificity. EACs are sometimes procured through brokers and trading platforms, making for

transactions that are less complex than those in other procurement types.

Unbundled EACs can only ever present an additional cost on top of corporate buyers’ separate

electricity purchases. This is a key point of distinction between long-term contracts for unbundled

EACs and financial PPAs, which can sometimes realize a financial benefit.

1

The EACs purchased must be from EAC systems that enable credible claims. RE100 maintains a

list of such EAC systems in its frequently asked questions. However, EACs from any system can be

purchased if their user understands the system to enable credible claims following a review of the

RE100 credible claims paper.

2

Unbundled EACs cannot be used to decarbonize electricity from a non-renewable project

(e.g., a CHP system) when the project is owned by the company (therefore, the emissions

from it are in scope 1), or when the project is on-site or when there is a direct line to the

project (therefore, the electricity is not sourced from the grid).

EACs are scope 2 instruments indicating renewable electricity has been generated and fed into the

grid. Using them to decarbonize scope 1 emissions does not align with greenhouse gas emissions

accounting practice. Similarly, it is inconsistent to claim that a purchase of EACs from renewable

electricity which is fed into the grid can be matched with consumption of electricity from a source

other than the grid. The electricity generated by CHP systems can only be considered renewable if

the fuel used to generate the electricity is renewable. Either a physical supply of a renewable fuel or

a purchase of an energy attribute certificate for a renewable fuel (for example, a biogas certificate)

which observes relevant credibility principles (such as market boundaries) is necessary.

More information on this provision is available in RE100’s frequently asked questions.

3

See Appendix B for RE100’s precise market boundary definitions.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 12

5 Passive procurement

RE100 recognizes two types of passive procurement. The first is for corporate

buyers with credible claims to passively delivered market-based instruments

(EACs) which are in their default supplies. The second is for corporate buyers on

highly renewable grids where no market-based instruments exist.

5.1 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid, supported

by EACs

This is the renewable electricity in the electricity utility/supplier mix that has not been voluntarily

procured by corporate buyers but is delivered by default. Corporate buyers can claim use of default

delivered renewable electricity if, and only if, an equivalent amount of EACs is retired by the

utility/supplier. Corporate buyers wishing to claim use of this renewable electricity must seek

relevant information from their utility/supplier to justify their claims.

Default supplies can include renewable electricity supplied under a compliance mandate. However,

the existence alone of such a mandate is not justification for corporate buyers to claim use of

renewable electricity. Corporate buyers must verify how their utilities/suppliers are complying with

the mandate. In the United States, Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) require that a specified

percentage of the electricity that utilities supply comes from renewable resources, and that

utilities/suppliers retire Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) on behalf of their customers for that

percentage. In some cases, these programs allow for alternative compliance routes, multipliers,

and other mechanisms that do not deliver renewable electricity to corporate buyers. Another

example in Australia is the default supply of renewable electricity by utilities/suppliers retiring Large-

scale Generation Certificates (LGCs) under the Renewable Energy Target (RET). Again, corporate

buyers must verify that their utilities/suppliers are retiring LGCs rather than using an alternative

compliance route such as paying a shortfall charge. This procurement type is not applicable in most

markets and corporate buyers wishing to use it must have evidence to support their claims.

For the avoidance of doubt, claims to default delivered renewable electricity, supported by EACs,

require an absence of voluntary procurement of renewable electricity. Corporate buyers can only

claim default delivered renewable electricity where they have a contract for a supplier’s default

supply. If a corporate buyer consumes 100 MWh, 60 MWh of which is supplied through a contract

for renewable electricity, and 40 MWh of which is supplied through a default supply, the corporate

buyer can only claim the default delivered renewable electricity, supported by EACs, present in the

40 MWh conveyed by the default supply

4

.

It is essential that claims to use of default delivered renewable electricity remain unique and

exclusive. Some markets place RPS-type compliance mandates on utilities but allow those utilities

to also sell that renewable electricity to voluntary corporate buyers actively procuring it (for

example, through the Green Premium contracts available in the Republic of Korea). Therefore, the

renewable electricity procured by utilities to meet their compliance mandate is not present in a

default supply. Claims to default delivered renewable electricity cannot be made using compliance

mandates on utilities as a justification in these instances.

4

https://resource-solutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Accounting-for-Standard-Delivery-

Renewable-Energy.pdf

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 13

5.2 Default delivered renewable electricity from the grid in a market

with at least a 95% renewable generation mix and where there is

no mechanism for specifically allocating renewable electricity

Corporate buyers can count all their electricity consumption from the grid as renewable in a market

when the generation mix is over 95% renewable and when there is no mechanism for actively

sourcing renewable electricity from the grid. This only applies when the entire market’s grid is at

or above this percentage. This procurement type does not apply to regions within markets (for

example, where one state or province is over 95%) and does not apply to electricity

consumption from sources other than the grid.

Other markets with a high percentage of renewables on the grid such as Norway and Iceland are

not eligible for passive claims because they have mechanisms for specifically allocating renewable

electricity to corporate buyers.

Passive claims are also not credible in markets that have a highly renewable domestic generation

mix, but also import significant amounts of electricity, such as Nepal.

At present, RE100 has found that only Paraguay, Uruguay, and Ethiopia meet these criteria.

The list of countries where passive claims from the grid are recognized is subject to change as

markets and grids evolve.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 14

Section Five: Requirements for

procurement

1 Credibility of claims

A credible claim to use of renewable electricity must be based on:

• Credible generation data

5

;

• Attribute aggregation

5

;

• Exclusive ownership (no double counting) of attributes

5

;

• Exclusive claims (no double claiming) on attributes

5

;

• Geographic market limitations of claims

5

; and

• Vintage limitations of claims. The period of generation used to claim use of renewable electricity

must be reasonably close in time to the period over which a claim to use of renewable electricity

is made. RE100 does not define ‘reasonably close’

5

.

2 Impact in procurement of renewable electricity

RE100’s aim is for corporate buyers to accelerate the transition to zero-carbon

grids. Corporate buyers can contribute to this transition either directly, through

the actions they take to add new renewable electricity capacity, and/or indirectly,

through the signals they send to markets and policymakers with their demand for

voluntarily procured renewable electricity.

2.1 Impactful procurement

RE100 holds that self-generation or procurement from new projects through long-term, direct, or

project-specific contracts, are central to corporate buyers themselves driving the transition to zero-

carbon grids. Where corporate buyers make one-time purchases of unbundled EACs, they can

make a preference on location, technology, project, or timing to increase the impact of these

purchases.

Additional, voluntary labels can be sought for EACs which might, for example, guarantee that the

EACs are from recently commissioned projects. A non-exhaustive list of these labels includes the

Green-e ®, EKOenergy ®, and Gold Standard ® labels. They can strengthen the impact and

credibility of any procurement type that conveys EACs.

RE100 recognizes that impactful procurement is not always possible in all markets.

Corporate buyers should engage with suppliers and policymakers to remove barriers to

impactful procurement and otherwise procure renewable electricity with the highest impact

possible where they operate.

5

Appendix A discusses each of these features more broadly. Appendix B outlines RE100’s precise

market boundary definitions. The RE100 credible claims paper also exists as a standalone

document corporate buyers can use as an aid in their procurement and in making claims.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 15

2.2 Commissioning or re-powering date limit, with exemptions and

grandfathering

The RE100 technical criteria require corporate buyers’ procurement of renewable electricity

to observe a fifteen-year

6

commissioning or re-powering

7

date limit, or to be one of the

following:

• Self-generation (procurement type 1)

• Physical power purchase agreements with on-site projects or off-site projects to which there is a

direct line with no grid transfers (a subset of procurement type 2.1)

• Long-term project-specific contracts the corporate buyer has entered into as the original off-

taker from the project(s), and extensions of those contracts, even if they exceed fifteen

years in length, including:

• Physical power purchase agreements with off-site grid-connected projects (a subset of

procurement type 2.1)

• Financial power purchase agreements (procurement type 2.2)

• Project-specific contracts with electricity suppliers (procurement type 3.1)

• Project-specific contracts for unbundled EACs (a subset of procurement type 4)

• Claims to default delivered renewable electricity (procurement types 5.1 and 5.2)

• Grandfathered contracts with operational commencement dates

8

before 1 January 2024

Corporate buyers may exempt procurement of renewable electricity up to a threshold of 15%

of their total electricity consumption from the requirements above.

In other words, if a corporate buyer is only procuring 15% renewable electricity, no procurement is

subject to a commissioning or re-powering date limit. A corporate buyer procuring 50% renewable

electricity may exempt 15% (in terms of its total consumption) and must subject the remainder of its

procurement of renewable electricity (35% of its total consumption) to the requirements above. A

corporate buyer procuring 100% renewable electricity may exempt 15% of its procurement and

must subject the remainder of its procurement (85% of its total consumption) to the requirements

above

9

.

The RE100 technical criteria do not recognize additional procurement of renewable electricity from

projects commissioned or re-powered more than fifteen years ago beyond the 15% threshold.

These requirements for impactful procurement apply to corporate buyers’ global procurement.

Corporate buyers may choose in which markets to use the procurement types subject to the 15%

threshold. RE100 recommends that corporate buyers voluntarily phase-out their use of the 15%

threshold as quickly as possible.

6

‘Fifteen years’ is defined as on or after 1 January of the year fifteen years prior to the claim to use

of renewable electricity. For example, a claim to use of renewable electricity over January-

December 2025 must be based on procurement from projects commissioned or re-powered on or

after 1 January 2010.

7

See Appendix C for RE100’s guidance on re-powering of projects.

8

See Appendix F for definitions of operational commencement in the context of bundled or

unbundled procurement.

9

See Appendix D for an illustration of how this rule impacts corporate buyers procuring different

amounts of renewable electricity.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 16

2.2.1 Entry into force

Starting with the 2023 disclosure cycle, RE100 members will be required to disclose the

commissioning or re-powering dates of the projects in their supplies of renewable electricity,

including disclosure of an ‘unknown’ date where the information is not available.

Each RE100 member will be assessed against the fifteen-year commissioning or re-powering date

limit when they submit their first disclosures to RE100 that cover twelve months starting on or after

1 January 2024. In each disclosure cycle, the most common reporting period selected by RE100

members is January to December of the previous year. Therefore, it is expected that members

reporting on their procurement for 1 January to 31 December 2024 in the 2025 disclosure cycle will

first have their adherence to the fifteen-year commissioning or re-powering date limit assessed in

the 2025 annual disclosure report, published in January 2026.

The RE100 technical criteria are reviewed and updated every two years. If compelling, data-

supported reasons arise showing that changing the criteria is required for market growth and

sustainability, they will be considered during the review cycle.

2.2.2 Approaches to reporting on commissioning or re-powering dates

For some procurement, it can be difficult to establish precisely which projects renewable attributes

are being sourced from. This may especially be the case with retail contracts with suppliers which

have low transparency regarding the energy attributes in those supplies. Corporate buyers should

insist that their suppliers improve the transparency of such products so that they can use

commissioning or re-powering dates as a selection criterion when choosing which suppliers to

contract with.

Some supplies may be transparent with respect to commissioning or re-powering dates, but include

many projects (even when the supplies are project-specific). In these cases, it may be burdensome

to individually report each project and the volume of renewable electricity procured from it. RE100

recommends its members report in as much detail as possible. Where members cannot or do not

wish to disaggregate their reporting by commissioning or re-powering date, they must report the

commissioning or re-powering date of the oldest project in a given supply.

If a commissioning or re-powering date is unknown or not reported, the procurement counts

towards the 15% threshold which is exempt from a commissioning or re-powering date limit.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 17

Section Six: Additional provisions

1 Organizational boundaries for electricity consumption

An organization-wide target to increase renewable electricity consumption must

define a boundary for the organization’s use of electricity. The RE100 technical

criteria rely on greenhouse gas emissions accounting guidance for this definition.

An organization’s electricity consumption is defined as the electricity consumption that underlies:

• All scope 2 emissions associated with purchased electricity; and

• All scope 1 emissions associated with the generation of electricity by the organization, for the

organization’s consumption (this excludes use of fossil fuels for transport, the production of

heat, or other uses not involving electricity production).

The activities with emissions in the above scopes are identified following the application of a GHG

boundary-setting approach. The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard provides guidance for:

• An operational control approach;

• A financial control approach; and

• An equity share approach.

Organizations must choose an emissions boundary-setting approach, either prescribed by the GHG

Protocol or another, to identify the activities under their direct control and thus the underlying

electricity consumption in the scope of an RE100 target.

2 Material consumption of electricity

RE100 members make a commitment to use 100% renewable electricity across

their global operations. This requires them to act in every market they operate in.

As a leadership initiative, RE100 can be unashamedly challenging for members.

Nevertheless, some members have small operations in some markets that have negligible impact

on local demand. In markets where it is not technically feasible to source renewable electricity (for

example, because the load is small or because of landlord-tenant issues), such loads can have a

disproportionate impact on a member’s ability to meet their RE100 target.

In recognition of this, RE100 has elected to set a maximum allowable threshold of electricity

consumption that may be excluded from the RE100 target coverage.

RE100 member companies:

• Can exclude small loads (small offices, retail outlets, etc.) of up to 100 MWh/year

10

, per market,

from the RE100 target boundary;

• Can claim exclusions

11

up to 500 MWh/year (no more than 100 MWh/year per market); and

• Cannot make any exclusions in markets where it is technically feasible

12

to procure renewable

electricity.

10

The size of the excludable load was determined using modelling of energy consumption for a

small office, commercial building, or retail space as well as loads reported by RE100 members.

11

All claimed exclusions must still be reported to RE100 via the annual reporting process.

12

RE100 does not define ‘technically feasible’ but recommends members consider the list of

countries where I-RECs are issued as an indication of technical feasibility.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA 18

3 Third-party verification of consumption of renewable

electricity

Consumption of renewable electricity must be verified by a third party. If renewable electricity is

being self-generated, it may be necessary for generation of renewable electricity to also be verified.

RE100 is not aware of any global standards for verifying consumption of renewable electricity.

However, because the RE100 technical criteria are, in part, based on greenhouse gas accounting

guidance, RE100 considers a GHG auditor’s report that verifies scope 1 and market-based

scope 2 emissions to act as a proxy for a verification of consumption of renewable

electricity. This is because the instruments and evidence used to prepare a GHG inventory are,

according to the RE100 technical criteria, the same instruments and evidence that are used to

make credible claims to use of renewable electricity.

Appendix G discusses how the RE100 technical criteria link to the GHG Protocol Corporate

Standard in more detail. In particular, links with the Scope 2 Quality Criteria are discussed, along

with areas where the RE100 technical criteria deviate from GHG Protocol guidance (i.e., where

RE100’s recognized claims to use of renewable electricity and market-based scope 2 emissions

claims do not align).

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 19

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES

Date of publication: 12 December 2022

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 20

VERSION CONTROL

Version

Revision date

Revision summary

1.0

October 2022

New release to the 2022 technical criteria update presenting clearer

guidance

1.1

12 December 2022

Correction in Appendix B to remove Ireland from the list of

countries in an international single market for renewable electricity

in Europe

New appendix added to clarify guidance around operational

commencement dates eligible for grandfathering

Clarification added in Appendix C around biomass re-powering

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 21

Appendix A: Credible claims to use of

renewable electricity

A claim to use of renewable electricity must be unique and exclusive. Corporate

buyers must be able to demonstrate that they have such claims. This means

securing property rights to renewable electricity attributes. Energy attribute

certificates are recommended as the best method for tracking and establishing

ownership of energy attributes. However, it is possible for a contract alone to

perform the same tracking function as EACs and ensure no other entity may

claim use of the same renewable electricity.

The following six principles more completely define the features of a credible

claim to use of renewable electricity:

• Credible generation data;

• Attribute aggregation;

• Exclusive ownership (no double counting) of attributes;

• Exclusive claims (no double claiming) on attributes;

• Geographic market limitations of claims

1

; and

• Vintage limitations of claims. The period of generation used to claim use of renewable electricity

must be reasonably close in time to the period over which a claim to use of renewable electricity

is made. RE100 does not define ‘reasonably close’.

These points are expanded on below and are also addressed in RE100’s credible claims paper

2

,

which exists as a standalone reference document.

1 Credible generation data

Accurate generation data is critical as the basis for any renewable electricity usage claim. Static

data (e.g., fuel type, location, date of first operation, etc.) should be third-party verified, a common

practice of attribute tracking systems. Dynamic data (quantity of generation) is best when metered

using a “revenue-grade meter” and independently used as the basis for determining the quantity of

attributes and certificate issuance.

Companies should be cautious of making claims where static data cannot be verified by third

parties and/or generation data is not metered.

2 Attribute aggregation

A renewable electricity usage claim is not supported by any individual attribute, but rather by all

attributes that define the generation being claimed. Therefore, making a credible renewable

electricity usage claim requires ownership of all environmental and social attributes associated with

the generation that can be owned, and that none of these attributes have been sold off, transferred,

or claimed elsewhere.

1

See Appendix B for RE100’s precise market boundary definitions

2

https://www.there100.org/technical-guidance

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 22

The conditions of attribute aggregation vary by country and legal/regulatory framework for the

electricity sector. Where a single multi-attribute instrument, such as a U.S. REC exists, assurance

of all relevant attribute aggregation is simplified. If separate instruments have already been created

for different attributes of power generation (e.g., carbon attributes), attribute aggregation can be

achieved by bringing these instruments together – by demonstrating ownership and retirement of all

instruments that make up a renewable electricity usage claim. Where there is not an existing

market for renewable electricity, or where electricity is not typically differentiated, attribute

aggregation may require engagement with local electricity suppliers. Companies should also take

account of the in-country policy context of the generation (existing practices, policies, and legal

frameworks that determine how electricity and renewable electricity is or can be transacted in

different markets).

Where certain attributes (e.g. GHG emissions), cannot be owned or are equivalent to zero due to

policy (e.g. the effect of a GHG cap-and-trade program on the avoided grid emissions attribute),

and where attributes are not sold off separately, a renewable electricity usage claim may

nevertheless be possible, provided that the renewable electricity purchaser owns all other

generation attributes and that the remaining owned attributes are sufficient to define use of the

resource according to market development, consumer expectation, and stakeholder feedback.

Companies should disclose any attributes that are not included in the instrument or transaction. In

addition, different standards and certifications (e.g., Green-e) may have different or additional

requirements for a “fully aggregated” instrument or group of instruments. Companies should also

abide by any local laws and regulations pertaining to claims (e.g., the U.S. Federal Trade

Commission’s “Green Guides” in the U.S.).

3 Exclusive ownership

Exclusive ownership of renewable attributes consists of legal enforceability, tracking (exclusive

issuance, trading, and retirement), and exclusive sales and delivery.

3.1 Property rights

Legally enforceable contractual instruments must include “property rights” to environmental and

renewable attributes of generation – that is, there must be a legally enforceable contract in place to

back the exchange of attributes as property rights. Legal enforceability does not necessarily require

governmental programs or legislation to create or recognize a market or energy attribute certificate,

only that the mechanism for definition and conveyance/transfer of the attributes (e.g., contract,

energy attribute certificate in a tracking system, etc.) is legally enforceable.

3.2 Tracking

Claims must be substantiated by attributes that have been reliably tracked from a generator to a

consumer. Where attributes are transacted without energy attribute certificates, the transfer of

attributes must be clearly articulated in a legally enforceable contract or series of contracts that link

the generator to the end user, and claims must be based on the permanent end-use ownership or

final use of those attributes, which also must be specified in a contract. Where energy attribute

certificates are used, the certificates must be reliably tracked. This, again, can be done using

contracts. However, the most sophisticated mechanism for tracking energy attribute certificates is

an electronic attribute “tracking system”, in which certificates are electronically serialized and

issued to generators with accounts on the system, tracked between account holders in the system

where they are traded, and ultimately permanently retired or cancelled electronically by the entity

making the claim or on behalf of an end-user making a claim. Attribute tracking systems provide

exclusive issuance, trading, and retirement of attributes to markets for renewable electricity to

support credible claims. Where tracking systems exist, transactions outside of the tracking system

are usually limited to special cases (e.g., where participation in the tracking system is too costly for

very small generation units).

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 23

While tracking systems have developed independently of each other in different jurisdictions around

the globe, there are a few elements that all credible tracking systems have in common. These

include:

• Standardized certificate information: Tracking systems issue certificates in MWh, and include

the same basic information on each certificate:

• Resource/fuel Type (e.g., wind, solar, etc.)

• Serial ID

• Generator ID

• Generator Name

• Generator Location

• Vintage (date of generation)

• Issuance Date

• Certificates are issued for all renewable electricity generated by registered generators:

Certificates are issued to the renewable electricity generator. Some tracking systems require

that certificates be issued for all production that is put onto the grid by registered generators. In

others, such as those in Europe, registered generators have the right to request certificates

issuance for selected production, in which case the attributes associated with production that is

not issued certificates are allocated to the residual mix. In both cases, no energy attribute

certificates from registered generators should be traded outside of the tracking system, in order

to avoid potential double counting.

• Defined geographical footprint: To prevent double registration and issuance of certificates,

tracking systems must be clear on the geographic boundaries within which generators have

access to the tracking system, and ensure, through cooperation with other tracking systems,

that generation facilities register in only one tracking system for certificate issuance.

• Independence and transparency: Independence and transparency of tracking systems help to

maintain the integrity of the attribute market. Best practices include:

• The tracking system operator does not act as a market player trading, selling or redeeming

certificates;

• Tracking systems should have transparent and non-discriminatory issuance criteria and

operating rules;

• Tracking system operators should follow defined procedures to identify and prevent conflicts

of interest;

• The tracking system should provide access to regulators and system auditors and allow for

independent consumer claim verifications. To the extent possible, full disclosure of unit

attributes and status should be made public;

• Frequent independent third-party audit of the tracking system should be conducted by a

credible and competent organization, verifying the factual static and dynamic data contained

within the tracking system, and preferably made public;

• The system should be open and accessible to new participants.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 24

4 Exclusive claims

To the extent that tracking systems prevent double issuance and other forms of double counting,

tracking systems alone will not necessarily ensure exclusive claims, i.e., that there are no other

claims being made on either the attributes (including emissions) or electricity as renewable. Where

energy attribute certificates can be sold separately from electricity, the electricity buyer does not

have an exclusive renewable electricity use claim unless they own and retire the certificates, and

likewise the certificate buyer does not have an exclusive usage claim where the electricity is also

being claimed/reported as renewable or individual attributes are being claimed/transacted in

another way. This requires that all renewable electricity instruments or instruments representing

individual generation attributes (e.g., carbon offsets issued for renewable energy generation) have

been retired by or on behalf of the same entity and that there are no other usage claims being

made on the generation or attributes, for example, by the electricity supplier to meet a renewable

electricity delivery target or in marketing that renewable electricity is being delivered to customers.

5 Geographic market boundaries

Attributes (and certificates) must be sourced and purchased from within the same defined

geographic region that constitutes a “market” for the purpose of transacting and claiming attributes.

Ideally this “market boundary” would be clearly defined, but in general it refers to an area in which

the laws and regulatory framework governing the electricity sector are sufficiently consistent

between the areas of production and consumption. As such, transactions that are both international

and intercontinental are not usually appropriate unless there is physical interconnection (indicating

a level of system-wide coordination between countries) and ideally if these countries’ utilities or

energy suppliers recognize each other’s instruments. Within a single country or multiple countries in

a common regulatory framework (e.g., U.S. and E.U. respectively), there may be multiple grid

distribution regions where electricity is physically delivered. Because of the regulatory consistency,

the geographic market for attributes is not necessarily constrained to the area in which it is possible

to physically deliver electricity within the grid. There are advantages to larger market boundaries

that allow consumers to source renewable electricity where it may be less expensive to create,

while other programs or companies may prioritize sourcing from the same grid region as their

consumption in order to support more local jobs or economic development.

Appendix B contains RE100’s definitions of market boundaries its members must observe.

6 Vintage limitations

To make a credible renewable electricity claim, the vintage of the attributes (and certificates) – that

is, when the generation occurred – must be reasonably close to the reporting year of the electricity

consumption to which it is applied. There is no official consensus on what is “reasonable” in this

case, and it may vary between markets. Companies can refer to certification standards, claim

verification and recognition programs, and/or GHG inventory reporting systems to ensure that the

vintage of generation does not occur too far in advance or after consumption. This will also depend

in part on the technical requirements of the tracking system and the market in which the consumer

is active. Certain certification programs may enforce their own criteria for what is considered

“reasonable”, such as Green-e’s requirement of a 21-month vintage eligibility window for certified

sales of renewable electricity in a given year.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 25

Appendix B: Market boundaries

1 What are markets for renewable electricity?

Claims to use of renewable electricity must be based on generation occurring in

the same market for renewable electricity that use is claimed in.

A market for renewable electricity refers to an area in which:

• The laws and regulatory framework governing the electricity sector are

consistent between the areas of production and consumption;

• Electricity grids are substantially interconnected, indicating a level of system-

wide coordination; and

• Utilities/suppliers recognize each other’s energy attributes and account for

them in their trade of energy and energy attributes.

2 Markets for renewable electricity recognized by RE100

Except for the single markets described in the next section, individual countries

are distinct markets for renewable electricity.

3 International single markets for renewable electricity

recognized by RE100

3.1 The single market between the United States and Canada

The United States and Canada are considered to form a single market for renewable electricity.

3.2 The single market in Europe

Countries in Europe which meet all the following conditions are considered to form a single market

for renewable electricity:

• The country is in the EU single market;

• The country is a member of the Association of Issuing Bodies (AIB) – issuing European Energy

Certificate System (EECS) Guarantees of Origin; and

• The country has a grid connection to another country meeting the first two rules.

Exceptions have been made for countries or areas which have little domestic energy production

and import much of their electricity (including renewable electricity attributes) from bordering

countries which meet the above rules. The exempted countries or areas include the Channel

Islands, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City. In these countries or areas,

corporate buyers must procure renewable electricity supported by EECS Guarantees of Origin and

cancel them ex-domain

3

.

3

https://www.aib-net.org/facts/market-information/statistics/ex-domain-cancellations

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 26

The list of countries or areas which currently meet these rules is:

• Austria

• Belgium

• Croatia

• Czech Republic

• Denmark

• Estonia

• Finland

• France

• Germany

• Greece

• Hungary

• Italy

• Latvia

• Lithuania

• Luxembourg

• Netherlands

• Norway

• Portugal

• Slovakia

• Slovenia

• Spain

• Sweden

• Switzerland

• The Channel Islands

4

• Andorra

4

• Liechtenstein

4

• Monaco

4

• San Marino

4

• Vatican City

4

The following countries listed in RE100’s note on market boundaries from 27 May 2019 are

now individual markets for renewable electricity:

Country

Reason for exclusion

• Bulgaria

Bulgaria is not an AIB member

• Cyprus

Cyprus is not grid-connected to the single market for

renewable electricity in Europe recognized by RE100

• Ireland

Ireland is not grid-connected to the single market for

renewable electricity in Europe recognized by RE100

• Malta

Malta is not an AIB member

• Poland

Poland is not an AIB member

• Romania

Romania is not an AIB member

• Serbia

Serbia is not in the EU single market

• The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is not in the EU single market and is

not an AIB member

4

These countries or areas are included in RE100’s view of the single market for renewable

electricity in Europe as exemptions because they have little domestic energy production and import

much of their energy (including renewable electricity attributes) from bordering countries which

meet the rules in Appendix B: 3.2.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 27

3.2.1 Entry into force

Contracts with operational commencement dates

5

before 1 January 2024 may observe the

definitions of market boundaries adopted by RE100 in its note on market boundaries published 27

May 2019 (which includes the countries excluded above) or by CDP in its scope 2 technical note

(version: 3 April 2020) (which states that countries which are AIB members form a single market for

renewable electricity). All contracts with operational commencement dates starting 1 January 2024

and later must observe the updated market boundary definition.

Each RE100 member will be assessed against the updated market boundary definition when they

submit their first disclosures to RE100 which cover twelve months starting on or after 1 January

2024. In each disclosure cycle, the most common reporting period selected by RE100 members is

January to December of the previous year. Therefore, it is expected that members reporting on

their procurement for January to December 2024 in the 2025 disclosure cycle will first have their

adherence to the update market boundary definition studied in the 2025 annual disclosure report,

published in January 2026.

5

See Appendix F for definitions of this term in the context of bundled or unbundled procurement.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 28

Appendix C: Re-powering of projects

6

RE100 considers projects which have met one of the following conditions in the last fifteen years

7

as re-powered and which corporate buyers may procure renewable electricity from:

1. The facility has been re-powered such that 80 percent of the fair market value of the

project stems from new generation equipment installed as part of the re-powering.

2. Eligible hydropower facility improvements that increase electrical energy output due to

efficiency improvements may include:

• Rewinding of existing turbine generator(s)

• Replacement with new turbine generator(s)

• New turbine generator additions to an existing impoundment

Improvements may not as a consequence increase the water storage capacity or the head

of an existing water impoundment, or otherwise change the run of the river flow of the

resource. Qualifying “new” incremental hydropower output will be credited using the

following quantification and accounting criteria. The incremental generating capacity (in

nameplate MW) is divided by the total uprated generating capacity (in nameplate MW) and

then multiplied by generation output (in MWh) from the uprated generator. For example, if

a hydroelectric power plant expands generating nameplate capacity from 100 MW to 125

MW and generation output increased to 1,000 MWh, then 200 MWh ((25 MW/125 MW) *

1,000 MWh) would be eligible for use by corporate buyers, regardless of the overall level

of generation of the project during the period. Note that the overall generation from the

uprated hydroelectric power plant may be higher or lower than generation levels that

occurred at the plant prior to the capacity uprate.

To verify the “new” incremental output, RE100 reserves the right to request that corporate

buyers present an independent third-party report demonstrating that the increased annual

output of electrical energy is a result of the “new” incremental improvements.

Improvements that increase electrical energy output due to routine maintenance (i.e.,

output would be increased compared to original design) do not count.

3. A separable improvement to or a complete improvement of an existing operating facility

provides incremental generation that is separately metered from the existing generation at

the facility.

4. The facility has begun co-firing sustainable biomass with non-renewable fuels or has

transitioned to firing 100% sustainable biomass.

6

RE100 re-powering guidance is adapted from the United States Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) Green Power Partnership's (GPP) guidance: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-

01/documents/gpp_partnership_reqs.pdf#page=10

7

‘Fifteen years’ is defined as on or after 1 January of the year fifteen years prior to the claim of use

of renewable electricity. For example, a claim to use of renewable electricity over January-

December 2025 must be based on procurement from projects commissioned or re-powered on or

after 1 January 2010.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 29

Appendix D: Commissioning or re-

powering date limit worked examples

These diagrams illustrate how corporate buyers with otherwise credible claims to use of renewable

electricity may or may not have their claims recognized as progress towards their RE100 targets.

In this example, a corporate buyer has a credible claim to be consuming 10% renewable electricity.

None of this consumption is subject to the requirements in Section 5: 2.2, and so the entire 10%

contributes progress towards the corporate buyer’s RE100 target.

In this example, a corporate buyer has a credible claim to be consuming 50% renewable electricity.

It exempts procurement of renewable electricity amounting to 15% of its total consumption from the

requirements in Section 5: 2.2. It also subjects procurement of renewable electricity amounting to

35% of its total consumption to the requirements. Therefore, the entire 50% contributes progress

towards the corporate buyer’s RE100 target.

In this example, a corporate buyer has a credible claim to be consuming 100% renewable

electricity. It exempts 15% from the requirements in Section 5: 2.2, and subjects the remainder to

the requirements. Therefore, the entire 100% is recognized by the RE100 technical criteria, and the

corporate buyer has met its RE100 target.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 30

In this example, a corporate buyer has a credible claim to be consuming 50% renewable electricity.

It does not subject any of its procurement to the requirements in Section 5: 2.2 (in other words, it

procures from projects commissioned or re-powered more than fifteen years ago through contracts

with operational commencement dates on or after 1 January 2024). Therefore, only 15%

contributes progress towards the corporate buyer’s RE100 target since it is exempt from the

requirements. The remaining 35% is not recognized as progress towards the RE100 target.

In this example, a corporate buyer has a credible claim to be consuming 100% renewable

electricity. It exempts 15% from the requirements in Section 5: 2.2, but only subjects 75% to the

requirements (in other words, it procures the 25% from projects commissioned or re-powered more

than fifteen years ago through contracts with operational commencement dates on or after 1

January 2024). Therefore, the final 10% is not recognized as progress towards the corporate

buyer’s RE100 target.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 31

Appendix E: Select studies in

identifying procurement types

1 Project-specific versus retail supply contracts for

renewable electricity

The following questions aid in identifying whether a given contract with a supplier must be

characterized as ‘retail’ and not as ‘project-specific’.

• Is it known exactly which projects are used in the supply at all times?

If the answer to this question is ‘no’, the supply is not project-specific and must be

characterized as a retail supply of renewable electricity.

• Can the supplier vary the projects used in the supply without the corporate buyer’s consent, or

is the variation of the projects used in the supply not an explicit clause in the supply contract?

If the answer to this question is ‘yes’, the supply is not project-specific and must be

characterized as a retail supply of renewable electricity.

2 EAC arbitrage

2.1 What is EAC arbitrage?

EAC arbitrage describes swapping EACs for other EACs, often for the purpose of reducing

renewable electricity procurement costs

8

. A corporate buyer holding a PPA with a new project may

receive a supply of EACs with a high market value. The corporate buyer may exchange these

EACs for cheaper EACs (from older or less desirable projects). The corporate buyer still off-takes

the market risk from (and therefore supports) the new project and may realize a financial benefit by

trading the EACs from the new project.

2.2 What procurement types must be reported when EAC arbitrage is

happening?

EAC arbitrage takes away the corporate buyer’s ability to claim it has used renewable electricity

with the new generator’s attributes. The corporate buyer can only claim to have used renewable

electricity with the attributes conveyed by the lower-value EACs it has acquired.

The corporate buyer can report procuring attributes from a new generator through a PPA to convey

a potential support claim for new renewable electricity capacity but cannot make use claims with

those attributes. In reporting to RE100, if member companies report arbitraged PPAs as

PPAs, they must note in a comment where they have arbitraged their PPAs with an

unbundled EAC purchase and include details of the replacement EACs. In this way, claims to

have supported renewable electricity generation and to have used renewable electricity generation

are separate and distinct.

Reporting to RE100 has not previously identified where PPAs are arbitraged, or where unbundled

EAC purchases result from arbitraged PPAs. RE100 will consider evolving its reporting

infrastructure in the future to better study EAC arbitrage if the practice is understood to be

associated with a significant amount of corporate procurement of renewable electricity.

8

https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/documents/gpp-rec-arbitrage.pdf

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 32

3 M2L contracts in China

Large energy consumers in China currently procure in mid-to-long-term (M2L) markets from

electricity exchanges

9

. They can procure from specific projects on the exchanges.

Corporate buyers sourcing renewable electricity through M2L contracts are not contracting with

generators themselves. They must report their procurement as project-specific contracts with

electricity suppliers. The procurement must not be reported as a form of power purchase

agreement, because there is no direct contracting with generators.

4 Long term EAC contracts in the Republic of Korea and

Japan

The Republic of Korea and Japan both offer long-term unbundled EAC contracts from new projects.

The contracts may be advertised as financial (virtual) power purchase agreements. However, the

contracts do not involve contract-for-difference mechanisms which allow for the off-take of market

risk by the corporate buyer, and are only for the projects’ unbundled EACs. The extent to which the

corporate buyer off-takes any wholesale electricity price risk from new projects by providing an EAC

revenue stream to the generator is unclear.

In Japan, a feed-in-premium (FIP) is paid to some projects. The level of the premium is dependent

on the average prices of electricity and EACs in the wholesale market. In theory, the premium will

be higher when the average electricity prices and EAC prices at the wholesale market are lower,

and vice versa or zero in case of negative. This might make long-term EAC contracts with high

EAC prices similar in impact to virtual power purchase agreements, without involving contracting-

for-difference mechanisms or direct contracting with generators.

RE100’s view is that these contracts must be reported as unbundled procurement of EACs.

9

https://rmi.org/insight/corporate-green-power-procurement-in-china-progress-analysis-and-

outlook/

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 33

Appendix F: Operational

commencement dates of contracts

eligible for grandfathering

This appendix provides further guidance to companies establishing which contracts meeting the

2021 RE100 technical criteria are eligible for grandfathering once RE100’s definition of a single

market for renewable electricity in Europe changes (see Appendix B), and when RE100 introduces

a fifteen-year commissioning or re-powering date limit for renewable electricity purchases (see

Section Five: 2.2).

Contracts with operational commencement dates before 1 January 2024 are eligible for

grandfathering.

For the avoidance of doubt, the term operational commencement date has no relation to the signing

date of a contract. Instead, RE100 is linking the term to the claims to use of renewable electricity

the contract is used to make.

1 Bundled procurement

For bundled procurement contracts (meaning all physical PPAs – procurement type 2.1 – and all

contracts with suppliers – procurement types 3.1 and 3.2), the operational commencement date is

defined as the date of first physical supply of electricity.

In other words, for a bundled procurement contract to be eligible for grandfathering, it must be used

to make claims to use of renewable electricity for consumption periods before 1 January 2024.

2 Unbundled procurement

For unbundled procurement contracts (meaning all financial/virtual PPAs – procurement type 2.2 –

and all contracts for unbundled EACs – procurement type 4), the operational commencement date

is defined as the date of the first physical supply of electricity the contract is used to decarbonize.

In other words, for an unbundled procurement contract to be eligible for grandfathering, it must be

used to make claims to use of renewable electricity for consumption periods before 1 January

2024.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 34

Appendix G: Links with the GHG

Protocol Corporate Standard

1 The RE100 technical criteria and the Scope 2 Quality

Criteria

The Scope 2 Quality Criteria define requirements for market-based emissions claims. Broad

comparisons can be drawn with the RE100 technical criteria.

Requirements for a credible claim to use of

renewable electricity

Requirements for a market-based scope 2

emissions claim

Ensuring accurate generation and attribute information

• Credible generation data

• Attribute aggregation

• Convey GHG emission rate

No double-counting of generation attributes or attributes between instruments

• Exclusive ownership (no double-counting)

• Convey GHG emission rate

• Be the only instrument that conveys that

GHG emissions rate

• Tracked, redeemed, cancelled by or on

behalf of the reporting entity

No double-claiming between users

• Exclusive claims (no double-claiming)

• Requirement to use the residual mix or

document its absence

• Utility-specific requirements

• Direct purchasing requirements

Matching generation to usage geographically

• Geographic market boundary limitations

• Market boundary limitations

Matching generation to usage temporally

• Vintage limitations

• Vintage limitations

This table is also found in the RE100 credible claims paper.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 35

2 Where do the RE100 technical criteria deviate from the

GHG Protocol Corporate Standard?

The RE100 technical criteria deviate from established market-based emissions

accounting guidance in some areas, and for different reasons.

2.1 Using market-based instruments to decarbonize scope 1

emissions

RE100 provides guidance for credible use of market-based instruments for claiming scope 1

emissions (i.e., biogas certificates) in the absence of market-based scope 1 accounting guidance

from the GHG Protocol.

RE100 specifically advises that energy attribute certificates issued to renewable electricity

generated and fed into grids are scope 2 instruments which cannot be used to decarbonize scope 1

emissions, or the emissions associated with electricity which is not consumed from the grid.

2.2 Recognizing passive claims to use of renewable electricity where

there is a highly renewable grid and no market

RE100 recognizes passive procurement which conveys no market-based instruments to an

organization on grids which are highly renewable (95% or more) and where no market-based

instruments exist. This is because the initiative does not feel it is necessary to call for members to

drive change in these markets, and recognizes their passive claims there.

It is important to note that while RE100 recognizes claims to use of renewable electricity in

these markets, only location-based emissions claims can be made in them.

RE100 TECHNICAL CRITERIA APPENDICES 36

Appendix H: RE100 Technical Advisory