Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford

FEBRUARY 2018

THE TRAVELERS

American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq

BY

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Cliord

Program on Extremism

February 2018

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

© 2018 by Program on Extremism

Program on Extremism

2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20006

www.extremism.gwu.edu

Contents

Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... v

A Note from the Director ........................................................................................vii

Foreword ........................................................................................................................ ix

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1

Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers ........................................................5

Foreign Fighters and Travelers to Transnational Conflicts:

Incentives, Motivations, and Destinations .....................................................................5

American Jihadist Travelers: 1980–2011 ...........................................................................6

How Do American Jihadist Travelers Compare to Other Western Counterparts? ............8

Methodology and Statistics ....................................................................................... 11

Definitions ..........................................................................................................................12

Statistics .............................................................................................................................. 17

Category 1: Pioneers .................................................................................................... 23

Abdullah Ramo Pazara .......................................................................................................23

Ahmad Abousamra ............................................................................................................30

Pioneers: Enduring Relevance for Jihadist Groups .........................................................35

Category 2: Networked Travelers ......................................................................... 39

Clusters ...............................................................................................................................39

Families ...............................................................................................................................46

Friends ................................................................................................................................49

Networked Travelers: Why “Strength in Numbers” Matters ......................................... 52

Category 3: Loners ....................................................................................................... 55

“Mo” ....................................................................................................................................55

Mohamad Jamal Khweis ....................................................................................................62

Loners: Can Virtual Networks Replace Physical Recruitment? .....................................68

Returning American Travelers ..............................................................................71

Recruitment, Returnees, Reintegration: Challenges

Facing the U.S. Regarding Jihadist Travelers ..............................................................71

Abdirahman Sheik Mohamud ...........................................................................................73

Criminal Justice Approaches to Returning Travelers ..................................................... 75

Addressing the Threat of American Jihadist Travelers .............................. 79

Conclusion...................................................................................................................... 85

Notes ................................................................................................................................. 87

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | v

Acknowledgements

T

his report was made possible by the dedicated and tireless work of the Program on Extremism’s staff. The au-

thors wish to thank the Program’s Director Dr. Lorenzo Vidino, as well as research fellows Audrey Alexander,

Katerina Papatheodorou, and Helen Powell for their invaluable insight and significant contributions to the meth-

odology and construction of this report. Several of the Program’s research assistants, including Silvia Sclafani,

Tanner Wrape, Sarah Metz, Grant Smith, Gianluca Nigro, and Aaron Meyer, assisted in editing and verifying the

final product. The authors also thank Larisa Baste for designing this report.

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the George

Washington University.

The Program on Extremism

The Program on Extremism at the George Washington University provides analysis on issues related to violent

and non-violent extremism. The Program spearheads innovative and thoughtful academic inquiry, producing

empirical work that strengthens extremism research as a distinct field of study. The Program aims to develop

pragmatic policy solutions that resonate with policymakers, civic leaders, and the general public.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | vii

A Note from the Director

Since its foundation, the Program on Extremism has made analysis of all aspects of the Syria and Iraq-related jihad-

ist mobilization in the United States one of its cornerstones. In 2015, it released its flagship report, ISIS in America:

From Retweets to Raqqa, which provided the foundation for various congressional hearings and is currently used as

a training text by law enforcement and intelligence agencies throughout the country. The Program then released

several groundbreaking studies: Cruel Intentions: Female Jihadists in America, a seminal study on the radicalization

of women; Fear Thy Neighbor: Radicalization and Jihadist Attacks in the West, which analyzed all jihadist attacks in the

West since the declaration of the Caliphate; and Digital Decay: Tracing Change Over Time Among English-Language

Islamic State Sympathizers on Twitter, part of the Program’s larger effort to monitor various jihadist activities online.

The Program also regularly releases two related products: the Extremism Tracker, our monthly update which details

terrorism-related activities and court proceedings in the United States, and the Telegram Tracker, a quarterly analysis

documenting our researchers’ data collection of pro-Islamic State channels with English-language content on the

messaging application Telegram.

Our latest report, The Travelers: American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq, provides a uniquely comprehensive analysis of

the phenomenon of American foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Drawing on thousands of pages of documents and

dozens of exclusive-access interviews (including with returning foreign fighters), the report describes a phenome-

non that is bound to have enormous implications on the security environment for the coming years. As the nature

of the threat evolves, the Program on Extremism is committed to continuing its effort to produce evidence-based

and non-partisan analysis to support sound policymaking and public debate.

Dr. Lorenzo ViDino

Director, Program on Extremism

February 2018

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | ix

Foreword

T

he declaration of a caliphate by Abu Bakr al-

Baghdadi in 2014 generated excitement among

Salafi-jihadist Muslims worldwide. Here, at last, was the

restoration of the long-awaited Islamic State that would

go on to conquer the world for Islam. Coming at the

crest of victories by the forces of the Islamic State of Iraq

and al-Sham (ISIS), an organization that traced its origins

to the insurgency in Iraq following the American-led

invasion of that country, Baghdadi’s audacious assertion

seemed to carry weight.

The anti-government protests in Syria—one dimen-

sion of the wave of uprisings that swept across North

Africa and the Middle East beginning in 2011—and

the Syrian government’s brutal response, had already

attracted foreign volunteers to the ranks of the rebels.

The Islamic State, as the caliphate was called, attracted

tens of thousands of additional recruits, far more than

the mujahideen who joined the Afghan resistance against

Soviet occupation in the 1980s or those who passed

through al-Qaeda’s training camps in the 1990s.

Some recruits came to the Islamic State as pilgrims,

escaping what they considered to be the oppression of

residing among infidels, to live among like-minded be-

lievers and build the new province of faith. Others came

to fight in the ranks of the Islamic State’s forces, perhaps

to participate in the final battle between Muslims and

unbelievers, prophesized in Sunni eschatology. Still

others came to gain the training and battle experience

that would enable them to assemble new organizations

that would launch new jihadist fronts at home.

The declaration of the Islamic State posed little immedi-

ate threat to U.S. homeland security, although ISIS went

out of its way to provoke revulsion and create enemies

abroad. The reaction in Washington was one of alarm.

One alarmed senator asserted that “we are in the most

dangerous position we ever have been as a nation.”

Another warned that American troops had to be sent to

Syria “before we all get killed here at home.” The public

mostly agreed.

In response to the Islamic State’s atrocities, an American-

led coalition began bombing ISIS targets and assisting

Iraqi and locally recruited ground forces in September

2014. Meanwhile, Syrian government forces and Iranian-

created militias, assisted by Russian air power beginning

in 2015, closed the ring on the Islamic State’s forces in

western Syria.

While guerrillas and terrorists are difficult to destroy,

defending territory in open battle against militarily su-

perior foes is generally a losing proposition. By the end

of 2017, the territorial expression of the Islamic State had

been almost entirely eliminated, although most analysts

believed that the armed struggle would continue.

Many of the foreign fighters died in the defense of cities

and towns held by the Islamic State. They were fervent

and expendable. They were often volunteers for suicide

missions. And they would have no future in an under-

ground contest, especially those from countries outside

of the region. Those not killed fled, some to other jihad-

ist fronts; many returned home.

Some of the returnees, no doubt, were disillusioned

by the brutal experience of life under the bloodthirsty

rule of the Islamic State’s merciless application of its

interpretation of Islamic governance, although some

foreign fighters enthusiastically participated in its bar-

barities. Some were traumatized by the savage warfare

that marked its defeat. Yet some escaped with their

commitment intact, determined to carry on the jihad.

As this book illustrates, the recruiters for future jihads

arise from past jihadist campaigns.

This excellent volume examines the experience of the

American jihadists in Syria and Iraq. It represents an-

other installment in the continuing research carried

out by George Washington University’s Program on

by brian Michael Jenkins

x | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

ForeWord

Extremism, which has already produced a number of

informative reports on various aspects of radicalization.

Far fewer foreign volunteers traveled to the Islamic

State from the United States than from Europe. The

estimated number of foreign volunteers from Europe

ranges from 5,000 to 6,000, most of them from France,

Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom, while U.S.

officials speak of several hundred—an all-in number that

includes those arrested before leaving the United States,

those arrested abroad, and those known to be killed. The

numbers remain a bit murky. Most of the 250 to 300

American jihadist recruits mentioned by authorities have

not been publicly identified, suggesting on-going inves-

tigations, sealed indictments, and some uncertainty.

This study examines 64 of these travelers in greater detail

than any previous study. The thoroughness of the re-

search offers new insights. It is typically not the purpose

of a foreword to summarize a book’s conclusions, but

some of the authors’ observations merit reinforcement.

One is that, consistent with earlier research, there is no

single profile of the American travelers and their mo-

tives vary greatly.

While much is made of the Islamic State’s recruiting

via the Internet and social media, the authors find that

in-person contacts played a major role in recruiting and

facilitating travel from the United States to Syria. It

would be an overstatement to say that there is an orga-

nized jihadist underground in the United States, but this

research shows that there is a patchwork of connections,

some reaching back to the Balkans conflicts of the early

1990s. This connectivity offers domestic intelligence op-

erations with leads to unravel and suggests that a small

number of key individuals play a significant role in any

new mobilization. Ensuring that the connections do not

coalesce into a larger web must be a primary objective of

counterterrorism strategy.

Returning foreign fighters pose only one dimension of a

multilayered threat. Some analysts fear that the Islamic

State’s leadership will seek to launch major terrorist attacks

in the West in revenge for the destruction of the caliphate.

Deprived of its nation-building message, the Islamic State’s

propaganda now focuses on war. U.S.-bound commercial

flights offer another vector of terrorist attack, one that

has engrossed al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Most

jihadist terrorist plots in the United States, however, have

been the schemes of domestic jihadists who did not go

abroad. They are more likely to carry out attacks than are

returning travelers.

The good news is that the destruction of the Islamic State’s

territorial enterprise deprives fervent jihadists of an acces-

sible destination. However, this is also the bad news. The

most determined, most prone to violence, have nowhere

to go. Will the closing of this escape valve presage an in-

crease in homegrown jihadist plots?

The numbers suggest that only a fraction of the volun-

teers who traveled to the Islamic State will return. And

thus far, very few of those returning to Europe or the

United States have been involved in plotting terrorist

attacks after their return. But as demonstrated in the

2014–2016 terrorist campaign in France and Belgium,

the greatest danger comes from a combination of return-

ing foreign fighters and local confederates. The United

States, however, lacks the large, alienated immigrant

diasporas of Europe where returning foreign fighters can

more easily find hideouts and accomplices. It is import-

ant that American attitudes and policies do not create

such conditions.

Arrest, surveillance, and suspicion by other would-be

jihadists who fear that any returning foreign fighters still

at large are likely to be police informants may suffice to

keep the returnees isolated. Imprisonment alone will not

solve the problem. Most homegrown jihadists as well

as those who went abroad were first radicalized in the

United States. Returnees disillusioned by their experi-

ence abroad could be recruited in efforts to discourage

homegrown terrorism and recruitment to new jihadist

fronts abroad.

Brian MichaeL Jenkins

February 2018

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 1

Executive Summary

T

his study reflects the most comprehensive, publicly

available accounting of Americans who traveled to

join jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq since 2011. It iden-

tifies 64 travelers, the largest available sample to date.

These individuals, and their stories, were uncovered

during a multi-year investigation. Authors interviewed

law enforcement officials, prosecutors, and defense

attorneys, and attended relevant court proceedings.

Additionally, they reviewed thousands of pages of legal

documents, filing information requests and federal court

motions to unseal records where necessary. Finally, the

authors conducted several interviews with American

travelers who returned from the territories held by the

Islamic State (IS).

Travel or attempted travel to jihadist-held territory in

Syria and Iraq is one of the most popular forms of mobi-

lization for American jihadist sympathizers. In addition

to successful travelers, at least 50 Americans attempt-

ed to travel but were prevented from doing so by law

enforcement. These cases constitute approximately one-

third of the 153 Americans who have been arrested on

Islamic State–related charges from 2011 to 2017. Cases

of travel or attempted travel to Syria or Iraq have steadily

decreased since 2015.

The study finds that there is no single profile of an

American traveler, although some demographic trends

reflect the broader population of jihadist supporters

in the United States. Travelers tend to be male, with

an average age of 27. They generally affiliated with IS

upon arrival in Syria or Iraq. The three states with the

highest proportional rates of recruitment are Minnesota,

Virginia, and Ohio.

Based on the underlying factors behind their travel,

how they made their journey, and what role they took

in jihadist groups, American travelers can broadly be

classified using the following three categories. Using

case studies, this report contains analyses of each cat-

egory of traveler.

•

Pioneers arrived early in Syria and Iraq and ascended

to some level of leadership in their respective jihad-

ist organizations. They are distinguished from other

travelers due to previous experience with critical

skills relevant to their organization—such as military

training, past participation in jihadist movements,

proficiency in religious doctrine or producing ideo-

logical material, and technical skills (bomb-making,

computer skills, etc.). Due to these abilities, pioneers

attain coveted positions within jihadist groups.

They often use their roles to reach out to individuals

within their network and encourage them to provide

support to jihadist groups. However, only a select few

individuals have the skills and abilities necessary to

become pioneers. Four travelers (6.3%) in the sample

are coded as pioneers, making it the smallest category

in number, but far larger if assessed in terms of their

impact on the jihadist movement.

•

Networked travelers use personal contacts with

like-minded supporters of jihadist groups in the U.S.

to facilitate their travel. In some of these cases, a

group of individuals, usually connected by kinship,

friendship, or community ties, travel together to

Syria or Iraq. Others, while traveling by themselves,

had contact with individuals in the U.S. who support-

ed their journey by providing financial or logistical

support, or with individuals who were involved

in supporting jihadist groups in other ways (e.g.

through committing or planning attacks). These

groups can be as small as two, and in one case, at

least a dozen individuals, all from the same commu-

nity and/or social network. Eighty seven percent of

the travelers for whom information is available had

some form of personal connection to other travelers

or jihadist supporters.

•

Loners are exceptions to the norm regarding the

recognized importance of networks in facilitating

travel. In contrast to networked travelers, loners

travel seemingly without the assistance of anyone

2 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

execUTive sUmmary

whom they know personally. Yet, despite appar-

ently lacking these facilitative links, they manage to

reach Syria and Iraq without being apprehended. To

make up for the lack of personal connections, loners

often turn to the internet, reaching out to virtual

connections who assist them in making the deci-

sion to travel and completing the journey. Six cases

(9.4%) in the sample were coded as loners. Loners’

stories counter common assumptions regarding

jihadist mobilization and travel facilitation. Due to

the complex, individualized factors that drive their

personal decisions, developing responses to loners is

an exceptional challenge.

The U.S. faces differing threats from each category.

Of significant concern to U.S. law enforcement is the

specter of American travelers returning to the U.S. from

Syria and Iraq. American returned travelers may bolster

domestic jihadist networks by sharing expertise, radical-

izing others, or committing attacks.

This study finds that to date, the phenomenon of return-

ing travelers has been limited in the U.S. context. From

the 64 travelers identified by name, 12 returned to the

U.S. Nine of those returnees were arrested and charged

with terrorism-related offenses. The remaining three

have, so far, not faced public criminal charges related

to their participation in jihadist groups in Syria or Iraq.

As of January 1, 2018, no returned travelers from Syria

and Iraq have successfully committed a terrorist attack

in the U.S. following their re-entry. Only one of the

12 returnees identified in this study returned with the

intent to carry out an attack on behalf of a jihadist group

in Syria. This individual was apprehended in the early

planning stages of their plot.

Therefore, the risk of returned travelers being engaged

in terrorist attacks has, to date, been limited. There have

been 22 jihadist attacks from 2011 to 2017; none of them

were committed by a perpetrator who was known to

have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join jihadist groups.

Thus, “homegrown” extremists currently appear to be

more likely to commit domestic jihadist attacks than

returning travelers.

Yet, returning travelers pose other threats. If left unad-

dressed, returnees can augment jihadist networks in the

U.S., provide others with knowledge about how to travel

and conduct attacks, and serve as nodes in future jihadist

recruitment. Throughout the history of American ji-

hadist travelers, several individuals who were formative

to future mobilizations had returned to the U.S. from

fighting with jihadist groups overseas.

To address this threat, the U.S. may consider broadening

its options to counter jihadist travel and respond to the

risk from returnees.

•

The American traveler contingent defies a single

profile, and approaches should account for their

diverse nature. The categories of travelers present-

ed in this study can assist in developing a basis for

classification and review of the threat posed by

individual travelers.

•

The roles of travelers who hold non-combatant roles

in jihadist groups should be considered. Of note are

women travelers, who traditionally assume auxiliary

roles in jihadist groups. They function in logistical

and financial capacities, as well as more communal,

day-to-day operations. The U.S. should also develop

a comprehensive process for returning children, who

cannot be prosecuted and should be re-integrated

into society.

• Unlike many other countries, American laws crim-

inalizing jihadist travel were in place well before the

mobilization to Syria and Iraq. The statutory law offers

law enforcement flexibility and leeway in charging

travelers. However, in some cases, prosecution is

infeasible. At times, it is difficult to garner evidence

about a traveler’s activities in Syria and Iraq that is

admissible in a court of law. As a result, prosecutors

are often forced to charge returned travelers with

lesser offenses. While the average prison sentence

for individuals who attempted (but failed) to travel

to Syria and Iraq is approximately 14 years, the seven

successful travelers that have been convicted from

2011–2017 received an average sentence of ten years

in prison.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 3

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

•

Considering that many convicted American travel-

ers will be released within the next five to ten years,

prison deradicalization programs should be regarded

as a priority. There are no deradicalization or reha-

bilitation programs for jihadist inmates in the U.S.

federal prison system. Without these programs,

incarcerated travelers have few incentives to renege

on their beliefs, and may attempt to build networks

in prison or radicalize other prisoners.

•

Programs designed to prevent future radicalization

also require sustained official attention. Disillusioned

American returnees may have some role to play in

these programs as effective providers of interventions.

If national-level targeted intervention programming

is developed, efforts can be informed by the successes

and failures of local initiatives, as well as similar proj-

ects developed in other countries.

•

Digital communications technologies are useful

tools for facilitating jihadist travel. Yet, regulation

(e.g. censorship, content and account deletion, reg-

ulating or banning privacy-maximizing tools) of

online platforms favored by jihadists may have little

effect on travel facilitation networks. While the

availability of jihadist propaganda has undoubtedly

diminished on open platforms due to content remov-

al, American travelers tend to access such material on

lesser-known online repositories. Travelers also mi-

grated to alternative social media platforms and use

a range of privacy-maximizing services—including

virtual private networks, anonymous browsers, and

encrypted messengers—to access content, communi-

cate with recruiters, and mask their locations.

If the previous mobilizations of American jihadists to

Afghanistan, Bosnia, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, or

elsewhere are any guide, individuals and dynamics from

one mobilization often play outsized roles in future re-

cruitment networks. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the

U.S. government, American civil society organizations,

and scholars of jihadism to use the lessons from the

Syria- and Iraq-related mobilizations to develop pro-

active and comprehensive policies to address American

jihadist travel.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 5

Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers

S

ince the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011, the

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has reported

that 300 Americans attempted to leave or have left the

U.S. with the intention of fighting in Iraq and Syria.

1

While the details of many of these cases remain either

unknown or obscure, this study is among the first to

offer an overview and analysis of America’s jihadist

travelers. Drawing on an array of primary sources, in-

cluding interviews with returnees, court documents, and

the online footprints of known travelers, it sheds light

on why and how they joined jihadist groups, and what

threat they currently pose to the U.S.

After an introductory discussion of the current liter-

ature on the topic, including the history of American

involvement in foreign jihadist conflicts, the study

provides the most comprehensive publicly available sta

-

tistical breakdown of this phenomenon. This approach

helped inform the creation of a new typology of jihadist

travelers: pioneers, networked travelers, and loners.

These sections will also include select in-depth analyses

of some of the more revealing case studies that best

exemplify each category. Next, the report documents

cases of American travelers who returned to the U.S.,

assessing their threat and the current U.S. response. The

study concludes with a set of recommendations for both

government and civil society.

Foreign Fighters and Travelers

to Transnational Conflicts: Incentives,

Motivations, and Destinations

In absolute terms, the current mobilization of foreign

fighters and jihadist travelers to Syria and Iraq outnum-

bers all other mobilizations to jihadist conflicts during

the past 40 years.

2

Estimates of the total number of

foreigners who have traveled to Syria and Iraq broadly

range between 27,000 and 31,000, the majority of whom

originate from North Africa and the Middle East.

3

At its

peak, an estimated 2,000 jihadist travelers were crossing

the Turkish border into Syria weekly; since 2016, this

number has decreased to around 50 crossings due to the

declining territorial holdings of the Islamic State of Iraq

and Syria (IS) and increased border enforcement by the

Turkish government.

4

Foreign Fighters vs. Travelers

David Malet defines the term “foreign fighters” as

“non-citizens of conflict states who join insurgencies

during civil conflicts.”

5

According to this definition, “for-

eign fighters” would comprise a significant percentage of

the individuals in the sample. However, it is worth noting

that this terminology does not account for individuals

who joined the Syrian and Iraqi jihadist insurgencies

with different motives, roles, and backgrounds. Instead,

this study uses the term “travelers” to refer to the U.S.

persons who have traveled to Syria or Iraq since 2011 to

participate in jihadist formations.

The term “foreign fighter” presumes an individual’s mo-

tivations, and their role in the organization in question.

While most of the individuals in the sample left their

homes for Syria and Iraq specifically to participate in

conflict and served in combat roles upon arrival, some

did not. The rise of IS, whose mission was framed not

only in terms of attacks and military campaigns but also

addressed legitimate, religio-political governance, drew

individuals who (albeit misguidedly) traveled to join

the group in the hopes of living peacefully in the new,

self-declared Caliphate while avoiding combat. It is also

important to point to the roles of women in these jihad-

ist organizations; while most groups prohibit women

from combat, they hold active and essential positions

in day-to-day operations and management.

6

Thus, the

term “traveler” more closely encapsulates not only those

who travel to fight in jihadist groups, but also those with

different intentions.

Motivations

Currently, the Syrian conflict has the lion’s share of

the global base of jihadist recruits.

7

Yet, it is a mistake

to assume that all travelers were drawn to Syria for

6 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

inTrodUcTion: american JihadisT Travelers

the same reasons. Many travelers who left for Syria in

the years directly after 2011 did so in reaction to per-

ceived injustices committed by the Syrian regime. Some

were not attracted to a specific jihadist group prior to

traveling, but later made networked connections that

dictated their choice of organization. A number of these

individuals likely went abroad rather than staying home

to plot attacks largely because of the opportunity and

“social desirability” of waging jihad.

8

However, with the

emergence of specific organizations like IS and Jabhat

al-Nusra (JN), an increasing number of travelers had

decided which group to join prior to leaving.

Before 2011, data on travelers were largely incomplete.

The overall number provided small sample sizes unsuit-

able for generalization. Scholars are still at an impasse

in determining the factors that have led to jihadist

travel over the years; however, new data establish some

macro-level trends.

9

The recent Syria and Iraq–based

mobilizations generated a more extensive dataset of ji-

hadist travelers for study. When analyzed, they disprove

some common explanations of why individuals travel

abroad to participate in jihadist organizations.

The overarching assessment of scholars of jihadist

radicalization and mobilization is that sweeping, unidi-

mensional theories of why individuals fight overseas lack

methodological rigor, are driven by political or personal

biases, or both.

10

The most comprehensive studies utilize

a multitude of methods from across social and political

sciences to explain what is, in essence, a highly person-

alized and individual decision. They also admit that a

theory which is useful in one test case may not be helpful

in another.

Some theories of mobilization focus on socio-economic

barriers (unemployment, poverty, “marginalization”/

lack of societal integration) as motivators for individuals

to fight abroad. At face value, some of these factors may

appear to be reasonable or logical explanations for mo-

bilization. At best, however, studies have demonstrated a

weak correlation between economic variables and jihadist

travel.

11

On one hand, some studies find that a substantial

number of individual jihadist travelers from a specific

country had financial problems, were unemployed, or

living on social welfare.

12

However, when applied to

the American context, these trends appear to be less

illustrative. The sample of American IS supporters cut

across economic boundaries, and American Muslims

as a population tend to experience greater levels of

economic success and integration than their counter-

parts in other Western countries.

13

Simultaneously, a

near-consensus of studies also show that there is no

correlation between a country’s economic performance

indicators and the number of travelers in Syria and Iraq

from that country.

14

Another single-factor theory that merits discussion is

the argument that jihadist traveler mobilization stems

from increased access to digital communications tech-

nology, and the strategies that jihadist organizations use

to recruit and mobilize followers online. Undeniably,

the internet has become foundational to how jihad-

ist organizations recruit, network, and communicate

within their ranks; a number of cases within this dataset

reflect these dynamics. That notwithstanding, there are

very few cases wherein a traveler radicalized, decided to

travel, traveled, and reached their destination without

any offline connections.

15

At some point in this process,

travelers must make the jump from the online world into

real-life interactions.

16

American Jihadist Travelers: 1980–2011

Some estimates place the number of U.S. persons in-

volved in overseas jihadist movements from 1980 to 2011

at more than a thousand.

17

During this 30-year period,

the destinations chosen by Americans fighting overseas

varied geographically and temporally. The conflicts and

areas that drew in the most American jihadist travelers

included the conflict in Afghanistan during the 1980s,

the 1990s civil war in Bosnia, and the mid-2000s cam-

paigns waged by al-Shabaab in Somalia and al-Qaeda and

Taliban affiliates on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

18

There is additional evidence of American jihadist par-

ticipation in other conflicts, including in Yemen and the

North Caucasus.

The major networks of jihadist traveler recruitment in

the U.S. mainly began during the Soviet occupation of

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 7

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

Afghanistan.

19

Several individuals linked to the initial

iteration of al-Qaeda, including the “father of jihad”

Abdullah Azzam, were active in recruiting Americans

to join the mujahideen (jihadist fighters) fighting against

the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

20

Under the front of

charity or relief organizations, these recruiters set up

shop in several American cities and drew from the base

of individuals who attended their lectures and speeches

to recruit foreign fighters.

21

Sources vary on how many

Americans were active in Afghanistan in the 1980s. J.M.

Berger has identified at least thirty cases of Americans

participating in the Afghan jihad, some of whom contin-

ued onwards to other conflicts, and others who returned

to the U.S.

22

Some individuals from this first

mobilization in Afghanistan simply

moved onwards to the next set of

jihadist conflicts, in particular to the

civil war in 1990s Bosnia. One ex-

ample is Christopher Paul, a Muslim

convert from the Columbus, Ohio,

area who participated in al-Qaeda

training camps in Afghanistan during

the late 1980s and early 1990s, and

later joined the foreign fighter bri-

gades active on the Bosnian Muslim

side of the civil war.

23

At the conclusion of the conflict

in Bosnia, Paul traveled through Europe and made a

number of connections with al-Qaeda cells. He subse-

quently returned to the U.S. and attempted to recruit

his own network of jihadist supporters in Columbus.

24

After almost two decades of participating in jihadist

movements in numerous countries, Paul was arrested

by the FBI in 2007.

25

A 2014 RAND study identified 124 Americans who

traveled or attempted to travel overseas to join jihadist

groups after September 11, 2001.

26

Almost one-third

were arrested before reaching their destinations, and

approximately 20% were reportedly killed overseas.

27

The most popular destination for jihadist travelers was

Pakistan (37 cases), followed closely by Somalia (34

cases); al-Qaeda and al-Shabaab were the two most pop-

ular jihadist groups.

28

Pakistan became the preferred destination for jihadist

travelers seeking to join al-Qaeda’s main corpus of fight-

ers in South Asia. The 2001 U.S. military engagement

in Afghanistan forced al-Qaeda to relocate its infra-

structure to Pakistan.

29

From 2007 onward, Somalia

outpaced Pakistan as the primary destination for trav

-

elers.

30

One other conflict zone of note is Yemen, where

two powerhouses of the American jihadist scene made

their mark on anglophone jihadist recruitment net-

works. The New Mexico–born cleric Anwar al Awlaki,

already well-known for preaching jihad on both sides

of the Atlantic, traveled to Yemen in 2004 and joined

al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

31

Together

with another American, Samir Khan, the two created

the AQAP magazine Inspire, which became formative

in radicalizing future decades of

English-speaking jihadists.

32

Three phenomena from these

pre-Syria mobilizations of American

travelers may help shed light on the

dynamics characterizing the current

wave of travelers. First, as is the

case now, a significant proportion

of jihadist travelers to Afghanistan,

Bosnia, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen

appeared to have done so in connec-

tion with networks—close communities, friendship and

acquaintance groups, and families.

33

Cases of attacks in

the U.S. perpetrated by individuals who returned from

jihad overseas are very rare. The RAND study found that

90% of the jihadists in the survey were either arrested in

the U.S. prior to traveling, killed or arrested overseas, or

arrested directly after returning home.

34

In their sample,

9 of the 124 travelers returned to the U.S. and planned

attacks—none of these plots came to fruition or resulted

in any deaths.

35

These two factors point to the third and likely most

important phenomenon: the individuals who have

been most influential in recruiting American jihad-

ists are those who act as “links” between the various

mobilizations. These are the individuals who, upon

conclusion or dispersal of a conflict, move onwards

to the next battlefield and form connections between

“Some estimates

place the number

of U.S. persons

involved in overseas

jihadist movements

from 1980 to 2011

at more than a

thousand.”

8 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

inTrodUcTion: american JihadisT Travelers

their old networks and new networks. Ideologues

like AQAP cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, whose work on

“lone actor jihad” survived his death, have their works

re-purposed to recruit individuals during later mobi-

lizations. Operatives like Christopher Paul use skills

that they learn in their previous experience with jihad

to facilitate plots worldwide. Recently, “virtual entre-

preneurs” like the Somalia-based al-Shabaab member

Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan (aka Mujahid Miski),

use the internet to actively facilitate the travel of U.S.

persons to multiple battlefields across the globe. These

transitionary figures often act as nodes for recruitment

of their fellow Americans back home either for the

purpose of conducting attacks or traveling to the latest

jihadist hotspot.

How Do American Jihadist Travelers

Compare to Other Western Counterparts?

American and European jihadist travelers tend to differ

in numbers, demographic profiles, and means of re-

cruitment. The American contingent is far smaller than

those of most European countries. It is estimated, for

example, that more than 900 jihadist travelers have left

from France, 750 each from Germany and the UK, and

over 500 from Belgium.

36

Although the proportion of

travelers to total population and Muslim population are

different, in sheer numbers the mobilization from the

U.S. more closely compares to the phenomena in coun-

tries like Spain (around 200) and the Netherlands (220).

37

Three major factors explain the smaller American mo-

bilization. Geographic distance between the U.S. and

the Syrian/Iraqi battlefields plays a role. The increased

length of the journey that would-be American travelers

must take to reach Syria allows opportunities for law

enforcement to interdict jihadists.

Secondly, the U.S. legal system has multiple tools at its

disposal to prosecute jihadist travelers. At the outset

of the Syria-related mobilization of jihadist travelers,

many European countries did not have laws criminal-

izing travel. In the U.S., traveling to a foreign country

in pursuit of joining a designated foreign terrorist

organization (FTO) has constituted a federal criminal

offense under the material support statute (18 USC

§ 2339A and 2339B) since its adoption in the mid-

1990s.

38

Historically, this law has been interpreted

broadly (e.g., providing one’s self, in the form of travel,

to a designated FTO is classified as material support).

Prosecutors are given substantial leeway, and those

tried under the statute are almost always convicted.

39

Currently, IS-related material support prosecutions

in the U.S. have a 100% conviction rate.

40

Moreover,

those convicted of material support in the U.S. can

face prison sentences of up to 20 years and a lifetime

of post-release supervision. In Europe, a much smaller

percentage of travelers have been prosecuted. Even in

cases where prosecution is successful, convicted trav-

elers face shorter sentences.

41

Finally, wide-reaching jihadist recruitment networks

were far more established in the European context

prior to the conflicts in Syria and Iraq. Militant Salafist

groups, including al-Muhajiroun in the UK, Sharia4

in several European countries, Profetens Ummah (PU)

in Norway, and Millatu Ibrahim in Germany, were all

active in several European cities before 2011. When the

Syrian conflict began, these groups began to mobilize

their supporters to engage in networked travel to the

Middle Eastern theater to participate in jihadist move-

ments.

42

In assessing the stories of European jihadist

travelers from these countries, many were active mem-

bers of these groups prior to leaving. Similar initiatives

existed in the U.S. (for example, Revolution Muslim),

but they were not organized on the same scale as their

European counterparts.

43

The impact of geographic distance, the legal landscape,

and organized Salafi-jihadist networks before the Syrian

conflict not only manifested in the increased numbers

of travelers from Europe, but also affected a difference

in how and from where travelers were recruited. In the

American context, a significant percentage of individuals

travel in small numbers—at most, two or three from a

specific city or neighborhood. Some do so by themselves

without any network or connections prior to their de-

parture. In contrast, many of the major hubs of European

recruitment, including cities, towns, and even small

neighborhoods, are home to dozens of foreign fighters

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 9

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

apiece.

44

In the U.S, particular areas may exhibit similar

clustering (Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, may be

a rudimentary case), but none exist on the scale of their

European counterparts.

This relative lack of face-to-face contact with jihadist

recruitment networks helps explain both the lower num-

bers of American IS travelers and the role of the internet

in inducing Americans to travel. Case studies of many of

the individuals included in this dataset reveal that in lieu

of personal ties to fellow jihadist supporters in the U.S.,

travelers used online platforms to make connections

throughout the world.

45

There are a few notable caveats.

First, this is not to suggest that online recruitment was

the only factor motivating American jihadists. In many

cases, however, access to online networks exacerbated

the impact of personal circumstances and connections.

The upper echelon of American travelers—those who

traveled to Syria, established themselves in the opera-

tions of jihadist groups, and then turned homeward to

recruit other Americans—usually relied on previous

personal networks to facilitate their travel. While these

individuals used the internet to communicate with

friends, family, and potential supporters in the U.S.,

there is little evidence to suggest that online propaganda

played as large of a role as it did in motivating loners.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 11

Methodology and Statistics

T

he authors collated the sample of 64 American ji-

hadist travelers during a multi-year investigation,

utilizing a range of sources. These include thousands

of pages of documents from U.S. District Court cases.

Some of the court filings presented in this study were

unsealed following legal and open-access requests made

by the Program on Extremism. The Program submit-

ted more than a dozen Freedom of Information Act

(FOIA) requests and six appeals to initial rejections of

those requests. In addition to the FOIA process, the

Program filed several motions in federal courts across

the country to enjoin the release of records. As a result,

the authors obtained hundreds of pages of previously

sealed documents.

1

This report also presents data gathered from social

media accounts that are confirmed to belong to

American travelers. These accounts were drawn from

the Program on Extremism’s database of over 1,000,000

Tweets, from over 3,000 English-language pro-IS

Twitter accounts.

Finally, the authors conducted in-person interviews

with U.S. prosecutors, national security officials, de-

fense attorneys, returned American travelers, and their

families. These discussions provide insight into the radi-

calization and recruitment processes, travel patterns, and

networked connections of American travelers.

As some of the travelers interviewed were defendants in

criminal proceedings, authors took multiple safeguards

in presenting information from those interviews in

this report. Where necessary, the names of interview

subjects were redacted or changed to protect anonymity

and privacy.

The principal researchers are well-aware of the signif-

icant methodological issues presented by interviewing

returned jihadist travelers. In presenting interview data,

this report relies on previous studies where researchers

interviewed travelers to understand the motivations and

factors behind their travel.

2

At the same time, it attempts to avoid the methodolog-

ical missteps that many studies and media reports have

made in transmitting data drawn from interviews with

current or former violent extremists.

3

In the areas of this study that present material gleaned

from interviews with travelers, the authors attempt

to introduce but heavily qualify statements made by

the traveler, explain the complexities in first-person

accounts of radicalization and mobilization, and limit

potential inferences. Each interview shows that the

decision to travel is often opaque, multivariate, and

non-generalizable.

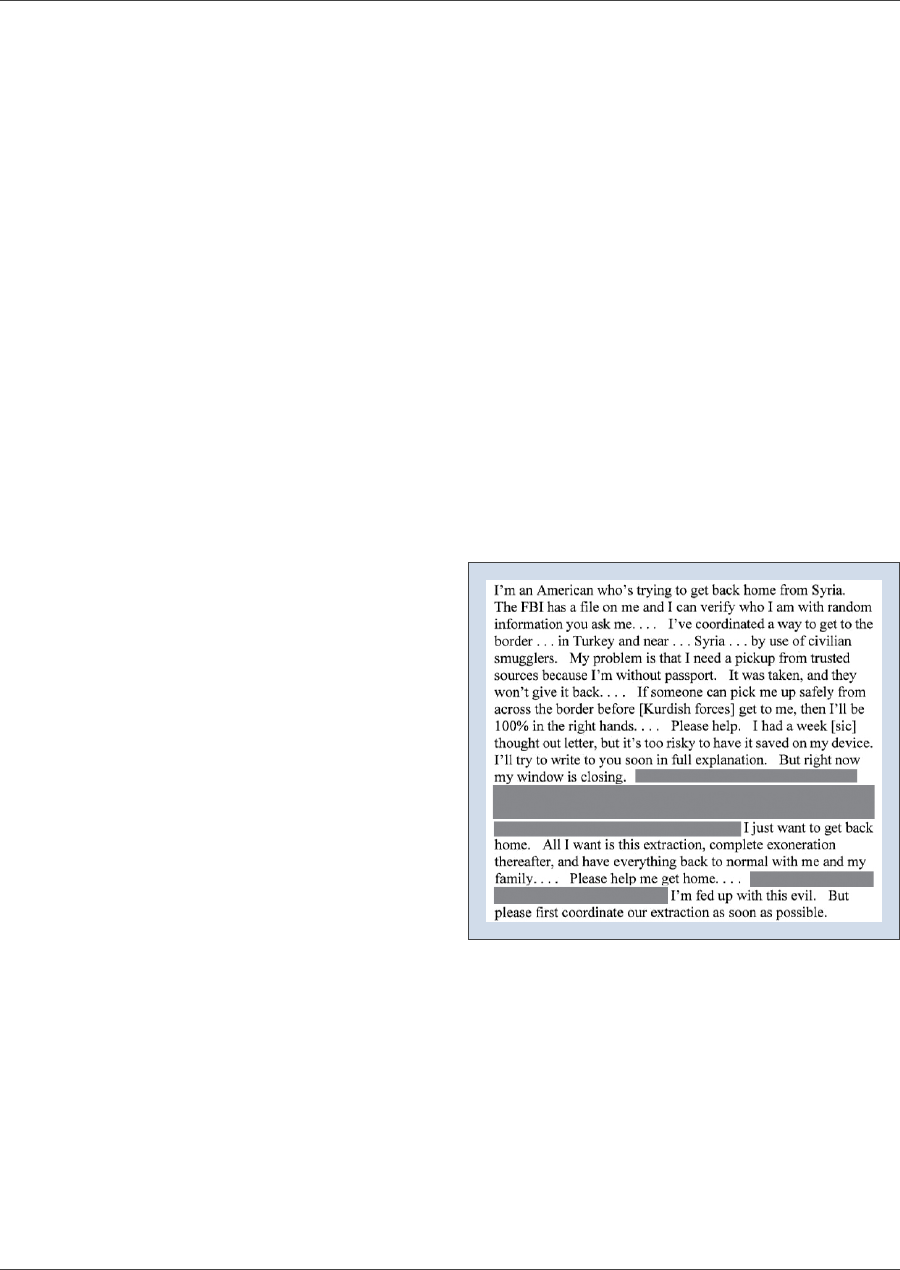

Some interviewed travelers returned to the U.S., and

since their return, have either pleaded guilty or been con-

victed by trial of terrorism-related offenses. Convictions

can serve as a check on self-serving information, but also

introduce other methodological problems.

On one hand, U.S. federal investigators and law en-

forcement can corroborate aspects of travelers’ stories

during court proceedings. Also, if travelers are already

cooperating with law enforcement, they have little

incentive to lie directly about their motivations for

traveling or their activities in Syria and Iraq.

On the other hand, if they are awaiting sentencing,

they can inflate or deflate aspects of their actions

in the hope of receiving more lenient treatment. In

any event, the authors made a considerable attempt

to qualify the statements made by travelers that are

presented in this report.

From this material, the list of travelers was narrowed

down to a sample, using several selection criteria

highlighted below. This report codes travelers using

demographic variables: age; gender; state of origin;

current presumed status; U.S. citizenship/permanent

12 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

meThodoloGy and sTaTisTics

resident status; whether they had been apprehended

or prosecuted; and whether they returned to the U.S.

Using these factors, combined with investigations

into their travel and role in jihadist groups, the au-

thors classified travelers (where possible) into one

of three categories: pioneers, networked travelers,

and loners.

Definitions

This report defines “American jihadist travelers” as U.S.

residents who traveled to Syria and/or Iraq since 2011

and affiliated with jihadist groups active in those coun-

tries. An additional selection criterion requires sample

subjects to have a legal name. Each aspect of this defini-

tion is explained below.

U.S. Residents

The sample includes U.S. citizens, U.S. permanent resi-

dents, temporary and unlawful residents of the U.S., and

other individuals with substantial ties to the U.S. The

term “American” is often used throughout this report to

refer to these individuals.

Travel to Syria and Iraq

In order to be included in the sample, Americans must

have successfully traveled to Syria or Iraq to join jihadist

groups from 2011 onward.

The authors chose 2011 as the starting point as it

marked the beginning of protests against the regime

of Bashar al-Assad in Syria and the formal start of

the armed insurgency against al-Assad and the Syrian

Arab Republic.

4

More importantly, 2011 marked the

arrival of the first foreign combatants in Syrian jihad-

ist groups.

5

Since 2011, at least 50 Americans have been arrested

for attempting to join IS overseas, with at least 30 more

attempting to join other jihadist groups.

6

Attempted, but

unsuccessful travelers are not included in the sample.

The traveler in question must have successfully entered

Syrian or Iraqi territory.

With the recent decline of IS territory in Syria and

Iraq, American travelers have explored other areas as

potential destinations for jihadist travelers.

7

There are

documented instances of American jihadist travelers

to several other countries, including Yemen, Libya,

Somalia, and Nigeria. However, these cases are not in-

cluded in the sample.

OTHER DESTINATIONS

From 2011 onward, Syria and Iraq were

the preferred destinations for travelers.

However, there are notable cases of

American jihadists who chose other

destinations.

Mohamed Bailor Jalloh, a Virginia resident,

traveled to West Africa in June 2015. During

his trip, he contacted IS members active in

the region and planned to travel onward to

join IS in Libya. However, he did not make

the journey. Instead, he returned to Virginia

and was arrested after planning an attack

on members of the U.S. military.

Mohamed Rak Naji, a citizen of Yemen and

legal permanent resident of the U.S., trav-

eled to Yemen in 2015 to join the regional

IS afliate. He eventually returned to New

York and was in the process of planning an

attack when he was apprehended by law

enforcement.

Sources: “Affidavit in Support of a Criminal Complaint.”

2016. USA v. Mohamed Bailor Jalloh, United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Case: 1:16-mj-00296. https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/

extremism.gwu.edu/files/Jalloh%20Affidavit%20

in%20Support%20of%20Criminal%20Complaint.pdf;

“Complaint and Affidavit In Support of Arrest Warrant.”

2016. USA v. Mohamed Rafik Naji, United States District

Court for the Eastern District of New York. Case: 1:16-

mj-01049. https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/extremism.

gwu.edu/files/Naji%20Complaint%2C%20Affidavit%20

in%20Support%20of%20Arrest%20Warrant.pdf.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 13

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

Association with Jihadist Groups

In order to be included in the sample, a traveler must

have either:

• associated with a U.S. designated FTO that ascribes

to Salafi-jihadist ideology while in Syria and Iraq

8

or,

• associated with a non-designated militant group that

ascribes to Salafi jihadist ideology.

The authors use Quintan Wiktorowicz’s definition

of Salafi jihadist groups, namely, organizations that

“[support] the use of violence to establish Islamic

states.”

9

This interpretation directly applies to the

two bedrock organizations of the global Salafi-jihadist

movement, al-Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS).

Both groups, despite differences in how, when, and

where violence is considered permissible, extensively

use force in pursuit of establishing a system of Islamic

governance in the territory they control.

10

Since 2011, a seemingly endless number of jihadist or-

ganizations have been established in Syria or Iraq. Two

designated organizations are especially dominant. The

Islamic State (IS) initially emerged from the frame-

work of AQ’s affiliate in Iraq (AQI), but gradually

separated from AQ’s central leadership. In June 2014,

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared the re-establishment

of the Caliphate.

11

Meanwhile, AQ’s regional affiliate in Syria continued

operations under the banner of the central leadership.

This subsidiary has gone by several different names,

but most sources refer to it by its original name, Jabhat

al-Nusra (JN). Under the leadership of Abu Mohammad

al-Julani, the organization underwent a de jure separa-

tion from AQ’s central leadership in 2016, and renamed

itself Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (Front for the Conquest of the

Levant).

12

As all of the American travelers in the sample

who aligned with AQ’s affiliate did so while it was still

called Jabhat al-Nusra, the authors refer to the group

throughout the report using this name.

A third group represented in the sample is Harakat

Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya (The Islamic Movement of

the Freemen of the Levant, known commonly as Ahrar

al-Sham). Ahrar al-Sham is an umbrella organization

for dozens of Salafist and Islamist battalions operat-

ing in Syria.

13

Unlike AQ, IS, and JN, it is not a U.S.

designated terrorist organization. Specific battalions

within Ahrar al-Sham associated with the Free Syrian

Army (FSA), which at various points in time has re-

ceived support from the U.S.-led coalition.

14

However, as Hassan argues, while Ahrar al-Sham has

slightly different positions on specific tactics and

methods than AQ, IS, or JN, “people in rebel-held

Syria still see Ahrar al-Sham as it is, as a jihadist orga-

nization … the apple has not fallen far from the tree.”

15

The group also utilizes violence towards the goal of

constructing Islamic governance.

16

Thus, this report

considers Americans who associated with Ahrar

al-Sham to have joined a jihadist group in Syria.

Association is defined broadly in this report. It includes

documented evidence of an individual participating

in a range of activities for a jihadist group, including

directly fighting for the group, attending a group’s

training camp, participating in military operations

alongside the group, providing funding or services to

the group, or other activities covered under the mate-

rial support statute.

17

The sample excludes Americans who have traveled to

Syria and Iraq and affiliated with other militant groups

or designated FTOs that are not Salafi-jihadist. For

instance, there are reports of U.S. persons or residents

fighting alongside a litany of Kurdish militant organi-

zations (for example, with Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, also

known as the YPG or People’s Protection Units),

18

with

the Free Syrian Army (FSA),

19

and militant organiza-

tions affiliated with the Syrian regime.

20

These travelers

are not included in the sample unless there is evidence

that they assisted or associated with jihadist formations

during their time abroad.

Legal Name

Propaganda material and bureaucratic forms released

by jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq identify several

individuals as “Americans.” With rare exceptions, this

material does not list travelers by their real, legal names.

14 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

meThodoloGy and sTaTisTics

Instead, they default to using the traveler’s kunya, or

Arabic nom du guerre.

The traditional term used to identify Americans is

al-Amriki (the American). In some cases, a traveler

identified in jihadist material as al-Amriki could be

cross-listed with the legal names of American travelers

and identified. For example, Abu Hurayra al-Amriki was

found to be the kunya of Moner Abu-Salha. Abu Jihad

al-Amriki referred to Douglas McCain.

21

Zulfi Hoxha

adopted the kunya Abu Hamza al-Amriki.

22

However, some American travelers chose other kunyas

based on their individual ethnic backgrounds. Talmeezur

Rahman, a native of India who attended university in

Texas, went by Abu Salman al-Hindi (the Indian).

23

Alberto Renteria, a Mexican-American who grew up

in Gilroy, California, took the kunya Abu Hudhayfa

al-Meksiki (the Mexican).

24

In at least ten cases, the authors found individuals

who were identified as “al-Amriki.” However, absent

a connection to a legal name, these cases could not be

included in the sample. The designation al-Amriki,

while commonly used to refer to Americans, is used to

refer to individuals with other nationalities who may

not have any connection to the U.S.

25

Without a link to

a legal name, individuals could potentially be included

twice in the dataset, once by their legal name and once

by their kunya.

Finally, in the cases without a legal name, it was in-

credibly difficult for researchers to uncover essential

demographic information about the traveler in ques-

tion. Therefore, these individuals were excluded from

the sample.

UNIDENTIFIED “AL-AMRIKI”

Several individuals identifying themselves as “al-Amriki” have appeared in jihadist propaganda

material since 2011. Many are not mentioned in this report, as the authors could not verify their

true names or details about their stories. Notable examples include:

•

Abu Muhammad al-Amriki famously appeared in a February 2014 IS video, criticizing the

leaders of JN and explaining his decision to defect from the group to join IS. Speaking in

heavily-accented English, he claimed to have lived in the U.S. for over 10 years. His real name

and status in the U.S. are unclear, but due to his social media activity and connections in Syria,

he was assessed to be a native of Azerbaijan. He was reportedly killed in January 2015.

•

In March 2015, IS claimed that one of its militants, Abu Dawoud al-Amriki, conducted a suicide

bombing in the Iraqi town of Samarra against Iraqi troops and Shi’a militia groups. He was

the rst reported American to conduct a suicide attack on behalf of IS.

Sources: Lonardo, David. 2016. “The Islamic State and the Connections to Historical Networks of Jihadism in Azerbaijan.”

Caucasus Survey 4 (3):239–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761199.2016.1221218; al-Bayan radio news bulletin, March 2, 2015.

Surely Guide Them To Our Ways,” a May 2017 video from IS’

Ninawa province in Iraq.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 15

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

THE TRAVELERS

ABDUL AZIZ, Ahmad Hussam al-Din Fayeq

ABOOD, Bilal

ABOUSAMRA, Ahmad

ABU SALHA, Moner

ADEN, Abdifatah

AHMED, Abdifatah

aL-HAYMAR, Ridwan

ALI, Arman

ALI, Omar

aL-JAYAB, Aws Mohammed Younis

aL-KAMBUDI, Sari Abdellah

ALLIU, Erius

aL-MADIOUM, Abdelhamid

aL-MOFLIHI, Ahmed

BAH, Mamadou

BHUIYA, Mohimanul

BRADLEY, Ariel

CLARK, Warren

COOK, Umar

DEMPSEY, Brian

DENNISON, Russell

DOUGLAS, Robert

eL-GOARANY, Samy

FAZELI, Adnan

GARCIA, Sixto Ramiro

GEORGELAS, John

GEORGELAS, Joya “Tania”

GREENE, Daniela

HARCEVIC, Haris

HARROUN, Eric

HOXHA, Zulfi

IBRAHIM, Amiir Farouk

INGRAM, Terry

ISMAIL, Yusra

JAMA, Yusuf

KANDIC, Mirsad

KARIE, Hamse

KARIE, Hersi

KATTAN, Omar

KHAN, Jaffrey

KHWEIS, Mohamad Jamal

KLEMAN, Kary Paul

KODAIMATI, Mohamad

KODAIMATI, Mohamad Saeed

KODAIMATI, “Rahmo”

MAMADJONOV, Saidjon

MANSFIELD, Nicole Lynn

MASHA, Mohamed Maleeh

McCAIN, Douglas

MOHALLIM, Hanad Abdullahi

MOHAMUD, Abdirahman Sheik

MUHAMMAD, Saleh

MUTHANA, Hoda

NASRIN, Zakia

NGUYEN, Sinh Vinh Ngo

NIKNEJAD, Reza

NUR, Abdi

PAZARA, Abdullah Ramo

RAHMAN, Talmeezur

RAIHAN, Rasel

RENTERIA, Alberto

ROBLE, Mohamed Amiin Ali

SHABAZZ, Sawab Raheem

SHALLCI, Sevin

16 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

meThodoloGy and sTaTisTics

M

<<JIHADIST<<TRAVELERS<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

AMERICAN

AMERICAN

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 17

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

Statistics

This sample of 64 jihadist travelers comprises a range

of ages, ethnic backgrounds, states and cities of origin,

group affiliations, and socio-economic statuses.

•

The average age at time of travel was around 27 years

of age.

• 89% of the dataset are men.

• At least 70.4% were U.S. citizens or legal permanent

residents prior to departure.

•

Travelers came from 16 different states; the states

with the highest rates of travelers are Minnesota,

Virginia, and Ohio.

•

Upon arrival in Syria, 82.8% affiliated with the Islamic

State (IS), while the remainder (17.2%) affiliated with

other jihadist groups.

• 22 travelers (34.4%) are believed to have died in Syria.

12 (18.8%) were apprehended in the U.S. or overseas,

and 3 (4.7%) returned to the U.S. without facing

charges.* 28 travelers (43.8%) are at large, or their

status and whereabouts are publicly unavailable.

• 12 travelers (18.7%) returned to the U.S. The majority

(75%) of returned travelers were arrested and charged.

* One traveler returned to the U.S. from Syria and did not

face public charges. Later, he went back to Syria, where he

conducted a suicide bombing attack.

Demographics

Within the sample, the average age that a traveler em-

barked on their journey to Syria and Iraq was 26.9.

26

The youngest travelers in the dataset were 18 years old.

Minor travelers, whose identifying information is sealed,

meaning that it is not made available to the public, are

not included in the sample. The youngest, Reza Niknejad,

went to Syria and joined IS shortly after his 18th birth-

day, with the assistance of two high school classmates

who were eventually tried as adults for assisting him.

27

On the other end of the spectrum, the oldest American

traveler with a known age was 44 when he traveled to

Syria.

28

Kary Kleman, a Floridian, claimed that he mi-

grated to Syria to participate in “humanitarian” activities,

later realizing that what led him to Syria was a “scam.”

29

Kleman surrendered to Turkish border police in 2017;

he was promptly arrested on charges that he fought for

IS. His extradition to the U.S. is pending.

30

A majority of the travelers in the sample (70.4%)

were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents.

Furthermore, two travelers were granted refugee status

in the U.S. before departure, and another was studying

in the U.S. under a student visa. Sixteen cases (25%)

involve an individual whose residency status could not

be determined.

Men comprise 89% of the sample. However, in assessing

the gender breakdown of American jihadist travelers, it

is essential to consider potential methodological barriers.

Samples of Western travelers may underestimate the

number of women, particularly those that draw largely

from publicly available data. Women jihadists are more

likely to avoid detection and apprehension than their

male counterparts, and are possibly underrepresented

in datasets as a result.

31

In this report’s sample, the seven

cases (11%) of American women jihadist travelers are

important for assessing the overall mobilization. This

number may not reflect the extent of American women’s

participation in jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq. Studies

of European travelers have found higher percentages of

women travelers. A 2016 study of all Western travel-

ers found that around 20% were women, but in some

countries, women represent as much as 40% of the

contingent.

32

One of the earliest known American cases of jihadist

travel to Syria or Iraq was Nicole Lynn Mansfield, a

33-year-old from Flint, Michigan, who left for Syria

in 2013. Mansfield, a convert to Islam, was the first

American to have been killed in Syria.

33

She was shot

and killed during a confrontation with Syrian govern-

ment forces in the Idlib province in May 2013.

34

There

are multiple conflicting accounts of which jihadist group

she was affiliated with at the time of her death: Syrian

government sources claim she was fighting for JN and

was killed after throwing a grenade at Syrian soldiers.

Ahrar al-Sham also claimed her as a member.

35

18 | The GeorGe WashinGTon UniversiTy ProGram on exTremism

meThodoloGy and sTaTisTics

In November 2014, 20-year-old Hoda Muthana (kunya:

Umm Jihad) left her hometown of Hoover, Alabama, for

Syria. Prior to her departure, she was active in the com-

munity of English-speaking IS supporters on Twitter

and other social media sites, and continued her online

presence after arriving in Syria.

36

Reports at the time

suggested that she likely lived in the city of Raqqa with

a notable cluster of Australian IS supporters, including

her husband, Suhan Rahman (Abu Jihad al-Australi).

37

Ninety days after their marriage, Rahman was killed

in a Jordanian airstrike.

38

Muthana’s current status and

whereabouts are unknown.

39

Zakia Nasrin, her husband Jaffrey Khan, and her

brother Rasel Raihan all entered Syria through the Tal

Abyad border crossing in the summer of 2014.

40

Nasrin

is a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Bangladesh.

41

Shortly after graduating from high school, she mar-

ried Khan, whom she met online. Her friends noted

her increasingly conservative behavior following

her marriage.

42

Following arrival in Syria, Khan and

Nasrin had a daughter. Nasrin allegedly worked as a

doctor in a Raqqa hospital controlled by IS.

43

Rasel

Raihan was killed in Syria; Nasrin and Khan’s statuses

remain unclear.

44

Despite the small sample size, American jihadist

women travelers help shed light on Western women’s

participation in jihadist networks. The three women

above, alongside others in the sample, defy convention-

al stereotypes about how and why women (especially

Western women) participate in jihadist movements.

Although many presume that female jihadists are

duped into participation, and motivated by the per-

sonal pursuit of love or validation, their contributions

and motivations for engagement vary as much as

their male counterparts.

45

Though often relegated to

support roles, women’s more “traditional” efforts as

the wives and mothers of jihadists are not necessarily

passive either. American women were committed to

the jihadist cause and decided to travel on their own

accord. They also appear to have played significant roles

in their respective jihadist organizations.

46

Muthana

highlights the role of Western women in networks of

online jihadist supporters, Nasrin served in a critically

important and understaffed non-combat position (in a

hospital), and Mansfield may have been more directly

involved in operations.

Geography

The sample includes travelers from 16 states. It is

paramount to assess total figures alongside the rate of

recruitment in proportion to the total population. The

rates used in this report are generated by taking the

number of travelers from a state or metropolitan statisti-

cal area and dividing them by either the total population

of the state or the Muslim population in the state.

47

To

provide a more accurate sample, these figures are then

multiplied by 100,000 (for the total population rate) and

1,000 (for the Muslim population rate), resulting in es-

timates of how many jihadist travelers in Syria and Iraq

AMERICAN CHILDREN IN SYRIA AND IRAQ

Minors are excluded from the sample.

However, there is evidence that some

American children traveled to Syria or Iraq

alongside their families. Some, including

Zakia Nasrin and Jaffrey Khan’s daughter,

were born in jihadist-controlled territory.

In 2017, a 15-year-old Kansas teenager es-

caped IS-held territory after living there for

ve years. She left the U.S. with her father

and traveled to Syria. There she married a

IS ghter, and was pregnant with his child

when she escaped. Additionally, IS released

a video in August 2017 that depicted an un-

named young boy in jihadist-held territory

making threats against the U.S. In the video,

the boy claimed to be an American citizen.

Sources: “‘We Were Prisoners’: American Teen Forced

into ISIS Speaks.” 2017. CBS News. October 11, 2017.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/american-teen-

forced-into-syria-by-father-escapes-isis-in-raqqa;

Dilanian, Ken, and Tracy Connor. 2017. “The Identity of

the ‘American’ Boy in an ISIS Video Is Still a Mystery.”

NBC News. August 24, 2017. https://www.nbcnews.

com/news/us-news/u-s-trying-identify-american-boy-

isis-video-n795691.

The Travelers: american JihadisTs in syria and iraq | 19

meleaGroU-hiTchens, hUGhes & cliFFord

from a particular state there are for every 100,000 people

and 1,000 Muslims in the state. Finally, states with less

than two travelers are not included to avoid inferences

from incomplete samples.

48

This method places the issue

of jihadist travel in the U.S. in the proper context by

using a proportional rate.

Calculated this way, the states with the largest fre-

quency of jihadist travelers per 100,000 people are

Minnesota (0.127 travelers), Virginia (0.048 travelers),