Understanding the pandemic’s impact

on the aviation value chain

December 2022

Contents

INTRODUCTION 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4

ANNEX C: WACC ESTIMATES 23

This work is independent, reects the views of IATA and McKinsey, and has

not been commissioned by any business, government, or other institution.

3 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Introduction

Since 2005, IATA and McKinsey & Company have jointly looked

at value creation across the aviation value chain. This analysis

examines the entire value chain, covering aircraft and engine

original equipment manufacturers (OEMs); lessors; airports;

air navigation service providers (ANSPs); ground handlers;

maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) providers; catering

companies; airlines; global distribution systems (GDSs); and

freight forwarders. The value chain analysis presented here

excludes upstream value creation by oil companies. Given the

dierentiated nature of oil companies, prots attributed to

jet fuel production alone are not transparent. Hence, this has

been excluded.

While acknowledging the human toll the COVID-19 pandemic

has exacted, the focus here is on economic value creation,

dened as the dierence between the return on invested

capital (ROIC) and the weighted average cost of capital (WACC)

— thereby taking the lens of an investor. ROIC measures

the earnings available to pay debt and equity investors in

relation to the capital invested. The WACC can be seen as

the opportunity cost for the investor, as it is a measure of the

alternative return the investor could have had if the capital

were invested in an asset with a similar risk prole. The

dierence between the two indicates economic protability.

If the ROIC is greater than the WACC, then value is being

created. Conversely, if the ROIC is lower than the WACC, then

economic value is being lost.

This report covers 2020 and 2021 and deepens the

assessment of value creation by including a larger sample

of companies in each sector. COVID-19 led, and still leads,

to signicant loss of lives, and daily life has been upended

in countless ways. Businesses are aected in various ways

too. This report provides a starting point for understanding

performance pre-pandemic and during COVID-19, and aims

to inform the debate about how to enhance value creation and

eciency across the whole value chain. (For an analysis of

the aviation value chain in 2020, please see McKinsey’s article

Taking stock of the pandemic’s impact on global aviation).

First, the report investigates the longer-term performance of

the value chain. It then dives deeper by sector to understand

what drives that performance. Next, it assesses the value

chain dynamics and forces acting upon the airline sector

which help explain performance. It concludes by looking at

what could be done to enhance value creation in the value

chain going forward.

4 Understanding the Pandemic’s Impact on the Aviation Value Chain

Executive summary

The aviation value chain consists of a diverse set of sectors

in terms of size, structure and performance. Pre-pandemic,

the value chain as a whole generated an economic loss of

approximately USD 5 billion per year. Airlines consistently

were the weakest link across the value chain, generating an

economic loss of approximately USD 18 billion per year.

Amid lockdowns and travel restrictions, all sectors making up

the aviation value chain suered signicant losses in 2020 and

2021 - except for air cargo carriers and freight forwarders who

experienced yield increases given undersupply and sustained

demand. With economic losses of USD 175 billion in 2020 and

USD 104 billion in 2021, airlines showed the largest economic

losses during the pandemic. Of the other sectors, those with

greater shares of xed costs, such as airports, suered more

and saw less ROIC recovery in 2021 versus 2020 than those

with a more variable cost base, such as ground handlers.

The great disparity of returns across the value chain — where

some sectors match the most protable sectors globally, and

others are near the bottom of cross-sector performance —

existed long before the pandemic. Airlines' under-performance

has its roots in factors such as low entry and high exit barriers,

high sensitivity to external shocks, the fragmented nature of

the industry, and a more concentrated supplier landscape, to

name a few.

As the value chain is only as strong as its weakest link,

all sectors that make up the chain have an interest in one

another's ability to perform. To expand the value created for

all participants, value chain partners can consider various

mutually reinforcing steps. These include improving service

and reliability by working together across the value chain,

pursuing opportunities for greater data and insights sharing,

removing ineciencies in the value chain, working together

on decarbonization, collaborating to meet ever-changing

demand in customer segments, and enhancing resilience and

robustness.

Aviation makes a signicant economic contribution to

societies globally. By jointly working to enhance performance

across the value chain, all sectors should be able to generate a

a return to its investors beyond the minimum based on its risk

prole.

5 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

The aviation sector is impacted by all forms of macro-

economic, natural, and other shocks, rendering the

sector highly cyclical. Over time, the sector, and airlines

in particular, have accumulated considerable expertise in

crisis management. Those skills were in full display during

the pandemic, as airlines took full advantage of the new

opportunities in air cargo in innovative ways. Prior to the

pandemic, the Global Financial Crisis too brought greater

resilience to the industry, led by North America. In its wake,

airlines posted uninterrupted operating prots from 2010 to

2019 — a period that attracted considerable investor interest

to the airline industry. Protability was not uniform across

the airline industry, however, and was the highest in markets

with fewer infrastructure constraints, favorable regulatory

environments, and a greater openness to consolidation.

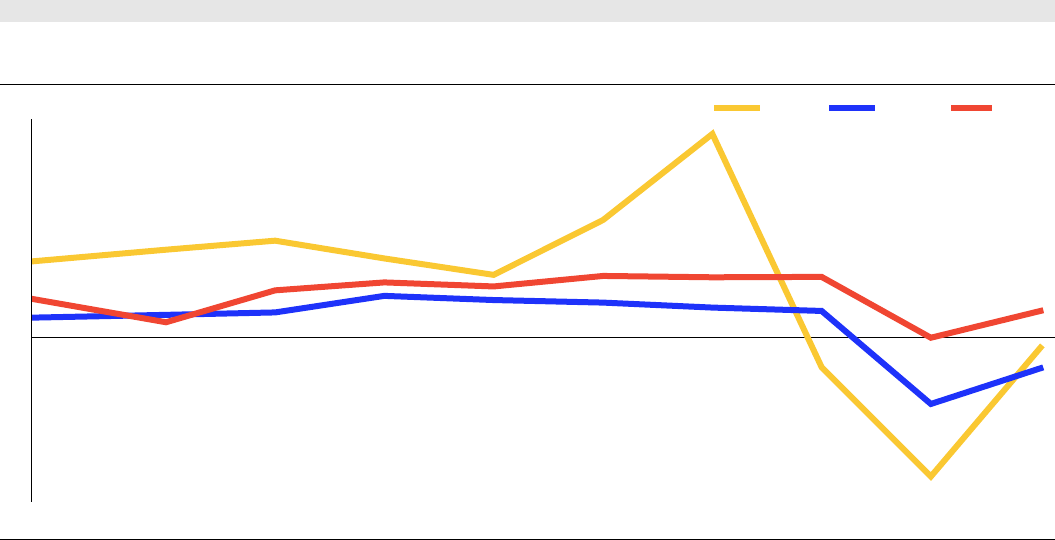

In spite of this period of consistent operating prots, the

airline sector did not produce economic returns dened as the

dierence between the return on invested capital (ROIC) and

the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) (Exhibit 1). In fact,

on this basis, airlines were consistently the weakest link across

the aviation value chain over the 2012-19 period (Exhibit 2).

Jet fuel prices uctuated signicantly between 2012 and

2019, with a low point of approximately USD 52 per barrel

in 2016 to a high point of USD 130 per barrel in 2012. As a

result, the fuel share of airline operating expenses uctuated

between 22% and 33% in this period. Airline sector ROIC

averaged approximately 6% during this period, versus 8% for

the oil & gas sector.

Pre-COVID-19, the air transport value chain generated an economic loss of USD ~5 billion p.a.

driven by large airlines losses

Average annual economic prot/loss by subsector, 2012-2019, USD Billion

1

Manufacturers

1. Based on invested capital excluding goodwill, extrapolated to total industry.

2. Computed as cumulative economic prot divided by cumulative sector revenue over the period.

3. Sector economic prot for lessors estimated based on sample economic prot as share of revenue and as share of eet value, the combination of which is expressed as a range.

2.2

1.9% ~0.1% 4.4% 3.0% 3.8% 5.1% 0.9% -2.4% 2.1% 8.5%

Lessors

3

(0.1) – 0.2

ANSP

1.0

Airports

4.6

0.6

1.5

0.3

2.0

0.7

Catering Ground MRO Airlines Freight

Forwarders

GDS/

Travel Tech

TOTAL

xx

Economic prot as share of revenue

2

, %

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

(5.3) – (4.9)

(17.9)

ROIC for the airline industry remained below WACC in pre-COVID-19 years;

worst ever result in 2020 with improvement in 2021

Airline industry ROIC excluding goodwill vs. median WACC, 1996-2021, %

ROIC excluding goodwill

10

8

6

4

2

0

1996 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16 18 20 22

-2

-4

-6

-8

-10

-12

Median WACC

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Taking a step back:

6 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Changes during the pandemic

Global airline trac (measured by revenue passenger

kilometers) declined by 66% in 2020, and by 58% in 2021,

compared to 2019, producing an economic loss of USD 244

billion in 2020 and USD 146 billion in 2021 across the value

chain (Exhibit 3). These are hyperbolic losses, considering that

in the best year for the value chain, 2015, economic prot was

limited to USD 12 billion for all sectors combined.

Amid lockdowns and travel restrictions, all aviation sectors

suered signicant losses in 2020 and 2021 — except for air

cargo carriers and freight forwarders where supply-demand

imbalances led to increases in yields, and value creation.

Sectors with greater shares of xed costs, such as airports,

suered more than those with a more variable cost base, e.g.,

ground handlers, while airlines lost the most.

ROIC improved across the value chain in 2021 compared

to 2020, and the rebound in terms of the degree of change

in ROIC diered materially by sector (Exhibit 4). Airports

rebounded the least compared to other aviation sectors in

2021, with ROIC improving by 0.9 percentage points. At the

other end of the spectrum, the manufacturers showed a

24.5 percentage point increase in ROIC. The other sectors

in the value chain saw their ROIC rise by between 5 and 10

percentage points, generally speaking. Nevertheless, all

sectors, except the freight forwarders, stayed in the red in

2021.

Jet fuel prices initially came down in 2020, from approximately

USD 80 per barrel in 2019 to USD 47 in 2020. But in 2021,

prices rebounded to USD 78, and the forecast average for

2022 is USD 126. Where airline sector ROIC came to -5.9% in

2021 as a result of the pandemic, the oil & gas sector reached

11.4%.

Exhibit 3

Exhibit 4

In 2021, all subsectors noted sizable economic losses – air cargo was the only bright spot

Economic prot/loss by subsector, 2021, USD Billion

1

Manufacturers

1.

Based on invested capital excluding goodwill, extrapolated to total industry.

2.

Computed as cumulative economic prot divided by cumulative sector revenue over the period.

(4.4)

-6.9% ~ -14% -9.3% -39.5% -12.6% -3.1% -2.7% -20.6% 5.8% -22.4%

Lessors

(4.9) – (4.6)

ANSP

(1.5)

Airports

(34.3)

(1.7)

(0.8)

(0.8)

6.8

(0.8)

Catering Ground MRO Airlines Freight

Forwarders

GDS/

Travel Tech

TOTAL

4.1

xx

Economic prot as share of revenue

2

, %

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

(146)

(104.1)

ROIC change 2021 vs. 2020: OEMs and freight forwarders in the lead

Manufacturers

ROIC change 2021 vs. 2020

Percentage points

Change in economic prot 2021 vs. 2020

USD Billion

1. Change in ROE.

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

Lessors

5.1

1

3.8

ANSP

5.1 2.0

Airports

0.9 4.7

Catering

4.7 0.3

Ground

10.7 2.8

MRO

7.9 1.2

Airlines

6.8 71.3

Freight Forwarders

16.8

3.8

GDS

8.5 0.4

24.5 7.7

7 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Performance and recovery by sector

Airlines

The airline sector produced an economic loss of USD 175

billion in 2020 (10 times larger than the average annual value

destruction pre-pandemic) and USD 104 billion in 2021,

resulting in economic prot margins of -46% and -21%

respectively.

Plotting the economic prot of companies, ordered from low

performers to best performers, reveals a "power curve"

1

;

Power curves have tails that rise and fall at exponential rates,

with long atlands of middle-performing companies. Airlines'

power curves are, unsurprisingly, skewed to the negative.

The vast majority of airlines, 104 out of a sample of 111 in

2019, nd themselves in the middle atland or at the left

tail-end, again illustrating the general characterization of the

industry as one that is highly competitive and for the most

part producing slim margins. However, the power curve shows

that despite overall economic losses, there are always a small

number of airlines that do achieve a return above the cost

of capital (Exhibit 5). These airlines dier in composition, are

from dierent regions, and have dierent business models

— some are low cost and some follow a network business

model , and many have borrowed from each other and become

hybrid business models. The outperformance of these

airlines can be explained by the market context and carrier-

specic factors. For instance, some airlines may be active in

more mature markets where capacity growth is in line with

underlying demand growth. Others may exhibit excellence

in factors important for attracting customers or maximizing

asset productivity, such as ancillary sales, a unique network

portfolio, and operational excellence

2

.

Frequent yer programmes, too, can be a source of signicant

value for airlines. To illustrate, it is not uncommon for

large North American network carriers to generate annual

revenue of USD 3-5 billion through mileage sales to nancial

institution partners. This revenue stream has also proven to

be less volatile during the pandemic compared to passenger

revenues.

1

Martin Hirt, "Is your strategy good enough to move you up on the power curve?", McKinsey, January 30, 2018.

2

Jaap Bouwer, Alex Dichter, Vik Krishnan, and Steve Saxon, "The six secrets of protable airlines", McKinsey, June 28, 2022.

The airline industry power curve shows the large variation in performance by year

Airline industry economic prot power curve

1

, USD Million

2001

Airlines

Value creators

3,000

2,000

1,000

0

-2,000

-1,000

-3,000

-4,000

-5,000

-6,000

-7,000

2008 2015 2019 2021

1. Number of carriers by year diers, power curve lines stretched to make equal, i.e., lines show more the distribution than the actual number of airlines.

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

Exhibit 5

8 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Air cargo was a clear, and much-needed, area of relief during

the pandemic. In 2021, of the nine value-creating airlines in the

sample, seven had signicant or pure cargo operations. Global

air cargo tonnage was roughly 7% higher in 2021 than in 2019.

Airlines idled widebodies as long-haul passenger demand

evaporated given travel restrictions. Bellies of passenger

aircraft used on long-haul ights contribute around half of

global cargo capacity normally. Strong demand, coupled

with a sharp reduction in supply, led to cargo yields spiking.

Consequently, carriers more exposed to air cargo saw less of a

decline in ROIC, and several pure-play air cargo carriers began

to create value. Airlines with limited cargo activity saw the

greatest drop in ROIC in 2021 (Exhibit 6).

Low cost carriers (LCCs) outperformed network carriers in

terms of ROIC pre-pandemic (Exhibit 7). The traditional LCC

model focuses on shorter haul point-to-point travel, which

can reduce costs through higher aircraft utilization and a more

simplied aircraft eet. It also reduces cost through ying to

secondary airports, increased seat density, and greater online

distribution share, to name a few. During the pandemic, LCCs

performed worse however. An absence of air cargo may help

to explain this.

80

60

40

20

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100

-20

-40

-60

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

More cargo led to higher returns during the pandemic

ROIC

2021, ex goodwill and after tax, %

Network

Cargo revenue share

2021, %

Cargo Low cost

Exhibit 6

Exhibit 7

LCCs in sample performed better than network carriers pre-COVID-19, but worse during the pandemic

Network versus low cost carrier ROIC ex goodwill, weighted average, 2012-2021, %

6

8

10

12

4

2

0

-2

-4

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

-6

-8

-10

-12

-14

-16

LCCNetwork

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

Based on Sample: not Representative of Full Sector

2020

2019 2021

9 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Airline performance diers signicantly by region (Exhibit8).

Pre-pandemic, North America was the only value-creating

region. This may have been due, in part, to a more

consolidated and mature market, with only moderate capacity

additions (Exhibit 9). The top-5 carriers' share of scheduled

seat capacity reached approximately 80% in North America

and ROIC performance was signicantly higher versus

other regions. Latin America, too, showed a higher degree

of consolidation, albeit not as high as North America. ROIC

performance in Latin America lagged North America driven, in

part, by greater capacity additions.

Exhibit 8

Exhibit 9

2020 2021

Pre-COVID-19, North America was the only region where airlines created value

Annual airline sector economic prot by region, 2012-2021, USD Billion

Middle East/Africa

-70

-65

-60

-55

-50

-45

-40

-35

-30

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

5

10

15

Latin America North America Asia Pacic Europe

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

2012

North America showed most consolidation and best ROIC performance pre-pandemic

Top 5 airline group share of scheduled seats within region

1

versus airline ROIC ex goodwill by region, 2000-2021, %

70

80

90

100

60

50

40

30

20

00 05 10 15 00 05 10 15 00 05 10 15 00 05 10 15 00 05 10 15

10

0

-10

-20

-30

ROICTop 5 shareNumber of carriers per region

2

North America Latin America Europe Africa & Middle East Asia Pacic

Source: McKinsey value chain modeling for IATA; Diio mi

1.

North America seen as United States and Canada. Europe includes Turkey, Russia. Latin America includes Mexico.

2.

Per August 2022. Individual active carriers.

2020 2020 2020 2020 2020

xx

152 119 321 213 287

10 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Airlines' largest operating cost component, jet fuel, showed

considerable volatility during the pandemic. After initially

dropping by approximately 40% year-on-year in 2020, prices

increased by around 70% in 2021 and by another 43% in 2022,

adding to cost pressure.

Given the historic impact of the pandemic on performance,

the airline sector took on signicant amounts of debt during

COVID-19 (Exhibit 10). Only one third of the debt taken on in

2020 was supported by governments, showing remarkable

access to credit markets in this time of crisis. Innovatively,

multiple airlines used their frequent yer programmes as

collateral to secure new loans.

Nonetheless, the additional debt burden has seen credit

scores move down several notches. The share of tracked

airlines with a C or D rating increased from 5% to 29%

between 2019 and 2021. The reduction in credit ratings could

on average lift the cost of funds by 1 percentage point and

add to the nancial challenges ahead (Exhibit 11).

The airline industry became signicantly more indebted during COVID-19

Estimated change in global airline sector debt, USD Billion

Debt 2019 Government

Loans

Deferred

Taxes

Government

Loans Guarantees

Bond issuance

(Secured, Unsecured

Convertible)

Commercial

Loans

Other

(Dip Loan, Loyalty,

Programme)

Debt 2020

58

14

28

78

39

8

Source: IATA

651

+51%

430

Government-sourced Capital markets-sourced

Exhibit 10

Exhibit 11

Credit ratings worsened signicantly during the pandemic

Airline industry distribution of credit ratings, share of S&P tracked airlines

1

, %

1. Sample size — 2019: 22, 2020: 23, 2021: 21.

Average of sample

AA-

A+

A

A-

BBB+

BBB

BBB-

BB+

BB

BB-

B+

B

B-

CCC+

CCC

CCC-

CC

C

D

0%

0%

0%

0%

14%

14%

9%

9%

9%

23%

14%

0%

5%

5%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

4%

0%

13%

9%

13%

13%

13%

13%

0%

0%

4%

0%

17%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

5%

5%

14%

5%

19%

14%

10%

14%

5%

0%

0%

0%

10%

Source: S&P

Investment

Grade

Pre-COVID-19 (2019) 2020 2021

Junk

28%

5%

4%

34%

5%

29%

11 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Airports and air navigation service providers

Airports generated around USD 4 to 5 billion in annual

economic prot between 2012-2019. Both airports' and

airlines' ROIC uctuated between 4% and 8%, but as airlines

bear more risk and have a higher WACC, they generated

economic losses over the same period

3

. If we were to exclude

North American airports which operate on a utility-like not-

for-prot basis, the airport ROIC globally is higher, varying as

a function of regulatory regimes and till structures as well as

revenues from non-aeronautical sources.

The pandemic drove airports' pre-COVID-19 positive ROIC of

around 6% into negative territory in 2020 and 2021. Airports

have broadly been more resilient than airlines in this respect

(Exhibit 12). Airports faced drops in aeronautical revenues and

passenger-related retail and services. Unsurprisingly, given the

depth of the crisis, many airports both needed and received

government support through COVID-19, which combined

with continued inows from real estate and other sources,

lessened the impact of the crisis.

ANSPs are mostly government-run, though private in countries

such as Canada and the United Kingdom. The sector is highly

fragmented at the macro level, with many individual ANSPs,

but highly concentrated at the local level, with typically one

ANSP covering one country.

The ANSP sector reported prots above WACC levels pre-

pandemic. ROIC for the sector was about 8% between 2012

and 2019 versus about 6% for airlines (Exhibit 12). ANSPs'

ROIC in 2020 and 2021 dropped to about -7% and -2%

respectively, given high xed costs and overheads, and the

reduced level of ight activity. In 2021, global scheduled ights

were down approximately 36% compared to 2019.

ANSP and airport returns compared to airlines

ROIC, excluding goodwill, 2012-2021, %

Airports

10

8

6

4

2

0

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

-2

-4

-6

-8

-10

-12

-14

AirlinesANSP

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

20212020

Exhibit 12

3

McKinsey value chain modeling for IATA.

12 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Original equipment manufacturers and lessors

The aircraft and engine OEM sector generated returns that

outperformed airlines pre-pandemic, earning a ROIC of about

16% between 2012 and 2019 (Exhibit 13). As the pandemic hit,

OEMs' ROIC fell to -26% in 2020 and -2% in 2021.

In 2020, global commercial aircraft orders were down 54% in

2019 but rebounded strongly by 154% year-on-year in 2021.

This led to a relatively strong improvement in performance

— albeit with negative economic prot — in 2021. Aircraft

manufacturing is a consolidated, global market where

companies also earn a return through after-market services.

Entry barriers are high given the capital needs for aircraft

programs and the considerable know-how and expertise

involved. Aircraft programs are complex and lengthy, and

some manufacturers have experienced production challenges

in recent years, which dented protability. There are some

relatively new entrants in the market, particularly those that

produce aircraft with fewer than 120 seats.

Lessors earned a return on equity of about 9% pre-pandemic.

In 2020, returns fell to approximately 0% as lease rates

plummeted and demand decreased. The leasing market

has high barriers to entry but is fairly fragmented. Some

consolidation has occurred, but new companies are entering

the market as well. It is a sector where there is value in

diversifying portfolios, to spread risk and tap into dierent

growth rates. There have been some defaults, and some

lessors underwent restructurings in recent years.

Lessors have seen their share of the commercial aircraft eet

grow over time. For narrowbody aircraft, the share of leased

aircraft globally increased from 42% in 2010 to 51% in 2022,

where for widebodies, the share grew from 27% to 35%. Over

that period, airlines turned increasingly to leasing and to sale-

and-leaseback solutions in order to limit equity requirements

and gain some exibility.

Overall, lessors bounced back strongly in 2021. The

sector roughly halved its economic loss in 2021 though

performance varies widely. Some airlines have renegotiated

and restructured leases, for example adopting power-by-the-

hour arrangements, especially those which went through a

bankruptcy or court-led restructuring. Still, the majority of

airlines have continued to pay leases, in some cases with a

restructuring or deferral of payments.

OEM and lessor returns compared to airlines

ROIC, excluding goodwill, 2012-2021, %

Lessors

1

25

30

35

40

20

15

10

5

0

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

-5

-10

-15

-20

-25

-30

AirlinesOEMs

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

20202019 2021

1. ROE.

Exhibit 13

13 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Catering, ground handling and maintenance, repair

and overhaul

Pre-pandemic, the catering, ground handling, and MRO sectors

outperformed the airline sector consistently in terms of ROIC

(Exhibit 14). Ground handlers' ROIC was approximately 16%

between 2012 and 2019. When trac dropped in 2020, ROIC

fell to -7%. The sector recovered well compared to others in

terms of ROIC improvement in 2021. Ground handlers’

revenues are driven by passenger and freight volumes and

the sector has lower xed costs compared to other aviation

sectors.

The catering sector's ROIC was approximately 20% between

2012 and 2019. Catering faces similar passenger-variable

revenue streams and relatively low xed costs as the ground

handler sector, with labor representing a signicant share of

operating expenses. For both segments, the market at a global

level appears fragmented, but is more concentrated at a local

airport-specic level. There is ongoing consolidation activity.

The global passenger volume, as core driver of caterers'

revenue, fell by approximately 59% in 2020 and by 52% in

2021, versus 2019. Furthermore, long-haul passengers, who

generate more catering revenue, showed a greater reduction.

As a result, caterers' ROIC dropped to -21% in 2020 and -16%

in 2021.

MROs fared better in 2021 compared to 2020, with a ROIC

of 3% in 2021, up from -5% in 2020. At a global level, the

market is fairly fragmented, but there are geographical and

component-related niches where the landscape is more

concentrated. MROs exhibit large structural dierences by

type of maintenance. Base maintenance on the air frames

is mostly labor driven, with less dierentiation across rms,

where engine MRO is more concentrated and has signicant

OEM involvement. Line maintenance is highly fragmented

with little opportunity for dierentiation, but there can be local

market concentration. Barriers to entry overall are relatively

high given the technological know-how and certication

required.

Catering, ground handling and MRO returns compared to airlines

ROIC, excluding goodwill, 2012-2021, %

MRO

25

30

20

15

10

5

0

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

-5

-10

-15

-20

-25

AirlinesGround servicesCatering

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

2019 20212020

Exhibit 14

4

https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/airline-industry-economic-performance---june-2022---data-tables.

14 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Global distribution systems – Travel tech

Pre-pandemic, GDSs were the best performing sector in

the value chain on an economic margin basis, with ROIC

signicantly above the airline sector (Exhibit 15). There are

high entry barriers on the distribution side, given the need to

build out a global network of travel agencies and airlines. On

the IT side, the core system is the passenger service system

(PSS) which is mostly supplied by two organizations. This leads

to a highly concentrated industry. Many airlines continue

to depend on GDSs for broad reach in their distribution,

particularly for high-value corporate trac.

In 2020 and 2021 ROIC for the sector dropped signicantly,

to -16% and -8% respectively. The GDS sector’s prime

revenue source lies in segment-linked booking fees, but most

companies have evolved into travel software ecosystem

businesses that oer a broader array of services.

Through the pandemic, sales shifted towards online bookings

through the airline.com and mobile channels, particularly as

business-travel volumes were harder hit than leisure travel. To

illustrate, the share of airline direct supplier online bookings

in the United States increased from 50% in 2019 to 64% in

2021

5

, and globally from 39% to 48% (Exhibit 16).

Distribution will likely continue to be a dynamic sector as travel

recovers post-COVID-19. Airlines may retain some of the

direct distribution share even as international travel returns.

IATA's New Distribution Capability (NDC) is transforming

the way airlines distribute their products through GDS and

beyond, and could also potentially lead to new commercial

relationships.

5

PhocusWright US Airline Market Report 2021-25.

GDS – Travel tech returns compared to airlines

ROIC, excluding goodwill, 2012-2021, %

GDS — Travel tech

30

35

25

20

15

10

5

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

0

-5

-10

-15

-20

Airlines

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

2019 20212020

Exhibit 15

Exhibit 16

During COVID-19 a larger share of bookings went through direct/online channels

Breakdown of airline gross bookings by channel, global, share of bookings, % and USD Billion

OTA Online supplier direct Oine

Source: PhocusWright

100% =

10%

451

2010

23%

67%

2011

513

10%

25%

64%

2012

534

11%

27%

63%

2013

548

11%

28%

60%

2014

555

12%

30%

58%

2015

522

12%

32%

56%

2016

528

13%

34%

54%

2017

570

13%

35%

51%

2018

619

14%

37%

49%

2019

631

14%

39%

46%

2020

206

17%

43%

40%

2021

282

18%

48%

35%

15 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Performance and recovery by sector

Cargo airlines and freight forwarders

Cargo was the only bright spot for the value chain in 2020 and

2021 (Exhibit 17). Of the nine airlines that were value creating

in 2021, seven had signicant or fully cargo-driven operations.

Going forward, cargo yields are expected to remain elevated,

and come down gradually as more belly capacity is reinstated.

Freight forwarders play an important role in air freight, with

approximately 80% of air cargo volumes being handled by

this sector. It is a fragmented sector, with the top companies

accounting for around 35% of sector revenue, but there is

consolidation activity. Freight forwarding has a highly variable

cost base and started out as an asset-light business. As the

industry developed, the need increased to develop more

sophisticated IT and oer, amongst others, tracking systems.

Most forwarders now oer certain logistics services as

well – warehousing and consolidation, for instance. Larger

players dierentiate themselves through sales and support

infrastructure globally to service larger shippers, and can

secure access to airline capacity at preferential terms. Thus,

over time, the sector has become harder to enter.

That said, forwarders are still exible businesses, with high

capital turnover. The average revenue per invested dollar of

capital was approximately USD 4.1, versus USD 0.9 for the

airline sector in 2019. During 2012 to 2019, freight forwarder

ROIC averaged approximately 16%. As protability is linked

with air cargo volumes and freight rates, performance

improved signicantly during the pandemic, with ROIC moving

to 22% in 2020 and 39% in 2021.

Freight forwarder and cargo carrier returns compared to airlines

ROIC, excluding goodwill, 2012-2021, %

35

40

30

25

20

15

10

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

5

0

-5

-10

-15

2019 20212020

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

1.

Full freighter pure play carriers only.

Pure cargo carriers

1

AirlinesFreight forwarders

Exhibit 17

16 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Value chain dynamics

There is a great disparity of returns across the air transport

value chain, where some links in the chain can be compared to

the most protable industries in other sectors, and other links

struggle to keep up with the utilities sector (Exhibit 18). Airlines

in particular have underperformed, and this has its roots in

several factors: low entry and high exit barriers, a high share

of xed costs, high sensitivity to external demand shocks,

a fragmented industry, and a more concentrated supplier

landscape, to name a few. This creates a highly challenging

environment and has to led to uneven distribution of prots

across the value chain.

The degree of global fragmentation, measured here through

the share of sector revenue accounted for by the top 5

companies, diers signicantly between sectors, as does the

degree to which sectors compete globally. With some sectors,

such as airports, ground handlers and caterers, the global

degree of fragmentation can dier from the local picture at a

particular city.

Performance across the aviation value chain compared to other sectors over the past 20 years

Economic prot margin quartile range by industry

1

, ex goodwill, 2002-2021, select industries, %

1.

Data set includes global top 5000 companies by market cap in 2021, excluding insurance and banks.

2.

Indicative and for entire industry. Top 5 share will dier based on segments within industries (e.g., Chemicals consists of many dierent sub-industries, not all chemicals players are active in

all). OEMs: top 5 OEM share of 2019 value of produced aircraft. Lessors: top 5 lessor share of leased eet value Q4 2021. Airports: top 5 airport group revenue share out of total 2019

market size. Catering: top 5 caterer share of 2019 total market revenue. Ground: top 5 share of 2019 market revenue. Airlines: top 5 airline group revenue share out of total 2019 industry

revenue. Freight Forwarders: top 5 air forwarder revenue share. All other sectors: share of top 5 2021 as share of total revenue in sector based on global top 5000 companies by market cap.

Median

Number of rms in sample Aviation value chain industry Quartile range

Telecom

Media

Medical Technology

GDSs — Travel Tech

Pharma & Biotech

Apparel, Fashion & Luxury

High Tech

Business Services

Consumer Packaged Goods

Consumer Services

Advanced Electronics

ANSPs

Consumer Durables

In-Flight Catering

Ground Handlers

Chemicals

Freight Forwarders

Retail

Automotive & Assembly

Aircraft — Engine OEMs

Logistics & Trading

Aircraft MROs

Basic Materials

Conglomerates

Utilities

Oil & Gas

Aircraft Lessors

Airlines

Airports

Source: McKinsey Corporate Performance Analytics; Cirium; Value Chain Model; Company reports; Airports Council International; Teal

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20

68

133

16

151

196

47

397

8

67

8

204

192

8

219

13

6

43

11

530

59

244

105

371

63

260

4

155

133

93

12%

25%

36%

31%

25%

NA

16%

19%

36%

99%

26%

39%

35%

19%

19%

63%

59%

NA

16%

43%

20%

21%

36%

45%

30%

100%

51%

38%

42%

xx

Top 5 company share, global

2

xx%

Exhibit 18

17 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Value chain dynamics

In 2011, IATA worked with Harvard Business School’s

Professor Michael Porter to examine the forces acting

upon the airline sector and their inuence on the sector’s

protability. Exhibit 19 illustrates Porter’s framework with

updated content.

More than a decade since this research, and after the largest

crisis the sector has ever seen, the question arises whether

these forces have truly changed. The answer is likely no.

Bargaining power of suppliers continues to be high. The

threat of substitutes remains, and in fact increased during the

pandemic given the surge in availability, acceptance, and use

of online meeting tools.

Barriers to entry remain relatively low and barriers to exit high.

COVID-19 saw an uptick in airline start-ups. In 2019, 42 airlines

began service, followed by 57 in 2021. New entrants were

attracted into a sector by the availability of cheaper second-

hand aircraft and leases, and availability of skilled pilots. There

were also few bankruptcies through COVID-19. Barriers to

exit remained high with various carriers receiving life support

from their stakeholders. COVID-19 did not result in as large a

reduction in carriers as may have been expected. In 2019, 59

airlines ceased operations, and this number decreased to 53

in 2020, and 33 in 2021.

Price transparency has increased further with the rise of online

travel agents and metasearch comparison websites. On the

supplier side, the strength of labor remains — with signicant

unionization. Airport privatization has continued.

Additionally, all aviation sectors operate in a highly regulated

environment. This not only relates to safety, but also to

economic performance. Most countries have ownership limits

in place for airlines, capping foreign ownership of local airlines,

for instance to 25% in the US and 49% in Europe. This has the

eect of limiting the free ow of capital and adding a barrier to

cross-border consolidation. As such, airlines do not operate in

a policy vacuum.

Competitive forces shaping the airline sector have arguably not changed or have intensied

Degree of change observed in competitive forces for the airline sector since 2011

1

Force intensied, greater competitive pressureNo change in dynamicForce reduced, lower competitive pressure

Source: McKinsey and IATA update based on original from Professor Michael Porter, 2011

1.

In 2011 this ve forces analysis was originally done by Michael Porter for IATA.

Threat of substitute products or

services: MEDIUM and RISING

Rivalry among existing competitors:

HIGH

Threat of new entrants:

HIGH

Bargaining power of channels:

HIGH

Bargaining power of buyers:

HIGH

Bargaining power of suppliers:

HIGH

Powerful labor unions especially

when controlling operations at

network hubs

Aircraft and engine producers are

both concentrated oligopolies

Airports are mostly local

monopolies

Airport services (handling,

catering, cleaning) are also

concentrated in a small number of

rms, but low switching costs

The number of customers who can

aord air travel is increasing

substantially, mainly in emerging

markets

Te chnology for web-conferencing

is improving

High speed trains are competitive

with airlines on select short-haul

routes

Travel can be delayed, limited or

done without

Environmental issues challenge air

travel

Growth has been rapid but volatile

Perishable product

Limited product dierentiation

High sunk costs per aircraft, low

marginal costs per passenger

Limited economies of scale

Signicant exit barriers

Multiple direct and indirect rivals

Limited incumbency advantages

Low switching costs

Some demand-side benets of

scale

Easy access to distribution

channels

High concentration among GDS

and aggregator websites

Websites increase price

transparency

Tra vel agents focus on the

interests of corporate buyers to

reduce travel costs

Buyers are fragmented

Air travel perceived as a

standardized product

Low switching costs for most

customers

Price sensitive, because travel is a

meaningful share of discretionary

spending

Exhibit 19

18 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

While we focus on economic value in this report, aviation

provides signicant value in other forms. Worldwide, pre-

COVID-19, aviation enabled 4.5 billion passengers to take

to the air, creating new connections and reuniting families.

Aviation supported around 88 million jobs directly, and

accounted for just over 4% of global economic activity.

Aviation generates positive externalities, especially for

countries and cities which are home to major aviation hubs,

while providing an essential service in locations with poor

connectivity to the global economy, and often life-saving

services during the pandemic.

The sectors making up the aviation value chain each

contribute to the total economic value added. The airline

sector is at the center of the value chain and its revenue ows

(Exhibit 20).

The airline sector remains a highly challenging industry where

shareholders are not rewarded with the minimum return they

should expect based on the risk prole of their investment.

The aviation value chain was negatively impacted by the

pandemic — and airlines fared the worst. However, even

before the pandemic, airlines were the only value chain sector

where investors did not get a return above the cost of capital

over a prolonged period.

What could be done to strengthen the value chain for

everyone? Companies across the value chain could consider

various actions to enhance the performance of the value chain

as a whole, and ensure nancial sustainability for all. To the

extent that the chain is only as strong as its weakest link, all

actors have an interest in one another’s ability to perform.

Expanding the value created by all value chain participants

Exhibit 20

Illustrative ow of revenues within the aviation value chain

Passengers

Freight forwarders

Source: McKinsey

Indicative revenue ows within the aviation sector, 2019, USD Billions

Cargo shippers

Airlines

Travel agents

OEMs Lessors Oil companies Airports ANSPs Handlers, caterers

379

118 44 190 99 21 53

246 20

81

43

19 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Expanding the value created for all value chain participants

Improving service and reliability by working together

across the value chain, thus attracting more customers

Individual companies across the value chain are customers

and suppliers to companies in other aviation sectors, and

together they are partners in the fullment of the customer

journey. There is an opportunity for greater value chain

collaboration to enhance the experience for customers,

thereby improving the results for all involved. Examples could

include joint mapping of full customer journeys, including

current challenges and where these occur, involving all sectors

that inuence the customer journey so it can be improved

holistically, rather than by one party at a time. If the value

chain can work together to improve reliability and comfort

throughout the journey, demand could rise.

As the value chain participant who contracts directly with

the passenger, airlines are at the center of the customer

relationship. However, airlines rely on airports, handlers,

caterers and others to bring the journey to completion

(Exhibit 21). Delays are a signicant source of frustration for

customers, and the responsibility for them is shared across

the value chain. Airlines are responsible for, amongst others,

aircraft turnarounds between ights, technical and crew

performance. However, delays are often under the purview of

air trac control, security, and airport conditions, in addition to

the weather, the eects of which could sometimes be reduced

with corrective action by the airports or the national aviation

administration. Ensuring that security checks are smooth,

frees up time for passengers to spend in the airports, boosting

retail. Swift baggage reclaim helps make a passenger’s onward

journey hassle-free. Enhanced collaboration can only bring

benets to all parts of the value chain who depend upon the

passengers airlines y.

Airlines do not own the full end-to-end customer journey — cooperation required to optimize customer experience

Not airline ownedAirline partially ownedAirline owned

Journey

Sub-journey

Customer

follow-ups

Post-trip

IROPS

1

recovery

Entertainment

In-ight

Seating

and aircraft

conguration

Refreshments

and meals

IROPS

1

mitigation

Research

ight

Shop

& Purchase

Purchase

ight

Desire/Need

Travel

Inspiration

Research

destination

Promotions

Transport

To Airport

Parking

IROPS

1

early

communication

Loyalty

programs

Lifestyle

Engagement

Partnerships

Credit cards

Check bags

Airport

Experience

Security

Airport

navigation

Shop and dine

Wait at gate

IROPS

1

recovery

Deplaning

Arrival

and On-trip

Immigration

Connections

Baggage

claim

Customs

Transport

Research

destination

Prepare

to travel

Book other

(car, hotel…)

Arrange

travel

documents

Pack

Make

departure

arrangements

Check-in

for ight

Source: McKinsey

1.

IROPs are Irregular Operations, i.e. extraordinary situations in which a ight does not operate as scheduled.

Exhibit 21

20 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Expanding the value created for all value chain participants

Pursuing opportunities for greater data and insights

sharing across the value chain

Companies within the value chain are starting to put the

data-rich environment in which they operate to greater use

by, for instance, using advanced data techniques to provide

more tailored oers to customers, or to engage in predictive

maintenance. Beyond this, there is an opportunity for greater

sharing of data and insights across the value chain. This could

include enhanced data sharing between airlines, airports,

and handlers about expected volumes — leading to better

short-term projections and enhanced operational planning

at airports. Initiatives such as airport collaborative decision-

making (A-CDM) could be further rolled out to enhance joint

performance of the value chain and the passenger experience.

A-CDM's focus lies on improving the eciency and resilience

of airport operations by encouraging airlines, airports,

handlers and ANSPs to collaborate more and to exchange

accurate and timely data and insights.

Removing ineciencies in the value chain

Tackling ineciencies could enhance performance for the

whole chain. For example, longer than necessary ight paths

within regions lead to air trac control (ATC) ineciencies,

additional fuel burn, and associated climate impact. The

European ATC body Eurocontrol indicates that ights in

Europe use, on average, between 9% and 11% more fuel than

the most ecient ight routes. Improvement initiatives, such

as Europe's Single European Sky, can help address these

ineciencies, boost protability, and reduce CO

2

emissions

for all participants in the value chain.

Working together on decarbonization

Decarbonization is the prime challenge at this time. Moving

the airline industry to net zero by 2050 requires signicant

innovation and value chain cooperation, potentially through

novel forms of collaboration. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)

will play a major role in airlines’ path to net-zero operations but

announced supply does not equal expected demand.

Decarbonization is a challenge that will require the value chain

working together to solve. The industry needs fuel suppliers

to invest in capacity — likely backed with commitments from

airlines and with support and incentives from governments.

Airports need to develop a new fueling infrastructure, must

decarbonize their own operations, and give passengers

low-carbon onward ground transport choices. Handlers and

caterers need to work with their host airports, to electrify and

improve energy eciency. Airframe and engine OEMs need

to develop ever-cleaner technologies such as hydrogen-

powered ight. ANSPs must innovate to reduce emissions on

conventional ights, while adapting regulations to permit new

forms of transport, such as eVTOL services.

The investment needed is signicant, and it will take everyone

working together to get aviation to net zero.

Collaborating to meet ever-changing demand

in customer segments

Airlines and their value chain partners face ever-changing

patterns of customer demand and do adapt their business

models to such evolutions. The more a market matures, the

more dierentiated demand tends to become. Certain trends

might have been accelerated because of the pandemic.

To be sure, working from home has impacted the entire

transportation sector in multiple ways. For airlines, this has

spread out demand for ights over the week in many cases.

Much speculation abounds regarding business travel in the

post-COVID-19 world, but the jury is still out on whether

lowered demand will be anything but transitory.

On the other hand, business travelers might opt more often

for economy-class travel, certainly on shorter ights. Leisure

travelers have been seen to chose business class for their

holiday trips. Hence, there is a uidity among market segments

and demand morphs constantly along the spectrum from the

ultra-low-cost option to rst-class travel and private jets.

In response to changing customer demand, airline business

models have become much more hybrid. Today, few airlines

are "pure" in the original sense of the terms "low-cost" or

"network” carriers, as both have borrowed from each other

and adapted their oering. It is vital for customer-welfare

maximization that the regulatory environment fosters

competition, innovation, and sustainability, not only in aviation

but across all modes of transportation. Consumers will then

optimize their choices and the transportation sector will be

more ecient

6

.

Enhancing resilience and robustness

Airlines have proved to be resilient, having bounced back, for

the most part, from the multiple crises the world has seen

since the inception of the industry. What arguably is less of

a feature among airlines is robustness, i.e. the ability to avoid

falling over in the rst place. Robustness can be enhanced

through creating more diverse revenue streams, in addition

to the habitual attention to costs. This might involve vertical

and horizontal integration when that is possible, maybe even

beyond the aviation value chain. Achieving robustness likely

necessitates discipline in terms of capacity expansion, and

a strengthening of alliances and collaboration among the

airlines. In essence, the goal must be not only to grow, but to

grow protably and sustainably, in order to limit the impacts

of various crises on the airline industry and the aviation value

chain.

6

"One Size does not Fit All: A Study of how Airline Business Models have evolved to meet Demand in Europe", IATA, November 2022.

21 Understanding the Pandemic’s Impact on the Aviation Value Chain

Conclusion

Aviation provides signicant benets to the

broader economy. Pre-pandemic, the aviation

value chain overall did not generate the

economic returns its investors expect. This

was led primarily by the large economic losses

of the core sector, airlines, which remain in

a challenging market structure and context.

COVID-19 led to signicant value loss for all

sectors, apart from cargo-focused ones.

As aviation emerges from the pandemic, there is

an opportunity to expand the value created for

all participants in the value chain. This requires

performance improvement within each sector

and also requires greater collaboration and

fresh ways of working across partners in the

value chain.

22 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Annex A:

Annex B:

Denitions

1.

PP&E =Property, Plant & Equipment; includes Right of use asset post IFRS16/ASC842 implementation.

2.

EBITA = Earning before Interest, Taxes and goodwill Amortization.

ROIC

Invested capital

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

Denitions

‘Return on invested capital’ (ROIC) measures the operating

performance of the company

Calculation excludes goodwill

(= amount paid over book value in an acquisition)

Invested capital (IC) represents the amount invested in the

operations of the business

Adjusted for operating leases (if applicable)

Calculation methodology

ROIC = NOPLAT/end of year operating invested capital

Used end of year values to avoid discrepancies due to M&A, perimeter or

accounting changes

IC = Operating working capital + net PP&E

1

+ net other operating assets

Before lease accounting change (IFRS16/ASC842): Operating leases

capitalized using 7.3x factor, in line with industry practices (typically 7-8x);

post accounting change RoU asset included in PP&E

NOPLAT

After tax operating prot, adjusted for operating leases NOPLAT = Adjusted EBITA

2

– Taxes

Taxes based on marginal tax rate, dierentiated per country

Before IFRS16/ASC842: prot is adjusted for leases (interest component of

lease expense added back to EBITA; assuming 7% interest rate)

Economic prot

“Excess prot” earned above the cost of capital,

expressed in USD million p.a.

Economic prot spread

Economic prot margin

= (ROIC-WACC) * Invested Capital

= ROIC-WACC

= Economic Prot/Revenues

WACC

Opportunity cost of funds invested

WACC = Cost of equity * equity weight

+ (after tax) Cost of Debt * debt weight

Example ROIC calculation — illustrative carrier

Local currency millions

Source: McKinsey value chain modelling for IATA

1.

Adjusted for operating leases, including goodwill.

2.

Capitalization multiple: 1/(1/Depreciation period + Cost of lease).

3.

For companies reporting under IFRS16 or ASC842, no adjustment made to operating prot and capitalized leases replaced with published Right of Use Asset.

ROIC

1

, percent

Adjusted EBITA

1,4363.2

Reported EBIT(A): 16,323.2

Revenues

Invested capital

22,385.0

After tax

5.4%

Pretax

6.5%

Interest income from ST investment

Dividend income from ST investments

Gain on disposal of ST investments

Exchange loss

Currency hedging gain

Net gain on nancial assets

Lease adjustment

3

: Implied interest @ 7%

Debt equivalent: 4,973.4 (see below)

Includes operating cash: 326.5 (2% of sales)

Receivables, inventories, prepayments, deferred

accounts and other current assets: 2,067.5

Minus payables, sale in advance, deferred accounts

and current provisions: (7,075.3)

Intangibles (excl. goodwill), other LT assets

(excl. derivatives), net deferred accounts minus

operating provisions (return costs of leased aircraft,

onerous leases, other)

Marginal tax

rate: 17%

Capitalized leases

3

:

Net PPE:

Working capital:

Other:

Goodwill:

Adjustments:

1,067.1

348.1

4,973.4

22,176.3

(4,636.4)

(128.3)

184.4

48

679.7 aircraft lease expense

7.3x multiple (assumptions: 7% cost of lease,

15-year depreciation period)

2

(1.0)

(0.1)

(1.2)

77.6

(26.6)

(0.7)

23 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Annex C:

It is important to note that the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) used in this analysis is the opportunity cost for investors.

It does not measure the actual cost of capital for the individual companies, but rather what ‘nancially minded’ investors would

expect to earn on an asset with similar risk characteristics.

To estimate WACC, the following formula is applied:

The cost of debt is the post-tax return on investing in the debt. The following formula is applied:

Cost of debt = (risk free rate + debt premium) × (1 − corporate tax rate).

It varies by company specic debt premiums (based on estimated credit risk) and by country specic marginal tax rates. As

noted above, this does not represent the actual cost of debt for individual companies, but rather the return an investor would

earn by investing in debt with that company/sector’s credit risk characteristics.

WACC methodology: Cost of equity

Market Risk Premium (MRP):

— MRP estimated each year to maintain (real) cost of equity around estimated long term average of 7%

— MRP = (7% + Expected ination) - Risk Free Rate

— Expected ination in year N based on actual ination for year N+1

Risk Free Rates (RF): Nominal year-end 10-year US rates for all airlines

— US government rate is the only ‘risk free’ rate; all calculations made in USD; consistent with MRP

— Value observed as of 31/12/xx

Asset Betas: Airline (0.80); Airport (0.55); ANSP (0.40); Catering (0.70); CRS (1.30); Freight Forwarders (0.80); Ground services (0.70); Leasing (1.10);

Maintenance (0.70); Manufacturers (1.10)

Debt Betas: Based on rating: AAA/BBB- (0.15); BB+/B+ (0.20); B/B- (0.25); CCC and below (0.30)

Target Debt/Equity (D/E), Airlines: Based on ratings; AAA/A- (60/40); BBB+/BBB- (67/33); BB+/BB- (71/29); B+/B- (75/25); CCC (80/20), CC/-D (82/18).

Estimate based on S&P credit ratios and observed values

Target Debt/Equity for other sectors: Airport (200%); ANSP (80%); Catering (50%); GDS (20%); Freight Forwarders (80); Ground services (50%);

Maintenance (20%); Manufacturers (15%)

4,5

1996 97 98 99

2000 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

18 19

20

2021

4,5

4,6

4,5

4,7

4,5

5,5 5,5

6,2

5,8

5,1

6,8

5,8

4,8

6,9

7,2

6,7

5,6

6,4

6,7

6,5

6,3

6,0

7,1

8,6

7,8

WACC methodology: Cost of debt

Risk Free Rate:

10-year US government rate

Tax Rates:

Marginal tax rates from the country of origin

Debt Premium

based on estimated credit rating:

Credit spread

: Last 5-year rolling average; estimated by multiplying observed credit spreads by adjustment factor (to take into account implied probability of default

for lower credit

s):

Credit rating:

Actual rating else, estimated based on nancial ratios:

Observed spreads: Dierence between yield to maturity for a basket of similarly rated 10-year company bonds (e.g., AAA, AA, A, BBB, etc.) and yield to maturity of

comparable 10-year government bond

Adjustment factor applied to BBB and below ratings, based on implied probability of default and expected loss rate

Capped for lower credit: highest possible spread is equal to MRP

Airlines: EBITDAR margin, Net Debt/EBITDAR, EBITDAR/Fixed charges, EBIT/Interest, Age of eet

Airports: EBITDA/Gross interest

Others: EBITDA/Gross interest or typical industry rating for all non rated companies

Nominal post-tax WACC = cost of equity × (1 − gearing) + cost of debt × gearing

where gearing = debt / (debt + equity).

The cost of equity is estimated using the standard Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and is equal to the risk free rate plus a

risk premium:

Cost of equity = risk free rate + re-leveraged equity beta × equity market risk premium

with re-leveraged equity beta = (asset beta − debt beta × gearing) / (1 − gearing).

24 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain

Annex D:

Airlines

The airlines studied in the analysis represent approximately

85% of the global airline sector revenue pool. To compute

sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample

of airlines studied is scaled up using its proportion of regional

sector revenues, and this is subsequently summed up to a

global estimate.

Companies included:

Europe North America Asia Pacic Rest of World

Aegean Airlines ABX Air, Inc. Air Astana Aerolineas Argentinas

Aer Lingus Air Canada Air China Aeromexico

Aeroot Air Transport Services Group (ATSG) Air India Air Arabia

Air Berlin (up to 2016) Alaska Air Air New Zealand Air Mauritius (up to 2018)

Air Europa Allegiant Travel AirAsia Avianca Holdings

Air France American Airlines AirAsia India Azul

Air Italy (up to 2018) Atlas Air Worldwide AirAsia X Comair Limited

AirBridgeCargo Cargojet Airways All Nippon Airlines COPA Holdings

Alitalia (up to 2015) Delta Airlines Asiana Egyptair

Austrian Airlines Evergreen International Airlines Bangkok airways El Al Israel Airlines

Blue Panorama Frontier Cathay Pacic Emirates

British Airways Hawaiian Cebu Pacic Ethiopian Airlines

Brussels Airlines Jetblue China Airlines Etihad (up to 2014)

Cargolux Kalitta Air China Eastern FlyDubai

Czech Airlines Mesa Airlines China Southern Airlines GOL Linhas Aereas Inteligent

Easyjet Polar Air Cargo EVA Airways Interjet

Finnair Republic Airways Garuda Indonesia Jazeera Airways

Flybe (up to 2017) Skywest Go First Kenya Airways

Iberia Southwest Airlines Hainan airlines Kuwait Airways

Icelandair Spirit Airlines Hong Kong Airlines LATAM

KLM United Airlines Indigo (Interglobe aviation) MiddleEast Airlines

LOT Polish Airlines US Airways Japan Airlines Oman Air (up to 2017)

Lufthansa Virgin America (up to 2015) Jet Airways (up to 2017) Qatar Airways

Norwegian Air Shuttle Westjet Juneyao Royal Air Maroc (up to 2018)

Pegasus Airlines Korean Airlines Royal Jordanian

Primera Air Scandinavia (up to 2017) Malaysian Airlines South African Airways (up to 2018)

Ryanair Nok Air Tunisair (up to 2017)

S7 airlines Pakistan International Airlines VivaAerobus

Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) Philippine Airlines Volaris

Swiss International Qantas

TAP Air Portugal Shandong Airlines

Turk Hava Yollari Shenzhen Airlines

Virgin Atlantic Airways SIA Group

Volotea Sichuan Airlines

Vueling Skymark

Wizz Air Spicejet

WOW Air (up to 2017) Spring Airlines

Sri Lankan airlines

Thai Airways

Vietjet Air

Vietnam Airlines

Virgin Blue/Virgin Australia

Vistara

25 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Annex: Companies included in the analysis

Airports

The airports studied in the analysis represent between 30%

and 40% of the global airport sector revenue pool. To compute

sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample

of airports studied is scaled up using its proportion of regional

sector revenues, and this is subsequently summed up to a

global estimate.

Companies included:

Europe North America Asia Pacic Rest of World

Aena Atlanta Airports Corporation of Vietnam ACSA

Aéroport de Beauvais-Tillé Chicago Midway Airports of Thailand Aeropuerto de Tocumen

Aéroport de Bordeaux - Mérignac Chicago O'Hare Angkasa Pura I Aeropuertos Argentina 2000 (up to 2014)

Aéroport de Lyon-Saint-Exupéry Dallas Fort Worth Angkasa Pura II Corporacion America Airports

Aéroport de Nice-Côte d'Azur Denver Auckland International Airport Grupo Aeroportuario del Centro Norte (OMA)

Aéroport de Toulouse-Blagnac Las Vegas Airport Beijing Capital International Airport Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacíco (GAP)

Aeroport Marseille Provence Los Angeles World Airports Changi Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste (ASUR)

Aeroporti di Roma San Francisco Airport Chongqing Airport Group Guayaquil Airport (up to 2014)

Aeroports de Paris Tampa Delhi Kenya Airports Authority

BAA/Heathrow Airport Holdings Toronto Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport ONDA

Flughafen Wien Hainan Meilan International Airport (Regal) Santiago de Chile (up to 2014)

Flughafen Zürich (Unique) Hangzhou International Airport

Fraport Hong Kong Airport

Kobenhavns Lufthavne Incheon

London Gatwick JATC

Malta International Airport Malaysia Airports Holdings

Munich airport Melbourne (APAC)

SAVE (Venezia) (up to 2016) Mumbai (up to 2014)

Schiphol Amsterdam Airport NanJing Lukou International Airport

Sheremetyevo Narita

TAV Havalimanlari Holding Shanghai International Airport (Hongqiao)

Toscana Aeroporti Shenzhen Airport Co.

Sichuan Province Airport Group

Sydney Airport

Xiamen International Airport Co.

26 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Annex: Companies included in the analysis

ANSPs

The ANSPs studied in the analysis represent approximately

USD 7 to 9 billion in revenue. To compute sector aggregates

for ROIC and economic prot, the sample analyzed is scaled

up using its proportion of estimated total sector revenue.

Companies included:

Lessors

The lessors studied in the analysis represent approximately

40% of estimated global lessor revenue. To compute sector

aggregates for ROE and economic prot (based on the

dierence between ROE and Cost of Equity), the sample

analyzed is scaled up using (a) its proportion of estimated total

sector revenue and (b) its proportion of estimated total sector

eet value.

Companies included:

OEMs

The aircraft and engine OEMs studied in the analysis represent

more than 90% of estimated global OEM revenue. To compute

sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample

is scaled up using its proportion of estimated total sector

revenue.

Companies included:

MROs

The MROs studied in the analysis represent between 30% and

40% of estimated global MRO revenue. To compute sector

aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample is scaled

up using its proportion of estimated total sector revenue.

Companies included:

Ground handlers

The ground handlers studied in the analysis represent

approximately 25% of estimated global handling revenue. To

compute sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot,

the sample is scaled up using its proportion of estimated total

sector revenue.

Companies included:

Aerothai

Air Services

Airways Corporation of New Zealand

ATNS

CAAS

DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung

ENAIRE

ENAV

GKOVD - State Federal Unitary Enterprise ATM corp.

NATS

NavCanada

AerCap Holdings

Air Lease Corporation

Aircastle

Alafco

Aviation Capital Group

Avolon (to 2014)

AWAS (to 2016)

BOC Aviation

Boeing Capital (up to 2012)

China Aircraft Leasing Company

Dubai Aerospace Enterprise

FlyLeasing

ILFC (up to 2013)

Intrepid Aviation (up to 2014)

Nordic Aviation Capital

Willis Lease

Airbus Commercial

Boeing Commercial

COMAC

Embraer

Pratt & Whitney

Safran

AAR Corp

AirAsia Taiwan

AMECO

BBA Aviation

GAMECO

HAECO

Lufthansa Technik

SIAEC

Bangkok Aviation Fuel Services

BBA Aviation

Celebi Hava Servisi

Derichebourg/Penauille (up to 2012)

DNATA

GlobeGround Berlin (up to 2012)

Heathrow Airport Fuel Company

John Menzies

Korea Airport Service Co

Saigon Ground Services

SATS (ground handling)

Saudi Ground Services Company

World Fuel Services – Aviation

27 Understanding the pandemic’s impact on the aviation value chain Annex: Companies included in the analysis

Caterers

The caterers studied in the analysis represent between 30%

and 40% of estimated global caterer revenue. To compute

sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample

is scaled up using its proportion of estimated total sector

revenue.

Companies included:

GDSs – Travel tech

The GDSs/travel tech players studied in the analysis represent

more than 90% of estimated global GDS revenue. To compute

sector aggregates for ROIC and economic prot, the sample

is scaled up using its proportion of estimated total sector

revenue.

Companies included:

Freight forwarders

The freight forwarders used in the analysis report a mixture

of contract logistics and freight forwarding revenues, which

in some cases has not been possible to split. Similar to other

sectors, ROIC and economic prot for the sector has been

estimated by scaling up estimates based on the sample, using

the share of global sector revenue.

Companies included:

Do & Co

Gate Group

Journey Group (up to 2015)

SATS (Catering)

Saudi Airlines Catering Company

Servair

Amadeus IT Group

Sabre Corporation

Travelport

Travelsky

Agility Public Warehousing Company

DSV Panalpina

Expeditors

Hellman Worldwide Logistics

Kintetsu World Express

Kuehne & Nagel International

Panalpina (up to 2018)

Uti Worldwide (up to 2014)